Abstract

Nanoarchaeum equitans and Ignicoccus hospitalis represent a unique, intimate association of two archaea. Both form a stable coculture which is mandatory for N. equitans but not for the host I. hospitalis. Here, we investigated interactions and mutual influence between these microorganisms. Fermentation studies revealed that during exponential growth only about 25% of I. hospitalis cells are occupied by N. equitans cells (one to three cells). The latter strongly proliferate in the stationary phase of I. hospitalis, until 80 to 90% of the I. hospitalis cells carry around 10 N. equitans cells. Furthermore, the expulsion of H2S, the major metabolic end product of I. hospitalis, by strong gas stripping yields huge amounts of free N. equitans cells. N. equitans had no influence on the doubling times, final cell concentrations, and growth temperature, pH, or salt concentration ranges or optima of I. hospitalis. However, isolation studies using optical tweezers revealed that infection with N. equitans inhibited the proliferation of individual I. hospitalis cells. This inhibition might be caused by deprivation of the host of cell components like amino acids, as demonstrated by 13C-labeling studies. The strong dependence of N. equitans on I. hospitalis was affirmed by live-dead staining and electron microscopic analyses, which indicated a tight physiological and structural connection between the two microorganisms. No alternative hosts, including other Ignicoccus species, were accepted by N. equitans. In summary, the data show a highly specialized association of N. equitans and I. hospitalis which so far cannot be assigned to a classical symbiosis, commensalism, or parasitism.

The concept of symbiosis originally encompassed all long-term relationships of different organisms in close proximity (28). Those associations could be mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasitic. However, for many types of interactions between organisms, assignment to these simple categories is not possible. Symbiotic systems are often very difficult to cultivate in the laboratory and therefore hard to analyze (2). In addition, interactions between many organisms turned out to be dynamic and to change among mutualism, commensalism, and parasitism (25).

The first and so far only known intimate association of two archaea was described in 2002 by Huber et al. (12). It consists of the designated “host” Ignicoccus hospitalis, a member of the crenarchaeal order Desulfurococcales, and the “symbiont” Nanoarchaeum equitans. I. hospitalis is an anaerobic, hyperthermophilic coccus growing strictly chemolithoautotrophically by reduction of elemental sulfur with molecular hydrogen as an electron donor (24) and fixation of CO2 via a novel CO2 fixation pathway (15). Like cells of the other described Ignicoccus species, I. hospitalis cells exhibit a unique morphology; they lack an S layer and are the only archaea which are surrounded by an outer membrane exhibiting a unique protein and lipid composition (4, 16, 22, 26). N. equitans was identified as the first representative of a novel archaeal kingdom, the Nanoarchaeota (12, 13, 31). However, the exact branching point within phylogenetic trees of this organism is dependent on the molecule investigated and an object of ongoing scientific discussion (3, 5, 6). For clarification, the identification and characterization of further members of this widely distributed group (11, 20) might be crucial. N. equitans cells are tiny cocci with a diameter of 350 to 500 nm attached to the surface of I. hospitalis (12). Various attempts to cultivate N. equitans in the absence of its host failed (13). With about 490 kb, N. equitans has one of the smallest genomes known so far, lacking nearly all known genes for lipid, cofactor, amino acid, or nucleotide biosynthesis (31). Lipid analyses of N. equitans and I. hospitalis revealed that N. equitans derives all of its membrane lipids from its host (16). However, still very little is known about its physiology and the interaction with I. hospitalis.

In this study, we investigated the growth characteristics, interactions and mutual influence of N. equitans and I. hospitalis. The data shed light on a unique system which combines characteristics of symbiosis, commensalisms, and parasitism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

I. hospitalis strain KIN4/IT, I. islandicus strain Kol8T, I. pacificus strain LPC33T, Pyrodictium occultum strain PL19T, Pyrococcus furiosus strain F1T, and the coculture of I. hospitalis and N. equitans were routinely grown at 90°C in 120-ml serum bottles containing 20 ml of synthetic-seawater medium (0.5× SME medium [13] pressurized with H2-CO2 [80/20, vol/vol], 3 × 105 Pa). Pyrobaculum arsenaticum strain PZ6T and Thermoproteus strain CU1 were cultivated at 90°C in 0.37× SME medium pressurized with H2-CO2 (80/20 [vol/vol], 3 × 105 Pa). All strains were obtained from the culture collection of the Lehrstuhl für Mikrobiologie, University of Regensburg.

Physiological tests for I. hospitalis and the coculture.

Determination of growth at different NaCl concentrations was conducted in standard 0.5× SME medium with various NaCl concentrations (0 to 7% NaCl, 0.2% [wt/vol] steps). Different pH values (pHs 3.5 to 8, in 0.5-U steps) were adjusted with H2SO4 or NaOH in 0.5× SME medium without NaHCO3 to avoid its buffering effect. The pH was checked before and after incubation to ensure that it remained unchanged during incubation. Temperature ranges were determined by cultivating the cells at 60 to 100°C (5°C steps).

Fermentation conditions.

Standard fermentation assays for the pure culture of I. hospitalis and the coculture of N. equitans and I. hospitalis were conducted in 50-liter enamel-protected fermentors with a 1-liter preculture for inoculation (concentrations, 5 × 106 to 107 I. hospitalis cells ml−1 and about 2 × 106 to 5 × 106 N. equitans cells ml−1) under the culture conditions described above. The coculture was purged with H2-CO2 (80/20 [vol/vol]) at a flow rate of 10 liters min−1 after the Ignicoccus cells had reached a density of about 106 cells ml−1.

