Abstract

Slice preparations isolate functional networks, permitting single unit recording under visual control, and the use of fluorescent indicators. Circuits of interest often lie at a tilt in both the rostrocaudal and ventrodorsal axis, thus exposing circuits of interest at the cut surface of a slice would require a device for tilting a preparation along two orthogonal axes relative to the blade. Such a device, designed to be used in conjunction with a vibrating microtome, permitting the isolation of slice preparations at reproducible angles, is described here. Because the two orthogonal axes of tilt can be independently and continuously adjusted, it is possible to use this device to successively refine tilt parameters from preparation to preparation for optimal exposure of circuits of interest, facilitating the development of new slice preparations. Its use in cutting a thick medullary slab preparation, isolated from the neonate rat, which exposes respiratory networks at the cut surface is described.

2. Introduction

Over the last 35 years, in vitro slice preparations, isolated from rodents and other vertebrates, have been used extensively. Each preparation varies in its details, but the final step typically involves mounting a portion of the neuraxis on a block, and cutting it with a vibrating microtome at a standard rostrocaudal, mediolateral, or dorsoventral level, with the angle of the blade perpendicular or parallel to the midline. Historically, thin slices retaining minimal networks have been favored, since these preparations permit clear visualization of neurons at the surface using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. Recently, a new illumination method has been described, permitting DIC-like optics in arbitrarily thick preparations in which networks are visualized at the cut surface (Safronov et al., 2007).

Because circuits of interest are rarely aligned perpendicular or parallel to the midline axis, it is usually impossible to cut a slice preparation that exposes all the constituents of a network at the surface of the slice, when the slice is cut perpendicular or parallel to the midline. If landmarks other than the midline are used to align the preparation in relation to the blade, then reproducibility becomes difficult. Several recent publications specify the appropriate angles for a variety of preparations cut at a tilt relative to the midline (Matthews et al., 2004; Rocco and Brumberg, 2007) or the ventral surface (Smeal et al., 2007). While these authors present methods that will allow other researchers to reproduce their experimental preparations, the more general problem of how a to develop a slice preparation based on general neuroanatomical knowledge of where circuits of interest lie within the neuraxis remains unresolved.

The device described here was designed to facilitate the development of a tilted sagittal slab preparation isolated from neonate rat medulla, permitting optical recording of respiration-modulated neurons extending caudally from the facial nucleus (VIIn) in ventrolateral medulla (Barnes et al, 2007). The challenge that this preparation presented was to expose both parafacial respiratory group (pFRG) at the level of the VIIn, and the pre-Bötzinger Complex (preBötC), located 500 µm caudally (Ruangkittisakul et al., 2005). Both regions are rich in respiration-modulated neurons, and have been proposed as playing a critical role in respiratory rhythm generation (Janczewski and Feldman, 2006; Onimaru et al., 1988; Onimaru et al., 2006; Smith et al., 1991). Low spatial resolution optical recordings from the en bloc brainstem spinal cord preparation (Onimaru and Homma, 2003) indicated that the pFRG lay lateral to the preBötC, and provided a starting point for the parametrization of a sagittal slab preparation. Parameters that exposed both networks were arrived at iteratively (across many preparations) by adjusting ventrodorsal and rostrocaudal tilt, and mediolateral level of section so as to isolate a preparation that displayed Ca++ signals at the level of the pFRG and preBötC, and that generated a stable respiratory rhythm at physiological [K+]o.

In one form or another, the development of a novel slice or slab preparation will require a similar process of successive refinement, involving adjustments in the angle and level of section so as to optimally expose circuits of interest at the cut surface. For this process to be carried out efficiently, it is important that cutting parameters be continuously adjustable, and that from preparation to preparation, a given set of parameters be reproducible. In the device described here, the angle at which tissue can be cut is continuously adjustable. By comparing multiple preparations cut using the same parameters, we demonstrate the reproducibility that this device permits.

