Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO•) is an effective chain-breaking antioxidant in free radical-mediated lipid oxidation (LPO). It reacts rapidly with peroxyl radicals as a sacrificial chain-terminating antioxidant. The goal of this work was to determine the minimum threshold concentration of NO• required to inhibit Fe2+-induced cellular lipid peroxidation. Using oxygen consumption as a measure of LPO, we simultaneously measured nitric oxide and oxygen concentrations with NO•- and O2-electrodes. Ferrous iron and dioxygen were used to initiate LPO in docosahexaenoic acid-enriched HL-60 and U937 cells. Bolus addition of NO• (1.5 μM) inhibited LPO when the NO• concentration was greater than 50 nM. Similarly, using (Z)-1-[N- (3-ammoniopropyl)-N-(n-propyl)amino]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate (PAPA/NO) as a NO• donor we found that an average steady-state NO• concentration of at least 72 ± 9 nM was required to blunt LPO. As long as the concentration of NO• was above 13 ± 8 nM the inhibition was sustained. Once the concentration of NO• fell below this value, the rate of lipid oxidation accelerated as measured by the rate of oxygen consumption. Our model suggests that the continuous production of NO• that would yield a steady-state concentration of only 10 – 20 nM is capable of inhibiting Fe2+-induced LPO.

Keywords: nitric oxide, free radical, lipid peroxidation, iron, HL-60, U937, oxygen consumption, antioxidant

Introduction

There is great interest in the role of nitric oxide (oxidonitrogen(•) or NO•) in biology because it can be a signalling molecule, a toxin, a pro-oxidant, and a potential antioxidant. It is involved in signalling in vasodilatation [1, 2, 3, 4] and neurotransmission [5], a toxin in the destruction of pathogens [6, 7], and a precursor to oxidizing and nitrating species [8, 9]. However, its diverse chemistry and its biologic activity sometimes are seemingly contradictory. Nowhere is this contradiction more evident than in oxidative stress. Nitric oxide has been proposed to act as a pro-oxidant at high concentrations [10] or when it reacts with superoxide (O2•−) forming the highly reactive peroxynitrite (ONOO−) [11, 12, 13]. On the other hand, NO• can also inhibit oxidation; NO• can terminate chain reactions during lipid peroxidation, as observed in model lipid systems [14, 15], low density lipoprotein oxidation [16, 17, 18, 19] and in cells [20, 21].

Oxidative stress is a disruption in the cellular pro-oxidant antioxidant balance [22]. As the balance shifts towards pro-oxidants, potential damage in the form of oxidized DNA, proteins, and lipids can occur. Lipid peroxidation can be defined as the oxidative deterioration of lipids containing two or more carbon-carbon double bonds. The propensity of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) to undergo LPO is due to the bis-allylic methylene hydrogens, which are more susceptible to hydrogen abstraction by oxidants than fully saturated lipids [23].

Lipid peroxidation has three major components: initiation, propagation and termination [24],

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where L-H represents a lipid, generally a polyunsaturated fatty acid moiety (PUFA). Nitric oxide can serve as a chain-terminating antioxidant by reacting with chain-carrying peroxyl radicals

| (6) |

Nitric oxide can be produced both non-enzymatically and enzymatically. For example, under some physiological conditions (e.g., low pH), NO2− can be reduced to NO•, non-enzymatically [26],

| (7) |

The family of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) enzyme mediates the 5-electron oxidation of L-arginine to L-citrulline producing NO•. There are three isoforms of NOS: neuronal (NOS1), inducible (NOS2), and endothelial (NOS3). Both NOS1 and NOS3 are constitutively expressed and are estimated to produce local NO• concentrations in the nM range, while NOS2 activity is inducible and is estimated to produce concentrations of NO• in the μM range [27].

Previous work by Kelley et al. has shown that NO• can protect docosohexaenoic acid (DHA-22:6ω3)-enriched HL-60 cells against iron-induced oxidative stress [20], as determined by monitoring oxygen consumption as a measure of lipid peroxidation. These experiments demonstrated that NO• is an effective antioxidant protecting against cellular LPO; a bolus addition of NO• immediately slowed the rate of LPO; the inhibition time of LPO varied directly with the amount of NO• introduced, and when NO• reached low levels, rapid LPO resumed.

