Abstract

Germination and outgrowth are critical steps for returning Bacillus subtilis spores to life. However, oxidative stress due to full hydration of the spore core during germination and activation of metabolism in spore outgrowth may generate oxidative DNA damage that in many species is processed by apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) endonucleases. B. subtilis spores possess two AP endonucleases, Nfo and ExoA; the outgrowth of spores lacking both of these enzymes was slowed, and the spores had an elevated mutation frequency, suggesting that these enzymes repair DNA lesions induced by oxidative stress during spore germination and outgrowth. Addition of H2O2 also slowed the outgrowth of nfo exoA spores and increased the mutation frequency, and nfo and exoA mutations slowed the outgrowth of spores deficient in either RecA, nucleotide excision repair (NER), or the DNA-protective α/β-type small acid-soluble spore proteins (SASP). These results suggest that α/β-type SASP protect DNA of germinating spores against damage that can be repaired by Nfo and ExoA, which is generated either spontaneously or promoted by addition of H2O2. The contribution of RecA and Nfo/ExoA was similar to but greater than that of NER in repair of DNA damage generated during spore germination and outgrowth. However, nfo and exoA mutations increased the spontaneous mutation frequencies of outgrown spores lacking uvrA or recA to about the same extent, suggesting that DNA lesions generated during spore germination and outgrowth are processed by Nfo/ExoA in combination with NER and/or RecA. These results suggest that Nfo/ExoA, RecA, the NER system, and α/β-type SASP all contribute to the repair of and/or protection against oxidative damage of DNA in germinating and outgrowing spores.

Due to their ability to survive during long periods of dormancy, spores of Bacillus subtilis are an excellent model system in which to study the consequences of exposure to environmental factors that can cause DNA damage. Physical and chemical factors, including UV-A and -B from sunlight, high temperatures, desiccation, and oxidizing chemicals, such as hydrogen peroxide, have the potential to cause damage to dormant spore DNA (13, 15). However, spores of the genus Bacillus counter these potential damaging agents with a number of factors to maintain the integrity of the genome. These factors include (i) the spore coats, (ii) the low water content in the spore core, (iii) the low permeability of the spore's inner membrane to hydrophilic small molecules, and (iv) the saturation of spore DNA with α/β-type small acid-soluble spore proteins (SASP) (13, 28, 29, 31). The α/β-type SASP play the most direct role in protecting spore DNA from a variety of types of damage, including depurination-depyrimidination and hydroxyl radical-induced backbone cleavage. As a consequence, these proteins make major contributions to spore resistance to heat and oxidizing agents (13, 31). The α/β-type SASP are also a major factor in the high resistance of B. subtilis spores to UV light (13, 14, 28, 29, 31). However, these DNA binding proteins do not protect DNA against base alkylation (27).

Despite the existence of mechanisms that prevent DNA damage during long periods of dormancy and upon exposure to environmental stresses, spores can accumulate potentially lethal and mutagenic DNA damage (13, 28, 29, 31). Such damage may include strand breaks, as well as apurinic-apyrimidinic (AP) sites. The latter lesions are processed by AP endonucleases, which are important components of the base excision repair pathway. B. subtilis spores contain two AP endonucleases, Nfo and ExoA, and a recent report indicated that these enzymes are important in protecting the dormant spore from treatments that promote base loss and strand breaks in DNA (20).

Since spores are metabolically dormant and enzymes in the spore core, the site of spore DNA, are inactive, there can be no DNA repair in the dormant spore. However, spores can “return to life” during the process of germination (17, 30), which is triggered when specific germinants, generally amino acids or sugars, are sensed by receptors in the spore's inner membrane. This receptor-germinant interaction triggers germination events, including the release of dipicolinic acid and divalent cations from the spore core, hydrolysis of the spore cortex peptidoglycan, and uptake of water into the spore core to levels comparable to those in growing cells. The completion of spore germination (in particular, full core rehydration) then allows resumption of enzyme action in the spore core and the initiation of spore outgrowth that eventually converts the germinated spore into a growing cell (17). A crucial event early in spore outgrowth is the degradation of the α/β-type SASP by a specific spore protease; this degradation frees up spore DNA for transcription and eventually for replication (28, 32). The free amino acids produced in this proteolysis also support much of the energy metabolism that begins early in spore outgrowth.

While dormant spore DNA is well protected against damage, as noted above, the protective mechanisms are lost upon completion of spore germination and early in spore outgrowth, when the core water content increases and α/β-type SASP are degraded. Aerobic metabolism resumes only early in spore outgrowth and can lead to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS can generate a variety of types of DNA damage, including AP sites, several different base modifications, sugar damage, and single- and double-strand breaks (5, 19, 22, 34). As a consequence, DNA repair proteins packaged in the spore may be extremely important in spore outgrowth not only to repair damage that accumulated during spore dormancy but also to repair damage generated during spore germination and outgrowth. Indeed, a spore-specific catalase, KatX, plays a major role in protecting spores against oxidative stress during spore germination and outgrowth (1).