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Fabrication and assembly

The adjustable platform consists of 5 elements: 2 angle adjustment modules; a block to hold the chuck on which the tissue is mounted; the chuck; a simple mold in which a Sylgard™ (Dow Corning) strip is cast. All machined components are made out of Delrin.

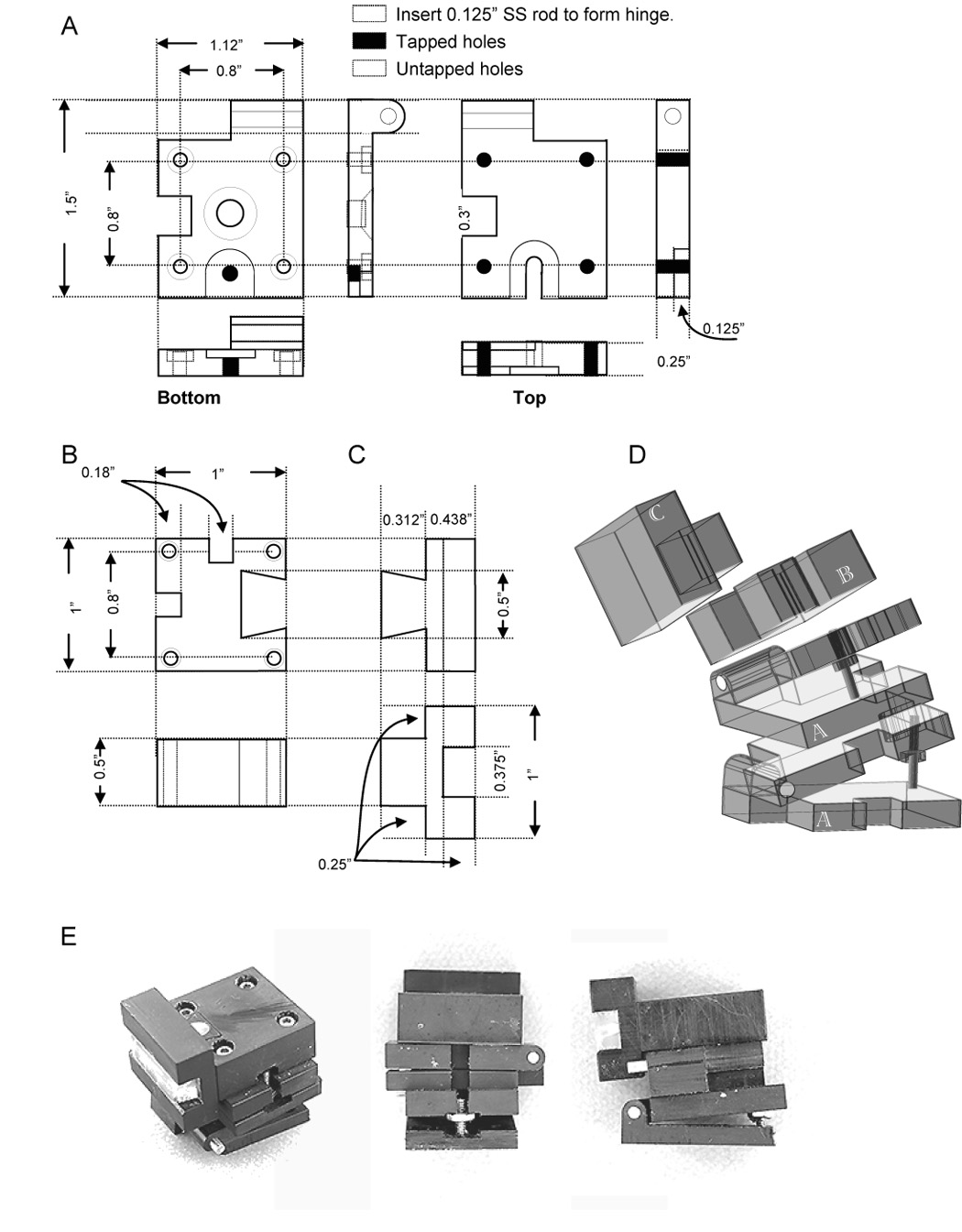

The angle adjustment modules resemble hinges (figure 1A). The lower hinge is attached via a bolt to the vibrating microtome post, which moves up and down relative to the blade. The hinges are stacked perpendicularly to each other. The angle of tilt is controlled by moving a bolt along a threaded rod (0–80 thread) attached so that it protrudes perpendicularly out of the bottom plate of each hinge. The angle swept out by the top plate of the hinge is set by the bolt’s position on the threaded rod. A second bolt can be added to lock the vertical adjustment along the rod. One full turn of the bolt results in 300 µm of travel, which corresponds to 0.5°/ turn. Four bolts through the clear holes in the bottom plate of the top hinge are fastened to the 4 tapped holes on the top plate of the bottom hinge, so that the top hinge opens at right-angles to the lower hinge (figure 1D top). The hinges are notched so that the rod extending out of the lower hinge will clear the upper hinge.

Figure 1.

Schematic and photographs of adjustable platform for cutting slice preparations at reproducible compound angles. A. Hinge module. Two of these elements are stacked orthogonally, providing tilt in each axis. The only critical dimensions are that the four tapped and untapped holes be arranged on a square, and aligned, permitting stacking of the modules. The angle swept out by each assembled hinge is set by the vertical position of the bolt that travels on the threaded rod extending out of the bottom plate of each hinge. The rod extends 0.75 inches out of the plate, permitting up to 37° to be swept out. A second bolt can be tightened against the first to clamp each hinge at the desired angle. A pocket must be cut out of each hinge to accommodate the threaded rod extending out of the hinge module beneath it. In addition, each hinge must be recessed to