Abstract

Trained as an engineer and a chiropractor, William D. Harper, Jr. made his career in the healing arts as instructor, writer and president of the Texas Chiropractic College (TCC). A native of Texas who grew up in various locales in the Lone Star State, in Mexico and in the Boston area, he took his bachelor’s and master’s degree in engineering in 1933 and 1934 from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and his chiropractic degree at TCC in 1942. Dissatisfied with the “foot-on-the-hose” concept of subluxation syndrome (D.D. Palmer’s second theory), Dr. Harper studied and wrote about aberrant neural irritation as an alternative explanation for disease and for the broad clinical value he perceived in the chiropractic art. In this he paralleled much of D.D. Palmer’s third theory of chiropractic. His often reprinted textbook, Anything Can Cause Anything, brought together much of what he had lectured and written about in numerous published articles. He was well prepared for the defense of chiropractic that he offered in 1965 in the trial of the England case in federal district court in Louisiana. The case was lost when the court ruled that the legislature rather than the judiciary should decide whether to permit chiropractors to practice, but Harper’s performance was considered excellent. He went on to guide the TCC as president from 1965 through 1976, its first 11 years after relocating from San Antonio to Pasadena, Texas. Harper built the school – its faculty, staff and facilities – from very meager beginnings to a small but financially viable institution when he departed. Along the way he found fault with both chiropractic political camps that vied for federal recognition as the accrediting agency for chiropractic colleges in the United States. Dr. Bill Harper was a maverick determined to do things his way, and in many respects he was successful. He left a mark on the profession that merits critical analysis.

Keywords: Harper, chiropractor, Texas Chiropractic College

Abstract

Ingénieur et chiropraticien de formation, William D. Harper Jr. a fait sa carrière dans le domaine de la guérison en qualité d’instructeur, d’auteur et de président du Texas Chiropractic College (TCC). Originaire du Texas, il a grandi dans des diverses villes du Texas, du Mexique et de l’agglomération de Boston. Il a obtenu son baccalauréat et sa maîtrise en génie en 1933 et 1934 de Massachusetts Institute of Technology et, en 1942, a obtenu son diplôme de chiropraticien du TCC. Peu satisfait du concept « foot on the hose » (« pied sur le boyau ») du syndrome de subluxation (la deuxième théorie de D. D.Palmer), le Dr Harper a étudié et écrit sur le sujet de l’irritation neurale aberrante comme une explication de rechange pour les maladies et pour la valeur clinique plus vaste qu’il a vu dans l’art chiropratique. En ce sens, il a suivi une trajectoire semblable à celle de la troisième théorie de D.D.Palmer. Son ouvrage « Anything Can Cause Anything » (« Tout pourrait causer tout »), qui a eu plusieurs réimpressions, a regroupé la plupart de ses cours et de ses articles publiés. Il était bien préparé pour la défense de la chiropratique qu’il a présentée en 1965 dans « le procès England » au tribunal du district fédéral en Louisiane. Il n’a pas eu gain de cause parce que le tribunal a statué qu’il en revenait à la législature plutôt qu’à la magistrature de trancher sur le sujet de l’autorisation aux chiropraticiens d’exercer leur profession. La prestation du Dr Harper devant le tribunal a été considérée excellente. Il a ensuite dirigé le TCC en tant que président du 1965 au 1976 – les premières 11 ans de l’institution après sa relocalisation de San Antonio à Pasadena, Texas. On a attribué au Dr Harper la construction de l’école – sa faculté, son personnel et ses installations. Avant de partir, le Dr Harper a veillé à ce que cette école, qui a connu des débuts modestes, devienne une institution qui, malgré sa petite taille, était financièrement rentable. Il a également critiqué les deux camps politiques de la chiropratique qui rivalisaient pour obtenir la reconnaissance fédérale pour devenir l’organisme d’accréditation pour les institutions d’études chiropratiques aux États-Unis. Le Dr Bill Harper était un non conformiste, déterminé de poursuivre à sa façon, une philosophie dont il a réussi sous plusieurs aspects. Il a profondément marqué la profession qui mérite de l’analyse critique.

From Texas to Boston

William David Harper, Jr., a maverick who characterized himself as “the man that chiropractic developed,” entered the world in humble circumstances: “in a shack on a railroad siding on a cold winter night, Nov. 28, 1908” in Big Spring, Texas (1). An autobiographical account, contributed at the request of Joseph Janse, D.C., N.D. and written in the third person, described some of his family background:

His father … had come to Texas via Missouri after the Civil War. His forebears were a part of the Harper’s Ferry incident in Virginia and, in traveling west, mixed it up with the Indians. Bill says his father talked a lot about Geronimo, the great Indian fighter, and thinks this may have been the tribe. In any case, Bill is a good part Indian and proud of it. He thinks the Indians got a bum deal and that Custer got what he deserved at the Little Big Horn. At least they were willing to fight and die for what they believed in, and this may be the part of what drives Bill Harper to seek out the truth and fight for it …

Bill’s father had grown up in West Texas and, for a time, was a scout for the Texas Rangers, but in 1908 he had a contract to photograph the right of way for the T&P Railroad in West Texas … Bill’s father told him that he came out feet first, and that his head just about didn’t make it. Both of them nearly died that night, but the good doctor must have been a genius to save their lives under such circumstances.

Bill wasn’t doing too well after nearly getting his head torn off, and the doctor recommended a higher altitude, so the family ended up in Queretaro, about 100 miles north of Mexico City, Mexico. His father, who was a mechanical genius and inventor, had a contract to motorize the street railway system in Mexico city; but Diaz was dictator and, after two years, the family was advised to get out of Mexico while the trains were still running. They made it on the last train before they blew up the works.

While in Mexico, Bill improved and learned to talk – guess what – Spanish, because he had a Mexican nurse. He came out of Mexico to San Antonio … jabbering Spanish, to the dismay of his grandmother who was quite frustrated about the whole deal. Bill says he can remember thinking in Spanish and talking in English as he learned the language (1).

His father studied dentistry and built a traveling dental clinic that visited many small towns between San Antonio, Falfurias and Rio Grande City. For a time young Bill attended Lukin Military Academy in San Antonio, until America’s entry into World War I, when “the family moved to Rio Grande City, and his father served as a dentist to the soldiers at Fort Ringold, and Bill entered public school and got back into Spanish again with the children” (1). After the armistice in 1918, he accompanied his father on his clinic tours while his mother served as “Superintendent of Schools in Alamo Heights in San Antonio” (1). The youngster enjoyed hunting and marksmanship, developed talent in playing the clarinet and saxophone, and picked up a knack for solving mechanical problems from his father and uncle Ted (a blacksmith).

His father’s invention of an improved truck body suspension prompted a relocation to Boston in 1921, where Bill studied at the Huntington Preparatory School. Some four years later the family moved again to nearby Wellseley Hills, Massachusetts and Bill commenced pre-medical studies at Boston University. He eventually transferred to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and after several false starts completed his studies in engineering, in which he earned a B.S. in 1933 and an M.S. in 1934 (2). Along the way he further developed the problem-solving talent inherited from his dad and a work ethic that prompted him to do “just a little more than is necessary” (1).

While a student at MIT a chance encounter with a chiropractor led him to seek adjustive care for a severe case of hay fever. Intrigued with the benefit he received, Harper returned to San Antonio in 1939 with his new bride, the former Madeline Morse, and enrolled in the Texas Chiropractic College (1), a small, for-profit institution founded in 1908 (3). Since 1924 the Texas Chiropractic College (TCC) had been owned and operated by three decidedly “straight” chiropractors: President James R. Drain, D.C., a 1912 Palmer graduate (4, pp. 286–7), Vice President Charles B. Loftin, D.C., a 1921 TCC alumnus (4 p. 310), and Dean Herbert E. Weiser, D.C., who had taken his chiropractic degree from the Palmer School of Chiropractic (PSC) in 1920 (5). Although their attitudes about the limited scope of practice of chiropractors would be somewhat softened during the 1940s by the introduction of Concept-Therapy (6), they were politically allied with the PSC and other, smaller, straight chiropractic institutions, such as the Cleveland College of Kansas City and the Ratledge College of Chiropractic in Los Angeles. Bill’s chiropractic education was therefore devoid of instruction in the broader scope of healing arts (e.g., physiotherapies) taught at “mixer” schools, such as the National College of Chiropractic in Chicago, the Western States College in Portland, Oregon and the Los Angeles College of Chiropractic (7). Harper presumably received some training in diagnosis, but it was primarily focused on subluxation-detection. He noted that he had been class president, president of the Delta Sigma Chi fraternity, “Valedictorian and had a 98.2% average in all courses; and he had more patients in the Clinic than he could take care of” (1).

When Pearl Harbor was bombed by the Japanese on 7 December 1941, Bill was just a few months shy of completing his chiropractic studies. He asked for an early graduation so that he could return to the Boston area and serve his country on the home front. Dean Weiser granted this request, and on 5 January 1942 he and his wife set out by automobile for Massachusetts. He went to work for the Springfield Machine and Foundry Co. in Springfield, where he served as assistant plant manager. The company was producing “triple expansion steam engines” for the Liberty ships that carried war supplies for the Allies to all parts of the globe. Harper later took great pride in having solved a vexing manufacturing problem for the crankshafts that propelled these large, slow vessels; his solution was distributed to all other manufacturers of these engines. He believed his engineering approach provided a potent strategy for doctoring as well: “if you assemble all the facts concerning a problem, in these facts you will see the answer. Bill has applied this same reasoning to diagnosis in chiropractic, which is nothing more than problem solving” (1).

Dr. Harper’s work at the foundry brought his newly acquired chiropractic skills into play:

Bill did many other things in this plant to cut down the time of production, but he feels that a major contribution was in getting them [employees] back to work when they got hurt. This was heavy industry, so there were a lot of strains and sprains. The company had two M.D.s on the staff and a clinic. Bill became friendly with the M.D.s and his office was next to the clinic. One day, a man had lifted something and strained his back. He walked in under his own power but, after laying on a hard table for x-rays, he couldn’t get up. The x-rays were negative, and the M.D.s asked Bill for help.

