Abstract

Patients with social anxiety disorder who are seen in clinical practice commonly have additional psychiatric comorbidity, including alcohol use disorders. The first line treatment for social anxiety disorder is selective-serotonin-reuptake-inhibitors (SSRIs), such as paroxetine. However, the efficacy of SSRIs has been determined with studies that excluded alcoholics. Forty two subjects with social anxiety and a co-occurring alcohol use disorder participated in a 16-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial to determine the efficacy of paroxetine for social anxiety in patients with co-occurring alcohol problems. Paroxetine was superior to placebo in reducing social anxiety, as measured by the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale total and subscale scores and additional measures of social anxiety. This study provides the first evidence-based recommendation for the use of an SSRI to treat social anxiety in this patient population.

Keywords: social anxiety disorder, dual-diagnosis, comorbidity, SSRI

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder, also known as social phobia, is characterized by an excessive or unreasonable fear of scrutiny in social situations (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The lifetime prevalence of social anxiety disorder is 5%, and the mean age of onset is 15 years (Grant et al., 2005). Two types of social anxiety disorder have been identified. Generalized social anxiety disorder indicates that the affected individual fears multiple social situations (ie, eating, writing, speaking in public), whereas individuals who have only one social fear (typically public speaking fears) are considered to have the non-generalized type (Mannuzza et al., 1995). The generalized type is considered to be more severe and more debilitating (Kessler, Stein & Berglund, 1998; Wittchen & Beloch, 1996; Wittchen & Fehm, 2001) and is the type most likely to seek treatment (Kessler et al., 1998).

One of the challenges in treating generalized social anxiety disorder is that it is often complicated by an additional Axis I disorder, most commonly other anxiety disorders, affective disorders, and/or substance use disorders (Burns & Teesson, 2002; Chartier, Walker & Stein, 2003; Kessler et al., 1998; Magee, Eaton, Wittchen, McGonagle & Kessler, 1996; Merikangas & Angst, 1995; Rosenbaum, 1995). These patients tend to have more severe social anxiety and greater functional impairment (Lecrubier, 1998). Unfortunately, little is known about how to treat social anxiety disorder in the context of a current comorbid psychiatric condition, as clinical trials typically exclude individuals with comorbid disorders (Herbert, 1995). In fact, a recent consensus paper on investigating treatments for social anxiety disorder specifically recommends excluding comorbidity because it may interfere with the measurement of efficacy (Montgomery et al., 2004). Consequently, there is a lack of evidence-based research to guide the treatment of social anxiety in individuals with comorbid conditions. A recent review of pharmacotherapy for social anxiety disorder and a recent review of treatment recommendations for persons with a co-occurring affective or anxiety and substance use disorders specifically have called for more research on comorbid samples (Stein, Ipser & Van Balkom, 2006; Watkins, Hunter, Burnam, Pincus & Nicholson, 2005), including alcohol use disorders (i.e. alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence), which occurs in about 20% of individuals seeking treatment for social anxiety disorder (Burns et al., 2002; Morris, Stewart & Ham, 2005; Van Ameringen, Mancini, Styan & Donison, 1991).

Given that one in five individuals who seek treatment for social anxiety disorder has an alcohol use disorder, an important question is whether a first-line treatment for social anxiety disorder, such as an SSRI, is a safe and effective treatment for social anxiety in this patient population. To our knowledge, the only study addressing this question was a pilot project conducted by our group (Randall et al., 2001). Those results, based on a small sample size and eight-week treatment period, were encouraging, but a larger scale study was warranted to confirm the pilot study results.

The present study was conducted to follow-up and extend our pilot study to include a larger sample size and a longer treatment period. We chose paroxetine as the treatment for social anxiety disorder, as its efficacy has been demonstrated with well-controlled clinical trials (Baldwin, Bobes, Stein, Scharwaechter & Faure, 1999; Liebowitz, Gelenberg & Munjack, 2005; Stein et al., 1998), and it was used in our pilot study. The randomized clinical trial was 16 weeks and double blind. It included individuals seeking treatment for social anxiety disorder who also met DSM-IV criteria for an alcohol use disorder. All individuals reported deliberate drinking to cope with social stress. Data on social anxiety severity and alcohol use were collected weekly using standardized and validated instruments. Research and clinical assessments of social anxiety were conducted separately to insure independent ratings of outcome variables. Data analysis used state-of-the-art statistical methods. The effects of paroxetine treatment on drinking outcomes (e.g., quantity/frequency of drinking, drinking to cope with social anxiety) is presented in more detail in a stand-alone publication. The current paper focuses only on social anxiety outcomes. The a priori hypothesis tested was that the paroxetine-treated group would demonstrate improvements in social anxiety compared to the placebo-treated group.