Light microscopy.

Cells were routinely observed with an Olympus BX60 phase-contrast microscope with an oil immersion objective, UPlanF1 100/1.3, and epifluorescence equipment. Growth of I. hospitalis was monitored by direct cell counting using a Thoma chamber (depth, 0.02 mm). Due to the small cell diameter of N. equitans cells, their growth was monitored by counting the N. equitans cells attached to 50 I. hospitalis cells, as well as the free N. equitans cells compared to the I. hospitalis cells at a magnification of ×1,000. Live-dead staining was performed by using BacLight (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands). Four-microliter culture samples were incubated with 1 μl 1:10-diluted BacLight reagent for 5 min at room temperature in the dark. The BacLight reagent employs two dyes which stain nucleic acids, i.e., SYTO 9 and propidium iodide. SYTO 9 (green fluorescent) penetrates intact and damaged (bacterial and archaeal) cell membranes. In contrast, propidium iodide (reducing the green SYTO 9 fluorescence to red) only penetrates damaged cell membranes. Thus, under UV light (excitation, 360 to 370 nm), cells with an intact membrane (living cells) exhibit a green color whereas cells with a damaged membrane (dead cells) stain red (19, 30).

Optical-tweezer experiments.

From a coculture in the late exponential growth phase, single cells of I. hospitalis occupied by 0 to 10 N. equitans cells were isolated by the optical-tweezer technique (14), transferred into fresh medium, and cultivated for 4 weeks as described above. The culture vessels were checked for microbial growth by microscopy every 2 days.

Electron microscopy.

Following cultivation in 0.5× SME medium inside the lumen of cellulose capillaries, cells of I. hospitalis with N. equitans were processed by high-pressure freezing, freeze substitution, and embedding in Epon as previously described (4, 26, 27). Digital electron micrographs of ultrathin sections, contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, were recorded using a slow-scan charge-coupled device camera (Tietz, Gauting, Germany) mounted on a CM12 transmission electron microscope (FEI Co., Eindhoven, The Netherlands), which was operated at 120,000 eV.

Production of 13C-labeled cell masses.

I. hospitalis cells were cultivated under autotrophic growth conditions in a 300-liter enamel-protected fermentor in the presence of 0.5 mM [1-13C]acetate (Euriso-Top, Gif-sur-Yvette Cedex, France) (15). To avoid loss of acetate, the fermentation was performed without gas stripping. Cells were harvested at the end of the exponential growth phase of I. hospitalis to obtain distinct labeling patterns. This labeling experiment was repeated with the coculture of I. hospitalis and N. equitans, with the following modifications. To obtain maximal cell masses of N. equitans, the fermentor was gassed for 10 h after inoculation (10 liters min−1) and the cells were harvested in the stationary growth phase of I. hospitalis.

Separation of free N. equitans cells.

Free N. equitans cells were separated from I. hospitalis cells from the coculture by differential centrifugation (12).

Fractionation of cell material and separation of amino acids.

Cells (wet weights: I. hospitalis, 3 g; N. equitans, 1 g) were fractionated, and isolated proteins were hydrolyzed as described by Jahn et al. (15). Amino acids were isolated by chromatographic procedures published earlier (9).

NMR spectroscopy.

1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded at 500.13 and 125.76 MHz, respectively, with a DRX500 spectrometer (Bruker Biospin, Rheinstetten, Germany) as previously described (8, 15). Tyr and Asp were dissolved in D2O containing 0.1 M NaOD (pH 13); the other amino acids were dissolved in D2O containing 0.1 M DCl (pH 1). 13C enrichments were determined for individual positions by quantitative NMR spectroscopy (8).

Cross infection experiments.

To test the possibility of serving as alternative host organisms for N. equitans, I. islandicus strain Kol8T, I. pacificus strain LPC33T, Pyrodictium occultum strain PL19T, and Pyrococcus furiosus strain F1T were mixed with the coculture of I. hospitalis and N. equitans in 0.5× SME medium (13) pressurized with H2-CO2 (80/20 [vol/vol], 3 × 105 Pa). Pyrobaculum arsenaticum strain PZ6T and Thermoproteus strain CU1, which do not grow in 0.5× SME medium, were cocultivated with I. hospitalis and N. equitans in 0.37× SME medium. Several dilutions were used for each of the possible host organism to obtain cocultures with various proportions of I. hospitalis (with attached N. equitans cells) and the applied archaeal species. All cross infection experiments were carried out at 90°C.

Alternatively, infection experiments were carried out with purified N. equitans cells obtained from fermentations or from serum bottles. Such N. equitans cells were purified by separation from I. hospitalis cells by filtration (pore size, 0.4 μm), by Percoll or sucrose density gradients, or by differential centrifugation. To enforce infectiousness of the purified N. equitans cells, the medium with the tested host organism was supplemented with, e.g., 0.1% yeast extract, peptone, meat extract, I. hospitalis extract, supernatant of a grown I. hospitalis culture, 1 to 100 mM magnesium ions, or 0.25 to 5% carboxymethyl cellulose (to enhance the viscosity of the medium). Alternatively, the addition of the purified N. equitans cells to the potential hosts occurred in different growth phases of these organisms and with different concentrations of host and N. equitans cells.

