Abstract

The p27Kip1 ubiquitin ligase receptor Skp2 is often overexpressed in human tumours and displays oncogenic properties. The activity of SCFSkp2 is regulated by the APCCdh1, which targets Skp2 for degradation. Here we show that Skp2 phosphorylation on Ser64/Ser72 positively regulates its function in vivo. Phosphorylation of Ser64, and to a lesser extent Ser72, stabilizes Skp2 by interfering with its association with Cdh1, without affecting intrinsic ligase activity. Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)2-mediated phosphorylation of Skp2 on Ser64 allows its expression in mid-G1 phase, even in the presence of active APCCdh1. Reciprocally, dephosphorylation of Skp2 by the mitotic phosphatase Cdc14B at the M → G1 transition promotes its degradation by APCCdh1. Importantly, lowering the levels of Cdc14B accelerates cell cycle progression from mitosis to S phase in an Skp2-dependent manner, demonstrating epistatic relationship of Cdc14B and Skp2 in the regulation of G1 length. Thus, our results reveal that reversible phosphorylation plays a key role in the timing of Skp2 expression in the cell cycle.

Keywords: APC, cell cycle, p27Kip1, protein phosphorylation, ubiquitin–proteasome pathway

Introduction

Progression through the eukaryotic cell cycle is controlled by oscillating waves of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity (Murray, 2004). These kinases are regulated positively by association with cyclin regulatory subunits and negatively by binding to CDK inhibitors (Sherr and Roberts, 1999). The ubiquitin–proteasome system plays a key role in maintaining the timing of CDK activation by promoting the periodic degradation of cyclins and CDK inhibitors (Reed, 2003; Nakayama and Nakayama, 2006). The two main classes of ubiquitin ligases (E3s) involved in cell cycle control are the anaphase-promoting complex (APC) and the SCF (Skp1–Cul1–F-box) complexes. The APC is a multisubunit E3 that is active from early mitosis to the next S phase and is required for mitosis progression and G1 maintenance (Peters, 2006). Substrate recognition by the APC is mediated by the activating subunits Cdc20 and Cdh1. The APCCdc20 is activated in prometaphase by CDK1 phosphorylation to trigger the degradation of mitotic cyclins and securin. In anaphase, APCCdh1 becomes activated and mediates the degradation of Cdc20 and S-phase-promoting factors to coordinate mitotic exit with G1 progression.

The SCF complex is another multisubunit E3 involved in the regulation of cell cycle progression (Cardozo and Pagano, 2004; Nakayama and Nakayama, 2006). SCF ligases interact with their substrates via modular F-box proteins, which consist of the Skp1-interacting F-box domain and a variable substrate-binding domain. Contrary to the APC, substrate targeting by F-box proteins is generally dependent on activation of the substrate by post-translational modifications. Among SCF complexes, the SCFSkp2 ligase plays a key role in cell cycle progression by targeting negative regulators of the cell cycle such as p27Kip1 (p27) (Carrano et al, 1999; Sutterluty et al, 1999; Tsvetkov et al, 1999), p21 (Bornstein et al, 2003) and p130 (Tedesco et al, 2002) for degradation. As a consequence, SCFSkp2 favours progression of cells into S phase and mitosis. Genetic studies in mice indicate that p27 is the main target of Skp2. The small body size and over-replication defects associated with disruption of Skp2 are rescued by concomitant inactivation of p27 (Kossatz et al, 2004; Nakayama et al, 2004).

In addition to substrate modification, the activity of SCFSkp2 in the cell cycle is regulated at the level of F-box protein expression. Skp2 protein levels are low in G0/early G1 and increase gradually as cells move to S phase to persist until mitosis (Wirbelauer et al, 2000; Bashir et al, 2004; Wei et al, 2004; Rodier et al, 2005). These changes in Skp2 levels result in large part from differences in protein stability. An important insight into the understanding of Skp2 regulation came with the finding that APCCdh1 targets Skp2 for degradation in G1 phase, thereby preventing premature entry into S phase (Bashir et al, 2004; Wei et al, 2004). This observation highlighted the tight interplay that exists between APC and SCF complexes in cell cycle control. Skp2 is upregulated in many human cancers and its expression inversely correlates with the levels of p27 (Yamasaki and Pagano, 2004; Nakayama and Nakayama, 2006). This underscores the importance of elucidating the mechanisms that control Skp2 abundance in normal and cancer cells.

Although less well studied, protein phosphatases are also predicted to play an important role in cell cycle transitions. The Cdc14 phosphatase functions in different cell cycle events, although its requirements vary from one species to another (Trinkle-Mulcahy and Lamond, 2006). In budding yeast, Cdc14 is absolutely required for mitotic exit and also participates in cytokinesis (Stegmeier and Amon, 2004). The mitotic functions of Cdc14 are associated with its ability to reverse CDK-dependent phosphorylation events. In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, Cdc14 plays a unique role in maintaining G1 arrest of specific precursor cells during larval development (Saito et al, 2004). Genetic analyses suggest that Cdc14 functions upstream of the CDK inhibitor CKI-1 in this process. Mammalian cells express two Cdc14 homologues (Li et al, 2000), termed Cdc14A and Cdc14B, whose specific substrates and functions are poorly understood. Deregulated expression of Cdc14A impairs the centrosome duplication cycle and causes aberrant chromosome partitioning (Mailand et al, 2002). Cdc14B was suggested to play a role in spindle dynamics by promoting microtubules bundling by a catalytically independent mechanism (Cho et al, 2005).

Here, we show that phosphorylation of Skp2 stabilizes the protein by interfering with its recognition and degradation by APCCdh1. The phosphorylation of Skp2 is catalysed in part by the CDK2 and CDK1 cell cycle kinases, and is reversed by Cdc14B during M to G1 transition. Importantly, we find that Cdc14B regulates G1-phase length in an Skp2-dependent manner.

