Abstract

Objective

To determine whether an advance directive redesigned to meet most adults’ literacy needs (5th grade reading level with graphics) was more useful for advance care planning than a standard form (>12th grade level).

Methods

We enrolled 205 English and Spanish-speaking patients, aged ≥ 50 years from an urban, general medicine clinic. We randomized participants to review either form. Main outcomes included acceptability and usefulness in advance care planning. Participants then reviewed the alternate form; we assessed form preference and six-month completion rates.

Results

40% of enrolled participants had limited literacy. Compared to the standard form, the redesigned form was rated higher for acceptability and usefulness in care planning, P≤0.03, particularly for limited literacy participants (P for interaction ≤ 0.07). The redesigned form was preferred by 73% of participants. More participants randomized to the redesigned form completed an advance directive at six months (19% vs. 8%, P=0.03); of these, 95% completed the redesigned form.

Conclusions

The redesigned advance directive was rated more acceptable and useful for advance care planning and was preferred over a standard form. It also resulted in higher six month completion rates.

Practice Implications

An advance directive redesigned to meet most adults’ literacy needs may better enable patients to engage in advance care planning.

Keywords: advance directive, health literacy, communication, decision-making, ethics, health disparities

1. INTRODUCTION

Written advance directives have been advocated to document end-of-life treatment wishes, designate surrogate decision makers, and promote discussion regarding treatment wishes.(1) While advance directives are not a panacea for the challenges of advance care planning, and there is controversy concerning their effectiveness, (2-4) they are desired by patients(1, 5) and may stimulate discussions and decrease stress for surrogate decision-makers.(6, 7) In many countries, healthcare organizations are required to provide information about advance directives to patients.(8)

Advance directive completion rates are low, especially among more disadvantaged populations.(9) Standard advance directives may themselves be a barrier to completion and understanding because most forms are written at a 12th grade reading level and contain complex medical and legal terminology.(10) In contrast, half of American adults read at or below an 8th grade level (5th grade or a mid-primary educational level for the elderly)(11) and an estimated 20% of European adults have literacy skills that would prevent them from “learning from text.”(12)

Limited literacy has been associated with impaired information exchange, decision-making, and communication of treatment preferences.(13) The combination of limited literacy and poor advance directive design results in a mismatch that may jeopardize decision-making around end-of-life care. The Institute of Medicine and other organizations have called on the healthcare system to improve access to information to enable patients to actively participate in decision-making. Specific recommendations include writing medical documents at a sixth to eighth grade reading level and designing written documents with an easy-to-follow format and layout.(14)

Methods used to design literacy-appropriate written materials include not only writing the text at a lower reading level, but also designing the materials with an appropriate layout that enhances readability. Therefore, we redesigned a standard advance directive to meet the literacy levels of most elderly adults by writing the text at a 5th grade reading level, i.e. mid-primary educational level. We also incorporated input from the target population(15) and used a clear layout, large 14 point font, appropriate line spacing and margins, and graphics that helped to explain the text.(14, 16-19) These techniques have been shown to improve acceptability(16, 17), activate patients to initiate discussions with providers (17) and, in some cases, enhance understanding.(16, 18, 19) We then conducted a randomized trial to compare the redesigned to a standard form (Figure 1). To our knowledge, no prior studies have assessed an advance directive redesigned in this manner. We hypothesized that participants would rate the redesigned advance directive easier to use and understand, more useful for personal treatment decisions, and more valuable for care planning. Because the hospital in which the redesigned advance directive was to be implemented has a large proportion of Spanish-speaking patients and patients with limited literacy,(20, 21) and because engagement in advance care planning has been shown to be lower in minorities and subjects with lower education,(9, 22-24) we also explored whether the effects of the redesigned form were greater among participants with limited literacy and among Spanish-speakers.

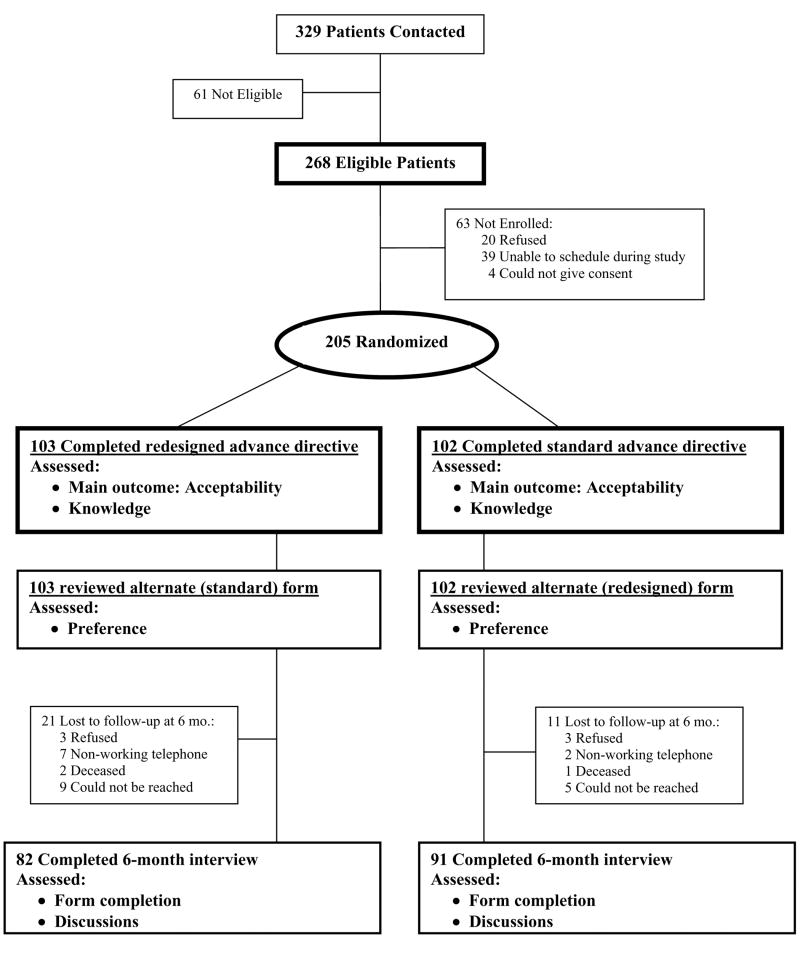

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Diagram

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design

We conducted a randomized trial in the General Medicine Clinic at San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH), a University of California San Francisco (UCSF)-affiliated public hospital. We used an interactive consent process, as previously described. (21) This study was approved by the UCSF-SFGH institutional review boards.

2.2. Study Participants

We recruited a convenience sample between August and December 2004. Primary care clinicians read study fliers to potential participants and referred interested patients. Eligibility criteria included being 50 years or older, reporting fluency in English or Spanish, having a telephone, and having a primary care physician. Physicians did not refer patients who were deaf, acutely ill, or who had dementia. Study staff further excluded participants with corrected visual acuity worse than 20/100.(25)

2.3. Randomization

Literacy level was first assessed with the validated short form Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (s-TOFHLA), a 36-item, timed reading comprehension test in English or Spanish.(26) By convention, scores ≤ 22 (approximately < 9th grade reading level) were defined as limited literacy, and scores > 22 as adequate literacy.(27) Participants were randomized using a random number generator, stratified by literacy level (adequate or limited), to either first review and attempt to complete a standard California advance directive or the redesigned advance directive. Assignment was concealed in opaque envelopes. Research assistants and participants could not be blinded to group assignment.

