Abstract

Circumvention of the host innate immune response is critical for bacterial pathogens to infect and cause disease. Here we demonstrate that the group A Streptococcus (GAS; Streptococcus pyogenes) protease SpyCEP (S. pyogenes cell envelope protease) cleaves granulocyte chemotactic protein 2 (GCP-2) and growth-related oncogene alpha (GROα), two potent chemokines made abundantly in human tonsils. Cleavage of GCP-2 and GROα by SpyCEP abrogated their abilities to prime neutrophils for activation, detrimentally altering the innate immune response. SpyCEP expression is negatively regulated by the signal transduction system CovR/S. Purified recombinant CovR bound the spyCEP gene promoter region in vitro, indicating direct regulation. Immunoreactive SpyCEP protein was present in the culture supernatants of covR/S mutant GAS strains but not in supernatants from wild-type strains. However, wild-type GAS strains do express SpyCEP, where it is localized to the cell wall. Strain MGAS2221, an organism representative of the highly virulent and globally disseminated M1T1 GAS clone, differed significantly from its isogenic spyCEP mutant derivative strain in a mouse soft tissue infection model. Interestingly, and in contrast to previous studies, the isogenic mutant strain generated lesions of larger size than those formed following infection with the parent strain. The data indicate that SpyCEP contributes to GAS virulence in a strain- and disease-dependent manner.

Neutrophils are a major component of the innate immune system and play an essential role in host defense against invading bacterial pathogens. In response to chemokines and/or bacterial products, neutrophils are recruited to the site of an infection, where they kill infecting bacteria through oxygen-dependent and -independent systems (26). Neutrophil-mediated killing predominantly occurs intracellularly following phagocytosis but also extracellularly through the bactericidal activity of neutrophil extracellular traps (3).

The bacterial pathogen group A Streptococcus (GAS; Streptococcus pyogenes) causes many distinct human diseases (6, 21). The most common GAS infections are those of the upper respiratory tract, leading to development of pharyngitis (strep throat). While pharyngeal infections are self-limiting, postinfection sequelae such as acute rheumatic fever may develop if left untreated (6). Occasionally, GAS can cause severe invasive diseases, such as streptococcal toxic shock syndrome and necrotizing fasciitis (“flesh-eating disease”). A common observation of severe necrotizing GAS infections is the paucity of neutrophils at the site of infection (5, 31).

GAS uses several strategies to modulate neutrophil-mediated killing, including inhibition of neutrophil recruitment by degradation of the chemoattractant molecule C5a (16, 32), blockage of opsonization (4), and degradation of neutrophil extracellular traps (28). Recently, GAS was shown to secrete protease activity toward the neutrophil-recruiting chemokine interleukin-8 (IL-8, CXCL8) (14). The IL-8 protease activity of GAS was subsequently identified as belonging to the protein SpyCEP (S. pyogenes cell envelope protease) (9, 15), a protein that is a protective antigen in mice (22). Here, we tested the hypothesis that SpyCEP is an important virulence factor in M1T1 GAS and that human chemokines in addition to IL-8 also serve as SpyCEP substrates. We identified that SpyCEP reduces neutrophil activity through cleavage and inactivation of the human chemokines granulocyte chemotactic protein 2 (GCP-2, CXCL6) and growth-related oncogene alpha (GROα, CXCL1), in addition to the previously reported activity against IL-8 (9, 15). Additionally, we found that an isogenic spyCEP mutant GAS strain generates significantly larger skin lesions than the parental strain in a mouse model of soft tissue infection, data which are at variance with a previous publication (15). As a consequence of chemokine redundancy and tissue-specific production, the discovery that SpyCEP cleaves human chemokines in addition to IL-8 is a key finding and provides an underlying rationale for pathologies observed during human infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of spyCEP isogenic mutant strains.

5005ΔCEP and 2221ΔCEP, isogenic mutants of M1T1 GAS strains MGAS5005 and MGAS2221, were constructed by replacement of the spyCEP gene with a nonpolar spectinomycin resistance cassette (20). A schematic outlining the strategy used to construct the mutant strains is shown in Fig. S1 of the supplemental material and is based upon a previously described method (19). PCR primers used in the construction of the mutant strains were primer A (5′-CCACTAGTTCCTACTCAACAAC-3′), primer B (5′-GTATTCACGAACGAACGAAAATCAACCTATTAAGACCGAAAACGTTCC-3′), primer C (5′-CTATTTAAATAACAGATTAAAAAAATTATAAGGGTCTCAAGTTGCGCATAGTAGG-3′), primer D (5′-GCGGTGCATGAAATAAGTAAAGG-3′), primer SF (5′-GGAACGTTTTCGGTCTTAATAGGTTGATTTTCGTTCGTTCGTGAATAC-3′), and primer SR (5′-CCT ACTATGCGCAACTTGAGACCCTTATAATTTTTTTAATCTGTTATTTA AATAG-3′).

GAS expression microarray analysis.

A custom-made microarray (Affymetrix) was used for expression microarray studies. The array consisted of 25-mer antisense oligonucleotides representing all genes in the MGAS5005 genome, with 16 probe pairs (perfect match [PM] plus mismatch [MM]) per gene. PM probes match gene sequences perfectly, while MM probes are identical in sequence to PM probes with the exception that the central base of each 25-mer probe is substituted. Subtracting MM probe hybridization signal intensity from that of the PM probe reduces background noise, increasing sensitivity. Comparative genome resequencing previously determined that strain MGAS2221 has only 20 genetic changes (single-nucleotide polymorphisms, small insertions and deletions) relative to MGAS5005 (30) and hence can be used with high specificity on our custom array.

Quadruplicate cultures of GAS strains MGAS2221 and 2221ΔCEP were grown at 37°C (5% CO2) in Todd-Hewitt broth with 0.2% yeast extract (THY broth) to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6, corresponding to the mid-exponential phase of growth. Upon harvesting bacteria through centrifugation, RNA was isolated, converted to cDNA, labeled, and hybridized to our custom array as previously described (30). Gene expression estimates were calculated using GCOS software v1.4 (Affymetrix). Data were normalized across samples to minimize discrepancies that can arise due to experimental variables (e.g., probe preparation and hybridization). Genes with expression values below 100 were manually removed from the data, and a two-sample t test (unequal variance) was applied using the statistical package Partek Pro v5.1 (Partek, Inc.).

Western immunoblot analysis of GAS culture supernatant proteins.

