Abstract

While it is known that matrixmetalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) is present in dentin, its distribution and role in human dentin formation and pathology are not well understood.

OBJECTIVE

To characterize the distribution of MMP-2 in human coronal dentin.

METHODS

Immunohistochemistry was used to investigate the distribution of MMP-2 in coronal dentin. Freshly extracted human premolars and 3rd molars (age range 12–30) were fixed with formaldehyde, demineralized with 10% EDTA (pH=7.4) and embedded in paraffin. Five µm serial sections were made and subjected to immunohistochemical analysis using a specific monoclonal anti-MMP-2 antibody. Immunoreactivity was visualized with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine substrate and observed under light microscopy. ImageJ software was used to calculate the relative amount/distribution of MMP-2.

RESULTS

The analysis revealed immunoreactivity for MMP-2 throughout human coronal dentin. However, intense immunoreactivities were identified in a 90–200 µm zone adjacent to the pre-dentin as well as a 9–10 µm wide zone adjacent to the dentinoenamel junction (DEJ).

CONCLUSION

MMP-2 has a specific distribution in human coronal dentin indicating it’s involvement in extracellular matrix organization in predentin and the establishment of the DEJ.

Keywords: Distribution, Matrix Metalloproteinase-2, Immunohistochemistry, Human Coronal Dentin

INTRODUCTION

Dentin is essentially composed of two phases, mineral and fibrillar collagen/noncollagenous matrix. Early research of dentinogenesis proposed that odontoblasts synthesize a type of collagenase and an inhibitor which bind to the collagen fibrils of the matrix, forming a collagen/collagenase/inhibitor complex.1 The collagenase was then identified in human mineralized dentin matrix, as a~68 kDa protein, functioned at neutral pH and was characterized as a matrix metalloproteinase(MMP).1,2

MMPs 2, 3, 9 & 20 have since been identified in embryonic mouse tooth germ dentin and piglet tooth germ odontoblasts suggesting that these proteases may be involved in dentin matrix formation.3,4 MMP-2 in forming rat incisors may be concentrated in an area adjacent to the dentinoenamel junction (DEJ), in association with odontoblastic processes and odontoblast cell bodies.5 In contrast to MMP-2, a tissue inhibitor of MMPs (TIMP-1) may be in low concentration adjacent to the DEJ and may be increased in concentration in the predentin in forming rat incisors.5 TIMP-1 has been identified in human root dentin and its concentration increases from the external dentin towards the predentin area (towards the pulp).6

MMP-2 (Gelatinase A) in both pro(~72kDa) and active(~68kDa) forms has been identified in human dentin.7,8 Recently MMP-8 (Collagenase-2) and MMP-9 (Gelatinase B) have been suggested to be present in human dentin.8,9 MMP-2 is the predominant MMP in mineralized dentin and may be associated with the collagen matrix but not the hydroxyapatite.7

The evidence in support of the theory that host derived proteinases, in the form of various types of MMPs, are involved in dentin caries pathogenesis is increasing.10,11 MMP-2, an enzyme capable of digesting gelatin/collagen, has been suggested to be involved in dentin caries.7,8 However, due mainly to the variation of origin and preparation of dentin among studies, the distribution, activity and biological function of MMP-2 in this tissue are still not well understood. Despite the significant advancement made with regard to the potential relationship between host-derived MMPs and caries progression, some of the fundamental issues such as the location of MMPs, their association with collagen matrix, mechanisms of MMP activation, etc. still remain unclear.

In this study, as a first step toward understanding the role of MMP-2 in human dentin biology and pathology, we investigated the relative distribution of MMP-2 in human coronal dentin using immunohistochemical (IHC) methodologies. The purpose of this study was to test the null hypothesis that there is no difference in the mean level of maximum MMP-2 immunoreactivity of inner, middle and outer regions of coronal dentin isolated from extracted human premolars and 3rd molars.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research was approved by the UNC Biomedical Institutional Review Board.

Sample preparation

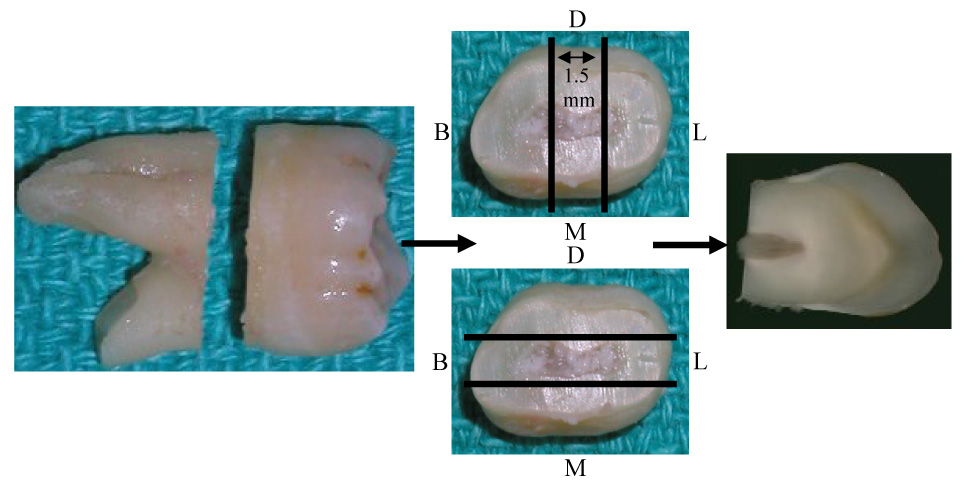

Fifteen non-carious human 3rd molars and premolars with closed apices were placed in 10% formaldehyde immediately after extraction and fixed for 72 hours at 4°C. (Table 1) The teeth were sectioned using a Bueler Isomet (Bueler. Corp., Lake Bluff, IL) diamond impregnated slow speed saw (Isomet) @ 100rpm with ~2° water cooling.(Figure 1) The 1.5 mm mesio-distal (M-D) or bucco-lingual (B-L) sections were demineralized with 10% EDTA for 5 weeks and placed in phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4, (PBS). All demineralized specimens were then parafinized and sectioned.

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis subject demographics (n = 15 teeth)

| Age | Gender | Race | Tooth Type | Eruption Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12–30 years | F(9) | Indian(1) | Premolar(3) | Unerupted(9) |

| M(6) | African American(5) | Max Molar(8) | Erupted(6) | |

| White(9) | Mand Molar(4) | |||

Max = Maxillary, Mand = Mandibular

Figure 1.

