Abstract

The anticryptosporidial activity of Bobel-24 (2,4,6-triiodophenol) was studied for the first time, resulting in a reduction of the in vitro growth of Cryptosporidium of up to 99.6%. In a SCID mouse model of chronic cryptosporidiosis, significant differences (P < 0.05) in oocyst shedding were observed in animals treated with 125 mg/kg/day. These results merit further investigation of Bobel-24 as a chemotherapeutic option for cryptosporidiosis.

Cryptosporidium parvum is considered one of the top four causes of self-limiting diarrhea in humans and in several animal species (15). In immunocompromised individuals, cryptosporidial infection may become chronic and life threatening because no completely effective treatment is available (7).

The molecular mechanism involved in the initial interaction between C. parvum sporozoites and epithelial cells is still unclear. One of the mechanisms of C. parvum attachment is the interaction between galactose-N-acetylgalactosamine (Gal/GalNAc) epitopes on the epithelial apical membrane and Gal/GalNAc-specific sporozoite surface lectins (3). Invasion by and intracellular development of the parasite lead to the destruction of epithelial cells, resulting in blunting of intestinal villi, crypt hyperplasia, and cytoskeletal remodeling. In addition, there are decreased sodium absorption, epithelial chemokine production, and increased prostaglandin production (16), which are directly related to the notable inflammatory response that follows Cryptosporidium infection and characterizes its pathology (9).

To further the improvement of treatment against cryptosporidiosis, we studied the anticryptosporidial activity of Bobel-24 (2,4,6-triiodophenol). This compound is able to inhibit lectin expression (11). In addition, Bobel-24 is considered a dual inhibitor of lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase, which are involved in the resolution of inflammatory diseases (10, 13).

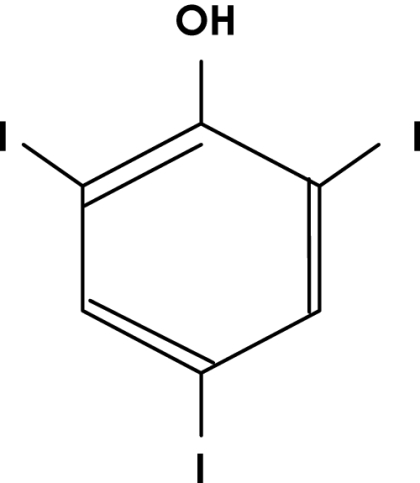

The C. parvum IOWA bovine isolate used for this study was kindly provided by M. J. Arrowood (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA). Bobel-24 is a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory compound (Fig. 1) (6, 10, 11). It is under clinical development as a potent leukotriene B4 synthesis inhibitor (17). For in vitro studies, Bobel-24, used as a pure compound (purity of 99.6%, obtained from Chemical Iberica SL, Salamanca, Spain), was first dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then diluted with phosphate-buffered saline. In an MTT cytotoxicity assay (5), viability percentages (>95%) of HCT-8 cells with Bobel-24 concentrations lower than 100 μM were observed. To study in vitro activity of Bobel-24, 8 × 105 excysted oocysts/ml (1) were inoculated in confluent HCT-8 cell monolayers as previously described (2). To assess the effect on sporozoite attachment to HCT-8 cells, we incubated sporozoite suspensions with Bobel-24 (90 μM) before use, we incubated HCT-8 cells with Bobel-24 (90 μM) before infection, and to evaluate the effect of Bobel-24 on C. parvum development in HCT-8, we incubated infected cells afterwards with 90 μM Bobel-24 for 48 h. Paromomycin (PRM) (2 mg/ml) and mucin (0.2 mg/ml) were used as treatment controls. Infected HCT-8 cells were also incubated with DMSO and with medium as controls. To study the effect of the dose on the response to Bobel-24 treatment, HCT-8 cells were inoculated with 8 × 105 oocysts/ml and then incubated with 90, 45, or 22 μM Bobel-24.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of Bobel-24.

Fixed cultures were incubated with rhodamine-labeled C3C3 monoclonal antibody to enumerate meronts and gamonts (>3 μm) (1). Developing stages were quantified as the number per field contained in 30 microscopic fields per well. Results are expressed as the number of developmental stages (DE) per field (mean number of DE in four replicate wells) and percent inhibition. Inhibition scores (IS) were assigned to all results as previously described (15). The IS assigned were 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 for inhibition levels of 0 to 30%, 31 to 55%, 56 to 70%, 71 to 90%, and 91 to 100%, respectively.

