Abstract

RPP2, an essential gene that encodes a 15.8-kDa protein subunit of nuclear RNase P, has been identified in the genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Rpp2 was detected by sequence similarity with a human protein, Rpp20, which copurifies with human RNase P. Epitope-tagged Rpp2 can be found in association with both RNase P and RNase mitochondrial RNA processing in immunoprecipitates from crude extracts of cells. Depletion of Rpp2 protein in vivo causes accumulation of precursor tRNAs with unprocessed introns and 5′ and 3′ termini, and leads to defects in the processing of the 35S precursor rRNA. Rpp2-depleted cells are defective in processing of the 5.8S rRNA. Rpp2 immunoprecipitates cleave both yeast precursor tRNAs and precursor rRNAs accurately at the expected sites and contain the Rpp1 protein orthologue of the human scleroderma autoimmune antigen, Rpp30. These results demonstrate that Rpp2 is a protein subunit of nuclear RNase P that is functionally conserved in eukaryotes from yeast to humans.

RNase P is a ubiquitous endoribonuclease that cleaves 5′ terminal leader sequences of precursor tRNAs to generate 5′ mature termini of tRNAs (1, 2). It is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme composed of RNA and protein subunits. Eubacterial RNase P consists of a single catalytic RNA subunit (3) and a single, small, very basic protein cofactor (≈14 kDa) that increases the catalytic activity and substrate range of the holoenzyme (4, 5). Archaeal and eukaryotic RNase P RNA have not been shown to be catalytic in vitro in the absence of protein subunits, despite the genetic, biochemical, and phylogenetic evidence which showed that the RNA subunits of these enzymes are essential for activity and share significant structural similarities to the eubacterial RNAs (6–9). The dependence of eukaryotic RNase P on protein components suggests that the protein subunits may be required for a direct role in the catalytic activity of the enzyme. However, the exact identity of all the eukaryotic protein subunits has not yet been determined. At least seven proteins are associated with highly purified RNase P from human cells: Rpp14, Rpp20, Rpp25, Rpp29, Rpp30, Rpp38, and Rpp40 (10). Genetic and biochemical approaches in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identified four proteins—Pop1, Pop3, Pop4 (homologue of Rpp29), and Rpp1 (homologue of Rpp30)—that associate with RNase P; these proteins also associate with a related enzyme called RNase mitochondrial RNA processing (RNase MRP; refs. 11–14).

Yeast nuclear RNase P and RNase MRP are related ribonucleoprotein (RNP) enzymes essential for biosynthesis of tRNAs and rRNAs (15–18). The RNA component of RNase MRP has secondary structure similarity to RNase P RNA (19), and both enzymes appear to share protein subunits in vivo. It has been suggested that RNase P is an ancestor of RNase MRP, because RNase MRP has been found only in eukaryotes (20). Yeast RNase MRP functions in processing of precursor rRNAs at the A3 site in the internal transcribed sequence of the 35S precursor rRNA (21) and also cleaves RNA primers for mitochondrial DNA replication (22, 23). Although RNase MRP does not cleave ptRNAs in vitro, its role in rRNA processing is affected by proteins that associate with RNase P in vivo (11–14). RNase P functions in the biosynthesis of tRNAs (8) and appears to have a role in rRNA processing in yeast (14, 24). Thus, processing of precursor tRNA and rRNA may be coordinated by the activity of these two related enzymes (14).

