Abstract

Objective

To assess the short-term economic savings associated with the prevention of unintended pregnancies through California's Medicaid family planning demonstration project.

Data Sources

Secondary data from health and social service programs available to pregnant or parenting women at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level in California in 2002 and data on the quantity and type of contraceptives dispensed to clients of California's 1115 Federal Medicaid demonstration project.

Study Design

The cost of providing publicly funded family planning services was compared with an estimate of public savings resulting from the prevention of unintended pregnancies.

Data Collection

To estimate costs and participation rates in each health and social service program, we examined published program reports, government budgetary data, analyses conducted by federal and state level program managers, and calculations from national datasets.

Findings

The unintended pregnancies averted by California's family planning demonstration project in 2002 would have incurred $1.1 billion in public expenditures within 2 years and $2.2 billion within 5 years, significantly more than the $403.8 million spent on the project. Each dollar spent generated savings of $2.76 within 2 years and $5.33 within 5 years.

Conclusions

The California 1115 Medicaid family planning demonstration project resulted in significant public cost savings. The cost of the project was substantially less than the public sector health and social service costs which would have occurred in its absence.

Keywords: Cost analysis, family planning, state-level demonstration projects, Medicaid

Medicaid, the United States' largest health program and source of federal support to states, contributed $770 million toward family planning services in 2001, making it the single largest source of public dollars for family planning services nationwide (Sonfield and Gold 2005). Although family planning services comprise < 1 percent of Medicaid expenditures, Medicaid plays a significant role in providing access to reproductive health care for low-income women and men (Guttmacher Institute 2005).

Over the past decade, 24 states, including California, have obtained federal approval for Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) research and demonstration project waivers under Section 1115 of the Social Security Act (Guttmacher Institute 2006). These waivers allow states to extend eligibility for family planning services to individuals ineligible for Medicaid because their incomes exceed eligibility limits or they fail to meet other requirements, such as having a dependent minor.

In California, women between 100 and 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) are largely ineligible for the state's Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, which has an income limit of 100 percent of the FPL for nonpregnant women. Women under 100 percent of the FPL may not qualify for Medi-Cal if they have no dependents or do not meet citizenship requirements. However, once pregnant, all uninsured women at or below 200 percent of the FPL qualify for prenatal, delivery, and postpartum care.

Recognizing a growing need for access to family planning services among low-income individuals, California's Department of Health Services, Office of Family Planning expanded access through the Family PACT Program in 1996. It was funded solely by California until 1999, when the Health Care Financing Administration, now CMS, granted federal funding to the program through an 1115 Medicaid demonstration project waiver.

The Family PACT Program has several distinguishing features: it covers family planning services for uninsured women, men, and adolescents at or below 200 percent of the FPL; providers are reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis; both public sector and private for-profit providers may offer services; patients may enroll at the point of service; and both clinics and pharmacies serve as distribution sites for over-the-counter and prescription drugs (California Department of Health Services Office of Family Planning 2004). Covered services include all FDA-approved contraceptive methods, sterilization, HIV testing, screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections, and limited cancer screening and infertility services. In its first full year, Fiscal Year (FY) 1997–1998, 750,000 men and women received services, averting an estimated 108,000 unintended pregnancies and 50,000 births (Foster et al. 2004). In 2002, Family PACT served over 1.4 million women and men, averting an estimated 205,000 pregnancies and 94,000 births (Foster et al. 2006).

This study compares the cost of providing Family PACT services to an estimate of the public sector costs which would have been incurred to support the unintended pregnancies and births that would have occurred in the absence of Family PACT. Several factors merit such an analysis.

First, the unique delivery model and growth of the Family PACT Program since its implementation have increased access to family planning services in California, and it is important to assess the costs and benefits of this expansion. Second, the overhaul of national welfare policy in 1996, which introduced time limits on many social service benefits and limited the ability of low-income women to access many services after childbirth, may have reduced the potential cost savings of providing family planning services.

Third, previous cost savings models potentially over-estimate the costs of public services associated with unintended pregnancies by not accounting for whether pregnancies are prevented or merely delayed. Prevention of unwanted pregnancies saves governments the total sum of associated health and social service costs. However, for unintended pregnancies delayed by family planning services and for which the public sector will experience the costs later, governments only save the difference between paying for the pregnancy now versus later. This study adjusts the estimated cost savings to account for the lower financial return expected from delayed rather than prevented unintended pregnancies.

This study is of interest to policy makers, program managers, and other stakeholders concerned with making appropriate, cost-effective investments in health and human services, particularly at a time of limited federal and state resources.

BACKGROUND

The most common approach to measure the cost of unintended pregnancy has been to estimate the 1-year cost of medical care, welfare, and other social services to support families begun as a result of an adolescent birth. A recent review of this literature concluded that in every study—whether national, state, or local in scope—the fiscal impact of adolescent pregnancies exceeded the costs of preventing them (Leigh 2003a, b).