Results

Skp2 is phosphorylated on Ser64 and Ser72 in vivo

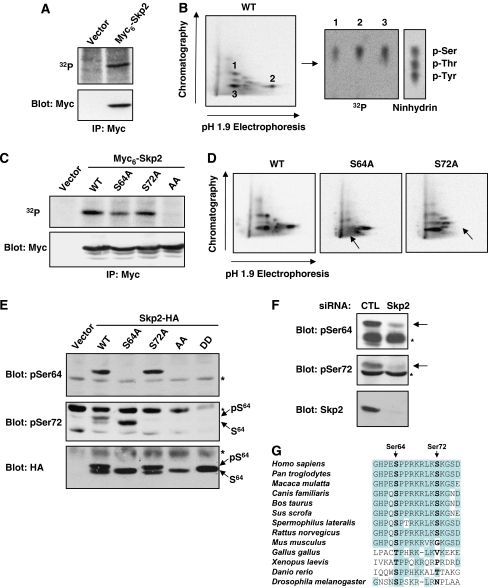

To further understand the regulation of Skp2 activity in the cell cycle, we examined the phosphorylation status of Skp2 in proliferating cells. Metabolic labelling experiments showed that ectopically expressed Myc6-Skp2 is a phosphoprotein in vivo (Figure 1A). Phosphopeptide mapping analysis revealed the presence of two major phosphopeptides (spots 2 and 3) and one peptide of variable intensity (spot 1) containing exclusively phospho-serine residues (Figure 1B). To identify these phosphorylation sites, we constructed a series of N-terminally truncated Skp2 mutants and assessed their in vivo phosphorylation state (Supplementary Figure 1A). A mutant of Skp2 lacking the first 99 amino acids (Skp2 ΔN100) was not phosphorylated in vivo, whereas Skp2 ΔN64 still incorporated labelled phosphate (Supplementary Figure 1B). The region encompassing residues 64–99 contains five serines. Mutation of Ser75, Ser96 or Ser99 to alanine did not affect significantly Skp2 phosphopeptide maps (Supplementary Figure 1C). By contrast, the maps of the S64A and S72A mutants lacked spots 3 and 2, respectively, indicating that these two residues are phosphorylated in intact cells (Figure 1D). No detectable phosphorylation of Skp2 could be observed upon mutation of both serine residues (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Skp2 is phosphorylated on Ser64 and Ser72 in vivo. (A) Rat1 cells transfected with Myc6-Skp2 were labelled with 32Pi. Skp2 was immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc and analysed by autoradiography (upper panel) and immunoblotting (lower panel). (B) Phosphopeptide mapping analysis of Myc6-Skp2 and phosphoamino-acid analysis of the main phosphopeptides. (C) In vivo phosphorylation of the indicated Myc6-Skp2 constructs expressed in Rat1 cells. (D) Phosphopeptide mapping analysis of Myc6-Skp2 wild-type, S64A and S72A. Arrows indicate the loss of phosphopeptides. (E) Rat1 cells were transfected with wild-type Skp2-HA and the indicated mutants. Cellular extracts were analysed by immunoblotting with Skp2 phospho-specific antibodies to Ser64 and Ser72. The higher molecular mass species corresponds to the Ser64-phosphorylated form of Skp2. * Marks nonspecific bands. (F) Cellular extracts of proliferating HeLa cells were analysed by immunoblotting with Skp2 phospho-specific antibodies. Specificity of antibodies was assessed by depletion of Skp2 using RNA interference. (G) Phylogenetic conservation of Skp2 phosphorylation sites.

To analyse the phosphorylation of the endogenous Skp2 protein, we generated phosphospecific antibodies to Ser64 and Ser72. Both antibodies recognized ectopic wild-type Skp2-HA, but not the relevant serine-to-alanine mutants (Figure 1E). As is often the case, the antibodies failed to react with phosphomimetic mutants. Note that overexpressed Skp2-HA migrates as two bands in Rat1, 293, NIH 3T3 and HeLa cells (Figures 1E, 3B and E and data not shown). The slower migrating band corresponds to the Ser64-phosphorylated form of Skp2. Ser72 phosphorylation does not alter the electrophoretic mobility of Skp2. The two antibodies also detected an endogenous ∼45 kDa protein in exponentially proliferating HeLa cells (Figure 1F). The immunoreactivity is lost when cells are depleted of Skp2 by RNA interference, confirming that endogenous Skp2 is phosphorylated on Ser64 and Ser72.

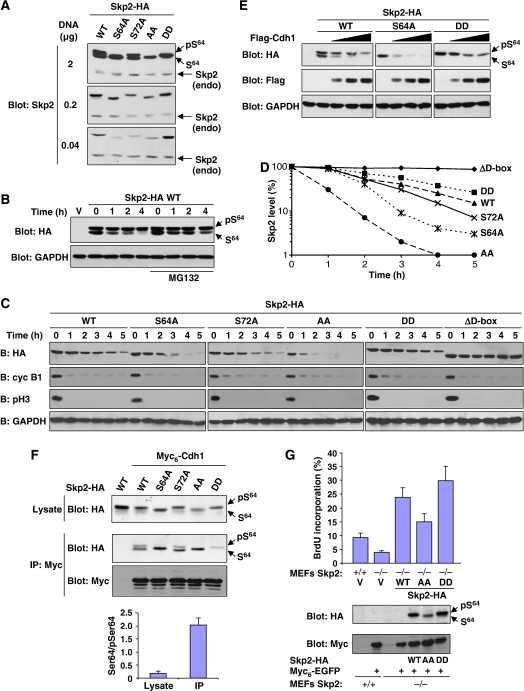

Figure 3.

Phosphorylation of Skp2 protects it from degradation by APCCdh1. (A) Rat1 cells were transfected with various amounts of DNA encoding wild-type Skp2-HA or the indicated mutants. Endogenous Skp2 and ectopic Skp2 were detected by anti-Skp2 immunoblotting. The position of the endogenous protein is indicated. (B) 293 cells were transfected with Skp2-HA. After 48 h, the cells were treated with cycloheximide for the indicated time intervals, in the absence or presence of MG132 (25 μM). Expression of Skp2 and GAPDH was analysed by immunoblotting. (C) HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated Skp2 constructs and synchronized in M phase by mitotic shake-off of cells obtained 8 h after release from a double-thymidine block. The cells were then re-plated and allowed to progress into G1 in the presence of cycloheximide (100 μg/ml). Skp2, cyclin B1, phospho-Ser10 H3 and GAPDH were detected by immunoblotting. The results are representative of four independent experiments. (D) Quantification of Skp2 degradation shown in panel C. (E) NIH 3T3 cells were co-transfected with Skp2-HA and increasing amounts of Flag-Cdh1. Lysates were analysed by immunoblotting with antibodies to HA, Flag and GAPDH. (F) 293 cells were co-transfected with wild-type Skp2-HA or the indicated mutants together with Myc6-Cdh1. After 48 h, Myc6-Cdh1 complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody and analysed by immunoblotting. The ratio of unphosphorylated Ser64 to phospho-Ser64 for wild-type Skp2 in the lysate and the Myc immunoprecipitate was quantified from three independent experiments (lower panel). (G) Control and Skp2−/− MEFs were co-transfected with Myc6-EGFP together with low amounts of the indicated Skp2-HA constructs. The cells were then serum starved for 24 h and BrdU was incorporated during the last 10 h. The percentage of Myc-transfected cells that incorporated BrdU was evaluated by immunofluorescence. The results are expressed as mean±SEM of nine experiments (upper panel). Expression of EGFP and Skp2-HA was monitored by immunoblotting (lower panels).

We examined the phylogenetic conservation of Skp2 phosphorylation sites (Figure 1G). This analysis revealed that Ser64 (or a Thr residue) is conserved in all Skp2 orthologues. Interestingly, the Ser64 phosphorylation site is always located about 30 residues N-terminal to the F-box. Ser72 is present in all mammalian Skp2 except in mouse, which displays a glycine at position 72. Other rodents (rat and squirrel) have the Ser72 residue, suggesting that the mutation of Ser72 in the mouse is a relatively recent event. Notably, human Skp2 becomes phosphorylated on Ser72 in NIH 3T3 cells, indicating that mouse cells express the kinase(s) responsible for this modification (Supplementary Figure 1D).

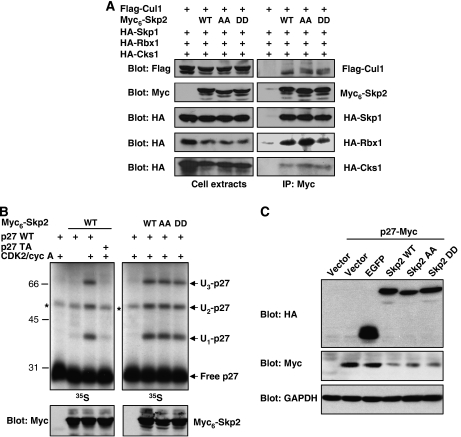

SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase activity is not influenced by Ser64/Ser72 phosphorylation

We evaluated whether Skp2 phosphorylation affects its subcellular localization. As previously observed (Sutterluty et al, 1999), ectopically expressed Skp2 was found exclusively in the nucleus in the vast majority of cells. Immunofluorescence studies indicated that the subcellular localization of Skp2 is not affected by Ser64/Ser72 phosphorylation (Supplementary Figure 2). On the other hand, it is known that the activity of some ubiquitin ligases can be modulated by direct phosphorylation (Bassermann et al, 2005). We first investigated the effect of Skp2 phosphorylation on the assembly of the SCFSkp2 complex by co-immunoprecipitation experiments. 293 cells were transfected with epitope-tagged SCF subunits Cul1, Skp1 and Rbx1, along with Myc6-tagged wild-type Skp2 or mutants S64A/S72A (AA) and S64D/S72D (DD). The Skp2 cofactor Cks1 was also included in these experiments. Essentially the same amounts of SCF subunits were immunoprecipitated by wild-type Skp2 and phosphorylation mutants (Figure 2A). Identical results were obtained using the C-terminal HA-tagged Skp2 constructs (Supplementary Figure 3). Hence, Skp2 phosphorylation does not affect SCFSkp2/Cks1 complex formation.

