Abstract

Fluoroquinolone-resistant Burkholderia cepacia mutants were selected on ciprofloxacin. The rate of mutation in gyrA was estimated to be 9.6 × 10−11 mutations per division. Mutations in gyrA conferred 12- to 64-fold increases in MIC, and an additional parC mutation conferred a large increase in MIC (>256-fold). Growth rate, biofilm formation, and survival in water and during drying were not impaired in strains containing single gyrA mutations. Double mutants were impaired only in growth rate (0.85, relative to the susceptible parent).

Exposure to fluoroquinolones increases mutation rates (9, 12, 20, 26) to various degrees (23). The main mechanism of resistance in gram-negative bacteria develops via stepwise accumulation of mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of topoisomerase genes (4, 7, 8, 13).

Opportunistic pathogens of the Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC) consist of genomovars that are important in cystic fibrosis patients (14, 17). Genomovars are species which are phylogenetically distinguishable but phenotypically indistinguishable from each other. Here, BCC refers to the complex, while B. cepacia refers to genomovar I. BCC bacteria can survive in respiratory droplets on surfaces (6) and are resistant to many antibacterial agents.

Resistance to drying allows maintenance on environmental surfaces (24) and transmission between hosts. Transmission between colonized patients has been documented (18).

The objective of this work was to investigate the effects of fluoroquinolone resistance mutations on growth rate, biofilm formation, and environmental survival.

B. cepacia 10661 (National Collection of Type Cultures, HPA, London, United Kingdom) and mutants derived from this strain were used. The MICs of parent and mutant strains were determined by the ciprofloxacin Etest (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden).

The ciprofloxacin MIC of B. cepacia 10661 was 1 μg/ml. Putative resistant mutants were selected at 2×, 4×, and 6× MIC in three separate experiments. Estimation of the mutation rate was performed using ciprofloxacin at 6× MIC. Characterized first-step mutants were used to obtain second-step mutants by selecting first-step mutations on media containing twice the MIC of the first-step mutants. The numbers of viable cells, from three aliquots (approximately 10%), were determined using the method of Miles and Misra in order to determine total cell numbers (3, 11). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h, and the proportion of cultures with mutant colonies were recorded. The mutation rate (μ) was determined using the p0 method (10, 19, 21).

Approximately 102 exponentially growing cells were independently inoculated into 28 tubes, each containing 3 ml of Mueller-Hinton broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom), and incubated at 37°C for 22 h on an orbital shaker (250 rpm; Barloworld Scientific, Rochester, NY). The cells were harvested by centrifugation (2,000 × g, 10 min), the supernatant was removed with a pipette, and the pellet was resuspended in 400 μl of Mueller-Hinton broth and then plated onto Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) containing ciprofloxacin.

The mutants were characterized by sequencing the QRDRs of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE by using the primers listed in Table 1. Standard PCR conditions were employed. Sequencing was performed by the dideoxy method as previously described (15).

TABLE 1.

Primers used to amplify the QRDRs of the topoisomerase genes of B. cepacia

| Gene | Primer positionsa | Sequence (5′-3′) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| gyrA | 62-81 | 5′ ATCTCGATTACGCGATGAGC | 449 |

