Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To measure community-level changes in the methods youth use to obtain cigarettes over time and to relate these methods to the progression of smoking.

METHODS

We analyzed 2000-2003 data from the Minnesota Adolescent Community Cohort study, where youth (beginning at age 12), who were living in Minnesota at baseline, were surveyed every six months via telephone. We conducted mixed model repeated measures logistic regression to obtain probabilities of cigarette access methods among past 30-day smokers (n = 340 at baseline).

RESULTS

The probability of obtaining cigarettes from a commercial source in the past month declined from 0.36 at baseline to 0.22 at the sixth survey point while the probability of obtaining cigarettes from a social source during the previous month increased from 0.54 to 0.76 (p for both trends = 0.0001). At the community level, the likelihood of adolescents obtaining cigarettes from social sources was inversely related to the likelihood of progressing to heavy smoking (p < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

During this time, youth shifted to greater reliance on social sources and less on commercial sources. A trend toward less commercial access to cigarettes accompanied by an increase in social access may translate to youth being less likely to progress to heavier smoking.

Keywords: Adolescence, Smoking, Cigarette use, Tobacco sales

Introduction

Through the mid-1990s, youth obtained cigarettes from commercial sources with relative ease in much of the United States, (MMWR, 1993, MMWR, 2002, Naum, et al., 1995, DiFranza and Brown, 1992, DHHS, 1994). The 1994 Surgeon General’s Report Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People examined 13 studies conducted between 1987 and 1993 and found an average over-the-counter purchase rate for minors of 67% (DHHS, 1994). In 1992, Congress passed the Synar Amendment which mandated that all states and territories prohibit the sale of tobacco to minors by 1994, and enforce the law or risk loss of federal funds for addressing chemical health issues (DHHS, 1995). Since the passage of Synar, research has shown that it has become more difficult for minors to purchase cigarettes. In 1998, 38 states reported a 20% or greater youth cigarette purchase rate, as measured by random test purchases. By 2003, only 6 states had a 20% or greater test purchase rate (CDC, 2005). Hawaii is an example of a state that saw a dramatic change; Glanz et al. reported a reduction in the successful purchase rate from 44.5% to 6.2% from 1996 to 2003 (Glanz, et al., 2007). In Minnesota, rates of cigarette sales to minors, again as measured by random test purchases, fell from 27.7% to 15.5% between 1998 and 2003 (CDC, 2005). However, despite the reported decreases in sales rates from Synar test purchases, adolescents who wish to purchase cigarettes use techniques that may differ than procedures used in test purchase, such as not choosing outlets at random, likely making actual purchase rate higher (Difranza, 2000).

Youth obtain cigarettes commercially (from a store or vending machine) and socially (borrowing, buying, or stealing from other youth or adults). Research has shown that how youth obtain cigarettes may be related to how heavily they smoke. The 1999 National Youth Tobacco Survey found that among high school students, 36.1% of regular smokers vs. 17.0% of non-daily smokers purchased cigarettes in a store (Ringel, et al., 2000). In Harrison and colleagues’ analysis of the 1998 Minnesota Student Survey, teens who smoked heavily were less likely to report social sources as their only sources of cigarettes (Harrison, et al., 2000). Among teens who smoke, heavier smokers are most likely to provide cigarettes to other teens as a gift or for money. (Forster, et al., 2003, Wolfson, et al., 1997).

A greater reliance on social sources for cigarettes seems to result from a restriction in the commercial supply of cigarettes. In communities where cigarettes have become relatively difficult for underage youth to purchase commercially, adolescents have increasingly obtained cigarettes socially (DiFranza and Coleman, 2001, Altman, et al., 1999). In Forster and colleagues’ community trial, where towns were randomly assigned to either an intervention that focused on enforcement of youth cigarette commercial access laws or to a non-intervention control group, following the intervention, teens in intervention towns were more likely to have received their last cigarette from a social source than teens from control towns (Forster, et al., 1998).

