Abstract

This work is a continuation from another study previously published in this journal. Both the former and the present works are dedicated to investigating the bistable behavior of the lac operon in Escherichia coli from a mathematical modeling point of view. In the previous article, we developed a detailed mathematical model that accounts for all of the known regulatory mechanisms in this system, and studied the effect of inducing the operon with lactose instead of an artificial inducer. In this article, the model is improved to account, in a more detailed way, for the interaction of the repressor molecules with the three lac operators. A recently discovered cooperative interaction between the CAP molecule (an activator of the lactose operon) and Operator 3 (which influences DNA folding) is also included in this new version of the model. The growth rate dependence on the rate of energy entering the bacteria (in the form of transported glucose molecules and of metabolized lactose molecules) is also considered. A large number of numerical experiments is carried out with this improved model. The results are discussed in regard to the bistable behavior of the lactose operon. Special attention is paid to the effect that a variable growth rate has on the system dynamics.

INTRODUCTION

In 1960, Jacob et al. (1) introduced the operon concept as a consequence of their studies on the control of lactose metabolism in Escherichia coli. Concomitantly, they discovered an ubiquitous mechanism for gene regulation: repression. In the lac operon, a repressor molecule can bind a specific site along the DNA molecule (see Figs. 1 and 2) to halt transcription of the operon structural genes. One of the lac operon genes encodes for a membrane permease protein, which transports lactose into the cell. Intracellular lactose is degraded into glucose and galactose by β-galactosidase, an enzyme encoded for by another gene in the lac operon. Furthermore, allolactose (a by-product of lactose metabolism) binds and inactivates the repressor molecules, thus halting repression of the expression of the structural genes. Thus, the lactose operon regulatory pathway involves a positive feedback loop, which can give rise to bistability (2).

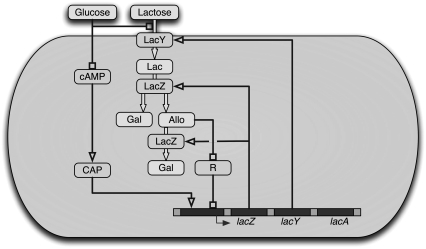

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the lac operon regulatory pathway. Figure was taken from Santillán et al. (17).

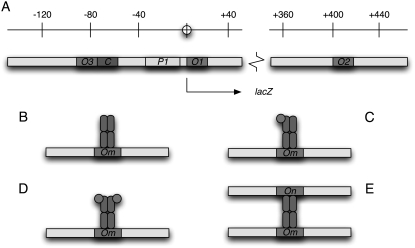

FIGURE 2.

(A) Schematic representation of the regulatory elements located in lac operon DNA. P1 denotes the promoter, O1, O2, and O3 correspond the three operators (repressor binding sites), and C is the binding site for the cAMP-cAMP receptor protein complex. The different ways in which a repressor molecule can interact with the operator sites are represented in B–E. Namely, a free repressor molecule (B), one with a single subunit bound by allolactose (C), or one with the two subunits in the same side bound by allolactose (D) can bind a single operator. Moreover, a free repressor molecule can bind two different operators simultaneously.

The capacity of a system to switch in an all-or-none manner between alternative steady states, and the presence of hysteresis, are the hallmarks of bistability. Bistability has been invoked as a possible explanation for catastrophic events in ecology (3), mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in animal cells (4–6), cell cycle regulatory circuits in Xenopus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (7,8), the generation of switchlike biochemical responses (4,5,9), and the establishment of cell cycle oscillations and mutually exclusive cell cycle phases (8,10). More recently, Dubnau and Losick (11) discussed the possible evolutionary advantages of the heterogeneity in bacteria populations emerging from bistability.

The bistable behavior of the lac operon has been the subject of a number of investigations. Signs of bistability were first noted by Monod and co-workers more than fifty years ago, although it was not fully recognized at the time. The first detailed studies were performed by Novick and Weiner (12) and Cohn and Horibata (13). Further experimental research was carried out by Maloney and Rotman (14) and Chung and Stephanopoulos (15).

In a recent article, Ozbudak et al. (16) reported a set of ingenious experiments that allowed them to quantify the lac-operon expression level in single bacteria. Their results not only confirmed the existence of bistability in the lac operon when induced with the nonmetabolizable inducer thio-methylgalactoside (TMG), but also raised important questions. Namely, when Ozbudak et al. repeated their experiments using lactose as inducer, they found no evidence for bistability. We investigated this issue from a mathematical modeling viewpoint in a previous article (17). There, we developed a mathematical model for the lac operon regulatory pathway, and used it to investigate the effect that inducing the operon with lactose has on the system bistable behavior.

In this article, we extend this investigation by taking into account some further, recently discovered, details of the lac operon regulatory mechanisms. Namely: the repressor molecule—which is a tetramer made up of two functional dimers—can still bind a single operator if one of its dimers is free from lactose (18), and the activator CAP facilitates the formation of a DNA loop between Operators 1 and 3 (19). Additionally, we consider in this model the fact that the bacterial growth-rate varies in accordance to the glucose uptake and the lactose metabolism rates, and study how this affects the system dynamic behavior.

THEORY

Mathematical model

In Appendix A, a mathematical model for the lactose operon is developed. This model is an improvement and generalization of the one introduced in Santillán et al. (17). In this new model, we take into account more details of the interaction between lac repressor and inducer (lactose or TMG) molecules. Specifically, instead of assuming—as in Santillán et al. (17)—that only free repressors can bind an operator, we take into account the fact that a repressor bound with one or two inducers in the same side can be active (see Fig. 2). There is new evidence that, when bound to its corresponding site, a CAP molecule not only increases the probability that a polymerase binds the promoter, but also facilitates the formation of a DNA loop in such a way that a single repressor binds Operators 1 and 3 (19). The present version of the model, unlike the previous one, takes into consideration this new source of cooperativity by assuming that the binding of a CAP molecule and the formation of the Operator 1:Repressor:Operator 3 loop only happen simultaneously. Finally, the model in Santillán et al. (17), as many others, assumes a constant growth rate (μ). This situation corresponds to an experimental setup in which the growing medium is rich in a substance like succinate, which, acting as a reliable carbon source, ensures a high growth rate for the bacterial culture, and affects neither the glucose nor the lactose uptake and metabolism. In the present model, we consider a variable growth rate that depends on the glucose uptake rate as well as on the rate of lactose metabolism. This refinement to the model allows us to simulate a bacterial culture growing in a medium containing a mixture of glucose and lactose, and no other carbon source.

A glossary of all the model variables and parameters is given in Table 1. A general description of the model equations, presented in Table 2, is given below. To follow this description, the reader may find it useful to refer to Figs. 1 and 2, which present schematic representations of the lac operon regulatory pathway and of the regulatory elements located in operon DNA.

TABLE 1.

Glossary of variables and parameters in the model equations

| [M] | Concentration of lacZ mRNA. |

| [E] | Concentration of LacZ polypeptides. |

| [L] | Intracellular lactose concentration. |

| [D] | Concentration of lac operon copies per bacterium. |

| [A] | Intracellular allolactose concentration. |

| [Q] | lac permease concentration. |

| [B] | β-galactosidase concentration. |

| φM | Maximum lactose-to-allolactose conversion rate per β-galactosidase. |

| μ | Bacterial growth rate. |

| γM | lacZ mRNA degradation rate. |

| γE | LacZ polypeptide degradation rate. |

| kM | Maximal transcription initiation rate of the lac promoter. |

| kE | Translation initiation rate of the lacZ transcript. |

| kL | Maximal lactose uptake rate per permease. |

| pp | Probability that a polymerase is bound to the lac promoter. |

| pc | Probability that a CAP complex is bound to its binding site. |

| ppc | Probability that both a polymerase and a CAP complex are bound to their sites. |

| kpc | Parameter that accounts for the cooperativity between the promoter and the CAP sites. |

| KG and nh | Parameters that determine the dependence of pc on Ge. |

|

Probability that a polymerase is bound to the promoter, and ready to start transcription. |

| ξi | Parameter that determines the affinity of an active repressor for Operator Oi. |

| ξij | Parameter that determines the stability of the Oi-repressor-Oj complex. |

| ρ1 | Probability that a repressor molecule is able to bind a single operator. |

| ρ2 | Probability that a repressor molecule is able to bind two operators simultaneously. |

| KA | Dissociation constant for the repressor-allolactose complex formation reaction. |

| βL | Permease activity as a function of the external lactose concentration. |

| κL | Half-saturation constant for the lactose uptake rate. |

| βL | Permease activity as a function of the external glucose concentration. |

| φG and κG | Parameters that determine the dependence of βL on Ge. |

| ℳ | Lactose-to-allolactose metabolism rate per β-galactosidase. |

| JG | Glucose uptake rate. |

|

Maximum glucose uptake rate. |

| ΦG | Half-saturation constant for the glucose uptake rate. |

| JL | Production rate of glucoselike molecules via lactose metabolism. |

TABLE 2.

