Abstract

Objective

Negative life events have been implicated in the development of alcohol dependence. This paper tests whether cumulative exposure to such stressors significantly predicts risk of DSM-IV alcohol dependence disorder in young adults. We also provide descriptive data that characterizes the patterns of cumulative exposure to such events and rates of alcohol dependence across gender, race/ethnic, and socioeconomic groups.

Method

Members of a representative urban community sample of 1786 young adults in South Florida were interviewed retrospectively using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, and a lifetime checklist of 41 major adverse life events. The conditional risk of first onset of alcohol dependence disorder was estimated in relationship to a measure of lifetime cumulative adversity using discrete-time event history analysis.

Results

Event history analysis suggested that lifetime stress exposure exhibits a pattern of association with alcohol dependence that is consistent with a cumulative impact interpretation. Both recent events and events more distant in time were significantly and independently associated with such risk. Although these results contribute toward an understanding of variations in alcohol dependence across individuals, they do not assist in the understanding of observed ethnic group differences in such dependence.

1. Introduction

According to recent epidemiological studies (Grant and Dawson, 1999; Kessler et al., 1994), about 14 percent of U.S. adults are afflicted by alcohol dependence disorder as defined by the profession of psychiatry (American Psychiatric Association 1987, 1994) at some time in their lives. The greatest rate of alcohol dependence occurs in the youngest adults (Grant and Dawson, 1999). Negative societal consequences of alcohol dependence are many: drinking problems in adolescence and early adulthood are implicated in the premature termination of education (Kessler et al., 1995), and are a major cause of injuries and illness. Alcoholism can adversely affect social roles and relationships, resulting in such problems as job instability, and marital failure. The economic cost of alcohol abuse and dependence to US society for a single year has been estimated at $148 billion (Harwood et al., 1998).

Several studies have considered stress as a risk factor for adolescent and young adult problem drinking (Brown, 1987; Costa et al., 1999; Johnson and Pandina, 1993; Perkins, 1999; Windle and Windle, 1996). While the link between stress and problem drinking seems well established, it remains uncertain whether the relationship generalizes to alcohol dependence disorder and whether risk associated with stress exposure is additive over time. As observed over a decade ago by the NIAAA Director, although stress is widely believed to be a factor in alcohol dependence, science has been more informative about the relationship between drinking and stress than about that between stress and addiction (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 1996). In this study, we test whether the amount of cumulative lifetime exposure to social stressors predicts level of risk for the onset of alcohol dependence disorder in a representative community sample of young adults.

2. Background

There is a substantial tradition of research evaluating the linkage between adult mental health and substance use problems and specific forms of major and potentially traumatic experiences. Principal among these are parental deaths and parental divorces (Brown and Harris, 1978; McLeod, 1991), sexual abuse (Browne and Finkelhor, 1986; Green, 1993); and physical violence and abuse (Bryer et al., 1987; Holmes and Robins, 1988). Indeed, Widom and colleagues (1999) identified more than 20 studies demonstrating relationships between childhood sexual or physical victimization and increased risk of substance abuse. However, studies that assessed the significance for alcohol use problems of multiple exposures over time have been rare.

Some evidence has recently appeared on the role of multiple stressors in the development of drinking problems' among young people. Johnson and Pandina (2000) grouped subjects according to their expression, over a three-year period, of alcohol use problems reflecting DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Their measures of prior and concurrent stress, weighted in terms of how much a person was bothered by life events, were consistently highest in the group tending toward alcohol dependence compared with subjects who indicated abuse only, and with those expressing no alcohol use problems.

Sher and colleagues (1997) studied the potential role of childhood adversities before age 18 as a mediator of the relationship between parental alcoholism and DSM-III alcohol abuse and dependence disorder combined, in a college student sample. They found that while effects of alcoholic family history were partially explained by childhood adversities, the adversities were largely independently associated with drinking disorder. In a study of a clinically based adolescent sample, Clark et al. (1997) distinguished alcohol dependent adolescents from those who met criteria for abuse alone, and those with no alcohol disorder. They found a significant association between disorder status and lifetime exposure to traumatic stress, as well as a relationship with a separate extensive index of recent (past year) life events. Both types of stress were least prevalent in the control group, and tended to be greatest in the dependence group. With respect to both of these studies, however, it is unclear whether the samples were representative of young adults in the general population who had experienced alcohol dependence and whether all assessed stressors preceded the first onset of disorder.

Stress is thought to lead to initiation of alcohol use at younger ages (Biafora et al., 1994; Scheier et al., 1999), which could increase the likelihood of dependence. However, the majority of youthful drinkers do not go on to become addicted to alcohol. It is not uncommon for these studies to employ measures of stress exposure that are limited both in scope and in coverage over time (though for an exception see Clark et al. [1997]).

We conceptualize stress exposure as the occurrence of normatively undesirable life events, independent of the individual's reaction to them, and focus on major events that may have the potential for long term consequences. Such exposure may increase risk for adverse health and behavioral outcomes by means associated with distinctive hypothesized patterns (Kuh et al., 2003). Lifetime exposure to stressors may exert its influence through a “chain of risk,” wherein early exposure increases risk for later exposures, ultimately the more important predictor. From this perspective, an intervention that interrupts the chain would block the associated risk. Conversely, risk may increase additively as exposures accumulate over one's lifetime. In a case in which distal and proximal stress exposures are separately measured, an observation that the association between dependence and distal stress is entirely or largely mediated by the measure of proximal stress would provide support for the chain of risk hypothesis. In contrast, a finding that both distal and proximal stress exposures independently predict dependence onset would be consistent with the cumulation of risk hypothesis.

