Abstract

Twenty-three isolates of group A streptococci (GAS) recovered from population-based invasive GAS surveillance in the United States were erythromycin resistant, inducibly clindamycin resistant, and lacked known macrolide resistance determinants. These 23 isolates, representing four different clones, contained a broad-host-range plasmid carrying the erm(T) methylase gene, which has not been detected in GAS previously.

Penicillins are the antibiotics of choice for treatment of pharyngitis caused by group A streptococci (GAS), with macrolides recommended for patients with penicillin allergy. Macrolide-resistant GAS are an increasing concern worldwide, with a correlation between increasing macrolide resistance and an increase in macrolide consumption (2, 6, 22).

In GAS, macrolide resistance is conferred by the 23S rRNA methylase genes erm(B) and erm(TR), as well as by the efflux determinant mef(A) (12, 15). The erm(B) and erm(TR) genes often confer inducible resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramin B, but also may encode constitutive resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramin B due to upstream attenuator sequence alterations. mef(A) encodes efflux pump-mediated resistance to erythromycin (and other 14- or 15-member ring macrolides), while the organism remains susceptible to clindamycin (and other lincosamides) and streptogramin B. Aquisition of macrolide resistance primarily occurs by horizontal gene transfer of erm or mef genes (4, 13), while more rarely resistance results from mutations within genes encoding ribosomal components (12). The erm(B) and erm(TR) genes often confer cross-resistance to both lincosamides and streptogramins and therefore limit the therapeutic possibilities available to clinicians for the treatment of GAS disease (12).

In this study, we identified the genetic basis of macrolide and inducible clindamycin resistance in 23 invasive GAS isolates that were negative for macrolide resistance determinants known to be disseminated among resistant GAS (5, 16, 18). These 23 isolates were collected among all invasive GAS infections reported during 1999, 2001, and 2003 (3,189 reported cases) from CDC's population-based Active Bacterial Core surveillance conducted in 10 sites throughout the United States (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/abcs/).

Susceptibility to erythromycin was determined by the broth dilution technique with a standard panel of antibiotics, including erythromycin and clindamycin. The double-disk diffusion (D) test (4, 16) confirmed erythromycin resistance and detected inducible clindamycin resistance. Mueller-Hinton agar plates supplemented with 5% sheep blood were inoculated with a suspension of GAS that met a McFarland 0.5 turbidity standard. An erythromycin disk containing 15 μg and a clindamycin disk containing 2 μg were placed 12 mm apart (edge to edge). Resistance to erythromycin with blunting of the zone of inhibition around the clindamycin disk facing the side of the erythromycin disk indicated inducible clindamycin resistance.

PCR was performed for detection of erm(A), erm(B), and erm(C) (18). Detection of erm(TR) and mef determinants employed primers designed at the Minnesota Department of Health (Table 1). PCRs for erm(TR) and mef contained 10 mM Tris HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 μM each forward and reverse primers, and 2 μl of template DNA in a total volume of 50 μl. Annealing temperatures were 55°C for erm(TR) and 56°C for mef. When PCR assays were negative for the erm and mef determinants described above, erm(T)-specific primers (Table 1) were subsequently used to detect a PCR product of 478 bp from all 23 isolates after electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels.

TABLE 1.

PCR primers used in this study for detection of macrolide resistance genes

| Gene(s) | Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| erm(TR) | TR-322U | 5′-GGGTCAGGAAAAGGACAT-3′ |

