Abstract

Type I and type II interferons (IFNs) act in synergy to inhibit the replication of a variety of viruses, including herpes simplex virus (HSV). To understand the mechanism of this effect, we have analyzed the transcriptional profiles of primary human fibroblast cells that were first treated with IFN-β1, IFN-γ, or a combination of both and then subsequently infected with HSV-1. We have identified two types of synergistic activities in the gene expression patterns induced by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ that may contribute to inhibition of HSV-1 replication. The first is defined as “synergy by independent action,” in which IFN-β1 and IFN-γ induce distinct gene categories. The second, “synergy by cooperative action,” is a term that describes the positive interaction between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ as defined by a two-way analysis of variance. This form of synergy leads to a much higher level of expression for a subset of genes than is seen with either interferon alone. The cooperatively induced genes by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ include those involved in apoptosis, RNA degradation, and the inflammatory response. Furthermore, the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ induces significantly more apoptosis and inhibits HSV-1 gene expression and DNA replication significantly more than treatment with either interferon alone. Taken together, these data suggest that IFN-β1 and IFN-γ work both independently and cooperatively to create an antiviral state that synergistically inhibits HSV-1 replication in primary human fibroblasts and that cooperatively induced apoptosis may play a role in the synergistic effect on viral replication.

Interferons (IFNs) are a family of related cytokines that are classified into subgroups type I and type II according to receptor specificity and sequence homology. Type I interferon consists of multiple IFN-α subtypes, IFN-β, IFN-ω, and IFN-τ. In contrast, IFN-γ is the only type II IFN (50). Type I IFNs represent the first line of defense against many types of viral infection. Virus-infected cells synthesize and secrete type I IFNs, which act in both autocrine and paracrine fashions to induce an antiviral state in host cells (22). Although most cell types can secrete a low level of type I IFNs in vivo, certain cell types generate high IFN levels. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are the major source of IFN-α (33), while fibroblasts predominantly generate IFN-β. Alternately, IFN-γ, a potent immunoregulatory cytokine, is mainly secreted by T lymphocytes and NK cells. There is evidence that other cell types, such as antigen-presenting cells, can also synthesize IFN-γ (59).

The essential roles for both IFN types in controlling mammalian viral infection are best demonstrated in mice that have targeted mutations of type I or type II IFN receptors (41). Mice with type I or type II IFN signaling defects quickly succumb to viral infection. The fact that many viruses encode gene products to circumvent the synthesis of type I IFNs or to interfere with the signaling pathways induced by both types of IFNs further demonstrates that IFNs play an important role in inhibiting viral replication (20, 22, 49, 60).

The binding of type I IFNs to type I IFN receptors results in the rapid phosphorylation and activation of the receptor-associated Janus-activated kinases (JAKs) Tyk2 and Jak1. These kinases in turn regulate the phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factors STAT1 and STAT2. A transcriptional complex called interferon-stimulated gene factor 3 is activated by type I IFNs and consists of STAT1, STAT2, and interferon-regulated factor 9 (IRF9). This complex binds to interferon-stimulated response elements in the promoters of certain interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). In contrast, IFN-γ binds to type II IFN receptors, activates Jak1 and Jak2, and then activates STAT1. The activated STAT1 homodimers bind to the IFN-γ-activated site in the promoters of some ISGs. In addition to JAK-STAT pathways, both types of IFNs also regulate other signaling cascades, such as the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways (53).

During in vivo infections, cells around the infected region are likely to encounter both types of IFNs. Both directly infected cells and activated pDCs can secrete type I IFNs, while activated NK cells and T cells secrete IFN-γ. This concept has been collectively demonstrated by the recent literature on herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2)-infected murine vagina and human genital skin cells. For example, activated pDCs that were recruited to the mouse vagina following HSV-2 infection secreted a significant amount of type I interferon (35). Human herpetic vesicle fluid has high amounts of IFN-α as soon as 1 to 2 h after the vesicles form (45, 62). During subclinical HSV-2 reactivation, virus-specific CD8+ T cells accumulate near the sensory nerve endings in genital skin (69). Studies have demonstrated that a combination of type I and type II IFNs acts synergistically to inhibit the replication of a variety of viruses in cell cultures and mouse models. The viruses included in these studies were HSV, human cytomegalovirus, human hepatitis C virus, and severe respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (29, 54-56).

The abilities of IFNs to protect against various viral infections are derived from the complex transcriptional programs they initiate. Each type of IFN can induce the expression of hundreds of genes to mediate various biological responses (7, 13, 14). To better understand the mechanism of how type I and type II IFNs can synergistically inhibit viral replication, we analyzed the transcriptional profiles of primary human fibroblast cells treated with IFN-β1, IFN-γ, or a combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ with or without HSV-1 infection. To facilitate data analysis, we defined two types of synergistic inhibition of viral replication that occur between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ at the gene expression level. The first synergy is defined as “synergy by independent action,” in which IFN-β1 and IFN-γ induce distinct categories of genes. The second, “synergy by cooperative action,” is a term that describes the positive interaction between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ, leading to a much higher level of gene expression relative to that when either is used alone. We used Affymetrix whole human genome arrays to comprehensively annotate the genes induced by IFN-β1 and/or IFN-γ. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized to identify genes that were cooperatively induced by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ. Directed by our expression results, which identified a number of genes related to apoptosis as being cooperatively induced, we further show that apoptosis is significantly increased by the combined interferon treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and virus.

Primary human fibroblast (FB) cells were propagated in Waymouth MB 752/1 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (50 U/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml). Wild-type HSV-1 strain KOS virus stocks were used. To determine viral titers, HSV-1-infected FB cells were harvested with an equal volume of 9% nonfat milk and frozen immediately. Cells were disrupted by thawing and sonication. Titrations were carried out on Vero cells.

RNA isolation.

FB cells were seeded into six-well dishes at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells per well so that cells were about 70% confluent the following day for IFN treatment. FB cells were either treated with 100 U/ml of human IFN-β1a (PBL Biomedical Laboratories, Piscataway, NJ), 100 U/ml of human recombinant IFN-γ (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), a combination of both, or left untreated 48 h prior to infection. Mock or KOS infections were carried out at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 for 1 hour at room temperature with gentle agitation in 1% fetal bovine serum medium. After adsorption, the virus was removed and replaced with fresh medium with or without IFNs. RNA for microarrays was harvested from the FB cells 8 h postinfection (p.i.) by using the total RNA isolation system (catalog no. Z5110; Promega, Madison, WI). The total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Quantitation of HSV DNA.

FB cells were seeded and treated with IFNs and infected with KOS as described above. DNA was harvested from the cells 24 h p.i. and frozen at −20°C. The DNA was extracted using the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Five microliters of extracted DNA was used for a 50-μl-volume real-time PCR. This reaction was performed in triplicate. Each reaction mixture for the HSV gene ICP27 contained 5 μl of 10× buffer, 80 nM of ROX (Synthegen, Coralville, IA), 5.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 500 nM of each primer pair, 200 nM of probe, and 0.25 μl of TaqGold (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Each reaction mixture for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) contained 25 μl of 2× Sybr green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and 200 nM of each primer pair. The primers were as follows: GAPDH, 5′-AGAACATCATCCCTGCCTCTAC-3′ and 5′-ATTTGGCAGGTTTTTCTAGACG-3′; ICP27, 5′-TTCTCCAGTGCTACCTGAAGGC-3′ and 5′-CAAACACGAAGGAYGCAATGTC-3′; ICP27 probe, 5′-6-carboxyfluorescein-CCAGACGCCGCCGCGAA-6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine-3′. The PCR parameters were 2 min of incubation at 50°C and TaqGold activation at 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 min. The fluorescent dye intensities were read using an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). HSV-1 genome copy numbers were normalized to the amount of GAPDH DNA.

Microarray analysis.

The preparation and hybridization of cRNA to Affymetrix U133p2 chips were performed according to the standard protocol described by Affymetrix (www.affymetrix.com). GCOS1.4 data analysis was performed on each chip, and the results were imported into a quality control macro in Microsoft Excel to calculate the noise (average, 1.9 ± 0.2), the background signal level (average, 46.1 ± 3.5), the percentage of “present” calls (average, 38.6% ± 1.2%), the average signal level for all probe sets (average across all chips, 488.1 ± 12.8), the actin 3′/5′ signal ratio (average, 1.22 ± 0.12), and the GAPDH 3′/5′ signal ratio (average, 1.15 ± 0.05). Detailed quality control information for each chip is available on our website (http://expression.washington.edu/HVEC).

