Abstract

Background

The urgency and level of care provided for acute coronary syndromes partially depends on the symptoms manifested.

Objectives

To detect differences between women and men in the type, severity, location, and quality of symptoms across the 3 clinical diagnostic categories of acute coronary syndromes (unstable angina, myocardial infarction without ST-segment elevation, and myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation) while controlling for age, diabetes, functional status, anxiety, and depression.

Methods

A convenience sample of 112 women and 144 men admitted through the emergency department and hospitalized for acute coronary syndromes participated. Recruitment took place at 2 urban teaching hospitals in the Midwest. Data were collected during structured interviews in each patient’s hospital room. Forty-eight symptom descriptors were assessed. Demographic characteristics, health history, functional status, anxiety, and depression levels also were measured.

Results

Regardless of clinical diagnostic category, women reported significantly more indigestion (β = 0.25; confidence interval [CI] = 0.01–0.49), palpitations (β = 0.31; CI = 0.06–0.56), nausea (β = 0.37; CI = 0.10–0.65), numbness in the hands (β = 0.29; CI = 0.02–0.57), and unusual fatigue (β = 0.60; CI = 0.27–0.93) than men reported. Differences between men and women in dizziness, weakness, and new-onset cough did differ by diagnosis. Reports of chest pain did not differ between men and women.

Conclusions

Women with acute coronary syndromes reported a higher intensity of 5 symptoms (but not chest pain) than men reported. Whether differences between the sexes in less typical symptoms are clinically significant remains unclear.

Notice to CE enrollees.

A closed-book, multiple-choice examination following this article tests your understanding of the following objectives:

Describe acute coronary syndromes.

Recognize how symptoms differ in women and men with acute coronary syndromes.

Understand the results, strengths, and limitations of this study.

To read this article and take the CE test online, visit www.ajcconline.org and click “CE Articles in This Issue.” No CE test fee for AACN members.

More than 13 million persons in the United States live with coronary heart disease (CHD) and are at risk for acute coronary syndromes (ACS).1 Although recent large-scale trials, including the Women’s Health Initiative2 and the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation,3 have shed valuable light on patients’ characteristics, diagnosis, and outcomes in women, differences in symptoms between women and men in the same cohort of patients have been examined in only a few studies. Assessment of such differences is important because the urgency and level of care provided partially depend on the clinical presentation.

Although history, risk factor profile, findings on physical examination, stability of clinical manifestations, risk of a life-threatening complication, and diagnostic testing are equally important in the diagnosis and treatment of ACS, the symptom experience determines whether or not a person seeks treatment in an expeditious manner or seeks treatment at all. The symptom description also affects the care provided by emergency medical services personnel4–6 and emergency department triage nurses if emergency medical services personnel are not used.7

Factors That May Influence Symptoms of ACS

Sex of the Patient

Previous studies8–14 of patients with ACS indicated that women experience more back pain, dyspnea, indigestion, nausea/vomiting, and weakness than men do. Men were more likely than women to have chest pain.15–17 Of note, the collection of symptom data in a number of these studies was part of an examination of prehospital delay times,12 treatment outcomes,14 predictive value for diagnoses,8 and public awareness interventions.9 Symptoms across the 3 clinical diagnoses of ACS and between women and men in the same cohort generally have not been examined.16 Thus, comprehensive descriptive data on this topic are needed. Large epidemiological data sets18,19 have consistently indicated that women with a diagnosis of CHD are older, have a higher incidence of diabetes, have reduced functional status, and are more likely to have depression than are men.

Women with acute coronary syndromes have more back pain, dyspnea, indigestion, nausea and vomiting, and weakness than do men.

Age of the Patient

Numerous studies have substantiated that women are older than men when CHD is diagnosed.1 In the Third International Study of Infarct Survival Collaborative Group (ISIS-3) trial,20 among the 36 080 patients enrolled, women were significantly older than men when ACS was diagnosed. Differences between the sexes were examined in 12 142 patients participating in the Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes IIb (GUSTO IIb) study.21 Results indicated that women were a mean of 8 years older than were men (P < .001) when ACS was diagnosed. Perhaps differences in the symptoms of ACS can be explained by women’s older ages rather than by their sex.

Diabetes

Diabetes was chosen as a variable for this study for several reasons. First, the prevalence of diabetes is significantly higher in women with ACS than in men with ACS. The ISIS-3 data20 indicated that women with acute myocardial infarction had diabetes more often than men had diabetes across all age groups. Similar findings were reported in the GUSTO IIb trial.21 First, the rate of diabetes in women was significantly higher than the rate in men at each level of ACS, including unstable angina, myocardial infarction without ST-segment elevation, and myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. Second, patients with diabetic neuropathy had impaired perception of cardiac pain.22 Patients with diabetes also had higher frequencies of silent exertional ischemia and silent myocardial infarction.23,24 Finally, diabetes is a powerful risk factor for CHD in both women and men; however, diabetes confers a 3- to 5-fold increase in risk of CHD mortality for women vs a 3-fold increase for men.25 We hypothesized that differences in symptoms between women and men, if present, would be explained by the higher prevalence of diabetes in women.

Mood Disorders

Mood disorders are a psychological factor that may help explain differences between women and men in symptoms of ACS. Depression is 3 times more common in women than in men and is a particularly serious problem in elderly women.26 An extensive review of prospective studies27,28 yields support for depression as a cardiac risk factor.