| TR619L | 5′-CCTAAAGCTCGTTGATT-3′ | |

| mef(A) and mef(E) | mef-3301U | 5′-AGGGCAAGCAGTATCATTAATCA-3′ |

| mef-3673L | 5′-CTGCAAAGACTGACTATAGCCT-3′ | |

| erm(T) | erm(T) forward | 5′-CCGCCATTGAAATAGATCCT-3′ |

| erm(T) reverse | 5′-GCTTGATAAAATTGGTTTTTGGA-3′ |

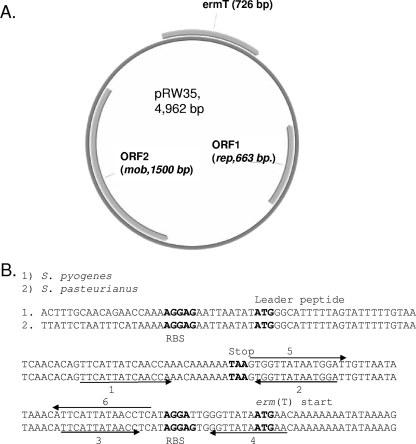

Crude bacterial DNA templates were prepared as described previously (1; www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strep/protocol_emm-type.htm). Assuming a chromosomal location for erm(T) in the 23 isolates, single-primer PCR (10) was used to amplify the sequences adjacent to erm(T) as described previously for mapping the GAS sof locus (8). All sequencing data generated from the single-primer template were reconfirmed by conventional PCR amplification with appropriate primer pairs. DNA sequences were analyzed using the Wisconsin Package, version 10.3 (Accelrys, Inc., San Diego, CA). When a high level of homology to the Lactobacillus sp. plasmid p121BS (23) was found downstream and upstream of erm(T), we subsequently used appropriate reverse and forward primers for amplification of the putative plasmid as a linear PCR fragment. Plasmid DNA was purified from Streptococcus pyogenes isolates with the Qiagen Mini-Prep kit, with a 10-min incubation in buffer P1 containing lysozyme and mutanolysin at 37°C prior to the addition of reagent P2. Sequence analysis indicated that erm(T) was situated on a 4,962-bp replicative plasmid, designated pRW35 (GenBank accession no. EU192194). The pRW35 sequence had a G+C content of 37% and three distinct open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

(A) Diagram of pRW35. Three ORFs are indicated. (B) Nearly identical attenuator and translational start regions of erm(T) from S. pyogenes and Streptococcus pasteurianus. The sequences encompassing the leader peptide-encoding sequence and erm(T) translational start are shown. Perfect and imperfect inverted repeats are indicated with arrows. Pairing of inverted repeats 5 and 6 represents the putative active conformation according to the erm(C) model (10). Pairing of inverted repeats 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 represents the putative inactive conformation in which the erm(T) ribosome binding site (RBS) and translation initiation codon are sequestered by pairing of inverted repeats 3 and 4. The RBS, translational start codons, and leader peptide translational stop codons are in bold.

One ORF exhibited near identity (≥98%) to the erythromycin resistance methylase gene erm(T) found on a transposon in Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus (20) as well as plasmid-borne erm(T) determinants from Lactobacillus reuteri (19), Lactobacillus sp. (23), and Streptococcus bovis (NCBI accession no. BAA75016). In addition to erm(T), pRW35 contains two ORFs highly similar to plasmid replication and transfer genes found in broad-host-range plasmids. ORF2 predicts a protein highly similar (>60%) to mobilization proteins from Streptococcus agalactiae, Lactococcus lactis, and Streptococcus bovis (14, 21).

An attenuator region upstream of erm(T) in pRW35 nearly identical to its counterpart in S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus was identified (Fig. 1B). This region shares features with the corresponding region upstream of the S. aureus plasmid-borne erm(C) (7) and is predicted to share the same mechanism of regulating translation of the erm(T) message (3, 7). During induction by erythromycin, sensitive ribosomes are stalled upon the upstream leader peptide favoring formation of hairpin structure 5-6 (active conformation). As the proportion of resistant ribosomes increases (originally present in relatively small numbers) to a critical level, translation of the erm(T) message greatly decreases due to a shift of the message to the inactive conformation (1-2 and 3-4 hairpins) that results in sequestration of the erm(T) translational start and ribosome binding site.

emm typing (2; www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strep/protocol_emm-type.htm) identified four unique types among the 23 erm(T)-positive isolates, including emm92 (19 isolates), emm3 (2 isolates), emm9, and emm28 (Table 2). The 19 emm92 isolates formed a distinct cluster of highly related pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns, and the two emm3 isolates displayed an additional distinct PFGE profile (data not shown). The emm9 and emm28 isolates represented two additional distinct patterns. The T types from all of the isolates and PFGE profiles from types emm92, emm3, and emm28 conformed to patterns typically associated with erythromycin-sensitive strains of the same emm types (9; unpublished data), indicating that the emergence of erm(T)-positive GAS is not associated with newly emerging clonal types.

