Methane oxidation can occur in both aerobic and anaerobic environments; however, these are completely different processes involving different groups of prokaryotes. Aerobic methane oxidation is carried out by aerobic methanotrophs, and anaerobic methane oxidizers, discovered recently, thrive under anaerobic conditions and use sulfate or nitrate as electron donors for methane oxidation (11, 104). This review will focus on the aerobic oxidation of methane.

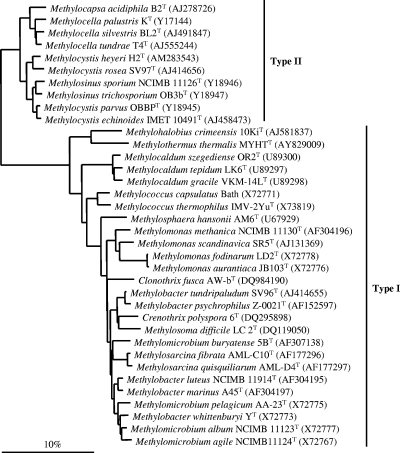

Aerobic methanotrophs are a unique group of methylotrophic bacteria that utilize methane as a sole carbon and energy source (52). Based on their cell morphology, ultrastructure, phylogeny, and metabolic pathways, methanotrophs can be divided into two taxonomic groups: type I and type II. Type I methanotrophs include the genera Methylobacter, Methylomicrobium, Methylomonas, Methylocaldum, Methylosphaera, Methylothermus, Methylosarcina, Methylohalobius, Methylosoma, and Methylococcus, which belong to the gamma subdivision of the Proteobacteria (Fig. 1). The type II methanotrophs Methylocystis, Methylosinus, Methylocella, and Methylocapsa are in the alpha subdivision of the Proteobacteria (52) (Fig. 1). Recently, two filamentous methane oxidizers have been described, Crenothrix polyspora (113), which has a novel pmoA, and Clonothrix fusca (125), which has a conventional pmoA. Both are gammaproteobacteria and are closely related to the type I methanotrophs. Most extant methanotrophs are cultured at 20 to 45°C and neutral pH but have also recently been isolated from extreme environments (reviewed in reference 122).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequences of the type strains of methanotrophic bacteria. The dendrogram was produced with DNADIST (neighbor-joining) analysis using 1,245 bp of aligned sequence. The phylogenetic tree was rooted to Methylobacterium extorquens (AF531770).

The first step in the oxidation of methane to CO2 is the conversion of methane to methanol by the enzyme methane monooxygenase. There are two forms of this enzyme: a particulate membrane bound form (pMMO) and a soluble cytoplasmic form (sMMO). The pMMO has been reported in all methanotrophs except for the genus Methylocella (121), whereas the sMMO is present only in certain methanotroph strains (94). The pMMO is a membrane bound copper and iron containing enzyme (reviewed in reference 49). The structural genes for this enzyme have been cloned and sequenced from Methylococcus capsulatus Bath (107, 114), Methylocystis sp. strain M, and Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b (45). They lie in a three-gene operon, pmoCAB, which code for three integral membrane polypeptides of approximately 23, 27, and 45 kDa, respectively. These operons are present in duplicate copies in all three organisms. These duplicate copies of pmoCAB are virtually identical and are transcribed from σ70-type promoters found upstream of the pmoC gene (45, 110).

The sMMO is a cytoplasmic enzyme containing a unique di-iron site at its catalytic center. It has a broad substrate range, including trichloroethylene, alkanes, alkenes, and aromatic compounds. The biochemistry of the sMMO has been studied in detail (reviewed in reference 75). It consists of three components: a hydroxylase, which is a dimer of three subunits, (αβγ)2; a regulatory protein (protein B); and a reductase (protein C). It is encoded by a six-gene operon (19, 111) containing the genes encoding the α, β, and γ subunits of the hydroxylase (mmoXYZ), the reductase (mmoC), and a regulatory or coupling protein (mmoB). There is one other gene in the operon, orfY (mmoD), which has no known homologues in the public database but may play a role in assembly of the unique di-iron center of the sMMO enzyme (90).

Methanotrophs can be isolated from a wide variety of environments including air, the tissues of higher organisms, soils, sediments, and freshwater and marine systems and are all obligately aerobic, gram-negative bacteria. Methanotrophs play an important role in the oxidation of methane in the natural environment, oxidizing methane biologically produced in anaerobic environments by the methanogenic archaea and thereby reducing the amount of methane released to the atmosphere. Methane-oxidizing bacteria also oxidize methane from the atmosphere (i.e., at very low concentrations [ca. 1.7 ppm]), particularly in upland soils and forest soils, thereby mitigating global warming due to the effects of the greenhouse gas methane (25). Understanding this ability to oxidize atmospheric concentrations of methane, as well as the search for the organisms responsible, has occupied many researchers for the past decade, and many of the techniques developed to study the microbial ecology of the methanotrophs, which will be discussed here, have led to insights into atmospheric methane oxidation. Consequently, some of these studies into atmospheric methane oxidation are highlighted in this review.

IDENTIFYING MOLECULAR MARKERS

The key to identifying marker genes suitable for use in molecular ecology studies of organisms is the availability of sequences in a database from which to design primers. One obvious marker is the 16S rRNA gene due to the large database of sequences available, and also when new organisms are described, their 16S rRNA gene is always sequenced and thus becomes available for determining the origins of sequences obtained in molecular ecology studies. A complementary option for molecular ecology studies is a functional gene that is unique to the physiology and metabolism of the organisms being studied. Functional marker genes have two major advantages over housekeeping genes. First, they narrow down the investigation to the studied functional group, thus enabling a much higher sensitivity of detection in complex environments. Second, putative uncultivated members of the functional group can also be identified in most cases simply based on the presence of a homologous gene sequence. In contrast, with housekeeping genes, such as the 16S rRNA gene, a novel sequence may indicate the phylogenetic relatedness of the carrying bacterium but gives few clues about its physiology.

For the methanotrophs, their unique functional gene/enzyme is methane monooxygenase (pMMO and sMMO), with two genes, pmoA and mmoX, being of particular use in molecular ecology studies. pmoA genes have been sequenced from a considerable number of methanotrophs and a large data set of partial sequences is also available in GenBank from a number of different environmental studies. The sMMO gene cluster has been sequenced from Methylococcus capsulatus Bath (111), Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b (19), Methylosinus sporium 5 (1), Methylocystis sp. (46, 89), Methylocella silvestris BL2 (121), and Methylomonas sp. (108); however, the data set of mmoX sequences available still remains relatively small. Both pmoA and mmoX have been shown to produce phylogenies largely congruent with the 16S rRNA phylogenies of the same organisms (59, 74). Other functional gene markers which are not unique to the methanotrophs, but which have suitable datasets available, can still be used to identify a particular gene sequence as belonging to a methanotroph. In this group of molecules, mxaF (coding for the large subunit of methanol dehydrogenase) (87, 98), nifH (which encodes dinitrogen reductase, a key component of the nitrogenase enzyme complex) (3, 34) and fhcD (which encodes the D subunit of the formyltransferase/hydrolase complex, part of the H4MPT-linked C1-transfer pathway) (66) have been used to identify methanotrophs in environmental samples.

DIVERSITY AND DISTRIBUTION: 16S rRNA GENES

The first studies using 16S rRNA gene probes to target methanotrophs/methylotrophs were those of Hanson and coworkers, who studied the phylogeny of extant methanotrophs (16, 123). These researchers described probes 9α and 10γ (Table 1), which targeted serine pathway and ribulose monophosphate (RuMP) pathway methylotrophs, respectively (123). These primers have been used in a number of PCR-based studies to detect methanotrophs (92) or used in denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) analysis of methanotroph communities (54, 55). However, the drawback of these probes is that they target methylotrophs and are not methanotroph specific. Probes were designed that targeted only methanotrophs (1034-Ser and 1035-RuMP) (16); however, these have received little use in studies of methanotroph diversity (92). The first genus-specific methanotroph primers designed (Mb1007, Mc1005, Mm1007, and Ms1020 [58]; see Table 1) targeted the genera Methylobacter, Methylococcus, Methylomonas, and Methylosinus and have been used in a number of studies examining methanotroph diversity both as radiolabeled probes and as PCR primers (27, 67, 84). Type I and type II methanotroph-specific primers (MethT1dF, MethT1bR, and MethT2R; see Table 1) were designed to examine methanotroph diversity in landfill soil (129) and have been widely used (7, 38, 62). Recently, two studies have provided a large collection of group-specific 16S rRNA probes for the detection of methanotrophs (39, 48). Very recently, Chen et al. (21) designed new primer sets targeting type I and type II methanotrophs, respectively. These primer sets can amplify 16S rRNA genes from almost all known methanotrophs, including the genera Methylocaldum, Methylosphaera, Methylocella, and Methylocapsa, which were not amplified using previous primer sets. These primers sets were used successfully to analyze methanotroph 16S rRNA genes and transcripts from a landfill cover soil (21). To date, only a few of these sets of methanotroph-specific 16S rRNA probes have been used in environmental studies (7, 39); however, this is a very useful resource for future studies (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

