Abstract

Like many crucifer-specialist herbivores, Pieris rapae uses the presence of glucosinolates as a signal for oviposition and larval feeding. Arabidopsis thaliana glucosinolate-related mutants provide a unique resource for studying the in vivo role of these compounds in affecting P. rapae oviposition. Low indole glucosinolate cyp79B2 cyp79B3 mutants received fewer eggs than wild type, confirming prior research showing that indole glucosinolates are an important oviposition cue. Transgenic plants overexpressing epithiospecifier protein, which shifts glucosinolate breakdown toward nitrile formation, are less attractive to ovipositing P. rapae females. Exogenous application of indol-3-ylmethylglucosinolate breakdown products to cyp79B2 cyp79B3 mutants showed that oviposition was increased by indole-3-carbinol and decreased by indole-3-acetonitrile (IAN). P. rapae larvae tolerate a cruciferous diet by using a gut enzyme to redirect glucosinolate breakdown toward less toxic nitriles, including IAN, rather than isothiocyanates. The presence of IAN in larval regurgitant contributes to reduced oviposition by adult females on larvae-infested plants. Therefore, production of nitriles via epithiospecifier protein in cruciferous plants, which makes the plants more sensitive to generalist herbivores, may be a counter-adaptive mechanism for reducing oviposition by P. rapae and perhaps other crucifer-specialist insects.

Crucifers and other plants in the order Caparales have an effective chemical defense that requires the hydrolysis of glucosinolates by myrosinase (β-thioglucoside glucohydrolase [TGG]; EC 3.2.1.147), leading to the formation of breakdown products that deter herbivory (for review, see Grubb and Abel, 2006; Halkier and Gershenzon, 2006). In contrast to generalist herbivores, which tend to avoid glucosinolates, Pieris rapae and other crucifer-feeding specialists recognize glucosinolates and their breakdown products as stimulants for feeding and oviposition. 2-Propenylglucosinolate, 2-phenylethylglucosinolate, and other glucosinolates applied to Vigna sinensis leaves stimulated feeding by P. rapae larvae (Renwick and Lopez, 1999; Miles et al., 2005). Host plant choice experiments with purified glucosinolates sprayed onto Phaseolus vulgaris showed that P. rapae oviposition is stimulated primarily by indole and aromatic glucosinolates (Huang and Renwick, 1993, 1994). Although intact indol-3-ylmethylglucosinolate (I3M) was the strongest P. rapae oviposition stimulant found in cabbage (Brassica oleracea) surface washes (Renwick et al., 1992; Van Loon et al., 1992), the chemical instability of indole glucosinolates suggests that the P. rapae were exposed to not only intact I3M but also breakdown products in these assays. Related experiments also showed that indole and aromatic glucosinolates elicit stronger responses than aliphatic glucosinolates from P. rapae tarsal chemoreceptor cells, which are used to test leaf surfaces prior to oviposition (Städler et al., 1995).

Glucosinolates are produced constitutively in cruciferous plants, but their degradation is strictly regulated by the spatial separation of glucosinolates and myrosinase in the plant. Upon tissue rupture, myrosinase enzymes cleave glucosinolates, producing unstable thiohydroxamate-O-sulfonates, which can be broken down further to produce a wide variety of insect-deterrent compounds. The epithiospecifier protein (ESP) interacts with myrosinase and directs glucosinolate breakdown toward the formation of nitriles and epithionitriles at the expense of the generally more toxic isothiocyanates (Lambrix et al., 2001; Fig. 1). In the case of I3M, the predominant indole glucosinolate in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Petersen et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2003), ESP promotes the formation of indole-3-acetonitrile (IAN) instead of indolylmethylisothiocyanate as the primary breakdown product (Miao and Zentgraf, 2007; Burow et al., 2008). Indolylmethylisothiocyanate, when it is produced in Arabidopsis and other crucifers, reacts rapidly to form indole-3-carbinol (I3C), a relatively stable I3M breakdown product (Agerbirk et al., 1998).

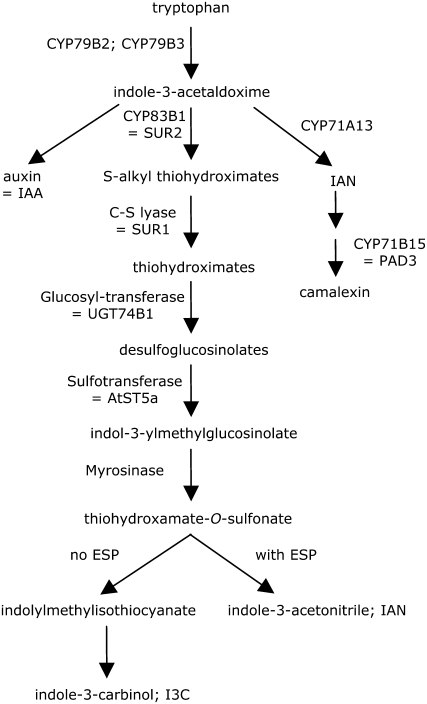

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis and breakdown of I3M. Indole glucosinolates are derived from Trp, with CYP79B2 (At4g39950), CYP79B3 (At2g22330), CYP83B1 (At4g31500), C-S lyase (At2g20610), UGT74B1 (At1g24100), and AtST5a (At5g74100) being key enzymes in the biosynthetic pathway. Indole glucosinolate hydrolysis depends on myrosinases TGG1 (At5g26000) and TGG2 (At5g25980), which have redundant function. ESP (At1g54040) directs the breakdown of I3M toward IAN rather than I3C.

Natural variation in Arabidopsis sensitivity to feeding by the generalist Trichoplusia ni is strongly influenced by the presence or absence of ESP in the land races Columbia-0 (Col-0) and Landsberg erecta (Ler; Jander et al., 2001; Lambrix et al., 2001). Similarly, transgenic overproduction of ESP in Arabidopsis increased growth of Spodoptera littoralis, another generalist lepidopteran herbivore (Burow et al., 2006b). As was demonstrated by addition of microencapsulated isothiocyanates to artificial diets, these compounds are also toxic to the crucifer-specialist P. rapae (Agrawal and Kurashige, 2003). However, when P. rapae larvae feed from intact plants, a nitrile specifier protein in the insect gut, which functions in an analogous manner to the plant-derived ESP, directs glucosinolate breakdown toward less toxic nitriles that are excreted in the frass (Wittstock et al., 2004).

By avoiding oviposition on plants that are previously infested, adult female Lepidoptera can help to ensure that sufficient food will be available for their offspring. Both P. rapae and the closely related Pieris brassicae oviposit less readily on plants with feeding larvae (Rothschild and Schoonhoven, 1977), suggesting biochemical changes in the host plants or that the larvae, their frass, or regurgitant contain oviposition deterrents. Similarly, both species show reduced oviposition on plants that already carry conspecific eggs (Schoonhoven et al., 2005). Oviposition by P. brassicae and to a lesser extent P. rapae triggers defense-related gene expression changes in Arabidopsis (Little et al., 2007). Resulting metabolic changes in the plants or perhaps direct visual and chemical cues from the eggs themselves could provide signals that deter subsequent oviposition (Blaakmeer et al., 1994).