This paper extends research on the role of stress in alcohol dependence by modeling the relationship between lifetime accumulation of stress and the risk for first onset of alcohol dependence disorder, using a survival analysis framework. We also consider whether the rates of dependence and exposure to stress vary by gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic level, and whether any observed linkage between cumulative stress and alcohol dependence is consistent across these social status dimensions. Our outcome measure is first onset of DSM-IV alcohol dependence; cumulative stress is measured as a simple count from a comprehensive checklist of major and potentially traumatic events that excludes items that occurred at or after the age of the first onset of alcohol dependence. While most prior research has measured stress accumulated over a relatively brief period, we test the hypothesis that the lifetime accumulation of major adverse experiences contributes to the variation in risk for alcohol dependence. Our study does not, however, address the specific physiological or psychological mechanisms that would link stress exposure to the outcome. Some plausible avenues have been suggested, including maladaptive alcohol use in response to stress for tension reduction, social learning, changes in neurotransmitters, and changes in the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (Brady and Sonne, 1999; Cooper et al., 1990).

3. Data and methods

This paper is based on a study of the prevalence and social distributions of psychiatric and substance use disorders and of factors that increase and decrease risk for such disorders among a representative cohort of 1803 young adults. Most (93%) were between 19 and 21 years of age when interviewed between 1997 and 2000. The study population is ethnically diverse, allowing consideration of ethnic variations in both stress exposure and the consequences of exposure. Specifically, the sample was drawn such that approximately 25% are of Cuban origin, 25% other Caribbean basin Hispanic, 25% African-American and 25% non-Hispanic White.

3.1. Sample

The present study was built on a previous three-wave investigation based in Miami-Dade public schools (Vega and Gil, 1998). All 48 of the county's public middle schools and all 25 public high schools and the alternative schools participated. The previous study targeted all 9,763 boys entering the school district's grade 6 and 7 classes in 1990, plus a representative subsample of 669 girls. The present study drew its participants from the earlier project and employed a far more comprehensive inventory of stress, psychosocial resources, and psychiatric and substance use outcome measures.

Within limits of ethnicity criteria, all females who participated in the earlier investigation (n=410) and a random sample of 1,273 males were ultimately selected. Because a relatively small number of females were in the previous study, a supplementary sample was randomly drawn from the 1990 sixth and seventh grade classes. Overall, 70.1 percent of those sampled were successfully recruited to the study. By far the greatest loss occurred among the new sample of females who were not involved in the earlier study. From those in the original sample 76.4 percent was retained, despite the fact that many had left home for college or other reasons. The final study sample included 1803 participants, of whom 17 are excluded from the present analysis because they did not identify as a member of one of the four qualifying race/ethnic groups.

All analyses to be reported are based on data obtained when participants were young adults and not data from the previous study. Those interviewed for the present study were compared with the total sample drawn from the original study population on a wide array of early adolescent behaviors and family characteristics (analyses not shown) including family structure, parental education and income, parental substance use, and reports by respondents of substance use within the wave 1 and wave 3 questionnaires. No statistically significant differences were observed. Comparisons were also made with respect to school drop out. Among those interviewed, 20.5 percent reported that they had dropped out of high school. This corresponds closely with rates reported by the school board on the same student cohort of 21.1 percent for males and 15.2 percent for females (Miami-Dade Public Schools, 2000). These comparisons and the 76.4 percent follow-up success suggest that our sample is reasonably representative of the population from which it was drawn. In contrast, comparisons on an array of characteristics revealed a significant bias with respect to parental socioeconomic status associated with the 41.8 percent loss rate among the supplementary sample of new girls. To correct this bias, female participants have been weighted in all analyses to achieve an SES distribution that approximates that of the male participants. Because we sampled so as to achieve roughly equal numbers of White non-Hispanics, Cubans, other Hispanics and African Americans, the data have also been weighted to reflect population ethnicity and gender distributions.

3.2 Assessment protocol

The use of computer assisted personal interviews assured appropriate routing through the questionnaire and greatly facilitated the reliable administration of the interview. Our standard practice was face-to-face interviewing in the respondent's home or in our research offices as the respondent chose. However, telephone interviews utilizing previously mailed response booklets were employed for those who were away at university or who had moved elsewhere in the contiguous United States. Approximately 30 percent of the interviews were conducted by telephone. Although most evidence suggests that in-person and telephone interviews yield comparable data (Aktan et al., 1997; Midanik et al., 1999; Rohde et al., 1997), contrary findings have also been reported (Aquilino, 1994). The effect of interviewing mode within the present study was assessed using logistic regression. Presence versus absence of a substance use disorder was regressed on interviewing mode with and without controls on gender and ethnicity. We found no evidence of any interviewing mode effect within or across status categories. All interviews were conducted in English; we employed a cadre of college-educated interviewers from diverse ethnic groups, who were matched whenever possible with participants to optimize interviewing conditions. Given the importance of establishing the temporal ordering of life stressors and the onset of alcohol dependence, we employed a Life History Calendar (LHC) based on that developed by Freedman et al. (1988) as an aid to enhance recall. This calendar traces three categories for which respondents described divisions in their lives in terms of where they lived, landmark events such as birth of a sibling, getting a driver's license or leaving school, and the teachers or best friends they had during various years. The descriptions, which build upon each other, provide an effective temporal context within which reports of major stressors and onsets of disorders are set during the interview.

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants and the procedures for obtaining such consent and for protecting the rights and welfare of participants were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of The University Miami, Florida International University and Florida State University.

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Diagnostic assessment

Data on the lifetime occurrence of psychiatric and substance use disorders were obtained through structured interviews that allowed estimation of DSM-IV diagnoses. Our basic instrument was the Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) that was employed in the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) (Kessler et al., 1994). The CIDI is a fully structured interview, based substantially on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (Robins et al., 1981); it is designed to be administered by non-clinicians trained in its use (Robins et al., 1988; World Health Organization, 1990). Using the Michigan CIDI, as updated by NCS researchers to cover DSM-IV criteria, we assessed major depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, alcohol abuse and dependence, drug abuse and dependence, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and antisocial personality disorder. These latter two modules had been borrowed from the DIS (Robins et al., 1981) for the NCS.