Mood disorders may also adversely affect the progression and outcome of CHD. Data have indicated that the presence of major depression in patients with a recent diagnosis of ACS more than doubled the risk of death due to cardiac disease.29 It has been hypothesized that the symptoms for depression and anxiety, particularly chest pain and tachycardia, can mimic the symptoms of ACS. This confounding clinical picture of similar symptoms between depression, anxiety, and ACS warrants further study.

Goals of the Study

Available data were insufficient to determine whether reported differences in symptoms are clinically significant. A study with a large sample of patients and use of a structured interview format was needed to detect any sex- or diagnosis-related differences in symptoms so that appropriate assessment, diagnostic, and treatment strategies could be evaluated and symptom management after discharge could be improved.

Nearly half of all patients indicated that symptoms were triggered by causes other than exertion, emotional upset, or rest.

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to determine if symptoms differed between women and men across the continuum of ACS diagnoses when age, diabetes, functional status, anxiety, and depression were controlled for. The specific aims were to do the following:

Determine the type, severity, location, and quality of symptoms reported by women and men admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of ACS

Assess whether symptoms differed among the 3 clinical diagnoses (unstable angina, myocardial infarction without ST-segment elevation, and myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation)

Detect any relationship between functional status in the week preceding hospitalization and the symptoms of ACS

Examine levels of anxiety and depression immediately before hospitalization

Describe risk factors, health history, and sociodemographic differences between women and men and between diagnostic groups

Organizing Framework

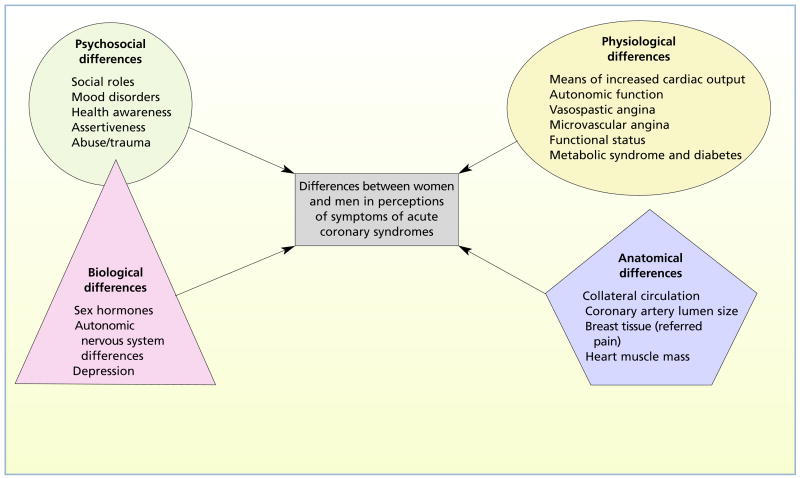

On the basis of an extensive review of the literature, we constructed an original organizing framework for the study. Type, severity, location, and quality of symptoms may vary because of psychosocial, physiological, anatomical, and biological differences between women and men.30,31 The framework representing the multidimensional factors that may explain differences between women and men in perceptions of symptoms of ACS is shown in Figure 1. The 4 domains are represented by different geometric shapes because we do not know if all contribute equally to the perception of symptoms. We think that biological factors influence psychosocial differences between women and men; therefore, those factors overlap in the figure. Variables contained in the framework that were measured in this study included mood disorders (psychosocial domain), functional status and diabetes (physiological domain), and depression (biological domain).

Figure 1.

Framework to explain differences between women and men in perception of symptoms of acute coronary syndromes.

Methods

Sample and Setting

A convenience sample of patients hospitalized with an admitting diagnosis of ACS was recruited from the cardiac step-down units of 2 referral teaching hospitals in the Midwest. Data collection sites were chosen to recruit a heterogeneous sample representative of the local population and to recruit adequate numbers of minorities. Patients were eligible for study if they were admitted through the emergency department with a diagnosis of ACS at least 12 hours before they were interviewed, were at least 21 years of age, were fluent in English, were pain-free, had stable vital signs, and had adequate cognitive capacity.

Patients were excluded if they had any history of cocaine use, documentation of prior heart failure, or elevated levels of brain natriuretic peptide. We hypothesized that the symptom experience might vary for patients with a history of cocaine use because ischemia in such patients is more likely to be precipitated by vasoconstriction, tachycardia, systemic hypertension, and increased myocardial oxygen consumption than by the more common and chronic pathophysiological processes associated with obstructive coronary artery disease.32 Patients with a history of heart failure were excluded because many of the symptoms of heart failure, including dyspnea and unusual fatigue, are similar to the symptoms of ACS.

Patients were not excluded if they had a history of ACS. It is not known if a history of ACS or stable CHD would affect the description of symptoms, although it is possible that prior knowledge of symptoms, experience with illness, or prior interventions would sensitize patients to somatic symptoms. After the patients were discharged, final diagnoses were retrieved from their medical records. Sixteen patients had a noncardiac discharge diagnosis (a code other than 410 or 411 in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision) and were excluded from analyses, resulting in a final sample of 112 women and 144 men (n = 256).

Instruments

The Symptoms of Acute Coronary Syndromes Inventory, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) classification of angina, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and a medical record review form developed for this study were used to collect data.