As noted above, germination and outgrowth are critical steps in the return of B. subtilis spores to vegetative growth, and during these processes spores may suddenly face an increase in ROS-induced DNA damage. Given the potential role of the AP endonucleases Nfo and ExoA in repair of such DNA damage (20), we investigated of the effects of nfo and exoA mutations on B. subtilis spore germination and outgrowth with and without an added oxidative stress agent, and in this paper we report the results of this investigation. We also examined the effects of loss of the majority of α/β-type SASP or other DNA repair proteins alone or in combination with nfo exoA mutations on spore germination and outgrowth, as well as on mutagenesis during these periods of development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and spore preparation.

All B. subtilis strains used in this work except YB300 were derived from strain PS832, a prototrophic derivative of strain 168, and they are listed in Table 1 along with the plasmids used. The wild-type strain referred to below is PS832, unless noted otherwise. The growth medium used routinely was Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (11). When appropriate, ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml), neomycin (10 μg/ml), or tetracycline (10 μg/ml) was added to the medium. Liquid cultures were incubated at 37°C with vigorous aeration. Cultures on solid media were also grown at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and description | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis strains | ||

| 168 | Wild type, trp | Laboratory stock |

| PS832 | Wild type, trp+ revertant of strain 168 | Laboratory stock |

| PS356a | ΔsspA ΔsspB α−β− | 10 |

| PERM450a | ΔsspA ΔsspB ΔexoA::tet Δnfo::neo α−β− Neor Tetr | 20 |

| PERM452a | ΔexoA::tet Tetr | 20 |

| PERM453a | Δnfo::neo Neor | 20 |

| PERM454a | ΔexoA::tet Δnfo::neo Neor Tetr | 20 |

| YB300 | recA Cmr | R. Yasbin (36) |

| PERM662a | recA Cmr | (YB300 → PS832)b |

| PERM663a | recA ΔexoA::tet Cmr Tetr | (pPERM374 → PS599)c |

| PERM665a | recA ΔexoA::tet Δnfo::neo Cmr Tetr Neor | (pPERM337 → PERM663)c |

| PS599a | uvrA42 trp+ | P. Setlow |

| PERM515a | uvrA ΔexoA::tet Tetr | (pPERM374 → PS599)c |

| PERM517a | uvrA ΔexoA::tet Δnfo::neo Tetr Neor | (pPERM337 → PERM515)c |

| Plasmids | ||

| pPERM337 | 1.3-kb SmaI-SmaI fragment containing a Neor cassette inserted into the NaeI site of nfo in pPERM282; Ampr Neor | 20 |

| pPERM374 | 469-bp XbaI-BamHI fragment (3′ region of exoA) and 537-bp EcoRI-HindIII fragment (5′ region of exoA) flanking the tetracycline gene of pDG1515; Ampr Tetrd | 20 |

The background for this strain is PS832.

Chromosomal DNA from the strain to the left of the arrow was used to transform the strain to the right of the arrow.

DNA of the plasmid to the left of the arrow was used to transform the strain to the right of the arrow.

See reference 6.

Spores of all strains were prepared at 37°C on 2× SG medium agar plates without antibiotics, and spores were harvested, cleaned, and stored as described previously (16). All dormant spore preparations used in this work were free (≥98%) of growing cells, germinated spores, and cell debris, as determined by phase-contrast microscopy.

Spore germination and outgrowth.

Unless otherwise noted, spore germination and outgrowth were performed in 25 ml of 2× SG medium supplemented with 10 mM l-alanine. Spores in water were first heat shocked for 30 min at 70°C, cooled on ice, and inoculated into germination medium at 37°C to obtain an initial optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.5. Where noted below, H2O2 (0.2 mM) was added after most spore germination had taken place (∼15 min after the initiation of spore germination). The OD600 of cultures were monitored with a Pharmacia Ultrospec 2000 spectrophotometer, and the values were plotted as a fraction of the initial OD600 (OD600 at time t/initial OD600) versus time.

Genetic and molecular biology techniques.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from B. subtilis, and competent B. subtilis cells were prepared and transformed with plasmid or chromosomal DNA as described previously (2, 4). For medium-scale preparation and purification of plasmid DNA commercial ion-exchange columns were used according to the instructions of the supplier (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA).

Construction of mutant strains.

Plasmids pPERM337 and pPERM374 (20) were used to transform B. subtilis strains PS599 (uvrA) and PERM662 (recA) to resistance to the appropriate antibiotics, which generated strains PERM517 (uvrA nfo exoA) and PERM665 (recA nfo exoA). The double recombination events leading to inactivation of the appropriate genes were confirmed by PCR (data not shown). Strains PERM454 (nfo exoA) and PERM450 (α−β− nfo exoA) have been described previously (20). A recA derivative of PS832 was generated by transformation to Cmr with chromosomal DNA (1 μg) from strain YB300 (36). The recA phenotype of Cmr transformants was confirmed by sensitivity to mitomycin C, as described previously (3). The exoA mutant was generated by deleting ∼20% of the exoA open reading frame and replacing it with a tetracycline resistance cassette; the nfo mutant was constructed by inserting a neomycin resistance cassette in the middle of the nfo open reading frame (20).

Analysis of spontaneous mutation frequencies.