P. rapae commonly infest weedy crucifers such as cabbage and Arabidopsis (formerly Arabis) lyrata (Mitchell-Olds, 2001; Agrawal and Kurashige, 2003) and have also been observed on both planted (Harvey et al., 2007) and natural (Geervliet, 1997) Arabidopsis populations. Although a winter annual growth habit may allow Arabidopsis to avoid herbivory by insects that require warmer temperatures, not all Arabidopsis exhibit this life cycle (Pigliucci, 2002). Particularly in more southern regions, there would be considerable overlap between Arabidopsis and Lepidoptera such as P. rapae, which overwinter as pupae and emerge as soon as it is warm enough for them to fly. For instance, a larva of an unknown lepidopteran species was observed feeding on a natural stand of Arabidopsis in North Carolina (Mauricio, 1998).

Although there is evidence that ovipositing P. rapae females are stimulated by indole glucosinolates (Huang and Renwick, 1993, 1994), this has not been proven through analysis of isogenic lines with and without indole glucosinolates. Furthermore, although the insects are perhaps more likely to be exposed to glucosinolate breakdown products rather than intact glucosinolates, evidence of an in vivo role for indole glucosinolate breakdown products in the oviposition response is still lacking. Therefore, we have made use of Arabidopsis mutants with blocked indole glucosinolate biosynthesis (cyp79B2 cyp79B3; Fig. 1), reduced myrosinase activity (tgg1 tgg2), and ESP overproduction (35S:ESP) to assess the role of indole glucosinolates and their breakdown products in P. rapae oviposition. Surprisingly, the two primary indole-glucosinolate breakdown products showed contrasting effects on P. rapae oviposition, with I3C acting as a stimulant and IAN acting as a deterrent. Moreover, application of IAN-containing larval regurgitant reduced host plant attractiveness for ovipositing P. rapae. This suggests that ESP-expressing plants that produce nitriles may appear chemically similar to those infested by P. rapae and thereby deter oviposition by this specialist herbivore.

RESULTS

Oviposition by P. rapae Is Dependent on Indole Glucosinolates

Three-week-old wild-type and mutant Arabidopsis plants were used in a 24-h choice test to investigate the in vivo role of indole glucosinolates in the oviposition response of P. rapae. Female P. rapae deposit eggs individually on the leaf surface (Fig. 2A), allowing relative plant attractiveness to be assessed by counting eggs. Compared to wild-type plants, the low indole glucosinolate mutant (cyp79B2 cyp79B3) received significantly fewer eggs (Fig. 3A), indicating an in vivo role for indole glucosinolates in triggering oviposition by female P. rapae. Absence of camalexin, the major Arabidopsis phytoalexin, in cyp79B2 cyp79B3 mutants (Glazebrook and Ausubel, 1994; Zhou et al., 1999; Schuhegger et al., 2006) could also influence P. rapae oviposition. However, no significant difference was observed when comparing the number of eggs deposited on wild-type Col-0 and the phytoalexin deficient3 (pad3-1) mutant plants over 24 h (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, oviposition on atr1D atr2D mutants, which have elevated indole glucosinolate content, was not significantly different from Col-0 plants (Fig. 3C), suggesting that wild-type levels of indole glucosinolates are sufficient as an oviposition cue. This is consistent with a prior report that, beyond an optimal concentration, addition of more glucosinolates either did not promote P. rapae oviposition or actually decreased it (Huang and Renwick, 1993).

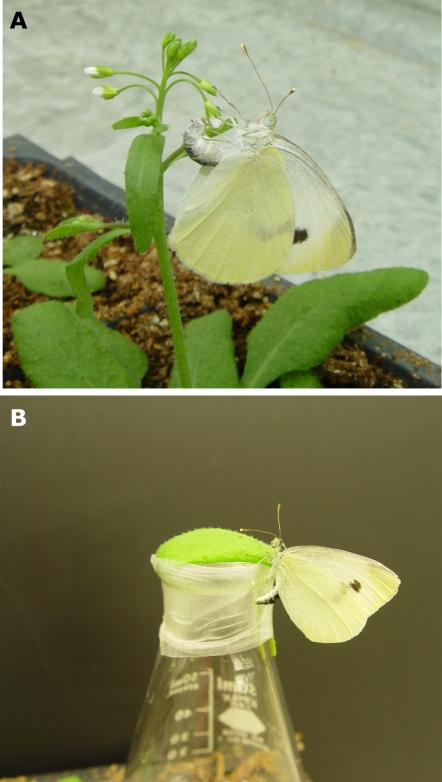

Figure 2.

Oviposition experiments with female P. rapae. Experiments involved oviposition by a single adult female P. rapae on whole plants (A, paired choice test) or on leaves mounted on top of an Erlenmeyer flask (B, nonpaired choice test). Upon landing, P. rapae females test the leaf surface by drumming their legs. The tarsi contain chemoreceptors for oviposition cues, and host acceptance requires integration of positive and negative stimuli.

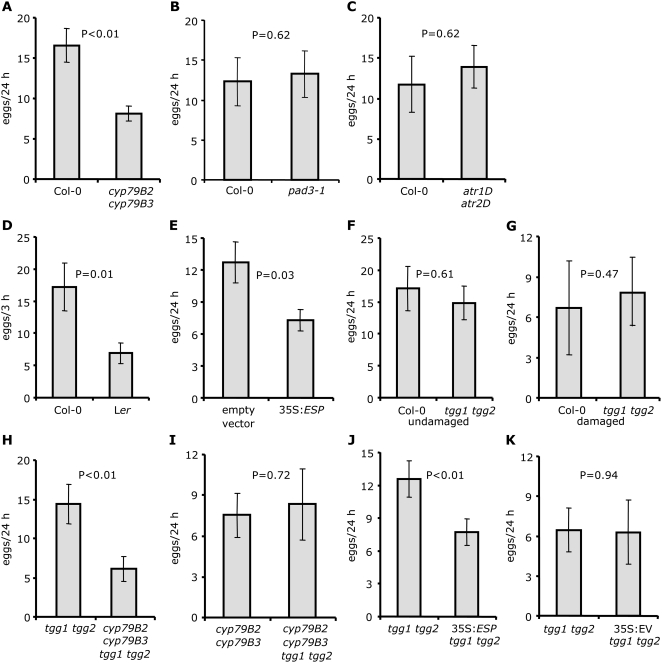

Figure 3.

P. rapae oviposition on wild-type Arabidopsis and mutants with altered glucosinolate profiles. A, Oviposition by a single adult P. rapae female over 24 h in choice tests comparing Col-0 and mutant plants with low indole glucosinolate levels (cyp79B2 cyp79B3; n = 14). B, Oviposition choice test comparing Col-0 and camalexin-deficient mutant pad3-1 plants (n = 15). C, Oviposition choice test comparing Col-0 and mutant plants with high indole glucosinolate levels (atr1D atr2D; n = 11). D, Oviposition choice test (3 h) comparing Col-0 and Ler (n = 30). E, Oviposition choice test comparing ESP-overexpressing and Col-0 control plants (n = 22). F and G, Oviposition choice test comparing Col-0 and mutant plants lacking myrosinase activity (tgg1 tgg2; n = 13) and mechanically damaged Col-0 and tgg1 tgg2 mutant plants (n = 19). H and I, Oviposition choice tests comparing the quadruple mutant cyp79B2 cyp79B3 tgg1 tgg2 with tgg1 tgg2 (n = 20) or cyp79B2 cyp79B3 (n = 15). J and K, Oviposition choice test comparing 35S:ESP tgg1 tgg2 plants (n = 25) and EV control tgg1 tgg2 plants (n = 7) with tgg1 tgg2 plants. Mean ± se, all comparisons for significance are paired t tests, except D, which shows an unpaired t test.