A mathematical model for the lac operon in E. coli

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

The present model consists of three ordinary differential equations that account for the dynamics of the lacZ messenger RNA (Eq. 1), LacZ polypeptide (Eq. 2), and intracellular lactose (Eq. 3) concentrations. Messenger RNA (mRNA) is produced via transcription of the lac operon genes, and its concentration decreases because of active degradation and dilution due to cell growth. The dependence of the growth rate μ on the glucose uptake rate JG (defined in Eq. 17), and on the lactose metabolism rate JL (defined in Eq. 18), is given in Eq. 7.

(defined in Eq. 11) accounts for regulation of transcription initiation by active repressors. This function gives the probability that the lac promoter is not repressed by an active repressor bound to Operator O1. It accounts for the interactions of the repressor and allolactose molecules, of the repressor molecules and the three different lac operators (including DNA looping), of the CAP activator and the mRNA polymerase, and of CAP and the DNA loop involving Operators 1 and 3.

(defined in Eq. 11) accounts for regulation of transcription initiation by active repressors. This function gives the probability that the lac promoter is not repressed by an active repressor bound to Operator O1. It accounts for the interactions of the repressor and allolactose molecules, of the repressor molecules and the three different lac operators (including DNA looping), of the CAP activator and the mRNA polymerase, and of CAP and the DNA loop involving Operators 1 and 3.

Repressor molecules are tetramers formed by the union of two active dimers. Every one of the four repressor subunits can be bound by an allolactose molecule. Free repressors, repressors bound by one allolactose, and repressors bound by two allolactoses in the same dimer can bind a single operator (18). The fraction of repressors able to do so is ρ1(A) (compare to Eq. 12). Conversely, only free repressors, whose fraction is given by ρ2(A) (see Eq. 13), can bind two different operators simultaneously.

The function ppc(Ge) (Eq. 8) denotes the modulation of transcription initiation by the cooperative interaction between a CAP activator and a polymerase, each bound to its respective site. Production of cyclic AMP (cAMP) is inhibited by extracellular glucose. cAMP further binds the so-called cAMP receptor protein to form the CAP complex. Finally, CAP binds a specific site near the lac promoter and enhances transcription initiation. The probability of finding a CAP molecule bound to its corresponding site is given by pc (Eq. 10).

The probability that a CAP activator is bound to its corresponding site is given by the function pcp(Ge) (Eq. 9). Its presence in the definition of  (Eq. 11) accounts for the fact that it affects the formation of the DNA loop in which a single repressor binds Operators 1 and 3.

(Eq. 11) accounts for the fact that it affects the formation of the DNA loop in which a single repressor binds Operators 1 and 3.

Let B and Q, respectively, denote the β-galactosidase and permease concentrations. The translation initiation rate of lacZ transcripts is kE, while γE is the degradation rate of lacZ polypeptides. Given that the corresponding parameters for lacY transcripts and polypeptides attain similar values, that β-galactosidase is a homo-tetramer made up of four identical lacZ polypeptides, and that permease is a lacY monomer, it follows that Q = E and B = E/4 (Eqs. 5 and 6).

Lactose is transported into the bacterium by a catalytic process in which permease proteins play a central role. Thus, the lactose influx rate is assumed to be kLβL(Le)Q, with the function βL(Le) given by Eq. 14. Extracellular glucose inhibits lactose uptake, a mechanism known as inducer exclusion, and this is accounted for by βG(Ge) (Eq. 15). Once inside the cell, lactose is metabolized by β-galactosidase. Approximately half of the lactose molecules are transformed into allolactose, while the rest enter the catalytic pathway that produces glucose and galactose. In our model,  with

with  defined in Eq. 16, denotes the lactose-to-allolactose metabolism rate, which equals the lactose-to-galactose metabolism rate. Allolactose is further metabolized into galactose by β-galactosidase. From the assumptions that the corresponding metabolism parameters are similar to those of lactose, and that the allolactose production rate is much higher than its degradation plus dilution rate, it follows that A ≈ L (Eq. 4).

defined in Eq. 16, denotes the lactose-to-allolactose metabolism rate, which equals the lactose-to-galactose metabolism rate. Allolactose is further metabolized into galactose by β-galactosidase. From the assumptions that the corresponding metabolism parameters are similar to those of lactose, and that the allolactose production rate is much higher than its degradation plus dilution rate, it follows that A ≈ L (Eq. 4).

Parameter values

Except for KA, all the parameters in the model are estimated from experimental results in Appendix B and tabulated in Table 3. Parameter KA remains as a free parameter that will be estimated by fitting the model results to those obtained experimentally by Ozbudak et al. (16).

TABLE 3.

Values of the parameters in the lac operon model equations presented in Table 2, as estimated in Appendix B

| [D] ≈ 2 mpb | kM ≈ 0.18 min−1 |

| ɛ ≈ 5.2 × 10−10 mpb−1 | γM ≈ 0.46 min−1 |

| pp ≈ 0.127 | kpc ≈ 30 |

| KG ≈ 2.6 μM | nh ≈ 1.3 |

| ξ1 ≈ 17 | ξ2 ≈ 0.85 |

| ξ3 ≈ 0.17 | ξ12 ≈ 1261.7 |

| ξ13 ≈ 430.6 | ξ23 ≈ 0 |

| KA ≈ ? mpb | kE ≈ 18.8 min−1 |

| γE ≈ 0.01 min−1 | kL ≈ 6.0 × 104 min−1 |

| φM ≈ ∈ [0, 3.8 × 104] min−1 | κL ≈ 680 μM |

| φG ≈ 0.35 | κG ≈ 1.0 μM |

| κM ≈ 7.0 × 105 mpb |

≈ 4.4 × 107 mpb min−1 ≈ 4.4 × 107 mpb min−1

|

| ΦG ≈ 22 μM |

Parameter KA is the only parameter we were unable to estimate. The unit mpb stands for molecules per average bacterium.

METHODS

Calculation of the bifurcation diagrams

If the growth rate (μ), which is variable as detailed in the equations of Table 2, is held at a constant value, it can be shown after a little algebra that the L steady-state values are those that satisfy the following equation:

|

(19) |

Depending on [Ge] and [Le], Eq. 19 has up to three roots, which correspond to the uninduced and induced stable steady states, separated by an unstable saddle node. The uninduced and induced states may appear (together with the saddle node) and disappear (by colliding with the saddle node) via a saddle node bifurcation as [Le] varies. The mathematical conditions for the occurrence of these bifurcations are that Eq. 19 is satisfied, and that the derivatives, with respect to L, of both sides of Eq. 19 are also equal (see (20)). The values of [Le] and [L] such that these two conditions are satisfied, given the value of [Ge], were numerically determined with the aid of Octave's algorithm fsolve. Finally, by repeating this process for several Ge values, the bifurcation diagram in the Le versus Ge parameter space can be drawn.

Given the model complexity, it was not possible to derive a simple equation whose solutions give the steady-state values when a variable growth rate is considered. Therefore, we implemented the following algorithm to find the bifurcation points:

For a given value of Ge, the model differential equations are numerically integrated (using the algorithm lsode of Octave) with Le = 0 μM and the initial conditions M = 0 mpb, E = 0 mpb, and L = 0 mpb, for a time period of 2000 min to ensure that the system reaches the steady state.

The value of Le is increased and the model equations are solved again, using the last point of the previous numerical solution as the initial condition.

The last step is repeated iteratively until the value of Le is so high that the system shifts from the uninduced to the induced state. This value of Le corresponds to the upper border of the bistable region in the bifurcation diagram.

Step 2 is repeated iteratively once more, but now decreasing the Le value, until the system switches back from the induced to the uninduced state. This value of Le corresponds to the lower border of the bistable region in the bifurcation diagram.

