Since the description of the application of the bacteriophage cre-loxP system to mammalian cells (1) and the subsequent generation of the first cre-loxP mutant mouse (2), the cre-loxP system has been widely used to generate conditional knockout mice. Accurate genotyping of cre-loxP mice is critical to characterizing these mice. Because Southern blot analysis is tedious and time-consuming, genotyping often uses PCR strategies (3,4). While detection of a cre transgene in mouse genome by PCR is straightforward, errors in differentiating among wild-type (wt), lox, and the targeted deletion (del) alleles can be confounding. Here we report pitfalls that we have encountered in the course of generating mice with a conditional knockout of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor (igf1r) in the central nervous system (CNS).

To direct cre expression to the CNS, we utilized the intron 2 of human nestin gene and a minimal viral promoter to drive transgene cre expression. Nestin intron 2 contains a CNS-specific enhancer that is widely used to target transgene expression to the CNS (5). A construct containing human nestin intron 2 sequences was kindly provided by Dr. Claudia Kappen of the Mayo Clinic. Details of the generation of nestin-cre transgenic line will be described elsewhere. The igf1r-loxP line, in which the exon 3 of igf1r is flanked by two loxP sites (6), was the gift of Dr. Argiris Efstratiadis, Columbia University. Protocols involving these animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Routinely we bred the igf1r-loxP homozygote (lox/lox) with cre transgenic, igf1r-loxP heterozygotes (wt/lox/cre) to generate progeny of desired genotypes. To genotype the igf1r alleles, primer 1 (P1), 5′-CTCCAGAGCACATACTGACTCC-3′, and P2, 5′-AGCCAAATAAGCCCCAGTAACC-3′, were used to detect the wt allele (371 bp) and the lox allele (421 bp); while P3, 5′-AGGAACCCACAGTACTAGGAAC-3′, and P4, 5-GACTAACAGAGACTGCCAACAC-3′, were used to detect the del allele (2.5 kb), the wt allele (5.0 kb), and the lox allele (5.1 kb) (Figure 1A). To genotype the cre transgene, two primers (5′-GCCAGCTAAACATGCTTCATC-3′ and 5′-ATTGCCCCTGTTTCACTATCC-3) were utilized to amplify a cre-specific product of 727 bp. PCR parameters were 35 (for igf1r) or 30 (for cre) cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 65°C (for igf1r P1 and P2, P3 and P4) or 62°C (for cre) for 45 s, 72°C for 45s (for igf1r P1 and P2, and cre) or 2 min and 45 s (for igf1r P3 and P4). Genotyping was performed using genomic DNA extracted from tails.

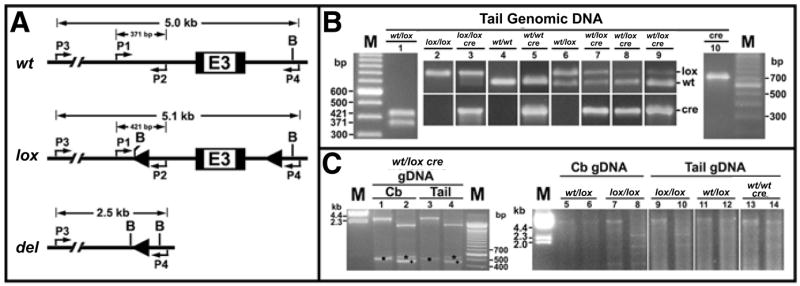

Figure 1. Genotyping of igf1r alleles and cre transgene by PCR.

