Abstract

The cultural backgrounds and experiences of Mexican-origin mothers and fathers (including their Anglo and Mexican cultural orientations and their familism values) and their socioeconomic background (parental education, family income, neighborhood poverty rate) are linked to the nature of their involvement in adolescent peer relationships.

Direct involvement of parents in their sons’ and daughters’ peer relationships is a distinct dimension of the parent-child relationship (Parke and others, 2003) that has been associated with the qualities of children’s and adolescents’ peer relationships and with their social competence and psychosocial functioning (Mounts, 2004; Updegraff, McHale, Crouter, and Kupanoff, 2001). Parents may be involved in adolescents’ peer relationships in numerous ways: providing support and advice regarding interactions with friends and peers, discouraging involvement with problematic peers, monitoring and supervising daily activities and experiences with peers, or spending time in the company of adolescents and their peers.

Although most studies have focused on European American families, two cross-cultural investigations (Hart and others, 1998; Mounts, 2004) and the work in this volume use ethnic comparative designs to highlight the nature and importance of the parental role in other cultures and in ethnic minority families in the United States. These ethnic-comparative designs offer important insights about similarities and differences across racial, ethnic, and cultural groups in the connections between parents’ involvement in youth peer relationships and the quality, social competence, and psychosocial functioning of youth friendship. In this chapter, we extend the study of culture in parents’ involvement in adolescent peer relationships by using an ethnic-homogeneous design, focusing only on the experiences of Mexican-origin families, to explore how cultural and ecological experiences are linked to within-group variations in parental roles in adolescent peer relationships.

The Cultural Ecology of Mexican-Origin Families’ Daily Lives

In describing the lives of Latino families, Szapocznik and Kurtines (1993) draw attention to the multicultural settings in which individuals’ and families’ lives are embedded and underscore the significance of the “culturally pluralistic milieu” (pp. 401–402) that is an everyday reality for ethnic minority parents and youth. They may spend time in settings with primarily Mexican-origin individuals as well as in contexts that are ethnically heterogeneous or predominantly Anglo. Families may reside in neighborhoods that are primarily Latino or in areas that are ethnically diverse. Similarly, families may be involved in community or religious activities that vary in their representation of Mexican and Anglo culture.

Recent conceptualizations of the cultural adaptation process reflect the complexities of negotiating involvement in both ethnic and mainstream culture. Specifically, scholars have proposed that individual cultural orientation develops through two independent and concurrent processes: acculturation, or the process of adopting values and beliefs and being involved in the mainstream culture; and enculturation, or involvement in and acceptance of beliefs, values, and practices related to the ethnic culture (Berry, 2003; Knight and others, 1993). Theorists also draw attention to the multifaceted nature of the cultural adaptation process, noting that cultural orientations involve knowledge, attitudes, values, behaviors, and self-concepts related to each culture.

Viewing cultural adaptation as a bidimensional and multifaceted process highlights the possibility of important within-group variations. In the present study, we adopted a person-oriented approach (Magnusson, 1998) to determine whether subgroups of families could be identified who varied in their orientation toward Anglo and Mexican culture (as well as their socioeconomic background, an issue to which we return later). We then examined how these groups differed in their cultural backgrounds and experiences and Mexican cultural values. By moving beyond “proxy” measures (such as nativity or generation status), attending to specific elements of cultures (for example, familism values), and considering indicators of both acculturation and enculturation (Gonzales and others, 2002), we established our goal of describing potentially different cultural ecologies that emerge within a group of Mexican-origin families.

The Intersection of Culture and Social Class

Ecological and sociocultural perspectives (García Coll and others, 1996; McAdoo, 1993) direct attention to the cultural and ecological conditions that underlie family relationship processes and youth development. Defining the broader context of families’ lives are both their cultural backgrounds and experiences and their social class positions, including educational and economic resources and the characteristics of their immediate contexts (for example, neighborhood poverty). Research on ethnic minority families has been limited to a focus on families facing difficult economic circumstances (among them poverty, unemployment, and economic stress) and has failed to consider the intersection of social class and ethnic group membership (McLoyd, 1998; Roosa, Morgan-Lopez, Cree, and Specter, 2002).