16S rRNA gene probes targeting methanotrophs

| Type and probe | Sequence (5′-3′) | Target | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I methanotroph probes | |||

| 10γ | GGTCCGAAGATCCCCCGCTT | RuMP pathway methylotrophs | 123 |

| 1035-RuMP | GATTCTCTGGATGTCAAGGG | RuMP pathway methanotrophs | 16 |

| Mb1007a | CACTCTACGATCTCTCACAG | Methylobacter (Methylomicrobium)a | 58 |

| Mc1005 | CCGCATCTCTGCAGGAT | Methylococcus | 58 |

| Mm1007 | CACTCCGCTATCTCTAACAG | Methylomonas | 58 |

| MethT1dF | CCTTCGGGMGCYGACGAGT | Type I methanotrophs | 129 |

| MethT1bR | GATTCYMTGSATGTCAAGG | Type I methanotrophs | 129 |

| Type 1b | GTCAGCGCCCGAAGGCCT | Type I methanotrophs | 4 |

| Gm633 | AGTTACCCAGTATCAAATGC | Methylobacter and Methylomicrobium | 48 |

| Gm705c | CTGGTGTTCCTTCAGATC | Gamma methanotrophs except Methylocaldum | 48 |

| Mlb482 | GGTGCTTCTTCTAAAGGTAATGT | Methylobacter | 48 |

| Mlb662d | CCTGAAATTCCACTCTCCTCTA | Methylobacter | 48 |

| Mmb482 | GGTGCTTCTTCTATAGGTAATGT | Methylomicrobium | 48 |

| Mlm482 | GGTGCTTCTTGTATAGGTAATGT | Methylomonas | 48 |

| Mlm732a | GTTTTAGTCCAGGGAGCCG | Methylomonas group A | 48 |

| Mlm732b | GTTTGAGTCCAGGGAGCCG | Methylomonas group C | 48 |

| Mlc123 | CACAACAAGGCAGATTCCTACG | Methylococcus | 48 |

| Mlc1436 | CCCTCCTTGCGGTTAGACTACCTA | Methylococcus | 48 |

| Mcd77 | GCCACCCACCGGTTACCCGGC | Methylocaldum | 48 |

| Mγ84 | CCACTCGTCAGCGCCCGA | Type I methanotrophs | 39 |

| Mγ669d | GCTACACCTGAAATTCCACTC | Methylobacter and Methylomonas | 39 |

| Mγ983 | TGGATGTCAAGGGTAGGT | Type I methanotrophs | 39 |

| Mγ993 | ACAGATTCTCTGGATGTC | Type I methanotrophs | 39 |

| Mγ1004a | TACGATCTCTCACAGATT | Methylomicrobium | 39 |

| Mh996r | CACTCTACTATCTCTAACGG | Methylosphaera | 67 |

| Type IF | ATGCTTAACACATGCAAGTCGAACG | Type I methanotrophs | 21 |

| Type IR | CCACTGGTGTTCCTTCMGAT | Type I methanotrophs | 21 |

| Type II methanotroph probes | |||

| 9α | CCCTGAGTTATTCCGAAC | Serine pathway methylotrophs | 123 |

| 1034-Ser | CCATACCGGACATGTCAAAAGC | Serine pathway methanotrophs | 16 |

| Ms1020 | CCCTTGCGGAAGGAAGTC | Methylosinus | 58 |

| Type 2b | CATACCGGRCATGTCAAAAGC | Type II methanotrophs | 27 |

| MethT2R | CATCTCTGRCSAYCATACCGG | Type II methanotrophs | 129 |

| Am455b | CTTATCCAGGTACCGTCATTATCGTCCC | Alpha methanotrophs | 48 |

| Am976 | GTCAAAAGCTGGTAAGGTTC | Alpha methanotrophs | 48 |

| Ma464 | TTATCCAGGTACCGTCATTA | Type II methanotrophs | 39 |

| Mcell-1026 | GTTCTCGCCACCCGAAGT | Methylocella palustris | 32 |

| AcidM-181 | TCTTTCTCCTTGCGGACG | Methylocella palustris and Methylocapsa acidiphila | 32 |

| Mcaps-1032 | CACCTGTGTCCCTGGCTC | Methylocapsa acidiphila | 33 |

| Msint-1268 | TGGAGATTTGCTCCGGGT | Methylosinus trichosporium | 33 |

| Msins-647 | TCTCCCGGACTCTAGACC | Methylosinus sporium | 33 |

| Mcyst-1432 | CGGTTGGCGAAACGCCTT | All Methylocystis spp. | 33 |

| Type IIF | GGGAMGATAATGACGGTACCWGGA | Type II methanotrophs | 21 |

| Type IIR | GTCAARAGCTGGTAAGGTTC | Type II methanotrophs | 21 |

Primers targeting groups of methanotrophs not previously covered by 16S rRNA probes were also recently published, which included Methylosphaera (67), Methylocella (32), Methylocystis, Methylosinus, and Methylocapsa (33). Therefore, 16S rRNA gene probes and primers are now available that cover the majority of known methanotroph diversity. Methanotroph diversity has also been studied using universal bacterial 16S rRNA primers in clone library studies and in DGGE (42).

The majority of studies of methanotroph diversity, targeting the 16S rRNA gene, have involved the use of DGGE to examine sequence variation between environmental samples. One study has focused on new DDGE strategies for examining methanotroph diversity using different combinations of the existing 16S rRNA gene primers (7). In that study, 10 different combinations of eubacterial and methanotroph-specific (48, 129) 16S rRNA gene primers were analyzed. For type I methanotroph communities, all of the combinations tested gave identical results, and the detection methods used either a nested approach with a first round of PCR with the MethT1dF-MethT1bR primer pair (129) and a second round with either 533f/MethT1bRGC, 357fGC/518r, or 533f/907rGC (129) or else direct amplification with the primer pair 533f/Meth1bRGC (Table 1). For type II methanotroph communities, the primer pair 533f/MethT2RGC (129) can be used where Methylosinus sporium strains are not of major importance since no nonmethanotroph species are amplified. When total type II methanotroph diversity is to be targeted then primer pair 533f/Am976GC (48) is recommended, although nonspecific amplification has to be considered. For both type I and II methanotrophs, the direct 16S rRNA gene PCR amplification strategy is recommended in environments where the abundance of methanotrophs is anticipated to be high. In environments being studied where methane oxidation activity is low (and thus the abundance of methanotrophs is low), the nested strategies can be used (7).

Recently, 16S rRNA probes Gm705 and Am445 (48), specific for the Methylococcaceae and Methylocystaceae, were used in quantitative hybridizations to determine the relative abundance of methanotrophs involved in atmospheric methane oxidation in forest soils (77). That study revealed that methanotrophic members of the Methylocystaceae were one order of magnitude more abundant than Methylococcaceae in forest soils oxidizing methane at atmospheric concentrations.

DIVERSITY AND DISTRIBUTION: FUNCTIONAL GENES

Several functional genes have been used for the detection of methanotrophs in environmental samples. The first to be utilized were primers targeting the gene encoding the large subunit of methanol dehydrogenase (mxaF) (85), an enzyme not unique to methanotrophs but which is found in all gram-negative methylotrophic bacteria. The primers (f1003 and r1561 [f1003/r1561]) were designed with sequence information from only three methylotrophic bacteria (Methylobacterium extorquens, Methylobacterium organophilum, and Paracoccus denitrificans) but are still being used in their original form 10 years later. These primers were first used to investigate diversity in a study examining methane-oxidizing bacteria in peat bogs (87). In that study the database of mxaF sequences from extant methanotrophs and methylotrophs was extended, and a novel group of methanotroph-like sequences were identified in the peat environment. Since that study, these primers have been used to examine many different environments and in DGGE analyses (42, 54, 56). Recently, a new mxaF primer set (1003f/1555r) for methanotrophs and gram-negative methylotrophs has been designed and validated using fourteen mxaF containing methylotrophs and/or methanotrophs and six negative control strains (98). Greater diversity of mxaF sequences has been retrieved from several environments using this primer set rather than the primer set 1003f/1561r (M. J. Cox and J. C. Murrell, unpublished data).

The second group of functional genes to be targeted were those encoding sMMO. Initial studies developed a probe to detect mmoB within the sMMO gene cluster (124). Subsequently, PCR primers were designed for five genes encoding the sMMO enzyme complex, mmoXYZB and -C (85). These were designed by using the only sMMO sequences available at the time from Methylococcus capsulatus Bath and Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b (19, 111). In this study (85) the mmoXYB and mmoC genes were amplified from several samples including peat, soil, sediment, freshwater and estuarine environments. Sequencing of several more sMMO gene clusters (46, 89, 108) facilitated the development of different PCR primer sets for the amplification of mmoX from methanotrophs (2, 4, 5, 44, 62, 63, 86, 91, 108) (Table 2). However, all of these studies have shown the limited diversity of sMMO genes in environmental samples, possibly because the gene targeted, mmoX, is a highly conserved gene or because primers available are designed from a limited database of sMMO sequences and are therefore inherently biased toward the sequences seen in extant methanotrophs. However, the greatest drawback of using primers targeting sMMO genes to examine methanotroph diversity is that only a subset of methanotrophs contains these genes. On the other hand, the analysis of sMMO-containing methanotrophs in a given environment may be a necessity since a recent study demonstrated that the facultative methanotroph, Methylocella silvestris BL2, contains only sMMO and not pMMO (121).