Along with the Michigan CIDI, our assessment instrument included a reliable module (Horton et al., 1998) taken from the revised DIS (Robins et al., 1995) to assess attention deficit (AD) and hyperactivity disorder (HD), and included items to allow assessment of childhood conduct disorder. Although we employed the same PTSD module used in both the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study (Robins and Regier, 1991) and the NCS, two significant innovations were adopted. Consistent with prior research, PTSD questions were asked in relation to an event nominated by respondents as the worst. However, when a diagnostic criterion was not met, participants were asked to study a list of the major PTSD symptoms and questioned about whether they had ever experienced any of them in relation to any other event. If the answer was “yes”, the event was specified and the PTSD module repeated. This efficient procedure effectively minimizes the risk of false negatives and does not require the assumption that PTSD will only occur in relation to the two or three events regarded by respondents as the worst. The age of first occurrence of each qualifying diagnosis is set within time using the LHC to achieve maximum accuracy.

3.3.2. Cumulative stress

Our measure of stress exposure is a count of major events that differ from the usual checklist items primarily in their severity and in the presumed duration of their consequences. Consideration of negative life events is usually limited to a one-year time frame, largely because of evidence that their effects tend to be limited to less than a year (Brown and Harris, 1978; Murphy and Brown, 1980). Severe events such as death of a child and serious accidents are often included in widely used life event checklists. However, the rarity of such events within the 12 months typically covered has likely masked their potential significance (Turner and Lloyd, 1995).

The 41-item event checklist covered a broad range of adverse lifetime experiences, and notes the respondent's age at the time of occurrence. These included social adversities that are not typically violent in nature such as parental divorce and failing a grade in school. Some were events that imply force or coercion. These include rape, physical and emotional abuse, and being injured with a weapon. Also included were items about being present in violent situations but not directly involved, such as seeing someone killed and witnessing serious physical or emotional abuse. There are questions about learning bad news such as of a friend's suicide or rape. Finally, we asked about deaths of relatives and close friends. A complete list of these events and their lifetime prevalence for the total sample has been previously published (Turner and Lloyd, 2003). Here we focus on the relative importance of distal and proximal stressor experiences over the lifetime as cumulative predictors of alcohol dependence. Cumulative stress is estimated by counting the number of different events that were experienced by a given point in time. Multiple occurrences of the same event are not added to the count.

3.3.3. Sociodemographic measures

Ethnicity is measured by the respondents' own identification. Socioeconomic status is estimated in terms of parental education, income and occupational prestige level (Hollingshead, 1957). These data were obtained from parent interviews and supplemented where necessary by information provided by the young adult participants. Scores on these three status dimensions were combined into a single measure of SES. The component measures were standardized, summed and divided by the number of dimensions on which participants provided information.

3.4 Multivariate analysis approach

We employ a discrete-time event history model (Allison, 1984; Singer and Willett, 1993). This approach treats each period in a person's life up to the occurrence of the outcome event as a separate observation. In the results reported below, data for the first five years are collapsed into a single period. The remaining information is grouped into 18 one-year intervals representing ages 6 to 23. Survival time to the onset of alcohol dependence among the 159 respondents who met the criteria for a lifetime diagnosis, and the entire time at risk among 1627 right-censored subjects, is thus divided into 28242 person-periods. The effect of time, fitted as a polynomial (quadratic) function (Singer and Willett, 2003), is controlled in the analysis. This is necessary because, otherwise, the association between stress and disorder could be spurious because both cumulative exposure to adversities and the risk for alcohol dependence increase with time. The measures of adverse events are time-varying covariates, while the sociodemographic variables are time-invariant. Results are reported as the model is estimated (additive equations), because the coefficients as estimated are readily interpreted in terms of our hypothesis of additive effects that are cumulative over time. The proportional hazards assumption was checked by testing for interaction between substantive predictors and time, and none was found. A series of five hierarchically organized equations is estimated, with control measures added.

4. Results

The distributions of lifetime occurrence of alcohol dependence and of cumulative lifetime adversity across gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic level are shown in Table 1. Also shown are the distributions of cumulative “pre-onset” adversity scores. These reflect the count of events that occurred up to the year prior to the age of dependence onset among those who had qualified for the disorder, and those occurring up to age 17 among the never-dependent. This age is the mean of cutoff ages used in the dependent group. Significant difference in the rate of alcohol dependence disorder is found only with ethnicity; it is dramatically greater among non-Hispanic Whites compared with the other three groups. The two Hispanic groups exhibit comparable rates (7.9 percent for Cubans and 9.8 percent for non-Cuban Hispanics); the African American rate of dependence is only 3.8 percent. The alcohol dependence prevalence rates are nearly identical for males and females. The socioeconomic distribution suggests a weak positive association, but this pattern is not statistically significant. Significant differences in the total count of adversities are observed across categories of all three social status variables, as well as alcohol dependence status. The ethnic group with the lowest rate of alcohol dependence registers the greatest total adversity score. It thus appears that variation in lifetime exposure to adversities is not likely to explain ethnic group differences in rates of alcohol dependence. The corresponding distributions of “pre-onset” stress scores exhibits a highly similar pattern. Thus, we may conclude that the observed differences in levels of lifetime cumulative stress are not likely to be a consequence, in young adulthood, of differential rates of alcohol dependence.