Few studies have focused on the cost savings of specific interventions and few consider the costs incurred by adult pregnancies. Two studies that included adolescents and adults found that for every dollar spent to provide and/or expand Medicaid eligibility for contraceptive services, between $2.25 and $3.00 is saved nationally in pregnancy-related and newborn health care costs (Forrest and Samara 1996; Frost, Sonfield, and Gold 2006).

Several state-level studies have examined the savings associated with preventing pregnancies to adolescents and adults. In an evaluation of six states with federal family planning waivers, not only were the programs budget-neutral—that is, spending under the waiver did not exceed what spending would have been without the waiver—but also resulted in substantial savings (Edwards, Bronstein, and Adams 2003). Studies based on California in 1990, 1995, and 1998 demonstrated that a reduction in unintended pregnancy was linked to significant savings in health and social service expenditures, with cost savings ratios ranging from $3 to $7 within 2 years (Forrest and Singh 1991; Brindis and Korenbrot 1995; Darney and Brindis 2000).

The present analysis examines California's Family PACT Program in 2002. It is unique from past studies in that it: (1) focuses on the cost savings of a state-funded program since obtaining a Medicaid family planning waiver postwelfare reform, (2) calculates public savings for both adult and adolescent women, (3) accounts not only for pregnancy-related costs but also short-term medical, income support, and social service costs, (4) accounts for the probabilities that women and children would actually qualify for and utilize public services, and (5) accounts for the fact that the provision of contraceptives delays, rather than altogether prevents, some pregnancies. The two latter points, in particular, have the potential to result in a more conservative estimate of cost savings than calculated in any previous analyses.

DATA AND METHODS

This study assessed the short-term public cost savings associated with the prevention of unintended pregnancies through California's Medicaid family planning demonstration project. Cost savings were calculated for 2 and 5 years following an unintended pregnancy. Costs were limited to the monetary expenditures associated with health and social service programs; social costs and benefits such as productivity or quality of life were not included.

This analysis relies on three inputs: (1) total Family PACT Program costs, (2) the number of unintended pregnancies averted, and (3) the public sector cost each pregnancy would have incurred. The cost savings associated with Family PACT were calculated in 2002 U.S. dollars and expressed as a ratio of savings per dollar invested:

Program Cost

Based on Family PACT claims data, the total cost of services in Calendar Year (CY) 2002 was $403.8 million, which includes clinician, pharmacy, and laboratory services for both male and female clients. As most clients use a range of clinical services, not just contraceptives, the total cost of all services is included in this analysis. The intent is to determine whether the cost savings associated with the prevention of pregnancies alone outweigh the costs of the entire program.

Pregnancies Averted

The number of pregnancies averted by Family PACT is the difference between the number of pregnancies experienced by program participants and the number expected in the program's absence. A Markov model was designed to predict the probability of pregnancy under the contraceptive method mix of women before and after enrolling in the program. These estimates were derived separately for adolescents (ages 15–19) and adults (ages 20–44) (Foster et al. 2006).

We estimated the number of pregnancies expected among Family PACT clients based on typical use failure rates (Hatcher et al. 1998) for the contraceptive methods actually dispensed in 2002 as recorded in Family PACT claims data. The study population included all 926,218 women who received contraceptives through Family PACT in CY 2002. Over half (57 percent) of the months of contraceptive protection came from oral contraceptives, 19 percent from condoms, and 20 percent from injectable contraceptives. Adolescents were less likely to receive long-term methods and more likely to receive oral contraceptives and condoms. We estimate that 25,000 unintended pregnancies would occur to program participants despite the contraceptives provided—6,000 among adolescents and 19,000 among adults.

In the absence of Family PACT, we assumed women would continue using the methods they used before enrollment, according to self-reported contraceptive use at program entry collected from a review of 866 medical charts. Charts were randomly selected from Family PACT providers who were randomly selected from 11 California counties representative of the state. Before enrollment in Family PACT, over one quarter of women used no contraception, over one-third used condoms, and one in five were using the pill. Adolescents were more likely than adults to be using condoms and less likely to be using hormonal contraceptives at the time of enrollment. Under this method mix, it is estimated that 230,000 unintended pregnancies would have occurred—50,000 among adolescents and 180,000 among adults.

Based on pre-enrollment versus postenrollment contraceptive method mix, it is estimated that Family PACT averted an estimated 205,000 pregnancies. Of these, 79 percent were averted to adults, and 21 percent to adolescents. Given the national data on the outcomes of unintended pregnancy (Henshaw 1998), we expect the pregnancies would have resulted in 94,000 births, 78,600 abortions, 30,300 miscarriages, and 2,100 ectopic pregnancies (Foster et al. 2006).

