Abstract

Background

Patient education is an essential component in quality management of the anticoagulated patient. Because it is time consuming for clinicians and overwhelming for patients, education of the anticoagulated patient is often neglected. We surveyed the medical literature in order to identify the best patient education strategies.

Methods

Study Selection: Two reviewers independently searched the MEDLINE and Google Scholar databases (last search March 2007) using the terms "warfarin" or "anticoagulation", and "patient education". The initial search identified 206 citations, A total of 166 citations were excluded because patients were of pediatric age (4), the article was not related to patient education (48), did not contain original data or inadequate program description (141), was focused solely on patient self-testing (1), was a duplicate citation (3), the article was judged otherwise irrelevant (44), or no abstract was available (25).

Data Extraction: Clinical setting, study design, group size, content source, time and personnel involved, educational strategy and domains, measures of knowledge retention.

Results

Data Synthesis: A total of 32 articles were ultimately used for data extraction. Thirteen articles adequately described features of the educational strategy. Five programs used a nurse or pharmacist, 4 used a physician, and 2 studies used other personnel/vehicles (lay educators (1), videotapes (1)). The duration of the educational intervention ranged from 1 to 10 sessions. Patient group size most often averaged 3 to 5 patients but ranged from as low as 1 patient to as much as 11 patients. Although 12 articles offered information about education content, the wording and lack of detail in the description made it too difficult to accurately assign categories of education topics and to compare articles with one another. For the 17 articles that reported measures of patient knowledge, 5 of the 17 sites where the surveys were administered were located in anticoagulation clinics/centers. The number of questions ranged from as few as 4 to as many as 28, and questions were most often of multiple choice format. Three were self-administered, and 2 were completed over the telephone. Two reports described instruments along with formal testing of the validity and reliability of the instrument.

Conclusion

Published reports of patient education related to warfarin anticoagulation vary greatly in strategy, content, and patient testing. Prioritizing the educational domains, standardizing the educational content, and delivering the content more efficiently will be necessary to improve the quality of anticoagulation with warfarin.

Background

Warfarin is a dangerous outpatient medication, by anyone's estimation. It is the second most common cause of adverse drug events in emergency rooms, and the overall risk of major bleeding averages 7–8% per year [1,2]. Despite the risk, well-established indications for warfarin are increasing in prevalence with aging of the population [3,4], and new indications for warfarin are regularly recommended [5,6]. As a result, the proportion of elderly persons taking warfarin has risen to as high as 7% [7].

Increasing a patient's understanding about warfarin is a logical goal. Prior knowledge about warfarin has been associated with a decreased risk of bleeding [8]. Written and verbal information has been shown to improve control of the level of anticoagulation [9]. While past studies suggest that patient education may be associated with better clinical outcomes, doubts remain about the effectiveness of patient education strategies [10-12]. As a result, systematic patient education regarding long-term warfarin is not universally implemented.

Our objectives were to (1) identify the published strategies (duration, timing, personnel requirements, content domains) for patient education regarding warfarin anticoagulation and (2) identify published instruments for measuring patient knowledge.

Methods

In March 2007, we searched MEDLINE using the MESH terms ("warfarin" or "anticoagulation") AND "patient education". We limited our search to articles published in the English language. We used the related articles link in PubMed and searched the references of identified citations for additional original articles. Similar search terms were used to search Google Scholar. As warfarin is by far the most commonly used oral anticoagulant, we did not seek articles related to other oral anticoagulants.

We sought articles that (a) were original research studies or descriptions of patient education programs that included information on the educational content and strategy related to anticoagulation with warfarin, or (b) contained instruments that measured patient knowledge. Exclusion criteria included studies conducted in pediatric populations, unrelated to patient education, lacking original data or an adequate program description, and those in which the educational effort was focused solely on patient self-testing. Because citations might be excluded for multiple reasons, we used this above mentioned sequence for excluding citations.

An initial search identified 206 citations. Two reviewers (JLW, MDW) reviewed titles and available abstracts to determine relevance to the stated objectives of identifying (1) the optimal educational content and delivery (duration, timing, personnel requirements), and (2) the optimal strategies for measuring patient knowledge. Full text articles were retrieved for citations that met our inclusion criteria and for those where inclusion/exclusion criteria were not determinable by the title and abstract. Two other citations were encountered during the process of reviewing articles that were deemed eligible, raising the number of eligible articles to 208.

