Abstract

Studies examining the effects of stimulus contingency on filial imprinting have produced inconsistent findings. In the current study, day-old bobwhite chicks (Colinus virginianus) received individual 5-min sessions in which they were provided contingent, noncontingent, or vicarious exposure to a variant of a bobwhite maternal assembly call. Chicks given contingent exposure to the call showed a significant preference for the familiar call 24 hr following exposure and significantly greater preferences than chicks given noncontingent exposure. Chicks given vicarious exposure to recordings of another chick interacting with the maternal call showed significant deviations from chance responding; however, the direction of chick preference (toward the familiar or unfamiliar) depended on the particular call used. These results indicate that both direct and indirect (vicarious) exposure to stimulus contingency can enhance the acquisition of auditory preferences in precocial avian hatchlings. Precocial avian hatchlings thus likely play a more active role in directing their own perceptual and behavioral development than has typically been thought.

Keywords: filial imprinting, contingency, interactive stimulation, vicarious learning, Northern bobwhite

Social interaction and contingency are known to have potent influences on learning across a wide range of organisms and contexts. Grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus), for example, have been shown to learn the proper use of referential labels only when provided interactive sessions with live tutors (e.g., Pepperberg, 1994, 1998). Human infants have also been found to produce more sophisticated vocalizations when their mothers respond to their babbling in a contingent manner (Goldstein, King, & West, 2003). In contrast to such findings, filial imprinting has traditionally been viewed as a special type of learning that occurs largely independent of contingent interaction or overt reinforcement (e.g., Lorenz, 1935, 1937).

A number of studies have directly examined the effects of stimulus contingency on the behavior of precocial hatchlings, the majority of which have focused on whether imprinting stimuli are capable of functioning as reinforcers. Such studies have demonstrated that precocial avian neonates will indeed work to be exposed to such stimuli (e.g., Bateson & Reese, 1968; Campbell & Pickleman, 1961; Eacker & Meyer, 1967; Gaioni, Hoffman, DePaulo, & Stratton, 1978; Hoffman, Schiff, Adams, & Searle, 1966; Meyer, 1968; Peterson, 1960). Relatively few studies, on the other hand, have examined the effects of contingency on the formation of filial preferences. Some of these studies have reported enhanced acquisition of filial preferences under conditions of stimulus contingency (e.g., Bateson & Reese, 1969; Evans, 1991; Johnson, Bolhuis, & Horn, 1985; ten Cate, 1989b), whereas others have found little or no difference in the level of filial preference between chicks provided with contingent versus noncontingent exposure to stimuli (Bolhuis & Johnson, 1988; ten Cate, 1986).

A key difference between those studies showing enhanced acquisition of filial preference with contingency versus those showing no difference between contingent and noncontingent presentation is the inclusion of a yoked, noncontingent control in the latter (Bolhuis & Johnson, 1988; ten Cate, 1986). This methodological improvement is, however, potentially the source of the null findings: In both studies yoked, noncontingent subjects were run simultaneous with and in relative close proximity to contingent subjects and may thus have experienced some form of social learning. The vicarious acquisition of filial preferences has been little studied compared with direct, individual acquisition, and the influence of intrabrood social factors on filial imprinting has generally been ignored (c.f. Lickliter, Dyer, & McBride, 1993; Lickliter & Gottlieb, 1985).

Beulig and Dalezman (1992) demonstrated that Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) chicks are capable of vicariously acquiring preferences in an imprinting situation. In their study, chicks provided with the opportunity to observe a conspecific following an imprinting stimulus subsequently showed greater preferences for the observed stimulus. In ten Cate’s (1986) study, Japanese quail chicks given yoked exposure had auditory contact with conspecifics that had operant control of the movement of an imprinting stimulus via their distress vocalizations. Yoked subjects were thus exposed both to the operant behavior and to a direct consequence of that behavior. In Bolhuis and Johnson’s (1988) study yoked chicks had no access to the operant behavior, stepping on a pedal in the floor, as chicks were in separate cabinets during training. It is possible, however, that yoked subjects were exposed to conspecific vocalizations concomitant with the presentation and removal of the imprinting stimulus.

The present study explored the effects of both contingent and vicarious exposure to auditory stimuli on the acquisition of auditory preferences in Northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) chicks. Previous studies have shown that bobwhite chicks require 240-480 min of noncontingent exposure (delivered 10 min/hr for 24-48 hr) to a particular variant of a bobwhite maternal assembly call to show a significant preference for that call over a novel maternal call 24 hr following exposure (Foushée & Lickliter, 2002; Lickliter & Hellewell, 1992). We were interested in whether brief contingent exposure to such stimuli would enhance the acquisition of auditory preferences relative to passive, noncontingent exposure. We were also interested in whether bobwhite hatchlings could form auditory preferences as the result of being exposed to another chick interacting with an auditory stimulus.

General Method

Several features of our methods were common across all of the experiments and are thus discussed first.

Subjects

Fertile, unincubated bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) eggs were received weekly from a commercial supplier (Strickland, Pooler, GA) and incubated in a Grumbach BSS 160 Incubator (Munich, Germany), maintained at 37.5 °C and 70%-75% relative humidity. Twenty-four hours prior to hatch, embryos were transferred to a Grumbach S84 Hatcher, maintained at 37.5 °C and 75%-80% relative humidity. Shortly after hatch, chicks were transferred to a sound-proof rearing room and placed in groups of 10-15 sameaged chicks to mimic natural brood conditions (Stokes, 1967). Groups of chicks were housed in large plastic tubs (25 cm wide × 15 cm high × 45 cm long) on shelves in a Nuaire Model NU-605-500 Animal Isolator (Plymouth, MN). Ambient air temperature was maintained at approximately 35 °C in the rearing room and 31 °C in the testing room, where all training and testing sessions took place. Chicks for each condition were drawn from two or more weekly batches to minimize the influence of inter-batch variability. Except for during training and testing sessions, chicks had ad libitum access to food and water.

Apparatus

All individual training and testing sessions were conducted in a large circular arena (diameter = 130 cm, height = 24 cm) within a sound-attenuated room. The surface of the arena was painted flat black, and the sides of the arena were covered by a layer of sound-attenuating foam, covered by opaque black cloth. Loudspeakers, connected to independent RCA SA-155 amplifiers (Fort Worth, TX) and Sony CDP-XE370 compact disk players (Tokyo, Japan), were hidden on opposite sides of the arena. Prior to all training and testing sessions, sound pressure levels at the start location for chicks placed in the arena (a point equidistant from both speakers on the periphery of the arena) were calibrated to a maximum of 65 dB for both speakers using a Brüel & Kjaer Model 2232 sound-level meter (B & K Instruments, Marlborough, MA). At the start of all sessions a single chick was placed in a plastic start box at the start location and left for a period of 30-60 s prior to the onset of stimulation and/or data collection. All stimulus deliveries and behavioral observations were recorded with a Visual Basic/Excel macro.