Symptoms of Acute Coronary Syndromes Inventory

The Symptoms of Acute Coronary Syndromes Inventory, based on an extensive review of the literature, was developed for a previous study on unstable angina.11 Published data reveal that the symptoms of ACS are a multidimensional construct. Consequently, the inventory consists of 3 parts describing the type, severity, location, and quality of symptoms. Part A includes 20 different symptoms described in the literature33–35 that may occur in patients with acute chest pain, myocardial infarction, or unstable angina. Symptoms are measured on a 5-point scale. Patients indicate that they either did not experience the symptom (0) or they rate the severity of each symptom as mild (1), moderate (2), severe (3), or very severe (4).

Women had more pain in the jaw and neck than did men.

Part B includes 14 locations in the body where pain or discomfort may be experienced, and part C contains 14 descriptors of the quality of pain or discomfort. All items in parts B and C are measured dichotomously (yes/no). The content validity index for the entire instrument has been previously established at 0.88 (P < .05).11 Before the start of this study, the instrument was again reviewed by 5 content experts and the computed content validity index was 0.94 (P < .05).

Chest pain was most frequently reported, but 21% of women and 10% of men experienced none.

Patients did not add additional symptoms when given the opportunity to do so during the interview, adding support for the construct validity of the instrument as a comprehensive measure of the symptoms of ACS. Finally, patients were asked about general characteristics of their symptoms, including the temporal nature of their pain, whether they treated symptoms, if they had ever experienced similar symptoms, what they thought triggered their symptoms, and the severity of their worst symptom.

CCS Classification of Angina

The CCS classification of angina was used to assess patients’ level of physical function.36 The reliability and validity of the classification system have been reported extensively.36 We hypothesized that patients in a higher CCS class would report more severe symptoms and a greater number of symptoms.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is a self-assessment tool designed to measure the 2 most common manifestations of mood disorders: anxiety and depression.37 The instrument includes 7 succinct questions for each subscale. Patients respond on a 4-point scale. The response items vary from question to question but essentially range from not at all to very often. In an attempt to avoid response bias, the order of responses is varied. The first response on some items indicates maximum severity and on others indicates minimum severity. The instrument has established reliability and validity for use in cardiovascular patients.38–40

Absence of chest pain may lead to delayed or inadequate treatment.

Procedure

Data were collected from July 2003 to August 2005 after approval was received from the appropriate institutional review boards. A physician or a primary nurse approached each eligible patient and asked for permission to give the patient’s name to the researchers in accordance with the guidelines of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. When permission was obtained by hospital staff, a member of the research team approached the patient and explained the study. Written informed consent was obtained from patients who agreed to participate. Cognitive function was assessed during the consent process. All interviews were conducted in the patients’ hospital rooms. Instruments were designed to be self-administered; however, all responses were recorded by the investigators because of the acuteness of the patients’ illnesses.

The names of 282 patients were supplied by hospital staff. A total of 6 women and 4 men declined to participate because of fatigue, lack of interest, or refusal to sign the consent form. Of these 10 patients, 6 were black, and their ages were 40 to 85 years. The remaining 272 patients gave written consent and completed the interview. A total of 16 patients were excluded because they had a noncardiac discharge diagnosis; this exclusion resulted in a final sample of 256 patients.

Patients were asked to report only those symptoms that brought them to the emergency department on this admission. This restriction was used to reduce threats to internal validity caused by inclusion of prodromal symptoms, symptoms experienced during a previous episode of ACS, or symptoms that occurred as a result of another illness. Confidentiality was ensured because all patients’ rooms are private in the units where data were collected. Diagnoses, physical findings, test results, health history, and risk factors were abstracted from medical records at the conclusion of the interview.

Data Analyses

Data were coded and entered into SPSS, version 13 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). All tests were 2-sided, and statistical significance was set at P = .05. Descriptive statistics were computed by using a χ2 test for categorical data and t tests for interval level data. Simple linear regression was used to determine whether women and men differed in reported symptoms of ACS after clinical diagnosis, age, diabetes status, functional status, anxiety, and depression were controlled for. Logistic regression analyses were used to determine whether the sex of the patient was predictive of symptoms and to control for the same possible covariates. Model selection was used to find the best-fit model. This selection involved testing each of the covariates separately in a model that included the interaction between each patient’s sex and diagnosis. All covariates that were significant at the .20 level or less were included in the model, and backwards selection was used to identify the best model.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Women accounted for 44% of the sample. Women were significantly older than men (t = 2.79, P =.01) and ranged in age from 39 to 97 years (mean, 67.1; SD, 13.2). Men ranged in age from 24 to 90 years (mean, 62.3; SD, 13.6). More than 25% of patients were members of minority groups, predominantly black. Patients were well educated; 45% of the women and 37% of the men had some college or had college degrees. The groups of women and men did not differ in racial composition (χ2 = 5.12; P = .28) or levels of education (χ2 = 7.14; P = .50). Women were more likely to have lower incomes (χ2 = 19.41; P = .02) and to be unmarried (χ2 = 40.4; P < .01; Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of women and men with acute coronary syndromes

| Womena (n = 112)

|

Menb (n = 144)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No. | % | No. | %c | P |

| Type of acute coronary syndrome | .64 | ||||

| Unstable angina | 38 | 34 | 50 | 35 | |

| Myocardial infarction without ST-segment elevation | 40 | 36 | 44 | 31 | |

| Myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation | 34 | 30 | 50 | 35 | |

|

| |||||

| Race/ethnicity | .28 | ||||

| Black | 27 | 24 | 24 | 17 | |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 80 | 71 | 111 | 77 | |

