Abstract

Detailed data on the distribution of Veillonella in caries-free and caries-active subjects are scarce. We hypothesized that the diversity of the genus would be lower in caries lesions than in plaque from caries-free individuals. The proportions of Veillonella were not significantly different in the two groups. All isolates (n = 1308) were genotyped by REP-PCR, and different genotypes (n = 170) were identified by 16S rRNA, dnaK, and rpoB sequencing. V. parvula, V. dispar, and V. atypica were in both groups, V. denticariosi only in caries lesions, and V. rogosae only from the caries-free individuals (p < 0.009). Lesions were more likely to harbor a single predominant species (p = 0.0018). The mean number of genotypes in the lesions was less than in the fissure (p < 0.001) or buccal (p = 0.011) sites. The Veillonella from caries-free sites were more diverse than those from caries lesions, and may be related to the acidic environment of caries lesions.

Keywords: caries, genotype, diversity, oral biofilm, Veillonella spp.

INTRODUCTION

The genus Veillonella is a member of the normal oral flora (Mager et al., 2003) and consists of 8 validly published species: Veillonella criceti, Veillonella ratti, Veillonella rodentium, and Veillonella caviae from rodents; and Veillonella parvula, Veillonella atypica, Veillonella dispar, Veillonella montpellierensis (Mays et al., 1982; Jumas-Bilak et al., 2004), and Veillonella denticariosi (Byun et al., 2007) from humans. We have also recently described a new species of Veillonella, V. rogosae, isolated from human dental plaque (Arif et al., 2008). The intra-oral distribution of Veillonella correlates with their binding to specific members of the oral flora (Hughes et al., 1988); however, their requirement for fatty acids (Delwiche et al., 1985) may also influence their distribution. It has been suggested that, since Veillonella metabolize lactate and succinate, they may be present in increased numbers in caries lesions, and their metabolism of lactate may ameliorate the caries process (Mikx et al., 1972; van der Hoeven et al., 1978). Veillonella are relatively easily identified to the genus level, but, since there are no characteristic phenotypic reactions (Kolenbrander and Moore, 1992), the identification of isolates to the species level requires molecular methods based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing, in conjunction with sequence analysis of housekeeping genes, including dnaK and rpoB (Jumas-Bilak et al., 2004; Byun et al., 2007).

There are no reliable reports of the species and genotypic diversity of Veillonella spp. at different intra-oral sites. We have therefore identified Veillonella spp. from occlusal caries lesions in children, and from fissure and buccal tooth surfaces in caries-free children, using 16S rRNA, dnaK, and rpoB partial gene sequencing, as well as repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (REP-PCR) to genotype isolates (Versalovic et al., 1991; Alam et al., 1999). Analysis of these data enabled the distribution and diversity of Veillonella spp. and genotypes in active occlusal caries lesions, which have a typical pH of 4.9 (Hojo et al., 1994), to be compared with the diversity of Veillonella spp. from caries-free sites in children. We will test the hypothesis that, in the acidic environment of the caries lesions, species and genotypes best able to exploit the changed environment proliferate (Bowden and Hamilton, 1998), resulting in decreased diversity.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Participants

The participants attended Guy's Hospital London, and the children or their caregivers gave consent to the collection of the samples. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Ref. 02/11/10). The caries-active group consisted of nine children with at least 2 active dentinal coronal caries lesions, a mean age of 4.2 ± 0.53 yrs, and a mean number of decayed, missing, and filled teeth (WHO, 1979) of 10.3 (range, 5-19). The caries-free group consisted of nine children with a mean age of 6.3 ± 1.1 yrs.

Sample Collection

The superficial plaque above the infected dentin was removed and the dentinal color and consistency noted (Kidd et al., 1993). Samples were collected, with the use of a sterile dental excavator, from 2 lesions in each child. Plaque samples were collected from the sound occlusal surface of 1 first molar tooth and from the buccal surface of the same tooth with the use of sterile dental excavators. We assessed the caries status of the sampled sites visually, to determine the Ekstrand score (Ekstrand et al., 1998), and using DIAGNOdent (KaVo, Amersham, Bucks., UK). Each sample was transferred into 1 mL of Fastidious Anaerobe Broth (LabM Ltd., Bury, Lancs., UK) and stored on ice.