Our goal is to describe the combination of cultural and social ecological factors that characterize subgroups of Mexican-origin families rather than to identify (and separate) the distinct influences of social class and ethnicity on parental roles in adolescent peer relationships. These conditions are intricately linked in everyday family life and in research design and measurement. Separating their influences can obscure the ecological realities of everyday lives and compromise efforts to build a foundation of knowledge about ethnic minority families (Roosa, Morgan-Lopez, Cree, and Specter, 2002). A person-oriented approach enables us to describe types of families on the basis of patterns across a group of variables rather than considering how each individual aspect of the family ecology (income, parent education, Mexican cultural orientation, and so on) relates to parenting processes. Such an approach offers a holistic picture of different family contexts and the parenting strategies adopted within each context.

The Cultural and Social Ecology of Parental Roles in Adolescent Peer Relationships

We know little about characteristics of the broader context that may shape Mexican-origin parents’ roles in adolescent peer experiences. Shared experiences, values, and living conditions that result from membership in a particular cultural group or from family socioeconomic status are linked to parenting styles, values, and practices (Hoff, Laursen, and Tardif, 2002; Kohn, 1977; Roosa and others, 2005). We expected that a family’s cultural orientation and values as well as its socioeconomic resources would set the stage for a role in adolescent peer relationships.

A key cultural value that has been described in Mexican American families and captured in the construct of familism is emphasis on family support and loyalty and on interdependence among family members (Cauce and Domenech-Rodríguez, 2002). Anecdotal writings on the importance of family support for Mexican Americans have been substantiated by empirical work (Sabogal, 1987). Sabogal (1987) found that Latino adults, including those of Mexican origin, endorsed higher values of family support, obligation to family members, and using family members as referents than did individuals of European American descent. Within-group analyses of Latinos who differed in generation status revealed that values regarding family support did not differ across generations, but values regarding family obligations and use of family as referent were stronger for foreign-born Latino adults than U.S.-born. Respect for parents and authority figures, also referred to as respeto, is another value that has been emphasized in Mexican culture (Marín and Marín, 1991), although it has received little empirical attention. We anticipated that families with strong ties to Mexican culture and limited economic resources may be more likely to adopt strong values regarding familism and respect and discourage or deemphasize adolescents’ peer relationships (for example, providing less support and placing more restrictions on peer relationships).

Socioeconomic status has been conceptualized and measured in a variety of ways, with the three most common indicators being education, income, and occupational status (Duncan and Magnuson, 2003; Hoff, Laursen, and Tardif, 2002). Numerous explanatory processes underlie associations between socioeconomic status and parenting. Hoff and coauthors (2002) proposed that socioeconomic status is influential in the physical and social settings children experience (for example, the type of neighborhood they live in and school they attend), parenting values and customs (values for conformity versus independence), and the characteristics of parents (intellectual abilities, mental health). Differences in parents’ values by social class have been highlighted across several studies, with a pattern suggesting that lower-SES parents place greater emphasis on obedience and conformity whereas higher-SES parents emphasize independence and autonomy (Hoff, Laursen, and Tardif, 2002). Similarly, research on SES and parenting styles suggests that authoritative parenting styles (warmth and moderate control) are more common in families with a higher education level whereas authoritarian styles (high level of control) are more common in families with fewer educational resources (Dornbusch and others, 1987). Directly related to this study is evidence that high-SES parents are more likely to encourage youth to participate in activities outside the home than are low-SES parents (O’Donnell and Stueve, 1983). Kohn (1977) proposed that these differences in parenting may be attributed in part to the occupational experiences and conditions of working versus middle-class parents. We anticipated that when the family ecology was defined by socioeconomic resources and strong ties to Anglo culture, parents would assume roles that foster young people’s peer relationships.

Juntos (“Together”): Families Raising Successful Teens Project

This project was designed to examine gender, culture, and family socialization processes in two-parent Mexican-origin families raising teenagers (McHale and others, 2005; Updegraff and others, 2005). The 246 participating families were recruited through schools in and around a southwestern metropolitan area. All mothers were Mexican or Mexican American (a criterion for participation), and 93 percent of fathers were also of Mexican origin. To be eligible, four family members had to be living in the home and agree to participate: (1) a seventh grader (the target adolescent), (2) an older sibling, (3) the biological mother, and (4) a biological or long-term adoptive father (a minimum of ten years). Data were gathered on parents’ roles in seventh graders’ peer relationships.