Finally, Steps 1–4 are repeated for several values of Ge.

Stochastic simulations

We carried out stochastic simulations with the model described in this section using Gillespie's Tau-Leap algorithm (21,22), which we implemented in Python.

Calculation of the transition rate constants between the induced and the uninduced states

Following Warren and ten Wolde (23,24), the rates of transition between the induced and uninduced states—when the Ge and Le values are such that bistability exists—are calculated as follows. First, we constructed new time series, S, from the time series of lactose (or TMG) values, L, resulting from the stochastic simulations. By definition, S(t) = 1, whenever L(t) > L*I, and S(t) = 0 otherwise, where L*I is the value of L at the unstable saddle node located between the uninduced and induced states. Then, the times the system spends in the uninduced and induced states are calculated from the time series S, as well as the histograms of residence times in both states. In all cases, these histograms can be fitted by exponential distributions of the form H(t) = A exp(–kt), where k is the corresponding transition rate constant. In what follows, the transition rate constants from the uninduced (induced) to the induced (uninduced) state shall be denoted as k+ (k–).

RESULTS

Comparison with experimental results

Ozbudak et al. (16) carried out experiments in which E. coli cultures were grown in the M9 minimal medium, with succinate as the main carbon source, supplemented with varying amounts of glucose and TMG. They engineered a DNA segment in which the gfp gene was under the control of the wild-type lac promoter, and inserted this segment into the chromosome of the cultured E. coli bacteria, at the λ-insertion site. In these mutant bacteria, Ozbudak et al. estimated the lac operon expression level in each bacterium by simply measuring the intensity of green fluorescence.

Ozbudak et al. observed that the histograms of fluorescence intensities were unimodal, and that the mean value corresponded to low induction levels of the lac operon, when the bacterial growth medium had low TMG levels. After the TMG concentration surpassed a given threshold, the histograms became bimodal, which can be viewed as evidence for bistability: the original (new) mode corresponds to the uninduced (induced) steady state. With further increments of the TMG concentration, the mode corresponding to the uninduced state disappeared, and the histogram became unimodal again. When the experiment was repeated by decreasing the concentrations of TMG, the opposite behavior was observed. Ozbudak et al. measured the range of TMG concentrations for which bistability was obtained, for several concentrations of external glucose. When they repeated the same experiments with the natural inducer (lactose), they were unable to find analogous evidence for bistability, even when lactose was given at saturation levels. In these last experiments, they employed glucose concentrations in the same range as in the experiments with TMG.

Following Santillán et al. (17), we stated by simulating the Ozbudak et al. experiments. For this, we set μ = 0.02 min−1 to account for the presence of a reliable carbon source (succinate) and φM = 0 min−1 (to simulate induction with TMG which is not metabolized by β-galactosidase). Then, we calculated the bifurcation points and plotted them in the Le versus Ge parameter space, using the procedure described in Methods. We took KA as a free parameter, and found that KA = 9.0 × 105 mpb gives a reasonable fit to the experimental points of Ozbudak et al. Both the model bifurcation diagram and the experimental points are presented in Fig. 3 A. Note that the bistability region predicted by the model is wider than the experimental one. Three possible explanations for this discrepancy are: 1), the lac promoter-gfp fusion employed by Ozbudak et al. as a reporter lacks Operators O2 and O3; 2), the difficulty in measuring exactly the Le values at which the bimodal histograms appear and disappear; and 3), the phase diagram of Fig. 3 A is based upon a mean-field analysis and so, biochemical noise can change the phase boundaries (25).

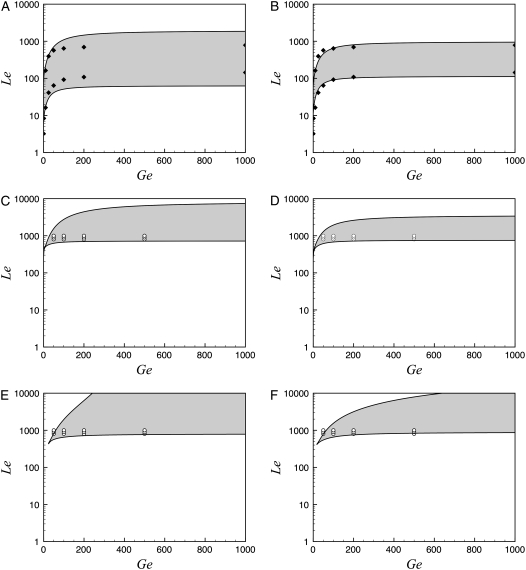

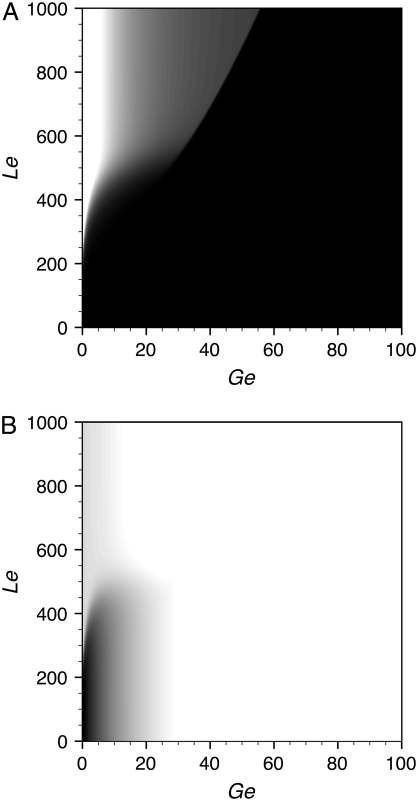

FIGURE 3.

Bifurcation diagrams in the Le versus Ge parameter space, calculated with the present model under various conditions. In all cases, the bistability region is shaded, while the monostable induced (top) and uninduced (bottom) regions are uncolored. In the left column graphs we used the parameter values tabulated in Table 3, and set KA = 8.2 × 105 mpb. In the right column graphs all parameters ξi and ξij were reduced to 0.15 times the value reported in Table 3, and KA was set to 2.8 × 106 mpb. To calculate the graphs in the first row (A and B), we set φM = 0 min−1 (to simulate induction of the lac operon with the nonmetabolizable TMG) and μ = 0.02 min−1 (to simulate a bacterial culture growing in a medium that contains a reliable carbon source not affecting the lac operon induction). The KA values referred to above were chosen to fit the experimental results of Ozbudak et al. (16), which are shown with solid diamonds. In the second row graphs we keep μ = 0.02 min−1, but increase φM to simulate the usage of lactose to induce the operon. In panel C, φM 3.8 × 104 min−1, while in panel D, φM 3.0 × 104 min−1. Finally, in the third row graphs, a variable growth rate was considered, together with increased φM values. The open circles in graphs C–F denote the Ge and Le values for which the stochastic simulations in Figs. 4–7 were carried out.

A fourth possible explanation for the disagreement between the model and the experimental results is that our estimated parameter values differ from those corresponding to the E. coli strain used by Ozbudak et al. To account for this possibility, we explored the parameter space looking for a better fit. We found that it can be obtained by decreasing the parameters ξi and ξij to 20% of the values reported in Table 3, and by setting KA = 2.7 × 106 mpb. The results are shown in Fig. 3 B.

Effect of using lactose as inducer on the operon bistable behavior

The effect of using a metabolizable inducer (lactose), instead of a nonmetabolizable one (TMG), can be simulated by increasing the value of parameter φM (17). We did this for the two parameter sets described in the previous paragraph, and the results are shown in Fig. 3, C and D. Note that, although quantitatively different, the effect of lactose metabolism on the bistable behavior of the lac operon is qualitatively similar in both cases. Thus, bistability is not eliminated by the inclusion of lactose metabolism, but the region of bistability moves upward toward higher [Le] values. If the value of φM is high enough, it can render the operon induction impossible, even with extremely high [Le] values. Moreover, the bistable region collapses into a cusp catastrophe for extremely low [Ge] values. These results agree completely with those in Santillán et al. (17).

Although φM is the parameter that changes the most when TMG is substituted by lactose, other parameters like the affinity of the allolactose-repressor complex (KA), the parameters associated to the lactose transport kinetics (kL and κL), and κM, can change as well. We tested the sensitivity of the model bistable behavior to variations on all those parameters, and found that KA is, by far, the most important in that respect.