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used for amplification of mmoX genes from environmental samples

| Primer(s)a | Sequence (5′-3′) | Product size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| mmoXf882/mmoXr1403 | GGCTCCAAGTTCAAGGTCGAGC/TGGCACTCGTAGCGCTCCGGCTCG | 535 | 85 |

| mmoX1/mmoX2 | CGGTCCGCTGTGGAAGGGCATGAAGCGCGT/GGCTCGACCTTGAACTTGGAGCCATACTCG | 369 | 91 |

| 536f/877r | CGCTGTGGAAGGGCATGAAGCG/GCTCGACCTTGAACTTGGAGCC | 341 | 44 |

| mmoXr901b | TGGGTSAARACSTGGAACCGCTGGGT | 396c | 108 |

| A166f/B1401r | ACCAAGGARCARTTCAAG/TGGCACTCRTARCGCTC | 1,230 | 4 |

| 534f/1393r | CCGCTGTGGAAGGGCATGAA/CACTCGTAGCGCTCCGGCTC | 863 | 62 |

| met1/met4 | ACCAAGGAGCAGTTC/TCCAGAAGGGGTTGTT | 5 | |

| mmoX206f/mmoX886r | ATCGCBAARGAATAYGCSCG/ACCCANGGCTCGACYTTGAA | 719 | 63 |

Primer mmoX1 was located at positions 2008 to 2037, and primer mmoX2 was located at positions 2347 to 2376. Primers A166f and B1401r are also known as mmoXA and mmoXD.

mmoXr901_GC is also used for DGGE analysis with primer mmoX1 (64).

When used in PCR with the primer mmoX1.

The genes that have been studied most are those encoding particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO), which is present in all methanotrophs with the exception of Methylocella silvestris (121). The first oligonucleotide primers designed to amplify internal fragments of the genes encoding pMMO and AMO (ammonia monooxygenase) enzyme complexes were the A189f/A682r primer set (57) (Table 3). The phylogeny of pmoA/amoA is reasonably congruent with the 16S rRNA gene phylogeny of the organisms from which the gene sequences were retrieved (57, 74). Therefore, retrieval of pmoA and amoA sequences provides information on the diversity of these organisms in the environment. The A189f/A682r primers have been used extensively in environmental studies to provide a molecular profile of the methane-oxidizing community (15, 56, 59, 60, 62, 67, 103) and have proved useful in detecting novel sequences (59, 71, 99). However, a new reverse pmoA-specific primer mb661r, used in conjunction with the A189f primer, was designed (27, 109) (Table 3) and demonstrated specificity in amplifying pmoA sequences but not amoA sequences. This primer has been used to determine in situ populations of methanotrophs in freshwater environments (27) and deep-sea hydrothermal vents (95).

TABLE 3.

PCR primers used for amplification of pmoA genes from environmental samples

| Primer(s) | Sequence (5′-3′) | Product size (bp)b | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| A189fa/A682r | GGNGACTGGGACTTCTGG/GAASGCNGAGAAGAASGC | 525 | 57 |

| mb661 | CCGGMGCAACGTCYTTACC | 510* | 27 |

| pmof1/pmor | GGGGGAACTTCTGGGGITGGAC/GGGGGRCIACGTCITTACCGAA | 330 | 23 |

| pmof2/pmor | TTCTAYCCDRRCAACTGGCC | 178 | 23 |

| pmoA206f/pmoA703bd | GGNGACTGGGACTTCTGGATCGACTTCAAGGATCG/GAASGCNGAGAAGAASGCGGCGACCGGAACGACGT | 530 | 120 |

| A650r | ACGTCCTTACCGAAGGT | 478* | 15 |

| mb661r_nd | CCGGCGCAACGTCCTTACC | 510* | 78 |

| pmoAfor/pmoArev | TTCTGGGGNTGGACNTAYTTYCC/CCNGARTAYATHMGNATGGTNGA | 281 | 112 |

| f326/r643 | TGGGGYTGGACCTAYTTCC/CCGGCRCRACGTCCTTACC | 358 | 42 |

| Mb601 Rc | ACRTAGTGGTAACCTTGYAA | 432* | 74 |

| Mc468 Rc | GCSGTGAACAGGTAGCTGCC | 299* | 74 |

| II 223 Fc/II646 Rc | CGTCGTATGTGGCCGAC/CGTGCCGCGCTCGACCATGYG | 444 | 74 |

| Mcap630c | CTCGACGATGCGGAGATATT | 461* | 74 |

| Forest675 Rc | CCYACSACATCCTTACCGAA | 506* | 74 |

| Mb661 Rc | GGTAARGACGTTGCNCCGG | 491* | 74 |

Primer A189f is also known as A189gc.

*, that is, when used in PCR with the primer A189f.

Primers designed for real-time PCR quantification of subsets of methanotrophs.

Primer set that enables the simultaneous detection of pmoA1 and pmoA2 at an annealing temperature of 60°C but only enables detection of pmoA2 at 66°C (120).

The use of PCR primers to amplify amoA from ammonia oxidizers has been critically evaluated (100), with the amoA primers set of Rotthauwe et al. (106) recommended as the most suitable. A similar study was also carried out to evaluate the use of the available pmoA primer sets (15). In that study, a third reverse primer for PCR was designed, A650r, and three primer sets (A189f/A682r, A189f/mb661r, and A189f/A650r) were compared in studies of methanotroph diversity in Danish soils. The results indicated that the mb661r primer gave the best coverage of methanotroph diversity; however, the primers A682r and A650r detected novel groups of pmoA sequences, including the RA14 (Forest clone) group, which mb661r failed to detect. Furthermore, primer A682r excludes Methylocapsa, as well as genes from other uncultivated bacteria, which are indicated to be methane oxidizers (99). Therefore, several recent studies have used both the A189f/A682r and the A189f/mb661r primer sets in order to obtain the best coverage of methanotroph diversity (21, 63, 72, 78, 79, 93). Recently, a nested PCR approach has been taken to examine methanotroph diversity in Californian upland grassland soil. The primer pair A189f/A682r was used in the first PCR, with A189f/mb661r or A189f/A650r in the second round. This gave consistently high yields of pmoA amplicons (61). Another pmoA primer set, pmof1/pmor (23), was developed (Table 3), but these have not been widely used (5). Other primers have also been designed (42, 112, 120) but, to our knowledge, not used in other studies.

The pmoA PCR primer set A189f/A682r has been adapted for DGGE analysis, with the GC clamp being added to A189f (15, 37, 54, 55, 71). The use of degenerate pmoA primers in DGGE may cause the appearance of multiple bands for individual organisms, which in complex environments may cause confusion in the interpretation of results. The A682r primer has four redundancies within its sequence that causes multiple banding problems in DGGE analysis, as can be seen from multiple bands with control organisms (54). Other primer sets, A189/A650GC (15) and f326GC/r643 (42), have also been used for DGGE analysis of pmoA, but again both primer sets gave multiple bands with controls. Recently, a new nondegenerate primer (mb661r_nd) has been designed, based on the methanotroph specific primer mb661r, and this has been successfully used for the detection of methanotroph pmoA genes in an alkaline soda lake (Mono Lake), without the production of multiple bands with controls (78), although these primers require further testing on other environmental samples in order to prove their value in determining methanotroph diversity.

Alternative approaches for analyzing pmoA diversity include terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP), a rapid, sensitive method potentially avoiding the bias during cloning. T-RFLP is preferable in some cases since it also produces semiquantitative data. The first application of pmoA T-RFLP was reported by Horz et al. (62), and it has been widely used in a number of subsequent studies (18, 60, 61).

Besides the analyses using phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs), which is discussed below, a number of studies of atmospheric methane oxidation have utilized the pmoA gene PCR primers to determine which groups of methanotrophs are involved. One of the first studies identified a novel pmoA group, RA14, closely related to type II methanotrophs (Alphaproteobacteria), which were suggested to represent the methanotrophic bacteria responsible for atmospheric methane oxidation (59). A second study also identified pmoA sequences from forest soils that were closely related to RA14 (55), which is usually called the “forest sequence cluster.” The novel cluster is commonly detected in acidic upland soils and forest soils and has now been called the USCα (for upland soil cluster α) (71). That study also detected a novel group of pmoA sequences distantly related to those of known type I methanotrophs (Gammaproteobacteria). This novel upland soil cluster γ (USCγ) was more likely to be detected in soils with pH greater than 6.0 than in more acidic soils. A study of a Californian upland grassland soil also identified pmoA sequences that clustered either with the USCα or with the USCγ (61), and a study of tropical upland soils from Thailand only identified USCα-related pmoA sequences in the two most acidic forested soils (pH 4.2), while these sequences were not detected in a third agricultural soil (pH 5.6), which also had lower atmospheric methane oxidation rates (72). Another study has revealed a novel group of Alphaproteobacterial methanotrophs from a methane-consuming neutral pH soil (105); these were referred to as cluster I and were previously detected in isolates from tundra soil (99). Subsequently, a study of two forest soils consuming atmospheric methane, one acidic and the other neutral pH, revealed the dominance of USCα pmoA sequences in the acidic soil and dominance of cluster I pmoA sequences in the neutral soil (73).