SpyCEP preimmune and immune sera were isolated from mice prior to and following immunization with an 864-amino-acid recombinant fragment of SpyCEP (corresponding to amino acids 34 to 897 of the full-length protein) (22), respectively. IL-8, GCP-2, and GROα Western immunoblots were probed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against each antigen (Abcam Inc.). Goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used to detect primary antibody binding and generate signal.

5′ RACE to determine the spyCEP transcription start site.

The 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′ RACE) system (Invitrogen) was used as per the manufacturer's instructions, requiring the spyCEP-specific primers GSP1 (5′-TGATTGCTCTTTTTCAC-3′) and GSP2 (5′-CTTGAGAGTGATTTGTGATGTG-3′). Briefly, DNase-treated total RNA was isolated from GAS strain MGAS2221 as previously described (27). Primer GSP1 was added to 2 μg RNA and used to prime first-strand cDNA synthesis with reverse transcriptase. A poly(C) 3′ tail was added to the cDNA using terminal transferase. Tailed cDNAs were used as the template in a PCR with downstream primer GSP2 (downstream relative to primer GSP1) and a primer that ended with a poly(G) sequence (primer AAP; Invitrogen). AAP primer specificity was assayed through use of control PCRs using untailed cDNA as template. Products were visualized on standard agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. Bands were excised from the gels, TA cloned, and sequenced.

Cloning and purification of CovR.

CovR was amplified by PCR using primers XCOVRF (5′-CCGCCGGAATTCTTTCTGGGAGAAAAAGATAG-3′) and XCOVRR (5′-ACGACATGCATGCCATATGACTTATTTCTCACG-3′). The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and SphI (restriction sites underlined in the above primer sequences) and cloned into similarly digested pBAD30, creating p2221X. pBAD30 is a low-copy-number plasmid that enables arabinose-inducible expression of cloned inserts (13). Overexpression and purification of CovR were essentially as previously described (12). Briefly, Escherichia coli strain LMG194 containing p2221X was grown to an OD600 of 0.6 before inducing CovR expression via addition of 0.2% arabinose. Following 3 h of incubation at 30°C, cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed by French press. Inclusion bodies, which contained approximately 30% of total protein content and 90% of the expressed CovR protein, were solubilized in 6 M guanidinium HCl before dialyzing overnight at 4°C against equilibration buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol). CovR protein was further purified through use of HiTrap heparin and HiTrap Q Sepharose columns (GE Healthcare).

EMSAs.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed using the LightShift chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Pierce) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, unlabeled 210-bp probes spanning the spyCEP promoter region or the non-CovR-regulated gene dnaN were amplified by PCR using primers SPYCEPF (5′-AGGTTTTCGTTTACCCCCCAC-3′), SPYCEPR (5′-GTATTTTCTAAGGGAAAAACG-3′), DNANF (5′-CCAACGTTTAATCACTTTGGAC-3′), and DNANR (5′-AATAAACGGTCTGTATCGGG-3′). Labeled probes were generated using primers of identical sequence but 5′ labeled with biotin (Sigma-Genosys). Reaction mixtures containing 40 pg of labeled probe and various amounts of CovR (10, 5, 2.5, or 0 μM) and unlabeled probe (280, 80, 20, or 0 ng) were constructed using 2× binding buffer [40 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 2 mM CaCl2, 200 μg bovine serum albumin, 20 μg poly(dI·dC), 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 32 mM acetyl phosphate]. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 15 min before loading on 5% Tris-borate-EDTA-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels (Bio-Rad) and running at 100 V for 65 min. DNA was electroblotted to a positively charged nylon membrane (Hybond-N+; GE Healthcare), probed with a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate, and developed.

Isolation of cytoplasmic, cell wall-anchored, and secreted protein fractions.

GAS strains were grown in THY broth to mid-exponential phase (OD600, 0.45). Cytoplasmic protein fractions were isolated by mechanical disruption of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-washed GAS in a glass bead beater (Thermo Bio101), clarification of the cell lysate by centrifugation, and retention of the supernatant for analysis (2). Cell wall-anchored proteins were isolated by washing GAS twice in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and resuspending in a solution containing 1 ml of TE-sucrose buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 20% sucrose), 100 μl of lysozyme (100 mg/ml in TE-sucrose), and 50 μl of mutanolysin (5,000 U/ml in 0.1 M K2HPO4 pH 6.2). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 2 h with end-to-end rotation and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatants were retained (17). Secreted proteins were isolated by addition of 3.5 volumes of ice-cold ethanol to 0.22-μm-filtered GAS culture supernatants and incubated at −20°C for 4 h. Precipitated protein was pelleted through centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, air dried at room temperature for 20 min, and resuspended in water at 1/20 the original culture volume.

Chemokine cleavage assays.

All recombinant chemokine proteins were purchased from Abcam Inc. SpyCEP-mediated chemokine cleavage was assayed in 200-μl reaction mixtures containing 20 nM of recombinant chemokine protein and 188 μl filter-sterilized 16-h culture supernatants from strain MGAS5005 or 5005ΔCEP. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Visualization of chemokine cleavage was attained by silver staining and confirmed by Western immunoblotting with appropriate antibodies. Filtered supernatants of strain MGAS5005 (covS variant) and derivatives rather than strain MGAS2221 (wild type) and its derivatives were used due to the greater concentration of secreted SpyCEP protein in MGAS5005 supernatants (see Fig. 1B and 2A, below).

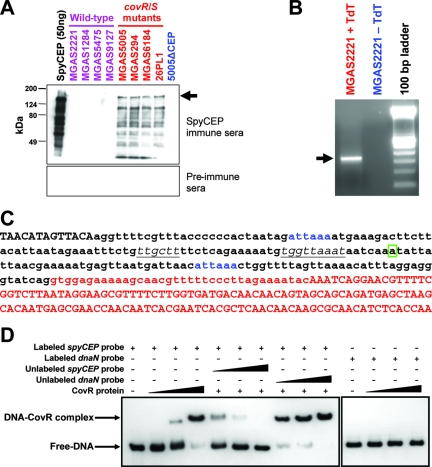

FIG. 1.