16S rRNA gene sequence analysis.

DNA was prepared as previously described (21). Nearly complete 16S rRNA gene sequences were amplified by PCR using a standard protocol (7) and the following primer combinations. To screen for the presence of N. equitans, primer combinations 7mcF-1511mcR, 7mcF-1116mcR, 518mcF-1511mcR, and 518mcF-1116mcR were used (11). The archaeon-specific primer combination 8aF-1512uR (7) served as a positive control for these assays and for obtaining the 16S rRNA gene sequences of Ignicoccus subcultures. The PCR products were sequenced and compared to the 16S rRNA gene sequences of N. equitans or the three Ignicoccus species, respectively.

RESULTS

Effects of pH, temperature, and salt concentration.

The temperature, pH, and salt concentration ranges and optima for the growth of I. hospitalis were determined (Table 1). No differences were found between cells grown in coculture with N. equitans and those cultivated in pure culture. Under optimal growth conditions (90°C, pH 5.5 to 6.0, 1.4% NaCl), I. hospitalis reached maximum concentrations of about 1 × 107 to 3 × 107 cells ml−1 and shortest doubling times of 50 to 60 min with or without N. equitans. Quite similar growth ranges (and optima) were obtained for N. equitans (Table 1), although for pH and salt tolerance smaller growth ranges occurred. Since N. equitans is strictly dependent on growing I. hospitalis cells, the possibility of an extended temperature range for N. equitans cannot be excluded.

TABLE 1.

Ranges (optima) of temperature, pH, and salt concentration for I. hospitalis (24) and the coculture of I. hospitalis and N. equitans

| Cells | Temp (°C) | pH | NaCl concn (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. hospitalis | 75-98 (90) | 4.5-7.5 (5.5) | 0.2-5.5 (1.4) |

| Coculture | |||

| I. hospitalis host | 75-98 (90) | 4.5-7.5 (5.5) | 0.2-5.5 (1.4) |

| N. equitans | 75-98 (85-90) | 5-6.5 (5.5) | 0.9-3.5 (1.4) |

Growth characteristics of the coculture of I. hospitalis and N. equitans under standard cultivation conditions in fermentors.

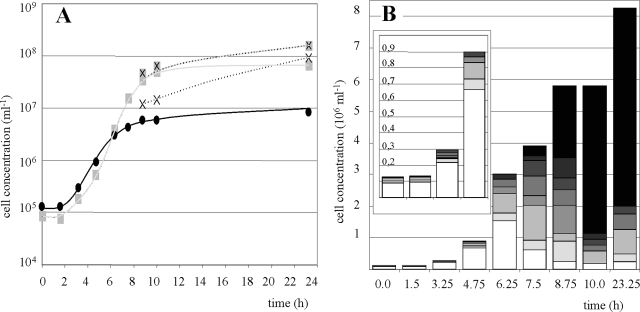

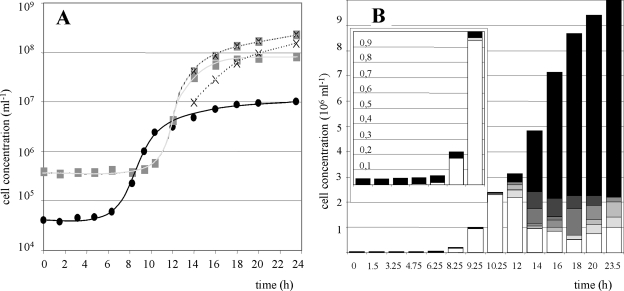

Usually, the preculture for growth experiments in 50-liter fermentors consisted of about 5 × 106 I. hospitalis cells ml−1 with 20 to 40% of these cells being occupied by N. equitans (average, two to three N. equitans cells per occupied I. hospitalis cell). At a density of about 106 I. hospitalis cells ml−1, usually after 8 h of incubation, a gassing rate of 10 liters min−1 H2-CO2 (80/20 [vol/vol]) was applied. Figure 1A shows the growth curves of the I. hospitalis cells, as well as the numbers of attached, free, and total N. equitans cells. Typically, a lag phase of about 90 min occurred for both organisms. In the exponential growth phase, only a minor portion of the I. hospitalis cells (20 to 30%) was occupied by N. equitans (one to three N. equitans cells per I. hospitalis cell, Fig. 1B, 0 to 4.75 h). At concentrations of 2 × 106 to 5 × 106 cells ml−1, I. hospitalis slowly transited into the stationary growth phase. Interestingly, N. equitans showed different growth characteristics. During the exponential growth of I. hospitalis, the growth curve of N. equitans paralleled that of its host. When I. hospitalis transited into the stationary growth phase, N. equitans exhibited increased cell proliferation (doubling time, 45 min) for a further 4 h. As a consequence, the number of N. equitans cells per occupied I. hospitalis cell, as well as the number of occupied I. hospitalis cells in general, significantly increased (Fig. 1B, 6.25 to 8.75 h). At the end of the stationary growth phase, more than 80% of the I. hospitalis cells were covered with at least 10 N. equitans cells (Fig. 1B, 10 and 32.25 h). In addition, the strong gas stripping yielded large amounts of free N. equitans cells emerging in the stationary growth phase of I. hospitalis. The number of attached N. equitans cells did not decrease during the formation of the free cells, resulting in a significantly increased total number of N. equitans cells. Finally, attached N. equitans cells reached a concentration of about 108 cells ml−1 and free N. equitans cells reached a concentration of about 1 × 108 to 2.5 × 108 cells ml−1.