Microbiological Processing

The numbers of cultivable bacteria, yeasts, lactobacilli, and mutans streptococci in each sample were determined (Beighton et al., 1993). Veillonella spp. were isolated on Veillonella agar (Rogosa, 1956), and we determined the number of presumptive Veillonella in each sample by counting typical colonies. From each sample, up to 48 presumptive Veillonella spp. were subcultured onto Fastidious Anaerobe Agar (LabM) supplemented with 5% (v/v) horse blood and grown anaerobically for 48 hrs.

Genotyping of Isolates

All presumptive Veillonella spp. were genotyped by REP-PCR (Alam et al., 1999). Isolates were considered identical if they were ≥ 95% similar. On the basis of these analyses, 2 isolates of each genotype, and individual genotypes (n = 170), were further characterized.

Identification of Isolates

To confirm that the isolates were Veillonella, we extracted DNA by boiling cell suspensions, then amplified 16S rRNA using primers 27f and 1492r (Lane, 1991), and sequenced with the 27f primer using the Big Dye Ready Reaction Termination Mix (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA). Each sequence was submitted to the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP, http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/) via the Sequence Match routine, aligned by CLUSTAL W (Thompson et al., 1997) in Bioedit (www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/page2.html), and a phylogenetic tree was formed using DNAdist with the Jukes-Cantor model (Saitou and Nei, 1987), with 16S rRNA sequences of type strains included. The majority of isolates were not identified; therefore, partial dnaK sequences were determined with Veill-dnaKF - TATGGAAGGYGGCGAACC Veill-dnaKR - GCAGCRSTYAATGTTACATCC. The dnaK sequences were aligned and compared with the dnaK gene sequences of the Veillonella type strains (Jumas-Bilak et al., 2004). The majority of isolates were identified, but a small number remained unidentified and were subsequently identified on the basis of rpoB sequence analysis. The partial sequences of 16S rRNA and dnaK used for identification were obtained from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez. A section of the rpoB gene was amplified and sequenced with the following primers: Veill-rpoBF - GTAACAAAGGTGTCGTTTCTCG and Veill-rpoBR - GCACCRTCAAATACAGGTGTAGC. Sequence analysis of the resulting amplicons (608 nt) enabled these isolates to be identified as members of a new species, V. rogosae (Arif et al., 2008).

Statistical Analysis of Data

The numbers of each taxon were expressed as a percentage of the total anaerobic colony count, and comparisons were made between the proportions of these taxa at different sites. To normalize the number of genotypes observed, we expressed the data as number of genotypes per 100 isolates. Values were compared by the non-parametric tests, Kruskal-Wallis to identify the presence of significant differences within datasets, and Mann-Whitney to identify the differences (SPSSPC+), or with Fisher's exact test (http://www.matforsk.no/ola/fisher.htm).

RESULTS

Comparison of the Sites and the Oral Biota

The mean DIAGNOdent score of the caries-free sites was 1.1 ± 0.5 (range, 0-7). The caries lesions had Ekstrand scores of 4, while the caries-free scored 1. The carious dentin was recorded as soft (14/18) or medium, and the color of the dentin in these samples was recorded as pale or mid-brown. The mean proportions of mutans streptococci were 0.4 ± 1.0, 0.3 ± 0.7, and 20.2 ± 28.6 in the fissure plaque, buccal surface plaque, and caries lesion, respectively (p < 0.05), while for lactobacilli, yeasts, and Veillonella spp., the values were 0.3 ± 0.6, not detected, and 28.3 ± 35.3 (p < 0.05); not detected, 0.02 ± 0.07, and 0.6 ± 1.1 (p < 0.05); and p > 0.05, respectively. The frequency of recovery of each of these taxa was significantly (p < 0.05) higher from the caries lesions than from the other sites.