Confirmation of spyCEP mutations in the isogenic mutant strains 5005ΔCEP and 2221ΔCEP. (A) Southern blot confirming correct molecular construction of isogenic mutant strains 5005ΔCEP and 2221ΔCEP. Genomic DNA from parent GAS strains MGAS5005 and MGAS2221 and putative spyCEP mutant strains 5005ΔCEP and 2221ΔCEP was digested with NcoI, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to a membrane, and probed with a region of DNA flanking spyCEP. The expected hybridizing fragment size for the parental strains is 4,205 bp, whereas the expected size for a spyCEP mutant strain is 6,674 bp. (B) Western immunoblots confirming the absence of immunoreactive SpyCEP protein in culture supernatants of isogenic mutant strain 5005ΔCEP. Protein was isolated from overnight culture supernatants of parent strains MGAS5005 and MGAS2221 and spyCEP mutant derivatives 5005ΔCEP and 2221ΔCEP. Reactivities with antibodies to SpyCEP, streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A (SpeA), SpeB, streptolysin O (SLO), S. pyogenes NAD-glycohydrolase (SPN), Mac-1-like protein (Mac), and S. pyogenes DNase 3 (Spd3) were determined. Different protein secretion patterns between MGAS5005 and MGAS2221 are attributed to a mutation within covS in strain MGAS5005 encoding the sensor kinase component of the virulence-regulating two-component system CovR/S (30).

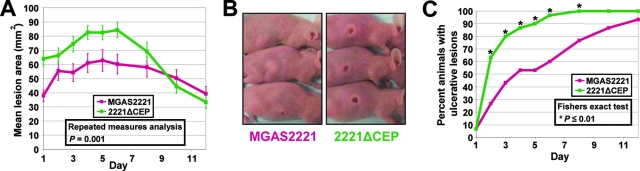

FIG. 2.

spyCEP is regulated directly by the CovR/S two-component system. (A) Enhanced SpyCEP secretion by GAS isolates containing mutations in the two-component signal transduction system covR/S. Protein from 200-μl aliquots of overnight culture supernatants of wild-type (purple) or covR/S mutant (red) GAS strains were concentrated and separated by SDS-PAGE. All strains are clinical isolates with the exception of strain 26PL1, which is an isogenic covS mutant of parental strain MGAS2221 (30). Western immunoblots were probed with mouse preimmune serum or SpyCEP immune serum. Fifty-nanogram aliquots of purified recombinant SpyCEP (black) and supernatant protein from mutant strain 5005ΔCEP (blue) were loaded as positive and negative controls, respectively. The arrow indicates the full-size SpyCEP protein. (B) A single PCR product produced by 5′ RACE of the spyCEP gene. Poly(C)-tailed cDNA (+TdT) created by 5′ RACE gave a single PCR product following separation by agarose gel electrophoresis. The absence of amplification following use of untailed (-TdT) cDNA confirmed the specificity of the amplification reaction. (C) DNA sequence spanning the spyCEP promoter. The 5′ end of the spyCEP gene is labeled red. The transcriptional start site identified by 5′ RACE is boxed. The putative extended −10 and −35 promoter sequences are italicized and underlined. Putative CovR binding sites are blue. Lowercase bases indicate the 210-bp DNA fragment amplified for use in electrophoretic mobility shift assays. (D) CovR binds to the spyCEP promoter region. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays identified that purified CovR binds in a specific manner to the spyCEP promoter, such that CovR can be titrated away from the labeled spyCEP promoter DNA through addition of unlabeled spyCEP promoter DNA but not by addition of identical concentrations of an unrelated chromosomal region (the dnaN gene).

Isolation of human neutrophils.

Neutrophils were isolated from venous blood of healthy individuals as described elsewhere (18). Studies were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Informed consent was obtained from all human subjects. Purified neutrophils were suspended in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) medium buffered with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2 and kept at ambient temperature until used. Purity of neutrophil preparations and viability were assessed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences).

Priming and activation of human neutrophils.

Samples of intact or SpyCEP-cleaved GCP-2 and GROα were created for use in neutrophil priming assays. Supernatant from overnight cultures of strains MGAS5005 and 5005ΔCEP were passed through 100-kDa Centricon columns (Millipore). Proteins remaining in the upper portion of the Centricon columns (proteins of >100 kDa) were retained and incubated with GCP-2 and GROα for 16 h at 37°C, creating the cleaved (reactions using MGAS5005 supernatant) and intact (reactions using 5005ΔCEP supernatant) samples.

To evaluate granule exocytosis, human neutrophils (106) were cultured for 30 min at 37°C in the presence or absence of intact or SpyCEP-cleaved GCP-2 or GROα (each at 10 nM). Neutrophils were washed with blocking buffer (Dulbecco's PBS with 2% goat serum) and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated monoclonal antibody 44 (anti-CD11b; BD Pharmingen) or fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated mouse immunoglobulin G1 (5 μg/ml; BD Pharmingen) for 30 min on ice. Cells were washed twice in blocking buffer, resuspended in blocking buffer containing propidium iodide, and analyzed with a flow cytometer. A single gate was used to eliminate dead cells and debris.

Neutrophil superoxide (O2−) production was measured with a standard assay as described previously (8), but with modifications. Briefly, neutrophils were incubated and primed with intact GCP-2 or GROα (10 nM) or those cleaved by SpyCEP for 30 min at 37°C with gentle agitation. Cells (106) were transferred to 96-well microtiter plates (in triplicate) containing 100 μM ferricytochrome c (Sigma-Aldrich), with or without 40 μg/ml superoxide dismutase (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 μM N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF; Sigma-Aldrich). Absorbance at 550 nm was measured every 20 s for 20 min at 37°C with plate agitation (SpectraMax 384 Plus; Molecular Devices). O2− production was measured as the superoxide dismutase-inhibitable reduction of ferricytochrome c at an absorbance of 550 nm (molar extinction coefficient, 21.1 mM−1 cm−1). The maximum rate of O2− production was determined by using the Vmax over a 2-min time period. Data were analyzed with a repeated-measures analysis of variance and Bonferroni's posttest for multiple comparisons.

Mouse infection assays.

The study protocol was approved by the animal care and use committee of the Methodist Hospital Research Institute. For mouse infection assays, GAS was grown to mid-exponential phase in THY broth and washed twice with PBS. The parental and mutant GAS strains were each used to infect 10 female Crl:SKH10hrBR mice subcutaneously with 100 μl of a 1 × 108/ml suspension of GAS in PBS. The lesion area was determined over a 2-week period. This experiment was performed in triplicate, and the cumulative data that were analyzed are displayed below in Fig. 6A and C. Repeated-measures analysis was used to test for significant differences in lesion areas.