After asking a few questions, Bill decided it had to be 1L and that it was inferior on the left side, as the man was right-handed and the muscle pull from the pelvis is on the left side to compensate for lifting with the right hand. With pressure to the superior on the left side of the 1L, the man could lift his legs, sit up and walk around. Bill asked the M.D.s if he should continue, and they agreed.

Bill pointed out that chiropractors were not licensed in Massachusetts and that he would be practicing medicine illegally. The older M.D. said, “Hell, the important thing is to fix the patient if you can do it … who cares what you are practicing.” The other concurred. So Bill adjusted his 1L and the man walked out quite happy and to the relief of the M.D.s. This turned out to be a valuable experience because, besides his engineering duties, Bill was carrying on a practice under the M.D.s’ licenses for the rest of the war (1).

Although Massachusetts did not license chiropractors until 1966, Bill practiced there in the postwar era – and apparently without any legal repercussions. Like many DCs in unlicensed jurisdictions, he sought credentials from other states. He eventually acquired basic science certificates from Iowa and Texas and “Chiropractic licenses in Maine, New Hampshire and Texas” (8).

Even while he practiced at the foundry, Harper began to question the theories he had been taught at TCC. The notion that “pressure on a nerve at the IVF shut off impulses, and this was the cause of disease,” he believed, “didn’t check with the facts of anatomy and physiology or with the clinical findings of pain, muscle contraction and visceral dysfunction, which cannot occur with no impulses. There was something wrong somewhere” (1). In coming years he wrote repeatedly about the conflict he found between the basic sciences and traditional chiropractic theory, for example:

… These principles were broad enough to cover everything, but somewhere along the line someone who didn’t understand them invented the hose theory, or the pinched nerve, as the explanation for obtained results in the clinic. This theory, which also involves a decrease in impulses, is in conflict with physiologic and anatomic facts and is a poor substitute for the real thing.

This is what the writer was taught in college, and it was not until he got out into practice that he began to question the validity of this theory in view of the facts.

In spite of this, we have survived because what we were doing was right most of the time, even though the reasons given were wrong, and we have succeeded in becoming the second largest branch of the healing arts (9). [boldface emphasis added]

Harper was unaware that the “hose theory” had originated with D.D. Palmer – who later abandoned it. In the postwar period he established a private practice in Wellesley Hills, and it was during this time that he acquired a copy of Palmer’s 1910 tome, The Chiropractor’s Adjuster: the Science, Art and Philosophy of Chiropractic (10). In this book he encountered the founder’s third theory of chiropractic, which was much more to his liking. Rather than the hypothesized interruption of neural impulses at the intervertebral foramen, Harper now decided that “most diseases were the result of too many impulses,” and that such excesses were attributable to “mechanical, chemical and psychic irritation of the nervous system” (1). These were the notions that he would profess for the rest of his life.

Palmer’s Several Theories

Not well known to most chiropractors (and not appreciated by Dr. Harper) were the variety of theories, originating in magnetic healing and progressing through three distinct versions of chiropractic, that Palmer had offered during the 27 years (1886–1913) of his career as a healer (11–16). As a magnetic Palmer had arrived at the idea that inflammation was the essential characteristic of all disease, and that inflammation was a consequence of the friction produced when anatomic parts were out of their proper position within the body. Palmer sought to relieve inflammation by pouring his excess, vital magnetic energy into the diseased part (17), much as one might pour coolant into or onto a gear-box that has overheated because of an improperly positioned axle. It was a mechanical explanation for the etiology of disease, and a vitalistic or “subtle energy” (18) concept of the relief of disease.

The first theory of chiropractic (see Table 1), which “Old Dad Chiro” created and developed during 1896–1903, was seen as a distinct improvement over magnetic healing. In magnetic practice, he reasoned, one must wait for the inflammation to arise in order to apply the remedy. In first-stage chiropractic, on the other hand, one could manipulate the body in order to adjust the displaced anatomic part to its proper position, thereby preventing the friction and inflammation from occurring in the first place.

Table 1.

D.D. Palmer’s concepts during three periods of publications.*

| Concept | The Chiropractic a (1897–1902) | The Chiropractorb (1904–06) | The Chiropractor Adjuster;c The Chiropractor’s Adjuster (1908–10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| circulatory obstruction? | Yes | No | No |

| nerve pinching? | Yes | Yes | No |

| foraminal occlusion? | ? | Yes | No |

| nerve vibration? | ? | ? | Yes |

| therapeusis? | Yes | No | No |

| method of intervention? | manipulation | adjustment | adjustment |

| innate/educated? | absent | nerves; Intelligence | Intelligence |

| religious plank? | absent | absent | optional? |

| machine metaphor? | Yes | Yes | Yes & No |

| tone? | (vital) | absent | Yes |

The Chiropractic was the title of D.D. Palmer’s advertising flier during the early years of his practice in Davenport, Iowa

The Chiropractor was the title of the journal published by D.D. Palmer and son B.J. Palmer from the Palmer School in Davenport beginning in December 1904.

The Chiropractor Adjuster was the title of D.D. Palmer’s journal published in Portland, Oregon by the D.D. Palmer College of Chiropractic, while The Chiropractor’s Adjuster was the title of his book.

This table is adapted from one appearing in Keating JC. Old Dad Chiro comes to Portland, 1908–10. Chiropractic History 1993 (Dec); 13(2):36–44 (13).

Perhaps partly as a consequence of the increasing criticism he received from the osteopathic community, which suggested that Palmer had stolen a fraction of osteopathy and repackaged it as chiropractic, Old Dad Chiro sought to better differentiate his methods from those taught by Andrew Taylor Still at the American School of Osteopathy in Kirksville, Missouri. In July 1903, while teaching and practicing in Santa Barbara, California (14), Palmer made a “discovery” which he felt was no less significant than that embodied in the Harvey Lillard case (19) some years earlier. He described the event in the first issue of The Chiropractor, published by the Palmer School in December 1904:

Who Discovered That the Body is Heated by Nerves During Health and Disease?

It will be of interest to “The Chiropractor” reader to learn how Dr. D.D. Palmer discovered that the body is heat by nerves, and not by blood.

In the afternoon of July 1, 1903, in suite 15 of the Aiken block, Santa Barbara, Cal., D.D. Palmer was holding a clinic. The patient was Roy Renwick of that city. There were present as students, H.D. Reynard, Ira H. Lucas, O.G. Smith, Minora C. Paxson, A.B. Wightman and M.A. Collier, in all told, eight witnesses.

The patient, A.R. Renwick, had the left hand, arm, shoulder and on up to the spine, intensely hot. Dr. Palmer drew the attention of the class to the excessive heat condition of the portion named; the balance being normal in temperature. He then gave an adjustment in the dorsal region which relieved the pinched nerve on the left side, also the excessive heat of the left upper limb; but he had thrown the vertebra too far, which had the effect of pinching the nerves on the right side, and immediately causing the upper limb to be excessively hot. He asked the class, “Is the body heat by blood or by nerves?” he then left them for two or three minutes. He returned and asked them, “Is the body heat by blood or by nerves?” The class unanimously answered “Nerves.” Thus was this new thought originated.

The above circumstance is substantiated by a letter written that evening to the doctor’s son, B.J. Palmer, D.C., also several following letters which further explained that the caloric of the body, whether normal or in excess, was furnished by calorific nerves. These letters were placed with other original writings in one of the ten bound volumes in order to prove the autobiography of Chiropractic from its birth. Here are the original writings which show beyond the shadow of a doubt who originated the principle of Chiropractic. The doctor’s son anticipated that some sneak thief would try to appropriate the credit of originality, and would desire to rob his father of the honor justly due him, thus, his reason for compiling his original writings (10, pp. 485–9; 628–30; 20).

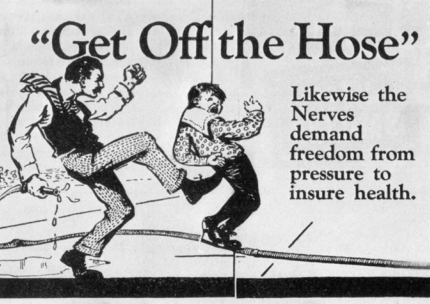

This incident marked Palmer’s abandonment of his first theory and the introduction of his second. No longer did D.D.’s theory concern any displaced anatomic part (including arteries and veins); he was now focused squarely on bones-pinching-nerves, primarily in the intervertebral foramen. His terminology also changed: he no longer identified himself as a “magnetic manipulator” or a “chiropractic” (21); Palmer was now a chiropractor, and he referred to his manual interventions exclusively as adjustments. Son B.J. Palmer, D.C. adopted the well known “foot-on-the-hose” metaphor for this second theory, and would ever after offer this concept – and his personal variations on the theme (such as spine-only and eventually upper-cervical-spine-only) – as his father’s theory of chiropractic. Father and son parted company in 1906 (15), and B.J. did not follow the continuing conceptual development that constituted D.D. Palmer’s third theory.

The elder Palmer’s third theory, articulated in the two books he authored after his estrangement from his son (10, 22), rejected his own second theory (what Bill Harper would often refer to as the “hose theory”). In his final iteration of chiropractic thought, the founder contended that nerves were never pinched in the intervertebral foramen, but could instead be impinged when any joint in the body became subluxated. Such impingement caused nerves to become too taut or too slack, thereby altering the vibrational frequency of the nerve. End-organs served by overly tense nerves became inflamed; end-organs receiving too little neural input owing to the slackening of a nerve would manifest decreased function. These notions were subsequently elaborated by French chiropractor and historian Pierre-Louis Gaucher-Peslherbe, D.C., Ph.D. (1943–1996) in his doctoral dissertation in the history of medicine. Dr. Gaucher-Peslherbe suggested that D.D. Palmer’s theory proposed the skeletal frame as a regulator of systemic neural tension (23).