TABLE 2.

Features of invasive GAS isolates containing erm(T)

| emm type | Yr isolated (no. of isolates) | State(s) (no. of isolates) | T pattern (no. of isolates) | PFGE profilea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| emm92 | 1999 (3), 2001 (6), 2003 (10) | California (11), Oregon (7), Connecticut (1) | T/8/25/Imp19b (17), T nontypeable (2) | 1 |

| emm3 | 2003 (2) | Oregon (2) | T3 | 2 |

| emm9 | 2001 (1) | Georgia (1) | T14 | 3 |

| emm28 | 2001 (1) | Oregon (1) | T28 | 4 |

PFGE patterns within a given profile share identity or diverge from others within the profile by no more than three bands and differ from the other profiles by more than seven bands.

This pattern includes T/8/25/Imp19, T25/Imp19, T/Imp19, and T8/25.

We examined the ability of pRW35 to transfer resistance to another streptococcal species and to another S. pyogenes strain. Plasmid pRW35 was extracted from S. pyogenes isolates and electroporated into S. agalactiae (group B streptococci) and the emm49 S. pyogenes strain NZ131 by previously described methods (11, 17). Transformants of both species selected on sheep blood agar plates containing 1 μg/ml erythromycin were subsequently screened for the presence of the erm(T) gene by PCR and tested for inducible clindamycin resistance with the D test. All transformants had identical resistance phenotypes with the 23 GAS isolates in that they were resistant to erythromycin (≥32 μg/ml) and inducibly clindamycin resistant (12 μg/ml). All transformants were positive for erm(T) and the entire circular plasmid pRW35 by PCR analysis. These results indicated that pRW35 conferred erythromycin and inducible clindamycin resistance as a replicative plasmid in the distantly related group B species and in a heterologous S. pyogenes strain.

In summary, our data indicate that plasmid pRW25 is disseminated among multiple unrelated GAS strains, including classical opacity factor-positive (types emm28, emm9, and emm92) and -negative (emm3) strains. Transformation of pRW25 into S. agalactiae and an additional GAS strain as a replicative plasmid is consistent with the hypothesis that pRW35 is capable of dissemination to a broad range of hosts. erm(T)-specific primers may be useful in subsequent PCR screens for macrolide resistance determinants among GAS.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to all of the surveillance staff and laboratories participating in CDC's ABCs surveillance and the Emerging Infections Program Network (EIP) for funding and general support of the system.