In the present work, our goal was to determine the minimum concentration of NO• required to inhibit cellular LPO. Iron(II) and dioxygen were used as an oxidative stress to initiate LPO in DHA-22:6ω3-enriched HL-60 and U937 leukemia cells [28, 29]. To determine the minimum levels of NO• needed to blunt cellular LPO, we simultaneously measured the concentration of NO• and the rate of oxygen consumption.

Materials and Methods

NO• Stock Solution

Nitric oxide gas was either obtained from a nitric oxide gas tank or prepared from an acidified sodium nitrite solution [30, 31]. Because the nitric oxide from either source can be contaminated with other oxides of nitrogen, it was purified by passing it through NaOH (4 M) and then deionized (DI) water. The purified NO• gas was then bubbled through a gas sampling bottle containing degassed DI water and stored.

Donor

The NONOate donor, (Z)-1-[N- (3-ammoniopropyl)-N-(n-propyl)amino]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate (PAPA/NO), and S-nitroso-N-acetyl-D,L-penicillamine (SNAP) were from Alexis (San Diego, CA).

NO• and O2 Electrodes

For the bolus-addition experiments, simultaneous electrochemical measurements of nitric oxide and oxygen were made using a ISO-NO Mark II NO•-measurement system (WPI, Sarasota, FL) and ISO2 oxygen system. Data from these instruments were imported to a PC using a Duo18 data recording system (WPI). The data recording system allowed for measurements at 0.2 s intervals. Both the NO• and O2 probes were standardized daily according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The response time of the nitric oxide probe response was rapid (<10 s equilibration to 1.5 μM NO• by bolus injection). For the donor experiments, the steady-state NO• concentrations produced through the degradation of the NONOate donors were also determined using an Apollo 4000 Free Radical Analyzer (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). The NO• electrode was calibrated using two different techniques. The first method used bolus additions of increasing volumes of 50 nM NaNO2 into 10 mL of reducing solution (0.1 M KI, 0.1 M H2SO4). The production of NO• via the reduction of NaNO2 is illustrated by the following equation:

The second calibration method uses the copper-catalyzed [32] release of NO• from bolus additions of a 150 μM S-nitroso-N-acetyl-D,L-penicillamine (SNAP) and 540 μM EDTA solution into a 0.1 M copper sulfate solution. SNAP decomposes to NO• and a disulfide byproduct according to the following equation:

Regardless of the calibration method used, an electrode response plot is generated. The NO• electrode generally has a linear response from 25–2000 nM where the slope of the line provides the current to concentration ratio for the electrode. At a range of 25–400 nM the linear response of the electrode normally provides an r2-value of 0.99. If the r-value begins to deviate, the electrodes are inspected for tears in the membrane, which affects the response. The electrochemical signal from the O2 electrode was calibrated using the signal difference from aerated water (approximately 250 μM) and an argon-purged aqueous solution (0 μM).

Cell Culture

Human leukemia cells (HL-60, U937) were acquired from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were grown in medium consisting of RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) and 10% fetal bovine serum (10% FBS-RPMI) supplemented with L-glutamine (2 mM) at 37°C, 5% CO2/95% air. Experiments were done in exponential growth phase. To alter the fatty acid profile of cells they were grown in 10% FBS-RPMI medium supplemented with 32 μM docosahexaenoic acid, (DHA: 22:6ω3) for 48 h [23].

Lipid Peroxidation Measurements

HL-60

HL-60 cells were washed twice, first in RPMI-1640 medium then in PBS by centrifugation (300 g). Upon re-suspension, cell density was adjusted (3 × 106 cells/mL) for the LPO experiments [33, 34]. Following baseline measurements of [O2] and [NO•] in the ISO-NO chamber, FeSO4 (10 μM final concentration; 2 μL of 10 mM stock at pH 2.0) was introduced to induce lipid peroxidation. The pH of the cell suspension, 6.5, was not significantly affected by the injection. The pH of 6.5 was chosen to avoid problems of iron solubility and consequently the reactivity of ferrous iron [35]. All reactions were performed at 25°C with magnetic stirring.