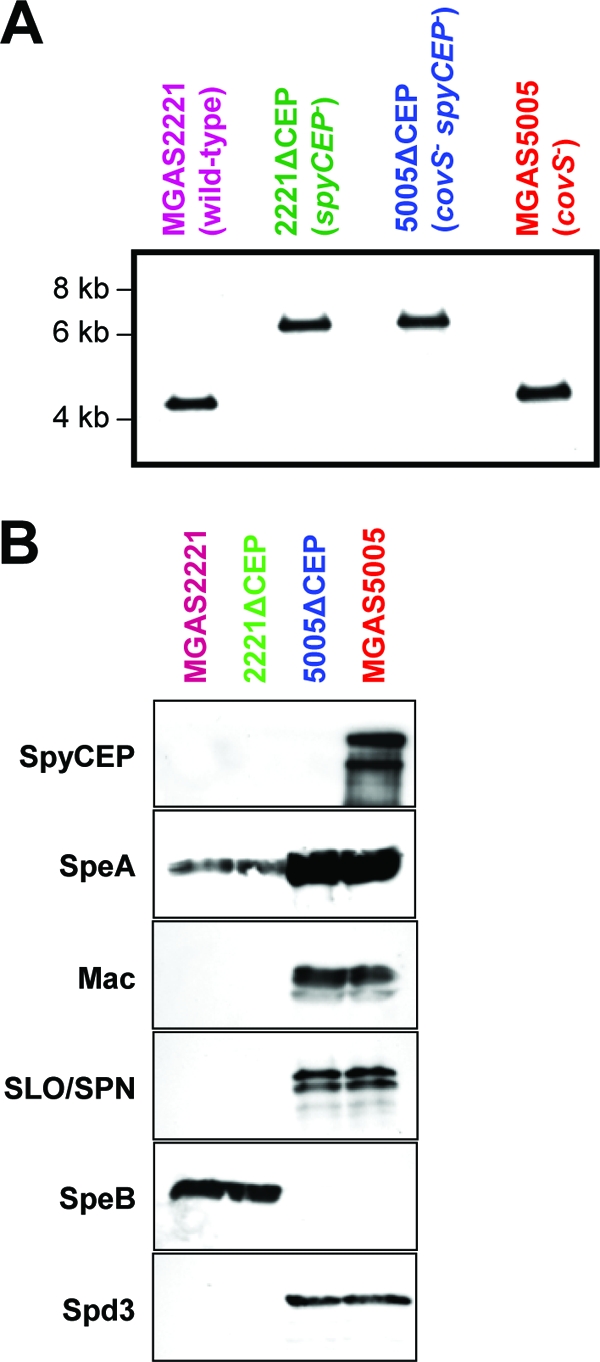

FIG. 6.

SpyCEP contributes to M1T1 GAS mouse pathogenesis. (A) Soft tissue infection model. Data show the mean skin lesion area over time for groups of 30 mice infected subcutaneously with 1 × 107 CFU of either strain MGAS2221 or 2221ΔCEP. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. (B) Photographs of representative mice 2 days after subcutaneous infection with strain MGAS2221 or spyCEP isogenic mutant 2221ΔCEP. (C) Mice infected subcutaneously with spyCEP isogenic mutant strain 2221ΔCEP develop ulcerative lesions at a significantly greater rate than mice infected with parental strain MGAS2221. Asterisks indicate time points of statistical significance.

Microarray data accession number.

Expression microarray data have been deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/geo/) and are accessible through accession number GSE9793.

RESULTS

SpyCEP is highly conserved in different GAS serotypes.

To assess the variability of the SpyCEP protein across different GAS strains, we aligned SpyCEP from the 12 sequenced genomes publicly available (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material; see also information at the URL www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/lproks.cgi) (1). SpyCEP was highly conserved between all strains (>98% identity), which represented nine distinct GAS serotypes. The predicted N-terminal pre-pro domain (amino acids 1 to 123) appears to contain more amino acid substitutions than the remainder of the protein sequence (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Construction and in vitro characterization of isogenic spyCEP mutant strains.

To facilitate testing the hypothesis that SpyCEP contributes to host-pathogen interactions, we constructed two spyCEP mutant strains. Isogenic mutants of GAS strains MGAS5005 and MGAS2221, representatives of the globally disseminated and highly virulent M1T1 GAS clone (29), were constructed by nonpolar deletion mutagenesis, creating 5005ΔCEP and 2221ΔCEP, respectively (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Confirmation of spyCEP replacement with a spectinomycin resistance cassette in strains 5005ΔCEP and 2221ΔCEP was attained via PCR, sequencing, Southern blotting, and Western blot analyses (Fig. 1 and data not shown). The parental and isogenic mutant strains had identical growth curves during culture in THY broth (data not shown).

Despite extensive efforts, we were unable to complement our spyCEP mutant strains. The major impediment to complementation analysis was an inability to clone the full-length spyCEP gene in E. coli. Transformation of ligation reaction products directly into GAS also failed to produce transformants containing the wild-type spyCEP gene, despite previous success with this complementation method for other GAS genes (30).

As complementation was not possible, we performed microarray analysis to compare gene expression between strains MGAS2221 and 2221ΔCEP. We reasoned that if an unwanted spurious mutation occurred during construction of the mutant strain, then the mutant and wild-type strains might differ in transcript profiles. GAS was harvested from quadruplicate exponential-phase THY cultures of each strain, and RNA was isolated and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Expression analysis identified spyCEP as the only gene differentially transcribed (≥2-fold difference in expression with P ≤ 0.05 by t test) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) between the parental and isogenic mutant strains. Thus, these data strongly support the concept that mutant strain 2221ΔCEP lacked spurious mutations.

Mutation of covR/S upregulates SpyCEP protein expression.

Previously, we and others reported that GAS strains with mutations in the genes encoding the two-component signal transduction system CovR/S (also known as CsrR/S) are commonly isolated during infection (10, 30, 33). Furthermore, we identified that spyCEP transcription was upregulated >25-fold by these covR/S mutants (30). To test the hypothesis that the differences observed at the mRNA level correlated with changes at the protein level, we performed Western immunoblot analyses (Fig. 2A). No immunoreactive protein was observed in the secreted protein samples obtained from four GAS strains with wild-type covR/S alleles after probing with SpyCEP-specific immune sera. In comparison, four GAS strains with mutant covR/S alleles secreted immunoreactive protein (Fig. 2A). Strain 26PL1 is an isogenic covS mutant of parental strain MGAS2221, thus confirming CovR/S-mediated regulation of SpyCEP.

Identification and characterization of the spyCEP promoter region.

As an initial step in identifying the spyCEP promoter region, we determined the spyCEP transcriptional start site. A single PCR product was produced by 5′ RACE using total RNA from GAS strain MGAS2221 (Fig. 2B). Sequence analysis of the PCR amplification product identified the transcriptional start site and enabled identification of putative extended −10 (TGGTTAAAT) and −35 (TTGCTT) promoter regions (Fig. 2C). Putative CovR binding sites (consensus sequence ATTARA) (11) were located upstream and downstream of the spyCEP promoter.