For statistical analysis, the cel files (Affymetrix raw data files) for all of the GeneChips were imported into the R program and analyzed using several bioconductor packages (http://www.bioconductor.org). The robust multichip averaging method was used to normalize all 16 array samples. To identify the genes that had statistically significant differential expression between the untreated and IFN-β1- or IFN-γ-treated samples, false discovery rates (FDRs) were generated using the LIMMA package (61). Differentially expressed genes were defined as those for which the change between treated (IFN-β1 or IFN-γ) and untreated samples was larger than 2-fold or less than 0.5-fold and the FDRs from the analysis using the LIMMA package in R were less than 0.05. Genes that were up- and down-regulated in response to the IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatments are listed in the supplemental material. The synergy of independent actions by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ was defined as follows: we identified genes that were significantly up-regulated by IFN-β1 or IFN-γ, as described above. Genes with gene intensities ratios for IFN-β1 versus IFN-γ treatments that were larger than 2 were considered dominantly up-regulated by IFN-β1. Genes that were dominantly up-regulated by IFN-γ were selected in a similar manner. These two sets of genes represent the synergy of independent actions by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ. The GoMiner program was used to annotate genes that were dominantly up-regulated by IFN-β1 or IFN-γ (http://discover.nci.nih.gov/gominer).

To identify genes that show cooperative synergy between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ, we treated IFN-β1 and IFN-γ as two independent factors in mock- or HSV-1-infected samples. The LIMMA package was used to identify the genes that showed interaction between the two factors (IFN-β1 and IFN-γ). FDRs were set at 0.05 to specifically select genes that showed a statistically significant interaction. This set of genes represents the cooperative synergy between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ. We have listed this set of genes on our website (http://expression.washington.edu/HVEC).

The array data from FB cells infected with HSV-1 for 4 and 8 h (MOI, 1) were generated in the same way as the data generated for IFN-treated cells. The criteria for selecting genes that were significantly affected during HSV-1 infection were as follows: the change between HSV-1-infected and mock-infected samples was larger than 1.5-fold, or less than 0.67-fold, and the FDRs from the analysis using the LIMMA package in R were less than 0.05. Genes that were up- and down-regulated during HSV-1 infection are listed on our website (http://expression.washington.edu/HVEC).

Quantitative RT-PCR.

We used a previously described method for the quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis (48). In brief, total RNA samples were treated with RNase-free DNase (Promega) and purified by using RNeasy columns (Qiagen). Total RNAs (1 μg) were reverse transcribed into cDNAs using reverse transcriptase from GIBCO-BRL. A 1/40 volume of the total cDNA volume was used per Sybr green (Applied Biosystems) PCR mixture. The PCRs were performed in an Applied Biosystems 7700 sequence detection system, and the PCR protocol was as follows: first step, 50°C for 2 min; second step, 95°C for 10 min; third step, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 min. The threshold cycle (CT) differences between control and treated samples (triplicates) were calculated, and the final changes in transcript levels equaled 2x (2 to the x power), where x is the difference in CT values. All primers were designed using the Primer 3 program from the website www.genome.wi.mit.edu and purchased from Qiagen. The primers were as follows: TNFSF10, left primer, 5′-CAGAGGAAGAAGCAACACATTG-3′, and right primer, 5′-TTTTCATGGATGACCAGTTCAC-3′; MX1, 5′-CGAGTTCCACAAATGGAGTACA-3′ and 5′-TTCACGATTGTCTCAAATGTCC-3′; CXCL10, 5′-TGACTCTAAGTGGCATTCAAGG-3′ and 5′-AATGATCTCAACACGTGGACAA-3′; TNFRSF10D, 5′-GATTACACCATTGCTTCCAACA-3′ and 5′-TCTCAGGGGAGTTTTTATCCTG-3′. TaqMan rRNA control reagent (catalog no. 4308329; Applied Biosystems) was used to assay the expression levels of rRNA according to the manufacturer's instructions. TaqMan PCR was performed to detect the expression of HSV-1-encoded ICP27, and a Sybr PCR was used to assay the expression of HSV-1-encoded ICP8 and glycoprotein B (gB). The primer and probe sequences were as follows: ICP27 primers, 5′-TTCTCCAGTGCTACCTGAAGGC-3′ and 5′-CAAACACGAAGGAYGCAATGTC-3′; ICP27 probe, 5′-CCAGACGCCGCCGCGAA-3′; ICP8 primers, 5′-AATCCGGCATGAACAGCTG-3′ and 5′-CGTGTGCATCCAACACCTT-3′; gB primers, 5′-CGCATCAAGACCACCTCCTC-3′ and 5′-GCTCGCACCACGCGA-3′.

Assays to detect apoptosis.

The FB cells were plated on four-well chamber slides (50,000 cells/per well; Corning) and incubated overnight. The next day, FB cells were treated with IFN-β1 and/or IFN-γ (100 U/ml) for 48 h and then infected with HSV-1 (KOS) at an MOI of 5 for 12 h. The cells were stained with Annexin-V-biotin (catalog no. 1828690; Roche) according to the standard protocol provided by the manufacturer. The avidin-fluorescein-stained cells were visualized under a fluorescence microscope. The caspase 3/7 assay kit was purchased from Promega (catalog no. G8091). FB cells (9,000 cells/96-well plate) were plated overnight and then treated with IFN-β1 and/or IFN-γ for 48 h. The cells were then infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 5 for 12 h. The biochemical reactions were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The luminescent signals were detected using a Bio-TEK synergy HT machine (BioTek Instruments) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

IFN-β1 and IFN-γ synergistically inhibit HSV-1 replication in primary human fibroblast cells.

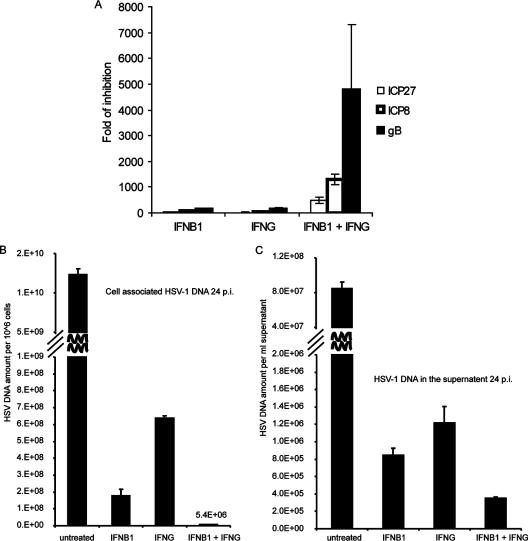

Previous studies (54) had shown that IFN-β1 and IFN-γ synergistically inhibit HSV-1 replication in a variety of cells (Vero, SK-N-SH, and primary mouse kidney cells). To ascertain that IFN-β1 and IFN-γ could synergistically inhibit HSV-1 replication in primary human FB cells, FB cells were treated with various concentrations of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ for 48 h and then infected with HSV-1 for 24 h. We found that HSV-1 titers were only reduced by less than fivefold in cells that were treated with IFN-β1 or IFN-γ at concentrations less than 10 U/ml relative to HSV-1-infected FB cells that were not treated with IFN-β1 or IFN-γ. By increasing the concentration of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ to 100 U/ml, we could detect a significant inhibition of HSV-1 replication when the cells were treated with IFN-β1 or IFN-γ. At this concentration, the viral titer was reduced by 347- and 73-fold by the IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatments, respectively (Fig. 1). The combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ reduced HSV-1 titers by more than 6,800-fold, demonstrating that IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatments at 100-U/ml concentrations synergistically inhibited HSV-1 replication in FB cells.

FIG. 1.

IFN-β1 and IFN-γ synergistically inhibit HSV-1 replication in primary human FB cells. FB cells were first treated with IFN-β1, IFN-γ, or a combination of both at a concentration of 100 U/ml for 48 h. Cells were then infected with HSV-1 (KOS strain; MOI, 1) for 24 h. Control cells were left untreated. The viral titers were determined in Vero cells. The error bars represent 1 standard deviation from three biological replicates. The y axis is on a logarithmic scale.

IFN-β1 and IFN-γ induce distinct functional categories of genes that work in a synergistic manner to inhibit viral replication.