1. Methods

1.1 Subject selection

Participants were recruited from the community through advertisements in the local media. Individuals were encouraged to call study personnel for a confidential telephone screening interview if they were interested in participating in a research study on the pharmacologic treatment of social anxiety; alcohol use was not mentioned in the advertisements. The screening interview included questions from the Mini-SPIN (Connor, Davidson, Sutherland & Weisler, 1999) which helped determine whether the individual would likely meet diagnostic criteria for social anxiety disorder. Individuals were also asked questions related to their quantity and frequency of drinking. The telephone screening was used to determine whether an individual should be invited for an in-person interview.

The in-person eligibility interview was conducted on 102 individuals, who first signed an informed consent agreement approved by the university’s institutional review board. All in-person interviews were conducted by clinically-trained research personnel and by the study physician (SWB). Each individual was evaluated by study personnel using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID); (First, Spitzer, Gibbon & Williams, 2001) the results of the evaluation were used to determine eligibility. Individuals were required to meet diagnostic criteria for current social anxiety disorder, generalized type, and current alcohol use disorder (alcohol abuse or dependence). They were excluded if they had current bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, substance abuse or dependence other than alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, or presence of significant suicidality. Any SCID evaluation completed by a master-level clinician was followed up with a review by doctoral level clinicians trained and experienced in SCID administration in clinical trials.

In addition to these diagnostic criteria for inclusion, a medical examination, laboratory tests, and an assessment battery (described below) of standardized instruments were used to determine final eligibility. The study physician supervised a Physician Assistant who collected the medical history and carried out the physical examination. To be included in the study, individuals had to (1) be 18 to 65 years old; (2) have sufficiently severe social anxiety disorder, as defined by a total score of at least 60 on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale; (3) report using alcohol to cope with social anxiety; and (4) consume at least 15 standard drinks1 in the previous 30-day period. Medical exclusion factors included: (1) history of prior medical detoxification from alcohol; (2) current use of psychotropic medications; (3) seeking treatment for alcohol problems; (4) urine drug screen positive for illicit drugs other than marijuana; and (5) liver enzymes greater than three times normal levels. History of prior medical detoxification or treatment seeking for alcohol problems was exclusionary for ethical reasons since no explicit alcohol intervention was provided. In total, 42 of 102 individuals interviewed met study requirements for inclusion and were randomized to treatment.

1.2. Randomization to treatment

Following determination of eligibility, subjects were randomized to either paroxetine or matching capsule placebo, using a computerized urn randomization program. Urn randomization helps insure equal representation between the medication and placebo groups of potentially confounding variables (Stout, Wirtz, Carbonari & Del Boca, 1994). Urn randomization variables were gender, social anxiety severity (baseline LSAS total score ≤ vs. > 76), and the presence of co-occurring major depressive disorder as determined by the SCID. Group assignment was maintained by an investigational pharmacist, who also prepared each week’s supply of study medication. All individuals involved in direct care or evaluation of study subjects, or who were involved in study supervision, were blind to group assignment. Data analyses were conducted maintaining coded group assignment (group A vs. group B), and the blind was broken when analyses were completed.

1.3. Treatment

All subjects were initiated at a dose of 10 mg per day of paroxetine or matching placebo. Active medication and placebo were over-encapsulated by the investigational pharmacy with 100 mg of riboflavin, a biomarker used to measure medication compliance (Dubbert et al., 1985). The titration plan in the protocol was to increase the dose weekly over four weeks from 10 to 20 to 40 to 60 mg daily, pending tolerability. If dose reductions were needed, these were typically achieved by reducing the dose by 10 or 20 mg. Titration delays were also used as needed to minimize side effects. No limits were placed on number of dose reductions.