| Hispanic | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | |

| Native American | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

|

| |||||

| Education | .50 | ||||

| Less than high school | 27 | 24 | 40 | 28 | |

| High school diploma | 35 | 31 | 51 | 35 | |

| More than high school | 50 | 45 | 53 | 37 | |

|

| |||||

| Income,d $ | .02 | ||||

| ≤20 000 | 48 | 43 | 36 | 25 | |

| 20 001–50 000 | 35 | 31 | 56 | 39 | |

| >50 000 | 12 | 11 | 35 | 24 | |

|

| |||||

| Marital status | <.01 | ||||

| Single | 12 | 11 | 22 | 15 | |

| Married | 44 | 39 | 92 | 64 | |

| Divorced | 11 | 10 | 18 | 12 | |

| Widowed | 45 | 40 | 12 | 8 | |

Mean (SD) of ages for women was 67.1 (13.2) years with a range from 39 to 97 years.

Mean (SD) of ages for men was 62.3 (13.6) years with a range from 24 to 90 years.

Because of rounding, not all percentages for men total 100.

Income data were missing for 15% of women and 12% of men.

Health History and Risk Factors

Health history and risk factors were recorded during each patient’s interview and verified in the medical record. If a discrepancy was found between data provided by a patient and data found in the medical record, data provided during the patient’s interview were analyzed. Nearly half (47%) of the total sample (women and men) had been told they had heart disease before the current admission (Table 2). Women (43%) and men (51%) did not differ significantly in history of CHD (χ2=1.55; P =.26). No significant differences between the sexes were found in prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, exercise, family history of early CHD, or mean body mass index (index calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). Patients were placed into the following categories on the basis of mean body mass index: (1) underweight (index <18.5), (2) normal weight (18.5–24.9), (3) overweight (25–29.9), (4) obese (30–39.9), and (5) morbidly obese (>40). When analyzed categorically, women were more likely than men to be morbidly obese (χ2 = 17.9; P = .01). Men were more likely than women to be current smokers (32% vs 21%; χ2=4.17; P =.04). As expected, 79% of women were postmenopausal.

Table 2.

General characteristics of symptoms, health history, and risk factors: women vs mena

| Women (n = 112)

|

Men (n = 144)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No. | % | No. | % | P |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Constant | 69 | 62 | 86 | 60 | .66 |

| Self-treated | 67 | 60 | 91 | 63 | .34 |

| Similar to past symptoms | 63 | 56 | 82 | 57 | .51 |

| Symptoms brought on by | |||||

| Exertion | 12 | 11 | 37 | 26 | .01 |

| Emotional upset | 26 | 23 | 28 | 19 | .28 |

| Rest | 23 | 21 | 19 | 13 | .08 |

| Other causes | 65 | 58 | 73 | 51 | .15 |

| Severity of chest pain, mean (SD), scale 0–10 | 6.08 | (3.37) | 6.84 | (3.01) | .06 |

| Severity of worst symptom, mean (SD), scale 0–10 | 7.56 | (2.54) | 7.13 | (2.89) | .21 |

| Total No. of symptoms, mean (SD) | 8.36 | (3.62) | 7.48 | (3.65) | .06 |

|

| |||||

| Health history | |||||

| Coronary heart disease | 48 | 43 | 73 | 51 | .26 |

| Early family history of coronary heart disease | 56 | 50 | 58 | 40 | .29 |

|

| |||||

| Risk factors | |||||

| Diabetes | 42 | 38 | 42 | 29 | .16 |

| Smoking | 23 | 21 | 46 | 32 | .04 |

| Hypertension | 82 | 73 | 90 | 63 | .18 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 57 | 51 | 84 | 58 | .26 |

| Regular exercise | 40 | 36 | 55 | 38 | .68 |

| Body mass index,b mean (SD) | 29.86 | (7.7) | 29.00 | (5.2) | .32 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 29 | 26 | 27 | 19 | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 25 | 22 | 56 | 39 | |

| Obese (30–39.9) | 40 | 36 | 56 | 39 | |

| Morbidly obese (>40) | 14 | 13 | 5 | 3 | <.01 |

| Postmenopausal | 88 | 79 | |||

Values are number and percentage unless otherwise indicated. Because of rounding, not all percentages total 100. Also, some patients gave more than a single answer for the cause of symptoms.

Calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Functional Status, Anxiety, and Depression

Functional status in the week before hospitalization was measured by using the CCS classification of angina. No association was found between sex and CCS class. Most women (73%) and men (83%) were class 1 or 2. Women were disproportionately represented in classes 3 and 4 (27% vs 17%; Fisher exact test = 5.93; P = .12); however, this difference was not significant. Logistic regression models were tested to determine if any linear association could be detected between diagnosis and CCS class. We found no unadjusted effect for diagnosis (P = .23) and no effect after age, diabetes status, anxiety, and depression were adjusted for (P = .42).

Anxiety and depression were assessed for the 2-week period preceding admission. Women scored significantly higher than men scored on the anxiety and depression subscales of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Mean anxiety scores were 7.71 (SD, 9.77) for women and 5.76 (SD, 3.66) for men (t = 2.21; P < .05). Mean depression scores were 5.02 (SD, 3.69) for women and 3.95 (SD, 3.92) for men (t = 2.22; P = .03). Although anxiety and depression scores were significantly different between men and women, the scores were not in the clinically significant range. According to Zigmond and Snaith,37 a score of 0 to 7 is not clinically significant, a score of 8 to 10 is borderline, and a score greater than 10 indicates a definite mood disorder.

