Abstract

Mutations in the gene autoimmune regulator (AIRE) cause autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy. AIRE is expressed in thymic medullary epithelial cells, where it promotes the expression of tissue-restricted antigens. By the combined use of biochemical and biophysical methods, we show that AIRE selectively interacts with histone H3 through its first plant homeodomain (PHD) finger (AIRE–PHD1) and preferentially binds to non-methylated H3K4 (H3K4me0). Accordingly, in vivo AIRE binds to and activates promoters containing low levels of H3K4me3 in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. We conclude that AIRE–PHD1 is an important member of a newly identified class of PHD fingers that specifically recognize H3K4me0, thus providing a new link between the status of histone modifications and the regulation of tissue-restricted antigen expression in thymus.

Keywords: AIRE, negative selection, NMR, protein structure

Introduction

Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) is a monogenic autosomal recessive syndrome characterized by a breakdown of self-tolerance, leading to autoimmune reactions in several organs and providing a useful model for molecular studies of autoimmunity (Mathis & Benoist, 2007). The disease is caused by mutations in autoimmune regulator (AIRE; Fig 1A), a transcriptional activator (Nagamine et al, 1997). AIRE promotes the thymic expression of many tissue-restricted antigens, enabling the negative selection of developing T cells and thus precluding self-reactivity (Anderson et al, 2002; Liston et al, 2003); however, the mechanisms are so far unknown. AIRE controls genes in genomic clusters, indicating a role in epigenetic regulation (Derbinski et al, 2005). Indeed, AIRE contains two plant homeodomain (PHD) fingers—small zinc-binding domains often found in chromatin-associated proteins (Aasland et al, 1995; Bienz, 2006). The PHD finger has emerged as a module that transduces histone-lysine methylation events. In particular, BPTF, ING2 and RAG2 PHD fingers recognize histone H3 trimethylated at lysine (K) 4 (H3K4me3; Li et al, 2006; Pena et al, 2006; Shi et al, 2006; Wysocka et al, 2006; Matthews et al, 2007), whereas the SMCX PHD finger binds to H3K9me3 (Iwase et al, 2007).

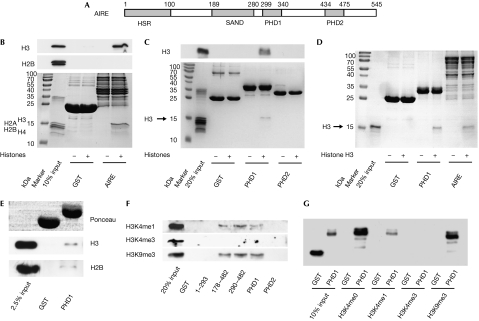

Figure 1.

AIRE interacts with H3K4me0 by means of AIRE–PHD1. (A) A schematic representation of the AIRE protein. Grey boxes represent HSR (homogenously staining region), PHD (plant homeodomain) and SAND (Sp100, AIRE-1, NucP41/P75 and Drosophila DEAF-1). (B) GST-AIRE interaction with whole histones visualized by Coomassie staining (bottom), and detected by western blot using anti-H3 and anti-H2B (top and middle). (C) A similar experiment to (B) but using GST-PHD proteins, detected by western blot using anti-H3 (top) or Coomassie staining (bottom). (D) GST-PHD1 and GST-AIRE, but not GST alone, interact with purified recombinant histone H3, visualized by Coomassie staining. (E) GST-PHD1, but not GST alone, interacts with native mononucleosomes detected by western blot against anti-H3 (middle) and anti-H2B (bottom). Equal input of GST proteins is shown with Ponceau red staining (top). (F) Interaction between GST-AIRE fusion proteins and whole histones, detected by anti-H3K4me1, anti-H3K4me3 and anti-H3K9me3. (G) Interaction between GST-AIRE–PHD1 fusion proteins and amino-terminal histone H3 peptides (H3K4me0, H3K4me1, H3K4me3 and H3K9me3), all detected by anti-GST. AIRE, autoimmune regulator; GST, glutathione-S-transferase.