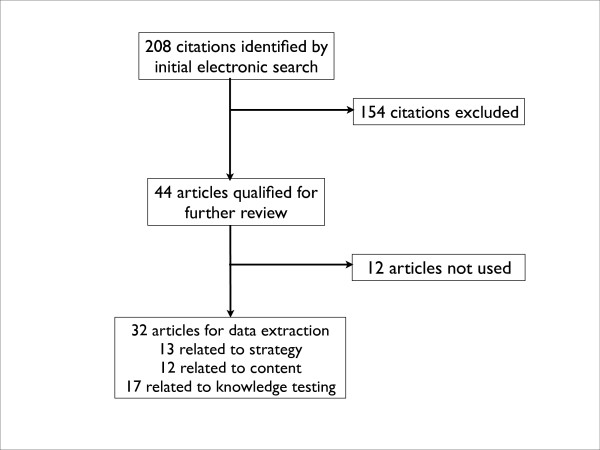

A total of 154 citations were initially excluded because patients were of pediatric age (1.9%, 4), the article was not related to patient education (23.1%, 48), did not contain original data or inadequate program description (18.8%, 39), was focused solely on patient self-testing (1), was a duplicate citation (1.4%, 3), or the article was judged otherwise irrelevant (16.8%, 35), or no abstract was available (11.5%, 24) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search strategy for studies and programs related to patient education about warfarin anticoagulation.

After exclusions, a total of 44 articles qualified for further review. Upon further review, an additional 12 articles were excluded because of inadequate program description, ultimately leaving a total of 32 articles for data extraction (Figure 1). We extracted data on clinical setting, study design, group size, content source, time and personnel involved; and created summary tables. Two reviewers (MDW, JLW) identified the educational topics covered in these reports. Among studies that tested patient knowledge, we extracted information on setting and study population, number and type of questions, and method of administration.

Results

Thirteen articles had a description of the research methods or program that was adequate and consistent with our objectives of identifying the duration, timing and setting, and personnel requirements of the educational program (Table 1) [13-25]. Five programs used a nurse or pharmacist (45%), four used a physician, and two studies used other personnel/vehicles (lay educators (1), videotapes (1)). The duration of the educational intervention ranged from one to ten sessions. Patient group size most often averaged three to five patients but ranged from as low as one patient to as much as eleven patients. While the majority of the educational efforts occurred in inpatient settings, most seemed relevant to contemporary outpatient settings.

Table 1.

Patient Education Strategies Related to Warfarin and Anticoagulation

| Citation Location Study Design | Stated Goal | Group Size | Personnel involved | Strategy/Duration/Frequency |

| Menendez-Jandula et al13 2005 Barcelona, Spain RCT | To prove the value of self-management on INR control and clinical outcomes | 5–8 patients and option of having family member present | Specially trained nurse | 2 sessions of 2 hours on consecutive days Based on German model |

| Koertke et al14 20051 Westphalia, Germany Program description | To describe the principles of a training course to learn INR self-management | Not more than 5 patients | Not stated | Welcome period Two phase (hospital, 6 months later) Average duration 3–4 hours (1.5 for theoretical and 1.5 for device handling) |

| Voller et al15 20041 Westphalia, Germany Program description | To evaluate the effects of a training program on patient knowledge | 2–5 patients | Not stated | Two half day sessions 2–7 days apart. Patient logbook |

| Khan et al16 2004 Newcastle, U.K. RCT | To prove the value of education and self-monitoring on INR control and quality of life | 2–3 patients | Led by physician | 1 two hour educational session |

| Gadisseur et al17 2003 Leiden, Netherlands RCT | To examine effects of self-management on quality of life | 4–5 patients | Specialized teams of physicians and nurses | 3 weekly sessions of 90–120 minutes |

| Singla et al18 2003 Philadelphia, U.S. Cohort Survey | To examine effects of group education on knowledge | 11 persons | Pharmacist or nurse | 1 one hour session |

| Amruso19 2003 Tampa, U.S. Program description | To examine effects of group education on knowledge | One-on-one | Chain pharmacy pharmacist | Ongoing monthly appointments |

| Beyth et al20 2000 San Francisco, U.S. RCT | To prove the value of self-management | One-on-one | Lay educator | Specifically formatted workbook. Coaching on communication skills. Self monitoring |

| Morsdorf et al21 1999 Saarland, Germany Program description | To examine the efficiency of patient training for self-management | 4–6 patients | Single MD\Single instructor | 4 theoretical and 2–6 practical sessions Video assisted demonstrations |

| Foss et al22 1999 Denver, U.S. Program description | To describe the efficiencies of a high-volume anticoagulation clinic | Not more than 6 patients | Pharm D | 1 hour slide presentation |