We report here the cloning and functional characterization of an essential (Rpp2, 15.8-kDa) subunit of S. cerevisiae nuclear RNase P. The gene for this protein, RPP2, was identified by virtue of its homology with a human Rpp20, which copurifies with human RNase P (10, 25). The role of Rpp2 protein in processing of precursor tRNA and the 35S precursor rRNA is similar to that of Rpp1, a previously characterized yeast RNase P protein subunit (14). A conditional lethal yeast strain of Rpp2 revealed multiple defects in processing of precursor tRNAs and precursor 35S rRNA. These results demonstrate that Rpp2 is a protein subunit of nuclear RNase P that is functionally conserved in eukaryotes from yeast to humans (10, 12, 14, 25).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Media, and General Procedures.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are VS200 (MATa/MATα GAL1/GAL1 ade2–101/ade2–101 leu2–3, 112/leu2–3, 112 ura5–52/ura5–52 his3-Δ200/his3-Δ200 lys2–801/lys2–801 trp1-Δ63/trp1-Δ63 RPP2/rpp2∷HIS3), VS202A (MATa GAL1 ade2–101 leu2–3, 112 ura5–52 his3-Δ200 lys2–801 trp1-Δ63 rpp2∷HIS3 + pRS314FHRPP2(TRP1)), VS203 (MATa GAL1 ade2–101 leu2–3, 112 ura5–52 his3-Δ200 lys2–801 trp1-Δ63 rpp2∷HIS3 + pRS314FHRPP2(TRP1) + pRS3163xRPP1(URA3)), VS211B (MATa GAL1 ade2–101 leu2–3, 112 ura5–52 his3-Δ200 lys2–801 trp1-Δ63 rpp2∷HIS3 + pRS314RPP2(TRP1)), VS214 (MATa/MATα GAL1/GAL1 ade2–101/ade2–101 leu2–3, 112/leu2–3, 112 ura5–52/ura5–52 his3-Δ200/his3-Δ200 lys2–801/lys2–801 trp1-Δ63/trp1-Δ63), VS301A (MATa GAL1 ade2–101 leu2–3, 112 ura5–52 his3-Δ200 lys2–801 trp1-Δ63 rpp2∷HIS3 +pYCPGAL∷rpp2 (URA3)), and VS301D (MATa GAL1 ade2–101 leu2–3, 112 ura5–52 his3-Δ200 lys2–801 trp1-Δ63 RPP2 +pYCPGAL(URA3)). Genetic techniques and preparations of standard media were performed according to established procedures (33). The identities of all constructs were verified by sequencing. Oligonucleotides used in this study are: RPP2HIS5, 5′-AACGAGTAACGAAACACCCATCTTTGAAAACTCTAACGCATAAGCCTCGTTCAGAATGACACG-3′; RPP2HIS3, 5′-ATAGTATACAATAACAATGAGCGCTAAAAGTATGACATATTAAACTCTTGGCCTCCTCTAG-3′; RPP2FH, 5′-TGCACCCAGGATGGACTACAAGGATGACGATGACAAGCATCATCATCATCATCATGCTATGGCACTCAAAAAGAATACAC-3′; RPP2J, 5′-GCCATCCTGGGTGCAG-3′; RPP2R, 5′-TCCCCGCGGGGACGGCCGCTTCATCAATTCTGTTTACCCTTG-3′; RPP2T, 5′-CGGAATTCGTTTATCAAGTGGATATGC-3′; oligonucleotide a is oligonucleotide no. 5 in ref. 14; oligonucleotide b, 5′-GGCCAGCAATTTCAAGT-3′; SNR190, 5′-GGCTCAGATCTGCATGTGTTG-3′.

Gene Disruption.

A genomic clone encoding the RPP2 locus was identified in the S. cerevisiae genome database (SGD) and obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC) as a cosmid (ATCC 71051), which was sequenced previously. A 2.2-kb AflII fragment that encodes RPP2 was subcloned into pBluescript (SK) vector to generate pRPP2SK. Using oligonucleotides RPP2HIS5 and RPP2HIS3, the HIS3 gene was amplified by PCR from plasmid pRS313(HIS3). The resulting 1.2-kb fragment was gel-purified and then was integrated at the RPP2 genomic locus in the diploid yeast strain VS214 to generate VS200. The correct replacement of one allele was verified by PCR digest analysis. Oligonucleotides RPP2R and RPP2T were used to amplify genomic DNA isolated from VS200, and the resulting (1.6-kb) fragment encoding HIS3 and flanking sequences of RPP2 was mapped with restriction enzymes.

Construction of Plasmids.

A plasmid encoding the FLAG-HIS epitope-tagged RPP2, pRS314FHRPP2(TRP1), was generated by PCR using oligonucleotides RPP2FH, RPP2J, RPP2R, RPP2T, and pRPP2SK as template. The PCR fragment was subcloned into pRS314(TRP1) plasmid to generate pRS314FHRPP2. To generate the GAL∷RPP2 construct, the RPP2 coding sequence was subcloned from pRPP2SK as a 0.9-kb BstNI fragment into pYCPGAL(URA3) to generate pYCPGAL∷rpp2.

Strain Construction.

RPP2-disrupted diploid strain VS200 was transformed with pRS314FHRPP2 and sporulated. The resulting spores were dissected, and spores that had a disrupted RPP2 gene but harbored pRS314FHRPP2 plasmid were viable (VS202A). The two haploids that depend on the plasmid pRS314FHRPP2 grew at rates identical to the wild-type haploids (VS211B). VS202A also was transformed with pRS316–3xmyc∷RPP1 (14) and grown in media lacking uracil, to generate VS203. VS200 was transformed with pYCPGAL∷rpp2 sporulated, and germinated on medium containing galactose. Viable spores were obtained from several independent tetrads. Haploids with a disrupted RPP2 allele that depend on pYCPGAL∷rpp2 (VS301A) grew on galactose-containing plates but not on glucose-containing plates (data not shown).