Identification of Veillonella spp.

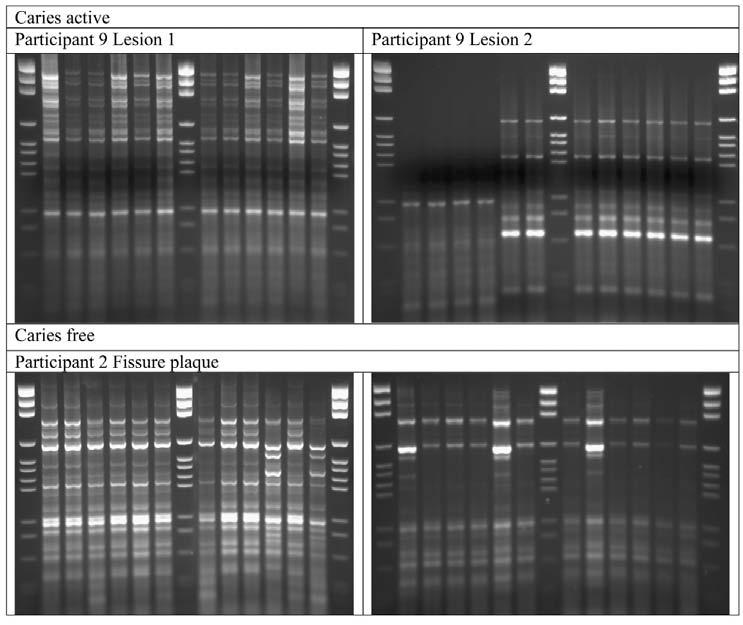

All of the presumptive Veillonella spp. isolates (n = 1308; see Tables 1 and 2 for site distribution) were genotyped by REP-PCR. Partial 16S rRNA sequences of 2 of each genotype were determined, and the majority (> 99.5%) was identified as Veillonella spp. Representative REP-PCR patterns of isolates from lesion and fissure plaque samples are shown in the Fig.

Table 1. Identification of Veillonella spp. and Genotype Assignment of Isolates from 18 Active Occlusal Caries Lesions in Nine Children (Genotypes are unique to an individual child.).

| No. of Isolates |

Genotype | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Site | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 1 | 46 | Lesion 1 | 46 | ||||||

| 48 | Lesion 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 39 | ||||

| IDa | P | P | P | P | |||||

| 2 | 48 | Lesion 1 | 9 | 39 | |||||

| 48 | Lesion 2 | 44 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| ID | P | A | A | A | D | A | |||

| 3 | 48 | Lesion 1 | 10 | 1 | 37 | ||||

| 47 | Lesion 2 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 29 | ||||

| ID | A | A | P | A | A | ||||

| 4 | 45 | Lesion 1 | 18 | 26 | 1 | ||||

| 48 | Lesion 2 | 22 | 2 | 24 | |||||

| ID | DC | DC | P | P | P | P | |||

| 5 | 48 | Lesion 1 | 48 | ||||||

| 48 | Lesion 2 | 48 | |||||||

| ID | P | P | |||||||

| 6 | 48 | Lesion 1 | 28 | 20 | |||||

| 48 | Lesion 2 | 48 | |||||||

| ID | P | P | |||||||

| 7 | 48 | Lesion 1 | 47 | 1 | |||||

| 48 | Lesion 2 | 48 | |||||||

| ID | DC | P | |||||||

| 8 | 48 | Lesion 1 | 46 | 2 | |||||

| 48 | Lesion 2 | 40 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| ID | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | ||

| 9 | 48 | Lesion 1 | 48 | ||||||

| 48 | Lesion 2 | 44 | 4 | ||||||

| ID | A | P | P | ||||||

ID, identification: A = V. atypica, D = V. dispar, DC = V. denticariosi, and P = V. parvula.