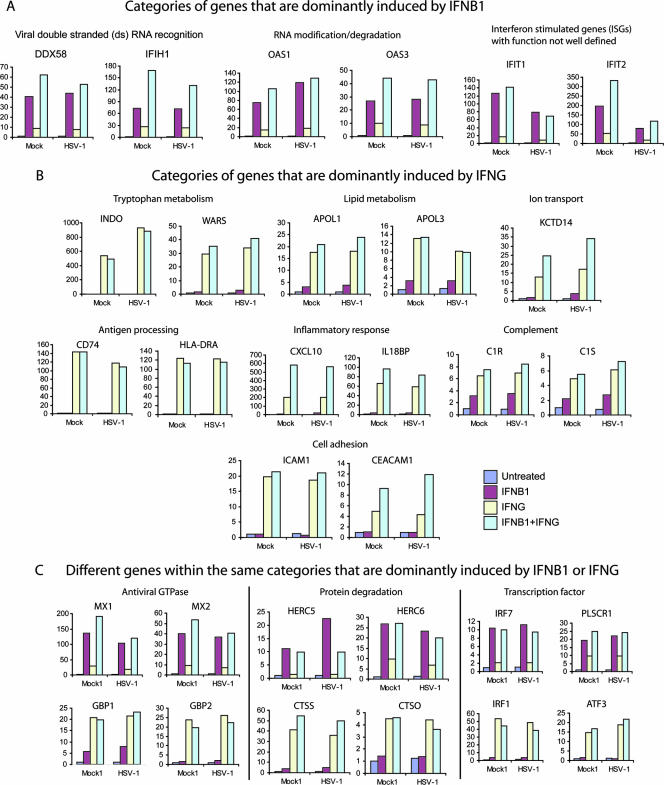

To understand the mechanism by which IFN-β1 and IFN-γ synergistically inhibit viral replication, we generated and analyzed the transcriptional profiles of FB cells that were first treated with IFN-β1, IFN-γ, or a combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ for 48 h and then were infected with HSV-1 for 8 h. Using the stringent statistical methods described in Materials and Methods, we found that IFN-β1 up-regulates 301 genes and down-regulates 44 genes, while IFN-γ up-regulates 475 genes and down-regulates 198 genes (see Tables S1 to S4 in the supplemental material for complete lists of these genes). As detailed in Materials and Methods, we selected genes that were dominantly induced by either IFN-β1 or IFN-γ. In brief, we first identified genes that were significantly induced by IFN-β1, and from this set of genes we further selected a subset of genes in which the ratios of gene intensities in IFN-β1-treated versus in IFN-γ-treated samples were larger than 2. Likewise, genes that were dominantly induced by IFN-γ were similarly defined. These genes collectively represented the synergy of independent actions by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ (Fig. 2). In other words, this type of synergy can be thought of as a “one-two punch” in which different antiviral responses are created by each interferon.

FIG. 2.

Synergy of independent action between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ: IFN-β1 (A) and IFN-γ (B) each dominantly induce different functional categories of genes and different genes within the same functional categories (C). Primary human FB cells were treated with IFN for 48 h and then infected with HSV-1 (KOS strain; MOI, 1) for 8 h. Control cells were not treated with IFN. Transcriptional profiling was performed with isolated total RNA. The criteria to select genes that are dominantly activated by IFN-β1 or IFN-γ are detailed in Materials and Methods. The complete gene list within each category is provided in Table S5 of the supplemental material. The annotation of genes was accomplished using the GoMiner program and by manual curation using the NCBI gene database. The y axis values refer to the changes over untreated and mock-infected samples. A gene symbol is on top of each bar graph, and a gene category name is on top of the gene symbol(s).

Compared to IFN-γ, IFN-β1 more potently induced the expression of genes involved in the recognition of viral double-stranded RNA and RNA degradation (Fig. 2A). For instance, DDX58 and oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS1) were up-regulated 40- and 75-fold by IFN-β1, while they were only induced 9- and 15-fold by IFN-γ, respectively. Both DDX58 (also called RIG-I) and IFIH1 (also called MDA5 or MDA-5) encode putative RNA helicases involved in viral double-stranded RNA recognition and regulation of the host innate immune response (4, 26, 66). Both OAS1 and OAS3 encode enzymes that modify RNA for its degradation (68). Several studies have shown that overexpression of various OAS isoforms inhibits the replication of picornavirus and flavivirus (9, 24) and that the HSV-1-encoded Us11 protein inhibits the enzymatic activities of OAS (57). Several known ISGs, such as IFIT1 and IFIT2, are more strongly induced by IFN-β1 than by IFN-γ, and the biological functions of many of these ISGs are not well known.

Alternatively, we found that IFN-γ more strongly induced gene expression with its own distinct set of functional categories compared to IFN-β1 (Fig. 2B). IFN-γ had a broad effect of up-regulating genes involved in metabolism. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (INDO) is an enzyme that catalyzes the degradation of the essential amino acid l-tryptophan and was the strongest gene induced by IFN-γ (more than 500-fold). In contrast, IFN-β1 has little effect on the expression of INDO. INDO mediates IFN-γ to inhibit HSV-2 and measles virus replication (1, 44). IFN-γ also up-regulated several genes in the apolipoprotein L family (APOL1 and -3) that are involved in lipid transport. In addition, several genes for ion transport were up-regulated by IFN-γ. Consistent with the well-established evidence that IFN-γ is a strong immunomodulatory cytokine, our array data show that IFN-γ strongly up-regulates the expression of genes for antigen processing, the inflammatory response, complement activation, and cell adhesion (see the supplemental material).

IFN-β1 and IFN-γ also induced distinct genes within the same categories (Fig. 2C). IFN-β1 and IFN-γ strongly up-regulated distinct gene sets of antiviral GTPases. IFN-β1 is known to induce the MX family of GTPases, such as MX1 and MX2. In our primary human fibroblast cells, MX1 and MX2 were induced 136- and 40-fold by IFN-β1, while they were only induced 29- and 9-fold by IFN-γ, respectively. MX1 inhibits the replication of several viral families, such as orthomyxoviruses (47), paramyxoviruses (58), rhabdoviruses (47), and bunyaviruses (19). In contrast, IFN-γ potently induced guanylate binding proteins (GBPs), a different family of GTPase (36). For instance, GBP4 and GBP5 were up-regulated 33- and 103-fold by IFN-γ, but they were induced only 2.7- and 3.7-fold by IFN-β1, respectively. Although GBPs inhibit the replication of vesicular stomatitis virus and encephalomyocarditis virus in vitro (2, 8), it is not clear how these GTPases mediate the host innate immune response to viral infection in vivo.

IFN-β1 and IFN-γ also up-regulate distinct genes that control protein degradation. IFN-β1 up-regulated HERC5 and HERC6 by 11- and 27-fold, while IFN-γ up-regulated them only 1.4- and 9.8-fold, respectively. HERC5 and HERC6 belong to the HERC family of ubiquitin ligases. A recent paper showed that HERC5 mediates ISG15, an interferon-stimulated gene product containing two ubiquitin-like domains that conjugate to various cellular proteins (ISGylation) upon interferon stimulation (65). Although ISG15 (also called G1P2) is strongly induced by both IFN-β1 and IFN-γ, it is dominantly induced by IFN-β1 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The importance of ISG15 in mediating interferon to create an antiviral state has been demonstrated in recent literature. ISG15 has been shown to play an important role in controlling viral replication in murine models, including HSV-1 (31). Furthermore, the influenza B virus NS1 protein has been shown to block the covalent linkage of ISG15 to its target proteins (67).

In contrast, IFN-γ strongly activated several cathepsins (CTSS, CTSC, and CTSO) that are likely involved in the protein degradation process. For instance, CTSS was up-regulated 41- and 3.8-fold by IFN-γ and IFN-β1, respectively. The proteins encoded by CTSS and CTSC belong to the peptidase C1 family and are lysosomal cysteine proteinases that may participate in the degradation of antigenic proteins to peptides for presentation on major histocompatibility complex class II molecules (5).

IFN-β1 and IFN-γ also up-regulated their own distinct sets of transcription factors. IRF1, a transcriptional factor known to be critical for IFN-γ signaling, was preferentially up-regulated by IFN-γ (28). On the other hand, IRF7, a transcription factor known to be induced by viral infection and type I IFN treatment, was much more strongly activated by IFN-β1 (23). There are several other transcription factors that were dominantly induced by IFN-β1 or IFN-γ (Fig. 2C; see also Table S5 in the supplemental material), and it is not known how these transcription factors which were induced by IFN-β1 or IFN-γ may contribute to the expression of ISGs.

Taken together, the array data show that individual IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatments induce gene expression in distinct functional categories and in distinct gene sets within the same categories. The complete list of categories and genes that represent the independent action of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ is provided in Table S5 in the supplemental material. These distinct categories and genes likely work synergistically to inhibit HSV-1 replication.