Public Sector Costs of Unintended Pregnancy

Low-income pregnant women qualify for several public programs, which provide free or low-cost services before and after delivery for themselves and their children. As women enrolled in Family PACT have incomes below 200 percent of the FPL, they qualify for many of these public programs when they get pregnant or give birth. Table 2 lists the programs included in this analysis. The financial cost to society depends on each program's cost per enrollee, eligibility requirements, and actual participation levels. Eligibility is generally based on income, family size, age, citizenship status, and need (i.e., children born with serious medical conditions).

Table 2.

Data Inputs and the Calculated Cost Savings from Pregnancies Averted by the Family PACT Program, Calendar Year 2002

| Inputs | Effect of Adjustments on Final Public Cost (Conception to Age 2) | Effect of Adjustments on Final Public Cost (Conception to Age 5) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Annual Cost per Service per Enrollee | Probability of Pregnancy Outcome (%) | % of Family PACT Clients Eligible | % Eligibles Assumed to Seek Services | Estimated # of Years Receiving Services | Unit Cost per Pregnancy | Final Adjusted Cost per Pregnancy | Total Public Costs from Conception to Age 2, in Millions of Dollars | Unit Cost per Pregnancy | Final Adjusted Cost per Pregnancy | Total Public Costs from Conception to Age 5, in Millions of Dollars | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Pregnancy services | |||||||||||

| Miscarriage | $406 | 15 | 100 | 100 | 1.0 | $60 | $34 | $7.1 | $60 | $34 | $7.1 |

| Ectopic pregnancy | $1,016 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 1.0 | $10 | $6 | $1.2 | $10 | $6 | $1.2 |

| Abortion | $364 | 38 | 100 | 100 | 1.0 | $140 | $79 | $16.4 | $140 | $79 | $16.4 |

| Prenatal care | $2,561 | 46 | 100 | 98 | 1.0 | $1,151 | $653 | $135.9 | $1,151 | $653 | $135.9 |

| Delivery | $3,200 | 46 | 100 | 100 | 1.0 | $1,468 | $832 | $168.3 | $1,468 | $832 | $168.3 |

| Total pregnancy services | $2,828 | $1,604 | $328.9 | $2,828 | $1,604 | $328.9 | |||||

| Other health care | |||||||||||

| Mother, Medi-Cal postpartum care | $251 | 46 | 100 | 100 | 1.0 | $115 | $65 | $13.2 | $115 | $63 | $13.2 |

| Mother, Full scope Medi-Cal, year 0–1 | $753 | 46 | 39 | 100 | 1.0 | $132 | $74 | $16.2 | $132 | $72 | $16.2 |

| Mother, Full scope Medi-Cal, year 1+ | $1,937 | 46 | 39 | 100 | 4.0 | $341 | $192 | $40.5 | $1,362 | $747 | $155.2 |

| Infant, Full scope Medi-Cal, year 0–1 | $2,496 | 46 | 100 | 100 | 1.0 | $1,145 | $645 | $131.2 | $1,145 | $627 | $131.2 |

| Infant, Full scope Medi-Cal, year 1+ | $611 | 46 | 97 | 97 | 4.0 | $263 | $148 | $29.3 | $1,054 | $578 | $112.3 |

| Infant, Healthy Families, year 1+ | $1,031 | 46 | 3 | 68 | 4.0 | $10 | $5 | $1.1 | $39 | $21 | $4.1 |

| Total health care | $2,005 | $1,129 | $231.5 | $3,846 | $2,108 | $432.2 | |||||

| Income support | |||||||||||

| Cal-WORKs grants—Mother | $2,255 | 46 | 39 | 39 | 2.0 | $309 | $174 | $37.3 | $309 | $171 | $37.3 |

| Cal-WORKs grants—Child | $2,255 | 46 | 65 | 100 | 2.0 | $1,344 | $759 | $151.9 | $1,344 | $745 | $151.9 |

| Cal-WORKs employment services | $609 | 46 | 39 | 39 | 1.0 | $42 | $24 | $5.0 | $42 | $23 | $5.0 |

| Cal-WORKs pregnancy payment | $282 | 46 | 39 | 39 | 1.0 | $19 | $11 | $2.4 | $19 | $11 | $2.4 |

| Food Stamps | $2,028 | 46 | 60 | 47 | 5.0 | $515 | $291 | $62.3 | $1,289 | $714 | $149.0 |

| WIC—Mother | $570 | 46 | 100 | 90 | 1.5 | $353 | $199 | $40.8 | $353 | $196 | $40.8 |

| WIC—Child | $463 | 46 | 100 | 90 | 5.0 | $382 | $216 | $43.2 | $956 | $530 | $103.4 |

| Total income support | $2,965 | $1,673 | $343.0 | $4,311 | $2,390 | $489.9 | |||||

| Social services | |||||||||||

| Child care—Cal-WORKS Stage 1 | $6,097 | 46 | 60 | 22 | 2.0 | $725 | $460 | $87.7 | $725 | $383 | $87.7 |

