Abstract

MADS-box genes are key components of the networks that control the transition to flowering and flower development, but their role in vegetative development is poorly understood. This article shows that the sister gene of the AGAMOUS (AG) clade, AGL12, has an important role in root development as well as in flowering transition. We isolated three mutant alleles for AGL12, which is renamed here as XAANTAL1 (XAL1): Two alleles, xal1-1 and xal1-2, are in Columbia ecotype and xal1-3 is in Landsberg erecta ecotype. All alleles have a short-root phenotype with a smaller meristem, lower rate of cell production, and abnormal root apical meristem organization. Interestingly, we also encountered a significantly longer cell cycle in the strongest xal1 alleles with respect to wild-type plants. Expression analyses confirmed the presence of XAL1 transcripts in roots, particularly in the phloem. Moreover, XAL1∷β-glucuronidase expression was specifically up-regulated by auxins in this tissue. In addition, mRNA in situ hybridization showed that XAL1 transcripts were also found in leaves and floral meristems of wild-type plants. This expression correlates with the late-flowering phenotypes of the xal1 mutants grown under long days. Transcript expression analysis suggests that XAL1 is an upstream regulator of SOC, FLOWERING LOCUS T, and LFY. We propose that XAL1 may have similar roles in both root and aerial meristems that could explain the xal1 late-flowering phenotype.

Normal morphogenesis depends on the equilibrium between cell proliferation and differentiation (i.e. cellular homeostasis), whereas transcriptional regulatory networks reliably translate genetic information to yield specific and complex multicellular patterning. In both animals and plants, elegant models of pattern formation have suggested the existence of mechanisms that determine developmental identities in precise manners (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991; Lawrence and Morata, 1994). Dynamic regulatory network models have substantiated the existence of these mechanisms (von Dassow and Odell, 2002; Espinosa-Soto et al., 2004). Only recently, molecular links between mechanisms that underlie cell-type specification and cell-cycle regulation have been demonstrated (Caro et al., 2007).

The MADS-box gene family encodes a large variety of transcriptional regulators of plant and animal development (Messenguy and Dubois, 2003). These transcription factors have been classified into two classes based on sequence relationships and structural features (type I and II lineages) that should have derived from at least one ancestral duplication before the divergence of animals and plants (Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2000b). Therefore, plant type I is closely related to the animal SRF factors, whereas plant type II is more similar to the MEF type of animals in their MADS domains than to plant type I. However, type II MADS-domain proteins of plants have three domains (I, K, C) in addition to the MADS DNA-binding domain: a small I domain that links the MADS with the dimerization K domain and the COOH domain (Riechmann and Meyerowitz, 1997).

Plant MIKC genes have been mostly characterized as regulators of the transition to flowering (Samach et al., 2000) and flower, fruit, and seed development (Bowman et al., 1991; Gu et al., 1998; Ferrandiz et al., 2000; Nesi et al., 2002; Pinyopich et al., 2003). They are fairly specific meristem- (Mandel et al., 1992; Bowman et al., 1993), cell- (Liljegren et al., 2000), or organ-identity (Yanofsky et al., 1990; Pelaz et al., 2000) genes. However, genome-wide studies suggest that most MADS-box genes are expressed at different stages of the plant's life cycle and in a variety of organs and cell types (Kofuji et al., 2003; for review, see Rijpkema et al., 2007), suggesting that these genes may have developmental roles that affect multiple tissues and organs.

Given the high sequence conservation of MADS domains of plant and animal proteins within each lineage (I and II), we hypothesized that some of their functions may also have been conserved. Animal MEF-related MADS proteins have been implicated in regulation of cellular homeostasis and linked to cell-cycle control (Lazaro et al., 2002). Therefore, we proposed that some plant MIKC genes might be important modulators of cell proliferation versus differentiation decisions. Moreover, quantitative cellular analyses of MADS-box mutants may help to further understand the role of these genes in various plant developmental processes.

We have focused on MADS-box genes expressed in the root because this organ is transparent and simple at the cellular level, enabling quantitative analyses of cell dynamics (Dolan et al., 1993; Malamy and Benfey, 1997). Indeed, the root has become a very useful system for unraveling general features of multicellular developmental mechanisms (Benfey and Scheres, 2000; Chapman et al., 2003; Wildwater et al., 2005), and specifically for understanding the links between cellular dynamics and cell-type specification during normal morphogenesis of a complex organ in vivo (Sabatini et al., 2003; Wildwater et al., 2005; Caro et al., 2007). Some components of the molecular mechanisms involved in stem-cell niche patterning and behavior (Sablowski, 2004a; Sarkar et al., 2007), as well as in the patterns of cell proliferation along morphogenetic gradients, which in the root are importantly determined by auxins, have been characterized (Sabatini et al., 1999; Galinha et al., 2007; Grieneisen et al., 2007).

In this study, we report the characterization of AGL12 based on three alleles (two in the Columbia [Col] background and one in the Landsberg erecta [Ler] background) that we have named xaantal1 (xal1) due to its short-root and late-flowering phenotypes (xaantal: “to take longer” in Mayan), thus also renaming the AGL12 gene XAL1. XAL1 is the sister gene to the AGAMOUS (AG)-related genes that are specific for reproductive tissues. In contrast, XAL1 was characterized as a root-specific gene (Rounsley et al., 1995). Here, we confirm that XAL1 is indeed expressed in roots, but we report its expression also in aerial organs. Our data suggest that XAL1 is an important regulator of cell proliferation in the root. XAL1 mutant alleles have short roots with an altered cell production rate, meristem size, and cell-cycle duration, and thus XAL1 is the first MADS-box gene that is shown to be involved in cell-cycle regulation. Auxins have been implicated in cell-cycle regulation (Himanen et al., 2002; Vanneste et al., 2005) and our data interestingly show that XAL1 is induced by auxins. On the other hand, xal1 alleles are also late flowering and our data suggest that XAL1 could be an important promoter of the flowering transition through up-regulation of SOC, FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), and LFY.

RESULTS

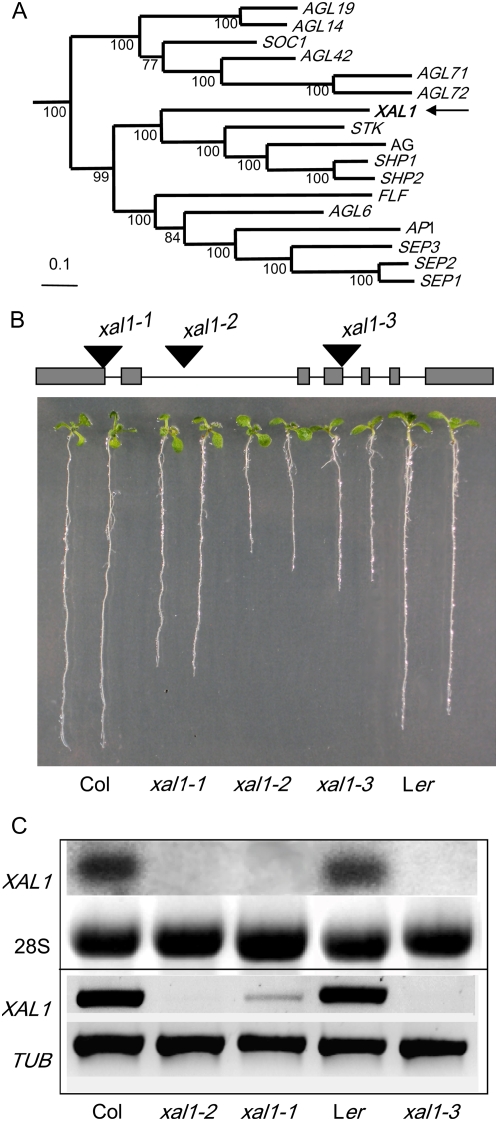

XAL1, a Sister Gene of the AGAMOUS MADS-Box Clade, Is an Important Regulator of Root Development