(A) Diagrams depict the genomic region surrounding exon 3 (E3) of the wild-type (wt) igf1r allele, the igf1r-loxP (lox) allele with two loxP sites (arrowheads) flanking exon 3, and the deleted (del) igf1r allele that is produced from the lox allele after cre-mediated recombination. Positions of the two pairs of primers (P1 and P2, P3 and P4) on each allele are noted with their respective PCR product size. Restriction sites for BamHI (B) also are shown. (B) Using tail genomic DNA, the 727-bp cre-specific PCR product was detected only in nestin-cre transgenic mice (lanes 3, 5, and 7 to 10). Using P1 and P2 primers, only the 421-bp loxP allele-specific PCR product was amplified in lox/lox mice; while in wt/wt mice, only the 371-bp wt allele-specific PCR product was amplified. The presence of cre transgene did not affect the genotyping of these homozygotes (lanes 2 to 5). As expected, both the 421-bp and the 371-bp PCR products were detected in wt/lox mice (lanes 1 and 6). Presence of the cre transgene in wt/lox mice, however, was associated with marked variability in the intensity of the lox allele (lanes 7 to 9). In some mice the band representing the lox allele was so faint that wt/lox mice could be mistakenly genotyped as wt/wt (lanes 8 and 9). (C) When primers P3 and P4 were used, the 2.5 kb del allele was amplified not only from cerebellar (Cb) DNA but also from tail DNA samples of cre transgenic wt/lox mice (lanes 1 and 3), confirming that cre-mediated igf1r deletion also occurred in tail tissues. BamHI digestion of the 2.5-kb products yielded fragments of about 1.8, 0.53 (marked with an asterisk), and 0.17 kb (not shown) (lanes 2 and 4). A nonspecific PCR product was also seen in lanes 1 and 3 (marked with a dot) and in lanes 2 and 4 (marked with a plus), before and after BamHI digestion, respectively. Using P3 and P4 primers, an approximate 5.0 kb band (i.e., the 5.1 kb lox allele and/or the 5.0 kb wt allele) was detected in cerebellar DNA (lanes 5 and 7) and tail DNA (lanes 9 and 11) from non-cre-transgenic, wt/lox, or lox/lox mice. Only the 5.0 kb allele was amplified from wt/wt mouse DNA (lane 13). BamHI digestion of the 5.1-kb products yielded three fragments of approximately 2.8, 1.9 (lanes 8 and 10), and 0.4 kb (not shown); while digestion of the 5.0-kb wt products yielded two fragments of about 4.6 (lane 14) and 0.4 kb (not shown). The 5.1-kb and 5.0-kb products in lanes 5 and 11 were not distinguishable, and BamHI-digested products of the 5.1 kb DNA in lanes 6 and 12 were below the detection limit on the ethidium bromide-stained gel. As expected, the amplification efficiency for either the wt allele or the lox allele is very low, due to their large sizes and that the enzymes used for PCR were not long-range DNA polymerases. M, 100-bp DNA ladder (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA); gDNA, genomic DNA.

As expected, PCR amplification of the 727-bp cre-specific product reliably identified transgenic mice. Using P1 and P2 primers to genotype igf1r alleles, a non-cre-transgenic wt/lox heterozygote was identified by the PCR products of expected size (wt, 371 bp; lox, 421 bp). Both wt/wt and lox/lox homozygotes were also reliably identified. When wt/lox heterozygotes were cre-positive, however, considerable variability in the intensity of the 421-bp lox allele product was evident. While in some mice this lox allele product was only moderately reduced, in others it was so diminished as to be difficult to identify (Figure 1B). The latter could lead to erroneous genotyping of wt/lox mice as wt/wt mice. The apparent preferential amplification of the wt allele suggested a loss of the lox allele in tails of cre transgenic wt/lox mice.

These findings prompted us to hypothesize that cre-mediated and loxP-dependent genomic recombination occurred in the tail, resulting in the loss of the lox alleles. To test this hypothesis, we performed PCR with primers spanning the loxP sites (P3 and P4) using DNA from tail and cerebellum (a targeted site of the igf1r deletion). PCRs from cerebellar DNA of a cre-positive wt/lox heterozygous mouse yielded the expected 2.5-kb del product. As predicted, this product was digested by BamHI into three fragments of 1.8, 0.53, and 0.17 kb. Consistent with our hypothesis, the 2.5-kb del product with the same pattern of BamHI digestion also was detected in tail DNA. Furthermore, our data indicate that amplification of the del product is dependent on the presence of the cre transgene and at least one lox allele. First, in non-cre-transgenic loxP mice (wt/lox or lox/lox) the del product was not detected in either cerebellar or tail DNA; instead, we found PCR products consistent in size with the 5.0 kb wt allele or the 5.1 kb lox allele. Secondly, in cre-transgenic wt/wt mice, only the 5.0 kb wt allele, but not the del allele, was detected (Figure 1C). These findings confirm that cre-mediated, specific deletion of igf1r indeed occurred in tails of cre transgenic wt/lox mice.

