Abstract

A genome-wide screen for Saccharomyces cerevisiae iron-sulfur (Fe/S) cluster assembly mutants identified the gene IBA57. The encoded protein Iba57p is located in the mitochondrial matrix and is essential for mitochondrial DNA maintenance. The growth phenotypes of an iba57Δ mutant and extensive functional studies in vivo and in vitro indicate a specific role for Iba57p in the maturation of mitochondrial aconitase-type and radical SAM Fe/S proteins (biotin and lipoic acid synthases). Maturation of other Fe/S proteins occurred normally in the absence of Iba57p. These observations identify Iba57p as a novel dedicated maturation factor with specificity for a subset of Fe/S proteins. The Iba57p primary sequence is distinct from any known Fe/S assembly factor but is similar to certain tetrahydrofolate-binding enzymes, adding a surprising new function to this protein family. Iba57p physically interacts with the mitochondrial ISC assembly components Isa1p and Isa2p. Since all three proteins are conserved in eukaryotes and bacteria, the specificity of the Iba57/Isa complex may represent a biosynthetic concept that is universally used in nature. In keeping with this idea, the human IBA57 homolog C1orf69 complements the iba57Δ growth defects, demonstrating its conserved function throughout the eukaryotic kingdom.

Iron-sulfur (Fe/S) cluster-containing proteins perform central tasks in electron transport, catalysis, and the regulation of environmental responses (1). The complex bacterial biosynthetic systems that assist in the assembly of Fe/S clusters and their transfer into apo-proteins fall into three classes: the house-keeping ISC system, which is widely distributed across taxa; the NIF machinery dedicated to the assembly of the Fe/S clusters of nitrogenase from nitrogen-fixing bacteria; and the SUF machinery, which is required under oxidative stress and iron-limiting conditions (17, 30).

In eukaryotes mitochondria are crucial for Fe/S protein biogenesis and contain an Fe/S cluster assembly machinery that is closely related to the bacterial ISC system. This mitochondrial ISC machinery appears to be essential for maturation of all cellular Fe/S proteins, whether located in the mitochondria, cytosol, or nucleus (37, 38). Biosynthesis of extramitochondrial Fe/S proteins further depends on the mitochondrial “ISC export machinery” that exports an unknown component required for maturation of cytosolic and nuclear proteins, a step carried out by members of the cytosolic Fe/S protein assembly (CIA) system (37, 38). The ISC and CIA proteins involved in Fe/S maturation are highly conserved in eukaryotes and several are essential for viability, underscoring the importance of Fe/S proteins for the eukaryotic cell.

Fe/S cluster assembly in mitochondria is initiated by the cysteine desulfurase Nfs1p which serves as the sulfur donor (32). The sulfur is transferred to the essential protein pair Isu1p/Isu2p, which serves as a scaffold for the de novo synthesis of the Fe/S clusters (24, 53). This biosynthetic reaction involves an electron transfer chain consisting of the ferredoxin reductase Arh1p and the ferredoxin Yah1p (34, 36). In addition, the Isu proteins interact with frataxin (Yfh1p), which may serve as an iron donor (20, 23, 63). Transfer of the Fe/S clusters from Isu1p/Isu2p to recipient apo-proteins is facilitated by the Hsp70 chaperone Ssq1p, its cognate J-type cochaperone Jac1p, and the monothiol glutaredoxin Grx5p (16, 44, 60).

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, ISA1 and ISA2 encode members of the mitochondrial ISC assembly machinery related to IscA and SufA of bacteria (29, 31, 48). The Isa proteins are specifically required for the maturation of mitochondrial aconitase-type Fe/S proteins and for function of biotin synthase, a radical-SAM Fe/S protein that catalyzes the insertion of sulfur into desthiobiotin (45) (U. Mühlenhoff et al., in preparation). Assembly of other cellular iron sulfur proteins is unaffected by the lack of Isa1p and Isa2p.

We have identified here a novel member of the mitochondrial ISC assembly system, which we have designated Iba57p. Unlike most other members of the ISC assembly machinery, Iba57p is not a general assembly factor but shows specificity for maturation of the Fe/S clusters of aconitase and homoaconitase, as well as for the catalytic function of the radical-SAM Fe/S proteins biotin synthase and lipoic acid synthase. Iba57p physically interacts with the ISC proteins Isa1p and Isa2p, and the respective deletion mutants display similar phenotypes, suggesting that the complex of these three proteins forms the functional unit. Iba57p may perform a similar function in humans, since expression of the human homolog complemented the growth defects of an iba57 mutant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Yeast strains used in the present study are listed in Table 1. Cells were cultivated in rich medium (YP) or minimal medium supplemented with amino acids as required (SC) and 2% (wt/vol) glucose (YPD, SD), unless otherwise indicated (54). Iron-depleted (42) or biotin-free minimal media were prepared by using yeast nitrogen base without FeCl3 or biotin (ForMedium). Cells grown anaerobically were supplemented with 0.2% Tween 80 and 25 μg of ergosterol/ml. Gal-IBA57 strains were grown in SC glucose for at least 40 h to deplete Iba57p to critical levels.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in the present study

| Strain | Genotype | Method of generation | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| W303-1A | MATaura3-1 ade2-1 trp1-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 | 43 | |

| S288C | MATα | 43 | |

| BY4742 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | 5 | |

| BY4743 | MATa/MATα his3Δ1/his3Δ1 leu2Δ0/leu2Δ0 met15Δ0/MET15 LYS2/lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0 | 5 | |

| Gal-ISA1 | W303-1A pISA1::GAL1-10-HIS3 | PCR fragment (pFA6a-HIS3-Gal) | 45 |

| Gal-ISA2 | W303-1A pISA2::GAL1-10-LEU2 | Gene replacement (pYEP51-Gal-ISA2) | 48 |

| Gal-IBA57 | W303-1A pIBA57::GALL-natNT2 | PCR fragment (pYM-N27) | 28; this study |

| Gal-IBA57-Myc | W303-1A pIBA57::GALL-natNT2 IBA57-9Myc-HIS3 | PCR fragment (pYM19) | 28; this study |

| Gal-ISU1 Δisu2 | W303-1A pISU1::GAL1-10-HIS3 isu2::LEU2 | PCR fragment (pFA6a-HIS3-Gal, pUG73) | 23, 26 |

| Gal-GRX5 | W303-1A pGRX5::GAL1-10-HIS3 | PCR fragment (pFA6a-HIS3-Gal) | 44 |

| aco1Δ | W303-1A aco1::HIS3 | PCR Fragment (pFA6a-HIS3MX6) | A. Hausmann, B. Samans, R. Lill, and U. Muhlenhoff, unpublished data |

| bio2Δ | W303-1A bio2-F318 | EMS mutagenesis | 45 |

| cyt2Δ | W303-1A cyt2::LEU2 | Gene replacement | 58 |

| isa1Δ | W303-1A isa1::KanMX4 | PCR fragment (pFA6a-KanMX4) | 31 |

| isa1/2Δ | W303-1A isa1::KanMX4 isa2::HIS3 | PCR fragments (pFA6a-HIS3MX6; pFA6a-KanMX4) | 48 |

| W303 iba57Δ | W303-1A yjr122w::KanMX4 | PCR fragment from BY4743, yjr122w::KanMX4 | This study |

| S288C iba57Δ | S288c yjr122w::KanMX4 | PCR fragment from BY4743, yjr122w::KanMX4 | This study |

| BY4742 iba57Δ | BY4742 yjr122w::KanMX4 | 61 | |

| lip5Δ | BY4742 lip5::KanMX4 | 61 | |

| yfh1Δ | W303-1A yfh1::KanMX4 | PCR fragment (pFA6a-KanMX4) | 19 |

| [rho°] tester | Y341 (MATaade5) | Ethidium bromide treatment | This study |

| ser1Δ | BY4742 ser1::KanMX4 | 61 | |

| iba57Δ/ser1Δ | MATaura3 his3 leu2 yjr122W::KanMX4 | Meiotic progeny of ser1Δ × W303-1A iba57Δ | This study |

| isa1Δ/ser1Δ | MATα ura3 his3 leu2 isa1::KanMX4 | Meiotic progeny of ser1Δ × W303-1A isa1Δ | This study |

| aco1Δ/ser1Δ | MATα ura3 ade2-1 his3 leu2 aco1::HIS3 | Meiotic progeny of ser1Δ × W303-1A aco1Δ | This study |

| gcv1/ser1 | MATaleu2-3,13 met2 ser1 gcv1 | 56 |

Plasmids.