P. rapae Oviposition Is Reduced by ESP Activity

Because it seemed likely that P. rapae would encounter glucosinolate breakdown products rather than intact glucosinolates on the leaf surface, where there is also expression of both myrosinase and ESP (Andreasson et al., 2001; Husebye et al., 2002; Burow et al., 2007), we hypothesized that altered regulation of glucosinolate breakdown by ESP would influence P. rapae oviposition. Unlike in Col-0, the presence of ESP activity in Ler shifts the hydrolysis of glucosinolates toward production of nitriles (Lambrix et al., 2001). Direct comparison of oviposition on whole Col-0 and Ler plants was not feasible due to phenotypic differences in rosette size and flowering time that would strongly influence host plant choice by female P. rapae. However, in a detached-leaf assay (Fig. 2B), Col-0 leaves received significantly more eggs than Ler leaves (Fig. 3D), suggesting that a glucosinolate breakdown products produced via ESP could reduce P. rapae oviposition.

Analysis of methanol leaf surface washes was used to determine what indole glucosinolate breakdown products could be perceived by ovipositing P. rapae. IAN was 13-fold more abundant in Ler surface washes, whereas I3C was 5-fold more abundant in Col-0 surface washes (Fig. 4A). Control experiments showed increasing recovery of IAN from Col-0 leaves with wash times ranging from 5 to 20 s (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Recovery of IAN did not increase over time in 50% methanol surface washes. Spectrophotometric measurements showed very low absorption at 647 and 660 nm (chlorophyll A and B, respectively), which was not significantly different from blank controls (Supplemental Fig. S1B), indicating that there was no significant cell damage due to the methanol surface washes.

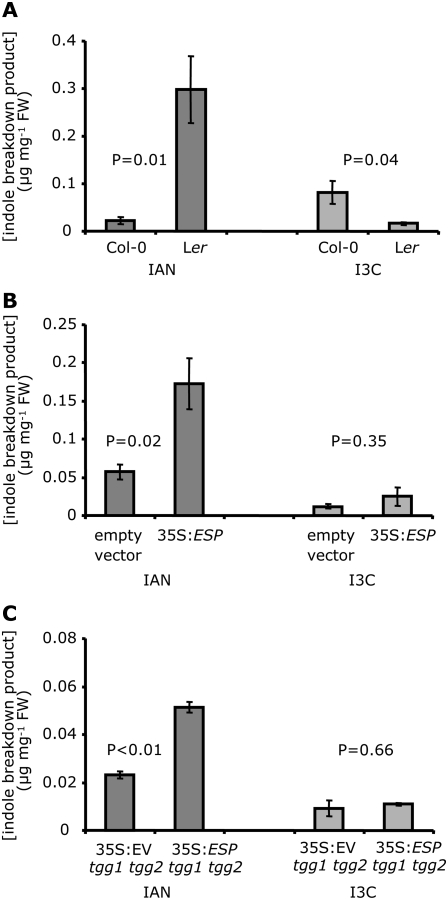

Figure 4.

I3C and IAN levels in wild-type Arabidopsis and mutants with altered glucosinolate profiles. A, IAN and I3C levels in the surface washes of ESP-expressing Ler and nonexpressing Col-0 plants (n = 4). B, IAN and I3C levels in the surface washes of transgenic Col-0 plants expressing a functional ESP and corresponding EV control plants (n = 4). C, IAN and I3C levels in the surface washes of 35S:ESP tgg1 tgg2 plants and EV control tgg1 tgg2 plants with tgg1 tgg2 plants (n = 5). Mean ± se, all comparisons for significance are paired t tests.

Because Ler and Col-0 plants differ in several aspects of glucosinolate biology (Kliebenstein et al., 2001; Lambrix et al., 2001), we used transgenic Col-0 overexpressing ESP from the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (35S:ESP; Burow et al., 2006b) in a more specific assay to study the effects of nitriles on P. rapae oviposition. Compared to empty-vector control plants, surface washes of 35S:ESP plants contained approximately 4-fold more IAN, whereas no significant difference was observed in the abundance of I3C (Fig. 4B). Although the ESP-overexpressing plants with high nitrile levels received significantly fewer P. rapae eggs (Fig. 3E), hatching success and larval weight gain were unaffected (Supplemental Fig. S2, A and B). Therefore, these data suggest that nitrile formation during glucosinolate breakdown can play a significant role in deterring oviposition.

ESP modulates glucosinolate breakdown through a direct interaction with myrosinase (Burow et al., 2006a). Therefore, given the clear effects of ESP overproduction (Fig. 3E), it seemed likely that the absence of myrosinase in tgg1 tgg2 mutants (Barth and Jander, 2006) would also influence P. rapae oviposition. Somewhat surprisingly, there was no significant difference in the number of eggs deposited on wild-type and tgg1 tgg2 mutant plants (Fig. 3F), even if the plants were mechanically damaged to promote glucosinolate breakdown prior to the oviposition assay (Fig. 3G).

Indole glucosinolates in damaged plant tissue undergo degradation that is independent of the TGG1 and TGG2 myrosinases (Barth and Jander, 2006). To investigate whether this myrosinase-independent breakdown influences P. rapae oviposition, we performed pair-wise comparisons of oviposition on cyp79B2 cyp79B3 tgg1 tgg2 quadruple mutants with tgg1 tgg2 and cyp79B2 cyp79B3 double mutants. Figure 3H shows that tgg1 tgg2 plants are more attractive than the quadruple mutant, whereas cyp79B2 cyp79B3 were equally attractive (Fig. 3I). This indicates that TGG1 and TGG2-dependent breakdown of indole glucosinolates is not essential for the production of P. rapae oviposition cues. Ovipositing P. rapae females are deterred by ESP activity in the tgg1 tgg2 mutant background (Fig. 3J) but not by plants transformed with an empty vector (EV) control (Fig. 3K). Because the action of ESP depends on the physical interaction with myrosinase (Lambrix et al., 2001; Burow et al., 2006a), this result indicates that some other myrosinase might break down indole glucosinolates in the tgg1 tgg2 mutant background. To test this hypothesis, indole glucosinolate breakdown products were measured in leaf surface washes of tgg1 tgg2 mutants, with and without ESP overexpression. Similar to results obtained for 35S:ESP and EV wild-type plants (Fig. 4B), there was a significantly elevated IAN in surface washes of 35S:ESP tgg1 tgg2 plants and no significant difference in I3C abundance (Fig. 4C).

