Abstract

The alpha/beta interferon (IFN-α/β) response is critical for host protection against disseminated replication of many viruses, primarily due to the transcriptional upregulation of genes encoding antiviral proteins. Previously, we determined that infection of mice with Sindbis virus (SB) could be converted from asymptomatic to rapidly fatal by elimination of this response (K. D. Ryman et al., J. Virol. 74:3366-3378, 2000). Probing of the specific antiviral proteins important for IFN-mediated control of virus replication indicated that the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR, exerted some early antiviral effects prior to IFN-α/β signaling; however, the ability of IFN-α/β to inhibit SB and protect mice from clinical disease was essentially undiminished in the absence of PKR, RNase L, and Mx proteins (K. D. Ryman et al., Viral Immunol. 15:53-76, 2002). One characteristic of the PKR/RNase L/Mx-independent antiviral effect was a blockage of viral protein accumulation early after infection (K. D. Ryman et al., J. Virol. 79:1487-1499, 2005). We show here that IFN-α/β priming induces a PKR-independent activity that inhibits m7G cap-dependent translation at a step after association of cap-binding factors and the small ribosome subunit but before formation of the 80S ribosome. Furthermore, the activity targets mRNAs that enter across the cytoplasmic membrane, but nucleus-transcribed RNAs are relatively unaffected. Therefore, this IFN-α/β-induced antiviral activity represents a mechanism through which IFN-α/β-exposed cells are defended against viruses that enter the cytoplasm, while preserving essential host activities, including the expression of antiviral and stress-responsive genes.

Pathogenesis studies with mice deficient in receptors for alpha/beta interferon (IFN-α/β) and IFN-γ have indicated that IFN-mediated innate responses are vital for the protection of mammals from infections caused by diverse virus types, e.g., lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (4, 50), Theiler's virus (14), influenza virus (17), measles virus (32), vesicular stomatitis virus (48), and several alphaviruses, including Semliki Forest virus (23, 33), Sindbis virus (SB) (41, 42), and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) (52). Our results with SB indicate that antiviral activities upregulated by IFN-α/β signaling so severely restrict replication of this apathogenic virus in adult mice that it is virtually undetectable, and disease is completely prevented. However, in the absence of a functional IFN-α/β system, adult mice succumb rapidly to fatal SB disease primarily as a result of systemic infection of macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) (41). The mechanisms through which the IFN response controls alphavirus replication have not been elucidated (8, 43, 44). Our results have shown that PKR, but not RNase L, plays an early role in limiting virus replication in DCs; however, IFN-α/β signaling in PKR-deficient animals (PKR−/−) can protect them from fatal SB infection and any manifestations of disease. Furthermore, IFN-mediated protection of DCs or murine embryo fibroblast (MEF) cultures derived from PKR−/− mice is as potent as in control cultures (44), and virus replication in these cultures is inhibited very early after infection (43).

The canonical IFN-α/β signaling pathway involves interaction with the heterodimeric IFN-α/β receptor (IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 subunits), activation of Jak1 and Tyk2 kinases, and phosphorylation and heterodimerization of the STAT1 and STAT2 transcription factors. STAT1/2 heterodimers associate with IRF9, forming the ISGF3 complex which translocates to the nucleus and binds to IFN-stimulated response elements, resulting in transcriptional upregulation of genes, some of which possess antiviral activity. The IFN-α/β-upregulated antiviral responses have been thought to primarily involve activation of PKR and 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase (2′-5′ OAS) by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). PKR-mediated antiviral effects have been attributed to phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) and consequent inhibition of host cell and viral translation initiation. In addition, activated PKR plays a role in apoptosis of infected cells (see, for example, reference 54). The IFN-inducible 2′-5′ OAS binds dsRNA and synthesizes 2′-5′-linked oligoadenylates that activate constitutive RNase L to cleave host and viral single-stranded RNA. More recently, antiviral effects have also been attributed to the IFN-α/β-inducible proteins Mx, a tryptophan-degrading enzyme (38), adenosine deaminase (34), ISG20 (13, 56), p56 (51, 56), ISG15 (28, 29, 40), viperin (56), mGBP2 (6), GBP-1 (1), the APOBEC proteins (50), and other, as-yet-undescribed, factors (43, 57).

In the present study, we provide evidence that a potent PKR-independent translation inhibiting activity is stimulated in cells exposed to IFN-α/β and that this effect is broadly active against multiple positive-sense RNA viruses. Furthermore, the activity specifically blocks the cap-dependent translation of exogenous mRNA introduced into cells across the cytoplasmic membrane, whereas endogenous mRNAs synthesized in the nucleus and transported to the cytoplasm for translation are not affected. We propose this pathway as a novel host defense strategy that, in the context of an IFN-α/β response, identifies cap-dependent mRNAs originating outside the nucleus as “nonself” and specifically inhibits their translation while maintaining the translation of host mRNAs, which may be particularly important for the production of cell stress-responsive proteins after virus infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

Baby hamster kidney cells (BHK-21; ATCC CCL-10) were maintained in alpha minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% donor calf serum, 2.9 mg of tryptose phosphate/ml, 0.29 mg of l-glutamine/ml, 100 U of penicillin/ml, and 0.05 mg of streptomycin/ml. PKR−/− (53), HRI−/−, (21) GCN2−/− (22), and PERK−/− (22) MEFs were maintained in Dulbecco minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen) and with glutamine and penicillin-streptomycin as described above. eIF2α A/A and control MEFs (46) were maintained in identical medium also including 1× β-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen) and 1× nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen).

Viruses and translation reporters.

Construction and in vitro transcription conditions for the replication-competent SB luciferase reporter virus pToto1101/Luc, and the replication-incompetent SB luciferase reporter virus pToto1101/Luc/pol (in both of which the firefly luciferase [fLuc] gene has been inserted in-frame into the nsP3 gene) have been described previously (3). Stocks of pToto1101/Luc were prepared as described previously (43). Construction and in vitro transcription conditions for the SB RNA reporter pSBΔnsP/fLuc, the host mimic RNA reporter pSP64-Renilla-polyA, and the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) internal ribosome entry site (IRES) RNA reporter pCITE-A31 have been described (3, 43). The VEEV and eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV) RNA translation reporters were constructed similarly to the SB RNA reporter by overlap PCR mutagenesis of replicon genomes (the EEEV replicon was obtained from Michael Parker, USAMRIID) expressing the fLuc gene from the subgenomic promoter (43). Briefly, primers were designed to truncate the nsP1 gene at either amino acid 72 (VEEV) or amino acid 84 (EEEV) and fuse in-frame the fLuc gene. Thereby, most of the nonstructural genes and the subgenomic promoter were deleted, yielding a reporter whose translation initiated from the authentic genome initiation site of the respective virus. The host mRNA mimic expressing Renilla luciferase has been described previously (3). The host mRNA mimic expressing fLuc was constructed by PCR mutagenesis in which XbaI sites were inserted at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the fLuc gene, followed by insertion into the pSP64-polyA vector (Promega).

The nonreplicative dengue 2 fLuc RNA reporter was a gift from Eva Harris, UC-Berkley, and has been described (12). A yellow fever virus (YFV) 17D-based propagation-incompetent replicon genome was generated by overlap PCR to substitute the fLuc gene for the structural protein genes in the full-length YFV 17D cDNA clone, pACNR/FLYF-17Dx (5). The conserved 5′ sequence (5′ CS; nucleotides 156 to 165) that is essential for YFV replication (5) was retained, fused to the inserted fLuc. A “2A-like” protease sequence was inserted downstream of fLuc for efficient cleavage from NS1. We further created a nonreplicative translation reporter from this construct by deleting the majority of structural and nonstructural genes by digestion with ApaI and SfiI and blunt end ligating the vector. This construct could be linearized with XhoI and transcribed in vitro, producing reporter mRNA as with the alphavirus and dengue 2 reporters. With the exception of the dengue 2 reporter, which was transcribed as described previously (12), all capped versions of RNA-based reporters were synthesized using the mMessage mMachine SP6 or T7 kits (Ambion). Synthesis of the SB reporter RNA lacking a 5′ cap structure was completed by using a Ribomax (Qiagen) RNA probe kit. Reporter RNAs synthesized with host decapping enzyme cleavage-resistant cap analog were transcribed as described previously (19). For radiolabeling of in vitro-transcribed RNA, transcripts were synthesized as described above in the presence of [32P] ATP (Amersham), precipitated as described above, and used directly for electroporation.