All subjects underwent a weekly research assessment visit with the research assistant which was then followed by a medication management visit with a study clinician on the same day for the 16-week study. All clinicians (three MD clinicians and one Physicians Assistant) followed the same scripted protocol for medication management visits and were supervised by the study physician. The medication management visit included evaluation of the specific situations that were feared and/or avoided to provide enough information to allow the clinician to rate the severity and improvement (relative to baseline) of the social anxiety problem using the Clinical Global Index (CGI, described below). In addition, clinicians reviewed the risks and benefits of taking the study medication and recorded adverse events weekly, using a side effects checklist. The clinician provided the research medication at the completion of the weekly visit. At the end of the 16 week trial, paroxetine or matching placebo was tapered and discontinued.

During the first four weeks of the study, the subject had the option of one individual therapy session. This non-mandatory session was aimed at improving study retention and medication compliance and was conducted by a Master or Doctorate level therapist trained in Motivational Enhancement Therapy (Miller, Zweben, DiClemente & Rychtarik, 1995). Twenty-eight of the 42 subjects (67%) opted to participate in this individual session; there were no differences (p >.10) in percent of each group that participated in this session, and participation in this session did not impact participants’ likelihood to complete treatment.

Research personnel were not involved in clinical management of research subjects, and research assessments on social anxiety were not shared with clinicians. In this way, clinical and research ratings were collected independently. The medication management visit was audiotaped, and the tapes were reviewed by one of the non-clinician investigators (SET) to evaluate adherence by the clinician to the scripted visit for treatment quality assurance. Further quality assurance measures included periodic check of pharmacy accuracy in packing drug vs. placebo. Subjects were financially remunerated $50.00 for participating in the week 16 visit.

1.4. Compliance

Medication compliance was measured two ways: (1) capsules were counted at each weekly visit during the medication management visit, and clinicians rated whether 75% of the prescribed capsules were missing (a positive compliance rating for that week) and (2) urine samples were collected from participants randomly throughout the trial, and urinalysis was performed with fluorescence assay to determine the concentration of riboflavin. Concentration of at least 1500 ug/ml indicated positive riboflavin presence in that sample, thereby providing an indication of capsule compliance that week. Both compliance measures were assessed for all participants, regardless of treatment group assignment.

1.5. Outcome measures

The primary treatment outcome was assessed using the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) (Liebowitz, 1987). Additionally, as described below, LSAS subscale scores (Fear and Avoidance), the Clinical Global Index improvement subscale (CGI-I), and the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) total score were used as secondary outcome measures of social anxiety severity.

Social Anxiety Outcome Measures

The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) is a psychometrically validated standardized questionnaire used in research studies to quantify social anxiety severity (Heimberg et al., 1999). It can be either researcher-administered or self-rated, both of which have proven psychometric support (Baker, Heinrichs, Kim & Hofmann, 2002; Heimberg et al., 1999; Oakman, Van Ameringen, Mancini & Farvolden, 2003). We used the self-rating format in the present study. The LSAS total score ranges from 0 to 144. We chose a priori to use the LSAS total score as the primary outcome measure, consistent with previous clinical trials with paroxetine for social anxiety (Baldwin et al., 1999; Liebowitz et al., 2005; Stein et al., 1998). The Fear and Avoidance subscale scores each range from 0 to 72. Because of the specific sample assessed—individuals who use alcohol to cope with social anxiety—the LSAS instructions were modified to instruct participants to rate each situation as if alcohol was not available to cope with the situation (Thomas, Randall, Willard & Johnson, 2001).

The Clinical Global Index (CGI) is a traditional instrument utilized in pharmaceutical trials (Guy, 1976). It has acceptable psychometric properties (Zaider, Heimberg, Fresco, Schneier & Liebowitz, 2003). The clinician rates on a 1–7 scale the severity of social anxiety (CGI-S). At weekly visits throughout the trial the clinician also rates improvement in social anxiety severity as compared to baseline on the same 1–7 point scale (CGI-I). Consistent with other trials, a responder was defined as having either a “1” or “2” (much improved, or very much improved) on the CGI-I.

The Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) (Connor et al., 2000) was also administered to participants during the trial. Total scores from the SPIN were used to confirm the effects of treatment on social anxiety severity. The SPIN is a self-report instrument containing 17 items reflective of symptoms of social anxiety. The individual rates how severely s/he experiences each item, from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Total scores range from 0 to 68; a score of 19 distinguishes socially anxious individuals from controls (Connor et al., 2000). The SPIN has proven psychometric properties and is sensitive to treatment effects (Connor et al., 2000).