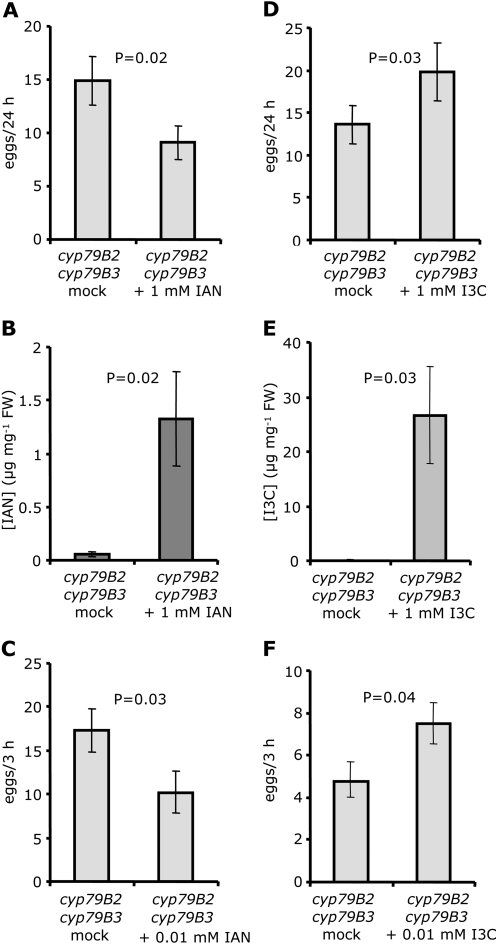

Oviposition Is Differentially Affected by Indole Glucosinolate Breakdown Products

Whereas wild-type Col-0 produces I3C as the primary I3M breakdown product, plants expressing ESP produce primarily IAN (Miao and Zentgraf, 2007; Burow et al., 2008). To determine whether these two metabolites differentially affect P. rapae oviposition, cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants, which contain low indole glucosinolate levels, were sprayed with IAN and I3C for oviposition experiments. Compared to mock-treated control plants, cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants treated with 1 mm IAN received fewer eggs (Fig. 5A), indicating that IAN deters oviposition. Because IAN is volatile, the presence of this compound on the leaves during the entire experiment was confirmed with a surface wash of the plants 24 h after treatment (Fig. 5B). IAN deters P. rapae oviposition over a wide range of concentrations, with a 0.01 mm IAN application still having a significant deterrent effect (Fig. 5C). IAN concentration in leaf surface washes of ESP-expressing plants (i.e. Ler and 35S:ESP; Fig. 4, A and B) is within the range of exogenous IAN applications that were tested.

Figure 5.

Oviposition in response to exogenous I3C and IAN. A, Oviposition choice test comparing mock-treated cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants and plants sprayed with 1 mm IAN (n = 10). B, IAN levels in the surface washes of cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants 24 h after spraying with 1 mm IAN (n = 4). C, Oviposition choice test comparing mock-treated cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants and plants sprayed with 0.01 mm IAN (n = 20). D, Oviposition choice test comparing mock-treated cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants and plants sprayed with 1 mm I3C (n = 20). E, I3C levels in the surface washes of cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants 24 h after spraying with 1 mm IAN (n = 4). F, Oviposition choice test comparing mock-treated cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants and plants sprayed with 0.01 mm I3C (n = 30). Mean ± se, all comparisons for significance are paired t tests, except for C and F, which show unpaired t tests.

In contrast to IAN addition, I3C-treated cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants received significantly more eggs than wild-type controls, indicating that this indole glucosinolate breakdown product is attractive to female P. rapae (Fig. 5D). I3C was abundant in surface washes 24 h after spraying Arabidopsis plants with 1 mm I3C (Fig. 5E). Because this I3C concentration greatly exceeded that found in surface washes of untreated Col-0 leaves (Fig. 4A), we also tested the oviposition response of P. rapae on leaves that were treated with 100-fold less I3C. Compared to mock-treated leaves, oviposition was higher on cyp79B2 cyp79B3 leaves treated with 0.01 mm I3C (Fig. 4F), showing that, like IAN, I3C functions as an oviposition cue over a wide range of concentrations.

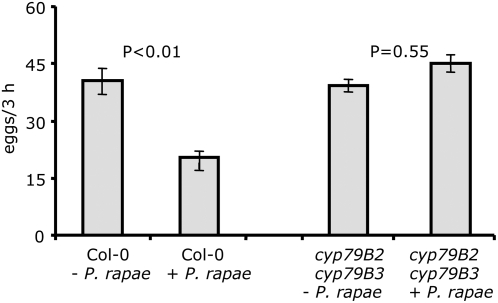

IAN in P. rapae Regurgitant Deters Oviposition

It was demonstrated previously that female P. rapae avoid ovipositing on plants infested with conspecific larvae (Rothschild and Schoonhoven, 1977). We observed this phenomenon with wild-type, but not cyp79B2 cyp79B3 mutant, plants (Fig. 6). The deterrent effects of larvae-infested plants (Fig. 6) and exogenous IAN (Fig. 5) suggested that IAN in larval regurgitant or frass could contribute to the avoidance of infested plants by female P. rapae.

Figure 6.

Oviposition responses after prior feeding by P. rapae larvae. Oviposition choice tests comparing Col-0 (n = 12) and cyp79B2 cyp79B3 (n = 20) plants with and without prior feeding by two third-instar P. rapae larvae for 3 h. Mean ± se, comparisons for significance are paired t tests.

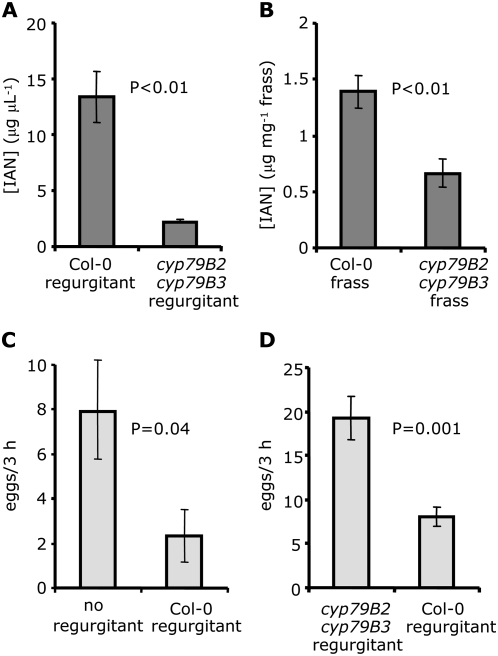

P. rapae larvae make use of gut-specific nitrile specifier protein to direct breakdown of glucosinolates to nitriles rather than the more toxic isothiocyanates, an adaptation that results in the presence of glucosinolate-derived nitriles in larval frass (Wittstock et al., 2004). Compared to larvae feeding on cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants, both regurgitant (Fig. 7A) and frass (Fig. 7B) from larvae feeding on Col-0 plants contain significantly higher amounts of IAN. During feeding bouts, lepidopteran larvae typically apply small amounts of regurgitant onto the feeding site (Truitt and Paré, 2004). Application of 2 μL fresh regurgitant from Col-0-fed larvae to cyp79B2 cyp79B3 leaves in a detached-leaf assay (Fig. 2B) showed that this regurgitant acts as a significant deterrent for P. rapae oviposition (Fig. 7C). The regurgitant applied to a single leaf (approximately 25 μg cm−2 IAN) was comparable to IAN levels detected in surface washes of Ler (10.6 μg cm−2 IAN) and 35S:ESP (6.4 μg cm−2 IAN), or cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants sprayed with 1 mm IAN (44.2 μg cm−2 IAN). A direct comparison of regurgitant from cyp79B2 cyp79B3-fed and Col-0-fed larvae showed that the deterrent effect requires the presence of an indole-derived compound in the host plant tissue (Fig. 7D). Addition of approximately 5 mg of larval frass, which has lower IAN levels than regurgitant (Fig. 7, A and B), to a detached-leaf assay (Fig. 2B) did not have a significant effect on P. rapae oviposition (cyp79B2 cyp79B3 leaves without frass, 6.6 ± 2.0 eggs; cyp79B2 cyp79B3 leaves with frass from Col-0-fed larvae, 5.2 ± 1.4 eggs; n = 20; P = 0.36; unpaired t test).