| Sawicki et al23 1999 Dusseldorf, Germany RCT | To prove effect of self management on accuracy of control and quality of life | 3–6 patients | Physicians and nurses | 3 consecutive weekly teaching sessions of 60 to 90 minutes in duration |

| Stone et al24 1989 Worcester, U.S. RCT | To examine the effect of videotape on knowledge | One-on-one | Nurse | 15 minute videotape compared with 25 minute nurse lecture |

| Scalley et al25 1979 San Antonio, U.S. Program description | To develop a program for patient education | One-on-one | Pharmacist or nurse | Average 30 minutes. Slide presentation and booklet. Checklist of learning objectives placed in patient's chart |

Although twelve articles offered information about education content, the wording and lack of detail in the description made it too difficult to accurately assign categories of education topics and to compare articles with one another [2,11,12,15,19,22-24,26-29]. Nevertheless, we summarized the categories suggested by these studies and listed the potential topics for each category (Table 2).

Table 2.

Topics for Education of the Anticoagulated Patient

| Category | Educational Topic |

| Basics of anticoagulation | |

| Description of the coagulation system | |

| Normal blood clotting compared with clotting of an anticoagulated patient | |

| Warfarin – mechanism | |

| Risk-Benefit | |

| Risk of bleeding versus – descriptive versus numerical | |

| Risk of clotting – descriptive versus numerical | |

| Complications of thromboemboli | |

| Adherence | |

| Color and strength of tablets | |

| What to do if dose missed | |

| Accessing healthcare professionals | |

| When to call the doctor | |

| When to seek emergency care | |

| Anticoagulation services | |

| Diet | |

| Basics of Vitamin K | |

| Specific foods | |

| Lab monitoring | |

| Basics of the INR | |

| Therapeutic INR range | |

| Most recent INR Result | |

| Interpretation of INR values | |

| Frequency of INR determination | |

| Medication interactions | |

| Antibiotics | |

| OTC medications | |

| Self-Care | |

| Injury management and contraindicated activities | |

| Signs of bleeding events (overdose) | |

| Signs of thromboembolic events (underdose) | |

| Management of minor bleeding events | |

| Medical alert bracelet | |

| Special situations – illness, travel, pregnancy, surgeries | |

| Endocarditis prophylaxis | |

| Self-testing | |

| Dose adjustment | |

| Home coagulometry | |

| Diary/quality control record keeping |

Relevant to our objective of identifying measures of patient knowledge, Table 3 shows the seventeen relevant citations [9,11,12,15,18,24,30-40]. Five of the seventeen sites where the surveys were administered were located in anticoagulation clinics/centers. The number of patients included in these studies ranged from as low as 22 to as high as 530. The number of questions ranged from as few as 4 to as many as 28 questions, and were most often of multiple choice format. Three were self-administered, and two were completed over the telephone. Two citations [12,32] described testing instruments along with formal testing of the validity and reliability of the instrument.

Table 3.

Studies Testing Patient Knowledge Regarding Anticoagulation

| Citation | Setting/Study population | Questions – Number and Type | Administration |

| Hu et al30 2006 | Large urban teaching hospital 100 mechanical valve patients | 20, True-False | Scripted telephone survey Trained medical student |

| Zeolla et al12 2006 OAK test | U.S., Recruited from 4 pharmacies and 2 clinics 122 volunteers | 20, Multiple choice, Validity and reliability testing | Self administered Excluded illiterate patients 7th grade reading level |

| Roche-Nagle, Chambers31 2006 | Dublin teaching hospital anticoagulation clinic 150 consecutive patients | 8, Specific answers | Standardized interview |

| Davis et al11 2005 | Two NYC anticoagulation clinics 52 patients | 18, Multiple choice | Self administered Single visit Excluded low literacy patients |

| Briggs et al32 2005 AKA test | Two Chicago inner city, pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinics 60 patients | 28, Multiple choice, Validity and reliability testing | Self administered Excluded illiterate patients 7th grade reading level |

| Voller et al15 2004 | Three German 3 teaching centers 76 patients | 13, Multiple choice | Questions not available |

| Nadar et al33 2003 | 3 U.K. teaching hospital anticoagulation clinics 180 patients who attended the clinic > 5 times | 9, Short answer | Language concordance, personal interview |

| Tang et al9 2003 | 1 Hong Kong anticoagulation clinic 56 patients months postdischarge | 9, Dichotomous and open-ended | 2 rehearsed pharmacy students Leading questions avoided Scoring details |

