Abstract

Surfactant protein-A (SP-A) gene expression in human fetal lung type II cells is stimulated by cAMP and IL-1 and is inhibited by glucocorticoids. cAMP/IL-1 stimulation of SP-A expression is mediated by increased binding of thyroid transcription factor-1 and nuclear factor (NF)-κB to the TTF-1-binding element (TBE) in the SP-A promoter. This is associated with decreased expression of histone deacetylases (HDACs), increased recruitment of coactivators, and enhanced acetylation of histone H3 (K9,14) at the TBE. In the present study, endogenous glucocorticoid receptor (GR) was found to interact with thyroid transcription factor-1 and NF-κB p65 at the TBE. GR knockdown enhanced SP-A expression in type II cells cultured in serum-free medium, suggesting a ligand-independent inhibitory role of endogenous GR. Furthermore, use of chromatin immunoprecipitation revealed that dexamethasone (Dex) treatment of fetal lung type II cells increased recruitment of endogenous GR and HDACs-1 and -2 and blocked cAMP-induced binding of inhibitor of κB kinase-α (IKKα) to the TBE region. Accordingly, Dex reduced basal and blocked cAMP-stimulated levels of acetylated (K9,14) and phosphorylated (S10) histone H3 at the TBE. Dex also increased TBE binding of dimethylated histone H3 (K9) and of heterochromatin protein 1α. Thus, Dex increases interaction of GR with the complex of proteins at the TBE. This facilitates recruitment of HDACs and causes a local decline in basal and cAMP-induced histone H3 phosphorylation and acetylation and an associated increase in H3-K9 dimethylation and binding of heterochromatin protein 1α. Collectively, these events may culminate in the closing of chromatin structure surrounding the SP-A gene and inhibition of its transcription.

SURFACTANT PROTEIN-A (SP-A), the major lung surfactant protein, is expressed in type II cells and is developmentally regulated in fetal lung (see Ref. 1 for review). SP-A, a member of the collectin subfamily of C-type lectins, plays an important role in innate immunity within the lung alveolus (2). Augmented SP-A secretion by the fetal lung into amniotic fluid near term may also play a role in the migration of fetal macrophages to the maternal uterus and the ensuing uterine inflammatory response leading to the initiation of labor (3). SP-A expression in cultured human fetal lung type II cells is markedly stimulated by hormones and factors that increase cAMP (4,5) and by IL-1 (6) and is inhibited by dexamethasone (Dex) acting through the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) (7,8). cAMP and IL-1 stimulation of SP-A expression is O2 dependent (6,9,10) and mediated by increased binding of thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1/Nkx2.1) and nuclear factor (NF)-κB (p65/p50) to a critical response element (TBE) 183 bp upstream of the SP-A transcription start site (6,10). By contrast, Dex has a pronounced effect to inhibit NF-κB activation, type II cell nuclear protein binding to the TBE, and the induction of SP-A gene transcription (8).

Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), we previously observed that when type II cells were cultured in a 20% O2 environment, cAMP and IL-1 stimulated recruitment of TTF-1, NF-κB, and coactivators with histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity [e.g. cAMP response element-binding protein-binding protein (CBP) and steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1)] to the TBE region of the SP-A promoter. This was associated with increased local acetylation of histone H3 (K9,14) (10). On the other hand, these effects of cAMP and IL-1 were prevented when the type II cells were cultured in a hypoxic environment (10). Culture of type II cells under hypoxic conditions also resulted in increased expression of histone deacetylases (HDACs), with enhanced levels and binding of dimethyl histone H3 (K9,14) to the TBE region of the SP-A promoter (10). Moreover, we found that the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A and the methyltransferase inhibitor 5′-deoxy-5′-(methylthio) adenosine (d-MTA) increased SP-A expression in type II cells (10).

As mentioned, we observed that Dex inhibited the binding of type II cell nuclear proteins to the TBE and blocked the stimulatory effect of cAMP on TBE-binding activity. The finding that Dex increased expression of the NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα, in type II cells revealed a possible mechanism for its action to block NF-κB activation and translocation to the nucleus (8). Our findings further suggested that the inhibitory actions of Dex on SP-A expression were not mediated by direct binding of GR to a response element adjacent to the SP-A promoter. Rather, these effects were likely mediated via GR inhibition of TTF-1 and NF-κB transcriptional activity at the TBE (8).

There is abundant evidence to indicate that glucocorticoids exert their antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive actions through antagonism of NF-κB and activating protein-1 (AP-1) transcriptional activity (11,12) and that this transrepression is mediated, in part, by direct protein-protein interaction/tethering of GR to these proinflammatory transcriptional activators (13). It is, therefore, likely that the mechanism of GR repression of SP-A may also involve the tethering of GR to TTF-1 and/or NF-κB bound to the TBE. However, the mechanism involved in this form of transrepression is not well defined. Notably, it has been reported that glucocorticoids increase recruitment of HDAC2 to the complex of coactivators at the NF-κB response element of the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) promoter in lung A549 cells (14,15) and that deacetylation of GR is required for its interaction with the NF-κB complex (16).

The present study was undertaken to further define the mechanisms whereby glucocorticoids acting through the GR inhibit basal and cAMP-induced SP-A expression in human fetal lung type II cells. Our findings suggest that endogenous GR exerts both ligand-dependent and -independent suppressive effects on SP-A expression via its interaction with NF-κB p65 and TTF-1 bound to the TBE. Dex/GR suppression of SP-A was found to be associated with increased expression and recruitment of HDACs 1 and 2, an associated decrease in levels of acetylated and increase in levels of dimethylated histone H3 (K9) at the TBE region of the SP-A promoter. Increased H3-K9 dimethylation in Dex-treated type II cells also was coupled with increased expression and recruitment to the TBE of heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1). Interestingly, in addition to the previously reported effect of cAMP to increase levels of acetylated H3 (K9,14) at the TBE (10), we presently observed that cAMP treatment markedly induced levels of phosphorylated histone H3 (S10) at the TBE, and this was antagonized by Dex. The stimulatory effects of cAMP and inhibitory effects of Dex on H3 phosphorylation were coupled with comparable actions on recruitment of the NF-κB-activating kinase, inhibitor of κB kinase α (IKKα). Because H3-S10 phosphorylation appears to be requisite for H3-K14 acetylation, these intriguing findings suggest that the opposing effects of cAMP and glucocorticoids on SP-A expression in lung type II cells may be mediated in part through IKKα.