Figure 7.

Detection of IAN in larval regurgitant and frass. Larvae were starved for 10 h and subsequently allowed to feed from wild-type Col-0 or cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants. Larval regurgitant (A) and frass (B) were collected and IAN was determined by HPLC using a fluorescence detector (n = 5). C, Oviposition choice test comparing cyp79B2 cyp79B3 leaves with or without addition of 2 μL of regurgitant from Col-0-fed larvae (n = 15). D, Oviposition choice test comparing cyp79B2 cyp79B3 leaves treated with 2 μL of regurgitant from Col-0- or cyp79B2 cyp79B3-fed larvae (n = 15). Mean ± se, comparisons for significance are paired t tests (A and B) or unpaired t tests (C and D).

DISCUSSION

Taken together, our results lead us to propose an ecological role for nitrile formation in Arabidopsis, whereby some accessions can reduce P. rapae oviposition by modulating indole glucosinolate breakdown with ESP. Oviposition experiments with cyp79B2 cyp79B3 double mutants (Fig. 3A), which are almost completely devoid of indole glucosinolates (Zhao et al., 2002), suggest that these glucosinolates or their breakdown products serve as positive signals for P. rapae oviposition. However, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that altered production of auxin or other, as yet unknown indole metabolites that are metabolically downstream of CYP79B2 and CYP79B3 also contribute to the reduction in P. rapae oviposition on cyp79B2 cyp79B3 mutants.

Both a transgenic line overexpressing ESP and the ESP-producing Ler land race release more IAN in surface washes (Fig. 4, A and B) and are less attractive oviposition sites than wild-type Col-0 (Fig. 3, D and E). For as yet unknown reasons, ESP overexpression causes changes in the Arabidopsis glucosinolate profile (Burow et al., 2006b). In particular, the abundance of intact I3M is decreased (Supplemental Fig. S3), suggesting that ESP overproduction increases I3M turnover in transgenic plants. Concomitant with the I3M decrease, IAN abundance is significantly increased in surface washes of 35S:ESP plants, but I3C remains unchanged (Fig. 4, B and C). Therefore, consistent with the known function of ESP, a greater percentage of the I3M is being converted to IAN in the 35S:ESP transgenic plants.

Together, decreased oviposition on both cyp79B2 cyp79B3 and 35S:ESP plants (Fig. 3, A and E) showed that, although some indole compounds are oviposition stimulants, the nitrile breakdown products of indole glucosinolates are deterrent. This hypothesis was verified by showing that, when added to cyp79B2 cyp79B3 leaves, I3C stimulates oviposition, but IAN represses it (Fig. 5). However, neither I3C nor IAN influenced P. rapae oviposition when applied to green paper (Traynier and Truscott, 1991), suggesting that these chemical signals must be associated with other oviposition cues in plant leaves or that reaction with other leaf constituents produces the actual attractive and deterrent compounds. Leaf surface washes show that IAN and I3C could be encountered by ovipositing P. rapae (Fig. 4). Although it is possible that leakage of cell contents is induced by surface washes (Reifenrath et al., 2005), the lack of chlorophyll release under our experimental conditions (Supplemental Fig. S1B) shows that there is no significant damage of epidermal cells.

I3C is less volatile than IAN, but reactions with other plant metabolites (Agerbirk et al., 1998; Staub et al., 2002) could reduce the effective concentration of I3C that remains after application onto Arabidopsis leaves. Assays of macerated Arabidopsis tissue showed very little free I3C but abundant I3C adducts that were formed with ascorbate, glutathione, and amino acids (J.H. Kim and G. Jander, unpublished data). Therefore, even though a significant amount of I3C persists after being sprayed on the leave surface (Fig. 5E), at this point we cannot rule out the possibility that P. rapae oviposition is attracted by other metabolites that are formed by a reaction with I3C.

Assessment of leaf surface chemistry most likely occurs when Pieris butterflies drum leaves with their front tarsi prior to oviposition (Terofal, 1965; Schoonhoven et al., 2005). However, microscopic examination of the leaf surface did not reveal any physical damage (A. Renwick, personal communication). Given that P. rapae tarsi contain chemoreceptors that are particularly sensitive to aromatic and indole glucosinolates (Städler et al., 1995), it will be interesting to determine whether these same chemoreceptors are also sensitive to I3C and/or IAN. In contrast to P. rapae, which responds most strongly to aromatic and indole glucosinolates, the related species Pieris napi oleracea shows a preference for aliphatic glucosinolates during oviposition (Huang and Renwick, 1994). P. napi oleracea also uses glucosinolate detoxification enzymes to produce nitriles in the gut (Agerbirk et al., 2006); one might predict that the respective isothiocyanate and nitrile breakdown products of aliphatic glucosinolates would differentially affect oviposition by this species.

For ovipositing female Pieris, there is likely a significant selective advantage to using IAN or other nitriles as signals for avoiding plants with conspecific larvae. Prior larval feeding would have a deleterious effect on food availability, nutritional quality, and host defense responses. Compared to uninfested plants, Arabidopsis plants that were previously infested by P. rapae larvae showed increased resistance to subsequent attack by larvae of the same species (De Vos et al., 2006). This can be partly explained by the fact that P. rapae feeding induces a jasmonate burst (Reymond et al., 2000; De Vos et al., 2005), which would up-regulate plant defense pathways. Exogenous addition of jasmonate also reduces P. rapae oviposition on cabbage (Bruinsma et al., 2007).

Given the effects of ESP overproduction on IAN formation (Fig. 4B), the observation that P. rapae oviposition was unaffected by tgg1 tgg2 myrosinase knockout mutations (Fig. 3, F and G) was somewhat surprising. ESP activity leads to increased IAN production (Fig. 4, B and C) and reduced oviposition by P. rapae even in a tgg1 tgg2 background (Fig. 3J). Comparison of P. rapae oviposition on the cyp79B2 cyp79B3 tgg1 tgg2 and tgg1 tgg2 plants shows that the latter are significantly more attractive to adult female P. rapae (Fig. 3H). One possible explanation is that tgg1 tgg2 mutants may lack both positive and negative oviposition stimuli and that integration of these signals results in equal attractiveness for tgg1 tgg2 and Col-0 plants. Otherwise, ESP might interact with an as yet unknown thioglucosidase to modulate the breakdown of indole glucosinolates. Consistent with this hypothesis, indole glucosinolates, unlike aliphatic glucosinolates, suffer significant breakdown in macerated tissue of tgg1 tgg2 mutants (Barth and Jander, 2006), the relative amounts of I3C and IAN that are produced in macerated tissue are similar in tgg1 tgg2 and wild-type Col-0 (J.H. Kim and G. Jander, unpublished data), and 35S:ESP increases IAN abundance in surface washes of tgg1 tgg2 mutant plants (Fig. 4C). At least 40 Arabidopsis genes are predicted to encode functional myrosinases and other β-glucosidases (Xu et al., 2004), and it is quite possible that one or more of these enzymes interacts with ESP and contributes to indole glucosinolate breakdown in the foliage of tgg1 tgg2 mutant plants.