accommodate the bolt at the base of the threaded rod when an angle of 0° is desired. B. Block to hold the chuck. The only critical dimensions are the spacing of the holes through which the block will be bolted to the hinge below it, and the dovetail cutout, which must be snug enough to eliminate all unwanted chuck movement, but loose enough to permit easy removal. The block must be notched to permit passage of the threaded rods extending out of the hinges below it. C. Chuck. The 3/8 inch trough is filled with two strips of sylgard, slightly heavier than 3/16 inch, cast in a 3 inch × ¼ inch × 3/16+ inch mold (not shown). These strips are held in place by a tight pressure fit, as well as a dental elastomer (Reprosil) which both fills the midline seam, and makes it clearly visible, permitting easy alignment. D. Simplified isometric drawing of each component, indicating how the parts are assembled; screw holes have been left out for clarity. Letters indicate the matching schematic drawings. E. Three views of the apparatus, rotated to show all components.

A block with a dovetail cutout is attached to the upper hinge via the tapped holes (figure 1 B). The dovetail cutout is oriented towards the blade. This block is also notched to clear the threaded rods of the hinge components. The dovetail cutout is machined to provide a snug fit to the chuck on which the tissue is pinned out (figure 1 C). This chuck has a 0.375 inch groove cut through it, which holds two 0.1875 -inch wide strips of Sylgard, pressure fitted into the groove and held together by dental impression material Reprosil™. Two strips rather than one 0.375 inch strip are used, so that the midline where they meet can be used to align the tissue. A blow-apart rendering of the assembled device (figure 1 D), as well as 3 photographs of the device (figure 1 E) shows how the individual pieces are assembled.

Although the details of the design presented here are suited to the Vibratome™ (Vibratome Inc., St. Louis MO) series of vibrating microtomes, it should be readily modifiable to work with other manufacturers. Likewise, the dimensions shown in figure 1 can be modified as appropriate for the size and the desired orientation of the tissue to be cut.