A number of reports suggest that the cre transgene in our nestin-cre-igf1r-loxP mice is expressed in tail tissues. Nestin has been shown to be expressed in neural progenitor cells, developing myogenic and mensenchymal cells, hair follicle cells, proliferating endothelial cells, and nascent blood vessels (7). When the CNS-specific intron 2 enhancer was used to drive the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in a transgenic line, GFP was highly expressed in hair follicle progenitor cells (8). Such GFP-labeled hair follicle progenitor cells were shown to be capable of forming neurons and blood vessels (9,10). These findings indicate that hair follicle progenitors and newly formed vascular cells in tails of our nestin-cre-igf1r-loxP mice express Cre recombinase and account for our results.

We believe that our findings are not limited to the nestin-cre-igf1r-loxP mice used in this study. Cre transgenic lines may exhibit varying degrees of cre expression in nontarget tissues. Such nonspecific expression can be due to the influence of the chromosomal integration site, known as positional effects or transgene leakage, which is often independent of the promoter/enhancer used in the transgene. More commonly, however, nonspecific sites of expression result from use of a promoter/enhancer that does not function as specifically as expected. As more cre-loxP conditional knockout mice are generated, especially using tissue/cell-specific promoters/enhancers that have not been thoroughly studied, more undesirable cre-mediated gene deletions will likely occur. In such cases, the genotyping of cre-loxP mice may be affected, and these undesired knockout effects can confound the interpretation of the function of the gene of interest.

Our experience indicates that caution should be exercised when a two-primer PCR strategy is used to detect wt and lox alleles for genotyping cre-loxP mice. The detection of a del allele indicates the presence of the lox allele and the cre transgene. Leneuve et al. (4) have designed an elegant PCR strategy using three primers to simultaneously detect wt, lox, and del alleles in target tissues. This strategy also enables assessment of the efficiency of cre-mediated recombination. Because cre transgene expression in nontarget tissues is not anticipated, two-primer strategies usually are used to detect wt and lox alleles with DNA from nontarget tissues. Our findings point to the importance of the three-primer PCR approach to genotype cre-loxP mice even when DNA from nontarget tissues is studied.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Shouhong Xuan of Columbia University for her critical reading of this manuscript. This work is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant no. HD008299.

References

- 1.Sauer B, Henderson N. Site-specific DNA recombination in mammalian cells by the Cre recombinase of bacteriophage P1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5166–5170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu H, Marth JD, Orban PC, Mossmann H, Rajewsky K. Deletion of a DNA polymerase beta gene segment in T cells using cell type-specific gene targeting. Science. 1994;265:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.8016642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantamadiotis T, Taraviras S, Tronche F, Schutz G. PCR-based strategy for genotyping mice and ES cells harboring loxP sites. BioTechniques. 1998;25:968–972. doi: 10.2144/98256bm07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leneuve P, Zaoui R, Monget P, Le Bouc Y, Holzenberger M. Genotyping of Cre-lox mice and detection of tissue-specific recombination by multiplex PCR. BioTechniques. 2001;31:1156–1162. doi: 10.2144/01315rr05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yaworsky PJ, Kappen C. Heterogeneity of neural progenitor cells revealed by enhancers in the nestin gene. Dev Biol. 1999;205:309–321. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xuan S, Kitamura T, Nakae J, Politi K, Kido Y, Fisher PE, Morroni M, Cinti S, et al. Defective insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells lacking type 1 IGF receptor. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1011–1019. doi: 10.1172/JCI15276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mokry J, Nemecek S. Immunohistochemical detection of intermediate filament nestin. Acta Medica. 1998;41:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L, Mignone J, Yang M, Matic M, Penman S, Enikolopov G, Hoffman RM. Nestin expression in hair follicle sheath progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9958–9961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733025100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amoh Y, Li L, Katsuoka K, Penman S, Hoffman RM. Multipotent nestin-positive, keratin-negative hair-follicle bulge stem cells can form neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5530–5534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501263102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amoh Y, Li L, Yang M, Moossa AR, Katsuoka K, Penman S, Hoffman RM. Nascent blood vessels in the skin arise from nestin-expressing hair-follicle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13291–13295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405250101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]