Bill Harper was reviewing Palmer’s third theory and had begun his published contributions on the subject while Gaucher-Peslherbe was still a child (see Table 2). As early as 1947 he commenced writing papers that dealt with Palmer’s final theory as a basis for diagnosis (8, 24, 25). His 1954 article dealing with the concept of cellular irritability (26) was central to many of his subsequent treatises on chiropractic theory, assessment and treatment. Irritability, he wrote was a primary characteristic of all cells, and involved the ability to react to stimuli according to the functions for which the cell had differentiated (e.g., nerve cells propagate impulses, endocrine cells release hormones, muscle cells contract). Cells could be irritated by normal (e.g., neural) or abnormal stimuli (e.g., toxins, psychic factors, physical injuries), and an irritated cell might increase or decrease its function depending on the character and extent of the irritating stimulus. He quoted from a physiologist of the day (27) that “the power of protoplasm to respond to an environmental change is known as irritability” and “Irritability is a fundamental property common to all protoplasm and, in consequence, we employ it as a diagnostic property by which we tell the living from the dead” (26). In the concept of irritability Harper believed he had found a physiologically correct alternative to the “hose theory” that B.J. Palmer (and other chiropractors) continued to espouse.

Table 2.

Several published papers of William D. Harper, Jr., M.S., D.C. (sole author except where otherwise indicated).

| A physiological basis for diagnosis. National Chiropractic Journal 1947 (Apr); 17(4):19–20 |

| A physiological basis for diagnosis. TCC News Letter 1951 (Aug); Issue No. 97, pp. 7, 14–5 |

| A physiological basis for diagnosis. ICA International Review of Chiropractic 1952 (May); 6(11):4–5, 32 |

| What is chiropractic? TCC News Letter 1952 (July); Issue No. 100, pp. 14–23 |

| The basic science subjects are a part of chiropractic. TCC News Bulletin 1952 (Dec); Issue No. 101, pp. 20–22 |

| Why basic science subjects are a part of chiropractic education. Journal of the National Chiropractic Association 1953 (Mar); 23(3):9, 64, 66, 68 |

| Clarifying the term “irritation” and its relationship to the chiropractic premise. Journal of the National Chiropractic Association 1954 (Nov); 24(11):9–11, 68–71 |

| The right of determination. TCC Newsletter 1955 (May); Issue No. 107, pp. 6–7 |

| The chiropractic subluxation vs. the medical subluxation. Journal of the National Chiropractic Association 1955 (Sept); 25(9):18–20, 66, 68, 70, 72–5 |

| Posture is a symptom. TCC Newsletter 1956 (May); Issue No. 109, pp. 4–5 |

| Today’s lesson: fundamental philosophy never changes. TCC News Letter 1956 (Aug); Issue No. 110:4–5 |

| Basic principles never change. TCC News Letter 1957 (Nov); Issue No. 112, pp. 17–9 |

| Proper rationalization with facts gives reason to definition. TCC News Letter 1958 (Mar); Issue No. 113, pp. 8, 13, 15 |

| Are we going to – - ? TCC News Letter 1959 (Jan); Issue No. 115, pp. 13–5 |

| Are we going to do something constructive? TCC News Letter 1959 (Oct); Issue No. 116, pp. 7, 14 |

| The importance of uterine control in delivery for normal childbirth: delivery as a normal physiological function can be aided by the doctor of chiropractic. Journal of the National Chiropractic Association 1961 (Jan); 31(1): 29, 63–7 |

| Comments on whiplash. TCC News 1961 (Oct); 2(3): 3, 5 |

| Research: are we professionally ready for it? TCC News 1962 (Jan); 3(1): 3 |

| Many cry for a research program but few are willing to support it. Journal of the National Chiropractic Association 1962 (Feb); 32(2): 10–11, 64 |

| Comments on whiplash. California Chiropractic Association Journal 1962 (Nov); 19(5): 13–4 |

| The subluxation. California Chiropractic Association Journal 1962 (Dec); 19(6): 8–14 |

| Is there a place for Innate in scientific terminology? Journal of the National Chiropractic Association 1963 (Feb); 33(2): 32–4, 67–71 |

| A thought for the new year. TCC News 1963 (Feb); 3(3): 2 |

| Insurance vs. $10.00 a month. TCC News 1963 (Feb); 3(3): 2 |

| T.C.C. fund drive starts. TCC News 1963 (Mar); 3(4): 1, 4 |

| Accreditation—our obligations. TCC News 1964 (Jan); 4(1): 1–2 |

| A way of life. TCC News 1964 (Feb); 4(2): 1–2 |

| Relation of dermatitis to kidney dysfunction. Texas Chiropractor 1964 (June); 21(8): 18–21 |

| The new look. Texas Chiropractor 1964 (Sept); 21(12): 12–4 |

| In memoriam: Dr. Frances. TCC News 1964 (Oct); 4(5): 4 |

| The only way. TCC News 1964 (Oct); 4(5): 5–6 |

| Thoughts for the new year. TCC News 1965 (Feb); 4(6): 1, 4 |

| Report of activities. Texas Chiropractor 1965 (Mar); 22(5): 6–7 |

| In tribute to Dr. Joseph J. Janse. ACA Journal of Chiropractic 1965 (May); 2(5): 18, 44, 46 |

| President’s report. TCC News 1966; October: 2–3 |

| Diagnosis- science or fiction? Texas Chiropractor 1966 (Nov); 24(1): 5, 30–1 |

| Go back to go forward? Texas Chiropractor 1967 (Apr); 24(6): 6–7, 26–7 |

| Letter to the editor. Texas Chiropractor 1967 (Apr); 24(6): 20 |

| A tribute to the pioneers of our profession. California Chiropractic Association Journal 1967 (Sept); 24(3): 23–4 |

| Principles. California Chiropractic Association Journal 1968 (Apr); 24(10): 15–21 |

| Intuition: basis of diagnosis. California Chiropractic Association Journal 1968 (May/June); 24(11–12): 17–8, 27–8 |

| The diagnostician. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1968 (Sept/Oct); 11(2):34–6 |

| The diagnostician. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1969 (Jan/Feb); 11(4):28–30 |

| The diagnostician. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1969 (Mar/Apr); 11(5):30–2 |

| Follow up on diagnosis. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1969 (May/June); 11(6):24–9 |

| The trap. Lifeline 1969; July: 1 |

| Ernest G. Napolitano, TCC homecoming speaker. Lifeline 1970; July: 1 |

| The learning process. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1970 (July/Aug); 13(1):20–2, 24–5, 58–9 |

| College accreditation protection and guarantees. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1970 (Nov/Dec); 13(3): Supplement H, 51 |

| Diagnosis: a science or fiction? Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1971 (May/June); 13(6):28–30 |

| Texas Chiropractic College receives full ACA accreditation. TCC News 1971; July: 1 |

| Into thy hands, we deliver … TCC News 1971; Sept; 2 |

| TCC research and development fund. TCC News 1971; Sept; 6–7 |

| Autonomy. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1972 (July/Aug); 15(1):18–20 |

| Additional commentary on accreditation: the elusive dream. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1972 (Sept/Oct); 15(2):50–3, 55 |

| Texas Chiropractor editor honored. Texas Chiropractor 1972 (Oct); 29(10):8–9 |

| Student news: Texas College. ACA Journal of Chiropractic 1972 (Nov); 9(11):45 |

| Have you considered? Texas Chiropractor 1972 (Nov); 29(11):6, 23 |

| Medicare: the implication, the effect and impact on the future of the chiropractic profession. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1973 (Jan/Feb); 15(4):20–2, 24–5 |

| Let us take the initiative. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1973 (Mar/Apr); 15(5): 38–41, 44–5 |

| A new concept. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1973 (May/June); 15(6): 40–1 |

| TCC goes to 2-year pre in Aug. ’74. Texas Chiropractor 1973 (Sept); 30(9): 23–4 |

| Bittner, Helmut; Harper, William D.; Homewood, A. Earl; Janse, Joseph; Weiant, Clarence W. Chiropractic of today. ACA Journal of Chiropractic 1973 (Nov); 10(11): 35–42 (S-81 through S-88) |

| Iatrogenic complications and the germ theory. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1973 (Nov/Dec); 16(3): 46–7 |

| The science of existence. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1974 (Jan/Feb); 16(4): 50, 52–4 |

| Who are you supporting: chiropractic or medicine? Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1974 (July/Aug); 17(1): 48–9, 52 |

| The position of the D.C. in comprehensive health planning. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1974 (Sept/Oct); 17(2): 54–5 |

| Anything can cause anything. Third Edition. Seabrook TX: 1974 |

| Medical diagnosis—a trap. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1975 (Jan/Feb); 17(4): 14–5, 17–8, 20–3 |

| What is important? Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1975 (Sept/Oct); 18(2): 14–5, 17 |

| President’s message. TCC Review 1976 (Feb); 2(1): 4 |

| The cover. TCC Review 1976 (Apr); 2(2): 3 |

| President’s message. TCC Review 1976 (Apr); 2(2): 4 |

| President’s message. TCC Review 1976 (July); 2(3): 4 |

| Mine eyes have seen the glory: Americans wake up! TCC Review 1976 (July); 2(3): 5–6 |

| Doctor of Chiropractic—wake up! TCC Review 1976 (July); 2(3): 6–8 |

| President’s message. TCC Review 1976 (Sept); 2(4): 4 |

| Commitment. TCC Review 1976 (Sept); 2(4): 6 |

| N.O.W. TCC Review 1976 (Oct); 2(5): 4 |

| Thanks for giving. TCC Review 1976 (Oct); 2(5): 5–6 |

| Your education—what is it worth to you today? TCC Review (Feb); 3(1): 6 |

| T.C.C. 1966–1977, a review. TCC Review 1977 (June); 3(3): 15–7 |

| Count your blessings. TCC Review 1978 (Oct); 4(5): 9–10 |

Teaching in Texas

In early 1949 Dr. Jim Drain paid a visit to Bill in the Boston area while on his way to lecture at a chiropractic convention New Hampshire. Aware that Harper had a master’s degree (academic degrees were increasingly demanded by the educational reformers in the profession), his mentor proposed that Bill spend a summer in San Antonio where he might teach and study at his alma matter while various members of the faculty took their vacations. The engineer-chiropractor departed by air for Texas on 26 July 1949 “and never went back” (1).