FIG. 1.

Growth of the coculture in the fermentor. In the preculture, around 30% of the I. hospitalis cells were occupied by N. equitans cells (two to four per Ignicoccus cell). (A) Growth curves. I. hospitalis cells, •; total N. equitans cells, shaded ×; attached N. equitans cells, plain shaded square; free N. equitans cells, unshaded ×. (B) Numbers of N. equitans cells (ranging from 0 to 10) attached to cells of I. hospitalis are represented by no shading (n = 0) increasing to the darkest shading (n = 10). The insert is an enlarged view of the cell concentrations within the first 5 h after inoculation.

Influence of the gassing rate on the occurrence of free N. equitans cells.

In contrast to the standard cultivation experiment (10 liters min−1 H2-CO2; 80/20 [vol/vol]), a reduced gassing rate of only 1 liter min−1 H2-CO2 (80/20 [vol/vol]) resulted in a 10-fold smaller amount of free N. equitans cells while the concentration of I. hospitalis cells and attached N. equitans cells remained unchanged. Detachment of N. equitans cells from their host cells due to turbulence alone appears to be insufficient to explain the large amounts of free N. equitans cells at high gassing rates. An explanation might be the increased availability of molecular hydrogen or CO2. To test this assumption, the concentrations of both gases were reduced during gas stripping while simultaneously the amount of N2 was increased. Finally, the fermentors were gassed with a mixture of N2-H2-CO2 (95/3/2 [vol/vol]) with high gassing rates (10 liters min−1) resulting in an identical CO2 supply and an even lower hydrogen supply, compared to the low gassing rates (1 liter min−1) obtained with H2-CO2 (80/20 [vol/vol]). Interestingly, the same amounts of free N. equitans cells were obtained as in the cultivations with high H2-CO2 gassing rates (80/20 [vol/vol], 10 liters min−1). Furthermore, no effects on the growth rates and final yields of I. hospitalis cells and attached N. equitans cells were detectable for all of the variations of gassing rates and gas compositions applied in these experiments. This result demonstrates that an excess supply of H2 or CO2 does not cause an increased amount of free N. equitans cells. In contrast, it strongly indicates that the removal of H2S, the major metabolic end product of I. hospitalis, gives rise to this enhanced proliferation.

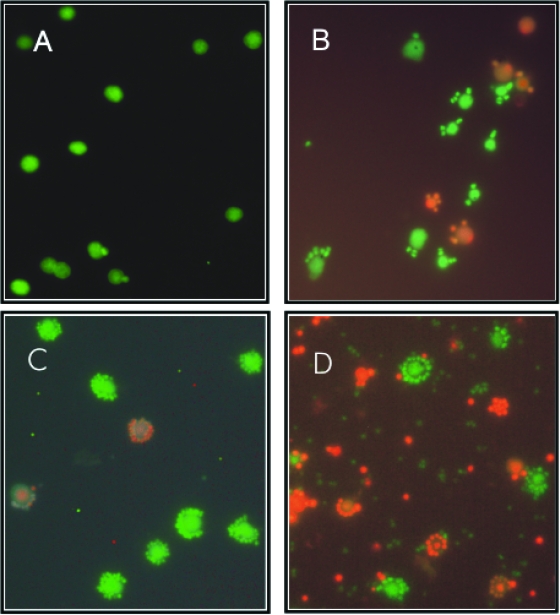

Ratio of dead to living I. hospitalis and N. equitans cells during the fermentation process.

As expected, during the exponential growth phase of I. hospitalis, the amount of living (green) cells was at least 10 times larger than the amount of dead (red) cells (Fig. 2A). After I. hospitalis entered the stationary growth phase (Fig. 2B), the number of living cells slowly began to decrease. However, cell proliferation of N. equitans continued and about 3 h later, nearly all of the I. hospitalis cells were densely covered with N. equitans cells (Fig. 2C). At the end of the stationary growth phase of I. hospitalis, a ratio of living to dead cells of about 1:1 could be seen (Fig. 2D). To our surprise, N. equitans cells attached to an I. hospitalis cell always showed the same BacLight staining as their host cell (Fig. 2A to D), demonstrating again a strong dependence and interaction of the two partners. About 40 to 60% of the free N. equitans cells stained green, suggesting that they do not immediately lose their viability after detaching from the host cells. Further experiments with I. hospitalis grown in pure culture revealed that, at all phases of growth the ratios of living to dead cells were identical with I. hospitalis grown in the coculture with N. equitans (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Epifluorescence microphotographs of the coculture at different growth phases after staining with BacLight. Dead cells stained red, and living cells stained green. (A) At 3.25 h after inoculation, exponential growth phase. (B) At 7.5 h after inoculation, transition into the stationary phase. (C) At 10 h after inoculation, stationary phase. (D) At 23 h after inoculation, stationary phase.

Inhibiting effects of N. equitans on I. hospitalis. (i) Fermentation experiments.