Here, we show that AIRE binds to histone H3 through its first PHD finger (AIRE–PHD1). In contrast with BPTF, ING2 and RAG2, AIRE–PHD1 preferentially binds to histone H3 non-methylated at lysine 4 (H3K4me0). Our results, in agreement with recent studies of the DNMT3L and BHC80 PHD fingers (Lan et al, 2007; Ooi et al, 2007), show a new role for the PHD finger as an H3K4me0 reader.

Results And Discussion

AIRE–PHD1 binds to histone H3

To investigate the role of AIRE in chromatin-regulating complexes, we examined whether AIRE interacts with histones. Indeed, when incubated with whole histones, glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-AIRE (full-length) interacted with a histone that was identified as H3 by western blotting (Fig 1B). By using various GST fusions, we found that AIRE–PHD1 is necessary and sufficient to interact with histone H3 (Fig 1C; supplementary Fig S1A,B online). Furthermore, the interaction is direct, as both full-length AIRE and AIRE–PHD1 bound to recombinant purified H3 (Fig 1D) but not to H2B (supplementary Fig S1C online). AIRE–PHD1 has a zinc-dependent fold and, accordingly, H3 binding is greatly reduced by EDTA or mutation of zinc-chelating cysteines, including the pathological mutation C311Y (Bjorses et al, 2000; supplementary Fig S1D–F online). AIRE–PHD1 also interacted with a small fraction of native mononucleosomes, as assessed by western blot against H3 and H2B (Fig 1E), and by analysing bound DNA (supplementary Fig S1G online). Thus, AIRE interacts, by means of its first PHD finger, specifically with histone H3 in both isolated and nucleosomal contexts.

AIRE–PHD1 preferentially binds to H3K4me0

Western blot analysis of H3/AIRE–PHD1 complex formation by using antibodies for H3K4me1, H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 indicated that H3K4 trimethylation hinders interaction (Fig 1F), whereas H3K9 trimethylation does not. Binding experiments with amino-terminal histone H3 unmodified (H3K4me0) or modified (H3K4me1, H3K4me3 and H3K9me3) 20-mer peptides showed that these N-terminal residues of histone H3 are sufficient for binding to AIRE–PHD1 (Fig 1G). Although both H3K4me0 and H3K9me3 peptides bound to AIRE–PHD1 with similar affinities, binding decreased with increasing H3K4 methylation (Fig 1G), indicating that AIRE–PHD1 preferentially binds to H3K4me0.

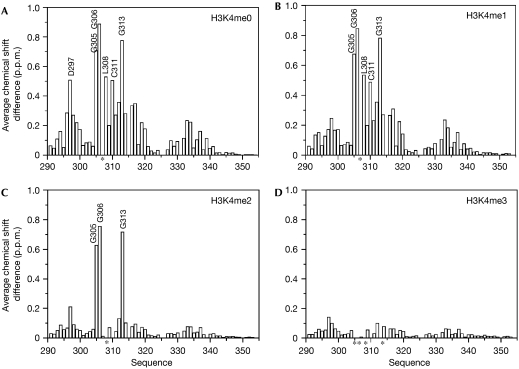

To confirm the specificity of AIRE–PHD1 for H3K4me0, we compared the binding of histone H3 N-terminal peptides—H3K4me0, H3K4me1, H3K4me2 and H3K4me3—to AIRE–PHD1 by using two dimensional 1H-15N nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). A discrete set of chemical shift changes was observed on addition of all four histone H3 peptides to AIRE–PHD1 (supplementary Fig S2A,B online). However, the intensity of the changes was inversely related to the methylation level of the H3 peptide: the H3K4me0 peptide induced the largest changes (maximum average chemical shift change Δδmaxav=0.9 p.p.m.; Fig 2). The addition of H3K4me0 and H3K4me1 peptides resulted in chemical shift changes in the slow- to intermediate-exchange regime (supplementary Fig S2A online), indicating low micromolar binding affinities. By contrast, the NMR data on addition of H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 peptides were in the fast-exchange regime, indicating millimolar binding affinities (supplementary Fig S2B online).

Figure 2.