This study examined the community trends from October 2000 to September 2003 in sources of cigarettes among past-month adolescent smokers in the Minnesota Adolescent Community Cohort (MACC) study. We hypothesized that youth would report less commercial access and greater social access over time, (controlling for age) during this period of increasing policy to restrict the commercial supply of cigarettes. Additionally we examined whether the probability of escalation in smoking intensity over time in communities varies with the different modes of access that youth in those communities employ. We hypothesized that compared to communities where commercial access was used less frequently, communities where commercial access methods were used more frequently would have a higher proportion of adolescents progressing to regular smoking.

Methods

Design

MACC is a longitudinal study measuring adolescent tobacco use patterns, perceptions, and attitudes. The state of Minnesota was divided into group-level units based on geographical and political (GPU) boundaries thought to reflect local tobacco control environments. These units were constructed based on the following four criteria: 1) the boundaries of the GPUs resemble existing geographic and/or political limits; 2) the boundaries of the GPUs reflect patterns of local tobacco program activities; 3) there is similar variation in youth smoking behavior across GPUs; and 4) a sufficient number of teens reside in each GPU to meet the sample size requirements. Using these criteria, Minnesota was first divided into 129 GPUs that included a mixture of counties, municipalities, school districts, urban neighborhoods and local planning districts. We then selected a stratified random sample of 60 GPUs. Of the 60 GPUs, 28 were rural (46%), 21 suburban (35%), 3 small city (5%), and 8 urban (14%). For more information about how the GPUs were selected see Chen et al. (under review). For this paper we hypothesized that youth living in the same GPUs would have a common tobacco access environment.

Five age cohorts were initially established (ages 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16) and approximately 60 participants, 12 in each age cohort, participated from each of 60 GPUs. The MACC study originally recruited a Minnesota cohort of 3,637 teens at baseline, approximately 725 each at ages 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16. Additionally, 587 12-year-olds were recruited one year after baseline. A combination of probability and quota sampling methods (to assure equal age distribution) was used to establish the six age cohorts. Surveys times were staggered such that surveys were administered to approximately one-sixth of the cohort members each month and then each youth was followed up at six month intervals. This meant that the baseline survey was administered between October 2000 and March 2001, the first follow-up survey was administered from April 2001 through September 2001, etc.

Sample

We used data from the first six MACC surveys (October 2000 – September 2003), restricting this sample to youth who were under age 18 at the time of the survey (100% of sample at survey 1, 72% of the sample at survey 6). At each of the 6 surveys only youth who reported smoking at least once in the previous month were included in this analysis. Our analytical sample ranged from 340 to 454 (Table 1). Subjects for this study were drawn from both the original baseline Minnesota cohort and the sample of 12-year-olds who were recruited one year after baseline. The new recruits were included to reduce the potential for age confounding and increase the sample size as the sample aged over time.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the previous month smoker youth sample at surveys 1 – 6 for the analytical sample and the whole Minnesota MACC cohort at baseline. Minnesota Adolescent Community Cohort, 2000-2003.

| MACC cohortˆ | Analytical sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey | Survey | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|

|

|

||||||

| n | 3633 | 340* | 417* | 454* | 421 | 382 | 364 |

| Age (mean) | 14.5 | 15.5 | 16.0 | 16.2 | 16.4 | 16.4 | 16.4 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male % | 49.2 | 44.1 | 47.5 | 48.0 | 48.0 | 48.2 | 48.1 |

| Female % | 50.8 | 55.6 | 52.5 | 52.0 | 52.0 | 51.8 | 51.9 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| African American or Black % | 5.0 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 3.0 |

| Am. Indian or Alaskan Native % | 2.3 | 7.9 | 6.2 | 6.6 | 6.2 | 6.5 | 5.2 |

| Asian % | 2.4 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| White % | 85.2 | 84.7 | 86.3 | 84.6 | 85.8 | 85.9 | 84.9 |

| Other % | 2.6 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 5.2 | 6.6 |

Sample increases between Survey 1 and Survey 2 as more youth are past month smokers at Survey 2 compared to Survey 1. Sample increases between Survey 2 and 3 due to recruitment of additional cohort of 12-year-olds at this time. Sample begins to decrease after survey 3 as more youth in the cohort reach their 18th birthday.

Four individuals are excluded from original MACC sample of 3,637 because their age sex or race was missing.

Data Collection

The survey was designed so that adolescents could answer potentially sensitive questions over the phone with non-revealing answers, e.g. a letter corresponding to a categorical response, in order to minimize bias that may result if a teen was concerned that a nearby parent or guardian may be listening to the phone conversation.