Sequence analysis of XAL1 indicated that this gene is a member of the MADS-box transcription factor family (Fig. 1A) and recent phylogenetic analyses suggested that XAL1 is sister to the rest of the AG-related genes (Martínez-Castilla and Alvarez-Buylla, 2003; Parenicová et al., 2003). However, contrary to the other members of the AG clade, the expression of XAL1 is not restricted to reproductive organs because it is strongly expressed in roots (Rounsley et al., 1995; Burgeff et al., 2002). To further characterize this gene at the functional level, we isolated three xal1 mutant alleles (Fig. 1B). The xal1-1 allele has an En-1 transposon insertion (Baumann et al., 1998) in the first exon of XAL1 and the xal1-2 allele is a T-DNA insertion in the second intron (see “Materials and Methods”), both in the Col-0 background. The third allele, xal1-3, is in the Ler background and is a stable transposon mutant allele with the insertion at the end of the fourth exon (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

XAL1 phylogeny and seedling mutant phenotypes. A, Bayesian reconstruction of the phylogenetic relationships among selected type II Arabidopsis MADS-box genes, with XAL1 position indicated by an arrow. Numbers under the branches represent Bayesian posterior probability and can be interpreted as a measure of clade statistical support. B, Seedlings phenotype. Ten-day-old wild-type (Col-0 and Ler ecotypes) and xal1-1, xal1-2, and xal1-3 alleles were grown on vertical 0.2× Murashige and Skoog plates. On the top, XAL1 gene schematic model with the sites of transposon or T-DNA insertions are shown. C, XAL1 expression in root tissue from 14-d-old seedlings. Total RNA of both wild-type ecotypes and xal1 alleles were subject to northern-blot hybridization (10 μg/lane; top) and semiquantitative RT-PCR. 28S and TUBULIN were used as internal load controls, respectively.

In all three mutant alleles, the primary root was shorter than in wild-type plants. xal1-1 seedlings showed a root length intermediate between wild type and xal1-2 and xal1-3 (Fig. 1B), probably due to somatic reversion of this unstable transposon allele that occurred after several generations. We performed northern-blot and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR to corroborate XAL1 mRNA levels in roots of the three mutant alleles. RT-PCR detected low expression of XAL1 in the xal1-1 allele, which correlates with its intermediate phenotype, whereas the other two alleles had no expression of XAL1 mRNA (Fig. 1C).

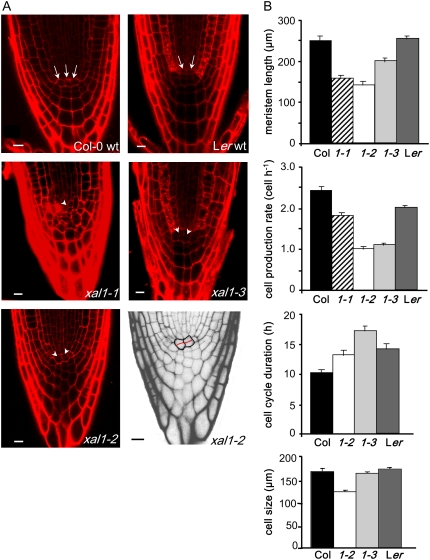

To test whether the shorter roots of the three alleles could be due to altered cellular organization at the root tip, we analyzed 20 roots of each mutant allele under a confocal microscope. About 30% of the plants of all three alleles showed abnormal root apical meristem (RAM) organization, with the quiescent center (QC) and columella being most affected (see examples in Fig. 2A). In a median optical section, the columella initial cells and QC cells could not be clearly recognized and the general meristem organization resembled an open-type RAM (Baum et al., 2002; Chapman et al., 2003). As a result of this disorganization, the root-cap protoderm initials giving rise to both protoderm (epidermis) and lateral root cap were abnormal in shape or could not be detected. Typical T divisions in the epidermis could be detected only in the distal portion of the RAM. This abnormal organization led to an altered columella cell differentiation. Whereas in wild-type plants these cells usually increase in length in each subsequent tier along the root axis toward the distal root end (Fig. 2A), in the affected xal1 plants the columella cells in the root cap were of similar size along the root axis, being almost isodiametric rather than elongated as in wild-type plants (Fig. 2A; data not shown).

Figure 2.

Root phenotype of xal1 mutants. A, Open meristem organization in xal1 alleles. Seven-day-old seedlings were stained with propidium iodide and analyzed by confocal microscopy. QC cells of wild type (arrows) and mutants (arrowhead) of representative phenotypes are shown (bar = 10 μm). Black-and-white zoom picture of xal1-2 is shown to highlight abnormal periclinal divisions at the QC and deformed columella cells. B, Root cellular parameter analyses. Meristem length of 20 independent plants was measured from Col-0 and Ler wild-type plants and xal1-1, xal1-2, and xal1-3 alleles (1-1, 1-2, 1-3). Cell production rate, cell-cycle duration, and fully elongated cell length were obtained as described in “Materials and Methods.” Bars = ses, calculated with JMP, version 5.1.1, statistical package (see data in Supplemental Table S1).

To further understand the observed shorter root phenotypes, we undertook quantitative cellular analyses of all xal1 alleles. We have set up a protocol to document a series of cellular parameters geared to establish the role of root MADS-box or other types of genes in cellular homeostasis using the root as a study system (see “Materials and Methods”; Supplemental Table S1). These analyses revealed that all three alleles have a shortened meristem with a significantly lower rate of cell production, and xal1-2 and xal1-3 have longer cell-cycle duration than in wild-type plants (Fig. 2B). In all cell parameters quantified, xal1-1 showed milder phenotypes than xal1-2 and xal1-3 alleles (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Table S1). Therefore, XAL1 constitutes the first MADS-box gene that affects cell-cycle duration and for which quantitative cellular data have been put forward to evaluate the role of these genes in regulating cell proliferation within the RAM.

Given that xal1 mutants have significantly affected rates of cell production and cell-cycle duration, as well as an altered apico-basal pattern of cell behavior, XAL1 could be regulated by auxin or XAL1 could mediate responses to auxin in the root. Gradients and movement in the root of this plant hormone are sufficient to guide root growth by affecting cell behavior in a dose-dependent fashion (Sabatini et al., 1999; Galinha et al., 2007; Grieneisen et al., 2007). Maximal auxin levels maintain cell quiescence, intermediate levels promote cell proliferation, and lower levels induce cell elongation and differentiation (Galinha et al., 2007; Grieneisen et al., 2007).

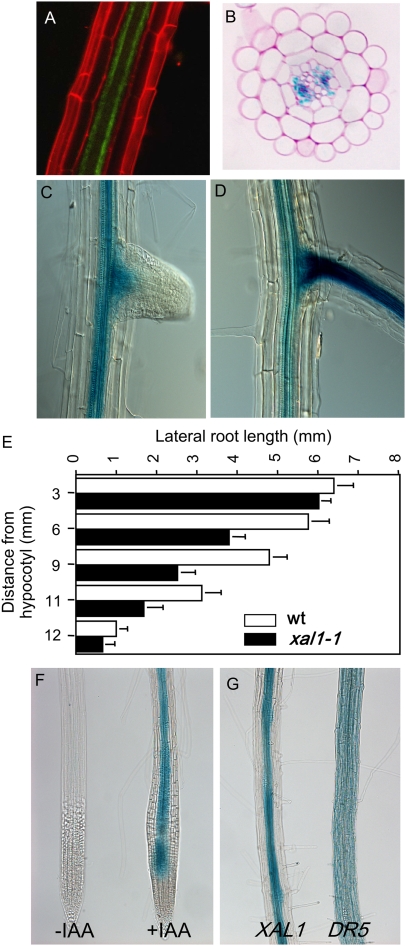

XAL1 Is Expressed in the Phloem Tissue and XAL1∷GUS Is Positively Induced by Auxins