Distribution of the backbone amide chemical shift changes within AIRE–PHD1 on binding to H3 amino-terminal peptides. Histograms showing the average backbone chemical shift differences observed in the 15N-labelled AIRE–PHD1 (0.2 mM) on addition of a twofold excess of (A) H3K4me0, (B) H3K4me1, (C) H3K4me2 and (D) H3K4me3; the average chemical shift differences decrease with the methylation level of H3K4. Asterisks indicate residues for which the backbone amide signals disappear during titration owing to line broadening. AIRE, autoimmune regulator; H3K4me0, histone H3 non-methylated at lysine 4; H3K4me1 (H3K4me2, H3K4me3), histone H3 monomethylated (respectively, dimethylated and trimethylated) at lysine 4; PHD, plant homeodomain.

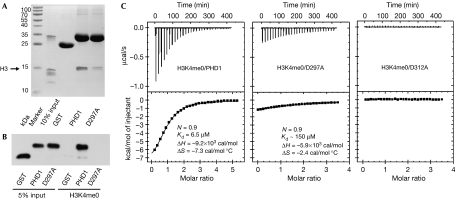

The greater binding affinity of AIRE–PHD1 for H3K4me0 peptides was confirmed by both tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), yielding dissociation constants of ∼4 μM, ∼20 μM and >0.5 mM for H3K4me0, H3K4me1 and H3K4me2, respectively (supplementary Fig S2C online; Table 1). Notably, H3K4me3 did not show any significant interaction with AIRE–PHD1 in either binding assay.

Table 1.

Values of the dissociation constants between H3 peptides and AIRE–PHD1 wild type (WT) and mutants measured by fluorescence spectroscopy and isothermal titration calorimetry

| AIRE–PHD1 | Peptide | KD (μM), fluorescence spectroscopy | KD (μM), isothermal titration calorimetry |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | H3K4me0 | 4.7±0.8 | 6.5±0.2 |

| WT | H3K4me1 | 21.4±5.9 | 55.6±1.2 |

| WT | H3K4me2 | >500 | 714±90 |

| WT | H3K4me3 | ND | NM |

| V301M | H3K4me0 | 6.8±0.4 | NM |

| C311Y | H3K4me0 | ND | NM |

| D297A | H3K4me0 | 173.0±18.6 | 146.8±6.1 |

| D312A | H3K4me0 | ND | ND |

| WT | H3K4me0-R2A | ND | NM |

| D297A | H3K4me3 | ND | NM |

| ND, not detectable, denotes binding too weak to be reliably quantified; NM, not measured. | |||

In agreement with the GST fusion pull-down experiments, fluorescence spectroscopy showed no binding of H3K4me0 to AIRE–PHD1 containing the APECED-causing C311Y mutation (Bjorses et al, 2000). Nevertheless, a second pathological mutant, V301M (Soderbergh et al, 2000), was still able to bind to H3K4me0, indicating that this mutation is not located in the H3 interaction site (Table 1).

The mapping of the H3/AIRE interaction site uniquely to AIRE–PHD1 was further confirmed by NMR titrations of histone H3 peptides into AIRE–PHD2, which bound neither methylated nor H3K4me0 peptides (data not shown).