The Texas College had undergone a number of significant changes since Bill Harper’s graduation in 1942. The passage of a chiropractic statute in 1949 required that students accumulate two years of “pre-professional” (i.e., liberal arts) college education in addition to their chiropractic studies as a condition for licensure in the Lone Star State. To that end, the TCC had entered into an articulation with the nearby San Antonio Junior College, whereby students admitted with less than the two years of preprofessional training could complete this work concurrently with their chiropractic courses. The chiropractic curriculum was also expanding to meet the statutory requirements and to come up to the standards expected by the National Chiropractic Association’s (NCA’s) Council on Education (CoE) – a forerunner of today’s CCE-USA. After years as a for-profit institution, TCC now operated on a non-profit basis, and Dr. Drain’s position as president had become largely ceremonial. The College was directed by its administrative deans: Ben L. Parker, M.A., D.C. (1949–1951) and his successor, Julius Troilo, B.A., D.C. (1952–1965). In 1962 Dr. Troilo’s position was redesignated “president” by the College’s board of regents, which was chaired from 1960 through 1978 by James M. Russell, D.C., a 1948 graduate of TCC (and future co-founder of the Association for the History of Chiropractic).

Dr. Harper related that during his first 15 years with the College he taught “just about every course at T.C.C.” (1). This is not at all improbable, given that faculty members might come and go (or be unavailable due to the need for practice income to supplement their meager teaching salaries) and that Bill was among the more extensively educated of the TCC’s instructors (see Table 3). Less likely – but not impossible – is his assertion that students attending the local junior college were encountering conflict between their basic science coursework and the “hose theory” taught at the TCC. Harper related that Dean Troilo had grown concerned about this, and had assigned Bill to teach physiology and chiropractic principles in order to find a resolution to the discrepancies. Whatever the accuracy of this account, it seems clear that Dr. Bill Harper relished his role as intermediary between the basic sciences and clinical chiropractic concepts. Dr. Troilo was apparently pleased with Bill’s work, repeatedly invited him to accompany him to meetings of the NCA’s CoE (e.g., 30, 31), and named him assistant dean circa 1961.

Table 3.

Faculty of the Texas Chiropractic College, 1950 (based on: 28, 29).

| R.A. Anderson, M.A., D.C., Ph.C. | William D. Harper, Jr., M.S., D.C. | Ciro Ramirez, M.A., D.C. |

| Clatis W. Drain, D.C., Ph.C. | Theo S. Holm, A.A., D.C., Ph.C. | Henry E. Turley, B.S., D.C., Ph.C. |

| James R. Drain, D.C., Ph.C. | Charles B. Loftin, D.C., Ph.C. | Julius C. Troilo, B.A., D.C., Ph.C. |

| Ruth A. Eklund, R.N., B.A., D.C., Ph.C. | Henry Nelson, B.S., D.C., Ph.C. | William B. Weatherford, D.C. |

| Russell H. Gunderson, D.C. | Ben L. Parker, M.A., D.C., Ph.C. | Herbert E. Weiser, B.S., D.C., Ph.C. |

The early 1960s brought great tragedy for Dr. Harper. His elderly parents grew ill, and his wife developed cancer. Aiding him in these difficult times was a former student, 1957 TCC alumna Bobbie N. Rogers, R.N., D.C., who took over Bill’s practice while he repeatedly visited his parents in Boston. Bobbie also cared for his wife Madeline during her hospitals stays. Harper’s wife and parents passed away. Bill and Bobbie tied the knot on 22 November 1962; he fondly described his new bride as “one Hell of a woman” (1).

Beyond the Lone Star State

Harper was a popular figure on the lecture circuit. Chiropractic periodicals of the 1950s and early 1960s suggest that he was increasingly well known throughout the United States, not only for his personal appearances at various state conventions and relicensure seminars, but also for the increasing volume of his articles, which were often reprinted in several state journals. His ability to present his ideas about chiropractic in authoritative and comprehensible manner also brought him invitations to testify in various civil and criminal courtrooms, typically in the defense of chiropractors tried for malpractice or unlicensed practice (e.g., 32–34). He was no less popular at home, and his fellow Texan chiropractors honored him in 1961 by awarding the “Keeler Plaque” (35), equivalent to being named the state society’s “Chiropractor of the Year.”

The best remembered of Dr. Harper’s courtroom appearances took place in Louisiana in 1965, shortly after the first publication of his book, Anything Can Cause Anything (ACCA) (36). Jerry England, D.C. (after whom the case was named) and several other chiropractors in the Pelican State had been struggling with the state’s medical society and the board of medical examiners for nearly a decade (37–39) in an effort to break the stranglehold that organized medicine held over the chiropractic profession. Relevant statues and court rulings held that the practice of chiropractic was – per se – the practice of medicine, and could only be engaged in by those licensed to practice medicine.

The chiropractors’ legal challenge in the England case made its way through various state and federal courts, during which time the arrests of DCs had been suspended while the legal issues were adjudicated. The chiropractors, championed by TCC alumnus Paul J. Adams, D.C. (who served as chairman of the state society’s legal action committee) and represented by attorney J. Minos Simon, hoped for a federal court decision that would overrule the state courts’ findings. A significant part of Simon’s strategy was an attempt to demonstrate legally that chiropractic was a useful profession, and that the state should not prevent the people of Louisiana from benefiting from chiropractic services.

Mr. Simon engaged Dr. Joseph Janse, who since 1945 had served as the president of the National College of Chiropractic (NCC), to testify as an expert witness for plaintiff chiropractors. Although reports in the chiropractic media of that time described Janse’s performance on the stand in glowing terms – including one account penned by Dr. Harper (40) – the truth of the matter was something different. As Janse himself later acknowledged, he was humiliated on the stand (41). Counsel for the MDs hammered away not only about the lack of federally recognized accreditation for chiropractic colleges, but about Janse’s methods of dealing with serious disorders potentially beyond his scope of practice (e.g., tetanus produced by a rusty nail). Janse was “raked over the coals” (42). Crushed by the experience, he departed Louisiana determined to establish federally recognized accreditation for the National College – or leave the profession (41, 43).

On short notice, Harper was summoned from San Antonio to serve as a follow-up witness for the plaintiffs. His testimony on the stand was lauded by those in attendance, most especially by Dr. Adams:

In the recent trial of the England case I had the distinct privilege of witnessing the greatest exposition of the basic principles of chiropractic in my entire career in the profession.

On the third and final day of trial Mr. Simon put Dr. W.D. Harper on the stand as rebuttal witness. After questioning Dr. Harper for about thirty minutes he tendered him to the opposition. Their cross examination lasted for several hours. They carried him through ICA-ACA Master Plan scope of practice – no scope adopted – Journal articles – BJ’s books –accreditation (no accreditation) – how do you treat this –that – every question one could think of. Then they opened their copy of Harper’s book. They started with the title and went through the last paragraph. He was the perfect picture of confidence. He never evaded a question or hesitated. He explained and qualified everything he said with exacting biological references, the authority of which, was beyond dispute or question. Many of the exaggerations and indiscretions of our past were dragged into the open. Dr. Harper gave them the treatment they deserved in keeping with our understanding of the science of chiropractic today.

When the defense and the plaintiffs said “that is all” the judge nearest the witness chair said “you are excused Dr. Harper. Congratulations.” The MD who advised the defense counsel approached Harper with open hand and congratulated him with “Dr. Harper, that is the greatest thing I have ever heard. Can I buy your book? I want to learn.” Mr. Simon said that the cross examination of Dr. Harper and his response was the most dramatic scene he had ever witnessed in the court room.

Many more things could be said about this trial. But I thought you Texas folks would appreciate a few words from someone who lived it. In summation I can only say that Dr. Harper was fantastic. We have something in this man (44).

The allopathic physician to whom Adams referred was none other than Joseph Sabatier, M.D. (45, 46). Dr. Sabatier was then serving as president of Louisiana’s medical society, but chiropractors would come to know him as chairman of the American Medical Association’s Committee on Quackery (47, 48), whose work prompted the anti-trust suit brought by DCs in 1976 (49, 50). Sabatier’s subsequent published comments in the Journal of the American Medical Association (51) and in Medical Economics leave little doubt about his summary evaluation of chiropractic. Sabatier’s committee called for “a clear recognition of the fact that chiropractic is a political problem, not a scientific problem. It has not reached the scientific stage. Chiropractic is the greatest tribute to the efficacy of technically applied public relations the world has ever known. These people have been delivering a package since 1895, the sale of which depends entirely on the wrapping. The contents are not there” (47). Accordingly, it seems that Sabatier’s compliment of Harper was disingenuous.

There seems no doubt, however, that Bill Harper was as cool as the proverbial cucumber on the stand. For 20 years he had been studying the basic and life sciences that he believed underpinned his faith that disease was the result of excess neural irritation from psychic, toxic and/or physical insults. He had long been rehearsing, in print and in person, in the classroom and on the lecture circuit, the application of this basic science knowledge to clinical problems within the framework of his chiropractic theories. He was able to quote from reputable authorities to support his assertions about anatomy and physiology. The only things that might have interrupted his long exchange with defendants’ legal counsel were his absence phenomena (minor seizures in which he stared blankly, momentarily unaware of his surroundings, and then picked up where he’d left off). However, if any such occurred, they did not seriously mar his testimony. The Texas Chiropractor reported that:

… Fortified by his knowledge and training, his perceptive powers, his incisive speech and logical mind, accompanied by the clinical successes of our profession, and all of the help he has had from his peers, though peerless, he stood out at this moment. Dr. Harper presented one of the most outstanding and historical statements ever presented on behalf of the science of chiropractic. His testimony demonstrated a certitude of knowledge and a confidence of conviction. He was neither evasive nor reluctant, neither bold nor diffident. His was an in depth presentation of the efficacy of chiropractic therapy fortified by the findings of the outstanding authorities in pathology, physiology and anatomy. In a word it was a brilliant display of dedication and knowledge, of competence and conviction. It was a moving historical moment. Even the opposition rushed up to him to congratulate him when his testimony was concluded. No greater tribute than this can be expected. Regardless of the outcome of the case, his contribution to the profession will stand as an inspiration for those who will follow him (52).

The case for plaintiff chiropractors was lost. The court ruled that whether or not chiropractic was a useful healing art of benefit to the citizens of Louisiana, and whether or not it merited a separate and distinct practice act, was a matter for the legislature to decide. Soon thereafter Sabatier called for the arrest of chiropractors who did not hold a medical license (45). Nine more years would elapse before the DCs of Louisiana succeeded in securing a chiropractic statute.