1.6. Data analysis

Groups were compared on baseline and demographic variables using t-tests and chi-square tests (α = 0.05). To test whether paroxetine was more effective than placebo at reducing social anxiety, total scores on the LSAS were analyzed as a mixed model (SPSS: Proc Mixed) with an unstructured variance/covariance matrix. Mixed model analysis is robust to “non-informative” missing data and avoids the more restrictive assumptions (e.g. compound symmetry) of standard repeated measures analysis of variance. Outcome data were conditioned on baseline scores for each measure. The initial overall analysis was performed as a factorial combination of drug group (paroxetine vs. placebo) by week (1–16). Follow-up contrasts were performed with a nested model (day with phase) where phase was either “initiation” (weeks 1–6) or “maintenance” (weeks 7–16) of treatment.

Scores from the CGI-I were used in a secondary outcome analysis and analyzed with a generalized estimation equation (GEE) analysis using HLM 6.0. Interactions were tested as joint tests of group differences on sets of within group contrasts. For the secondary social anxiety dependent variable, the SPIN and the subscales of the LSAS, a last-point-carried forward approach was used to impute missing week 16 data for four individuals, and groups were compared with t-tests to examine mean group differences on percent change from baseline. Data from all subjects who were randomized to treatment were included in the analysis, according to intent to treat (ITT) standards.

2. Results

2.1. Demographic and baseline data

There were no significant differences at baseline between groups (n=20 paroxetine and n=22 placebo), including age, gender, ethnicity, social anxiety severity, and alcohol use severity. Per inclusion criteria, all met diagnostic criteria for social anxiety disorder. Participants had relatively severe social anxiety disorder, with an average LSAS score of 90 (SD=17), and most participants (86%) received a baseline CGI severity rating by the physician of at least “markedly ill.” Age of onset was in the preteen years (M=12, SD=4). All participants endorsed using alcohol to cope; most participants (79%) met diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence vs. abuse (21%). By chance, more individuals with an alcohol abuse diagnosis were randomized to the placebo group (n=7) than the paroxetine group (n=1), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.07). Mean age of onset of alcohol problems was 21 (SD=5). The onset of alcohol use disorder occurred after that of social anxiety disorder in all but one subject. On average, alcohol use disorder followed social anxiety onset by 9 years (SD=7). Participants drank alcohol approximately three days per week during the 30-day baseline period, drinking about six drinks (SD=3.5) on each occasion. The severity of dependence for both groups had a mean score of 10 on the Alcohol Dependence Scale (Skinner & Horn, 1984). Diagnoses of other co-occurring Axis I diagnoses were rare. In addition to Major Depressive Disorder (n=4), four additional Axis I disorders were represented in the sample, though not frequently: Dysthymia (n=3); Specific phobia (n=1); Generalized Anxiety Disorder (n=8); and current cannabis dependence (n=3). Regarding depression, scores on the Beck Depression Inventory were similar to those previously described in subjects with anxiety disorders (Beck, Steer & Brown, 1996). These and other baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics, and baseline severity of social anxiety and alcohol use by group.

| Paroxetine n=20 | Placebo n=22 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, M (SD) | 28 (6.5) | 30 (8.3) | NS |

| Male | 55% (11) | 50% (11) | NS |

| Caucasian | 100% (20) | 82% (18) | NS |

| Social Anxiety Severity | |||

| Percent with Social Anxiety Disorder (DSM-IV) | 100% (20) | 100% (22) | NS |

| Age onset of Social Anxiety Disorder | 13 (4.7) | 11 (3.4) | NS |

| Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) | |||

| Total score | 87 (14.9) | 93 (18.5) | NS |

| Fear subscale | 46 (7.0) | 48 (8.9) | NS |

| Avoidance subscale | 41 (8.7) | 44 (10.0) | NS |

| Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN), total score | 45 (7.8) | 45 (9.0) | NS |

| Percent rated ≥ "markedly severe" at baseline (CGI severity) | 90% (18) | 82% (18) | NS |

| Drinking Indices | |||

| Percent AUD (abuse or dependence, DSM-IV) | 100% (20) | 100% (22) | NS |

| Percent endorsing drinking to cope during social situations | 100% (20) | 100% (22) | NS |

| Age onset AUD | 20 (3.6) | 21 (6.0) | NS |

| Alcohol Dependence Severity score | 10.5 (7.3) | 9.4 (5.2) | NS |

| Drinking quantity and frequency | |||

| Drinks per week | 14.6 (11.3) | 18.6 (14.3) | NS |

| Drinks per drinking day | 5.4 (2.8) | 6.6 (4.1) | NS |

| Depression Indices | |||

| Percent with current Major Depressive Disorder (DSM-IV) | 10% (2) | 9% (2) | NS |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 17 (10.3) | 17 (11.0) | NS |

All values shown are means (SD) or percentages (n). There were no significant differences between groups, all p values > .05.