To assess whether CovR binds the spyCEP promoter region, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays using E. coli-purified CovR and a 210-bp PCR product encompassing the spyCEP promoter region. CovR bound to the spyCEP promoter in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, CovR binding was specific, as evidenced by a reduction in shifting following addition of unlabeled spyCEP promoter DNA but not after addition of DNA lacking CovR binding sites (dnaN probe).

Investigation into SpyCEP localization at the GAS cell surface.

SpyCEP has a C-terminal LPXTGE motif followed by a hydrophobic region and a positively charged amino acid tail. Such amino acid composition is indicative of a protein maintained at the cell surface through sortase-mediated cell wall anchoring. To test the hypothesis that SpyCEP is localized to the GAS cell wall, cytoplasmic, and secreted protein fractions were isolated from GAS strains MGAS2221, MGAS5005, and 5005ΔCEP. Western immunoblots were used to assay the protein fractions for reactivity to anti-SpyCEP antibodies (Fig. 3). Full-length SpyCEP protein was observed in all protein fractions from strain MGAS5005, whereas no reactivity was observed in the 5005ΔCEP-derived protein samples. Interestingly, wild-type strain MGAS2221 had immunoreactive SpyCEP protein in the cell wall protein fraction. Thus, despite the absence of detectable secreted (in culture supernatant) SpyCEP protein, wild-type M1T1 GAS strains produce SpyCEP, anchoring the protein to the cell wall.

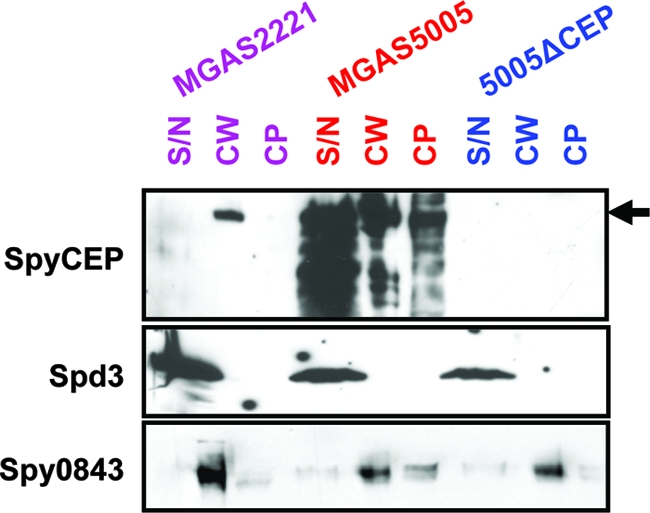

FIG. 3.

SpyCEP can be localized to the GAS cell wall. Fractions corresponding to cytoplasmic (CP), cell wall-anchored (CW), and secreted (SN) proteins were isolated for GAS strains MGAS2221 (wild type; purple), MGAS5005 (covS variant; red), and 5005ΔCEP (spyCEP mutant and covS variant; blue) and subjected to Western immunoblot analyses. All protein fractions from strain MGAS5005 had reactivity to the SpyCEP-specific antiserum. Reactivity to the SpyCEP antiserum was only observed in the cell wall protein fraction of strain MGAS2221 and was absent in all fractions from strain 5005ΔCEP. The secreted protein Spd3 and cell wall-anchored protein Spy0843 were probed as loading controls. Note that due to greater protein concentrations the S/N samples resulted in lanes wider than other lanes. The arrow indicates the full-size SpyCEP protein.

SpyCEP cleaves human tonsillar epithelial cell chemokines GCP-2 and GROα.

In addition to in vitro protease activity against IL-8, SpyCEP also has activity against murine chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), a protein with only 37% amino acid identity to IL-8 (9). Therefore, we hypothesized that human chemokines in addition to IL-8 may also serve as SpyCEP substrates. To this end we assayed whether SpyCEP cleaved human chemokines GCP-2 and GROα in vitro. These chemokines were chosen for analysis due to their abundant expression by tonsillar surface epithelial cells during tonsillitis, which suggests they participate in inflammation (24, 25). In addition, GCP-2 and GROα share similar levels of amino acid identity with IL-8 as MIP-2 (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Furthermore, nine contiguous amino acids spanning the SpyCEP cleavage site in IL-8 and MIP-2 are conserved in GCP-2 and GROα.

IL-8 (positive control), GCP-2, and GROα were added to filtered culture supernatants of strains MGAS5005 and 5005ΔCEP, incubated at 37°C for 4 h, and analyzed by Western immunoblotting (Fig. 4). All three chemokines incubated with the supernatant from mutant strain 5005ΔCEP reacted with polyclonal antibodies against each of the three proteins, whereas no reactivity was observed following incubation with supernatant from the parental MGAS5005 strain. As previously described, SpyCEP cleavage of IL-8 reduces/inhibits reactivity to IL-8 antibodies (9). SpyCEP-cleaved GCP-2 and GROα also failed to react with their respective antibodies (Fig. 4). Thus, the data indicate that the SpyCEP cleavage site in IL-8, GCP-2, and GROα overlaps the major and/or only epitope recognized by the antibodies used in this study.

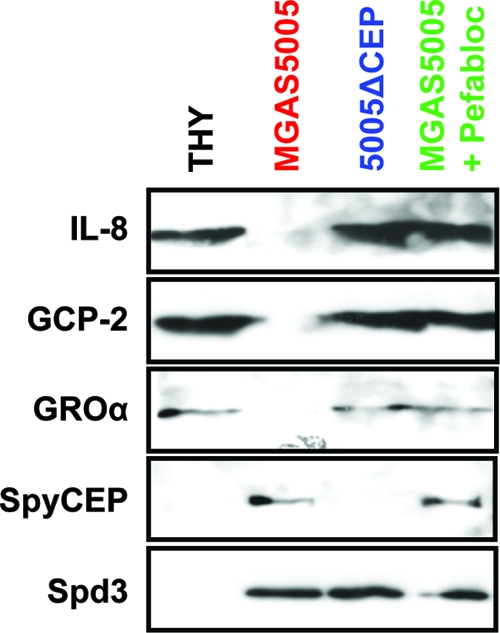

FIG. 4.