Other Methods.

Immunoprecipitations, RNase P and RNase MRP enzymatic assays, and RNA extraction and analysis were performed as described; immunoprecipitates were washed in IP150 buffer (14). Primer extension analysis of the cleavage of internal transcribed sequences 141 (ITS141) prRNA substrate at the A3 site was performed by using oligonucleotide 6 (14), according to manufacturer’s procedure for reverse transcriptase (Promega).

RESULTS

An Essential Yeast Gene Encodes a Homologue of Human Rpp20, a Protein Subunit of Nuclear RNase P.

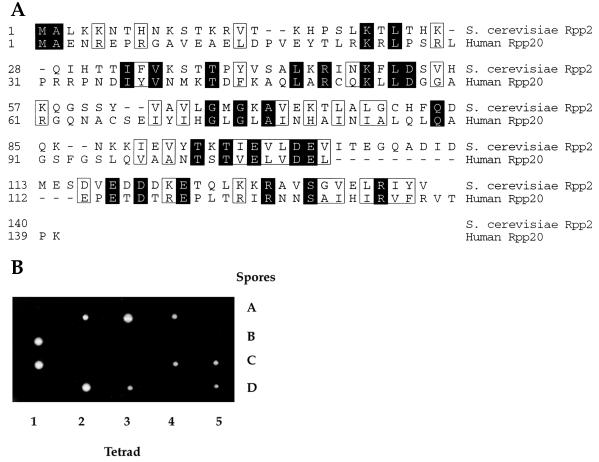

We identified the RPP2 gene by searching the SGD (26) with the protein sequence of the human Rpp20 protein, which copurifies with human nuclear RNase P (10, 25). We used a computational sequence search algorithm (blastp) (27) to identify a previously uncharacterized ORF, YBR167c. This gene is now designated RPP2, for RNase P protein 2. The yeast Rpp2 protein is a small, highly basic protein (predicted molecular mass, 15.8 kDa; pI 9.34), which has 14% amino acid sequence similarity with human Rpp 20 (Fig. 1A). The carboxyl-terminal ends of the human Rpp20 and the yeast Rpp2 also show weak amino acid sequence similarity with a short segment of the yeast protein Rrp5 (28), which functions in rRNA processing (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Yeast Rpp2 is homologous to the human Rpp20 protein. (A) The amino acid sequence of the yeast Rpp2 protein is aligned with the amino acid sequence of the human Rpp20 protein. The RPP2 gene is encoded on yeast chromosome II by the ORF, YBR167c. The amino acid sequences of both proteins are numbered from the N terminus. Shaded amino acids represent identical residues, and boxed amino acids represent similar residues. (B) The heterozygous diploid strain VS200, RPP2/rpp2∷HIS3, is shown after segregation of four spores (A–D) from five independent tetrads (1–5). All spores segregated 2:2 for cell viability.

To determine whether the putative protein encoded by RPP2 is an essential gene, we disrupted this gene by replacing it with the HIS3 gene (see Materials and Methods). The heterozygous RPP2/rpp2∷HIS3 strain (VS200) was sporulated, and subsequent tetrad analysis showed 2:2 segregation for cell viability (Fig. 1B). All viable spores were His-, indicating that they had the wild-type RPP2 allele. Therefore, RPP2 is an essential gene in S. cerevisiae.

Construction of an Epitope-Tagged Allele of RPP2.

Previously we used a triple c-myc epitope to characterize the yeast RNase P protein subunit, Rpp1 (14). An epitope-tagged strain of RPP2 was constructed by inserting a DNA fragment that encodes both FLAG and HIS epitopes at the N terminus of the RPP2 gene by PCR amplification in a low-copy-number plasmid (pRS314) (see Materials and Methods). The resulting strain of S. cerevisiae (VS202A) grew at rates identical to wild-type cells, suggesting that the FLAG-HIS-RPP2 allele is fully functional (data not shown).

Rpp1, RNase P, and RNase MRP Coprecipitate with FLAG-HIS Rpp2 Fusion Protein.