Table 2. Identification of Veillonella spp. and Genotype Assignment of Isolates from Fissure and Buccal Surface Plaque in Nine Caries-free Children (Genotypes are unique to an individual child.).

| Genotype | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | # Isolates | Site | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 1 | 30 | Fissure | 23 | 4 | 3 | ||||||||||

| 2 | Buccal | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| IDa | R | A | R | R | |||||||||||

| 2 | 24 | Fissure | 9 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||

| 24 | Buccal | 15 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| ID | P | P | D | P | P | P | D | P | R | ||||||

| 3 | 22 | Fissure | 8 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| 21 | Buccal | 1 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |||||||

| ID | P | P | R | R | P | P | P | D | D | P | P | P | P | ||

| 4 | 8 | Fissure | 3 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 48 | Buccal | 27 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| ID | P | D | A | P | D | D | P | A | P | P | |||||

| 5 | 43 | Buccal | 17 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ID | A | A | A | A | D | D | P | P | P | ||||||

| 6 | 47 | Fissure | 17 | 28 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 48 | Buccal | 48 | |||||||||||||

| ID | P | P | P | R | |||||||||||

| 7 | 31 | Buccal | 21 | 6 | 4 | ||||||||||

| ID | P | R | D | ||||||||||||

| 8 | 13 | Fissure | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| 48 | Buccal | 9 | 3 | 19 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| ID | R | R | A | R | R | R | R | R | |||||||

| 9 | 48 | Buccal | 27 | 6 | 15 | ||||||||||

| ID | P | P | P | ||||||||||||

ID, identification: A = V. atypica, D = V. dispar, DC = V. denticariosi, P = V. parvula, and R = V. rogosae.

Figure. Representative REP-PCR patterns obtained from 2 caries lesions in Participant 9 and from the fissure plaque from caries-free Participant 2. Lanes 1, 8, and 15 are marker lanes. Each of the other lanes represents a single isolate.

Isolates with the same genotype were identical by 16S rRNA, dnaK, and rpoB sequencing. From 3 fissure samples, no Veillonella were isolated. The proportion of Veillonella spp. recovered from lesions (6.4 ± 10.3) was not significantly different from the proportions of Veillonella spp. at the fissure or buccal sites, 5.6 ± 14.6 and 3.0 ± 5.3, respectively.

The partial 16s rRNA sequence data (from 170 isolates) permitted the identification of V. atypica (n = 28); the majority of isolates (n = 107) were in the parvula/dispar group, 6 were V. denticariosi, while 29 isolates were identified as V. rogosa. Analysis of the dnaK data supported the identification of the V. atypica and V. denticariosi and allowed the parvula/dispar group to be differentiated: 17 as V. dispar, and 90 as V. parvula. The DNA from the other 29 isolates could not be amplified with the dnaK primers, despite attempts to optimize the PCR conditions, but were amplified with the rpoB primers and identified, on the basis of sequence alignments, as V. rogosae.

Predominant Veillonella spp.

The genotyping data are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. A single species of Veillonella predominated (> 85% the same species) in 16 of the 18 caries lesions, while in only 7 of the 15 caries-free sites did a single species predominate (χ2 = 9.75; p = 0.0018). V. parvula were identified from every caries-active individual, V. atypica from three, V. dispar from one, V. dentocariosi from two, and the V. rogosae from none. For the caries-free group, the frequencies of isolation from nine persons, regardless of site, were 7, 3, 5, 0, and 6. The frequencies of isolation were not significantly different between the two groups, with the exception of V. rogosae (p = 0.009), while the difference in the frequency of isolation of V. dispar approached significance (p = 0.057). The predominant species recovered from the 2 caries lesions in each person were the same except in one person (Participant 9, Table 1).

Genotyping of Veillonella spp.

