Abstract

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is associated with preterm labor, pelvic inflammatory disease and increased HIV acquisition, although the pathways that mediate these pathological effects have not been elucidated. To determine the presence of toll-like receptor (TLR)-ligands and their specificity in BV, genital tract fluids were collected from women with and without BV by cervicovaginal lavage (CVL). The CVL samples were evaluated for their ability to stimulate secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and to activate NF κB and the HIV long terminal repeat (LTR), indicators of TLR activation, in human monocytic cells. Stimulation with BV CVLs induced higher levels of IL-8 and TNFα secretion, as well as higher levels of HIV LTR and NF κB activation, than CVLs from women with normal healthy bacterial flora. To identify which TLRs were important in BV, 293 cells expressing specific TLRs were exposed to CVL samples. BV CVLs induced higher IL-8 secretion by cells expressing TLR2 than CVLs from women without BV. Surprisingly, BV CVLs did not stimulate cells expressing TLR4/MD2, although these cells responded to purified LPS, a TLR4 ligand. BV CVLs, in cells expressing TLR2, also activated the HIV LTR. Thus, these studies show that soluble factor(s) present in the lower genital tract of women with BV activate cells via TLR2, identifying a pathway through which BV may mediate adverse effects.

Keywords: Bacterial vaginosis, Toll-like receptor, HIV LTR, vaginal flora, pelvic inflammatory disease, macrophage

1. Introduction

Bacterial vaginosis (BV), which represents an alteration in the normal vaginal microflora, can have a prevalence as high as 40% in some groups of women of reproductive age (Sobel, 2000; Yen et al., 2003). Although BV is not considered a sexually transmitted disease, sexual activity is a risk factor for the development of this condition. The etiology of BV is polymicrobial in nature.

In normal vaginal flora, lactobacilli such as L. vaginalis L. jensenii and L. crispatus are present (Antonio et al., 1999; Fredricks et al., 2005; Verhelst et al., 2005). In BV, lactobacilli are decreased while bacteria that are normally low or undetectable become predominant. BV-related organisms include Atopobium, Streptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella, Porphyromonas and clostridium-like species (Fredricks et al., 2005; Verhelst et al., 2005; Verstraelen et al., 2004). Increased levels of Mycoplasma hominis and Gardnerella vaginalis, which are present in some non-BV-affected women, also occur (Sha et al., 2005; Demba et al., 2005; Briselden and Hillier, 1990). Recently, several types of previously unknown bacteria have also been detected in the BV microbiota by 16S rDNA cloning (Fredricks et al., 2005).

BV is associated with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and preterm births (PTB) (Hillier et al., 1996; Klebanoff et al., 2005; Leitich et al., 2003; Ness et al., 2005). Additionally, epidemiological studies have associated BV with an increase in HIV acquisition (Martin et al., 1999; Sewankambo et al., 1997; Taha et al., 1998). The biological mechanism by which these pathological effects are mediated is unknown. However, we have observed previously that both BV-derived bacteria and soluble factors present in the cervicovaginal lavages (CVLs) of women with BV induced HIV expression in myeloid and T cell lines (Olinger et al., 1999; Al-Harthi et al., 1999). This activation required the presence of the κB cis-acting element within the HIV long terminal repeat (LTR), the viral promoter (Al-Harthi et al., 1998). Hence, given the polymicrobial nature of BV, we hypothesized that bacterial recognition pathways, such as toll-like receptors (TLRs), play a role in BV-CVL-induced HIV LTR activation.

TLR4 and TLR2 bind several bacterial ligands. TLR4, along with MD-2, recognizes lipopolysaccharide (LPS). While TLR2, in conjunction with either TLR1 or TLR6, binds tri- and di-acetylated lipopeptides, respectively, although recognition of lipopeptides can occur independently of TLR1 and TLR6 (Buwitt-Beckmann et al., 2006). TLR2, in conjunction with CD14, recognizes lipoteichioc acid (LTA) and the fimbriae of Porphyromonas gingivalis (Asai et al., 2001; Dziarski et al., 1998; Hajishengallis et al., 2005; Hermann et al., 2002). Stimulation via TLR2 and TLR4 results in TNFα and IL-8 secretion, as well as the activation of NF κB which binds to the κB cis-acting element.

Myeloid cells, which express TLR2 and TLR4, play an important role in the recognition of and immune response to microbes. Within the reproductive tract, myeloid cells are present and produce inflammatory mediators in response to microbial stimuli (Morrison 2000; Pioli 2006). Furthermore, myeloid cells are increased in the reproductive tract of women with endometritis, a form of PID (Sukhikh et al., 2006). These cells have been reported also to be present in the placental bed in PTB (Kim et al., 2006). Moreover, this cell type is increased in the reproductive tract of HIV-positive women and is a primary target of HIV infection (Ahmed et al., 2001). Thus, myeloid cells appear to be common among PID, PTB and increased HIV acquisition.