Sectioning technique for obtaining a 1.5 mm mesio-distal (M,D) or bucco-lingual (B,L)section of coronal tooth structure. Parallel lines indicate approximate area of section. Arrows indicate flow of sectioning procedures.

A microtome (Leica Jung RN 2045) was used to obtain 5µm sections from each specimen.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Five slides of each subject (10 sections) were deparafinized with xylene, treated with 100% ethanol (EtOH) for 2 minutes, 50%EtOH for 2 minutes and deionized water (dH2O) for 2 minutes.

To better expose the epitopes the sections were then treated with 60 µl of Proteinase K (20 micrograms (µg)/mlPBS)(Proteinase K, recombinant, PCR Grade, Roche Applied Science) for 20 minutes, and then washed with dH2O for 1 minute. The sections were placed in a 0.3%H2O2/EtOH solution for 30 minutes and washed in dH2O.

One section on each slide was then reacted with 30µl of a 100 µg stock solution anti-MMP-2 (α-MMP-2) (Calbiochem:IM33L:Anti-MMP-2 (Ab-3) Mouse mAb (42-5D11), EMD Biosciences, Inc, La Jolla, CA) diluted (1:25) in PBS, blocked with normal horse serum (1:66) for overnight at 4°C in a humidor. As a negative control, some sections were not reacted with the primary antibody but were incubated with PBS with normal horse serum (1:66). After incubation, sections were washed 3 times for 5 minutes each with PBS. A 30 µl volume biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG immunoglobulins (α-mouseIgG)/PBS solution (1:200) blocked with normal horse serum (1:66) was prepared and incubated with the sections for 30 minutes.

After incubation with the biotinylated secondary antibody, the sections were washed with PBS, treated with 30µl of an avidin DH (1:100) and biotinylated horseradish peroxidase H (1:100) complex was placed over the sections and incubated for 30 minutes. The reagents used were part of the Vectastain® ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc. Burlingame, CA).

The sections were then washed with PBS, each section was reacted with 30 µl of a 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution, (DAB Substrate Kit®, Vector Laboratories, Inc. Burlingame, CA) for 12 minutes and the reaction was stopped by immersion in dH2O. Initial IHC studies were counterstained with hematoxylin for 5 seconds before fixation. These sections were then dehydrated via 50% EtOH, 100% EtOH, Xylene washes, 5 minutes each, and then enclosed under a slide cover with DPX and dried.

Specificity of the Antibody

The monoclonal antibody used for these studies was commercially obtained from Calbiochem® (see above). The antibody was generated in mouse against the sequence located in the hinge region of human MMP-2 (amino acids 468-483). The antibody recognizes MMP-2 in both its ~72kDa latent and ~66 kDa active forms. Recombinant human MMP-2 (rhMMP-2)(MMP-2, Active, Human, Recombinant, Calbiochem®, EMD Biosciences, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) generated from Chinese hamster ovary cells (~70.2 kDa proMMP-2 and ~60.9 kDa MMP-2) was used as a positive control.

To establish antibody specificity for MMP-2 as well as MMP-2 gelatinolytic activity, human third molars, obtained from the same subjects whose teeth were used for immunohistochemistry, were obtained immediately after extraction and placed on dry ice until disinfection. The teeth were disinfected in a 1% Thymol solution for 5 days @ 4°C. All specimens were sectioned with the Isomet @ 100rpm with water/ice cooling in the following sequence: 1) The roots were removed and the crowns were divided to expose the pulp chambers 2) Pulp tissue and predentin was removed from each section using a #12 scalpel blade and dental scaling instruments. Enamel was removed with the Isomet slow speed saw.

Coronal dentin from multiple teeth was pulverized for 5 minutes in liquid N2 by a freezer mill (SPEX CertiPrep® 6759 Freezer/Mill, Metuchen, NJ, USA), washed with cold dH2O and lyophilized. The lyophilized samples were then extracted with 0.33 M EDTA/ 2M Guanidine-HCl (pH 7.4) at 4°C. After 48 hours extraction the samples were centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 10 minutes and the pellet was extracted for another 48 hrs. Upon completion of the second extraction the supernatents were combined and dialyzed against cold dH2O and lyophilized.

A 1 or 2 mg of each extract was dissolved in tris-glycine SDS sample buffer for analysis using Western blotting and gelatin zymography.