A number of recent studies have focused on the analysis of expression of methane monooxygenases in the environment using these pmoA and mmoX primer sets. This included the analyses of soil (51, 73), freshwater sediment (23, 96), landfill (21), and peatlands (22), providing direct in situ evidence of active methanotroph populations. It is interesting that only pMMO transcripts could be readily detected from all of these studies which may indicate that pMMO is largely responsible for methane oxidation in these environments.

DIVERSITY AND ABUNDANCE: QUANTIFICATION OF METHANOTROPHS

The traditional method for enumerating methanotrophs in environmental samples has been most-probable-number (MPN) cultivation. Although useful for isolation of methanotrophs this approach may be limited by cultivation bias but is still widely used. In fact, a study was carried out that looked at the effect of different media on the MPN counts of methanotrophs in lake sediment (18). These researchers found cell numbers four- to sixfold higher in a new medium (7 × 104 per ml) than with conventional Whittenbury medium (128); another study in lake sediments found 105 to 106 methanotrophs per g (38). Several studies have measured methanotroph numbers in the rice root rhizosphere and found 104 × 109 per g of soil (14). Methanotroph numbers have also been determined by MPN in trichloroethylene-contaminated aquifers (103 to 105 per g) (119), swamp sediment (106 to 107 per ml) (92), and wet meadow soil consuming atmospheric CH4 (105 to 107 per g) (60). Methanotrophs have also been enumerated by slot blot hybridizations with methanotroph-specific probes (26, 115); however, this approach has not been widely used. Costello et al. (26) probed slot blots with type I (type 1b)- and type II (type 2b)-specific probes (Table 1) to estimate the abundance of methanotrophs in a freshwater lake sediment. The total number of type I methanotrophs was estimated to be 3.4 × 108 to 6.7 × 108, with the number of type II methanotrophs estimated to be 2.3 × 107 to 6.8 × 107, and these researchers also used a pmoA probe and found 2.1 × 108 to 9.0 × 108 cells per g. These numbers are within the range estimated from methane oxidation rates of 1.3 × 108 to 1.2 × 109 cells per g of sediment and demonstrate the ability of this technique to estimate methanotroph abundance in environmental samples.

More recently, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) targeting the 16S rRNA gene has been used to identify (39) and enumerate (32, 33) methanotrophs using many of the probes described earlier (see Table 1). Two studies of acidic peat using FISH to enumerate methanotrophs showed that the numbers of methanotrophs were around 106 cells per g of peat and that Methylocella and Methylocystis spp. were the predominant methanotrophs (60 to 95%) in an acidic Sphagnum peat bog (32, 33). One of the disadvantages of using FISH to enumerate methanotrophs is that it can only be used when the 16S rRNA genes of the target organisms are known. Due to the many diversity studies of methanotrophs using pmoA phylogeny, many novel groups of methanotrophs can only be identified by pmoA sequence; hence, FISH cannot be used to enumerate these organisms. However, a recent study has linked the use of functional genes in methanogens with FISH (76), a technique that may prove useful in the future for the detection of methanotrophs. Therefore, other techniques have been developed that target the pmoA gene, including competitive reverse transcriptase PCR (51) and real-time PCR (50, 73, 74) assays. The competitive reverse transcription-PCR approach was developed for both pmoA and mmoX using internal RNA standards and capillary electrophoresis and was successfully used to quantify the amount of mRNA transcript in both whole cells and a model soil slurry system (51). To our knowledge, this has yet to be applied further to examine environmental samples. The quantitative real-time PCR assay for methanotrophs was developed from a method using SYBR green, previously used for detecting other bacteria, and pmoA specific primers designed to target five different groups of methanotrophs in real-time PCR (74). This assay was successfully used to quantify the methanotroph community in a number of environments, including a flooded rice field soil (74), forest soils (73), and periodically water-saturated gleyic soils (70). More than 107 pmoA molecules per g of soil were detected in the water-saturated gleyic soils (70), a result comparable to population sizes of methanotrophs found in other upland soils consuming atmospheric CH4 by MPN analysis (60). Real-time PCR has also been used to monitor the population changes of type I methanotrophs during composting of organic matter using probe MB10γ targeting the 16S rRNA gene, showing a maximum of 109 cDNA copies/g of compost, with the lowest numbers (107 cDNA copies/g) observed during the thermophilic phase (50).

DIVERSITY AND FUNCTION-ACTIVITY: STABLE ISOTOPE PROBING

Stable isotope probing (SIP) is a method that attempts to link the identity of an organism with its biological function under conditions approaching those in situ (101, 102) and has been recently reviewed (35, 43, 88). The principle of SIP is based on the natural abundance of 13C being approximately only 1%. Consequently, the addition of 13C-labeled (>99%) substrate to an environmental sample will result in 13C labeling of the actively dividing bacteria as the 13C-labeled substrate is being used as a carbon source and is only incorporated into DNA during DNA synthesis and replication. The 13C-labeled DNA can be separated from the 12C-labeled DNA of the bacteria that do not assimilate the labeled substrate by CsCl density gradient centrifugation (35, 43).

SIP can also be carried out with RNA (RNA-SIP). One key advantage of RNA-SIP is the natural amplification of the phylogenetic signature molecule rRNA in active cells. RNA also becomes 13C labeled much more rapidly than DNA in densely populated bioreactor samples, suggesting that RNA-SIP may have greater sensitivity than DNA-SIP (80, 81, 82, 127). A study of a soil ecosystem (81) successfully used 13C-labeled methanol (CH3OH) to examine the diversity of methylotrophs, combining the use of both RNA-SIP and DNA-SIP. After just 6 days incubation, methylotroph-specific 13C-labeled rRNA was detected and contained high numbers of 16S rRNA gene clones from the genus Methylobacterium and also a novel group of Betaproteobacteria which were close relatives of the genus Methylophilus. After 42 days of incubation, the 13C-labeled DNA was dominated by 16S rRNA sequences closely related to Methylophilus, suggesting that constant high availability of methanol in the experiment had stimulated and enriched for this group of methylotrophic organisms.

A number of studies have utilized SIP to study the functionally active methanotroph populations in environmental samples (20, 63, 79, 93, 103). The 16S rRNA gene libraries that were constructed in these studies from the [12C]DNA revealed that the methanotrophs made up a small percentage of the library (103) or were not detected (93), a fact which was common with other studies of 16S rRNA gene libraries looking at methanotroph diversity (84). However, 16S rRNA gene libraries constructed from [13C]DNA extracted from environmental samples incubated with 13CH4 contained a high percentage of methanotroph sequences, 32 to 96% of clones sequenced (63, 79, 93, 103). SIP studies with 13CH4 have also revealed a number of sequences whose role in methane oxidation is unclear. Sequences were detected that were closely related to Bdellovibrio sp. (63, 93) and Cytophaga sp. (93, 103), which may have resulted from the turnover of 13C due to predation. SIP can also reveal potentially novel groups of putative methane-oxidizing bacteria that might reside within the Betaproteobacteria (63, 79, 93, 103).

SIP studies with 13CH4 have also looked at the diversity of methanotroph functional genes. In several studies, pmoA diversity was examined before and after SIP (79, 93, 103). In all of these environments, the pmoA diversity was lower in the [13C]DNA than in the [12C]DNA fraction. In peat soil using the pmoA A189f/A682r primer set, the majority of sequences in the [12C]DNA fraction were amoA sequences from ammonia oxidizing bacteria, while in the [13C]DNA fraction, the majority of sequences were pmoA sequences similar to those from extant type II methanotrophs, indicating that in this peat soil environment, the type II methanotrophs are the bacteria that are actively assimilating methane (93). In Russian soda lake sediments, both type I and type II methanotroph pmoA sequences, but no amoA sequences, were detected prior to SIP (79). However, after SIP all of the pmoA sequences isolated were closely related to pmoA sequences from extant type I methanotrophs, indicating that type I methanotrophs were actively assimilating methane in this high pH environment (around pH 10).