In contrast to standard fermentation experiments, cultivations were carried out with atypical precultures in which the majority (more than 90%) of the I. hospitalis cells was occupied by at least 10 N. equitans cells. This resulted in significant differences in the growth curves (Fig. 3A and B). The lag phase of I. hospitalis seemed to be extended (6 h instead of 1.5 h in the standard cultivation experiment). However, Fig. 3B demonstrates that this effect was caused by the inability of occupied I. hospitalis cells to divide; only I. hospitalis cells without N. equitans cells proliferated. Simultaneously, the number of highly occupied I. hospitalis cells remained unchanged until 10.25 h after inoculation. Since in the beginning the number of nonoccupied I. hospitalis cells was too low to have an apparent influence on the total number of I. hospitalis cells, this gave the impression of an extended lag phase. No actual differences in the doubling time for dividing I. hospitalis cells compared to the standard cultivation could be detected.

FIG. 3.

Growth of the coculture in the fermentor. In the preculture, nearly all I. hospitalis cells were occupied by at least 10 N. equitans cells. (A) Growth curves. I. hospitalis cells, •; total N. equitans cells, shaded ×; attached N. equitans cells, plain shaded square; free N. equitans cells, unshaded ×. (B) Numbers of N. equitans cells (ranging from 0 to 10) attached to cells of I. hospitalis are represented by no shading (n = 0) increasing to the darkest shading (n = 10). The insert is an enlarged view of the cell concentrations within the first 10 h after inoculation.

In contrast, N. equitans cells exhibited a true extended lag phase. They did not proliferate at all until the I. hospitalis cells reached the stationary growth phase. Then they grew exponentially with a doubling time of 45 min up to the same final cell densities as in the standard culture (Fig. 3A).

(ii) Optical-tweezer experiments.

The fermentation experiments led to the impression that only free or weakly occupied I. hospitalis cells are able to divide. To test this assumption, I. hospitalis cells with 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, or 10 attached N. equitans cells were isolated with the optical tweezers and incubated in fresh medium (10 replicates each; incubation time, 3 weeks). A cell able to reproduce resulted in a culture with about 1 × 107 cells ml−1 within 1.5 days. As shown in Table 2, occupation by N. equitans clearly inhibited the proliferation of I. hospitalis cells. Compared to N. equitans-free I. hospitalis cells, cells occupied by one or two N. equitans cells showed a reduced ability to proliferate (60 to 30%). No I. hospitalis cell with more than two attached N. equitans cells was able to proliferate and form a subculture. Furthermore, only one out of the six subcultures that evolved from occupied cells formed a coculture of N. equitans and I. hospitalis. This observation was confirmed by PCR experiments with primers specific for the 16S rRNA gene of N. equitans. With the exception of the latter culture, no PCR amplification product of N. equitans was discovered in the remaining five subcultures.

TABLE 2.

Numbers of I. hospitalis cultures and I. hospitalis and N. equitans cocultures that developed from 10 individual separation experiments using the optical tweezersa

| No. of attached N. equitans cells/separated I. hospitalis cell | No. of cultures grown from 10 separated I. hospitalis cells | No. of isolates that remained cocultures |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6 | |

| 1 | 3 | 0 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 |

The I. hospitalis cells were occupied with 0 to 10 N. equitans cells.

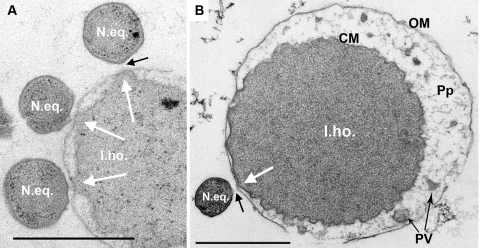

Electron microscopy.

In ultrathin sections (Fig. 4), cells of I. hospitalis and N. equitans showed the typical structural features already described (12, 13, 24, 26). The N. equitans cell is a small coccus, 0.4 μm in diameter, surrounded by a continuous sheet of an S layer, while the I. hospitalis cell is a large coccus, about 2.5 μm in diameter, surrounded by an irregular cytoplasmic membrane, a periplasmic space (30 to 400 nm in width in uninfected cells), and an outer membrane. Figure 4A and B revealed that at the attachment site of N. equitans, the cytoplasmic membrane and the outer membrane of I. hospitalis cells were in close contact (Fig. 4, white arrows). The periplasmic space was atypically narrow (<30 nm) and did not contain any of the periplasmic vesicles found in other parts of the same cell (Fig. 4B) and in all intact Ignicoccus cells (i.e., in pure culture and not lysed, with an intact cell envelope; 24, 26). Between the cells, there was a gap, approximately 20 to 50 nm wide, filled with an amorphous, fibrous biopolymer of unknown composition (black arrows).

FIG. 4.

Transmission electron micrographs of ultrathin sections of I. hospitalis and N. equitans following cryoprocessing as described in Materials and Methods. I.ho., I. hospitalis cell; CM, cytoplasmic membrane; OM, outer membrane; Pp, periplasm; PV, periplasmic vesicles; N.eq., N. equitans cell. White arrows point to the contact site where the I. hospitalis outer membrane is in close contact with the cytoplasmic membrane. Black arrows, fibrous material in the gap between the two cells. Bars, 1 μm.

Amino acid transfer from I. hospitalis to N. equitans.