Quantitative evaluation

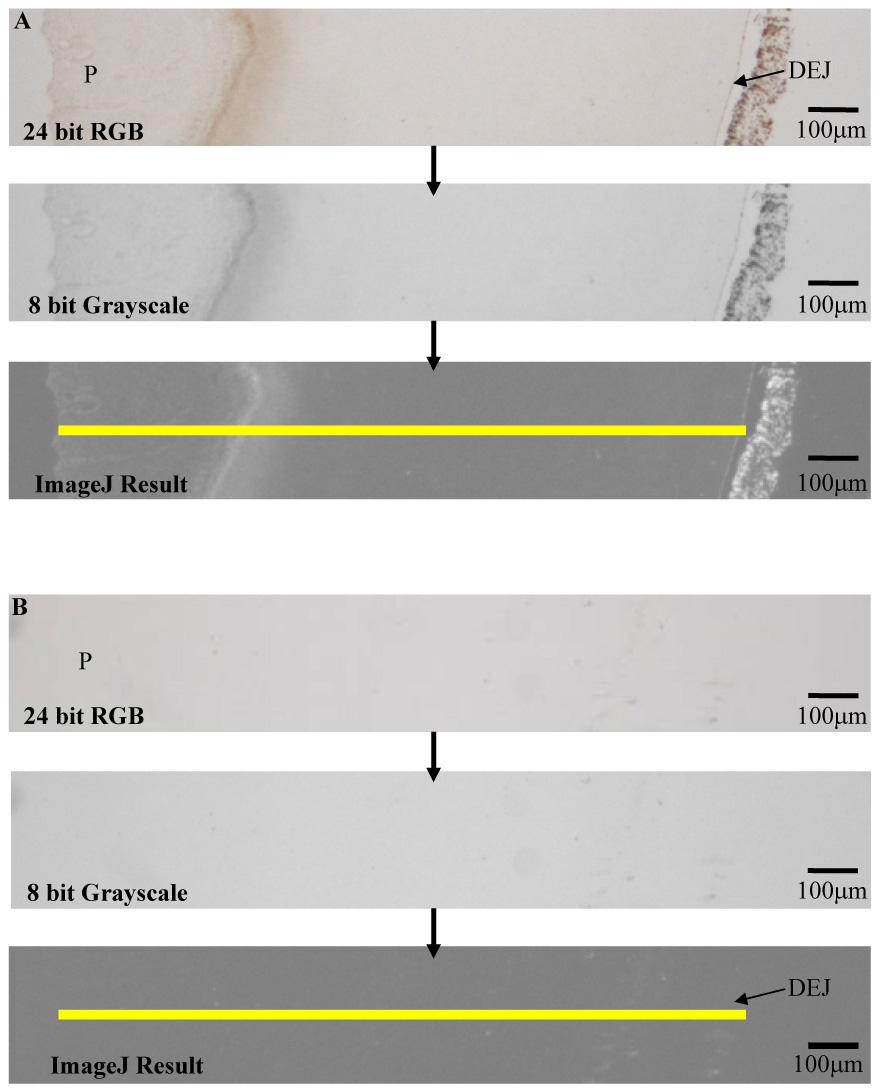

Images of the MMP-2 immunoreacted and control sections were obtained with a Nikon Microphot FXA® microscope coupled with a QImaging® MP-3 digital camera and QCapture® Image Software. Images were processed and analyzed with ImageJ 1.36b software. (Wayne Rashband, National Institutes of Health, USA)

RGB (24 bit) color (Red(8 bit), Green(8 bit), Blue(8 bit)) images were then converted to gray scale (8 bit) images (0–255, where 0 is black, 255 is white, and every point in between is a shade of gray). The gray scale has 256 interger levels of gray. Background gray levels were subtracted in order to correctly measure the gray scale level at each pixel across the image. The formula used to obtain a plot of values in the grayscale range of 0–255 was as follows:

(Image 1 − Image 2)K1 + K2 = Image 2*

Image 1 = image of section with or without α-MMP-2

Image 2 = background (image contributions from the light source, lens and camera)

K1 = 1

K2 = 128

Image 2* = corrected resulting image displayed on the grayscale between 0 and 255.

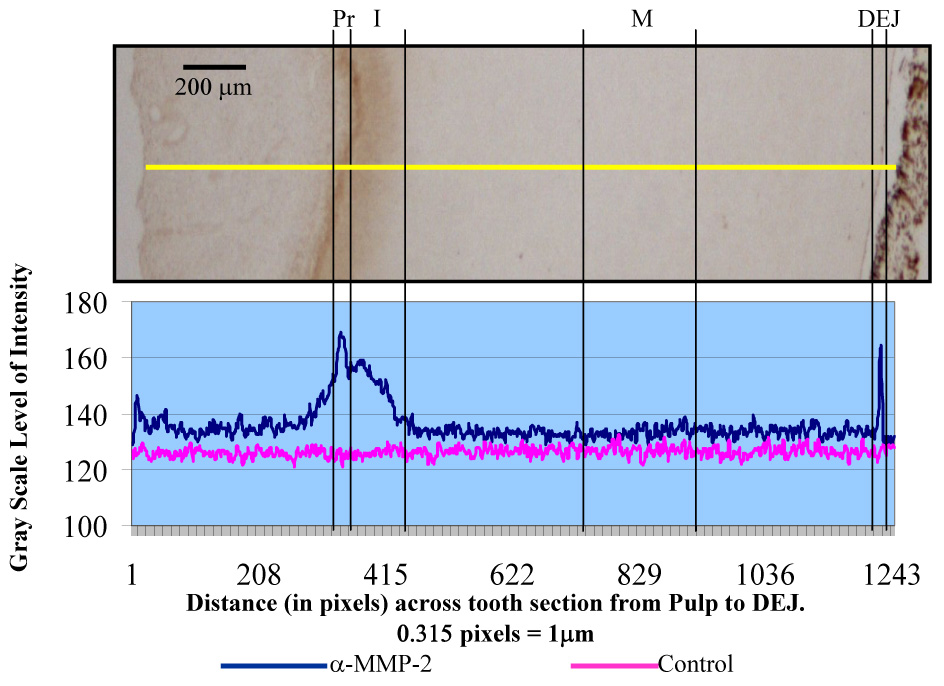

The formula made the assumption that any RGB value above 255 would be displayed as 255 and any RGB below 0 would be displayed as 0. The grayscale level at each pixel along a 1-pixel wide region spanning the pulp, predentin, dentin and DEJ was measured.(Figure 2) These gray scale values were used as a measure of the level of MMP-2 immunoreactivity.

Figure 2.

Example of RGB to grayscale image processing. The yellow line represents a one pixel wide region from pulp (P) to beyond the dentinoenamel junction (DEJ). The grayscale level at every pixel along this line was measured to develop an analysis plot of MMP-2 immunoreactivity. Sections were probed with α-MMP-2 (A) or Control (B) No counterstain was used.

Statistics

The statistical method used to analyze grayscale values from the inner (I), middle (M) and outer (O) dentin regions was a repeated measures one-way analysis of variance. This method assumed independence of observations at the 3 locations in dentin and used an aggregate grayscale value from 10 sections of each tooth (5 probed with α-MMP-2, 5 control). The working correlation between regions of dentin was assumed to be minimal (0.1). Pilot studies of 3 teeth indicated that a sample size of 15 teeth would have a 90% power at the level of statistical significance of 0.05 to detect an effect size of 0.2963.