2.2. Compliance, dosing and side effects

In general, participants were compliant with taking medication, as reflected by capsule counts and urine screens analyzed for riboflavin concentration. Based on capsule counts, 90% of subjects in the paroxetine group and 86% of subjects in the placebo group were judged compliant, as defined by taking at least 75% of each week’s prescribed capsules. Riboflavin results were analyzed similarly: if at least 75% of a subject’s urine samples during the trial were positive for high riboflavin (≥1500 ug/ml), s/he was judged compliant. Using this approach, 80% of participants in the trial were compliant; there was no significant difference in compliance rates between groups, X²(1)=.07, p, NS.

The titration schedule worked well in this trial, and the average final dose of paroxetine was 45 mg/day. The majority of participants (85%) reached their stable dose by week 6. There were no group differences in final dose or in attendance at medication management visits between the paroxetine and placebo groups. All but four participants provided week 16 (end of trial) data, for a 90% research data completion rate.

As elicited from a 32 item side effects checklist reviewed with the subject weekly, only three side effects were significantly more common in the paroxetine vs. placebo group. The most commonly reported side effect (reported by 55% of subjects on paroxetine) was anorgasmia/delayed ejaculation. Of subjects reporting this effect, most (8/11, 73%) were men. The number of subjects who dropped out of the trial because of side effects were 1 and 0 for the paroxetine and placebo group, respectively. No serious adverse events occurred. These results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Paroxetine dosing, compliance, and adverse events.

| Paroxetine | Placebo | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg/day) at week 16 (or at final visit) | 45 (15.4) | 53 (15.5) | .08 |

| Number of weeks in the trial | 12 (5.5) | 13 (5.0) | NS |

| Percent subjects compliant by capsule count measures | 90% | 86% | NS |

| Percent compliant by riboflavin measures* | 79% | 82% | NS |

| Adverse events: % (n) who reported the side effect at least once during the trial where Paroxetine > Placebo, at p<.05 | |||

| Tremor | 45% (9) | 14% (3) | .03 |

| Myoclonus | 35% (7) | 5% (1) | .01 |

| Anorgasmia/Delayed ejaculation | 55% (11) | 18% (4) | .01 |

All values show means (SD) or percentage (n).

Based on n=19 for paroxetine group and n=17 for placebo group, as six subjects did not provide urine samples for riboflavin analysis.