The apparent paradox of Arabidopsis producing I3C, a compound that promotes P. rapae herbivory, can be explained if ovipositing P. rapae are taking advantage of a defense system to which their own larvae are resistant but which deters other potential herbivores and pathogens. I3C is derived directly from indolylmethylisothiocyanate (Fig. 1), and isothiocyanate production generally contributes to herbivore and pathogen resistance in crucifers (Donkin et al., 1995; Lambrix et al., 2001; Agrawal and Kurashige, 2003). Further natural selection for I3C production could be provided by I3C adducts, some of which are deterrent to herbivorous insects (J.H. Kim and G. Jander, unpublished data).

Genetic variation in the foliar glucosinolate content of naturalized populations of Arabidopsis (Mauricio, 1998) suggests that this trait is under evolutionary selection. Similarly, natural variation in the expression of ESP and EPITHIOSPECIFIER MODIFIER PROTEIN1 (Zhang et al., 2006) indicates that there is selective pressure for maintaining both nitrile and isothiocyanate production in Arabidopsis populations. Sequencing of the ESP locus from several Arabidopsis accessions showed that ESP activity has been lost at least twice, once through absence of gene expression and once through a deletion in the coding region (Lambrix et al., 2001). Nevertheless, even though isothiocyanates are toxic to larvae of P. rapae and other Lepidoptera (Wadleigh and Yu, 1987; Li et al., 2000; Lambrix et al., 2001; Agrawal and Kurashige, 2003), many crucifers express nitrile-forming ESP.

Given that isothiocyanates are generally more toxic to insects than nitriles, it is perhaps surprising that ESP production is maintained in many isolates of Arabidopsis and other crucifers. Although the avoidance of IAN by ovipositing P. rapae can select for continued nitrile production, this is unlikely the only environmental cue that favors ESP expression. Additional natural selection that could account for the continued nitrile production by cruciferous plants includes: (1) IAN inhibits the growth of some phytopathogenic fungi (Pedras et al., 2002); (2) other, as yet unknown pathogens may be more sensitive to nitriles rather than isothiocyanates; (3) nitriles have toxic effects on some insects (Peterson et al., 2000; Galletti et al., 2001); (4) ESP-catalyzed nitrile production may allow plants to avoid specialist herbivores that use isothiocyanates as host recognition cues (Hovanitz et al., 1963; Bartlet et al., 1993; Ekbom, 1998; Rojas, 1999; Renwick et al., 2006); (5) volatile nitriles could provide an indirect defensive benefit, perhaps by alerting parasitoids and predators to the presence of insect herbivores; and (6) release of isothiocyanates rather than nitriles in response to damage might be more toxic to the plants themselves. Nevertheless, by demonstrating that nitrile production by ESP-producing Arabidopsis deters P. rapae oviposition, we have proved strong evidence for selective pressure that can favor the production of nitriles in cruciferous plants, even though these are otherwise less deterrent than isothiocyanates for many insect herbivores.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth and Insect Rearing

Seeds of wild-type Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) land races Col-0 and Ler were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (www.arabidopsis.org). Col-0 transgenic lines overexpressing ESP (line 37.3; Burow et al., 2006b) and EV (line 7.1) control transformants were kindly supplied by U. Wittstock and M. Burow (University of Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany). The Col-0 tgg1 tgg2 mutant was described previously (Barth and Jander, 2006). The Col-0 atr1D atr2D and Col-0 cyp79B2 cyp79B mutant lines were kindly supplied by J. Bender (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) and C. Celenza (Boston University, Boston).

Seeds were kept in 0.1% Phytagar (Invitrogen) for 24 h at 4°C prior to planting on Cornell mix (Landry et al., 1995) with Osmocoat fertilizer (Scotts). Plants were grown in Conviron growth chambers in 20- × 40-cm nursery flats at a photosynthetic photon flux density of 200 μmol m−2 s−1 and a 16-h photoperiod. The temperature in the chambers was 23°C and the relative humidity was 50%. Plants were grown for an additional 3 weeks and used in experiments before flowering.

A colony of Pieris rapae (kind gift of M. del Campo, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY) was maintained on cabbage (Brassica oleracea) plants var. Wisconsin Golden Acre (Seedway) under the same growth chamber conditions as those used for raising Arabidopsis. Adults were provided weekly with 50-mL solutions of 10% honey and 20% Suc.

Genetic Crosses

Arabidopsis crosses were performed as described by Weigel and Glazebrook (2002). A quadruple mutant (cyp79B2 cyp79B3 tgg1 tgg2) was made by crossing cyp79B2 cyp79B3 and tgg1 tgg2 plants. Individual F2 seeds were germinated on Murashige and Skoog medium supplemented with kanamycin (25 μg mL−1) to select for tgg1 tgg2 T-DNA insertions, transferred to soil, and screened by HPLC (Kim and Jander, 2007) for the low indole glucosinolate profile associated with cyp79B2 cyp79B3. Subsequently, leaves of these plants were screened by HPLC for lack of breakdown of aliphatic glucosinolates upon tissue rupture. Similarly, crosses were made between tgg1 tgg2 mutant plants and plants overexpressing 35S:ESP or transformed with an EV. Plants were first selected on Murashige and Skoog agar supplemented with gentamycin (100 μg mL−1) to select for the 35S:ESP construct and subsequently screened for the absence of glucosinolate breakdown following damage to identify those that were homozygous tgg1 tgg2 (see Supplemental Fig. S3, A–C, for glucosinolate profiles).

Leaf Surface Washes and Identification of Intact Glucosinolates

Fresh leaves (approximately 0.5 g) were harvested from Col-0, Ler, cyp79B2 cyp79B3, 35S:ESP, and EV plants and immediately dipped into 2 mL of 100% methanol for 20 s, while keeping the cut petiole out of the solution. IAN was identified by HPLC with a UV (280 nm) and a fluorescence detector (excitation 275 nm, emission 350 nm). To test whether the leaves were damaged during these surface washes, IAN levels were observed after leaf dips of 5, 10, 15, and 20 s in either 50% or 100% methanol. In addition, chlorophyll A (647 nm) and B (660 nm) were detected photospectrophotometrically in the leaf surface washes. Intact glucosinolates were extracted as described by Kim and Jander (2007). Briefly, the leaf surface washes were bound to a Sephadex anion-exchange column, treated with 25 nmol sulfatase, and eluted with 80% methanol. Desulfoglucosinolates were detected with a Waters 2695 HPLC and a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector at 229 nm, using sinigrin as an internal standard to compensate for losses during extraction.

Extraction and Identification of IAN in Larval Regurgitant and Frass

Third- and fourth-instar P. rapae larvae were starved for 10 h and subsequently allowed to feed from Arabidopsis Col-0 and cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants. Fresh frass and regurgitant, collected into 100% methanol by applying moderate pressure onto larvae using flexible forceps, were processed immediately. IAN in frass and regurgitant was identified by comparing the HPLC retention time and absorption using a fluorescence detector (excitation 275 nm, emission 350 nm) with that of commercially available IAN.

Oviposition Choice Experiments with P. rapae

Oviposition response experiments with P. rapae were always performed in a paired setup, where the Arabidopsis lines being compared were grown together at the same time in the same pot. One fertilized female P. rapae was provided four plants (two of each genotype) for 24 h in a 45- × 45- × 45-cm cage. Host preference was assessed by counting the number of eggs laid in 24 h.