TABLE 1. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV alcohol dependence and mean exposure to adversities (s.d.) among community-dwelling young adults.

| Sample % | Lifetime Alcohol Dependence (%) | Mean Lifetime Adversity Count | Mean Pre-Onset Adversity Count | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 50.3 | 9.0 | 8.60 (4.77) | 8.52 (4.73) |

| Female | 49.7 | 8.8 | 7.92 (4.95) | 7.81 (4.90) |

| p | .855 | <.01 | <.01 | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 19.8 | 15.6 | 7.54 (4.81) | 7.47 (4.78) |

| Cuban | 26.3 | 7.9 | 7.30 (4.62) | 7.24 (4.62) |

| Non-Cuban Hispanic | 27.3 | 9.8 | 7.80 (4.78) | 7.72 (4.77) |

| African American | 26.6 | 3.8 | 10.22 (4.69) | 10.04 (4.61) |

| p | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Socioeconomic level | ||||

| lowest quartile | 25.0 | 7.4 | 8.75 (4.94) | 8.61 (4.88) |

| second quartile | 25.4 | 8.0 | 8.80 (5.24) | 8.68 (5.21) |

| third quartile | 24.7 | 8.7 | 8.26 (4.71) | 8.19 (4.67) |

| highest quartile | 24.9 | 11.3 | 7.16 (4.34) | 7.11 (4.31) |

| p | .181 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Ever Alcohol Dependent | ||||

| no | 91.1 | -- | 8.05 (4.78) | 7.97 (4.75) |

| yes | 8.9 | -- | 10.49 (5.24) | 10.22 (5.06) |

| p | -- | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Total | 100.0 | 8.9 | 8.25 (4.87) | 8.16 (4.82) |

Note: N=1786; data reflect the application of post-stratification weights to match the sample distribution to the population. Chi-square tests and analysis of variance were used to test group rate and mean differences. “Pre-onset” adversities among those who have not had onset of alcohol dependence are counted up to and including age 17 (the mean onset age is 17.96 years), while the corresponding count among ever-dependent cases includes all years up to and including the age prior to reported age of first onset.

Lifetime exposure rates for specific adversities across dependence status varied from exceedingly rare to almost commonplace in this diverse young adult sample. We found the lowest exposure rate to be 0.3 percent for the death of one's own child, while the highest was 47 percent both for having witnessed a serious accident or disaster and for the divorce of one's parents. The median number of different adversities ever experienced by an individual is seven. Only eight respondents reported no exposure to any stressor in our 41-item inventory.

Rates of the pre-onset occurrence of the individual stressors in our inventory are presented in Table 2, distinguishing the ever-dependent and never-dependent. Also shown are odds ratios describing the zero-order association of each stressor with subsequent alcohol dependence disorder. Of the 41 stress checklist items, only 12 are significantly associated (p<.05) with eventual alcohol dependence when considered one at a time. Just two items exhibit odds ratios above 2.0. However, all but six are at least marginally more prevalent among the ever-dependent, which suggests that variation in a cumulative measure may be more reliably associated with dependence onset than any single reported stressor.

TABLE 2. Prevalence of individual prior lifetime adversities (%) by alcohol dependence status, and bivariate associations (O.R.).

| Percent Exposed Prior to Onset | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event | Never Dependent | Ever Dependent | Odds Ratio |

| Did you ever fail a grade in school? | 22.7 | 20.8 | 0.89 |

| Did your father or mother not have a job for a long time when they wanted to be working? | 17.6 | 16.4 | 0.92 |

| Were you ever sent away from home or kicked out of the house because you did something wrong? | 9.9 | 11.9 | 1.24 |

| Were you ever abandoned by one or both of your parents? | 12.5 | 12.6 | 1.01 |

| As a child, did you ever live in an orphanage, a foster home, a group home, or were a ward of the state? | 2.0 | 1.9 | 0.93 |

| Were you ever forced to live apart from one or both of your parents? | 18.2 | 23.9 | 1.41 |

| Did your parents ever divorce or separate? | 44.4 | 48.4 | 1.17 |

| Have you ever had a child who died at or near birth, or one that was taken away from you? | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.61 |

| Have you ever discovered your spouse/boyfriend/girlfriend was unfaithful? | 25.6 | 30.8 | 1.29 |

| Did you ever lose your home because of a natural disaster? | 13.8 | 21.5 | 1.71** |

| Have you ever had a serious accident, injury or illness that was life threatening or caused long-term disability? | 8.9 | 13.2 | 1.55 |

| Did you ever have sexual intercourse when you didn't want to because someone forced you or threatened to harm you if you didn't? | 5.7 | 7.5 | 1.34 |

| Were you ever touched or made to touch someone else in a sexual way because they forced you in some way, or threatened to harm you if you didn't? | 9.4 | 11.3 | 1.23 |

| Were you regularly physically abused by one of your parents, step parents, grandparents, or guardians? | 3.5 | 6.3 | 1.84 |

| Were you regularly emotionally abused by one of your caretakers? | 8.4 | 14.6 | 1.85* |

| Were you ever physically abused or injured by a spouse/boyfriend/girlfriend? | 5.0 | 8.2 | 1.71 |

| Were you ever physically abused or injured by someone else you knew? | 6.6 | 9.4 | 1.47 |

| Have you ever been shot at with a gun or threatened with another weapon but not injured? | 25.0 | 34.6 | 1.59** |

| Have you ever been shot with a gun or badly injured with another weapon? | 3.6 | 8.2 | 2.36** |

| Have you ever been chased but not caught when you thought you could really get hurt? | 18.6 | 29.6 | 1.84** |

| Have you ever been physically assaulted or mugged? | 15.7 | 20.1 | 1.36 |

| Have you ever been in a car crash in which someone was killed or badly injured? | 5.8 | 9.4 | 1.69 |

| Have you ever witnessed a serious accident or disaster where someone else was hurt very badly or killed? | 34.1 | 44.0 | 1.52* |

| Did you witness your mother or another close female relative being regularly physically or emotionally abused? | 19.5 | 22.0 | 1.17 |

| Have you seen someone chased but not caught or threatened with serious harm? | 29.3 | 35.8 | 1.35 |

| Have you seen someone else get shot at or attacked with another weapon? | 26.7 | 35.8 | 1.54* |

| Have you ever seen someone seriously injured by a gunshot or some other weapon? | 22.1 | 24.5 | 1.14 |

| Have you ever actually seen someone get killed by being shot, stabbed, or beaten? | 9.1 | 11.3 | 1.28 |