| 493-511 | 5′ GCCGTTGATCAGCAGGTT | ||

| gyrB | 1127-1146 | 5′ GAGGAAGTTGTGGCGAAGG | 400 |

| 1502-1520 | 5′ AGTCTTCCTTGCCGATGC | ||

| parC | 98-118 | 5′ ATTGGTCAGGGTCGTGAAGA | 229 |

| 295-315 | 5′ GTAGCGCAGCGAGAAATCCT | ||

| parE | 1178-1198 | 5′ CAGGGCAAGGTAGTCGAAAA | 380 |

| 1557-1577 | 5′ GTGAGCAGCAAGGTCTGGAT |

B. cenocepacia numbering.

No mutations (0/45) were found in the QRDRs of the topoisomerase genes of B. cepacia selected at 2× MIC. The MIC of these nontopoisomerase mutants was 4 to 5 μg/ml. At 4× MIC, an Asp87Asn mutation, conferring a 16-fold increase in MIC, was found in colonies from one plate (2/55). All other mutants (53/55) selected at this concentration contained no mutations in the QRDRs (MICs between 4 and 5 μg/ml). All first-step mutants selected at 6× MIC (50/50) contained a Thr83Ile mutation in gyrA and had an MIC of 64 μg/ml. Mutations, MIC, and selection step information are shown in Table 2. Mutation rates for second-step mutations were higher than those for the first-step mutations.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of fluoroquinolone-resistant B. cepacia mutants selected in vitroa

| Strain | Mutation rate (mutation/division) | MIC (μg/μl) | Selection step | Sequence found in QRDRs of:

|

Generation time [min (95% confidence interval)] | P value | Relative fitness (±SEM)b | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gyrA | gyrB | parC | parE | ||||||||

| WT | 1 | WT | WT | WT | WT | 38.0 (37.06-38.94) | |||||

| F1 mutant | 9.6 × 10−11 | 12 | 1st | Asp87Asn | WT | WT | WT | 37.0 (36.77-37.23) | 0.331 | 1.01 ± 0.01 | 0.831 |

| F2 mutant | 9.6 × 10−11 | 64 | 1st | Thr83Ile | WT | WT | WT | 37.1 (36.9-37.3) | 0.377 | 1.01 ± 0.152 | 0.868 |

| F3 mutant | 1.1 × 10−10 | >256 | 2nd | Asp87Asn | WT | Ser80Leu | WT | 43.0 (41.85-44.15) | 0.004 | 0.80 ± 0.12 | 0.003 |

| F4 mutant | 6.8 × 10−10 | >256 | 2nd | Thr83Ile | WT | Ser80Leu | WT | 45.7 (44.2-47.2) | 0.001 | 0.78 ± 0.18 | 0.002 |

Strain F1 was isolated on 2 μg/ml ciprofloxacin (2× MIC); F2 was isolated on 6 μg/ml (6× MIC), F3 was isolated on 24 μg/ml ciprofloxacin by the use of F1 as the starting point; F4 was isolated on 128 μg/ml ciprofloxacin by the use of F2 as the starting point. The statistical significance of generation time differences is shown by a P value. WT, wild type.

Competition assays were used to measure the fitness of the fluoroquinolone mutants relative to that of the susceptible parent.

To detect efflux activity, the ciprofloxacin MIC of the fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants was determined in the absence and presence of reserpine (25 μg/ml) in Mueller-Hinton agar (2). The MICs of all mutants that did not contain gyrA mutations, selected at either 2× MIC (45 mutants tested) or 4× MIC (55 mutants tested), decreased fivefold in the presence of reserpine to the level of the wild type. The MICs of mutants containing topoisomerase mutations did not decrease.

The quantification of biofilm growth was achieved by the spectrophotometric measurement of crystal violet binding by following a previously published method (5). Mutation in gyrA and parC did not affect biofilm formation in B. cepacia. All fitness assays were carried out with one mutation of each type (data not shown).

We modified the method of Youmans and Youmans (25) to determine time to positivity as an indicator of the growth rate. The Bactec 9240 continuous blood culture system with standard aerobic medium (Plus Aerobic/F) was used. Aliquots of 100 μl of the diluted exponential culture (1/10 and 1/1,000) were removed using a 0.5-ml syringe and a needle and were aseptically inoculated into duplicate culture vials. The length of time to detection (time to positivity) was measured for all strains. Gram staining and a purity plate assay were performed to confirm the absence of contaminants.

The growth rate constant, k, was determined using equation 1 (where A is the largest inoculum employed, B is the smallest inoculum, and t is the difference in time to positivity in hours). The generation time (G) was determined using equation 2.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

This experiment was repeated in triplicate. The growth rates of the double mutants relative to those of the parent were 0.88 and 0.83 for mutant strains F3 and F4, respectively, as shown in Table 2.