Stimuli

Maternal calls

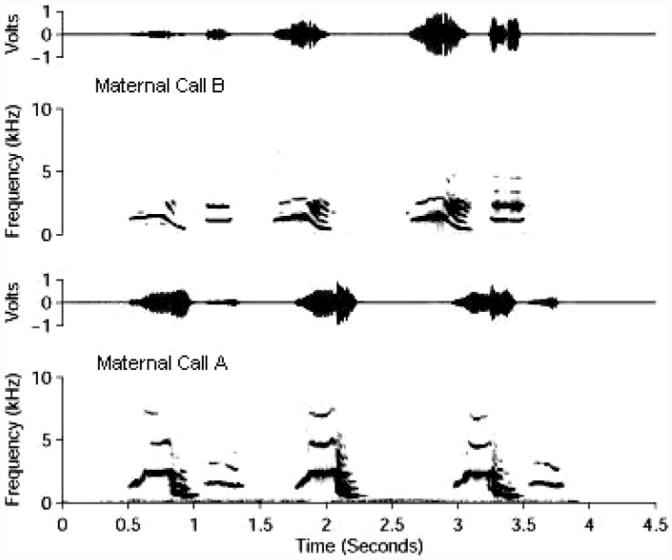

The main stimuli used during training and testing sessions were two variants of a bobwhite maternal assembly call, Calls A and B (Heaton, Miller, & Goodwin, 1978), cleaned of background noise by the Borror Laboratory of Bioacoustics (Columbus, OH). Both are similar in phrasing, repetition rate, and frequency modulation and vary primarily in minor peaks of dominant frequency and pitch (see Figure 1). Call A was recorded under conditions of a bobwhite hen leading her young away from the nest, and Call B was recorded from a bobwhite hen in a colony where no chicks were present. A number of studies have demonstrated that bobwhite chicks have no naive preference for either of these calls and are capable of acquiring significant preferences for either call (e.g., Honeycutt & Lickliter, 2001, 2002; Lickliter, Bahrick, & Honeycutt, 2002; Lickliter & Hellewell, 1992).

Figure 1.

Waveforms and spectrograms for maternal Calls A and B.

Distress vocalizations

Recordings of bobwhite chick distress/contact vocalizations were used during training in some conditions. Such calls can easily be distinguished from other chick vocalizations and generally consist of strings of rapid “peeps” (Stoumbos, 1990). Experimenters were trained to both identify and monitor these vocalizations during all training sessions.

Training Sessions

Training sessions took place on Day 1 post-hatch and consisted of 5-min exposures to a maternal call (A or B) and/or distress vocalizations. Presentation of stimuli was alternated and balanced to prevent the engendering of any side biases in chicks. A count was maintained of all distress vocalizations occurring during training, except in the contingent condition of Experiment 1, where the occasional tendency of some chicks to begin vocalizing prior to the end of stimulation prevented a precise tally of vocalizations. These sessions were not recorded, and so the count in this condition must be considered an estimate. In all other conditions, any certain occurrence of a distress vocalization was tallied separately from either any uncertain occurrence of a distress vocalization or any other vocalizations. Tallies for the later category were tallies not of the absolute frequency of such vocalizations, but of vocalization bouts, defined arbitrarily as strings of isolated peeps and/or other sounds separated by less than 1 s.

Testing Sessions

Testing sessions took place on Day 2 post-hatch, approximately 24 hr following training. Testing sessions were identical within and across experiments, consisting of 5-min choice tests between Calls A and B. The calls were played at equal repetition rates from opposite sides of the arena and were counterbalanced across the two sides within each condition. A semicircular approach area, corresponding to 5% of the surface area of the arena, was demarcated around each speaker on the monitor used for observing sessions. Upon entry of a chick into one of these areas, the experimenter clicked one of two buttons in a Visual Basic/Excel program. The button was held down until the chick exited the area. The primary data of interest were cumulative scores for duration and scores for latency of approach to each area.

Data Analyses

Raw duration scores were converted into categorical preferences so that chi-square tests could be performed on their distributions. Following the procedure used in a number of previous studies (e.g., Heaton et al., 1978; Lickliter & Hellewell, 1992), chicks failing to spend at least 10 s in at least one approach area were scored as nonresponders and excluded from further analyses. Out of the remaining subjects, chicks failing to spend at least twice as long in one approach area as in the other were scored as displaying no preference. A chick was scored as displaying a preference for a call if the chick spent at least 10 s in the approach area for that call and at least twice as long in that area as in the other. A latency score of 300 s and a duration score of zero were assigned for any area not entered by a chick during a testing session. Chi-square tests were supplemented with Wilcoxon matched-pairs signedranks tests on raw latency and duration scores. Duration and latency scores were also converted into proportion of total duration (PTD) and proportion of trial to approach (PTTA) each call, respectively. Between-groups comparisons were performed on differences between these proportions (familiar minus unfamiliar) with Mann-Whitney U tests. For chicks unexposed to a maternal call, these scores were calculated with respect to Call A. Effect sizes reported are Glass rank biserial correlational coefficients (rg) for Mann-Whitney U tests and matched-pairs rank biserial correlational coefficients (rC) for Wilcoxon tests. All confidence intervals (CIs) reported are 95%, and all statistical tests used were evaluated at p < .05 (two-tailed).

Experiment 1: The Effects of Contingent, Noncontingent, and Vicarious Exposure on Auditory Preferences in Bobwhite Chicks

Experiment 1 examined the effectiveness of brief (5-min) periods of contingent, noncontingent, and vicarious exposure to a bobwhite maternal assembly call on the development of auditory preferences in day-old bobwhite chicks. We predicted that chicks given exposure to a call contingent upon their own distress vocalizations would show significant preferences for that call when tested 24 hr following exposure and that chicks given noncontingent exposure would not. We also predicted that chicks given vicarious exposure to another chick interacting with a call would acquire a significant preference for that call.

Method

Subjects

189 Northern bobwhite chicks served as subjects. Chicks in the contingent (CON) condition (n = 69) were run first, and chicks in the noncontingent (NOC; n = 58) and vicarious (VIC; n = 62) conditions were later yoked to these.

Procedure

All chicks in the CON, NOC, and VIC conditions were given individual 5-min exposures to a maternal call (A or B) on Day 1 post-hatch. Chicks in the CON condition were played a single burst of the call when they distress vocalized during training. Experimenters waited until the chick ceased vocalizing to play the call. If a chick began vocalizing prior to the end of playback, the experimenter waited until the end of the next vocalization to play the call. Experimenters played the call a maximum of four times noncontingently, pausing 10-15 s between each, to coax nonvocal chicks into responding. This procedure elicited vocalizations in the majority of initially nonvocal chicks.