SCID mice are useful in evaluating new drugs against cryptosporidiosis (12). Thirty female C.B-17 scid/scid (SCID) mice, aged 7 weeks, were orally infected with 1 × 107 oocysts in 100 μl phosphate-buffered saline. Animals in individualized cages were allowed to develop chronic cryptosporidiosis for 25 days. For in vivo studies, Bobel-24 suspension with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) was performed. Infected mice were paired and divided as follows. Treatment A mice (n = 10) received 250 mg/kg/day of Bobel-24, treatment B mice (n = 10) received 125 mg/kg/day of Bobel-24, control PVP mice (n = 4) received PVP diluted in water, and infection control group mice (n = 6) received no treatment. All animals were treated orally for 2 weeks and euthanized 3 to 7 days after treatment ceased. Oocyst shedding was determined every 3 days by IIF from each group of paired infected animals. Concentrated fecal samples were examined by IIF (4). Results are shown as the number of oocysts per 50-μl concentrated fecal sample.

Data were analyzed by analyses of variance and least significant differences (14).

A significant (P < 0.05) inhibitory activity of Bobel-24 on C. parvum development was first observed when the infected HCT-8 cells were treated with 90 μM Bobel-24, with rates of growth inhibition reaching 99.6% (Table 1). No significant differences were found between Bobel-24 and PRM activities. However, treatment of sporozoite suspensions with Bobel-24 before using them to infect cells and previous treatment of noninfected cells showed IS of 0 and 1, respectively, suggesting that the effect of the compound on the C. parvum attachment and invasion processes was weaker. A dose-dependent inhibitory effect of Bobel-24 on C. parvum development was also observed (Table 2), and an IS of 4 was noted at concentrations between 45 and 90 μM, with growth inhibition rates of 99.5 to 96.5%.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of C. parvum forms in cell culture by prophylactic and therapeutic treatments with Bobel-24

| Treatment | Concn | Parasite counta | Growth inhibition

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Score | |||

| Bobel-24 | ||||

| Prophylactic treatment against sporozoitesb | 90 μM | 14.11 ± 2.28 | 27.8 | 0 |

| Prophylactic treatment against cellsc | 90 μM | 12.50 ± 2.18 | 36 | 1 |

| Therapeutic treatment against DEd | 90 μM | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 99.6 | 4 |

| PRM | 2 mg/ml | 0.89 ± 0.02 | 95.4 | 4 |

| Mucin | 0.2 mg/ml | 7.75 ± 0.39 | 60.4 | 2 |

| Medium + DMSO | 0.02% | 15.31 ± 2.11 | 21.7 | 0 |

| Medium | 19.56 ± 1.78 | 0 | 0 | |

Shown is the mean number of DE per field ± the standard deviation. Values were determined by counting meronts and gamonts (<3 μm) to avoid counting nonviable but adherent sporozoites and merozoites.

Sporozoite suspension incubated with Bobel-24 at 37°C for 30 min before use.

HCT-8 cells incubated with Bobel-24 at 37°C for 30 min before infection.

Treatment of infected HCT-8 cells with Bobel-24 at 37°C for 24 h in 5% CO2.

TABLE 2.

Dose-dependent inhibitory effect of Bobel-24 on C. parvum development

| Treatment | Concn | Parasite counta | Growth inhibition

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Score | |||

| Bobel-24 | 90 μM | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 96.5 | 4 |

| Bobel-24 | 45 μM | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 92.5 | 4 |

| Bobel-24 | 22 μM | 37.5 ± 1.4 | 50.1 | 1 |

| PRM | 2 mg/ml | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 94.8 | 4 |

| Medium + DMSO | 0.02% | 68.3 ± 4.9 | 18.2 | 0 |

| Medium | 75.2 ± 2.9 | |||

Shown is the mean number of DE per field ± the standard deviation. Values were determined by counting.