Plasmid pIBA57 was constructed from the centromeric vector pRS413 (55) to contain IBA57 under the control of its native promoter. p-huIBA57 plasmids contained codons 26 to 357 (p-huIBA57a) or codon 26 up to the poly(A) tail initiating at nucleotide 1942 from the Invitrogen human cDNA clone IMAGE:4589759 (p-huIBA57b) fused to codons 1 to 40 of the ATPase subunit F1β under the control of the TDH3 promoter of the 2μ plasmid p426GPD (22). p426LIP5-HA harbored LIP5 fused to an hemagglutinin (HA) tag, p426LYS4-HA harbored LYS4 fused to HA, and p426ISA2 harbored ISA2, all in vector p426GPD. The following reporter plasmids have been used previously: p426YAH1-HA and p426BIO2 (44) and pFET3-GFP (51).

Screening of deletion mutants for lysine and glutamate auxotrophies.

The homozygous diploid S. cerevisiae deletion mutant collection (EUROSCARF, Germany) was precultured in liquid SC medium at 30°C without agitation for 3 days and then replicated into SC medium with or without lysine (30 mg/liter). After 3 days of growth at 30°C the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of each strain was recorded, and any strain for which the ratio of growth with or without lysine was greater than 2 was similarly screened for glutamate auxotrophy.

Miscellaneous methods.

The following published methods were used: manipulation of DNA and PCR (52); transformation of yeast cells (25); isolation of yeast mitochondria and postmitochondrial supernatant (14); immunostaining (27); immunoprecipitation of mitochondrial proteins (23), in vivo labeling of yeast cells with 55FeCl (ICN), and immunoprecipitation of Fe/S cluster proteins (32, 42, 44); determination of enzyme activities of alcohol dehydrogenase, citrate synthase, cytochrome oxidase and Leu1p (32), aconitase (15), pyruvate, and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (KDH) (8); electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) (50); determination of the promoter strength of the FET3 gene (51). Cellular lipoic acid contents were determined with a bioassay using Escherichia coli strain JRG33 (7). Prior to analysis, cells were grown on SC medium for 5 days with several passages. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

RESULTS

A genome-wide screen for genes functionally related to ISA1/2 identifies CAF17/IBA57.

Yeast isa1 or isa2 mutants are viable but auxotrophic for both glutamate and lysine due to a specific defect in the maturation of the mitochondrial Fe/S enzymes aconitase and homoaconitase (Mühlenhoff et al., unpublished). We used this unique combination of auxotrophies as a criterion to screen the S. cerevisiae genome-wide deletion strain collection (61).

Twenty-one strains required lysine for growth, including many known lysine auxotrophs (Table 2). Apart from isa1Δ and isa2Δ, the only strain that also required glutamate was caf17Δ (yjr122wΔ). Both auxotrophies of caf17Δ were complemented by a plasmid expressing CAF17 and were not caused by increased oxidative damage to Fe/S clusters, since cells remained auxotrophic under anaerobic conditions (Fig. 1A). CAF17 encodes a protein with sequence homology to a family of tetrahydrofolate (THF)-binding proteins but previously was annotated as a Ccr4-Not complex-associated factor on the basis of unpublished evidence (13). Based on the results described here, we rename the protein Iba57p, for iron-sulfur cluster assembly factor for biotin synthase- and aconitase-like mitochondrial proteins, with a mass of 57 kDa.

TABLE 2.

Genes required for lysine prototrophy

| ORF | Name | Product |

|---|---|---|

| YBR112C | CYC8 | Transcriptional corepressor, acts together with Tup1p |

| YBR189W | RPS9B | Ribosomal protein S9B |

| YBR242W | Hypothetical ORF | |

| YCR084C | TUP1 | General repressor of transcription, forms a complex with Cyc8p |

| YDR027C | VPS54 | Component of the GARP (Golgi-associated retrograde protein) complex |

| YDR034C | LYS14 | Transcriptional activator |

| YDR234W | LYS4 | Homoaconitase |

| YGL154C | LYS5 | Alpha-aminoadipate reductase phosphopantetheinyl transferase |

| YGR037C | ACB1 | Acyl-coenzyme A-binding protein |

| YIL094C | LYS12 | Homo-isocitrate dehydrogenase |

| YIR034C | LYS1 | Saccharopine dehydrogenase |

| YJR104C | SOD1 | Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase |

| YJR122W | CAF17/IBA57 | Ccr4-associated factor 17, iron-sulfur cluster assembly factor for biotin synthase- and aconitase-like mitochondrial proteins, 57 kDa |

| YLL027W | ISA1 | Iron sulfur assembly 1 |

| YML022W | APT1 | Adenine phosphoribosyltransferase |

| YMR135W-A | Hypothetical ORF | |

| YOR140W | SFL1 | Transcription repressor involved in regulation of flocculation |

| YOR369C | RPS12 | Ribosomal protein S12 |

| YPL262W | FUM1 | Fumarase |

| YPR067W | ISA2 | Iron sulfur assembly 2 |

| YPR069C | SPE3 | Putrescine aminopropyltransferase |

FIG. 1.

The mitochondrial matrix protein Iba57p is required for lysine and glutamate prototrophy and mitochondrial genome maintenance. (A) The indicated S. cerevisiae strains either carrying the empty vector pRS413 or plasmid pIBA57 were spotted onto SC plates lacking histidine and containing glutamate or lysine as indicated. The plates were incubated either in air (+O2) or in an anaerobic jar (−O2) for 2 days at 30°C. (B) BY4742 WT and BY4742 iba57Δ cells were each mated with a [rho°] tester strain. Diploid colonies were selected and patched onto rich medium containing either glucose or glycerol. (C) W303-1A WT, iba57Δ, Gal-IBA57, and Gal-IBA57-Myc cells were grown on SC galactose medium lacking both lysine and glutamate. (D) Gal-IBA57-Myc cells expressing Myc-tagged Iba57p from a GalL promoter were grown in rich galactose medium, and mitochondria (Mito) and postmitochondrial supernatant (PMS) were isolated. Immunostaining was performed with antisera raised against the mitochondrial matrix protein Mge1p, the cytosolic 3-phosphoglycerate kinase (Pgk1p) and monoclonal anti-Myc (A14; Santa Cruz). (E) Mitochondria from panel C were either left intact, hypotonically swollen, or lysed with 0.5% Triton X-100 detergent. Each sample was incubated in the presence or absence of 100 μg of proteinase K/ml for 20 min on ice, and the proteinase K was inactivated by using phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (14). The resulting samples were analyzed by immunostaining for the Myc-tag of Iba57p, the mitochondrial intermembrane space protein cytochrome b2 (Cyb2p), the inner membrane protein Tim44p, and the matrix protein Mge1p. (F) Mitochondria from panel C were lysed by sonication, separated by ultracentrifugation into supernatant (SN) and pellet fractions, and analyzed by immunostaining as described above.

Iba57p is localized to the mitochondrial matrix and is required for mtDNA maintenance.

In addition to lysine and glutamate auxotrophies, isa1 and isa2 mutants are respiratory deficient and have a mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) maintenance defect (29, 31, 48). The iba57Δ mutant shared these phenotypes; it did not grow on nonfermentable carbon sources, and the progeny of crosses between the iba57Δ mutant and an mtDNA-deficient ([rho°]) tester strain were also unable to respire (Fig. 1B). Moreover, mtDNA in the iba57Δ strain could not be detected by DAPI staining, and the respiratory defect could not be rescued by the IBA57 expression plasmid (data not shown). Loss of mtDNA was a direct consequence of the iba57 mutation since in backcrosses the mutation marker always segregated with the inability to rescue the [rho°] tester.