Competition assays were used to measure the fitness of the fluoroquinolone mutants compared to that of the susceptible parent by the use of a modified version of our previously published method (3, 11). The optical densities of the wild-type and mutant isolates were adjusted to the same value (1.0 optical density unit). Then, 250 μl of each culture was inoculated into 15 ml of LB broth in the absence of antibiotics. This mixed culture was incubated for 10 h (200 rpm). The relative fitness of each strain was calculated from the ratio of the number of generations grown by the resistant strains to the number grown by the susceptible strains. Five independent pairwise cultures were performed for each mutant. The relative growth rates of mutant strains F3 and F4 were 0.80 and 0.78, respectively. The differences in relative growth rates of the strains with the single gyrA mutations found during paired competition assays were not significant, as determined by Student's t test. However, these assays cannot measure differences of >1%.

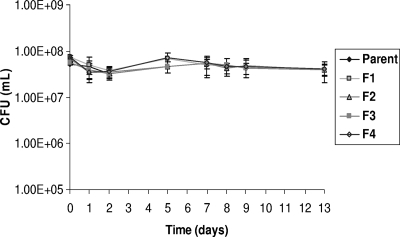

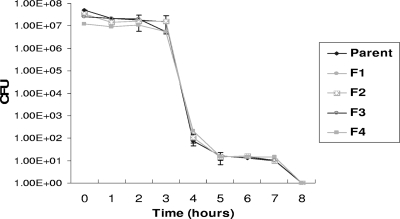

Survival in water and survival during drying were assessed using the method employed by Sánchez et al. (22). No significant differences in environmental survival were found between the mutants and the susceptible parent, as shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2.

FIG. 1.

Effect of topoisomerase mutations on the survival of B. cepacia in water. Survival of B. cepacia in water was not affected by mutation in gyrase subunit A or topoisomerase IV. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. Differences in survival are not significant.

FIG. 2.

Effect of topoisomerase mutations on the survival of B. cepacia on dry surfaces. Survival of B. cepacia in water was not affected by mutation in gyrase subunit A or topoisomerase IV. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. Error bars are not shown if obscured by the symbol. Differences in survival are not significant.

Selection at lower concentrations of fluoroquinolone resulted in mutants in which resistance was apparently due to an altered expression of an efflux pump. Similarly, Zhou et al. demonstrated that low concentrations of fluoroquinolone selected nongyrase mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis (27).

At higher selection concentrations of ciprofloxacin (4× and 6× MIC), mutations in the topoisomerase genes were found. Lower-level resistance (12- to 64-fold) was caused by single mutations in gyrA. Higher-level resistance (MIC of >256 μg/ml) required mutations in both gyrA and parC. The same second-step mutation occurred irrespective of the starting point.