In this study, we used THP-1 human monocytic cells to characterize the ability of CVLs obtained from women with normal flora (normal CVL) and BV to induce pro-inflammatory correlates of TLR signaling, i.e. NF κB activation, and secretion of TNFα and IL-8. To directly test the hypothesis that TLRs are involved in CVL-induced cell stimulation, we analyzed the roles of TLR2 and TLR4/MD2 in BV-CVL-induced IL-8 secretion and TLR2 in HIV LTR activation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell lines and reagents

THP-1 human monocytic cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Cambrex). The TLR2/CD14, CD14, TLR4 or TLR4/MD2 293 cell lines, grown in DMEM (Cambrex) plus 10% FBS, were kind gifts from R.W. Finberg (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA) (Kurt-Jones et al., 2002; Latz et al., 2002). LPS and ultra-pure LPS derived from Escherichia coli subtype 0111:B4 were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and InvivoGen (San Diego, CA), respectively. In some experiments, LPS from Sigma was purified further using the Hirschfeld method (Hirschfeld et al., 2000, 2001). LTA derived from Staphylococcus aureus was from Sigma. TNFα was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

2.2. Study cohorts

Subjects were recruited from the Family Planning Outpatient Center of the Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP) in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Women with vaginal discharge and good general and gynecological health were included in the study. Women who were pregnant or were within two months of having had a delivery, abortion, or ectopic pregnancy were excluded from the study. Women who had used antibiotics within 7 days prior to enrollment or had a chronic disease were also excluded from the study. American CVLs were obtained from the Women’s HIV Interdisciplinary Network (WHIN). Women who were currently menstruating were excluded from both the Brazilian and American cohorts.

2.3. Sample collection and processing

CVLs were obtained from 40 Brazilian HIV-seronegative women giving informed consent using an IRB-approved protocol. CVLs were obtained by irrigating the cervix with 10ml sterile saline. Samples were processed within five hours of collection and were shipped overnight on dry ice. The CVLs were then clarified by centrifuging for 15 minutes at 14,000 rpm at 4°C. Aliquots were stored at −70°C.

Subjects were diagnosed as normal or BV according to the Nugent criteria at the Laboratory of Microbiology and Cytopathology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at UNICAMP (Nugent et al., 1991). An experienced microbiologist, who is responsible for all clinical laboratory work in the Laboratory of Microbiology and Cytopathology, performed the testing for trichomonas and candida at UNICAMP. Samples were tested for trichomonas by wet mount and Papanicolaou (pap) smears. The presence of candida was assessed by wet mount, Gram stain and pap smears. Results were considered positive if at least one of the assays was positive. The estimated sensitivity was approximately 85%–90%. Testing for gonorrhea and Chlamydia within the Brazilian cohort was performed at the clinical laboratories of Rush University Medical Center. The GEN-PROBE PACE 2C System (Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA) was used to test endocervical swabs for gonorrhea and chlamydia. The sensitivities of the assays are 92.6% for chlamydia and 95.4% for gonorrhea. All of the Brazilian samples were negative for trichomonas, gonorrhea, chlamydia and candida.

American CVLs were also collected by irrigating the vaginal tract with 10ml of saline. The BV status of the American cohort was determined using the Amsel criteria (Amsel et al., 1983). All subjects were HIV seronegative. Eleven BV CVLs and 11 CVLs from low-risk, BV-negative control subjects were obtained from WHIN. The latter group was comprised of women who were at low risk for acquiring HIV.

The American CVLs were assessed for the presence of trichomonas and candida by wet mount with a sensitivity of approximately 60%. A gynecologist with more than 10 years of experience analyzed the samples. The BD ProbeTec ET System (BD Diagnostic Systems, Franklin, NJ) was used to test for gonorrhea and chlamydia. The sensitivities for these assays are 96% and 90.7%, respectively. All of the American CVLs were negative for gonorrhea, chlamydia, candida and trichomonas.

2.4. Transfections and luciferase assays

THP-1 cells were co-transfected with 2µg of an NF κB-firefly luciferase reporter (Promega, Madison, WI) and 40ng of a Renilla-TK luciferase (RL) internal control plasmid (Promega) using 4µl TransIt Jurkat transfection reagent (Mirus, Madison, WI) asper the manufacturer’s instructions. All DNA was prepared using an endotoxin-free DNA plasmid preparation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and reconstituted in endotoxin-free water. At 18 hours after transfection, 2×105 transfected cells were stimulated with 10% (vol/vol) CVL or the indicated controls in triplicate for 6 hours in a final culture volume of 200µl per well in 96-well culture plates.

The luciferase assay was performed using a dual luciferase assay kit (Promega). Luciferase activity was measured using a Sirius luminometer (Zylux, Oak Ridge, TN). Data are expressed as the ratio of NF κB firefly luciferase activity to RL activity.

To determine HIV LTR activity, THP-1 cells were transfected with 2µg of an HIV LTR-luciferase reporter construct and 40ng of RL. At 15 hours after transfection, cells were re-plated for assay in triplicate using 10% CVL or the indicated controls. Transfected cells were harvested 24 hours after stimulation. The dual luciferase assay was performed as described above.

For the HIV LTR analyses in the 293-TLR2/CD14 and 293-CD14 cells, cells were simultaneously transfected and plated into a 96-well plate using 60µl of lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) with 24 µg HIV LTR luciferase construct and 480ng RL. At 24 hours after transfection, cells were stimulated with 5% CVL or controls for 6.5 hours. Luciferase activity was measured and analyzed as described above. Each CVL was tested in triplicate.

2.5. ELISAs

IL-8 and TNFα ELISAs were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Biosource, Camarillo, California).

2.6. Statistical analyses

InStat software (GraphPad, San Diego, California) was used to perform nonparametric analyses to compare the means of two groups (Mann-Whitney U) or to test for correlations (Spearman Rank Correlation). Where appropriate, an unpaired t test or one-sample t test was performed. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Subjects

In the Brazilian cohort, 17 had normal healthy bacterial flora and 23 had BV flora, as determined by Nugent scores of 0–3 and 7–10, respectively. The median age for the normal flora subjects was 29, with a range of 20 to 40 years of age. Three of the subjects were taking oral contraceptives, 10 were using intrauterine devices (IUDs) and four had received Depo-provera injections. The median age for the BV subjects was 32, with an age range of 18 to 49. Contraceptive use among the BV group included oral contraceptives (2), IUDs (15), Depo-provera (5) and condoms (1).