2.4. Intervention

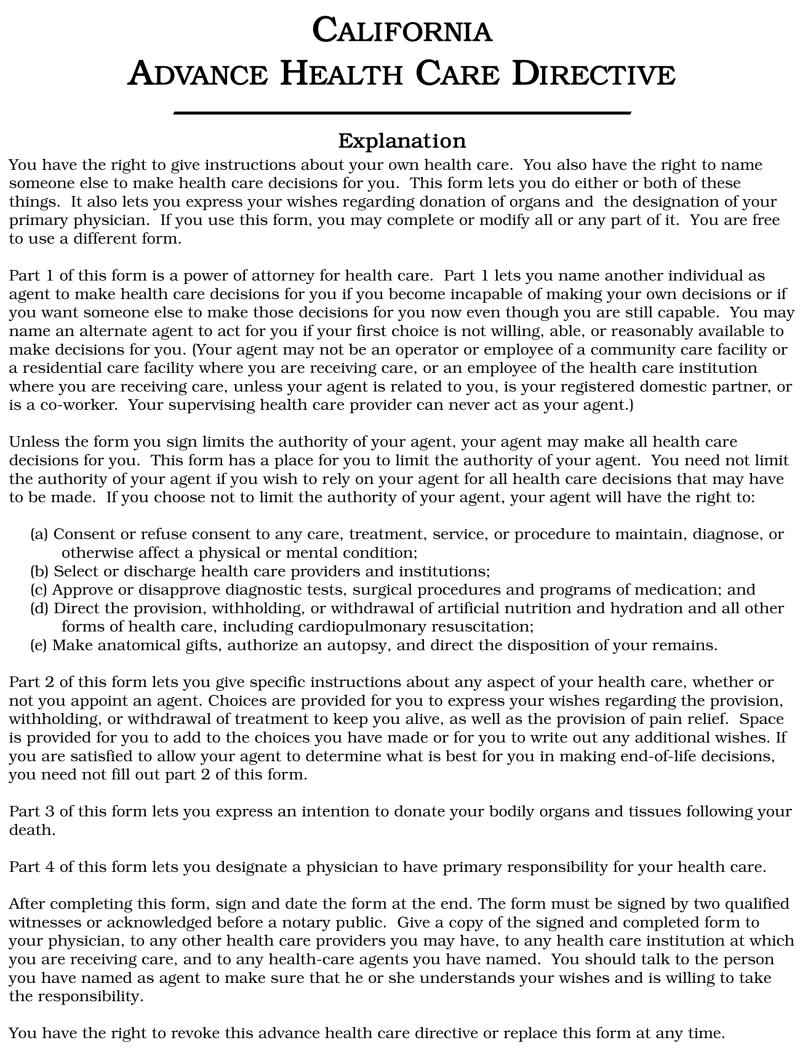

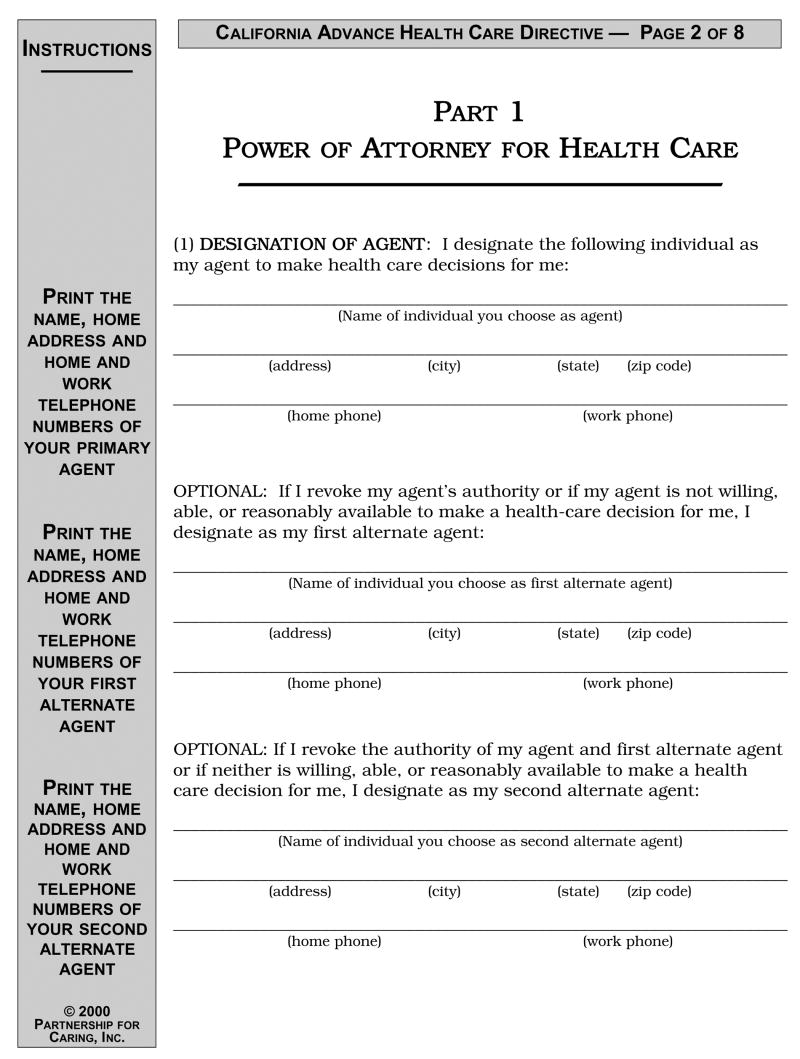

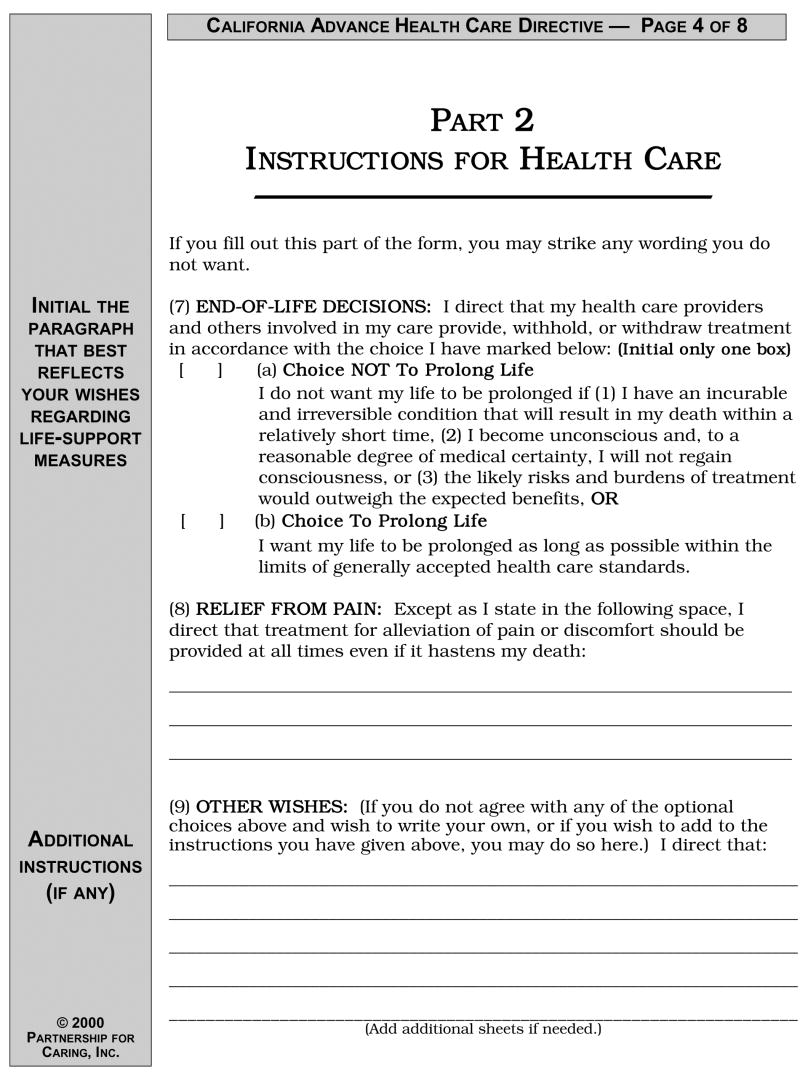

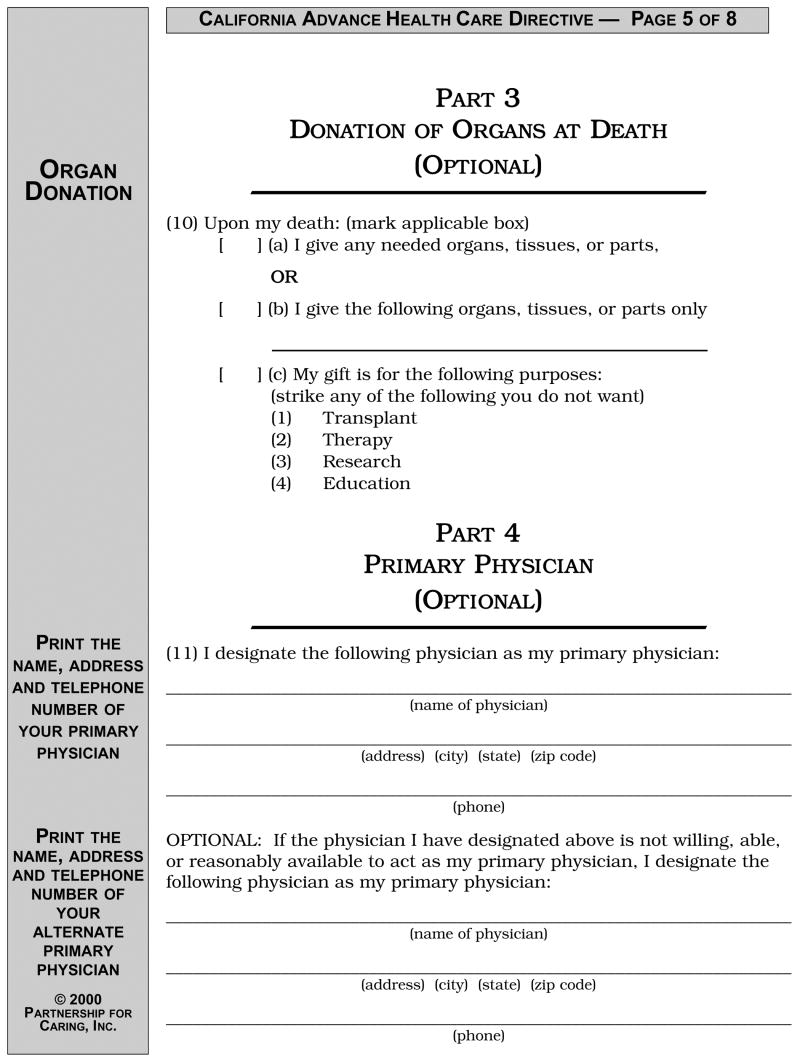

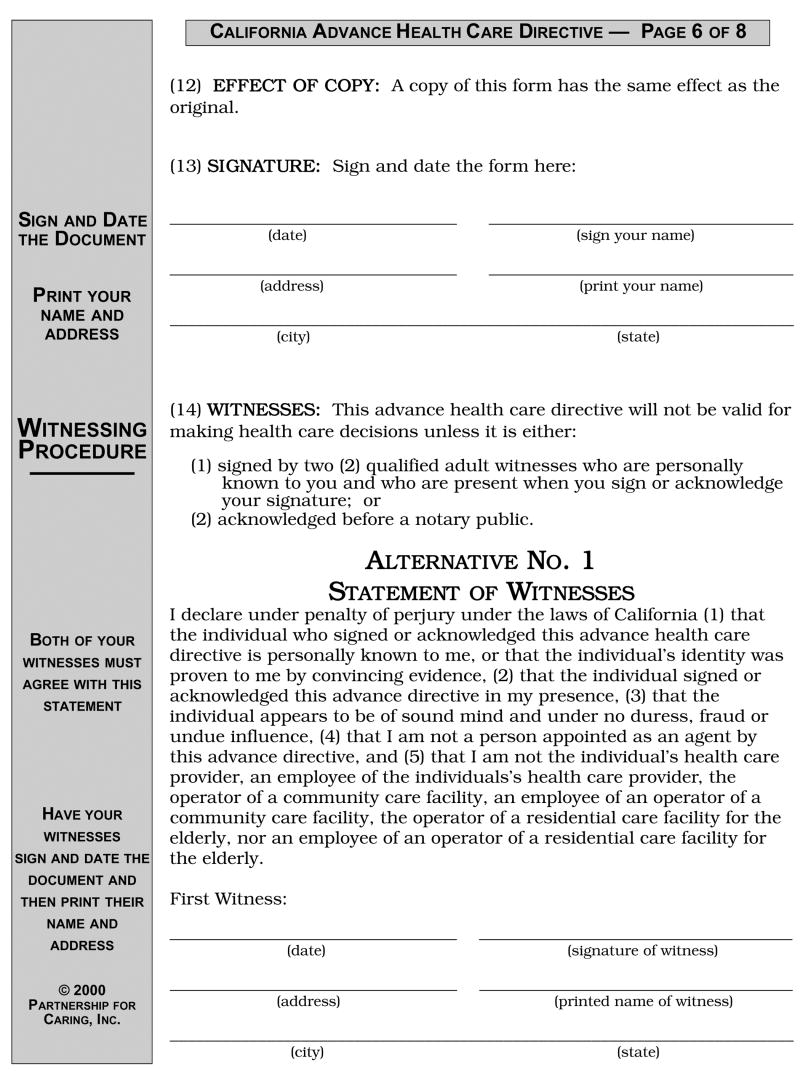

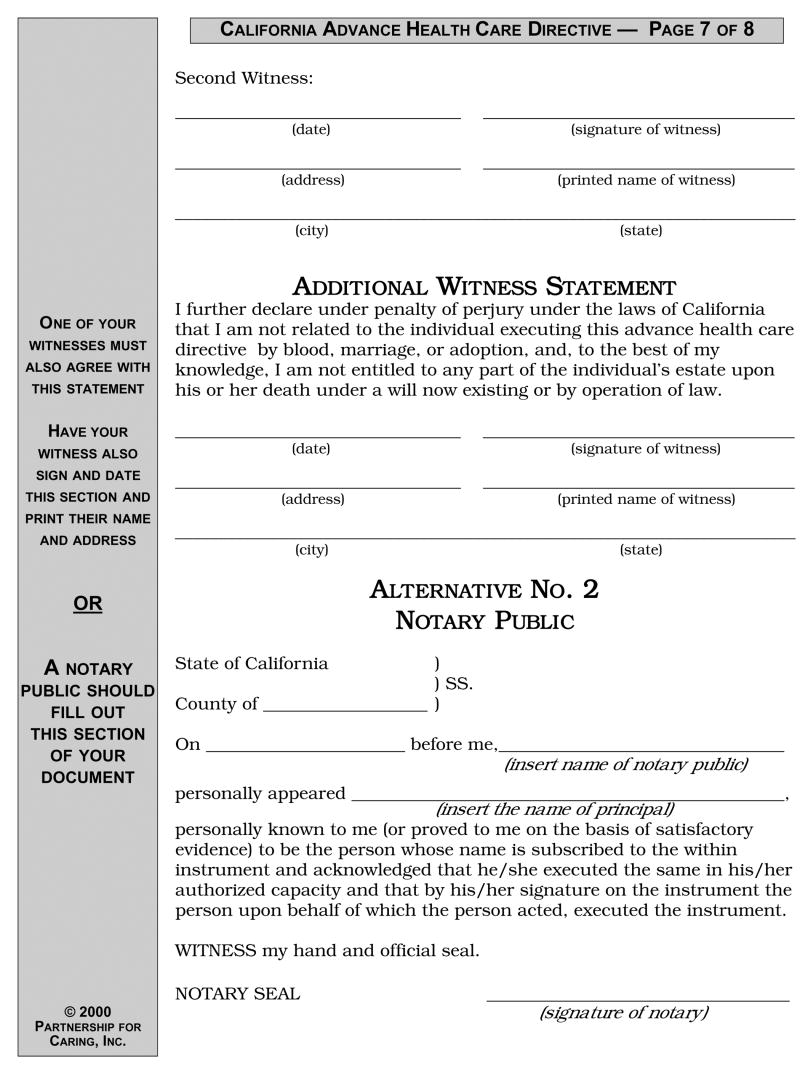

The standard California advance directive is an 8-page document written at a 12th grade reading level using 12-point font size, without color or pictures.(28) The form contains the following advance care planning topics: purpose of advance directives, designation of a power of attorney, preferences for treatment (“choice not to prolong life” or “choice to prolong life”), organ donation, autopsy, and the treatment of pain. The standard form can be accessed at http://www.caringinfo.org. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Standard Advance Directive.

Copyright © 2005 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution by an organization or organized group without the written permission of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization is expressly forbidden. For more information, please visit our web site at www.caringinfo.org.