To test whether XAL1 responds to auxin levels, we constructed transgenic lines with a 2.8-kb XAL1 promoter region driving the expression of GFP (XAL1∷GFP; Fig. 3A) and GUS (XAL1∷GUS; Fig. 3B). In the root of 8-d-old plants, GUS expression was detected in the vascular cylinder after 24-h staining, starting from the elongation zone at the level where no signs of protoxylem differentiation were as yet detectable (Fig. 3B; data not shown). XAL1 promoter activity in the differentiation zone was associated predominantly with protophloem cells (Fig. 3B). These results were confirmed with independent XAL1∷GFP transgenic lines, which also reported the expression of the XAL1 promoter in the root phloem in an identical pattern observed in XAL1∷GUS lines (Fig. 3A). Additionally, 6.8-kb promoter constructs, as well as mRNA in situ hybridization (data not shown), revealed expression in the phloem. However, in situ data (Burgeff et al., 2002) also showed expression of XAL1 in the root meristem that could not be recovered in the lines of these constructs, probably due to the absence of the second regulatory intron.

Figure 3.

XAL1 phloem expression is induced by auxins. A, Confocal image of an XAL1∷GFP line taken at the protophloem plane, counterstained with propidium iodide. B, Transverse section of root XAL1∷GUS line after GUS staining, counterstained with ruthenium red. C and D, XAL1∷GUS expression in two different stages of lateral root development. E, Lateral root length along the primary root axis of the wild type (wt) and xal1-1 allele (n = 15 plants; bars = ses). F, XAL1∷GUS expression without (−IAA) and with (+IAA 2 μm). G, IAA-induced phloem GUS activity driven by the XAL1 promoter (left) compared to the broad expression of the DR5∷GUS line (right), after they were both treated with IAA (2 μm).

During lateral root formation, XAL1∷GUS expression became visible only after root emergence, and the pattern was similar to that observed in the primary root (Fig. 3, C and D). This pattern of GUS activity driven by the XAL1 promoter correlated well with a significant reduction also in lateral root length of the xal1-1 plants compared to the wild-type plants (Fig. 3E).

Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) treatment clearly induced GUS activity driven by the XAL1 promoter (Fig. 3F). Interestingly, GUS expression was intensified only in the phloem tissue (Fig. 3G, left). In contrast, the DR5(7X)∷GUS line in the wild-type background (Ulmasov et al., 1997) showed an expanded GUS activity domain that was found in all cell types when the roots were treated with auxins (Fig. 3G, right).

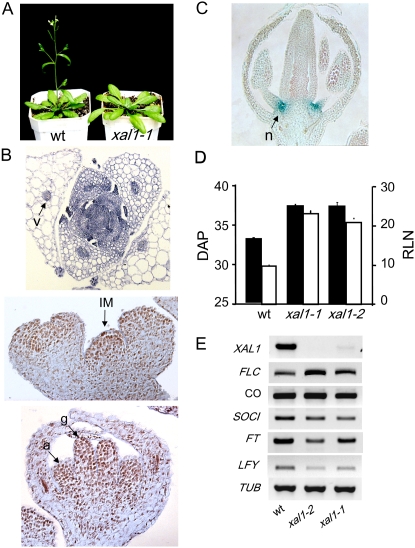

XAL1 Is a Positive Regulator of Flowering Transition That Responds to Photoperiod and Up-Regulates SOC1, FT, and LFY

While analyzing the xal1 mutants, we realized that the plants were late flowering (Fig. 4A) and we decided to pursue this phenotype and explore whether XAL1 was expressed in aerial tissues. Indeed, in situ hybridization of XAL1 mRNA revealed expression in floral meristems and also in vascular tissues in leaves (Fig. 4B). Detailed analyses of GUS activity in flower sections demonstrated that XAL1∷GUS was specifically expressed in young flower meristems, subsequently becoming restricted to the nectaries (Fig. 4C), which contain phloem cells (Baum et al., 2001).

Figure 4.

Flowering phenotype of xal1-1 and xal1-2 mutants and XAL1 role in the photoperiod pathway. A, Late-flowering transition phenotype of the xal1-1 mutant compared to wild-type plants. Both plants were 32 d old. B, XAL1 mRNA in situ hybridizations. XAL1 expression (arrows) in vascular tissue (v) of a 20 d after planting (DAP) vegetative shoot transverse section (top); in the inflorescence meristem (IM) longitudinal section (middle); and in the gynoecium (g) and anthers of a floral meristem (bottom). C, GUS expression in a floral bud longitudinal section of the XAL1∷GUS line. Strong GUS staining corresponds to the nectaries (n). D, Late-flowering phenotype of xal1 mutants. Bolting time scored by DAP at bolting (see data for LD; Table I) in black bars and total rosette leaf number (RLN) in white bars of xal1-1 and xal1-2 alleles compared to wild-type plants (wt). E, Comparative transcript accumulation of genes that participate in the photoperiod and integrative flowering pathways. Gene expression levels were analyzed in the shoots of 14-d-old seedlings of wild type and xal1 mutants by RT-PCR. TUBULIN was included as a constitutive control. A to E, Plants were grown under LD photoperiods.

We further characterized the late-flowering phenotype of the xal1-1 and xal1-2 mutants both in the Col-0 background. The most striking characteristic of these mutants was the significant delay in flowering time measured by the bolting time and the total number of rosette leaves observed under long-day (LD) photoperiods (16 h/8 h) in comparison to wild-type plants (Fig. 4D).

Flowering time is regulated in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) by a network of signaling elements that can be assigned to at least four different pathways (Boss et al., 2004): one that promotes flowering in response to LD photoperiods, one that is essential for flowering under noninductive short-day condition (SD) and depends on the plant hormone GA, one that operates both under LD and SD conditions (also called autonomous pathway), and one that regulates flowering time in response to vernalization (Blazquez et al., 1998; Koornneef et al., 1998b; Blazquez and Weigel, 2000; Putterill, et al., 2004). In our experiments, both xal1 mutants flowered almost concurrently as wild-type plants under SD conditions (Table I). Moreover, vernalization or GA3 application rescued the flowering-time defects of xal1 plants to the same extent as in wild-type plants under LD photoperiods (Table I). Thus, XAL1 does not seem necessary for the integrity of the autonomous, GA, or vernalization pathways, but seems to be specifically necessary for the correct functioning of the photoperiod flowering pathway (Koornneef et al., 1998a; Imaizumi and Kay, 2006).

Table I.