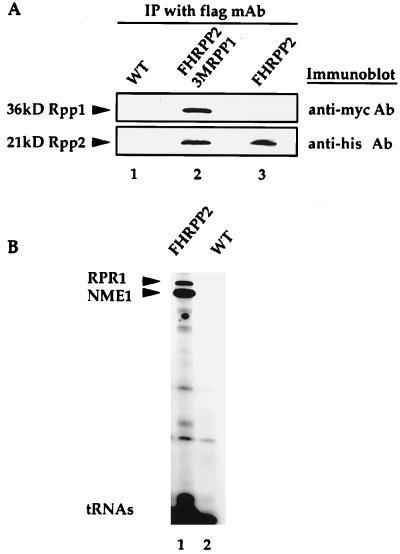

To determine whether or not Rpp2 protein associates with Rpp1, RNase P, and RNase MRP, we performed an immunoprecipitation experiment. Anti-flag immunoprecipitates derived from cells that contained FLAG-HIS epitope-tagged Rpp2 (VS202A), and individually tagged 3xmyc-Rpp1 and FLAG-HIS-Rpp2 proteins (VS203) showed that the two proteins coexist in one complex. Coprecipitation of Rpp1 and Rpp2 proteins was demonstrated by resolving the anti-flag immunoprecipitates on SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting with polyclonal anti-myc and anti-poly-his antibodies to detect Rpp1 and Rpp2, respectively (Fig. 2A). Rpp1 migrates as a 36-kDa protein, and the Rpp2 protein migrates as a 21-kDa protein—the sizes are consistent with those predicted for the fusion proteins.

Figure 2.

Rpp2 protein coimmunoprecipitates with the Rpp1 protein and the RNase P and RNase MRP RNAs. (A) Immunoprecipitates derived from wild-type (untagged) cells (VS211B, lane 1), FLAGHISRPP2 and 3xmycRPP1 double epitope-tagged cells (VS203, lane 2), and FLAGHISRPP2-tagged cells (VS202A, lane 3) were denatured, resolved on a 12% SDS/PAGE gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted with polyclonal antibodies against the myc and his epitopes. (B) Immunoprecipitated RNAs extracted from equivalent amounts of anti-flag Ab-IgG-agarose beads that were incubated with equivalent amounts of cell extracts from FLAGHISRPP2-tagged cells (VS202A, lane 1) and wild-type (untagged) cells (VS211B, lane 2) were 3′ end-labeled with [5′-32P]pCp and separated on an 8% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gel. The upper band is RNase P RNA (RPR1), and the lower band is RNase MRP RNA (NME1). tRNA species are found nonspecifically in both immunoprecipitates.

RNase P RNA (RPR1) and RNase MRP RNA (NME1) were shown to coimmunoprecipitate with the epitope-tagged Rpp2 protein by extraction and 3′ end labeling of RNA bound to the anti-flag immunoprecipitates, which were derived from FLAG-HIS-Rpp2-tagged cells (VS202A). Extracts from VS202A and wild-type cells (VS211B) were incubated with anti-FLAG mAb (Eastman Kodak). RNA extracted from these immunoprecipitates was 3′ end-labeled with [32P]pCp and analyzed by denaturing gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2B). The arrows in Fig. 2B point to two bands that represent the RNase P RNA (RPR1) and RNase MRP RNA (NME1), which are the major RNAs found in the precipitate derived from FLAG-HIS RPP2-tagged cells but not from the control (untagged) cell lysates.

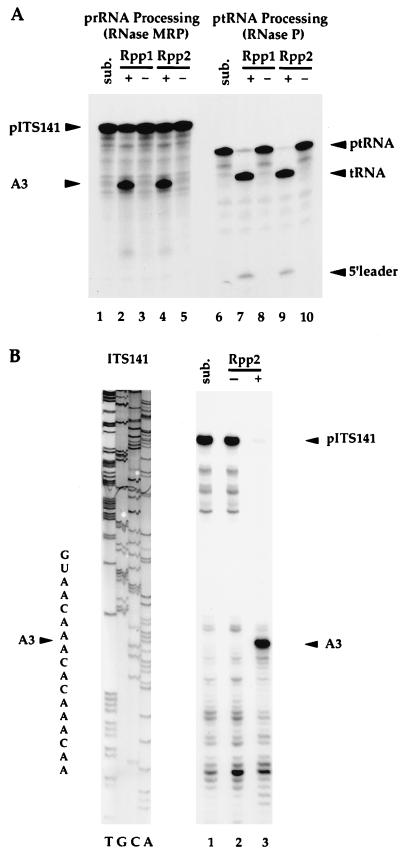

The association of Rpp2 protein with enzymatically active RNase P and RNase MRP holoenzymes was also demonstrated by immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitates derived from FLAG-HIS-tagged Rpp2 cells were resuspended with radiolabeled ptRNASer (29) to assay RNase P activity and with radiolabeled prRNA (ITS141) (see ref. 14) to assay rRNA processing at the A3 site. Both substrates were cleaved accurately at the appropriate cleavage sites (Fig. 3). We conclude that Rpp2 is a component of, or is tightly associated with, catalytically active RNase P and RNase MRP. These data also suggest that processing of tRNA and rRNA precursors may depend in part on Rpp2 function in vivo.