RESULTS

Endogenous GR Exerts an Inhibitory Effect on SP-A Gene Expression in Human Fetal Lung Type II Cells

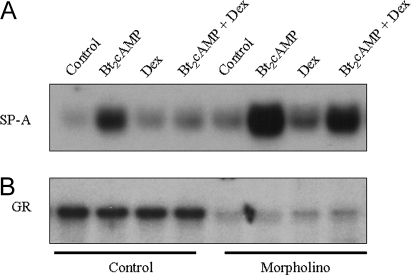

Previously, we observed using primary cultures of rat type II cells that overexpression of human GR (hGR) in the presence of Dex blocked cAMP stimulation of SP-A promoter activity while enhancing expression of the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter, a known GR target gene (8). To analyze the inhibitory role of endogenous GR on SP-A expression, we transfected human lung type II cells with morpholino antisense oligonucleotides to the hGR. Fetal lung type II cells were incubated with GR-morpholino oligo (GR-MO), which blocks translation of endogenous GR, or with control morpholino oligonucleotide. The transfected cells were cultured in the absence or presence of dibutyryl cAMP (Bt2cAMP) or Dex, added alone or in combination, for 48 h. As can be seen in Fig. 1A, knockdown of GR expression in fetal lung type II cells enhanced SP-A protein levels in all treatment conditions, as compared with cells treated with control oligonucleotide. GR knockdown by GR-MO treatment was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 1B). The finding that GR knockdown increased SP-A expression in the absence of Dex treatment suggests that endogenous GR plays a ligand-independent inhibitory role in SP-A gene expression.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of GR Expression by Morpholino Antisense Oligonucleotide Enhances SP-A Gene Expression in Human Fetal Lung Type II Cells

Fetal lung type II cells were cultured overnight in serum-free medium, followed by incubation with 10 μm GR-MO or control morpholino oligo and 10 μl/ml Endo-porter with or without Bt2cAMP, Dex, or the two agents in combination for 48 h. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were analyzed for protein levels of SP-A (A) and GR (B), respectively, by immunoblotting. Shown is a representative immunoblot of an experiment that was repeated twice with comparable results.

Dex Induces in Vivo Recruitment of GR to the TBE-Containing Region of the hSP-A Gene in Fetal Lung Type II Cells

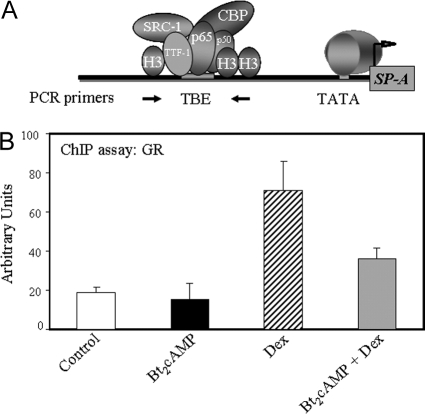

As mentioned, the inhibitory effect of Dex/GR on SP-A gene expression in lung type II cells was previously found to be exerted through the TBE (8), which binds TTF-1 and NF-κB (6). To determine the effects of Dex on in vivo recruitment of GR to the TBE-containing region of the SP-A promoter in human fetal type II cells, ChIP assays were carried out using antibody to hGR. Quantitative (Q)-PCR was used to amplify a 75-bp genomic region surrounding the TBE (Fig. 2A). Type II cells were cultured in the absence or presence of Bt2cAMP or Dex, added alone or in combination, for 48 h. As can be seen, Dex stimulated recruitment of GR to the TBE-containing region as compared with cells cultured in control medium or in medium containing cAMP (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, this stimulatory effect of Dex was antagonized by coincubation with Bt2cAMP. Levels of immunoreactive GR bound to the TBE region in untreated cells were essentially undetectable, because they did not differ from the IgG control (data not shown). These findings indicate that Dex promotes in vivo binding of GR to the TBE region upstream of the hSP-A gene.

Figure 2.

Recruitment of GR to the TBE of the hSP-A Gene in Fetal Lung Type II Cells Is Increased by Dex Treatment

Type II cells were cultured for 24 h in serum-free control medium and then incubated for another 48 h in the absence or presence of Bt2cAMP (1 mm), Dex (100 nm), or the two agents in combination. The cells were then treated with 1% formaldehyde and subjected to ChIP analysis of GR binding to a 75-bp region surrounding the TBE by Q-PCR using primers indicated by the arrows (A). The ChIP experiment shown in B is representative of four independent experiments that yielded comparable results. The data are expressed as arbitrary units. The bars represent the means ± sem of values from three sets of culture dishes.

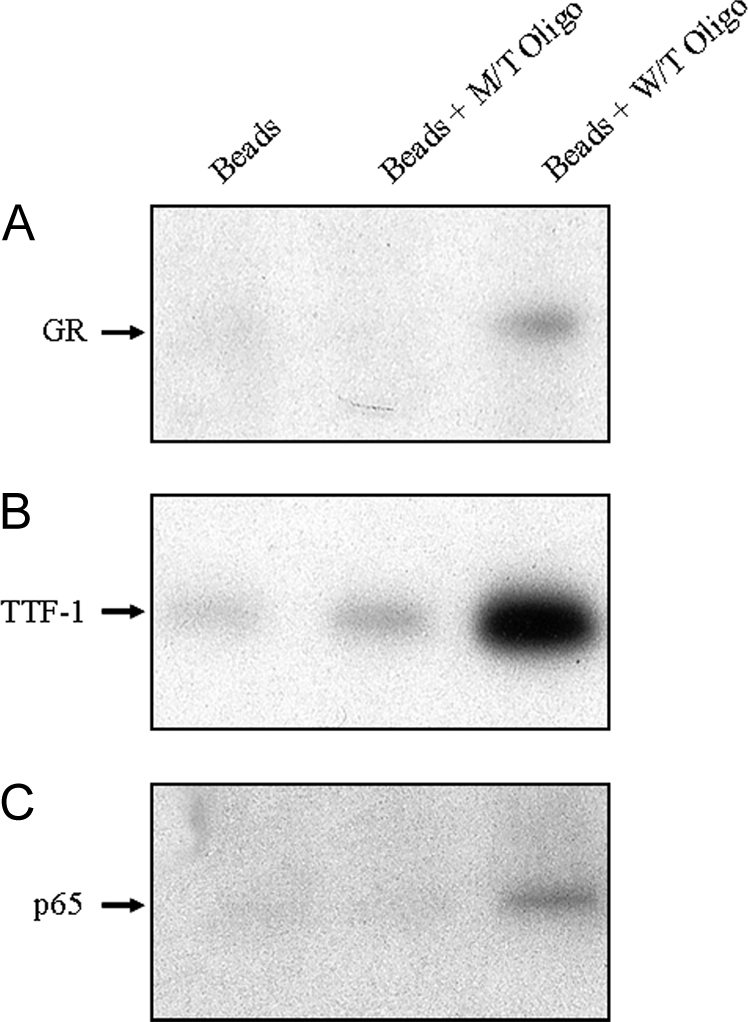

GR Interacts with TTF-1 and NF-κB p65 at the TBE of the hSP-A Gene

GR is known to interact physically with NF-κB p65 (17,18). Furthermore, we previously observed that p65 interacts with TTF-1 in type II cell nuclear extracts, and that both TTF-1 and NF-κB proteins bind to the TBE (6). To determine whether GR has the ability to interact with TTF-1 and NF-κB at the TBE, we used a DNA-affinity precipitation assay (DAPA) using nuclear extracts from human fetal type II cells cultured with Bt2cAMP for 48 h. The nuclear extracts were incubated with biotinylated 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotides corresponding to the wild-type oligo or mutant oligo hSP-A TBE. Avidin-precipitated protein complexes were resolved on 4–12% bis-tris gels, followed by immunoblotting using antibodies to GR, TTF-1, and p65. As can be seen in the immunoblot in Fig. 3, TTF-1, p65, and GR interacted at markedly higher levels with the WT TBE oligonucleotide, as compared with the mutated oligo or with the beads alone. Although endogenous TTF-1 appeared to bind most intensely, it is important to note that nuclear levels of TTF-1 appear to be considerably higher than those of GR and p65 (our unpublished observations).

Figure 3.