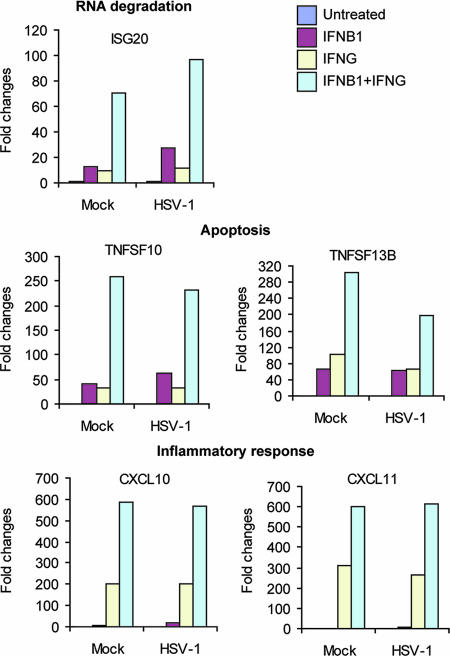

A combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatment cooperatively induces the expression of genes for RNA degradation, apoptosis, and inflammatory response.

In addition to the independent actions of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ, we were also interested in how these two factors work cooperatively to induce higher gene expression levels or to induce sets of genes that either IFN alone would not induce. Hence, we treated IFN-β1 and IFN-γ as two independent factors in the statistical analysis. The LIMMA package in R was utilized to identify genes whose expression showed a positive interaction between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ (see Materials and Methods for details). The FDR was set at 0.05 to specifically select genes that showed a statistically significant interaction. A total of 238 genes were identified to have a positive interaction between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ. These genes represent the synergy of cooperative actions between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ. Therefore, the genes from this group are induced much more highly when IFN-β1 and IFN-γ are added in combination relative to treatment with either IFN alone. Figure 3 shows a subset of these genes (see Table S6 in the supplemental material for the complete gene list). ISG20, a known ISG, encodes a 3′-5′ exoribonuclease that degrades single-stranded RNA and DNA. ISG20 has antiviral activity for a variety of viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus and influenza virus A (16, 17). ISG20 was up-regulated 12.8- and 9.7-fold by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ, respectively, yet was up-regulated 70.8-fold by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ together. TNFSF10 (also called TRAIL) is known to induce apoptosis in cancer cells (11) and cells infected with a variety of viruses, including reovirus (10), respiratory syncytial virus (27), human immunodeficiency virus (34), and dengue virus (37). TNFSF10 was induced 63-fold by IFN-β1 alone, 34-fold by IFN-γ alone, and 232-fold by the combination of both. We also found that several chemokines, such as CXCL10 and CXCL11, are strongly induced by IFN-γ but poorly induced by IFN-β1 (they are dominantly induced by IFN-γ, as shown in Fig. 2). Yet, both CXCL10 and CXCL11 are still much more highly induced by the combined IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatments. Thus, these genes are also cooperatively induced by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ, as shown in Fig. 3. A recent paper showed that an elevated expression of CXCL10, along with alpha interferon, gamma interferon, and OAS at the oral mucosal site, significantly correlates with a slower progression of simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus macaques (39). Furthermore, the gene expression patterns induced by IFN-β1, IFN-γ, and the combination of both are highly similar in cells under mock- and KOS-infected conditions. In summary, IFN-β1 and IFN-γ show a cooperative synergy in up-regulating many genes, including ISG20, TNFSF10, CXCL10, and CXCL11. The cooperative induction of antiviral genes such as ISG20 and TNFSF10 by the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ may also contribute to the synergistic inhibition of HSV-1 replication.

FIG. 3.

Cooperative synergy between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ: a combination treatment of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ induced expression of genes for RNA degradation, apoptosis, and the inflammatory response to a much higher level than individual interferon treatments. The criterion for selecting genes that are cooperatively induced by a combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ was the following: FDRs, as determined from the LIMMA package in R, were <0.05. The annotation was manually completed using the NCBI gene database. The complete list of genes that showed a positive interaction between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ is provided in Table S6 of the supplemental material. The y axis values refer to the changes over untreated and mock-infected samples.

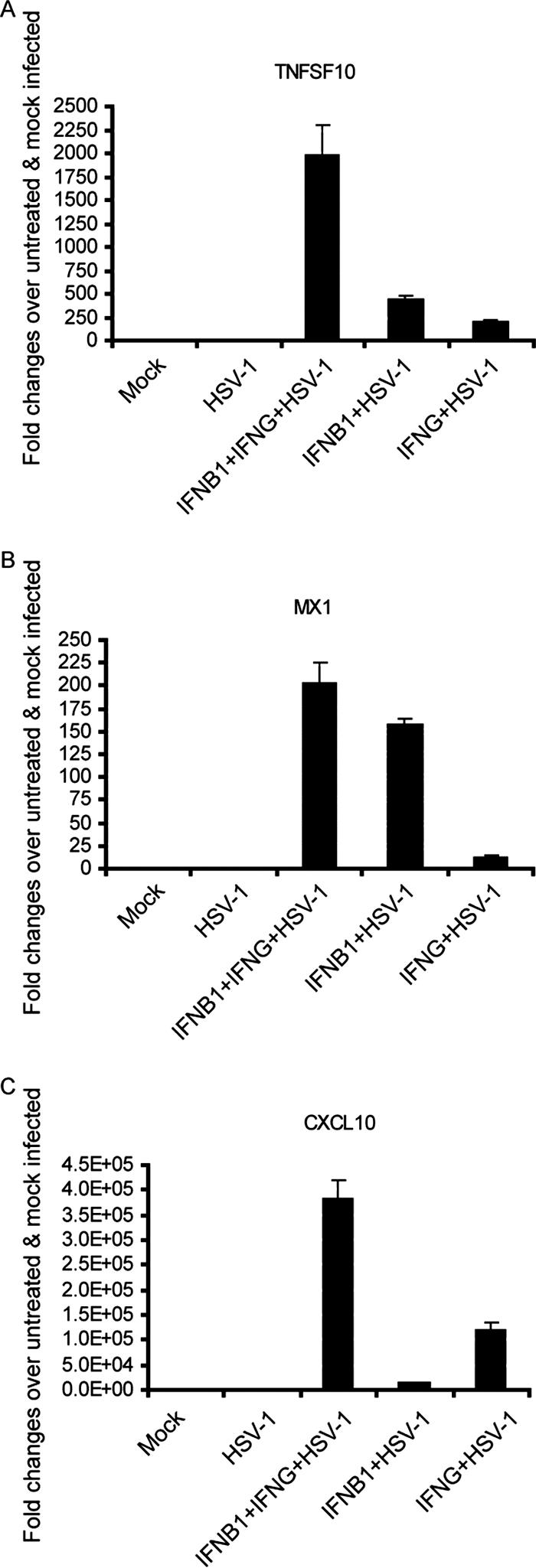

Assay of independent samples by quantitative RT-PCR to confirm the patterns of gene expression detected by microarrays.

We assayed an independent set of samples by quantitative RT-PCR to verify the patterns of gene expression seen with DNA microarrays. In our array data, TNFSF10 was induced 63-fold by IFN-β1, 34-fold by IFN-γ, and 232-fold by the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ. Quantitative RT-PCR showed that TNFSF10 was induced 439-fold by IFN-β1, 193-fold by IFN-γ, and 1,975-fold by the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ (Fig. 4). Although quantitative RT-PCR reveals a large dynamic range of induction, the patterns of TNFSF10 expression are highly similar in both methods. We also confirmed the patterns of MX1 and CXCL10 expression by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Quantitative RT-PCR using an independent set of samples confirmed the gene expression patterns that were observed in microarrays. Primary human FB cells were first treated with IFN-β1 (100 U/ml), IFN-γ (100 U/ml), or both for 48 h. The cells were then infected with HSV-1 (KOS strain; MOI, 1) for 8 h. Control cells were left untreated. Total RNA was extracted from the biological samples and used for quantitative RT-PCR. Gene expression levels of TNFSF10 (A), MX1 (B), and CXCL10 (C) were normalized to rRNA expression levels. The error bars represent 1 standard deviation from the average value obtained from triplicate biological samples.

IFN-β1 or IFN-γ dominantly induced genes are significantly down-regulated by HSV-1 infection in primary human fibroblast cells.

HSV is a large DNA virus known to encode gene products that enable viral evasion of the host's innate immune response (30). At the transcription level, several studies have shown that HSV-1 encodes ICP0, an immediate-early gene that can inhibit the transcription regulatory functions of IRF3 (15, 32, 38, 40, 43). Therefore, we can reasonably hypothesize that HSV may antagonize the effects of IFNs by down-regulating the expression of ISGs. Transcriptional profiling of HSV-1-infected FB cells for 4 and 8 h revealed that HSV-1 infection up-regulates 416 genes and down-regulates 1,167 genes. (The complete list of these genes is provided in Table S7 in the supplemental material.) Many of the genes down-regulated by HSV-1 infection are those that are dominantly induced by IFN-β1 or IFN-γ (Fig. 2). For instance, MYD88 is an adaptor protein for Toll-like receptor signaling pathways that was dominantly induced by IFN-β1 and significantly down-regulated by HSV-1 infection (Fig. 5). The down-regulation of ISGs by HSV-1 seems to be progressive from 4 to 8 h p.i., but HSV-1 infection seems to have little effect in reversing the induction of these genes in cells pretreated with IFN-β1 and/or IFN-γ for 48 h. Interestingly, a recent paper (46) showed that many ISGs, including IFIH1 and MX2 (Fig. 5), were up-regulated in HSV-1 (17syn+ strain)-infected murine embryonic fibroblasts. The HSV-1 strain and cell type differences may explain the differences in our observations. In general, HSV-1 infection in our primary human fibroblasts down-regulated or did not affect the expression of ISGs. However, a few ISGs, such as IFIT2 (ISG54), are up-regulated in HSV-1-infected FB cells (see Table S7 in the supplemental material). In summary, HSV-1 infection in primary human fibroblasts down-regulates the expression of many ISGs that represent synergy of independent action by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ, suggesting that these gene categories may play important roles in inhibiting HSV-1 replication.