Any chick that failed to respond (n = 4 for Call A; n = 5 for Call B) was removed from the study. Chicks in the NOC condition were yoked to 1 of 4 chicks from the CON condition. More specifically, half of the subjects (n = 28) were yoked to a chick that was very close to the mean number of presentations for either Call A (n = 15, M = 29) or Call B (n = 13, M = 36). The other half (n = 30) were yoked to a chick that was nearly two standard deviations above the mean for either Call A (n = 15, M = 37) or Call B (n = 15, M = 45). The second of these levels was chosen to maximize the chances of obtaining positive results in this condition. Recordings sequenced to exactly match the pattern and timing of presentations from CON sessions were prepared for each subgroup. Chicks in the VIC condition (n = 58) were given 5-min exposures to recordings identical to those used in the NOC condition, except with distress vocalizations from unfamiliar chicks inserted prior to each playback of the maternal call. These vocalizations were obtained from a sample of such vocalizations extracted from VHS recordings of pilot training sessions, low-pass filtered with SyrinxPC (Burt, 2005). The vocalizations were sequenced to switch from side to side semirandomly throughout the session. Maximum sound pressure levels were calibrated to the maternal call bursts, as in all other conditions. In the VIC, as in the NOC, condition there were four subgroups: the mean for Call A (n = 15) or B (n = 15) and two standard deviations above the mean for Call A (n = 17) or B (n = 15). Subjects in the CON, NOC, and VIC conditions were given individual simultaneous choice tests, approximately 24 hr following training, as previously described.

Results and Discussion

Training

Little difference was found between the number of distress vocalizations produced during training by chicks given CON versus NOC exposure (Table 1). This replicates the results of ten Cate (1986), who found no increase in vocalization rate in Japanese quail chicks with contingent versus noncontingent exposure to stimulus movement. This finding is at apparent odds with standard operant paradigms, in that an increase in rate of responding is the general index of reinforcement and learning. A likely reason for this discrepancy is that the behavior used in the current study (and ten Cate, 1986) was not a rapid, temporally discrete one (e.g., a peck or a lever press) but a temporally extended behavior. Bobwhite chick distress vocalizations typically range from 1 to 5 s each, and these occupied a large portion of the training sessions. Stimulus presentations were not made until chicks ceased vocalizing, and the presentation of the stimulus, which lasted about 3-3.5 s, generally inhibited vocalizing. Within such a temporally bounded system, in which both operant and response are mutually inhibitory, an increase in rate of responding faces an obvious limit. Far fewer distress vocalizations were recorded for subjects given vicarious (or any regime containing chick vocalizations) compared with CON and NOC exposure. This difference is likely the result of the suppression of vocalizations by distress call playback but may have also been influenced by the increased difficulty of the task for experimenters. Given this lack of clarity, and because we lacked recordings to double-check vocalizations within CON sessions, these data were not analyzed statistically but are nonetheless presented for reference purposes.

Table 1.

Mean Number of Vocalizations During Training in Experiments 1-3

| Type of Vocalization |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distress |

Other |

Total |

|||||

| Condition | n trained | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Experiment 1 | |||||||

| Contingent A | 32 | 29.4 | 5.2 | n/a | 29.4 | 5.2 | |

| Noncontingent A | 30 | 30.3 | 12.3 | 12.7 | 13.2 | 43.0 | 18.1 |

| Vicarious A | 32 | 18.8 | 10.5 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 25.8 | 14.4 |

| Contingent B | 30 | 35.2 | 5.2 | n/a | 35.2 | 5.2 | |

| Noncontingent B | 30 | 29.1 | 13.5 | 9.4 | 10.0 | 38.5 | 16.7 |

| Vicarious B | 30 | 21.3 | 11.7 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 28.9 | 14.4 |

| Experiment 2 | |||||||

| Distress vocalization | 49 | 23.6 | 21.7 | 2.3 | 4.3 | 25.9 | 21.8 |

| Experiment 3 | |||||||

| Noncontiguous A | 30 | 19.9 | 9.4 | 6.9 | 7.9 | 26.8 | 10.0 |

| Noncontiguous B | 36 | 23.3 | 10.8 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 30.3 | 14.4 |

Testing

Chick preferences are displayed in Table 2. Chicks responded differentially depending upon which call they received during training, particularly when provided with VIC exposure to a call, χ2(2, N = 53) = 25.59, w = .71, p < .001. As a result, data were not collapsed across the two calls, and the results for all A and B sub-conditions were analyzed separately. There were no significant differences between chicks given either the mean or two-standard deviations levels of NOC exposure to either Call A or B or VIC exposure to Call A. A trend toward significance was observed for chicks given VIC exposure to Call B, χ2(2, N = 27) = 5.32, w = .44, p = .07; however, chicks given both levels of exposure showed latency and duration scores in favor of the same call (see below). As a result, data were collapsed across levels of exposure within the NOC and VIC subconditions.

Table 2.

Preferences for the Familiar and Unfamiliar Calls in Experiments 1

| Preference |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | n responding | Familiar | Unfamiliar | NP |

| Contingent A | 26 | 22** | 0 | 4 |

| Contingent B | 27 | 14 | 4 | 9 |

| Noncontingent A | 29 | 15* | 3 | 11 |

| M | 15 | 7 | 1 | 7 |

| Two SD | 14 | 8 | 2 | 4 |

| Noncontingent B | 26 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| M | 12 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Two SD | 14 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Vicarious A | 26 | 21** | 1 | 4 |

| M | 12 | 9 | 1 | 2 |

| Two SD | 14 | 12 | 0 | 2 |

| Vicarious B | 27 | 3 | 11* | 13 |

| M | 14 | 0 | 8 | 6 |

| Two SD | 13 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

Note. NP = no preference.

p < .05.

p < .001.

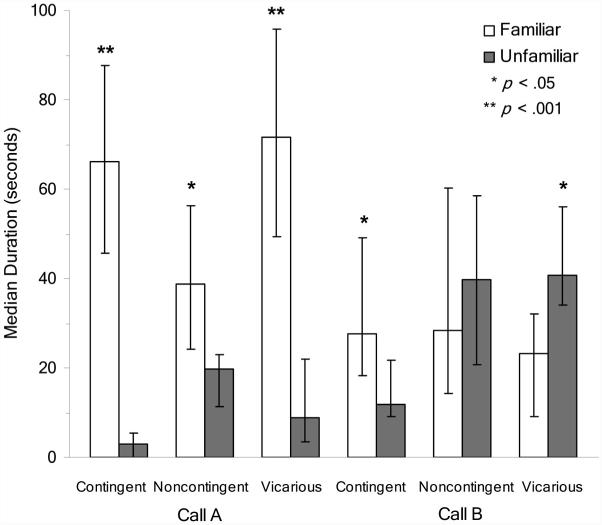

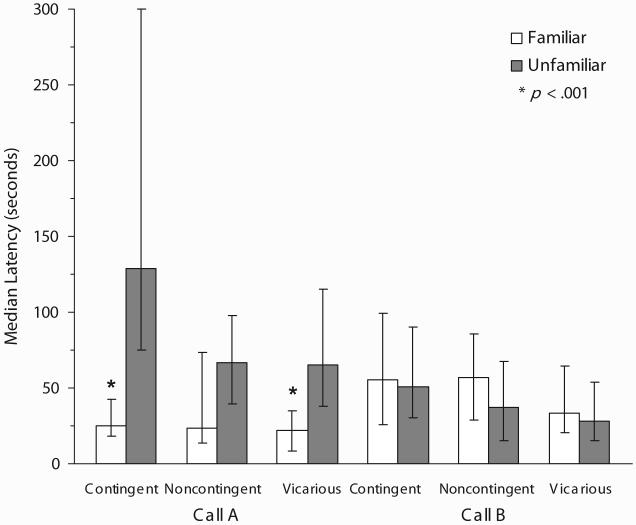

Median duration and latency scores are displayed in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. As can be seen, all chicks trained with Call A showed significant preferences for that call. Chicks given CON exposure to Call A had significantly longer duration scores (z = -4.31, effect size = .97, p < .001) and significantly shorter latencies (z = -3.47, effect size = .78, p < .001) for Call A. Chicks given VIC exposure to Call A likewise spent a significantly longer amount of time in proximity to (z = -4.15, effect size = .93, p < .001) and had significantly shorter latencies of approach to (z = -3.40, effect size = .76, p < .001) Call A. Chicks given NOC exposure, in contrast, showed significantly larger duration (z = -2.41, effect size = .51, p = .016) but not shorter latency (z = -1.31, effect size = .28, p = .191) scores for Call A.