| Child Care—CA Dept. Ed. | $4,297 | 46 | 100 | 22 | 3.0 | $0 | $0 | – | $1,300 | $687 | $136.5 |

| State Preschool | $2,193 | 46 | 100 | 70 | 2.0 | $0 | $0 | – | $1,408 | $743 | $145.6 |

| Foster care | $17,797 | 46 | 100 | 1 | 1.5 | $122 | $78 | $13.9 | $122 | $65 | $13.9 |

| Early Head Start (age 0–2) | $8,121 | 46 | 86 | 3 | 2.0 | $192 | $122 | $21.7 | $192 | $101 | $21.7 |

| Head Start (age 3) | $8,121 | 46 | 86 | 32 | 1.0 | $0 | $0 | – | $1,025 | $541 | $107.5 |

| Head Start (age 4) | $8,121 | 46 | 86 | 84 | 1.0 | $0 | $0 | – | $2,690 | $1,421 | $274.1 |

| Cal-Learn (adolescents) | $2,673 | 49 | 13 | 100 | 2.0 | $334 | $212 | $53.2 | $334 | $176 | $53.2 |

| Cal-SAFE (adolescents) | $4,335 | 49 | 13 | 10 | 2.0 | $63 | $40 | $10.0 | $63 | $33 | $10.0 |

| Adolescent Family Life Program (adolescents) | $1,306 | 49 | 13 | 15 | 1.0 | $14 | $9 | $2.3 | $14 | $8 | $2.3 |

| Total social services | $1,451 | $921 | $188.8 | $7,875 | $4,158 | $852.5 | |||||

| Children with special needs | |||||||||||

| California Children's Services | $373 | 46 | 100 | 1.0 | 5.0 | $3 | $2 | $0.4 | $9 | $5 | $0.9 |

| Early Start—LEAs/SELPAs | $12,742 | 46 | 100 | 0.4 | 5.0 | $43 | $24 | $4.9 | $108 | $57 | $11.7 |

| Early Start—Regional centers | $6,527 | 46 | 100 | 1.4 | 5.0 | $84 | $46 | $9.5 | $210 | $111 | $22.7 |

| Supplemental security income | $6,899 | 46 | 100 | 0.9 | 5.0 | $57 | $31 | $6.4 | $142 | $75 | $15.4 |

| Total special services | $187 | $103 | $21.2 | $469 | $247 | $50.7 | |||||

| Total | $9,437 | $5,431 | $1,113 | $19,329 | $10,508 | $2,154 | |||||

Notes:

(1) Costs collected from published program reports, government budgetary data, analyses conducted by federal- and state-level program managers, and calculations from national datasets.

(2) Based on Henshaw's (1998) age-specific estimates of the outcomes of unintended pregnancies, a weighted average is presented based on the proportion of adults and adolescents in the Family PACT Program. Non-pregnancy-related costs are derived only for those pregnancies expected to result in live births; the rate is higher for Cal-Learn, Cal-SAFE, and AFLP because these programs are limited to adolescents, who have a higher rate of live birth than adults.

(3) Estimated proportion of Family PACT clients eligible for each program on the basis of income, family size, age, and citizenship status after becoming pregnant or giving birth.

(4) For pregnancy services, the percentage of the eligible population that uses Medi-Cal to pay for services is presented. For all other program costs, an estimate of utilization among eligibles is presented, either from program reports or derived from total program enrollment divided by the population in the qualifying income and age bracket according to the Census or Current Population Survey.

(5) An estimate of how many years on average participants utilize the program is presented, up to a cap of five years for the purposes of this study.

(6) Product of average cost per enrollee, pregnancy outcome, % of clients eligible, and duration of services, in two and five year intervals. Services may begin at conception, birth, or later.

(7) The final adjusted cost-per-pregnancy was adjusted for whether costs would have been delayed or entirely prevented by family planning services, with future costs discounted at a 3% rate.

(8) The total public cost was the final adjusted cost-per-pregnancy multiplied by the number of pregnancies averted.

Columns may not add to totals due to rounding.

To estimate costs and participation rates in each program, we used published program reports, budgetary data, data analyses conducted by federal- and state-level program managers, and calculations from national data sets. We considered the proportionate federal, state, and local contributions to the funding of each public program in order to quantify the savings expected by each government sector.