Smoking frequency, age, sex, and ethnicity were ascertained by youth self report. For ethnicity, adolescents were asked to indicate if they were: African American or Black, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Hispanic or Latino, White, or “Or something else?” (Interviewer recorded response). For these analyses we collapsed the categories of “Hispanic or Latino” and “Or something else” and labeled this category “other” due to small numbers. Using a series of survey questions all youth in the MACC study were classified as being at one of six smoking stages at each interview. The six MACC smoking stages were:

Never = Never smoked a cigarette, not even a few puffs.

Trier = Having smoked one whole cigarette or less (not including Never smokers).

< Monthly = smoked a whole cigarette but not smoked on any of the last 30 days.

Experimenter = Smoked less than 20 of the last 30 days and none of the last 7 days.

Regular = smoked less than 20 cigarettes in the last 30 days and smoked at least once in the past 7 days.

Established = Smoked more than 20 of the last 30 days.

For the purposes of this paper, we labeled those adolescents classified at stage 4, 5, or 6 as “monthly smokers”. “Weekly smokers” are those classified as a 5 or 6.

Social and commercial access measures were ascertained from the questions in Table 2. An individual would be coded as using a particular access method if he or she answered affirmatively to any of the questions relating to that type of source of cigarettes in the previous month. If this youth did not answer “yes” to any of the access method questions he/she would be coded as not having used that access method.

Table 2.

MACC Adolescent Phone Survey. Guide to how survey answers were used to classify access. Minnesota Adolescent Community Cohort 2000-2003.

|

Statistical analysis

The analyses allow for repeated measures, individuals nested within GPUs, and more than one source of random variation. We used a logistic model (using SAS PROC GLIMMIX (SAS Version 9.1)) to calculate probabilities and confidence intervals for several different tobacco access patterns reported in the month preceding the survey: those who used commercial access exclusively, those who used any commercial access, those who used social access exclusively, and those who used any social access. We also examined whether there was a longitudinal association between probability of social or commercial access method at the GPU-level and the aggregate smoking intensity in the GPUs.

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of our analytic sample at each survey and of the entire Minnesota MACC sample at survey 1. The mean age of smokers increased from 15.5 years at survey 1 to 16.4 years at survey 6 (note: because youth no longer were included in our sample after their 18th birthday and new 12 year-olds were recruited into the cohort at survey 3, the mean age increase is modest over the three-year period). The ethnic breakdown remained consistent throughout 6 surveys. At all surveys there were slightly more females than males in the sample of past month smokers.

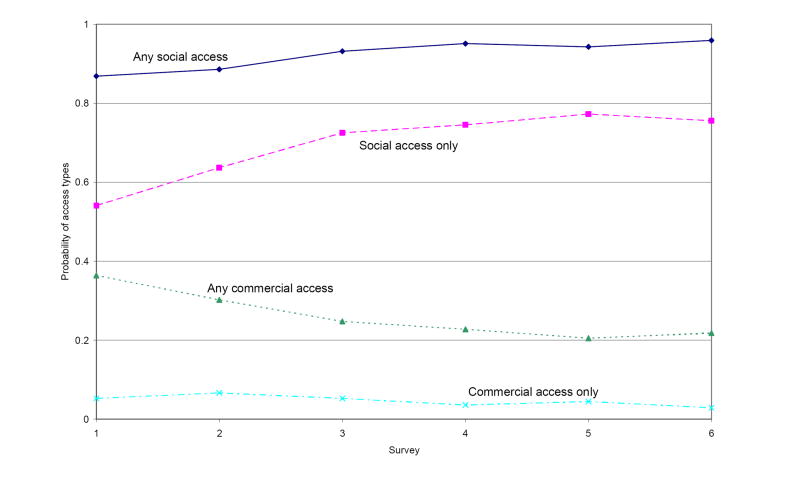

After adjustment for covariates (survey, age, ethnicity, gender, and smoking status), the probability of reporting any commercial access declined consistently over the period of the study from 0.36 to 0.22 at the first and sixth surveys respectively (p for trend < 0.0001) (see Figure 1). The probability of youth reporting that all tobacco obtained in the past month was through social access increased steadily over time from 0.54 at survey 1 to 0.76 at survey 6 (p for trend < 0.0001). The probability of reporting any social access was consistently high throughout the survey period and gradually increased from 0.87 at the first survey to 0.96 at the sixth survey (p for trend < 0.0001). The probability of using commercial access exclusively fell and was consistently very low throughout the study period ranging from 0.05 at survey 1 to 0.03 at survey 6 (p for trend = 0.0167).