2.3. Social anxiety outcomes

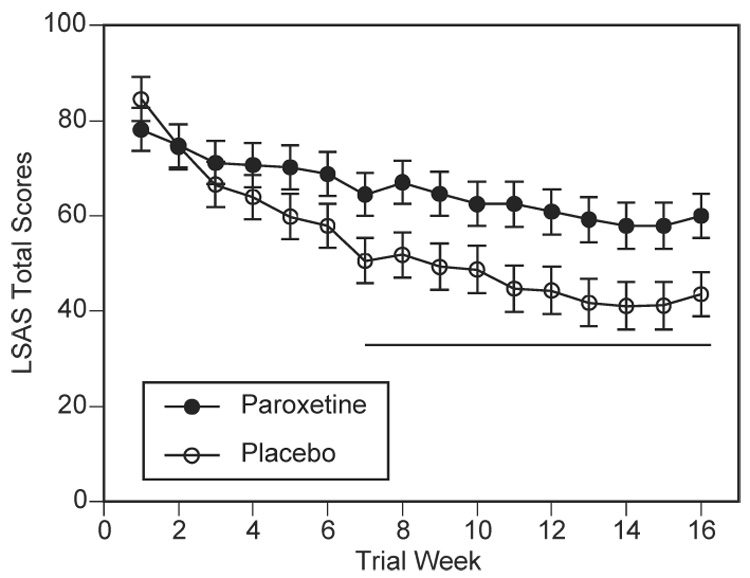

As shown in Figure 1, LSAS total scores dropped robustly in the paroxetine-treated group across the first several weeks of treatment and then remained low relative to placebo-treated group throughout the rest of the trial. The placebo group showed a small reduction in scores across the trial. These observations were supported by the mixed model analysis. The initial overall analysis revealed a highly significant group × week interaction (F(15,39)=3.79, p=.0004). Subsequent analysis revealed a strong group × phase interaction (F(1,39)=6.18, p=.017), reflecting the reported finding that paroxetine’s therapeutic effect onsets gradually during the first six weeks of initiation. Further analysis of the maintenance phase alone revealed a significant main effect of group (F(1,39)=4.32,p=.04), with no group × week interaction (F(9,38)=1.28, p=.28). Overall, the analysis suggests that the drug effect (as predicted) emerged over the first 6 to 7 weeks and remained stable thereafter. LSAS total scores were reduced by an average of 53% (SE=6.6) for the paroxetine group vs. 32% (SE=6.2) for the placebo group, a statistically significant difference, t(40)=2.34, p=.02.

Figure 1.

Effect of paroxetine on social anxiety severity indexed by LSAS total scores. Paroxetine (open circles) significantly reduced LSAS scores by week 7 compared to placebo (closed circles), and treatment gains were maintained through week 16. The underlining bar reflects the maintenance phase and where weekly the group means differed at p < .05. Error bars reflect standard error of the mean.

Independent confirmation of the effect of paroxetine on improving social anxiety was evident in the analyses of the CGI improvement scores, which showed a similar pattern to the self-rated LSAS results. The overall group × week interaction was significant (X²(5) =13.7, p=.017), and the main effect during the maintenance phase (weeks 7–16) showed that paroxetine-treated subjects improved to a greater extent than did placebo-treated subjects, t(40)=2.34, p=.025. There was a trend for the two groups to continue to diverge during the maintenance phase, where the group × week effect within the maintenance phase was significant at the p=.053 level, X²(9)=16.7. At study end-point, 55% of the paroxetine group (vs 27% of the placebo group) were treatment responders, as defined by a CGI improvement score of 1 or 2.

The efficacy of paroxetine in this study sample was further supported by additional measures. For both LSAS Fear and LSAS Avoidance subscale scores, the paroxetine group had significantly greater reductions than the placebo group, both p values < .05. On average, the paroxetine group had a 52% reduction (placebo=30%) and 55% reduction (placebo=35%) from baseline on the LSAS Fear and Avoidance subscales, respectively. The SPIN results were in the same direction, but failed to achieve statistical significance. The paroxetine group showed a mean reduction of 46% (SE=7) and the placebo group had a mean reduction of 31% (SE=7), t(40)=1.49, p=.15.

Additionally, at the end of the 16-week study, subjects completed a treatment satisfaction questionnaire. Subjects rated along a 5-point Likert type scale their level of agreement to the statement “The medication I received was helpful in controlling my social anxiety,” where 1=strongly disagree and 5=strongly agree. The paroxetine group had a significantly higher agreement rating (M=3.95, SD=0.78) than the placebo group (M=2.95, SD=1.35), p < .01. Treatment groups did not differ (p >.10) in their satisfaction ratings regarding the general level of care they received in the project; on a 1 to 10 scale (where 1= totally dissatisfied and 10=totally satisfied), the mean satisfaction rating was 8.8 (SD=1.4).

3. Discussion

While there is considerable evidence that paroxetine is an effective treatment of social anxiety disorder (Baldwin et al., 1999; Liebowitz et al., 2005; Stein et al., 1998), clinical trials on paroxetine have typically excluded individuals with additional disorders. Since such disorders, including alcohol use disorders, are common in this population (Kessler, Chiu, Demler & Walters, 2005; Kushner, Abrams & Borchardt, 2000; Magee et al., 1996), results from clinical trials of paroxetine—with strict exclusion criteria for co-occurring disorders—have limited generalizability to clinical practice. The present study offers the first evidence that paroxetine can be safely and effectively used in socially anxious individuals with a comorbid alcohol use disorder.