Spontaneous mutations to rifampin resistance (Rifr) in outgrown spore cultures were determined as follows. Spores were germinated in 2× SG medium supplemented with 10 mM l-alanine as described above. Aliquots removed from cultures 180 min after inoculation of spores into germination medium were spread on six LB medium plates containing 10 μg/ml rifampin, and Rifr colonies were counted after 1 day of incubation at 37°C. The number of cells used to calculate the frequency of mutation to Rifr was determined by plating aliquots of appropriate dilutions on LB medium plates without rifampin and incubating the plates for 24 to 48 h at 37°C. Mutations to Rifr in growing cells were determined as follows. Overnight cultures of each strain were inoculated into flasks containing LB medium to an OD600 of 0.5, each culture was divided in half, and the two halves were transferred to different flasks. One of the cultures was left untreated, and 0.2 mM H2O2 was added to the other. Both flasks were shaken at 37°C for 180 min, and aliquots were processed to determine the frequency of mutation to Rifr as described above. These experiments were repeated at least twice.

RESULTS

Germination and outgrowth of spores lacking Nfo and ExoA.

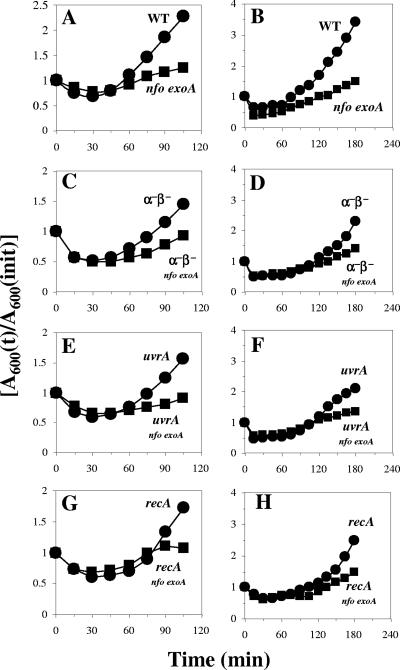

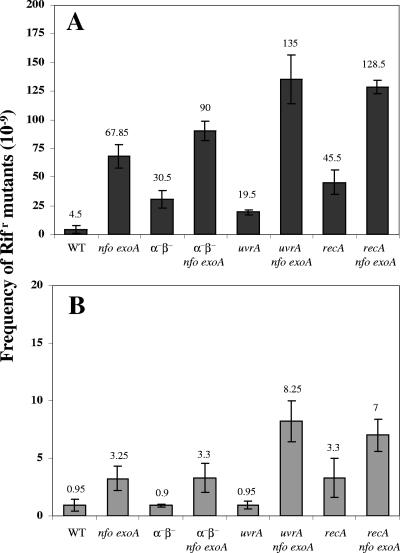

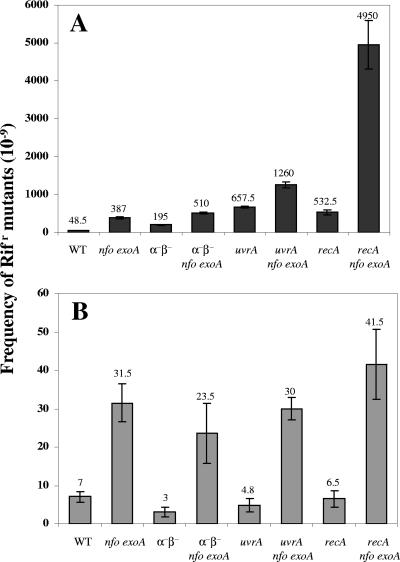

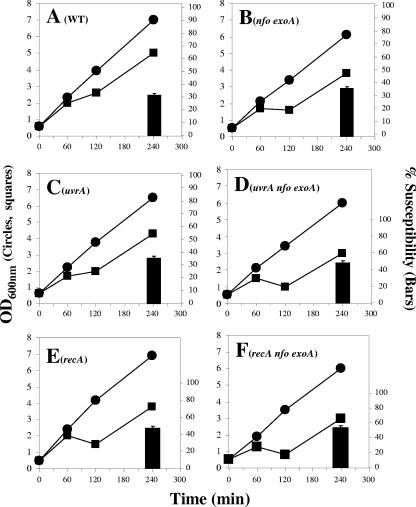

We first investigated how mutations in nfo or exoA or in both genes affected the germination and outgrowth of B. subtilis spores by inoculating B. subtilis wild-type, nfo, exoA, and nfo exoA spores into germination medium and monitoring the germination and outgrowth by determining the OD600. Compared with wild-type spores, nfo and exoA spores exhibited slower outgrowth, although they exhibited essentially identical rates of germination when germination was judged by determining the decrease in the OD600 of spore cultures shortly after addition of spores to germination medium (data not shown). Note that the initial decrease in the OD600 was due to both release of dipicolinic acid and full hydration of the spore core, major events in spore germination. The germination rate of spores lacking both Nfo and ExoA was similar to that of wild-type spores, but the return to vegetative growth (outgrowth) was significantly slower for the nfo exoA spores (Fig. 1A). The latter effect may have been due at least in part to DNA damage as the outgrown nfo exoA spores accumulated ∼10-fold more mutations than the outgrown wild-type spores or growing nfo exoA cells (Fig. 2). Thus, a tentative conclusion from these results is that significant damage occurs in the DNA of germinating and outgrowing spores, perhaps generated by oxidative stress, and that Nfo and ExoA are required to eliminate the lesions. To further investigate this idea, nfo exoA spores were outgrown with 0.2 mM H2O2 added ∼15 min after the initiation of germination, when most spore germination was complete, as shown by the decrease in the OD600 (Fig. 1B). Although the H2O2 slowed the outgrowth of wild-type spores, the effect was greater with spores lacking Nfo and ExoA. In addition, the mutation frequency in outgrown nfo exoA spores was ∼10-fold higher than that in outgrown wild-type spores treated with H2O2 (Fig. 3). However, H2O2 was mutagenic for both wild-type and nfo exoA cells and spores, as shown by the ∼10-fold-higher mutation frequencies of the cultures treated with H2O2.