Figure 1.

Access methods by survey among past month smokers. Adjusted for survey time, age, ethnicity, smoking status, and sex. n = 2371 observations. Minnesota Adolescent Community Cohort, 2000 – 2003.

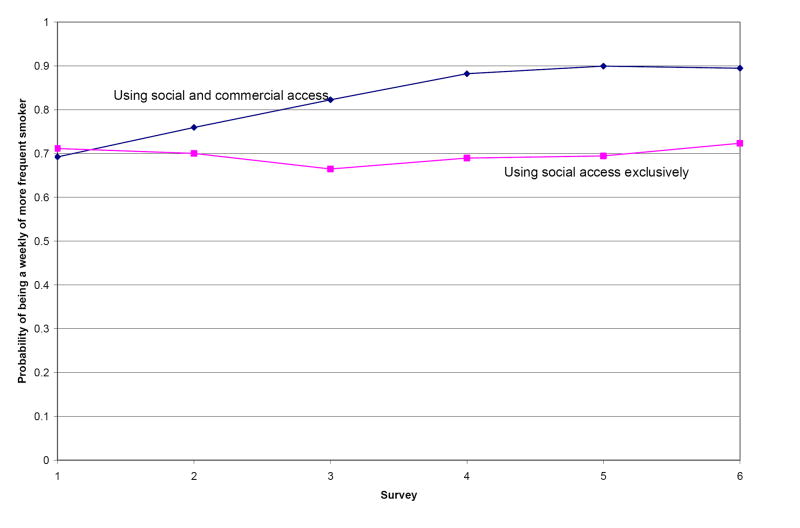

Figure 2 illustrates the significant difference in time trends (p < 0.0001) in which communities where youth were more likely to rely exclusively on social access had fewer youth who became weekly or more frequent smokers after adjusting for age, ethnicity, and sex. At survey 1, those who used any commercial access had a 0.69 (95% CI = 0.62, 0.76) probability of smoking at least weekly while those who used only social access had a 0.71 (95% CI = 0.65, 0.77) probability of smoking at least weekly. By survey 6, the probabilities for those who used any commercial access and those who used only social access were 0.89 (95% CI = 0.83, 0.94) and 0.72 (95% CI = 0.66, 0.78) respectively.

Figure 2.

Among youth who had smoked at least once in the past month, probability of being a weekly or more frequent smoker over time by access method, adjusted for age, sex, and ethnicity. 2371 observations used. Minnesota Adolescent Community Cohort, 2000-2003.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are: 1) a secular trend towards a reduction in use of commercial sources of cigarettes among past month smokers in the MACC study; 2) an accompanying increase in use of social sources; and 3) a trend in which communities where youth are more likely to obtain cigarettes exclusively through social sources had a lower proportion of youth becoming heavy smokers compared to communities where youth are more likely to use some commercial sources.

It is encouraging that there does seem to be a clear reduction in commercial access over the time period of the MACC study (Figure 1). Our study provides additional support to results from surveys by Synar (CDC, 2005) and Monitoring the Future (Johnson and O’Malley, 2006) that show fewer adolescent smokers are purchasing tobacco at retail outlets. This as a positive development given that communities where youth relied less on commercial access for cigarettes had a lower proportion of youth becoming heavy smokers. We believe that the trend of increasing enforcement of youth cigarette access laws since the 1990s has likely been responsible for the declining commercial access among youth.