Meanwhile, Bill Harper was called to the national scene by the newly formed American Chiropractic Association (ACA). The ACA created a panel of prominent chiropractic educators and charged them to write a coherent statement about the principles and practice of chiropractic. Joining Dr. Harper in this endeavor were Clarence W. Weiant, D.C., Ph.D., former dean of the Chiropractic Institute of New York (CINY) (53), Joseph Janse, D.C., N.D. of the NCC (54), A. Earl Homewood, D.C., N.D., former president of the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (55), and Helmut Bittner, J.D., D.C., dean of the CINY. This “Special Committee on Standardization of Chiropractic Principles” met at ACA’s new headquarters in Des Moines during 26–30 May 1965. The white paper they produced was not published until 1973 (56), for reasons that Harper – to his chagrin –could not determine (57).

When the committee convened, Harper was quite distressed that Janse, who the ACA had appointed to chair the panel, was asserting the “hose theory.” In private correspondence some years later and in his characteristically salty language, Harper described this confrontation with D.D. Palmer’s second theory:

… I stood it as long as I could and finally got the floor. I laid it on the line and said when are we going to stop all this B.S. and get down to the facts of anatomy and physiology and the other life sciences and prove that D.D. Palmer was right and that B.J. was full of #%$&, or words to this effect. At least I got their attention and Bittner of CINY immediately backed me as did Homewood and Weiant. This clobbered Janse and the majority voted that I run the meeting.

I started at the beginning with the Phy. of the N.S. and led them thru the maze with what is in ACCA which I had just rewritten and answered all their questions and proved each with facts. In fact when there was question of what I said from memory, I got the G.D. book and read it to them out of … Gray’s Anat. and Best & Taylor Phy. etc.

The end result of this was “Chiropractic of Today” which was written mainly by Homewood and Weiant I believe because I kept out of it to see what would happen and if they had gotten the idea.

It probably is the best paper that has ever been written in chiropractic … (58).

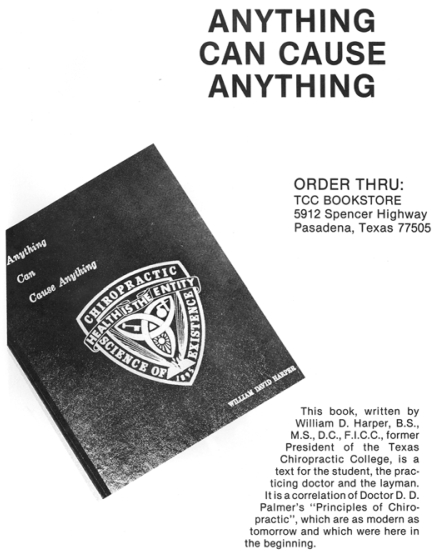

The Book

Bill Harper considered his book, ACCA, one of the most significant achievements of his career. First published in 1964, the volume went through several revisions and reprintings. Despite its homegrown (self-published) look and feel, it was the gospel according to Harper for students at TCC, where it is still available for purchase. The concepts Dr. Harper laid out in this volume were those he had played with and written about repeatedly in the 20 years prior to ACCA’s first release (see Table 2).

Harper asserted that “Dr. D.D. Palmer proved that the adjustment of the articulations of the human skeletal frame would cure disease” (36, p. 7). This idea was taken as a given, and not discussed further. In this respect, Harper demonstrated a “private and/or uncontrolled empiricism” (59). He likened this certainty to the Wright brothers’ demonstration that human flight is possible. For Harper, the scientific challenge was to determine not whether but how and why such was possible, and in so doing, to establish the principles of a science – be it aeronautics or chiropractic.

Dr. Harper further believed that the father of the profession had “established the principles that are the foundations of the Science of Chiropractic” (36, p. 7). Since Old Dad Chiro conducted no original scientific research (and Harper didn’t credit him with any such), the supposed methods for developing the principles of the Science of Chiropractic were the founder’s inquisitive mind, his reasoning and his reading of the basic sciences of his day. Harper believed that ACCA brought a greater order and clarity to the principles that D.D. Palmer had set down for chiropractic.

Although Dr. Harper’s formal education greatly exceeded that of D.D. Palmer, his engineering background had not impressed upon him the skeptical qualities of the basic or clinical scientist. Like any engineer, Bill Harper was trained as a technologist, one who had mastered the content of the “hard sciences,” such as physics, and was capable of skillfully applying this knowledge to practical problems. He believed that this sort of training and the problem-solving strategies he had acquired were relevant to the practice of the healing arts, and in this belief he may have been correct. However, his a priori commitment to belief in the clinical significance of nerve irritability and the curative value of adjusting places him at odds with the curious, doubting, skeptical attitude of the scientist.

Harper was comfortable with the concept of Innate Intelligence, and he wrote about intelligence at the organismic level and the cellular level. (Cellular intelligence referred to the ability of a cell to react to its environment and in this sense is equivalent to cellular irritability.) The vitalistic/spiritual character of these constructs is further suggested by his assertion that “A scientist can thus accept abstracts like God, life, electricity, etc.” (36, p. 5). As well, the emblem Bill created for the Texas College incorporated elements (its three corners) that he related to his Christian beliefs: “This Triad represents INNATE –THE TRINITY – THE FATHER, THE SON AND THE HOLY GHOST – THE CREATOR OF IT ALL” (36, p. xxii).

Harper’s book reveals a grandiosity that parallels that of his idol, D.D. Palmer. He described ACCA as “an attempt to show that chiropractic is an all-inclusive scientific explanation of the cause of all disease” (36, p. vii). Throughout the text he offers a variety of equations that seemingly summarize the causes of all disease in terms of a ratio between environmental stimuli and the body’s resistance to such stimuli. Harper defined disease as “a normal function that is out of time with need” (36, p. 43). Some of his ideas are reminiscent as well of B.J. Palmer, D.C. (son of the founder) and of Ralph W. Stephenson, D.C. (whose 1927 Chiropractic Textbook B.J. strongly endorsed), such as Harper’s assertion that “it is scientifically acceptable for us to define life as intellectually controlled motion” (36, p. 21). Profound and far-reaching though such pronouncements may seem, they bear little resemblance to the testable propositions that concern scientists in the laboratory or in the field.

Believing he had restated D.D. Palmer’s concepts within an acceptable, contemporary basic science framework, Harper further wrote about how his and the founder’s ideas could be put to practical use in diagnosis and treatment. For Dr. Harper, a diagnostic evaluation involved determining the abnormal stimuli (be they psychic, toxic or physical) which were inappropriately irritating the patient’s nervous system. From a practical standpoint, this assessment consisted of assembling “all evidence concerning a case and correlating this information to explain how and why the phenomenon occurred” (36, p. 71). Harper’s diagnosis was a search for etiology, that is, for the source of abnormal irritation of the nervous system. Anything, as the title of his book suggested, might be the offending stimulus. Once this task has been accomplished and the source of inappropriate irritation identified, he believed, the treatment would suggest itself. The doctor’s intervention was an effort to remove the source of inappropriate irritation.

Harper also paralleled D.D. Palmer’s thinking (10, p. 789) in his designation of the chiropractor as a physician, or that s/he should be able to successfully treat the same range of health problems as seen by a general medical practitioner. Dr. Harper asserted that the DC should be “cognizant of the needs of the patient, regardless of the legal limitations placed upon practice” (36, p. 118). Reasoning a bit beyond the founder, Harper suggested that “The miracle of chiropractic is not the adjustment, but the ability to recognize what change in environment is irritating the nervous system and fix it” (36, p. 129). Quoting from Old Dad Chiro (10, p. 698), he reasserted “We are not healers; we are fixers, adjusters.” Harper wished to extend the analogy: “We have taken too limited a view of what he meant by the term adjustment” (36, p. 130). Harper’s version of chiropractic would encompass all the healing arts:

The adjustment may be mechanical (manipulation or surgery), chemical (diet or drugs), or psychic (counsel or psychiatry). We do know that drugs and surgery do relieve irritation of the nervous system in certain cases. In comprehensive health planning we must consider a combined effort, but we can be the determiners.

What you do depends on you, but remember …

ANYTHING CAN CAUSE ANYTHING (36, p. 137)

Although Harper’s book and the concepts he offered were well received in many corners of the profession, such was not always the case among the intelligentsia. Clarence Weiant, for instance, who held doctorates in chiropractic and anthropology (53), indicated that “I esteem him greatly, but every now and then, he comes out with an expression or a statement that is sheer nonsense. For example: ‘Chiropractic is the SCIENCE OF EXISTENCE.’” (60). Harper’s concepts, as embodied in ACCA, did not impress this Palmer graduate and former TCC owner-instructor (3):

Harper explains everything, but his answers are not those of a scientist. They are closer to theology. Despite the soundness of his scientific training, in his chiropractic theorizing he violates some of the basic principles of science, particularly the rule that for a hypothesis to be valid it must deal with a problem capable of solution by further experimentation. No amount of experimentation is going to prove or disprove the concept of Innate Intelligence. The question is metaphysical, not physical (60).

Similarly, John Nash, B.S., D.C., a 1958 graduate of the TCC, respected Bill Harper as an individual, but not necessarily his ideas. Dr. Nash commenced work for his alma mater as instructor in 1966 and retired from the institution in 1987 after serving as vice president and director of the postgraduate division. Dr. Harper, he recalls, “was a brilliant person but had no clue about scientific proof” (61). He recollects that Harper, his boss from 1965 through 1977, “would take his good idea and spend his time proving it with any evidence he could find, discarding anything which opposed the idea … However, as an underling, I never would have stood up to him … he’d shoot me down with his version, especially effective since he only spoke of ideas and facts which supported his idea … I wasn’t ignorant but I certainly wasn’t skilled enough to face up to him” (61).

Others were less reluctant to take on Dr. Harper and his book. One such was Logan graduate (Class of 1965) Ronald L. Slaughter, M.S., D.C., who taught at TCC during 1974–1983 and later served as president of the National Association of Chiropractic Medicine. Dr. Slaughter recalls affectionately that Bill Harper “was quite an individual” (62). They frequently clashed during faculty meetings, and Harper fired him five times in one week. Dr. Nash recalls that Slaughter “ran head-on into Dr. Harper’s heavy handed approach with ‘Anything Can Cause Anything,’ especially his neurological discussion of Chiropractic and Visceral conditions” (63). And lest the impression be left that Harper was a heartless autocrat, there are also tales of his friendship with Dr. Slaughter, his kindness to his office staff, and his generosity to students whose finances became desperate. Bill Harper was a multi-faceted character.