Bolting time of xal1-1 and xal1-2 mutant plants compared to wild type (Col-0) at different flowering-transition pathways

Days after sowing are expressed as mean ± se and results for LD photoperiod are statistically significant. Flowering-time measurements and conditions for LD and SD photoperiods and both of them after vernalization (+VER) and gibberellin (+GA3) treatments, respectively, are explained in “Materials and Methods.”

| Plant Line | Growth Conditions

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD | LD + VER | SD | SD + GA3 | |

| Col-0 | 33.1 ± 0.4 (n = 78) | 25.2 ± 0.6 (n = 37) | 70.0 ± 0.7 (n = 38) | 44.0 ± 0.5 (n = 21) |

| xal1-1 | 37.5 ± 0.5 (n = 48) P < 0.0001 | 28.0 ± 1.9 (n = 41) | 68.1 ± 1.9 (n = 18) | – |

| xal1-2 | 37.4 ± 0.4 (n = 70) P < 0.0001 | 26.9 ± 0.5 (n = 46) | 71.7 ± 0.7 (n = 27) | 44.5 ± 0.5 (n = 21) |

To confirm a possible genetic interaction between XAL1 and previously characterized genetic components of the photoperiod and other integrators of flowering transition pathways (Reeves and Coupland, 2000; Moon et al., 2003), we analyzed mRNA expression of a number of genes known to be key regulators of flowering transition (Fig. 4E). First, we confirmed that XAL1 mRNA levels were reduced in the shoot of both mutants. Indeed, xal1-1 has drastically reduced levels of expression and in xal1-2 we were unable to detect any mRNA expression (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, the flowering promoters FT, SOC, and LFY were clearly reduced at the mRNA level with respect to wild type in both xal1-1 and xal1-2 mutant backgrounds (Fig. 4E). In contrast, CONSTANS (CO) and GIGANTEA (GI; data not shown), which are upstream regulators in the photoperiod pathway (Mouradov et al., 2002), did not show significant alterations in mRNA expression in the xal1 mutants in the Col-0 background. Furthermore, XAL1 is down-regulated in the co-1 background, although it is not totally repressed (Supplemental Fig. S1). On the other hand, FLC, which is a flowering repressor and acts over FT and SOC (Michaels and Amasino, 1999; Searle et al., 2006), showed a slight up-regulation with respect to wild-type plants in both of the xal1 mutants studied. The latter results also correlate with the late-flowering phenotypes of these xal1 alleles.

DISCUSSION

We have shown here that the Arabidopsis MADS-box gene, XAL1, is required for normal root development and proper flowering transition based on mutant phenotypes of two alleles in the Col-0 background and one allele in the Ler background. These alleles were named here xaantal1-1, xaantal1-2, and xaantal1-3 due to their slow-growing root and late-flowering phenotypes. These results were unexpected considering that XAL1 is a sister gene to the AG-related genes that are specific for reproductive tissues, and that most previously characterized MADS-box genes cluster in phylogenetic clades of genes with similar functions and expression patterns during flower, ovule, or carpel development (Rounsley et al., 1995; Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2000a). Nonetheless, previous studies for XAL1 had already suggested that this gene could function in root development due to its high and apparently specific expression in roots (Rounsley et al., 1995; Burgeff et al., 2002). In this study, we have confirmed that XAL1 is indeed expressed in roots, but we show that it is also expressed in aerial tissues prior to the transition to flowering and within floral meristems. In accordance with this pattern of expression, XAL1 is also important for flowering transition.

Functional involvement in more than one tissue or developmental stage might be more common among MADS-box genes than originally believed based on the characterization of the flower-specific MADS-box genes of the A, B, and C functions (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991). Indeed, recent studies have shown that most genes of this family are expressed in several plant tissues, organs, and developmental stages (Kofuji et al., 2003; Parenicová et al., 2003; Schmid et al., 2005). Other studies suggest that MADS-box functional specificity may depend on combinatorial protein-protein interactions (Egea-Cortines et al., 1999; Honma and Goto, 2001; de Folter et al., 2005; Kaufmann et al., 2005; Gregis et al., 2006; Sridhar et al., 2006), rather than on specific spatiotemporal expression patterns for each gene determined at the transcriptional level, as had been suggested before (Savidge et al., 1995; Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2000a).

XAL1 Is an Important Regulator of Cell Proliferation in the Root Meristem

In the root axis, three main zones with contrasting cell proliferation patterns can be distinguished: the RAM, where active cell proliferation takes place from the stem cell niche established around the QC or organizer, and two zones where cells are not proliferating, namely, the elongation and the differentiation zones (Fig. 5; Dolan et al., 1993; Ioio et al., 2007). The data summarized in this article suggest that XAL1 is an important component of the molecular mechanisms controlling cell proliferation in the root. Consequently, the loss-of-function alleles analyzed for this gene show clear spatial alterations of cell behavior along the longitudinal axis of the Arabidopsis root with respect to wild-type plants. Our data suggest that this phenotype is indeed due to the lack of XAL1 because we observed complementation to wild-type root phenotypes using a 35S∷XAL1 construct plasmid transformed into xal1-1 and xal1-2 (data not shown).

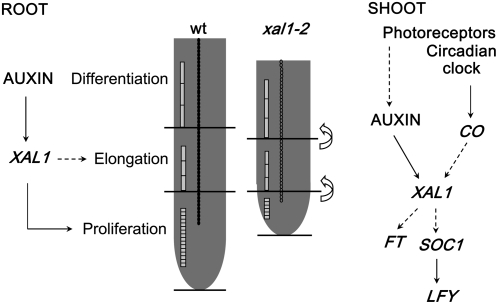

Figure 5.

Model for the role of XAL1 in root and shoot development. The MADS-box gene, XAL1, might mediate auxin participation in the proliferation of the root meristematic cells and the shoot meristem. In the root, XAL1 may also be implicated in cell elongation because the xal1-2 allele has smaller cells than wild type. Auxin may participate in the shoot meristem transition to flowering, mediating light induction of XAL1, which in turn may be an important promoter of downstream regulators in the photoperiod pathway. CO also induces XAL1 expression probably by the classical photoperiod pathway. Solid arrows indicate direct proved regulation and dashed arrows suggest direct/indirect regulation.

Drastically diminished levels of XAL1 expression were correlated with altered cellular organization of the RAM, but only in one-third of the analyzed plants for the three xal1 alleles. In these cases, we observed periclinal divisions of the QC early in root development and also lateral expansion of columella cells. However, all xal1-2 and xal1-3 mutant roots were shorter and had a decreased cell production rate, shorter elongated cells, and a significantly longer cell cycle that correlated with smaller meristems. Therefore, the altered cellular patterns at and around the QC in the affected plants are likely to be a consequence rather than a cause of the diminished cell production rates in the root meristem. In any case, these data suggest that type II plant MADS-box genes could be directly involved in cell-cycle regulation. The punctate pattern of mRNA in situ expression revealed for XAL1 in the root meristematic tissues is also suggestive of a correlation of this gene expression with cell-cycle stage (Burgeff et al., 2002). In addition, XAL1 is also involved in the regulation of cell elongation. However, this effect is apparently masked in the weaker xal1-1 allele (data not shown; Supplemental Table S1; Figs. 2 and 5).

Future studies should further pursue the role of XAL1 in the molecular networks controlling cell proliferation, elongation, and differentiation. Some components of such networks during root development have been characterized. SHORT-ROOT (SHR) and SCARECROW (SCR) are required for QC identity and normal root growth in addition to their role in radial patterning (Scheres et al., 1995; Di Laurenzio et al., 1996; Helariutta et al., 2000; Wysocka-Diller et al., 2000; Nakajima et al., 2001, Sabatini et al., 2003). However, because the SHR/SCR pathway specifies the entire layer surrounding provascular tissues in the root, it is necessary, but not sufficient, to define the exact position of the stem cell niche. Auxin is also an important signal of QC establishment and it regulates the SCR and PLETHORA (PLT) genes, which are also necessary for QC determination (Sablowski, 2004b).

WOX5 is also expressed in the QC and this gene seems to be necessary and sufficient for stem cell identity (Sarkar et al., 2007), probably with a more direct function in stem cell signaling, rather than in specifying QC identity. WOX5 protein or, most probably a downstream factor, might move to stem cells to maintain their identity (Sarkar et al., 2007). In contrast to these genes that have been shown to be important in QC specification and root growth, XAL1 does not show a peak of expression in the QC or stem cell niche, but loss-of-function mutants in this gene also show cellular aberrations in this zone and clear alterations in cell proliferation and root growth. This suggests that this MADS-box gene could be itself a non-cell autonomous signal from more differentiated tissues (columella and vascular tissues) or control another non-cell autonomous downstream component, which could also be important for QC and stem cell behavior and thus cell production rate in the root meristem. It will be important to use genetic approaches to test whether XAL1 functions are independent or not of SCR, SHR, and WOX5 pathways.