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation of Skp2 on Ser64/Ser72 does not affect SCFSkp2 activity. (A) 293 cells were co-transfected with epitope-tagged Cul1, Skp1, Rbx1, Cks1 and the indicated Myc6-Skp2 constructs. SCF complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody and analysed by immunoblotting. (B) Immunoprecipitated SCFSkp2/Cks1 complexes obtained as in panel A were used in p27 in vitro ubiquitination assays. In vitro-translated 35S-labelled wild-type (WT) p27 or T187A (TA) mutant was phosphorylated by recombinant CDK2/cyclin A before the reaction. Methyl ubiquitin was added to the assay. The reaction products were analysed by autoradiography. (C) HeLa cells were co-transfected with p27-Myc together with HA-tagged EGFP or Skp2 constructs. Expression of ectopic p27 and Skp2 was detected by immunoblotting.

The impact of phosphorylation on Skp2 E3 activity was directly assayed in an in vitro ubiquitination assay using p27 as substrate. SCFSkp2/Cks1 was immunoprecipitated from transfected 293 cells and incubated with 35S-labelled in vitro-translated p27 in the presence of E1, UbcH3 and an energy regenerating system. Methyl ubiquitin was added to the reaction to inhibit polyubiquitin chain assembly and help visualize p27 ubiquitination. Under these conditions, Skp2 catalyses the ubiquitination of p27 on presumably three sites (Figure 2B), as reported previously (Carrano et al, 1999). The ubiquitination of p27 is contingent upon phosphorylation of Thr187 by CDK2/cyclin A. The Skp2 AA and DD mutants displayed the same ubiquitination activity towards p27 as the wild-type protein (Figure 2B). The activity of Skp2 was also tested in vivo. We found that overexpression of wild-type Skp2 or its phosphorylation mutants similarly downregulated co-transfected p27 in HeLa cells (Figure 2C). Collectively, our results suggest that the intrinsic ubiquitin ligase activity of Skp2 is not regulated by phosphorylation of Ser64/Ser72.

Phosphorylation of Ser64/Ser72 negatively regulates Skp2 degradation by APCCdh1

We noticed that while overexpressed Skp2 is found in two forms in Rat1 cells, Skp2 expressed at more physiological levels is found only in the Ser64-phosphorylated form (Figure 3A). The same observation was made in HeLa cells and other cell types (data not shown). This suggests that the Skp2 Ser64 kinase(s) may be limiting. Importantly, expression of lower amounts of Skp2 also revealed a role of Skp2 phosphorylation in regulating its abundance. We observed that non-phosphorylatable mutants of Skp2 are expressed at lower levels than the wild-type protein, whereas the phosphomimetic Skp2 DD mutant is expressed at higher levels (Figure 3A). Mutation of Ser64 alone had a profound effect on Skp2 expression in other cell types analysed (data not shown). To test the impact of phosphorylation on Skp2 stability, we first measured the half-life of the two forms of Skp2 by cycloheximide-chase analysis. The Ser64-unphosphorylated form of Skp2 was found to be highly unstable, with a half-life of less than 1 h (Figure 3B). Incubation with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 reduced the degradation rate of Skp2. On the other hand, the Ser64-phosphorylated form of Skp2 was relatively stable with a half-life of >4 h.

Skp2 is targeted for degradation by the APCCdh1 complex (Bashir et al, 2004; Wei et al, 2004). To address the role of Skp2 phosphorylation in this process, we first measured the half-life of Skp2 mutants in HeLa cells synchronized at the M → G1 transition, a period of high APCCdh1 activity (Peters, 2006). Round mitotic cells obtained 8 h after release from a double-thymidine block were collected and released into G1 phase in the presence of cycloheximide. Mitotic exit was monitored by the loss of histone H3 phospho-Ser10 immunoreactivity. When expressed at low physiological concentrations, Skp2 and its various mutants did not perturb the transition from M to G1 phase (Supplementary Figure 4). We found that wild-type Skp2-HA (stoichiometrically phosphorylated on Ser64) is degraded with a half-life of ∼2.5 h (Figure 3C and D). An Skp2 mutant lacking the N-terminal D-box (ΔD-box) is completely stable, confirming that degradation of the protein is dependent on APCCdh1 in these conditions. Skp2 S64A and, to a lesser extent, Skp2 S72A were more efficiently degraded than the wild-type protein. More strikingly, Skp2 AA was degraded very rapidly with a half-life of 30 min. On the contrary, the phosphomimetic Skp2 DD mutant was slightly more stable than wild-type Skp2. Under these conditions, cyclin B1 is efficiently degraded as cells exit mitosis.

APCCdh1 can be ectopically activated by Cdh1 overexpression (Bashir et al, 2004; Wei et al, 2004). Expression of moderate amounts of Skp2 in NIH 3T3 cells results in the presence of both the phospho- and non-phospho-Ser64 forms of Skp2 (Figure 3E). Coexpression of increasing levels of Cdh1 induced a gradual and preferential degradation of the non-phospho-Ser64 form of Skp2 (Figure 3E). Consistent with this result, Skp2 S64A was highly susceptible to Cdh1 action whereas the phosphomimetic DD mutant was more resistant. To directly test if phosphorylation of Skp2 affects its interaction with Cdh1, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments. As previously reported (Bashir et al, 2004; Wei et al, 2004), Skp2 was found to specifically associate with Cdh1 (Figure 3F). Importantly, Cdh1 associated preferentially with the non-phospho-Ser64 form of Skp2. Quantitative analysis revealed a >10-fold enrichment of the non-phospho-Ser64 form of Skp2 in the Cdh1-bound fraction relative to the cell lysate (Figure 3F, lower panel). No such bias is seen in the case of Skp2/Cks1 or Skp2/Skp1 association (see Supplementary Figure 3). Accordingly, Skp2 S64A and AA mutants bound strongly to Cdh1, whereas Skp2 DD interacted only weakly. Together, these results indicate that phosphorylation of Skp2, mainly on Ser64, stabilizes the protein by interfering with its recognition by APCCdh1.

To further investigate the biological significance of Skp2 phosphorylation, we tested the ability of Skp2 mutants to promote S-phase entry (Sutterluty et al, 1999). Since expression of high levels of Skp2 masks the stabilizing effect of Skp2 phosphorylation (see Figure 3A), it is necessary to transfect low amounts of plasmid DNA to express close-to-physiological concentrations of Skp2. These experiments were thus conducted in Skp2−/− cells, which are highly sensitive to the effect of Skp2 on the cell cycle. The expression of Myc6-EGFP, co-transfected with the indicated Skp2 constructs, confirmed that the transfection efficacy was comparable (Figure 3G, lower panel). S-phase entry of Myc+ cells was monitored by BrdU incorporation. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that Skp2 mutants are expressed at different levels (Figure 3G). Importantly, these differences in expression levels translated into functional differences in Skp2 activity in vivo. The percentage of BrdU-positive cells was significantly lower in cells reconstituted with the Skp2 AA mutant as compared to the wild-type protein or DD mutant (Figure 3G). We conclude that phosphorylation of Ser64/Ser72 is a key event controlling Skp2 accumulation and, hence, biological activity.