| Cheah et al34 2003 | U.S. teaching hospital center 50 inpatients | 10, Open-ended | Telephone survey |

| Singla et al18 2003 | U.S. anticoagulation center 180 patients | 4, Yes/No | Immediately after class |

| Wilson et al35 2003 | U.S. urban university hospital anticoagulation clinic 65 patients | 20, Short answer | Investigator interview one week post discharge. Instrument not available |

| Barcellona et al36 2002 | Italian thrombosis center 216 patients taking warfarin for 6 months | 6, Multiple choice | Self-administered |

| Waterman et al37 2001 | U.S. managed care organization 530 patients | 11, True-False or short answer | Telephone-based interview at enrollment |

| Wyness et al38 1990 | U.S. university hospital vascular surgery unit 23 patients | Interview soliciting explanation | Before discharge, and 1 & 3 months after discharge Oral interview |

| Stone et al24 1989 | Hospital-based anticoagulation clinic 22 patients | 18, True-False | Self-administered |

| Rankin39 1979 | University hospital cardiac rehabilitation unit 19 patients | 14, Multiple choice | 3–4 days later and 3 weeks later Investigator administered |

| Clark et al40 1972 | U.S. university hospital, 45 patients | 15, Multiple choice | Self administered |

Discussion

Patient education has long been thought to be useful for patients receiving long-term anticoagulation. Proposals have been periodically issued suggesting the content of the educational task [2,23,41]. However, inadequate attention to health education principles and educational program design have more often been the problem than have issues of content [29,42]. Despite the practical value of making the patient as knowledgeable as possible, the best strategy for educating patients about anticoagulation is yet to be determined [10].

The variety of strategies shown in Table 1 likely reflect a varying amount of support and resources devoted to this patient education goal. Delegating these educational activities to midlevel practitioners, pharmacists, or designated nurses are strategies well supported by the our literature review. However, in any given clinical setting, local factors such reimbursement and available manpower may determine which health professional(s) is best responsible for managing a population of anticoagulated patients. The advent of warfarin self-monitoring with home coagulometers has sparked renewed interest in improving patient education related to anticoagulation [2,13]. Government-supported efforts in Germany and Netherlands now devote a significant level of time and manpower to this educational task [21,43]. However, most clinical settings in the U.S. and elsewhere, may not be able to match that level of support [15]. Because most anticoagulation management still takes place in the offices of clinicians [44,45], strategies to provide education should be relevant to all clinical settings.

We also found much variability in the content areas reported by educational programs, to the degree that we could not accurately categorize educational domains, let alone make fair comparisons among programs. Some issues (manifestations of bleeding, INR monitoring, etc) were a component of most educational programs, while other issues (Vitamin K, pill color) were present only in a few. Our inability to summarize published efforts likely reflects an underreporting of details rather than extreme variability among programs. Nevertheless, our table of potential educational topics (Table 2) reflects a daunting agenda.

The testing of patient knowledge regarding warfarin and anticoagulation used a variety of instruments. Only two of the sixteen instruments – the Oral Anticoagulation Knowledge (OAK) instrument and the Anticoagulation Knowledge Assessment (AKA) – have been subject to any formal evaluation. The Oral Anticoagulation Knowledge (OAK) investigators evaluated construct and content validity, test-retest reliability, and internal consistency reliability [12]. The Anticoagulation Knowledge Assessment (AKA) investigators used the Rasch model in order to examine validity, and item and person reliability [32]. Both the OAK and AKA are reported to be written at the 7th grade reading level, but neither instrument has been validated in other clinical settings. The best strategy for measuring patient knowledge would depend, in part, on the content of the educational program, but standardization of the testing effort should be a realistic goal.

The limitations of our study deserve acknowledgement. While our study reflected a variety of different strategies for all aspects of the educational process, it is probable that noteworthy and innovative patient education efforts may not be reflected in the medical literature. Second, in reviewing these reports, it is often difficult to separate the management strategy from the educational strategy.

Despite the variability in the content and strategies of educational programs, several important issues should drive future efforts at patient education, in our opinion. Educational programs should focus on topics essential for patient safety, such as what to do when INR is high, rather than the minute details of anticoagulation that overburden the patient. Second, these programs would best be implemented with measures of effectiveness and improvement in patient knowledge, adherence and outcomes using validated instruments. Lastly, educational programs should attempt to maximize office efficiency by delegating this task to physician extenders, nurses, pharmacists, or perhaps an office-based computer.