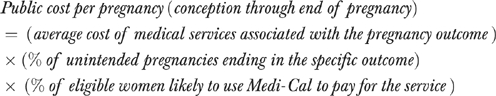

Medical Costs through the End of Pregnancy

The largest source of pregnancy-related medical care to low-income women in California is Medi-Cal, California's Medicaid program. Medi-Cal costs incurred during pregnancy depend on the pregnancy outcome, but may include prenatal obstetric care and medical care for miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, induced abortion, or delivery. The formula used to calculate the average public sector cost per unintended pregnancy through the end of the pregnancy was the following, summed across the possible pregnancy outcomes, and calculated separately for adolescents and adults:

|

For each pregnancy outcome, the average cost of medical services was obtained from the California Medi-Cal Program. Cost estimates represent the average amount reimbursed for each service, including expenditures for related medical complications. For instance, the cost of delivery is a weighted average of cesarean and vaginal births. The cost of live birth includes prenatal, labor, and delivery services. Costs were adjusted by the likelihood that an unintended pregnancy would end in a particular outcome requiring that service. Among women under 20, it was estimated that 14 percent of pregnancies ended in spontaneous abortion/miscarriage, 1 percent in ectopic pregnancy, 36 percent in abortion, and 49 percent in birth. The distribution for women older than 20 was estimated at 15, 1, 39, and 45 percent, respectively (Henshaw 1998; Foster et al. 2006).

As all women in Family PACT are uninsured and would qualify for Medi-Cal once pregnant, we assumed that 100 percent of patients would use Medi-Cal for their health care in the event of a pregnancy. This assumption is based on the fact that women who are not enrolled in Medi-Cal for pregnancy-related care but deliver in a hospital are retroactively signed up, regardless of citizenship status. The remaining deliveries are covered through disproportionate share payments to the hospital, which covers uncompensated care and are administered by the Medi-Cal program. Based on 2002 California birth data, we assumed 98 percent would have at least one prenatal care visit (Ficenec, Bindra, and Christensen 2004).

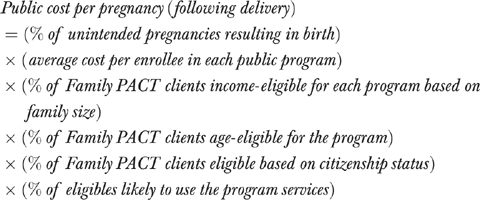

Medical and Social Service Costs after Birth

In addition to Medi-Cal, women at or below 200 percent of the FPL and their children can qualify for other public services during or following birth: medical services, income support, social services, services for children with special needs, and services for pregnant or parenting adolescents. For women whose pregnancies were projected to lead to a live birth, we estimated medical and social service costs for mother and child from birth to age 2 and to age 5. Two years is a common time limit for public programs. Costs up to 5 years were also modeled because even when mothers are no longer eligible for many programs after 2 years, their children continue to be, thus we modeled costs up to the time when the child would typically enter school.

The formula used to calculate the average public sector cost per unintended pregnancy for medical and social services rendered to women at or below 200 percent of the FPL and their newborns following delivery was the following, summed across the public programs considered in this study:

|

Forty-nine percent of adolescent and 45 percent of adult pregnancies were assumed to result in live births. Thus, nearly half the women who would have become pregnant in the absence of the Family PACT Program would have potentially been eligible to use public services after birth.

The cost of program participation per enrollee was based on each program's FY 2002–2003 budgetary data. When FY 2002–2003 data were unavailable, costs were adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (Smith 2003). Only the costs of direct services, not administrative services, were included.

The per-participant costs were adjusted for the probability that a Family PACT client would qualify for each program on the basis of its income, age, and citizenship status requirements. Eligibility of Family PACT clients for these programs was estimated from demographic data (e.g., income, family size, age) from the Family PACT client eligibility form. As various programs limit eligibility to citizens or legal residents, an estimate of the proportion of Family PACT clients who are undocumented was derived using data from a medical record review conducted in FY 2000–2001. The percent of native-born women with a missing Social Security Number (SSN) was compared with the percent of foreign-born women with a missing SSN. It was assumed that all native-born women are citizens and any missing SSN data was missing at random; any proportion of missing SSN data above that level among foreign-born women was assumed to reflect the proportion that are not citizens.

An adjustment was also made for the proportion of eligibles who would actually participate in each program. When available, this was estimated using actual program utilization rates among women at or below 200 percent of the FPL as calculated by the specific programs. These estimates were usually not available for adults and adolescents separately, so averages were used. When utilization estimates were unavailable, they were estimated as the ratio of total enrollment (according to each program) to the number of individuals in the qualifying income and age bracket (according to Current Population Survey data for the year for which enrollment data were available). For instance, for children with special health care needs, the total enrollment in each program was divided by the number of children in the qualifying income and age groups according to the Census or Current Population Survey.

Calculating Timing of Costs

The yearly cost of services in each program was multiplied by the average length of enrollment. Program time limits were taken into consideration and conservative estimates of how long a mother and/or child would participate in each program were made based on published reports and analyses conducted by program managers. Although programs may experience future budget cuts or enrollment caps, for the purpose of this analysis, we assumed that expenditures, eligibility, and participation levels in a program were constant over time.