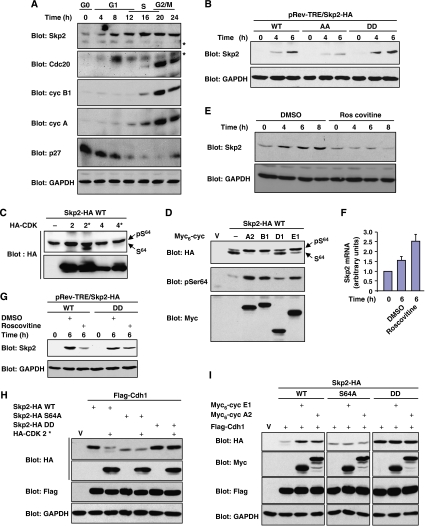

CDK2 phosphorylates Skp2 on Ser64 resulting in its stabilization

The high activity of APCCdh1 during G1 phase ensures that expression of its substrates remains low during this period (Peters, 2006). However, we and others have previously observed that Skp2 expression is apparent at mid-G1 in various cell lines (Carrano et al, 1999; Kim et al, 2003; Rodier et al, 2005; Sarmento et al, 2005). In Rat1 cells for example, Skp2 starts to accumulate 4–6 h after exit from G0 (Figure 4A and E). In fact, Skp2 is induced prior to other APCCdh1 substrates such as Cdc20, cyclin B1 and cyclin A (Figure 4A). These observations suggest that Skp2 expression in G1 is regulated differently than other APCCdh1 substrates. Because it counteracts APCCdh1 action, phosphorylation of Skp2 might be involved in its G1 accumulation. To test this idea, we compared the expression of Skp2 phosphorylation mutants, induced from a conditional promoter, during G1 progression. The DD mutant accumulated to levels significantly higher than the non-phosphorylatable mutant of Skp2 (Figure 4B), suggesting that phosphorylation plays a role in regulating Skp2 expression in G1 phase.

Figure 4.

Ser64 phosphorylation catalysed by CDK2 stabilizes Skp2 expression in G1 phase. (A) Expression of Skp2 occurs before other APCCdh1 substrates in G1 phase. Rat1 cells were made quiescent by contact inhibition and released into G1 by re-plating at low density for the times indicated. The expression of Skp2, Cdc20, cyclin B1, cyclin A, p27 and GAPDH was analysed by immunoblotting. * Marks nonspecific bands. (B) Rat1 cells expressing doxycycline-inducible HA-tagged Skp2 constructs were serum starved for 24 h and then stimulated with 10% serum and doxycycline (1 μg/ml) for the indicated times. HA-Skp2 and GAPDH were detected by immunoblotting. (C) Rat1 cells were co-transfected with Skp2-HA together with wild-type or dominant-negative forms (*) of HA-CDK2 or HA-CDK4. Lysates were analysed by anti-HA immunoblotting. (D) NIH 3T3 cells were co-transfected with high amounts of Skp2-HA together with the indicated Myc6-tagged cyclins. Lysates were analysed by anti-HA, anti-phospho-Ser64 and anti-Myc immunoblotting. (E) Contact-inhibited Rat1 cells were released into G1 in the presence of roscovitine (25 μM) or vehicle for the indicated times. Expression of endogenous Skp2 was analysed by immunoblotting. (F) Q-PCR analysis of Skp2 mRNA in Rat1 cells treated as in panel E. (G) Quiescent Rat1 cells expressing doxycycline-inducible Skp2-HA were stimulated with serum and doxycycline, in the presence or absence of roscovitine. Expression of Skp2 was analysed by immunoblotting. Rat1 (H) and NIH 3T3 (I) cells were transfected with the indicated constructs. Lysates from exponentially proliferating cells were analysed by immunoblotting.

We focused our analysis on Ser64 phosphorylation since this conserved site has a major impact on Skp2 stability. The results of in vitro kinase assays using extracts from synchronized cells indicated that Skp2 Ser64 kinase activity is induced in G1 and reaches high activity in S and M phases (Supplementary Figure 5A and B). Because Ser64 lies in a perfect CDK consensus site, we sought to determine whether CDK activity could mediate the phosphorylation of Skp2 on Ser64. CDK2/cyclin A efficiently phosphorylated Skp2 on Ser64 in vitro (Supplementary Figure 5C; Yam et al, 1999). Incubation with the CDK1/CDK2 inhibitor roscovitine or addition of the CDK inhibitor p27 markedly inhibited Ser64 kinase activity in HeLa cell extracts (Supplementary Figure 5B). In vivo experiments showed that co-transfection of Skp2 with dominant-negative CDK2, but not the equivalent CDK4 mutant, results in the accumulation of the non-phospho-Ser64 form of Skp2 (Figure 4C). Reciprocally, overexpression of cyclin activators of CDK2 (cyclin E1 and A2) and CDK1 (cyclin B1) induced the phosphorylation of Skp2 on Ser64 (Figure 4D). Cyclin D1 only had a minimal effect in this assay. Finally, the activation profiles of CDK2- and cyclin E-associated histone H1 kinase in Rat1 cells were very similar to that of Ser64 kinase (Supplementary Figure 5D). Altogether, these findings provide compelling evidence that CDK2 and potentially CDK1 are major Skp2 Ser64 kinases in vivo.

We next evaluated the impact of CDK2 activity on Skp2 expression. Inhibition of CDK2 activity by roscovitine suppressed the induction of endogenous Skp2 expression during G1 progression (Figure 4E), without interfering with Skp2 mRNA induction (Figure 4F). Similar results were obtained with the CDK2 inhibitors SU9516 and olomoucine (Supplementary Figure 5E). Importantly, roscovitine effectively prevented the accumulation of wild-type Skp2 but not that of the phosphomimetic mutant (Figure 4G), demonstrating the importance of CDK2-mediated phosphorylation in regulating the expression of Skp2 in G1 phase. The results with roscovitine were confirmed using a dominant-negative form of CDK2. Overexpression of inactive CDK2 downregulated the expression of wild-type Skp2 but not that of S64A or DD mutant in the presence of ectopically activated APCCdh1 (Figure 4H). Reciprocally, stimulating CDK2 activity by ectopic expression of cyclin E1 or A2 upregulated the expression of Skp2 in the presence of active APCCdh1 (Figure 4I). It is known that Cdh1 can be inactivated by direct phosphorylation by CDK2, resulting in impaired association with the APC core (Kramer et al, 2000). To control for this possibility, the expression of Skp2 S64A mutant was also examined. Activators of CDK2 failed to stabilize the expression of Skp2 S64A, indicating that APCCdh1 is active under these conditions (Figure 4I). As expected, phosphomimetic Skp2 DD was insensitive to CDK2-mediated stabilization effect (Figure 4I). We conclude that CDK2-mediated Ser64 phosphorylation opposes the degradation of Skp2 by APCCdh1.

The phosphorylation of endogenous Skp2 was monitored in synchronized HeLa cells using phosphospecific antibodies. As previously reported, expression of Skp2 is low in G1 and increases in S and M phases (Supplementary Figure 6A). Interestingly, phospho-Ser64 immunoreactivity follows the same distribution. This observation, coupled to the fact that endogenous Skp2 is always seen as a single band on immunoblots (see Figures 1F, 3A, 4A and 5F), suggests that Skp2 is stoichiometrically phosphorylated on Ser64 at steady state. Immunodepletion experiments performed with anti-phospho-Ser64 antibody revealed that Skp2 is >95% phosphorylated on Ser64 in vivo (Supplementary Figure 6B and C). Given that non-phospho-Ser64 Skp2 is highly unstable and susceptible to APCCdh1 degradation (see Figure 3), the absence of this form (especially in G1 phase, which contains low CDK activity) argues that phosphorylation of Ser64 is limiting for Skp2 expression.