SpyCEP cleaves the human chemokines IL-8, GCP-2, and GROα. Recombinant chemokine proteins were incubated with filtered supernatants from strain MGAS5005 (red) and isogenic mutant 5005ΔCEP (blue) before use in Western immunoblot analyses. Supernatant from strain MGAS5005, but not from strain 5005ΔCEP, resulted in the degradation of IL-8, GCP-2, and GROα, as evidenced by the loss of reactivity to polyclonal antibodies. Addition of the SpyCEP inhibitor Pefabloc to MGAS5005 supernatant reaction mixtures inhibited chemokine degradation (green). Incubation of chemokines with sterile THY broth served as a negative control for cleavage (black). Spd3 reactivity was assayed as a control for loading.

Silver-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE gels of chemokine cleavage reaction products confirmed the conversion of full-length chemokines to lower-molecular-weight cleavage products during incubation with supernatant from strain MGAS5005 but not strain 5005ΔCEP (data not shown; see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). The protease inhibitor Pefabloc was previously shown to inhibit SpyCEP activity (9). Addition of Pefabloc to chemokine cleavage reactions inhibited GCP-2 and GROα cleavage (Fig. 4).

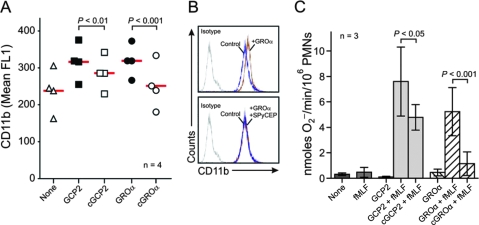

SpyCEP cleavage of GCP-2 and GROα detrimentally alters human neutrophil priming.

We next tested the hypothesis that cleavage of GCP-2 and GROα by SpyCEP abolished the neutrophil priming activity of these chemokines. Neutrophil priming refers to the ability to render neutrophils more responsive to activating agents, such as N-formyl peptides (e.g., N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine [fMLF]) (7). Primed neutrophils have increased expression of the neutrophil cell surface integrin CD11b, and hence measurement of the CD11b concentration is a commonly used indicator of neutrophil priming (23). As SpyCEP has no direct activity on neutrophil priming (9), differences in CD11b expression following addition of chemokines preincubated with MGAS5005 or 5005ΔCEP supernatant proteins would be attributable to chemokine cleavage. CD11b expression was significantly higher for neutrophils coincubated with intact rather than SpyCEP-cleaved GCP-2 or GROα (Fig. 5A). The enhanced ability of intact GCP-2 and GROα to increase neutrophil CD11b expression is apparent from the ability of these chemokines, but not the SpyCEP-cleaved chemokines, to shift the flow cytometry-generated peak of CD11b fluorescence (Fig. 5B). Intact GCP-2 and GROα primed neutrophils for enhanced neutrophil O2− superoxide production following activation with fMLF (Fig. 5C). Consistent with the effects of SpyCEP on chemokine-induced CD11b surface expression, O2− production by fMLF-activated neutrophils was reduced significantly by pretreatment of GCP-2 or GROα with SpyCEP (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

SpyCEP inhibits priming of human neutrophils by GCP-2 and GROα. (A and B) Surface expression of CD11b. Neutrophils were cultured with 10 nM GCP-2 or GROα or those cleaved with SpyCEP (cGCP2 or cGROα). Results are the mean fluorescence (mean FL1) of neutrophils from four separate individuals (each symbol). The red line is the mean. Panel B is from a representative flow cytometry experiment. (C) SpyCEP inhibits priming for fMLF-stimulated neutrophil O2− generation. Human neutrophils were activated by 1 μM fMLF with or without priming by chemokines as indicated. Results are the means ± standard deviations of three separate experiments. Data were analyzed with a repeated-measures analysis of variance and Bonferroni's posttest for multiple comparisons.

Inactivation of the SpyCEP gene alters pathogenesis in a mouse soft tissue infection model.

Previous studies of the role of SpyCEP in host-pathogen interactions have been hampered by the inability to create an isogenic mutant strain in which only the SpyCEP gene was inactivated (15). Thus, to test the hypothesis that SpyCEP production contributes to host-pathogen interactions, M1T1 parental GAS strain MGAS2221 was compared with the isogenic spyCEP mutant strain 2221ΔCEP in a mouse model of soft tissue infection. Mice infected subcutaneously with isogenic mutant strain 2221ΔCEP developed significantly larger lesions than mice infected with parental strain MGAS2221 (Fig. 6A). Additionally, compared to the wild-type parental strain, a significantly greater percentage of mice infected with the isogenic mutant strain formed ulcerative lesions (Fig. 6B and C).

DISCUSSION

GAS is a strictly human pathogen. Exposure of GAS to the human innate immune response presumably has provided the driving force behind evolution of the many GAS immune evasion mechanisms described. Here we add to those immune evasion mechanisms by identifying SpyCEP as a general chemokine protease, capable of inactivating not only IL-8 but also GCP-2 and GROα, two chemokines made abundantly by human tonsillar epithelial cells (14, 25). As a consequence of chemokine redundancy and tissue-specific production, the discovery that SpyCEP cleaves human chemokines other than IL-8 is a key finding, expanding our understanding of the role of SpyCEP in immune evasion.

A common observation from severe invasive GAS infections is a dearth of neutrophils at sites of infection (5, 31). We believe that the relative lack of neutrophils is linked to the spontaneous generation of covR/S mutant GAS strains which occurs during invasive GAS infection (10, 30). Multiple GAS virulence factors are upregulated by covR/S mutant GAS at both RNA and protein levels (30). Similar to several highly regulated genes (e.g., M5005_Spy_0115, the has operon), spyCEP transcription is directly regulated by the CovR/S system, as evidenced by CovR binding to the spyCEP promoter region (Fig. 2D). Here we have shown not only that SpyCEP is expressed at a higher concentration by covR/S mutant GAS strains, but also that the protein displays an altered GAS localization pattern (Fig. 2A and 3). We hypothesize that the occurrence of SpyCEP in the culture supernatant of covR/S mutant GAS is the result of overloading the sortase system responsible for anchoring the protein to the cell wall. Through secretion of high concentrations of SpyCEP, we propose that covR/S mutant GAS protects neighboring wild-type GAS from neutrophil-mediated killing by degrading chemokines. In addition, we hypothesize that the high concentration of secreted SpyCEP protein also serves as an antibody sink, sequestering host antibodies and thus preventing antibody-mediated phagocytosis of GAS with cell surface-bound SpyCEP.