Figure 3.

RNase P and RNase MRP coprecipitate with Rpp2 and accurately cleave both ptRNA and prRNA substrates. (A) Immunoprecipitates derived from wild-type cells (−; VS211B) and individually epitope-tagged Rpp1 (+; VS162B, see ref. 14) and Rpp2 (+; VS202A) cells were resuspended with internally labeled prRNA (ITS141, see ref. 14) (lanes 1–5) and ptRNASer (lanes 6–10) and incubated for 1 hr at 37°C (see Materials and Methods). Sub. (lane 1) is precursor rRNA, ITS141, and sub. (lane 6) is precursor tRNASer. (B) The ITS141 RNA was transcribed in vitro and was incubated with immunoprecipitates derived from wild-type cells (−; VS211B, lane 2) and FLAGHISRPP2 cells (+; VS202A, lane 3). Sub. (lane 1) is ITS141. Accurate cleavage of the prRNA substrate at the A3 cleavage site was determined by primer extension analysis of the cleaved products. A 5′ end-labeled oligonucleotide (Oligo 6, which hybridized 40 nt 3′ to the A3 cleavage site; see ref. 14) was used in a primer extension reaction. Primer extension products were resolved on an 8% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gel. ITS141 was sequenced with the same oligonucleotide as was used for the primer extension reaction.

Defects in tRNA and rRNA Processing of a Conditional Lethal Allele of RPP2 Show that Rpp2 Is Required for RNase P and RNase MRP Activities in Vivo.

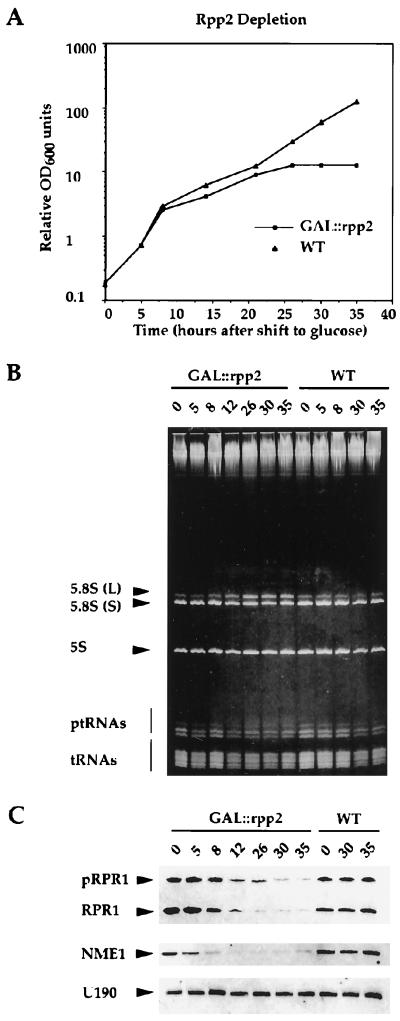

The regulatable GAL1 promoter was used to construct a conditional lethal strain of RPP2 to investigate RNA processing events on depletion of Rpp2 in vivo. The resulting strain, GAL∷rpp2, grew indistinguishably from wild-type cells in galactose-containing medium. However, the GAL∷rpp2 strain slowed growth at 12 hr after a shift into glucose-containing medium, which represses the GAL1 promoter (Fig. 4A). Previously, we showed that depletion of Rpp1 affects both tRNA and 35S rRNA processing in yeast (14). Because the Rpp1 and Rpp2 proteins are found to coimmunoprecipitate and their respective human homologues, Rpp30 and Rpp20, cofractionate biochemically (10, 25), we wanted to investigate whether Rpp2-depleted yeast cells would exhibit defects in RNA processing that are similar to Rpp1-depleted cells. Total RNA was extracted from the GAL∷rpp2 strain at different times after a switch from galactose-containing to glucose-containing medium. This RNA was analyzed by ethidium bromide staining and by Northern blot analysis to detect RNA processing defects on depletion of the Rpp2 protein.

Figure 4.