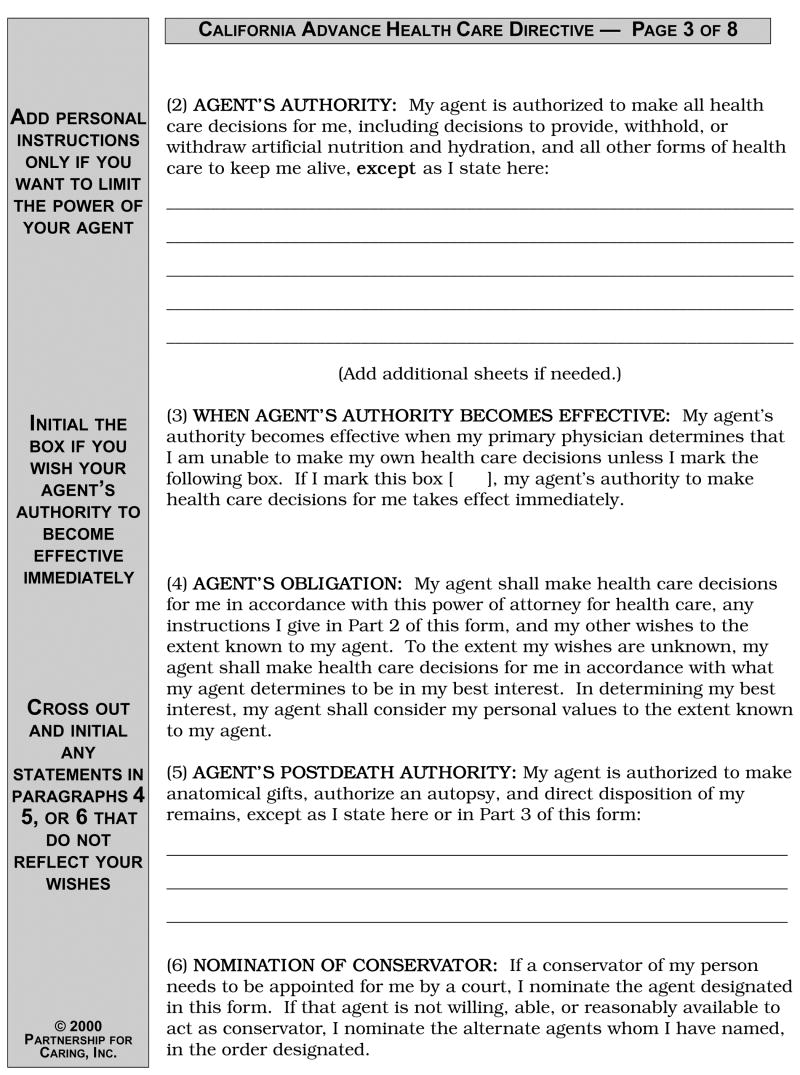

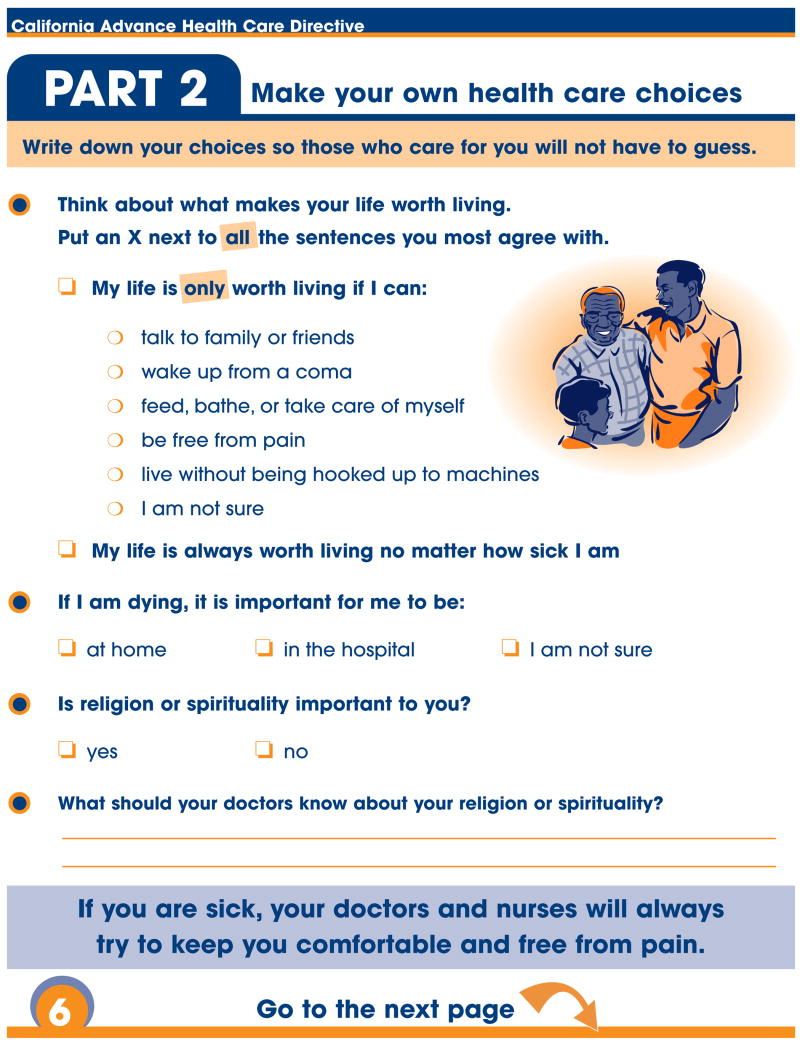

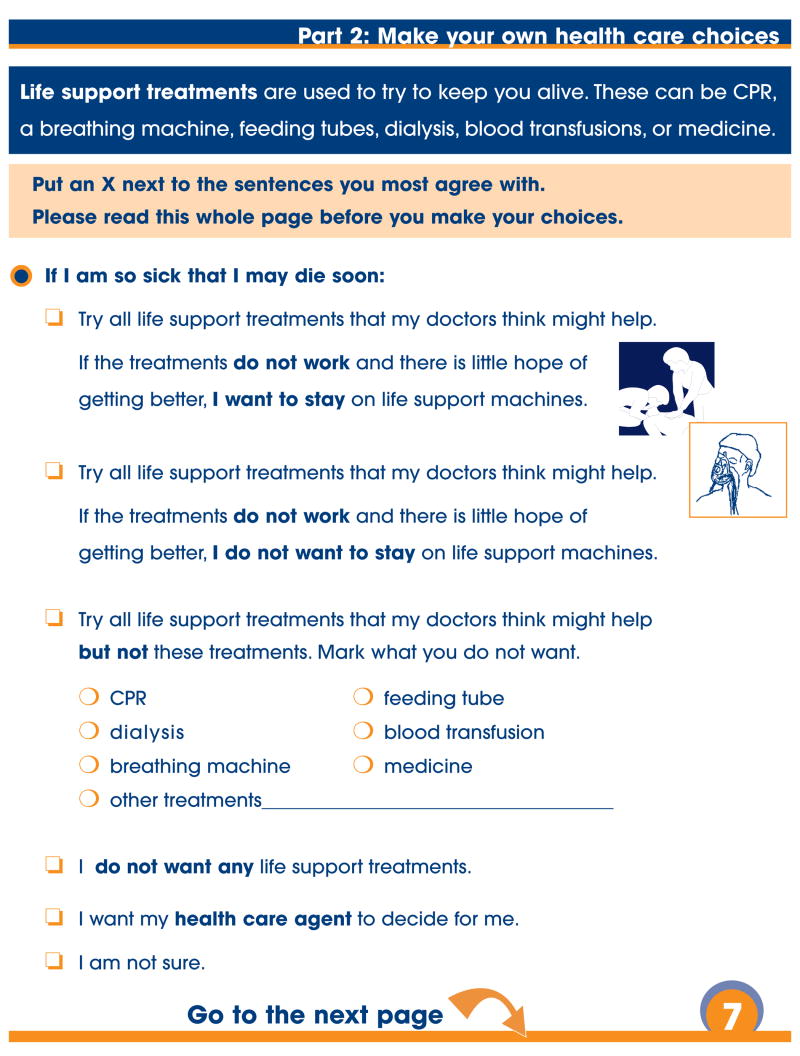

The redesigned advance directive was created through an iterative process with input from patients, nurses, health-educators, social workers, and experts in ethics, literacy, and law.(29) It is a 12-page document using ≥ 14 point font. Most sections are written at a 5th grade reading level as determined by two validated methods (30, 31) and by two independent evaluators. It contains concrete language presented in an organized layout, and includes culturally diverse, text-enhancing graphics.(15-19) It contains the same advance care planning topics as the aforementioned standard form. However, it also contains broader treatment choices, such as providing more options than just to prolong or not to prolong life (the options available in the standard form), but also the options of wanting to prolong life but only for a period of time, being able to refuse certain treatments such as blood transfusions, and having the option of letting the health care agent decide. (Page 7 of the form). Questions about patients’ values were also added to the redesigned form such as what makes someone’s life worth living, where one would like to die, and whether religion or spirituality is important (Page 6 of the form).(32) The form can be accessed at www.iha4health.org. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Copyright, printing, and free download information is available on the Institute for Health Care Advancement’s website at www.iha4health.org.

English and Spanish versions of both forms were provided. Participants were provided up to 30 minutes to review and attempt to complete the advance directive they were first assigned. We performed extensive pilot testing of the redesigned form in 20 subjects, with approximately half having a high school education or less. In pilot testing all subjects were able to complete the redesigned form within 20 minutes. To account for the potential increased complexity of the standard form, we allotted 30 minutes for review of each form. Although subjects could ask questions about advance directives after completing the baseline study interview, no additional follow-up or educational interventions were given to participants beyond the information contained in the study forms. In addition, no educational interventions were directed toward their physicians.

2.5. Measures

Before subjects reviewed the forms, we assessed knowledge of advance directive topics. After reviewing and attempting to complete the first advance directive they were randomly assigned, we assessed subjects’ characteristics, their acceptability with the form, and post-form review knowledge. At the end of the study, subjects were then asked to review the alternative form for at least five and up to 10 minutes, and state which they preferred. Six months later, by telephone interview, we assessed whether subjects filled out an advance directive or had advance care planning discussions.

2.6. Participant Characteristics

During the baseline interview, we obtained self-reported age, race/ethnicity, gender, income, education, primary language (English, Spanish, Other), place of birth (in or outside US), number of years lived in the US, marital status, religiosity, self-rated health status, number of hospitalizations within 2 years, number of self-reported chronic comorbidities, and experience with advance directives. Dementia was assessed with the Mini-Cog.(33)

2.7. Main Outcomes

2.7.1. Acceptability

After reviewing assigned advance directives, participants rated their acceptability with the forms in three domains, (a) ease of use and understanding (nine-item scale), (b) personal usefulness in treatment decisions and discussions (eight-item scale), and (c) general value in advance care planning (six-item scale) (Appendix 2) The response category for each item was “agree” or “disagree.”

2.8. Secondary Outcomes

2.8.1. Knowledge

We also assessed knowledge of advance directive topics (12-item scale) both before and after form review. The response category was “true” or “false.” (Appendix 2) Acceptability and knowledge scale items were adapted from other studies and/or validated scales.(34-39)

2.8.2. Proportion of Advance Directive Completed During Baseline Interview

There were six sections on each advance directive that asked for the same information: designation of a surrogate decision-maker and an alternate, when the surrogate’s authority should become effective, end-of-life treatment preferences, organ donation, and a signature.(28, 29) Forms were assessed as to the proportion of these six sections that participants attempted to fill out. We also assessed the amount of time in minutes it took for subjects to complete each form.