No children shared the same genotype. All Veillonella isolates were considered together in the first analysis of the genotypes present in the oral samples, since they all share the ability to utilize lactate for the production of energy. There was no difference between the number of genotypes (as genotypes per 100 isolates) in the 2 caries lesions in the same child (range, 2-14; median, 4), or between the number of genotypes in the fissure (range, 2-100; median, 21) and the buccal surface (range, 10-46; median, 23) samples. However, there were significantly more genotypes in the buccal surface plaque (p = 0.011) and the fissure plaque (p < 0.001) than in the caries lesions. V. parvula was isolated from the majority of participants, but there was no difference in its genotypic diversity between the caries-free and caries-active sites (p = 0.281).

DISCUSSION

We have identified the Veillonella spp. most commonly isolated from caries-active and caries-free children. The unique genotypes of Veillonella spp. in each independent child are similar to the situation reported for S. mutans (Li and Caufield, 1995) and S. oralis (Alam et al., 1999). The proportions of Veillonella spp. were not different from those reported in other cultural studies (Marsh and Martin, 1999). However, molecular studies give various and divergent results. Analysis of data from 5 caries lesions revealed that Veillonella spp. were infrequent isolates/clonal types from both the middle and advancing fronts of lesions (Munson et al., 2004), and Veillonella spp. were identified infrequently among 942 clones representing 75 species or phylotypes from 10 lesions (Chhour et al., 2005). In a reverse-capture checkerboard assay on pooled plaque samples, Veillonella spp. were found to be at highest numbers in the samples of carious dentin (Becker et al., 2002). It is likely that the data may reflect the sensitivity of the detection methods, the low numbers of lesions studied, and the absence of non-carious sites in the former two studies. However, the data reflect the growing understanding that each individual has his/her own combination of taxa (Diaz et al., 2006), and that while composition may vary, the function of the infecting biofilm within the lesion (acid production and consequent demineralization of tooth tissues) remains similar.

Veillonella spp. utilize lactate (Delwiche et al., 1985), which may ameliorate the caries process, but data from rat model systems have been ambiguous, with less caries occurring when rats were co-infected with S. mutans and V. alcalescens than when they were infected with S. mutans alone in one study, but not another (Mikx et al., 1972; van der Hoeven et al., 1978). Cultural studies (Toi et al., 1999) have also suggested a high level of correlation between the numbers of Veillonella and the numbers of lactobacilli, mutans streptococci, and Actinomyces spp., organisms that ferment carbohydrates to lactate. Analysis of other data supports the hypothesis that Veillonella will utilize lactate produced by S. mutans when they are co-cultured, resulting in higher yields of both organisms and lower concentrations of lactate (Mikx and van der Hoeven, 1975), while others found higher lactate concentrations from mixed cultures of V. alcalescens and S. mutans (Noorda et al., 1988). Analysis of these data suggests that strain-specific properties may be important, while that of the data from the present study also suggests that the disease status of the site from which the organism is isolated might influence its physiology, as is the case with non-mutans streptococci (van Houte et al., 1991). Heterogeneity between members of the same Veillonella spp. has also been suggested, on the basis of interactions with polyclonal antibody and co-aggregation abilities (Palmer et al., 2006).

The identification of Veillonella spp. is difficult, since there are no useful differential phenotypic tests (Kolenbrander et al., 1992). An RFLP method for distinguishing Veillonella spp. has been reported (Sato et al., 1997), but does not include either V. montpellierensis or V. denticariosi and will need re-evaluation. For many years, most isolates were reported as V. alcalescens, but the species name “alcalescens” is no longer valid (Rogosa, 1984). The identification of Veillonella has been facilitated by the use of 16S rRNA sequencing in conjunction with dnaK (Jumas-Bilak et al., 2004) or rpoB sequencing (Byun et al., 2007). We successfully used this approach to identify Veillonella spp., but sequence analysis of rpoB was required for the identification of V. rogosae. We have used REP-PCR to genotype Veillonella spp., and the high level of diversity among the strains from the caries-free sites is similar to that reported for other commensal oral species, including S. oralis (Alam et al., 1999) and Fusobacterium nucleatum (Haraldsson et al., 2004). We also demonstrated that the genus was less diverse within the lesions, and that lesions had a single predominant species significantly more often than did plaque samples from caries-free children. These diversity data complement genetic profiling data (Li et al., 2007) demonstrating that the microbiota of the dental plaque taken from children with early childhood caries was less complex than the microbiota of plaque from caries-free children. The simplification of the Veillonella flora in the caries lesions suggests that there has been a selective process in which only the “fittest” species or strains were able to proliferate and survive in the lesions, as predicted previously (Bowden and Hamilton, 1998). This result may reflect on the inability of individual Veillonella strains and species to proliferate and survive in the acidic environment of the caries lesion; clearly, mutans streptococci, lactobacilli, and yeasts proliferated. The basis of the selection is not known; the REP-PCR patterns are a surrogate marker for phenotypic diversity, and not the basis for survival. Studies of soils have also shown that bacterial diversity is related to the pH of the soil type, with greatest diversity in soils around neutrality and reduced diversity as the soil pH becomes more acidic (Fierer and Jackson, 2006).