FIG. 5.

Genes that are dominantly induced by IFN-β1 or IFN-γ are significantly down-regulated by HSV-1 infection in primary human FB cells. Transcriptional profiling was performed with the total RNA isolated from FB cells infected with HSV-1 (KOS strain; MOI, 1) for 4 and 8 h. Among the genes that are significantly down-regulated during HSV-1 infection, many genes are dominantly induced by either IFN-β1 or IFN-γ, as shown in Fig. 2.

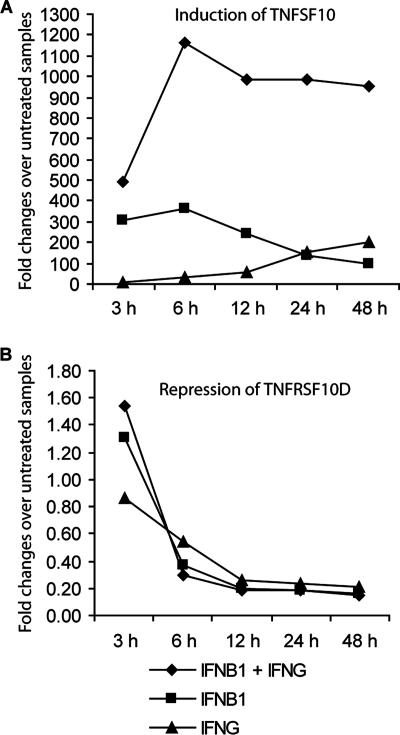

IFN-β1 and IFN-γ induce TNFSF10 and repress TNFRSF10D, a TNFSF10 decoy receptor.

Our array experiments demonstrated that TNFSF10 is significantly induced by IFN-β1 or IFN-γ and is cooperatively up-regulated by a combination of both IFNs. From the array analysis, we also discovered how TNFSF10 receptors are regulated by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ. The functional receptors for TNFSF10 are TNFRSF10A and -10B (also called DR4 and DR5, respectively). TNFRSF10B was highly expressed in FB cells, and its expression was not affected by interferon treatment and/or HSV-1 infection. In contrast, TNFRSF10A was barely detected. TNFRSF10D (also called DCR2), a decoy receptor for TNFSF10, was also highly expressed in FB cells, and its expression was significantly down-regulated by IFN-β1 or IFN-γ (see Tables S2 and S4 in the supplemental material). The coordinated up-regulation of TNFSF10 and down-regulation of TNFRSF10D after 48 h of interferon treatment prompted us to define the expression of TNFSF10 and TNFRSF10D over time following interferon treatment. As shown in Fig. 6A, IFN-β1, IFN-γ, and the combination of both IFNs up-regulated TNFSF10 with different kinetics. The induction of TNFSF10 by IFN-β1 and by the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ peaked at 6 h; at later time points, TNFSF10 induction by IFN-β1 decreased significantly (from 364-fold at 6 h to 98-fold at 48 h), but this decrease was minimal when the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ was used (from 1,166-fold at 6 h to 950-fold at 48 h). In contrast, the induction of TNFSF10 by IFN-γ gradually increased from 3 h to 48 h. Furthermore, the synergistic induction of TNFSF10 by the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ was evident at every time point. Alternatively, TNFRSF10D was gradually down-regulated from the 3-h to the 48-h time points by both the individual and combined IFN treatments (Fig. 6B). The temporal expression patterns of TNFSF10 and TNFRSF10D suggest that TNFSF10 may play an important role in mediating interferon's inhibition of HSV-1 replication through an increase in apoptosis.

FIG. 6.

A combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ administered concurrently induces TNFSF10 expression and represses TNFRSF10D expression. Primary human FB cells were untreated or treated with IFN-β1 (100 U/ml), IFN-γ (100 U/ml), or a combination of both over a 48-h time course. At 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after IFN treatment, total RNA was extracted from the cells. The quantitative RT-PCR was used to assay the expression of TNFSF10 (A) and TNFRSF10D (B). The expression levels of TNFSF10 and TNFRSF10D were normalized to rRNA expression. The y axis values refer to the fold change over untreated samples at each time point.

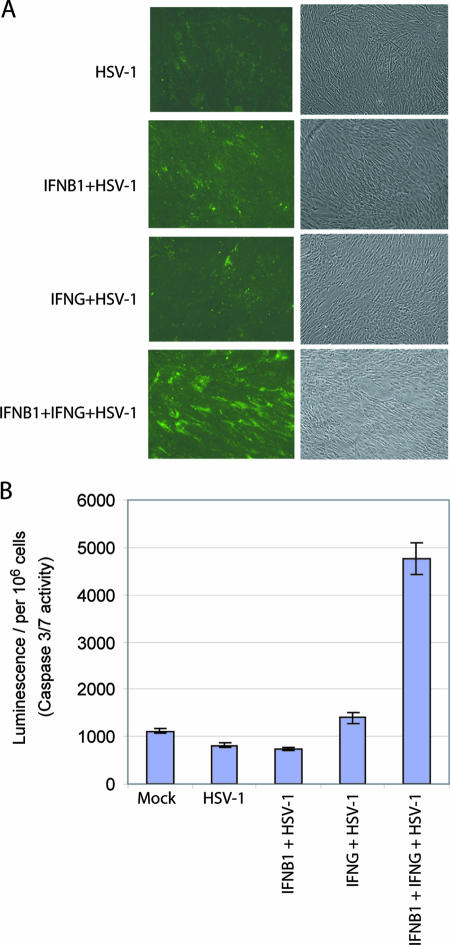

The combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ induces significantly more apoptosis in HSV-1-infected primary human fibroblast cells relative to treatment with individual IFNs.

Since TNFSF10 was up-regulated and TNFRSF10D was down-regulated in the samples that underwent combined IFN treatment, we asked whether IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatment of primary human fibroblast cells and subsequent HSV-1 infection induces more apoptosis than in cells treated with either IFN-β1 and IFN-γ alone and subsequently infected with HSV-1. We assessed the levels of apoptosis by annexin staining of the membranes of HSV-1-infected cells that had been treated with IFN-β1, IFN-γ, or both for 48 h (Fig. 7A). The assay detected significantly more apoptosis in cells that were first treated with IFN-β1 and IFN-γ in combination and then infected with HSV-1 than in cells that were first treated with IFN-β1 or IFN-γ alone and then infected with HSV-1. The cells that were untreated and uninfected (data not shown) or untreated and then HSV-1 infected showed little apoptosis in this assay. Interestingly, we started the experiment with an HSV-1 infection at an MOI of 1 and found no significant difference in apoptosis between the FB cells that had been treated individually with IFN-β1 and IFN-γ or those that had undergone a combined treatment. When we increased the MOI of the HSV-1 infection to 5 or higher, we observed significantly more apoptosis in IFN-β1- and IFN-γ-treated cells than in cells treated with only one IFN.

FIG. 7.

The combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ induces significantly more apoptosis than individual IFN-β1 or IFN-γ treatments in HSV-1-infected primary human FB cells. FB cells were first treated with IFN-β1 (100 U/ml), IFN-γ (100 U/ml), or both for 48 h. Then, the cells were infected with HSV-1 (KOS strain; MOI, 5) for 12 h. Control cells were left untreated. (A) Cells were stained with annexin-V, and apoptotic cells were visualized by positive fluorescence staining. The images are representative of three biological repeats. (B) Cells were lysed and assayed for the enzymatic activities of caspases 3/7. The error bars represent 1 standard deviation from the average of three biological replicates.