FIG. 1.

Germination and outgrowth of spores of different strains. Dormant spores of the wild-type (•) and nfo exoA (▪) strains (A and B), α−β− (•) and α−β− nfo exoA (▪) strains (C and D), uvrA (•) and uvrA nfo exoA (▪) strains (E and F), and recA (•) and recA nfo exoA (▪) strains (G and H) were heat shocked and germinated without (A, C, E, and G) or with (B, D, F, and H) 0.2 mM H2O2 added ∼15 min after the start of germination, and spore germination and outgrowth were measured by monitoring the OD600 of the cultures as described in Materials and Methods. The results are representative, and the experiment was performed at least three times with different lots of spores, all of which produced similar results. WT, wild type.

FIG. 2.

Mutation frequencies in outgrown spores and growing cells of different strains. (A) Dormant spores of different strains were heat shocked and germinated, aliquots were taken after 180 min, and frequencies of mutation to Rifr were determined as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Overnight cultures of growing cells of different strains were inoculated into LB medium, and after 180 min of growth the frequencies of mutation to Rifr were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The values are averages ± standard deviations for duplicate determinations in two separate experiments (with different cultures or lots of spores). WT, wild type.

FIG. 3.

Mutation frequencies of outgrown spores and growing cells of different strains treated with H2O2. (A) Dormant spores of different strains were heat shocked and germinated, 0.2 mM H2O2 was added 15 min after the start of spore germination, aliquots were taken after 180 min of incubation, and frequencies of mutation to Rifr were determined as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Overnight cultures of growing cells of different strains were inoculated into LB medium, 0.2 mM H2O2 was added, and after 180 min of growth frequencies of mutation to Rifr were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The values are averages ± standard deviations for duplicate determinations in two separate experiments (with different cultures or lots of spores). WT, wild type.

Effects of nfo and exoA mutations on germination and outgrowth of spores lacking α/β-type SASP.

The main factor protecting dormant spore DNA from damage is the α/β-type SASP, as spores lacking the majority of these proteins (termed α−β− spores) are much more sensitive to a variety of DNA-damaging treatments (13, 23, 24). Perhaps not surprisingly, the nfo exoA mutations slowed the outgrowth of α−β− spores, although they had little or no effect on spore germination (Fig. 1C). The mutation frequency of outgrown α−β− spores was about seven times higher than that that of outgrown wild-type spores, and the value was increased two- to threefold by the nfo exoA mutations (Fig. 2). These results suggest that α/β-type SASP may also play an important role in protecting DNA against damage generated during spore germination and outgrowth. H2O2 also significantly slowed the outgrowth of α−β− spores, and this effect was increased when Nfo and ExoA were also absent (Fig. 1D). The mutation frequencies in outgrown H2O2-treated α−β− spores and α−β− nfo exoA spores were also ∼4- and 10-fold higher than that in outgrown H2O2-treated spores that contained α/β-type SASP, respectively (Fig. 3).

Effects of nfo and exoA mutations on germination and outgrowth of spores lacking either recombination repair or NER.

The nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway plays an important role in protecting B. subtilis against a number of agents that cause DNA damage (39, 40, 41). Consequently, mutations in genes encoding NER components, particularly uvrA or uvrC, make B. subtilis cells more sensitive to several factors, including UV-C light, mitomycin C, and H2O2 (40, 41). In B. subtilis the expression of genes involved in DNA repair, including some genes of the NER pathway, is induced by DNA damage and during competence (3, 8, 9). This response, which may well be triggered by single-stranded DNA, is called the SOS response and is controlled by RecA and the transcriptional repressor DinR (18, 38).

Since UvrA and RecA play important roles in protecting B. subtilis from DNA damage, we investigated how nfo and exoA mutations in either a uvrA or recA genetic background affected spore germination and outgrowth. The absence of Nfo and ExoA in uvrA and recA spores again resulted in a slow-outgrowth phenotype (Fig. 1E and 1G). In addition, outgrown uvrA and recA spores had a higher mutation frequency than outgrown wild-type spores, and this phenotype was exacerbated when Nfo and ExoA were absent in either genetic background (Fig. 2).