There is evidence that TMG is a weaker inducer than lactose (26), and so KA should be decreased when induction of the operon with lactose is simulated. After recalculating the bifurcation diagrams of Fig. 3, C and D, with decreased KA values, we found that the upper boundary moves downwards along the Le axis quite a bit, while the lower border also moves downwards but to a lesser extent. Thus, the overall effect is that the width of the bistability region decreases when KA is diminished. For instance, when KA is reduced to 25%, the value used in the TMG simulations and φM is set such that the bistability-region lower border lies at ∼Le = 1000 μM, the bistability-region width is reduced by approximately one order of magnitude.

Variable growth rate and bistability

The presence of a reliable carbon source, such as succinate, guarantees the growth of the bacterial culture at a steady rate. Although useful when designing an experiment, this is not a likely situation under natural conditions. When the growth medium contains a mixture of glucose and lactose, and no other carbon source, the bacterial growth rate is not constant but a function of the glucose uptake and the lactose metabolism rates. To investigate the influence of a variable growth rate on the bistable behavior of the lac operon, we recalculated the bifurcation diagrams in the Le versus Ge parameter space, using the model equations in Table 2, with the parameter sets of Fig. 3, C and D. The results are shown in Fig. 3, E and F.

Comparing Fig. 3, C and E, as well as Fig. 3, D and F, we conclude that a variable growth rate has no appreciable effect on the lower boundary of the bistable region. However, the upper border is affected. Instead of being nearly constant for moderate to high values of Ge, and rapidly decreasing for low Ge levels as in Fig. 3, C and D, the upper border increases steadily as Ge increases when μ is not constant. Moreover, for low to moderate Ge levels, the bistable region corresponding to a constant growth rate is wider than that corresponding to a variable μ, while the reverse happens for high external glucose concentrations. Another important difference is that the location of the cusp catastrophe moves to the right when a variable growth rate is considered.

We also tested the effect that decreasing the parameter KA has on the system bistable behavior and found, again, that the width of the bistability region rapidly decreases as KA decreases, while its lower boundary remains with little change.

Intrinsic noise and its effect on the operon dynamics

The lacZ mRNA degradation rate is so high that, according to the model, the average number of mRNA molecules per bacterium is ∼0.75 when the operon is fully induced. Therefore, there must be quite high levels if intrinsic noise, which in turn may have important effects on the system dynamic behavior. To test this, we carried out stochastic simulations (following the process outlined in the Methods section) for several conditions of external lactose and glucose. We repeated these simulations for the four parameter sets corresponding to Fig. 3, C–F.

In all cases, the simulations were carried out for 200,000 min to guarantee that the system reached the steady state and, if the (Ge, Le) point lies inside the bistability region, that the system state switches back and forth between the uninduced and induced states several times. Following Santillán et al. (17), we assumed that φM is ∼3–4 × 104 min−1. This implies that even if Le is as high as 1000 μM, the (Ge, Le) point lies very close to the lower border of the bistable region for moderate to high Ge levels.

Histograms of lactose molecule counts were calculated for each stochastic simulation. We observed that whenever the (Ge, Le) point lies below the bistability region, the histograms' maximum is very close to zero, and they quickly decay as the number of lactose molecules increase. We also carried out simulations for Ge and Le values inside the bistable region, and even a few with the (Ge, Le) point located in the induced monostable region. The histograms we obtained are presented in Figs. 4–7, which respectively correspond to the parameter sets of Fig. 3, C–F.

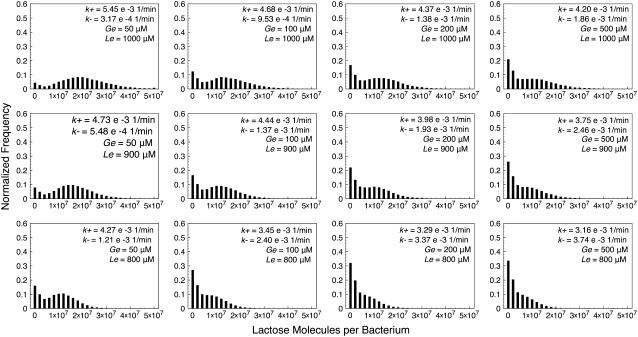

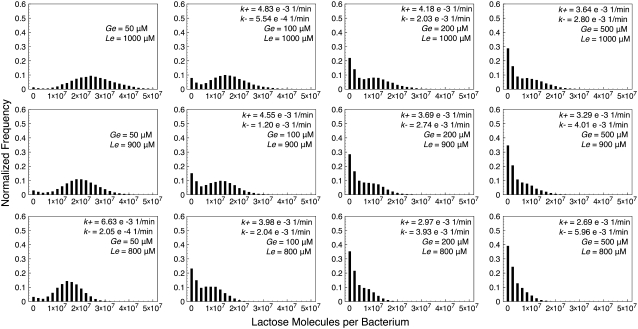

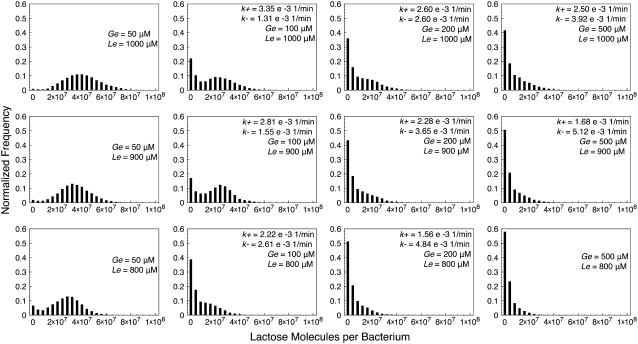

FIGURE 4.

Histograms of lactose molecules per bacterium, calculated from stochastic simulations carried out with the set of parameter values corresponding to Fig. 3 C (constant growth rate), for different combinations of Ge and Le values. All simulations were run for 200,000 min to ensure that, if the (Ge, Le) point lies in the bistability region, the system gates several times between the uninduced and the induced states. In each histogram, the transition rates from the uninduced to the induced (k+), and from the induced to the uninduced (k–) states are shown.

FIGURE 5.

Histograms of lactose molecules per bacterium, calculated from stochastic simulations carried out with the set of parameter values corresponding to Fig. 3 D (constant growth rate), for different combinations of Ge and Le values. In each histogram, the transition rates from the uninduced to the induced (k+) and from the induced to the uninduced (k–) states are shown.

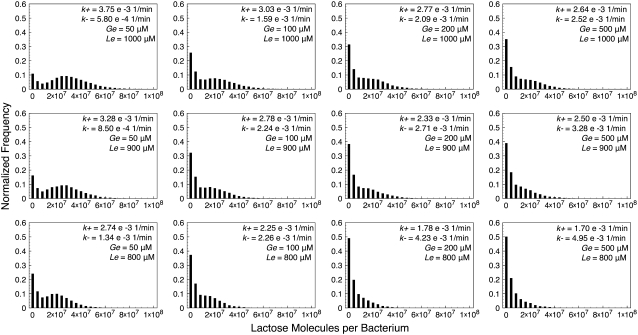

FIGURE 6.

Histograms of lactose molecules per bacterium, calculated from stochastic simulations carried out with the set of parameter values corresponding to Fig. 3 E (constant growth rate), for different combinations of Ge and Le values. In each histogram, if bistability exists, the transition rates from the uninduced to the induced (k+), and from the induced to the uninduced (k–) states are shown.

FIGURE 7.

Histograms of lactose molecules per bacterium, calculated from stochastic simulations carried out with the set of parameter values corresponding to Fig. 3 F (constant growth rate), for different combinations of Ge and Le values. In each histogram, if bistability exists, the transition rates from the uninduced to the induced (k+), and from the induced to the uninduced (k–) states are shown.

One would expect the histograms to be bimodal whenever the (Ge, Le) point is located within the bistability region; each mode corresponding to one of the two available steady states. This is clearly observed in some of the plots in Figs. 4–7, but not in as many as expected. The reason for this is that both modes are remarkably wide, and thus merge such that they are hard to distinguish separately. In general, the bimodal distributions are more prominent as the value of Le increases and the (Ge, Le) point moves upwards in the bistability region, and as the value of Ge decreases and the (Ge, Le) point approaches the cusp catastrophe.