Our data demonstrate that the cell production rate is lower in xal1 mutants than in wild type, but premature cell differentiation could also contribute to the smaller meristems of xal1 mutants. Interestingly, recent experiments have shown that cytokinins affect cell differentiation and define the root meristem by antagonizing from the transition zone a non-cell autonomous signal that could be auxin (Ioio et al., 2007). Moreover, down-regulation of cytokinins in the vascular tissue is sufficient to enlarge the root meristem by retarding the transition of cells to the elongation and differentiation zones. These results and xal1 data presented here thus suggest that XAL1 could be regulated and/or mediate cytokinin functions. This should be tested with genetic approaches.

Auxin Up-Regulates XAL1 Specifically in the Root Phloem

Auxin promotes cell elongation, cell-cycle duration, and cell differentiation (Evans et al., 1994; Abel and Theologis, 1996; Himanen et al., 2002; Vanneste et al., 2005). In the root, auxin gradients and movement are sufficient to guide root growth (Sabatini et al., 1999; Galinha et al., 2007; Grieneisen et al., 2007) and affect cell behavior in a dose-dependent fashion (Galinha et al., 2007; Grieneisen et al., 2007). In concordance, auxin response or transport mutants display root-patterning defects and exogenous application of auxin induces ectopic QC and stem cells (Sabatini et al., 1999; Friml et al., 2002). Given that the xal1 mutants analyzed here showed root phenotypes affected in these traits, XAL1 could mediate auxin function. Indeed, our data clearly show that XAL1 is up-regulated after IAA treatment within the root phloem tissues, where it is normally and strongly expressed. The XAL1 promoter also responds positively to other auxin analogs, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2-4D) and naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA; data not shown). Our results thus suggest that there is a phloem-specific factor that responds to auxins and that is required for XAL1 transcriptional up-regulation within these tissues or that XAL1 is itself an auxin-responsive factor. The latter is supported by the presence of several auxin response elements, TGA (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html) and SAUR boxes (http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE; Higo et al., 1999) in the promoter of XAL1.

XAL1 could also be important for phloem cellular patterning. Careful examination of the phloem in the xal1 mutants indicated, however, that XAL1 does not have a key role in the morphogenesis of this tissue on its own because procambial establishment and vascular cell identity in the root are not affected in xal1 mutants in comparison to wild-type plants.

Downstream molecular mechanisms that integrate the cellular effects of auxins and other plant hormones, such as cytokinins, in different spatiotemporal domains during root development are not fully understood. Our data suggest that XAL1 could be one component of such mechanisms. Interestingly, it has recently been suggested that the PLT1 and PLT2 genes, which depend on auxin and auxin response factors for expression, could be the read-out of the root auxin gradient (Galinha et al., 2007). The XAL1 role on cell behavior along the root axis could be related to PLT1 and PLT2 function or it could be part of an independent mechanism. The latter seems to be the case given that XAL1 expression does not overlap with that of the PLT1 and PLT2, which have a gradient-type expression pattern similar to that of auxins with a peak of expression at the QC (Aida et al., 2004). However, other PLETHORA (PLT3 and BBM) genes have strong mRNA expression in the columella stem cell layer and the provascular tissues and could partially overlap with XAL1 expression (Galinha et al., 2007).

XAL1 Is a Promoter of the Floral Transition and Participates in the Photoperiod Pathway

Interestingly, XAL1 is not only important for root development, but is also expressed in aerial tissues and is an important component of the photoperiod pathway of flowering transition, functioning as a flowering promoter in Col-0 Arabidopsis (Reeves and Coupland, 2000; Mouradov et al., 2002). The diminished mRNA levels of the three flowering promoters, SOC, FT, and LFY in the xal1-1 and xal1-2 mutant backgrounds are consistent with this interpretation. FT and SOC act as floral integrators of several pathways, whereas LFY is a flower meristem identity gene that positively responds to FT and SOC1 (Blazquez and Weigel, 2000; Ng and Yanofsky 2000; Moon et al., 2003; Corbesier and Coupland, 2006). None of the other three flowering-transition pathways was affected in these mutant alleles (Table I).

In contrast to several key components of the photoperiod pathway (e.g. CO, GI, CRYPTOCHROME2 [CRY2], and FT; Koornneef et al., 1998a; Simpson and Dean, 2002; Komeda, 2004), the xal1 late-flowering phenotype under LD photoperiods can be recovered to a wild-type phenotype following vernalization (Michaels and Amasino, 2000). In agreement with this, the MADS-box flowering repressor FLC (Michaels and Amasino, 1999; Rouse et al., 2002) is up-regulated in xal1 backgrounds. Therefore, our data suggest that XAL1 could be downstream of CO and GI and upstream of SOC, FT, and LFY. However, complementation of co and gi mutants with XAL1 overexpression constructs, and conversely the overexpression of SOC1 in the xal1 mutant backgrounds, should be pursued in the future to confirm the proposed role of XAL1 in the photoperiod pathway.

There are two possibilities to reconcile the root data for the xal1 mutants with their phenotypes in flowering transition. One possibility is that, given the recently proposed role for auxin response factors in flowering (Ellis et al., 2005; Okushima et al., 2005), XAL1 is a mediator of auxin signaling and participates in the regulation of cell behavior in root and shoot meristems, thus altering their transitions (Fig. 5). The second possibility is that XAL1 has different roles in root and aerial meristems as part of different complexes with other MADS-box proteins, or being a downstream component of different signaling mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) wild-type, xal1-1, and xal1-2 plants, co-1, and the DR5(7X)∷GUS auxin reporter line (Ulmasov et al., 1997) are in the Col-0 genetic background, whereas xal1-3 is in the Ler ecotype. Seedlings were grown on vertical plates with 0.2× Murashige and Skoog salts and 1% Suc. Plants were grown in climate chambers at 22°C. The photoperiods (110 μE m−2 s−1) were established at 16 h of light followed by 8 h of dark for LD photoperiods and 8 h of light followed by 16 h of dark for SD photoperiods.

Identification of Mutant Alleles

The xal1-1 allele was identified by screening for En-1 insertions among a collection of Arabidopsis plants carrying approximately 50,000 independent insertions of the autonomous maize (Zea mays) transposable element (Baumann et al., 1998). The collection was screened in pools using the En-1 transposon primer En205 (5′-AGAAGCACGACGGCTGTAGAATAGGA-3′) and the internal XAL1 primers OEAB141 (5′-GGTCGTGGTTCTTCTTCTGCT-3′) and OEAB143 (5′-CATTTCATCTTCACACCAAC-3′). The xal1-2 homozygous line was isolated from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre T2 generation stock N429367 (former GK_306H03 from the GABI-Kat collection). Plants 100% resistant to sulfadiazine were further confirmed by PCR using the following primers: GK T-DNA (5′-CCCATTTGGACGTGAATGTAGACAC-3′) and specific XAL1 primers NASC12-LP (5′-ACCCAAACGTCAAATCATCAG-3′) and NASC12-RP (5′-CTTCATTCCGAAACACAATGC-3′). The xal1-3 allele was identified by screening on a two-component system mutagenized collection based on the maize mobile/transposon Spm as described by Speulman et al. (1999).

Microscopy

Plant material for light microscopy was prepared as previously described by Malamy and Benfey (1997). Roots were visualized under an Olympus BX60 microscope. Confocal images were acquired on an inverted Zeiss LSM 510 Meta microscope with a 63× water immersion objective after root was stained with 10 μg mL−1 propidium iodide.