GR Interacts with TTF-1 and p65 in Human Fetal Lung Type II Cell Nuclei at the TBE

Nuclear extracts (75 μg) isolated from human fetal lung type II cells cultured in medium containing Bt2cAMP for 48 h were subjected to a DAPA using 5′ biotin end-labeled oligonucleotides corresponding to the wild type hSP-A TBE (WT oligo) or mutant (MT oligo). This TBE mutation was found previously to prevent TTF-1 stimulation of SP-A promoter activity (58,59). The oligos were incubated with nuclear extracts, and the avidin-precipitated protein complexes were resolved on SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting using antibodies to GR (A), TTF-1 (B), or p65 (C). Shown is an autoradiogram of an immunoblot from an experiment that was repeated twice with similar results.

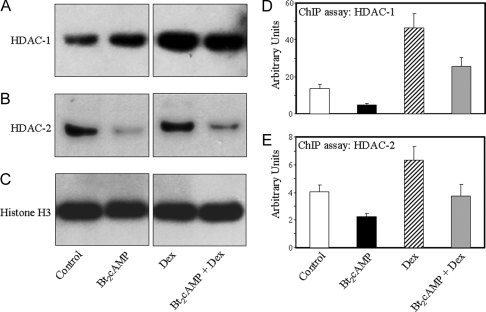

Dex Increases Nuclear Levels of HDAC-1 and -2 Proteins in Human Fetal Lung Type II Cells and Enhances Their Recruitment to the TBE Region of the SP-A Gene

As noted above, glucocorticoids were reported to increase recruitment of HDAC-2 to the NF-κB response element of the GM-CSF promoter in lung adenocarcinoma cells (14,15). It was, therefore, of interest to analyze the effects of Dex on nuclear levels of HDACs and on recruitment to the TBE. Human fetal lung type II cells were cultured for 48 h in the absence or presence of Bt2cAMP or Dex, added alone or in combination; nuclear extracts were analyzed for levels of HDAC-1 and -2 by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 4, A and B, nuclear levels of HDAC-1 and -2 were increased by Dex treatment, whereas levels of total histone H3 were unaffected (Fig. 4C). To analyze the effects of Dex on recruitment of HDACs to the TBE, we performed ChIP analysis of type II cells cultured for 48 h under the same conditions. As can be seen, Bt2cAMP inhibited, whereas Dex stimulated, recruitment of HDAC-1 (Fig. 4D) and -2 (Fig. 4E) to the SP-A genomic region containing the TBE. Furthermore, Bt2cAMP appeared to antagonize the stimulatory effects of Dex on HDAC recruitment. These findings suggest that Dex/GR may inhibit SP-A gene expression through induction of histone deacetylases and their increased binding to the TBE. This appeared to be specific for the TBE, because no effects of Dex on binding of HDACs to a 56-bp genomic region containing an E-box at approximately −39 bp were apparent.

Figure 4.

Dex Increases Nuclear Levels and in Vivo Binding of HDAC-1 and -2 to the TBE Region of the hSP-A Promoter

Human fetal lung type II cells were cultured in control medium for 24 h, followed by incubation in the absence (control) or presence of Bt2cAMP or Dex, added alone or in combination for 48 h. Nuclear proteins (10 μg) were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies to HDAC-1 (A), HDAC-2 (B), and total histone H3 (C). Shown are autoradiograms of immunoblots from a representative experiment repeated three times with comparable results. ChIP was carried out to assess the effects of Bt2cAMP and Dex on in vivo binding of HDAC-1 (D) and -2 (E) to a 75-bp region containing the TBE.

Nuclear Levels and TBE Binding of Acetylated and Phosphorylated Histone H3 and IKKα Are Stimulated by cAMP and Inhibited by Dex in Human Fetal Type II Cells

In previous studies, we observed that cAMP stimulation of SP-A expression in type II cells was associated with increased nuclear levels of acetylated histone H3 (K9,14) and its enhanced association with the TBE (10). In light of our present findings that Dex increased recruitment of HDAC-1 and -2 to the TBE, we analyzed effects of Dex on global nuclear levels of acetylated H3 (K9,14) and of levels of this modified histone bound to the TBE. Because phosphorylation of H3 on serine 10 is known to be associated with, functionally linked to, and possibly requisite for H3-K14 acetylation (19,20), we also analyzed effects of Dex and cAMP on H3-S10 phosphorylation and binding to the TBE. Cytokine-induced H3-S10 phosphorylation in mouse embryo fibroblasts is mediated by IKKα (21,22), a catalytic subunit of the IKK complex. Furthermore, cAMP was found to increase H3-S10 phosphorylation in rat ovarian granulosa cells (23,24). To begin to define the mechanisms whereby Bt2cAMP and Dex regulate H3 phosphorylation, we also analyzed effects of Dex and cAMP on nuclear levels of IKKα and its recruitment to the TBE in human fetal type II cells.

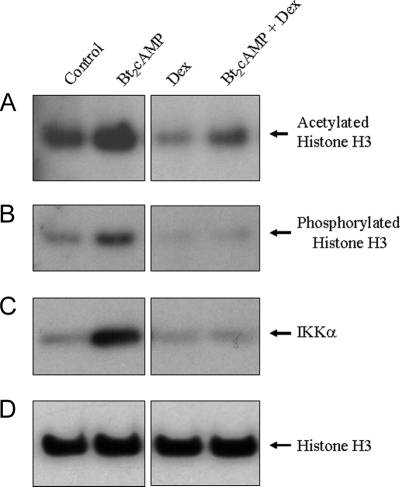

Type II cells were incubated for 48 h in serum-free medium in the absence or presence of Bt2cAMP or Dex, added alone or in combination. Nuclear proteins (10 μg) were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies to phosphorylated (S10), acetylated (K9,14), and total histone H3 as well as IKKα. As observed previously, Bt2cAMP increased nuclear levels of acetylated histone H3; stimulatory effects of cAMP on phosphorylated H3 and IKKα also were evident (Fig. 5). By contrast, Dex treatment reduced nuclear levels of acetylated and phosphorylated histone H3 and antagonized the stimulatory effects of Bt2cAMP on levels of acetylated and phosphorylated H3 and of IKKα. Levels of total histone H3 were unaffected by any treatment (Fig. 5). This indicates that the inhibitory effect of Dex on SP-A gene expression may be mediated, in part, by a global decline in acetylation and phosphorylation of histones.

Figure 5.

Levels of Acetylated and Phosphorylated Histone H3 and of IKKα in Human Fetal Type II Cells Are Stimulated by Bt2cAMP and Inhibited by Dex Treatment

Human fetal type II cells were incubated for 24 h in control medium followed by incubation for 48 h in the absence or presence of Bt2cAMP or Dex, added alone or in combination. Nuclear proteins (10 μg) were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies to acetyl-histone H3 (K9,14) (A), phosphorylated histone H3 (S10) (B), IKKα (C), and total histone H3 (D). Shown are autoradiograms of immunoblots from a representative experiment repeated three times with comparable results.