Model of AIRE–PHD1 and histone H3 interactions

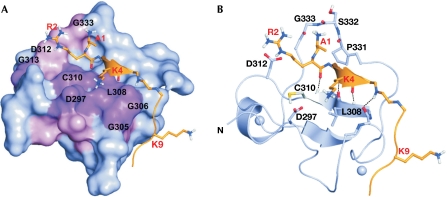

We generated a model of AIRE–PHD1 complexed with the H3K4me0 peptide on the basis of the crystal structure of the BPTF–PHD finger bound to H3K4me3 and performed molecular dynamics calculations for 10 ns. During the simulations, the peptide interacted stably with the first β-strand of AIRE–PHD1, creating a third antiparallel β-strand (Fig 3). The additional β-strand allowed the formation of four hydrogen (H) bonds from the backbone of H3 residues R2, K4 and T6 to the AIRE–PHD1 residues C310, L308 and G306, respectively (Fig 3B). Accordingly, the amides of C310, L308 and G306 showed high protection factors in NMR deuterium exchange experiments, confirming their involvement in H-bonds (Fig 3B). The N terminus of the peptide was anchored through intermolecular H-bonds with the backbone carbonyl oxygen atoms of residues P331–G333 (Fig 3B). Furthermore, hydrophobic interactions between the methyl group of A1 and the pyrrolidine ring of P331, and between the methylene groups of K4 and L308 further contributed to the stabilization of the complex. The formation of salt bridges between the side chains of R2 and D312, and between K4 and D297 seemed to be crucial for binding specificity, as indicated experimentally by the large NMR chemical shift changes for G313 (near to D312) and D297 (Fig 2). Indeed, fluorescence spectroscopy and ITC assays showed that the alanine mutations R2A in the H3 peptide and D312A in AIRE–PHD1 markedly reduced the binding affinity (Table 1; Fig 4C) without affecting the protein fold (supplementary Fig S3 online). Similarly, pull-down experiments with whole histones and the H3K4me0 peptide, together with fluorescence spectroscopy and ITC measurements performed on AIRE–PHD1-D297A showed reduced binding (Table 1; Fig 4). Furthermore, no binding was observed in fluorescence spectroscopy and ITC experiments when H3K4me3 was titrated into AIRE–PHD1-D297A (Table 1). Importantly, simulations of AIRE–PHD1 with H3K4me1 or H3K4me3 were not compatible with complex formation, showing displacement of K4 owing to steric clashes with D297, with the consequent breakage of the additional β-strand (supplementary Fig S4 online).

Figure 3.

Model of AIRE–PHD1 in complex with H3K4me0. (A) Surface representation of AIRE–PHD1 in complex with H3K4me0. Residues with the highest chemical shifts are shown in magenta (Δδ>0.4 p.p.m.) and pink (0.2<Δδ<0.4 p.p.m.). (B) Ribbon representation of a representative structure of the complex of AIRE1–PHD1 (blue) with H3K4me0 (orange). Inter-backbone hydrogen bonds and Zn2+ ions are represented by dotted lines and spheres, respectively. AIRE, autoimmune regulator; H3K4me0, histone H3 non-methylated at lysine 4; PHD, plant homeodomain.

Figure 4.

Mutations of D297 and D312 abolish AIRE–PHD1 binding to histone H3. (A) Pull-down assay of AIRE–PHD1 (PHD1) and AIRE–PHD1-D297A (D297A) mutant proteins with histones. (B) Interaction between AIRE–PHD1 (PHD1), AIRE–PHD1-D297A (D297A) mutant proteins and H3K4me0 peptide detected by anti-GST. (C) ITC data for binding of H3K4me0 peptide to AIRE–PHD1 (PHD1), AIRE–PHD1-D297A (D297A) and AIRE–PHD1-D312A (D312A). The upper panels show the sequential heat pulses for peptide–protein binding, and the lower panels show the integrated data, corrected for heat of dilution and fit to a single-site-binding model using a nonlinear least-squares method (line). N, Kd, ΔH and ΔS represent measured stoichiometric ratio, dissociation binding constant, differential enthalpy and differential entropy, respectively. AIRE, autoimmune regulator; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; H3K4me0, histone H3 non-methylated at lysine 4; ITC, isothermal titration calorimetry; PHD, plant homeodomain.

Nature of the binding interface

The model of AIRE–PHD1 complexed with H3K4me0 was in perfect agreement with the experimental chemical shift perturbation data, as the peptide-binding region coincided with the binding surface identified by NMR spectroscopy (Fig 3A). In fact, the H3K4me0 peptide induced chemical shift changes in AIRE–PHD1 residues that map only on one side of the protein surface, involving residues in the N terminus of the PHD finger, the first β-strand, and the loop connecting the first and the second β-strands (D297, G305, G306, L308, C310, D312 and G313; Fig 2; supplementary Fig S5 online). A similar pattern of chemical shift changes indicated the same binding site for H3K4me1. However, H3K4me1 induced smaller changes for residues E296–A300, indicating that binding to this region is reduced by K4 methylation (Fig 2B).

H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 also induced similar patterns of chemical shift changes, indicating a similar interaction site with AIRE–PHD1. However, the changes were markedly reduced in size, in keeping with a weak interaction (Fig 2C,D). Remarkably, residues G305, G306 and G313 showed strong shifts when bound to H3K4me2 and disappeared completely from the NMR spectrum owing to line-shape broadening on binding to H3K4me3, indicating an involvement of this region in peptide binding.