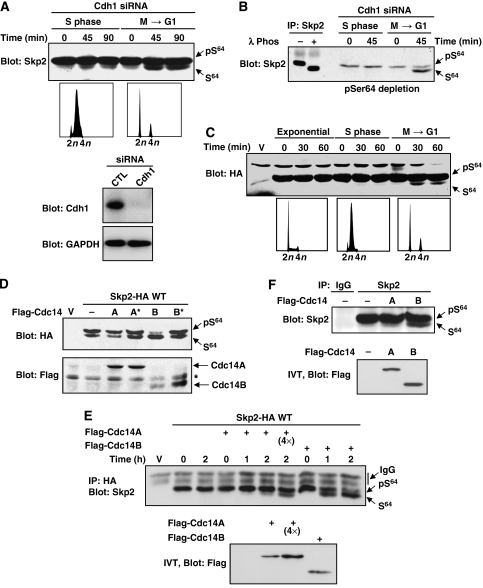

Figure 5.

Cdc14B dephosphorylates Skp2 on Ser64. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with Cdh1 siRNA and synchronized in S or M phase (FACS profiles). Cells were allowed to progress into the cell cycle in the presence of cycloheximide and roscovitine (100 μM) for the times indicated. Endogenous expression of Skp2 (upper panel), Cdh1 and GAPDH (lowers panels) was evaluated by immunoblotting. (B) Cell lysates prepared as in panel A were immunodepleted with the phospho-Ser64 antibody and analysed by immunoblotting with anti-Skp2 antibody. Note the enrichment of the faster migrating band of Skp2. In a parallel experiment, endogenous Skp2 was immunoprecipitated and subjected to extensive dephosphorylation using λ phosphatase (left panel). (C) HeLa cells were transfected with the ΔD-box mutant of Skp2. Exponentially proliferating cells, cells synchronized in S phase or cells at M/G1 transition were monitored for Skp2 expression by anti-HA immunoblotting. (D) Rat1 cells were co-transfected with Skp2-HA together with Flag-tagged Cdc14A or Cdc14B or their respective inactive mutants (*). Lysates were analysed by immunoblotting. (E) 293 cells were transfected with low amounts of Skp2-HA. After 48 h, Skp2-HA was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA and incubated with in vitro-translated Cdc14A or Cdc14B for the indicated times. Skp2 dephosphorylation was analysed by anti-HA immunoblotting. When indicated (4 × ), four times more Cdc14A was used in the assay. (F) Endogenous Skp2 was immunoprecipitated from proliferating HeLa cells and incubated with in vitro-translated Cdc14A or Cdc14B for 2 h. Note that Skp2 dephosphorylation by Cdc14B results in the presence of a faster migrating band.

Cdc14B specifically dephosphorylates Skp2 on Ser64 and renders it more susceptible to APCCdh1 degradation

Skp2 is highly phosphorylated on Ser64 in mitosis (Supplementary Figure 6). Since Skp2 is degraded at the M → G1 transition, we asked whether the protein is subjected to dephosphorylation prior to its degradation. Because non-phosphorylated Skp2 is highly susceptible to APCCdh1 (Figures 3 and 4), this form of Skp2 is predicted to be at very low level. To allow for its accumulation, experiments were conducted in cells treated with Cdh1 siRNA to inhibit Skp2 degradation. The phosphorylation stoichiometry of Skp2 on Ser64 was monitored at different stages of the cell cycle in the presence of roscovitine. Exit from mitosis was associated with the appearance of a faster migrating species of Skp2 (Figure 5A). This band was significantly enriched when the lysates were immunodepleted with the phospho-Ser64 antibody, indicating that it is not phosphorylated on Ser64 (Figure 5B). Complete dephosphorylation of Skp2 by λ phosphatase induced a similar shift of migration (Figure 5B). Experiments with the stable mutant ΔD-box confirmed that Skp2 is dephosphorylated specifically at the M → G1 transition (Figure 5C). Together, these results demonstrate that Skp2 is dephosphorylated at times of active degradation.

Specific protein phosphatases play an important role in regulating mitosis (Trinkle-Mulcahy and Lamond, 2006). Among these, Cdc14 preferentially dephosphorylates proteins modified by proline-directed kinases (Gray et al, 2003). These observations prompted us to test the involvement of Cdc14A and Cdc14B homologues in Skp2 dephosphorylation. Overexpression of Cdc14B, but not Cdc14A, markedly suppressed the phosphorylation of Skp2 on Ser64 (Figure 5D). Inactive mutants of Cdc14 had no effect. To verify that this effect is direct, we performed in vitro dephosphorylation assays. HA-tagged Skp2 (stoichiometrically phosphorylated on Ser64) was immunoprecipitated from 293 cells and incubated with in vitro-translated Cdc14A or Cdc14B in phosphatase buffer. Cdc14B was found to robustly dephosphorylate phospho-Ser64, whereas Cdc14A displayed only weak activity at higher concentrations in this assay (Figure 5E). The endogenous Skp2 protein was also specifically dephosphorylated by Cdc14B in vitro (Figure 5F).

The above results predict that Cdc14B should stimulate the degradation of Skp2 by APCCdh1. In support of this hypothesis, overexpression of Cdc14B, but not Cdc14A, downregulated Skp2 expression in the presence of active APCCdh1 (Figure 6A). This effect of Cdc14B required the catalytic activity of the phosphatase (Figure 6B). As expected, Cdc14B markedly lowered the stoichiometry of Skp2 phosphorylation on Ser64. In yeast, Cdc14 directly participates in APCCdh1 activation by catalysing dephosphorylation of Cdh1 (Jaspersen et al, 1999). It is unknown whether Cdc14B exerts a similar function in mammals, but we cannot exclude the possibility that Cdc14B stimulates Skp2 degradation by enhancing APCCdh1 activity. However, we found that the phosphomimetic mutant of Skp2 is insensitive to Cdc14B action, strongly suggesting that Cdc14B promotes Skp2 degradation through Ser64 dephosphorylation (Figure 6C). Cycloheximide-chase analysis confirmed that Cdc14B increases the turnover of Skp2 in Cdh1-overexpressing cells (Figure 6D). Cdc14B overexpression also enhanced the degradation of Skp2 under physiological APCCdh1 activation in synchronized HeLa cells exiting mitosis (Figure 6E). Of note, ectopic expression of Cdc14B did not affect the kinetics of M → G1 transition (Supplementary Figure 7A).

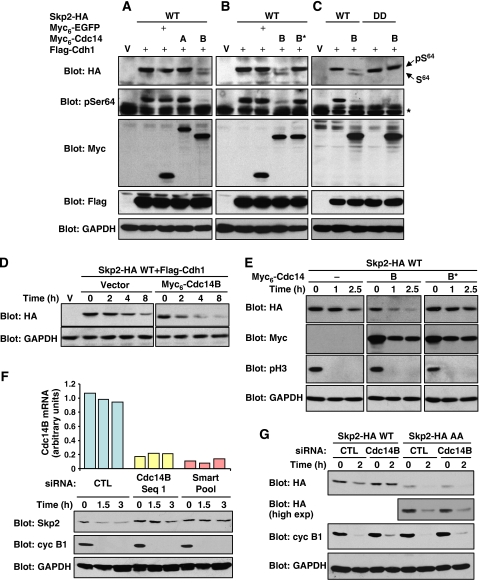

Figure 6.