Participants

To recruit families, letters and brochures describing the study in English and Spanish were sent to families, and follow-up telephone calls were made by bilingual staff to determine eligibility and interest in participation. Family names were obtained from junior high schools in five school districts and from five parochial schools (see Updegraff and others, 2005, for more details).

Families represented a range of education and income levels. The percentage of families in the sample who met federal poverty guidelines (18.3 percent) matched the figure for two-parent Mexican American families in the county from which the sample was drawn (18.6 percent). Annual median family income was $40,000. Parents had completed an average of ten years of education. Most parents were born outside the United States (71 percent of mothers and 69 percent of fathers); this subset of parents had lived in the United States an average of 12.4 (SD = 8.9) and 15.2 (SD = 8.9) years for mothers and fathers, respectively. About-two thirds of the interviews with parents were conducted in Spanish. The sample included 125 girls and 121 boys, who averaged 12.8 (SD = .58) years of age. Most of the young people were born in the United States (62 percent) and were interviewed in English (83 percent).

Measures

All measures were foreward- and back-translated into Spanish (to check consistency with the Mexican dialect used locally) by two separate individuals. All final translations were reviewed by a third native Mexican American translator, and discrepancies were resolved.

Background Information

Parents reported their education in years, annual income, country of birth, language preference, and family size.

Neighborhood Characteristics

We used geographic information systems (GIS) to link families’ addresses to census data defining neighborhoods by police grids (half-mile by half-mile areas that coincided with census block groups in almost all cases). For each family, we calculated the percentage of families living in poverty in the neighborhood and the percentage of adults (over twenty-five years of age) without a high school diploma. Parents also rated the degree to which they believed their neighborhood was safe (Roosa and others, 2005), with higher scores on this nine-item scale indicating greater perception of safety (alphas were > .84 for both parents).

Cultural Orientations and Values

To measure parents’ cultural orientation, mothers and fathers completed the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans II (ARSMA II; Cuéllar, Arnold, and Maldonado, 1995). The ARSMA II includes two subscales, one focused on Mexican orientation (seventeen items) and the other on Anglo orientation (13 items). Alphas ranged from .74 to .86.

Parents’ Mexican cultural values were measured with four subscales of the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (Knight and others, 2007): family support and closeness, family obligations, family as referent, and respect. Higher scores indicate stronger levels of the scale characteristic. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .61 to .69.

Parents’ Roles in Adolescents’ Peer Relationships

Parental reports of supporting and restricting peer relationships were adapted from Updegraff, McHale, Crouter, and Kupanoff (2001) and Mounts (2000), with additional items included that were based on qualitative work with Mexican American families. The support subscale included eight items that represented parents’ interest in and support for adolescents’ peer relationships. The restricting subscale included four items that tapped parents’ efforts to minimize involvement with peers. Items were averaged to form the two subscale scores for mothers and fathers, with higher scores indicating greater support and restrictions. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .69 to .78.

Parents’ Knowledge

Parents’ knowledge about adolescent peer-oriented activities was indexed by a three-item subscale from the measure of parental knowledge about their adolescents’ everyday whereabouts, companions, and activities (Crouter, Helms-Erikson, Updegraff, and McHale, 1999). Parents and adolescents were asked a series of questions and follow-up probes regarding adolescents’ daily experiences with peers. Parents received a score of 2 if their entire answer matched the adolescent’s, a score of 1 if their initial answer matched but the probe did not, and a score of 0 if there was no match. The scores across the three items were averaged and converted to percentages to indicate agreement between parents and adolescents.