Symptom Characteristics by Sex and Diagnosis

Most patients (61%) said their symptoms were constant; that they attempted to treat symptoms with home remedies (62%), most often acetaminophen; and that they had experienced similar symptoms in the past (57%). The data are broken down by the patient’s sex in Table 2. Differences in these variables were not significant. Patients were asked if their symptoms were brought on by exertion, emotional upset, rest, or other causes (Table 2). Men were more likely to report that their symptoms were brought on by exertion. Interestingly, more than half of all patients responded that symptoms were triggered by causes other than exertion, emotional upset, or rest.

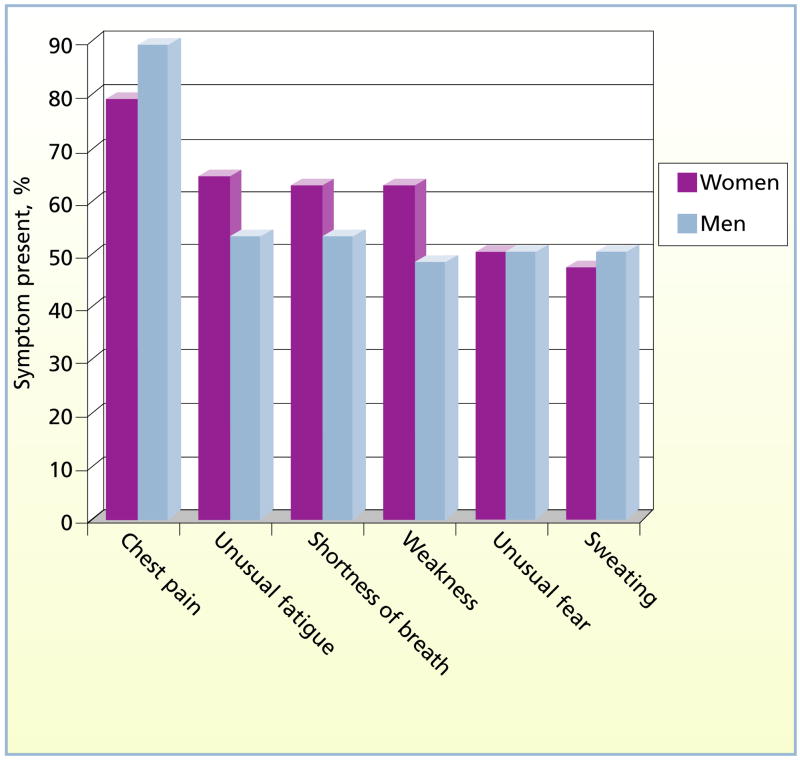

Men reported more severe chest pain than women did, but mean scores did not differ significantly. Patients were also asked to rate the severity of the worst symptom on a scale of 1 to 10. This question was posed because not all patients experienced chest pain. Scores were higher in women, but the difference was not significant. Mean number of symptoms experienced was slightly higher for women than for men, but the difference was not significant. Symptom type, location, and quality were rank ordered to identify typical and atypical patterns for this cohort of patients. The 3 most frequently reported symptoms for both women and men were chest pain, unusual fatigue, and shortness of breath (Figure 2). Although chest pain and shortness of breath are well known to clinicians and the general public as typical symptoms, unusual fatigue is not.

Figure 2.

Frequently reported symptoms of acute coronary syndromes in women and men.

Differences in Symptom Type

Scores for 5 symptoms were significantly higher in women than in men. Women reported significantly more indigestion (β = 0.25; P = .04), palpitations (β = 0.31; P = .02), nausea (β = 0.37; P < .01), numbness in the hands (β = 0.29; P = .03), and unusual fatigue (β= 0.60; P < .01) that did not differ across diagnosis (Table 3). In addition, women experienced more loss of appetite, but again the difference was not significant. No interaction effect was found for symptoms and race.

Table 3.

Differences between women and men in symptoms of acute coronary syndromes

| Symptom | βa | P | 95% confidence interval | Adjusted for |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigestion | 0.25 | .04 | 0.01 to 0.49 | Depression |

| Palpitations | 0.31 | .02 | 0.06 to 0.56 | Age |

| Nausea | 0.37 | <.01 | 0.10 to 0.65 | Age, anxiety |

| Numbness in hands | 0.29 | .03 | 0.02 to 0.57 | Age, Canadian Cardiovascular Society class of angina |

| Unusual fatigue | 0.60 | <.01 | 0.27 to 0.93 | Age, diabetes |

| Loss of appetite | 0.28 | <.06b | −0.01 to 0.56 |

Women were more likely than men to experience all of these symptoms.

Women reported loss of appetite more often than men did, but the difference was not significant.

Three symptoms (dizziness, weakness, and cough) did differ between men and women for some diagnoses (Table 4). Men with myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation experienced higher levels of dizziness (P < .01). Women with unstable angina were more likely to report weakness (P < .01) as were women with myocardial infarction without ST-segment elevation (P = .03). Finally, women with myocardial infarction without ST-segment elevation reported more new coughing (P < .01).

Table 4.