U937

Cellular LPO is measured via the rate of consumption of oxygen using an oxygen electrode system [20, 21]; the World Precision Instruments (Sarasota, FL) system allowed simultaneous determination of [O2] and [NO•]. We suspended approximately 3.3 × 106 DHA-22:6ω3-enriched U937 cells per mL in chelated 10 mM sodium chloride solution (NaCl) containing 9000 mg L−1 of NaCl at pH ≅ 6.5 with a 1 mL NO• chamber. The chamber was then sealed and the electrodes inserted. We used NO• donors to measure the antioxidant effect of NO• in iron-induced lipid peroxidation. The pH of both the Fe2+ solution and the donor was adjusted from their respective storage solutions to pH 6.5 prior to addition to the system.

Results

To determine the level of nitric oxide needed to blunt lipid peroxidation we used a leukemia cell culture model system in which the cells were enriched with the unsaturated fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA-22:6ω3) [23]. This enrichment results in the cells being more oxidizable; providing an ideal system to study cellular lipid oxidation. We used two complementary approaches to identify the minimum level of [NO•] needed to blunt lipid peroxidation. In each approach cellular lipid peroxidation was initiated by the introduction of Fe2+. In the first approach we introduced a bolus of NO• (1.5 μM) followed immediately by 10 μM Fe2+ into suspensions of DHA-22:6ω3-enriched HL-60 cells. By simultaneously measuring [NO•] and [O2], we could correlate changes in the rate of peroxidation, as measured by the rate of oxygen uptake, and the level of NO•. This allowed us to estimate the level of NO• required to blunt cellular lipid peroxidation. When NO• was introduced into PBS, PBS + Fe2+, or PBS + cells it disappeared at a rate consistent with its known reaction with dioxygen,

The rate of this process is governed by a rare, third-order rate constant where k = 2.4 × 106 M−2 s−1 at 37°C [36]; oxygen concentration enters the rate equation as a first-order term, nitric oxide concentration as a second-order term. Analysis of the electrode data for the disappearance of NO• vs time showed that neither the presence of cells nor ferrous iron produced a major change in the rate of disappearance of NO•, Table 1. Analysis of the data showed that under the conditions of our experiments, loss of nitric oxide was second-order in [NO•] with a third order rate constant very similar to the published rate constant for the reaction of NO• with O2 in room temperature aqueous solution. However, upon the initiation of lipid peroxidation by the introduction of iron to the cellular peroxidation system, the rate of loss of NO• accelerated. It no longer obeyed the kinetics of the reaction with dioxygen. Figure 1 depicts representative experiments where NO• and Fe2+ were injected in rapid succession. Consistent with previous observations [34,37], the introduction of ferrous iron results in a rapid initiation of cellular lipid oxidation as seen by uptake of oxygen. As observed in model systems and LDL oxidation [14, 16] as well as cellular systems [20, 21], when a bolus of NO• (1.5 μM) was introduced, this rapid uptake of oxygen was delayed until the concentration of NO• becomes very low, and then the rate of oxygen uptake accelerates.

Table 1.

Nitric oxide decay in non-peroxidizing systems

| Conditiona | Rate Order for NO• b | |

|---|---|---|

| Aqueous | 2 | 2.1d |

| PBS | 2 | 2.8 ± 0.6 |

| PBS + Fe2+ e | 2 | 3.4 ± 0.3 |

| HL-60 cells | 2 | 3.4 ± 0.1 |

Experiments were done in air-saturated aqueous solutions with initial concentrations of NO• of approximately 1.6 μM.

The rate order was calculated by plotting log(−d[NO•]/dt) vs. log[NO•]

The rate constant was calculated from the slope of 1/[NO•] vs. t under the assumption −d[NO•]/dt = 4 k [O2] [NO•]2.

From [44].

Fe2+ added was 10 μM, as in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Exogenous nitric oxide delays lipid peroxidation in HL-60 cells.