The effect of a variable growth rate can be analyzed by comparing Figs. 4 and 6, as well as Figs. 5 and 7. Notice that the changes in the behavior of the constant and variable growth-rate histograms are consistent with the cusp catastrophe point moving right along the Ge axis, in the variable μ case. Interestingly, the fact that the upper border of the bistable region behaves differently in the constant and variable μ cases seems to have no effect on the histograms, except for the points that lie in the induced monostable region in the later case.

We also calculated, following the procedure detailed in the Methods section, the transition rates from the uninduced to the induced state (k+), and from the induced to the uninduced one (k–). We did this for each of the stochastic simulations described in the previous paragraph, and the results are shown next to the corresponding histograms in Figs. 4–7. Notice that, in all cases, k+ increases and k– decreases as Le increases; and that k– increases and k+ decreases as Ge increases. This behavior indicates that the induced (uninduced) state strengthens (weakens) its stability as the (Ge, Le) point approaches the bistability region upper boundary, and as it gets away from its lower border.

Other interesting observations that can be derived from the reported transition rates are that the residence times predicted by the model are all of ∼103 min, and that the bimodal distributions can only be clearly noticed if

Effect of the media conditions on the operon induction level and the bacterial growth rate

To better understand the dynamic performance of the lac operon, we numerically solved the model equations with the parameter set of Fig. 3 E, in which the growth rate is variable for several different levels of Ge and Le. In all cases, the numeric simulations were carried out for 2000 min to ensure that the system reaches a steady state, starting with the initial values M = 0 mpb, E = 0 mpb, and L = 0 mpb. Given this initial condition, the system reaches the uninduced steady state whenever it exists; otherwise, it evolves toward the induced steady state. For every one of these simulations, we recorded the β-galactosidase steady-state value, which we use as an indication of the operon induction level, and computed the corresponding steady-state growth rate. The results are shown in Fig. 8.

FIGURE 8.

Steady-state operon induction level (A), defined as proportional to the concentration of LacZ polypeptides (E), and steady-state bacterial growth rate (B), calculated for different values of Ge and Le. For given values of Ge and Le, the E and μ steady-state values were computed by numerically solving the model equations for 2000 min, to ensure that the system reaches a steady state. This starts with the initial condition M = 0 mpb, E = 0 mpb, and L = 0 mpb, so the system reaches the uninduced steady state whenever it exists. Black and white, respectively, represent the minimum and maximum values of the corresponding variables in both graphs.

In Fig. 8 A, note that, for  the system remains in the uninduced state whenever

the system remains in the uninduced state whenever  (the exact value depends on Le). However, there is a sudden transition to the induced state when the external glucose level decreases below a certain value. From the way we carried out the simulations, this transition corresponds to the saddle-node bifurcation in which the uninduced state disappears by colliding with the intermediate saddle node. Once the system is in the induced state, the operon induction level increases continuously until it reaches its maximum value for very low Ge values. However, when

(the exact value depends on Le). However, there is a sudden transition to the induced state when the external glucose level decreases below a certain value. From the way we carried out the simulations, this transition corresponds to the saddle-node bifurcation in which the uninduced state disappears by colliding with the intermediate saddle node. Once the system is in the induced state, the operon induction level increases continuously until it reaches its maximum value for very low Ge values. However, when  there is a smooth transition between the uninduced and the induced states as Ge decreases, in agreement with the bifurcation diagram of Fig. 3 E.

there is a smooth transition between the uninduced and the induced states as Ge decreases, in agreement with the bifurcation diagram of Fig. 3 E.

The operon can also be induced by increasing Le, given a fixed Ge value. We see in Fig. 8 A that the lac operon induction is smooth for  that the transition to the induced state is abrupt for

that the transition to the induced state is abrupt for  and that the operon never gets induced if Le ≤ 1000 μM and

and that the operon never gets induced if Le ≤ 1000 μM and  These results are again in agreement with the bifurcation diagram of Fig. 3 E. In particular, the border between the smooth and abrupt transitions to the steady state corresponds to the location of the cusp catastrophe in the Le versus Ge parameter space.

These results are again in agreement with the bifurcation diagram of Fig. 3 E. In particular, the border between the smooth and abrupt transitions to the steady state corresponds to the location of the cusp catastrophe in the Le versus Ge parameter space.

Remarkably, the bacterial growth rate reaches close to maximal values for almost all combinations of Ge and Le values; see Fig. 8 B. The exceptions are the region just right to the border of the monostable induced region (where the value of μ is intermediate), the region of very low Ge and medium to high Le levels (where the μ-value is intermediate as well), and the region of very low Ge and medium to low Le concentrations (in which the growth rate is very close to zero).

CONCLUSIONS

We have improved a previously published model for the lac operon in Escherichia coli. The improvements include: the new model takes into account the interaction between the repressor and its three different binding sites (operators) in a more detailed way; it accounts for the cooperativity between the activator (CAP) and DNA folding; and it considers the fact that the bacterial growth rate depends on the glucose uptake and the lactose metabolism rates.

Except for KA, all the model parameters were estimated from reported experimental data. KA was taken as a free parameter to fit the model results to the experimental data of Ozbudak et al. (16), who reported the (Ge, Le) bifurcation points corresponding to the induction of E. coli's lac operon with TMG. We can see in Fig. 3 A that the bistability region predicted by the model is wider than the experimental one. In our opinion, there are four possible reasons for this discrepancy between the data and the model predictions:

The lac promoter-gfp fusion employed by Ozbudak et al. as a reporter lacks Operators O2 and O3.

Experimentally, it is quite difficult to measure with precision the Le values at which the bistability region starts and ends.

The phase diagram of Fig. 3 A is based upon a mean-field analysis and so, biochemical noise can change the phase boundaries (25).

The estimated parameter values differ from those corresponding to the E. coli strain used by Ozbudak et al.

We explored the parameter space to account for the last possibility, and found that by decreasing parameters ξi and ξij to 20% of their estimated value a much better fit can be obtained (compare to Fig. 3 B). In all the following analysis, we used both parameter sets to test the robustness of the obtained conclusions.

Ozbudak et al. found no evidence of bistability when the natural inducer, lactose, was employed. From their simulations of the lac operon evolution on in silico bacterial populations, van Hoek and Hogeweg (27) proposed that the operon parameters evolve in such a way that bistability is not available for the bacteria when they grow on lactose. Santillán et al. (17) tackled this issue from a mathematical modeling viewpoint and concluded, in opposition to van Hoek and Hogeweg (27), that bistability does not disappear because of lactose metabolism, although it is very hard to identify with the Ozbudak et al. experimental setup.

Since the present model is an improvement and a generalization of the model in Santillán et al. (17), we started by corroborating their results. In Fig. 3, C and D, we can see that with a constant growth rate the current model results are in complete agreement with those of Santillán et al. (17) for the two considered parameter sets. That is, the bistability region moves upwards in the Le versus Ge parameter space, and it disappears in the region of very low Ge values via a cusp catastrophe. Following Santillán et al. (17), we choose the value of φM (which accounts for the maximum lactose-to-allolactose metabolism rate) such that even if Le = 1000 μM, the (Ge, Le) point is very close to the lower border of the bistability region.

Given that a constant growth rate is not realistic under natural conditions, we considered the influence of a variable μ on the bistable behavior of the lac operon. It can be seen in Fig. 3, E and F, that having a μ that depends on the external conditions has no appreciable effect on the lower border of the bistability region. However, the upper border is greatly modified; instead of being nearly constant from moderate to high values of Ge and rapidly decreasing for low Ge levels, as in Fig. 3, C and D, the upper border increases steadily as Ge increases. Furthermore, the cusp catastrophe location moves rightwards, along the Ge axis, when a variable μ is considered.