The DNA-based SB fLuc reporter was constructed by overlap PCR to fuse the first nucleotide of the SB genome in the SB RNA translation reporter with the cytomegalovirus promoter transcriptional start site of pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). Overlap PCR produced an amplicon that could be digested with NdeI and XhoI and inserted into a similarly digested pcDNA3.1 vector. Prior to transfection, the vector was linearized with XhoI to provide a transcriptional endpoint like the RNA reporters. For the host mRNA-mimic DNA reporters, the fLuc or Renilla luciferase genes were transferred from the host mimic RNA reporters into the multiple cloning site of the pcDNA3.1 vector. This plasmid could be linearized with EcoRI to provide the transcriptional stop site.

Cells were infected at 37°C for 1 h with virus derived from pToto1101Luc at a multiplicity of infection of 1. Virus-derived reporters were introduced into cells by either electroporation (7.5 μg per reaction; Bio-Rad GenePulser) or lipofection (1 to 2 μg per reaction; Dharmacon Dharmafect 3 reagent). For electroporation, cells were harvested by trypsin digestion, pelleted twice, and electroporated in OptiMEM serum-free growth medium (Invitrogen). After electroporation, cells were washed twice and either plated in six-well plates or maintained in suspension for various intervals. Prior to harvesting for further analysis, cells were washed an additional five times with OptiMEM. For re-electroporation of cytoplasm-exposed RNA, the RNA was harvested from cells electroporated as described above by using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). A total of 40 μg of total cellular RNA purified from electroporated cells was re-electroporated into new cells as described above.

Cytokine and drug treatment and luciferase assay.

MEF cultures were treated with 1,000 IU of biologically derived IFN-α/β (Access Biomedical)/ml for 6 h prior to transfection with nucleic acids or infection with pToto1101/Luc. To inhibit IFN-α/β-induced gene transcription, cultures were treated with 0.5 mg of actinomycin D (Sigma)/ml for 1 h, followed by the addition of IFN-α/β as described above and continued incubation for an additional 6 h prior to the introduction of RNA or infection as described above. Luciferase assays were performed with 20 μl of cell lysates as previously described (43).

Measurement of cellular translation.

Untreated or IFN-α/β-primed PKR−/− MEFs were either mock electroporated, electroporated with no RNA, or electroporated with SB or EMCV reporter RNAs as described above. At 2 or 12 h postelectroporation, 50 μCi of [35S]cysteine-methionine (Amersham)/ml was added to supernatants, and incubation was continued for 1 h. The cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline and then lysed in whole-cell lysis buffer (10 mM dithiothreitol, 55 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.27 M KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 11% glycerol, 0.2% NP-40, and protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails [Sigma]) and either subjected directly to sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-10% PAGE) or precipitated with trichloroacetic acid and deoxycholate for scintillation counting.

Sucrose gradient analysis of initiation complexes and polysomes.

A total of 5 × 107 PKR−/− cells were lysed with 0.6 ml of lysis buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 400 U of RNasin/ml, Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche], 0.5% NP-40, 2.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 50 μg of cycloheximide/ml [pH 7.5]) and centrifuged at 27,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was applied to a 15 to 45% sucrose density gradient in buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2 [pH 7.5]) containing 50 μg of cycloheximide/ml and then centrifuged in a Beckman SW41Ti rotor at 38,000 rpm at 4°C for 2 h (no brake). Gradients were fractionated (1-ml fractions) with continuous monitoring of the absorbance at 254 nm. To isolate RNA from sucrose gradients, 100 μl from each fraction was spiked with 0.1 ng of in vitro-synthesized green fluorescent protein (GFP) mRNA as an internal standard. RNA was extracted by using an RNeasy 96 kit (Qiagen), followed by two elutions each of 70 μl. Aliquots of 5 μl were then used for quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis (see below).

RT-PCR analysis.

RNA was harvested from intact cells or from polysomal fractions by using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed by using random hexamer primers. Samples were then subjected to qRT-PCR using fLuc-, GFP-, or GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase)-specific primers (in separate reactions) and the SYBR green Q-PCR system (Bio-Rad). Three independent RNA harvests were completed for each fraction, and qRT-PCRs were repeated at least twice for each RNA harvest. The results, therefore, reflect the average of six individual qRT-PCR analyses for each fraction. The GAPDH or fLuc values for each polysome fraction were normalized with the GFP internal control and are presented as a percentage of the total RNA found in all samples. For semiquantitative PCR of the ISG20 RNA, RNA was harvested and reverse transcribed as above and subjected to PCR using ISG20-specific primers.

Western blotting and cell fractionation.

The presence or absence of specific proteins and the failure of eIF2α A/A cells to phosphorylate eIF2α after SB infection was confirmed by using specific antisera reactive with PKR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), general control nonderepressable kinase-2 (GCN2; Cell Signaling Technology), heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), GAPDH, β-actin (Chemicon), total eIF4E or phosphorylated eIF4E, or phosphorylated or total eIF2α (Cell Signaling Technology) after SDS-PAGE (acrylamide concentrations ranged from 7 to 12%) separation of 20 to 50 μg of cellular lysate and nitrocellulose membrane blotting of the proteins. For eIF4E localization studies, cells were fractionated into nuclear, perinuclear, and cytoplasmic fractions as previously described (27); however, the cells were disrupted by passage through a syringe and a 27-gauge needle.

RESULTS

Translation of SB and other cap-dependent virus mRNAs is inhibited in IFN-α/β-treated PKR−/− MEFs.

Previously, we determined that PKR, but not RNase L, inhibited early SB replication in an IFN-α/β receptor signaling-independent manner in infected mouse lymph nodes or bone marrow-derived DC cultures. However, once IFN-α/β signaling occurred in PKR−/− or PKR/RNase L−/− mice or cells, virus replication was suppressed efficiently. Furthermore, translation of reporters mimicking SB or host cell mRNAs electroporated into DCs from PKR/RNase L−/− mice was inhibited by IFN-α/β priming, but translation initiated from the EMCV IRES element was not (43, 44). Initially, we sought to determine whether (i) the IFN-α/β-mediated inhibition of translation was also observed in MEF cultures, which are more amenable to in vitro manipulation; (ii) the method of RNA introduction into the cells influenced the nature of the translation inhibition; (iii) translation of full-length virus genomic RNA was inhibited similarly to the translation reporters; and (iv) translation of other non-IRES-initiated viral mRNAs was similarly sensitive to IFN-α/β priming.