RESULTS

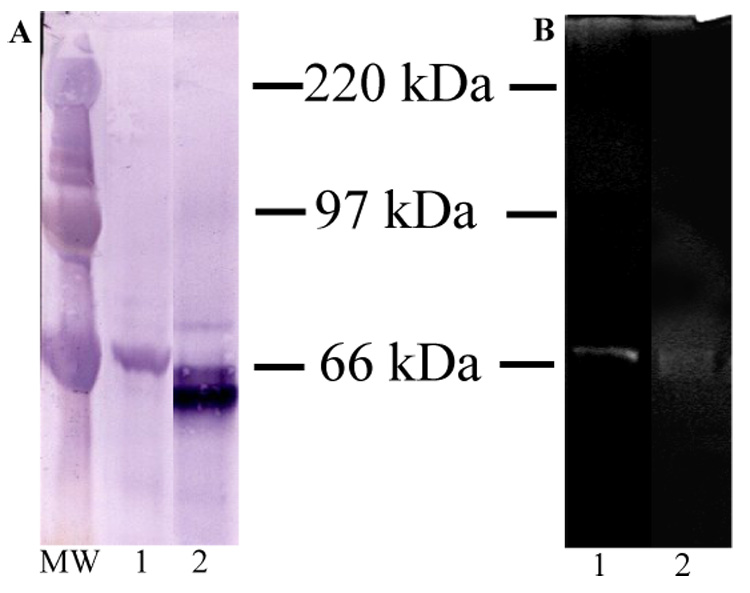

Antibody Specificity and MMP-2 Activity

The presence of MMP-2 in human coronal dentin and antibody specificity for MMP-2 were verified by Western blotting and gelatin zymography.(Figure 3 A and B) Western blot analysis of the human coronal dentin extract with α-MMP-2 revealed immunoreactivity at approximately ~72 and ~68 kDa (proform and active form respectively). Gelatin zymography revealed gelatinolytic activity at ~68 kDa in the extract of human coronal dentin. Western blot analysis of the positive control rhMMP-2 with α-MMP-2 revealed the proform (~70 kDa) and active form (~61 KDa). (Figure 3 A) The positive control rhMMP-2 also revealed gelatinolytic activity at a slightly lower molecular weight. The slight difference in molecular weight between the dentin MMP-2 and rhMMP-2 is likely due to the difference in post translational modifications inherent to recombinant systems. (Figure 3 B)

Figure 3.

A) Western blot analysis with α-MMP-2, Lane 1 = 80 µg Guanidine HCl/EDTA extract of human coronal dentin, Lane 2 = 0.1µg rhMMP-2 positive control. B) Gelatin Zymogram, Lane 1 = 160 µg Guanidine HCl/EDTA extract of human coronal dentin, Lane 2 = 0.5ng rhMMP-2 positive control. MW = molecular weight standards.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