Figure 2.

Median duration scores (± 95% confidence interval) for the familiar and unfamiliar calls. Significance indicated is for Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks tests.

Figure 3.

Median latency scores (± 95% confidence interval) for the familiar and unfamiliar calls. Significance indicated is for Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks tests.

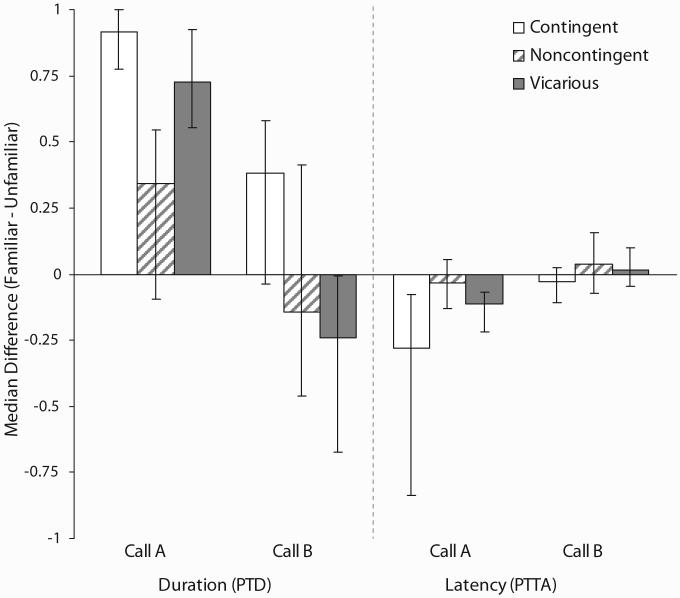

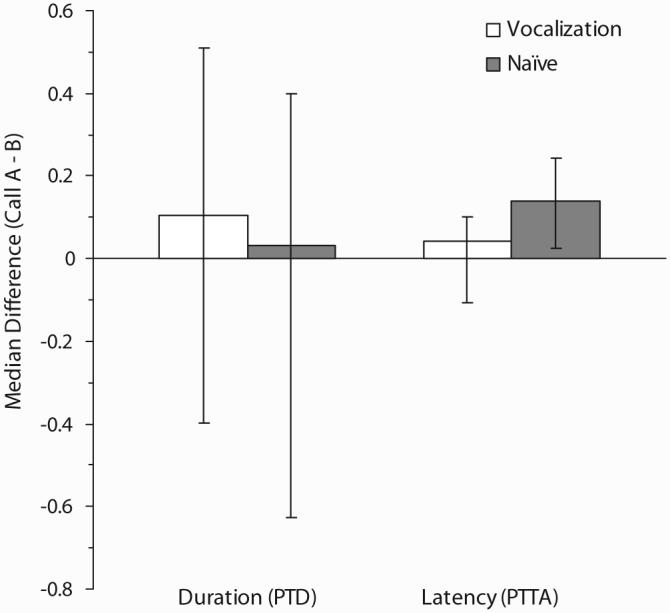

Median PTD and PTTA difference scores are displayed in Figure 4. Between-groups comparisons revealed significantly larger PTD (z = -3.46, effect size = -.54, p < .001) and PTTA (z = -2.51, effect size = .40, p = .012) difference scores for chicks given CON compared to NOC exposure to Call A. Chicks given VIC exposure to Call A similarly showed significantly larger PTD (z = -2.61, effect size = .41, p = .009) but not PTTA (z = -1.42, effect size = -.22, p = .154) difference scores than chicks given NOC exposure. The comparison between chicks given CON and VIC exposure to Call A approached but fell short of significance for both PTD (z = -1.75, effect size = -.28, p = .082) and PTTA (z = -1.78, effect size = .29, p = .077) difference scores.

Figure 4.

Median (± 95% CI) difference scores for proportion of total duration (PTDfamiliar - PTDunfamiliar) and proportion of trial to elapse prior to approach (PTTAfamiliar - PTTAunfamiliar). Proportion of total duration (PTD) difference scores higher than zero signify a longer time spent in proximity to the familiar call, and proportion of trial elapsed prior to approach (PTTA) difference scores lower than zero signify shorter latencies of approach to the familiar call.

Chicks trained with Call B showed a weaker pattern of preferences overall than chicks trained with Call A (see Table 2). The chi-square for chicks given CON exposure to Call B, for example, approached significance, χ2(2, N = 27) = 5.56, w = .45, p = .062, whereas the test for chicks given VIC exposure was significant, χ2(2, N = 27) = 6.22, w = .48, p = .045. Chicks given VIC exposure, however, showed evidence of a preference for the unfamiliar Call A. These chicks showed significantly longer duration (z = -2.19, effect size = .48, p = .029) but not shorter latency (z = -1.00, effect size = .22, p = .319) scores for Call A. Chicks given CON exposure, in contrast, showed significantly larger duration (z = -2.42, effect size = .53, p = .016) but not shorter latency scores (z = -0.87, effect size = .07, p = .387) for the familiar Call B. Chicks given NOC exposure did not show longer duration (z = -0.55, effect size = .12, p = .585) or shorter latency scores (z = -0.27, effect size = .06, p = .790) for Call B.

Between-groups comparisons revealed that chicks given CON exposure to Call B showed significantly larger PTD (z = -2.08, effect size = -.33, p = .038) but not PTTA (z = -0.75, effect size = .12, p = .455) difference scores than chicks given NOC exposure (see Figure 4). Chicks given VIC exposure to Call B, in contrast, showed no significant difference in PTD (z = 1.27, effect size = .21, p = .203) or PTTA (z = -0.30, effect size = .05, p = .762) difference scores from chicks given NOC exposure to Call B (see Figure 4).