Experimental procedure

In accordance with methods approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, neonate rat pups (P1–P3) were anesthetized with isoflurane. Using standard methods (Smith and Feldman, 1987b), the brainstem and spinal cord were isolated in a dissection chamber perfused with chilled artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing (in mM): 128.0 NaCl, 3.0 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1.0 MgSO4, 21.0 NaHCO3, 0.5 NaH2PO4, and 30.0 glucose, equilibrated with 95%O2-5% CO2.

The brainstem was transected at the rostral boundary of the facial nuclei, visible as bumps on the ventral surface of the brainstem. Brainstem width was carefully measured at the level of the hypoglossal rootlets using a reticle. Because the edges of the brainstem are roughly parallel at this level, the exact rostrocaudal position at which the measurement was made is not important. This measurement was used to determine the mediolateral level at which the sagittal slice was cut. The brainstem was pinned out on its flat dorsal surface, with the midline aligned to the midline of the chuck. The tilt parameters were: 2.2° rostrocaudally, and 12° ventrodorsally. After the brainstem was mounted on the chuck and immersed in aerated chilled ACSF, it was gradually raised until the Vibratome blade just touched the lateral edge of the brainstem. Using this position as the origin, the preparation was then raised so that the blade was at 0.34 of the distance from the midline to the lateral edge of the preparation, and cut at minimum forward travel speed, and maximum vibration. The preparation was then raised so that the blade was at 0.7–0.8 of the full width of the brainstem, and the blind side was cut (figure 2 B).

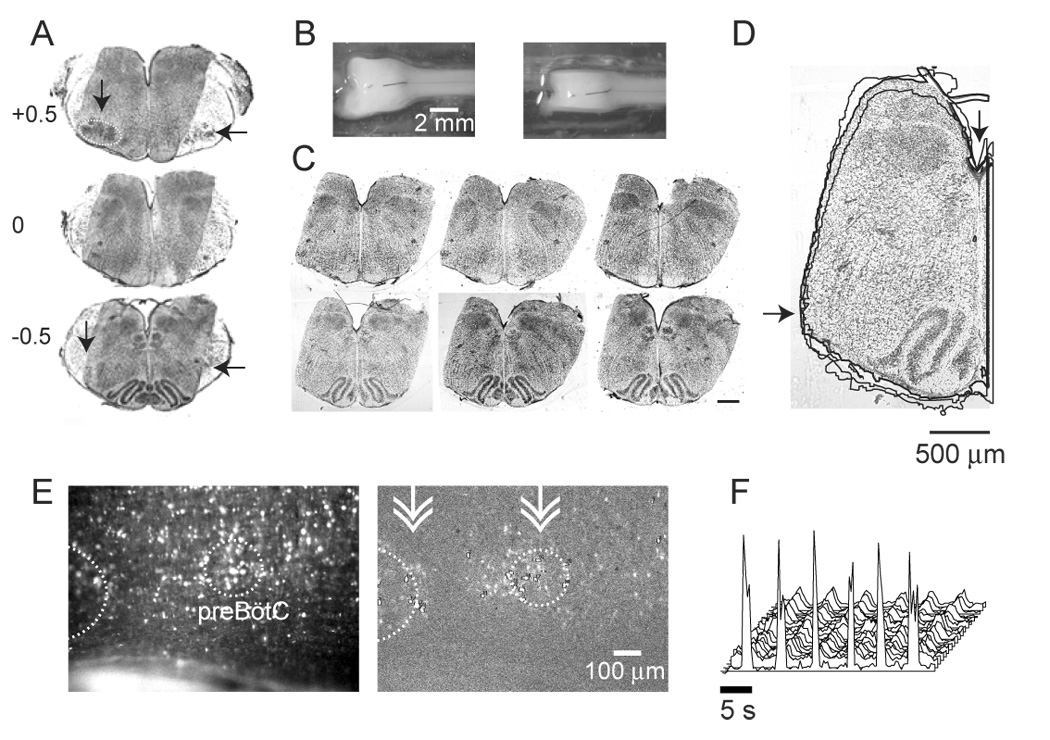

Figure 2.