The phosphatase activity of Cdc14B stimulates Skp2 degradation by APCCdh1. (A–C) NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and lysates were analysed by immunoblotting. (D) NIH 3T3 cells were co-transfected with Skp2-HA and Flag-Cdh1 with or without Myc6-Cdc14B. After 48 h, the half-life of Skp2 was evaluated by cycloheximide-chase analysis. (E) HeLa cells were co-transfected with Skp2-HA together with Myc6-Cdc14B (wild-type or inactive mutant) and synchronized in M phase. Cells were released into G1 in the presence of cycloheximide. Expression of Skp2, Cdc14B and GAPDH was analysed by immunoblotting. Mitotic exit was monitored by phospho-Ser10 histone H3 immunoreactivity. (F) HeLa cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNAs targeting Cdc14B. Mitotic cells were released into G1 phase for the indicated times. CDC14B mRNA levels were measured by real-time Q-PCR (upper panel). Expression of endogenous Skp2, cyclin B1 and GAPDH was analysed by immunoblotting. (G) HeLa cells were transfected with either wild-type Skp2-HA or AA mutant and treated with control or Cdc14B siRNA. Mitotic cells were collected and allowed to enter G1 for 2 h. Lysates were analysed by immunoblotting.

As a complement to these gain-of-function experiments, we evaluated the effect of Cdc14B depletion by RNA interference. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs to Cdc14B (either single or as a pool of four sequences) or control siRNA, and expression of endogenous Skp2 was monitored during M → G1 transition. Silencing of Cdc14B expression prevented the downregulation of Skp2 observed when cells exit mitosis (Figure 6F). Mitotic exit and degradation of cyclin B1 was not affected, confirming the specificity of the silencing effect (Figure 6F and Supplementary Figure 7B). Similar results were obtained in T98G cells released from a nocodazole block (data not shown). The possibility that Cdc14B depletion lowers APCCdh1 activity is unlikely because degradation of cyclin B1 or Cdc20 was unaffected by Cdc14B silencing (Figures 6F and 7A). However, to further exclude this possibility, we monitored the degradation of a non-phosphorylatable mutant of Skp2. Since this mutant is not stabilized by phosphorylation, it should be insensitive to Cdc14B action. Strikingly, the Skp2 AA mutant was degraded similarly in control and Cdc14B-depleted cells, whereas the wild-type protein was stabilized by Cdc14B knockdown (Figure 6G). These results are consistent with the hypothesis that Cdc14B controls Skp2 stability via the phosphorylation state of Ser64.

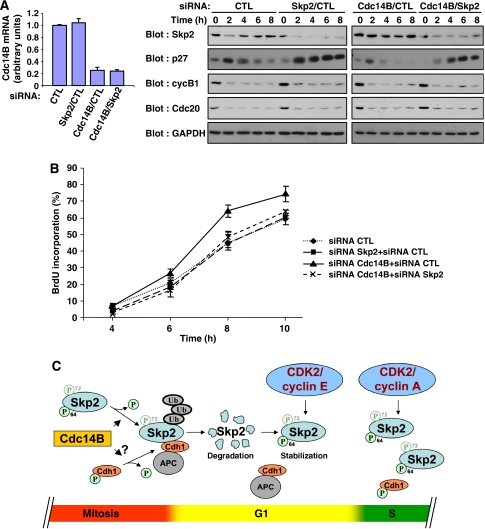

Figure 7.

Cdc14B regulates S-phase entry in an Skp2-dependent manner. (A) HeLa cells were treated with siRNAs targeting Cdc14B and/or Skp2. Mitotic cells were collected and released into the cell cycle for the indicated times. CDC14B mRNA levels were measured by real-time Q-PCR. Expression of the indicated endogenous proteins was analysed by immunoblotting. (B) Mitotic HeLa cells treated as in panel A were re-plated on coverslips and allowed to progress into the cell cycle in the presence of BrdU. The percentage of cells that incorporated BrdU was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy. The results are expressed as mean±SEM of six experiments. (C) Model of the regulation of Skp2 expression by phosphorylation during cell cycle progression. During mitotic exit, Cdc14B actively dephosphorylates Skp2 on Ser64, thereby allowing its efficient association with APCCdh1 and subsequent degradation. Cdc14B might also stimulate APCCdh1 activity by promoting Cdh1 dephosphorylation. During G1 progression, induction of CDK2/cyclin E activity stabilizes Skp2 expression by phosphorylating Ser64, even in the presence of active APCCdh1. In S phase, CDK2/cyclin A further stabilizes Skp2 by inactivating Cdh1 by phosphorylation. Ser72 phosphorylation plays a significant but minor role in controlling Skp2 stability.

Cdc14B depletion accelerates S-phase entry in an Skp2-dependent manner

It is known that inhibiting Skp2 degradation at the M → G1 transition shortens G1 phase (Bashir et al, 2004; Wei et al, 2004). We therefore asked whether the higher levels of Skp2 observed in Cdc14B-depleted cells also accelerate G1 progression. HeLa cells were transfected with control or Cdc14B siRNA and mitotic cells were collected after release from a double-thymidine block. The cells were then released into G1 in the presence of BrdU to monitor DNA replication. Depletion of Cdc14B impaired Skp2 degradation and significantly accelerated S-phase entry (Figure 7A and B). To determine whether the effect on cell cycle is related to Skp2, we knocked down Skp2 expression by RNA interference in cells depleted of Cdc14B. As observed previously, reducing Skp2 levels alone had a minimal effect on G1 progression and S-phase entry in HeLa cells (Figure 7B; Bashir et al, 2004; Wei et al, 2004). However, downregulation of Skp2 expression almost completely reversed the S-phase-promoting effect of Cdc14B depletion (Figure 7A and B). This finding suggests that Skp2 is a major cellular target of Cdc14B.

We also monitored the expression levels of p27. Expression of p27 is low in mitotic cells, rises in early G1 and then declines as cells move towards S phase (Figure 7A). Silencing of Skp2 expression increased the levels of p27, whereas Cdc14B depletion was associated with very low levels of p27 throughout G1. Concomitant loss of Cdc14B and Skp2 restored the high levels of p27, confirming the genetic interaction between Cdc14B and Skp2.

Discussion

Importance of substrate modification in APC-mediated ubiquitination

It is currently viewed that SCF activity is regulated mainly at the level of substrate activation, whereas ubiquitination of APC substrates is regulated by the activity of the ligase itself. Several mechanisms such as phosphorylation of APC subunits, the spindle-assembly checkpoint or Emi1 accumulation have been documented to affect APC ligase activity (Peters, 2006). Moreover, relative differences in the processivity of substrate ubiquitination contribute to establish the order in which APC substrates are degraded during cell cycle progression (Rape et al, 2006). Nevertheless, accumulating evidence indicates that substrate modification provides an additional layer of control over APC-mediated ubiquitination. In this study, we show that phosphorylation of Skp2, mainly on Ser64, protects it from APCCdh1-mediated degradation. Accordingly, non-phosphorylatable Skp2 mutants are less stable than the wild-type protein in cells entering G1 phase. Suppression of Ser64 phosphorylation (by inhibiting CDK2 or by Cdc14B overexpression) leads to enhanced APCCdh1-mediated Skp2 degradation, whereas stimulation of Ser64 phosphorylation has the opposite effect. Functionally, the stable phosphomimetic DD mutant of Skp2 potently stimulates S-phase entry in serum-deprived Skp2−/− cells, while the non-phosphorylatable AA mutant, which is expressed at lower levels, is impaired in this assay. Other APC substrates were also shown to be regulated by phosphorylation. For instance, it has been reported that phosphorylation of the mitotic kinase Aurora A (Littlepage and Ruderman, 2002), the yeast securin orthologue Pds1 (Wang et al, 2001) and the licensing factor Cdc6 (Mailand and Diffley, 2005) protects them from APCCdh1-mediated degradation. On the other hand, phosphorylation of the transcription factor AML1/RUNX1 was recently shown to promote its degradation by APCCdc20 (Biggs et al, 2006). In the case of Skp2, we propose that phosphorylation contributes to the accumulation of the protein in G1 phase while APCCdh1 is still active (Figure 7C).