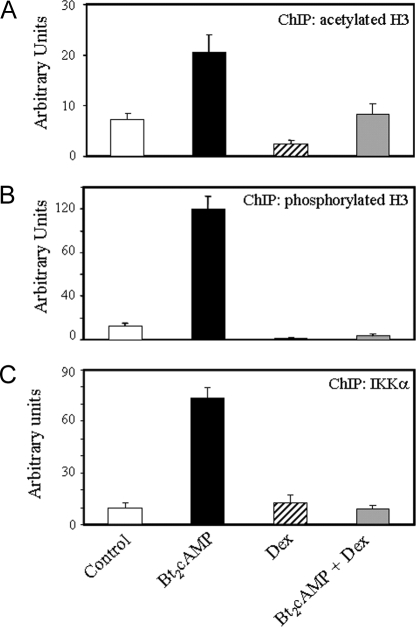

ChIP assays were carried out to analyze effects of cAMP and Dex, added alone and in combination, on levels of acetylated (K9,14) and phosphorylated (S10) histone H3 associated with the TBE region. Human fetal lung type II cells were cultured in the absence or presence of Bt2cAMP, Dex, or the two agents in combination for 48 h. As previously reported, when type II cells were cultured in the presence of cAMP, there was a marked increase in local acetylation of histone H3 (K9,14) at the TBE (10). Interestingly, Dex had a pronounced effect to reduce the levels of acetylated histone H3 at the TBE and antagonized the stimulatory effect of cAMP (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, Bt2cAMP markedly stimulated levels of phosphorylated histone H3 (Fig. 6B) and of IKKα (Fig. 6C) at the TBE, whereas Dex reduced levels as compared with untreated cells and markedly repressed the stimulatory effects of cAMP. Therefore, Dex may exert its inhibitory effect on H3-S10 phosphorylation, in part, via GR-mediated inhibition of IKKα expression and recruitment to the TBE.

Figure 6.

Bt2cAMP Stimulates and Dex Inhibits Binding of Endogenous Acetyl- (K9,14) and Phospho- (S10) Histone H3 and of IKKα to the TBE Region of the hSP-A Promoter in Human Fetal Lung Type II Cells

Human fetal lung type II cells were cultured in control medium for 24 h followed by incubation in the absence (control) or presence of Bt2cAMP or Dex, added alone or in combination for 48 h. ChIP was used to analyze in vivo binding of acetylated (K9,14) (A) or phosphorylated (S10) (B) histone H3 and IKKα (C) to a 75-bp region containing the TBE using Q-PCR. Data are expressed as arbitrary units. Shown is a representative of three independent experiments. The bars represent the means ± sem of data from triplicate culture dishes.

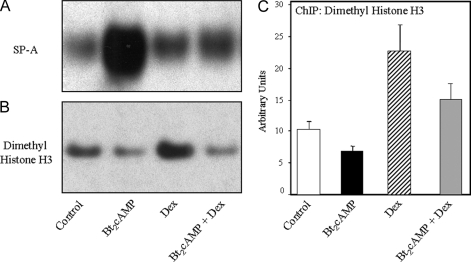

Dex Increases Nuclear Levels of Histone H3 Dimethylated on K9 and Enhances Levels of Dimethyl (K9) Histone H3 Associated with the TBE Region of the SP-A Promoter

Dimethylation of K9 of histone H3 has been found to play an important role in transcriptional silencing (25). Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions prepared from human fetal type II cells cultured for 48 h in the absence or presence of Bt2cAMP, Dex, or the two agents in combination were analyzed for SP-A and for dimethyl H3-K9 by immunoblotting. As can be seen in Fig. 7B, nuclear levels of dimethyl H3-K9 were reduced by cAMP and increased by Dex treatment compared with control. Interestingly, cAMP antagonized the stimulatory effect of Dex on histone dimethylation. These effects were inversely correlated with effects of Dex and cAMP on SP-A expression (Fig. 7A). Importantly, these actions of Dex and cAMP on global levels of dimethyl H3-K9 were associated with comparable effects on the recruitment of this dimethylated histone to the SP-A genomic region surrounding the TBE, as revealed by ChIP analysis (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Nuclear Levels of Dimethyl Histone H3 (K9) and Its Association with the TBE-Containing Region of the SP-A Promoter Are Increased by Dex Treatment

Human fetal lung type II cells were cultured in control medium for 24 h followed by incubation in the absence (control) or presence of Bt2cAMP or Dex, added alone or in combination for 48 h. Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting using antisera to SP-A (A) and dimethyl histone H3 (K9) (B), respectively. ChIP was used to analyze in vivo binding of dimethyl histone H3 (K9) to the 75-bp region containing the TBE (C). Data are expressed as arbitrary units. Shown is a representative of three independent experiments. The bars represent the means ± sem of data from triplicate culture dishes.

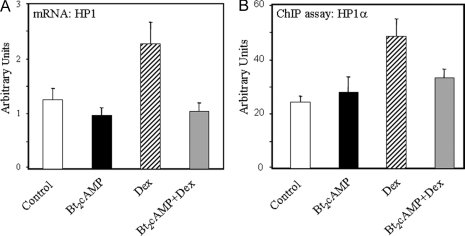

Dex Increases HP1 mRNA Levels and Enhances Binding of HP1α to the TBE Region of the SP-A Promoter in Cultured Type II Cells

Methylated H3-K9 has been found to serve as a binding site for HP1, which is crucial for formation and maintenance of condensed/inactive heterochromatin (26,27). We, therefore, used Q-RT-PCR to analyze HP1 mRNA levels in human fetal type II cells cultured for 24 h in control medium followed by incubation for 48 h in the absence (control) or presence of Bt2cAMP or Dex, alone and in combination. As can be seen in Fig. 8A, Dex increased HP1 mRNA levels compared with control and Bt2cAMP-treated type II cells. Interestingly, cAMP antagonized the inductive effect of Dex on HP1 expression. By use of ChIP, Dex treatment also was found to increase in vivo binding of HP1α to the TBE region of the SP-A promoter (Fig. 8B). It should be noted that the finding that cAMP antagonized Dex-induced HP1 expression and binding to the TBE suggests that increased HP1 recruitment may not significantly contribute to Dex antagonism of cAMP-induced SP-A expression.

Figure 8.

Dex Increases HP1 mRNA Levels and Enhances in Vivo Binding of HP1α to the TBE-Containing Region of the SP-A Promoter in Lung Type II Cells

Human fetal lung type II cells were cultured in control medium for 24 h, followed by incubation in the absence (control) or presence of Bt2cAMP or Dex, added alone or in combination for 48 h. Total RNA prepared from these cells was analyzed for levels of HP1 by Q-RT-PCR (A). Data were normalized by analyzing the ratio of the target cDNA concentrations to that of 18S rRNA. Shown is a representative of three independent experiments. The bars represent the means ± sem of data from triplicate culture dishes. Solubilized chromatin isolated from the cells was subjected to ChIP analysis using an antibody to HP1α. After immunoprecipitation, purified DNA was analyzed by Q-PCR using primers to amplify the 75-bp region containing the TBE (B). The data are expressed as arbitrary units. Shown is a representative of three independent experiments. The bars represent the means ± sem of data from triplicate dishes.

DISCUSSION

The seminal discovery that administration of glucocorticoids to fetal lambs resulted in enhanced lung maturation (28) and that glucocorticoid treatment of fetal rabbits increased surfactant production and accelerated the appearance of pulmonary type II cells (29,30) led to numerous studies that further supported a role of glucocorticoids in surfactant glycerophospholipid synthesis (31,32). Based on these findings, antenatal glucocorticoid treatment of mothers likely to deliver preterm is widely used clinically to enhance lung maturation and prevent respiratory distress in their preterm infants (33). In fact, surfactant glycerophospholipid synthesis in human fetal lung is subject to multihormonal control; in addition to glucocorticoids, a number of polypeptide and steroid hormones as well as hormones that increase cAMP also play a role in its regulation (32).