View of the preparation. A. Nissl-stained transverse sections through the sagittal slab preparation at the level of the caudal pole of the facial nucleus (VIIc, 0), and 500 µm caudal (−0.5) and rostral (+0.5). Sections from the sagittal slab have been superimposed on corresponding transverse section from whole brainstem, obtained from a litter-mate. Whole brainstem sections have been reproduced at higher contrast than the sagittal sections to facilitate identification of the caudal pole of VIIn (horizontal arrows), the compact formation of the nucleus ambiguus (vertical arrow), and the VIIn (dotted circle). In this preparation, the blind side was cut at 0.75 of the brainstem’s width. B. Views of the preparation on the chuck, before (left) and after (right panel) cutting. C. Matching transverse sections through sagittal slab preparations from 3 litter-matched P2 pups, at the level of the caudal pole of VIIn (top) and the preBötC (bottom). Respiratory networks are preserved on the left-hand cut surface. The blind side was cut at 0.8 of the brainstem’s width. Scale bar represents 500 µm. D. Traced outlines of hemisections containing the preBötC, taken from sections shown in panel C. Outlines were aligned using the trough of the 4th ventricle (vertical arrow). The heavier tracing is associated with the hemisection that is shown, indicating that the trace technique used here hewed closely to the outline of the image. Variation between preparations is small near the ventral surface (horizontal arrow) but increases dorsally, likely because of differences in the ventrodorsal tilt during sectioning. E. Raw (left) and high-pass filtered (right) views of the preparation in the recording chamber. In the high-pass filtered image, Ca++ transients measured during inspiration, averaged over 3 cycles of activity are shown. Active cells appear as brighter than background in the high-pass filtered image. White dotted lines outline the VIIn, as well as the hypothesized location of the preBötC (Ruangkittisakul et al., 2006). Double arrow-heads indicate the approximate location of transverse sections shown in C. F. Population motor output (foreground) and synchronous optical signals. Both the extracellular population motor output recording and the optical signals reflect relative changes in Vm and [Ca++]i, and thus cannot be assigned units. Furthermore, because optical signals are high-pass filtered, the standard measure of changes in fluorescence (Δf/f) does not apply.

The preparation was then mounted on the narrow edge of 2 mm thick semicircular slab of sylgard 7 mm in diameter, and incubated for 2 hours in an aerated solution containing the high affinity cell-permeant Ca++ indicator fluo-4 AM (Invitrogen; 50 µg), 25 µl of the surfactant pluronic F-127, and 750 µl ACSF for a final concentration of 60 µM. Following dye loading, the preparation was transferred to a recording chamber (JG 23 W/HP, Warner Instruments, Hamden CT) perfused with aerated aCSF maintained at 27° C, mounted on an upright microscope (Axioscop 2, Zeiss Instruments). A suction electrode connected to a differential amplifier (EXT-01C/DPA 2F; NPI Electronics, Tamm, Germany) was placed on ventral root C2, and the population recording was digitized at 1 kHz (PCI-MIO-16XE-10, National Instruments, Austin TX). Fluorescence images were obtained at 2–4 frames per second using a CCD camera (Orca ER, Hamamatsu Corp, Bridgewater NJ) connected to a frame-grabber (IMAQ PCI-1422, National Instruments, Austin TX). Images were analyzed offline using custom LabView software (National Instruments, Austin TX).

3.2. Histological processing

Sagittal slab preparations were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution overnight. Preparations were placed dorsal side down in a square well, perpendicular to one of the well’s faces and covered in agar. After the agar had hardened, the agar block was removed from the well, excess agar was trimmed away from the lateral edges of the block, and the face of the agar block perpendicular to the long axis of the preparation was glued to the post of the vibratome with cyanoacrylate cement. The block was stabilized in a delrin sleeve and cut into 50 µm sections, which were mounted on subbed slides and allowed to dry for 48 hours. Sections were then stained with cresyl violet using standard procedures and coverslipped.