Nitric oxide (

1600 nM delivered as a single bolus addition) and iron(II) (10 μM) were added sequentially. When NO• is present, the concentration of oxygen (

1600 nM delivered as a single bolus addition) and iron(II) (10 μM) were added sequentially. When NO• is present, the concentration of oxygen (

) remains near baseline levels for nearly 200 s after introduction of iron(II) (*). After NO• is sufficiently depleted, the rate of oxygen consumption increases dramatically. In the absence of NO•, oxygen (

) remains near baseline levels for nearly 200 s after introduction of iron(II) (*). After NO• is sufficiently depleted, the rate of oxygen consumption increases dramatically. In the absence of NO•, oxygen (

) consumption accelerated immediately upon introduction of iron(II).

) consumption accelerated immediately upon introduction of iron(II).

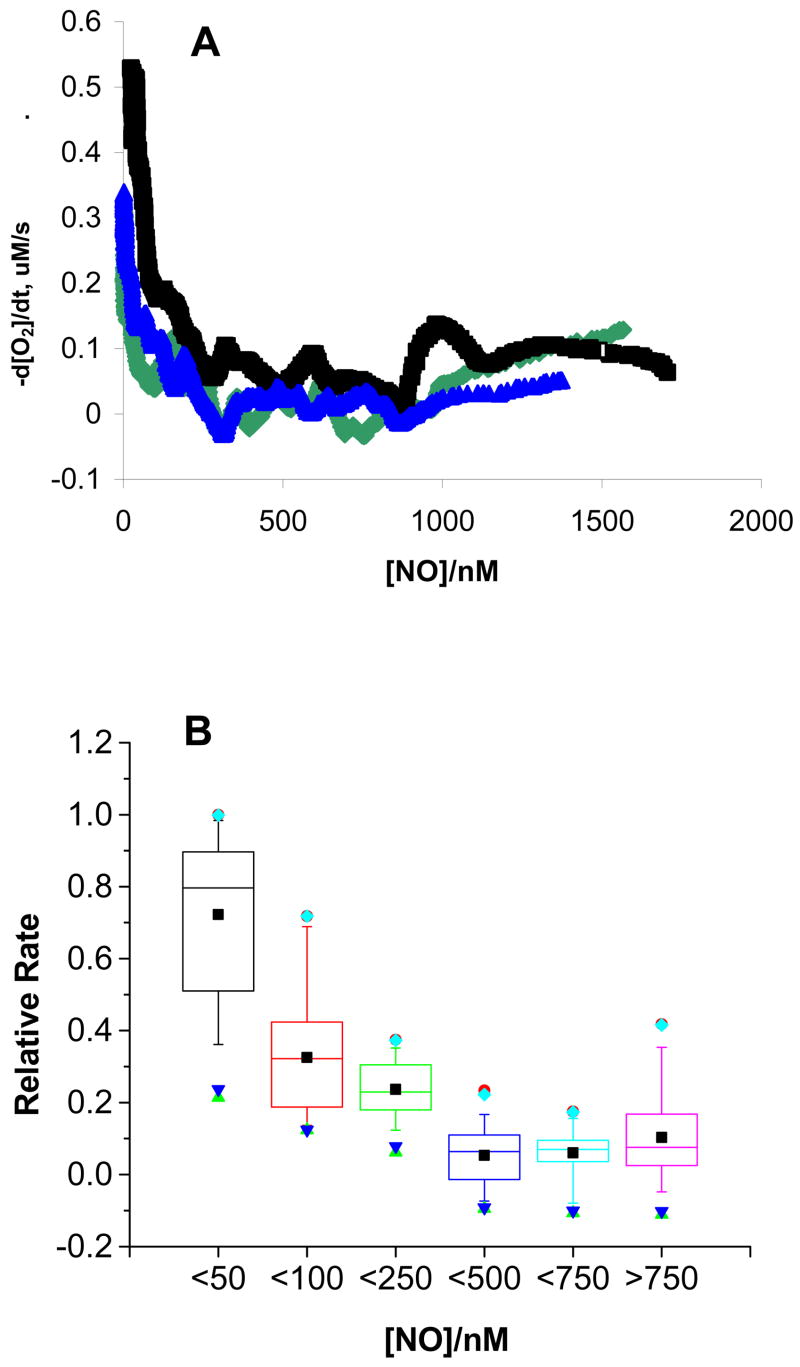

To arrive at an estimate of the concentration of NO• below which rapid oxygen uptake ensued, we plotted the data of Figure 1 as rate of peroxidation (−d[O2]/dt) vs [NO•] (rate-inhibitor plot) for relevant time points, Figure 2. Using this approach, we determined the concentration of NO• at which the rate of cellular lipid peroxidation accelerates. At higher concentrations of NO•, the rate of peroxidation, as seen by the loss of O2, was generally less than 0.1 μM s−1, Figure 2A. However, when [NO•] decreased to less than ≈250 nM, a notable increase in the reaction rate occurred and when [NO•] decreased to ≈50 nM another abrupt increase in the rate of lipid peroxidation occurred. If we define [NO•]Inh(1/2) as the concentration of nitric oxide required to limit the rate of lipid peroxidation to ½ the maximal rate in any single experiment, we have estimated that [NO•]Inh(1/2) = 40 ± 20 nM (n=3), a value consistent with the proposed concentration of NO• in many tissues [38, 39, 40, 41]. As an additional way to view the results, we grouped sets of similar rates, as observed in rate-inhibitor plots from these experiments, into bins, Figure 2B. We found that the peroxidation rate is substantially higher when [NO•] < 50 nM. These results suggest that only low nanomolar levels of nitric oxide are needed to serve as an effective lipid antioxidant.

Figure 2. The rate of oxygen consumption increases as [NO•] falls below a minimum level.

A. The rate of oxygen consumption, −d[O2]/dt, was calculated over 20-second intervals as NO• is consumed. As the concentration of NO• becomes limiting, the rate of lipid peroxidation increases. At approximately 50 – 100 nM NO•, a sharp increase in the rate of oxygen consumption occurs. Shown are results from three independent experiments.