| Have you ever been told that someone you knew had been shot, but not killed? | 26.9 | 34.0 | 1.40 |

| Have you ever been told that someone you knew had been killed with a gun or other weapon? | 25.7 | 29.7 | 1.22 |

| Has anyone else you knew died suddenly or been seriously hurt? | 18.7 | 25.8 | 1.51* |

| Have you ever been told that someone you knew killed him- or herself? | 14.4 | 22.6 | 1.74** |

| Have you ever been told that someone you knew had been raped? | 19.5 | 36.5 | 2.37*** |

| Has anyone close to you ever died? | |||

| Mother/Stepmother | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.34 |

| Father/Stepfather | 5.4 | 6.3 | 1.17 |

| Brother or Sister | 2.3 | 1.3 | 0.53 |

| Spouse/Boyfriend/Girlfriend | 0.4 | 0.9 | -- |

| A Child of Respondent | 0.1 | 0.0 | -- |

| Grandparent | 33.2 | 41.5 | 1.43* |

| Another Loved One | 19.8 | 19.5 | 0.98 |

| A Very Close Friend | 10.2 | 16.4 | 1.72* |

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

“Prior” events counted up among the never-dependent to age the year prior to average onset age.

We tested the relationship between cumulative measures of exposure to adversities and the risk for alcohol dependence using discrete time event history analysis. These multivariate results are presented in Table 3. Our models distinguish distal and proximal occurrences of adverse events, which are each counted in temporal relation to an index period, to test the hypothesis that the effects of stress are additive over time. The index period is any given year for which the conditional log-odds of onset for an individual may be estimated. The measure of distal adversities is a count of events reported as occurring at any time earlier than the year before the index period. Proximal adversities are counts of events that occurred during the year before the index period. No events that occurred in the same year as the onset of dependence or subsequently are counted. The coefficients for distal and proximal adversities reflect their independent linear additive association with the conditional log-odds of alcohol dependence, with sociodemographic factors controlled.

TABLE 3. Distal and proximal adversities as predictors of alcohol dependence onset (N=159) in 28242 person-years among 1786 community-dwelling young adults.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | b | b | b | b | |

| Socioeconomic level | .069 | .117 | .121 | .150 | .149 |

| Female | −.068 | −.043 | .002 | .063 | .063 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.517*** | 1.660*** | 1.679*** | 1.604*** | 1.612*** |

| Cuban | .771** | .952** | .994*** | .934** | .938** |

| Non-Cuban Hispanic | 1.013*** | 1.166*** | 1.204*** | 1.102*** | 1.106*** |

| Distal Adversities | .098*** | .091*** | .046* | .047* | |

| Proximal Adversities | .207*** | .182*** | .182*** | ||

| Prior Psychiatric Disorder | .475* | .479* | |||

| Childhood AD/HD | .392 | .399 | |||

| Childhood Conduct Disorder | .722*** | .725*** | |||

| Prior Drug Dependence | −.652 | ||||

| Intercept | −33.694*** | −33.323*** | −31.195*** | −31.967*** | −31.821*** |

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

Results shown are from discrete-time event history analysis. Time of first onset is estimated using binary logistic regression in person-period data. Survival time among the respondents who met lifetime diagnosis, and the entire time at risk among right-censored subjects, is divided into one-year intervals. “Distal adversities” are counts of events reported as occurring during period earlier than the year before the index period. “Proximal adversities” are counts of events in the year before the index period. The effect of time is modeled as a quadratic function (not shown). The reference category for ethnicity is African American. Outcome is first onset of DSM-IV alcohol dependence disorder. Prior psychiatric disorder includes major depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety, panic, social phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Post-stratification weights are applied to align the data to population values.

Model 1 in Table 3 reflects the significant pattern of risk for alcohol dependence across ethnic groups revealed in Table 1. We found no significant association between dependence and either gender or socioeconomic background. The measure of distal adverse events is added in Model 2. The regression coefficient b=.098 indicates a significant positive association between level of cumulative exposure and risk for alcohol dependence more than two years later.

Adding proximal stress in Model 3 only minimally influences the coefficient for distal adversities. Thus, there is little evidence to suggest that proximal stress exposure mediates the long-term impact of earlier adversities. The effects of early and later stressors on alcohol dependence are clearly independent and apparently cumulative. The proximal stress coefficient (b=.207) is considerably larger than that for distal events (b=.091), which seems to imply a higher level of predictive significance or importance. However, these coefficients and their associated odds ratios (not shown) reflect only the increment in risk associated with each single additional event experienced, with the level of the other stress measure held constant. A more meaningful illustration of the comparative importance of distal and proximal adversities is provided by estimates of the relative odds of first onset associated with scores one standard deviation above and below the means of their respective distributions (comparable to standardizing the measures of association). By this method, the net strength of the distal stressors' relationship is represented by an odds ratio of 2.2, when the magnitude of proximal stress is controlled, compared with 1.7 for proximal stress with distal stress controlled.