Further support for an important role of glucocorticoids acting through GR in fetal lung maturation and the regulation of surfactant synthesis was provided from studies of mice homozygous for deletion of the GR gene, which die within hours of birth as a result of atelectasis (34). Although the cause of the respiratory distress remains unclear, the lungs of these mice manifested increased septal thickening and a marked reduction in the number of type I cells (35). Interestingly, mice homozygous for a point mutation in GR that blocks dimerization and DNA binding were viable, despite the lack of induction of a number of GR-responsive genes (36). This suggests that the GR does not have to bind directly to DNA response elements to exert its effects on fetal lung maturation.

The regulation of SP-A gene expression by glucocorticoids is complex and multifaceted, involves transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms (37,38,39,40), and may be mediated by direct (8) and indirect (41) actions of the steroid on type II cells. In type II cell transfection studies using either rabbit (42) or human (8) SP-A:hGH fusion gene constructs containing about 400 bp of SP-A 5′-flanking DNA, we observed that Dex had a profound inhibitory effect on cAMP and IL-1 stimulation of SP-A promoter activity. Our previous findings suggest that the inhibitory actions of Dex on SP-A expression are not mediated by direct binding of GR to a response element upstream of the SP-A gene. Rather, these effects are likely mediated via GR inhibition of TTF-1 and NF-κB transcriptional activity through its interaction with the complex of proteins bound to the TBE (8). In that study, we also observed that Dex increased expression of the NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα, in the human fetal lung type II cells. However, the relative impact on Dex inhibition of SP-A expression of IκBα up-regulation vs. GR interaction with proteins at the TBE cannot readily be determined.

In the present study, we observed that GR knockdown using morpholino antisense oligonucleotide enhanced SP-A expression in cultured type II cells. ChIP revealed that Dex increased recruitment of endogenous GR to the TBE. Furthermore, using DAPA, endogenous GR was found to interact with TTF-1 and NF-κB p65 at the TBE. These collective findings suggest that endogenous GR exerts a tonic and possibly ligand-independent inhibitory effect on hSP-A gene expression through interaction with NF-κB and TTF-1 at the TBE that can be enhanced by glucocorticoid treatment. We previously observed that the progesterone receptor, which is structurally related to GR, exerts an important ligand-independent inhibitory action on cyclooxygenase 2 gene expression through interaction with transcription factors bound to an NF-κB response element (43).

An objective of the present study was to define the histone modifications associated with the inhibitory actions of Dex/GR on SP-A expression. Histones are subject to a number of posttranslational modifications, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, and ADP ribosylation (see Ref. 44 for review). It has been suggested that the combinatorial nature of these covalent modifications of the histone tails reveals a histone code, which provides a unique regulatory system that influences the transition between transcriptionally silent (heterochromatin) and active (euchromatin) chromatin (44). Whereas euchromatin is generally associated with histones acetylated on specific lysine residues (e.g. K9 and K14 of histone H3), heterochromatin contains predominately hypoacetylated histones. In recent years, it has become increasingly apparent that the binding of activating transcription factors to DNA results in the recruitment of coactivator complexes, which contain enzymatic activities that cause dynamic changes in the posttranslational modification of histones (45,46). Importantly, some coactivators contain HAT activity, which catalyzes acetylation of lysines on histone N-terminal tails, resulting in a local unwinding of nucleosomes and loosening of the higher-order chromatin structure surrounding the promoter. This facilitates recruitment of general transcription factors and of RNA polymerase II, resulting in stabilization of the pre-initiation complex and activation of transcription initiation (45). Conversely, corepressors may inhibit transcriptional activation by causing deacetylation and methylation of histones and methylation of DNA to promote formation of a closed chromatin structure.

As mentioned, we previously observed that cAMP and IL-1 stimulated binding of endogenous TTF-1 and NF-κB p65 to the TBE region of the hSP-A promoter; this was associated with increased recruitment of the HAT coactivators CBP and SRC-1 and increased local acetylation of histone H3 (K9,14), a mark of active chromatin (44). By contrast, in cells cultured under hypoxic conditions, stimulatory effects of cAMP and IL-1α on TBE binding of TTF-1 and NF-κB, on recruitment of CBP or SRC-1, and on levels of acetylated H3-K9 were prevented (10). Hypoxia also increased expression of HDACs 1–11 as well as corepressors NCoR1 and SMRT (10). Importantly, incubation of type II cells with the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A enhanced SP-A expression in type II cells cultured with or without Bt2cAMP (10).

In the present study, we observed that Dex treatment of human fetal type II cells decreased nuclear levels and TBE binding of acetylated (K9,14) histone H3 and antagonized the stimulatory effects of Bt2cAMP. This was associated with Dex stimulation of nuclear levels of HDACs 1 and 2 and their binding to the TBE. Conversely, HDAC-1 and -2 binding to the TBE region was inhibited by Bt2cAMP treatment. As mentioned, a stimulatory effect of glucocorticoids on recruitment of HDAC-2 to the NF-κB response element of the GM-CSF promoter in lung adenocarcinoma cells was previously reported (14,15). These findings suggest that Dex/GR may inhibit SP-A gene expression by promoting a closed chromatin structure through induction of histone deacetylases and their increased binding to the TBE.

Of particular interest is the present finding that Bt2cAMP markedly increased and Dex inhibited in vivo binding of IKKα to the TBE region. Furthermore, Dex abrogated the stimulatory effect of Bt2cAMP on IKKα binding. This was associated with comparable stimulatory and inhibitory effects of cAMP and Dex, respectively, on in vivo binding to the SP-A promoter of phosphorylated histone H3 (S10), an IKKα target (21). IKKα is known to be recruited to the promoter regions of NF-κB-regulated genes by interacting with HAT coactivators such as CBP and GCN5 and contributes to NF-κB-mediated gene expression through phosphorylation of histone H3 (21,22). Our findings suggest that Dex antagonizes cAMP induction of SP-A gene expression by inhibiting expression and/or activation of IKKα and H3 phosphorylation. Notably, phosphorylation of H3-S10 appears to be prerequisite for acetylation of H3-K14, which blocks methylation of H3-K9 (44), a repressive chromatin mark, as described below.

It also was of interest to analyze the effects of glucocorticoids on histone methylation, which occurs on the ε-amino group of lysine and the guanidine-ε group of arginine residues in the N-terminal histone tails. Histone methylation is catalyzed by two divergent families: the histone lysine methyltransferases and the protein arginine methyltransferases. Arginine methylation is generally an activating mark, whereas lysine methylation can either be inhibitory (e.g. H3-K9) or activating (e.g. H3-K4). Lysines can be mono-, di-, or trimethylated. Methylation of H3-K9 has been found to play a role in transcriptional silencing (44) by forming a binding site for HP1, which subsequently mediates formation of condensed heterochromatin (26,27,47,48). Previously, we found that the hypoxia-mediated inhibition of SP-A promoter activity was associated with increased nuclear levels of dimethyl H3-K9 and its increased association with the hSP-A genomic region containing the TBE (10).