The rate of outgrowth of uvrA and recA spores was also decreased by addition of H2O2, and this effect was greater with the uvrA nfo exoA and recA nfo exoA spores (Fig. 1F and 1H). The H2O2 most probably damaged the DNA of the outgrown uvrA and recA spores, since these outgrown spores had ∼10-fold-higher mutation frequencies than outgrown wild-type spores (Fig. 3). The absence of Nfo and ExoA also resulted in a dramatic increase in the mutation frequency of outgrown H2O2-treated recA spores (Fig. 3). However, outgrown H2O2-treated uvrA nfo exoA spores had a mutation frequency that was only about twofold higher than that of outgrown H2O2-treated uvrA spores (Fig. 3).

Effect of nfo and exoA mutations during spore germination and outgrowth is not due to DNA damage generated during storage or activation of spores.

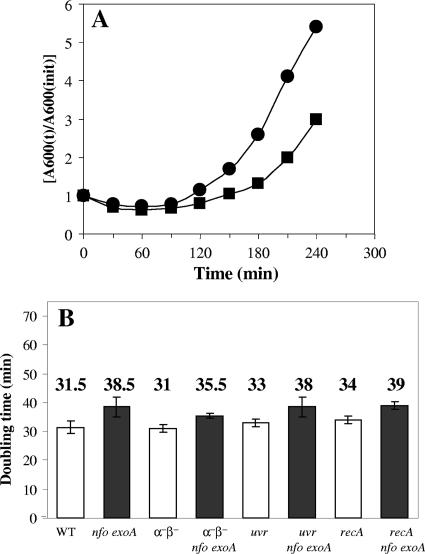

While the effects of Nfo and ExoA on spore germination and outgrowth were dramatic, particularly in minimizing mutagenic DNA damage, it was possible that the damage was generated not during spore germination or outgrowth but during the heat treatment at 70°C used to activate spores prior to germination. However, when wild-type and nfo exoA spores were germinated without prior heat activation, the outgrowth of the nfo exoA spores was still slower than the outgrowth of wild-type spores (Fig. 4A). However, spore germination and outgrowth, particularly germination, were more asynchronous and thus slower without prior heat activation (compare Fig. 4A and 1A).

FIG. 4.

Spore germination and outgrowth without prior heat activation and doubling times of different strains. (A) Wild-type (•) and nfo exoA (▪) dormant spores were germinated without a prior heat shock, and spore germination and outgrowth were measured by monitoring the OD600 of the cultures as described in Materials and Methods. The results are representative, and the experiment was performed at least two times with different lots of spores, all of which produced similar results. (B) Overnight cultures of various strains were inoculated into 25 ml of LB medium, the cultures were shaken at 37°C, and the OD600 of the cultures were monitored. The doubling times are the averages ± standard deviations for values obtained from two different cultures. WT, wild type.

A second possible explanation for differences in outgrowth of spores with and without different combinations of DNA repair or protective genes is that the mutations decrease the rate of cell growth significantly, since such a decrease might slow spore outgrowth. However, while the nfo exoA mutations did increase the vegetative cell doubling times very slightly, this effect was minimal, and the other mutations had no effect on cell growth rates (Fig. 4B). Consequently, it appears very unlikely that this was the cause of the slow outgrowth of the spores of the various strains.

A third possible explanation for the slow outgrowth of spores deficient in DNA repair or protection, as well as the accumulation of DNA damage in these spores, is that the DNA damage was not generated during spore germination and outgrowth but during spore preparation and storage. Indeed, it has been shown that α−β− spores can accumulate significant amounts of DNA damage during long-term storage (32). To examine this possibility, genomic DNA was isolated from dormant spores of the PS832 (wild type; Trp+), nfo exoA, α−β−, and α−β− nfo exoA strains and was introduced by transformation into B. subtilis 168 (Trp−), and Rifr and Rifr Trp+ colonies were selected. The results of this experiment (Table 2) showed that the genomic DNA from the three types of mutant dormant spores increased the number of Rifr Trpr colonies only about twofold compared to the colonies generated by DNA from wild-type spores, and the numbers of Trp+ colonies/mg of transforming DNA were essentially identical for all the DNAs from strains with PS832 backgrounds (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Transformation of B. subtilis 168 from Trp− to Rifr Trp+ using genomic DNA from dormant spores of various strains

| Strain | Frequency of Rifr mutants (10−9)c | No. of Rifr Trp+colonies/100 Rifr coloniesd |

|---|---|---|

| 168 Trp−a | 0.83 ± 0.16 | 1.5 ± 0.7 |

| PS832 Trp+ → 168 Trp−b | 0.85 ± 0.21 | 4.5 ± 1.4 |

| nfo exoA → 168 Trp−b | 0.91 ± 0.14 | 9.5 ± 2.1 |

| α−β− → 168 Trp−b | 0.94 ± 0.05 | 9.0 ± 1.4 |

| α−β−nfo exoA → 168 Trp−b | 0.99 ± 0.16 | 10.5 ± 1.4 |

Untransformed strain.

Genomic DNA (1 μg) from dormant spores of the strain to the left of the arrow was used to transform competent cells of the strain to the right of the arrow with selection for Rifr.

Averages ± standard deviations for two independent experiments.

One hundred Rifr colonies from the two frequency experiments were transferred to agar plates containing 1× Spizizen's medium salts (35) supplemented with 0.5% glucose to screen for auxotrophy. The values are the averages ± standard deviations for the two experiments.

Effects of nfo and exoA mutations on vegetative cells deficient in recombination repair or NER.