Caspases 3 and 7 are the “executioners” in the TNFSF10 signaling cascade (64). We measured the enzymatic activities of both caspases in IFN-treated and/or HSV-1-infected FB cells (Fig. 7B). Upon HSV-1 infection, the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ significantly induced more caspase 3/7 activities than the individual IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatments. (The luminescent signals were 741, 1,402, and 4,768 per 106 cells in cells treated with IFN-β1, IFN-γ, or the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ, respectively.) In contrast, a recent paper (52) reported that the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ did not prime Vero cells (African green monkey kidney cells) to undergo HSV-1-induced apoptosis. Since both our study and the previous study (52) used the HSV-1 KOS strain, the observed difference is likely due to different cell types used in the studies, e.g., primary cells in our study and immortalized cells in the previous work. Taken together, the data suggest that the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ induces significantly more apoptosis in primary human fibroblast cells to inhibit HSV-1 replication, as predicted by the gene expression changes in TNFSF10 and its decoy receptor.

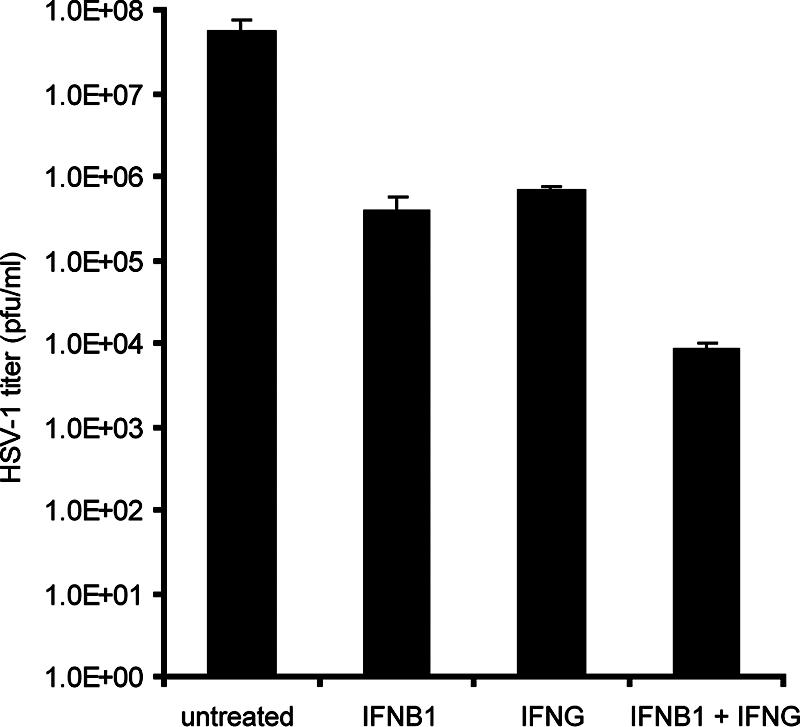

The combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ synergistically inhibits HSV-1-encoded gene expression and DNA replication in primary human fibroblast cells.

Previous work (52) demonstrated that type I and type II interferons synergistically inhibit HSV-1 gene expression and DNA replication in Vero cells. Our expression profiling suggests that the independent and cooperative antiviral actions induced by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ in primary human fibroblast cells lead to synergistic inhibition of HSV-1 replication (Fig. 1). To understand the mechanism of how a combined IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatment synergistically reduces viral titers in primary human fibroblast cells, we measured HSV-1-encoded gene expression and DNA replication in FB cells pretreated with IFN-β1, IFN-γ, or a combination of both IFN-γ and IFN-γ. First, we measured the expression of three HSV-1-encoded genes, ICP27, ICP8, and gB, in FB cells that were first treated with IFN-β1, IFN-γ, or a combination of both and then infected with HSV-1. ICP27, ICP8, and gB represent three phases of HSV-1-encoded gene expression, immediate early, delayed early, and late phases, respectively, during infection. The combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ synergistically inhibited the expression of all three HSV-1-encoded genes. For instance, individual IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatments inhibited the expression of ICP8 by about 60-fold, yet the combination of both IFNs inhibited its expression by more than 1,300-fold (Fig. 8A). We also measured the amount of HSV-1 DNA in the infected cells (Fig. 8B) and in the supernatant (Fig. 8C). In both cases, the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ synergistically inhibited HSV-1 DNA replication. Individual IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatments only inhibited HSV-1 DNA replication by 69- and 19-fold, respectively, while the combination of both IFNs inhibited viral DNA replication by more than 2,200-fold in the infected cells (Fig. 8B). Taken together, the data suggest that the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ synergistically inhibited HSV-1-encoded gene expression and DNA replication, leading to the synergistic reduction of viral titers in HSV-1-infected primary human fibroblast cells.

FIG. 8.

IFN-β1 and IFN-γ synergistically inhibit HSV-1-encoded gene expression and DNA replication in primary human FB cells. Total RNA and genomic DNA were extracted from cells that were first either left untreated or interferon treated for 48 h. The cells were then infected with HSV-1 (KOS; MOI, 1) for either 8 h (for RNA extraction) or 24 h (for DNA extraction). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was used to measure the expression of three HSV-1-encoded genes, ICP27, ICP8, and gB (A), of HSV-1 DNA in the cells (B), or of HSV-1 DNA in the supernatant (C). The HSV-1 gene expression was normalized to the rRNA expression. The amount of HSV-1 DNA was normalized to that of GAPDH DNA. The error bars represent 1 standard deviation from the three biological replicates. The fold change in inhibition on the y axis in panel A was calculated using untreated and HSV-1-infected samples as denominators.

DISCUSSION

To understand the mechanism of synergistic inhibition of viral replication by a combination of type I and type II IFNs, we generated and analyzed the transcriptional profiles of primary human FB cells that were first treated with IFN-β1, IFN-γ, or a combination of both and then subsequently infected with the KOS strain of HSV-1. Using whole human genome DNA microarrays, we were able to comprehensively annotate genes that are significantly up- or down-regulated by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ. We defined two types of synergy in gene expression induced by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ that contribute to synergistic inhibition of HSV-1 replication. “Synergy of independent action” was used to describe the synergistic effect resulting from the combined independent effects of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ on host cell gene expression. In contrast, “cooperative synergy” was used to describe the positive interaction between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ as defined by a two-way ANOVA and how the two IFNs induced higher gene expression levels when in combination than when alone. Both types of synergy play a role in the synergistic inhibition of HSV-1 by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ.

Among the hundreds of ISGs induced by IFN-β1 and/or IFN-γ, only a small set has been well studied. Therefore, we do not fully understand the biological roles of many ISGs. Nevertheless, by annotating the ISGs that are dominantly induced by IFN-β1 or IFN-γ, we propose that a synergy of independent action by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ mediates a combination of both IFNs to synergistically inhibit viral replication. For instance, IFN-β1 dominantly induces genes involved in RNA processing. Previous work showed that DDX58 recognizes both double- and single-stranded RNA during viral replication and therefore plays an important role in the host innate immune response (51, 66). Besides its role in recognizing viral RNA, MDA5 may also contribute to apoptosis during interferon treatment (25). Likewise, IFN-β1 also dominantly induces OAS, another class of molecule that is known to play a critical role in mediating IFNs to inhibit viral replication (6, 9, 24). On the other hand, we found that IFN-γ induces many genes involved in metabolism. For example, INDO, a gene induced by IFN-γ in our work, is known to mediate the IFN-γ-induced inhibition of both DNA and RNA virus replication (1, 44).

IFN-β1 and IFN-γ induced distinct genes in the category of antiviral GTPases. The MX and GBP families of GTPases are dominantly induced by IFN-β1 and IFN-γ, respectively. These GTPases have been shown to inhibit the replication of a variety of viruses (2, 19, 63). Although we do not understand the details of how these GTPases inhibit viral replication, previous work has shown that MX1 binds the nucleocapsid protein of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (3). When more biological roles of ISGs are elucidated in future studies, we will be able to better understand on how type I and type II IFNs utilize the synergy of independent action to synergistically inhibit viral replication.

We treated IFN-β1 and IFN-γ as two independent factors in our statistical analysis of the microarray data. More than two hundred genes were identified as having a positive interaction between IFN-β1 and IFN-γ. Thus, we propose that IFN-β1 and IFN-γ utilize cooperative synergy to synergistically inhibit viral replication. TNFSF10 (also called TRAIL) and ISG20 are at the top of the list in terms of the statistical significance of their positive interaction as determined by the two-way ANOVA. The biological functions of TNFSF10 have been well investigated. TNFSF10 selectively induces apoptosis in cancer and virally infected cells, specifically in cells infected with reovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, or dengue virus, or in type I interferon-treated myeloma cells (10, 12, 27, 37). Alternatively, ISG20 encodes a 3′-5′ exonuclease that can degrade single-stranded DNA and RNA (42). In addition to its diffuse cytoplasmic and nucleoplasmic localization, ISG20 associates with promyelocytic leukemia (PML), a nuclear body (NB) protein (21). PML-associated NBs are thought to play an important role in inhibiting viral gene expression and DNA replication, including the inhibition of HSV (18). Since two NB-associated proteins, PML and SP110, are significantly induced by individual and combined interferon treatments, it is conceivable that a combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ may regulate the functions of NBs through the cooperative induction of ISG20, thus leading to synergistic inhibition of HSV-1-encoded gene expression and DNA replication.