Quantitative Analysis of Cellular Parameters of Root Growth

Length of the meristem was determined for the cortex cells as the distance between the root-body/root-cap junction to the level where cells started to elongate, according to Casamitjana-Martinez et al. (2003). The length of the elongation zone was taken as the distance between the proximal meristem border and the location of the most distal root-hair bulge. The average cycle time for cortical cell production in plants growing between 7 to 8 d was done, using the rate of cell production (Ivanov and Dubrovsky, 1997). The duration of the cell cycle (T) was calculated for each individual root using the following equation: T = (ln2 Nm le) V−1, where Nm is the number of meristematic cells in one file of the cortex, le are the fully elongated cell length calculated as the average length of 10 fully elongated cortex cells in the same root, and V is the root growth rate calculated as μm h−1. Nm in 7- and 8-d-old roots (a period during which the rate of the root growth was estimated) was similar in both the wild-type and mutant plants, which enabled us to consider root growth to be at steady state and apply the method described above. The rate of cell production was estimated as V(le)−1 (Baskin, 2000). Statistical Student's t test or the Tukey-Kramer test (depending on the sample size) was analyzed by the JMP program, version 5.1.1.

Reporter Lines

For XAL1∷GUS and XAL1∷GFP constructs, a 2.8-kb or 6.8-kb promoter and the 5′ untranslated region were obtained from a Lambda genomic DNA library and cloned into pGEM-T vector (Promega) as a SalI-XbaI fragment. This fragment was subcloned into the pBI101 binary vector and the mGFP5-ER to generate the XAL1∷GUS and the XAL1∷GFP lines, respectively. Arabidopsis Col-0 ecotype plants were transformed using the floral-dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). The transgenic lines were selected based on their kanamycin resistance and the expression analysis was carried out on T3 homozygous lines.

Hormone Treatments and GUS Reaction

XAL1∷GUS and DR5(7X)∷GUS seedlings were grown for 7 d in hormone-free medium plates and then transferred to growth medium supplemented with 2 μm of the following hormones: IAA, NAA, and 2,4-D for 24 h. After hormone treatment, DR5(7X)∷GUS and XAL1∷GUS seedlings were subjected to GUS staining during 40 min at room temperature and 5 h at 37°C, respectively. Stained plants were cleared and visualized under a microscope.

In Situ Hybridization and Histochemical Analysis

Inflorescence and bud flowers from wild-type and xal1-1 were subjected to in situ hybridization (Drews et al., 1991). Digoxigenin-labeled XAL1 probes were synthesized using a 113-bp cDNA template amplified with 5′-ATAAAGCCTGTGGAACTTC-3′ and 5′-TAAGTACACACCACACTTG-3′ primers, cloned in pGEM-T Easy vector.

For flower histochemical analysis, samples were processed according to the protocol described in Blazquez et al. (1998). For histological root analysis, GUS-stained samples were dehydrated through ethanol/histoclear series until they were substituted with 100% histoclear (National Diagnostics). Finally, material was embedded in Paraplast+ (Oxford Labware). Transversal sections of 8-μm-thick GUS-positive root samples were counterstained with 0.1% ruthenium red (Scheres et al., 1994).

Expression Analysis by Northern Blot and RT-PCR

Wild-type and mutant seedlings were grown for 14 d on Murashige and Skoog plates under LD conditions. Total RNA was isolated from root or shoot tissue separately using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed from two different experiments, each time with duplicates. PCR amplification conditions and sequence primers are described in Supplemental Table S2. RNA-blot hybridization was performed with 10 μg of total RNA per lane with a gene-specific 3′ probe, amplified with the following primers: 5′-GGATGTTATGCTTCAAGAAATTC-3′ and 5′-CCAAATAATCCATAAATTCAAAAC-3′.

Flowering-Time Measurements

The bolting time was measured as the days after seed sowing required for the stem to develop 1 cm long under either photoperiod condition. Total number of rosette leaves included fully expanded and not fully expanded leaves. For experiments involving vernalization, seeds were plated on Murashige and Skoog medium and kept under dark for 6 weeks at 4°C and then transferred to soil and grown under LD conditions until flowering. To examine GA3 effects on flowering time, 100 μm GA3 solution was sprayed once a week starting 30 d after sowing and continued until bolting. Data expressed as mean ± se were analyzed by the JMP program, version 5.1.1.

Phylogenetic Analysis

We performed a Bayesian reconstruction of the phylogenetic relationships among selected type II Arabidopsis MADS-box genes using the whole cDNAs. Bayesian methods with MrBayes according to Huelsenbeck and Ronquist (2001) were used with a Markov chain Monte Carlo exploration of the tree likelihood surface. Four independent Markov chains (three heated) were used according to the Metropolis coupled scheme. The codon substitution model used was that of Goldman and Yang (1994). Four independent runs of 2,500,000 generations each were performed, and every 100th tree was saved. After checking for Markov chain convergence, we discarded the first 15,000 trees and used the remaining trees to calculate Bayesian posterior probabilities of the clades. Results from every independent run were similar.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession number NC_003070.5.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. XAL1 expression in co-1 background.

Supplemental Table S1. Quantitative analysis of root development in xal1-2 and xal1-3 strong alleles and their respective control wild-type plants.

Supplemental Table S2. List of the oligonucleotides used for RT-PCR experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Marty Yanofsky for his guidance, comments, and support. In his laboratory, Gary Ditta helped with the initial molecular characterization of the xal1-1 insertion line and Steve Rounsley constructed XAL1∷GUS plasmids and obtained transgenics. We also thank L. Martínez-Castilla, D. Romo, S. Napsucialy-Mendivil, and A. Saralegui for their technical support. V. Willemsen, I. Blilou, and D. Welch from B. Scheres' laboratory guided root techniques. Jane Murfett is acknowledged for the donation of the DR5(7X)∷GUS line and Yu Hao for the co-1 allele. Stewart Gillmor helped in editing the last version of the paper.

This work was supported by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT), México (grant nos. CO1.41848/A–1, CO1.0538/A–1, and CO1.0435.B–1); Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA)-Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM; grant nos. IN230002 and IX207104); and the University of California-MEXUS ECO IE 271 to E.R.A.-B. R.T.-L. was a recipient of CONACYT and DGAPA-PAPIIT-UNAM fellowships (no. IX225304). J.G.D. was supported by DGAPA-PAPIIT-UNAM (grant nos. IN210202 and IN225906) and CONACYT (grant no. 49267).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Elena R. Alvarez-Buylla (eabuylla@gmail.com).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Abel S, Theologis A (1996) Early genes and auxin action. Plant Physiol 111 9–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aida M, Beis D, Heidstra R, Willemsen V, Blilou I, Galinha C, Nussaume L, Noh YS, Amasino R, Scheres B (2004) The PLETHORA genes mediate patterning of the Arabidopsis root stem cell niche. Cell 119 109–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla ER, Liljegren SJ, Pelaz S, Gold SE, Burgeff C, Ditta GS, Vergara-Silva F, Yanofsky MF (2000. a) MADS-box gene evolution beyond flowers: expression in pollen, endosperm, guard cells, roots and trichomes. Plant J 24 457–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla ER, Pelaz S, Liljegren SJ, Gold S, Burgeff C, Ditta GS, Ribas de Pouplana L, Martinez-Castilla L, Yanofsky MF (2000. b) An ancestral MADS-box gene duplication occurred before the divergence of plants and animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 10 5328–5333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin TI (2000) On the constancy of cell division rate in the root meristem. Plant Mol Biol 43 545–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum SF, Eshed Y, Bowman JL (2001) The Arabidopsis nectary is an ABC-independent floral structure. Development 126 4657–4667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum ST, Dubrovsky JG, Rost TL (2002) Apical organization and maturation of the cortex and vascular cylinder in Arabidopsis thaliana (Brassicaceae) roots. Am J Bot 89 908–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann E, Lewald J, Saedler H, Schultz B, Wisman E (1998) Successful PCR-based reverse genetic screen using an En-1 mutagenised Arabidopsis thaliana population generated via single-seed descent. Theor Appl Genet 97 729–734 [Google Scholar]