As noted above, the nfo exoA deletions alone or combined with either uvrA or recA mutations delayed the return of outgrowing spores to vegetative growth and increased the outgrowing spores’ susceptibility to H2O2. In addition, these outgrown spores had a high mutation frequency, and the frequency was higher for the recA nfo exoA and uvrA nfo exoA spores (Fig. 2). UvrA and RecA are both involved in repairing DNA damage in vegetative cells (39, 40, 41), and exoA expression, but not nfo expression, takes place in growing cells (20, 33). Therefore, we investigated whether the requirement for these proteins was different during spore outgrowth and exponential growth. As noted above (Fig. 4B), there were no major differences in the doubling times of the wild-type, α−β−, uvrA, and recA strains, although the nfoA exoA mutations slightly increased the doubling times in the three genetic backgrounds. In addition, as previously described (20), cells lacking Nfo and ExoA were around 1.2 times more susceptible to H2O2 treatment than cells of the parental strain (Fig. 5A and B). Similar levels of susceptibility were obtained when α−β− cells and α−β− nfo exoA cells were treated with H2O2 during exponential growth (data not shown). On the other hand, after 240 min of growth, cells of uvrA and recA strains were around 5 and 16% more susceptible to H2O2 than wild-type cells, respectively, and this effect was increased around 13 and 7% in the uvrA nfo exoA and recA nfo exoA strains, respectively (Fig. 5C to F).

FIG. 5.

Growth of different strains in the absence or presence of H2O2. Overnight cultures of the wild-type (A), nfo exoA (B), uvrA (C), uvrA nfo exoA (D), recA (E), and recA nfo exoA (F) strains were inoculated into 25 ml of LB medium and grown to an OD600 of ∼0.5. Each culture was divided into two subcultures; 0.2 mM H2O2 was added to one subculture (▪), and nothing was added to the other subculture (•); and cell growth was monitored by determining the OD600. The results are representative, and the experiments were performed at least two times with different cultures. The percentage of hydrogen peroxide susceptibility (bars) was calculated for each strain at 240 min by using the following equation: (1 − OD600 of H2O2-treated culture/OD600 of nontreated culture) × 100. The values are the averages and standard deviations for duplicate determinations in two separate experiments. WT, wild type.

Exponentially growing cells of nfo exo, recA nfo exoA, and uvrA nfo exoA strains had a higher mutation frequency than their parental strains whether or not they were treated with H2O2 (Fig. 2, 3). However, in the absence of H2O2, the mutation frequencies of the nfo exo, recA nfo exoA, uvrA nfo exoA, and parental strains were ≥10-fold higher in outgrown spores than in growing cells, and in the presence of H2O2 the mutation frequencies were ≥100-fold higher in outgrown spores than in growing cells of the same strains (Fig. 2 and 3).

DISCUSSION

The entrance of water into the spore core and the activation of aerobic metabolism in the outgrowing spore may generate DNA damage that is processed by the base excision repair pathway. Indeed, our results revealed that an absence of the AP endonucleases Nfo and ExoA in B. subtilis significantly delayed spore outgrowth. This phenotype appears to be probably due to DNA damage, since outgrown nfoA exoA spores had a significantly higher mutation frequency than outgrown wild-type spores or growing nfo exoA or wild-type cells. The slow-outgrowth phenotype of nfo exoA spores was not the result of DNA damage generated during heat activation prior to spore germination, although some of the DNA damage found in outgrown spores deficient in DNA repair or protection may have accumulated in dormant spores. However, normally, the amount of the latter damage seems to be small compared to the DNA damage generated in spore germination and outgrowth, as the mutation frequency in outgrown nfo exoA spores was ∼20-fold higher than that in outgrown wild-type spores, while the dormant spore DNAs from these two types of spores exhibited only an ∼2-fold difference in mutations when the DNAs were assayed by examining transformation. Consequently, these results support the notion that oxidative DNA damage occurs in the germinating and outgrowing spore and Nfo and ExoA have an important role in eliminating this type of damage. In addition, since wild-type and nfo exoA dormant spores were equally sensitive to H2O2 (20), it is reasonable to propose that (i) the DNA resistance to H2O2 is different in dormant spores and germinating and outgrowing spores and (ii) Nfo and ExoA are important in eliminating H2O2-induced DNA damage during spore outgrowth. The results described in this paper also implicate α/β-type SASP in protecting the germinating and outgrowing spores from DNA damage, since the mutation frequency was higher in outgrown α−β− spores than in outgrown wild-type spores and was significantly increased in α−β− spores by mutations in nfo and exoA. However, the resistance conferred by α/β-type SASP to dormant spores against several DNA-damaging factors is ultimately lost during spore outgrowth (17, 23, 24), and thus the protective effect postulated here would operate only until α/β-type SASP are degraded by the specific germination protease germination protease in outgrowth (21, 28). Indeed, spore resistance to UV radiation persists well after the initiation of spore germination (21). A recent study revealed that loss of ExoA and Nfo did not sensitize growing cells or wild-type or α−β− spores to H2O2 and t-butylhydroperoxide (20). However, our results showed that outgrowth of α−β− spores and α−β− nfo exoA spores was significantly slowed by H2O2 and that there was a concomitant increase in the mutation frequency of the outgrown spores compared with that of outgrown wild-type spores. Thus, in contrast to what has been observed for dormant spores, the DNA of germinating and outgrowing spores (this study) and the DNA of dormant spores lacking α/β-type SASP (24, 25, 27, 28) are evidently subject to damage by H2O2. A recent study showed that neither ExoA nor Nfo repaired the DNA damage induced by hydrogen peroxide in α−β− spores (20). In contrast, the current results implicate Nfo and ExoA in repair of H2O2-induced DNA damage during spore germination and outgrowth. Thus, it is possible that the DNA lesions induced by H2O2 during spore germination and outgrowth are different from those generated in dormant α−β− spores.