B. Lipid Peroxidation accelerates under limiting [NO•]. The relative peroxidation rate was calculated by dividing the peroxidation rate at a given time by the maximal rate. Next, data points were divided into bins by [NO•]. At [NO•] < 50 nM, the rate of peroxidation is significantly increased, consistent with a role for nitric oxide in inhibiting lipid peroxidation kinetics. The results are from the analysis of three independent experiments.

The experiments above using bolus addition of stock solutions of NO• produced quite high, short-lived initial levels of NO•. The experiments indicate that relatively low levels of NO•, ≈50 nM, are required to inhibit cellular LPO. High levels of NO• associated with the bolus addition would not be common in vivo, rather a much lower steady-state level with minor modulation would normally be expected. To simulate this situation in our in vitro model we employed a nitric oxide donor (PAPA/NO). Our goal was to use a concentration of donor that would produce a quite low, quasi-steady-state level of NO• and thereby avoid potential artifacts due to high transient levels of NO•. The half-life of nitric oxide donors varies considerably and is in general dependent on temperature and pH [42]. Under our experimental conditions the half-life of PAPA/NO is ≈20 min, data not shown. In the experiments using PAPA/NO as a continuous source of NO•, we used DHA-enriched U937 cells, a cell line very similar to HL-60 cells; we chose these cells because the myeloperoxidase of HL-60 could accelerate the oxidation of NO• [43], although control experiments indicated this not to be a problem, data not shown.

Two representative experiments, using PAPA/NO as a NO• donor, are presented in Figure 3 (data for all experiments are summarized in Table 2); panel A shows an experiment where the maximum level of NO• reached only 20 nM, while in panel B the maximum level of NO• was 65 nM. The 20 nM system failed to protect the U937 cells against the Fe2+-induced lipid peroxidation while the 65 nM protected the cells for over 900 seconds. These lipid peroxidation experiments were repeated with various NO• concentrations. Using the experimental data from the lowest NO• concentration that provided protection, an average for the minimum level of NO• required for protection was 72 ± 9 nM; the average duration of protection was 11 ± 4 minutes; the NO•-concentration when lipid peroxidation accelerates was 13 ± 8 nM. In this model system, we observed two distinct LPO transitions as [NO•] decreased. The introduction of Fe2+ initiated a burst of LPO and a high level (≥ 75 nM) was required to contain this torrent of oxidation. However, once the [NO•] fell below ≈15 nM the antioxidant action of NO• was not sufficient and LPO accelerated.

Figure 3. A. [NO•]ss <50 nM does not inhibit Fe2+-induced LPO.