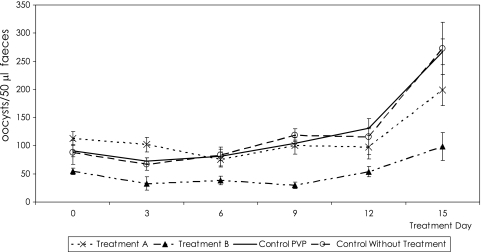

Results for the in vivo activity of Bobel-24 are shown in Fig. 2. Bobel-24 was not able to completely eliminate C. parvum development in treated SCID mice. However, statistical analysis of the number of oocysts excreted every 3 days during treatment showed significant differences when animals were treated with 125 mg/kg/day of Bobel-24 (P < 0.05).

FIG. 2.

C. parvum oocyst shedding during 2 weeks of treatment with Bobel-24.

Testing drugs for efficacy against C. parvum continues to be of clinical and veterinary interest because a drug that is completely effective against cryptosporidiosis is not available (7, 16).

Bobel-24 is a compound with an antiinflammatory activity similar to those of other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (10). It is a dual inhibitor of lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase, which play an important role in inflammatory response during diarrheic disease. For this reason, it would be reasonable to suppose that inhibition of those enzymes might result in an increase in fluid absorption, an important part of treatment for cryptosporidial infection. Moreover, Bobel-24 is considered an inhibitor of l-selectin, a molecule with the same origin as the sporozoite surface lectin (3). This lectin is considered a mediator of the initial interaction process between the parasite and the host cell, confirmed because exposure of C. parvum sporozoites to Gal/GalNAc and to bovine mucin reduced C. parvum attachment to biliary and intestinal epithelia up to 70% (3). Even though no antiprotozoal activity has been described for this compound to date, due to its action mechanisms described above, it may constitute a novel approach for treating cryptosporidiosis. To date, Bobel-24 is under clinical development as a potent leukotriene B4 synthesis inhibitor (17). Furthermore, Parreño et al. have synthesized three derivates of Bobel-24 (Bobel-4, Bobel-16, and Bobel-30) and have tested their activities as putative antileukemic agents (13). These authors found that Bobel-24 and Bobel-16 were dual inhibitors of cyclooxygenase and 5-lipoxygenase, whereas Bobel-4 and Bobel-30 were selective against 5-lipoxygenase.

In the present study, Bobel-24 showed notable and significant therapeutic activity in vitro, reaching 99.6% growth inhibition at a concentration of 90 μM. A dose-dependent inhibitory activity was also observed. There was no significant difference from the activity of PRM in vitro. This is outstanding, because PRM is a well-recognized drug with anticryptosporidial activity that is currently used to compare the activities of new candidates for cryptosporidiosis treatment. However, the in vitro prophylactic activity of Bobel-24 did not exceed an IS of 1. In contrast, the in vitro prophylactic activity of mucin was higher than when it was used for prophylactic treatment (IS of 2) but significantly lower (P < 0.05) than that of therapeutic treatment with 90 μM Bobel-24.

When the anticryptosporidial activity of Bobel-24 was studied in an animal model, a significant reduction in the number of oocysts excreted in the feces of infected SCID mice was only observed in animals treated with 125 mg/kg/day. However, Bobel-24 was not able to eradicate the parasite. Since lower doses of Bobel-24 showed higher anticryptosporidial activity, it is feasible that a problem in compound bioavailability may have occurred, as Bobel-24 is a poorly water-soluble agent that needs to be formulated with a polymer.

It must be pointed out that the doses used in this study are expected to be well tolerated on the basis of the general information provided by the manufacturers, who have studied the mutagenic potential of the drug in vitro and have conducted in vivo safety studies with rodents and beagle dogs (product profile; Farma-Cros Ibérica, S.A., Madrid, Spain). Furthermore, a preliminary phase I clinical trial has been conducted with humans (17) with the only finding a slight, transient, and not clinically relevant hypothyroidism that agrees with a previous report of T3 receptor blockade at high concentrations in Xenopus laevis (8).