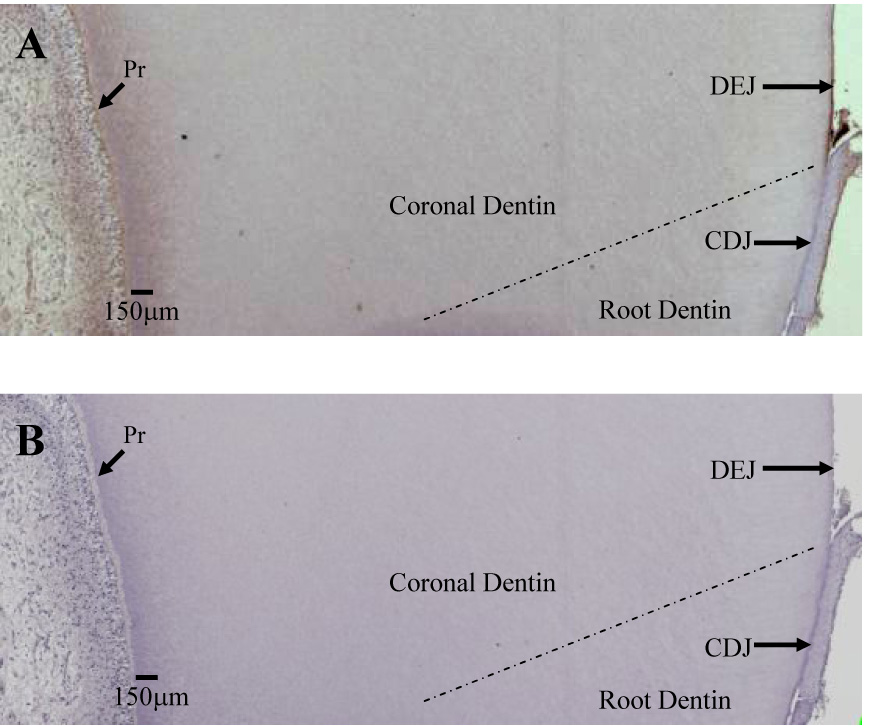

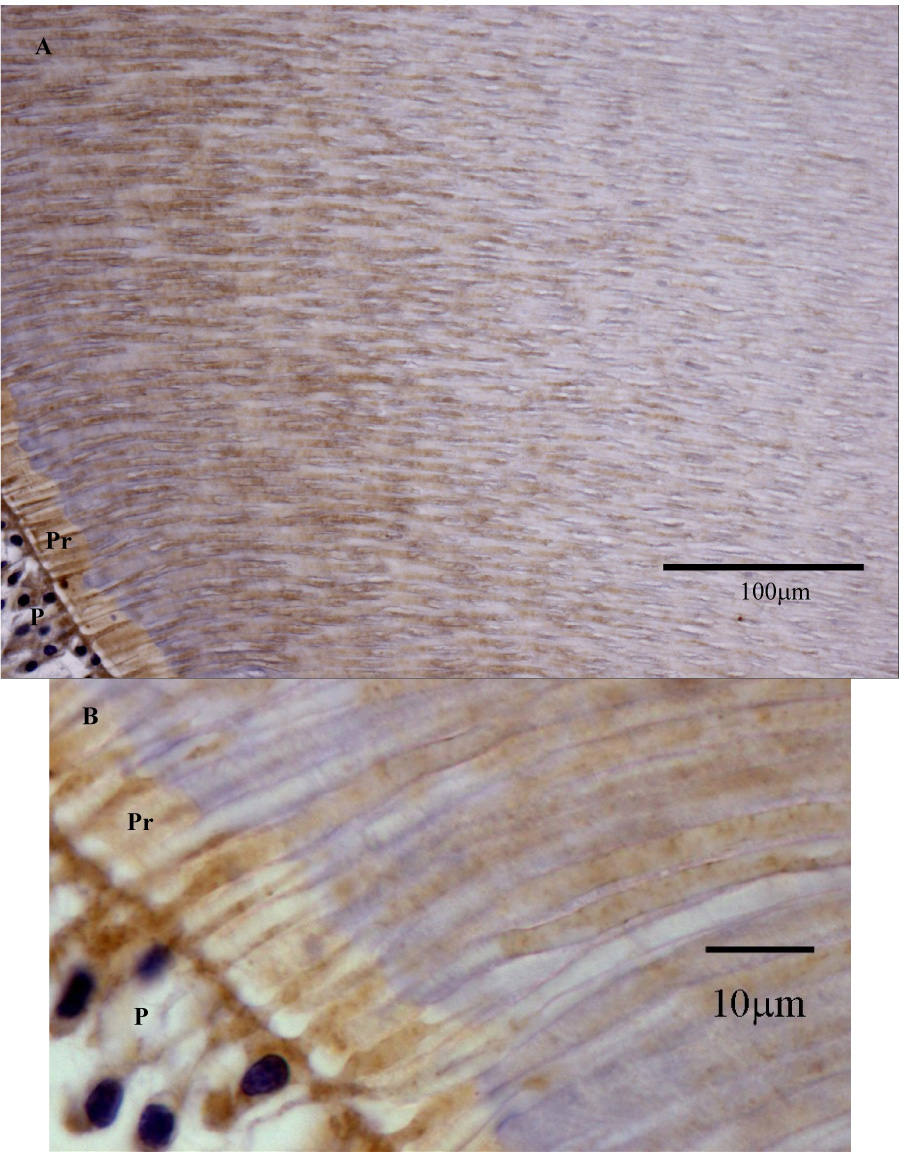

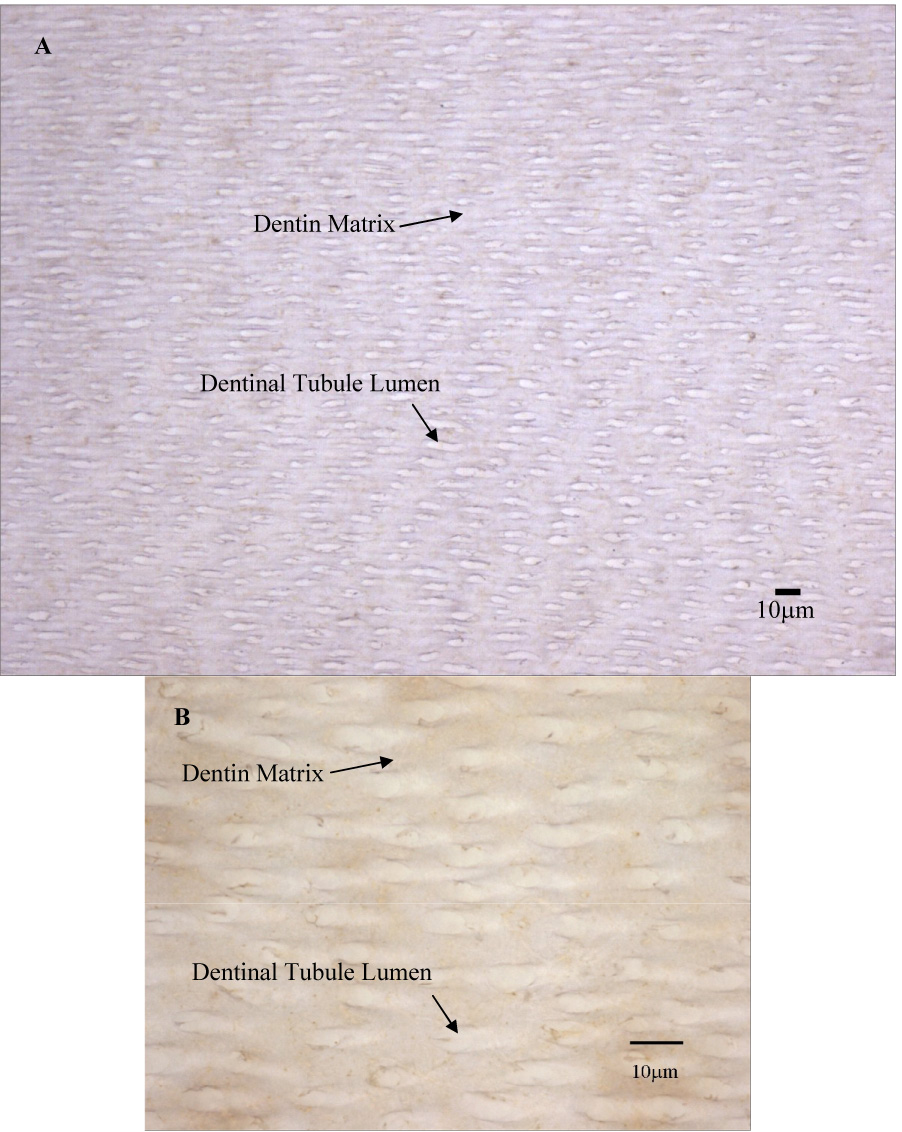

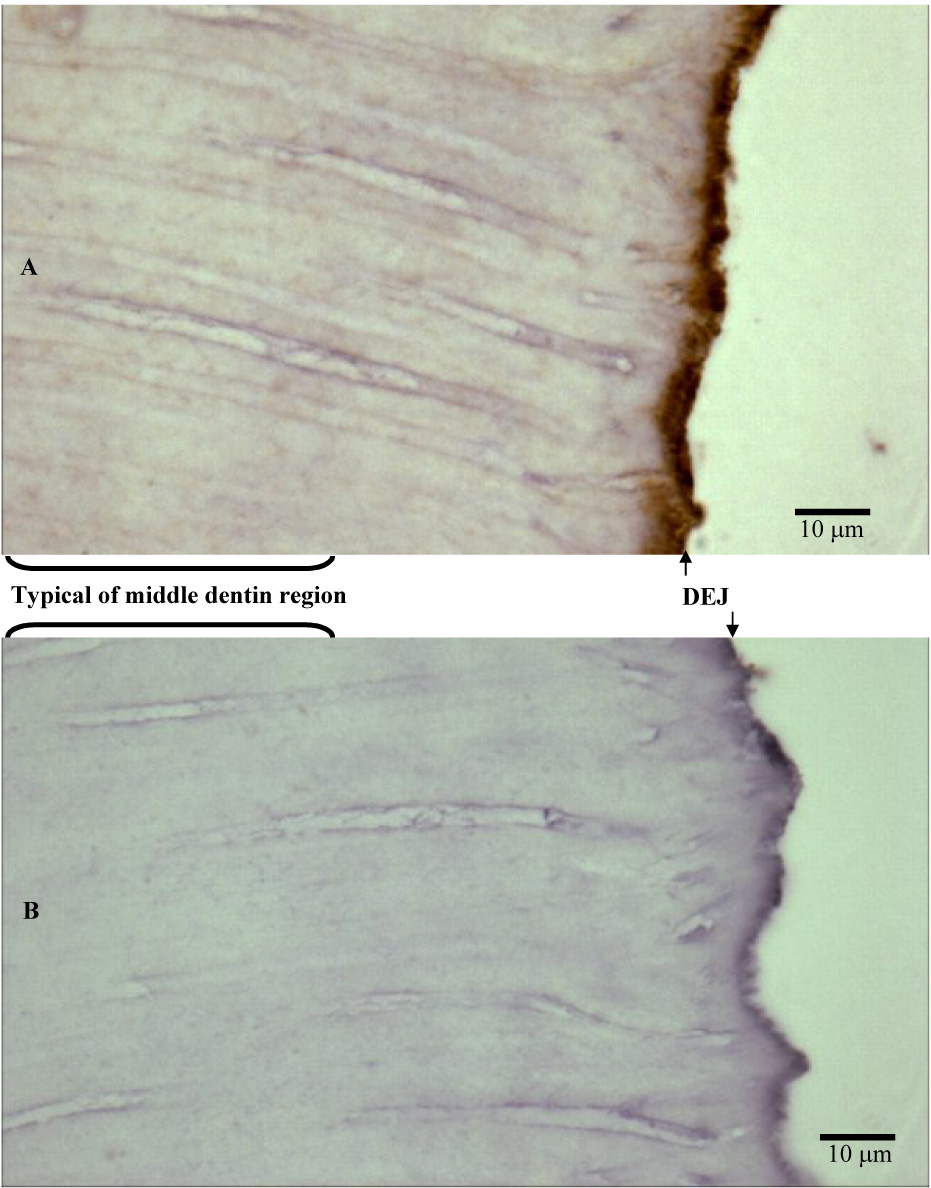

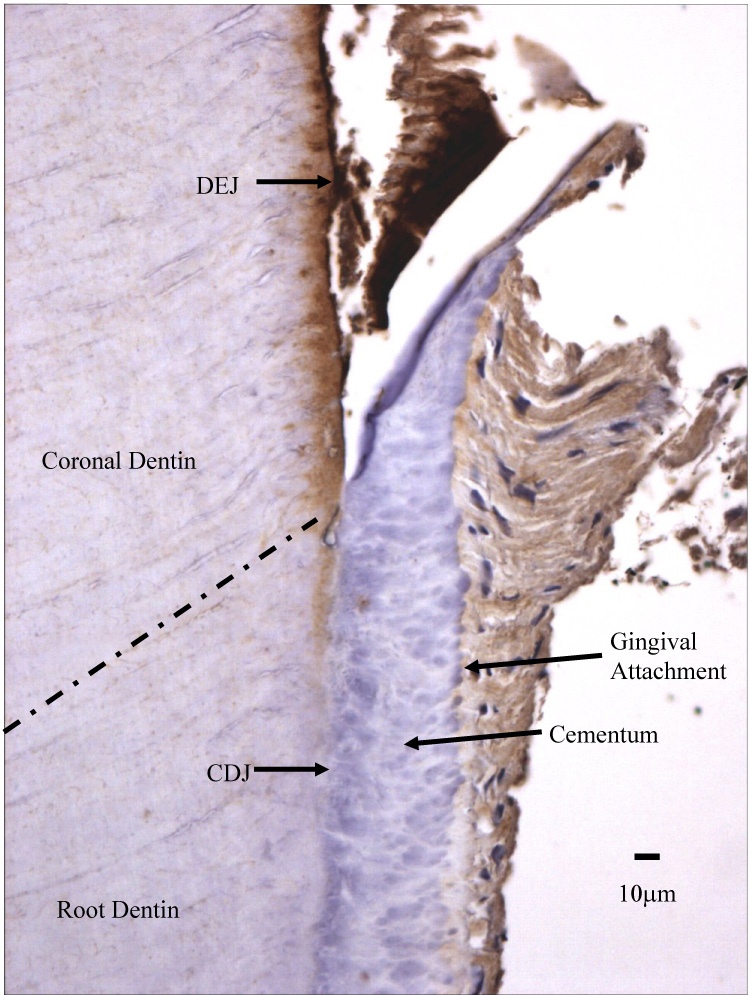

MMP-2 immunoreactivity was readily identified in the pulp, predentin and dentin.(Figure 4) In the pulp MMP-2 was associated with the odontoblasts and the extracellular matrix. MMP-2 in association with the odontoblastic processes was clearly seen in the predentin (10–20 µm in width) as well as in association with the newly formed, non-mineralized predentin matrix.(Figure 5) Immunoreactive areas in the mineralized dentin included the odontoblastic processes in the dentinal tubules as well as intertubular dentin. Greater immunoreactivity was identified in the 100–200µm zone immediately adjacent to the predentin, as compared with middle dentin, and was associated with the odontoblastic processes.(Figure 5) Immunoreactivity in middle dentin was associated with the dentin matrix but not the dentinal tubule lumens. (Figure 6) A 9–10µm zone immediately adjacent to the DEJ demonstrated greater immunoreactivity than middle or inner dentin and was associated with the dentin matrix.(Figure 7) Such intense immunoreactivity for MMP-2 was not identified with dentin immediately adjacent to the cementodentin junction (CDJ).(Figure 8) Analyses of 15 teeth revealed a range of levels of staining, but the immunostaining pattern was consistent among all the samples examined.(Table 2)

Figure 4.

Section of demineralized dentin probed with α-MMP-2 (A) demonstrating areas of greater immunoreactivity adjacent to the predentin (Pr) and dentinoenamel junction (DEJ) and minimal immunoreactivity at the cementodentin junction (CDJ). MMP-2 is visualized as a brown stain. B is negative control.

Figure 5.

A: Section of human coronal tooth structure demonstrating transition of intense MMP-2 immunoreactivity in inner dentin to area of less MMP-2 immunoreactivity. MMP-2 associated with the odontoblastic processes appears to be the primary cause of intense MMP-2 immunoreactivity in inner dentin. B: Higher magnification of MMP-2 immunoreactivity in the area of the pre-dentin. P = Pulp. Pr = Predentin. Counterstain is hematoxylin.