These results indicate a significant difference between contingent and noncontingent exposure on the development of auditory preferences in bobwhite chicks. Chicks provided with brief NOC exposure to a maternal call either failed to show a significant preference for that call (Call B) or else showed a significantly lower preference than chicks given CON exposure (Calls A and B). It might be argued that this interpretation is not valid given that the design used entails pseudoreplication. Pseudoreplication is, however, not inherent in any particular design but results from a mismatch between design and analysis/interpretation of data (Hurlbert, 1984). How replicates are assigned in a study must depend both on the purpose of the experiment and on what is known about variability in the system under study. The semiyoked design used was used both to prevent cross-contamination between CON and yoked NOC subjects and because of the time and resources required to produce a completely yoked design utilizing the methodology used (manually sequencing and burning CDs). A fully yoked design would have been the ideal; however, the crucial factor within the NOC condition was that the stimulation was noncontingent. An individual chick within the NOC condition of the current experiment would have received equally NOC stimulation whether the design was fully yoked or not. The critical factors known to be important in the development of auditory preferences in bobwhite hatchlings are the amount of exposure to a stimulus (e.g., Lickliter & Hellewell, 1992), variability in interstimulus interval (Harshaw, Schneider, & Lickliter, 2005), and the presence or absence of intersensory redundancy (Lickliter et al., 2002). All of these factors were held constant within the NOC subconditions, and by clustering replicates at the mean and two standard deviations above the mean, we thus deliberately “loaded” the experiment against our alternative hypothesis.

Chicks given VIC exposure to a maternal call showed significant preferences; however, the direction of their preference (to the familiar or unfamiliar) depended on the particular call used. Consistent with our predictions, chicks provided with VIC exposure to Call A showed significant preferences for that call. Moreover, their PTD and PTTA difference scores were not significantly different from those of chicks given CON exposure to the same call. This provides some evidence that bobwhite chicks can acquire stimulus preferences as a result of being exposed to another chick vocally interacting with an auditory stimulus. It may be argued that the collapsing of the mean and two-standard deviations levels of exposure within the VIC condition may have been responsible for this result. A comparison of PTD (z = -1.31, effect size = .31, p = .190) and PTTA (z = -1.47, effect size = -.35, p = .143) difference scores, however, revealed no significant difference between the two levels. Chicks given VIC exposure to Call B, in contrast, showed significant preferences for the unfamiliar Call A. This finding makes the interpretation of the data from our VIC condition difficult. It was thus necessary to rule out this effect being the result of either a naive bias toward Call A or else a consequence of mere exposure to conspecific distress vocalizations during training.

Experiment 2: The Effects of Exposure to Conspecific Distress Vocalization on the Development Auditory Preferences in Bobwhite Chicks

This experiment was designed to rule out the possibilities that either exposure to chick distress vocalizations or a naive bias caused chicks provided with VIC exposure to a maternal call in Experiment 1 to prefer Call A during testing. These were seen as unlikely possibilities given that socially reared chicks are frequently exposed to such vocalizations and because previous studies have found bobwhite chicks to have no naive preferences for either of these calls (e.g., Lickliter & Hellewell, 1992). It was nonetheless possible that the exposure to distress vocalizations might have had some influence on chick preferences. We thus tested the effects of exposure to only conspecific distress vocalizations on chick preferences for the two unfamiliar maternal calls. We also tested a group of chicks naively on Day 2 post-hatch to confirm that bobwhite hatchlings have no naive preferences for either call.

Method

Eighty-two maternally naive bobwhite chicks served as subjects. Chicks in the vocalization (VOC) condition (n = 49) were exposed only to chick distress vocalizations during their 5-min training sessions on Day 1 post-hatch. All remaining chicks (n = 33) served as naive controls. The recordings used in VOC sessions were identical to those from the VIC condition of Experiment 1, except with the maternal calls removed. Given the closeness of the mean level of exposure for Call B and the two-standard deviations level of exposure for Call A (36 and 37 exposures, respectively), only the latter was used. Chicks in the VOC condition were thus exposed to 29 (n = 15), 37 (n = 19), or 45 (n = 15) conspecific distress vocalizations. As in Experiment 1, all subjects were given individual 5-min choice tests between both maternal calls on Day 2 post-hatch.

Results and Discussion

Chick preferences can be found in Table 3. Chicks displayed no naiïve preference for either variant of the maternal assembly call when tested on Day 2 post-hatch, χ2(2, N = 31) = .452, w = .12, p = .798. There was no significant difference in the distribution of preferences between the three levels of VOC exposure, χ2(4, N = 39) = 4.07, w = .32, p = .396. As a result, data for the three levels were collapsed for further analysis. Chicks given VOC exposure showed no significant preference for either maternal call, χ2(2, N = 39) = 3.85, w = .31, p = .146, and did not show larger duration (z = -0.95, effect size = .17, p = .343) or shorter latency (z = -0.06, effect size = .01, p = .955) scores for either call. As can be seen in Figure 5, this pattern of results is consistent with the results obtained with naive control chicks. Mann-Whitney U tests found no significant difference in PTD difference scores (z = -1.10, effect size = -.15, p = .274) between VOC and naive chicks and a trend toward significance in the comparison of PTTA difference scores (z = -1.95, effect size = .27, p = .051). This later result was the product of shorter latencies of approach to Call B in naive subjects.

Table 3.

Chick Preferences for Calls A and B in Experiment 2

| Preference |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | n responding | Call A | Call B | NP |

| Naive controls | 31 | 10 | 12 | 9 |

| Vocalization | 39 | 18 | 13 | 8 |

| 29 | 12 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

| 37 | 13 | 7 | 2 | 4 |

| 45 | 14 | 6 | 5 | 3 |

Note. NP = no preference.

Figure 5.

Median difference scores (± 95% confidence interval) for proportion of total duration (PTDCall A - PTDCall B) and proportion of trial to elapse prior to approach (PTTACall A - PTTACall B) for Experiment 2. PTD = proportion of total duration; PTTA = proportion of trial elapsed prior to approach.

These results confirm that bobwhite chicks have no naive preferences for either of the two maternal calls used in the current study and demonstrate that mere exposure to chick vocalizations during training does not bias chicks toward preferring maternal Call A. It is possible nonetheless that exposure to both chick-distress vocalizations and maternal calls during training, as was done in the VIC condition of Experiment 1, may have selectively enhanced chicks’ preferences for maternal Call A irrespective of the contiguity between the two sets of stimuli. This possibility was addressed in Experiment 3.

Experiment 3: The Role of Temporal Contiguity in the Vicarious Acquisition of Auditory Preferences in Bobwhite Chicks

This experiment was designed to control for the role of temporal contiguity in the vicarious acquisition of auditory preferences in chicks exposed to both a maternal call and another chick interacting with that call. Temporal contiguity is widely known to play an important role in the production of learning under conditions of stimulus contingency (e.g., Catania, 1992; Guthrie, 1935; Skinner, 1948; Williams, 2001). We thus hypothesized that chicks given noncontiguous (NCT) exposure to chick distress vocalizations and a maternal call would either fail to show an auditory preference for Call A or show significantly weaker preferences than the VIC chicks in Experiment 1.

Method

Chicks in the NCT condition (n = 61) were given individual 5-min exposures to recordings identical to those used in the NOC condition, except that the same chick distress vocalizations used in the VIC condition were inserted semirandomly such that none of the vocalizations immediately preceded playback of the maternal call. A random number generator was used to produce initial values for the placement of vocalizations, and these were manually adjusted to remove any chance contiguities. The distress vocalizations were placed such that an average of 3.2 s (± 1.7) of silence was between the offset distress vocalizations and the onset of the maternal call. As in the NOC and VIC conditions, there were four subgroups and levels of exposure: the mean for Call A (29; n = 15) or Call B (36; n = 15) and two standard deviations above the mean for Call A (37; n = 19) or Call B (45; n = 17). All subjects were tested, as previously described, approximately 24 hr following training.