Of the subjects with normal flora, three had abnormal pap smears. Two were diagnosed with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS). One normal flora subject was diagnosed with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) III with atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. One BV subject was diagnosed with ASCUS, and another with CIN I with human papilloma virus.

3.2. Effect of BV CVLs on NF κB and HIV LTR activation and cytokine secretion

In BV, various genera of bacteria are present. Recognition of bacterial products via TLRs results in the activation of NF κB and HIV LTR and the induction of TNFα and IL-8 secretion. Hence, we analyzed these indicators as an initial assessment to test the hypothesis that bacterial recognition pathways are activated by BV CVLs. We tested the stimulatory capacity of CVLs using THP-1 human monocytic cells which express TLRs 1, 2, 4 and 6 (Zhang et al., 1999; Melmed et al., 2003).

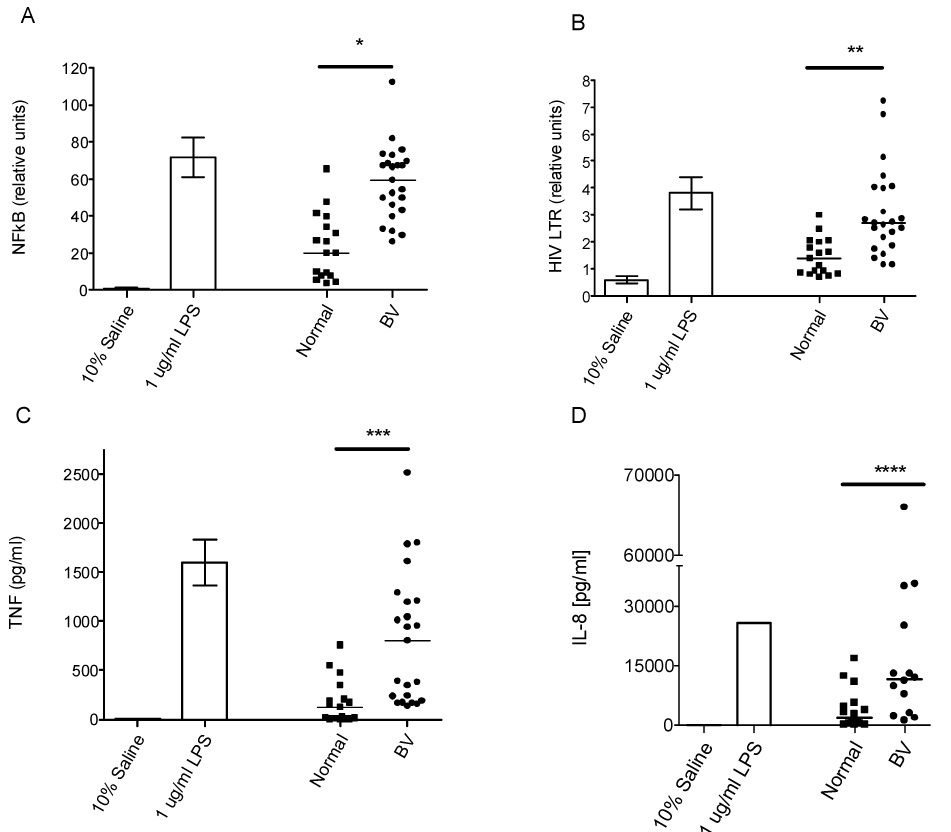

Stimulation of THP-1 cells with both normal flora CVLs and BV CVLs for 6 hours increased NF κB activation relative to the saline control, but BV CVLs (median 59.3 relative units, range=26–112 relative units) induced higher NF κB activation than normal CVLs (median 19.9 relative units, range=3.6–65 relative units) (p<0.0001, Mann-Whitney U; Figure 1A). As indicated in Figure 1B, treatment with 10% BV CVLs (median 2.7 relative units, range=1.2–7.2) for 24 hours resulted in higher levels (p=0.0015, Mann-Whitney U) of HIV LTR activation than treatment with 10% normal CVLs (median 1.4 relative units, range=0.71–3) in the THP-1 cells.

Figure 1. BV CVLs induce higher levels of NF κB activation, HIV LTR activation and cytokine secretion by THP-1 monocytic cells than normal CVLs.

A) THP-1 cells were co-transfected with an NF κB-luciferase reporter and a Renilla-TK (RL) internal control plasmid. At 18 hours post-transfection, cells were stimulated with CVL (10% of culture volume) and the indicated controls in triplicate for 6 hours. Data are expressed as relative units corresponding to the ratio of NF κB activity to RL. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U analysis: *p<.0001; BV=23, Normal=17 B) THP-1 cells were co-transfected with an HIV-LTR luciferase reporter and the RL internal control plasmid as in Figure 1A. Following a 24-hour stimulation with 10% CVL or the indicated controls, the cells were lysed and a dual luciferase assay was performed. Each CVL was tested in triplicate in two separate assays. The average of both experiments is shown. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U analysis: **p=.0015; BV=23, Normal=17 C) Culture supernatants from the HIV LTR experiment shown in Figure 1B were assayed for TNFα by ELISA. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U analysis: ***p=.0002; BV=23, Normal=17 D) The culture supernatants from the HIV LTR experiment shown in Figure 1B were analyzed for IL-8 by ELISA. The horizontal line within the experimental scatter plot represents the median. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U analyses: ****p=.0033; BV=14, Normal=16. IL-8 present within the CVL itself was measured by a flow cytometric cytokine multiplex assay and was subtracted from the total to determine the amount of induced IL-8. In all panels, the error bars represent the SEM. The horizontal lines within the experimental scatter plot denote the median. The dark horizontal lines above the scatter plots and below the asterisk or asterisks define the comparison groups that were used for the indicated statistical analysis.