In the present study, we observed that nuclear levels of dimethyl histone H3-K9 were reduced by cAMP and increased by Dex treatment, as compared with control. Interestingly, cAMP antagonized the stimulatory effect of Dex on histone dimethylation. These effects were inversely correlated with effects of Dex and cAMP on SP-A expression. Importantly, these actions of Dex and cAMP on global levels of dimethylated H3-K9 were associated with comparable effects on the levels of this dimethylated histone bound to the SP-A genomic region containing the TBE. Notably, 5′-deoxy[5′-methylthio]adenosine (d-MTA), an S-adenosylmethionine metabolite that inhibits histone H3 methylation (49), was found to markedly increase SP-A expression in type II cells cultured with or without Bt2cAMP (10). In the present study, we also observed that Dex treatment increased expression and recruitment to the TBE region of HP1α. Importantly, in yeast, deacetylation of H3-K9 by HDACs appears to be prerequisite for methylation of this site (26,50). Furthermore, many of the lysine methylation sites on histones lie adjacent to Ser/Thr residues that are potential phosphorylation sites, and it has been suggested that phosphorylation of these residues may serve as switches for methylation-dependent recruitment of HP1 (51). Notably, phosphorylation of H3-S10 was reported to abrogate binding of HP1 to methylated histone H3 (K9) (51).

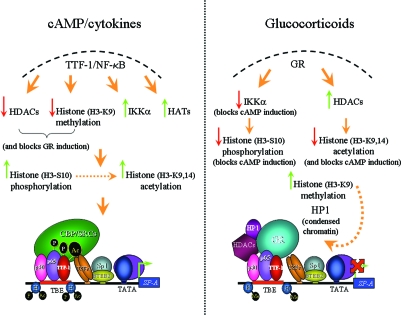

In summary, our past and present findings reveal that cAMP and IL-1 treatment of type II cells promotes binding of TTF-1 and NF-κB to the TBE and recruitment of coactivators with HAT activity (Fig. 9). This is associated with decreased expression and recruitment of HDACs and increased levels of acetylated histone H3 (K9,14), phosphorylated histone H3 (S10), and decreased levels of dimethylated histone H3 (K9) at the TBE region of the SP-A promoter. By contrast, GR exerts both ligand-dependent and -independent inhibitory effects on hSP-A promoter activity, mediated in part via its tethering to the complex of proteins bound to the TBE. Glucocorticoids cause increased recruitment of HDACs, with decreased levels and binding of acetylated (K9,14) and phosphorylated (S10) histone H3. Notably, glucocorticoids antagonized cAMP stimulation of IKKα recruitment and of phosphorylation and acetylation of histone H3 at the TBE. We suggest that Dex/GR inhibition of histone H3-S10 phosphorylation and H3-K9 acetylation promotes increased dimethylation of H3-K9 at the TBE and recruitment of HP1α. This, in turn, results in a closed chromatin structure with decreased access of RNA polymerase to the SP-A promoter and suppression of SP-A gene expression in fetal lung type II cells. We propose that cAMP induction and glucocorticoid repression of IKKα binding to the TBE region plays a pivotal and crucial role in the activating and repressive actions of these factors in SP-A gene expression.

Figure 9.

Epigenetic Mechanisms for Glucocorticoid and cAMP Regulation of SP-A Gene Expression in Human Fetal Lung

In this and other studies, we have found that the stimulatory effect of cAMP on hSP-A expression is associated with increased binding of TTF-1 and NF-κB to the TBE. This occurs in concert with increased recruitment of HATs and of IKKα to the TBE. This, in turn, is associated with increased phosphorylation of the IKKα substrate, H3-S10, increased acetylation of H3-K9, decreased dimethylation of H3-K9, and decreased binding of HDACs at the TBE region. By contrast, glucocorticoid inhibition of hSP-A gene transcription is associated with enhanced GR binding to the complex of proteins at the TBE and with abrogation of the stimulatory effects of cAMP on IKKα recruitment and on levels of phosphorylated (S10) and acetylated (K9,14) histone H3 at the TBE region of the hSP-A promoter. This also occurs together with increased recruitment of HDACs, increased H3 dimethylation (K9), and binding of HP1α to the TBE region. Collectively, this may lead to a repressed chromatin state, resulting in decreased access of RNA polymerase to the SP-A promoter and suppression of SP-A gene expression in fetal lung type II cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation and Culture of Human Fetal Lung Explants and Type II Cells

Midgestation human fetal lung tissues were obtained from Advanced Bioscience Resources, Inc., in accordance with the Donors Anatomical Gift Act of the State of Texas; protocols were approved by the Human Research Review Committee of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Type II cells were isolated from cultured midgestation human fetal lung explants, as described previously (52). Briefly, lung explants were maintained in organ culture in serum-free Waymouth’s MB752/1 medium (Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD) in the presence of Bt2cAMP to promote type II cell differentiation (53). After 3 d of culture, tissues were digested with collagenase; isolated cells were treated with diethylaminoethyl-dextran and plated at a density of 5–9 × 106 cells/60-mm dish. The cells were maintained overnight in Waymouth’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and then placed in serum-free Waymouth’s medium (control medium) for 24 h at 37 C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2 (20% O2), followed by incubation for up to 2 d in serum-free medium in the absence or presence of Bt2cAMP (1 mm) (Roche/BMB, Indianapolis, IN), dexamethasone (Dex) (100 nm; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), or Bt2cAMP and Dex in combination.

Delivery of Morpholino Antisense Oligonucleotides for hGR into Fetal Lung Type II Cells

Translation-blocking morpholino antisense oligonucleotide for GR (GR-MO) (5′-AAT GAT TCT TTG GAG TCC ATC AGT G-3′) and a morpholino control oligonucleotide (5′-CCT CTT ACC TCA GTT ACA ATT TAT A-3′) were obtained from Gene Tools (Philomath, OR). Fetal lung type II cells cultured in control serum-free medium were incubated with 10 μm GR-MO or control oligonucleotide and Endo-Porter (10 μl/ml; Gene Tools) for 48 h in the absence or presence of Bt2cAMP or Dex. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were analyzed for protein levels of SP-A and GR by immunoblotting.

Immunoblot Analysis

Human fetal type II cells were cultured for up to 48 h in serum-free medium in the absence or presence of Bt2cAMP, Dex, or the two agents in combination. The cells were scraped from the dishes and homogenized in ice-cold PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail (1 tablet/10 ml) (Roche Laboratories). Proteins (7 μg) from nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions (6) were separated on NuPAGE Novex 4–12% bis-tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as described previously (54). The membranes were then analyzed by immunoblotting using specific antibodies to SP-A (4), GR (Affinity BioReagents, Inc., Golden, CO), HDACs 1 and 2, (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), histone H3, histone H3 phosphorylated on S10, histone H3 acetylated on K9 and K14, or histone H3 dimethylated on K9 (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Lake Placid, NY) and an enhanced chemiluminescence system, according to manufacturer’s recommendations (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ).

Real-Time Q-RT-PCR

Human fetal type II cells were cultured for up to 48 h in serum-free medium with or without Bt2cAMP, Dex, or the two agents in combination. Total RNA was isolated from these cells by the one-step method described previously (55) (TRIzol; Invitrogen). RNA was treated with DNase to remove any contaminating DNA, and 4 μg were reverse transcribed using random primers and Superscript II RNase H reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Validated primer sets directed against HP1 (forward, 5′-CGT CTC AAG GTG AAC TCG TCC-3′; reverse, 5′-CGA ATC GGC ATG GTG CTA T-3′) along with the constitutively expressed 18S rRNA (forward, 5′-ACC GCA GCT AGG AAT AAT GGA-3′; reverse, 5′-GCC TCA GTT CCG AAA ACC A-3′) were used for Q-PCR amplification. The ABI Prism 7700 detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was employed using the DNA-binding dye SYBR green (PE Applied Biosystems) for the quantitative detection of PCR products. The cycling conditions were 50 C for 2 min and 95 C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95 C for 15 sec and 60 C for 1 min. The cycle threshold was set at a level where the exponential increase in PCR amplification was approximately parallel between all samples. Data were normalized by analyzing the ratio of the target cDNA concentrations to that of 18S rRNA. We have compared expression of 18S rRNA to that of cyclophilin and have found both to be unaffected by Dex/cAMP treatment.