2.8.3. Preference

After reviewing the alternate form, participants stated which they preferred and wanted to take home (“the first form” reviewed, the “second form,” “both,” or “neither”). Subjects who stated a preference were then asked to describe why they preferred a particular form.

2.8.4. Six-month outcomes

Six months after the baseline interview, we assessed whether participants had completed a new advance directive, and if so; “the colorful form with pictures,” (redesigned advance directive) “the black and white form without any pictures” (standard advance directive), “both”, or “another form.” We also assessed whether they had discussions with family, friends, or clinicians about advance directives.

All questionnaires were read verbatim by native English- or Spanish-speaking research assistants. Participants were offered $20 for participation. A random sample of 20 (10%) of interviews were observed (RS) and were found to follow protocol.

2.9. Statistical Methods

With planned enrollment of 120 patients, the study had 80% power to detect a difference in ease of use between the redesigned and standard form of 30% (65 vs. 35%).(17, 40) Enrollment continued to 205 to increase sample size of participants with limited literacy as well as Spanish-speakers.

All bivariate results were assessed using χ2 or Fishers Exact tests and t-tests. Open-ended data concerning form preference were analyzed using thematic content analysis to identify the three most common reasons.(41)

Factor analysis demonstrated that one factor explained 81-85% of the variance for each individual acceptability scale and two factors explained 68% of the variance for knowledge. Kuder-Richardson reliability coefficients were high for all scales (0.75-0.83). Results reflect the percent of acceptability scale items with affirmative or, for knowledge scale, correct responses.

To adjust for participant characteristics that significantly differed between randomization groups (P<0.05), we performed analysis of co-variance for each scale outcome. Post-form review knowledge results were additionally adjusted for subjects’ baseline knowledge score.

We also compared the proportion, completed per individual, of the six sections on each advance directive that asked for similar information. We estimated risk differences and 95% confidence intervals of the completion of the forms using a generalized linear model for binomial outcomes and adjusting for clustering within individuals.

We hypothesized that acceptability outcomes might differ by literacy and language because lower education and minority status have been associated with low advance directive completion rates (9, 22-24) In addition, prior to this study, literacy and language appropriate advance directives with culturally diverse, text-enhancing graphics were not available. Therefore, we hypothesized that the greatest gains in the acceptability outcomes may be found in Spanish-speakers and subjects with limited literacy as these subjects may not have been previously exposed to an advance directive they could read or understand. For each acceptability scale we assessed for interactions between randomization group and the pre-specified subgroups of literacy and language by adding an interaction term to our regression models and presenting stratified analyses (P for interaction ≤ 0.05 considered significant).

For analysis of the completion of an advance directive at six months, we also stratified our results by subjects who had previously filled out an advance directive prior to study enrollment and subjects who had never completed an advance directive. For all outcomes, we also performed sensitivity analysis excluding participants who screened positive for dementia. For the six month outcomes, we performed sensitivity analysis including all subjects who were lost to follow-up at six months. All analyses used intercooled STATA, version 9.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Enrollment and Exclusions

Research assistants contacted 329 potentially eligible participants and identified 268 as eligible. Of these, 205 agreed to participate; 103 were assigned to the redesigned form and 102 to the standard form. All enrolled participants reviewed the alternate form at the end of the baseline interview. Figure 1 shows reasons for non-participation.

3.2. Baseline Characteristics

Mean literacy score was 24.6, standard deviation ± 10.8 (approximately the 9th -10th grade). Assignment groups were similar in most sociodemographic characteristics, health status, literacy, and baseline knowledge of advance directive topics (Table 1). Compared to the standard advance directive, participants assigned to the redesigned form were younger (mean years, 59.4 vs. 61.9, P =0.03) and fewer had helped another person complete an advance directive (11% vs. 21%, P=0.05). Overall, 13% (n=26) had previously completed an advance directive. Compared to participants who had not completed an advance directive, these 26 participants were more likely to be white (28% vs. 10%, P=.003), to have had a high school education or greater versus less education (19% vs. 7%, P=.06), and to have adequate rather than limited literacy (19% vs. 8%, P=.06).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Randomization Group

| Characteristic | Redesigned * (n=103)

(n) percent or mean (SD) |

Standard* (n=102)

(n) percent or mean (SD) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 59.4 (8.1) | 61.9 (9.0) | .03 |

| Race | |||

| White, Non-Hispanic | (30) 29.1 | (22) 21.6 | |

| White, Hispanic | (34) 33.0 | (30) 29.4 | |

| Black | (21) 20.4 | (28) 27.5 | .45 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | (10) 9.7 | (9) 8.8 | |

| Native American/Multi-ethnic/Other | (8) 7.8 | (13) 12.7 | |

| Gender: Female | (51) 49.5 | (57) 55.9 | .36 |

| Income: ≤ $10,000† | (36) 43.4 | (46) 53.5 | .19 |

| Education | |||

| College or graduate degree | (19) 18.6 | (15) 14.7 | |

| Some college | (33) 32.4 | (33) 32.4 | .83 |

| High School | (20) 19.6 | (19) 18.6 | |

| < High School | (30) 29.4 | (35) 34.3 | |

| Mean years of education (SD) | 12.2 (4.6) | 12.0 (5.6) | .78 |

| Literacy‡ | |||

| Limited Literacy | (41) 39.8 | (41) 40.2 | .96 |

| Mean Literacy score (SD) | 25.0 (10.2) | 24.5 (11.2) | .72 |

| Language most comfortable speaking | |||

| English | (60) 58.2 | (67) 65.7 | |

| Spanish | (32) 31.1 | (28) 27.4 | .46 |

| Other§ | (11) 10.7 | (7) 6.9 | |

| US born | (57) 55.3 | (66) 64.7 | .17 |

| If not US born, years lived in US (SD) | 24.3 (11.9) | 24.8 (11.6) | .88 |

| Married | (34) 33.3 | (39) 38.6 | .43 |

| Religious (very or extremely) | (44) 43.1 | (49) 48.0 | .48 |

| Health Status | |||

| Fair to Poor self-rated health | (71) 68.9 | (70) 68.6 | .96 |

| Mean number of hospitalizations (SD) | 1.2 (1.4) | 1.2 (2.8) | .97 |

| Mean number of co-morbidities (SD) | 2.8 (1.4) | 2.9 (1.4) | .70 |

| Dementia∥ | (3) 3.0 | (4) 4.0 | .83 |

| Ever Filled out Advance Directive | (14) 13.6 | (12) 11.8 | .69 |

| Ever Helped other fill out Advance Directive | (11) 10.7 | (21) 20.6 | .05 |

| Knowledge of Advance Directive Topics** | 58.5 | 62.2 | .34 |

“Redesigned” is the advance directive written at a 5th grade reading level and containing culturally appropriate graphics. “Standard” is the standard California advance health care directive written at a 12th grade reading level.

Income data only available for 169 (82%) participants

Literacy was assessed using the Short Form test of Functional Literacy in Adults (s-TOFHLA), a 36-item, timed reading comprehension test. Participants with scores ≤ 22 were considered to have “limited literacy”.

Participants in the “Other” category reported speaking English “well” or “very well,” but were most comfortable speaking their native language (e.g. Cantonese, Tagalog, etc.)

As assessed by the Mini-Cog

The overall percentage of 12 factual items about advance directives answered correctly