To estimate the timing of savings, we used the distribution of pregnancies averted by month, as estimated by Foster et al. (2006). Most of the services and programs used by pregnant women would have been accessed in the year the pregnancy occurred. For expenditures expected to occur after 2002, a 3 percent discount rate was applied. For instance, mothers and children become eligible for Medi-Cal immediately following birth, but would not qualify for Head Start until the child is older. Also, depending on when in 2002 a woman obtained contraceptives and what method she received, an averted pregnancy could have otherwise ended in birth anytime from late 2002 to early 2004. Thus, projections followed children born as early as 2002 and as late as 2004 up to their second and fifth birthdays.

Adjustment for Delayed versus Prevented Pregnancy Costs

Finally, an adjustment was made to the total cost-per-pregnancy to account for whether pregnancies were prevented versus delayed. Governments save the entire cost for pregnancies which are: (1) unwanted, and thus entirely prevented by family planning services, and (2) mistimed but delayed until a woman can improve her economic condition so she no longer requires public aid. However, for pregnancies (3) merely delayed by family planning but for which the state will still incur the costs later, the state only saves the difference between paying for the pregnancy now versus later.

In this study, all pregnancies are assumed to be unintended because they would have occurred to women receiving contraceptives through the state family planning program. To estimate the proportion of pregnancies unwanted versus mistimed, questions on reproductive intentions were included in representative Family PACT client interviews of 1,142 women between November 2003 and March 2004. Respondents indicated whether they would like a/another child and if so, when. The proportion of unintended pregnancies assumed to be prevented was based on the percentage of women who did not want a/another child (33 percent of adults and 6 percent of adolescents). The remaining pregnancies (67 percent of adults and 94 percent of adolescents) were assumed to be merely delayed by use of contraceptives.

Adult women who did want future children wanted to wait an average of 4.3 years and adolescents an average of 7 years. By preventing a pregnancy until then, it is estimated that 60 percent of adults and 25 percent of adolescents would improve their economic status and no longer need public aid; the remaining women would still have needed public services. The likelihood that a woman would still need public benefits even after delaying her pregnancy was based on the percentage of women who used Medi-Cal to pay for delivery among the age groups 4.3 and 7 years greater than the age profiles of Family PACT clients in 2002, using data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth (Abma et al. 1997).

To summarize our adjustment for delayed versus prevented costs, we assume that the public saves the entire cost of 50 percent of adult pregnancies and 62 percent of adolescent pregnancies, which is the sum of the percentage of pregnancies which are unwanted and the percentage which are delayed but are not expected to incur public costs in the future (Table 1). For the remaining pregnancies, that is, those delayed by family planning services, the public savings amounts only to the difference between paying for services now versus 4.3 years (adults) or 7 years (adolescents) later.

Table 1.

Derivation of the Adjustment for Delayed and Prevented Pregnancies

| Adults | Adolescents | |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Unwanted pregnancies:% of clients who do not want a/another child now or ever (source: client interviews) | 33 | 6 |

| (b) Mistimed pregnancies:% of clients who do not want a/another child now but do want one sometime in the future (100%−a) | 67 | 94 |

| (c) % of women who would no longer need public services if pregnancy was delayed into the future (source: 1995 NSFG) | 25 | 60 |

| (d) % of women who do want a/another child someday and would no longer need public services if that pregnancy were delayed into the future (b × c) | 17 | 56 |

| (e) % of costs prevented by family planning services (a+d) | 50 | 62 |

RESULTS

Table 2 lists the per-pregnancy and total cost savings resulting from pregnancies averted to adults and adolescents for each public program for they may qualify. Before adjusting for whether costs were prevented versus merely delayed, the cost-per-pregnancy was $9,437 ($8,460 for adults, $14,836 for adolescents) to age 2. The cost-per-pregnancy to age 5 was $19,329 ($18,300 for adults, $24,174 for adolescents).

Applying the adjustment, each averted pregnancy saved the public $5,431 in medical, welfare, and other social service costs for a woman and child from conception up to 2 years after a pregnancy ($4,675 for adults, $8,228 for adolescents). Given the number of pregnancies averted and their likely outcomes, the estimated total cost savings of the unintended pregnancies averted by Family PACT in 2002 was over $1.1 billion up to age 2 ($754 million for adults, $359 million for adolescents). Costs saved up to 5 years after a pregnancy were $10,508 per averted pregnancy ($9,338 for adults, $14,838 for adolescents), for a total of $2.2 billion ($1.5 billion for adults, $647 million for adolescents). By reducing public health and welfare expenditures resulting from unintended pregnancies, every dollar invested in Family PACT saved the public sector $2.76 within 2 years and $5.33 within 5 years after conception (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cost Savings Associated with the California Family PACT Program, 2002

| Pregnancies averted to female clients | 205,000 |

| Average public cost per pregnancy | |

| To age 2 | $5,431 |

| To age 5 | $10,508 |

| Cost savings from averting pregnancies | |

| To age 2 | $1,113,298,960 |

| To age 5 | $2,154,140,876 |

| Cost of Family PACT services | $403,834,000 |

| Cost savings ratio | |

| To age 2 | $2.76 |

| To age 5 | $5.33 |

Table 4 describes the share of cost savings on a number of population and program characteristics. From conception to age 2, pregnancy-related medical care and income support make up the largest portion (29.5 and 30.8 percent, respectively). To age 5, social services, such as subsidized child care or preschool, make up the largest portion (39.6 percent). Considering federal, state, and local contributions to the funding of each program, the share of the cost savings is 62 percent federal, 37 percent state, and 1 percent local, resulting in savings of $690 million federally, $412 million to the state, and $11 million locally. To age 5, the share of cost savings is 65 percent federal, 34 percent state, and 1 percent local, for totals of $1.4 billion federally, $740 million to the state, and $10 million locally.