ChIP

Human fetal type II cells were cultured for up to 48 h in serum-free medium or in medium containing Bt2cAMP (1 mm) or Dex (100 nm), alone or in combination. ChIP was performed as described in detail previously (10). The soluble chromatin (500 μl) was incubated with antibodies for GR, HDACs 1 and 2 (Santa Cruz), IKKα (Cell Signaling Technology), acetylated histone H3 (K9,14), dimethyl histone H3 (K9), phosphorylated histone H3 (S10), or HP1α (Upstate), and incubated at 4 C overnight. Two aliquots were reserved as controls, one incubated without antibody and the other with nonimmune IgG. Immune complexes were isolated using Protein A/G Plus agarose beads and collected by centrifugation. Cross-linking of the immunoprecipitated chromatin complexes and input controls (5% of the total soluble chromatin) was reversed by heating the samples at 65 C for 4 h, followed by incubation with proteinase K, DNA purification by phenol-chloroform extraction, and precipitation in ethanol at −20 C. Samples and input controls were diluted in Tris-EDTA buffer just before PCR. Real-time PCR (56) was carried out using the following primers to amplify 75 bp of the hSP-A2 5′-flanking region surrounding the TBE (forward, 5′-TTT TTC TTT ACC AGG TTC TGT GCT GCT C-3′; reverse, 5′-CAC ATT TCC CTG CAG AAC ACT A-3′).

DAPA

DAPA was performed according to Zhang and Dufau (57). Briefly, 5′ biotin end-labeled sense and antisense oligonucleotides corresponding to wild-type (5′-GTGCTCCCCTCAAGGGTCCT-3′; core sequence underlined) or mutant (5′-GTGCTCCCagtcgtGGTCCT-3′; mutation shown in lowercase type) TBE binding site of the hSP-A promoter were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA). The oligomers were annealed and gel purified. Nuclear extract proteins (75 μg) isolated from Bt2cAMP-treated fetal lung type II cells were incubated with 0.3 μg wild-type or mutant oligonucleotide probe in 400 μl binding buffer [60 mm KCl, 12 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 4 mm Tris-HCl, 5% glycerol, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1× protease inhibitor mixture] on ice for 45 min. The DNA-protein complexes were then incubated with 40 μl Tetralink avidin resin (Promega, Madison, WI), which was preequilibrated in the binding buffer for 1 h. The incubation was continued for 1 h at 4 C with gentle rotation. DNA-protein complexes were washed five times with the binding buffer. Sample buffer was added to avidin-precipitated DNA-protein complex, which was then boiled for 5 min to dissociate the complexes. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting using antibodies to human GR, TTF-1 (58), and p65 (Santa Cruz).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Margaret E. Smith for her expert preparation and maintenance of the human fetal type II cells used in this study.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R37 HL050022.

Disclosure Statement: Neither of the authors has anything to declare regarding potential conflicts of interest.

First Published Online December 13, 2007

Abbreviations: AP-1, activating protein-1; Bt2cAMP, dibutyryl cAMP; CBP, cAMP response element-binding protein-binding protein; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; DAPA, DNA-affinity precipitation assay; Dex, dexamethasone; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; HAT, histone acetyltransferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; hGR, human GR; HP1, heterochromatin protein 1; IKKα, inhibitor of κB kinase-α; NF, nuclear factor; Q, quantitative; SP-A, surfactant protein-A; SRC-1, steroid receptor coactivator-1; TBE, TTF-1-binding element; TTF-1, thyroid transcription factor-1.