Differences between women and men in symptoms of acute coronary syndromes across diagnostic groups

| Symptom | Diagnosis | β | P | 98.33% confidence intervala |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dizziness | Unstable angina | −0.23 | .32 | −0.78 to 0.32 |

| Myocardial infarction without ST-segment elevation | 0.08 | .72 | −0.47 to 0.64 | |

| Myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation | 0.84b | <.01 | 0.27 to 1.41 | |

|

| ||||

| Weaknessc | Unstable angina | −0.77d | <.01 | −1.44 to −0.10 |

| Myocardial infarction without ST-segment elevation | −0.62d | .03 | −1.29 to 0.06 | |

| Myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation | 0.26 | .37 | −0.43 to 0.96 | |

|

| ||||

| Cough | Unstable angina | 0.04 | .79 | −0.30 to 0.37 |

| Myocardial infarction without ST-segment elevation | −0.48d | <.01 | −0.82 to −0.14 | |

| Myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation | −0.08 | .57 | −0.43 to 0.27 | |

Confidence intervals use Bonferroni adjustment and thus are 98.33% rather than the usual 95%.

Denotes effect for men.

All values for weakness are adjusted for Canadian Cardiovascular Society class of angina.

Denotes effect for women.

Differences Between Women and Men in Location and Quality of Symptoms

Patients were asked to indicate where they felt pain or discomfort and the quality of their pain or discomfort. Lists of location of pain and quality of pain each included 14 descriptors (Table 5). Patients also had the opportunity to describe any other areas in the body where symptoms were experienced and to describe the nature of their pain or discomfort in their own words. No other descriptors were offered. Women and men reported similar locations and quality descriptors for their pain and discomfort with few exceptions. Women reported more pain in the jaw (χ2=5.86; P =.02) and pain in the neck (χ2=6.4; P = .01) than men reported. Women also were more likely than men to describe their chest pain as a feeling of fullness (χ2 = 5.3; P = .03).

Table 5.

Location and quality of symptoms reported by women vs men

| No. (%) of patients reporting

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Location/quality of symptom | Women | Men | P |

| Location | |||

| 1. Jaw | 27 (24) | 18 (12) | .02 |

| 2. Neck | 41 (37) | 32 (22) | .01 |

| 3. Throat | 24 (21) | 31 (22) | .99 |

| 4. Left shoulder | 47 (42) | 53 (37) | .40 |

| 5. Right shoulder | 28 (25) | 24 (17) | .10 |

| 6. Left arm | 45 (40) | 61 (42) | .73 |

| 7. Right arm | 25 (22) | 30 (21) | .77 |

| 8. Left part of chest | 64 (57) | 81 (56) | .89 |

| 9. Center part of chest | 84 (75) | 116 (81) | .29 |

| 10. Right part of chest | 41 (37) | 49 (34) | .69 |

| 11. Upper part of back | 38 (34) | 37 (26) | .17 |

| 12. Midback | 27 (24) | 25 (17) | .21 |

| 13. Teeth | 13 (12) | 8 (6) | .11 |

| 14. Upper part of abdomen | 35 (31) | 37 (26) | .33 |

|

| |||

| Quality | |||

| 1. Crushing | 29 (26) | 36 (25) | .89 |

| 2. Pressure | 86 (77) | 106 (74) | .66 |

| 3. Burning | 27 (24) | 48 (33) | .13 |

| 4. Tingling | 36 (32) | 36 (25) | .21 |

| 5. Tightness | 74 (66) | 104 (72) | .34 |

| 6. Heaviness | 65 (58) | 82 (57) | .90 |

| 7. Fullness | 43 (38) | 36 (25) | .03 |

| 8. Squeezing | 29 (26) | 49 (34) | .17 |

| 9. Stabbing | 22 (20) | 28 (19) | >.99 |

| 10. Dull | 50 (45) | 62 (43) | .80 |

| 11. Sharp | 45 (40) | 63 (44) | .61 |

| 12. Aching | 64 (57) | 78 (54) | .70 |

| 13. Cramping | 22 (20) | 36 (25) | .37 |

| 14. Constricting | 42 (38) | 70 (49) | .08 |

Discussion

Women were older, had lower incomes, were more likely to be unmarried, were more likely to be morbidly obese, and had higher mean anxiety and depression scores than did men. These factors have previously been associated with poorer outcomes for women with CHD.41–44 The age range for this sample (24–97 years) was a strength of this study. Recruitment of a heterogeneous sample, including a wide age range and representation of minority groups, improves the generalizability of the study findings by ensuring that the sample is representative of the population. The mean age of 67 years for women also provides valuable data on symptoms of ACS in older women.

Although men attributed the onset of their symptoms to exertion more frequently than women did, most women and men ascribed the onset of symptoms to other causes. The attribution of cause may influence how and when patients make a decision to seek emergent care or how to manage their disease once it is diagnosed.45 These issues require further exploration.

Our findings varied from those of previous studies10,11,13,16,17; we found no differences between women and men in back pain, dyspnea, nausea/vomiting, or weakness. Of note, in our study, women and men did not differ in the classic symptoms of chest pain, diaphoresis, and shortness of breath. Published reports have described equivocal findings about these symptoms. Some authors17 have reported that men experience more chest pain and diaphoresis, and others have indicated that women experience more shortness of breath10 and back pain.11 Still other authors,16 however, have found no differences.

Women in our study were more likely to experience indigestion, palpitations, nausea, numbness in the hands, and unusual fatigue that did not differ across diagnosis. Of note, these symptoms are considered atypical because they vary from those in the traditional male model, are vague, and are common to many less serious health problems. This situation puts both women and men at risk for delayed diagnosis and treatment if they do not experience typical symptoms with chest pain, but it confers greater risk to women in this sample, who experienced these symptoms more often. Differences between the sexes across diagnosis were minimal and most likely of no consequence.