Rpp2 is required for processing of both ptRNA and 5.8S rRNA, and for the steady-state levels of both RNase P and RNase MRP RNAs. (A) Growth curve of wild-type (WT, VS301D) and Rpp2-depleted (GAL∷rpp2, VS301A) cells after a switch from galactose- to glucose-containing medium at t = 0. Total RNA was extracted from exponentially growing cells (OD600 < 0.5) at t = 0, 5, 8, 12, 26, 30, and 35 hr after a switch from galactose- to glucose-containing medium. (B) Total RNA isolated at the specified times from GAL∷rpp2 (VS301A) and wild-type (VS301D) cells was separated on an 8% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gel and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. The relative migration positions of 5.8S (L), 5.8S (S), 5S rRNAs, and precursor and mature tRNAs are indicated. (C) The gel from B was transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane by electroblotting and hybridized with 32P-labeled complementary DNA probes to RNase P RNA (RPR1), RNase MRP RNA (NME1) (see ref. 14), and γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotide complementary to snRNA 190 (see Materials and Methods). pRPR1 is the putative precursor of RPR1 RNA that has extra sequences at both termini (8).

As observed in conditional mutants of RNase P RNA (24) and the Rpp1, Pop1, Pop3, and Pop4 proteins that associate with RNase P (11–14), depletion of the Rpp2 protein resulted in accumulation of precursor tRNAs (Fig. 4B). Rpp2 depletion also caused an increase in the abundance of the 5.8S rRNA (L) relative to the 5.8S rRNA (S), as judged by ethidium bromide staining (Fig. 4B). Because this phenotype is associated with depletion of the RNase P and RNase MRP RNAs (ref. 14; RPR1 and NME1, respectively), we used specific probes for these RNAs to determine their steady-state levels. The amount of Rpp2 protein correlates with the maturation and stability of both RNase P RNA (RPR1) and RNase MRP (NME1) RNA, as shown by the decreasing amount of both RNAs on depletion of Rpp2 (Fig. 4C). In contrast, depletion of Rpp2 does not affect steady-state levels of the snRNAs 190 (Fig. 4C) and U14 (data not shown). This may reflect a requirement for the intact structure of the RNase P and RNase MRP particles to prevent degradation of the RNA components.

Northern blot analysis of total RNA from Rpp2-depleted cells confirmed the defect in processing of ptRNAs, which accumulate with an unprocessed intron and both 5′ and 3′ extended ends (Fig. 5A). Defects in the processing of 35S rRNA were shown with oligonucleotides that hybridize to the ITS1 and ITS2 (see Fig. 6A). Fig. 5B shows that Rpp2-depleted cells accumulate 24S, 21S, 17S, 8S, and 7S rRNA species, which are detected with an oligonucleotide that hybridizes between site A2 and A3 in ITS1 (oligonucleotide a, see Fig. 6A). The 24S and 21S rRNA species represent aberrant intermediates, which are expected to contain the unprocessed 5′ external transcribed sequence and ITS1 (Fig. 5B; see ref. 14 and http://speedy.mips.biochem.mpg.de/mips/yeast/index for a schematic plan of 35S precursor rRNA processing in S. cerevisiae). The aberrant 17S, 8S, and 7S rRNA species are also observed on depletion of the Rpp1 protein subunit of RNase P (14).

Figure 5.

Rpp2 is required for processing of both ptRNA and prRNA. (A) Total RNA from Fig. 4B was probed with a γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotide complementary to mature tRNALeu. “PT” is the primary transcript (boxes represent the mature regions of the tRNA, and lines represent extra sequences at both of its termini and an intron); “IVS” is the ptRNA that contains the intron but has been processed at both of its 5′ and 3′ termini; “5′ 3′” is the spliced ptRNA that is unprocessed at both 5′ and 3′ ends; “tRNA” is the fully processed tRNA. The curvature in the migration of the tRNA bands is due to an artifact in the electrophoretic separation. (B) Total RNA from GAL∷rpp2 (VS301A) and wild-type (VS301D) cells was separated on a 1.2% agarose gel, transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane by capillary transfer, and blotted with an oligonucleotide that is complementary to a region between sites A2 and A3 in the ITS1 of the primary 35S rRNA transcript (oligonucleotide 5, see ref. 14). The 24S rRNA intermediate is expected to extend from the 5′ end of the 5′ ETS to the 3′ end of 5.8S rRNA. The 21S rRNA is expected to extend from the 5′ end of 18S rRNA to the 3′ end of 5.8S rRNA, and the 17S rRNA is expected to extend from within 18S rRNA and 3′ end of 5.8S rRNA. The 8S rRNA is expected to extend from the 5′ end of ITS1 to the 3′ extended end of 5.8S rRNA. The 7S RNA is a 5′ extended precursor of 5.8S rRNA.