References

- Mendelson CR, Gao E, Li J, Young PP, Michael LF, Alcorn JL 1998 Regulation of expression of surfactant protein-A. Biochim Biophys Acta 1408:132–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JR 2005 Immunoregulatory functions of surfactant proteins. Nat Rev Immunol 5:58–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon JC, Jeyasuria P, Faust JM, Mendelson CR 2004 Surfactant protein secreted by the maturing mouse fetal lung acts as a hormone that signals the initiation of parturition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:4978–4983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom MJ, Snyder JM, Mendelson CR 1987 Adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate analogs and β-adrenergic agonists induce the synthesis of the major surfactant apoprotein in human fetal lung in vitro. Endocrinology 121:1155–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acarregui MJ, Snyder JM, Mitchell MD, Mendelson CR 1990 Prostaglandins regulate surfactant protein A (SP-A) gene expression in human fetal lung in vitro. Endocrinology 127:1105–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam KN, Mendelson CR 2002 Potential role of nuclear factor κB and reactive oxygen species in cAMP and cytokine regulation of surfactant protein-A gene expression in lung type II cells. Mol Endocrinol 16:1428–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom MJ, Snyder JM, Boggaram V, Mendelson CR 1988 Glucocorticoid regulation of the major surfactant associated protein (SP-A) and its messenger ribonucleic acid and of morphological development of human fetal lung in vitro. Endocrinology 123:1712–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcorn JL, Islam KN, Young PP, Mendelson CR 2004 Glucocorticoid inhibition of SP-A gene expression in lung type II cells is mediated via the TTF-1-binding element. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286:L767–L776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acarregui MJ, Snyder JM, Mendelson CR 1993 Oxygen modulates the differentiation of human fetal lung in vitro and its responsiveness to cAMP. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 264:L465–L474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam KN, Mendelson CR 2006 Permissive effects of oxygen on cyclic AMP and interleukin-1 stimulation of surfactant protein A gene expression are mediated by epigenetic mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol 26:2901–2912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont A, Hehner SP, Schmitz ML, Gustafsson JA, Liden J, Okret S, van der Saag PT, Wissink S, van der Burg B, Herrlich P, Haegeman G, De Bosscher K, Fiers W 1998 Cross-talk between steroids and NF-κB: what language? Trends Biochem Sci 23:233–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schule R, Rangarajan P, Kliewer S, Ransone LJ, Bolado J, Yang N, Verma IM, Evans RM 1990 Functional antagonism between oncoprotein c-Jun and the glucocorticoid receptor. Cell 62:1217–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefstin JA, Yamamoto KR 1998 Allosteric effects of DNA on transcriptional regulators. Nature 392:885–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM 2000 Glucocorticoid receptor recruitment of histone deacetylase 2 inhibits interleukin-1β-induced histone H4 acetylation on lysines 8 and 12. Mol Cell Biol 20:6891–6903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ 2006 How corticosteroids control inflammation: Quintiles Prize Lecture 2005. Br J Pharmacol 148:245–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Yamamura S, Essilfie-Quaye S, Cosio B, Ito M, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM 2006 Histone deacetylase 2-mediated deacetylation of the glucocorticoid receptor enables NF-κB suppression. J Exp Med 203:7–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinman RI, Gualberto A, Jewell CM, Cidlowski JA, Baldwin Jr AS 1995 Characterization of mechanisms involved in transrepression of NF-κB by activated glucocorticoid receptors. Mol Cell Biol 15:943–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay LI, Cidlowski JA 1998 Cross-talk between nuclear factor-κB and the steroid hormone receptors: mechanisms of mutual antagonism. Mol Endocrinol 12:45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo WS, Trievel RC, Rojas JR, Duggan L, Hsu JY, Allis CD, Marmorstein R, Berger SL 2000 Phosphorylation of serine 10 in histone H3 is functionally linked in vitro and in vivo to Gcn5-mediated acetylation at lysine 14. Mol Cell 5:917–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P, Tanner KG, Cheung WL, Sassone-Corsi P, Denu JM, Allis CD 2000 Synergistic coupling of histone H3 phosphorylation and acetylation in response to epidermal growth factor stimulation. Mol Cell 5:905–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Verma UN, Prajapati S, Kwak YT, Gaynor RB 2003 Histone H3 phosphorylation by IKK-α is critical for cytokine-induced gene expression. Nature 423:655–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anest V, Hanson JL, Cogswell PC, Steinbrecher KA, Strahl BD, Baldwin AS 2003 A nucleosomal function for IκB kinase-α in NF-κB-dependent gene expression. Nature 423:659–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador LM, Park Y, Cottom J, Maizels ET, Jones JC, Schillace RV, Carr DW, Cheung P, Allis CD, Jameson JL, Hunzicker-Dunn M 2001 Follicle-stimulating hormone stimulates protein kinase A-mediated histone H3 phosphorylation and acetylation leading to select gene activation in ovarian granulosa cells. J Biol Chem 276:40146–40155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeManno DA, Cottom JE, Kline MP, Peters CA, Maizels ET, Hunzicker-Dunn M 1999 Follicle-stimulating hormone promotes histone H3 phosphorylation on serine-10. Mol Endocrinol 13:91–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JC, Briggs SD, Ueberheide B, Barber CM, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Shinkai Y, Allis CD 2003 Histone methyltransferases direct different degrees of methylation to define distinct chromatin domains. Mol Cell 12:1591–1598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama J, Rice JC, Strahl BD, Allis CD, Grewal SI 2001 Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science 292:110–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister AJ, Zegerman P, Partridge JF, Miska EA, Thomas JO, Allshire RC, Kouzarides T 2001 Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature 410:120–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liggins GC 1969 Premature delivery of foetal lambs infused with glucocorticoids. J Endocrinol 45:515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotas RV, Avery ME 1971 Accelerated appearance of pulmonary surfactant in the fetal rabbit. J Appl Physiol 30:358–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang NS, Kotas RV, Avery ME, Thurlbeck WM 1971 Accelerated appearance of osmiophilic bodies in fetal lungs following steroid injection. J Appl Physiol 30:362–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard PL 1989 Hormonal regulation of pulmonary surfactant. Endocr Rev 10:165–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson CR, Boggaram V 1991 Hormonal control of the surfactant system in fetal lung. Annu Rev Physiol 53:415–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liggins GC, Howie RN 1972 A controlled trial of antepartum glucocorticoid treatment for prevention of the respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants. Pediatrics 50:515–525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole TJ, Blendy JA, Monaghan AP, Krieglstein K, Schmid W, Aguzzi A, Fantuzzi G, Hummler E, Unsicker K, Schutz G 1995 Targeted disruption of the glucocorticoid receptor gene blocks adrenergic chromaffin cell development and severely retards lung maturation. Genes Dev 9:1608–1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole TJ, Solomon NM, Van Driel R, Monk JA, Bird D, Richardson SJ, Dilley RJ, Hooper SB 2004 Altered epithelial cell proportions in the fetal lung of glucocorticoid receptor null mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 30:613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt HM, Kaestner KH, Tuckermann J, Kretz O, Wessely O, Bock R, Gass P, Schmid W, Herrlich P, Angel P, Schutz G 1998 DNA binding of the glucocorticoid receptor is not essential for survival. Cell 93:531–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggaram V, Smith ME, Mendelson CR 1989 Regulation of expression of the gene encoding the major surfactant protein (SP-A) in human fetal lung in vitro. Disparate effects of glucocorticoids on transcription and on mRNA stability. J Biol Chem 264:11421–11427 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggaram V, Smith ME, Mendelson CR 1991 Posttranscriptional regulation of surfactant protein-A messenger RNA in human fetal lung in vitro by glucocorticoids. Mol Endocrinol 5:414–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover RR, Floros J 1999 SP-A 3′-UTR is involved in the glucocorticoid inhibition of human SP-A gene expression. Am J Physiol 276:L917–L924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannuzzi DM, Ertsey R, Ballard PL 1993 Biphasic glucocorticoid regulation of pulmonary SP-A: characterization of inhibitory process. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 264:L236–L244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BT, Post M 1989 Fibroblast-pneumonocyte factor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 257:L174–L178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcorn JL, Gao E, Chen Q, Smith ME, Gerard RD, Mendelson CR 1993 Genomic elements involved in transcriptional regulation of the rabbit surfactant protein-A gene. Mol Endocrinol 7:1072–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy DB, Janowski BA, Corey DR, Mendelson CR 2006 Progesterone receptor (PR) plays a major anti-inflammatory role in human myometrial cells by antagonism of NF-κB activation of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) expression. Mol Endocrinol 20:2724–2733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenuwein T, Allis CD 2001 Translating the histone code. Science 293:1074–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna NJ, Lanz RB, O’Malley BW 1999 Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev 20:321–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonard DM, O’Malley BW 2006 The expanding cosmos of nuclear receptor coactivators. Cell 125:411–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T 2002 Histone methylation in transcriptional control. Curr Opin Genet Dev 12:198–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgin SC, Grewal SI 2003 Heterochromatin: silence is golden. Curr Biol 13:R895–R898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MR, Ghosh A 2004 FGF2-induced chromatin remodeling regulates CNTF-mediated gene expression and astrocyte differentiation. Nat Neurosci 7:229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P, Lau P 2005 Epigenetic regulation by histone methylation and histone variants. Mol Endocrinol 19:563–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W, Wang Y, Allis CD 2003 Binary switches and modification cassettes in histone biology and beyond. Nature 425:475–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcorn JL, Smith ME, Smith JF, Margraf LR, Mendelson CR 1997 Primary cell culture of human type II pneumonocytes: maintenance of a differentiated phenotype and transfection with recombinant adenoviruses. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 17:672–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JM, Johnston JM, Mendelson CR 1981 Differentiation of type II cells of human fetal lung in vitro. Cell Tissue Res 220:17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson CR, Chen C, Boggaram V, Zacharias C, Snyder JM 1986 Regulation of the synthesis of the major surfactant apoprotein in fetal rabbit lung tissue. J Biol Chem 261:9938–9943 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N 1987 Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem 162:156–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon JC, Jeyasuria P, Faust JM, Wilson JM, Mendelson CR 2003 A decline in progesterone receptor coactivators in the pregnant uterus at term may antagonize progesterone receptor function and contribute to the initiation of labor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:9518–9523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Dufau ML 2002 Silencing of transcription of the human luteinizing hormone receptor gene by histone deacetylase-mSin3A complex. J Biol Chem 277:33431–33438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Gao E, Mendelson CR 1998 Cyclic AMP-responsive expression of the surfactant protein-A gene is mediated by increased DNA binding and transcriptional activity of thyroid transcription factor-1. J Biol Chem 273:4592–4600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi M, Tong GX, Murry B, Mendelson CR 2001 Role of CBP/p300 and SRC-1 in transcriptional regulation of the pulmonary surfactant protein-A (SP-A) gene by thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1). J Biol Chem 277:2997–3005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]