Regulation of SCF activity by phosphorylation of F-box proteins

There is a precedent for the regulation of SCF ligase activity by phosphorylation of the F-box component. Assembly of the SCFNIPA ubiquitin ligase is regulated by cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of the F-box protein NIPA, which restricts its activity to interphase (Bassermann et al, 2005). In contrast, SCFSkp2/Cks1 complex assembly and ubiquitin ligase activity are not affected by Ser64/Ser72 phosphorylation of Skp2. Our results indicate that the differential ability of Skp2 phosphorylation mutants to induce S-phase entry (Figure 3F) is caused by differences in stability rather than catalytic activity. Thus, phosphorylation of F-box proteins may impact on SCF activity by different mechanisms. Given the number (>70 in humans) and diversity of mammalian F-box proteins (Cardozo and Pagano, 2004), it is likely that other SCF complexes will be found to be regulated by phosphorylation.

Relevance of Skp2 phosphorylation and stabilization in G1 phase

What is the significance of the stabilization of Skp2 by phosphorylation? One possibility is that Skp2 function is needed in G1. Indeed, Skp2 was reported to interact with c-Myc in G1 phase and to regulate both its stability and transcriptional activity (Kim et al, 2003; von der Lehr et al, 2003). Other transcription factors known to be active in G1 are also targets of Skp2 (Nakayama and Nakayama, 2006). Importantly, Skp2 may contribute to the degradation of nuclear p27 in G1. Despite the observation that p27T187A is still degraded in G0/G1 (Malek et al, 2001) and the identification of the ubiquitin ligase KPC, which selectively degrades p27 in G1 phase (Kamura et al, 2004), there is experimental evidence to support a role of Skp2 in regulating p27 levels in G1. First, depletion of Skp2 by RNA interference results in a more pronounced upregulation of p27 in G1 phase (Figure 7; Bashir et al, 2004; Wei et al, 2004). Second, raising the levels of Skp2 by silencing of Cdh1 (Bashir et al, 2004; Wei et al, 2004) or Cdc14B (Figure 7) expression accelerates the turnover of p27 in G1, suggesting that Skp2 is limiting in this process. Importantly, the accelerated degradation of p27 induced by Cdh1 or Cdc14B depletion is dependent on the presence of Skp2. These results highlight a possible role of Skp2, in addition to the KPC complex, in the regulation of p27 in G1 phase. This idea is consistent with the previous observation that p27 downregulation in G1 phase is impaired during liver regeneration in Skp2−/− mice (Kossatz et al, 2004).

Cdc14B regulates Skp2 levels and G1-phase length in human cells: a link with cancer

Cdc14 functions in many cell cycle processes that vary between organisms (Trinkle-Mulcahy and Lamond, 2006). Human cells express two Cdc14 homologues, Cdc14A and Cdc14B, whose substrates and functions remain to be characterized. Here we show that Cdc14B, but not Cdc14A, dephosphorylates Ser64 of Skp2 both in vitro and in vivo. By dephosphorylating Ser64, Cdc14B promotes the degradation of Skp2 by APCCdh1 at the M → G1 transition. The observation that a non-phosphorylatable mutant of Skp2 is efficiently degraded in Cdc14B-depleted cells provides strong evidence that Cdc14B exerts its effect at the level of Skp2 dephosphorylation and not Cdh1. Consistent with this idea, degradation of other APCCdh1 substrates proceeds normally in these cells.

Importantly, our results reveal a role of Cdc14B in regulating the length of G1 phase in human cells. Silencing of Cdc14B expression accelerates the progression of HeLa cells from mitosis to S phase. This effect is reversed by treatment of cells with Skp2 siRNA, demonstrating the epistatic relationship of Cdc14B and Skp2 in G1 control. Cdc14 was identified in a genetic screen in C. elegans as a gene product required to maintain the quiescent state of specific precursor cells during development (Saito et al, 2004). Interestingly, genetic experiments indicated that Cdc14 functions upstream of CKI-1 in these cells. The control of G1 progression, and thus of cell proliferation, may be a conserved function of Cdc14 proteins in animals. To further substantiate this idea, we interrogated the Oncomine database (Rhodes et al, 2007) for potential changes in CDC14B mRNA levels in tumour tissues. Interestingly, lower CDC14B expression in tumours was found for the majority (67%) of studies showing significant (P<0.05) differences in gene expression between normal and cancer tissues (Supplementary Figure 8). Low CDC14B expression also correlated with tumour grade and was associated with bad prognosis in 83 and 80% of the studies, respectively (Supplementary Figure 8). These observations suggest that Cdc14B may exert tumour suppressor activity in certain tissues. Additional experiments are required to evaluate the possibility that loss of Cdc14B is responsible for the high levels of Skp2 often observed in human cancers.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, transfections and cell synchronization

Cell lines were grown in standard culture media. Wild-type and Skp2−/− MEFs (kindly provided by KI Nakayama) were immortalized by a 3T3 protocol. 293 cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate method. T98G, HeLa and NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with lipofectamine reagent. Rat1 cells and MEFs were transfected using Fugene 6.

For synchronization experiments, HeLa cells were treated with 2 mM thymidine for 12 h, washed and released into fresh medium for 8 h. Then, a second thymidine treatment was applied to yield cells at the G1/S transition. S-phase cells were obtained after release for 2–3 h in drug-free medium. Mitotic cells were obtained by shake-off of cells 8 h after release in fresh medium. To obtain cells in G1, mitotic rounded cells were re-plated and harvested at different time points. When indicated, cells were transfected during the last 4 h before the second thymidine block. For single siRNA treatments, the cells were transfected with Cdc14B siRNA before the first thymidine block. When indicated, the cells were transfected with the second siRNA targeting Skp2 between the two thymidine treatments. For synchronization in G0, Rat1 cells were arrested by contact inhibition for 3 days and re-plated at low confluence to allow cell cycle re-entry. MEFs were made quiescent by serum deprivation for 24 h. Mitotic T98G cells were obtained by mitotic shake-off after treatment with nocodazole (100 ng/ml) for 18 h.

In vitro dephosphorylation assays

Low amount of Skp2-HA was expressed in 293 cells to ensure its full phosphorylation on Ser64. The ectopic Skp2 protein was purified by immunoprecipitation with anti-HA and incubated in phosphatase buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT) with in vitro-translated Cdc14A or Cdc14B for 1–2 h at 30°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of SDS buffer and Skp2 was analysed by immunoblotting. For assays with the endogenous protein, Skp2 was immunoprecipitated from extracts of exponentially proliferating HeLa cells with a specific antibody.