To investigate a possible amino acid transfer between I. hospitalis and N. equitans, long-term 13C-labeling studies were performed by using a coculture grown in the presence of 0.5 mM [1-13C]acetate. Free N. equitans cells were separated from I. hospitalis cells by differential centrifugation (I. hospitalis contamination, <0.1%). The cells were hydrolyzed under acidic conditions, and the amino acids were separated by chromatography. The incorporation of 13C at specific carbon positions of amino acids was identified by 13C NMR spectroscopy (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

13C enrichments at individual carbon positions of amino acids from I. hospitalis (15), from mixed cells of the coculture of I. hospitalis and N. equitans, and from purified N. equitans cells after cultivation in the presence of [1-13C]acetatea

| Amino acid | Position | Relative 13C concn (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. hospitalis | Coculture | N. equitans | ||

| Alanine | 1 | NDb | 1.1 | ND |

| 2 | 16.8 | 3.3 | 3.1 | |

| 3 | 3.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | |

| Serine | 1 | ND | ND | ND |

| 2 | 15.3 | 2.3 | 3.8 | |

| 3 | 3.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| Aspartate | 1 | 1.1 | ND | ND |

| 2 | 14.5 | 3.6 | 4.3 | |

| 3 | 4.6 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| 4 | 1.1 | ND | ND | |

| Threonine | 1 | ND | 1.7 | ND |

| 2 | 14.0 | 4.5 | 7.8 | |

| 3 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 2.2 | |

| 4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| Glutamate | 1 | 20.0 | 8.7 | ++c |

| 2 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 1.1 | |

| 3 | 16.9 | 8.2 | 7.8 | |

| 4 | 5.7 | 2.3 | 1.8 | |

| 5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | ND | |

| Lysine | 1 | 22.6 | 5.6 | 10.7 |

| 2 | 76 | 2.2 | 2.8 | |

| 3 | 6.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 | |

| 4 | 26.3 | 4.2 | 6.7 | |

| 5 | 7.7 | 1.5 | 1.7 | |

| 6 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

The values shown were determined from a single experiment by quantitative nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. On this basis, we could not determine error margins. However, by comparison with other studies using quantitative nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, the errors can be estimated to be around ±25% of the listed values. Due to possible different relaxation behaviors of the reference (i.e., unlabeled material) and the bioenriched samples, the errors can be even higher for quaternary carbon atoms (for example, C-1 of lysine). Strong 13C enrichments are in boldface.

ND, not detected.

++, high signal intensity.

The labeling patterns of all amino acids under study from N. equitans and the coculture were apparently identical (Table 3). Notably, the qualitative labeling patterns were also identical to the patterns observed in a labeling experiment where a pure culture of I. hospitalis was supplied with [1-13C]acetate (15). In light of missing genes for enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of amino acids in N. equitans (31), it can be assumed that labeled amino acids made de novo from [1-13C]acetate in I. hospitalis were transferred to N. equitans. In the case of any de novo formation of amino acids by N. equitans, we would have expected significant changes in the labeling patterns of the coculture and the I. hospitalis pure culture compared to the N. equitans fractions. The significantly increased 13C enrichment of amino acids in the pure culture of I. hospitalis in comparison to amino acids from the coculture and the purified N. equitans cells can be explained easily by the different cultivation conditions in the two labeling experiments (see Materials and Methods; the high gassing rate necessary for the cultivation of the coculture leads to expulsion of the labeled acetate, which is quite volatile at 90°C and pH 5.5).

Cross infection studies.

An important characteristic of many parasite-symbiont interactions is their host specificity. Therefore, a variety of archaea that grow under conditions identical or similar to those of I. hospitalis were tested as alternative hosts. Despite numerous and highly diverse assays (see Materials and Methods), it was not possible to reinfect I. hospitalis (and other archaeal) cells with separated N. equitans cells. Assuming the possibility that separated N. equitans cells lose their infectiousness, cross infection studies with the coculture and the alternative hosts were carried out. The following organisms were all able to grow in the presence of the I. hospitalis-N. equitans coculture without one species being suppressed: Pyrodictium occultum, Pyrococcus furiosus, Pyrobaculum arsenaticum, Thermoproteus sp. strain CU1/L1B, I. pacificus, and I. islandicus. Due to their characteristic morphology (with the exception of the Ignicoccus species), it was possible to distinguish between I. hospitalis and the other archaea by light microscopy. In all cross cultivation experiments, no N. equitans cell was found to be attached to any of the alternative hosts. To distinguish between I. hospitalis and I. pacificus-I. islandicus in the cross infection experiment, single cells occupied by one N. equitans cell were isolated via optical tweezers and subcultivated and the 16S rRNA sequences of the cultures were determined (two times six subcultures). All subcultures exhibited the 16S rRNA gene of I. hospitalis.

DISCUSSION

The physiological experiments described here demonstrate that major growth parameters of the I. hospitalis culture are not influenced by the presence of N. equitans. No differences between the pure culture and the coculture were detected concerning pH, temperature, or salt ranges; shortest doubling times; or final cell densities. Under standard cultivation conditions, the presence of N. equitans was neither beneficial nor harmful to the entirety of the I. hospitalis cells in the coculture, although the situation in the natural habitat might be different. Closer examination of the coculture under laboratory conditions revealed a highly differentiated picture of the mutual interactions. Densely occupied I. hospitalis cells are no longer able to proliferate, and in isolation experiments even one attached N. equitans cell significantly reduced the ability of I. hospitalis to reproduce. Comparative lipid analyses suggested that N. equitans derives its membrane lipids from I. hospitalis (16). Long-term labeling studies with [1-13C]acetate exhibited identical 13C-labeling patterns of amino acids from N. equitans and I. hospitalis cells, suggesting that N. equitans also obtains amino acids from its host. Both results are consistent with the genome analysis of N. equitans where very few genes for biosynthetic pathways like lipid or amino acid biosynthesis were identified (31). It is obvious that such a drain of cellular components must have some negative influence on the viability and/or proliferation of I. hospitalis. Although so far there is no direct evidence of how this transfer proceeds, the data presented here contradict the vesicle-based transport assumed earlier (31). The ultrathin sections showed that, at the contact site of N. equitans and I. hospitalis, the cytoplasmic membrane of the I. hospitalis cell is very close to its outer membrane (and therefore close to the N. equitans cell) without keeping the large periplasmic space between the inner and outer membranes typical of pure cultures of Ignicoccus (26). At the moment, one can only speculate about some sort of direct connection of the cytoplasms of the two organisms. However, this is in line with the results obtained by staining with BacLight, where attached N. equitans cells always exhibit the same color (= physiological status) as their host cell. In any case, our results rule out the assumption that N. equitans immediately kills its host cells and/or feeds on dead I. hospitalis cells, as is the case for some parasitic bacteria (e.g., Bdellovibrio, Bacteriovorax) (1, 29).