Parents’ Time Spent in Activities with Adolescents and Their Friends

Parents’ time with adolescents and friends was assessed by daily activity data collected during the phone interviews. Specifically, during each phone call adolescents reported on the duration (in minutes) and companions in eighty-six daily activities. The number of minutes that adolescents reported participating in activities with their mothers and one or more of their peers was aggregated across the seven phone calls to measure mothers’ time with adolescents and their friends. A parallel measure was created for fathers’ time with adolescents and their peers. We used adolescents’ reports because youth participated in all seven phone calls, whereas parents participated in only four. Correlations between parental and adolescent reports of parents’ time with adolescents and their peers for the four phone calls in which they both participated were r = .84 (for mothers’ time) and r = .86 (for fathers’ time).

Results

We conducted cluster analysis to identify groups of families who differed in their education and orientation toward both Mexican and Anglo culture and then examined the links between cluster groups and (1) parents’ backgrounds and neighborhood qualities, (2) parental cultural values, and (3) parents’ role in adolescent peer relationships. Mothers and fathers in this project reported similar cultural orientations (r = .68, p < .001 for Anglo orientation and r = .62, p < .001 for Mexican orientation) and education level (r = .64, p < .001). Thus we created average scores for parents’ education and Anglo and Mexican orientation and then standardized these scores to conduct the cluster analysis. Cluster analysis (using Pearson’s correlation similarity measure and the average linkage method) revealed three conceptually distinct groups (see Table 4.1). The same three groups emerged using Ward’s clustering method and squared Euclidian distance as our similarity measure; 86 percent of families were classified into the same pattern by both methods, χ² (4) = 302.7, p < .001.

Table 4.1.

Means (and Standard Deviations) of Cluster Variables, Background Characteristics, Neighborhood Characteristics, Cultural Values, and Parental Involvement, by Cluster

| Mexican-Oriented, Less Educated (n = 118) | Anglo-Oriented, More Educated (n = 86) | Mexican-Oriented, More Educated (n = 40) | F (2, 240) = | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster Variables1 | ||||

| Parent education | −.79 (.71)a | .72 (.60)b | .81 (.47)b | 174.10** |

| Parent Anglo orientation | −.67 (.61)a | 1.13 (.45)b | −.45 (.57)c | 277.49** |

| Parent Mexican orientation | .62 (.44)a | −1.02 (.92)b | .37 (.44)c | 164.65** |

| Background Characteristics | ||||

| Annual family income (in dollars) | 37,142 (37,392)a | 77,326 (40,764)b | 50,830 (54,295)a | 23.16** |

| Family size | 5.78 (1.34)a | 5.03 (.96)b | 4.93 (.80)b | 14.34** |

| Neighborhood Characteristics | ||||

| Percentage of families in poverty | 12.57 (7.87)a | 6.39 (6.80)b | 7.65 (6.15)b | 19.85** |

| Perception of neighborhood safety | 3.00 (.47)a | 3.33 (.44)b | 3.18 (.47)b | 12.99** |

| Percentage of adults w/o high school diploma | 23.77 (14.30)a | 11.78 (11.22)b | 14.35 (11.65)b | 23.49** |

| Cultural Values | ||||

| Family support/closeness | 4.72 (.21)a | 4.63 (.29)a | 4.62 (.32)a | 4.08* |

| Family as referents | 4.47 (.38)a | 3.99 (.40)b | 4.34 (.38)a | 38.70** |

| Family obligations | 4.46 (.40)a | 4.16 (.38)b | 4.34 (.39)a | 15.32** |

| Respect for family | 4.44 (.38)a | 4.31 (.30)b | 4.26 (.41)b | 5.66** |

| Parental Involvement2 | ||||

| Restricting peer relationships | 3.02 (.21)a | 2.29 (.29)b | 2.69 (.32)c | 28.36* |

| Knowledge about peer activities | 46.88 (.38)a | 50.61 (.40)b | 44.40 (.38)a | 2.84** |

Note: Means with different superscripts differ significantly at the p < .05 by the Student-Newman-Keuls follow-up tests.

p < .05

p < 01.

Means for cluster variables are standardized.

Because of missing data, F (2,238) for restricting peer relationships, and F (2,233) for knowledge about peer activities.