As noted above, RecA and UvrA are also involved in repairing spore DNA damage (26), and recA spores are more sensitive to UV-C and dry heat than wild-type spores (7, 12, 26). The results of this work support the idea that NER and RecA are also involved in repairing DNA damage that accumulates during spore germination and outgrowth. Analysis of the mutation frequencies in outgrown nfo exoA, recA, and uvrA spores revealed that RecA and Nfo/ExoA make similar contributions to repair of DNA damage that accumulates during spore germination and outgrowth, while the contribution of NER is less. However, the nfo and exoA mutations increased the mutation frequencies of outgrown uvrA and recA spores to about the same level, suggesting that some DNA lesions generated during germination and outgrowth are processed by Nfo and ExoA, as well as by NER and RecA. Previous results also showed that a recA mutation renders α−β− spores less resistant to H2O2, suggesting that RecA is directly or indirectly involved in repairing H2O2-induced DNA lesions in these spores (26). In the present work, treatment of germinating and outgrowing recA spores with H2O2 revealed the importance of RecA and Nfo/ExoA in the repair of DNA damage induced by oxidative stress. Therefore, our results strongly suggest that much of the DNA damage caused by H2O2 during spore germination and outgrowth is processed by Nfo/ExoA and RecA.

Our results also showed that the nfo exoA mutations affected the growth rate of growing uvrA and recA cells slightly, and this effect was greater when cells were treated with H2O2. However, comparison of the mutation frequencies in growing cells and outgrown spores with and without H2O2 treatment suggested that the requirement for UvrA, RecA, and Nfo/ExoA for repair of oxidative DNA damage is greater in outgrowing spores than in growing cells.

Finally, although the nfo exoA mutations slowed the outgrowth of all spores tested, these mutations did not stop this process, suggesting that spores have mechanisms that allow outgrowth even with minimal DNA repair. On the other hand, the high levels of mutations observed in outgrown spores deficient in Nfo/ExoA and RecA either in the presence or in the absence of H2O2 suggest that, as previously proposed (27), DNA lesions can be either repaired or bypassed during spore outgrowth in an error-prone manner, perhaps with participation of DNA polymerase YqjH and/or DNA polymerase YqjW (37).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología of México (CONACYT grant 43644) and from the University of Guanajuato to M. Pedraza-Reyes. J. R. Ibarra, J. A. Rojas, K. López, and A. D. Orozco were supported by fellowships from CONACYT. P. Setlow was supported by a grant from the Army Research Office.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 January 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bagyan, I., L. Casillas-Martinez, and P. Setlow. 1998. The katX gene, which codes for the catalase in spores of Bacillus subtilis, is essential for hydrogen peroxide resistance of the germinating spore. J. Bacteriol. 1802057-2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boylan, R. J., N. H. Mendelson, D. Brooks, and F. E. Young. 1972. Regulation of the bacterial cell wall: analysis of a mutant of Bacillus subtilis defective in the biosynthesis of teichoic acid. J. Bacteriol. 173281-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheo, D. L., K. W. Bayles, and R. E. Yasbin. 1991. Cloning and characterization of DNA damage-inducible promoter regions from Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1731696-1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutting, S. M., and P. B. Vander Horn. 1990. Genetic analysis, p. 27-74. In C. R. Harwood and S. M. Cutting (ed.), Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley and Sons, Sussex, England.

- 5.Friedberg, E. C., G. C. Walker, and W. Siede. 1995. DNA repair and mutagenesis. American Society for Microbiology, Washington DC.

- 6.Guérout-Fleury, A. M., K. Shazand, N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1995. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 167335-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanlin, J. H., S. J. Lombardi, and R. A. Slepecky. 1985. Heat and UV light resistance of vegetative cells and spores of Bacillus subtilis Rec− mutants. J. Bacteriol. 163774-777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Love, P. E., M. S. Lyle, and R. E. Yasbin. 1985. DNA damage inducible (din) loci are transcriptionally activated in competent Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 826201-6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovett, C. M., Jr., P. E. Love, and R. E. Yasbin. 1989. Competence specific induction of the Bacillus subtilis RecA protein analog: evidence for dual regulation of a recombination protein. J. Bacteriol. 1712318-2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mason, J. M., and P. Setlow. 1987. Essential role of small, acid-soluble spore proteins in resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to ultraviolet light. J. Bacteriol. 167174-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 12.Munakata, N., and C. S. Rupert. 1975. Effects of DNA-polymerase-defective and recombination-deficient mutations on the ultraviolet sensitivity of Bacillus subtilis spores. Mutat. Res. 27157-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholson, W. L., N. Munakata, G. Horneck, H. G. Melosh, and P. Setlow. 2000. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64548-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson, W. L., and P. Fajardo-Cavazos. 1997. DNA repair and the ultraviolet radiation resistance of bacterial spores: from the laboratory to the environment. Recent Res. Dev. Microbiol. 1125-140. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicholson, W. L., A. C. Shuerger, and P. Setlow. 2005. The solar UV environment and bacterial spore UV resistance: considerations for Earth-to-Mars transport by natural processes and human spaceflight. Mutat. Res. 571249-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholson, W. L., and P. Setlow. 1990. Sporulation, germination, and outgrowth, p. 391-450. In C. R. Harwood and S. M. Cutting (ed.), Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley and Sons, Sussex, England.