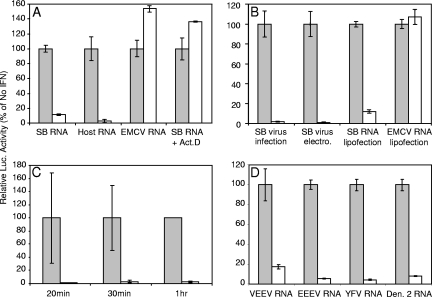

Preliminary studies indicated that IFN-α/β-mediated inhibition of the translation of the electroporated SB reporter was similar in wild-type and PKR−/− MEFs, ranging from 5- to >20-fold depending upon the experiment (Fig. 1A and data not shown). In contrast, translation directed by the EMCV IRES was slightly stimulated by IFN-α/β treatment in the absence of PKR. Furthermore, the IFN-α/β-mediated inhibition of translation in PKR−/− MEF cultures required new gene transcription since cotreatment of the cells with actinomycin D and IFN-α/β abrogated the translation inhibitory effect (Fig. 1A). We then confirmed that IFN-α/β-mediated inhibition was observed after natural virus infection of the PKR−/− MEF cultures by using a SB virus in which the fLuc gene was inserted in frame into the nsP3 gene, resulting in a replication-competent virus that expressed fLuc during translation of nonstructural (nsP) proteins (3, 43) (Fig. 1B). Likewise, translation of a full-length in vitro-transcribed translation-competent but replication-defective SB genome expressing fLuc as an nsP in-frame fusion (3) was inhibited efficiently by IFN-α/β priming of the PKR−/− cells (Fig. 1B). Finally, we obtained similar results regardless of whether the SB or host mimic in vitro-transcribed reporters were introduced into the cells by electroporation or lipid reagent transfection (Fig. 1A and B). In general, the translation-inhibiting effect was more pronounced with replicating reporters (Fig. 1A and B) since, presumably, luciferase expression in the control cells reflected the combination of incoming genome translation and translation of replicated genomes, both of which may have been inhibited, whereas nonreplicating reporters only revealed effects upon initial translation.

FIG. 1.

(A) SB, host mimic, or EMCV RNA reporters were electroporated into mock-treated (gray bars) or IFN-α/β-treated (white bars; 1,000 IU, 6 h) PKR−/− MEFs. Lysates were harvested at 2 h postelectroporation for luciferase analysis. For actinomycin D treatment (0.5 μg/ml), cells were exposed to the drug for 1 h prior to IFN treatment and then incubated for 6 h, followed by electroporation as described above. In these experiments, average relative light units (RLU) in luciferase assays of lysates from untreated cells were in excess of 20,000. (B) Natural infection by particles from a stock of a replication/propagation-competent SB virus with luciferase cloned in-frame into nsP3 (SB virus infection), electroporation of a full-length in vitro-transcribed SB genome with fLuc cloned in-frame in nsP3 but with a defective RNA polymerase (SB virus electro.) or lipid reagent transfection of SB or EMCV-based RNA reporters (SB or EMCV RNA lipofection) were used to examine translation in mock-treated (░⃞) or IFN-α/β-treated (□) PKR−/− MEFs. IFN-α/β treatment and sampling parameters were as in panel A. RLU values in luciferase assays of lysates from untreated cells averaged 2,371 for SB virus infection; all reporters were in excess of 20,000. (C) The SB-based RNA reporter was electroporated into mock-treated (░⃞) or IFN-α/β-treated (as described in panel in A [□]) PKR−/− MEFs. Lysates were harvested for luciferase assay at early times postelectroporation. RLU values in luciferase assays of lysates from untreated cells averaged 1,161 at 20 min, 4,009 at 30 min, and 91,000 at 1 h. (D) Various RNA reporters were electroporated into PKR−/− MEFs as in panel A. Average RLU values in luciferase assays of lysates from untreated cells ranged from 16,545 (Den. 2 RNA) to 148,229 (VEEV RNA). Error bars indicate the standard deviations.

We also examined the kinetics of the development of the inhibitory environment after the introduction of RNA by performing a time course experiment after the electroporation of untreated and IFN-treated PKR−/− MEFs and examining fLuc production at early times (Fig. 1C). At the earliest times that translation of reporters could be detected, IFN-α/β priming inhibited fLuc signal >10-fold, suggesting that the inhibitory effect would be capable of inhibiting very early events in virus infection (e.g., translation of the incoming genome). The large standard deviations in samples taken early after electroporation are reflective of low levels of fLuc signal at these times.

To examine the effects of IFN-α/β priming upon genome translation of more-virulent alphaviruses and non-IRES-containing viruses from another family, we constructed fLuc-expressing reporters analogous to the SB reporter by utilizing sequences of VEEV and EEEV and the 17D strain of YFV and obtained an analogous dengue 2 virus reporter (12). All of these viruses possess a 5′ cap structure; however, the flavivirus reporters, like full-length flavivirus genomes, do not have 3′ poly(A) tracts (12, 30). Translation of each of the nonreplicating reporters was inhibited similarly to the SB-based reporter by IFN-α/β priming of the PKR−/− MEFs (Fig. 1D). In addition, we found that the absence of the poly(A) tract from the SB reporter did not affect the degree of inhibition mediated by IFN-α/β treatment (data not shown). Combined with the inhibition of the host mRNA mimic reporter (Fig. 1A), these data suggest that the IFN-α/β-induced activity is broadly active against cap-dependent translation.

The IFN-α/β-induced inhibitory effect is dependent upon the presence of a cap structure at the 5′ terminus of the mRNA.

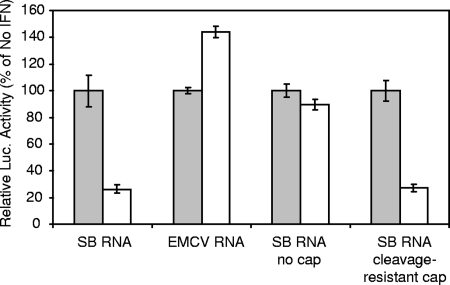

Based upon the above results, we performed additional experiments examining the effect of the presence or absence of a 5′ cap structure. Translation of the uncapped reporter RNA in untreated cells was ∼20 to 100-fold lower than with capped mRNA, reflecting the expected stimulation of translation that this structure provides (see, for example, reference 15; also data not shown). Electroporation of the IFN-α/β-treated PKR−/− cells with SB reporter transcripts generated without a cap analog revealed that the IFN-α/β inhibition was largely abrogated without the cap present (Fig. 2). This result suggested that an IFN-α/β-induced decapping activity might account for the translation inhibition observed. To test this, we electroporated IFN-α/β-treated and untreated cells with transcripts produced using a cap structure (m27,3′-OGppCH2pG) that has been shown to be highly resistant to the Dcp2 decapping enzyme in vitro and to significantly retard RNA degradation in cells (19). The effects of IFN-α/β priming on translation were similar in magnitude if the cleavage-resistant cap was used for transcription (Fig. 2). In addition, RNA stability data (see below) suggest that structural modification of the mRNA did not occur.

FIG. 2.

Mock-treated (░⃞) or IFN-α/β-treated (□) PKR−/− MEFs were electroporated with conventional SB-based or EMCV-based RNA reporters, the SB-based reporter transcribed without cap analog (no cap), or the SB-based reporter transcribed in the presence of cap analog modified by methylene substitution for oxygen between the α and β phosphate moieties of the triphosphate bridge (cleavage-resistant cap) (19). Two hours after electroporation the lysates were harvested for luciferase assay. RLU values in luciferase assays of lysates from untreated cells electroporated with uncapped mRNA averaged 2,336. RLU values averaged 1,239 in untreated cells electroporated with the cleavage-resistant cap; all others were in excess of 20,000. Error bars indicate the standard deviations.

Endogenous or introduced mRNA is not degraded more rapidly in IFN-α/β-treated cells.

Another possibility for the observed IFN-α/β-mediated effect upon translation was enhanced degradation of reporter mRNA in IFN-α/β-treated cells. This idea was further promoted by our identification of two RNases in a global transcription analysis of candidate effectors of PKR-independent IFN-mediated antiviral pathways (43) and the recent indication that the zinc-finger antiviral protein, ZAP, inhibits SB replication by targeting virus genomic RNA to the exosome (20). To test this hypothesis, we compared IFN-α/β-treated and control cells for (i) the integrity of total cellular RNA, (ii) the integrity of translation reporter RNA measured by qRT-PCR after electroporation, and (iii) the translation competence of reporter RNA purified from transfected cells and then re-electroporated into untreated cells.