It is known that demonstration of the activity of a drug in vitro does not guarantee its function in in vivo models. However, it is generally accepted that drugs are unlikely to inhibit C. parvum in vivo without inhibiting it in vitro. Moreover, nitazoxanide, considered to date a very promising drug for human cryptosporidiosis treatment, was highly effective in cell culture, partially effective in the piglet diarrhea model, and ineffective in the anti-gamma interferon-conditioned SCID mouse model (15). Thus, Bobel-24 merits consideration and further investigation as a therapeutic option in the treatment of cryptosporidiosis.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Linda Hamalainen for helpful revision of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Fundación San Pablo-CEU (11/03) and FEDER (1FD97-1168-CO3-03) and by the Agencia de Desarrollo Económico de Castilla y Leon (04/04/SA/0003).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arrowood, M. J. 2002. In vitro cultivation of Cryptosporidium species. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:390-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrowood, M. J., L. T. Xie, and M. R. Hurd. 1994. In vitro assays of maduramicin activity against Cryptosporidium parvum. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 41:23S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, X. M., and N. F. LaRusso. 2000. Mechanisms of attachment and internalization of Cryptosporidium parvum to biliary and intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 118:368-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.del Aguila, C., G. P. Croppo, H. Moura, A. J. Da Silva, G. J. Leitch, D. M. Moss, S. Wallace, S. B. Slemenda, N. J. Pieniazek, and G. S. Visvesvara. 1998. Ultrastructure, immunofluorescence, Western blot, and PCR analysis of eight isolates of Encephalitozoon (Septata) intestinalis established in culture from sputum and urine samples and duodenal aspirates of five patients with AIDS. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1201-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denizot, F., and R. Lang. 1986. Rapid colorimetric assay for cell growth and survival. Modifications to the tetrazolium dye procedure giving improved sensitivity and reliability. J. Immunol. Methods 89:271-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García-Capdevila, L., C. Lopez-Calull, S. Pompermayer, C. Arroyo, A. M. Molins-Pujol, and J. Bonal. 1998. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of Bobel-24 in biological samples for pharmacokinetic, metabolic and tissue distribution studies. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 708:169-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hashim, A., G. Mulcahy, B. Bourke, and M. Clyne. 2006. Interaction of Cryptosporidium hominis and Cryptosporidium parvum with primary human and bovine intestinal cells. Infect. Immun. 74:99-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kudo, Y., and K. Yamauchi. 2005. In vitro and in vivo analysis of the thyroid disrupting activities of phenolic and phenol compounds in Xenopus laevis. Toxicol. Sci. 84:29-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laurent, F., D. McCole, L. Eckmann, and M. F. Kagnoff. 1999. Pathogenesis of Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Microbes Infect. 1:141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez-Belmonte, J., and J. A. Norton. 1999. Protection against colonic injury by 5-lipoxigenase inhibitors: a comparative study. Med. Inflamm. 8:S154. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez-Belmonte, J., and A. J. Norton. 1997. Protection against chronic colonic inflammation by Bobel-246: effect on cellular infiltration, 5-lipoxygenase and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Inflamm. Res. 46:S256. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mead, J. R., X. You, J. E. Pharr, Y. Belenkaya, M. J. Arrowood, M. T. Fallon, and R. F. Schinazi. 1995. Evaluation of maduramicin and alborixin in a SCID mouse model of chronic cryptosporidiosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:854-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parreño, M., J. P. Vaque, I. Casanova, P. Frade, M. V. Cespedes, M. A. Pavon, A. Molins, M. Camacho, L. Vila, J. F. Nomdedeu, R. Mangues, and J. Leon. 2006. Novel triiodophenol derivatives induce caspase-independent mitochondrial cell death in leukemia cells inhibited by Myc. Mol. Cancer Ther. 5:1166-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steel, R. G. D., and J. H. Torrie. 1980. Principles and procedures of statistics, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill International Book Company, New York, NY.

- 15.Theodos, C. M., J. K. Griffiths, J. D'Onfro, A. Fairfield, and S. Tzipori. 1998. Efficacy of nitazoxanide against Cryptosporidium parvum in cell culture and in animal models. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1959-1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson, R. C., M. E. Olson, G. Zhu, S. Enomoto, M. S. Abrahamsen, and N. S. Hijjawi. 2005. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. Adv. Parasitol. 59:77-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trocóniz, I. F., I. Zsolt, M. J. Garrido, M. Valle, R. M. Antonijoan, and M. J. Barbanoj. 2006. Dealing with time-dependent pharmacokinetics during the early clinical development of a new leukotriene B4 synthesis inhibitor. Pharm. Res. 23:1533-1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]