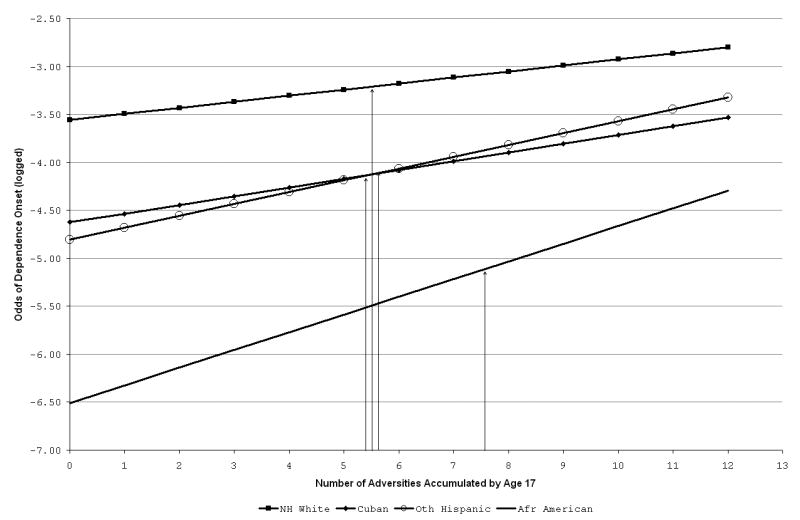

Inspection of the ethnicity coefficients makes clear that observed variations in stress exposure contribute nothing toward explaining ethnic group differences in the onset of alcohol dependence disorder. The results of separate regression analyses shown in Figure 1 illustrate that, despite the fact that differences in cumulative exposure to adversity do not contribute toward explaining the group differences in prevalence, cumulative stress is equally associated with the subsequent onset of alcohol dependence in all groups. Interaction tests did not reveal any differences in these slopes across ethnic groups, suggesting that cumulative exposure to adversity is equally harmful within all ethnic groups studied. Similarly, no interactions were detected involving gender or socioeconomic level.

Fig. 1.

Risk of first onset of alcohol dependence disorder (log-odds) by number of prior adversities, with mean exposure count indicated for each group.

The last two models in Table 3 present an effort to assess a plausible alternative hypothesis for our findings: that problematic individuals tend to place themselves in circumstances in which stress exposure is more likely, on the one hand, and are at elevated risk for alcohol dependence, on the other. The fourth model controls for childhood conduct disorder, which considers serious behavior problems up to age 15, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, and prior psychiatric disorders (including depression, dysthymia, post-traumatic stress disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder). The coefficients for both distal and proximal adversity are diminished somewhat with the addition of these controls—the net magnitude of association with distal stressors in particular is reduced by half. Although two of these additions represent significant independent predictors of alcohol dependence, the observed stress associations remain prominent in the context of controls for these collective antecedent problems.

Similarly, Model 5 shows that the relationship between cumulative stress exposure and alcohol dependence is not due to any common association with prior drug dependence disorder. Additional analyses (not shown) justifies the same conclusion with respect to family history of substance use problems. One quarter of the sample reported that either a parent or someone else close to them drank or used drugs so much that it caused problems for the family. While this indicator was a significant positive predictor of subsequent alcohol dependence when added alone to model 1, its association (b=.421) became nonsignificant (b=.226) when cumulative stress was entered.

5. Discussion

These results indicate that the level of major stressful experiences is quite high among young people, at least in South Florida. While most ethnic groups averaged 7-8 adversities in our inventory, the African Americans reported more than 10. This difference in the lifetime experience of adversity reflects a crucial dimension of the distinctive contexts and histories of African Americans in the United States. Adversities manifest the structurally embedded disadvantage that disproportionately characterizes the lives of minorities.

However, it is clear that differences in exposure to adversity can provide little assistance in understanding the relatively low rate of alcohol dependence among African Americans. If exposure to adversity were equal across groups, the more favorable outcome observed among African Americans would be even more pronounced. This should not be taken to imply that stress exposure is not an important risk factor among African Americans. As shown in Figure 1, the slopes estimated separately within ethnic groups demonstrate essentially equal relationship between cumulative adversity and risk for alcohol dependence. One possibility is that the effects of the greater average level of adversity among African Americans tend to be manifested in physical health problems including hypertension and cardiovascular disease.

Our report focuses on alcohol dependence as defined by DSM-IV: the co-occurrence of three or more of seven symptoms of dependence in a single year. We omit consideration of alcohol abuse from our main analysis because DSM-IV criteria arguably do not meaningfully distinguish problematic from non-problematic drinkers during this stage of life. Regular alcohol use approaches being normative during late adolescence and young adulthood, and a youth would qualify for abuse by having a single recurring role-related problem associated with alcohol use. In addition, a youth would qualify for abuse by having a single recurring role-related problem associated with alcohol use. Thus, this diagnosis is likely to be confounded with one's evolving social role set. For example, those who do not drive are at inherently less risk for abuse by way of persistent drunk driving than are drivers. Similarly, only jobholders can have problems at work due to alcohol use. Finally, available evidence shows that alcohol dependent youths experience greater levels of stress than those who meet criteria for only abuse (Clark et al. 1997; Johnson and Pandina, 2000), which suggests that stress is a more salient risk factor for dependence than abuse. In our view, predicting the onset of dependence irrespective of abuse constitutes a compelling test of the stress hypothesis.

Surprisingly we found no gender difference in the lifetime prevalence of alcohol dependence disorder. Epidemiological reports involving older, nationally representative, samples uniformly indicate higher rates of alcohol abuse and dependence disorders among males (Grant and Dawson, 1999; Kessler et al., 1994). Results previously reported from this study of South Florida young adults revealed dramatically higher rates of both lifetime and 12-month alcohol abuse disorder among males and, of course, the nearly equal prevalence of dependence across gender we have also reported here (Turner and Gil, 2002). In a separate analysis (not shown) we found that, among those who did not meet criteria for alcohol dependence, 24 percent of the males still qualified for abuse; this was twice the proportion that qualified for abuse among the non-dependent females. Thus the greater overall rate of pathological alcohol use generally found among males may be attributable to differences in rates of diagnosable abuse, not dependence. We repeated the survival analysis reported above using first onset of alcohol dependence or abuse as the outcome variable. We found a significant gender effect, and risk for onset increased with increasing socioeconomic status. The stress coefficients remained virtually unchanged, and the addition of stress did not explain the gender, ethnic, or socioeconomic status differences. As in the results for dependence alone, the stress effects were not meaningfully diminished when controls for prior disorders were added.