We conducted three (cluster group) ANOVAs to examine differences in income and neighborhood qualities. To test for differences in parents’ cultural values, we conducted three (cluster group) by two parent (mother versus father) mixed-model ANOVAs with parent as the within-group factor. Finally, differences in parental role in adolescent peer relationships were examined with a series of three (cluster group) by two (adolescent sex) by two (parent: mother versus father) mixed-model ANOVAs. We focus only on findings that involve cluster group differences. Means are presented in Table 4.1.

Anglo-Oriented, More Educated Families

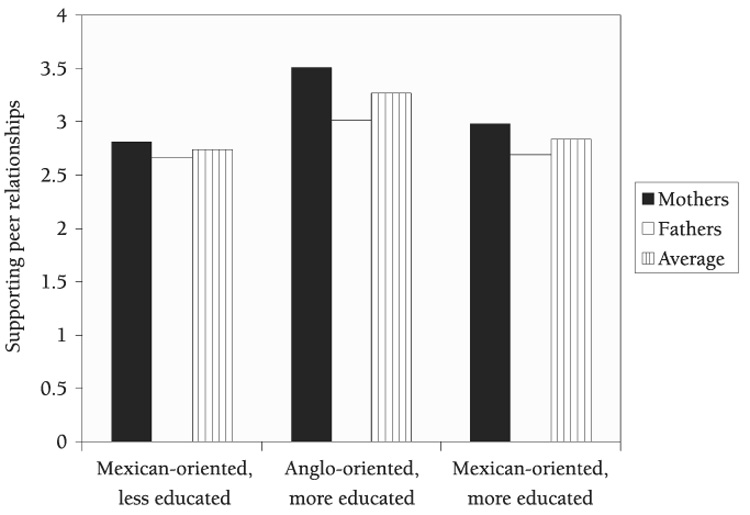

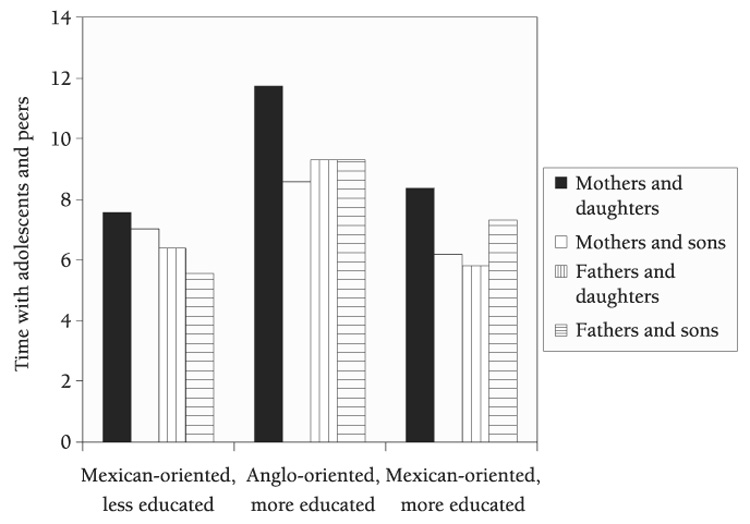

Families in the Anglo-oriented, more educated cluster (n = 86) had strong ties to Anglo culture, above-average education level, and the lowest Mexican orientation. Parents in this group were most likely to speak English (79 percent) and were most often born in the United States (91 percent). These families had the highest annual family income and lived in neighborhoods with a smaller percentage of families in poverty, and adults without high school education. Parents in this group endorsed lower familism values than those in the other groups, and lower values regarding respect than Mexican-oriented, less educated parents. They reported the highest level of support for peer relationships, F (2,238) = 21.13, p < .001; the least restrictions, F (2,238) = 28.36, p < .001; and the most knowledge about adolescents’ daily activities with peers, F (2,233) = 2.84, p = .06. In addition, a cluster × parent effect and follow-up analyses revealed that mothers described themselves as more supportive of adolescents’ peer relationships than did fathers in this group, F (2,238) = 4.02, p < .05 (see Figure 4.1). A cluster × parent × adolescent sex interaction revealed that parents, particularly mothers, spent more time with same-sex offspring and their peers, F (2,232) = 4.26, p < .05 (see Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.1.

Mothers’, Fathers’, and Parents’ Average Reports of Supporting Peer Relationships, by Cluster

Figure 4.2.