Structural comparison with other PHD fingers

Our data suggest a regulatory mechanism mediated by AIRE–PHD1 that differs from that of ING2 and BTPF, the PHD fingers of which bind to H3K4me3 and discriminate against H3K4me0. A structural based sequence alignment (supplementary Fig S6 online) suggests that AIRE–PHD1 is representative of a newly identified subclass of PHD fingers (Lan et al, 2007). AIRE–PHD1 differs structurally from the ING2 and BPTF PHD fingers owing to the lack of conserved aromatic residues used to coordinate the trimethyl ammonium ion of H3K4me3 by π-cation interactions. Instead, the crucial elements of the methylated lysine-binding aromatic cage seen in ING2 and BPTF (supplementary Fig S6 online) are substituted by negatively charged (D297) and small hydrophobic (A317) residues in AIRE–PHD1. Our data show that D297 is involved in the interaction of AIRE with H3K4me0, providing an alternative to the recognition of histone H3 by aromatic caging. Notably, D297 is conserved in other PHD finger proteins, for example, Sp110 and Sp140, which might constitute a subset of H3K4me0 readers (supplementary Fig S6 online). Recently, the PHD finger of BHC80 and the cysteine-rich domain of DNMT3L were shown to recognize H3K4me0 by an analogous mechanism, in which the H3 peptide binds to the surface of the domain, forming an additional β-strand that is anchored by the side chain and N-amine group of H3A1. Importantly, these proteins also have an acidic residue comparable to D297, which forms a salt bridge with K4. Although there are many similarities between these two structures and the AIRE–PHD1/H3K4me0 complex presented here, the AIRE–PHD1 finger differs in the additional recognition of the H3R2 side chain, which makes an important contribution to the high affinity of this interaction, as shown by our peptide mutagenesis experiments.

AIRE interacts with chromatin

We have shown previously that transiently transfected AIRE enhances target gene expression in human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells (Pitkanen et al, 2005). So far, no cell line has been described with endogenous AIRE expression; therefore, we transfected HEK293 cells with an AIRE-encoding or control plasmid and generated stable cell lines called HEK-AIRE and HEK-control. We first tested HEK-AIRE compared with HEK-control cell lines for expression levels of tissue-restricted antigens that are downregulated in AIRE-deficient mouse thymic medullary epithelial cells (Derbinski et al, 2005). Indeed, the HEK-AIRE cell line showed enhanced expression of such antigens, including insulin, the principal autoantigen in type I diabetes (Babaya et al, 2005), involucrin and S100A8 (Fig 5A). The last two genes are AIRE target genes clustered on human chromosome 1q21 (Marenholz et al, 2001). Conversely, the expression levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and that of another S100 family protein, S100A10, were unaffected by AIRE (Fig 5A). Next, we studied in vivo histone binding by protein chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays and observed that AIRE is found in complexes with a small fraction of histone H3 but not with H3K4me3. By contrast, binding of ING2, used as a positive control, was detected for both H3 and H3K4me3 (supplementary Fig S7 online). By using DNA ChIP analysis, we found that AIRE interacts with the insulin, involucrin and S100A8 promoter regions, but much less with the S100A10 and GAPDH promoters (Fig 5B). In agreement with the low expression levels observed, the insulin, involucrin and S100A8 promoters almost completely lacked H3K4me3, whereas the highly expressed S100A10 and GAPDH promoters were enriched with H3K4me3 (Fig 5C). The overall levels of histone H3 were comparable on all promoters studied (Fig 5D). To analyse the influence of AIRE–PHD1 mutations that impaired the interaction with H3 in vitro, we generated stable cell lines expressing AIRE with PHD1 mutations D297A and D312A. Importantly, the activation of the AIRE target genes (Fig 6A), as well as binding to their promoters (Fig 6B), was clearly reduced by both mutations. Although AIRE specificity towards chromatin might be influenced by other protein and DNA interactions (Ruan et al, 2007), the data presented here indicate that AIRE preferentially binds to and activates the promoters containing low levels of H3K4me3. On the basis of these results, we propose a speculative model for the regulation of tissue-restricted antigen expression in thymic epithelial cells (supplementary Fig S8 online). Normally, tissue-restricted antigens are silenced in immature thymic epithelial cells as they lack the active chromatin mark H3K4me3 on their promoters. During differentiation into mature thymic medullary epithelial cells, activation of AIRE expression (Kyewski & Klein, 2006) enables the read-out of non-methylated H3K4 as a signal to activate tissue-restricted antigen genes. AIRE binding to the non-methylated H3K4 on tissue-restricted antigen promoters results in recruitment of other transcriptional regulators, for example, CBP (Pitkanen et al, 2005) and activation of transcription.