The finding suggesting that reports of gender contrasts may arise largely from gender differences in the tendency for adolescents and young adults to meet criteria for abuse is consistent with some recent research on adolescents. These studies have found the prevalence of substance use and dependence among females to be the same or even greater than that among males (Kandel et al., 1997; Sloboda, 2002; Warner, Canino and Colón, 2001). The trend toward a narrowing gender gap in alcohol dependence problems over time may be attributable to a convergence in rates of initial symptom onset among the youngest men and women (Nelson, Heath and Kessler, 1998). Holdcraft and Iacono (2002) document a gender by age interaction associated with alcohol dependence that is consistent with a smaller gender difference at younger ages. Finally, evidence of more rapid progression from the initiation of regular drinking to dependence, despite their later initiation, among clinically addicted women than among their male counterparts (Hernandez-Avila et al., 2002), may also help explain the absence of a gender difference in this community sample of young adults.

This paper has focused on the hypothesis that major adversities accumulate over the life course and, the greater the accumulation, the greater the risk for alcohol dependence. Our analyses employed an unweighted count of events to estimate the level of acquired stress burden. This strategy was adopted despite the logic of the expectation that impact potential varies across events because research has failed to demonstrate that indices weighted on the basis of judges' ratings of the change or seriousness involved increases correlations with outcomes (Ross and Mirowsky, 1979; Shrout, 1981; Turner and Wheaton, 1995). We contend that subjective or self reported weights are to be avoided because they tend to confound event scores with outcomes and inevitably confuse stress exposure with coping ability. As Turner and Wheaton (1995:44) have argued, “the weight attached by a respondent to an event will be largely a function of his or her capacity, real or perceived, to resolve that event in emotional or practical terms” and that “such capacity is a function of coping skills and of the availability of social and personal resources.” We do not suggest uniformity in potential risk significance across widely differing types of events. Indeed, inspection of the pattern of significant odds ratios in Table 2 suggests that events involving violence may be of particular risk relevance. Our contention, well supported by the finding presented above, is that there is a kind of dose-response relationship in which quantity of cumulative exposure over time is a major risk factor, independent of variations in the type or severity of the events involved.

Our retrospective measurement of lifetime exposure to major adverse events may raise the question of reliable measurement. The problem of unreliably reporting or forgetting does not apply equally to all events that might be experienced. For example, it is unlikely that subjects would fail to report in response to specific questions about highly salient events such as the death of one's child or parents' divorce. There is a range of memorable life events that can be measured with reasonable accuracy and which, singly or in combination, may constitute important health risk factors. This paper reports on the significance for alcohol dependence of the lifetime cumulative experience of what we believe to be the widest range of major adverse life events so far studied. The available evidence on the properties of such lifetime checklists is limited, but it indicates satisfactory reliability. In a two-wave study with interviews spaced one year apart, all but two of a 20-item subset of the present measure met minimum consistency standards of kappa at least .60, while more than half of the items kappa exceeded .70 in a sample aged 18-55 (Wheaton and Roszell, personal communication). These results “suggest that most items are reported with acceptable to very good levels of reliability” (Wheaton, et al., 1997:56). There seem grounds for anticipating that reliability would not be any lower in our considerably younger sample.

In our view, the findings presented suggest that high levels of lifetime exposure to adversity are implicated causally in the onset of alcohol dependence. Comparing the relative magnitude of effects of distal and proximal adversities revealed that distal stress is a surprisingly powerful predictor of alcohol dependence. This finding points toward prevention strategies targeted at persons much younger than late adolescence, when first onset of dependence is most likely. It is suggested that the identification of adolescents most in need of, or who might most benefit from, an intervention would be importantly aided by information on level of prior exposure to major adverse life events. The finding of no partial association between familial substance use problems and the youths' own risk for alcohol dependence when lifetime cumulative adversities were controlled suggests that the influence of such problems may be mediated through consequent adverse experiences.

We previously reported findings involving drug dependence disorder where distal and proximal stress exposure independently predicted first onset, supporting the generalizability of the stress hypothesis across substance types. (Turner and Lloyd, 2003). It is important to note in this connection that there is very little comorbidity between drug and alcohol dependence disorder within this relatively young population. Only 67 of the 365 participants who met criteria for drug or alcohol dependence qualified for both on a lifetime basis. Alcohol and drug dependence appear to be alternate behavioral responses among persons having similarly stressful backgrounds.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations inherent in retrospective survey methods. Both alcohol dependence and psychiatric diagnoses were derived from a single structured interview that relies on retrospective recall. While the young age of this cohort and the careful employment of the life calendar strategy presumably minimize recall and temporal ordering problems, they remain of some concern. The hypotheses investigated in this report would be more compellingly supported if the same data were prospectively gathered. However, there seems little prospect of a community-based study that will gather such data prospectively on a sufficiently large sample and over a long enough period to assess the central hypothesis examined here. The fact that study participants represent a narrow age range advises caution in generalizing these findings to other age groups, particularly given the remaining years of significant risk for the onset of alcohol dependence. Finally, although our sample can be said to be representative of young adults in Miami-Dade County, Florida, the distinct nature of the resident Hispanic population suggests caution in generalizing to other areas of the country.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aktan GB, Calkins RF, Ribisl KM, Krolikzak A. Test-retest reliability of psychoactive substance abuse and dependence diagnoses in telephone interviews using a modified diagnostic interview schedule-substance abuse module. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1997;23:229–248. doi: 10.3109/00952999709040944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Sage University Paper series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 07-46. Sage Publications; Beverly Hills, CA: 1984. Event history analysis: regression for longitudinal event data. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Vers 3 rev. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Vers 4. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Aquilino WS. Interview mode effects in surveys of drug and alcohol use: a field experiment. Public Opinion Q. 1994;58:210–240. [Google Scholar]