In primary human fibroblast cells, the cooperative induction of TNFSF10 and significant repression of TNFRSF10D (a decoy receptor for TNFSF10) suggest that apoptosis may be a mechanism by which IFN-β1 and IFN-γ synergistically inhibit HSV-1 replication. Using this insight gained from our array analysis, we showed that combined IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatment induced significantly more apoptosis than when cells were treated with IFN-β1 and IFN-γ individually. To further define the role of TNFSF10 in the interferon-induced apoptosis of HSV-1-infected cells, we also attempted to block TNFSF10 signaling with a TNFSF10-neutralizing antibody in cells that had been first treated with IFN-β1 and IFN-γ and then infected with HSV-1. This treatment increased HSV-1 replication by 46% (based on the amount of HSV-1 DNA) compared to such cells without the TNFSF10 antibody (data not shown). Unfortunately, this relatively modest reversal of viral replication is suggestive but not demonstrative evidence that TNFSF10-mediated apoptosis plays a key role in the synergistic inhibition of viral replication by the combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ.

In summary, we have determined that a combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ treatment in primary human FB cells induces two types of synergistic activity at the gene expression level, synergy of independent action and cooperative synergy. From the functional annotation of genes that belong to the two types of synergy, we suggest that gene products within the two types of synergy may mediate IFN-β1 and IFN-γ to synergistically inhibit HSV-1 replication in FB cells. Consistent with the changes in expression of genes involved in apoptosis, we further demonstrated that a combination of IFN-β1 and IFN-γ induced significantly more apoptosis than the individual interferons when used alone. This result suggests that IFN-β1 and IFN-γ synergistically inhibit HSV-1 replication by inducing apoptosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Becky Drees, Reneé Ireton, and Tina Montgomery for critical readings of the manuscript.