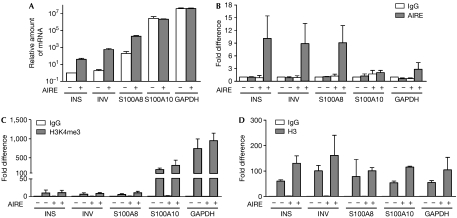

Figure 5.

AIRE binds to chromatin as a transcriptional activator. (A) Relative expression levels of insulin (INS), involucrin (INV), S100A8, S100A10 and GAPDH genes in HEK-AIRE (+) and HEK-control (−) cell lines are shown in logarithmic scale and in comparison with the insulin messenger RNA level in HEK-control cell line (=1). DNA ChIP with (B) anti-AIRE, (C) anti-H3K4me3 and (D) anti-H3. The fold differences are normalized to input fractions and shown in comparison with the background level (ChIP with IgG from HEK-control cells (=1)) of each primer set. The data are the averages of two or more independent experiments. AIRE, autoimmune regulator; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HEK, human embryonic kidney; H3K4me3, histone H3 trimethylated at lysine 4.

Figure 6.

Influence of the AIRE–PHD1 mutations on transcriptional activation and chromatin binding. (A) Relative expression levels of insulin (INS), involucrin (INV) and S100A8 genes in HEK-AIRE (AIRE), HEK-AIRE-D297A (D297A) and HEK-AIRE-D312A (D312A) mutant and HEK-control (YFP) cell lines are shown in comparison with the messenger RNA levels in HEK-AIRE cell lines (=100%). (B) DNA ChIP analysis with anti-AIRE and IgG was performed from the stably transfected cells, as indicated. The fold differences are normalized to input fractions and shown in comparison with the background level (=1) with each primer set in each condition. The data are the averages of two independent experiments. AIRE, autoimmune regulator; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; HEK, human embryonic kidney; PHD, plant homeodomain.

Our results provide new information on the role of AIRE in sensing epigenetic chromatin modifications through direct binding of AIRE–PHD1 to histone H3 N-terminal residues. Collectively, our data show that AIRE belongs to a new subset of PHD finger-containing proteins that preferentially recognize H3K4me0. Future studies should therefore explore the epigenetic role of AIRE in thymic expression of tissue-restricted antigens to advance further our understanding of this important regulator of autoimmunity.

Methods

Plasmid construction and in vitro binding assays. The construction of plasmids, information on antibodies and peptides used, as well as protein expression and binding assays are described in the supplementary information online.

NMR binding, fluorescence titration assays and isothermal titration calorimetry thermodynamic analysis. Details on NMR titrations, fluorescence spectroscopy and thermodynamic measurements are described in the supplementary information online.

Assembly of the complex structures and molecular dynamics calculations. The PHD finger structures from the human NURF BPTF PHD finger-H3K4me3 complex (2fuu) and AIRE1–PHD1 (1xwh) were superimposed by using the Lsqman program (Cα atom RMSD: 2.1 Å). Molecular dynamics simulations and analysis were performed using the GROMACS 3.1.3 package with GROMOS force field. The details of the protocol are available in the supplementary information online.