3.3. Main Outcomes

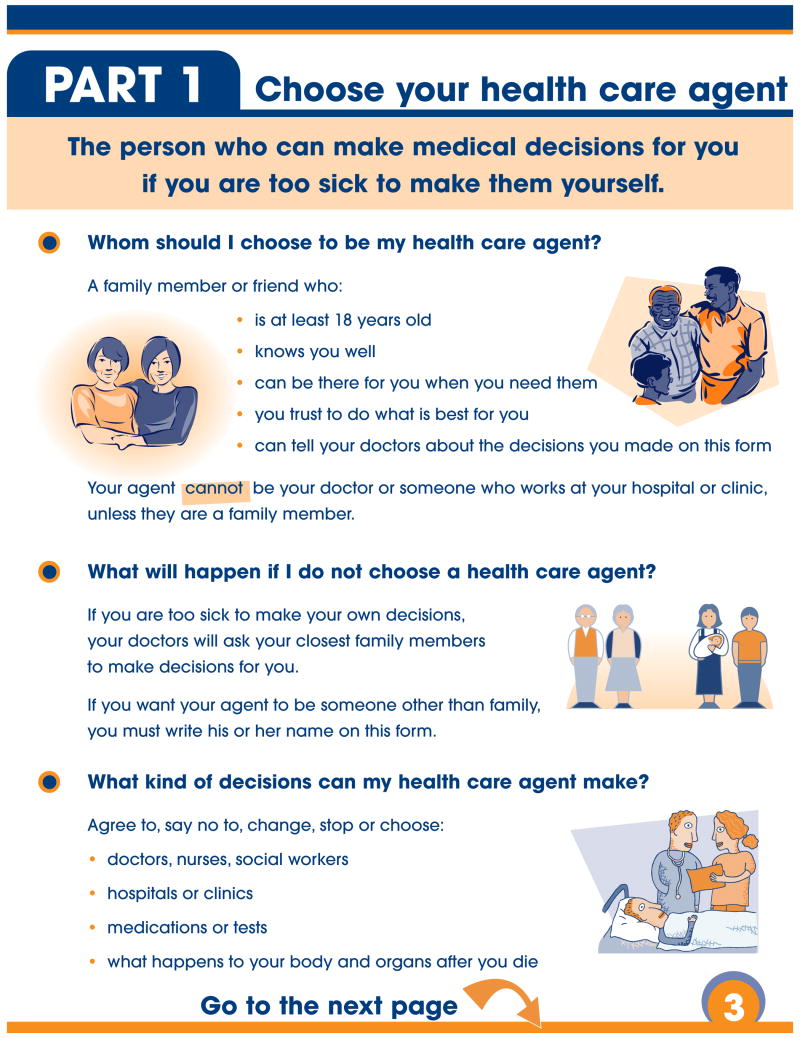

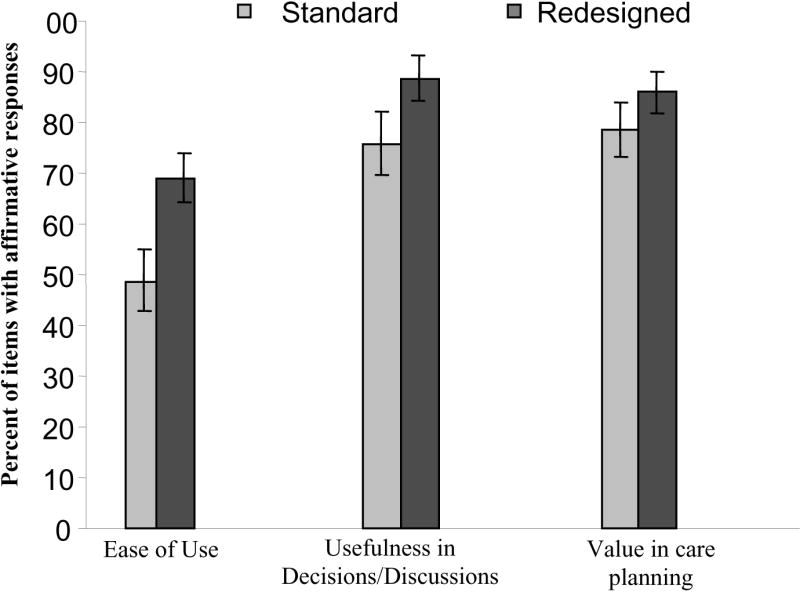

Participants assigned to the redesigned versus the standard advance directive reported higher ratings for all acceptability measures: “ease of use and understanding” (69.1% vs. 48.7%, P<0.001), “personal usefulness in treatment decisions and discussions” (88.6% vs. 75.9%, P=0.001), and “general value in care planning” (86.0% vs. 79.0%, P=0.03) (Figure 4). Results were unchanged after adjusting for age and prior history of helping another person fill out an advance directive form (the two patient characteristics that significantly differed between randomization groups).

Figure 4. Participant Ratings of Acceptability with the Redesigned and Standard Advance Directives.

Participants assigned to the redesigned advance directive are indicated by the dark gray bar and the standard advance directive by the light gray bar. Participants rated their acceptability with the forms in three ways: ease of use and understanding (nine items) (P<0.001), personal usefulness in decisions and discussions (eight items) (P=0.001), and general value in care planning (six items) (P=0.03). The rating is the percent of items in which participants rated the advance directive favorably. Results are adjusted for age and prior history of helping another person fill out an advance directive, and 95% confidence intervals are depicted with error bars.

Among participants with limited literacy, all acceptability measures were rated significantly higher by those randomized to the redesigned versus the standard form (P<0.03) (Table 2). This was also true for English-speakers. Participants with adequate literacy randomized to the redesigned form only rated ease of use and understanding significantly higher (P <0.01). This was also true for Spanish-speakers. The interaction between literacy and group assignment was significant for ease of use and understanding, (P=0.008) value in care planning (P=0.03) and was borderline for usefulness in decisions and discussions (P=0.07) There were no interactions between language and group assignment.

Table 2.

Table 2: Acceptability with Advance Directives, Stratified by Literacy and Language

| Ease of Use & Understanding nine items | Usefulness in Decisions/Discussions eight items | Value in Care Planning six items | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomization | Randomization | Randomization | ||||||||||

| Redesigned percent* | Standard percent | P† | P-I‡ | Redesigned percent | Standard percent | P† | P-I‡ | Redesigned percent | Standard percent | P† | P-I‡ | |

| Literacy | ||||||||||||

| Limited | 65.2 | 32.8 | <.001 | .008 | 86.6 | 65.2 | .003 | .07 | 87.9 | 71.5 | .01 | .03 |

| Adequate | 71.5 | 59.2 | .008 | 90.0 | 83.0 | .11 | 84.7 | 83.3 | .73 | |||

| Language | ||||||||||||

| Spanish | 70.3 | 48.7 | .002 | .86 | 90.2 | 83.3 | .25 | .37 | 87.6 | 86.4 | .81 | .28 |

| English | 68.6 | 48.7 | <.001 | 87.9 | 73.2 | .003 | 85.2 | 75.8 | .03 | |||

Numbers reflect percent of scale items with affirmative responses

Represent the P-value calculated between groups, adjusted for age and prior history of helping another person fill out an advance directive.

P for Interaction assessed the interaction between literacy and randomization and language and randomization for each outcome

- Participants with limited literacy assigned to redesigned advance directive, n= 41 and assigned to the standard, n= 41

- Participants with adequate literacy assigned to redesigned advance directive, n=62 and assigned to the standard, n=61

- Spanish-speaking participants assigned to redesigned advance directive, n=33 and assigned to the standard, n=27

- English-speaking participants assigned to redesigned advance directive, n=70 and assigned to the standard, n=75

3.4. Knowledge and Proportion of Form Completion During Interview

After reviewing the first form they were assigned, participants correctly answered a similar number of knowledge items about advance directives (71.2%, redesigned vs. 70.8%, standard form, adjusted P=0.30). However, participants assigned to review and attempt to complete the redesigned versus the standard advance directive were able to complete a greater proportion of the form (61% vs. 47%, absolute difference 11%; 95% confidence interval, 1.0-21.0, P=0.04). Subjects spent a comparable amount of time to review and complete both the redesigned form (17.2 minutes ±6.5) and the standard form (18.8 minutes ±7.7, P=.13, P=0.13).

3.5. Preference

More participants preferred and wanted to take home the redesigned (n=149, 73%) rather than the standard advance directive (n=35, 17%), or had no preference (n=21, 10%) (Odds ratio of preferring the redesigned vs. standard, 4.25; 95% confidence interval, 2.93 to 6.34). There were no differences in preference for the redesigned form by group assignment, literacy, or language, P>0.05. The most common reasons for preferring the redesigned form were: it was easy to understand and fill out (78.0%), it contained pictures (39.0%) and used larger font and an organized layout (35.5%) (both of which helped participants better understand the text), and that it was less “scary” or intimidating to review and complete (21%).

3.6. Six-month outcomes

Follow-up interviews were completed for 173 (84%) of participants. (Figure 1) Twenty one (20.4%) from the redesigned and 11 (10.8%) from the standard group were lost to follow-up (P=.06). For one participant who followed-up at six months, data were missing concerning whether they had filled out an advance directive. Therefore, among participants in the redesigned advance directive group, 15 out of 81 (18.5%) reported filling out a new advance directive, compared to 7 out of 91 (7.7%) in the standard group, P=0.03. In sensitivity analysis, assuming all subjects who were lost to follow-up or had missing data did not fill out an advance directive, 15 out of 205 (15%) randomized to the redesigned form filled out and advance directive, compared to 7 out of 205 (7%) in the standard group, P=.08. Of 22 participants who filled out a new advance directive, 19 (86.4%) filled out the redesigned, 2 (9.1%) both, and 1 (4.6%) the standard advance directive. No significant differences were observed for discussions about advance directives.

One hundred and forty six participants who followed up at six months had never filled out an advance directive. Among the 146 who were assigned to the redesigned advance directive group, 16% reported filling out a new advance directive versus 5% of those assigned to the standard form, P=.02. Among the 26 participants who had filled out an advance directive prior to study enrollment, there were no differences in advance directive completion by form assignment (29% redesigned group vs. 25% standard group, P=.60). Of the 15 participants who filled out a new advance directive at six months, 13 (87%) filled out the redesigned form and 2 (13%) filled out both advance directives. Of the seven participants who had a previous advance directive but filled out a new advance directive at six months, six (86%) filled out the redesigned form and one (14%) filled out the standard form.

Seven participants (3%) screened positive for dementia; excluding them from the analyses did not appreciably change our results.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

4.1. Discussion

Given the prevalence of limited literacy, many patients may be given advance directives they cannot act on or understand. This may impede patients’ ability to make or articulate treatment preferences, and may threaten informed decision-making around end-of-life care. This study assessed an advance directive redesigned to an appropriate reading level (5th grade) with a clear layout and the inclusion of graphics. Compared to the standard form, the redesigned advance directive was rated easier to use and understand, more useful in treatment decisions and discussions, and of greater value in advance care planning. These effects were observed for all participants, but particularly for participants with limited literacy.