Stimulation of THP-1 cells with normal CVLs induced 121pg/ml (median, range=0–757pg/ml) of TNFα, while treatment with BV CVLs induced a greater amount of TNFα (median 803pg/ml, range=139–2,514pg/ml, p=0.0002, Mann-Whitney U) (Figure 1C). The positive control, LPS, significantly increased TNFα secretion by THP-1 cells relative to saline (p<0.05, two-tailed, one sample t test) (Figure 1C). In other experiments, LTA increased TNFα secretion by THP-1 cells by 13-fold over the saline control (data not shown).

As indicated in Figure 1D, treatment of THP-1 cells with normal and BV CVLs induced a median IL-8 secretion of 1,964pg/ml (range=137–16,800 pg/ml) and 11,600pg/ml (range=1,248–66,000pg/ml), respectively. When compared to the normal CVLs, BV CVLs induced higher amounts of IL-8 secretion (p=0.0033, Mann-Whitney U). Thus, BV CVLs induced significant increases in TNFα (p=0.0002) and IL-8 secretion (p=0.0033), as well as in NF κB (p<0.0001) and HIV LTR activation (p=0.0015), relative to normal CVLs.

We analyzed correlations between NF κB, HIV LTR, TNFα and IL-8 using the Spearman rank correlation statistic. TNFα secretion correlated with both NF κB activation (r=0.8958, p<0.0001) and IL-8 secretion (r=0.7534, p<0.0001). HIV LTR activation was correlated also with CVL-induced TNFα (r=0.7552, p<0.0001) and IL-8 secretion (r=0.7239, p<0.001) and NF κB activation (r=0.795, p<0.0001). Thus, correlates of TLR activation are correlated also with CVL-induced HIV LTR activation.

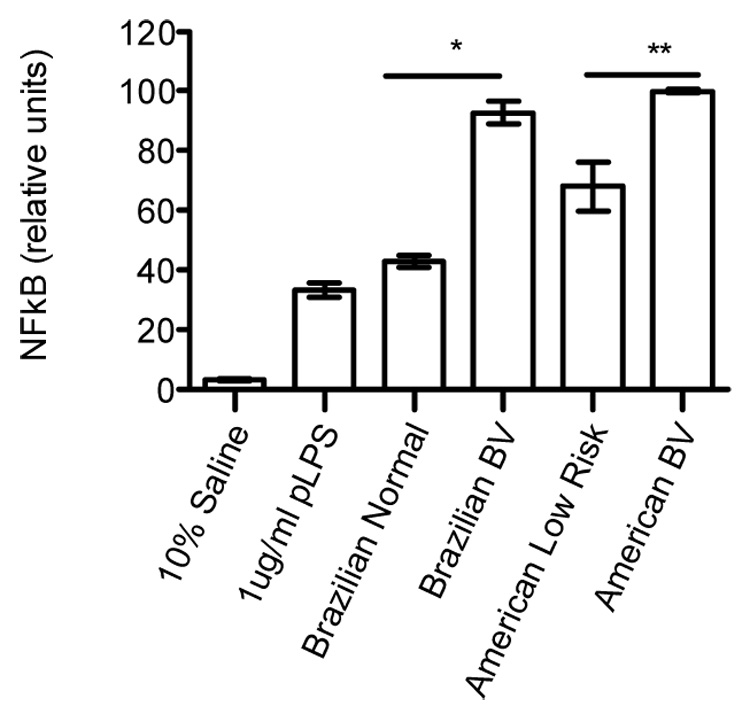

3.3. NF κB activation by both American and Brazilian BV CVLs

NF κB activation was assessed also for CVLs collected from American women. Pooled BV CVLs from American women (average 100 relative units) stimulated higher NF κB activity than the pooled American BV-negative, low-risk control (average 68 relative units) (p=0.0046, two-tailed, unpaired student t test; Figure 2). Pooled Brazilian BV CVLs (average 93 relative units), used as a control in this experiment, induced an approximate two-fold increase in NF κB activation relative to the pooled normal Brazilian control (43 relative units; Figure 2).

Figure 2. NF κB activation by both American and Brazilian BV CVLs.

Equal volumes of CVL from either the Brazilian or American cohorts were pooled and tested in an NF κB activation assay. THP-1 cells were transfected with the NF κB reporter and RL internal control plasmids and stimulated as in Figure 1A. Samples were tested in quadruplicate. One experiment representative of two is shown. Error bars represent the SD. Two-tailed Unpaired Student t test, *p<.0001, **p= .0046.