Our finding that communities where youth are more likely to use social sources exclusively are places where fewer adolescents progress to weekly smoking has important implications. Our results do not support the view that efforts to shift adolescent tobacco sources from commercial to social would have no public health effects. Almost all tobacco that young people in the United States consume is at some point purchased in a commercial environment; hence, a reduction in commercial access even accompanied by an increase in social access, would likely result in fewer cigarettes being available for social exchange. Wolfson and colleagues discovered that one of the strongest predictors of whether a teen plays the role of social provider was whether he/she has made a recent purchase attempt from a commercial source (Wolfson, et al., 1997). Forster and colleagues also observed that, “Social sources do not merely substitute for commercial sources, but extend their reach.” (Forster, et al., 2003, page 153). The reduction in commercial access that we see over time coupled with the increase in social access does not necessarily mean that the total number of cigarettes consumed remained constant; in fact, we found that those using social access smoked less frequently.

One potential limitation of this study is that our results may be confounded by age. The MACC cohort grows older as time passes, and age is significantly associated with increased use of any commercial access and less use of social access (Ringel, et al., 2000, Clark, et al., 2000, Forster, et al., 1997). However, two elements protect this study from bias due to age confounding. First, we included age as a control variable in all models. Second, because additional 12-year-olds were added to the study at the third survey, there are fewer time points with sparse data. Still it is possible that some residual confounding due to age does exist and that the true secular trend of decreased use of commercial access and an increase in social access is actually larger than what we have seen here. Another limitation is our inability to adjust for parent’s socio-economic status since these data were not collected in MACC.

Conclusions

Our results show that the probability of exclusive social access increased as the probability of any commercial access decreased in communities during our study period. This community-level trend was followed by a diminishing proportion of adolescent smokers reporting more frequent smoking. Hence, it is important to continue efforts to decrease commercial access to cigarettes among youth.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institute of Health R01-CA086191, Jean Forster, Principal Investigator. Thank you to Kathleen Lenk for her edits.

Footnotes

Precis

Youth shifted to relying more on social sources and less on commercial sources. This trend may translate to youth being less likely to progress to heavier smoking.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altman DG, Wheelis AY, McFarlane M, Lee H, Fortmann SP. The relationship between tobacco access and use among adolescents: a four community study. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:759–75. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00332-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. Minors’ access to tobacco--Missouri, 1992, and Texas, 1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993;42:125–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. Usual sources of cigarettes for middle and high school students--Texas, 1998-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:900–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State Tobacco Activities Tracking and Evaluation (STATE) System. 2005 Place Published. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/statesystem/

- Clark PI, Natanblut SL, Schmitt CL, Wolters C, Iachan R. Factors associated with tobacco sales to minors: lessons learned from the FDA compliance checks. Jama. 2000;284:729–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.6.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Difranza JR. Youth access: the baby and the bath water. Tob Control. 2000;9:120–1. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Brown LJ. The Tobacco Institute’s “It’s the Law” campaign: has it halted illegal sales of tobacco to children? Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1271–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.9.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Coleman M. Sources of tobacco for youths in communities with strong enforcement of youth access laws. Tob Control. 2001;10:323–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.4.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster J, Chen V, Blaine T, Perry C, Toomey T. Social exchange of cigarettes by youth. Tob Control. 2003;12:148–54. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster JL, Murray DM, Wolfson M, Blaine TM, Wagenaar AC, Hennrikus DJ. The effects of community policies to reduce youth access to tobacco. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1193–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.8.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster JL, Wolfson M, Murray DM, Wagenaar AC, Claxton AJ. Perceived and measured availability of tobacco to youths in 14 Minnesota communities: the TPOP Study. Tobacco Policy Options for Prevention. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13:167–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Jarrette AD, Wilson EA, O’Riordan DL, Jacob Arriola KR. Reducing minors’ access to tobacco: eight years’ experience in Hawaii. Prev Med. 2007;44:55–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PA, Fulkerson JA, Park E. The relative importance of social versus commercial sources in youth access to tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. Prev Med. 2000;31:39–48. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naum GP, 3rd, Yarian DO, McKenna JP. Cigarette availability to minors. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1995;95:663–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringel JS, Pacula RL, Wasserman J. Youth Access to Cigarettes: Results from the 1999 National Youth Tobacco Survey, Legacy First Look Report #5. American Legacy Foundation; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. State Oversight of Tobacco Sales to Minors. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General; Atlanta, GA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson M, Forster JL, Claxton AJ, Murray DM. Adolescent smokers’ provision of tobacco to other adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:649–51. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]