- 17.Paidhungat, M., and P. Setlow. 2001. Spore germination and outgrowth, p. 537-548. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its relatives: from genes to cells. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 18.Raymond-Denise, A., and N. Guillen. 1992. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis dinR and recA genes after DNA damage and during competence. J. Bacteriol. 1743171-3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riley, P. A. 1994. Free radicals in biology: oxidative stress and the effects of ionizing radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 6527-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salas-Pacheco, J. M., B. Setlow, P. Setlow, and M. Pedraza-Reyes. 2005. Role of the YqfS (Nfo) and ExoA apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases in protecting Bacillus subtilis spores from DNA damage. J. Bacteriol. 1877374-7381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sánchez-Salas, J. L., M. L. Santiago-Lara, B. Setlow, M. D. Sussman, and P. Setlow. 1992. Properties of Bacillus megaterium and Bacillus subtilis mutants which lack the protease that degrades small, acid-soluble proteins during spore germination. J. Bacteriol. 174807-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saran, M., and W. Bors. 1990. Radical reactions in vivo: an overview. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 29249-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Setlow, B., C. A. Setlow, and P. Setlow. 1997. Killing bacterial spores by organic hydroperoxides. J. Ind. Microbiol. 18384-388. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Setlow, B., and P. Setlow. 1993. Binding of small, acid-soluble spore proteins to DNA plays a significant role in the resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to hydrogen peroxide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 593418-3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Setlow, B., and P. Setlow. 1994. Heat inactivation of Bacillus subtilis spores lacking small, acid-soluble spore proteins is accompanied by generation of abasic sites in spore DNA. J. Bacteriol. 1762111-2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Setlow, B., and P. Setlow. 1996. Role of DNA repair in Bacillus subtilis spore resistance. J. Bacteriol. 1783486-3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Setlow, B., K. J. Tautvydas, and P. Setlow. 1998. Small acid-soluble spore proteins of the α/β type do not protect the DNA in Bacillus subtilis spores against base alkylation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 641958-1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Setlow, P. 1988. Small acid-soluble spore proteins of Bacillus species: structure, synthesis, genetics, function and degradation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 42319-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Setlow, P. 1995. Mechanisms for the prevention of damage to DNA in spores of Bacillus species. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 4929-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Setlow, P. 2003. Spore germination. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6550-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Setlow, P. 2006. Spores of Bacillus subtilis: their resistance to radiation, heat and chemicals. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101514-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Setlow, P. 2007. I will survive: DNA protection in bacterial spores. Trends Microbiol. 15172-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shida, T., T. Ogawa, N. Ogasawara, and J. Sekiguchi. 1999. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis ExoA protein: a multifunctional DNA-repair enzyme similar to the Escherichia coli exonuclease III. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 631528-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simic, M. G., K. A. Taylor., J. F. Ward., and C. Von Sonntag (ed.). 1988. Oxygen radicals in biology and medicine. Basic life sciences, vol. 49. Plenum Publishing Corp., New York, NY.

- 35.Spizizen, J. 1958. Transformation of biochemically deficient strains of Bacillus subtilis by deoxyribonucleate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 441072-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sung, H.-M., and R. E. Yasbin. 2002. Adaptive, or stationary-phase, mutagenesis, a component of bacterial differentiation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1845641-5653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sung, H.-M., G. Yeamans, C. A. Ross, and R. E. Yasbin. 2003. Roles of YqjH and YqjW, homologs of the Escherichia coli UmuC/DinB or Y superfamily of DNA polymerases, in stationary-phase mutagenesis and UV-induced mutagenesis of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1852153-2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winterling, K. W., D. Chafin, J. J. Hayes, J. Sun., A. S. Levine, R. E. Yasbin, and R. Woodgate. 1998. The Bacillus subtilis DinR binding site: redefinition of the consensus sequence. J. Bacteriol. 1802201-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yasbin, R. E., D. Cheo, and D. Bol. 1993. DNA repair systems, p. 529-537. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch and R. Losick (ed.). Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 40.Yasbin, R. E., D. Cheo, and K. W. Bayles. 1992. Inducible DNA repair and differentiation in Bacillus subtilis: interactions between global regulons. Mol. Microbiol. 61263-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yasbin, R. E., D. Cheo, and K. W. Bayles. 1991. The SOB system of Bacillus subtilis: a global regulon involved in DNA repair and differentiation. Res. Microbiol. 142885-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]