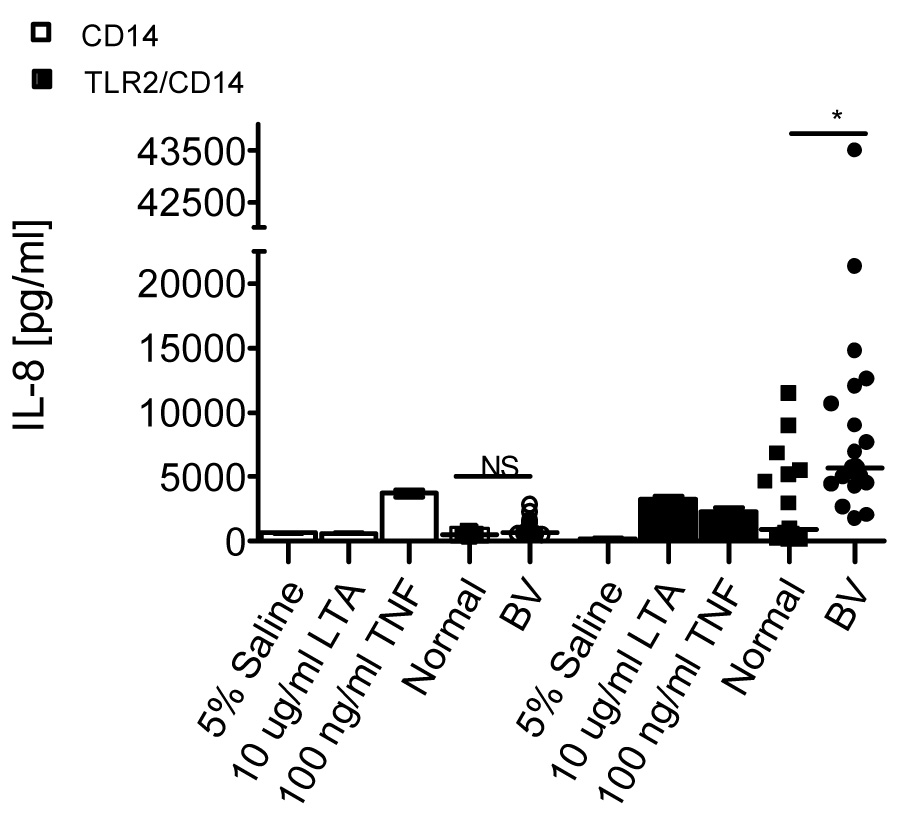

3.4. BV CVLs stimulate IL-8 production via TLR2

The data from the above THP-1 studies suggested that TLR signaling was involved in BV-CVL-mediated activation of NF κB and the HIV LTR. To test directly whether BV CVLs could stimulate via TLRs, 293 cells that stably expressed TLR2/CD14 (293-TLR2/CD14) or TLR4/MD2 (293-TLR4/MD2) were exposed to CVLs and IL-8 secretion measured. As a negative control, 293 cells that stably expressed either CD14 alone (293-CD14) or TLR4 alone (293-TLR4) were also exposed to CVLs.

Neither normal nor BV CVLs stimulated IL-8 secretion by the 293-CD14 cells. In contrast, both normal and BV CVLs induced IL-8 secretion by the 293-TLR2/CD14 cells at levels higher than the saline control. However, BV CVLs (median 5,713pg/ml, range=1,755– 43,497pg/ml) induced significantly higher IL-8 secretion by the 293-TLR2/CD14 cells than the normal CVLs (median 914pg/ml, range=136-11,486pg/ml) (p=0.0043, Mann-Whitney U; Figure 3).

Figure 3. BV CVLs stimulate IL-8 secretion via TLR2.

293 cells stably expressing CD14 (open symbols) or TLR2/CD14 (closed symbols) were stimulated with 5% CVL or the indicated controls in triplicate for 24 hours. Supernatants were analyzed for IL-8 secretion by ELISA as in Figure 1D. Error bars represent the SEM. The horizontal line within the scatter dot plot represents the median. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U analyses: *p= .0043; N.S.= not significant, p>.05; BV=21; Normal=15

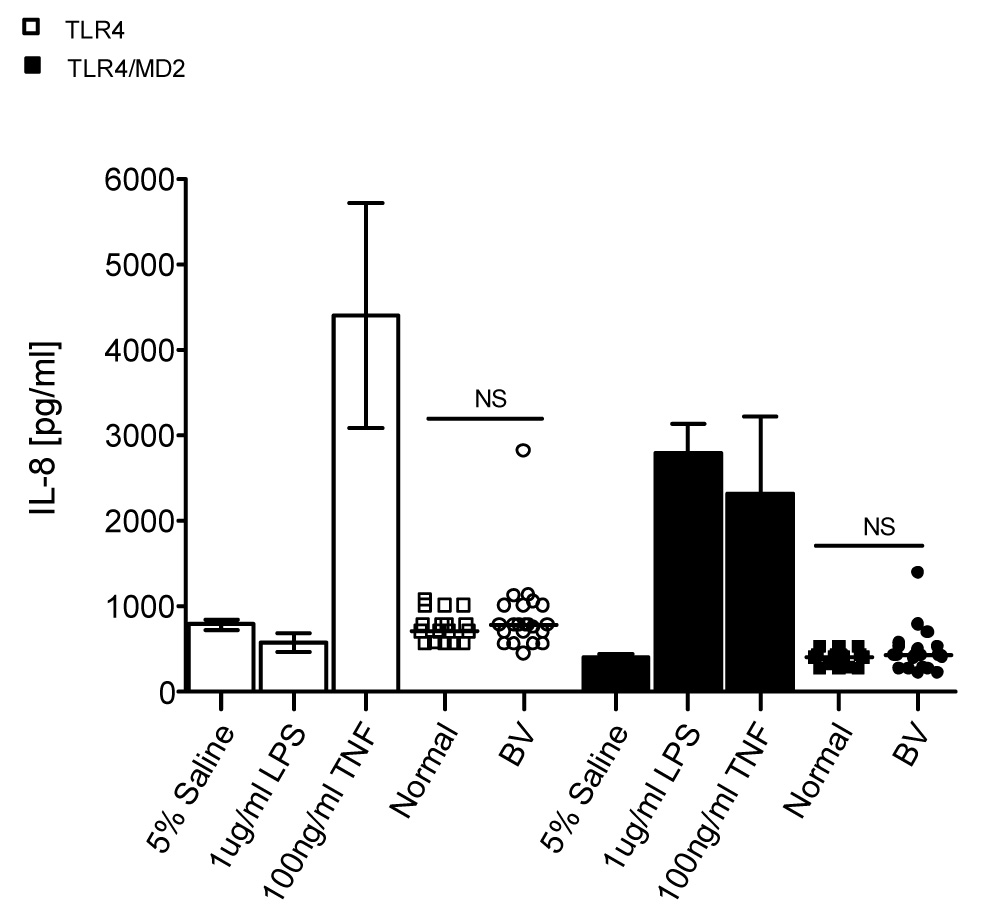

The 293-TLR4/MD2 and 293-TLR4 cells were also treated with CVLs. Compared to saline, neither normal nor BV CVLs stimulated IL-8 secretion by the 293-TLR4 cells (p>0.05 for both, two-tailed one sample t test; Figure 4). Similarly, neither normal nor BV CVLs stimulated IL-8 secretion by the 293-TLR4/MD2 cells above background (p>0.05, two-tailed one sample t test).