We have investigated the predominant Veillonella spp. in the dental plaque of children and used REP-PCR to demonstrate that the diversity of Veillonella spp. was less within the lesion than in the oral biofilm of caries-free persons.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the KCL Dental Institute and the Wellcome Trust (Ref:076381). Dr. Roy Byun, Westmead Centre for Oral Health, Australia, provided the rpoB primer sequences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an Open Access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/ , which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

REFERENCES

- Alam S, Brailsford SR, Whiley RA, Beighton D. PCR-based methods for genotyping viridans group streptococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2772–2776. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.2772-2776.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arif A, Do T, Byun R, Sheehy E, Clark D, Gilbert SC, et al. Veillonella rogosae sp. nov., an anaerobic Gram-negative coccus isolated from dental plaque. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58:581–584. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65093-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MR, Paster BJ, Leys EJ, Moeschberger ML, Kenyon SG, Galvin JL, et al. Molecular analysis of bacterial species associated with childhood caries. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1001–1009. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.3.1001-1009.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beighton D, Lynch E, Heath MR. A microbiological study of primary root-caries lesions with different treatment needs. J Dent Res. 1993;72:623–629. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720031201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden GHW, Hamilton IR. Survival of oral bacteria. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:54–85. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090010401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun R, Carlier J-P, Jacques NA, Marchandin H, Hunter N. Veillonella denticariosi sp. nov., isolated from human carious dentine. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:2844–2848. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhour KL, Nadkarni MA, Byun R, Martin FE, Jacques NA, Hunter N. Molecular analysis of microbial diversity in advanced caries. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:843–849. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.843-849.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delwiche EA, Pestka JJ, Tortorello ML. The Veillonellae: Gram-negative cocci with a unique physiology. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1985;39:175–193. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.39.100185.001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz PI, Chalmers NI, Rickard AH, Kong C, Milburn CL, Palmer RJ, Jr, et al. Molecular characterization of subject-specific oral microflora during initial colonization of enamel. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2837–2848. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2837-2848.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand KR, Ricketts DN, Kidd EA, Qvist V, Schou S. Detection, diagnosing, monitoring and logical treatment of occlusal caries in relation to lesion activity and severity: an in vivo examination with histological validation. Caries Res. 1998;32:247–254. doi: 10.1159/000016460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierer N, Jackson RB. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:626–631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507535103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraldsson G, Holbrook WP, Könönen E. Clonal persistence of oral Fusobacterium nucleatum in infancy. J Dent Res. 2004;83:500–504. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojo S, Komatsu M, Okuda R, Takahashi N, Yamada T. Acid profiles and pH of carious dentin in active and arrested lesions. J Dent Res. 1994;73:1853–1857. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730121001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CV, Kolenbrander PE, Andersen RN, Moore LV. Coaggregation properties of human oral Veillonella spp.: relationship to colonization site and oral ecology. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1957–1963. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.1957-1963.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumas-Bilak E, Carlier JP, Jean-Pierre H, Teyssier C, Gay B, Campos J, et al. Veillonella montpellierensis sp. nov., a novel, anaerobic, Gram-negative coccus isolated from human clinical samples. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:1311–1316. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02952-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd EAM, Joyston-Bechal S, Beighton D. Microbiological validation of assessments of caries activity during cavity preparation. Caries Res. 1993;27:402–408. doi: 10.1159/000261571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolenbrander PE, Moore LVH. The genus Veillonella. In: Balows HG, Trüper M, Dworkin W, Harder W, Schleife K-H, editors. The prokaryotes. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 1992. pp. 2034–2047. [Google Scholar]