For dephosphorylation assays using λ phosphatase, Skp2 immunoprecipitates were washed twice in phosphatase buffer (provided by the supplier) and then incubated at 30°C for 2 h with 200 U of λ phosphatase.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1–8

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to M Pagano, SI Reed, D D'amours, D Beach, T Hunter, P Jolicoeur, KI Nakayama and M Baril for providing reagents. We thank P Chagnon for help in Q-PCR and D D'amours for helpful discussions and comments. G Rodier is recipient of fellowships from the NCIC and the American Association for Cancer Research (Anna D Barker Fellowship) and P Coulombe is recipient of a studentship from the NCIC. S Meloche holds the Canada Research Chair in Cellular Signaling. This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

References

- Bashir T, Dorrello NV, Amador V, Guardavaccaro D, Pagano M (2004) Control of the SCF(Skp2-Cks1) ubiquitin ligase by the APC/C(Cdh1) ubiquitin ligase. Nature 428: 190–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassermann F, von Klitzing C, Munch S, Bai RY, Kawaguchi H, Morris SW, Peschel C, Duyster J (2005) NIPA defines an SCF-type mammalian E3 ligase that regulates mitotic entry. Cell 122: 45–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs JR, Peterson LF, Zhang Y, Kraft AS, Zhang DE (2006) AML1/RUNX1 phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent kinases regulates the degradation of AML1/RUNX1 by the anaphase-promoting complex. Mol Cell Biol 26: 7420–7429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein G, Bloom J, Sitry-Shevah D, Nakayama K, Pagano M, Hershko A (2003) Role of the SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase in the degradation of p21Cip1 in S phase. J Biol Chem 278: 25752–25757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo T, Pagano M (2004) The SCF ubiquitin ligase: insights into a molecular machine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 739–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrano AC, Eytan E, Hershko A, Pagano M (1999) SKP2 is required for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27. Nat Cell Biol 1: 193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HP, Liu Y, Gomez M, Dunlap J, Tyers M, Wang Y (2005) The dual-specificity phosphatase CDC14B bundles and stabilizes microtubules. Mol Cell Biol 25: 4541–4551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CH, Good VM, Tonks NK, Barford D (2003) The structure of the cell cycle protein Cdc14 reveals a proline-directed protein phosphatase. EMBO J 22: 3524–3535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspersen SL, Charles JF, Morgan DO (1999) Inhibitory phosphorylation of the APC regulator Hct1 is controlled by the kinase Cdc28 and the phosphatase Cdc14. Curr Biol 9: 227–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamura T, Hara T, Matsumoto M, Ishida N, Okumura F, Hatakeyama S, Yoshida M, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI (2004) Cytoplasmic ubiquitin ligase KPC regulates proteolysis of p27(Kip1) at G1 phase. Nat Cell Biol 6: 1229–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Herbst A, Tworkowski KA, Salghetti SE, Tansey WP (2003) Skp2 regulates Myc protein stability and activity. Mol Cell 11: 1177–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossatz U, Dietrich N, Zender L, Buer J, Manns MP, Malek NP (2004) Skp2-dependent degradation of p27kip1 is essential for cell cycle progression. Genes Dev 18: 2602–2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer ER, Scheuringer N, Podtelejnikov AV, Mann M, Peters JM (2000) Mitotic regulation of the APC activator proteins CDC20 and CDH1. Mol Biol Cell 11: 1555–1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Ljungman M, Dixon JE (2000) The human Cdc14 phosphatases interact with and dephosphorylate the tumor suppressor protein p53. J Biol Chem 275: 2410–2414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlepage LE, Ruderman JV (2002) Identification of a new APC/C recognition domain, the A box, which is required for the Cdh1-dependent destruction of the kinase Aurora-A during mitotic exit. Genes Dev 16: 2274–2285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailand N, Diffley JF (2005) CDKs promote DNA replication origin licensing in human cells by protecting Cdc6 from APC/C-dependent proteolysis. Cell 122: 915–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailand N, Lukas C, Kaiser BK, Jackson PK, Bartek J, Lukas J (2002) Deregulated human Cdc14A phosphatase disrupts centrosome separation and chromosome segregation. Nat Cell Biol 4: 317–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek NP, Sundberg H, McGrew S, Nakayama K, Kyriakides TR, Roberts JM (2001) A mouse knock-in model exposes sequential proteolytic pathways that regulate p27Kip1 in G1 and S phase. Nature 413: 323–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray AW (2004) Recycling the cell cycle: cyclins revisited. Cell 116: 221–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Nagahama H, Minamishima YA, Miyake S, Ishida N, Hatakeyama S, Kitagawa M, Iemura S, Natsume T, Nakayama KI (2004) Skp2-mediated degradation of p27 regulates progression into mitosis. Dev Cell 6: 661–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama KI, Nakayama K (2006) Ubiquitin ligases: cell-cycle control and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 6: 369–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM (2006) The anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome: a machine designed to destroy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 644–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rape M, Reddy SK, Kirschner MW (2006) The processivity of multiubiquitination by the APC determines the order of substrate degradation. Cell 124: 89–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SI (2003) Ratchets and clocks: the cell cycle, ubiquitylation and protein turnover. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 855–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Mahavisno V, Varambally R, Yu J, Briggs BB, Barrette TR, Anstet MJ, Kincead-Beal C, Kulkarni P, Varambally S, Ghosh D, Chinnaiyan AM (2007) Oncomine 3.0: genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18 000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia 9: 166–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodier G, Makris C, Coulombe P, Scime A, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI, Meloche S (2005) p107 inhibits G1 to S phase progression by down-regulating expression of the F-box protein Skp2. J Cell Biol 168: 55–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito RM, Perreault A, Peach B, Satterlee JS, van den Heuvel S (2004) The CDC-14 phosphatase controls developmental cell-cycle arrest in C.elegans. Nat Cell Biol 6: 777–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmento LM, Huang H, Limon A, Gordon W, Fernandes J, Tavares MJ, Miele L, Cardoso AA, Classon M, Carlesso N (2005) Notch1 modulates timing of G1–S progression by inducing SKP2 transcription and p27 Kip1 degradation. J Exp Med 202: 157–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ, Roberts JM (1999) CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev 13: 1501–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmeier F, Amon A (2004) Closing mitosis: the functions of the Cdc14 phosphatase and its regulation. Annu Rev Genet 38: 203–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutterluty H, Chatelain E, Marti A, Wirbelauer C, Senften M, Muller U, Krek W (1999) p45SKP2 promotes p27Kip1 degradation and induces S phase in quiescent cells. Nat Cell Biol 1: 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco D, Lukas J, Reed SI (2002) The pRb-related protein p130 is regulated by phosphorylation-dependent proteolysis via the protein-ubiquitin ligase SCF(Skp2). Genes Dev 16: 2946–2957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Lamond AI (2006) Mitotic phosphatases: no longer silent partners. Curr Opin Cell Biol 18: 623–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetkov LM, Yeh KH, Lee SJ, Sun H, Zhang H (1999) p27(Kip1) ubiquitination and degradation is regulated by the SCF(Skp2) complex through phosphorylated Thr187 in p27. Curr Biol 9: 661–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Lehr N, Johansson S, Wu S, Bahram F, Castell A, Cetinkaya C, Hydbring P, Weidung I, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI, Soderberg O, Kerppola TK, Larsson LG (2003) The F-box protein Skp2 participates in c-Myc proteosomal degradation and acts as a cofactor for c-Myc-regulated transcription. Mol Cell 11: 1189–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Liu D, Wang Y, Qin J, Elledge SJ (2001) Pds1 phosphorylation in response to DNA damage is essential for its DNA damage checkpoint function. Genes Dev 15: 1361–1372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Ayad NG, Wan Y, Zhang GJ, Kirschner MW, Kaelin WG Jr (2004) Degradation of the SCF component Skp2 in cell-cycle phase G1 by the anaphase-promoting complex. Nature 428: 194–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirbelauer C, Sutterluty H, Blondel M, Gstaiger M, Peter M, Reymond F, Krek W (2000) The F-box protein Skp2 is a ubiquitylation target of a Cul1-based core ubiquitin ligase complex: evidence for a role of Cul1 in the suppression of Skp2 expression in quiescent fibroblasts. EMBO J 19: 5362–5375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam CH, Ng RW, Siu WY, Lau AW, Poon RY (1999) Regulation of cyclin A-Cdk2 by SCF component Skp1 and F-box protein Skp2. Mol Cell Biol 19: 635–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki L, Pagano M (2004) Cell cycle, proteolysis and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol 16: 623–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1–8