Consistent with a mitochondrial function, Iba57p is predicted by Predotar (57) to be targeted to mitochondria (score of 0.82). In order to test this prediction, we constructed the strain Gal-IBA57-Myc, which contained a C-terminally Myc-tagged version of Iba57p under the control of the galactose-inducible GalL promoter (see below). The Myc-tagged Iba57p was functional, as evidenced by the fact that the Gal-IBA57-Myc strain was respiratory competent and prototrophic for lysine and glutamate (Fig. 1C). Immunostaining of mitochondrial and postmitochondrial fractions from the Gal-IBA57-Myc strain with anti-Myc antibodies identified Iba57p in mitochondria (Fig. 1D). The submitochondrial localization of Iba57p-Myc was determined by hypotonic swelling and proteinase K treatment of isolated mitochondria (14). Iba57p-Myc was protected from digestion in both intact and hypotonically swollen mitochondria, being accessible for digestion only after detergent lysis (Fig. 1E). The protein was found in the supernatant fraction of mitochondrial extracts, indicating that Iba57p is a soluble mitochondrial matrix protein colocalizing with Mge1p (Fig. 1F).

Depletion of Iba57p decreases de novo Fe/S cluster assembly on aconitase and homoaconitase.

Given the similarity of phenotypes between iba57, isa1, and isa2 strains, we tested whether iba57 mutants also have a maturation defect for aconitase-type Fe/S proteins. Consistent with this, cell extracts from the iba57Δ strain showed virtually no aconitase activity (Fig. 2A). To exclude any nonspecific effects of the mtDNA loss in iba57Δ cells, we constructed a strain that carries a glucose-repressible, galactose-inducible version of IBA57 (Gal-IBA57) by replacing the native promoter. Immunostaining for the Myc-tagged version of Iba57p (strain Gal-IBA57-Myc) demonstrated that a 40-h depletion was sufficient to decrease Iba57p-Myc to levels below the detection limit of immunoblots (Fig. 2B). This strain did not lose its mtDNA even after 5 days of depletion on glucose medium (not shown).

FIG. 2.

Depletion of Iba57p results in diminished de novo Fe/S cluster formation on aconitase. (A) Whole-cell extracts from the indicated strains grown overnight in SC medium were assayed for activities of aconitase, cytochrome c oxidase, and alcohol dehydrogenase. Gal-IBA57 and Gal-IBA57-Myc strains were depleted of Iba57p by growth in SC glucose medium for 40 h prior to analysis. (B) Gal-IBA57-Myc cells were grown in SC medium containing either galactose (Gal) or glucose (Glc), and Mge1p and Iba57p-Myc were detected by immunostaining. (C) W303-1A (WT), Iba57p-depleted Gal-IBA57, iba57Δ, and aco1Δ cells were grown overnight in iron-poor SD medium. Cells were labeled with 10 μCi of 55Fe for 2 h, and Aco1p was immunoprecipitated from crude extracts with polyclonal antiserum. The amount of coimmunoprecipitated radioactivity was quantified by scintillation counting, and the total amount of Aco1p was assessed by immunostaining. Por1p was used as a loading control. (D) Mitochondria were isolated from W303-1A (WT) and iba57Δ cells grown in rich glucose medium, and Aco1p and Mge1p were detected by immunostaining. (E) Mitochondria from WT and iba57Δ cells were lysed by sonication and separated into supernatant (SN) and pellet fractions by ultracentrifugation. The fractions were analyzed by immunostaining of the indicated proteins. (F) Mitochondria from the indicated strains corresponding to 1 mg of protein each were lysed in buffer containing 0.1% dodecyl-maltoside and 0.6 mM H2O2 and frozen in liquid helium, and EPR spectra were recorded at 10K (EPR conditions: microwave power, 2 mW; microwave frequency, 9.46 GHz; modulation amplitude, 1.25 mT; modulation frequency, 100 kHz).

Depletion of Iba57p in the Gal-IBA57 strain decreased the aconitase activity to less than a third of wild-type (WT) levels, while alcohol dehydrogenase and cytochrome c oxidase activities were unaffected, indicating that this was indeed a specific defect (Fig. 2A). In order to determine whether the loss of aconitase (Aco1p) activity was due to the absence of the Fe/S cluster, 55Fe incorporation into Aco1p was investigated in vivo. Cells were grown in SD medium for 24 h and then in iron-poor SD medium for 16 h to deplete Iba57p in the Gal-IBA57 strain to critical levels. Cells were radiolabeled with 55Fe for 2 h, whole-cell lysates were prepared, and Aco1p was immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies. 55Fe bound to the immunobeads reflects the amount of de novo Fe/S cluster assembly on Aco1p and was quantified by scintillation counting. Fe/S cluster insertion into Aco1p was impaired approximately threefold in glucose-repressed Gal-IBA57 cells and more than fourfold in iba57Δ (Fig. 2C). Since the amount of Aco1p in Gal-IBA57 cells was comparable to that in WT cells, this indicated a specific Fe/S cluster assembly defect (Fig. 2C). A slight decrease of Aco1p levels was observed in iba57Δ cell extracts. In contrast, mitochondria isolated from iba57Δ cells showed 10-fold-increased levels of Aco1p compared to the WT (Fig. 2D). The bulk of Aco1p in iba57Δ mitochondria was insoluble, cofractioning predominantly with mitochondrial membrane proteins and the chaperonin Hsp60p, which also aggregated under these conditions (Fig. 2E). Together, these findings suggest that loss of Iba57p results in increased levels of apo-Aco1p which is known to bind to Hsp60p during its folding and maturation cycle (9).

As an independent method for detection of the Fe/S cluster on Aco1p in iba57Δ cells, we used EPR spectroscopy of isolated mitochondria. A strong EPR signal at g = 2.03 was observed in WT organelles upon oxidation with H2O2 (Fig. 2F). This signal corresponds to the oxidized [3Fe/4S]+ cluster of aconitase, and no corresponding signal was observed for the aco1Δ strain. The signal was more than 10-fold lower in the Gal-IBA57 strain and was completely absent in the iba57Δ strain, irrespective of whether the samples were treated with H2O2 or not. These data demonstrate that the Fe/S cofactor of aconitase is absent in cells with low levels of Iba57p.

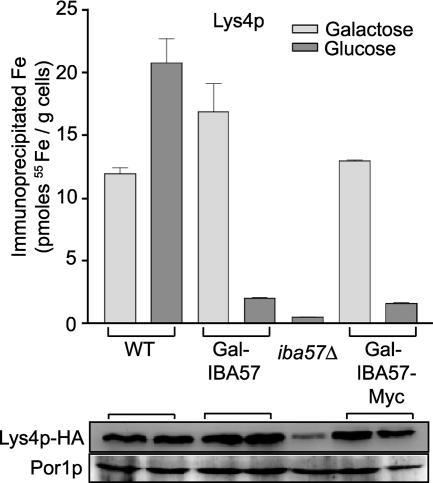

We next investigated whether the lysine auxotrophy of iba57Δ cells was caused by diminished Fe/S cluster formation on the Aco1p relative homoaconitase (Lys4p). In vivo incorporation of 55Fe into Lys4p was analyzed in cells transformed with a reporter plasmid encoding Lys4p with a C-terminal HA tag. The cells were grown in SC medium under inducing or repressing conditions, and 55Fe incorporation into Lys4p-HA was assayed. Depletion of Iba57p resulted in a fivefold decrease in 55Fe incorporation into Lys4p-HA for both Gal-IBA57 and Gal-IBA57-Myc cells (Fig. 3). Lys4p-HA protein levels were unaffected in these cells. In the iba57Δ strain 55Fe incorporation into Lys4p-HA was strongly diminished. However, the protein levels of Lys4p-HA were decreased, probably due to degradation of the apoform of this Fe/S protein. We conclude from these data that assembly of the Fe/S cluster of Lys4p is impaired upon Iba57p depletion. Hence, Iba57p appears to be required, along with Isa1p and Isa2p, for de novo Fe/S cluster assembly on mitochondrial aconitase-type Fe/S proteins.