Figure 6.

A: Area typical of MMP-2 immunoreactivity in middle dentin. MMP-2 is localized primarily with the dentin matrix and not the tubule lumens. B: Higher Magnification of MMP-2 immunoreactivity in middle dentin. Counterstain is hematoxylin.

Figure 7.

Sections of human coronal tooth structure including a represenstive area typical of middle dentin and the DEJ region, probed with α-MMP-2 (A) and negative control (B). Intense MMP-2 immunoreactivity adjacent to the DEJ appears to be associated with the dentin matrix. Counterstain is hematoxylin.

Figure 8.

Section of dentin probed with α-MMP-2 demonstrating areas of greater immunoreactivity adjacent dentinoenamel junction (DEJ) and the disappearance of intense immunoreactivity at the cementodentin junction (CDJ). MMP-2 is visualized as a brown stain.

Table 2.

The difference between mean maximum grayscale values of sections probed with α-MMP-2 and control sections in inner, middle and outer regions of human coronal dentin.

| Tooth ID N = 15 | Inner Dentin (SD) N = 5 measures/tooth | Middle Dentin (SD) N = 5 measures/tooth | Outer Dentin (SD) N = 5 measures/tooth |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 53.1 (30.2) | 34.3 (19.6) | 59.8 (31.7) |

| 27 | 34.2 (5.7) | 7.9 (5.5) | 22.1 (6.7) |

| 31 | 37.9 (10.2) | 8.6 (1.3) | 48.8 (10.9) |

| 38 | 9.5 (3.1) | 2.8 (0.9) | 23.3 (4.0) |

| 39 | 13.8 (5.5) | 5.9 (2.8) | 17.2 (4.0) |

| 42 | 11.5 (1.7) | 4.9 (2.6) | 55.1 (23) |

| 46 | 4.8 (2.5) | 1.8 (1.3) | 15.5 (9.4) |

| 49 | 17.4 (4.6) | 6.4 (6.4) | 32.1 (7.2) |

| 57 | 17.2 (4.2) | 9.9 (4.7) | 19.5 (9.4) |

| 60 | 57.2 (7.1) | 37.9 (7.4) | 60.3 (6.6) |

| 64 | 35.8 (3.4) | 29.0 (2.4) | 54.3 (6.9) |

| 69 | 31.3 (6.6) | 14.1 (3.3) | 50.4 (18.8) |

| 77 | 31.4 (18.3) | 12.1 (11.3) | 45 (17.8) |

| 80 | 44.7 (11.0) | 7.0 (1.9) | 46.3 (14.6) |

| 81 | 35.7 (13.5) | 7.2 (1.9) | 51.6 (13.6) |

| Least Squares Means | 29.0 | 12.7 | 40.1 |

The levels of MMP-2 immunoreactivity (measured as levels of gray scale intensity) were utilized to develop an analysis plot for each tooth section.(Figure 9) Analysis of variance showed the mean maximum level of MMP-2 immunoreactivity of inner, middle and outer regions of dentin were significantly different (p<0.001). Rejection of the null hypothesis, that there was no difference in the mean maximum levels of MMP-2 immunoreactivity among the three regions, was indicated. Pairwise contrasts indicated that all three possible section pairs of MMP-2 immunoreactivity were significantly different in maximum mean grayscale values: outer vs inner, mean difference = 11.1 ; p=0.0011; inner vs middle, mean difference = 16.3, p <0.0001; outer vs middle, mean difference =27.4, p<0.0001.

Figure 9.

Analysis plot of MMP-2 immunoreactivity, measured on a grayscale (0–255), of the predentin (Pr), inner (I), middle (M),and dentinoenamel junction (DEJ) regions of coronal tooth structure. An image of coronal dentin section probed with α-MMP-2 is included for reference. The yellow line indicates region of analysis.

Comparison of the level of immunoreactivity with subject age, subject race, subject gender, tooth section orientation, tooth origin (maxilla or mandible), and tooth eruption status, revealed no detectable correlation. (data not shown)

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study are consistent with other studies reporting that MMP-2 is present in dentin.2,3,5,7,8,11,12 IHC indicates that MMP-2 is concentrated in the predentin and the inner dentin area adjacent to the predentin, which is consistent with the hypothesis that MMP-2 is actively involved in the organization of pre-mineralized matrix formation as well as its subsequent mineralization.3,5,13 The increased level of inner dentin MMP-2 immunoreactivity observed by light microscopy is primarily due to the presence of MMP-2 in association with the odontoblastic processes. As a result, ongoing odontoblastic MMP-2 expression could result in MMP-2 diffusion and sequestration thoughout the dentinal tubule network of the intact tooth.7 The level of immunoreactivity of MMP-2 in the middle dentin region, based on IHC, is significantly lower than the inner dentin (adjacent to the predentin) but is consistently present. Thus, demineralized dentin matrix may represent a source of MMP-2.7,8,12 Concentration at the DEJ suggests that MMP-2 may be involved in establishment of the DEJ and initiation of dentin formation as other studies have suggested.3,5,13 As dental caries progresses through the enamel and into dentin there is an initial spread at the DEJ. The high concentration of MMP-2 at the DEJ could be in part responsible for this clinical phenomenon.5

The notable lack of intense MMP-2 immunoreactivity in cementum and at the cementodentin junction, to the best of our knowledge, has not been reported. Both dentin and cementum contain fibrillar collagen, a primary substrate of MMP-2, as well as noncollagenous proteins. Studies in the rat reveal that there are subtle compositional and organizational differences of matrix proteins in these two anatomically and functionally different regions.14 The difference in MMP-2 immunoreactivity distribution may also reflect such compositional variation. Further research identifying the relative distribution of non-collagenous proteins in human coronal and radicular mantle dentin is warranted.