A representitive experiment using 0.38 μM PAPA/NO given initially (blue arrow) followed by 20 μM Fe2+ (red arrow) in 0.9% NaCl (pH 6.5) with DHA-22:6ω3-enriched U937 cells (3.3 × 106 mL−1). The initial rate of oxygen consumption was 1.5 μM per minute and increased to 3.7 μM per minute.

B. [NO•]ss >50 nM inhibited LPO. A representitive experiment using 0.46 μM of PAPA/NO given initially (blue arrow) followed by 20 μM Fe2+ (red arrow) in 0.9% NaCl (pH 6.5) with DHA-22:6ω3-enriched U937 cells (3.3 ± 106 mL−1). Inhibition of LPO was sustained for 10. 3 min with a rate of oxygen consumption of 1.6 μM per minute, which increased to 5.3 μM per minute when [NO•] dropped to <5 nM.

Table 2.

Nitric oxide concentration and oxygen consumption during lipid peroxidation in DHA-22:6ω3-enriched U937 cells.

| [NO•]ssa nM | Initial bd[O2]/dt μM/min | Final cd[O2]/dt μM/min | Δ([O2]/dt) d μM/min | Inhibitione min | [NO•] at Accelerationf nM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | −1.5 | −3.7 | 2.2 | 0 | --- |

| 50 | −2.3 | −10.8 | 8.5 | 0 | --- |

| 65 | −0.05 | −3.8 | 3.7 | 16.1 | 20 |

| 68 | −1.6 | −5.3 | 3.7 | 10.3 | 5 |

| 82 | −0.8 | −1.8 | 1.0 | 7.6 | 15 |

| 164 | −0.2 | −4.7 | 4.4 | 13.5 | 4 |

| 170 | −0.3 | −3.5 | 3.3 | 4.8 | 42 |

| 210 | −0.4 | −0.9 | 0.5 | 10.5 | 18 |

| 401 | −2.2 | −10.2 | 8.0 | 4.6 | 40 |

the quasi steady-state NO• concentration when Fe2+ was added; this table shows an example set of experiments;

the initial rate of O2 consumption prior to the addition of 20 μM Fe2+;

the final rate of O2 consumption after the addition of 20 μM Fe2+;

the change in the rate of O2 consumption between the final and initial rates;

the time of inhibition from the point of the Fe2+ addition to the point of increased O2 consumption;

the NO• concentration when the rate of O2 consumption accelerates.

Discussion

Nitric oxide has a rich chemistry that includes its rapid reaction with peroxyl radicals, rxn 6. This chain-termination reaction has a result similar to that of typical donor antioxidants such as vitamin E in that the chain carrying peroxyl radical (LOO•) is removed. Thus, if the covalent product, LOON=O, is not very reactive, then NO• will serve as a chain-breaking antioxidant. The discovery that NO• can be an antioxidant in LDL oxidation [16] has generated interest in the importance and mechanism of its antioxidant action. In this work we have used in vitro cell models to estimate the minimum levels of NO• needed to inhibit Fe2+-O2-mediated lipid oxidation.

We have observed that quite low levels of NO• are required to suppress LPO. When a bolus of NO• (≈1.5 μM) was introduced to rapidly peroxidizing cells, lipid peroxidation was blunted; at least 50 nM NO• was needed to maintain a low rate of LPO, preventing rapid LPO. Interestingly when a nitric oxide donor was used to generate low steady-state levels of NO•, a lower level of NO• (> ≈15 nM) was required. However, the PAPA/NO-donor experiments reveal two phases for the antioxidant action of NO•. As observed here and in our previous work [20, 21, 23, 28], the introduction of Fe2+ (20 μM) initiates a burst of cellular lipid peroxidation; to meet this burst [NO•] must be >75 nM. If the [NO•] is less than this, then cellular LPO cannot be contained. If the burst of peroxidation is quenched, then a much lower [NO•] is required to maintain a low rate of cellular lipid peroxidation, ≈15 nM in our experimental system. Once [NO•] falls below this level, lipid peroxidation accelerates. The experiments that used a bolus addition of NO•, with initial concentrations of ≈1.5 μM also showed that only ≈50 nM of NO• was required to keep lipid oxidation processes in check. These somewhat different threshold levels of NO• can be understood by examining the rate of lipid peroxidation once it accelerates. In the bolus experiments, the rate of oxygen uptake is much greater than in the donor experiments, once acceleration occurs. This is consistent with a greater oxidative stress, i.e. greater rate of initiation in the bolus experiments, thus a higher level of NO• is required. These experiments demonstrate that only very low nanomolar levels of NO• are required to blunt cellular lipid oxidation. Ambient levels of NO• in vivo are estimated to be approximately these concentrations; in vivo concentrations would be higher during signalling events or during particular pathologies. These results suggest that NO• will be an effective antioxidant in vivo because only very low levels are required.