FIG. 3.

Depletion of Iba57p results in diminished de novo Fe/S cluster formation on homoaconitase (Lys4p). The indicated strains carrying p426LYS4-HA were grown in iron-poor SC medium containing the indicated carbon source. Cells were radiolabeled and Lys4p immunoprecipitated with anti-HA (Santa Cruz) immunobeads as described in Fig. 2. Lys4-HA was detected by immunostaining with anti-HA. Por1p was used as a loading control.

Iba57p is not required for Fe/S cluster assembly on mitochondrial Yah1p or cytosolic Leu1p.

Given its involvement in the maturation of aconitase and homoaconitase, does Iba57p play a role in the maturation of other Fe/S proteins, such as the essential ferredoxin Yah1p? 55Fe incorporation into Yah1p occurred independently of Iba57p function, which is consistent with the fact that Iba57p is not essential for cell growth (Fig. 4A). Next, the role of Iba57p in the maturation of cytosolic Fe/S proteins was investigated. Isopropylmalate dehydratase (Leu1p) from the leucine biosynthetic pathway is an aconitase-type Fe/S enzyme located in the cytosol. Deletion of IBA57 did not result in a leucine auxotrophy or a decrease in Leu1p enzyme activity (Fig. 4B and C). 55Fe incorporation into Leu1p was slightly increased upon Iba57p depletion in Gal-IBA57 cells and remained at WT levels in iba57Δ cells, as was found for mitochondrial Yah1p (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, since iba57Δ mutants are viable and prototrophic for methionine, Iba57p is also not needed for the function of the essential cytosolic Fe/S cluster protein Rli1p or for sulfite reductase, which is required for methionine biosynthesis (33).

FIG. 4.

Depletion of Iba57p does not result in diminished de novo Fe/S cluster formation on ferredoxin (Yah1p) or isopropylmalate dehydratase (Leu1p). (A) The indicated strains carrying p426YAH1-HA were grown in iron-poor SD medium. Cells were radiolabeled and Yah1p-HA immunoprecipitated with anti-HA immunobeads (Santa Cruz) as described in Fig. 2. Yah1p was detected by immunostaining with anti-HA. Por1p was used as a loading control. (B) S288c WT and iba57Δ cells were spotted onto minimal medium plates containing only lysine and glutamate and either containing or lacking leucine. (C) W303-1A WT, depleted Gal-IBA57, and iba57Δ cells were grown overnight in glucose minimal medium, and cell lysates were prepared by the glass bead method. The Leu1p activity was assayed immediately. (D) W303-1A (WT), Iba57p-depleted Gal-IBA57, and iba57Δ cells were grown overnight in iron-poor SD medium, and 55Fe binding to Leu1p was analyzed by the radiolabeling and immunoprecipitation assay described in Fig. 2. Leu1p and Por1p were detected with polyclonal antiserum. (E) Indicated strains carrying pFET3-GFP were grown overnight in SD medium supplemented with 200 μM ferric ammonium citrate (iron replete) or 50 μM bathophenanthroline disulfonic acid (iron depleted), and diluted to an OD600 of 0.2. After an additional 4 h of growth the cells were harvested and then resuspended at an OD600 of 1, and the fluorescence emission at 513 nm was determined. Gal strains were depleted of their respective gene product by growth in SD medium.

In S. cerevisiae, disruption of the mitochondrial ISC assembly or export machineries results in the accumulation of iron in mitochondria (32) and the constitutive induction of a set of iron-regulated genes (2, 21, 62). This is because the sensing of iron for this regulation requires a cytosolic signal molecule that is produced and exported by the mitochondrial ISC machineries (10, 51). In iba57 mutants, however, the maturation of cytosolic Fe/S cluster proteins is functional, and therefore iron homeostasis should not be affected. Indeed, the iron-responsive expression of the FET3 promoter in cells depleted of Iba57p, Isa1p, or Isa2p was similar to the WT, in contrast to mutants for the other nonessential ISC members, Yfh1p and Grx5p (Fig. 4E). There was a slightly decreased induction of FET3 in iron-deprived depleted Gal-ISA1 and Gal-ISA2 strains compared to the WT. These cells are likely to be too compromised to display the full response of this promoter assay under iron-limiting conditions. Despite this, FET3 was clearly still iron responsive after depletion of Iba57p, Isa1p, or Isa2p and, since the iba57Δ mutant did not show any significant mitochondrial iron accumulation (not shown), these data demonstrate that the Aft1/2p regulon is not constitutively induced by depletion of Iba57p, Isa1p, or Isa2p. Taken together, these observations demonstrate that Iba57p and Isa1/2p are distinct from all other members of the mitochondrial ISC assembly or export systems in that they are not involved in the maturation of extramitochondrial proteins or the regulation of cellular iron homeostasis.

Iba57p is required for the in vivo function of mitochondrial radical SAM Fe/S proteins.

Isa1p and Isa2p are required for the in vivo function of biotin synthase, which converts desthiobiotin to biotin (45). The iba57Δ mutation also caused a loss of biotin synthase function, as indicated by an inability to use exogenous desthiobiotin in place of biotin (Fig. 5A). To confirm that this desthiobiotin utilization defect is specifically caused by the loss of biotin synthase activity and not by defective desthiobiotin transport into mitochondria, the status of biotinylated proteins in cells lacking Iba57p was examined. Whole-cell extracts of iba57Δ cells were stained with streptavidin in Western blots. Biotinylated proteins such as Arc1p readily bound streptavidin when the cells were cultivated in the presence of desthiobiotin, which indicates that they are linked to biotin or desthiobiotin (Fig. 5B). In cells cultivated without desthiobiotin, these modifications were strongly diminished. The covalent linkage to either biotin or desthiobiotin can be distinguished by washing the streptavidin-stained membranes with free desthiobiotin. This results in a selective loss of staining for desthiobiotinylated proteins, which have a lower affinity for streptavidin than biotinylated proteins (45). Washing with desthiobiotin readily removed streptavidin from Arc1p in cell extracts from iba57Δ or isa1/2Δ, indicating that in these cells, but not in the WT, Arc1p is linked to desthiobiotin instead of biotin. These findings indicate a defect in the synthesis of biotin from desthiobiotin in cells lacking Iba57p.

FIG. 5.

Iba57p is required for the function of but not Fe/S cluster assembly on biotin synthase. (A) The W303-1A (WT), iba57Δ, strain and bio2Δ carrying the empty pRS413 vectors and the iba57Δ strain expressing IBA57 from plasmid pIBA57 were grown overnight in biotin-free SC glucose medium lacking histidine. Each strain was then spotted onto SC glucose plates lacking histidine and biotin and supplemented with either 4 ng of biotin/ml, 50 mU of avidin/ml, or both 50 ng of desthiobiotin/ml and 50 mU of avidin/ml. (B) W303-1A (WT), iba57Δ, and isa1/2Δ cells were grown for 40 h in biotin-free SD medium and then diluted into fresh biotin-free SD medium either with or without 20 μg of desthiobiotin (DTB)/liter and grown for a further 24 h. Cells were harvested, cell lysates were prepared, and Arc1p was detected by immunostaining with peroxidase-linked streptavidin. The blots were developed immediately after decoration with streptavidin-peroxidase or after a subsequent incubation with 2 mM desthiobiotin for 16 h (DTB wash). Por1p served as a loading control. (C) W303-1A (WT), Iba57p-depleted Gal-IBA57, and iba57Δ cells carrying p426BIO2 were grown overnight in iron-poor SD medium, and 55Fe binding to Bio2p was analyzed by radiolabeling and immunoprecipitation as described in Fig. 2. The Bio2p and Por1p levels were determined by immunostaining.