The IHC detection of MMP-2 does not mean it is active. Some studies indicate that the ability to detect activity of MMP-2 extracted from the dentin matrix of human teeth decreases with time, however, it is unclear whether the intact MMP-2 was missing (subject to autolysis over time) or present but inactive.7 The inclusion criteria of this study were designed so as to not be negatively impacted by the potential reduction in MMP-2 associated with the demineralized matrix. Within the limits of this study, there was no correlation between the level of IHC immunoreactivity and the age of the subjects (age range 12–30 years). Furthermore, subject race, subject gender, tooth section orientation, tooth origin (maxilla or mandible), and tooth eruption status did not correlate with the level of IHC immunoreactivity. Variation in staining of sections from individual teeth and the resulting large standard deviations from the mean (Table 2) may represent the technique sensitivity of the specimen preparation process, or possibly different levels of MMP-2 expression from subject to subject. Previously reported reduction in the presence of MMP-2 in older subjects7 may actually be secondary to sample size and the pooling of teeth from individuals with very low levels of MMP-2. This notion is consistent with recent studies that identify the potential for a range of MMP-2 expression levels resulting from individual MMP-2 gene polymorphisms.17,18 The pooling of teeth from multiple subjects may mask this variation in the population. Variation in MMP-2 levels among subjects also suggests a potential relationship between the level of MMP-2 present in dentin and individual dental caries susceptibility. Further research is indicated to help clarify these issues.

CONCLUSIONS

MMP-2 is present throughout human coronal dentin with concentrated areas adjacent to the predentin and DEJ. Apparent concentration adjacent to the predentin is due to MMP-2 in association with odontoblastic processes in addition to the collagen matrix. Concentration of MMP-2 at the DEJ is associated with the dentin matrix. Future studies are warranted to identify if MMP-2 isolated from human dentin is able to digest collagen isolated from the same dentin and what mechanisms are required for its activation. Also, additional studies must evaluate the potential relationship between dentin MMP-2 concentration and caries rates.

Acknowledgements

This investigation was supported by NIH grants DE10489, DE015876 and the UNC School of Dentistry. This manuscript represents part of Dr. Boushell’s thesis, which was submitted to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science in Dentistry degree at the UNC School of Dentistry. Portions of this manuscript were presented in abstract form at the 85th General Session & Exhibition of the IADR in New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, and published in the Abstracts, Journal of Dental Research, Vol. 86, Special Issue A. We greatly appreciate the assistance of Dr. Ceib Phillips and Ms. Se Hee Kim in the statistical analysis of this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dayan D, Binderman I, Mechanic GL. A Preliminary Study of Activation of Collagenase in Carious Human Dentin Matrix. Archives of Oral Biol. 1983;28(2):185–187. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(83)90126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dumas J, Hurion N, Weill R, Keil B. Collagenase in mineralized tissues of human teeth. Fed of Eur Biochem Societies. 1985;187(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)81212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fanchon S, Bourd K, Septier D, et al. Involvement of matrix metalloproteinases in the onset of dentin mineralization. Eur J Oral Sci. 2004;112:171–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2004.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukae M, Tanabe T, Uchida T, Lee SK, Ryu OH, Murakami C, Wakida K, Simmer JP, Yamada Y, Bartlett JD. Enamelysin (Matrix Metalloproteinase-20): Localization in the Developing Tooth and Effects of pH and Calcium on Amelogenin Hydrolysis. J Dent Res. 1998;77(8):1580–1588. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770080501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg M, Septier D, Bourd K, Hall R, George A, Goldberg H, Menashi S. Immunohistochemical Localization of MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2 in the Forming Rat Incisor. Connective Tissue Research. 2003;44:143–153. doi: 10.1080/03008200390223927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishiguro K, Yamashita K, Nakagaki K, Iwata K, Hayakawa T. Identification of Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) in Human Teeth and Its Distribution in Cementum and Dentine. Archs Oral Biol. 1994;39(4):345–349. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(94)90126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin-De Las Heras S, Valenzuela A, Overall CM. The matrix metalloproteinase gelatinase A in human dentine. Archs Oral Biol. 2000;45:757–765. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(00)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzoni A, Mannello F, Tay FR, Tonti GAM, Papa S, Pashley DH, Breschi L. Zymographic Analysis and Characterization of MMP-2 and -9 Forms in Human Sound Dentin. J Dent Res. 2007;86(5):436–440. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sulkala M, Tervahartiala T, Sorsa T, Larmas M, Salo T, Tjäderhane Matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8) is the major collagenase in human dentin. Arch Oral Biology. 2007;52:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dung SZ, Gregory RL, Li Y, Stookey GK. Effect of Lactic Acid and Proteolytic Enzymes on the Release of Organic Matrix Components from Human Root Dentin. Caries Res. 1995;29:483–489. doi: 10.1159/000262119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tjäderhane L, Larjava H, Sorsa T, Uitto VJ, Larmas M, Salo T. The Activation and Function of Host Matrix Metalloproteinases in Dentin Matrix Breakdown in Caries Lesions. J Dent Res. 1998;77(8):1622–1629. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770081001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Strijp AJP, Jansen DC, DeGroot J, ten Cate JM, Everts V. Host Derived Proteinases and Degradation of Dentin Collagen in situ. Caries Research. 2003;37:58–65. doi: 10.1159/000068223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satoyoshi M, Kawata A, Koizumui T, Inoue K, Itohara S, Teranaka T, Mikuni-Takagaki Y. Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 in Dentin Matrix Mineralization. J of Endodontics. 2001;27(7):462–466. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200107000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKee MD, Zalzal S, Nanci A. Extracellular Matrix in Tooth Cementum and Mantle Dentin: Localization of Osteopontin and Other Noncollagenous Proteins, Plasma Proteins, and Glycoconjugates by Electron Microscopy. The Anatomical Record. 1996;245:293–312. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199606)245:2<293::AID-AR13>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaussain-Miller C, Fioretti F, Goldberg M, Menashi S. The Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) in Human Caries. J Dent Res. 2006;85(1):22–32. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fedarko NS, Jain A, Karadag A, Fisher LW. Three small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLINGs) bind and activate specific Matrix metalloproteinases. The FASEB Journal. 2004;18:734–736. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0966fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price SJ, Greaves DR, Watkins H. Identification of novel, functional genetic variants in the human matrixmetalloproteinase-2 gene: role of Sp1 in allele-specific transcriptional regulation. Journal of Bilogical Chemistry. 2001;276:7549–7558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010242200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen D, Wang Q, Ma Z-W, Chen F-M, Chen Y, Xie G-Y, Wang Q-T, Wu Z-F. MMP-2, MMP-9 and TIMP-2 gene polymorphisms in Chinese patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:384–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]