We also carried out stochastic simulations, considering both a constant and a variable growth rate, to test how feasible the Ozbudak et al. experimental setup is to identify bistability when lactose is the inducer. According to Ozbudak et al., whenever a bimodal distribution is found, it can be considered a proof for bistability. More precisely, having a bimodal distribution is a sufficient but not a necessary condition for this behavior: for instance, if we have large standard deviations, a bimodal distribution will hardly be noticed even is bistability is present. Our numeric experiments confirm that, for the employed φM values, identifying bistability via expression-level distributions is very difficult, regardless of whether a constant or a variable growth rate is considered; compare to Figs. 4–7. It is known that the shot noise resulting from the production of multiple protein copies per mRNA transcript also lowers the switch stability (24) and probably widens the distribution, thus further blurring the bimodal distribution. This could perhaps explain why, in the experiments by Ozbudak et al., only a unimodal distribution was observed in the presence of lactose.

van Hoek and Hogeweg (27) simulated, in silico, the evolution of the lac operon in bacterial populations. According to their results, the parameters that determine the expression of the lac operon genes evolve in such a way that, when the bacterial population is grown in a medium rich in lactose, bistability disappears. Contrarily, when the bacteria grow in the presence of a gratuitous inducer, van Hoek and Hogeweg predict that bistability would be present. They propose that this behavior explains why Ozbudak et al. (16) did not observe bistability when E. coli was grown on lactose. From the results discussed above, we propose a different explanation; namely, that bistability does not disappear when lactose is the employed inducer, but the bistability region in the Le versus Ge parameter space is modified in such a way that this behavior is masked due to the intrinsic noise.

E. coli and other bacteria can feed on both lactose and glucose. However, when they grow in a medium rich in both sugars, glucose is utilized before lactose starts being consumed. This phenomenon, known as diauxic growth (28,29), represents an optimal thermodynamic solution given that glucose is a cheaper energy source than lactose: to take advantage of lactose, the bacteria needs to expend energy in producing the enzymes needed to transport and metabolize this sugar (30).

To test whether the results discussed above are compatible with diauxic growth and, more generally, to better understand the lac operon performance under variable conditions of external lactose and glucose, we calculated the plots in Fig. 8. To do that, the model equations were numerically solved for several values of Ge and Le, with the parameter set of Fig. 3 E, and with the initial condition M = 0 mpb, E = 0 mpb, and L = 0 mpb. This initial condition was chosen so the system reaches the uninduced steady state, unless it does not exist. In this last case, the system evolves toward the induced state.

Consider a bacterial culture growing in a medium containing a mixture of glucose and lactose. We can see from the results in Fig. 8 A (where the operon induction level is plotted versus Ge and Le) that diauxic growth is predicted by the model. That is, induction of the lac operon only occurs when glucose is exhausted. However, it can take place in two different ways: if Le < 500 μM, the cells undergo a smooth transition from the uninduced to the induced state; otherwise, the lac operon shifts abruptly from the off- to the on-state when glucose is almost completely depleted. Why this difference? To answer this question, we carried out numeric experiments in which the lactose operon is induced by changing the bacterial culture from a medium rich in glucose (in which it has been growing for a long time) to a medium with no glucose, while Le is kept constant. Our results (not shown) indicate that it takes >1000 min for the lac operon to become fully induced when Le = 300 μM; while, when Le = 1000 μM, the operon achieves a 97% induction level 300 min after the medium shift. We conclude from these last results that, with a very high external lactose concentration, the lac operon can remain fully uninduced until glucose utilization is almost complete because the response time is short in these conditions.

In principle, it should be possible to induce the lac operon by increasing the Le value. However, the results in Fig. 8 A predict that, if Ge > 60 μM, this is practically impossible for any physiological concentration of external lactose. This can be interpreted as an optimal behavior; if we consider that glucose is a cheaper carbon source, it makes sense to keep the genes in the lactose operon uninduced, as long the energy necessary to grow can be obtained from that sugar. We can also observe from Fig. 8 A that, when 30 μM < Ge < 60 μM, the operon undergoes an abrupt transition to the induced state with high enough levels of Le. However, the induction level only reaches an intermediate value. Finally, if Ge < 30 μM, the operon induction level increases smoothly as Le increases. In this last case, the induction level can get very close to its maximum possible value; a higher value is obtained sooner as Ge decreases. This behavior can also be interpreted as optimal; if the amount of glucose in the growing medium is not enough to support the bacterial population, it is reasonable to allow a continuous increase of the lac-operon induction level as the amount of lactose in the environment increases.

In Fig. 8 B, the bacterial growth rate (calculated under the same conditions as Fig. 8 A) was plotted versus Ge and Le. Remarkably, the value of μ is very close to its maximum almost everywhere; the only exception is the region corresponding to very low levels of Ge and Le. We conclude from this that bistability not only helps to guarantee an efficient switching of the lac operon in E. coli, when feeding on glucose, lactose, or both sugars, but also plays an important role in maintaining a high bacterial growth rate for an extremely wide range of environmental conditions.

The above discussion regarding the influence of lactose metabolism on the bistable behavior of the lac operon relies on the assumption that only the value of parameter φM is affected when the operon is induced with lactose instead of TMG. We know, being that TMG is a weaker inducer, KA should be decreased as well. We investigated the sensitivity of the system bistable behavior to modifications on this parameter and found that the width of the bistability region—in the Le versus Ge parameter-space bifurcation diagram—rapidly decreases as KA diminishes, while its lower boundary remains with little change.

These facts oblige us to reconsider our conclusions. Thus, if the change on KA is small and the bistability region is still quite wide, then all the above stated conclusions hold like that. Otherwise, our results regarding the system behavior when the (Ge, Le) point lies within the bistability region are probably no longer valid. However, not everything is lost because, even then, bistability does not disappear, and the incapability of Ozbudak et al. to observe it can still be explained if the bistability region is so high along the Le axis (due to a very high φM value), that the lac operon never gets induced, except for extremely low Ge values (below the cusp catastrophe).

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Michael C. Mackey for helpful advice, as well as the anonymous referees whose comments and criticisms greatly helped to improve the article.

This research was partially supported by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT, Mexico), and partially carried out while the author was visiting McGill University in December, 2006.

APPENDIX A: MODEL DEVELOPMENT

Interaction of the lac repressor with the operators

The lac repressor is a tetramer, formed by the union of two functional homo-dimers. Each monomer in a repressor can be bound by an allolactose molecule. When all four monomers are free, each dimer can bind any of the lac-operon operators. When one or the two monomers in a dimer are bound by allolactose molecules, it is unable to bind an operator; but the dimer in the opposite side still can do it, provided both their monomers are free. Finally, if either of the two monomers is on an opposite side, or three or all four monomers are bound to allolactose, none of the repressor dimers is capable of binding an operator.

Given that there are six possible configurations in which two repressor monomers are bound by allolactose molecules, and that in two of such configurations both bound monomers belong to the same dimer, we can assume that one-third of the repressors with two occupied monomers are capable of binding an operator. This assumption is supported by the fact that the binding of allolactose to a given monomer is independent of its binding to the other three monomers.

Let R, RA, and R2A, respectively, represent a free repressor, and a repressor bound by one and two allolactose molecules. They can bind an operator, O, according to the following reactions:

|

The dissociation constant of the first reaction (KR/2) is half as large as those of the second and third reactions (KR) because, in a free repressor, both dimers can bind the operator, and therefore the forward reaction rate is twice as large.

Recalling that only one-third of the R2A compounds can bind an operator, the equilibrium equations corresponding to the reactions in the former paragraph are

|

Assume that the total concentration of operators ([OT]) remains constant:

|

Then, it follows after a little algebra that the concentration of free operators is given by

|

(20) |

The binding of allolactose (A) to the lac repressor (R) takes place in four consecutive independent steps as

|

The different factors multiplying the dissociation constants account for the fact that the forward and backward reaction rates are proportional to the number of empty and occupied allolactose binding sites, respectively.

The equilibrium equations for the repressor-allolactose binding reactions are

|

From these and the equation accounting for the conservation of repressor molecules,

|

it follows that [R], [RA], and [R2A] are, respectively, given by

|

(21) |

|

(22) |

|

(23) |

Finally, by substituting Eqs. 21–23 into Eq. 20, we obtain the following expression for the concentration of free operators, in terms of the allolactose concentration,

|

(24) |

with

|

(25) |

DNA folding

Assume that there are two different operators (or lac repressor binding sites) that only allolactose-free repressor molecules can bind, and that DNA can fold in such a way that a single repressor can bind both operators simultaneously. Let O,  O2R, and

O2R, and  respectively, denote the binding states in which both operators are free; the first operator is bound by a repressor and the second is free; only the second operator is bound by a repressor; each operator is bound by a different repressor molecule; and both operators are bound by the same repressor through DNA folding. The chemical reactions standing for all of the transitions between these states are

respectively, denote the binding states in which both operators are free; the first operator is bound by a repressor and the second is free; only the second operator is bound by a repressor; each operator is bound by a different repressor molecule; and both operators are bound by the same repressor through DNA folding. The chemical reactions standing for all of the transitions between these states are

|

The equilibrium equations for these equations are

|

The condition that the total concentration of DNA regulatory regions remains constant is

|

It follows from the last two equations that the probability for both operators to be free is

|

(26) |

where  Similarly, the probability that the first operator is free, regardless of the second operator state, is given by

Similarly, the probability that the first operator is free, regardless of the second operator state, is given by

|

(27) |

To take into account the dependence of these probabilities on the allolactose concentration, we only need to substitute R from Eq. 21.