Results and Discussion

Chick preferences can be found in Table 4. No significant differences in preferences between the mean and two-standard deviations levels of exposure were found for either Call A, χ2(2, N = 29) = 0.52, w = .13, p = .770, or Call B, χ2(2, N = 31) = 0.30, w = .10, p = .859. As a result, data were collapsed across these levels. Evidence of a significant preference for the familiar call was found for chicks given NCT exposure to Call A, χ2(2, N = 29) = 12.07, w = .65, p = .002, but not for chicks exposed to Call B, χ2(2, N = 31) = 0.84, w = .16, p = .657. As a result, data were not collapsed across Calls A and B. Chicks given NCT exposure to Call A showed significantly larger duration (z = -4.00, effect size = .85, p < .001) but not shorter latency (z = -1.22, effect size = .26, p = .226) scores for Call A than for Call B. Chicks given NCT exposure to Call B, on the other hand, did not show significantly larger duration (z = -0.21, effect size = .04, p = .836) or shorter latency (z = -0.01, effect size < .01, p = .992) scores for Call A than for Call B.

Table 4.

Chick Preferences for the Familiar and Unfamiliar Calls in Experiment 3

| Preference |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | n responding | Familiar | Unfamiliar | NP |

| Noncontiguous A | 29 | 18* | 3 | 8 |

| M | 14 | 8 | 2 | 4 |

| Two SD | 15 | 10 | 1 | 4 |

| Noncontiguous B | 31 | 11 | 8 | 12 |

| M | 14 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Two SD | 17 | 6 | 5 | 6 |

Note. NP = no preference.

p < .005.

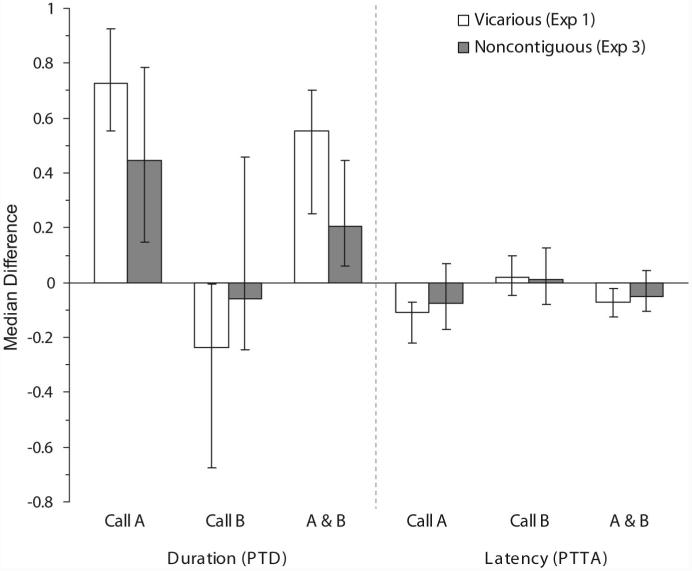

Between-groups comparisons revealed that chicks given NCT exposure to Call A showed a trend toward significantly smaller PTD (z = -1.44, effect size = -.23, p = .075) and PTTA (z = -1.32, effect size = .21, p = .094) difference scores than the chicks given VIC exposure to Call A in Experiment 1 (see Figure 6). Chicks given NCT exposure to Call B, on the other hand, showed significantly smaller PTD (z = -1.81, effect size = .28, p = .035) but not PTTA (z = -.88, effect size = -.09, p = .193) difference scores than chicks given VIC exposure to Call B.

Figure 6.

Median (± 95% confidence interval) proportion of total duration (PTD) and proportion of trial elapsed prior to approach (PTTA) difference scores for Experiment 3. Combined (Call A and Call B) scores are calculated with respect to Call A (Call A - Call B), and all other scores are calculated with respect to the familiar (familiar - unfamiliar).

These results did not conclusively confirm our hypotheses. By disrupting the temporal contiguity between chick distress vocalizations and maternal calls within the VIC condition of Experiment 1, we found significantly lower preferences for Call A in chicks exposed to Call B, but not in chicks exposed to Call A. Although chicks provided with exposure to Call A showed a similar trend, the comparison between VIC and NCT chicks was not significant. Chicks given VIC exposure to Call A (in Experiment 1) showed both significantly higher duration and shorter latency scores for Call A than for Call B, whereas chicks given NCT exposure to Call A failed to show significantly shorter latency scores for Call A than for Call B. This difference is suggestive of somewhat lower preferences in chicks given NCT versus VIC exposure to Call A. It is possible that a more carefully designed noncontiguity condition would block or further diminish the heightened preferences for Call A observed in chicks exposed both to Call A and chick distress vocalizations. In the current experiment only forward contiguity (the window of time prior to the second stimulus) was controlled. It is not known, however, whether forward and backward contiguity are functionally equivalent under conditions such as those used in this study. Bateson (2000), for example, has suggested that under circumstances of noncausal learning the exact sequencing of stimuli may be irrelevant for learning. In addition, it is unknown what the tolerance or threshold for the perception of noncontiguity is for bobwhite hatchlings. It is thus possible that precocial chicks have a high tolerance for noncontiguity, which could complicate attempts to present a fixed number of distress vocalizations and maternal calls noncontiguously within a fixed period of time. Further explorations of these issues would likely yield clarification as to whether the vicarious acquisition of preferences in precocial chicks is driven by attentional or associative processes.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that brief contingent exposure to a maternal call significantly enhanced the formation of preferences for that call in bobwhite chicks compared with noncontingent exposure. Previous studies have shown that bobwhite chicks require 240-480 min of noncontingent exposure to an individual variant of a bobwhite maternal assembly call (or 3,500-7,000 repetitions of the call) to show a significant preference for that call over a novel maternal call 24 hr following exposure (Foushée & Lickliter, 2002; Lickliter & Hellewell, 1992). Chicks in the current study, in contrast, showed significant preferences for the familiar call with less than 5 min of exposure (or 29-45 repetitions on average) when that exposure was made contingent upon their own vocalizations. These results are particularly striking in that Lickliter and Hellewell (1992) found a preference for the familiar maternal call only when chicks were socially isolated following hatching. Foushée and Lickliter (2002), additionally, found a preference for the familiar call (with 240 min of exposure) only in chicks that were dark-reared during and following exposure. All chicks in the current study, in contrast, were both group- and light-reared for the duration of the study.