Recently, SIP has been used in a metagenomic analysis of a forest soil (36). In that study a complete methane monooxygenase operon (pmoCAB) was cloned into a bacterial artificial chromosome vector. Analysis of the pmoA sequence indicated that the clone was most similar to a Methylocystis sp. previously detected in this forest soil. That study demonstrated that reasonably large DNA fragments from uncultivated bacteria can be isolated using DNA-SIP and cloned for metagenomic analysis. This method was used by Neufeld et al. (97) to retrieve a 10-kb fragment containing mxaF from the metagenome. These authors demonstrated that long incubation and high substrate consumption used in early DNA-SIP experiments can be overcome by the use of short incubation times with low concentrations of substrates and subsequent multiple displacement amplification of the small amounts of 13C-labeled DNA obtained in such DNA-SIP experiments. Similar approaches were successfully applied to analyze uncultivated methanotrophs from acidic peatlands and demonstrated that gene clusters from uncultivated Methylocystis spp. could be retrieved by combining multiple displacement amplification, DNA SIP and metagenomics (Y. Chen and J. C. Murrell, unpublished data).

MICROARRAYS

DNA microarray (microchip, biochip, and gene chip) technology allows the parallel analysis of highly complex gene mixtures in a single assay and thus symbolizes the (post)genomic era of high-throughput science. Although microarrays initially emerged as tools for genome-wide expression analysis and are nowadays routinely used for this purpose, they are also increasingly being developed for diagnostic applications. Microbial diagnostic microarrays (MDMs) consist of nucleic acid probe sets, with each probe being specific for a given strain, subspecies, species, genus, or higher taxon (8).

The first MDM to target methanotrophs was a prototype functional gene array that targeted genes involved in nitrogen cycling, including nitrite reductase (nirS and nirK), ammonia monooxygenase (amoA), and particulate methane monooxygenase (pmoA) genes (130). The array contained 11 pmoA and 11 amoA gene fragments. That study indicated the potential of microarrays for revealing functional gene composition in natural microbial communities. A new version of this array was published recently (53) and included 174 probes for AMO, 241 probes from pMMO, and 57 probes for sMMO. An MDM was specifically developed for the detection and community analysis of methanotrophs (10). The microarray consisted of 59 oligonucleotide probes designed and fully validated against the pmoA genes of all known methanotrophs and amoA of the ammonia-oxidizing, nitrifying bacteria. The probes applied on this array were short oligonucleotides (i.e., 18 to 27 nucleotides), reliably discriminating a perfect match target and one with two mismatches, but in several cases also enabling single nucleotide discrimination. The potential of the pmoA microarray was tested with environmental samples, and the results were in close agreement with those of clone library sequence analysis (10). The microarray was then applied to analyze the methanotroph communities in landfill cover soils (20, 116). The results demonstrated that type II methanotrophs of the Methylocystis sp. were found to be the dominant methanotrophic member of this community, along with the type I methanotroph Methylocaldum sp., which had previously not been found in landfill soils (129). The results clearly reflected spatial trends in depth profiles of the landfill site samples. The pmoA MDM has also been used to monitor the success of methanotroph enrichments from hot water samples and as a first screen tool to assess the methanotroph diversity in various forest soils. Finally, an unanticipated result indicated the potential of the pmoA MDM to detect environmental perturbations by revealing an unexpected methanotroph community structure that was eventually shown to be linked to a disruption in the methane supply (116). Recently, an mRNA-based application of MDMs was successfully tested using a pmoA microarray for methanotrophs (9, 22) and may provide additional information on composition and functioning of microbial communities provided by DNA-based microarrays. The pmoA MDM has been upgraded (116), the latest version being comprised of 138 probes (L. Bodrossy, unpublished data).

An MDM targeting nifH genes was recently used to investigate the distribution and diversity of nitrogen-fixing microorganisms, and a number of the organisms identified were methanotrophs (65). MDMs allow for the rapid analysis of bacterial communities at a high resolution, with one researcher being able to analyze 40-plus samples per week, from DNA preparation through to analysis of results, a process which would take months with the clone library approach. Although the throughput of the MDM approach is comparable to that of DGGE or thermal gradient gel electrophoresis and T-RFLP, its phylogenetic resolution is much higher. The pmoA MDM currently resolves all known genera of methanotrophs, most of them down to the level of species or at least groups of species. The probe set on microarrays is limited to microbes with already sequenced genes, which means that data collected from environmental clone libraries have an important role in the continual development of the microarray. These studies have demonstrated that, by combining high resolution, high throughput and affordable overall costs, microarrays are a powerful tool for mapping the spatial and temporal variability and dynamics of microbial community structure in the environment.

OTHER MOLECULAR MARKERS: LIPIDS

Methanotrophs contain unique PLFAs (47). The unique PLFAs are 16:1ω5t, 16:1ω6c, and 16:1ω8c in type I methanotrophs and 18:1ω8c in type II methanotrophs. The measurement of these signature PLFAs has been widely used to estimate the biomass distribution of type I and II methanotrophs in environments well supplied with methane (12, 117). In environments where there is little methane, i.e., upland forest soils, it was suggested that these PLFAs should not be used as biomarkers (118). The sensitivity of PLFA-SIP makes it especially powerful for identifying active methanotrophs and their community structure in the environment (reviewed in reference 40). The use of 13CH4 to isotopically label the PLFAs of methanotrophs in a soil from a temperate forest increased the sensitivity of detection of the PLFAs and provided evidence of methane assimilation at true atmospheric concentrations (17). The incorporation of 13C into PLFAs has been used in other studies of atmospheric methane oxidation (71, 83), with both studies suggesting the presence of novel type II methanotrophs. 13C-labeled PLFA analyses were also used to study methanotrophs in high-methane environments, including landfill cover soils (28), acidic peatland soils (22), and freshwater sediment (13). However, great care should be taken in interpreting PLFA data since the PLFA database for methanotrophs is much less extensive than the 16S rRNA and functional gene databases. For example, a recent study showed that Methylocystis heyeri strains (type II methanotrophs) contained large amounts of 16:1ω8c, a PLFA that was previously thought to be associated with type I methanotrophs only (31). In another study, Chen et al. suggested that acid tolerant, acidophilic type II methanotrophs may contain PLFAs that are different from their neutral pH counterparts (22).

Intact phospholipid profiles have also been used to identify methanotrophs, with two major classes of phospholipid being found (41). That study suggests that this technique can be very useful in bacterial chemotaxonomy, but this has yet to be applied to environmental samples. Finally, specific hopanoids produced by methane oxidizing bacteria were identified by labeling with 13C when forest soils were incubated with 13CH4 (29), as well as from pure cultures of Methylocaldum (30), providing potential new markers for identifying methanotrophs in environmental samples.

FUTURE OUTLOOK (GENOME AND PROTEOME)

Recently, the first complete genome sequence of a methanotroph, Methylococcus capsulatus Bath, was published (126), and the first draft of the genome sequence of the facultative methanotroph, Methylocella silvestris BL2, has just become available. The genomes of two other methanotrophs, Methylomicrobium album BG8 and Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b, are also being sequenced by JGI (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/sequencing/why/CSP2008/methanotrophs.html). Comparisons of the genome sequences of these representative obligate methanotrophs with the genome sequence of the facultative methanotroph Methylocella silvestris BL2 and with other obligate and facultative methylotrophs may well reveal the molecular basis for the obligate nature of most extant methanotrophs. Proteomic analyses of regulation of methanotrophy by copper ions (68) and of the outer membrane subproteome (6) in Methylococcus capsulatus Bath have also recently been published. These genomic and proteomic analyses provide a wealth of information for studying the biology of methane oxidation (24, 69) and may provide insights into how methanotrophy is regulated under different environmental conditions. Future studies will undoubtedly use the information from the molecular ecology, genome, and proteome studies to aid in the isolation of new and novel methanotrophs and to reveal new and interesting physiology and biochemistry for this fascinating group of microorganisms.

ADDENDUM

Two recent studies (37a, 99a) report the cultivation and characterization of two new extremely acidophilic methanotrophs from the Verrucomicrobia phylum. Unlike all other methanotrophs characterized previously, these acidophilic methanotrophs do not belong to Proteobacteria and contain three divergent pMMO clusters, indicating an ancient divergence of Verrucomicrobia and Proteobacteria methanotrophs rather than a recent horizontal gene transfer of pMMO. These recent findings, together with the discovery of the facultative methanotroph Methylocella silvestris, reopen the question “What are the taxonomic diversity of methanotrophs and the distribution of methanotrophy in the microbial world?,” and this question warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgments

Work in our laboratories has been funded by the NERC (United Kingdom), the BBSRC (United Kingdom), The Royal Society (United Kingdom), FWF (Austria), and the EU.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali, H., J. Scanlan, M. G. Dumont, and J. C. Murrell. 2006. Duplication of the mmoX gene in Methylosinus sporium: cloning, sequencing, and mutational analysis. Microbiology 152:2931-2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auman, A. J., and M. E. Lidstrom. 2002. Analysis of sMMO-containing type I methanotrophs in Lake Washington sediment. Environ. Microbiol. 4:517-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auman, A. J., C. C. Speake, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2001. nifH sequences and nitrogen fixation in type I and type II methanotrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4009-4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auman, A. J., S. Stolyar, A. M. Costello, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2000. Molecular characterization of methanotrophic isolates from freshwater lake sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5259-5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker, P. W., H. Futamata, S. Harayama, and K. Watanabe. 2001. Molecular diversity of pMMO and sMMO in a TCE-contaminated aquifer during bioremediation. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 38:161-167. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berven, F. D., O. S. Karlsen, A. H. Straume, K. Flikka, J. C. Murrell, A. Fjellbirkeland, J. R. Lillehaug, I. Eidhammer, and H. B. Jensen. 2006. Analysing the outer membrane subproteome of Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) using proteomics and novel biocomputing tools. Arch. Microbiol. 184:362-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodelier, P. L. E., M. Meima-Franke, G. Zwart, and H. J. Laanbroek. 2005. New DGGE strategies for the analyses of methanotrophic microbial communities using different combinations of existing 16S rRNA-based primers. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 52:163-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodrossy, L., and A. Sessitsch. 2004. Oligonucleotide microarrays in microbial diagnostics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:245-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodrossy, L., N. Stralis-Pavese, M. Konrad-Köszler, A. Weilharter, T. G. Reichenauer, D. Schöfer, and A. Sessitsch. 2006. mRNA-based parallel detection of active methanotroph populations by use of a diagnostic microarray. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1672-1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodrossy, L., N. Stralis-Pavese, J. C. Murrell, S. Radajewski, A. Weilharter, and A. Sessitsch. 2003. Development and validation of a diagnostic microbial microarray for methanotrophs. Environ. Microbiol. 5:566-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boetius, A., K. Ravenschlag, C. J. Schubert, D. Rickert, F. Widdel, A. Gieseke, R. Amann, and B. B. Jørgensen. 2000. A marine microbial consortium apparently mediating anaerobic oxidation of methane. Nature 407:623-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borjesson, G., I. Sundh, A. Tunlid, A. Frostegard, and B. H. Svensson. 1998. Microbial oxidation of CH4 at high partial pressures in an organic landfill cover soil under different moisture regimes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 26:207-217. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boschker, H. T. S., S. C. Nold, P. Wellsbury, D. Bos, W. de Graaf, R. Pel, R. J. Parkes, and T. E. Cappenberg. 1998. Direct linking of microbial populations to specific biogeochemical processes by 13C-labeling of biomarkers. Nature 392:801-805. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosse, U., and P. Frenzel. 1997. Activity and distribution of methane-oxidizing bacteria in flooded rice soil microcosms and in rice plants (Oryza sativa). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1199-1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourne, D. G., I. R. McDonald, and J. C. Murrell. 2001. Comparison of pmoA PCR primer sets as tools for investigating methanotroph diversity in three Danish soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3802-3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brusseau, G. A., E. S. Bulygina, and R. S. Hanson. 1994. Phylogenetic analysis and development of probes for differentiating methylotrophic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:626-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bull, I. D., N. R. Parekh, G. H. Hall, P. Ineson, and R. P. Evershed. 2000. Detection and classification of atmospheric methane oxidizing bacteria in soil. Nature 405:175-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bussmann, I., M. Pester, A. Brune, and B. Schink. 2004. Preferential cultivation of type II methanotrophic bacteria from littoral sediments (Lake Constance). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 47:179-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cardy, D. L. N., V. Laidler, G. P. C. Salmond, and J. C. Murrell. 1991. Molecular analysis of the methane monooxygenase (MMO) gene cluster of Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Mol. Microbiol. 5:335-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cébron, A., L. Bodrossy, N. Stralis-Pavese, A. C. Singer, I. P. Thompson, J. I. Prosser, and J. C. Murrell. 2007. Nutrient amendments in soil DNA stable isotope probing experiments reduce the observed methanotroph diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:798-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen, Y., M. G. Dumont, A. Cébron, and J. C. Murrell. 2007. Identification of active methanotrophs in a landfill cover soil through detection of expression of 16S rRNA and functional genes. Environ. Microbiol. 9:2855-2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen, Y., M. G. Dumont, N. P. McNamara, P. M. Chamberlain, L. Bodrossy, N. Stralis-Pavese, and J. C. Murrell. 2008. Diversity of active methanotrophic community in acidic peatland as assessed by mRNA and SIP-PLFA analyses. Environ. Microbiol. 10:446-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng, Y. S., J. L. Halsey, K. A. Fode, C. C. Remsen, and M. L. P. Collins. 1999. Detection of methanotrophs in groundwater by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:648-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chistoserdova, L., J. A. Vorholt, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2005. A genomic view of methane oxidation by aerobic bacteria and anaerobic archaea. Genome Biol. 6:208.1-208.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conrad, R. 1996. Soil microorganisms as controllers of atmospheric trace gases (H2, CO, CH4, OCS, N2O, and NO). Microbiol. Rev. 60:609-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costello, A. M., A. J. Auman, J. L. Macalady, K. M. Scow, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2002. Estimation of methanotroph abundance in a freshwater lake sediment. Environ. Microbiol. 4:443-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costello, A. M., and M. E. Lidstrom. 1999. Molecular characterization of functional and phylogenetic genes from natural populations of methanotrophs in lake sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5066-5074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crossman, Z. M., F. Abraham, and R. P. Evershed. 2004. Stable isotope pulse-chasing and compound specific stable carbon isotope analysis of phospholipid fatty acids to assess methane oxidizing bacterial populations in landfill cover soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38:1359-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crossman, Z. M., N. McNamara, N. R. Parekh, P. Ineson, and R. P. Evershed. 2001. A new method for identifying the origins of simple and complex hopanoids in sedimentary materials using stable isotope labeling with 13CH4 and compound specific stable isotope analyses. Organic Geochem. 32:359-364. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cvejic, J. H., L. Bodrossy, K. L. Kovács, and M. Rohmer. 2000. Bacterial triterpenoids of the hopane series from the methanotrophic bacteria Methylocaldum spp.: phylogenetic implications and first evidence for an unsaturated aminobecteriopanepolyol. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 182:361-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dedysh, S. N., S. E. Belova, P. L. E. Bodelier, K. V. Smirnova, V. N. Khmelenina, A. Chidthaisong, Y. A. Trotsenko, W. Liesack, and P. F. Dunfield. 2007. Methylocystis heyeri sp. nov., a novel type II methanotrophic bacterium possessing ‘signature’ fatty acids of type I methanotrophs. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57:472-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dedysh, S. N., M. Derakshani, and W. Liesack. 2001. Detection and enumeration of methanotrophs in acidic Sphagnum peat by 16S rRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization, including the use of newly developed oligonucleotide probes for Methylocella palustris. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4850-4857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dedysh, S. N., P. F. Dunfield, M. Derakshani, S. Stubner, J. Heyer, and W. Liesack. 2003. Differential detection of type II methanotrophic bacteria in acidic peatlands using newly developed 16S rRNA-targeted fluorescent oligonucleotide probes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 43:299-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dedysh, S. N., P. Ricke, and W. Liesack. 2004. NifH and NifD phylogenies: an evolutionary basis for understanding nitrogen fixation capabilities of methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol. 150:1301-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dumont, M. G., and J. C. Murrell. 2005. Stable isotope probing: linking microbial identity to function. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:499-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dumont, M. G., S. M. Radajewski, C. B. Miguez, I. R. McDonald, and J. C. Murrell. 2006. Identification of a complete methane monooxygenase operon from soil by combining stable isotope probing and metagenomic analysis. Environ. Microbiol. 8:1240-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunfield, P. F., W. Liesack, T. Henckel, R. Knowles, and R. Conrad. 1999. High-affinity methane oxidation by a soil enrichment culture containing a type II methanotroph. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1009-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37a.Dunfield, P. F., A. Yuryev, P. Senin, A. V. Smirnova, M. B. Stott, S. Hou, B. Ly, J. H. Saw, Z. Zhou, Y. Ren, J. Wang, B. W. Mountain, M. A. Crowe, T. M. Weatherby, P. L. Bodelier, W. Liesack, L. Feng, L. Wang, and M. Alam. 2007. Methane oxidation by an extremely acidophilic bacterium of the phylum Verrucomicrobia. Nature 450:879-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eller, G., P. Deines, J. Grey, H. H. Richnow, and M. Kruger. 2005. Methane cycling in lake sediments and its influence on chironomid larval δ13C. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 54:339-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eller, G., S. Stubner, and P. Frenzel. 2001. Group-specific 16S rRNA targeted probes for the detection of type I and type II methanotrophs by fluorescence in situ hybridisation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 198:91-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evershed, R. P., Z. M. Crossman, I. D. Bull., H. Mottram, J. A. J. Dungait, P. J. Maxfield, and E. L. Brennand. 2006. C-13-Labelling of lipids to investigate microbial communities in the environment. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17:72-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fang, J. S., M. J. Barcelona, and J. D. Semrau. 2000. Characterization of methanotrophic bacteria on the basis of intact phospholipid profiles. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 189:67-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fjellbirkeland, A., V. Torsvik, and L. Ovreas. 2001. Methanotrophic diversity in an agricultural soil as evaluated by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis profiles of pmoA, mxaF, and 16S rDNA sequences. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 79:209-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friedrich, M. W. 2006. Stable-isotope probing of DNA: insights into the function of uncultivated microorganisms from isotopically labeled metagenomes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17:59-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fuse, H., M. Ohta, O. Takimura, K. Murakami, H. Inoue, Y. Yamaoka, J. M. Oclarit, and T. Omori. 1998. Oxidation of trichloroethylene and dimethyl sulfide by a marine Methylomicrobium strain containing soluble methane monooxygenase. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 62:1925-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilbert, B., I. R. McDonald, R. Finch, G. P. Stafford, A. K. Nielsen, and J. C. Murrell. 2000. Molecular analysis of the pmo (particulate methane monooxygenase) operons from two type II methanotrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:966-975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grosse, S., L. Laramee, K. D. Wendlandt, I. R. McDonald, C. B. Miguez, and H. P. Kleber. 1999. Purification and characterisation of the soluble methane monooxygenase of the type II methanotrophic bacterium Methylocystis sp. WI14. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3929-3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guckert, J. B., D. B. Ringelberg, D. C. White, R. S. Hanson, and B. J. Bratina. 1991. Membrane fatty acids as phenotypic markers in the polyphasic taxonomy of methylotrophs within the Proteobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:2631-2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gulledge, J., A. Ahmad, P. A. Steudler, W. J. Pomerantz, and C. M. Cavanaugh. 2001. Family- and genus-level 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for ecological studies of methanotrophic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4726-4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hakemian, A. S., and A. C. Rosenzweig. 2007. The biochemistry of methane oxidation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76:223-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halet, D., N. Boon, and W. Verstraete. 2006. Community dynamics of methanotrophic bacteria during composting of organic matter. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 101:297-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han, J. I., and J. D. Semrau. 2004. Quantification of gene expression in methanotrophs by competitive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. Environ. Microbiol. 6:388-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanson, R. S., and T. E. Hanson. 1996. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 60:439-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He, Z., T. J. Gentry, C. W. Schadt, L. Wu, J. Liebich, S. C. Chong, Z. Huang, W. Wu, B. Gu, P. Jardine, C. Criddle, and J. Zhou. 2007. GeoChip: a comprehensive microarray for investigating biogeochemical, ecological, and environmental processes. ISME J. 1:67-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Henckel, T., M. Friedrich, and R. Conrad. 1999. Molecular analyses of the methane-oxidizing microbial community in rice field soil by targeting the genes of the 16S rRNA, particulate methane monooxygenase, and methanol dehydrogenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1980-1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henckel, T., U. Jäckel, S. Schnell, and R. Conrad. 2000. Molecular analyses of novel methanotrophic communities in forest soil that oxidize atmospheric methane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1801-1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heyer, J., V. F. Galchenko, and P. F. Dunfield. 2002. Molecular phylogeny of type II methane-oxidizing bacteria isolated from various environments. Microbiology 148:2831-2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holmes, A. J., A. M. Costello, M. E. Lidstrom, and J. C. Murrell. 1995. Evidence that particulate methane monooxygenase and ammonia monooxygenase may be evolutionarily related. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 132:203-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holmes, A. J., N. J. P. Owens, and J. C. Murrell. 1995. Detection of novel marine methanotrophs using phylogenetic and functional gene probes after methane enrichment. Microbiology 141:1947-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holmes, A. J., P. Roslev, I. R. McDonald, N. Iversen, K. Henriksen, and J. C. Murrell. 1999. Characterization of methanotrophic bacterial populations in soils showing atmospheric methane uptake. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3312-3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horz, H. P., A. S. Raghubanshi, J. Heyer, C. Kammann, R. Conrad, and P. F. Dunfield. 2002. Activity and community structure of methane-oxidizing bacteria in a wet meadow soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 41:247-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horz, H. P., V. Rich, S. Avrahami, and B. J. M. Bohannan. 2005. Methane-oxidizing bacteria in a California upland grassland soil: diversity and response to simulated global change. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2642-2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Horz, H. P., M. T. Yimga, and W. Liesack. 2001. Detection of methanotroph diversity on roots of submerged rice plants by molecular retrieval of pmoA, mmoX, mxaF, and 16S rRNA and ribosomal DNA, including pmoA-based terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism profiling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4177-4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hutchens, E., S. Radajewski, M. G. Dumont, I. R. McDonald, and J. C. Murrell. 2004. Analysis of methanotrophic bacteria in Movile Cave by stable-isotope probing. Environ. Microbiol. 6:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iwamoto, T., K. Tani, K. Nakamura, Y. Suzuki, M. Kitagawa, M. Eguchi, and M. Nasu. 2000. Monitoring impact of in situ biostimulation treatment on groundwater bacterial community by DGGE. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 32:129-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jenkins, B. D., G. F. Steward, S. M. Short, B. B. Ward, and J. P. Zehr. 2004. Fingerprinting diazotroph communities in the Chesapeake Bay by using a DNA macroarray. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1767-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalyuzhnaya, M. G., M. E. Lidstrom, and L. Chistoserdova. 2004. Utility of environmental primers targeting ancient enzymes: methylotroph detection in Lake Washington. Microb. Ecol. 48:463-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kalyuzhnaya, M. G., V. A. Makutina, T. G. Rusakova, D. V. Nikitin, V. N. Khmelenina, V. V. Dmitriev, and Y. A. Trotsenko. 2002. Methanotrophic communities in the soils of the Russian Northern Taiga and Subarctic tundra. Mikrobiologiya 71:227-233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kao, W. C., Y. R. Chen, E. C. Yi, H. Lee, Q. Tian, K. M. Wu, S. F. Tsai, S. S. F. Yu, Y. J. Chen, R. Aebersold, and S. I. Chan. 2004. Quantitative proteomic analysis of metabolic regulation by copper ions in Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath). J. Biol. Chem. 279:51554-51560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kelly, D. P., C. Anthony, and J. C. Murrell. 2005. Insights into the obligate methanotroph Methylococcus capsulatus. Trends Microbiol. 13:195-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Knief, C., S. Kolb, P. L. E. Bodelier, A. Lipski, and P. F. Dunfield. 2006. The active methanotrophic community in hydromorphic soils changes in response to changing methane concentration. Environ. Microbiol. 8:321-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Knief, C., A. Lipski, and P. F. Dunfield. 2003. Diversity and activity of methanotrophic bacteria in different upland soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6703-6714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Knief, C., S. Vanitchung, N. W. Harvey, R. Conrad, P. F. Dunfield, and A. Chidthaisong. 2005. Diversity of methanotrophic bacteria in tropical upland soils under different land uses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:3826-3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kolb, S., C. Knief, P. F. Dunfield, and R. Conrad. 2005. Abundance and activity of uncultured methanotrophic bacteria involved in the consumption of atmospheric methane in two forest soils. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1150-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kolb, S., C. Knief, S. Stubner, and R. Conrad. 2003. Quantitative detection of methanotrophs in soil by novel pmoA-targeted real-time PCR assays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2423-2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kopp, D. A., and S. J. Lippard. 2002. Soluble methane monooxygenase: activation of dioxygen and methane. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 6:568-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kubota, K., A. Ohashi, H. Imachi, and H. Harada. 2006. Visualization of mcr mRNA in a methanogen by fluorescence in situ hybridization with an oligonucleotide probe and two-pass tyramide signal amplification (two-pass TSA-FISH). J. Microbiol. Methods 66:521-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lau, E., A. Ahmad, P. A. Steudler, and C. M. Cavanaugh. 2007. Molecular characterization of methanotrophic communities in forest soils that consume atmospheric methane. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 60:490-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lin, J. L., S. B. Joye, J. C. M. Scholten, H. Schäfer, I. R. McDonald, and J. C. Murrell. 2005. Analysis of methane monooxygenase genes in Mono Lake suggests that increased methane oxidation activity may correlate with a change in methanotroph community structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6458-6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lin, J. L., S. Radajewski, B. T. Eshinimaev, Y. A. Trotsenko, I. R. McDonald, and J. C. Murrell. 2004. Molecular diversity of methanotrophs in Transbaikal soda lake sediments and identification of potential active populations by stable isotope probing. Environ. Microbiol. 6:1049-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lueders, T., M. Manefield, and M. W. Friedrich. 2004. Enhanced sensitivity of DNA- and rRNA-based stable isotope probing by fractionation and quantitative analysis of isopycnic centrifugation gradients. Environ. Microbiol. 6:73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lueders, T., B. Wagner, P. Claus, and M. W. Friedrich. 2004. Stable isotope probing of rRNA and DNA reveals a dynamic methylotroph community and trophic interactions with fungi and protozoa in oxic rice field soil. Environ. Microbiol. 6:60-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Manefield, M., A. S. Whiteley, R. I. Griffiths, and M. J. Bailey. 2002. RNA stable isotope probing, a novel means of linking microbial community function to phylogeny. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5367-5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maxfield, P. J., E. R. C. Hornibrook, and R. P. Evershed. 2006. Estimating high-affinity methanotrophic bacterial biomass, growth, and turnover in soil by phospholipid fatty acid 13C labeling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3901-3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McDonald, I. R., G. H. Hall, R. W. Pickup, and J. C. Murrell. 1996. Methane oxidation potential and preliminary-analysis of methanotrophs in blanket bog peat using molecular ecology techniques. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 21:197-211. [Google Scholar]