3.3. Microscopy and image processing

Sections were examined on an upright microscope (Axio Imager A1, Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood NJ) at 25 X magnification, and photographed (Axiocam mRm, Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood NJ). The caudal pole of the facial nucleus (VIIc) was used as the orienting landmark, because it could easily be distinguished from more rostral segments by the absence of the VIIn, and from more caudal sections by the absence of the dorsal and principal inferior olive, which appear abruptly 100 µm caudal to the VIIc. The section 500 µm caudal to the VIIc was then designated as the midpoint of the preBötC, in accordance with recently described methods (Ruangkittisakul et al., 2006), Because the normally flat dorsal surface of the brainstems tended to arch during the fixation process, small differences in dorsoventral tilt could be seen between preparations, most noticeably as differences in the aperture of the 4th ventricle. Because ventral landmarks were used to identify the caudal pole of the VIIn, ventral structures are more consistently aligned than dorsal ones.

To estimate preparation-to-preparation variability in mediolateral distance and tilt parameters, we superimposed outlines of hemisections containing the preBötC (figure 2 D), obtained from 3 litter-matched pups. To do this, all images of transverse sections were rotated so that their midlines ran vertical. A hemisection extending just past the midline was then extracted from each image. The resulting cropped hemisection was then transformed into solid black on a white ground, using the “glowing edges” and other effects in Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose CA). The resulting black-on-white image was compared to the original using the Merge Layers function. The outline of this simplified black-on-white image was obtained using the automated tracing feature in Illustrator (Adobe, San Jose CA). The resulting outlines were aligned to one another using the trough of the 4th ventricle as the anchor point.

4. Results and Discussion

The vibrating microtome attachment described here was used to isolate brainstem networks that generate stable respiratory rhythm in 3 mM [K+]o, with a period of approximately 5 s at 27° C, and to permit optical recordings from both the pFRG and PBC in the same preparation (figure 2 E, F). The tolerances for this preparation are tight: small changes in angle or mediolateral level of section produce preparations that are inactive, or without discernible Ca++ signal. Because fluo-4 loading declines with postnatal age, only P0-P3 pups have been used here, thus the adjustments in cut parameters necessary to expose similar circuits in older animals have not been characterized. The circuits exposed here are the same as those isolated previously in a highly reduced preparation using different means (Paton et al., 1994). Unlike this earlier preparation, the sagittal slab does not isolate a minimal circuit, but rather exposes circuits of interest at the cut surface, while retaining as many of the synaptic inputs to these circuits as possible, since removal of these inputs can transform neuronal activity patterns, complicating the process of establishing mappings between in vivo and in vitro data (Steriade, 2001).

The resulting tilted sagittal slab retained both the preBötC and the facial nucleus on the recording side, while on the blind side most of the ventrolateral quadrant of the brainstem is missing at the level of the preBötC, and the facial nucleus is absent (figure 2A, broken white line). Thus, both the pFRG and preBötC are retained on the recording surface, but these structures are likely compromised on the blind side.

An essential requirement of the device described here is that from preparation to preparation, consistent compound angles are cut. To test this consistency, transverse sections cut from 3 P2 rats are shown at the level of the VIIc (figure 2 C, top), and 500 µm caudally, at the level of the preBötC (Ruangkittisakul et al., 2006) (figure 2 C, bottom). As can be seen from the aligned outlines of hemisection containing the preBötC (figure 2 D), preparation-to-preparation variability was small in the ventral quadrant. Variability in the dorsal quadrant is likely due to differences in the ventrodorsal tilt at which transverse sections were cut, as can be seen clearly in the preparation-to-preparation variability in 4th ventricle aperture.