In contrast to the results of the present study, ten Cate (1986) found no difference in strength of filial preference between Japanese quail chicks given exposure to a contingently versus a noncontingently moving imprinting stimulus. Bolhuis and Johnson (1988) likewise found no difference in level of preference for an-imprinting stimulus in domestic chicks given contingent versus yoked, noncontingent exposure to the stimulus. The findings of the present study, combined with those of Beulig and Dalezman (1992), suggest that the results of these previous studies may have been confounded by the influence of vicarious learning in yoked, noncontingent subjects. In the current study, chicks provided with exposure to another chick interacting vocally with a maternal call showed significant shifts in preferential responding compared with naive chicks. Unlike chicks given contingent exposure, however, chicks responded differently depending upon which call they were exposed to. More specifically, chicks given vicarious exposure to Call A showed a significant preference for the familiar call, whereas chicks given vicarious exposure to Call B showed a preference for the unfamiliar call when tested 24 hr following exposure. In Experiment 2 we ruled out the possibility that this was due merely to exposure to the vocalizations of other chicks during training. Chicks exposed to recordings identical to those used in the vicarious condition, with the maternal calls replaced with silence, showed no preference for either maternal call when tested 24 hr following exposure. Experiment 3 demonstrated that the temporal contiguity between the chick distress vocalizations and maternal calls was likely an important factor in producing the preferences observed in chicks given vicarious exposure in Experiment 1. It is possible that the dynamics for the acquisition of preferences for visual, auditory, and multimodal stimuli differ to some extent, which could provide an alternative explanation for why our findings differ from those of ten Cate (1986) and Bolhuis and Johnson (1988). The findings of the present study thus need to be replicated with other types of stimulation.

Bolhuis and Johnson (1988) provided data to support the notion that the critical variable for engendering filial preferences in precocial chicks is not stimulus contingency but rather the schedule of stimulus presentation used. In particular, Bolhuis and Johnson reported variable interval/variable duration schedules to have a significantly greater impact on the acquisition of preferences than fixed interval/fixed duration schedules. It seems likely, however, that the effects of contingency interact with the effects of stimulus presentation schedules. It is well known that variable interval and variable ratio schedules generally produce higher and more steady rates of responding than fixed interval and fixed ratio schedules (e.g., Catania, 1992). It is possible that a noncontingent variable interval/variable duration schedule might be responded to as if it were a variable ratio reinforcement schedule, inducing steady rates of “superstitious” responding in precocial chicks. Skinner (1948) argued that chance contiguities between specific behaviors and environmental events could cause idiosyncratic patterns of superstitious behavior in pigeons. Several authors have failed to replicate these findings (e.g., Staddon & Simmelhag, 1971; Timberlake & Lucas, 1985), reporting instead that what occur most frequently under such conditions are context-appropriate species-typical behaviors. Whether or not such behavior is termed superstitious, the chance contiguity between particular behaviors and environmental events likely occurs regularly under many conditions (c.f. Neuringer, 1970). It seems likely that such responding can occur in precocial neonates, and this could provide an alternative account for the higher levels of preference obtained by Bolhuis and Johnson (1988) with noncontingent variable interval/variable duration versus fixed interval/fixed duration schedules.

This discussion, although speculative, highlights what may be a general limitation of any study investigating the differential effects of contingent and noncontingent stimulation on the development of stimulus preference: the potential inability to deliver a completely noncontingent stimulus (except possibly during sleep) to what is invariably an active organism. In the present study, for example, both chicks given noncontingent and vicarious exposure, despite our attempts at denying them the ability to interact directly with the maternal call, may have experienced chance pairings of their distress vocalizations and/or other behaviors with instances or specific features of maternal call playback. This would have been particularly likely in the vicarious condition, as many chicks in this condition frequently vocalized over the conspecific distress vocalizations played to them, particularly the terminal portion of these vocalizations. In many instances (both in the noncontingent and vicarious conditions), whether stimulus delivery was in fact contingent or noncontingent on the behavior of the chick being trained would have been indistinguishable from the perspective of a naive observer. It is thus unclear whether the enhanced preferential responding obtained in chicks given vicarious exposure to the maternal call was the product of stimulus enhancement, social facilitation, superstitious responding, or some combination thereof. To tease apart these various processes would require exposing chicks noncontingently to auditory stimulation while denying them the opportunity to vocalize (e.g. Gottlieb, 1971). Such a procedure could not guarantee the absence of other behavioral contiguities with noncontingent stimuli during training. The delivery of a purely noncontingent stimulus, particularly in a vicarious situation, may thus be a near impossibility. The delivery of such a stimulus to a sufficiently immobilized and devocalized organism would, moreover, likely have little applicability to the behavior of intact animals.

The exact feature(s) of Call A that rendered it more efficacious as a training stimulus across all conditions of the present study are unknown. The recording context is one difference between the two calls (Heaton et al., 1978), but it is not known what specific acoustic features make Call A more efficacious as a training stimulus, and it is additionally unknown why such features fail to be salient to naive hatchlings. One possible feature of Call A that may make it more attractive than Call B following exposure is that the higher dominant frequency of Call A (2.3-2.4 kHz) is closer to the normal range of distress/contact vocalizations of bobwhite chicks (2.4-3.2 kHz) than the dominant frequency of Call B (1.2-1.5 kHz). Baker and Bailey (1987) reported that the bobwhite chick distress/contact call undergoes changes throughout the 1st year of life, gradually developing into the standard bobwhite contact call, of which the maternal calls used in the present study are variants. During this time the developing bobwhite gradually gains the ability to vocalize the lower frequency portions of the call, presumably as a function of the maturation of the vocal apparatus. With the chicks’ limited experience with lower auditory frequencies, combined with the inability to produce such frequencies (and thus to self- and other-stimulate at those frequencies), it is plausible that the differential results obtained with Calls A and B in our study are directly tied to the perceptual limitations (or specializations) of the bobwhite chick. Other studies of perceptual development in bobwhite hatchlings using the same stimuli used in the present study have not previously encountered the issue of the differential effectiveness of Call A versus B (e.g., Lickliter & Hellewell, 1992). The likely reason for this is that such studies have predominantly been concerned with learning ability under various contextual (e.g., dark versus light rearing) and stimulatory conditions (e.g., unimodal versus bimodal exposure) and thus used an unbalanced design (see Bolhuis & Van Kampen, 1992) consisting exclusively of exposure to Call B.

The results of the present study suggest that the passive exposure paradigms that have traditionally been used to study the formation of perinatal perceptual preferences have likely given researchers a very limited or partial view of the perceptual and behavioral capabilities of precocial embryos and hatchlings. The classic phenomenon of filial imprinting—taken as the passive process by which precocial neonates form social attachment to the first conspicuous object encountered upon hatching, independent of interaction and/or reinforcement—likely has only limited relation to what typically occurs in nature for many species.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that contingency, whether experienced directly or vicariously, can significantly enhance the development of auditory preferences in bobwhite chicks relative to noncontingent exposure. Vicarious exposure appears, however, to produce more nonspecific learning (c.f. Heyes, 1994) compared with direct, contingent exposure. These results corroborate the findings of a growing body of comparative studies demonstrating the powerful effect of stimulus contingency on behavioral and perceptual development. We conclude that precocial embryos and hatchlings likely play a far more active role in directing their own perceptual development than has generally been acknowledged (c.f. Matsushima, Izawa, Aoki, & Yanagihara, 2003; ten Cate, 1989a). Further study is needed, however, to explore the generalizability of these findings to other stimuli and contexts, including the prenatal acquisition of preferences by avian embryos (see Gottlieb, 1971).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant RO1-MH62225 and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant RO1-HD048432 to Robert Lickliter. Portions of this work were conducted to fulfill requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Psychology at Florida International University.

We thank Susan Schneider, Lorraine Bahrick, and Mary Levitt for helpful feedback on an earlier version of the article and Donald Llopis for programming assistance.