A more realistic model should take into account the fact that all of the repressors bound by one allolactose, and one-third of those bound by two allolactose molecules, can also bind an operator, although they are unable to simultaneously bind the two operators through DNA folding. To carry out the corresponding analysis, more chemical reactions and their corresponding equilibrium equations must be included, as in the previous subsection. Although not too complicated, the whole process is quite lengthy. Therefore, we omit the details for the sake of brevity and simply give the results. For instance, the probability that both operators are free is given by

|

(28) |

where [R] and [R′] are, respectively, given by Eqs. 21 and 25. Similarly, the probability the first operator is free, regardless of the second operator state, is

|

(29) |

It is not hard to see how these results are a direct generalization of the ones presented in Eqs. 24, 26, and 27.

The three operators of the lac operon

The lactose operon has three different operators, termed O1, O2, and O3. Free lac repressor molecules, as well as those bound by one allolactose, and one-third of those bound by two allolactose molecules, can bind each of these operators with different dissociation constants. Moreover, free repressor molecules can bind any two of such operators simultaneously. Denote the binding state in which all three operators are free by O; the state in which only the ith operator is bound by a repressor by  that in which operators i and j are bound by one repressor each as

that in which operators i and j are bound by one repressor each as  the state in which all three operators are bound by different repressor molecules as O3R; the state in which operators i and j are bound by a single repressor as

the state in which all three operators are bound by different repressor molecules as O3R; the state in which operators i and j are bound by a single repressor as  and that in which operators i and j are bound by a single repressor and operator k is bound by a second repressor as

and that in which operators i and j are bound by a single repressor and operator k is bound by a second repressor as

By following a similar but lengthier process to that outlined in the previous subsections, one can calculate the probabilities associated to all the binding states of this system. Given the very large number of equations involved, and of their concomitant equilibrium equations, we omit the details and give the results directly.

The probability that all three operators are free is

|

(30) |

where P(1, 2, 3) stands for the set of all permutations of 1, 2, 3. The probability that only the operator Oi is occupied by a repressor is

|

(31) |

For the probability that operators Oi and Oj are bound by different repressor molecules, we have

|

(32) |

The probability that all three operators are bound by different repressors is

|

(33) |

The probability of having operators Oi and Oj bound by a single repressor, while the other operator is free, is

|

(34) |

Finally, the probability that operators Oi and Oj are bound by a single repressor, while the third one (Ok) is bound by another repressor, is

|

(35) |

Once again, it is not difficult to see how these results are generalizations of those presented in Eqs. 28 and 29.

Probability of having a polymerase bound to the lac promoter, including catabolite repression

Let P denote a mRNA polymerase molecule. The reaction through which P binds to promoter P1 to form the so-called close complex, PC, is

|

The equilibrium equation for this reaction is

|

Furthermore, the condition for conservation of promoter sites can be written as

|

Finally, it follows from the two former equations that the probability of finding a mRNA polymerase bound to promoter P1 is

|

(36) |

In a similar fashion, the probability that a CAP molecule, C, is bound to its corresponding binding site in the DNA chain, can be calculated as

|

In the absence of cooperativity, the probability that the mRNAP and CAP binding sites are occupied is simply the product of pp and pc. However, since the binding of a CAP molecule to its corresponding binding site enhances the probability that a mRNAP is bound to P1, the probability a polymerase is bound to the promoter, regardless of the state of the CAP binding site, is

|

where kpc > 1 accounts for the cooperativity between the CAP and mRNAP binding sites. After a little algebra, this last equation can be rewritten as

|

(37) |

On the other hand, the probability that a CAP molecule is bound to its corresponding site, regardless of the promoter state, is

|

which can be rewritten as

|

(38) |

Finally, pc must be a decreasing function of [Ge] since external glucose inhibits the synthesis of cAMP, which in turn implies a decrease in C, and thus in pc (this regulatory mechanism is known as catabolite repression). Here we assume that the functional form for pc is given by

|

(39) |

Transcription initiation and mRNA dynamics

Only when Operator O1 is free, can a mRNA polymerase bind the promoter P1 and start transcription. In other words, a polymerase can start transcription in the following operator binding states: O,  and

and

Let [D] denote the concentration of operon copies, and kM the maximum transcription rate of promoter P1. From the discussion in the previous paragraph and the results of the previous subsection, the rate of transcription initiation comes out to be

|

where ppc is given by Eq. 37. Then, from Eqs. 30–35, the rate of transcription initiation can be rewritten as

|

where

|

with  and

and

So far, we have not considered a newly discovered source of cooperativity in the lactose operon of Escherichia coli (19): a CAP molecule bound to its corresponding site not only increases the probability that a polymerase binds the promoter, but also enhances the probability that the DNA folds in such a way that a single repressor binds Operators 1 and 3 simultaneously. To take this second fact into account we assume that the loop involving Operators 1 and 3 can only form if a CAP molecule is bound to its binding site. Consequently, the equation defining  is modified by multiplying the term corresponding to the state

is modified by multiplying the term corresponding to the state  by the probability, pcp, that a CAP molecule is located in its binding site. After doing this, Function

by the probability, pcp, that a CAP molecule is located in its binding site. After doing this, Function  transforms into

transforms into

|

where

|

Let μ and γ, respectively, denote the bacterial growth rate and the mRNA degradation rate. From this, the differential equation governing the mRNA (M) dynamics is

|

(40) |

Enzyme dynamics

Let [E] be the concentration of LacZ polypeptides, and kE be the translation initiation rate of the lacZ mRNA. Since there are no mechanisms involved in the lac operon regulation at the translation level and the degradation rate for the LacZ polypeptides is negligible, as compared to the bacterial growth rate, the polypeptide dynamics are governed by

|

(41) |

Let [Q] and [B] represent the permease and β-galactosidase concentrations, respectively. The translation initiation and degradation rates of lacZ and lacY are slightly different. Here, we assume they are the same for the sake of simplicity. From this and the fact that β-galactosidase is a homo-tetramer made up of four lacZ polypeptides, while permease consists of a single lacY polypeptide, it follows that

|

Lactose and allolactose dynamics

Let Le denote extracellular lactose, L intracellular lactose, and A intracellular allolactose. From the results of Ozbudak et al. (16), in the absence of external glucose the dependence of the normalized inducer uptake rate, per β-permease molecule, on the external inducer concentration is given by

|

The results of Ozbudak et al. (16) also allow us to model the decrease in the inducer uptake rate caused by external glucose (a mechanism known as inducer exclusion) by

|

Then, if kL is the maximum lactose uptake rate per permease, the lactose uptake rate is

|

After being transported into the bacterium, lactose is metabolized by β-galactosidase. Approximately half of the lactose molecules are transformed into allolactose, while the rest are used directly to produce galactose. The lactose-to-allolactose metabolism rate, which as explained above equals the lactose-to-galactose metabolism rate, can be modeled as a Michaelis-Menten function (typical of catalytic reactions)

|

Therefore, the total rate of lactose metabolized per single β-galactosidase is

|

Allolactose and lactose are both metabolized into galactose by the same enzyme: β-galactosidase. Under the assumption that the allolactose production and metabolism rates are much faster than the cell growth rate, we may assume that the these two metabolic processes balance each other almost instantaneously so

|

On the other hand, allolactose is an isomer of lactose, and therefore we can expect that the parameters related to the metabolism kinetics of both sugars attain similar values: φM ≈ φA and κM ≈ κA. Then

|

Finally, from all the above considerations, the differential equation that governs the intracellular lactose dynamics is

|

(42) |

where γL is the lactose degradation rate.