- Benfey PN, Scheres B (2000) Root development. Curr Biol 10 R813–R815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazquez MA, Green R, Nilsson O, Sussman MR, Weigel D (1998) Gibberellins promote flowering of Arabidopsis by activating the LEAFY promoter. Plant Cell 10 791–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazquez MA, Weigel D (2000) Integration of floral inductive signals in Arabidopsis. Nature 404 889–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss PK, Bastow RM, Mylne JS, Dean C (2004) Multiple pathways in the decision to flower: enabling, promoting, and resetting. Plant Cell (Suppl) 16 S18–S31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman JL, Alvarez J, Weigel D, Meyerowitz EM, Smyth DR (1993) Control of flower development of Arabidopsis thaliana by APETALA1 and interacting genes. Development 119 721–743 [Google Scholar]

- Bowman JL, Smyth DR, Meyerowitz EM (1991) Genetic interactions among floral homeotic genes of Arabidopsis. Development 112 1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgeff C, Liljegren SJ, Tapia-Lopez R, Yanofsky MF, Alvarez-Buylla ER (2002) MADS-box gene expression in lateral primordia, meristems and differentiated tissues of Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Planta 214 365–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caro E, Castellano MM, Gutierrez C (2007) A chromatin link that couples cell division to root epidermis patterning in Arabidopsis. Nature 447 213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casamitjana-Martinez E, Hofhuis HF, Xu J, Liu CM, Heidstra R, Scheres B (2003) Root-specific CLE19 over-expression and the sol1/2 suppressors implicate a CLC-like pathway in the control of Arabidopsis root meristem maintenance. Curr Biol 13 1435–1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman K, Groot EP, Nichol SA, Rost TL (2003) Primary root growth and the pattern of root apical meristem organization are coupled. J Plant Growth Regul 21 287–295 [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen ES, Meyerowitz EM (1991) The war of the whorls: genetic interactions controlling flower development. Nature 353 31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L, Coupland G (2006) The quest for florigen of recent progress. J Exp Biol 57 3395–3403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Folter S, Immink RGH, Kleffer M, Parenicova L, Henz SR, Weigel D, Bussher M, Kooiker M, Colombo L, Kater MM, et al (2005) Comprehensive interaction map of the Arabidopsis MADS box transcription factor. Plant Cell 17 1424–1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Laurenzio L, Wysocka-Diller J, Malamy JE, Pysh L, Helariutta Y, Freshour G, Hahn MG, Feldmann KA, Benfey PN (1996) The SCARECROW gene regulates an asymmetric cell division that is essential for generating the radial organization of the Arabidopsis root. Cell 86 423–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan L, Janmaat K, Willemsen V, Linstead P, Poethig S, Roberts K, Scheres B (1993) Cellular organisation of the Arabidopsis thaliana root. Development 119 71–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews GN, Bowman JL, Meyerowitz EM (1991) Negative regulation of the Arabidopsis homeotic gene AGAMOUS by the APETALA2 product. Cell 65 991–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egea-Cortines M, Saedler H, Sommer H (1999) Ternary complex formation between the MADS-box proteins SQUAMOSA, DEFICIENS and GLOBOSA is involved in the control of floral architecture in Antirrhinum majus. EMBO J 18 5370–5379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis CM, Nagpal P, Young JC, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ, Reed JW (2005) AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR1 and AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR2 regulate senescence and floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 132 4563–4574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Soto C, Padilla-Longoria P, Alvarez-Buylla ER (2004) A regulatory network model for cell-fate determination during Arabidopsis thaliana flower development that is robust and recovers experimental gene expression profiles. Plant Cell 16 2923–2939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans ML, Ishikawa H, Estelle MA (1994) Responses of Arabidopsis roots to auxin studied with high temporal resolution—comparison of wild-type and auxin-response mutants. Planta 194 215–222 [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandiz C, Liljegren SL, Yanofsky MF (2000) negative regulation of SHATTERPROOF genes by FRUITFULL during Arabidopsis fruit development. Science 289 436–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J, Benková E, Blilou I, Wisniewska J, Hamann T, Ljung K, Woody S, Sandberg G, Scheres B, Jürgens G, et al (2002) AtPIN4 mediates sink-driven auxin gradients and root patterning in Arabidopsis. Cell 108 661–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinha C, Hofhuis H, Luijten M, Willemsen V, Blilou I, Heidstra R, Scheres B (2007) PLETHORA proteins as dose-dependent master regulators of Arabidopsis root development. Nature 449 1053–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman N, Yang Z (1994) A codon-based model of nucleotide substitution for protein-coding DNA sequences. Mol Biol Evol 11 725–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregis V, Sessa A, Colombo L, Kater MM (2006) AGL24, SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE, and APETALA1 redundantly control AGAMOUS during early stages of flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18 1373–1382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieneisen VA, Xu J, Marée AFM, Hogeweg P, Scheres B (2007) Auxin transport is sufficient to generate a maximum and gradient guiding root growth. Nature 449 1008–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Ferrandiz C, Yanofsky MF, Martienssen R (1998) The FRUITFULL MADS-box genes mediates cell differentiation during Arabidopsis fruit development. Development 125 1509–1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helariutta Y, Fukaki H, Wysocka-Diller J, Nakajima K, Jung J, Sena G, Hauser MT, Benfey PN (2000) The SHORT-ROOT gene controls radial patterning of the Arabidopsis root through radial signaling. Cell 101 555–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higo K, Ugawa Y, Iwamoto M, Korenaga T (1999) Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Res 27 297–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himanen K, Boucheron E, Vanneste S, de Almeida Engler J, Inzé D, Beeckman T (2002) Auxin-mediated cell cycle activation during early lateral root initiation. Plant Cell 14 2339–2351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma T, Goto K (2001) Complexes of MADS-box proteins are sufficient to convert leaves into floral organs. Nature 409 525–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F (2001) Mr Bayes: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics 17 754–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi T, Kay SA (2006) Photoperiodic control of flowering: not only by coincidence. Trends Plant Sci 11 550–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioio RD, Linhares FS, Scacchi E, Casamitjana-Martinez E, Heidstra R, Costantino P, Sabatini S (2007) Cytokinins determine Arabidopsis root-meristem size by controlling cell differentiation. Curr Biol 17 678–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov VB, Dubrovsky JG (1997) Estimation of the cell-cycle duration in the root apical meristem: a model of linkage between cell-cycle duration, rate of cell production, and rate root growth. Int J Plant Sci 158 757–763 [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann K, Melzer R, Theißen G (2005) MICK-type MADS-domain proteins: structural modularity, protein interactions and network evolution in land plants. Gene 347 183–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofuji R, Sumikawa N, Yamasaki M, Kondo K, Ueda K, Ito M, Hasebe M (2003) Evolution and divergence of the MADS-box gene family based on genome-wide expression analyses. Mol Biol Evol 20 1963–1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komeda Y (2004) Genetic regulation of time to flower in Arabidopsis thaliana. Annu Rev Plant Biol 55 521–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, Alonso-Blanco C, Blankestijn-de VH, Hanhart CJ, Peeters AJM (1998. a) Genetic interactions among late flowering mutants of Arabidopsis. Genetics 148 549–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, Alonso-Blanco C, Peeters AJM, Soppe W (1998. b) Genetic control of flowering time in Arabidopsis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 49 345–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PA, Morata G (1994) Homeobox genes: their function in Drosophila segmentation and pattern formation. Cell 78 181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro JB, Bailey PJ, Lassar AB (2002) Cyclin D-cdk4 activity modulates the subnuclear localization and interaction of MEF2 with SRC-family coactivators during skeletal muscle differentiation. Genes Dev 16 1792–1805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljegren SJ, Ditta GS, Eshed Y, Savidge B, Bowman JL, Yanofsky MF (2000) SHATERPROOF MADS-box genes control seed dispersal in Arabidopsis. Nature 404 766–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamy JE, Benfey PN (1997) Organization and cell differentiation in lateral roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 124 33–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel MA, Gustafson-Brown C, Savidge B, Yanofsky MF (1992) Molecular characterization of the Arabidopsis floral homeotic gene APETALA1. Nature 360 273–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Castilla LP, Alvarez-Buylla ER (2003) Adaptive evolution in the Arabidopsis MADS-box gene family inferred from its complete resolved phylogeny. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100 13407–13412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messenguy F, Dubois E (2003) Role of MADS box proteins and their cofactors in combinatorial control of gene expression and cell development. Gene 316 1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels S, Amasino R (1999) FLOWERING LOCUS C encodes a novel MADS-domain protein that acts as a repressor of flowering. Plant Cell 11 949–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels SD, Amasino RM (2000) Memories of winter: vernalization and the competence to flower. Plant Cell Environ 23 1145–1153 [Google Scholar]