R.E.B. and T.P. are supported by NIH NIAID grant 5P01AI052106. R.E.B.'s bioinformatics infrastructure is additionally supported by NIH NCRR 1S10RR019423.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 December 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, O., K. Besken, C. Oberdorfer, C. R. MacKenzie, D. Russing, and W. Daubener. 2004. Inhibition of human herpes simplex virus type 2 by interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor alpha is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Microbes Infect. 6806-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, S. L., J. M. Carton, J. Lou, L. Xing, and B. Y. Rubin. 1999. Interferon-induced guanylate binding protein-1 (GBP-1) mediates an antiviral effect against vesicular stomatitis virus and encephalomyocarditis virus. Virology 2568-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson, I., L. Bladh, M. Mousavi-Jazi, K. E. Magnusson, A. Lundkvist, O. Haller, and A. Mirazimi. 2004. Human MxA protein inhibits the replication of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. J. Virol. 784323-4329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrejeva, J., K. S. Childs, D. F. Young, T. S. Carlos, N. Stock, S. Goodbourn, and R. E. Randall. 2004. The V proteins of paramyxoviruses bind the IFN-inducible RNA helicase, MDA-5, and inhibit its activation of the IFN-beta promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10117264-17269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bania, J., E. Gatti, H. Lelouard, A. David, F. Cappello, E. Weber, V. Camosseto, and P. Pierre. 2003. Human cathepsin S, but not cathepsin L, degrades efficiently MHC class II-associated invariant chain in nonprofessional APCs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1006664-6669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behera, A. K., M. Kumar, R. F. Lockey, and S. S. Mohapatra. 2002. 2′-5′ Oligoadenylate synthetase plays a critical role in interferon-gamma inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus infection of human epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 27725601-25608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Browne, E. P., and T. Shenk. 2003. Human cytomegalovirus UL83-coded pp65 virion protein inhibits antiviral gene expression in infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10011439-11444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter, C. C., V. Y. Gorbacheva, and D. J. Vestal. 2005. Inhibition of VSV and EMCV replication by the interferon-induced GTPase, mGBP-2: differential requirement for wild-type GTP binding domain. Arch. Virol. 1501213-1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chebath, J., P. Benech, M. Revel, and M. Vigneron. 1987. Constitutive expression of (2′-5′) oligo A synthetase confers resistance to picornavirus infection. Nature 330587-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke, P., S. M. Meintzer, S. Gibson, C. Widmann, T. P. Garrington, G. L. Johnson, and K. L. Tyler. 2000. Reovirus-induced apoptosis is mediated by TRAIL. J. Virol. 748135-8139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cretney, E., K. Takeda, H. Yagita, M. Glaccum, J. J. Peschon, and M. J. Smyth. 2002. Increased susceptibility to tumor initiation and metastasis in TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 1681356-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crowder, C., O. Dahle, R. E. Davis, O. S. Gabrielsen, and S. Rudikoff. 2005. PML mediates IFN-alpha-induced apoptosis in myeloma by regulating TRAIL induction. Blood 1051280-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Der, S. D., A. Zhou, B. R. Williams, and R. H. Silverman. 1998. Identification of genes differentially regulated by interferon alpha, beta, or gamma using oligonucleotide arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9515623-15628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehrt, S., D. Schnappinger, S. Bekiranov, J. Drenkow, S. Shi, T. R. Gingeras, T. Gaasterland, G. Schoolnik, and C. Nathan. 2001. Reprogramming of the macrophage transcriptome in response to interferon-gamma and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: signaling roles of nitric oxide synthase-2 and phagocyte oxidase. J. Exp. Med. 1941123-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eidson, K. M., W. E. Hobbs, B. J. Manning, P. Carlson, and N. A. DeLuca. 2002. Expression of herpes simplex virus ICP0 inhibits the induction of interferon-stimulated genes by viral infection. J. Virol. 762180-2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Espert, L., G. Degols, C. Gongora, D. Blondel, B. R. Williams, R. H. Silverman, and N. Mechti. 2003. ISG20, a new interferon-induced RNase specific for single-stranded RNA, defines an alternative antiviral pathway against RNA genomic viruses. J. Biol. Chem. 27816151-16158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espert, L., G. Degols, Y. L. Lin, T. Vincent, M. Benkirane, and N. Mechti. 2005. Interferon-induced exonuclease ISG20 exhibits an antiviral activity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Gen. Virol. 862221-2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Everett, R. D., S. Rechter, P. Papior, N. Tavalai, T. Stamminger, and A. Orr. 2006. PML contributes to a cellular mechanism of repression of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection that is inactivated by ICP0. J. Virol. 807995-8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frese, M., G. Kochs, H. Feldmann, C. Hertkorn, and O. Haller. 1996. Inhibition of bunyaviruses, phleboviruses, and hantaviruses by human MxA protein. J. Virol. 70915-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Sastre, A., and C. A. Biron. 2006. Type 1 interferons and the virus-host relationship: a lesson in detente. Science 312879-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gongora, C., G. David, L. Pintard, C. Tissot, T. D. Hua, A. Dejean, and N. Mechti. 1997. Molecular cloning of a new interferon-induced PML nuclear body-associated protein. J. Biol. Chem. 27219457-19463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haller, O., G. Kochs, and F. Weber. 2006. The interferon response circuit: induction and suppression by pathogenic viruses. Virology 344119-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honda, K., H. Yanai, H. Negishi, M. Asagiri, M. Sato, T. Mizutani, N. Shimada, Y. Ohba, A. Takaoka, N. Yoshida, and T. Taniguchi. 2005. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature 434772-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kajaste-Rudnitski, A., T. Mashimo, M. P. Frenkiel, J. L. Guenet, M. Lucas, and P. Despres. 2006. The 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase 1b is a potent inhibitor of West Nile virus replication inside infected cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2814624-4637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang, D. C., R. V. Gopalkrishnan, L. Lin, A. Randolph, K. Valerie, S. Pestka, and P. B. Fisher. 2004. Expression analysis and genomic characterization of human melanoma differentiation associated gene-5, mda-5: a novel type I interferon-responsive apoptosis-inducing gene. Oncogene 231789-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kato, H., O. Takeuchi, S. Sato, M. Yoneyama, M. Yamamoto, K. Matsui, S. Uematsu, A. Jung, T. Kawai, K. J. Ishii, O. Yamaguchi, K. Otsu, T. Tsujimura, C. S. Koh, C. Reis e Sousa, Y. Matsuura, T. Fujita, and S. Akira. 2006. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature 441101-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotelkin, A., E. A. Prikhod'ko, J. I. Cohen, P. L. Collins, and A. Bukreyev. 2003. Respiratory syncytial virus infection sensitizes cells to apoptosis mediated by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. J. Virol. 779156-9172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroger, A., M. Koster, K. Schroeder, H. Hauser, and P. P. Mueller. 2002. Activities of IRF-1. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 225-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larkin, J., L. Jin, M. Farmen, D. Venable, Y. Huang, S. L. Tan, and J. I. Glass. 2003. Synergistic antiviral activity of human interferon combinations in the hepatitis C virus replicon system. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 23247-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leib, D. A. 2002. Counteraction of interferon-induced antiviral responses by herpes simplex viruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 269171-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lenschow, D. J., C. Lai, N. Frias-Staheli, N. V. Giannakopoulos, A. Lutz, T. Wolff, A. Osiak, B. Levine, R. E. Schmidt, A. Garcia-Sastre, D. A. Leib, A. Pekosz, K. P. Knobeloch, I. Horak, and H. W. t. Virgin. 2007. IFN-stimulated gene 15 functions as a critical antiviral molecule against influenza, herpes, and Sindbis viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1041371-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin, R., R. S. Noyce, S. E. Collins, R. D. Everett, and K. L. Mossman. 2004. The herpes simplex virus ICP0 RING finger domain inhibits IRF3- and IRF7-mediated activation of interferon-stimulated genes. J. Virol. 781675-1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, Y. J. 2005. IPC: professional type 1 interferon-producing cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23275-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lum, J. J., A. A. Pilon, J. Sanchez-Dardon, B. N. Phenix, J. E. Kim, J. Mihowich, K. Jamison, N. Hawley-Foss, D. H. Lynch, and A. D. Badley. 2001. Induction of cell death in human immunodeficiency virus-infected macrophages and resting memory CD4 T cells by TRAIL/Apo2l. J. Virol. 7511128-11136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lund, J. M., M. M. Linehan, N. Iijima, and A. Iwasaki. 2006. Cutting edge: plasmacytoid dendritic cells provide innate immune protection against mucosal viral infection in situ. J. Immunol. 1777510-7514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacMicking, J. D. 2004. IFN-inducible GTPases and immunity to intracellular pathogens. Trends Immunol. 25601-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsuda, T., A. Almasan, M. Tomita, K. Tamaki, M. Saito, M. Tadano, H. Yagita, T. Ohta, and N. Mori. 2005. Dengue virus-induced apoptosis in hepatic cells is partly mediated by Apo2 ligand/tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. J. Gen. Virol. 861055-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38.Melroe, G. T., N. A. DeLuca, and D. M. Knipe. 2004. Herpes simplex virus 1 has multiple mechanisms for blocking virus-induced interferon production. J. Virol. 788411-8420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milush, J. M., K. Stefano-Cole, K. Schmidt, A. Durudas, I. Pandrea, and D. L. Sodora. 2007. Mucosal innate immune response associated with a timely humoral immune response and slower disease progression following oral transmission of SIV in rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 816175-6186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mossman, K. L., H. A. Saffran, and J. R. Smiley. 2000. Herpes simplex virus ICP0 mutants are hypersensitive to interferon. J. Virol. 742052-2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muller, U., U. Steinhoff, L. F. Reis, S. Hemmi, J. Pavlovic, R. M. Zinkernagel, and M. Aguet. 1994. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science 2641918-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen, L. H., L. Espert, N. Mechti, and D. M. Wilson III. 2001. The human interferon- and estrogen-regulated ISG20/HEM45 gene product degrades single-stranded RNA and DNA in vitro. Biochemistry 407174-7179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicholl, M. J., L. H. Robinson, and C. M. Preston. 2000. Activation of cellular interferon-responsive genes after infection of human cells with herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Gen. Virol. 812215-2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Obojes, K., O. Andres, K. S. Kim, W. Daubener, and J. Schneider-Schaulies. 2005. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase mediates cell type-specific anti-measles virus activity of gamma interferon. J. Virol. 797768-7776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Overall, J. C., Jr., S. L. Spruance, and J. A. Green. 1981. Viral-induced leukocyte interferon in vesicle fluid from lesions of recurrent herpes labialis. J. Infect. Dis. 143543-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pasieka, T. J., T. Baas, V. S. Carter, S. C. Proll, M. G. Katze, and D. A. Leib. 2006. Functional genomic analysis of herpes simplex virus type 1 counteraction of the host innate response. J. Virol. 807600-7612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pavlovic, J., T. Zurcher, O. Haller, and P. Staeheli. 1990. Resistance to influenza virus and vesicular stomatitis virus conferred by expression of human MxA protein. J. Virol. 643370-3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peng, T., T. R. Golub, and D. M. Sabatini. 2002. The immunosuppressant rapamycin mimics a starvation-like signal distinct from amino acid and glucose deprivation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 225575-5584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng, T., S. Kotla, R. E. Bumgarner, and K. E. Gustin. 2006. Human rhinovirus attenuates the type I interferon response by disrupting activation of interferon regulatory factor 3. J. Virol. 805021-5031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 50.Pestka, S., C. D. Krause, and M. R. Walter. 2004. Interferons, interferon-like cytokines, and their receptors. Immunol. Rev. 2028-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pichlmair, A., O. Schulz, C. P. Tan, T. I. Naslund, P. Liljestrom, F. Weber, and C. Reis e Sousa. 2006. RIG-I-mediated antiviral responses to single-stranded RNA bearing 5′-phosphates. Science 314997-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pierce, A. T., J. DeSalvo, T. P. Foster, A. Kosinski, S. K. Weller, and W. P. Halford. 2005. Beta interferon and gamma interferon synergize to block viral DNA and virion synthesis in herpes simplex virus-infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 862421-2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Platanias, L. C. 2005. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5375-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sainz, B., Jr., and W. P. Halford. 2002. Alpha/beta interferon and gamma interferon synergize to inhibit the replication of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 7611541-11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sainz, B., Jr., H. L. LaMarca, R. F. Garry, and C. A. Morris. 2005. Synergistic inhibition of human cytomegalovirus replication by interferon-alpha/beta and interferon-gamma. Virol. J. 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sainz, B., Jr., E. C. Mossel, C. J. Peters, and R. F. Garry. 2004. Interferon-beta and interferon-gamma synergistically inhibit the replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV). Virology 32911-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sanchez, R., and I. Mohr. 2007. Inhibition of cellular 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase by the herpes simplex virus type 1 Us11 protein. J. Virol. 813455-3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schnorr, J. J., S. Schneider-Schaulies, A. Simon-Jodicke, J. Pavlovic, M. A. Horisberger, and V. ter Meulen. 1993. MxA-dependent inhibition of measles virus glycoprotein synthesis in a stably transfected human monocytic cell line. J. Virol. 674760-4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schroder, K., P. J. Hertzog, T. Ravasi, and D. A. Hume. 2004. Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75163-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shaw, M. L., A. Garcia-Sastre, P. Palese, and C. F. Basler. 2004. Nipah virus V and W proteins have a common STAT1-binding domain yet inhibit STAT1 activation from the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments, respectively. J. Virol. 785633-5641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smyth, G. K. 12 February 2004, posting date. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spruance, S. L., J. A. Green, G. Chiu, T. J. Yeh, G. Wenerstrom, and J. C. Overall, Jr. 1982. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex labialis: correlation of vesicle fluid interferon with lesion age and virus titer. Infect. Immun. 36907-910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Staeheli, P., and J. Pavlovic. 1991. Inhibition of vesicular stomatitis virus mRNA synthesis by human MxA protein. J. Virol. 654498-4501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang, S., and W. S. El-Deiry. 2003. TRAIL and apoptosis induction by TNF-family death receptors. Oncogene 228628-8633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wong, J. J., Y. F. Pung, N. S. Sze, and K. C. Chin. 2006. HERC5 is an IFN-induced HECT-type E3 protein ligase that mediates type I IFN-induced ISGylation of protein targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10310735-10740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoneyama, M., M. Kikuchi, T. Natsukawa, N. Shinobu, T. Imaizumi, M. Miyagishi, K. Taira, S. Akira, and T. Fujita. 2004. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat. Immunol. 5730-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yuan, W., and R. M. Krug. 2001. Influenza B virus NS1 protein inhibits conjugation of the interferon (IFN)-induced ubiquitin-like ISG15 protein. EMBO J. 20362-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou, A., B. A. Hassel, and R. H. Silverman. 1993. Expression cloning of 2-5A-dependent RNAase: a uniquely regulated mediator of interferon action. Cell 72753-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu, J., D. M. Koelle, J. Cao, J. Vazquez, M. L. Huang, F. Hladik, A. Wald, and L. Corey. 2007. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells accumulate near sensory nerve endings in genital skin during subclinical HSV-2 reactivation. J. Exp. Med. 204595-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.