Cell lines, expression analysis and chromatin immunoprecipitation. The establishment of HEK-AIRE and HEK-control cell lines is described in the supplementary information online. DNA ChIP was performed essentially according to Upstate Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay protocol. Quantitative PCR analysis and primer sequences are provided in the supplementary information online.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

supplementary Figs S1–S8

Acknowledgments

T.O., A.R., I.L. and P.P. were supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust and European Union Framework programme 6 (Thymaide and Euraps), and from the Estonian Science Foundation (6663 and 6490). We acknowledge A. Häling for technical help. G.M. acknowledges support from Fondazione Telethon, Fondazione Cariplo and Compagnia S. Paolo, and thanks M. Bianchi and D. Gabellini for useful discussions. C.H. and U.M. thank the Foundation Innove (www.innove.ee) project no. 1.0101-0310 for financial support.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aasland R, Gibson TJ, Stewart AF (1995) The PHD finger: implications for chromatin-mediated transcriptional regulation. Trends Biochem Sci 20: 56–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MS et al. (2002) Projection of an immunological self shadow within the thymus by the aire protein. Science 298: 1395–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babaya N, Nakayama M, Eisenbarth GS (2005) The stages of type 1A diabetes. Ann NY Acad Sci 1051: 194–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienz M (2006) The PHD finger, a nuclear protein-interaction domain. Trends Biochem Sci 31: 35–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorses P, Halonen M, Palvimo JJ, Kolmer M, Aaltonen J, Ellonen P, Perheentupa J, Ulmanen I, Peltonen L (2000) Mutations in the AIRE gene: effects on subcellular location and transactivation function of the autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy protein. Am J Hum Genet 66: 378–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbinski J, Gabler J, Brors B, Tierling S, Jonnakuty S, Hergenhahn M, Peltonen L, Walter J, Kyewski B (2005) Promiscuous gene expression in thymic epithelial cells is regulated at multiple levels. J Exp Med 202: 33–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase S, Lan F, Bayliss P, de la Torre-Ubieta L, Huarte M, Heng Qi H, Whetstine JR, Bonni A, Roberts TM, Shi Y (2007) The X-linked mental retardation gene SMCX/JARID1C defines a family of histone H3 lysine 4 demethylases. Cell 128: 1077–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyewski B, Klein L (2006) A central role for central tolerance. Annu Rev Immunol 24: 571–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan F, Collins RE, De Cegli R, Alpatov R, Horton JR, Shi X, Gozani O, Cheng X, Shi Y (2007) Recognition of unmethylated histone H3 lysine 4 links BHC80 to LSD1-mediated gene repression. Nature 448: 718–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Ilin S, Wang W, Duncan EM, Wysocka J, Allis CD, Patel DJ (2006) Molecular basis for site-specific read-out of histone H3K4me3 by the BPTF PHD finger of NURF. Nature 442: 91–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston A, Lesage S, Wilson J, Peltonen L, Goodnow CC (2003) Aire regulates negative selection of organ-specific T cells. Nat Immunol 4: 350–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marenholz I, Zirra M, Fischer DF, Backendorf C, Ziegler A, Mischke D (2001) Identification of human epidermal differentiation complex (EDC)-encoded genes by subtractive hybridization of entire YACs to a gridded keratinocyte cDNA library. Genome Res 11: 341–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis D, Benoist C (2007) A decade of AIRE. Nat Rev Immunol 7: 645–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AG et al. (2007) RAG2 PHD finger couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with V(D)J recombination. Nature 450: 1106–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamine K et al. (1997) Positional cloning of the APECED gene. Nat Genet 17: 393–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi SK et al. (2007) DNMT3L connects unmethylated lysine 4 of histone H3 to de novo methylation of DNA. Nature 448: 714–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena PV, Davrazou F, Shi X, Walter KL, Verkhusha VV, Gozani O, Zhao R, Kutateladze TG (2006) Molecular mechanism of histone H3K4me3 recognition by plant homeodomain of ING2. Nature 442: 100–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen J et al. (2005) Cooperative activation of transcription by autoimmune regulator AIRE and CBP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 333: 944–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan QG et al. (2007) The autoimmune regulator directly controls the expression of genes critical for thymic epithelial function. J Immunol 178: 7173–7180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X et al. (2006) ING2 PHD domain links histone H3 lysine 4 methylation to active gene repression. Nature 442: 96–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderbergh A, Rorsman F, Halonen M, Ekwall O, Bjorses P, Kampe O, Husebye ES (2000) Autoantibodies against aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase identifies a subgroup of patients with Addison's disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 460–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocka J et al. (2006) A PHD finger of NURF couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with chromatin remodelling. Nature 442: 86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

supplementary Figs S1–S8