Mothers’ and Fathers’ Reports of Time with Daughters and Peers and Sons and Peers, by Cluster

Mexican-Oriented, Less Educated Families

The second cluster included 118 families who were strongly oriented toward Mexican culture and had below-average Anglo orientation and education level. Families in this group also had the lowest income and were significantly larger in family size than the other two groups. They lived in neighborhoods that included a higher percentage of families in poverty and adults without high school education than families in the other two groups. Parents also perceived their neighborhoods as the least safe. In addition, parents in this group had strong ties to Mexican culture. All but two parents spoke Spanish as their primary language, 97 percent of parents were born in Mexico, and parents held strong beliefs regarding familism and respect. These parents described less support for and knowledge about peer relationships than did parents in the Anglo-oriented, more educated group and reported the most restrictions on adolescents’ peer relationships. Mothers spent more time in shared activities with adolescents and peers than did fathers, regardless of whether or not they had a son or a daughter (see Figure 4.2).

Mexican-Oriented, More Educated Families

The last cluster group included forty families who had a high education level, moderately strong Mexican orientation, and below-average Anglo orientation. These families were similar to the Anglo-oriented, more educated families and significantly different from Mexican-oriented, less educated families in family size and in neighborhood characteristics. Family income for this group fell between the other two. In terms of cultural background, these parents predominantly spoke Spanish (88 percent) and were born in Mexico (98 percent) but were more differentiated in their cultural values than families in the Mexican-oriented, less educated group. Their values regarding respect were similar to Anglo-oriented, more educated families, whereas values regarding familism were similar to Mexican-oriented, less educated families. Parents reported less support and knowledge about peer relationships than parents in the Anglo-oriented, more educated group but their restrictions on peer relationships were moderate, with the mean falling between and differing significantly from the other two groups. Parents spent more time with their same-sex offspring and peers (see Figure 4.2).

Discussion

An important goal of this chapter was to explore how within group variations in Mexican-origin families’ cultural and ecological backgrounds were linked to parental roles in adolescent peer relationships. This approach moves beyond the study of Mexican-origin families as a monolithic group to consider important diversity that exists within this ethnic group. Differences among families in their cultural background, adherence to Mexican cultural values, and connection to Anglo culture are important sources of within-group variability in how families adapt to the two cultures in which they spend their time. An equally important source of variation in these families is their socioeconomic resources. Both cultural and ecological factors shape the nature of parents’ involvement with adolescents and their peers.

We found that parents in these three clusters differed in their cultural backgrounds and values, socioeconomic resources, and involvement in adolescents’ peer relationships. Parents in the Mexican-oriented, less educated group described strong cultural values and had the most limited socioeconomic resources. They also placed the most restrictions on adolescents’ peer relationships and described themselves as the least supportive of and knowledgeable about these relationships. This pattern is consistent with our expectations that parents who have values consistent with Mexican culture and more limited socioeconomic resources may be less likely to encourage adolescents’ peer relationships. The strong emphasis on turning to family members for support and obligations, and potentially for financial support, may mean that parents encourage connection with nuclear and extended family and are less able or willing to promote relationships with youth outside the family.

The Mexican-oriented, more educated group had more socioeconomic resources, similar values toward family, and lower values regarding respect than did parents in the Mexican-oriented, less educated group. These parents placed moderate restrictions on adolescents’ peer relationships and were similar to Mexican-oriented, less educated families in support for and knowledge about adolescents’ peer relationships. Parents in the Anglo-oriented, more educated group, in contrast, had the lowest values regarding family obligation and family members as referents and respect for others, and they had more socioeconomic resources than Mexican-oriented, less educated families. These parents expressed the greatest level of support for peer relationships, the least restrictions, and the most knowledge. Because these parents placed less emphasis on family-oriented values, it is possible that they were more invested in their youth’s relationships outside the family. Their more extensive economic resources may have enabled them to provide young people with more opportunities to interact with peers, such as participating on sports teams or in extracurricular activities.