The efficacy of paroxetine in the present study is similar to what has been reported from studies excluding individuals with co-occurring alcohol use disorders. For example, at week 16, the paroxetine group had over a 50% reduction of baseline severity on the LSAS (vs 32% for placebo); this effect is comparable to that reported by Stein and colleagues, where the paroxetine group decreased their total LSAS score by about 40% (vs. 17% with placebo) (Stein et al., 1998). In the present study, over half of the paroxetine group (57%) were rated as responders on the CGI, which was twice the rate of responders in the placebo group (27%). Baldwin and colleagues (Baldwin et al., 1999) and Liebowitz and colleagues (Liebowitz et al., 2005) each found that approximately 65% of subjects on paroxetine were treatment responders on the CGI as compared to approximately 35% of subjects on placebo. Comparing the results of the present study to these previous trials indicates that the presence of a co-occurring alcohol use disorder does not appear to interfere with the efficacy of paroxetine for the treatment of social anxiety disorder. Although the drinking outcomes from this trial are not a focus of this paper and will be presented in their entirety separately, the general finding has relevance to interpretation of these results related to social anxiety. That is, since drinking outcomes did not change from baseline through end of treatment for either those subjects randomized to paroxetine nor those randomized to placebo, there is no evidence that either a) the improvement in social anxiety severity seen in this study could be a consequence of changing alcohol use severity, or that b) paroxetine could be worsening alcohol use severity while it improves social anxiety severity.

There has been some debate regarding the diagnosis of mood and anxiety disorders in substance abusers. Some have suggested that in the face of alcohol dependence, a primary anxiety disorder can only be distinguished from a substance-induced anxiety disorder after the subject has been abstinent from alcohol for at least three weeks (Brown, Irwin & Schuckit, 1991). In 98% of our sample (ie, all but one subject), social anxiety disorder preceded the alcohol use disorder, and on average, social anxiety disorder preceded the onset of the alcohol disorder by almost a decade. The recommendation of three weeks of abstinence, then, has less relevance for our particular sample, but may still be relevant for other types of anxiety or psychiatric disorders that often co-occur with alcohol dependence.

There are several limitations of the present study that should be considered in interpreting the results. The study sample was modest and predominantly comprised of relatively young Caucasian adults, and all participants had mild to moderate alcohol use disorders. It is unclear whether paroxetine would be an effective or safe medication in individuals with alcohol-induced liver damage, or in socially anxious alcoholics with more presenting comorbidity. It is not clear why the prevalence of additional anxiety and mood disorders was lower in this study than expected from epidemiological studies (Kessler et al., 1998; Merikangas et al., 1995), since comorbidity was encouraged, rather than excluded in the study protocol. One possible explanation is that our exclusion criteria related to current use of psychotropic medication excluded individuals with depression or anxiety severe enough to require treatment. Also, because we were careful to exclude symptoms of mood and anxiety that were secondary to alcohol use (i.e., substance-induced), this may have translated into more conservative application of the SCID criteria, as compared to other clinical samples of individuals with social anxiety disorder. As such, the current results are limited to socially anxious alcoholics without significant additional psychiatric comorbidity but with significant and hazardous alcohol use.

In summary, evidence-based recommendations are lacking for the treatment of anxiety in the presence of a co-occurring substance abuse disorder, in general, and for social anxiety disorder and alcoholism in particular. The results of this clinical trial in socially anxious alcoholics demonstrated that paroxetine is a safe and effective treatment for social anxiety. As such, this study provides the first evidence-based recommendation for the use of an SSRI in this patient population. More research is needed to determine if these results and recommendations related to individuals seeking treatment for social anxiety who present with co-occurring alcohol problems can be generalized to persons presenting for social anxiety treatment with co-occurring drug abuse or dependence, to other FDA-approved medications for the treatment of social anxiety, and to other treatment modalities for social anxiety (e.g. behavioral therapies).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants R01 AA013379 (CLR), K24 AA013314 (CLR), P50 AA010761, and K23 AA014430 (SWB) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors thank GlaxoSmithKline for providing medication. The authors would also like to thank the following individuals for their contribution to various aspects of the trial: Dr. Maureen Carrigan, Dr. Angelica Thevos, Dr. Hugh Myrick, Dr. Robert Malcolm, Dr. Darlene Moak, Ms. Jennifer Nemcic, and Ms. Glenna Worsham for clinical services, Ms. Shannon Byrdic Anderson for outstanding project coordination, and Ms. Shannon de Viviés, and Mr. Steven Guterman for their valuable technical assistance.