Glucose transport and growth rate

Monod (31) measured the growth rate (μ) of an E. coli bacterial culture in a medium with glucose as the only carbon source as a function of this sugar concentration. He found the following relation:

|

Later Schulze and Lipe (32) demonstrated that the growth rate is proportional to the glucose input rate, JG, and that JG is related to the extracellular glucose concentration via a Michaelis-Menten-like function:

|

(43) |

From these considerations and the fact that after being fully metabolized every lactose molecule produces two glucoselike molecules, we assume that the growth rate of a bacterial culture, growing in a medium containing a mixture of glucose and lactose, is given by

|

(44) |

where  is the rate of glucoselike molecules produced via lactose metabolizing.

is the rate of glucoselike molecules produced via lactose metabolizing.

APPENDIX B: PARAMETER ESTIMATIONS

Since the current model is a generalization of the one introduced in Santillán et al. (17), we took most of the parameter values from the estimations in there. Nevertheless, the way repression is modeled was improved in the current model, and therefore, the corresponding parameters have to be reestimated.

Repression parameters

From the equations in Table 2, the activation of the lac promoter in the absence of external glucose is

|

where

|

The repression capacity ( ) of the lac promoter-operator complex is defined as the ratio of promoter activity levels between the maximally induced and maximally repressed states:

) of the lac promoter-operator complex is defined as the ratio of promoter activity levels between the maximally induced and maximally repressed states:

|

Oehler et al. (33) measured the repression capacity of the wild-type lac operon (which contains all three operators), as well as that of mutant operons in which one and two operators were removed. Their results can be summarized as follows:

|

From its definition, the value of  is completely determined by parameters kpc, pp, ξi, and ξij. Furthermore, the removal of O1, O2, and O3 can be simulated by setting ξ1, ξ12, ξ13 = 0, ξ2, ξ12, ξ23 = 0, and ξ3, ξ13, ξ23 = 0, respectively. Similarly, the removal of O2 and O3 can be accounted for by setting ξ2, ξ3, ξ12, ξ13, and ξ23 = 0. Therefore, if we take the value of kpc estimated in Santillán et al. (17), we can use the results of Oehler et al. to estimate the parameters pp, ξi, and ξij. After carrying out the whole process, we obtained

is completely determined by parameters kpc, pp, ξi, and ξij. Furthermore, the removal of O1, O2, and O3 can be simulated by setting ξ1, ξ12, ξ13 = 0, ξ2, ξ12, ξ23 = 0, and ξ3, ξ13, ξ23 = 0, respectively. Similarly, the removal of O2 and O3 can be accounted for by setting ξ2, ξ3, ξ12, ξ13, and ξ23 = 0. Therefore, if we take the value of kpc estimated in Santillán et al. (17), we can use the results of Oehler et al. to estimate the parameters pp, ξi, and ξij. After carrying out the whole process, we obtained

|

Glucose transport and growth rate parameters

Schulze and Lipe (32) demonstrated that when a bacterial culture has glucose as the only carbon source, the growth rate is proportional to the glucose uptake rate. From their results, the proportionality constant can be estimated as

|

Monod (31) asserts that, for E. coli feeding on glucose, the culture growth rate as a function of the extracellular glucose concentration obeys a Michaelis-Menten function. He also proved that the maximal growth rate is ∼0.23 min−1, and that the glucose concentration for which the growth rate is half-maximal is ∼22 μM. From this and the result in the previous paragraph, we have that

|

with

|

and

|

Editor: Arthur Sherman.

References

- 1.Jacob, F., D. Perrin, C. Sanchez, and J. Monod. 1960. Operon: a group of genes with the expression coordinated by an operator. C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. 250:1727–1729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffith, J. S. 1968. Mathematics of cellular control processes. II. Positive feedback to one gene. J. Theor. Biol. 20:209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rietkerk, M., S. F. Dekker, P. C. de Ruiter, and J. van de Koppel. 2004. Self-organized patchiness and catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Science. 305:1926–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrell, J. E., Jr., and E. M. Machleder. 1998. The biochemical basis of an all-or-none cell fate switch in Xenopus oocytes. Science. 280:895–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagowski, C. P., and J. E. Ferrell. 2001. Bistability in the JNK cascade. Curr. Biol. 11:1176–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhalla, U. S., P. T. Ram, and R. Iyengar. 2002. MAP kinase phosphatase as a locus of flexibility in a mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling network. Science. 297:1018–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross, F. R., V. Archambault, M. Miller, and M. Klovstad. 2002. Testing a mathematical model of the yeast cell cycle. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13:52–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pomerening, J. R., E. D. Sontag, and J. E. Ferrell, Jr. 2003. Building a cell cycle oscillator: hysteresis and bistability in the activation of Cdc2. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagowski, C., J. Besser, C. R. Frey, and J. E. J. J. Ferrell, Jr. 2003. The JNK cascade as a biochemical switch in mammalian cells: ultrasensitive and all-or-none responses. Curr. Biol. 13:315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sha, W., J. Moore, K. Chen, A. D. Lassaletta, C. S. Yi, J. J. Tyson, and J. C. Sible. 2003. Hysteresis drives cell-cycle transitions in Xenopus laevis egg extracts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:975–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubnau, D., and R. Losick. 2006. Bistability in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 61:564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novick, A., and M. Weiner. 1957. Enzyme induction as an all-or-none phenomenon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 43:553–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohn, M., and K. Horibata. 1959. Analysis of the differentiation and of the heterogeneity within a population of Escherichia coli undergoing induced β-galactosidase synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 78:613–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maloney, L., and B. Rotman. 1973. Distribution of suboptimally induced -D-galactosidase in Escherichia coli. The enzyme content of individual cells. J. Mol. Biol. 73:77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung, J. D., and G. Stephanopoulos. 1996. On physiological multiplicity and population heterogeneity of biological systems. Chem. Eng. Sci. 51:1509–1521. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozbudak, E. M., M. Thattai, H. N. Lim, B. I. Shraiman, and A. van Oudenaarden. 2004. Multistability in the lactose utilization network of Escherichia coli. Nature. 427:737–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santillán, M., M. C. Mackey, and E. S. Zeron. 2007. Origin of bistability in the lac operon. Biophys. J. 92:3830–3842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narang, A. 2007. Effect of DNA looping on the induction kinetics of the lac operon. J. Theor. Biol. 247:695–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhlman, T., Z. Zhang, M. H. Saier, and T. Hwa. 2007. Combinatorial transcriptional control of the lactose operon of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:6043–6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strogatz, S. H. 1994. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

- 21.Gillespie, D. T. 2001. Approximate accelerated stochastic simulation of chemically reacting systems. J. Chem. Phys. 115:1716–1733. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillespie, D. T., and L. R. Petzold. 2003. Improved leap-size selection for accelerated stochastic simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 119:8229–8234. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren, P., and P. R. ten Wolde. 2004. Enhancement of the stability of genetic switches by overlapping upstream regulatory domains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92:128101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warren, P., and P. R. ten Wolde. 2005. Chemical models of genetic toggle switches. J. Phys. Chem. B. 109:6812–6823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kepler, T. B., and T. C. Elston. 2001. Stochasticity in transcriptional regulation: origins, consequences, and mathematical representations. Biophys. J. 81:3116–3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert, W., and B. Müller-Hill. 1966. Isolation of the lac repressor. Biophys. J. 56:1891–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Hoek, M. J., and P. Hogeweg. 2006. In silico evolved lac operons exhibit bistability for artificial inducers, but not for lactose. Biophys. J. 91:2833–2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roseman, S., and N. D. Meadow. 1990. Signal transduction by the bacterial phosphotransferase system. J. Biol. Chem. 265:2993–2996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narang, A. 1998. The dynamical analogy between microbial growth on mixtures of substrates and population growth of competing species. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 59:116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dekel, E., and U. Alon. 2005. Optimality and evolutionary tuning of the expression level of a protein. Nature. 436:588–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monod, J. 1949. The growth of bacterial cultures. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 3:371–394. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulze, K. L., and R. S. Lipe. 1964. Relationship between substrate concentration, growth rate, and respiration rate of Escherichia coli in continuous culture. Arch. Mikrobiol. 48:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oehler, S., E. R. Eismann, H. Krämer, and B. Müller-Hill. 1990. The three operators of lac operon cooperate in repression. EMBO J. 9:973–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]