- 85.McDonald, I. R., E. M. Kenna, and J. C. Murrell. 1995. Detection of methanotrophic bacteria in environmental samples with the PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:116-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McDonald, I. R., C. B. Miguez, G. Rogge, D. Bourque, K. D. Wendlandt, D. Groleau, and J. C. Murrell. 2006. Diversity of soluble methane monooxygenase-containing methanotrophs isolated from polluted environments. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 255:225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McDonald, I. R., and J. C. Murrell. 1997. The methanol dehydrogenase structural gene mxaF and its use as a functional gene probe for methanotrophs and methylotrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3218-3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McDonald, I. R., S. Radajewski, and J. C. Murrell. 2005. Stable isotope probing of nucleic acids in methanotrophs and methylotrophs: a review. Organic Geochem. 36:779-787. [Google Scholar]

- 89.McDonald, I. R., H. Uchiyama, S. Kambe, O. Yagi, and J. C. Murrell. 1997. The soluble methane monooxygenase gene cluster of the trichloroethylene-degrading methanotroph Methylocystis sp. strain M. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1898-1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Merkx, M., and S. J. Lippard. 2002. Why OrfY? Characterization of MmoD, a long overlooked component of the soluble methane monooxygenase from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath). J. Biol. Chem. 277:5858-5865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Miguez, C. B., D. Bourque, J. A. Sealy, C. W. Greer, and D. Groleau. 1997. Detection and isolation of methanotrophic bacteria possessing soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO) genes using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Microb. Ecol. 33:21-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Miller, D. N., J. B. Yavitt, E. L. Madsen, and W. C. Ghiorse. 2004. Methanotrophic activity, abundance, and diversity in forested swamp pools: spatiotemporal dynamics and influences on methane fluxes. Geomicrobiol. J. 21:257-271. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Morris, S. A., S. Radajewski, T. W. Willison, and J. C. Murrell. 2002. Identification of the functionally active methanotroph population in a peat soil microcosm by stable-isotope probing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1446-1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Murrell, J. C., I. R. McDonald, and B. Gilbert. 2000. Regulation of expression of methane monooxygenases by copper ions. Trends Microbiol. 8:221-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nercessian, O., N. Bienvenu, D. Moreira, D. Prieur, and C. Jeanthon. 2005. Diversity of functional genes of methanogens, methanotrophs, and sulfate reducers in deep-sea hydrothermal environments. Environ. Microbiol. 7:118-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nercessian, O., E. Noyes, M. G. Kalyuzhnaya, M. E. Lidstrom, and L. Chistoserdova. 2005. Bacterial populations active in metabolism of C1 compounds in the sediment of Lake Washington, a freshwater lake. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6885-6899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Neufeld, J. D., Y. Chen, M. G. Dumont, and J. C. Murrell. Marine methylotrophs revealed by stable-isotope probing, multiple displacement amplification and metagenomics. Environ. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 98.Neufeld, J. D., H. Schafer, M. J. Cox, R. Boden, I. R. McDonald, and J. C. Murrell. 2007. Stable-isotope probing implicates Methylophaga spp. and novel Gammaproteobacteria in marine methanol and methylamine metabolism. ISME J. 1:480-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pacheco-Oliver, M., I. R. McDonald, D. Groleau, J. C. Murrell, and C. B. Miguez. 2002. Detection of methanotrophs with highly divergent pmoA genes from Arctic soils. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 209:313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99a.Pol, A., K. Heijmans, H. R. Harhangi, D. Tedesco, M. S. Jetten, and H. J. Op den Camp. 2007. Methanotrophy below pH 1 by a new Verrucomicro-bia species. Nature 450:874-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Purkhold, U., A. Pommerening-Roser, S. Juretschko, M. C. Schmid, H. P. Koops, and M. Wagner. 2000. Phylogeny of all recognized species of ammonia oxidizers based on comparative 16S rRNA and amoA sequence analysis: implications for molecular diversity surveys. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5368-5382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Radajewski, S., P. Ineson, N. R. Parekh, and J. C. Murrell. 2000. Stable-isotope probing as a tool in microbial ecology. Nature 403:646-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Radajewski, S., I. R. McDonald, and J. C. Murrell. 2003. Stable-isotope probing of nucleic acids: a window to the function of uncultured microorganisms. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 14:296-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Radajewski, S., G. Webster, D. S. Reay, S. A. Morris, P. Ineson, D. B. Nedwell, J. I. Prosser, and J. C. Murrell. 2002. Identification of active methylotroph populations in an acidic forest soil by stable-isotope probing. Microbiology 148:2331-2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Raghoebarsing, A. A., A. Pol, K. T. van de Pas-Schoonen, A. J. P. Smolders, K. F. Ettwig, W. I. C. Rijpstra, S. Schouten, J. S. S. Damsté, H. J. M. Op den Camp, M. S. M. Jetten, and M. Strous. 2006. A microbial consortium couples anaerobic methane oxidation to denitrification. Nature 440:918-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ricke, P., S. Kolb, and G. Braker. 2005. Application of a newly developed ARB software-integrated tool for in silico terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis reveals the dominance of a novel pmoA cluster in a forest soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1671-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rotthauwe, J. H., K. P. Witzel, and W. Liesack. 1997. The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4704-4712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Semrau, J. D., A. Chistoserdov, J. Lebron, A. M. Costello, J. Davagnino, E. M. Kenna, A. J. Holmes, R. Finch, J. C. Murrell, and M. E. Lidstrom. 1995. Particulate methane monooxygenase genes in methanotrophs. J. Bacteriol. 177:3071-3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shigematsu, T., S. Hanada, M. Eguchi, Y. Kamagata, T. Kanagawa, and R. Kurane. 1999. Soluble methane monooxygenase gene clusters from trichloroethylene-degrading Methylomonas sp. strains and detection of methanotrophs during in situ bioremediation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5198-5206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Smith, K. S., A. M. Costello, and M. E. Lidstrom. 1997. Methane and trichloroethylene oxidation by an estuarine methanotroph, Methylobacter sp. strain BB5.1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4617-4620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Stafford, G. P., J. Scanlan, I. R. McDonald, and J. C. Murrell. 2003. rpoN, mmoR, and mmoG, genes involved in regulating the expression of soluble methane monooxygenase in Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Microbiology 149:1771-1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stainthorpe, A. C., V. Lees, G. P. C. Salmond, H. Dalton, and J. C. Murrell. 1990. The methane monooxygenase gene cluster of Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath). Gene 91:27-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Steinkamp, R., W. Zimmer, and H. Papen. 2001. Improved method for detection of methanotrophic bacteria in forest soils by PCR. Curr. Microbiol. 42:316-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Stoecker, K., B. Bendinger, B. Schöning, P. H. Nielsen, J. L. Nielsen, C. Baranyi, E. R. Toenschoff, H. Daims, and M. Wagner. 2006. Cohn's Crenothrix is a filamentous methane oxidizer with and unusual methane monooxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:2363-2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Stolyar, S., A. M. Costello, T. L. Peeples, and M. E. Lidstrom. 1999. Role of multiple gene copies in particulate methane monooxygenase activity in the methane-oxidizing bacterium Methylococcus capsulatus Bath. Microbiol. 145:1235-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Stralis-Pavese, N., L. Bodrossy, T. G. Reichenauer, A. Weilharter, and A. Sessitsch. 2006. 16S rRNA based T-RFLP analysis of methane oxidizing bacteria: assessment, critical evaluation of methodology performance, and application for landfill site cover soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 31:251-266. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Stralis-Pavese, N., A. Sessitsch, A. Weilharter, T. Reichenauer, J. Riesing, J. Csontos, J. C. Murrell, and L. Bodrossy. 2004. Optimization of diagnostic microarray for application in analysing landfill methanotroph communities under different plant covers. Environ. Microbiol. 6:347-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sundh, I., P. Borga, M. Nilsson, and B. H. Svensson. 1995. Estimation of cell numbers of methanotrophic bacteria in boreal peatlands based on analysis of specific phospholipid fatty acids. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 18:103-112. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sundh, I., G. Börjesson, and A. Tunlid. 2000. Methane oxidation and phospholipid fatty acid composition in a podzolic soil profile. Soil Biol. Biochem. 32:1025-1028. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Takeuchi, M., K. Nanba, H. Iwamoto, H. Nirei, T. Kusuda, O. Kazaoka, and K. Furuya. 2001. Distribution of methanotrophs in trichloroethylene-contaminated aquifers in a natural gas field. Geomicrobiol. J. 18:387-399. [Google Scholar]