- Lane DJ. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Caufield PW. The fidelity of initial acquisition of mutans streptococci by infants from their mothers. J Dent Res. 1995;74:681–685. doi: 10.1177/00220345950740020901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Ge Y, Saxena D, Caufield PW. Genetic profiling of the oral microbiota associated with severe early-childhood caries. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:81–87. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01622-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager DL, Ximenez-Fyvie LA, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Distribution of selected bacterial species on intraoral surfaces. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:644–654. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh PD, Martin MV. Oral microbiology. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Wright; 1999. pp. 58–81. [Google Scholar]

- Mays TD, Holdeman LV, Moore WEC, Rogosa M, Johnson JL. Taxonomy of the genus Veillonella Prévot. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1982;32:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mikx FH, van der Hoeven JS. Symbiosis of Streptococcus mutans and Veillonella alcalescens in mixed continuous cultures. Arch Oral Biol. 1975;20:407–410. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(75)90224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikx FH, van der Hoeven JS, König KG, Plasschaert AJ, Guggenheim B. Establishment of defined microbial ecosystems in germ-free rats. I. The effect of the interactions of Streptococcus mutans or Streptococcus sanguis with Veillonella alcalescens on plaque formation and caries activity. Caries Res. 1972;6:211–223. doi: 10.1159/000259801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson MA, Banerjee A, Watson TF, Wade WG. Molecular analysis of the microflora associated with dental caries. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3023–3029. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3023-3029.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noorda WD, Purdell-Lewis DJ, van Montfort AM, Weerkamp AH. Monobacterial and mixed bacterial plaques of Streptococcus mutans and Veillonella alcalescens in an artificial mouth: development, metabolism, and effect on human dental enamel. Caries Res. 1988;22:342–347. doi: 10.1159/000261134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RJ, Jr, Diaz PI, Kolenbrander PE. Rapid succession within the Veillonella population of a developing human oral biofilm in situ. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:4117–4124. doi: 10.1128/JB.01958-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogosa M. A selective medium for the isolation and enumeration of the Veillonella from the oral cavity. J Bacteriol. 1956;72:533–536. doi: 10.1128/jb.72.4.533-536.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogosa M. Anaerobic Gram-negative cocci. In: Krieg NR, Holt JG, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1984. pp. 680–685. [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Matsuyama J, Sato M, Hoshino E. Differentiation of Veillonella atypica, Veillonella dispar and Veillonella parvula using restricted fragment-length polymorphism analysis of 16S rDNA amplified by polymerase chain reaction. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1997;12:350–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1997.tb00737.x. erratum in Oral Microbiol Immunol 13:193, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toi CS, Cleaton-Jones PE, Daya NP. Mutans streptococci and other caries-associated acidogenic bacteria in five-year-old children in South Africa. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1999;14:238–243. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.1999.140407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoeven JS, Toorop AI, Mikx FH. Symbiotic relationship of Veillonella alcalescens and Streptococcus mutans in dental plaque in gnotobiotic rats. Caries Res. 1978;12:142–147. doi: 10.1159/000260324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Houte J, Sansone C, Joshipura K, Kent R. Mutans streptococci and non mutans streptococci acidogenic at low pH, and in vitro acidogenic potential of dental plaque in two different areas of the human dentition. J Dent Res. 1991;70:1503–1507. doi: 10.1177/00220345910700120601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versalovic J, Koeuth T, Lupski JR. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6823–6831. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . Guide to oral health epidemiology investigations. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1979. [Google Scholar]