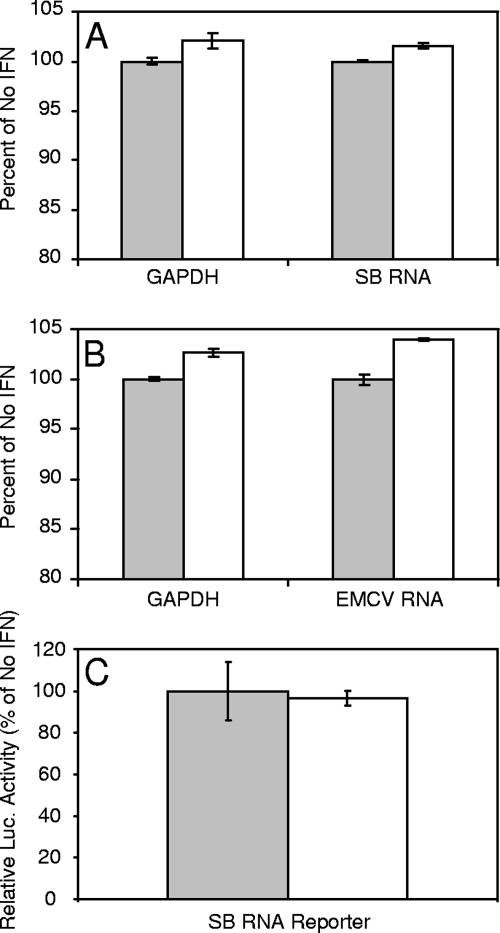

No differences could be detected in the quality of total cellular RNA purified from cells and separated on a 0.7% Tris-borate-EDTA, 0.1% SDS-agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide (data not shown). qRT-PCR analysis of IFN-α/β-treated and control cells that were electroporated with the SB or EMCV reporter RNAs revealed no significant differences in GAPDH or reporter mRNA abundance associated with IFN-α/β treatment (Fig. 3A and B) and further indicated that equal RNA was delivered to the cells. Furthermore, the ability of RNA electroporated into IFN-α/β-treated or untreated cells to initiate translation in untreated cells after harvesting and purification was essentially identical, indicating that structural changes to the RNA were not responsible for the translation inhibiting activity (Fig. 3C). Finally, we were unable to detect differences in the migration or intensity of bands for 32P-labeled mRNA electroporated into IFN-treated or untreated cells and subsequently harvested and separated on polyacrylamide gels (data not shown). These results, along with the susceptibility of mRNA transcribed in the presence of the cleavage-resistant cap structure (described above; Fig. 2), provide strong evidence that the IFN-mediated translation inhibiting activity does not involve structural modification of mRNA.

FIG. 3.

Mock-treated (░⃞) or IFN-α/β-treated (□; 1,000 IU, 6 h) PKR−/− MEFs were electroporated with the SB-based RNA reporter (A and C) or the EMCV-based reporter (B) and harvested for RNA purification at 2 h postelectroporation. In one set of experiments, purified RNA was subjected to qRT-PCR for GAPDH and luciferase (A and B), which would recognize the SB and EMCV reporters. (C) In the remaining experiment, the RNA harvested form mock- or IFN-α/β-treated cells was re-electroporated into separate mock-treated cells, and lysates were prepared for luciferase assay at 2 h post-electroporation. RLU values in luciferase assays of lysates from cells re-electroporated with RNA from untreated cells averaged 4,160. Error bars indicate the standard deviations.

The effect of IFN treatment on introduced mRNA is independent of eIF2α phosphorylation.

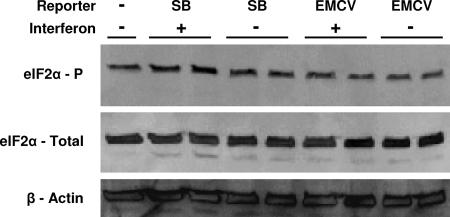

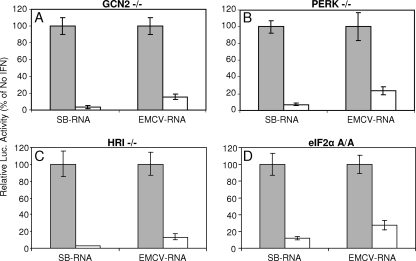

To determine whether the phosphorylation status of eIF2α was altered in IFN-treated PKR−/− cells in which the cap-dependent translation of SB RNA is inhibited, we performed a Western blot analysis (Fig. 4). The results indicated that phosphorylation of eIF2α was not increased by electroporation of the SB reporter RNA or IFN treatment. This was also the case with PKR+/+ cells (data not shown). We also examined the effect of the deletion of the other three kinases capable of modulating cellular translation through phosphorylation of eIF2α—HRI (21), PERK (22), and GCN2 (22)—by completing a translation assay after IFN priming of MEFs deficient in each (Fig. 5A to C). A recent report has indicated that SB RNA can activate GCN2 when added to cell lysates (2). In cells deficient in each of the eIF2α kinases, IFN-α/β-mediated inhibition of SB reporter translation was similar to or greater than that observed with PKR−/− MEFs. However, it remained possible that redundant activities of the different kinases prevented the detection of individual effects. Therefore, we also tested MEFs derived from “knockin” mice expressing a nonphosphorylatable version of eIF2α instead of the normal protein (eIF2α A/A mutant) (49). IFN-α/β-mediated inhibition of SB mRNA translation in these cells was similar to that in the PKR−/− cells (Fig. 5D), confirming that IFN-α/β priming-mediated translation inhibition was independent of eIF2α phosphorylation. Control experiments in which the eIF2α A/A cells were infected with SB virus confirmed the knockin phenotype since the eIF2α was not phosphorylated (data not shown). EMCV translation was consistently inhibited by IFN-α/β treatment in the presence of PKR, confirming the importance of this kinase in the inhibition of picornavirus translation (37). Notably, EMCV IRES-driven translation was also inhibited in IFN-treated eIF2α A/A mutant cells (and in all cells possessing PKR) but not in PKR−/− cells, suggesting a novel, eIF2α phosphorylation-independent, mechanism through which PKR inhibited picornavirus translation.

FIG. 4.

Western blots detecting phosphorylated and total eIF2α in PKR−/− cells either untreated or 2 h after electroporation with SB or EMCV reporters in the presence or absence of IFN pretreatment. Two separate experiments are shown for reporter-electroporated cells. β-Actin staining served as a loading control.

FIG. 5.

Mock-treated (░⃞) or IFN-α/β-treated (□) GCN2−/− (A), PERK−/− (B), HRI−/− (C), or eIF2α A/A (D) MEFs were electroporated with SB- or EMCV-based RNA reporters, and lysates were prepared for luciferase analysis at 2 h postelectroporation. RLU values in luciferase assays of lysates from untreated cells averaged 7,791 for SB-RNA in eIF2α A/A cells and 9,620 for EMCV-RNA in HRI−/− cells; all others were in excess of 20,000. Error bars indicate the standard deviations.

Translation of endogenous mRNAs is relatively unaffected by IFN-α/β treatment of PKR−/− MEFs.