Footnotes

A standard drink contains 1 oz. of absolute alcohol and is the equivalent of 12 oz. beer, 5 oz. wine or 1.5 oz. hard liquor.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Text Revision: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baker SL, Heinrichs N, Kim HJ, Hofmann SG. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale as a self-report instrument: a preliminary psychometric analysis. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2002;40:701–715. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin D, Bobes J, Stein DJ, Scharwaechter I, Faure M. Paroxetine in social phobia/social anxiety disorder: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;175:120–126. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition, Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace and Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Irwin M, Schuckit MA. Changes in anxiety among abstinent male alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:55–61. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns L, Teesson M. Alcohol use disorders comorbid with anxiety, depression and drug use disorders - Findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well Being. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68:299–307. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier MJ, Walker JR, Stein MB. Considering comorbidity in social phobia. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38:728–734. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0720-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Davidson JR, Sutherland S, Weisler R. Social phobia: issues in assessment and management. Epilepsia. 1999;40:S60–S65. S73–S74. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Davidson JR, Churchill LE, Sherwood A, Foa E, Weisler R. Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;176:379–386. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbert PM, King A, Rapp SR, Brief D, Martin JE, Lake M. Riboflavin as a tracer of medication compliance. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1985;8:287–299. doi: 10.1007/BF00870315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders - Patient Edition. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blanco C, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Dawson DA, Smith S, Saha TD, Huang B. The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:1351–1361. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: DHEC; 1976. pp. 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Horner KJ, Juster HR, Safren SA, Brown EJ, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. Psychometric properties of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:199–212. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert JD. An overview of the current status of social phobia. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 1995;4:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Stein MB, Berglund P. Social phobia subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:613–619. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:149–171. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y. Comorbidity in social anxiety disorder: Impact on disease burden and management. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–173. doi: 10.1159/000414022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR, Gelenberg AJ, Munjack D. Venlafaxine extended release vs placebo and paroxetine in social anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:190–198. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee WJ, Eaton WW, Wittchen HU, McGonagle KA, Kessler RC. Agoraphobia, simple phobia, and social phobia in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:159–168. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830020077009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannuzza S, Schneier FR, Chapman TF, Liebowitz MR, Klein DF, Fyer AJ. Generalized social phobia: Reliability and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:230–237. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950150062011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Angst J. Comorbidity and social phobia: Evidence from clinical, epidemiologic, and genetic studies. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1995;244:297–303. doi: 10.1007/BF02190407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, Rychtarik RG. In: Motivational Enhancement Therapy Manual. Mattson ME, editor. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Lecrubier Y, Baldwin D, Kasper S, Lader M, Nil R, Stein DJ, van Ree JM. ECNP Consensus Meeting, March 2003. Guidelines for the investigation of efficacy in social anxiety disorder. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;14:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris EP, Stewart SH, Ham LS. The relationship between social anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorders: A Critical Review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:734–760. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakman J, Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Farvolden P. A confirmatory factor analysis of a self-report version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:149–161. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall CL, Johnson MR, Thevos AK, Sonne SC, Thomas SE, Willard SL, Brady KT, Davidson JR. Paroxetine for social anxiety and alcohol use in dual-diagnosed patients. Depression & Anxiety. 2001;14:255–262. doi: 10.1002/da.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF. Treatment of social phobia and comorbid disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1995;56:380–383. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Horn JL. Alcohol Dependence Scale: Users Guide. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Ipser JC, Van Balkom AJ. Pharmacotherapy for social anxiety disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Article # CD001206), Issue 3. 2006 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001206.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Liebowitz MR, Lydiard RB, Pitts CD, Bushnell W, Gergel I. Paroxetine treatment of generalized social phobia (social anxiety disorder): A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:708–713. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.8.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;12:70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SE, Randall CL, Willard SL, Johnson MR. Importance of assessing drinking to cope in individuals with social anxiety disorder. Atlanta, GA: Anxiety Disorders Association of America Meeting; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Styan G, Donison D. Relationship of social phobia with other psychiatric illness. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1991;21:93–99. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90055-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Hunter SB, Burnam MA, Pincus HA, Nicholson G. Review of treatment recommendations for persons with a co-occurring affective or anxiety and substance use disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:913–926. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Beloch E. The impact of social phobia on quality of life. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;11 Suppl 3:15–23. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Fehm L. Epidemiology, patterns of comorbidity, and associated disabilities of social phobia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2001;24:617–641. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaider TI, Heimberg RG, Fresco DM, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. Evaluation of the clinical global impression scale among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:611–622. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]