We next investigated whether this effect might be explained by a role of Iba57p in the de novo formation of the Fe/S clusters of biotin synthase. To this end, we analyzed 55Fe incorporation into Bio2p in yeast cells overexpressing BIO2 from a high-copy plasmid. 55Fe incorporation into Bio2p remained at almost WT levels in Iba57p-depleted Gal-IBA57 cells and dropped to only 60% of WT levels in iba57Δ cells, indicating that Iba57p is not essential for Fe/S cluster formation on biotin synthase in vivo (Fig. 5C). Thus, the desthiobiotin utilization defect of iba57Δ cells is caused by a loss of biotin synthase activity rather than by compromised de novo Fe/S cluster incorporation into this protein. Iba57p may thus play a role in the catalytic cycle of biotin synthase, as suggested for Isa1p and Isa2p (45).

Is Iba57p required for activation of other mitochondrial members of the radical-SAM family of Fe/S proteins such as lipoic acid synthase (Lip5p) (18)? This enzyme catalyzes the insertion of sulfur into octanoyl moieties to form the lipoyl group (59). We investigated whether Iba57p, Isa1p, and Isa2p were required for the function of Lip5p by analyzing the three lipoic acid-requiring enzyme complexes in S. cerevisiae: glycine decarboxylase (GDC), pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. Lack of GDC activity results in the inability of ser1 mutants to satisfy their serine requirement with glycine (56). iba57Δ ser1Δ and isa1Δ ser1Δ mutants showed such a glycine-to-serine conversion defect, but aco1Δser1Δ strains did not, indicating a dysfunction of GDC in iba57 and isa1 strains that is independent of mtDNA loss (Fig. 6A). Likewise, PDH and KDH enzyme activities were barely detectable in mitochondria from iba57Δ, isa1/2Δ, and Isa1p-depleted Gal-ISA1 cells (Fig. 6B). This was even more evident after normalization to malate dehydrogenase (MDH) activity in order to correct for secondary effects caused by loss of citric acid cycle function. In contrast, the PDH and KDH activities of aco1Δ cells and the respiratory-deficient strain cyt2Δ were only slightly lower than in WT cells, confirming that the dramatic loss of lipoic acid-dependent enzyme activities is not a secondary phenotype of [rho°] strains. Since all of these enzymes also require several other cofactors, we analyzed the modification status of lipoic acid-containing subunits directly by immunostaining with an anti-lipoic-acid antibody (46). This antibody recognizes three lipoylated proteins in WT and aco1Δ mitochondria, including the E2 subunits of the PDH and KDH complexes (Fig. 6C). In mitochondria from iba57Δ and isa1/2Δ cells, the corresponding proteins were not detected, indicating that these proteins are either in the apoform in these strains or not synthesized at all. In order to distinguish between these possibilities, we estimated the total cellular lipoic acid content by using a microbiological assay that takes advantage of the lipoic acid auxotrophy of E. coli strain JRG33 (7). Extracts from iba57Δ and isa1/2Δ strains contained 3.5- to 9-fold less lipoic acid than the WT, which is similar to lip5Δ cells (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that cells lacking Iba57p, Isa1p, or Isa2p are lipoic acid deficient, most likely due to a defect in lipoic acid synthase.

FIG. 6.

Iba57p is required for the function of but not Fe/S cluster incorporation into lipoic acid synthase. (A) The indicated strains were grown on SD plates containing amino acids as indicated. (B) Mitochondrial extracts were prepared from the indicated strains grown on lipoic acid-free SD medium. KDH and PDH activities were assayed and are presented relative to MDH activity to correct for general mitochondrial enzyme defects. (C) Mitochondrial extracts from panel B were probed with antibodies against Por1p and lipoic acid (46). The latter recognizes the lipoylated forms of the E2 subunits of PDH (lower band) and KDH (upper) and the H-subunit of GDC (Gcv3p). (D) Strains grown for 5 days in SD medium lacking lipoic acid were analyzed for lipoic acid content. (E) The indicated strains were transformed with plasmid p426-LIP5-HA, and 55Fe binding to Lip5p-HA was analyzed by radiolabeling and immunoprecipitation as described in Fig. 3. Lip5p-HA and Mge1p were detected by immunostaining.

The lipoic acid deficiency of Iba57p-deficient cells was not due to impaired de novo Fe/S cluster synthesis on lipoic acid synthase. Rather, slightly increased 55Fe incorporation into overproduced, HA-tagged Lip5p was observed in the absence of Iba57p, Isa1p, or Isa2p compared to the WT (Fig. 6E). In contrast, depletion of the scaffold protein Isu1p by growth of strain Gal-ISU1/isu2Δ in glucose resulted in a significant decrease in the amount of Lip5p-associated 55Fe. These data strongly indicate that the related radical SAM Fe/S enzymes biotin synthase and lipoic acid synthase require Iba57p, Isa1p, and Isa2p for enzymatic function in vivo, but not for de novo incorporation of their Fe/S clusters.

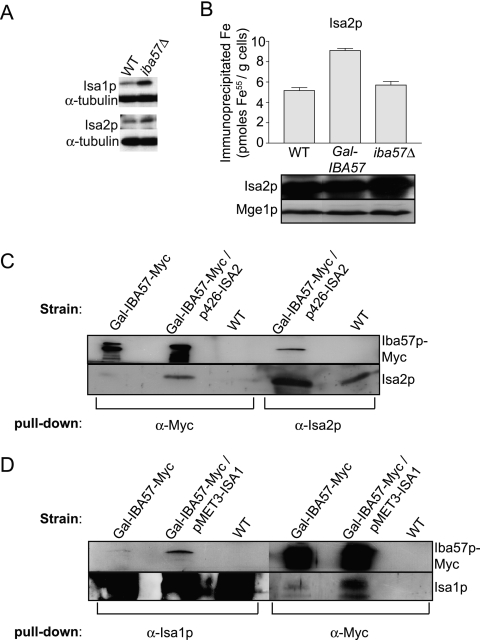

Iba57p interacts with Isa1/Isa2p.

The results presented above demonstrated that depletion of Iba57p had consequences for the cell strikingly similar to those associated with the depletion of Isa1p or Isa2p. The possibility that iba57 strains phenocopy isa1/2 strains by affecting ISA1/ISA2 expression was excluded since the overproduction of plasmid-borne Isa1p or Isa2p did not rescue the auxotrophies of iba57Δ cells (not shown). Further, immunostains of iba57Δ cell lysates showed no decrease of Isa1p or Isa2p levels compared to the WT (Fig. 7A). Isa1p and Isa2p bind iron, a property essential for their function (Mühlenhoff et al., unpublished). Analysis of 55Fe incorporation into Isa2p indicated that Iba57p is not required for iron binding to the Isa proteins (Fig. 7B). We also sought to determine whether Isa1/2p or Iba57p physically interact with aconitase. Although aconitase was insoluble in iba57Δ cells, Isa1p and Isa2p remained soluble (Fig. 2E). Iba57p-Myc could not be coimmunoprecipitated with aconitase antibodies, either from WT or from isa1Δ or isa2Δ cells (not shown), indicating that the Iba57p and the Isa proteins do not form stable complexes with either holo- or apo-aconitase.

FIG. 7.

Iba57p interacts with Isa1p and Isa2p. (A) Cell extracts were prepared from W303-1A and iba57Δ strains grown overnight in YP glucose and immunostained for Isa1p and Isa2p. α-Tubulin (Serotec) served as a loading control. (B) W303-1A WT, depleted Gal-IBA57, and iba57Δ strains were transformed with p426-ISA2 and grown overnight in iron-depleted glucose minimal medium, and 55Fe binding to Isa2p was analyzed by radiolabeling and immunoprecipitation as described in Fig. 3. Leu1p and Mge1p were detected with polyclonal antisera. (C) Mitochondria from WT cells and galactose-induced Gal-IBA57-Myc cells with or without overproduced Isa2p were lysed by detergent, and immunoprecipitations were carried out with antibodies to Isa2p and the Myc tag. The purified immunobeads were analyzed for the presence of Iba57p-Myc and Isa2p by immunostaining. (D) Mitochondria from WT, Gal-IBA57-Myc cells with or without overproduced Isa1p were lysed by detergent, and immunoprecipitations were carried out with antibodies to Isa1p and Myc. The purified immunobeads were analyzed by immunostaining.