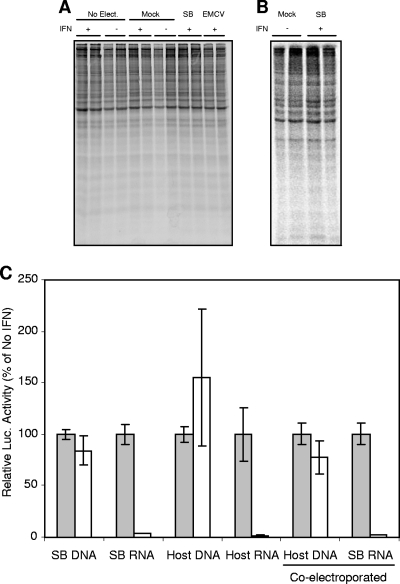

The fact that IFN-α/β treatment of PKR−/− MEFs appeared to have little effect upon cell viability even after extended incubation (data not shown) suggested that host cell translation might not be greatly inhibited by IFN-α/β-induced effectors. In addition, we sought to determine whether the presence of reporter RNA in the electroporation resulted in activation of an IFN-α/β-induced host response pathway that could inhibit overall cellular protein synthesis. We utilized host cell total protein synthesis assays to measure cellular translation at 2 h after mock or reporter electroporation, the same time at which we examined the translation of the fLuc mRNA from the RNA reporters. SDS-PAGE analysis of translation efficiency indicated little difference between the different treatments (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, quantitation of the trichloroacetic acid-precipitable radioactivity from samples of each treatment also indicated that host cell translation was not inhibited by IFN-α/β treatment, the electroporation process itself, or the electroporation of reporter RNA (data not shown). Similar results were obtained when cells were incubated for 12 h after electroporation and then subjected to metabolic labeling, indicating that IFN treatment or reporter RNA electroporation did not have a later effect upon host cell translation (Fig. 6B). The presence or absence of actinomycin D during the labeling portion of the experiments had no effect on translation efficiency, suggesting that differential rates of cellular transcription between treatments did not affect the results (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

(A) Mock-treated or IFN-α/β-treated PKR−/− MEFS were either untreated (No Elect.), electroporated with no RNA (Mock), or electroporated with SB- or EMCV-based RNA reporters and were exposed to radiolabel as described in Materials and Methods for 1 h beginning at 2 h postelectroporation. Lysates were then made, and equal amounts of protein from each lysate were separated via SDS-PAGE analysis, followed by exposure to film. (B) An analysis similar to that shown in panel A was completed at 12 h postelectroporation; however, only using mock- or IFN-treated PKR−/− MEFs electroporated with SB RNA (SB RNA) or electroporated with no RNA (Mock). (C) Mock-treated (░⃞) or IFN-α/β-treated (□) PKR−/− MEFs were electroporated with SB- or host mimic-based RNA reporters or similar reporters encoded on plasmid DNA and transcriptionally regulated by the cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter of pcDNA3.1 (SB-DNA or Host-DNA). Cell lysates were prepared for luciferase analysis at 2 h postelectroporation. Average RLU values in luciferase assays of lysates from untreated cells were in excess of 20,000. Error bars indicate the standard deviations.

The fact that IFN-α/β treatment did not affect overall cellular translation suggested that host mRNAs synthesized in the nucleus might be resistant to the IFN-induced inhibitory activity. Therefore, we constructed plasmid DNAs that reproduced the sequence of the SB RNA and host mRNA mimic reporters under the control of the pcDNA3.1 vector cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter. When introduced into the cells, these reporters would require transport to the nucleus and transcription by host RNA polymerases for reporter mRNA production. Electroporation of either of these reporters into IFN-α/β-treated or control cells revealed little to no effect of IFN-α/β upon reporter translation activity at 2 h postelectroporation (Fig. 6C), which was also observed at earlier and later times (data not shown). These results indicate that mRNA synthesized in the cell nucleus is largely resistant to the IFN-α/β-mediated translation inhibitory effect. We also examined whether or not the presence of the SB reporter activated a factor capable of inhibiting the translation of host mRNA by coelectroporating a Renilla luciferase-expressing plasmid DNA reporter with the firefly luciferase-expressing SB RNA reporter. Dual luciferase assays indicated that translation of the plasmid-derived mRNA was minimally affected in IFN-treated cells in which translation of the RNA reporter was blocked more than 10-fold (Fig. 6C). Together, these data and previously described results demonstrating the effects of IFN treatment upon the RNA reporters at the earliest times postintroduction (Fig. 1C), combined with the limited effect of IFN treatment on overall host protein synthesis in RNA reporter-electroporated cells (Fig. 6A), suggests that the antiviral effect stimulated by IFN treatment may be preexisting in cells and not require viral RNA for activation.

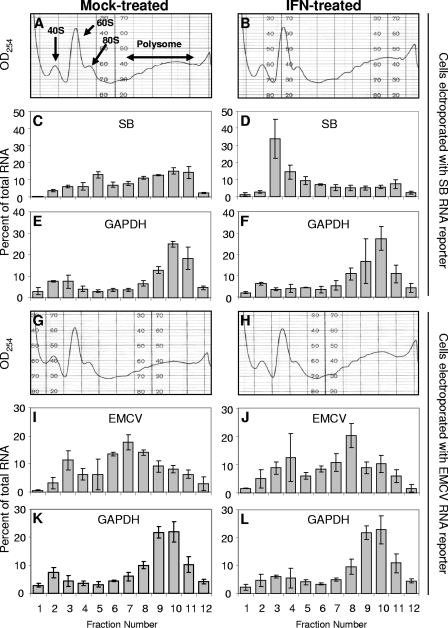

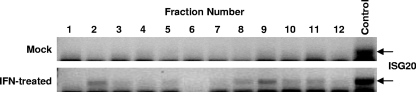

Translation of electroporated cap-dependent mRNA is blocked after the formation of the 48S initiation complex.

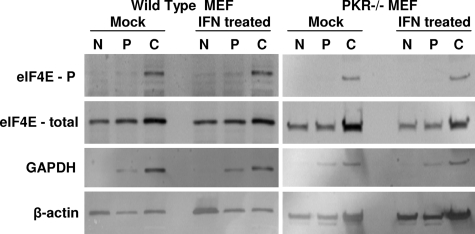

To further assess the affect of IFN-α/β pretreatment on translation of nucleus-synthesized mRNA and to identify the point in translation at which the IFN-α/β-induced activity exerted its effect upon electroporated cap-dependent mRNA, we examined the association of our SB reporter, the EMCV reporter, or a host housekeeping gene mRNA (GAPDH) with complexes that form during initiation by performing polysome gradient analyses, followed by qRT-PCR analyses of the fractions. In this analysis, the association of the reporter luciferase mRNA or endogenously transcribed GAPDH mRNA with each fraction is quantified. Overall, the polysome profiles did not differ significantly regardless of whether or not the cells were IFN-α/β treated or electroporated with reporter SB or EMCV mRNA (Fig. 7A versus B or Fig. 7G versus H). Translation of a typical cellular mRNA such as GAPDH was not affected by IFN-α/β treatment, since there was no change in the distribution between initiation complexes and polysomes (Fig. 7E versus F or Fig. 7K versus L). The peak of EMCV mRNA shifted to a higher fraction after IFN-α/β treatment, a finding indicative of an increase in translation in agreement with the luciferase assay results (Fig. 7I versus J). In contrast, IFN-α/β priming caused a shift of the SB mRNA to more slowly sedimenting structures (Fig. 7C versus Fig. 7D). Without IFN-α/β treatment, the mRNA was efficiently translated, as evidenced by its primary association with heavy polysomes (Fig. 7C, fractions 8 to 11). The percentage of reporter mRNA in initiation complexes (Fig. 7C, fractions 3 and 4) was comparable to that seen with GAPDH mRNA. In IFN-α/β-primed cells, there was a shift in RNA abundance from polysomes to initiation complexes, and the majority of the mRNA was no longer in polysome fractions, a finding consistent with the luciferase expression data that showed a marked decrease in translation. Within the initiation complex region, the highest peak of reporter mRNA sedimented slightly faster than 40S (Fig. 7D, fraction 3). This would be consistent with its presence in a 48S initiation complex rather than a ribonucleoprotein complex. Thus, the data suggest a block occurring at a point after mRNA recruitment to the 43S initiation complex but prior to joining of the 60S subunit. The presence of the reporter mRNA accumulating on 48S initiation complexes after IFN-α/β treatment argues against the defect involving the cap-binding eIF4E or scaffolding eIF4G proteins, at least in terms of their initial participation in the eIF4F complex, binding of mRNA, or recruitment of the small ribosomal subunit. Consistent with this idea, we did not detect changes in the subcellular localization or phosphorylation state of eIF4E after IFN-α/β treatment of wild-type or PKR−/− MEFs (Fig. 8) or the amount of eIF4E retained on a m7G Sepharose column (data not shown). Alterations in the localization or phosphorylation state of the eIF4E have been implicated in the regulation of cap-dependent translation initiation (26, 31). Finally, to test the association of stress-responsive genes with polysome fractions, we performed semiquantitative RT-PCR of mRNA from each fraction using primers specific to the murine ISG20 gene, which we found previously to be IFN inducible in MEFs and to possess anti-alphavirus effects (56). The results demonstrate that the ISG20 mRNA is minimally present in untreated cells but induced by IFN treatment and is associated with heavy polysome fractions (e.g., fractions 8 to 11), suggesting productive translation (Fig. 9).