Footnotes

Portions of these data were presented at the annual meetings of the International Society for Developmental Psychobiology, Washington, District of Columbia, November 2005; the Comparative Cognition Society, Melbourne, Florida, March 2006; and the Association for Behavior Analysis, Atlanta, Georgia, June 2006.

References

- Baker JA, Bailey ED. Ontogeny of the separation call in northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) Canadian Journal of Zoology. 1987;65:1016–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson PPG. What must be known in order to understand imprinting? In: Heyes C, Huber L, editors. The evolution of cognition. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2000. pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson PPG, Reese EP. Reinforcing properties of conspicuous objects before imprinting has occurred. Psychonomic Science. 1968;10:379–380. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson PPG, Reese EP. The reinforcing properties of conspicuous stimuli in the imprinting situation. Animal Behaviour. 1969;17:692–699. [Google Scholar]

- Beulig A, Dalezman JJ. Observational learning of imprinting behavior in Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 1992;30:209–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bolhuis JJ, Johnson MH. Effects of response-contingency and stimulus presentation schedule on imprinting in chicks (Gallus gallus domesticus) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1988;102:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bolhuis JJ, Van Kampen HS. An evaluation of auditory learning in filial imprinting. Behaviour. 1992;122:195–230. [Google Scholar]

- Burt J. Syrinx-PC: A Windows program for spectral analysis, editing, and playback of acoustic signals (Version 2.4s) [Computer software] 2005 Retrieved April 28, 2005, from http://www.syrinxpc.com/

- Campbell BA, Pickleman JR. The imprinting object as a reinforcing stimulus. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1961;54:592–596. doi: 10.1037/h0045435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania AC. Learning. 3rd ed. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Eacker JN, Meyer ME. Behaviorally produced illumination change by the chick. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1967;63:539–541. doi: 10.1037/h0024624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CS. Of ducklings and Turing machines: Interactive playbacks enhance subsequent responsiveness to conspecific calls. Ethology. 1991;89:125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Foushée R, Lickliter R. Early visual experience affects postnatal auditory responsiveness in bobwhite quail (Colinus virginianus) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2002;116:369–380. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.116.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaioni SJ, Hoffman HS, DePaulo P, Stratton VN. Imprinting in older ducklings: Some tests of a reinforcement model. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1978;6:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein M, King AP, West MJ. Social interaction shapes babbling: Testing parallels between birdsong and speech. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:8030–8035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332441100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb G. Development of species identification in birds: An enquiry into the prenatal determinants of perception. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie ER. The psychology of learning. Harper; New York: 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Harshaw C, Schneider SM, Lickliter R. [Inter-call interval and auditory preference in Northern bobwhite hatchlings] 2005. Unpublished raw data. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton MB, Miller DB, Goodwin DG. Species-specific auditory discrimination in bobwhite quail neonates. Developmental Psychobiology. 1978;11:13–21. doi: 10.1002/dev.420110106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyes CM. Social learning in animals: Categories and mechanisms. Biological Reviews. 1994;69:207–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185x.1994.tb01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HS, Schiff D, Adams J, Searle JL. Enhanced distress vocalization through selective reinforcement. Science. 1966 January 21;151:352–353. doi: 10.1126/science.151.3708.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honeycutt H, Lickliter R. Order-dependent timing of unimodal and multimodal stimulation affects prenatal auditory learning in bobwhite quail embryos. Developmental Psychobiology. 2001;38:1–10. doi: 10.1002/1098-2302(2001)38:1<1::aid-dev1>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honeycutt H, Lickliter R. Prenatal experience and postnatal perceptual preferences: Evidence for attentional-bias in bobwhite quail embryos (Colinus virginianus) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2002;116:270–276. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.116.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbert SH. Pseudoreplication and the design of ecological field experiments. Ecological Monographs. 1984;54:187–211. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MH, Bolhuis JJ, Horn G. Interaction between acquired preferences and developing predispositions during imprinting. Animal Behaviour. 1985;33:1000–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Lickliter R, Bahrick LE, Honeycutt H. Intersensory redundancy facilitates prenatal perceptual learning in bobwhite quail embryos. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:15–23. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lickliter R, Dyer A, McBride T. Perceptual consequences of early social experience in precocial birds. Behavioural Processes. 1993;30:185–200. doi: 10.1016/0376-6357(93)90132-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lickliter R, Gottlieb G. Social interaction with siblings is necessary for the visual imprinting of species-specific maternal preference in ducklings. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1985;99:371–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lickliter R, Hellewell T. Contextual determinants of auditory learning in bobwhite quail embryos and hatchlings. Developmental Psychobiology. 1992;25:17–31. doi: 10.1002/dev.420250103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz K. Der Kumpan in der Umwelt des Vogels. Journal für Ornithologie. 1935;83:137–213. 289–413. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz K. The companion in the bird’s world. Auk. 1937;54:245–273. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima T, Izawa E, Aoki N, Yanagihara S. The mind through chick eyes: Memory, cognition and anticipation. Zoological Science. 2003;20:395–408. doi: 10.2108/zsj.20.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer ME. Light onset or offset contingencies within a simple or complex environment. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1968;66:542–544. doi: 10.1037/h0026367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuringer AJ. Superstitious key pecking after three peck-produced reinforcements. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1970;13:127–134. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1970.13-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepperberg IM. Vocal learning in Grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus): Effects of social interaction, reference, and context. Auk. 1994;111:300–313. [Google Scholar]

- Pepperberg IM. Allospecific vocal learning by Grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus): A failure of videotaped instruction under certain conditions. Behavioural Processes. 1998;42:139–158. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(97)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson N. Control of behavior by presentation of an imprinted stimulus. Science. 1960 November 11;132:1395–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.132.3437.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. “Superstition” in the pigeon. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1948;38:168–172. doi: 10.1037/h0055873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staddon JER, Simmelhag VL. The “superstition” experiment: A reexamination of its implications for the principles of adaptive behavior. Psychological Review. 1971;78:3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes AW. Behavior of the bobwhite, Colinus virginianus. Auk. 1967;84:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Stoumbos JA. Effects of altered prenatal auditory experiences on postnatal auditory preferences in bobwhite quail chicks. Virginia Polytechnic Institute; Blacksburg, Virginia: 1990. Unpublished master’s thesis. [Google Scholar]

- ten Cate C. Does behavior contingent stimulus movement enhance filial imprinting in Japanese quail? Developmental Psychobiology. 1986;19:607–614. doi: 10.1002/dev.420190611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Cate C. Behavioral development: Toward understanding processes. In: Bateson PPG, Klopfer P, editors. Perspectives in ethology. Vol. 8. Plenum Press; New York: 1989a. pp. 243–269. [Google Scholar]

- ten Cate C. Stimulus movement, hen behaviour and filial imprinting in Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) Ethology. 1989b;82:287–306. [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake W, Lucas GA. The basis of superstitious behavior: Chance contingency, stimulus substitution, or appetitive behavior? Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1985;44:279–299. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1985.44-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BA. The critical dimensions of the response-reinforcer contingency. Behavioural Processes. 2001;54:111–126. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(01)00153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]