As expected, chest pain was the most frequently reported symptom. However, the fact that 21% of women and 10% of men experienced no chest pain is a concern. Some evidence23,41,46,47 indicates that patients with silent ischemia are more likely to have the disease go undiagnosed or be misdiagnosed, are less likely to receive reperfusion therapy, and have poorer outcomes. Not surprisingly, patients with myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) study23 were less likely to receive percutaneous coronary intervention or fibrinolysis if their symptoms were atypical (no chest pain). It is possible that diagnosis and treatment might be compromised for those with unstable angina or myocardial infarction without ST-segment elevation because initial diagnosis is based on clinical presentation and history. Because the diagnosis of myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation by means of electrocardiograms and cardiac markers is so straightforward, it may be assumed that treatment would not be affected by the initial symptoms. However, the GRACE findings suggest that the clinical features are equally important for all levels of ACS because diagnostic testing is a judgment call based on these features. Furthermore, GRACE findings indicate that the absence of chest pain may lead to delayed or inadequate treatment after presentation to the emergency department even for those experiencing myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation.

Our results could facilitate the development of educational material to guide patients with atypical symptoms to seek care and an assessment tool that could be used by triage nurses in practice. Nurses are often patients’ first contact in the healthcare system and could speed up diagnostic testing, expedite appropriate treatments, and improve patients’ outcomes. Concise, evidence-based assessment tools could be developed to detect symptoms that are more likely for women, men, and patients with diabetes. Identification of the symptom differences described here and in prior studies could also lead to improved management of symptoms after discharge. The differences in symptoms for the 3 clinical diagnoses of ACS require further exploration to determine if the differences we found can be reproduced.

Limitations

The study began 3 months after the implementation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Therefore, all potential patients were identified by nursing personnel or attending physicians. Each potential participant was approached by his or her primary care nurse and asked permission for the participant’s name to be released to the researchers. Because all potential participants were referred to us by nursing or medical staff, we have no way of knowing if this method resulted in selection bias. Possibly, the names of some patients who were eligible for study were not released to us.

In addition, the sample was restricted to patients who were admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of ACS and therefore did not include patients who did not seek treatment or who had silent ischemia. Sampling bias is a limitation with the use of a convenience sample. This bias presents a potential threat to the internal validity of the findings. However, use of a probability sample is not possible in an acutely ill, hospitalized population. Strategies such as recruiting 7 days a week during a 12-hour period (8 am to 8 pm) may have contributed to a more representative sample of the population than would otherwise occur with a convenience sample.

Acknowledgments

We thank research assistants Teresa Fadden, Anne Bourguignon, and Martha Aregbesola for their assistance with this study.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research, grant R15 NR08870.

Footnotes

eLetters

Now that you’ve read the article, create or contribute to an online discussion about this topic using eLetters. Just visit www.ajcconline.org and click “Respond to This Article” in either the full-text or PDF view of the article.

To purchase electronic or print reprints, contact The InnoVision Group, 101 Columbia, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656. Phone, (800) 809-2273 or (949) 362-2050 (ext 532); fax, (949) 362-2049; e-mail, reprints@aacn.org.