FIG. 7.

Gradient ultracentrifugation polysome and qRT-PCR analysis of lysates derived from mock-treated (A, C, E, G, I, and K) or IFN-α/β-treated (B, D, F, H, J, and L) PKR−/− MEFs electroporated with SB-based (A to F) or EMCV-based (G to L) RNA reporters harvested at 2 h postelectroporation. Bars represent the average of two repeated sets of triplicate qRT-PCRs from three separate RNA harvests from each fraction (total of six triplicate qRT-PCRs). Error bars indicate the standard deviations.

FIG. 8.

Western blotting for the subcellular localization and phosphorylation state of eIF4E in untreated and IFN-α/β-treated wild-type and PKR−/− MEFs. Cells were treated with 1,000 IU of IFN-α/β/ml for 6 h prior to lysis for fractionation and SDS-PAGE. N, nuclear fraction; P, perinuclear fraction; C, cytoplasmic fraction. Equal protein was loaded in each lane.

FIG. 9.

Semiquantitative PCR for the IFN-inducible ISG20 mRNA in individual fractions of a polysome gradient taken from IFN-treated and untreated PKR−/− cells electroporated with the SB reporter RNA. Numbers correspond to the fractions depicted in Fig. 7, and RNA was harvested and semiquantitative RT-PCR conducted as described in Materials and Methods. The control is a similar RT-PCR of total RNA from IFN-treated cells.

DISCUSSION

Host cell responses designed to inhibit viral pathogens but preserve cellular viability are likely difficult to achieve due to the intimacy with which viral pathogens interact with cellular metabolic machinery and structures. IFN-α/β-mediated antiviral activities will have the largest antiviral effects and least negative consequences for the host if they can distinguish effectively between virus-encoded “nonself” structures and host-encoded “self” structures and effectively target the viral structures. Several systems have evolved to achieve this goal with differing levels of success. For example, molecular pattern receptors that initiate innate immune responses recognize unique viral structures (e.g., dsRNA replicative intermediate recognition by MDA-5 [18], 5′ RNA triphosphate recognition by RIG-I [39, 55]), or single-stranded RNA in an abnormal site within the cell (e.g., single-stranded RNA recognition by endosomal TLR7 [11]). In contrast, the well-characterized IFN-induced antiviral effectors PKR and RNase L have an overlap in specificity between viral and host structures and are implicated in destructive processes in cells, including global inhibition of translation and induction of apoptosis (reviewed in reference 7 and 16).

Based upon the data presented herein, we propose that, in a cell exposed to IFN-α/β, de novo initiation of translation by RNA that enters across the cytoplasmic membrane (e.g., the genome of an infecting positive-sense RNA virus) is recognized as “nonself.” By using this mechanism, the cell is able to inhibit the translation of invading mRNAs by >10-fold while preserving the translation of nuclear transcribed host mRNA and the expression of normal and, perhaps in particular, newly transcribed stress-responsive genes. As our data indicate, the EMCV IRES element is resistant to this effect; however, this antiviral strategy has broad applicability versus cap-dependent positive-sense RNA viruses. Furthermore, although we have not tested the possibility, cap-dependent mRNAs of negative-sense RNA viruses, as well as DNA viruses that transcribe their mRNA in the cytoplasm, may be sensitive.

Several different experimental approaches have independently confirmed that IFN-α/β priming of cells induces a PKR-independent activity that profoundly inhibits the translation of non-nuclear, cap-dependent mRNA entering the cytoplasm: (i) natural infection by replication-competent SB virus particles and lipid transfection or electroporation of SB reporters resulted in inhibition of the earliest gene expression; (ii) similar effects were observed with reporters constructed to mimic a host mRNA or containing the translation control sequences of VEEV, EEEV, YFV, or dengue virus; (iii) the SB reporter RNA was not degraded or altered in its translation competence by exposure to IFN-α/β-treated cells; (iv) synthesis of the SB reporter mRNA without a cap structure abrogated the IFN-induced inhibitory effect; and (v) polysome and qRT-PCR analyses indicated a redistribution of SB reporter RNA out of highly translated fractions and into a fraction that suggested blockage after formation of the 48S complex but before formation of the 80S complex. Work from our laboratory (43, 44) and others has indicated that IFN treatment induces a block in early events after virus infection of cells that may involve inhibition of translation of the infecting genome; however, most of these studies were performed in the presence of PKR (10, 25). Furthermore, these previous studies did not determine that the effect involved inhibition of translation initiation as opposed to structural changes in RNA such as deletion of cap structure or 5′ or 3′ mRNA degradation. Interestingly, the studies of Diamond and Harris with dengue virus (10) did indicate a movement of viral RNA out of polysome fractions in IFN-treated cells (that expressed PKR); however, these researchers did not examine viral mRNA association with initiation structures that sedimented more slowly than 80S (10), the point at which blockage occurs in our studies. The studies reported here are unique in that translation inhibition is demonstrated in cells lacking PKR and multiple lines of evidence are presented that indicate an IFN-mediated block in translation initiation.

We have also provided evidence of the resistance of nucleus-transcribed mRNA to IFN-mediated translation inhibition in the absence of PKR: (i) total host protein synthesis, measured by radioactive label incorporation, was not diminished; (ii) the abundance of mRNA for the housekeeping gene GAPDH was not affected; (iii) the distribution of GAPDH mRNA in polysomes was not altered by IFN-α/β pretreatment regardless of the presence or absence of an inhibited SB reporter RNA; and (iv) SB and host mRNA mimic reporters, when transcribed from DNA plasmids transfected into the cell nucleus, were minimally affected even when coelectroporated with RNA reporters that were inhibited more than 10-fold. Together, these data provide evidence of a host mechanism for IFN-α/β-mediated inhibition of cap-dependent virus mRNA translation that can distinguish between mRNA transcribed in the nucleus and mRNA from other sources. The notion that the translation of viral and cellular RNAs may be differentially targeted by IFN-induced antiviral effectors has precedence in the literature (see, for example, references 24, 25, and 45). However, these earlier studies were all performed in the presence of PKR, rarely considered RNA degradation as a potential mechanism of translation inhibition, and were completed prior to detailed characterization of the host factors and RNA structures required for efficient translation initiation, making it difficult to compare those results to the present study.

Although the IFN-induced translation inhibiting mechanism distinguished between EMCV IRES and cap-dependent translation initiation, much of our evidence implies that effects upon eIF4E cap-binding activity are not involved: (i) the nuclear versus perinuclear and cytoplasmic distribution and phosphorylation state of eIF4E was unchanged in IFN-α/β-treated cells, (ii) the amount of eIF4E capable of binding a m7G cap appeared to be unchanged (data not shown), and (iii) polysome fractionation indicated that the translation block occurred after 40S but before 60S ribosome subunit binding. The fact that IFN-α/β-inhibitory effects were largely abrogated for a mRNA lacking the cap structure may appear to contradict this conclusion; however, it is possible that the minimal residual translation initiation observed with this mRNA does not function through canonical cap-dependent mechanisms and may exhibit resistance to the inhibitory activity similar to IRES-dependent initiation. Ultimately, our data indicate that the IFN-α/β-induced blockage involves other processes that depend upon the presence of a cap structure and differ between cap- and IRES-dependent initiation (37) such as (i) ribosome scanning for the initiation codon and/or the actions initiation factors that promote scanning (35, 36), (ii) blockage of the activities of initiation factors that enable start codon recognition (36, 47), or (iii) blockage of the 60S joining step itself.