Single-step fluoroquinolone resistance in gyrA occurs at low or no cost to B. cepacia, and this has been observed for other bacteria (11, 1, 16). These mutants may, therefore, remain in the bacterial population in the absence of an antibiotic selective pressure.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tyrone Pitt (HPA, London, United Kingdom) for advice and for kindly providing reference strains.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bagel, S., V. Hullen, B. Wiedemann, and P. Heisig. 1999. Impact of gyrA and parC mutations on quinolone resistance, doubling time, and supercoiling degree of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:868-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyer, R., E. Pestova, J. J. Millichap, V. Stosor, G. A. Noskin, and L. R. Peterson. 2000. A convenient assay for estimating the possible involvement of efflux of fluoroquinolones by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for diminished moxifloxacin, sparfloxacin, and trovafloxacin efflux. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:798-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billington, O. J., T. D. McHugh, and S. H. Gillespie. 1999. Physiological cost of rifampin resistance induced in vitro in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1866-1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, F. J., and H. J. Lo. 2003. Molecular mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 36:1-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conway, B.-A. D., V. Venu, and D. P. Speert. 2002. Biofilm formation and acyl homoserine lactone production in the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Bacteriol. 184:5678-5685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drabick, J. A., E. J. Gracely, G. J. Heidecker, and J. J. LiPuma. 1996. Survival of Burkholderia cepacia on environmental surfaces. J. Hosp. Infect. 32:267-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drlica, K., and M. Malik. 2003. Fluoroquinolones: action and resistance. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 3:249-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drlica, K., and X. Zhou. 1997. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:377-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillespie, S. H., S. Basu, A. L. Dickens, D. M. O'Sullivan, and T. D. McHugh. 2005. Effect of subinhibitory concentrations of ciprofloxacin on Mycobacterium fortuitum mutation rates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:344-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillespie, S. H., L. L. Voelker, J. E. Ambler, C. Traini, and A. Dickens. 2003. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: evidence that gyrA mutations arise at a lower rate and that mutation in gyrA or parC predisposes to further mutation. Microb. Drug Resist. 9:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillespie, S. H., L. L. Voelker, and A. Dickens. 2002. Evolutionary barriers to quinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb. Drug Resist. 8:79-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gocke, E. 1991. Mechanism of quinolone mutagenicity in bacteria. Mutat. Res. 248:135-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hooper, D. C. 2003. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance, p. 41-67. In D. C. Hooper and E. Rubenstein (ed.), Quinolone antimicrobial agents. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 14.Isles, A., I. Maclusky, M. Corey, R. Gold, C. Prober, P. Fleming, and H. Levison. 1984. Pseudomonas cepacia infection in cystic fibrosis: an emerging problem. J. Pediatr. 104:206-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins, C. 2005. Rifampicin resistance in tuberculosis outbreak, London, England. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:931-934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kugelberg, E., S. Lofmark, B. Wretlind, and D. I. Andersson. 2005. Reduction of the fitness burden of quinolone resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:22-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LiPuma, J. J. 1998. Burkholderia cepacia. Management issues and new insights. Clin. Chest Med. 19:473-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LiPuma, J. J., S. E. Dasen, D. W. Nielson, R. C. Stern, and T. L. Stull. 1990. Person-to-person transmission of Pseudomonas cepacia between patients with cystic fibrosis. Lancet 336:1094-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luria, S., and M. Delbruck. 1943. Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics 28:491-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mamber, S. W., B. Kolek, K. W. Brookshire, D. P. Bonner, and J. Fung-Tomc. 1993. Activity of quinolones in the Ames Salmonella TA102 mutagenicity test and other bacterial genotoxicity assays. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:213-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosche, W. A., and P. L. Foster. 2000. Determining mutation rates in bacterial populations. Methods 20:4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sánchez, P., J. F. Linares, B. Ruiz-Diez, E. Campanario, A. Navas, F. Baquero, and J. L. Martinez. 2002. Fitness of in vitro selected Pseudomonas aeruginosa nalB and nfxB multidrug resistant mutants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:657-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sierra, J. M., J. G. Cabeza, C. M. Ruiz, T. Montero, J. Hernandez, J. Mensa, M. Llagostera, and J. Vila. 2005. The selection of resistance to and the mutagenicity of different fluoroquinolones in Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11:750-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith, S. M., R. H. Eng, and F. T. Padberg, Jr. 1996. Survival of nosocomial pathogenic bacteria at ambient temperature. J. Med. 27:293-302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Youmans, G. P., and A. S. Youmans. 1949. A method for the determination of the rate of growth of tubercle bacilli by the use of small inocula. J. Bacteriol. 58:247-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ysern, P., B. Clerch, M. Castano, I. Gibert, J. Barbe, and M. Llagostera. 1990. Induction of SOS genes in Escherichia coli and mutagenesis in Salmonella typhimurium by fluoroquinolones. Mutagenesis 5:63-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou, J., Y. Dong, X. Zhao, S. Lee, A. Amin, S. Ramaswamy, J. Domagala, J. M. Musser, and K. Drlica. 2000. Selection of antibiotic-resistant bacterial mutants: allelic diversity among fluoroquinolone-resistant mutations. J. Infect. Dis. 182:517-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]