Future Directions

An important next step is to delineate the processes underlying the connections between family ecology and parental role in adolescent peer relationships. In hypothesizing about the influences of socioeconomic status on parenting, Hoff, Laursen, and Tardif (2002) proposed that the physical and social settings of family life are important to consider. The parents in this study who placed the greatest restrictions on youth peer involvement also lived in neighborhoods characterized by higher levels of poverty and lower perceived safety and had more limited economic resources than did parents who placed fewer restrictions on peer relationships. Placing restrictions on adolescents’ peer relationships may reflect a more general approach to parenting that serves to protect youth from risks imposed by their immediate social contexts. Exploring how specific elements of the neighborhood context (for example, adult supervision of youth activities) as well as specific aspects of adolescents’ neighborhood peer networks (for example, peer involvement in risky behavior) will provide additional insights about how the neighborhood context may shape parents’ roles in adolescent peer relationships.

An equally important issue for future research is the role of cultural processes in shaping the involvement of mothers and fathers in Mexican-origin adolescents’ peer relationships. Parents’ language fluency and discrepancies in language usage among parents, adolescents, and peers are likely to affect how parents are able to be involved in adolescent peer relationships. It is notable that the group of parents who were most supportive of, placed the fewest restrictions on, and had the most knowledgeable about adolescents’ peer relationships was also the group most likely to be fluent in English (the language spoken by the majority of adolescents in this study). Being unable to converse in the language commonly used by adolescents and their peers may affect parental involvement in adolescents’ peer relationships. Brown, Bakken, Nguyen, and Von Bank (Chapter Five) noted similar patterns among Hmong parents who lacked confidence in their English skills and struggled in their efforts to manage young people’s peer relationships.

A related question about the role of cultural processes concerns the cultural background of adolescents’ peers. In this study, the majority of parents had strong ties to Mexican culture and may have provided greater support for peers if the peers also identified strongly with Mexican culture. Along these lines, Mounts and Kim (Chapter Two) found that Latino parents (of predominantly Mexican origin) preferred that their offspring form friendships with other Latino youth. Parents may believe that involvement with Mexican-origin peers can promote ethnic socialization opportunities and reinforce family cultural traditions. As Mounts and Kim (Chapter Two) and Way, Greene, and Mukherjee (Chapter Three) propose, learning about the parenting goals and beliefs that underlie parental management practices would advance our understanding of the antecedents of parental roles in adolescent peer relationships. Virtually no information is available about parents’ goals and beliefs regarding adolescents’ peer relationships in Mexican-origin families.

Values shared by members of the same social class are also important to consider. Parents in middle-class families are described as valuing autonomy and independence to a greater degree than parents in low-income families (Dornbusch and others, 1987; Hoff, Laursen, and Tardif, 2002). Values regarding independence may lead to greater support for peer relationships, to the extent that allowing youth to develop ties outside of the family represents their increasing autonomy. Kohn (1977) highlights the role of occupational conditions in the values of middle-class versus working-class parents, suggesting that the work environment of low-income parents emphasizes obedience and conformity and the environment of middle-class parents promotes independence and autonomy. More information is needed on values linked to the individualistic orientation that characterizes U.S. culture and on occupational values that may influence parent socialization.

Gathering additional information about the active role of adolescents in encouraging parents’ involvement in their peer relationships is another direction of future research. Brown, Bakken, Nguyen, and Von Bank (Chapter Five) illuminate how adolescents share information that underscores their active role in the process. Adolescents can encourage parental involvement in their peer relationships by sharing information and by seeking advice and support for their peer relationships. They also may actively enlist parents to offer transportation to activities with peers, and thus foster opportunities to spend time with their peers. Considering adolescents’ role as well as the reciprocal influences of both parents and adolescents in shaping parents’ involvement will be fruitful lines of inquiry.

These findings are a first step in exploring how characteristics of family ecologies are linked to within-group variations in Mexican-origin parents’ roles in adolescent peer relationships. An important next step is to identify the processes mediating the relations between broader contextual forces and the specific roles Mexican-origin parents assume in adolescents’ peer relationships. It will also be important to examine how parenting in these family ecologies is related to young people’s peer relationships over time.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01 HD39666 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Cowden Endowment to Arizona State University. The authors wish to thank Susan McHale, Ann Crouter, Nancy Gonzales, Mark Roosa, Emily Cansler, Melissa Delgado, Devon Hageman, Jennifer Kennedy, Lilly Shanahan, and Lorey Wheeler for their assistance in conducting this investigation, and the families and school districts for their participation.