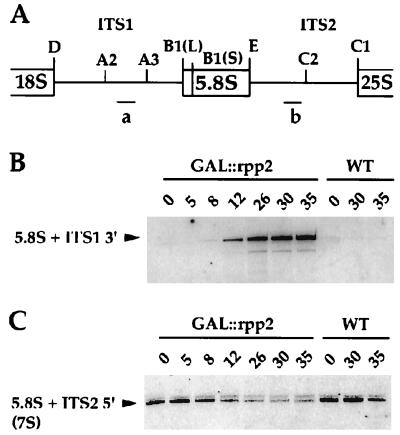

Figure 6.

Rpp2 is required for processing of 5.8S rRNA in vivo. (A) Schematic diagram of the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of the 5.8S rRNA in a fragment of the 35S primary rRNA transcript. Oligonucleotide a and b hybridize to ITS1 (between site A2 and A3) and ITS2 (between E and C2), respectively. (B) Northern blot of total RNA isolated from GAL∷rpp2 (VS301A) and from wild-type (VS301D) cells at the indicated times, after a switch from galactose- to glucose-containing medium. The RNA was probed with a γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotide a, which is complementary to ITS1. (C) Northern blot as in B, but probed with a γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotide b, which is complementary to ITS2.

Defects in processing of 5.8S rRNA were also confirmed by Northern blot analysis with oligonucleotides that hybridize to the ITS1 and ITS2 (Fig. 6A). This analysis revealed defects in processing of the 5.8S rRNA (Fig. 6 B and C). On depletion of Rpp2, an oligonucleotide that is complementary to the region between sites A2 and A3 (oligonucleotide a) detects an aberrant 5.8S rRNA that extends from site A2 to the 3′ end of 5.8S rRNA (Fig. 6B). This rRNA is expected to accumulate in the absence of cleavage at the A3 site. Additionally, Rpp2-depleted cells are depleted in 3′ extended 5.8S rRNA, 7S(S), which is detected with an oligonucleotide that hybridizes to ITS2 between site E and C2 (oligonucleotide b, Fig. 6 A and C). This result suggests a defect in 5.8S rRNA processing at its 3′ terminus as a consequence of inhibition of processing at its 5′ terminus. Interestingly, as in Rpp1-depleted cells, 18S and 25S rRNA levels remain unaffected (data not shown). These results demonstrate the characteristic loss of both RNase P and RNase MRP activities in vivo as a result of Rpp2 depletion and suggest that Rpp2 is required for the function of both enzymes in vivo.

DISCUSSION

We have identified a gene, RPP2, which encodes a protein component of nuclear RNase P in S. cerevisiae. This gene was identified by searching the yeast genome database for protein homologues of the human Rpp20, one of seven proteins (Rpp14, Rpp20, Rpp25, Rpp29, Rpp30, Rpp38, and Rpp40) that copurified with human RNase P (10, 25). Rpp2 is a protein subunit of nuclear RNase P that is conserved from yeast to humans (10, 12, 14). The other human Rpp proteins do not show significant sequence similarity to any yeast genes (data not shown).

The Rpp2 protein is physically associated with both RNase P and RNase MRP enzymatic activities and affects both ptRNA and prRNA processing in vivo. This strongly indicates that Rpp2 is a component that is shared between RNase P and RNase MRP particles in vivo. It is also found in a complex with the Rpp1 protein, the yeast orthologue of the human scleroderma autoimmune antigen Rpp30. These findings further support the hypothesis that the two RNases are evolutionarily related. Which proteins contribute to the respective essential catalytic mechanisms of these enzymatic activities remains unknown. The relative contribution of these proteins to the RNase P and RNase MRP activities remains to be determined by biochemical fractionation and reconstitution of the separate enzymatic activities. By contrast, bacterial RNase P requires only a single protein component for its activity (1). Additional protein components of RNase P and RNase MRP that have been identified genetically in yeast (Pop1 and Pop3) show similar conditional defects in ptRNA and prRNA processing in vivo (11, 13).