Figure 4. BV CVLs do not stimulate IL-8 secretion via TLR4/MD2.

293 cells stably expressing TLR4 (open symbols) or TLR4/MD2 (closed symbols) were stimulated with 5% CVL or the indicated controls in triplicate for 24 hours. Supernatants were analyzed for IL-8 secretion as in Figure 1D. Each CVL was tested in two separate experiments. The average of the two experiments is shown. Error bars represent the SEM. The horizontal line within the scatter dot plot represents the median. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U analyses: N.S.= not significant (p>.05); BV=23; Normal=17

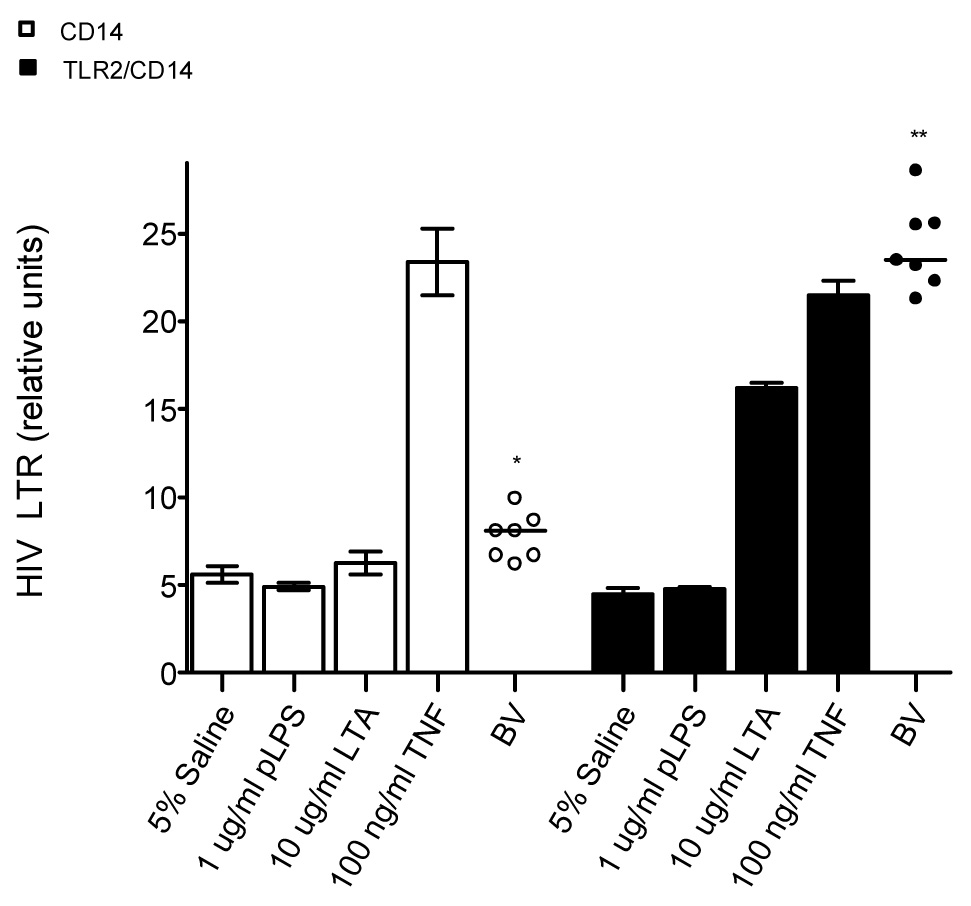

3.5. BV CVLs induce HIV LTR activation via TLR2

Since the above experiments showed that BV CVLs stimulate via TLR2, we determined further whether BV CVLs could induce HIV LTR activation through TLR2. For these experiments, we selected BV CVLs that exhibited medium to high IL-8 secretion by the 293-TLR2/CD14 and HIV LTR activation relative to the saline controls. BV CVLs (7.8 average relative units; Figure 5) induced slightly higher (two-tailed one-sample t test, p=0.0049) HIV LTR activation in the 293-CD14 cells than saline (5.6 average relative units). However, BV CVLs (24.3 average relative units) induced significantly higher (one-sample t test, p<0.0001) TLR2-mediated HIV LTR activation than the saline control (4.5 relative units). Furthermore, when normalized to saline, BV CVLs induced higher amounts of HIV LTR activation in the 293-TLR2/CD14 cell line (unpaired t test with Welch correction, p<0.0001) than in the 293-CD14 cell line. Moreover, the ability of the CVLs to induce TLR2-mediated IL-8 secretion (Figure 3) and TLR2-mediated-HIV LTR activation (Figure 5) were significantly correlated (r=0.734, p=0.0008, Spearman rank correlation).

Figure 5. BV CVLs induce HIV LTR activation via TLR2.