The New Texas College

Back in San Antonio in 1964 the TCC was preparing for a major shift in its venue and destiny. Its campus dilapidated after nearly 40 years of use, the College found a new home: an abandoned country club in Pasadena, a suburb of Houston. After selling the San Antonio facility and paying all the College’s debts, the school was still in the black, but just barely. The board of regents decided that it could not afford the expense of two senior administrators, and asked for Dr. Troilo’s resignation. Dr. Bill Harper was named administrative dean of the TCC when it opened the doors at its new home in September 1965; the following year he was promoted to president.

For the next 12 years Bill Harper and the regents, most especially board chairman Dr. Jim Russell, struggled to raise money and increase enrollment during very lean times. The ground breaking ceremony for a new clinic in 1968 did not see a ribbon cutting until 1974, and only then because Harper brought his engineering moxie to bear on the construction plans so as to reduce costs by nearly half (1). Faculty worked for minimal salaries, and supported themselves rather more substantially in private practices. Harper, his regents and the TCC Alumni Association pleaded endlessly with the field for funding to augment the tuition revenues from a meager student enrollment. The response was underwhelming, but they somehow kept the school going on shoe-string budgets. Simultaneously, Harper was opposed to direct federal subsidy for faculty or administrative support, and to affiliation with a state university, fearing in either case that there could be a loss of control or even of identity for the chiropractic profession (64, 65). In this he paralleled the apprehensions of Dr. Earl Homewood (55).

Heavy tuition dependence was an important factor in Harper’s resentment of externally imposed standards, particularly those of the ACA-CoE. He supported the upgrading of the schools in principle (e.g., more demanding and stringent admissions requirements, better faculty and facilities), but wondered how the bills for these improvements would be paid. The TCC was a rather small school; in 1974 its enrollment of 145 students ranked eighth of ten among U.S. chiropractic colleges (66). A report in the Digest of Chiropractic Economics in early 1967 was exemplary of Harper’s sentiments:

In lieu of the usual college report carried in these pages, we present in its entirety the President’s report written by Dr. W.D. Harper of Texas College, following the meeting of the Council on Education of the A.C.A. held in Atlanta, Georgia, February 6–12.

This article presents facts that are not only true of the Texas College, but could apply equally to ALL of our Colleges. It is a plea for support to YOUR Alma Mater and to your profession.

A SPECIAL PRESIDENT’S REPORT TO THE PROFESSION

Probably the most significant meeting of the Council on Education of the A.C.A., held in Atlanta, Georgia, February 6–12, was the meeting of the Institutional members of the Council held on Tuesday evening.

Only the college presidents or their representatives were present, and the subject for general discussion was “The financial situation facing the colleges with the advent of the preprofessional requirements.” The general feeling of those present was that the colleges were being placed in a box created by professional demands, and that the profession as a whole does not recognize the problems they have imposed upon their colleges or the importance of the colleges to the growth of their profession.

First and foremost in the demand column is the one year academic prerequisite beginning a year from now (February 1968), and the two year prerequisite a year later … (67).

Harper had been a member of the NCA since 1942 (1), and the TCC had been accredited by the NCA’s CoE since the early 1950s. When the NCA evolved into the ACA in 1963–1964 (68), the Council became the ACA-CoE, and TCC continued as one of its accredited schools. However, Dr. Harper grew increasingly distressed as control of the CoE shifted from the college leaders to appointees from the national membership society. In this he was partially supported by the U.S. Office of Education (USOE), which was concerned that an accrediting body should be free from the politics of a membership society (ACA).

In 1969 Harper was one of the founders of a rival accrediting body, the Association of Chiropractic Colleges (ACC; no relation to today’s ACC), an agency that was not subordinate to ACA nor to ACA’s rival, the International Chiropractors Association. Although TCC’s membership in the ACC was brief, Harper continued to write articles for the chiropractic literature that were critical of some of the actions and positions taken by the CoE and its successor, the independently chartered Council on Chiropractic Education (today’s CCE-USA). Ironically, the CCE’s 1974 recognition by the USOE as an accrediting agency for chiropractic education in America eventually served to lessen the financial burden for all the colleges. This recognition permitted students to borrow government-guaranteed loans for their chiropractic training. Consequently, enrollments grew and several new schools emerged in the 1970s: ADIO (now defunct), Life, Northern California (now Palmer West), Pacific States (now Life West), Parker, Pasadena (defunct) and Sherman (7). As a CCE-accredited college (see Table 4), TCC immediately reaped some of the benefits of CCE’s federal standing.

Table 4.

Chiropractic colleges’ status with the Council on Chiropractic Education in June, 1975 (69)

| College | Status with CCE |

|---|---|

| Anglo-European College of Chiropractic | Affiliate |

| Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College | Affiliate |

| Cleveland Chiropractic College of Kansas City | Letter of Intent |

| Cleveland Chiropractic College of Los Angeles | Letter of Intent |

| Columbia Institute of Chiropractic | Has applied for RCA* Status |

| Life College of Chiropractic | Letter of Intent |

| Logan College of Chiropractic | Letter of Intent |

| Los Angeles College of Chiropractic | Accredited |

| National College of Chiropractic | Accredited |

| Northwestern College of Chiropractic | Accredited |

| Palmer College of Chiropractic | Has applied for RCA* Status |

| Sherman College of Chiropractic | Has applied for Correspondent Status |

| Texas Chiropractic College | Accredited |

| Western States Chiropractic College | Recognized Candidate for Accreditation |

RCA: Recognized Candidate for Accreditation

The William David Harper Clinic and Research Building was dedicated on the TCC’s campus in April 1974, while Dr. Harper was still serving as president. Faculty member David Mohle, M.Ed., D.C. penned a report of the event for the Texas Chiropractic Association’s monthly magazine:

One of the most significant events in the history of the Texas Chiropractic College took place on April 4, 1974, when the new William David Harper Clinic and Research Building was officially dedicated. In the words of Dr. James Russell, Chairman of the Board of Regents, “We are dedicating this building in honor of a man whose contribution to the chiropractic profession will not be fully appreciated for many years to come. Dr. Harper’s correlation of the principles of D.D. Palmer with the life sciences has led to a new and more accurate system for diagnosis and treatment of human ills. And his dedication to this college and to the upgrading of its academic standards has made this institution second to none.” …

Our research laboratory was designed from scratch by C.D. Anderson, Ph.D., microbiologist and mycologist. It has but one function: to prove the scientific validity of the Chiropractic premise that environmental irritation of nervous system by mechanical, chemical and psychic factors is cause of disease.

All we need now is the continuing support of the profession as we strive to build what may not be the largest but certainly will be the greatest Chiropractic Center in the world.

In final analysis, this profession will stand or fall on the scientific validity of its principles, regardless of any other recognition it may receive (70, 71).

The new building included space for laboratory research, and several successive investigators were hired to conduct “cellular research” (72) that would verify Harper’s hypotheses about cellular irritability and its role in human disease. There were suggestions too that actuarial studies of diagnostic findings (9) and other forms of clinical research might be just over the horizon. However, nothing ever came of these research ideas and apparently no substantive reports were published in the scientific literature.

In mid-1976 Bill Harper announced his intention to retire from the College presidency at year’s end. His decision was prompted by a health crisis involving hospitalization and major surgery. Perhaps at 68 years of age it was time to pass the baton; he was delighted to be named “President Emeritus” of his alma mater. He and Bobbie made plans for the sale of their Texas home and construction of a new house in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. There he would busy himself with engineering consultations, building his model train arrangements, playing his music and reminiscing. Dozens of letters written to his successor, TCC President Johnnie Baxter Barfoot, B.A., D.C., and to his longtime friend and immediate superior, former board chairman Jim Russell, reveal a keen curiosity about his alma mater. He was not reluctant to give his opinions and to offer advice. His paper trail reveals great satisfaction with the healthier financial state of the College upon his departure than when he had first taken the reins, and in this he was justified. “Wild Bill” the penny pincher had seen the school through hard times.

Harper and His Theories in Retrospect

Central to Dr. William Harper’s interpretation of D.D. Palmer’s chiropractic are the testable but still largely untested hypotheses that non-physiological irritation of the nervous system is a major cause of disease (and the corollary, that correction by removal of the inappropriate irritation by adjustment or other means relieves or prevents disease). Accepted without experimental proof by Harper and numerous chiropractors since the founder, these a priori beliefs constitute the dogma that has alienated the profession from medicine and the wider academic community. Harper reiterated his hypothesis-become-assumption many times, for example:

Let us assume that we are all agreed on the fundamental principle of our science: that pressure on, or interference with, the nervous system is the main cause of disease (8).

and

Chiropractic is a science that teaches that irritation of the nervous system is the major cause of disease … (26).

Harper’s commitment to the belief that all or most disease is caused by “environmental irritation of the nervous system by mechanical, chemical and/or psychic factors” (57) was unrelenting, and formed the platform upon which his ideology (36) was erected. His dogmatic adherence to these beliefs is also suggested by a few of the titles of his numerous papers, such as “Today’s lesson: fundamental philosophy never changes” (73) and “Basic principles never change” (74).

Bill Harper was certainly not alone in his commitment to the nervous-system-gone-awry concept of disease or in his rejection of the “hose theory” in chiropractic. However, his willingness to find and relieve aberrant neural irritation by whatever means (adjusting and other methods) makes him more liberal than the founder in his scope of practice. Engineer first, Bill Harper was often the pragmatist – when he felt that doing so did not require compromise of principle.

Harper stands out for his impressive educational credentials in an era when many DCs had little more than a high school education before commencing chiropractic studies. He is exceptional also for his close approximation and commitment to D.D. Palmer’s third theory of chiropractic and for his ability to buttress the founder’s concepts with authoritative citations from the basic science literature of his (Harper’s) day. That he was able to do so from the podium, on the witness stand and in print made him all the more useful for a besieged profession seeking legitimacy in the face of repeated charges of quackery and continuing arrests.