We next analyzed whether Iba57p physically interacts with the Isa proteins, which themselves form a stable complex in vivo (Mühlenhoff et al., unpublished). However, because Isa1p and Isa2p are expressed only at low levels, their interaction was not detectable at native expression levels. In order to overcome similar sensitivity problems, coimmunoprecipitations were performed using Gal-IBA57-Myc cells overproducing either Isa2p from the high-copy plasmid p426GPD or Isa1p from the inducible plasmid p414MET3 grown in the presence of galactose. Mitochondria were isolated and lysed with detergent, and immunoprecipitation was carried out with specific antibodies directed against Isa1p, Isa2p, or the Myc epitope. Figure 7C shows that Iba57p-Myc was coisolated with anti-Isa2p antibodies from Gal-IBA57-Myc cells overproducing Isa2p. This interaction was specific, since it was not seen with mitochondria from WT cells lacking Myc-tagged Iba57p. In the converse experiment, Isa2p coimmunoprecipitated with anti-Myc immunobeads from mitochondria of Gal-IBA57-Myc cells overproducing Isa2p. A faint Isa2p-specific band was also detectable after the immunoprecipitation of Iba57p-Myc from mitochondria of Gal-IBA57-Myc cells that contained endogenous Isa2p levels, a finding consistent with a dose-dependent interaction and demonstrating that the interaction is not due to Isa2p overexpression. Again, no immunoprecipitation of Isa2p was observed with anti-Myc antibodies for mitochondria from WT cells. A similar interaction was observed between Isa1p and Iba57p (Fig. 7D). Anti-Myc immunobeads coimmunoprecipitated Isa1p from mitochondria of Gal-IBA57-Myc cells overproducing Isa1p and, conversely, anti-Isa1p immunobeads coimmunoprecipitated Iba57p-Myc from the same strain. Low levels of Isa1p also immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc immunobeads from Gal-IBA57-Myc mitochondria with WT Isa1p levels. No specific immunoprecipitation was seen when WT mitochondria were used. Taken together, these data demonstrate that Iba57p physically interacts with both Isa1p and Isa2p.

Iba57 is functionally conserved between yeast and humans.

The human gene C1orf69 encodes a putative homolog of yeast Iba57p (referred to here as huIba57) that also contains a predicted mitochondrial presequence (Predotar score of 0.59). Despite a low amino acid sequence identity between the yeast and human proteins (22%), the function of Iba57 appears to be conserved, since the lysine and glutamate auxotrophy of iba57Δ cells could be rescued by huIba57 fused to the N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence of the ATPase β-subunit (F1β), although complemented cells grew slightly slower than WT cells (Fig. 8). This suggests that huIba57 performs a function similar to that of its yeast counterpart.

FIG. 8.

Expression of human IBA57 complements the growth defect of iba57Δ cells. iba57Δ cells were transformed with the expression plasmids p-huIBA57a (encoding residues 26 to 357 of huIba57 fused to the mitochondrial targeting sequence of the ATPase subunit F1β) or p-huIBA57b [residue 26 of huIBA57 up to the poly(A) tail initiating at nucleotide 1942 from the Invitrogen human cDNA clone IMAGE:4589759, also fused to F1β]. These cells were grown on SD medium together with WT and iba57Δ cells in the presence or absence of lysine (Lys) and glutamate (Glu).

DISCUSSION

We have identified a novel component of the mitochondrial ISC assembly system, Iba57p (previously termed Caf17p), in a genome-wide screen for S. cerevisiae mutants that carry a coupled lysine and glutamate auxotrophy, which is indicative of defects of aconitase and homoaconitase maturation. Iba57p was demonstrated to be crucial for de novo Fe/S cluster incorporation into these mitochondrial aconitase-type Fe/S proteins. In addition, Iba57p is required for the in vivo enzymatic functions of the mitochondrial radical-SAM Fe/S proteins biotin synthase and lipoic acid synthase. Iba57p interacts with Isa1p and Isa2p, a finding consistent with the virtually identical phenotypes of isa1Δ, isa2Δ and iba57Δ cells (29, 31, 48). No defects in the maturation of other Fe/S proteins were detected in cells depleted for Iba57p or Isa1p/Isa2p (Mühlenhoff et al., unpublished). In addition, the deregulated iron homeostasis that is typical of cells with general defects in the mitochondrial ISC assembly and export systems was not found in cells depleted of Iba57p or Isa1p/Isa2p. These observations strongly indicate that these three proteins are specialized ISC assembly proteins dedicated to the maturation of aconitase-type Fe/S proteins and the functional activation of the radical SAM proteins Bio2p and Lip5p only. The auxotrophies of the isa1/2 and iba57 mutants described here and in earlier investigations can be fully explained by the functional defects in these classes of Fe/S proteins (29, 31, 48). Loss of mtDNA is also observed upon deletion of either LIP5 or ACO1. The lack of involvement in the maturation of essential cytosolic Fe/S proteins can account for why isa1/2 and iba57 mutants are viable, unlike most components of the mitochondrial ISC systems.

Thus, our work on Iba57p and Isa1/2p introduces a novel aspect to our understanding of eukaryotic Fe/S assembly, that of substrate-specific assembly factors, since all previously identified ISC proteins are universally required for mitochondrial Fe/S protein assembly. The complex of Isa1p/Isa2p and Iba57p represents the first example of such a specialized Fe/S protein maturation system in eukaryotes (Mühlenhoff et al., unpublished). This property of Isa1/2p and Iba57p is, however, reminiscent of the substrate specificity of the Isa1/2p ortholog ErpA of E. coli, an essential member of the IscA protein family with a role in isoprenoid synthesis (39). It is possible that this particular class of Fe/S assembly proteins act as specificity factors. It will be interesting to see whether other members of the bacterial IscA family are shown to perform a specific task in Fe/S protein maturation and whether the bacterial Iba57p relative functionally cooperates with this protein family. The dedicated Iba57p/Isa1/2p protein assembly system works in collaboration with the general ISC assembly machinery of mitochondria, distinguishing it from the dedicated NIF system of nitrogen-fixing bacteria which functions as an independent unit. Since our genome-wide screen failed to identify further viable mutants sharing the isa-specific growth defects, most likely there are no further components involved in this specialized assembly task.

Iba57p shows low sequence similarity to aminomethyl transferase of the GDC complex and contains the highly conserved motif KGCY/FXGQE that characterizes a protein family of unknown function (PTHR22602) that is widely represented across eubacterial and eukaryotic taxa. This family includes YgfZ, an E. coli protein whose crystal structure is highly similar to aminomethyl transferase, DMGO, and related THF-binding enzymes, a class of proteins not previously associated with Fe/S cluster maturation. Disruption of YgfZ in E. coli resulted in decreased methylthiolation of N6-isopentenyladenosine (i6A) tRNA (47). This reaction is catalyzed by MiaB, a radical-SAM Fe/S enzyme that likely shares a catalytic mechanism with its relatives biotin synthase and lipoic acid synthase (49). As documented here, enzymatic function of these two proteins require Iba57p and the Isa1p/Isa2p complex. Therefore, the function of Iba57p in the activation of radical SAM proteins may be conserved between bacteria and eukaryotes. In addition, human Iba57 complemented the growth defect of the iba57Δ yeast mutant, suggesting that the function of this protein is also conserved across eukaryotes, including mammals.