293 cells stably expressing CD14 (open symbols) or TLR2/CD14 (closed symbols) were co-transfected with an HIV LTR luciferase reporter and the RL plasmid. The cells were stimulated with 5% CVL or the indicated controls for 6.5 hours. HIV LTR activity was normalized to the RL internal control. Each CVL was tested in triplicate. Error bars represent the SEM. The horizontal line represents the mean. Two-tailed one sample t test analyses: *p=.005 (compared to saline control), **p<.0001 (compared to saline control).

4. Discussion

To understand the biological mechanisms by which BV contributes to an increase in HIV acquisition and other pathogenic effects, we tested the hypothesis that bacterial recognition pathways play a role in BV-mediated HIV LTR activation, cytokine secretion and NF κB activation. We demonstrated that BV CVLs induce higher levels of NF κB and HIV LTR activation in THP-1 human monocytic cells than CVLs from women with normal healthy flora. We have demonstrated also that TNFα and IL-8 secretion by BV-CVL-treated THP-1 cells is higher than normal-CVL-treated cells. Thus, BV CVLs have a greater stimulatory effect on THP-1 cells than normal CVLs. We have demonstrated further that BV CVLs induce TLR2-mediated IL-8 secretion and HIV LTR activation. The ability of mucosal fluids collected from women with BV to stimulate via TLR2 and to induce TLR2-mediated HIV LTR activation has not been previously reported.

The greater stimulatory effect of BV CVLs, when compared to normal CVLs, could have several explanations including increased total numbers of bacteria in BV and/or the presence of different types of bacteria in BV. However, it should be noted that it is also possible that the greater stimulatory effect of BV CVLs could be due, in part, to increased total genital secretions by women with BV.

In our study, two of the 40 CVLs, both of which were BV-positive, stimulated TLR4/MD2-mediated IL-8 secretion without stimulating cytokine secretion in 293-TLR4 cells, suggesting that these samples contain a TLR4/MD2 ligand. One CVL also induced IL-8 secretion in the 293-TLR4, 293-TLR4/MD2 and 293-CD14 cell lines, suggesting the possibility that the CVL contained a factor that could stimulate independently of TLRs. However, the magnitude of IL-8 secretion by the 293-TLR2/CD14 relative to the 293-CD14 cell line indicates that this one CVL contains also a TLR2 ligand. Hence, while BV CVLs induce higher amounts of TLR2-mediated IL-8 secretion than normal CVLs, neither group of CVLs induce IL-8 secretion by the 293-TLR4/MD2 cells. Thus, our data suggest that TLR2 ligands are present at a greater concentration than TLR4/MD2 ligands in BV CVLs.

The overall inability of the CVL samples to stimulate the negative control cells indicates that the receptor for the stimulatory factor(s) is not present on 293 cells. Neissera gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trichomatis and Candida, the respective etiological agents of gonorrhea, chlamydia and candidiasis, can stimulate cells via TLR2 (Fisette et al., 2003; Deva et al., 2003; Darville et al., 2003). The stimulatory capacity of either normal or BV CVLs is not attributable to these agents since all subjects were negative for these infections. Thus, the ability of some of the normal CVLs to stimulate via TLR2, to induce TNFα secretion, and to activate NF κB and the HIV LTR indicates the presence of a TLR2 ligand in a portion of normal CVLs that is not attributable to the above-mentioned conditions.

The stimulatory capacity of these CVLs may be a reflection of specific differences in normal vaginal flora, which is comprised of several species of lactobacilli (Antonio et al., 1999). In support of this hypothesis, Klebanoff et al. (1999) have shown that L. crispatus, which is present in the normal vaginal flora, induces TNFα secretion and activation of NF κB and the HIV LTR.

Our results suggest that bacterial ligand(s) present in the vaginal tract can stimulate via TLR2. Given the polymicrobial nature of BV, we cannot attribute the stimulatory effects of the CVLs to a specific bacterium or specific bacterial product. However, taken together, our previous observation that the HIV-LTR-inducing activity present in BV CVLs is protease-sensitive as well as the current demonstration that BV CVLs induce HIV LTR activation via TLR2 suggest that at least one of the stimulatory factors present in BV CVLs is either a lipopeptide or a glycoprotein (Spear et al., 1997). Although the TLR2/CD14 cell line experiments demonstrate that BV CVLs stimulate via TLR2, the role of CD14 in this stimulation has not been directly addressed by our studies.

In conclusion, we observed that soluble factor(s) present in the CVLs of women with BV stimulate cells via TLR2. More importantly, we found that soluble factor(s) present in the CVLs of women with BV induce TLR2-mediated HIV LTR activation. Taken together, our data raise the possibility that a TLR2 ligand present in the lower genital tract of women with BV contributes to the biological mechanism by which BV induces pathology and increases HIV acquisition.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Carolyne Gichinga for performing the flow cytometric cytokine multiplex assay. Financial support: NIH Grant P01HD40539