We showed that the increase in the total number of N. equitans cells caused by the large increase in free N. equitans cells after heavy gassing of the fermentor (12) is independent of the amount of molecular hydrogen (between 80 and 3% [vol/vol]) and/or CO2 (between 20 and 2% [vol/vol]) in the gas mixture. Thus, the increase in the total number of N. equitans cells can be ascribed mainly to the stripping of H2S, the major metabolic end product of I. hospitalis (24).

The presence of free and attached N. equitans cells in the coculture raises the question of their different functions. Attached N. equitans cells are obviously responsible for proliferation, an assumption which is supported by the fact that N. equitans cannot be cultivated without contact with living cells of I. hospitalis (12, 13). Similar to free cells of bacterial parasites like Bdellovibrio or Micavibrio (17, 29), the free cells of N. equitans could represent the infectious form. According to the BacLight staining experiments, they seem to be alive at least for a while after separation. In addition, it has been shown that N. equitans cells express extracellular appendages (13). Whether they are used for motility, attachment, or both (23) remains to be investigated. De novo infection of unoccupied I. hospitalis cells, probably by free N. equitans cells, indeed occurs in the coculture (Fig. 1 and 2A to C). So then why is it not possible to infect pure cultures of I. hospitalis with purified free N. equitans cells? One explanation could be that the free N. equitans cells are damaged during the purification process and therefore lose their infectiousness. Alternatively, one could speculate that N. equitans can only infect new host cells as long as they are associated with the “original” Ignicoccus cell, which would simultaneously imply a close proximity of the two I. hospitalis host cells. In the natural environment (e.g., in the sediment), such contacts may occur more often; there are data showing that a lot of (hyperthermophilic) organisms grow not only planktonically but also attached to several kinds of surfaces (23).