We thank members of the CDC/RDB Streptococcus Laboratory for serotyping, antibiotic susceptibility testing, and sequencing. Robyn Woodbury was supported by the FIRST Institutional Research and Academic Career Development Award (K12) through the Division of Minority Opportunities in Research at the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 January 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beall, B., R. Facklam, and T. Thompson. 1996. Sequencing emm-specific PCR products for routine and accurate typing of group A streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:953-958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergman, M., S. Huikko, M. Pihlajamaki, P. Laippala, E. Palva, P. Huovinen, H. Seppala, and Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance (FiRe Network). 2004. Effect of macrolide consumption on erythromycin resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes in Finland in 1997-2001. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1251-1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubnau, D. 1984. Translational attenuation: the regulation of bacterial resistance to the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B antibiotics. Crit. Rev. Biochem. 16:103-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giovanetti, E., A. Brenciani, M. Vecchi, A. Manzin, and P. E. Varaldo. 2005. Prophage association of mef(A) elements encoding efflux-mediated erythromycin resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:445-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giovanetti, E., M. P. Montanari, M. Mingoia, and P. E. Varaldo. 1999. Phenotypes and genotypes of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes strains in Italy and heterogeneity of inducibly resistant strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1935-1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granizo, J. J., L. Aguilar, J. Casal, R. Dal-Re, and F. Baquero. 2000. Streptococcus pyogenes resistance to erythromycin in relation to macrolide consumption in Spain (1986-1997). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horinouchi, S., and B. Weisblum. 1980. Posttranscriptional modification of mRNA conformation: mechanism that regulates erythromycin-induced resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:7079-7083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeng, A., V. Sakota, Z. Li, V. Datta, B. Beall, and V. Nizet. 2003. Molecular genetic analysis of a group A streptococcal operon encoding serum opacity factor and a novel fibronectin-binding protein, SfbX. J. Bacteriol. 185:1208-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson, D. R., E. L. Kaplan, A. VanGheem, R. R. Facklam, and B. Beall. 2006. Characterization of group A streptococci (Streptococcus pyogenes): correlation of M-protein and emm-gene type with T-protein agglutination pattern and serum opacity factor. J. Med. Microbiol. 55:157-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karlyshev, A. V., M. J. Pallen, and B. W. Wren. 2000. Single-primer PCR procedure for rapid identification of transposon insertion sites. BioTechniques 28:1078-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimoto, H., and A. Taketo. 2003. Efficient electrotransformation system and gene targeting in pyogenic streptococci. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 67:2203-2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leclercq, R. 2002. Mechanisms of resistance to macrolides and lincosamides: nature of the resistance elements and their clinical implications. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:482-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson, D. A., J. A. Sutcliffe, W. Tewodros, A. Manoharan, and D. E. Bessen. 2006. Evolution and global dissemination of macrolide-resistant group A streptococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2903-2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarz, F. V., V. Perreten, and M. Teuber. 2001. Sequence of the 50-kb conjugative multiresistance plasmid pRE25 from Enterococcus faecalis RE25. Plasmid 46:170-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seppälä, H., A. Nissinen, Q. Yu, and P. Huovinen. 1993. Three different phenotypes of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes in Finland. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 32:885-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seppälä, H., M. Skurnik, H. Soini, M. C. Roberts, and P. Huovinen. 1998. A novel erythromycin resistance methylase gene (ermTR) in Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:257-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon, D., and J. J. Ferretti. 1991. Electrotransformation of Streptococcus pyogenes with plasmid and linear DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 66:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutcliffe, J., T. Grebe, A. Tait-Kamradt, and L. Wondrack. 1996. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2562-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tannock, G. W., J. B. Luchansky, L. Miller, H. Connell, S. Thode-Andersen, A. A. Mercer, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1994. Molecular characterization of a plasmid-borne (pGT633) erythromycin resistance determinant (ermGT) from Lactobacillus reuteri 100-63. Plasmid 31:60-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai, J.-C., P.-R. Hsueh, H.-J. Chen, S.-P. Tseng, P.-Y. Chen, and L.-J. Teng. 2005. The erm(T) gene is flanked by IS1216V in inducible erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4347-4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Lelie, D., S. Bron, G. Venema, and L. Oskam. 1989. Similarity of minus origins of replication and flanking open reading frames of plasmids pUB110, pTB913 and pMV158. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:7283-7294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varaldo, P. E., E. A. Debbia, G. Nicoletti, D. Pavesio, S. Ripa, G. C. Schito, G. Temperam, et al. 1999. Nationwide survey in Italy of treatment of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis in children: influence of macrolide resistance on clinical and microbiological outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:869-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitehead, T. R., and M. A. Cotta. 2001. Sequence analyses of a broad host-range plasmid containing ermT from a tylosin-resistant Lactobacillus sp. isolated from swine feces. Curr. Microbiol. 43:17-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]