For Ler plants, which have morphological differences relative to Col-0, attractiveness was assessed using a detached-leaf assay. An equal leaf area (0.75 cm2) of each genotype being compared was mounted on the top a 200-mL Erlenmeyer flask with Parafilm (Alcan Packaging; Fig. 2B). Subsequently, these flasks were transferred to a cage with approximately 25 female P. rapae for 3 h. Oviposition preference was determined by counting the number of eggs deposited on the Erlenmeyer flask around leaf material. Both experimental setups give similar results for a comparison between Col-0 and cyp79B2 cyp79B3. The same experimental setup was used to determine the effect of larval regurgitant on oviposition. Leaves of the low indole glucosinolate mutant cyp79B2 cyp79B3 were treated with 2 μL of freshly collected regurgitate. Oviposition preference was determined by counting eggs after 3 h.

To assess the attractiveness of I3C and IAN, cyp79B2 cyp79B3 plants were sprayed with 1 mm I3C, 0.01 mm I3C, 1 mm IAN, 0.01 mm IAN, or 80% methanol solvent control, and the number of eggs after 24 h was used as a measure of the attractiveness to adult female P. rapae.

Statistical Analysis

All results of choice experiments were tested for statistical significance in a paired t test (α = 0.05) for whole plants or with an unpaired t test (α = 0.05) for the detached-leaf assays, using SPSS10 for Windows (SPSS, 2005).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Effect of solvent concentration and duration of leaf surface dip on the detection of IAN and release of chlorophyll.

Supplemental Figure S2. Hatching success and larval growth on 35S:ESP and control plants.

Supplemental Figure S3. Glucosinolate content in progeny from crosses between 35S:ESP and tgg1 tgg2 plants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. del Campo for providing a P. rapae colony, U. Wittstock, M. Burow, J. Celenza, and J. Bender for Arabidopsis seed stocks; A. Renwick, J. Thaler, and M. del Campo for useful comments and suggestions; and John Ramsey, Minsang Lee, and Jae Hak Kim for their technical assistance.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant nos. IOS–0718733 and DBI–0500550 to G.J.), by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (award to M.d.V.), and by a fellowship to K.L.K. from C. Sampson.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Georg Jander (gj32@cornell.edu).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Agerbirk N, Müller C, Olsen CE, Chew FS (2006) A common pathway for metabolism of 4-hydroxybenzylglucosinolate in Pieris and Anthocaris (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Biochem Syst Ecol 34 189–198 [Google Scholar]

- Agerbirk N, Olsen CE, Sorensen H (1998) Initial and final products, nitriles and ascorbigens produced in myrosinase-catalyzed hydrolysis of indole glucosinolates. J Agric Food Chem 46 1563–1571 [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal AA, Kurashige NS (2003) A role for isothiocyanates in plant resistance against the specialist herbivore Pieris rapae. J Chem Ecol 29 1403–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson E, Bolt Jorgensen L, Hoglund AS, Rask L, Meijer J (2001) Different myrosinase and idioblast distribution in Arabidopsis and Brassica napus. Plant Physiol 127 1750–1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth C, Jander G (2006) Arabidopsis myrosinases TGG1 and TGG2 have redundant function in glucosinolate breakdown and insect defense. Plant J 46 549–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlet E, Blight MM, Williams IH (1993) The responses of the cabbage seed weevil (Ceutorhynchus assimilis) to the odor of oilseed rape (Brassica napus) and to some volatile isothiocyanates. Entomol Exp Appl 68 295–302 [Google Scholar]

- Blaakmeer A, Hagenbeek D, Van Beek TA, De Groot A, Schoonhoven LM, Van Loon JJA (1994) Plant response to eggs vs. host marking pheromone as factors inhibiting oviposition by Pieris brassicae. J Chem Ecol 20 1657–1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PD, Tokuhisa JG, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J (2003) Variation of glucosinolate accumulation among different organs and developmental stages of Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 62 471–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma M, Van Dam NM, Van Loon JJA, Dicke M (2007) Jasmonic acid-induced changes in Brassica oleracea affect oviposition preference of two specialist herbivores. J Chem Ecol 33 655–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burow M, Bergner A, Gershenzon J, Wittstock U (2007) Glucosinolate hydrolysis in Lepidium sativum: identification of the thiocyanate-forming protein. Plant Mol Biol 63 49–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burow M, Markert J, Gershenzon J, Wittstock U (2006. a) Comparative biochemical characterization of nitrile-forming proteins from plants and insects that alter myrosinase-catalysed hydrolysis of glucosinolates. FEBS J 273 2432–2446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burow M, Müller R, Gershenzon J, Wittstock U (2006. b) Altered glucosinolate hydrolysis in genetically engineered Arabidopsis thaliana and its influence on the larval development of Spodoptera littoralis. J Chem Ecol 32 2333–2349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burow M, Zhang ZY, Ober JA, Lambrix VM, Wittstock U, Gershenzon J, Kliebenstein DJ (2008) ESP and ESM1 mediate indol-3-acetonitrile production from indol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate in Arabidopsis. Phytochemistry (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- De Vos M, Van Oosten VR, Van Poecke RMP, Van Pelt JA, Pozo MJ, Mueller MJ, Buchala AJ, Métraux J-P, Van Loon LC, Dicke M, et al (2005) Signal signature and transcriptome changes of Arabidopsis during pathogen and insect attack. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 18 923–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos M, Van Zaanen W, Koornneef A, Korzelius JP, Dicke M, Van Loon LC, Pieterse CMJ (2006) Herbivore-induced resistance against microbial pathogens in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 142 352–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkin SG, Eiteman MA, Williams PL (1995) Toxicity of glucosinolates and their enzymatic decomposition products to Caenorhabditis elegans. J Nematol 27 258–262 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekbom B (1998) Clutch size and larval performance of pollen beetles on different host plants. Oikos 83 56–64 [Google Scholar]

- Galletti S, Bernardi R, Leoni O, Rollin P, Palmieri S (2001) Preparation and biological activity of four epiprogoitrin myrosinase-derived products. J Agric Food Chem 49 471–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geervliet JBF (1997). Infochemical use by insect parasitoids in a tritrophic context: comparison of a generalist and a specialist. PhD thesis. Wageningen Agricultural University, Wageningen, The Netherlands

- Glazebrook J, Ausubel FM (1994) Isolation of phytoalexin-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana and characterization of their interactions with bacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91 8955–8959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb CD, Abel S (2006) Glucosinolate metabolism and its control. Trends Plant Sci 11 89–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkier BA, Gershenzon J (2006) Biology and biochemistry of glucosinolates. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57 303–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey JA, Witjes LMA, Benkirane M, Duyts H, Wagenaar R (2007) Nutritional suitability and ecological relevance of Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica oleracea as food plants for the cabbage butterfly, Pieris rapae. Plant Ecol 189 117–126 [Google Scholar]