- Biafora F, Jr, Warheit G, Vega WA, Gil AG. Stressful life events and changes in substance use among a multiracial/ethnic sample of adolescent boys. J Community Psychol. 1994;22:296–311. [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Sonne SC. The role of stress in alcohol use, alcoholism, treatment, and relapse. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23:263–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris T. Social Origins of Depression. Free Press; New York: 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA. Alcohol use and type of life events experienced during adolescence. Psychol Addict Behav. 1987;1:104–107. [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Finkelhor D. Impact of child sexual abuse: a review of the research. Psychol Bull. 1986;99:66–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryer J, Nelson B, Miller J, Krol P. Childhood physical and sexual abuse as factors in adult psychiatric illness. Am J Psychiat. 1987;144:1426–1430. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.11.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Lesnick L, Hegedus AM. Traumas and other adverse life events in adolescents with alcohol abuse and dependence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1744–1751. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199712000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Frone MR. Work stress and alcohol effects: a test of stress-induced drinking. J Health Soc Behav. 1990;31:260–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa FM, Jessor R, Turbin MS. Transition into adolescent problem drinking: the role of psychosocial risk and protective factors. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:480–490. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman D, Thornton A, Camburn D, Alwin D, Young-DeMarco L. The life history calendar: a technique for collecting retrospective data. In: Clogg CC, editor. Sociological Methodology. Institute for Social Research; University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: 1998. pp. 37–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Alcohol and drug use, abuse, and dependence: classification, prevalence, and comorbidity. In: McCrady BS, Epstein EE, editors. Addictions: A Comprehensive Guidebook. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. pp. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Green R. Child sexual abuse: immediate and long-term effects and intervention. J Am Acad Child Psy. 1993;32:890–902. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood H, Fountain D, Livermore G. Economic costs of alcohol abuse and alcoholism. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism, vol 14, The Consequences of Alcoholism: Medical, Neuropsychiatric, Economic, Cross-cultural. Plenum Press; New York: 1988. pp. 307–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Avila CA, Poling J, Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HR. Progression of drug and alcohol dependence among women entering substance abuse treatment: evidence for telescoping. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66(Suppl):S79. [Google Scholar]

- Holdcraft LC, Iacono WG. Cohort effects on gender differences in alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2002;97:1025–1036. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes S, Robins L. The role of parental disciplinary practices in the development of depression and alcoholism. Psychiatr. 1988;51:24–36. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1988.11024377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton J, Compton WM, Cottler LB. Assessing psychiatric disorders among drug users: reliability of the revised DSM-IV. NIH Publication 9:4395. In: Harris L, editor. NIDA Research Monograph: Problems of Drug Dependence. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Washington, DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson V, Pandina R. A longitudinal examination of the relationships among stress, coping strategies, and problems associated with alcohol use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:696–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson V, Pandina R. Alcohol problems among a community sample: longitudinal influences of stress, coping, and gender. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35:669–686. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D, Chen K, Warner LA, Kessler RC, Grant B. Prevalence and demographic correlates of symptoms of last year dependence on alcohol, nicotine, marijuana and cocaine in the U.S. population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44:11–29. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders i: educational attainment. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1026–1032. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, Power C. Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:778–783. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD. Childhood parental loss and adult depression. J Health Soc Behav. 1991;32:205–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miami-Dade Public Schools. [November, 2000]; www.dadeschools.net.

- Midanik LT, Hines AM, Greenfield TK. Face to face versus telephone interviews: using cognitive methods to assess alcohol survey questions. Contemp Drug Probl. 1999;26:673–693. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E, Brown GW. Life events, psychiatric disturbance, and physical illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136:326–338. doi: 10.1192/bjp.136.4.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol and Stress — Alcohol Alert No 32 PH 363. [April 20, 2007];1996 April; Http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa32.htm.

- Nelson CB, Heath A, Kessler RC. Temporal progression of alcohol dependence symptoms in the U.S. household population: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:474–483. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Stress-motivated drinking in collegiate and postcollegiate young adulthood: life course and gender patterns. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:219–227. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan JL, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version IV. Mimeo, St; Louis, MO: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Regier DA. Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Free Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer J. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn P, Seeley J. Comparability of telephone and face-to-face interviews in assessing axis I and II disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1593–1598. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. A comparison of life-event-weighting schemes: change, undesirability, and effect-proportional indices. J Health Soc Behav. 1979;20:166–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier LM, Botvin GJ, Miller NL. Life events, neighborhood stress, psychosocial functioning, and alcohol use among urban minority youth. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 1999;9:19–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Gershuny BS, Peterson L, Raskin G. The role of childhood stressors in the intergenerational transmission of alcohol use disorders. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:414–427. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE. Scaling of stressful life events. In: Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP, editors. Stressful Life Events and Their Contexts. Prodist; New York: 1981. pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. It's about time: using discrete-time survival analysis to study duration and timing of events. J Educ Stat. 1993;18:155–195. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sloboda Z. Changing patterns of drug abuse in the United States: connecting findings from macro- and microepidemiologic studies. Subst Use Misuse. 2002;37:1229–1251. doi: 10.1081/ja-120004181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Gil A. Psychiatric and substance use disorders in South Florida: racial/ethnic and gender contrasts in a young adult cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:43–50. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Lifetime traumas and mental health: the significance of cumulative adversity. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:360–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Cumulative adversity and drug dependence in young adults: racial/ethnic contrasts. Addiction. 2003;98:305–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Wheaton B. Checklist measures of stressful life events. In: Gordon L, Cohen S, Kessler RC, editors. Measuring Stress: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. pp. 29–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gil AG. Drug Use and Ethnicity in Early Adolescence. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Warner LA, Canino G, Colón HM. Prevalence and correlates of substance use disorders among older adolescents in Puerto Rico and the United States: a cross-cultural comparison. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63:229–643. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B, Roszell P, Hall K. Traumatic stressors and risk of psychiatric disorder. In: Gotlib IH, Wheaton B, editors. Stress and Adversity Over the Life Course. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, U.K.: 1997. pp. 50–72. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Weiler BL, Cottler LB. Childhood victimization and drug abuse: a comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. J Consult Clin Psych. 1999;67:867–880. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Windle R. Coping strategies, drinking motives, and stressful life events among middle adolescents: associations with emotional and behavioral problems and with academic functioning. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:551–560. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 1.0. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1990. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.