Table 4.

Costs Saved by Population and Program Characteristics, California Family PACT Program, 2002

| Conception to Age 2 | Conception to Age 5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Adolescents (ages 15–19) | $358,920,678 | 32.2% | $647,247,029 | 30% |

| Adults (ages 20–44) | $754,378,282 | 67.8% | $1,506,893,847 | 70.0% |

| Service Type | ||||

| Pregnancy-related medical care | $328,886,816 | 29.5% | $328,886,816 | 15.3% |

| Other medical care | $231,522,815 | 20.8% | $432,168,679 | 20.1% |

| Income support | $342,952,099 | 30.8% | $489,907,811 | 22.7% |

| Social services | $188,759,701 | 17.0% | $852,491,174 | 39.6% |

| Children with special needs | $21,177,529 | 1.9% | $50,686,396 | 2.4% |

| Payer | ||||

| Federal | $689,751,033 | 62.0% | $1,404,315,106 | 65.2% |

| State | $412,779,979 | 37.0% | $739,593,964 | 34.3% |

| Local | $10,767,948 | 1.0% | $10,231,806 | 0.5% |

| Total costs saved | $1,113,298,960 | 100.0% | $2,154,140,876 | 100.0% |

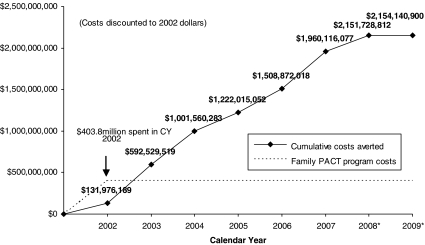

Figure 1 shows the cost savings accrued over time. The expenditure of $403.8 million for family planning services in 2002 yielded savings of $593 million within a year.

Figure 1.

Cumulative Public Sector Expenditures Saved over Time Resulting from Family PACT Services Delivered in Calendar Year 2002*

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses examined the effect of various assumptions on the cost savings ratios. For each data point, a range of possible values was used based on published data. Alternate assumptions about program costs and participation estimates resulted in a cost savings ratio range from $2.53–2.86 to age 2, and $5.06–5.59 to age 5, < 10 percent difference in either direction.

The sensitivity of the cost savings ratio to the range of estimates of averted pregnancies was also modeled. Under the most likely alternate scenarios of contraceptive failure rates and clients' contraceptive behavior in the absence of Family PACT as modeled in Foster et al. (2006), the range of pregnancies averted is between 199,400 and 247,500, yielding a ratio of $2.68–3.33 saved within 2 years and $5.19–6.44 saved within 5 years for each dollar invested in the program. Thus, the cost savings ratios calculated in this study, $2.76 and $5.33 within two and 5 years, respectively, could be 3 percent lower or 21 percent higher than we estimated.

CONCLUSIONS

Through the provision of effective methods of contraception to low-income individuals who have limited access to these services elsewhere, California's family planning program averted an estimated 205,000 unintended pregnancies, averting nearly 94,000 live births and 79,000 abortions (Foster et al. 2006). The program saved federal, state, and local governments over $1.1 billion within 2 years after a pregnancy and $2.2 billion up to 5 years after. By reducing public heath and welfare expenditures resulting from unintended pregnancies, every dollar spent on Family PACT saved the public sector $2.76 up to 2 years and $5.33 up to 5 years after a pregnancy.

DISCUSSION

Compared with other cost analyses of family planning services, this analysis presents a conservative estimate. Previous studies have potentially over-estimated the public savings associated with unintended pregnancies by assuming that all pregnancies averted are entirely prevented, rather than merely delayed into the future. By assuming that only a portion of the costs of delayed pregnancies is actually saved, the effect of this adjustment in this study was to reduce the cost savings estimate by over 40 percent.

Another way this study acted conservatively was it considered Family PACT's entire budget rather than only the costs of its contraceptive services. Although Family PACT may also have positive economic impact through its sexually transmitted infection screening and treatment and detection of cervical and breast cancer, this study suggests that the cost savings attributed to the provision of contraceptive services alone outweighs the entire cost of the program. Had this study compared the costs of providing contraceptive services only versus the costs incurred in Family PACT's absence, the cost savings ratio would have been higher. Furthermore, this study did not quantify benefits such as increased productivity or quality of life.