- Hovanitz W, Chang VCS, Honch G (1963) The effectiveness of different isothiocyanates on attracting larvae of Pieris rapae. J Res Lepid 4 249–259 [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Renwick JAA (1993) Differential selection of host plants by two Pieris species: the role of oviposition stimulants and deterrents. Entomol Exp Appl 68 59–69 [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Renwick JAA (1994) Relative activities of glucosinolates as oviposition stimulants for Pieris rapae and P. napi oleracea. J Chem Ecol 20 1025–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husebye H, Chadchawan S, Winge P, Thangstad OP, Bones AM (2002) Guard cell- and phloem idioblast-specific expression of thioglucoside glucohydrolase 1 (myrosinase) in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 128 1180–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander G, Cui J, Nhan B, Pierce NE, Ausubel FM (2001) The TASTY locus on chromosome 1 of Arabidopsis affects feeding of the insect herbivore Trichoplusia ni. Plant Physiol 126 890–898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Jander G (2007) Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) feeding on Arabidopsis induces the formation of a deterrent indole glucosinolate. Plant J 49 1008–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein DJ, Kroymann J, Brown P, Figuth A, Pedersen D, Gershenzon J, Mitchell-Olds T (2001) Genetic control of natural variation in Arabidopsis glucosinolate accumulation. Plant Physiol 126 811–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrix V, Reichelt M, Mitchell-Olds T, Kliebenstein DJ, Gershenzon J (2001) The Arabidopsis epithiospecifier protein promotes the hydrolysis of glucosinolates to nitriles and influences Trichoplusia ni herbivory. Plant Cell 13 2793–2807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry LG, Chapple CC, Last RL (1995) Arabidopsis mutants lacking phenolic sunscreens exhibit enhanced ultraviolet-B injury and oxidative damage. Plant Physiol 109 1159–1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Eigenbrode SI, Stringham G, Thiagarajah MH (2000) Feeding and growth of Plutella xylostella and Spodoptera eridania on Brassica juncea with varying glucosinolate concentrations and myrosinase activities. J Chem Ecol 26 2401–2419 [Google Scholar]

- Little D, Gouhier-Darimont C, Bruessow F, Reymond P (2007) Oviposition by pierid butterflies triggers defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 143 784–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauricio R (1998) Cost of resistance to natural enemies in field populations of the annual plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Am Nat 151 20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y, Zentgraf U (2007) The antagonist function of Arabidopsis WRKY53 and ESR/ESP in leaf senescence is modulated by the jasmonic and salicylic acid equilibrium. Plant Cell 19 819–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell-Olds T (2001) Arabidopsis thaliana and its wild relatives: a model system for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol Evol 16 693–700 [Google Scholar]

- Miles CI, del Campo ML, Renwick JA (2005) Behavioral and chemosensory responses to a host recognition cue by larvae of Pieris rapae. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol 191 147–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedras MS, Nycholar CM, Montaut S, Xu Y, Khan AQ (2002) Chemical defenses of crucifers: elicitation and metabolism of phytoalexins and indole-3-acetonitrile in brown mustard and turnip. Phytochemistry 59 611–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen BL, Chen S, Hansen CH, Olsen CE, Halkier BA (2002) Composition and content of glucosinolates in developing Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 214 562–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CJ, Cossé A, Coats JR (2000) Insecticidal components in the meal of Crambe abyssinica. J Agric Urban Entomol 17 27–36 [Google Scholar]

- Pigliucci M (2002) Ecology and evolutionary biology of Arabidopsis. In CR Somerville, EM Meyerowitz, eds, The Arabidopsis Book. American Society of Plant Biologists, Rockville, MD, doi/10.1199/tab.0003, www.aspb.org/publications/arabidopsis/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reifenrath K, Riederer M, Müller C (2005) Leaf surface wax layers of Brassicaceae lack feeding stimulants for Phaedon cochleariae. Entomol Exp Appl 115 41–50 [Google Scholar]

- Renwick JAA, Haribal M, Gouinguene S, Städler E (2006) Isothiocyanates stimulating oviposition by the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella. J Chem Ecol 32 755–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renwick JAA, Lopez K (1999) Experience-based food consumption by larvae of Pieris rapae: addiction to glucosinolates? Entomol Exp Appl 91 51–58 [Google Scholar]

- Renwick JAA, Radke CD, Sachdev-Gupta K, Städler E (1992) Leaf surface chemicals stimulating oviposition by Pieris rapae (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) on cabbage. Chemoecology 3 33–38 [Google Scholar]

- Reymond P, Weber H, Damond M, Farmer EE (2000) Differential gene expression in response to mechanical wounding and insect feeding in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12 707–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas JC (1999) Electrophysiological and behavioral responses of the cabbage moth to plant volatiles. J Chem Ecol 25 1867–1883 [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild M, Schoonhoven LM (1977) Assessment of egg load by Pieris brassicae (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Nature 266 352–355 [Google Scholar]

- Schoonhoven LM, Van Loon JJA, Dicke M (2005) Insect-Plant Biology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Schuhegger R, Nafisi M, Mansourova M, Petersen BL, Olsen CE, Svatos A, Halkier BA, Glawischnig E (2006) CYP71B15 (PAD3) catalyzes the final step in camalexin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 141 1248–1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Städler E, Renwick JAA, Radke CD, Sachdev-Gupta K (1995) Tarsal contact chemoreceptors response to glucosinolates and cardenolides mediating oviposition in Pieris rapae. Physiol Entomol 20 175–187 [Google Scholar]

- Staub RE, Feng C, Onisko B, Bailey GS, Firestone GL, Bjeldanes LF (2002) Fate of indole-3-carbinol in cultured human breast tumor cells. Chem Res Toxicol 15 101–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terofal F (1965) Zum Problem der Wirtsspezifität bei Pieriden (Lep.). Mitt Münch Ent Ges 55 1–76 [Google Scholar]

- Traynier RMM, Truscott RJW (1991) Potent natural egg-laying stimulant for cabbage butterfly Pieris rapae. J Chem Ecol 17 1371–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truitt CL, Paré PW (2004) In situ translocation of volicitin by beet armyworm larvae to maize and systemic immobility of the herbivore elicitor in planta. Planta 281 999–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon JJA, Blaakmeer A, Griepink FC, Van Beek TA, Schoonhoven LM, De Groot A (1992) Leaf surface compound from Brassica oleracea (Cruciferae) induces oviposition by Pieris brassicae (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Chemoecology 3 39–44 [Google Scholar]

- Wadleigh RW, Yu SJ (1987) Gluthatione transferase activity of fall armyworm larvae toward α,β-unsaturated carbonyl allelochemicals and its induction by allelochemicals. Insect Biochem 17 759–764 [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D, Glazebrook J (2002) Arabidopsis: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

- Wittstock U, Agerbirk N, Stauber EJ, Olsen CE, Hippler M, Mitchell-Olds T, Gershenzon J, Vogel H (2004) Successful herbivore attack due to metabolic diversion of a plant chemical defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101 4861–4864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Escamilla-Trevino L, Zeng L, Lalgondar M, Bevan D, Winkel B, Mohamed A, Cheng CL, Shih MC, Poulton J, et al (2004) Functional genomic analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana glycoside hydrolase family 1. Plant Mol Biol 55 343–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Ober JA, Kliebenstein DJ (2006) The gene controlling the quantitative trait locus EPITHIOSPECIFIER MODIFIER1 alters glucosinolate hydrolysis and insect resistnace in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18 1524–1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Hull AK, Gupta NR, Goss KA, Alonso J, Ecker JR, Normanly J, Chory J, Celenza JL (2002) Trp-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis: involvement of cytochrome P450s CYP79B2 and CYP79B3. Genes Dev 16 3100–3112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N, Tootle TL, Glazebrook J (1999) Arabidopsis PAD3, a gene required for camalexin biosynthesis, encodes a putative cytochrome P450 monooxygenase. Plant Cell 11 2419–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.