Dr. William Harper, as the title of his book suggests, wasn’t too concerned about the misperceptions that others might form about him. He viewed the world his way, lived his life his way, and most of the time he was successful. His legacy goes beyond Anything Can Cause Anything to include the TCC, whose existence he sustained through hard times. His career as TCC president exemplifies the perseverance that enabled a small profession to survive despite meager resources and mighty enemies. He earned his place in the TCC’s Hall of Honor (75) and in the annals of chiropractic history.

Figure 1.

The Alamo; from the 1930 edition of the Texas Chiropractic College yearbook, the Dixie Chiro.

Figure 2a.

Front view of the San Antonio campus of the Texas Chiropractic College at 618 Myrtle Street, San Pedro Park, 1930.

Figure 2b.

Dr. James R. Drain, circa 1940.

Figure 2c.

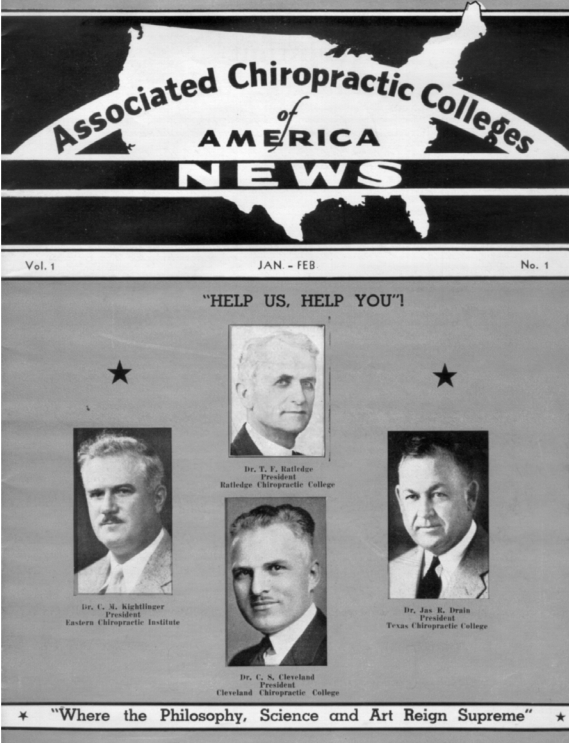

Cover of the first issue of the ACCA News, 1938, featured the presidents of four straight chiropractic colleges.

Figure 3.

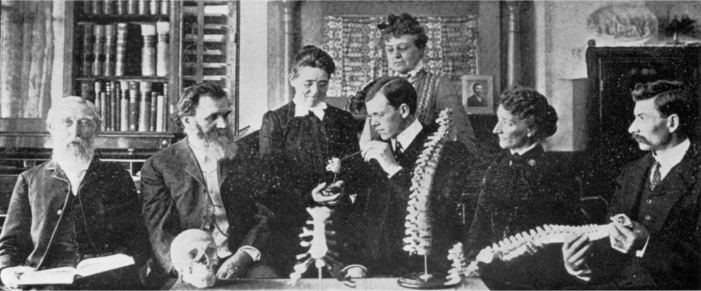

This image of D.D. Palmer’s 1903 class in Santa Barbara appeared in the first issue of The Chiropractor for December 1904; caption reads: “(Note:- The cut on Page 13 was the class present when nerve heat was first announced. From left to right they were: Lucas, ‘Old Chiro,’ Collier, Smith, Wright, Paxson, Reynard)”.

Figure 4a.

Cartoon from a catalog issued by the Palmer School of Chiropractic, circa 1925 provides a visual metaphor of the supposed mechanism of subluxation syndrome.

Figure 4b.

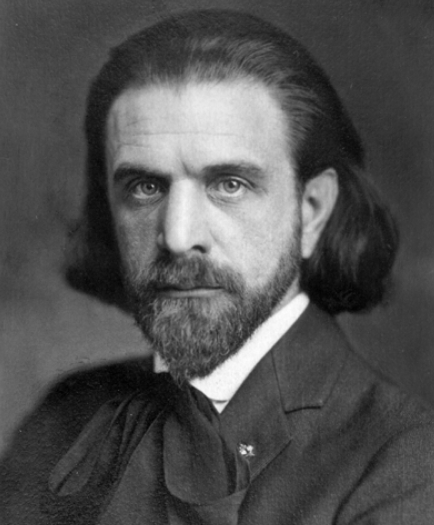

Dr. B.J. Palmer, circa 1920.

Figure 5a.

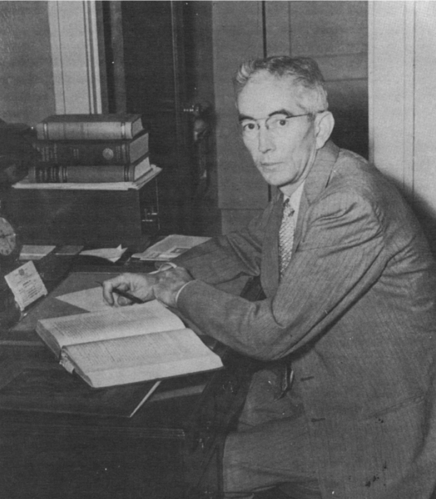

Dr. Bill Harper; from the 1951 edition of the College yearbook, the Pisiform.

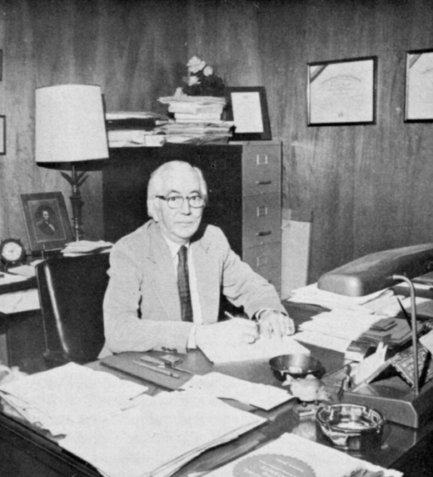

Figure 5b.

Dr. William D. Harper, Jr.; from the August 1950 issue of the TCC News Letter.

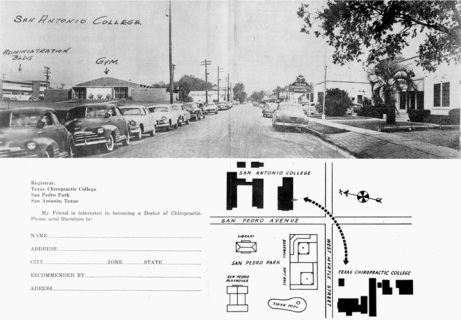

Figure 5c.

Myrtle Avenue in San Antonio was home to both the San Antonio Junior College and the Texas Chiropractic College; from the December 1952 issue of the TCC News Bulletin.

Figure 6a.

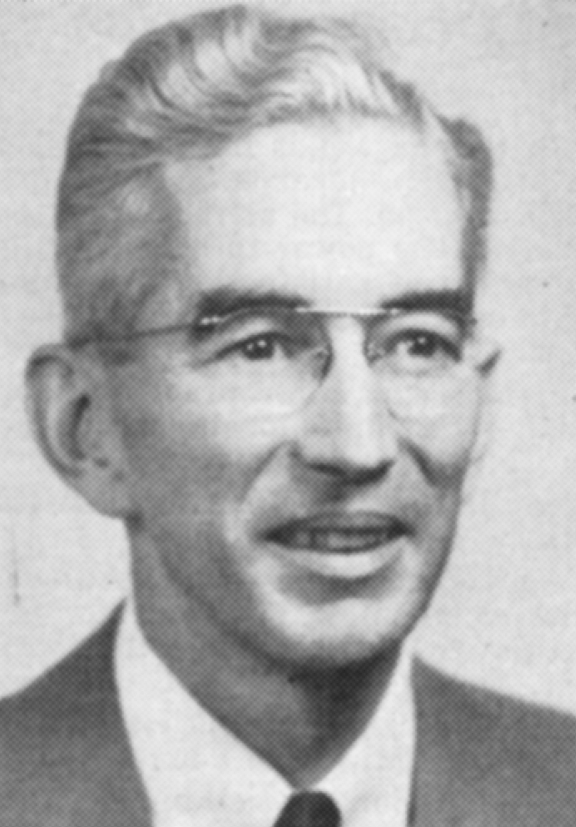

Dr. Ben L. Parker; from the June 1951 issue of the Texas Chiropractor.

Figure 6b.

Dr. Julius Troilo; from the March 1953 issue of the TCC News Letter.

Figure 6c.

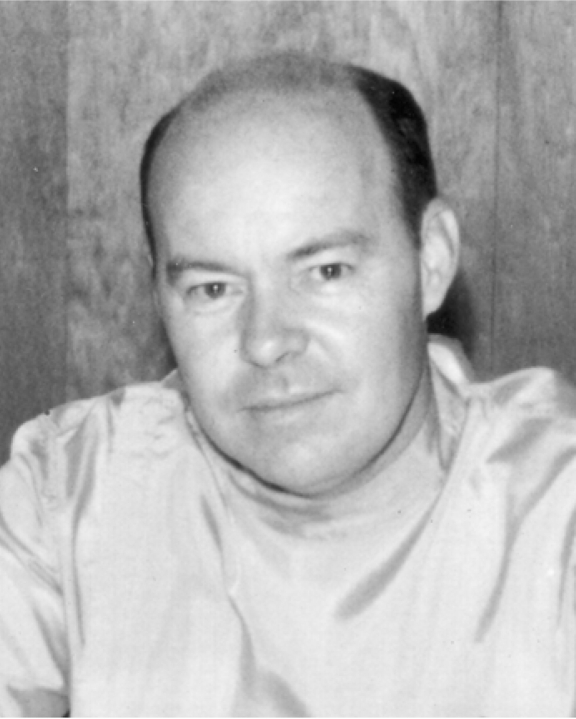

Dr. Jim Russell, 1959 (courtesy of James M. Russell, D.C.).

Figure 6d.

Dr. Clatis W. Drain; from the 1955 edition of the TCC yearbook, Pisiform.

Figure 6e.

Dr. Ruth Eklund; from the 1955 edition of the TCC yearbook, Pisiform.

Figure 6f.

Dr. Theo Holm; from the 1955 edition of the TCC yearbook, Pisiform.