- Moon J, Suh SS, Lee H, Choi KR, Hong CB, Paek NC, Kim SG, Lee I (2003) The SOC1 MADS-box gene integrates vernalization and gibberellin signals for flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant J 35 613–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouradov A, Cremer F, Coupland G (2002) Control of flowering time: Interacting pathways as a basis for diversity. Plant Cell (Suppl) 14 S111–S130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Sena G, Nawy T, Benfey PN (2001) Intercellular movement of the putative transcription factor SHR in root patterning. Nature 413 307–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesi N, Debeaujon I, Jond C, Stewart AJ, Jenkins GI, Caboche M, Lepiniec L (2002) TRANSPARENT TESTA16 locus encodes the ARABIDOPSIS B-SISTER MADS domain protein and is required for proper development and pigmentation of the seed coat. Plant Cell 14 2463–2479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Yanofsky MF (2000) Three ways to learn the ABCs. Curr Opin Plant Biol 3 47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okushima Y, Mitina I, Quach HL, Theologis A (2005) AUXIN REPONSE FACTOR 2 (ARF2): a pleiotropic developmental regulator. Plant J 43 29–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parenicová L, de Folter S, Kieffer M, Horner DS, Favalli C, Busscher J, Cook HE, Ingram RM, Kater M, Davies B, et al (2003) Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the complete MADS-box transcription factor family in Arabidopsis: new openings to the MADS world. Plant Cell 15 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelaz S, Ditta G, Baumann E, Wisman E, Yanofsky MF (2000) B and C floral identity functions require SEPALLATA MADS-box genes. Nature 405 200–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinyopich A, Ditta GS, Savidge B, Liljegren SJ, Baumann E, Wisman E, Yanofsky MF (2003) Assessing the redundancy of MADS-box genes during carpel and ovule development. Nature 424 85–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putterill J, Laurie R, Macknight R (2004) It's time to flower: the genetic control of flowering time. Bioessays 26 363–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves PH, Coupland G (2000) Response of plant development to environment: control of flowering by day. Curr Opin Plant Biol 3 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riechmann JL, Meyerowitz EM (1997) MADS domain proteins in plant development. Biol Chem 378 1079–1101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijpkema AS, Gerats T, Vandenbussche M (2007) Evolutionary complexity of MADS complexes. Curr Opin Plant Biol 10 32–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsley SR, Ditta G, Yanofsky MF (1995) Diverse roles for MADS-box genes in Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 7 1259–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse DT, Sheldon CC, Bagnall DJ, Peacock J, Dennis ES (2002) FLC, a repressor of flowering, is regulated by genes in different inductive pathways. Plant J 29 183–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini S, Beis D, Wolkenfelt H, Murfett J, Guilfoyle T, Malamy J, Benfey P, Leyser O, Bechtold N, Weisbeek P, et al (1999) An auxin-dependent distal organizer of pattern and polarity in the Arabidopsis root. Cell 24 463–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini S, Heidstra R, Wildwater M, Scheres B (2003) SCARECROW is involved in positioning the stem cell niche in the Arabidopsis root meristem. Genes Dev 17 354–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sablowski R (2004. a) Plant and animal stem cells: conceptually similar, molecularly distinct? Trends Cell Biol 14 605–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sablowski R (2004. b) Root development: the embryo within? Curr Biol 14 R1054–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samach A, Onuchi H, Gold SE, Ditta GS, Schwarz-Sommer Z, Yanofsky MF, Coupland G (2000) Distinct roles of CONSTANS target genes in reproductive development of Arabidopsis. Science 288 1613–1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar AK, Luijten M, Miyashima S, Lenhard M, Hashimoto T, Nakajima K, Scheres B, Heidstra R, Laux T (2007) Conserved factors regulate signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana shoot and root stem cell organizers. Nature 446 811–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savidge B, Rounsley SD, Yanosfky MF (1995) Temporal relationship between the transcription of the two Arabidopsis MADS-box genes and the floral organ identity genes. Plant Cell 7 721–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres B, Di Laurenzio L, Willemsen V, Hauser MT, Janmaat K, Weisbeek P, Benfey PN (1995) Mutations affecting the radial organisation of the Arabidopsis root display specific defects throughout the embryonic axis. Development 121 53–62 [Google Scholar]

- Scheres B, Wolkenfelt H, Willemsen V, Terlou M, Lawson E, Dean C, Weisbeek P (1994) Embryonic origin of the Arabidopsis primary root and root meristem initials. Development 120 2475–2487 [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Davison TS, Heinz SR, Pape UJ, Demar M, Vingron M, Scholkopf B, Weigel D, Lohmann JU (2005) A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat Genet 37 501–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle I, He Y, Turck F, Vincent C, Fornara F, Krober S, Amasino S, Amasino RA, Coupland G (2006) The transcription factor FLC confers a flowering response to vernalization by repressing meristem competence and systemic signaling in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 20 898–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GG, Dean C (2002) Arabidopsis, the Rosetta stone of flowering time? Science 296 285–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speulman E, Metz PLJ, van Arkel G, Hekkert BTL, Stiekeman WJ, Pereyra A (1999) A two-component enhancer-inhibitor transposon mutagenesis system for functional analysis of the Arabidopsis genome. Plant Cell 11 1853–1866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar VV, Surendrarao A, Liu Z (2006) APETALA1 and SEPALLATA3 interact with SEUSS to mediate transcription repression during flower development. Development 133 3159–3166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T, Murfett J, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ (1997) Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. Plant Cell 9 1963–1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanneste S, De Rybel B, Beemster GT, Ljung K, De Smet I, Van Isterdael G, Naudts M, Iida R, Gruissem W, Tasaka M, et al (2005) Cell cycle progression in the pericycle is not sufficient for SOLITARY ROOT/IAA14-mediated lateral root initiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 17 3035–3050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Dassow G, Odell GM (2002) Design and constraints of the Drosophila segment polarity module: robust spatial patterning emerges from intertwined cell state switches. J Exp Zool 294 179–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildwater M, Campilho A, Perez-Perez JM, Heidstra R, Blilou I, Korthout H, Chatterjee J, Mariconti L, Gruissem W, Scheres B (2005) The RETINOBLASTOMA-RELATED gene regulates stem cell maintenance in Arabidopsis roots. Cell 123 1337–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocka-Diller JW, Helariutta Y, Fukaki H, Malamy JE, Benfey PN (2000) Molecular analysis of SCARECROW function reveals a radial patterning mechanism common to root and shoot. Development 127 595–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanofsky MF, Ma H, Bowman JL, Drews GN, Feldman KN, Meyerowitz EM (1990) The protein encoded by the Arabidopsis homeotic gene AGAMOUS resembles transcription factors. Nature 346 35–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.