The majority of our data were collected in cells that did not express PKR. However, we speculate that the PKR-independent translation inhibitory activity is a major component of the IFN-α/β-induced antiviral response in normal cells. We and others have found that transcription of the PKR gene is often only minimally induced by IFN-α/β treatment of cells (9), whereas the translation inhibitory activity is strongly induced. This is suggestive of PKR-independent activities functioning as important IFN-responsive components of the antiviral state. Furthermore, since PKR activation typically requires the presence of a viral replicative intermediate, PKR-independent inhibitors could act prior to replication of the infecting genome. Clearly, additional investigation will be required to fully characterize this novel antiviral response and identify its IFN-α/β-induced effectors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants 2R01 AI22186 (W.B.K.), 1R21 AI069158 and a Career Development Award from the WRCE (K.D.R.), and 2R01 GM20818 (R.E.R.).

We thank Steven Bachenheimer, Ronald Wek, and Randal Kaufman for providing MEFs.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, S. L., J. M. Carton, J. Lou, L. Xing, and B. Y. Rubin. 1999. Interferon-induced guanylate binding protein-1 (GBP-1) mediates an antiviral effect against vesicular stomatitis virus and encephalomyocarditis virus. Virology 256:8-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berlanga, J. J., I. Ventoso, H. P. Harding, J. Deng, D. Ron, N. Sonenberg, L. Carrasco, and C. de Haro. 2006. Antiviral effect of the mammalian translation initiation factor 2α kinase GCN2 against RNA viruses. EMBO J. 25:1730-1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bick, M. J., J. W. Carroll, G. Gao, S. P. Goff, C. M. Rice, and M. R. Macdonald. 2003. Expression of the zinc-finger antiviral protein inhibits alphavirus replication. J. Virol. 77:11555-11562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binder, D., J. Fehr, H. Hengartner, and R. M. Zinkernagel. 1997. Virus-induced transient bone marrow aplasia: major role of interferon-alpha/beta during acute infection with the noncytopathic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Exp. Med. 185:517-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bredenbeek, P. J., E. A. Kooi, B. Lindenbach, N. Huijkman, C. M. Rice, and W. J. Spaan. 2003. A stable full-length yellow fever virus cDNA clone and the role of conserved RNA elements in flavivirus replication. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1261-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter, C. C., V. Y. Gorbacheva, and D. J. Vestal. 2005. Inhibition of VSV and EMCV replication by the interferon-induced GTPase, mGBP-2: differential requirement for wild-type GTP binding domain. Arch. Virol. 150:1213-1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chawla-Sarkar, M., D. J. Lindner, Y. F. Liu, B. R. Williams, G. C. Sen, R. H. Silverman, and E. C. Borden. 2003. Apoptosis and interferons: role of interferon-stimulated genes as mediators of apoptosis. Apoptosis 8:237-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Despres, P., J. W. Griffin, and D. E. Griffin. 1995. Antiviral activity of alpha interferon in Sindbis virus-infected cells is restored by anti-E2 monoclonal antibody treatment. J. Virol. 69:7345-7348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Veer, M. J., M. Holko, M. Frevel, E. Walker, S. Der, J. M. Paranjape, R. H. Silverman, and B. R. Williams. 2001. Functional classification of interferon-stimulated genes identified using microarrays. J. Leukoc. Biol. 69:912-920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamond, M. S., and E. Harris. 2001. Interferon inhibits dengue virus infection by preventing translation of viral RNA through a PKR-independent mechanism. Virology 289:297-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diebold, S. S., T. Kaisho, H. Hemmi, S. Akira, and C. Reis e Sousa. 2004. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science 303:1529-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edgil, D., M. S. Diamond, K. L. Holden, S. M. Paranjape, and E. Harris. 2003. Translation efficiency determines differences in cellular infection among dengue virus type 2 strains. Virology 317:275-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espert, L., C. Gongora, and N. Mechti. 2003. Interferon: antiviral mechanisms and viral escape. Bull. Cancer 90:131-141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiette, L., C. Aubert, U. Muller, S. Huang, M. Aguet, M. Brahic, and J. F. Bureau. 1995. Theiler's virus infection of 129Sv mice that lack the interferon alpha/beta or interferon gamma receptors. J. Exp. Med. 181:2069-2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fletcher, L., S. D. Corbin, K. S. Browning, and J. M. Ravel. 1990. The absence of a m7G cap on beta-globin mRNA and alfalfa mosaic virus RNA 4 increases the amounts of initiation factor 4F required for translation. J. Biol. Chem. 265:19582-19587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia, M. A., J. Gil, I. Ventoso, S. Guerra, E. Domingo, C. Rivas, and M. Esteban. 2006. Impact of protein kinase PKR in cell biology: from antiviral to antiproliferative action. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:1032-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Sastre, A., R. K. Durbin, H. Zheng, P. Palese, R. Gertner, D. E. Levy, and J. E. Durbin. 1998. The role of interferon in influenza virus tissue tropism. J. Virol. 72:8550-8558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gitlin, L., W. Barchet, S. Gilfillan, M. Cella, B. Beutler, R. A. Flavell, M. S. Diamond, and M. Colonna. 2006. Essential role of mda-5 in type I IFN responses to polyriboinosinic:polyribocytidylic acid and encephalomyocarditis picornavirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:8459-8464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grudzien, E., M. Kalek, J. Jemielity, E. Darzynkiewicz, and R. E. Rhoads. 2006. Differential inhibition of mRNA degradation pathways by novel cap analogs. J. Biol. Chem. 281:1857-1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo, X., J. Ma, J. Sun, and G. Gao. 2007. The zinc-finger antiviral protein recruits the RNA processing exosome to degrade the target mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:151-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han, A. P., C. Yu, L. Lu, Y. Fujiwara, C. Browne, G. Chin, M. Fleming, P. Leboulch, S. H. Orkin, and J. J. Chen. 2001. Heme-regulated eIF2α kinase (HRI) is required for translational regulation and survival of erythroid precursors in iron deficiency. EMBO J. 20:6909-6918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harding, H. P., I. Novoa, Y. Zhang, H. Zeng, R. Wek, M. Schapira, and D. Ron. 2000. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell 6:1099-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang, S. Y., P. J. Hertzog, K. A. Holland, S. H. Sumarsono, M. J. Tymms, J. A. Hamilton, G. Whitty, I. Bertoncello, and I. Kola. 1995. A null mutation in the gene encoding a type I interferon receptor component eliminates antiproliferative and antiviral responses to interferons alpha and beta and alters macrophage responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11284-11288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs, B. L., N. G. Miyamoto, and C. E. Samuel. 1988. Mechanism of interferon action: studies on the activation of protein phosphorylation and the inhibition of translation in cell-free systems. J. Interferon Res. 8:617-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joklik, W. K., and T. C. Merigan. 1966. Concerning the mechanism of action of interferon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 56:558-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koritzinsky, M., M. G. Magagnin, T. van den Beucken, R. Seigneuric, K. Savelkouls, J. Dostie, S. Pyronnet, R. J. Kaufman, S. A. Weppler, J. W. Voncken, P. Lambin, C. Koumenis, N. Sonenberg, and B. G. Wouters. 2006. Gene expression during acute and prolonged hypoxia is regulated by distinct mechanisms of translational control. EMBO J. 25:1114-1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lejbkowicz, F., C. Goyer, A. Darveau, S. Neron, R. Lemieux, and N. Sonenberg. 1992. A fraction of the mRNA 5′ cap-binding protein, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E, localizes to the nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:9612-9616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenschow, D. J., N. V. Giannakopoulos, L. J. Gunn, C. Johnston, A. K. O'Guin, R. E. Schmidt, B. Levine, and H. W. Virgin. 