References

- 1.Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006;113(6):e85–e151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.171600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Buchthal SD, et al. National Institutes of Health-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Prognosis in women with myocardial ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary disease: results from the National Institutes of Health–National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Circulation. 2004;109(24):2993–2999. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130642.79868.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lozzi L, Carstensen S, Rasmussen H, Nelson G. Why do acute myocardial infarction patients not call an ambulance? An interview with patients presenting to hospital with acute myocardial infarction symptoms. Intern Med J. 2005;35(11):668–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2005.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutchings CB, Mann NC, Daya M, et al. Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment Study. Patients with chest pain calling 9-1-1 or self-transporting to reach definitive care: which mode is quicker? Am Heart J. 2004;147(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(03)00510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGinn AP, Rosamond WD, Goff DC, Jr, Taylor HA, Miles JS, Chambless L. Trends in prehospital delay time and use of emergency medical services for acute myocardial infarction: experience in 4 US communities from 1987–2000. Am Heart J. 2005;150(3):392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arslanian-Engoren C. Patient cues that predict nurses’ triage decisions for acute coronary syndromes. Appl Nurs Res. 2005;18(2):82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everts B, Karlson BW, Wahrborg P, Hedner T, Herlitz J. Localization of pain in suspected acute myocardial infarction in relation to final diagnosis, age and sex, and site and type of infarction. Heart Lung. 1996;25(6):430–437. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(96)80043-4. [published correction appears in Heart Lung. 1997;26(3):176] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg R, Goff D, Cooper L, et al. Age and sex differences in presentation of symptoms among patients with acute coronary disease: the REACT Trial. Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment. Coron Artery Dis. 2000;11(5):399–407. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milner KA, Funk M, Richards S, Wilmes RM, Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM. Gender differences in symptom presentation associated with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(4):396–399. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeVon HA, Zerwic JJ. The symptoms of unstable angina: do women and men differ? Nurs Res. 2003;52(2):108–118. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200303000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meischke H, Larsen MP, Eisenberg MS. Gender differences in reported symptoms for acute myocardial infarction: impact on prehospital delay time interval. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16(4):363–366. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(98)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zucker DR, Griffith JL, Beshansky JR, Selker HP. Presentations of acute myocardial infarction in men and women. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(2):79–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maynard C, Weaver WD. Treatment of women with acute MI: new findings from the MITI registry. J Myocard Ischemia. 1992;4(2):27–37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milner KA, Vaccarino V, Arnold AL, Funk M, Goldberg RJ. Gender and age differences in chief complaints of acute myocardial infarction (Worcester Heart Attack Study) Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(5):606–608. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen W, Woods SL, Wilkie DJ, Puntillo KA. Gender differences in symptom experiences of patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(6):553–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arslanian-Engoren C, Patel A, Fang J, et al. Symptoms of men and women presenting with acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(9):1177–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Legato MJ, Gelzer A, Goland R, et al. Writing Group for the Partnership for Gender-Specific Medicine. Gender-specific care of the patient with diabetes: review and recommendations. Gend Med. 2006;3(2):131–158. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(06)80202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blomkalns AL, Chen AY, Hochman JS, et al. CRUSADE investigators. Gender disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: large-scale observations from the CRUSADE (Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes With Early Implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines) National Quality Improvement Initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(6):832–837. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malacrida R, Genoni M, Maggioni AP, et al. A comparison of the early outcome of acute myocardial infarction in women and men. The Third International Study of Infarct Survival Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(1):8–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801013380102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hochman JS, Tamis JE, Thompson TD, et al. Sex, clinical presentation, and outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes IIb Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(4):226–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907223410402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langer A, Freeman MR, Josse RG, Steiner G, Armstrong PW. Detection of silent myocardial ischemia in diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67(13):1073–1078. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90868-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brieger D, Eagle KA, Goodman SG, et al. GRACE Investigators. Acute coronary syndromes without chest pain, an underdiagnosed and undertreated high-risk group: insights from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Chest. 2004;126(2):461–469. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.2.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chico A, Tomas A, Novials A. Silent myocardial ischemia is associated with autonomic neuropathy and other cardiovascular risk factors in type 1 and type 2 diabetic subjects, especially in those with microalbuminuria. Endocrine. 2005;27(3):213–217. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:27:3:213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blendea MC, McFarlane SI, Isenovic ER, Gick G, Sowers JR. Heart disease in diabetic patients. Curr Diab Rep. 2003;3(3):223–229. doi: 10.1007/s11892-003-0068-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Legato MJ. Gender-specific physiology: how real is it? how important is it? Int J Fertil Womens Med. 1997;42(1):19–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F. Reflections on depression as a cardiac risk factor. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(suppl 1):S19–S25. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000162253.07959.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F. Recent evidence linking coronary heart disease and depression. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(12):730–737. doi: 10.1177/070674370605101202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naqvi TZ, Naqvi SS, Merz CN. Gender differences in the link between depression and cardiovascular disease. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(suppl 1):S15–S18. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000164013.55453.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(23):1801–1811. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906103402306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Legato MJ. Gender and the heart: sex-specific differences in normal anatomy and physiology. J Gend Specif Med. 2000;3(7):15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollander JE. Acute coronary syndrome in the emergency department. In: Theroux P, editor. Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease. 7. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003. pp. 152–167. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dempsey SJ, Dracup K, Moser DK. Women’s decision to seek care for symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung. 1995;24(6):444–456. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(95)80022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zerwic JJ. Symptoms of acute myocardial infarction: expectations of a community sample. Heart Lung. 1998;27(2):75–81. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(98)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McSweeney JC, Crane PB. Challenging the rules: women’s prodromal and acute symptoms of myocardial infarction. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(2):135–146. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(200004)23:2<135::aid-nur6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campeau L. Grading of angina pectoris [letter] Circulation. 1976;54(3):522–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aylard PR, Gooding JH, McKenna PJ, Snaith RP. A validation study of three anxiety and depression self-assessment scales. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31(2):261–268. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(87)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedersen SS, Denollet J, Spindler H, et al. Anxiety enhances the detrimental effect of depressive symptoms on health status following percutaneous coronary intervention. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(6):783–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dickens CM, McGowan L, Percival C, et al. Contribution of depression and anxiety to impaired health-related quality of life following first myocardial infarction. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:367–372. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.018234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canto JG, Shlipak MG, Rogers WJ, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and mortality among patients with myocardial infarction presenting without chest pain. JAMA. 2000;283(24):3223–3229. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.24.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elsaesser A, Hamm CW. Acute coronary syndrome: the risk of being female. Circulation. 2004;109(5):565–567. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116022.77781.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobs AK. Women, ischemic heart disease, revascularization, and the gender gap: what are we missing? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(3 suppl):S63–S65. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hasdai D, Porter A, Rosengren A, Behar S, Boyko V, Battler A. Effect of gender on outcomes of acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(12):1466–1469. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.French D, Maissi E, Marteau TM. The purpose of attributing cause: beliefs about the causes of myocardial infarction. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1411–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eagle KA, Goodman SG, Avezum A, Budaj A, Sullivan CM, Lopez-Sendon J GRACE Investigators. Practice variation and missed opportunities for reperfusion in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Lancet. 2002;359(9304):373–377. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07595-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorsch MF, Lawrance RA, Sapsford RJ EMMACE Study Group. Poor prognosis of patients presenting with symptomatic myocardial infarction but without chest pain. Heart. 2001;86:494–498. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.5.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]