References

- Berry J. Conceptual Approaches to Acculturation. In: Chun K, Organista P, Marín G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and Applied Research. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez M. Latino Families: Myths and Realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino Children and Families in the United States. New York: Praeger; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Helms-Erikson H, Updegraff K, McHale SM. Conditions Underlying Parents’ Knowledge About Children’s Daily Lives in Middle Childhood: Between-and Within-Family Comparisons. Child Development. 1999;70:246–259. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans—II: A Revision of the Original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch SM, et al. The Relation of Parenting Style to Adolescent School Performance. Child Development. 1987;58:1244–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Magnuson KA. Off with Hollingshead: Socioeconomic Resources, Parenting, and Child Development. In: Bornstein MH, Bradley RH, editors. Socioeconomic Status, Parenting, and Child Development. Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll CG, et al. An Integrative Model for the Study of Developmental Competencies in Minority Children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, et al. Acculturation and the Mental Health of Latino Youths: An Integration and Critique of the Literature. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino Children and Families in the United States. New York: Praeger; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hart CH, et al. Peer Contact Patterns, Parenting Practices, and Preschoolers’ Social Competence in China, Russia, and the United States. In: Slee P, Rigby K, editors. Peer Relations Amongst Children: Current Issues and Future Directions. London: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E, Laursen B, Tardif T. Socioeconomic Status and Parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting, Vol. 2: Biology and Ecology of Parenting. 2nd ed. Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, et al. Family Socialization and Mexican American Identity and Behavior. In: Bernal ME, Knight GP, editors. Ethnic Identity: Formation and Transmission Among Hispanics and Other Minorities. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, et al. The Mexican American Cultural Values Scale. 2007 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn ML. Class and Conformity: A Study in Values, with a Reassessment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson D. The Logic and Implications of a Person-Oriented Approach. In: Bergman LR, Cairns RB, editors. Methods and Models for Studying the Individual. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marín B, Marín B. Research with Hispanic Populations. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- McAdoo HP, editor. Family Diversity: Strength in Diversity. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage; [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, et al. Siblings’ Differential Treatment in Mexican American Families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1259–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Changing Demographics in the American Population: Implications for Research on Minority Children and Adolescents. In: McLoyd VC, Steinberg L, editors. Studying Minority Adolescents: Conceptual, Methodological, and Theoretical Issues. Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mounts NS. Parental Management of Adolescent Peer Relationships: What Are Its Effects on Friend Selection? In: Kerns K, Contreras J, Neal-Barnett A, editors. Family and Peers: Linking Two Social Worlds. Westport, Conn.: Praeger; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mounts NS. Adolescents’ Perceptions of Parental Management of Peer Relations in an Ethnically Diverse Sample. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:446–467. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell L, Stueve A. Mothers as Social Agents: Structuring the Community Activities of School Aged Children. Research in the Interweave of Social Roles: Jobs and Families. 1983;3:113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, et al. Managing the External Environment: The Parent and Child as Active Agents in the System. In: Kuczynski L, editor. Handbook of Dynamics in Parent-Child Relations. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Morgan-Lopez AA, Cree WK, Specter MM. Sources of Influence on Latino Families and Children. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino Children and Families in the U.S. New York: Praeger; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, et al. Family and Child Characteristics Linking Neighborhood Context and Child Externalizing Behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:514–528. [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F. Hispanic Familism and Acculturation: What Changes and What Doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Kurtines WM. Family Psychology and Cultural Diversity: Opportunities of Theory, Research, and Application. American Psychologist. 1993;48:400–407. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Crouter AC, Kupanoff K. Parents’ Involvement in Adolescents’ Peer Relationships: A Comparison of Mothers’ and Fathers’ Roles. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:655–668. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, et al. Adolescent Sibling Relationships in Mexican American Families: Exploring the Role of Familism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:512–522. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]