SpyCEP was recently identified as being a mouse protective antigen by Rodríguez-Ortega et al. (22) during a vaccine candidate search of the GAS cell surface proteome. Our observation that different clinical strains of GAS differ widely in their production and localization of SpyCEP augments the findings of Rodríguez-Ortega et al. and may assist vaccine development. The finding that SpyCEP can be cell wall localized has important implications in the context of GAS pathogenesis. Retaining chemokine protease activity at the GAS cell wall would ensure that this activity is immediately available as GAS disseminates within or between hosts. Additionally, cell wall-anchored SpyCEP may enhance upper respiratory tract infectivity by securing the protein at the colonization site despite the continuous flow of saliva.

SpyCEP extracellular localization was first reported by Lei and colleagues, who identified a 31-kDa fragment of SpyCEP in the culture supernatant of the serotype M3 strain MGAS315 (19a). This finding, along with Western immunoblotting data shown here (Fig. 1B, 2A, and 3) and elsewhere (9), supports the hypothesis that SpyCEP is proteolytically processed. While the mechanism by which SpyCEP cleavage occurs is currently unknown, the secreted cysteine protease SpeB does not appear to be involved (9).

Hidalgo-Grass and colleagues reported that an M14 scpA/spyCEP double mutant GAS strain gave smaller skin lesions following mouse subcutaneous injection than an M14 scpA single mutant strain (15). scpA encodes the virulence factor C5a peptidase, which degrades the proinflammatory and neutrophil chemoattractant molecule C5a (16). Thus, we were surprised that the 2221ΔCEP mutant strain gave larger skin lesions than the wild-type parental strain MGAS2221 when used in the same animal model (Fig. 6A). Differences between our data and those of Hidalgo-Grass may be the result of partial functional redundancy between SpyCEP and the C5a peptidase or due to bacterial strain and/or serotype genetic differences. For example, transcriptional regulation of the spyCEP gene differs in the M14 strain background used by Hidalgo-Grass due to the presence of the sil locus, which regulates spyCEP transcription (15). The sil locus is absent in the majority of GAS serotypes causing disease in North America and western Europe, such as the serotype M1 strains described in this study. We hypothesize that the increased lesion size following infection with isogenic mutant strain 2221ΔCEP is the result of increased inflammation and neutrophil infiltration, which is directly related to the inability of 2221ΔCEP to inactivate proinflammatory chemokines. Likewise, we attribute the increased rate of ulcerative lesion formation following infection with 2221ΔCEP to tissue damage caused by cytotoxic molecules (e.g., gelatinase, collagenase, elastase, and reactive oxygen species) released by activated neutrophils at the site of infection (Fig. 5 and 6).

Despite numerous attempts using several different molecular strategies, we were unable to introduce a wild-type copy of spyCEP into our isogenic spyCEP mutant strains and hence were unable to perform genetic complementation analysis. Our efforts included the use of primers and conditions identical to those used by Hidalgo-Grass and colleagues to clone the M14 spyCEP gene (15). It is possible that the minor amino acid differences between the M14 and M1 SpyCEP proteins result in functional differences that account for our inability to clone the M1 spyCEP gene. Data in support of functional differences between M1 and M14 SpyCEP proteins are the observation that Hidalgo-Grass and colleagues were unable to create a spyCEP mutant strain without first mutating scpA, which those authors attributed to functional linkage between the two proteins (15). Mutation of scpA was not required and was not observed in our M1 GAS spyCEP mutant strains, as determined by sequence and expression analyses (data not shown). Despite our inability to complement our isogenic mutant strains, we were able to confirm that spyCEP was the only differentially transcribed gene between wild-type strain MGAS2221 and isogenic mutant strain 2221ΔCEP (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Thus, there is significant evidence that phenotypic variances between parental strain MGAS2221 and isogenic mutant strain 2221ΔCEP are the result of spyCEP inactivation and not other spurious mutations. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that strain 2221ΔCEP may harbor mutations that have no effect on transcript levels but instead alter protein function.

GAS have accrued multiple independent immune defense mechanisms to protect against the human innate immune response. Here we have added to our understanding of one such mechanism, namely, the inactivation of proinflammatory chemokines through cleavage by the secreted and cell wall-anchored GAS protein SpyCEP. We showed that spyCEP transcription is directly regulated by the global virulence-regulating two-component system CovR/S. Furthermore, we have expanded the list of known human substrates of the SpyCEP protein and provided evidence that SpyCEP activity contributes to disease caused by the globally disseminated and highly virulent M1T1 GAS clone. These findings, together with data from Rodríguez-Ortega et al. (22), suggest that SpyCEP may be an important GAS vaccine candidate. Further research is under way to test this hypothesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Siu Chun Michael Ho for help designing Fig. S1 (shown in the supplemental material).

This study was funded in part by NIH grant AI-U01-060595 (J.M.M.) and funds from the NIAID intramural program (F.R.D.).