No infections of alternative host organisms could be obtained in cocultures. This result resembles the narrow host specificity of the obligate bacterial exoparasites Vampirovibrio chlorellavorus (host, Chlorella sp. [10]) or “Micavibrio aeruginosavorus” (host, Pseudomonas aeruginosa [18]). Common features of the bacterial exoparasites and N. equitans are adherence to the cell wall of the host, exploitation of the host cell leading to limited proliferation of the host, and obligate dependence on the presence of the host for proliferation. However, the fact that I. hospitalis and N. equitans build a stable coculture without sustained damage to the Ignicoccus population clearly distinguishes N. equitans from the bacterial parasites mentioned above. Therefore, we propose that the association of I. hospitalis and N. equitans represents a highly specialized system. Consequently, assignment to the classical category of symbiosis, commensalism, or parasitism might not be possible even in the future.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are due to Michael Thomm for highly valuable discussions and support. We thank Christine Schwarz, Garching, for help with NMR spectroscopy.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant HU 703/1-2, 1-3; RA 751/5-1) and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baer, M. L., J. Ravel, S. A. Piñeiro, D. Guether-Borg, and H. N. Williams. 2004. Reclassification of salt-water Bdellovibrio sp. as Bacteriovorax marinus sp. nov. and Bacteriovorax litoralis sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 541011-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumann, P., and N. A. Moran. 1997. Non-cultivable microorganisms from symbiotic associations of insects and other hosts. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 7239-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brochier, C., S. Gribaldo, Y. Zivanovic, F. Confalonieri, and P. Forterre. 2005. Nanoarchaea: representatives of a novel archaeal phylum or a fast-evolving euryarchaeal lineage related to Thermococcales? Genome Biol. 6R42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burghardt, T., D. J. Näther, B. Junglas, H. Huber, and R. Rachel. 2007. The dominating outer membrane protein of the hyperthermophilic Archaeum Ignicoccus hospitalis: a novel pore-forming complex. Mol. Microbiol. 63166-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciccarelli, F. D., T. Doerks, C. von Mering, C. J. Creevey, B. Snel, and P. Bork. 2006. Toward automatic reconstruction of a highly resolved tree of life. Science 3111283-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Giulio, M. 2006. Nanoarchaeum equitans is a living fossil. J. Theor. Biol. 242257-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eder, W., W. Ludwig, and R. Huber. 1999. Novel 16S rRNA gene sequences retrieved from highly saline brine sediments of Kebrit Deep, Red Sea. Arch. Microbiol. 172213-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenreich, W., and A. Bacher. 2000. Elucidation of biosynthetic pathways by retrodictive/predictive comparison of isotopomer patterns determined by NMR spectroscopy. Genet. Eng. 22121-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenreich, W., F. Rohdich, and A. Bacher. 2001. Deoxyxylulose phosphate pathway to terpenoids. Trends Plant Sci. 678-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gromov, B. V., and K. A. Mamkaeva. 1980. New genus of bacteria, Vampirovibrio, parasitizing chlorella and previously assigned to the genus Bdellovibrio. Mikrobiologiia 49165-167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hohn, M. J., B. P. Hedlund, and H. Huber. 2002. Detection of 16S rDNA sequences representing the novel phylum “Nanoarchaeota”: indication for a wide distribution in high temperature biotopes. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 25551-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber, H., M. J. Hohn, R. Rachel, T. Fuchs, V. C. Wimmer, and K. O. Stetter. 2002. A new phylum of Archaea represented by a nanosized hyperthermophilic symbiont. Nature 41763-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huber, H., M. J. Hohn, K. O. Stetter, and R. Rachel. 2003. The phylum Nanoarchaeota: present knowledge and future perspectives of a unique form of life. Res. Microbiol. 154165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huber, R., S. Burggraf, T. Mayer, S. M. Barns, P. Rossnagel, and K. O. Stetter. 1995. Isolation of a hyperthermophilic archaeum predicted by in situ RNA analysis. Nature 37657-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jahn, U., H. Huber, W. Eisenreich, M. Hügler, and G. Fuchs. 2007. Insights into the autotrophic CO2 fixation pathway of the archaeon Ignicoccus hospitalis: comprehensive analysis of the central carbon metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 1894108-4119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jahn, U., R. Summons, H. Sturt, E. Grosjean, and H. Huber. 2004. Composition of the lipids of Nanoarchaeum equitans and their origin from its host Ignicoccus sp. strain KIN4/I. Arch. Microbiol. 182404-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambina, V. A., A. V. Afinogenova, S. Romai Penabad, S. M. Konovalova, and A. P. Pushkareva. 1982. Micavibrio admirandus gen. et sp. nov. Mikrobiologiia 51114-117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambina, V. A., A. V. Afinogenova, S. Romai Penobad, S. M. Konovalova, and L. V. Andreev. 1983. A new species of exoparasitic bacteria of the genus Micavibrio infecting gram-positive bacteria. Mikrobiologiia 52777-780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leuko, S., A. Legat, S. Fendrihan, and H. Stan-Lotter. 2004. Evaluation of the LIVE/DEAD BacLight kit for detection of extremophilic archaea and visualization of microorganisms in environmental hypersaline samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 706884-6886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCliment, E. A., K. M. Voglesonger, P. A. O'Day, E. E. Dunn, J. R. Holloway, and S. C. Cary. 2006. Colonization of nascent, deep-sea hydrothermal vents by a novel Archaeal and Nanoarchaeal assemblage. Environ. Microbiol. 8114-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muscholl, A., D. Galli, G. Wanner, and R. Wirth. 1993. Sex pheromone plasmid pAD1-encoded aggregation substance of Enterococcus faecalis is positively regulated in trans by traE1. Eur. J. Biochem. 214333-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Näther, D. J., and R. Rachel. 2004. The outer membrane of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Ignicoccus: dynamics, ultrastructure and composition. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32199-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Näther, D. J., R. Rachel, G. Wanner, and R. Wirth. 2006. Flagella of Pyrococcus furiosus: multifunctional organelles, made for swimming, adhesion to various surfaces, and cell-cell contacts. J. Bacteriol. 1886915-6923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paper, W., U. Jahn, M. J. Hohn, M. Kronner, D. J. Näther, T. Burghardt, R. Rachel, K. O. Stetter, and H. Huber. 2007. Ignicoccus hospitalis sp. nov., the host of “Nanoarchaeum equitans”. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57803-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pennisi, E. 2003. Symbiosis. Fast friends, sworn enemies. Science 302774-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rachel, R., I. Wyschkony, S. Riehl, and H. Huber. 2002. The ultrastructure of Ignicoccus: evidence for a novel outer membrane and for intracellular vesicle budding in an archaeon. Archaea 19-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rieger, G., K. Müller, R. Hermann, K. O. Stetter, and R. Rachel. 1997. Cultivation of hyperthermophilic archaea in capillary tubes resulting in improved preservation of fine structures. Arch. Microbiol. 168373-379. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith, D. C., and A. E. Douglas. 1987. The biology of symbiosis. Edward Arnon Ltd., London, United Kingdom.

- 29.Starr, M. P., and N. L. Baigent. 1966. Parasitic interaction of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus with other bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 912006-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terzieva, S., J. Donnelly, V. Ulevicius, S. A. Grinshpun, K. Willeke, G. N. Stelma, and K. P. Brenner. 1996. Comparison of methods for detection and enumeration of airborne microorganisms collected by liquid impingement. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 622264-2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waters, E., M. J. Hohn, I. Ahel, D. E. Graham, M. D. Adams, M. Barnstead, K. Y. Beeson, L. Bibbs, R. Bolanos, M. Keller, K. Kretz, X. Lin, E. Mathur, J. Ni, M. Podar, T. Richardson, G. G. Sutton, M. Simon, D. Soll, K. O. Stetter, J. M. Short, and M. Noordewier. 2003. The genome of Nanoarchaeum equitans: insights into early archaeal evolution and derived parasitism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10012984-12988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]