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmed SM, Al-Doujaily H, et al. Immunity in the female lower genital tract and the impact of HIV infection. Scand. J. Immunol. 2001;54(1–2):225–238. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Harthi L, Roebuck KA, et al. Bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora isolated from the female genital tract activates HIV-1 expression. J Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr. 1999;21:194–202. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199907010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Harthi L, Spear GT, et al. A human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-inducing factor from the female genital tract activates HIV-1 gene expression through the kappaB enhancer. J. Infect. Dis. 1998;178:1343–1351. doi: 10.1086/314444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsel R, Totten PA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am. J. Med. 1983;74:14–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonio MA, Hawes SE, et al. The identification of vaginal Lactobacillus species and the demographic and microbiologic characteristics of women colonized by these species. J. Infect. Dis. 1999;180:1950–1956. doi: 10.1086/315109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai Y, Ohyama Y, et al. Bacterial fimbriae and their peptides activate human gingival epithelial cells through Toll-like receptor 2. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:7387–7395. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7387-7395.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briselden AM, Hillier SL. Longitudinal study of the biotypes of Gardnerella vaginalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990;28:2761–2764. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2761-2764.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buwitt-Beckmann U, Heine H, et al. TLR1- and TLR6-independent recognition of bacterial lipopeptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:9049–9057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darville T, O'Neill JM, et al. Toll-like receptor-2, but not Toll-like receptor-4, is essential for development of oviduct pathology in chlamydial genital tract infection. J. Immunol. 2003;171:6187–6197. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demba E, Morison L, et al. Bacterial vaginosis, vaginal flora patterns and vaginal hygiene practices in patients presenting with vaginal discharge syndrome in The Gambia, west Africa. BMC Infect. Dis. 2005;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deva R, Shankaranarayanan P, et al. Candida albicans induces selectively transcriptional activation of cyclooxygenase-2 in HeLa cells: pivotal roles of Toll-like receptors, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, and NF-kappa. B. J. Immunol. 2003;171:3047–3055. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziarski R, Tapping RI, et al. Binding of bacterial peptidoglycan to CD14. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:8680–8690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisette PL, Ram S, et al. The Lip lipoprotein from Neisseria gonorrhoeae stimulates cytokine release and NF-kappaB activation in epithelial cells in a Toll-like receptor 2-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:46252–46260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks DN, Fiedler TL, et al. Molecular identification of bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1899–1911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Ratti P, et al. Peptide mapping of bacterial fimbrial epitopes interacting with pattern recognition receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:38902–38913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann C, Spreitzer I, et al. Cytokine induction by purified lipoteichoic acids from various bacterial species--role of LBP, sCD14, CD14 and failure to induce IL-12 and subsequent IFN-gamma release. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:541–551. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200202)32:2<541::AID-IMMU541>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier SL, Kiviat NB, et al. Role of bacterial vaginosis-associated microorganisms in endometritis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996;175:435–441. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld M, Ma Y, et al. Cutting edge: repurification of lipopolysaccharide eliminates signaling through both human and murine toll-like receptor 2. J. Immunol. 2000;165:618–622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld M, Weis JJ, et al. Signaling by toll-like receptor 2 and 4 agonists results in differential gene expression in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:1477–1482. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1477-1482.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Romero R, et al. Distribution of CD14+ and CD68+ Macrophages in the placental bed and basal plate of women with preeclampsia and preterm labor. Placenta. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff MA, Hillier SL, et al. Is bacterial vaginosis a stronger risk factor for preterm birth when it is diagnosed earlier in gestation? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;192:470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff SJ, Watts DH, et al. Lactobacilli and vaginal host defense: activation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat, cytokine production, and NF-kappaB. J. Infect. Dis. 1999;179:653–660. doi: 10.1086/314644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt-Jones EA, Mandell L, et al. Role of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) in neutrophil activation: GM-CSF enhances TLR2 expression and TLR2-mediated interleukin 8 responses in neutrophils. Blood. 2002;100:1860–1868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latz E, Visintin A, et al. Lipopolysaccharide rapidly traffics to and from the Golgi apparatus with the toll-like receptor 4-MD-2-CD14 complex in a process that is distinct from the initiation of signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:47834–47843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitich H, Bodner-Adler B, et al. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for preterm delivery: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;189:139–147. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin HL, Richardson BA, et al. Vaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisition. J. Infect. Dis. 1999;180:1863–1868. doi: 10.1086/315127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melmed G, Thomas LS, et al. Human intestinal epithelial cells are broadly unresponsive to Toll-like receptor 2-dependent bacterial ligands: implications for host-microbial interactions in the gut. J. Immunol. 2003;170:1406–1415. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness RB, Kip KE, et al. A cluster analysis of bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005;162:585–590. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent RP, Krohn MA, et al. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1991;29:297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olinger GG, Hashemi FB, et al. Association of indicators of bacterial vaginosis with a female genital tract factor that induces expression of HIV-1. AIDS. 1999;13:1905–1912. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewankambo N, Gray RH, et al. HIV-1 infection associated with abnormal vaginal flora morphology and bacterial vaginosis. Lancet. 1997;350:546–550. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)01063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha BE, Chen HY, et al. Utility of Amsel criteria, Nugent score, and quantitative PCR for Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, and Lactobacillus spp. for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:4607–4612. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4607-4612.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel JD. Bacterial vaginosis. Annu. Rev. Med. 2000;51:349–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear GT, al-Harthi L, et al. A potent activator of HIV-1 replication is present in the genital tract of a subset of HIV-1-infected and uninfected women. AIDS. 1997;11:1319–1326. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199711000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhikh GT, Shurshalina AV, et al. Immunomorphological characteristics of endometrium in women with chronic endometritis. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2006;141:104–106. doi: 10.1007/s10517-006-0105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha TE, Hoover DR, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and disturbances of vaginal flora: association with increased acquisition of HIV. AIDS. 1998;12:1699–1706. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhelst R, Verstraelen H, et al. Comparison between Gram stain and culture for the characterization of vaginal microflora: definition of a distinct grade that resembles grade I microflora and revised categorization of grade I microflora. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstraelen H, Verhelst R, et al. Culture-independent analysis of vaginal microflora: the unrecognized association of Atopobium vaginae with bacterial vaginosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;191:1130–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen S, Shafer MA, et al. Bacterial vaginosis in sexually experienced and nonsexually experienced young women entering the military. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;102:927–933. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00858-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang FX, Kirschning CJ, et al. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide activates nuclear factor-kappaB through interleukin-1 signaling mediators in cultured human dermal endothelial cells and mononuclear phagocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7611–7614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]