Both Isa1p and Isa2p are essential for biotin synthase activity, without being required for de novo synthesis of its Fe/S cofactors (45). Here, we have shown that the same is true for Iba57p. Moreover, Isa1p, Isa2p, and Iba57p are required for lipoic acid biosynthesis, indicating that these proteins are also required for the function of lipoic acid synthase and thus may play a general role in the activation of radical SAM Fe/S proteins. The role of Iba57p and Isa1/2p is restricted to the functional activation of lipoic acid synthase, since the maturation of its Fe/S cofactors is not affected in the absence of each of these proteins. Both biotin synthase and lipoic acid synthase have been suggested to donate sulfur from one of their two Fe/S clusters directly to their substrates (4, 12, 40, 41). Thus, the complex of Isa1p, Isa2p and Iba57p may be involved in the catalytic cycle of sulfur-donating radical-SAM enzymes, probably in the process of Fe/S cluster regeneration after donation of one of the intrinsic sulfide ions to the substrate.

In humans, defects in the mitochondrial branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase complex, which uses lipoic acid as a cofactor, causes maple syrup urine disease or branched-chain ketoaciduria, an autosomal-recessive disease characterized by the accumulation of unprocessed keto acid in blood and urine causing severe ketoacidosis, seizures, and physical and mental retardation (11). Some mutations associated with the disease affect genes encoding the dehydrogenase complex (6); however, not all disease-causing mutations have been identified. Our finding that Isa1p, Isa2p, and Iba57p are required for the last step in lipoic acid biosynthesis in vivo identifies the orthologous human ISA1 and IBA57 genes as candidates for mutations causing maple syrup urine disease.

In summary, we have identified a new member of a group of specialized mitochondrial ISC assembly proteins whose function is confined to the maturation of aconitase-type Fe/S proteins and the activation of mitochondrial radical-SAM Fe/S proteins. These specialized assembly factors are needed in addition to the general members of the ISC assembly apparatus. In the case of radical SAM Fe/S enzymes Iba57p and Isa1/2p act after Fe/S cluster insertion by the general ISC apparatus. A molecular explanation for why aconitase-type and radical SAM Fe/S proteins specifically depend on additional maturation factors will require dedicated in vitro reconstitution of the maturation process using purified proteins. However, it is tempting to speculate that the unifying feature for Iba57p/Isa1/2p requirement may be the presence of a solvent-exposed non-cysteinyl-liganded iron that is sensitive to oxidation, such as that found in aconitases (35). An oxidant-sensitive nonliganded iron is also present in the [4Fe-4S] cluster that binds to the SAM molecule in radical-SAM enzymes (3). In addition, the catalytic [2Fe-2S] cluster of biotin synthase becomes labile after insertion of sulfur into the substrate.

This investigation and our previous studies on Isa1p and Isa2p have comprehensively defined the physiological role of Iba57p and the Isa proteins in the eukaryotic cell and thus extend our model of this biosynthetic process. These insights pave the way for future studies that will unravel the precise mechanisms underlying the molecular function of Iba57p and the Isa proteins in the maturation of mitochondrial aconitases and activation of radical SAM proteins in eukaryotes. It seems likely to us that the bacterial homolog of Iba57p also plays a specific role in Fe/S protein biogenesis that, due to its specialized nature, has thus far escaped identification.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Australian Research Council through Discovery grants to I.W.D. and an Australian Postgraduate Award to C.G. The generous support of R.L. and U.M. by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 593 and TR1, Gottfried-Wilhelm Leibniz program, and GRK 1216), Fonds der chemischen Industrie, and Deutsches Humangenomprojekt is gratefully acknowledged.

We thank Gabriel Perrone for expert advice, Mathew Traini for computer analysis of the deletion mutant screen, Jürgen Stolz for the E. coli strain JRG33, Melissa S. Schonauer for a sample of lipoic acid antibody, and Antonio Pierik for EPR analysis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 December 2007.

We dedicate this paper to the memory of our colleague Ron A. Butow (Dallas, TX).