2005. Identification of interferon-stimulated gene 15 as an antiviral molecule during Sindbis virus infection in vivo. J. Virol. 79:13974-13983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenschow, D. J., C. Lai, N. Frias-Staheli, N. V. Giannakopoulos, A. Lutz, T. Wolff, A. Osiak, B. Levine, R. E. Schmidt, A. Garcia-Sastre, D. A. Leib, A. Pekosz, K. P. Knobeloch, I. Horak, and H. W. Virgin. 2007. IFN-stimulated gene 15 functions as a critical antiviral molecule against influenza, herpes, and Sindbis viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:1371-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo, M. K., M. Tilgner, K. A. Bernard, and P. Y. Shi. 2003. Functional analysis of mosquito-borne flavivirus conserved sequence elements within 3′ untranslated region of West Nile virus by use of a reporting replicon that differentiates between viral translation and RNA replication. J. Virol. 77:10004-10014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minich, W. B., M. L. Balasta, D. J. Goss, and R. E. Rhoads. 1994. Chromatographic resolution of in vivo phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF-4E: increased cap affinity of the phosphorylated form. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7668-7672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mrkic, B., J. Pavlovic, T. Rulicke, P. Volpe, C. J. Buchholz, D. Hourcade, J. P. Atkinson, A. Aguzzi, and R. Cattaneo. 1998. Measles virus spread and pathogenesis in genetically modified mice. J. Virol. 72:7420-7427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muller, U., U. Steinhoff, L. F. Reis, S. Hemmi, J. Pavlovic, R. M. Zinkernagel, and M. Aguet. 1994. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science 264:1918-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patterson, J. B., and C. E. Samuel. 1995. Expression and regulation by interferon of a double-stranded-RNA-specific adenosine deaminase from human cells: evidence for two forms of the deaminase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5376-5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pestova, T. V., S. I. Borukhov, and C. U. Hellen. 1998. Eukaryotic ribosomes require initiation factors 1 and 1A to locate initiation codons. Nature 394:854-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pestova, T. V., and V. G. Kolupaeva. 2002. The roles of individual eukaryotic translation initiation factors in ribosomal scanning and initiation codon selection. Genes Dev. 16:2906-2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pestova, T. V., V. G. Kolupaeva, I. B. Lomakin, E. V. Pilipenko, I. N. Shatsky, V. I. Agol, and C. U. Hellen. 2001. Molecular mechanisms of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7029-7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfefferkorn, E. R. 1984. Interferon gamma blocks the growth of Toxoplasma gondii in human fibroblasts by inducing the host cells to degrade tryptophan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:908-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pichlmair, A., O. Schulz, C. P. Tan, T. I. Naslund, P. Liljestrom, F. Weber, and C. Reis e Sousa. 2006. RIG-I-mediated antiviral responses to single-stranded RNA bearing 5′-phosphates. Science 314:997-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ritchie, K. J., C. S. Hahn, K. I. Kim, M. Yan, D. Rosario, L. Li, J. C. de la Torre, and D. E. Zhang. 2004. Role of ISG15 protease UBP43 (USP18) in innate immunity to viral infection. Nat. Med. 10:1374-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryman, K. D., W. B. Klimstra, K. B. Nguyen, C. A. Biron, and R. E. Johnston. 2000. Alpha/beta interferon protects adult mice from fatal Sindbis virus infection and is an important determinant of cell and tissue tropism. J. Virol. 74:3366-3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryman, K. D., K. C. Meier, C. L. Gardner, and W. B. Klimstra. 2007. Non-pathogenic Sindbis virus causes viral hemorrhagic fever in the absence of alpha/beta and gamma interferons. Virology 368:273-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryman, K. D., K. C. Meier, E. M. Nangle, S. L. Ragsdale, N. L. Korneeva, R. E. Rhoads, M. R. Macdonald, and W. B. Klimstra. 2005. Sindbis virus translation is inhibited by a PKR/RNase L-independent effector induced by alpha/beta interferon priming of dendritic cells. J. Virol. 79:1487-1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryman, K. D., L. J. White, R. E. Johnston, and W. B. Klimstra. 2002. Effects of PKR/RNase L-dependent and alternative antiviral pathways on alphavirus replication and pathogenesis. Viral Immunol. 15:53-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samuel, C. E., and W. K. Joklik. 1974. A protein synthesizing system from interferon-treated cells that discriminates between cellular and viral messenger RNAs. Virology 58:476-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scheuner, D., B. Song, E. McEwen, C. Liu, R. Laybutt, P. Gillespie, T. Saunders, S. Bonner-Weir, and R. J. Kaufman. 2001. Translational control is required for the unfolded protein response and in vivo glucose homeostasis. Mol. Cell 7:1165-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh, C. R., C. Curtis, Y. Yamamoto, N. S. Hall, D. S. Kruse, H. He, E. M. Hannig, and K. Asano. 2005. Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5 is critical for integrity of the scanning preinitiation complex and accurate control of GCN4 translation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:5480-5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steinhoff, U., U. Muller, A. Schertler, H. Hengartner, M. Aguet, and R. M. Zinkernagel. 1995. Antiviral protection by vesicular stomatitis virus-specific antibodies in alpha/beta interferon receptor-deficient mice. J. Virol. 69:2153-2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sudhakar, A., A. Ramachandran, S. Ghosh, S. E. Hasnain, R. J. Kaufman, and K. V. Ramaiah. 2000. Phosphorylation of serine 51 in initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) promotes complex formation between eIF2α(P) and eIF2B and causes inhibition in the guanine nucleotide exchange activity of eIF2B. Biochemistry 39:12929-12938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanaka, Y., H. Marusawa, H. Seno, Y. Matsumoto, Y. Ueda, Y. Kodama, Y. Endo, J. Yamauchi, T. Matsumoto, A. Takaori-Kondo, I. Ikai, and T. Chiba. 2006. Anti-viral protein APOBEC3G is induced by interferon-alpha stimulation in human hepatocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 341:314-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang, C., J. Pflugheber, R. Sumpter, Jr., D. L. Sodora, D. Hui, G. C. Sen, and M. Gale, Jr. 2003. Alpha interferon induces distinct translational control programs to suppress hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 77:3898-3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.White, L. J., J. G. Wang, N. L. Davis, and R. E. Johnston. 2001. Role of alpha/beta interferon in Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus pathogenesis: effect of an attenuating mutation in the 5′ untranslated region. J. Virol. 75:3706-3718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang, Y. L., L. F. Reis, J. Pavlovic, A. Aguzzi, R. Schafer, A. Kumar, B. R. Williams, M. Aguet, and C. Weissmann. 1995. Deficient signaling in mice devoid of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. EMBO J. 14:6095-6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yeung, M. C., and A. S. Lau. 1998. Tumor suppressor p53 as a component of the tumor necrosis factor-induced, protein kinase PKR-mediated apoptotic pathway in human promonocytic U937 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273:25198-25202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoneyama, M., M. Kikuchi, T. Natsukawa, N. Shinobu, T. Imaizumi, M. Miyagishi, K. Taira, S. Akira, and T. Fujita. 2004. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat. Immunol. 5:730-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang, Y., C. W. Burke, K. D. Ryman, and W. B. Klimstra. 2007. Identification and characterization of interferon-induced proteins that inhibit alphavirus replication. J. Virol. 81:11246-11255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou, A., J. M. Paranjape, S. D. Der, B. R. Williams, and R. H. Silverman. 1999. Interferon action in triply deficient mice reveals the existence of alternative antiviral pathways. Virology 258:435-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]