The device described here permits the development of slice preparations that lie on planes at a compound angle (i.e., tilted along two orthogonal axes) to the midline. The development of the tilted sagittal slab preparation, exposing the pFRG and the preBötC at its surface is proof-of-concept: identification of optimal cutting parameters was arrived at iteratively over many experiments, in which three variables (rostrocaudal tilt, ventrodorsal tilt, and mediolateral distance) were systematically varied. More importantly, at any particular set of parameters, results were reproducible (figure 2 B). Although it is beyond the scope of this report to validate this device by developing a novel tilted slice exposing a distinct functional network, two preconditions necessary for such an undertaking – independent continuous adjustment of cutting variables, and reproducibility at a given set of variables – have been met.

Because tilt angles can be “locked in”, using a second bolt on each threaded rod, this device can also be used for the cutting of tilted slices once tilt parameters are set. Currently, tilted slices are cut by gluing brain tissue to a block of agar cut at the desired angle. This technique cannot be easily extended to cutting tissue at compound angles, since accurate orthogonal alignment of 2 agar wedges would be difficult to reproduce. In addition, this device may be useful to those who wish to cut transverse slices at high tolerances, in that small errors in aligning the preparation in relation to the blade can be corrected for by adjusting the tilt from section to section until the preparation is exactly perpendicular to the blade. These small adjustments in tilt would obviate the need for repining or regluing the en bloc preparation, but would best be carried out well rostral to the region to be isolated in the transverse slice, since each time angles are adjusted, the subsequent section that is cut will not have parallel faces.

A limitation of this device is that if tilt angles are adjusted as a function of structures seen in the exposed tissue, then the subsequent section or sections will not have parallel faces. Larger changes in angle would very likely render a given preparation unusable. Assuming that the experimenter had a standardized way of mounting the tissue on the chuck, the modified tilt parameters could then be tested on the subsequent preparation. Thus, although this device would allow small corrective adjustments in tilt angles while cutting a slice, larger adjustments would require starting a new preparation.

The original in vitro preparation used to study respiratory rhythm generation was the en bloc brainstem spinal cord preparation (Smith and Feldman, 1987a; Suzue, 1984). This preparation continues to be used, but because respiratory networks are hundreds of microns from the surface of the preparation, and the intervening tissue presents a diffusion barrier to the glucose and oxygen in the perfusate, the circuits of interest are likely hypoxic and acidotic; in addition, constituent neurons can only be probed using blind techniques. The transverse slice preparation (Smith et al., 1991), which is isolated from the en bloc preparation, is the preparation of choice for studying the cellular and synaptic properties of rhythmogenic interneurons contained in the preBötC, recently identified as a 200 µm thick network of neurons located in the ventrolateral quadrant of a transverse section through the medulla (Ruangkittisakul et al., 2006). The compact organization of the preBötC is consistent with rhombomeric specification of brainstem circuits (Borday et al., 2004), and suggests that the functional role of respiratory neurons is highly variable along the rostrocaudal (long) axis of the respiratory column. In contrast, no evidence has been presented suggesting similar variability along the mediolateral axis within the respiratory column, at any given rostrocaudal level. Because transverse slice preparations that isolate the preBötC are typically at least 500 µm thick, these preparations are more likely to contain the preBötC, than to expose it at either surface of the slice. As a consequence, essential rhythmogenic networks contained in the standard transverse slice are relatively inaccessible using techniques commonly applied to slice preparations, such as DIC microscopy, and optical recording, which are limited to cell layers close to the slice’s surface. By contrast, because the tilted sagittal slab is cut parallel to the respiratory column, a cross-section of the preBötC is at the surface of the preparation, offering access to rhythmogenic interneurons, which are easily identified using Ca++ imaging techniques (figure 2 E). An important disadvantage of the sagittal slab relative to the transverse slice is that neurons at the surface likely constitute only a fraction of respiratory networks contributing to the observed motor output, thus the detailed reverse engineering of functional networks that is possible in highly reduced preparations using pharmacological techniques or cell ablation/excision are not applicable in the tilted sagittal slab. These differences highlight the importance of tools that facilitate the development of slice preparations that expose networks along different planes, as each plane of section can be used to address distinct questions. Given the recent developments that obviate the need for thin slices to be able to impale neurons under visual control (Safronov et al., 2007), it is possible to consider using this device to develop a tilted hippocampal sagittal slab preparation, exposing this structure along its main axis, rather than in cross-section.

5. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL068007.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

5. References

- Barnes BJ, Tuong CM, Mellen NM. Functional imaging reveals respiratory network activity during hypoxic and opioid challenge in the neonate rat tilted sagittal slab preparation. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:2283–92. doi: 10.1152/jn.01056.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borday C, Wrobel L, Fortin G, Champagnat J, Thaeron-Antono C, Thoby-Brisson M. Developmental gene control of brainstem function: views from the embryo. Progress in biophysics and molecular biology. 2004;84:89–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janczewski WA, Feldman JL. Distinct rhythm generators for inspiration and expiration in the juvenile rat. J Physiol. 2006;570:407–420. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.098848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews RT, Coker O, Winder DG. A novel mouse brain slice preparation of the hippocampo-accumbens pathway. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;137:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Arata A, Homma I. Primary respiratory rhythm generator in the medulla of brainstem-spinal cord preparation from newborn rat. Brain research. 1988;445:314–324. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Homma I. A novel functional neuron group for respiratory rhythm generation in the ventral medulla. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1478–1486. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01478.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Kumagawa Y, Homma I. Respiration-related rhythmic activity in the rostral medulla of newborn rats. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:55–61. doi: 10.1152/jn.01175.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JF, Ramirez JM, Richter DW. Functionally intact in vitro preparation generating respiratory activity in neonatal and mature mammals. Pflugers Arch. 1994;428:250–260. doi: 10.1007/BF00724504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocco MM, Brumberg JC. The sensorimotor slice. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;162:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruangkittisakul A, Schwarzacher SW, Ma Y, Poon BY, Secchia L, Funk GD, Ballanyi K. Program Washington, DC. 2005. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; 2005. Minimum pre-Botzinger complex extension for rhythm generation at physiological [K+] of brainstem slices from newborn rats. [Google Scholar]

- Ruangkittisakul A, Schwarzacher SW, Secchia L, Poon BY, Ma Y, Funk GD, Ballanyi K. High sensitivity to neuromodulator-activated signaling pathways at physiological [K+] of confocally imaged respiratory center neurons in on-line-calibrated newborn rat brainstem slices. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11870–11880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3357-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safronov BV, Pinto V, Derkach VA. High-resolution single-cell imaging for functional studies in the whole brain and spinal cord and thick tissue blocks using light-emitting diode illumination. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;164:292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeal RM, Gaspar RC, Keefe KA, Wilcox KS. A rat brain slice preparation for characterizing both thalamostriatal and corticostriatal afferents. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;159:224–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Ellenberger H, Ballanyi K, Richter D, Feldman J. Pre-Bötzinger complex: a brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science. 1991;254:726–729. doi: 10.1126/science.1683005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Feldman J. In vitro brainstem-spinal cord preparations for study of motor systems for mammalian respiration and locomotion. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1987a;21:321–333. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(87)90126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Feldman JL. In vitro brainstem-spinal cord preparations for study of motor systems for mammalian respiration and locomotion. J Neurosci Methods. 1987b;21:321–333. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(87)90126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M. Impact of network activities on neuronal properties in corticothalamic systems. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1–39. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzue T. Respiratory rhythm generation in the in vitro brain stem-spinal cord preparation of the neonatal rat. Journal of Physiology (London) 1984;354:173–183. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]