As observed in other conditional mutants of RNase P and RNase MRP, the depletion of Rpp2 in vivo has a characteristic RNA-processing phenotype (11–14). Interestingly, these mutant yeast strains accumulate not only 5′ terminal ptRNAs, as would be expected for a RNase P-defective phenotype, but also accumulate 3′ extended and intron-containing forms of ptRNA and are deficient in processing of the 5.8S prRNA. What is the biochemical defect that accounts for the accumulation of both 5′ and 3′ extended forms of these RNAs? Recent findings suggest that yeast RNase MRP may collaborate with a 5′ to 3′ exonuclease, Xrn1, in processing of rRNA intermediates and, perhaps, mRNAs (32). Inhibition of this collaboration by an accumulation of a metabolite called adenosine 3′, 5′-bisphosphate (pAp) may result in lethality (32). Additional defects in prRNA modification, such as pseudouridynilation and/or methylation, may also account for the impaired processing of the 35S prRNA on depletion of the protein components of RNase P and RNase MRP. Such defects would result from direct and/or indirect effects of RNase P or RNase MRP in snRNA processing. Whether such functions of RNase P exist in cells remains unknown.

None of the human or yeast protein subunits of RNase P exhibits significant sequence similarities to any predicted ORFs from eubacterial or archaeal genomes (data not shown). Unlike the RNA component, the protein subunits of eukaryotic RNase P do not appear to share common ancestry with any eubacterial or archaeal sequences.

Acknowledgments

We thank Samara Reck-Peterson and Yves Barral for reagents and helpful advice. V.S. was supported by a predoctoral training grant in cell biology from the U.S. Public Health Service to Yale University. Research in the laboratory of S.A. was funded by Grant GM-19422 from the U.S. Public Health Service.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Rpp2

RNase P protein 2

- ptRNA

precursor tRNA

- prRNA

precursor rRNA, RNase MRP, RNase mitochondrial RNA processing

- ITS

internal transcribed sequences

Footnotes

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AF055991).

References

- 1.Altman S, Kirsebom L, Talbot S. In: tRNA: Structure Biosynthesis and Function. Soll D, RajBhandary U L, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1995. pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darr S C, Brown J W, Pace N R. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:178–82. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerrier-Takada C, Gardiner K, Marsh T, Pace N, Altman S. Cell. 1983;35:849–857. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu F, Altman S. Cell. 1994;77:1093–1100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gopalan V, Baxevanis A D, Landsman D, Altman S. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:818–829. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biartkiewicz M, Gold H, Altman S. Genes Dev. 1989;3:488–499. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J Y, Engelke D R. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2536–2543. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.6.2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J Y, Rohlman C E, Molony L A, Engelke D R. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:721–730. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haas E S, Armbruster D W, Vucson B M, Daniels C J, Brown J W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1252–1259. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.7.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eder P S, Kekuda R, Stolc V, Altman S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1101–1106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lygerou Z, Mitchell P, Petfalski E, Seraphin B, Tollervey D. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1423–1433. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.12.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu S, Zengel J M, Lindahl L. RNA. 1997;3:382–391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dichtl B, Tollervey D. EMBO J. 1997;16:417–429. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stolc V, Altman S. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2414–2425. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmitt M E, Clayton D A. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1975–1985. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmitt M E, Clayton D A. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7935–7941. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clayton D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4615–4617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chamberlain J R, Tranguch A J, Pagan-Ramos E, Engelke D R. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1996;55:87–119. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forster A C, Altman S. Cell. 1990;62:407–409. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90003-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrissey J P, Tollervey D. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:78–82. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88962-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lygerou Z, Allmang C, Tollervey D, Seraphin B. Science. 1996;272:268–270. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang D D, Clayton D A. Cell. 1987;56:131–139. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90991-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stohl L L, Clayton D A. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2561–2569. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chamberlain J R, Pagan-Ramos E, Kindelberger D W, Engelke D R. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3158–3166. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.16.3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarrous N, Eder P S, Guerrier-Takada C, Hoog C, Altman S. RNA. 1998;4:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cherry J M, Adler C, Ball C, Chervitz S A, Dwight S S, Hester E T, Jia Y, Juvik G, Roe T, Schroeder M, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:73–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venema J, Tollervey D. EMBO J. 1996;15:5701–5714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drainas D, Zimmerly S, Willis I, Soll D. FEBS Lett. 1989;251:84–88. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry Y, Wood H, Morrissey J P, Petfalski E, Kearsey S, Tollervey D. EMBO J. 1994;13:2452–2463. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell P, Petfalski E, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Tollervey D. Cell. 1997;91:457–466. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dichtl B, Stevens A, Tollervey D. EMBO J. 1997;16:7184–7195. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guthrie C, Fink G R. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:539. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94058-k. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]