Figure 6g.

Dr. C.B. Loftin; from the 1955 edition of the TCC yearbook, Pisiform.

Figure 6h.

Dr. H.E. Turley; from the 1955 edition of the TCC yearbook, Pisiform.

Figure 6i.

Dr. Herb Weiser; from the 1955 edition of the TCC yearbook, Pisiform.

Figure 7a.

Bobbie Norma Rogers, R.N.; from the 1955 edition of the TCC yearbook, the Pisiform.

Figure 7b.

Left to right are: Dr. Bill Harper of TCC; U.S. Representative from Alabama, Honorable Kenneth Roberts, and Donald O. Pharaoh, D.C. of the PSC; from the TCC Newsletter for May 1956.

Figure 8a.

Dr. William D. Harper; from the 1955 edition of the TCC yearbook, the Pisiform.

Figure 8b.

Left to right (back row) are Drs. Robert Magnuson and James Reese; left to right in front are James E. Bunker, Esq., legal counsel for the NCA and Dr. Bill Harper, invited presenter at the annual meeting of the Massachusetts Chiropractic Association; from the November 1961 issue of the Journal of the National Chiropractic Association.

Figure 9a.

Dr. Jerry England, circa 1957.

Figure 9b.

Dr. Paul J. Adams, circa 1959.

Figure 9c.

J. Minos Simon, Esq., 1964.

Figure 10.

Dr. Joseph Janse addresses the crowd during the 1969 dedication of Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College’s new campus.

Figure 11a.

Members of the ACA Committee on Standardization of Chiropractic Principles, left to right: Drs. Clarence Weiant, William D. Harper, Joseph Janse, A. Earl Homewood, and Helmut Bittner; from the July 1965 issue of the ACA Journal of Chiropractic.

Figure 11b.

This image of the ACA’s new headquarters in Des Moines appeared in the October 1964 issue of the ACA Journal of Chiropractic.

Figure 11c.

Drs. Joe Janse, Bill Harper and Bobbie Rogers Harper; from the 1968 TCC yearbook, Alpha.

Figure 12a.

This advertisement for Harper’s Anything Can Cause Anything appeared in the March 1980 issue of the TCC Review.

Figure 12b.

Emblem of the Texas Chiropractic College created by Dr. William Harper.

Figure 12c.

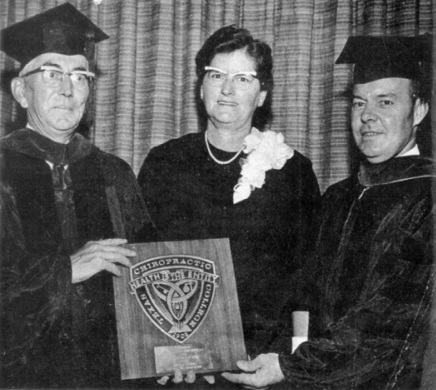

Dr. Bill Harper (left) receives an award from Texas College board chairman Dr. Jim Russell (right) during the College’s 1966 homecoming while Dr. Bobbie Rogers Harper (center) looks on.

Figure 13a.

Drs. Clarence Weiant and James Russell during enshrinement ceremonies in the TCC’s Hall of Honor, August 1981 (photo courtesy of Dr. James Russell).

Figure 13b.

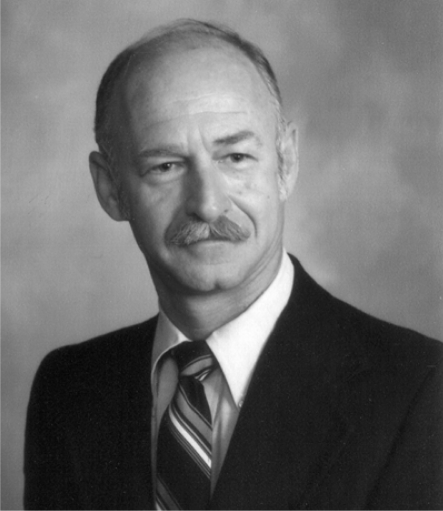

Dr. John Nash.

Figure 14.

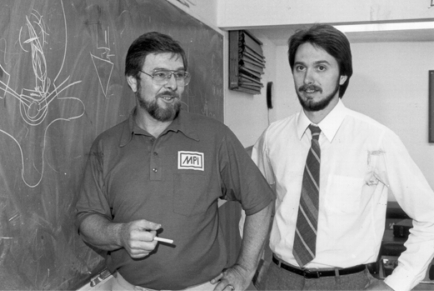

Dr. Ron Slaughter (left) and TCC senior student Richard Mikles, 1983.

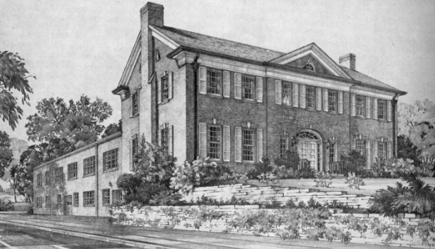

Figure 15a.

This idealized image of the Texas Chiropractic College’s Pasadena campus appeared on the cover of the August 1966 issue of the state society’s periodical, the Texas Chiropractor.

Figure 15b.

Dr. William D. Harper, Jr., from the 1968 Texas Chiropractic College yearbook, Alpha.

Figure 16.

Core faculty members and administrators of the Texas Chiropractic College (left to right) Drs. Darrel Prouse, David Ramby, Bill Harper, Johnnie Barfoot, David Mohle and John Nash; from the 1970 edition of the College yearbook, the Alpha.

Figure 17.

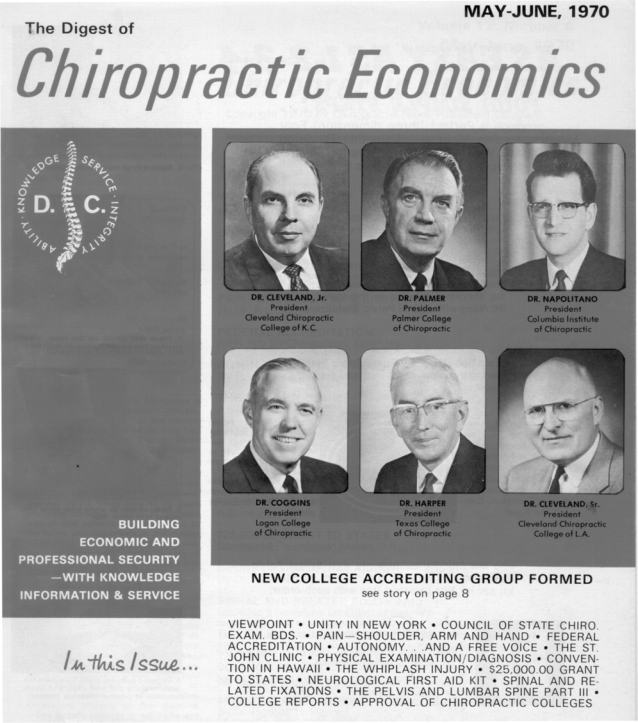

Cover of the Digest of Chiropractic Economics for May–June 1970 featured the founders of the Association of Chiropractic Colleges. Clockwise from the upper left are Drs. Carl Cleveland, Jr., David D. Palmer, Ernest G. Napolitano, Carl S. Cleveland, Sr., William D. Harper, Jr. and William N. Coggins.

Figure 18a.

Dr. Bill Harper during homecoming, August 1976; from the October 1976 issue of the TCC Review.

Figure 18b.

President Emeritus William Harper congratulates newly inaugurated TCC President Johnnie Barfoot in August 1977.

Figure 19.

Dr. William Harper; from the April 1976 issue of the TCC Review.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the librarians of the Cleveland Chiropractic College of Kansas City, the National University of Health Sciences and the Texas Chiropractic College for access to materials. My appreciation also to Carl S. Cleveland, III, D.C., Shelby M. Elliott, D.C., Brian Hawkins, D.C., John Nash, D.C., Darrel D. Prouse, D.C., James M. Russell, D.C., and Ronald L. Slaughter, M.S., D.C. for their valuable insights. My thanks as well to the National Institute of Chiropractic Research for its financial support of this project.

Some materials in this paper are derived from the book manuscript, A History of the Texas Chiropractic College, which is a work in progress. These are reproduced here with the consent of the Texas Chiropractic College.

References

- 1.Harper WD. Autobiographical sketch, unpublished, 1982. from the archives of the National University of Health Sciences; Lombard, Illinois: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dzaman F, Scheiner S, Schwartz L, editors. Who’s who in chiropractic. 2. Littleton CO: Who’s Who in Chiropractic International Publishing Co.; 1980. p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keating JC, Davison RD. That “Down in Dixie” school: Texas Chiropractic College between the wars. Chiropractic History. 1997 Jun;17(1):17–35. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rehm WS. Who was who in chiropractic: a necrology. In: Fern Dzaman, Sidney Scheiner, Larry Schwartz., editors. Who’s who in chiropractic. 2. Littleton CO: Who’s Who in Chiropractic International Publishing Co.; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hender HC, registrar of the Palmer School of Chiropractic. Letter to whom it may concern, 23 September 1943 (Special Collections, Texas Chiropractic College Library).

- 6.Keating JC, Fleet GT.Thurman Fleet, D.C. and the early years of the Concept-Therapy Institute Chiropractic History 1997June17157–65.11620052 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keating JC, Callender AK, Cleveland CS. A history of chiropractic education in North America: report to the Council on Chiropractic Education. Davenport IA: Association for the History of Chiropractic; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harper WD. A physiological basis for diagnosis. ICA International Review of Chiropractic. 1952 May;6(11):4–5. 32. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harper WD. Doctor of chiropractic – wake up! TCC Review. 1976a Jul;2(3):6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmer DD. The chiropractor’s adjuster: the science, art and philosophy of chiropractic. Portland OR: Portland Printing House; 1910. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keating JC. The embryology of chiropractic thought. European Journal of Chiropractic. 1991 Dec;39(3):75–89. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keating JC. The evolution of Palmer’s metaphors and hypotheses. Philosophical Constructs for the Chiropractic Profession. 1992 Sum;2(1):9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keating JC. Old Dad Chiro comes to Portland, 1908–10. Chiropractic History. 1993 Dec;13(2):36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]