Consistent with other studies of health materials (17, 40), participants in our study overwhelmingly preferred the redesigned advance directive regardless of literacy level or language spoken. Importantly, participants assigned to review the redesigned form were more likely to complete an advance directive at six months. While all participants had exposure to both forms, nearly all participants who filled out an advance directive chose to complete the redesigned form. Subjects who had completed an advance directive before the study were mostly white, well educated, and had adequate literacy. The remaining subjects, who were less well educated and more likely to have limited literacy, filled out the redesigned form more often than the standard form at six months. These results suggest that at least some of the effects of the redesigned form may be due to the literacy appropriate format.

Although knowledge about advance directive topics was improved overall, the redesigned form did not result in greater knowledge gains. Prior studies have found that knowledge does not differentially improve when health materials are written at a lower literacy level.(40) Nevertheless, similar knowledge improvement in both groups should allay concerns that important information may be lost when documents are written in a literacy-appropriate format. It is important to note that we did not provide formal education concerning the advance directive or the advance directive topics. It may be that patients with lower literacy need additional assistance interpreting content, regardless of the low literacy design. The redesigned advance directive, however, was not designed to be used in isolation, but rather to be used as an advanced care planning tool that patients, family and physicians can use together. In addition, most subjects, regardless of literacy, preferred the redesigned advance directive because they felt it was easier to understand and less intimidating, suggesting that the redesigned form may be more useful in clinical practice than standard forms. While some advance directive interventions have resulted in increased discussions with family, in the absence of extensive education, most have no effect on discussions with physicians.(7) Limited time with physicians may explain the lack of effect for this outcome.(42) The short follow-up time, enrolling general medicine vs. terminally ill patients, lack of additional education, and not embedding the advance directive intervention within clinical practice, may each have hindered our ability to detect discussions with family or physicians in our study.

Our study has several limitations. First, generalizability is limited as the redesigned form was compared with one other advance directive, and the study was conducted at an urban county hospital with general medicine patients. Selecting more terminally ill participants may have resulted in more robust effects. Second, our sample size was modest, with potentially inadequate power to detect significant differences in all subgroup and sensitivity analyses. Third, research assistants were not blinded to randomization status, possibly introducing measurement bias. Fourth, we measured advance directive completion at six months by self-report, possibly introducing recall bias. Fifth, our study was not designed to test the redesigned form in actual practice, insofar as our protocol specifically restricted additional education beyond that provided within the forms. That we observed effects on six-month completion rates suggests that the effects of embedding the redesigned advance directive into practice may be even greater. Finally, while the form was written at a more appropriate reading level, it is possible that the effects of the redesigned form may have also been due to the attention to layout, the inclusion of graphics and questions concerning values clarification, and the offering of a range of treatment preferences. The standard form was already in use at SFGH and therefore we could not change its structure. In addition, given results from pilot testing and data from the advance care planning literature, we felt obliged to include the values clarification section and to expand potential treatment options in the redesigned form. Because more than one change was made, we were not able to disentangle the individual contributions of each change to the overall benefit of the redesigned form.

4.2. Conclusion

An advance directive redesigned to an appropriate reading level (5th grade) with a clear layout and the inclusion of culturally diverse, text-enhancing graphics with expanded values clarification and treatment preferences sections, when compared to a standard form, was rated easier to use and understand, and rated higher for personal usefulness in treatment decisions and discussions and for general value in advance care planning, particularly among participants with limited literacy. Participants were able to complete a greater proportion of the redesigned advance directive form and overwhelmingly preferred it over the standard form, regardless of literacy or language. Advance directive completion rates nearly doubled from baseline, with almost all participants filling out the redesigned form. A redesigned advance directive may enable a greater proportion of patients to actively engage in end-of-life decision-making. Redesigning advance directives may be an important step in the effort to transform the healthcare system to better meet the literacy levels of most patients.

4.3. Practice Implications

Much controversy exists about the effectiveness of advance directives. However, providing information that is non-intimidating, acceptable and useful in guiding decisions may be an important step in enabling patients to make and communicate end-of-life treatment choices, especially given the time-limited encounters with clinicians and the lack of resources for extensive interventions at most healthcare institutions. Although the healthcare system places high literacy demands on patients, our study demonstrates that adapting the healthcare system to better meet the literacy needs of the target population, such as the redesigned form, can lead to improved decision making and clinical outcomes for a broad range of patients.(14, 43) While health systems may not be able to adopt the redesigned advance directive verbatim due to local policies, the components of our redesigned form with respect to its literacy level, layout, and inclusion of culturally diverse, text-enhancing graphics, values clarification and expanded treatment preferences may serve as a template for future development of end-of-life decision support tools.

Advance planning and end-of-life decision-making is a process that can and should take time, often requiring multiple discussions, and enhanced written materials cannot replace good oral communication with providers.(44) The redesigned advance directive should not be used in isolation or as a substitute for good communication. Rather, we believe it can augment often time-limited discussions and enable more patients to be active participants in the decision-making process.(45)

Acknowledgments

The standard California advance directive has been copyrighted © in 2005 by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution by an organization or organized group without the written permission of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization is expressly forbidden. For more information, please visit our web site at www.caringinfo.org. Permission for publication of the standard California advance directive was given by the NHPCO National Initiatives and Programs Director. We also acknowledge the Institute for Health Care Advancement who offers the redesigned advance directive for free download from their website in English, Spanish, Chinese, and Vietnamese (www.iha4health.org).

Funding/Support: Dr. Sudore and this trial were supported by the Health Services Research Enhancement Award Program, San Francisco Veterans Administration Medical Center; Division of Geriatrics, University of California, San Francisco; the American Medical Association Foundation; the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging K07 AG000912; the National Institutes of Health Research Training in Geriatric Medicine Grant: AG000212; the Pfizer Fellowship in Clear Health Communication; and the NIH Diversity Investigator Supplement 5R01AG023626-02. Dr. Schillinger was supported by a NIH Mentored Clinical Scientist Award K-23 RR16539.

Appendix

Appendix 2.

Individual scale items for Acceptability and Knowledge, by Redesigned vs. the Standard Advance Directive*

| Scales | Redesigned

n=103 percent |

Standard

n=102 percent |

P-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ease of Use and Understanding | ||||

| This form is easy to complete. | 71.6 | 51.0 | .003 | |

| This form is easy to understand. | 83.3 | 57.8 | <.001 | |

| You feel comfortable filling out this form. | 69.6 | 57.8 | .08 | |

| This form does not make you nervous or anxious. | 72.6 | 57.8 | .03 | |

| You like this form. | 75.5 | 47.1 | <.001 | |

| If your doctor gave you this advance directive, you would fill out the entire form. | 91.2 | 77.2 | .006 | |

| You understand all of the words on this form. | 60.2 | 41.2 | .006 | |

| Other patients will understand all of the words on this form. | 18.5 | 2.9 | <.001 | |

| This form has just the right amount of information. | 76.5 | 48.0 | <.001 | |

|

| ||||

| Usefulness in treatment decisions and discussions |

Redesigned

n=103 percent |

Standard

n=102 percent |

P-value* | |

|

| ||||

| If you were to become very sick: | ||||

| This form would help you talk to your doctor about the kind of medical care you would want. | 92.2 | 82.4 | .04 | |

| This form would help you talk to your family or friends about the kind of medical care you would want. | 90.2 | 79.4 | .03 | |

| Filling out this form would make you feel more confident that you would get the kind of medical care you want. | 92.2 | 79.4 | .009 | |

| After seeing this form, you now feel more confident in making decisions about the type of medical care you might want. | 82.4 | 71.6 | .07 | |

| If your doctor told you that you have a serious illness that does not have a cure: | ||||

| This form would make it easy to choose a family member or friend to help make medical decisions for you. | 87.4 | 69.6 | .002 | |

| This form would make it easy to choose the type of medical care you would want at the end of your life | 83.5 | 65.7 | .003 | |

| This form would help you tell your doctor about the type of medical care that is important to you at the end of your life | 88.4 | 79.4 | .08 | |

| This form would help you tell your family and friends about the type of medical care that is important to you at the end of your life | 93.2 | 79.4 | .004 | |

|

| ||||

| General value in advance care planning |

Redesigned

n=103 percent |

Standard

n=102 percent |

P-value* | |

|

| ||||

| The information in this form is important for people to know about. | 95.1 | 94.1 | .77 | |

| Filling out this form would make you less worried about your future medical care. | 78.4 | 74.5 | .51 | |

| With a form like this you could trust your doctors to give you the kind of medical care that you want even if your doctors were to disagree with your wishes. | 86.3 | 75.5 | .05 | |

| Filling out this form is a good way for you to tell your doctors about the kind of medical care you want. | 94.1 | 84.3 | .02 | |

| This form talks about all of the things that are important to you about your future medical care. | 71.6 | 64.7 | .29 | |

| This form will relieve the burden your family or friends may have if they need to make medical decisions for you. | 91.3 | 78.4 | .01 | |