The Family PACT Program did not gather detailed information on program participants' actual participation levels in public programs. Also, the program utilization estimates were derived from those of the general population of eligible women in California; it is unknown whether women with unintended births would have the same level of program utilization as women with intended births.

Despite the conservative methodological approaches taken in this study, the financial consequences of unintended pregnancy far outweigh the cost of prevention. Almost half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, and in California, even with significant efforts to expand access to publicly funded family planning services, unmet need is still high: nearly one of five women at risk of an unintended pregnancy is not using a method of contraception (Foster et al. 2004). Together, these trends signal the need to sustain and continue to expand access to existing programs. Given the growing ranks of uninsured women and men of reproductive age, the cost savings associated with programs like Family PACT warrants continued and expanded financial investments in family planning programs either through Medicaid waivers or other public sources of funding.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the California State Department of Health Services, Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health Branch (MCAH), Office of Family Planning (OFP), through a contract to the UCSF Bixby Center for Reproductive Health Research & Policy, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Health Sciences, Institute for Health Policy Studies, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco. We gratefully acknowledge the staff for its support of this evaluation, especially Susann Steinberg, M.D., MCAH Branch Chief, and Ms. Laurie Weaver, OFP Chief.

Disclosures: None

Disclaimers: None

Footnotes

Depending on when a woman received Family PACT services and how many months of contraceptive coverage she received, these projections follow children that would have been born as early as 2002 or late as 2004 up to their fifth birthdays.

REFERENCES

- Abma JC, Chandra A, Mosher WD, Peterson LS, Piccinino LJ. Fertility, Family Planning, and Women's Health: New Data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Statistics. 1997;23(19):1–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindis CD, Korenbrot CC. The Cost-Effectiveness of Family Planning Expenditures for Contraceptive Services in the State of California. San Francisco: University of California, Center for Reproductive Health Research & Policy; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Health Services Office of Family Planning. 2004. “Family PACT: An Overview” [accessed on May 24, 2005]. Available at http://www.dhs.ca.gov/pcfh/ofp/Documents/PDF/FamPact/FPoverview.pdf.

- Darney P, Brindis C. Evaluation of the California Family PACT Program, Report to the California State Legislature. San Francisco: University of California; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Bronstein J, Adams K. Evaluation of Medicaid Family Planning Demonstrations. Alexandria, VA: CNA Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ficenec S, Bindra K, Christensen J. Vital Statistics of California 2002. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Statistics; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest JD, Samara R. Impact of Publicly Funded Contraceptive Services of Unintended Pregnancies and Implications for Medicaid Expenditures. Family Planning Perspectives. 1996;28(5):188–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest JD, Singh S. The Impact of Public-Sector Expenditures for Contraceptive Services in California. Family Planning Perspectives. 1991;22(4):161–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DG, Biggs MA, Amaral G, Brindis C, Navarro S, Bradsberry M, Stewart F. Estimates of Pregnancies Averted through California's Family Planning Waiver Program in 2002. Perspectives for Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38(3):126–31. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.126.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DG, Bley J, Mikanda J, Induni M, Arons A, Baumrind N, Darney PD, Stewart FH. Contraceptive Use and Risk of Unintended Pregnancy in California. Contraception. 2004;70(1):31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DG, Klaisle CM, Blum M, Bradsberry ME, Brindis CD, Stewart FH. Expanded State-Funded Family Planning Services: Estimating Pregnancies Averted in California, 1997–98. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;19(8):1341–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost JJ, Sonfield A, Gold RB. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2006. Estimating the Impact of Expanding Medicaid Eligibility for Family Planning Services. Occasional Report No. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute. 2005. “Medicaid: A Critical Source of Support for Family Planning in the United States, Issue Brief” [accessed on May 1, 2005]. Available at http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/medicaid-IB-Gold.pdf.

- Guttmacher Institute. 2006. “State Medicaid Family Planning Eligibility Expansions, State Policies in Brief” [accessed on November 15, 2006]. Available at http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_SMFPE.pdf.

- Hatcher R, et al., editors. Contraceptive Technology. 17. New York: Ardent Media; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw SK. Unintended Pregnancy in the United States. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30(1):24–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh WA. National Costs of Teen Pregnancy and Teen Pregnancy Prevention: What We Know. Washington, DC: Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies; 2003a. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh WA. State/Local Costs of Teen Pregnancy and Teen Pregnancy Prevention: What We Know. Washington, DC: Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies; 2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. “Frequently Asked Health Economics Questions.” Menlo Park, CA: Health Economic Resource Center, Department of Veterans Affairs [accessed December 15, 2003]. Available at http://www.herc.research.med.va.gov/FAQ_A3.htm.

- Sonfield A, Gold RB. Public Funding for Contraceptive, Sterilization and Abortion Services, FY 1980–2001. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]