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 January 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beres, S. B., and J. M. Musser. 2007. Contribution of exogenous genetic elements to the group A Streptococcus metagenome. PLoS ONE 2e800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biswas, I., P. Germon, K. McDade, and J. R. Scott. 2001. Generation and surface localization of intact M protein in Streptococcus pyogenes are dependent on sagA. Infect. Immun. 697029-7038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinkmann, V., U. Reichard, C. Goosmann, B. Fauler, Y. Uhlemann, D. S. Weiss, Y. Weinrauch, and A. Zychlinsky. 2004. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 3031532-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlsson, F., C. Sandin, and G. Lindahl. 2005. Human fibrinogen bound to Streptococcus pyogenes M protein inhibits complement deposition via the classical pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 5628-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cockerill, F. R., III, R. L. Thompson, J. M. Musser, P. M. Schlievert, J. Talbot, K. E. Holley, W. S. Harmsen, D. M. Ilstrup, P. C. Kohner, M. H. Kim, B. Frankfort, J. M. Manahan, J. M. Steckelberg, F. Roberson, W. R. Wilson, et al. 1998. Molecular, serological, and clinical features of 16 consecutive cases of invasive streptococcal disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 261448-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeLeo, F. R., J. Renee, S. McCormick, M. Nakamura, M. Apicella, J. P. Weiss, and W. M. Nauseef. 1998. Neutrophils exposed to bacterial lipopolysaccharide upregulate NADPH oxidase assembly. J. Clin. Investig. 101455-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLeo, F. R., L. A. Allen, M. Apicella, and W. M. Nauseef. 1999. NADPH oxidase activation and assembly during phagocytosis. J. Immunol. 1636732-6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards, R. J., G. W. Taylor, M. Ferguson, S. Murray, N. Rendell, A. Wrigley, Z. Bai, J. Boyle, S. J. Finney, A. Jones, H. H. Russell, C. Turner, J. Cohen, L. Faulkner, and S. Sriskandan. 2005. Specific C-terminal cleavage and inactivation of interleukin-8 by invasive disease isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Infect. Dis. 192783-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engleberg, N. C., A. Heath, A. Miller, C. Rivera, and V. J. DiRita. 2001. Spontaneous mutations in the CsrRS two-component regulatory system of Streptococcus pyogenes result in enhanced virulence in a murine model of skin and soft tissue infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1831043-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federle, M. J., and J. R. Scott. 2002. Identification of binding sites for the group A streptococcal global regulator CovR. Mol. Microbiol. 431161-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gusa, A. A., J. Gao, V. Stringer, G. Churchward, and J. R. Scott. 2006. Phosphorylation of the group A streptococcal CovR response regulator causes dimerization and promoter-specific recruitment by RNA polymerase. J. Bacteriol. 1884620-4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guzman, L. M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose pBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 1774121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hidalgo-Grass, C., M. Dan-Goor, A. Maly, Y. Eran, L. A. Kwinn, V. Nizet, M. Ravins, J. Jaffe, A. Peyser, A. E. Moses, and E. Hanski. 2004. Effect of a bacterial pheromone peptide on host chemokine degradation in group A streptococcal necrotising soft-tissue infections. Lancet 363696-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hidalgo-Grass, C., I. Mishalian, M. Dan-Goor, I. Belotserkovsky, Y. Eran, V. Nizet, A. Peled, and E. Hanski. 2006. A streptococcal protease that degrades CXC chemokines and impairs bacterial clearance from infected tissues. EMBO J. 254628-4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji, Y., L. McLandsborough, A. Kondagunta, and P. P. Cleary. 1996. C5a peptidase alters clearance and trafficking of group A streptococci by infected mice. Infect. Immun. 64503-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji, Y., N. Schnitzler, E. DeMaster, and P. P. Cleary. 1998. Impact of M49, Mrp, Enn, and C5a peptidase proteins on colonization of the mouse oral mucosa by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 665399-5405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi, S. D., J. M. Voyich, C. L. Buhl, R. M. Stahl, and F. R. DeLeo. 2002. Global changes in gene expression by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes during receptor-mediated phagocytosis: cell fate is regulated at the level of gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 996901-6906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuwayama, H., S. Obara, T. Morio, M. Katoh, H. Urushihara, and Y. Tanaka. 2002. PCR-mediated generation of a gene disruption construct without the use of DNA ligase and plasmid vectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 30e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Lei, B., S. Mackie, S. Lukomski, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Identification and immunogenicity of group A Streptococcus culture supernatant proteins. Infect. Immuno. 686807-6818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukomski, S., N. P. Hoe, I. Abdi, J. Rurangirwa, P. Kordari, M. Liu, S. J. Dou, G. G. Adams, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Nonpolar inactivation of the hypervariable streptococcal inhibitor of complement gene (sic) in serotype M1 Streptococcus pyogenes significantly decreases mouse mucosal colonization. Infect. Immun. 68535-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musser, J. M., and R. M. Krause. 1998. The revival of group A streptococcal diseases, with a commentary on staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, p. 185-218. In R. M. Krause (ed.), Emerging infections. Academic Press, New York, NY.

- 22.Rodriguez-Ortega, M. J., N. Norais, G. Bensi, S. Liberatori, S. Capo, M. Mora, M. Scarselli, F. Doro, G. Ferrari, I. Garaguso, T. Maggi, A. Neumann, A. Covre, J. L. Telford, and G. Grandi. 2006. Characterization and identification of vaccine candidate proteins through analysis of the group A Streptococcus surface proteome. Nat. Biotechnol. 24191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rohn, T. T., L. K. Nelson, K. M. Sipes, S. D. Swain, K. L. Jutila, and M. T. Quinn. 1999. Priming of human neutrophils by peroxynitrite: potential role in enhancement of the local inflammatory response. J. Leukoc. Biol. 6559-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudack, C., S. Jorg, and F. Sachse. 2004. Biologically active neutrophil chemokine pattern in tonsillitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 135511-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sachse, F., F. Ahlers, W. Stoll, and C. Rudack. 2005. Neutrophil chemokines in epithelial inflammatory processes of human tonsils. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 140293-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Segal, A. W. 2005. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23197-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shelburne, S. A., III, P. Sumby, I. Sitkiewicz, N. Okorafor, C. Granville, P. Patel, J. Voyich, R. Hull, F. R. DeLeo, and J. M. Musser. 2006. Maltodextrin utilization plays a key role in the ability of group A Streptococcus to colonize the oropharynx. Infect. Immun. 744605-4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sumby, P., K. D. Barbian, D. J. Gardner, A. R. Whitney, D. M. Welty, R. D. Long, J. R. Bailey, M. J. Parnell, N. P. Hoe, G. G. Adams, F. R. DeLeo, and J. M. Musser. 2005. Extracellular deoxyribonuclease made by group A Streptococcus assists pathogenesis by enhancing evasion of the innate immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1021679-1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sumby, P., S. F. Porcella, A. G. Madrigal, K. D. Barbian, K. Virtaneva, S. M. Ricklefs, D. E. Sturdevant, M. R. Graham, J. Vuopio-Varkila, N. P. Hoe, and J. M. Musser. 2005. Evolution and emergence of a highly successful clone of serotype M1 group A Streptococcus involved multiple horizontal gene transfer events. J. Infect. Dis. 192771-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sumby, P., A. R. Whitney, E. A. Graviss, F. R. DeLeo, and J. M. Musser. 2006. Genome-wide Analysis of group A Streptococcus reveals a mutation that modulates global phenotype and disease specificity. PLoS Pathog. 241-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor, F. B., Jr., A. E. Bryant, K. E. Blick, E. Hack, P. M. Jansen, S. D. Kosanke, and D. L. Stevens. 1999. Staging of the baboon response to group A streptococci administered intramuscularly: a descriptive study of the clinical symptoms and clinical chemical response patterns. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29167-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voyich, J. M., J. M. Musser, and F. R. DeLeo. 2004. Streptococcus pyogenes and human neutrophils: a paradigm for evasion of innate host defense by bacterial pathogens. Microbes Infect. 61117-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker, M. J., A. Hollands, M. L. Sanderson-Smith, J. N. Cole, J. K. Kirk, A. Henningham, J. D. McArthur, K. Dinkla, R. K. Aziz, R. G. Kansal, A. J. Simpson, J. T. Buchanan, G. S. Chhatwal, M. Kotb, and V. Nizet. 2007. DNase Sda1 provides selection pressure for a switch to invasive group A streptococcal infection. Nat. Med. 13981-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.