|

| ||||

| Knowledge Items [0-12]: Pre to post form review‡ | Redesigned n=103 percent | Standard n=102 percent | P-value* | |

|

| ||||

| You can choose someone now to make your medical decisions for you in the future in case you become too sick to make decisions for yourself (true) | pre | 84.4 | 82.4 | .37 |

| post | 89.3 | 88.2 | ||

| An advance directive form would allow you to give your money or property to another person if you were sick or dying (false) | pre | 38.8 | 43.1 | .43 |

| post | 43.7 | 43.1 | ||

| This hospital does not have any forms that would let you write down your choices for medical care if you become very sick (false) | pre | 42.7 | 38.2 | .04 |

| post | 52.4 | 61.8 | ||

| Only your doctor can make medical decisions for you if you become too sick to make your own decisions (false) | pre | 60.2 | 60.8 | .33 |

| post | 68.0 | 63.7 | ||

| A health care agent, or the person who has the power of attorney for health care, can make medical decisions for you in case you become too sick to make them yourself. (true) | pre | 70.8 | 75.7 | .43 |

| post | 72.8 | 82.4 | ||

| An advance directive form lets you write down the type of medical care that you do not want. (true) | pre | 50.5 | 55.9 | .06 |

| post | 82.5 | 75.5 | ||

| An advance directive form lets you choose someone to make medical decisions for you in case you become too sick to make them yourself (true) | pre | 76.7 | 78.4 | .59 |

| post | 89.3 | 89.2 | ||

| An advance directive form lets you write down the type of medical care you want from your doctors in case you become too sick to tell them yourself. (true) | pre | 68.0 | 74.5 | .09 |

| post | 89.3 | 83.3 | ||

| When you write the name of a person to make medical decisions for you on an advance directive form, you give up the power to make your own medical decisions. (false) | pre | 42.7 | 49.0 | .27 |

| post | 55.3 | 53.9 | ||

| Your doctor can change the decisions that you make on the advance directive form if they do not agree with your decisions (false) | pre | 64.1 | 69.6 | .11 |

| post | 75.7 | 74.5 | ||

| A health care agent or the person who has power of attorney for health care is a person who is assigned to have power over your money and property. (false) | pre | 43.7 | 51.0 | .07 |

| post | 56.3 | 54.9 | ||

| Once you fill out and sign an advance directive form you cannot change your mind (false). | pre | 62.1 | 67.7 | .30 |

| post | 79.6 | 78.4 | ||

For acceptability, self-efficacy, and attitudes, we assessed the percentage of participants who agreed with each individual statement. For knowledge we measured the percentage of participants who improved from a pre- to post-form review knowledge assessment.

χ2

For each individual knowledge item, the table lists the percentage of participants who answered the pre- and the post-form review knowledge questions correctly. P-values for the individual knowledge statements reflect the percentage of participants who improved from the pre- to post-form review knowledge assessment.

Footnotes

Previous Presentation: A portion of the study results was presented at the October 6, 2005 International Conference on Communication in Healthcare and the May 5, 2006 American Geriatrics Society.

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Sudore created the redesigned advance directive for use in this study. However, the redesigned advance directive is offered for free on the Institute for Health Care Advancement’s website (iha4health.org), and therefore, Dr. Sudore does not receive any royalties or financial support from this form. Dr. Sudore is funded in part by the Pfizer Foundation through the Clear Health Communication Fellowship. This Foundation has no financial incentives associated with the results of this study, nor does Dr. Sudore. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Copyright Transfer: This manuscript was written in the course of employment by the United States Government and it is not subject to copyright in the United States.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Emanuel LL, Barry MJ, Stoeckle JD, Ettelson LM, Emanuel EJ. Advance directives for medical care--a case for greater use. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(13):889–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103283241305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teno JM, Fisher ES, Hamel MB, Coppola K, Dawson NV. Medical care inconsistent with patients’ treatment goals: association with 1-year Medicare resource use and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):496–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):493–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough. The failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34(2):30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiff R, Rajkumar C, Bulpitt C. Views of elderly people on living wills: interview study. Brit Med J. 2000;320(7250):1640–1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7250.1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker R, Wu AW, Teno JM, et al. Family satisfaction with end-of-life care in seriously ill hospitalized adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S61–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolarik RC, Arnold RM, Fischer GS, Hanusa BH. Advance care planning. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(8):618–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teno JM, Sabatino C, Parisier L, Rouse F, Lynn J. The impact of the Patient Self-Determination Act’s requirement that states describe law concerning patients’ rights. J Law Med Ethics. 1993;21(1):102–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.1993.tb01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanson LC, Rodgman E. The use of living wills at the end of life. A national study. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(9):1018–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ott BB, Hardie TL. Readability of advance directive documents. Image J Nurs Sch. 1997;29(1):53–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1997.tb01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kutner M, Greenbery E, Baer J. A first look at the literacy of America’s adults in the 21st century. National Center for Education Statistics, U.S Department of Education; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Binkley M, Matheson N, Williams T US. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. Adult Literacy: An International Perspective. Washington, D.C.: U.S Department of Education; 1997. http://nces.ed.gov/pubs97/9733.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schillinger D, Bindman A, Wang F, Stewart A, Piette J. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician-patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(3):315–23. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Institute of Medicine. Health literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington DC: National Academic Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudd RE, Comings JP. Learner developed materials: an empowering product. Health Educ Q. 1994;21(3):313–27. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis TC, Bocchini JA, Jr, Fredrickson D, et al. Parent comprehension of polio vaccine information pamphlets. Pediatrics. 1996;97(6 Pt 1):804–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobson TA, Thomas DM, Morton FJ, Offutt G, Shevlin J, Ray S. Use of a low-literacy patient education tool to enhance pneumococcal vaccination rates. A randomized controlled trial. J Amer Med Assoc. 1999;282(7):646–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S, Philipson SJ. Improving the readability and processability of a pediatric informed consent document: effects on parents’ understanding. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(4):347–52. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayes KS. Randomized trial of geragogy-based medication instruction in the emergency department. Nurs Res. 1998;47(4):211–8. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. J Amer Med Assoc. 2002;288(4):475–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Williams BA, Barnes DE, Lindquist K, Schillinger D. Use of a modified informed consent process among vulnerable patients: a descriptive study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):867–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V. End-of-life care in black and white: race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1145–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofmann JC, Wenger NS, Davis RB, et al. Patient preferences for communication with physicians about end-of-life decisions. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preference for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(1):1–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-1-199707010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopp FP. Preferences for surrogate decision makers, informal communication, and advance directives among community-dwelling elders: results from a national study. Gerontologist. 2000;40(4):449–57. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tannenbaum S. The eye chart and Dr. Snellen. J Am Optom Assoc. 1971;42(1):89–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seligman HK, Wang FF, Palacios JL, et al. Physician notification of their diabetes patients’ limited health literacy. A randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1001–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.California Advance Health Care Directive. [Accessed April 10th, 2007]; http://www.caringinfo.org/files/public/California.pdf.

- 29.Institute for Health Care Advancement. [Accessed July 1st, 2007]; www.iha4health.org.

- 30.Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Research Branch report 8-75. Memphis: Naval Air Station; 1975. Derivation of anew readability formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count, and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy enlisted personnel. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLaughlin GH. SMOG grading: a new readability formula. Journal of Reading. 1969;12:639–46. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenfeld KE, Wenger NS, Kagawa-Singer M. End-of-life decision making: a qualitative study of elderly individuals. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(9):620–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.06289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(10):1451–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Douglas R, Brown HN. Patients’ attitudes toward advance directives. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(1):61–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reinders M, Singer PA. Which advance directive do patients prefer? J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9(1):49–51. doi: 10.1007/BF02599143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joos SK, Reuler JB, Powell JL, Hickam DH. Outpatients’ attitudes and understanding regarding living wills. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(5):259–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02600093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sam M, Singer PA. Canadian outpatients and advance directives: poor knowledge and little experience but positive attitudes. Cmaj. 1993;148(9):1497–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silveira MJ, DiPiero A, Gerrity MS, Feudtner C. Patients’ knowledge of options at the end of life: ignorance in the face of death. J Amer Med Assoc. 2000;284(19):2483–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siegert EA, Clipp EC, Mulhausen P, Kochersberger G. Impact of advance directive videotape on patient comprehension and treatment preferences. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5(4):207–12. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.4.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis TC, Fredrickson DD, Arnold C, Murphy PW, Herbst M, Bocchini JA. A polio immunization pamphlet with increased appeal and simplified language does not improve comprehension to an acceptable level. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;33(1):25–37. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flick U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. 2. London, England: Sage Publication, Ltd; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morrison RS, Morrison EW, Glickman DF. Physician reluctance to discuss advance directives. An empiric investigation of potential barriers. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(20):2311–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE., Jr Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102(4):520–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-4-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tulsky JA. Beyond advance directives: importance of communication skills at the end of life. J Amer Med Assoc. 2005;294(3):359–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barry MJ. Health decision aids to facilitate shared decision making in office practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(2):127–35. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]