Footnotes

This investigation was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants CA-84462, and CA-66081.

References

- 1.Waldman SA, Murad F. Biochemical mechanisms underlying vascular smooth muscle relaxation: the guanylate cyclase-cyclic GMP system. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1988;12(Suppl 5):S115, 118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ignarro LJ, Byrns RE, Buga GM, Wood KS. Endothelium dependent modulation of cGMP levels and intrinsic smooth muscle tone in isolated bovine intrapulmonary artery and vein. Circ Res. 1987;61:866–879. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen GA, Hobbs AJ, Fitch RM, Zinner MJ, Chaudhuri G, Ignarro LJ. Nitric oxide regulates endothelium-dependent vasodilator responses in rabbit hindquarters vascular bed in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H133–139. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.1.H133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moncada S, Higgs A. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bredt DS, Hwang PM, Snyder SH. Cloned and expressed nitric oxide synthase structurally resembles cytochrome P450 reductase. Nature. 1990;347:768–770. doi: 10.1038/351714a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moncada S, Higgs A. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ischiropoulos H, Zhu L, Beckman JS. Peroxynitrite formation from macrophage-derived nitric oxide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298:446–451. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90433-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, Marshall PA, Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radi R. Nitric oxide, oxidants, and protein tyrosine nitration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(12):4003–4008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307446101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joshi M, Ponthier J, Lancaster J. Cellular antioxidant and proxidant actions of nitric oxide. Free Rad Biol Med. 1999;27:1357–1366. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, Marshall PA, Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ischiropoulos H, Zhu L, Beckman JS. Peroxynitrite formation from macrophage-derived nitric oxide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298:446–451. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90433-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radi R, Peluffo G, Alvarez MN, Naviliat M, Cayota A. Unraveling peroxynitrite formation in biological systems. Free Rad Biol Med. 2001;30(5):463–488. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Donnell VB, Chumley PH, Hogg N, Bloodsworth A, Darley-Usmar VM, Freeman BA. Nitric oxide inhibition of lipid peroxidation: Kinetics of reaction with lipid peroxyl radicals and comparison with α-tocopherol. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15216–15223. doi: 10.1021/bi971891z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubbo H, Radi R, Trujillo M, Teller R, Kalyanaraman B, Barnes Kirk M, Freeman B. Nitric oxide regulation of superoxide and peroxynitrite-dependent lipid peroxidation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26066–26075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogg N, Kalyanaraman B, Joseph J, Struck A, Parthasarathy S. Inhibiton of low-density lipoprotein oxidation by nitric oxide, potential role in atherogenisis. FEBS Lett. 1993;334:170–174. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81706-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubbo H, Parthasarathy S, Barnes S, Kirk M, Kalyanaraman B, Freeman BA. Nitric oxide inhibition of lipoxygenase-dependent liposome and low- density lipoprotein oxidation: termination of radical chain propagation reactions and formation of nitrogen-containing oxidized lipid derivatives. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;324:15–25. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.9935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamanaka N, Oda O, Nagao S. Nitric oxide released from zwitterionic polyamine/NO adducts inhibits Cu2+-induced low density lipoprotein oxidation. FEBS Lett. 1996;398:53–56. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogg N, Kalyanaraman B. Review: nitric oxide and lipid peroxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1411:378–384. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley EE, Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Burns CP. Nitric oxide inhibits iron-induced lipid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;370:97–104. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schafer FQ, Wang H, Kelley E, Cueno K, Martin S, Buettner GR. Comparing β-carotene, vitamin E and nitric oxide as membrane antioxidants. Biol Chem. 2002;383:671–681. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sies H. Oxidative Stress: from basic research to clinical application. Ameri J Med. 1991;91(3C):31S–38S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Burns CP. Free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation in cells: Oxidizability is a function of cell lipid bis-allylic hydrogen content. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4449–4453. doi: 10.1021/bi00181a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardner HW. Oxygen radical chemistry of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;7:65–86. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padmaja S, Huie RE. The reaction of nitric oxide with organic peroxyl radicals. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;195:539–544. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlsson S, Wiklund NP, Engstrand L, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JON. Effects of pH, nitrite, and ascorbic acid on nonenzymatic nitric oxide generation and bacterial growth in urine. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5:580–586. doi: 10.1006/niox.2001.0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moncada S, Palmer R, Higgs E. Nitric oxide – physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmo Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qian SY, Buettner GR. Iron and dioxygen chemistry is an important route to initiation of biological free radical oxidations: An electron paramagnetic resonance spin trapping study. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:1447–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schafer FQ, Qian SY, Buettner GR. Iron and free radical oxidations in cell membranes. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 2000;46:657–662. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brauer G, editor. Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venkataraman S, Martin SM, Schafer FQ, Buettner GR. Detailed methods for quantification of nitric oxide aqueous solutions using either and an oxygen monitor or EPR. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:580–585. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dicks AP, Swift HR, Williams DLH, Butler AR, Al-Sa’doni HH, Cox BG. Identification of Cu+ as the effective reagent in nitric oxide formation from S-nitrosothiols (RSNO) J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1996;2:481–487. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burns CP, Petersen ES, North JA, Ingraham LM. Effect of docosahexaenoic acid on rate of differentiation of HL-60 human leukemia. Cancer Research. 2000;49(12):3252–3258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Burns CP. Vitamin E slows the rate of free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation in cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;334:261–267. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schafer FQ, Buettner GR. Acidic pH amplifies iron-mediated lipid peroxidation in cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1175–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ford PC, Wink DA, Stanbury DM. Autoxidation kinetics of aqueous nitric oxide. FEBS Lett. 1993;326:1–3. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81748-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelley EE, Buettner GR, Burns CP. Relative α-tocopherol deficiency in cultured tumor cells: Free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation, lipid oxidizability, and cellular polyunsaturated fatty acid content. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;319:102–109. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsoukias NM, George SC. Impact of volume-dependent alveolar diffusing capacity on exhaled nitric oxide concentration. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2001;29(9):731–739. doi: 10.1114/1.1397786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poderoso JJ, Carreras MC, Schopfer F, Lisdero CL, Riobo NA, Giulivi C, Boveris AD, Boveris A, Cadenas E. The reaction of nitric oxide with ubiquinol: kinetic properties and biological significance. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(7–8):925–935. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joshi MS, Lancaster JR, Jr, Liu X, Ferguson TB., Jr In situ measurement of nitric oxide production in cardiac isografts and rejecting allografts by an electrochemical method. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5(6):561–565. doi: 10.1006/niox.2001.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simonsen U, Wadsworth RM, Buus NH, Mulvany MJ. In vitro simultaneous measurements of relaxation and nitric oxide concentration in rat superior mesenteric artery. Journal of Physiology. 1999;516(Pt 1):271–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.271aa.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas DD, Miranda KM, Espey MG, Citrin D, Jourd’heuil D, Paolocci N, Hewett SJ, Colton CA, Grisham MB, Feelisch M, Wink DA. Guide for the use of nitric oxide (NO) donors as probes of the chemistry of NO and related redox species in biological systems. Methods in Enzymology. 2002;359:84–105. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)59174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eiserich JP, Baldus S, Brennan ML, Ma WX, Zhang CX, Tousson A, Castro L, Lusis AJ, Nauseef WM, White CR, Freeman BA. Myeloperoxidase, a leukocyte-derived vascular NO oxidase. Science. 2002;296(5577):2391–2394. doi: 10.1126/science.1106830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Awad HH, Stanbury DM. Autoxidation of NO in aqueous-solution. Int J Chem Kinetics. 1993;25:375–381. [Google Scholar]