REFERENCES

- 1.Beinert, H. 2000. Iron-sulfur proteins: ancient structures, still full of surprises. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 52-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belli, G., M. M. Molina, J. Garcia-Martinez, J. E. Perez-Ortin, and E. Herrero. 2004. Saccharomyces cerevisiae glutaredoxin 5-deficient cells subjected to continuous oxidizing conditions are affected in the expression of specific sets of genes. J. Biol. Chem. 27912386-12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkovitch, F., Y. Nicolet, J. T. Wan, J. T. Jarrett, and C. L. Drennan. 2004. Crystal structure of biotin synthase, an S-adenosylmethionine-dependent radical enzyme. Science 30376-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booker, S. J., R. M. Cicchillo, and T. L. Grove. 2007. Self-sacrifice in radical S-adenosylmethionine proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 11543-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brachmann, C. B., A. Davies, G. J. Cost, E. Caputo, J. Li, P. Hieter, and J. D. Boeke. 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14115-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brautigam, C. A., J. L. Chuang, D. R. Tomchick, M. Machius, and D. T. Chuang. 2005. Crystal structure of human dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase: NAD+/NADH binding and the structural basis of disease-causing mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 350543-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brody, S., C. Oh, U. Hoja, and E. Schweizer. 1997. Mitochondrial acyl carrier protein is involved in lipoic acid synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 408217-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, J. P., and R. N. Perham. 1976. Selective inactivation of the transacylase components of the 2-oxo acid dehydrogenase multienzyme complexes of Escherichia coli. Biochem. J. 155419-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhuri, T. K., G. W. Farr, W. A. Fenton, S. Rospert, and A. L. Horwich. 2001. GroEL/GroES-mediated folding of a protein too large to be encapsulated. Cell 107235-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, O. S., R. J. Crisp, M. Valachovic, M. Bard, D. R. Winge, and J. Kaplan. 2004. Transcription of the yeast iron regulon does not respond directly to iron but rather to iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 27929513-29518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chuang, D. T., J. L. Chuang, and R. M. Wynn. 2006. Lessons from genetic disorders of branched-chain amino acid metabolism. J. Nutr. 136243S-249S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cicchillo, R. M., K. H. Lee, C. Baleanu-Gogonea, N. M. Nesbitt, C. Krebs, and S. J. Booker. 2004. Escherichia coli lipoyl synthase binds two distinct [4Fe-4S] clusters per polypeptide. Biochemistry 4311770-11781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark, L. B., P. Viswanathan, G. Quigley, Y.-C. Chiang, J. S. McMahon, G. Yao, J. Chen, A. Nelsbach, and C. L. Denis. 2004. Systematic mutagenesis of the leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain of CCR4 reveals specific sites for binding to CAF1 and a separate critical role for the LRR in CCR4 deadenylase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 27913616-13623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diekert, K., A. I. de Kroon, G. Kispal, and R. Lill. 2001. Isolation and subfractionation of mitochondria from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Cell Biol. 6537-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drapier, J. C., and J. B. Hibbs, Jr. 1996. Aconitases: a class of metalloproteins highly sensitive to nitric oxide synthesis. Methods Enzymol. 26926-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dutkiewicz, R., J. Marszalek, B. Schilke, E. A. Craig, R. Lill, and U. Muhlenhoff. 2006. The hsp70 chaperone ssq1p is dispensable for iron-sulfur cluster formation on the scaffold protein isu1p. J. Biol. Chem. 2817801-7808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fontecave, M., S. O. Choudens, B. Py, and F. Barras. 2005. Mechanisms of iron-sulfur cluster assembly: the SUF machinery. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 10713-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fontecave, M., S. Ollagnier-de-Choudens, and E. Mulliez. 2003. Biological radical sulfur insertion reactions. Chem. Rev. 1032149-2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foury, F. 1999. Low iron concentration and aconitase deficiency in a yeast frataxin homologue deficient strain. FEBS Lett. 456281-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foury, F., A. Pastore, and M. Trincal. 2007. Acidic residues of yeast frataxin have an essential role in Fe-S cluster assembly. EMBO Rep. 8194-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foury, F., and D. Talibi. 2001. Mitochondrial control of iron homeostasis. A genome wide analysis of gene expression in a yeast frataxin-deficient strain. J. Biol. Chem. 2767762-7768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Funk, M., R. Niedenthal, D. Mumberg, K. Brinkmann, V. Ronicke, and T. Henkel. 2002. Vector systems for heterologous expression of proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 350248-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerber, J., U. Muhlenhoff, and R. Lill. 2003. An interaction between frataxin and Isu1/Nfs1 that is crucial for Fe/S cluster synthesis on Isu1. EMBO Rep. 4906-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerber, J., K. Neumann, C. Prohl, U. Muhlenhoff, and R. Lill. 2004. The yeast scaffold proteins Isu1p and Isu2p are required inside mitochondria for maturation of cytosolic Fe/S proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 244848-4857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gietz, R. D., and R. A. Woods. 2002. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 35087-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gueldener, U., J. Heinisch, G. J. Koehler, D. Voss, and J. H. Hegemann. 2002. A second set of loxP marker cassettes for Cre-mediated multiple gene knockouts in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 30e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harlow, E., and D. Land. 1998. Using antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 28.Janke, C., M. M. Magiera, N. Rathfelder, C. Taxis, S. Reber, H. Maekawa, A. Moreno-Borchart, G. Doenges, E. Schwob, E. Schiebel, and M. Knop. 2004. A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast 21947-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen, L. T., and V. C. Culotta. 2000. Role of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ISA1 and ISA2 in Iron Homeostasis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 203918-3927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson, D. C., D. R. Dean, A. D. Smith, and M. K. Johnson. 2005. Structure, function, and formation of biological iron-sulfur clusters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74247-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaut, A., H. Lange, K. Diekert, G. Kispal, and R. Lill. 2000. Isa1p is a component of the mitochondrial machinery for maturation of cellular iron-sulfur proteins and requires conserved cysteine residues for function. J. Biol. Chem. 27515955-15961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kispal, G., P. Csere, C. Prohl, and R. Lill. 1999. The mitochondrial proteins Atm1p and Nfs1p are essential for biogenesis of cytosolic Fe/S proteins. EMBO J. 183981-3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kispal, G., K. Sipos, H. Lange, Z. Fekete, T. Bedekovics, T. Janaky, J. Bassler, D. J. Aguilar Netz, J. Balk, C. Rotte, and R. Lill. 2005. Biogenesis of cytosolic ribosomes requires the essential iron-sulphur protein Rli1p and mitochondria. EMBO J. 24589-598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lange, H., A. Kaut, G. Kispal, and R. Lill. 2000. A mitochondrial ferredoxin is essential for biogenesis of cellular iron-sulfur proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 971050-1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lauble, H., M. C. Kennedy, H. Beinert, and C. D. Stout. 1992. Crystal structures of aconitase with isocitrate and nitroisocitrate bound. Biochemistry 312735-2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, J., S. Saxena, D. Pain, and A. Dancis. 2001. Adrenodoxin reductase homolog (Arh1p) of yeast mitochondria required for iron homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2761503-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lill, R., and U. Muhlenhoff. 2006. Iron-sulfur protein biogenesis in eukaryotes: components and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22457-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lill, R., and U. Muhlenhoff. 2005. Iron-sulfur-protein biogenesis in eukaryotes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30133-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loiseau, L., C. Gerez, M. Bekker, S. Ollagnier-de Choudens, B. Py, Y. Sanakis, J. Teixeira de Mattos, M. Fontecave, and F. Barras. 2007. ErpA, an iron sulfur (Fe S) protein of the A-type essential for respiratory metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Lotierzo, M., B. Tse Sum Bui, D. Florentin, F. Escalettes, and A. Marquet. 2005. Biotin synthase mechanism: an overview. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33820-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller, J. R., R. W. Busby, S. W. Jordan, J. Cheek, T. F. Henshaw, G. W. Ashley, J. B. Broderick, J. E. Cronan, Jr., and M. A. Marletta. 2000. Escherichia coli LipA is a lipoyl synthase: in vitro biosynthesis of lipoylated pyruvate dehydrogenase complex from octanoyl-acyl carrier protein. Biochemistry 3915166-15178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Molik, S., R. Lill, and U. Muhlenhoff. 2007. Methods for studying iron metabolism in yeast mitochondria. Methods Cell Biol. 80261-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mortimer, R. K., and J. R. Johnston. 1986. Genealogy of principal strains of the yeast genetic stock center. Genetics 11335-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muhlenhoff, U., J. Gerber, N. Richhardt, and R. Lill. 2003. Components involved in assembly and dislocation of iron-sulfur clusters on the scaffold protein Isu1p. EMBO J. 224815-4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mühlenhoff, U., M. J. Gerl, B. Flauger, H. M. Pirner, S. Balser, N. Richhardt, R. Lill, and J. Stolz. 2007. The Fe/S assembly proteins Isa1 and Isa2 are required for the function but not for the de novo synthesis of the Fe/S clusters of biotin synthase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 191-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Onder, O., H. Yoon, B. Naumann, M. Hippler, A. Dancis, and F. Daldal. 2006. Modifications of the lipoamide-containing mitochondrial subproteome in a yeast mutant defective in cysteine desulfurase. Mol. Cell Proteomics 51426-1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ote, T., M. Hashimoto, Y. Ikeuchi, M. Su'etsugu, T. Suzuki, T. Katayama, and J. Kato. 2006. Involvement of the Escherichia coli folate-binding protein YgfZ in RNA modification and regulation of chromosomal replication initiation. Mol. Microbiol. 59265-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pelzer, W., U. Muhlenhoff, K. Diekert, K. Siegmund, G. Kispal, and R. Lill. 2000. Mitochondrial Isa2p plays a crucial role in the maturation of cellular iron-sulfur proteins. FEBS Lett. 476134-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pierrel, F., T. Douki, M. Fontecave, and M. Atta. 2004. MiaB protein is a bifunctional radical-S-adenosylmethionine enzyme involved in thiolation and methylation of tRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 27947555-47563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roy, A., N. Solodovnikova, T. Nicholson, W. Antholine, and W. E. Walden. 2003. A novel eukaryotic factor for cytosolic Fe-S cluster assembly. EMBO J. 224826-4835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rutherford, J. C., L. Ojeda, J. Balk, U. Muhlenhoff, R. Lill, and D. R. Winge. 2005. Activation of the iron regulon by the yeast Aft1/Aft2 transcription factors depends on mitochondrial but not cytosolic iron-sulfur protein biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 28010135-10140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russel. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 53.Schilke, B., C. Voisine, H. Beinert, and E. Craig. 1999. Evidence for a conserved system for iron metabolism in the mitochondria of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9610206-10211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sherman, F. 2002. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 3503-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 12219-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sinclair, D. A., and I. W. Dawes. 1995. Genetics of the synthesis of serine from glycine and the utilization of glycine as sole nitrogen source by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1401213-1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Small, I., N. Peeters, F. Legeai, and C. Lurin. 2004. Predotar: a tool for rapidly screening proteomes for N-terminal targeting sequences. Proteomics 41581-1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steiner, H., A. Zollner, A. Haid, W. Neupert, and R. Lill. 1995. Biogenesis of mitochondrial heme lyases in yeast: import and folding in the intermembrane space. J. Biol. Chem. 27022842-22849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sulo, P., and N. C. Martin. 1993. Isolation and characterization of LIP5: a lipoate biosynthetic locus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 26817634-17639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vickery, L. E., and J. R. Cupp-Vickery. 2007. Molecular chaperones HscA/Ssq1 and HscB/Jac1 and their roles in iron-sulfur protein maturation. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 4295-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Winzeler, E. A. 1999. Functional characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285901-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamaguchi-Iwai, Y., R. Stearman, A. Dancis, and R. D. Klausner. 1996. Iron-regulated DNA binding by the AFT1 protein controls the iron regulon in yeast. EMBO J. 153377-3384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoon, T., and J. A. Cowan. 2003. Iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis. characterization of frataxin as an iron donor for assembly of [2Fe-2S] clusters in ISU-type proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1256078-6084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]