Conclusion

Patient education is entering a new era where accountability in educational outcomes, interest in literacy/language barriers, and the importance of cost-effectiveness will influence the process of patient education. Prioritizing the educational content and using validated instruments for measuring the outcomes of patient education will be a necessary first step in improving anticoagulation outcomes. This systematic review should guide future efforts.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Please see sample text in the instructions for authors.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgements

Contributor Information

James L Wofford, Email: jwofford@wfubmc.edu.

Megan D Wells, Email: mdwells@wfubmc.edu.

Sonal Singh, Email: sosingh@wfubmc.edu.

References

- Wysowski DK, Nourjah P, Swartz L. Bleeding complications with warfarin use: a prevalent adverse effect resulting in regulatory action. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1414–1419. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.13.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell J, Jacobson A, Levy J, Voller H, Hasenkam JM, International Self-Monitoring Association for Oral Anticoagulation Guidelines for implementation of patient self-testing and patient self-management of oral anticoagulation. International consensus guidelines prepared by International Self-Monitoring Association for Oral Anticoagulation. Int J Cardiol. 2005;99:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal JB, Streiff MB, Hofmann LV, Thornton K, Bass EB. Management of venous thromboembolism: A systematic review for a practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:211–222. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglin TP, Keeling DM, Watson HG, British Committee for Standards in Haematology Guidelines on oral anticoagulation (warfarin): third edition – 2005 update. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:277–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldhaber SZ. Low intensity warfarin anticoagulation is safe and effective as a long-term venous thromboembolism prevention strategy. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;21:51–52. doi: 10.1007/s11239-006-5576-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skedgel C, Goeree R, Pleasance S, Thompson K, O'Brien B, Anderson D. The cost-effectiveness of extended-duration antithrombotic prophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:819–828. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage BF, Boechler M, Doggette AL, Fortune G, Flaker GC, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Adverse outcomes and predictors of underuse of antithrombotic therapy in Medicare beneficiaries with chronic atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2000;31:822–827. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagansky N, Knobler H, Rimon E, Ozer Z, Levy S. Safety of anticoagulation therapy in well-informed older patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2044–2050. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.18.2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang EO, Lai CS, Lee KK, Wong RS, Cheng G, Chan TY. Relationship between patients' warfarin knowledge and anticoagulation control. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:34–39. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newall F, Monagle P, Johnston L. Patient understanding of warfarin therapy: a review of education strategies. Hematology. 2005;10:437–442. doi: 10.1080/10245330500276451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis NJ, Billett HH, Cohen HW, Arnsten JH. Impact of adherence, knowledge, and quality of life on anticoagulation control. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:632–636. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeolla MM, Brodeur MR, Dominelli A, Haines ST, Allie ND. Development and validation of an instrument to determine patient knowledge: the oral anticoagulation knowledge test. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:633–638. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez-Jándula B, Souto JC, Oliver A, Montserrat I, Quintana M, Gich I, Bonfill X, Fontcuberta J. Comparing self-management of oral anticoagulant therapy with clinic management: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:1–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-1-200501040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koertke H, Zittermann A, Mommertz S, El-Arousy M, Litmathe J, Koerfer R. The Bad Oeynhausen concept of INR self-management. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2005;19:25–31. doi: 10.1007/s11239-005-0937-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voller H, Dovifat C, Glatz J, Kortke H, Taborski U, Wegscheider K. Self management of oral anticoagulation with the IN Ratio system: impact of a structured teaching program on patient's knowledge of medical background and procedures. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11:442–447. doi: 10.1097/00149831-200410000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan TI, Kamali F, Kesteven P, Avery P, Wynnes H. The value of education and self-monitoring in the management of warfarin therapy in older patients with unstable control of anticoagulation. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:557–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadisseur AP, Breukink-Engbers WG, van der Meer FJ, van den Besselaar AM, Sturk A, Rosendaal FR. Comparison of the quality of oral anticoagulant therapy through patient self-management and management by specialized anticoagulation clinics in the Netherlands: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2639–2646. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.21.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singla DL, Jasser G, Wilson R. Effects of group education on patient satisfaction, knowledge gained, and cost-efficiency in an anticoagulation center. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2003;43:264–266. doi: 10.1331/108658003321480786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amruso NA. Ability of clinical pharmacists in a community pharmacy setting to manage anticoagulation therapy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44:467–471. doi: 10.1331/1544345041475751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyth RJ, Quinn L, Landefeld CS. A multicomponent intervention to prevent major bleeding complications in older patients receiving warfarin. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:687–695. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-9-200011070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mörsdorf S, Erdlenbruch W, Taborski U, Schenk JF, Erdlenbruch K, Novotny-Reichert G, Krischek B, Wenzel E. Training of patients for self-management of oral anticoagulant therapy: standards, patient suitability, and clinical aspects. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1999;25:109–115. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-996433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss MT, Schoch PH, Sintek CD. Efficient operation of a high-volume anticoagulation clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:443–449. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki PT. A structured teaching and self-management program for patients receiving oral anticoagulation: a randomized controlled trial. Working Group for the Study of Patient Self-Management of Oral Anticoagulation. JAMA. 1999;281:145–150. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone S, Holden A, Knapic N, Ansell J. Comparison between videotape and personalized patient education for anticoagulant therapy. J Fam Pract. 1989;29:55–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalley RD, Kearney E, Jakobs E. Interdisciplinary inpatient warfarin education program. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1979;36:219–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice DA, Gardiner C, Kitchen S, Mackie I, Murray ET, Machin SJ, British Society of Haematology Taskforce for Haemostasis and Thrombosis An evidence-based review and guidelines for patient self-testing and management of oral anticoagulation. Br J Haematol. 2005;131:156–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan O, Stinson JC, Feely J. Establishing a primary care based anticoagulation clinic. Ir Med J. 2003;93:45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erban S. Initiation of warfarin therapy: recommendations and clinical pearls. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 1999;7:145–148. doi: 10.1023/A:1008833520158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines ST. Patient education: A tool in the outpatient management of deep venous thrombosis. Pharmacother. 1998;18:158S–64S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu A, Chow CM, Dao D, Errett L, Keith M. Factors influencing patient knowledge of warfarin therapy after mechanical heart valve replacement. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;21:169–175. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200605000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche-Nagle G, Chambers F, Nanra J, Bouchier-Hayes D, Young S. Evaluation of patient knowledge regarding oral anticoagulants. Ir Med J. 2003;96:211–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AL, Jackson TR, Bruce S, Shapiro NL. The development and performance validation of a tool to assess patient anticoagulation knowledge. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2005;1:40–59. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadar S, Begum N, Kaur B, Sandhu S, Lip GY. Patients' understanding of anticoagulant therapy in a multiethnic population. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:175–179. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.4.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah GM, Martens KH. Coumadin knowledge deficits: do recently hospitalized patients know how to safely manage the medication? Home Healthc Nurse. 2003;21:94–100. doi: 10.1097/00004045-200302000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson FL, Racine E, Tekieli V, Williams B. Literacy, readability and cultural barriers: critical factors to consider when educating older African Americans about anticoagulation therapy. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:275–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcellona D, Contu P, Marongiu F. Patient education and oral anticoagulant therapy. Haematologica. 2002;87:1081–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman AD, Milligan PE, Banet GA, Gatchel SK, Gage BF. Establishing and running an effective telephone-based anticoagulation service. J Vasc Nurs. 2001;19:126–132. doi: 10.1067/mvn.2001.119940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyness MA. Evaluation of an educational programme for patients taking warfarin. J Adv Nurs. 1990;15:1052–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1990.tb01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin MA. Programmed instruction as a patient teaching tool: a study of myocardial infarction patients receiving warfarin. Heart Lung. 1979;8:511–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CM, Bayley EW. Evaluation of the use of programmed instruction for patients maintained on warfarin therapy. Am J Public Health. 1972;62:1135–1139. doi: 10.2105/ajph.62.8.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell JE, Buttaro ML, Thomas OV, Knowlton CH. Consensus guidelines for coordinated outpatient oral anticoagulation therapy management. Anticoagulation Guidelines Task Force. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31:604–615. doi: 10.1177/106002809703100516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyness MA. Warfarin patient education: are we neglecting the program design process? Patient Educ Couns. 1989;14:159–169. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(89)90051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadisseur AP, Kaptein AA, Breukink-Engbers WG, van der Meer FJ, Rosendaal FR. Patient self-management of oral anticoagulant care vs. management by specialized anticoagulation clinics: positive effects on quality of life. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:584–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes N, Buntinx F, Vijgen J, Arnout J, Vermylen J, Fieuws S, Van Loon H. The Belgian Improvement Study on Oral Anticoagulation Therapy: a randomized clinical trial. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2159–2165. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell J, Hirsh J, Poller L, Bussey H, Jacobson A, Hylek E. The pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126:204S–233S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.204S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]