Abstract

Although hormone therapy with antiandrogens has been widely used for the treatment of prostate cancer, some antiandrogens may act as androgen receptor (AR) agonists that may result in antiandrogen withdrawal syndrome. The molecular mechanism of this agonist response, however, remains unclear. Using mammalian two-hybrid assay, we report that antiandrogens, hydroxyflutamide, bicalutamide (casodex), cyproterone acetate, and RU58841, and other compounds such as genistein and RU486, can promote the interaction between AR and its coactivator, ARA70, in a dose-dependent manner. The chloramphenicol acetyltransferase assay further demonstrates that these antiandrogens and related compounds significantly enhance the AR transcriptional activity by cotransfection of AR and ARA70 in a 1:3 ratio into human prostate cancer DU145 cells. Our results suggest that the agonist activity of antiandrogens might occur with the proper interaction of AR and ARA70 in DU145 cells. These findings may provide a good model to develop better antiandrogens without agonist activity.

The androgen receptor (AR) is a member of a large family of ligand-dependent transcriptional factors known as the steroid receptor superfamily (1, 2). Androgens and the AR play an important role in the growth of prostate cancer and normal prostate. Prostate cancer represents the most common male malignancy in the United States. In 1998, about 39,200 men will lose their lives to this malignancy (3). Since 1941 (4), androgen ablation has been the cornerstone of treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer. Recently, antiandrogens such as hydroxyflutamide (HF) in combination with surgical or medical castration have been widely used for the treatment of this disease (5). Although the response rate to such androgen ablation therapy is high, the effect is often short-lived (5), as androgen-dependent prostate cancer progresses into androgen independence. On the other hand, the agonist effect of antiandrogens such as HF and cyproterone acetate (CPA) on proliferation of human prostate cancer LNCaP cells was recognized in recent years (6). Subsequently, it was revealed that antiandrogens could activate the AR with a mutation in its ligand binding domain (7). Reports using transient transfection studies (8–10) suggest that antiandrogens may act as agonists on the wild-type AR as well as mutant AR. Indeed, clinical data also indicate that HF can activate the AR-targeted prostatic specific antigen gene and that serum levels of the prostatic specific antigen can decrease after discontinuation of HF. This phenomenon is known as flutamide withdrawal syndrome (11, 12). In the past few years, withdrawal responses have also been reported for other antiandrogens (13–15). However, the mechanisms responsible for androgen independence and the antiandrogen withdrawal syndrome remain unclear.

In the present study, we investigated the influence of six antiandrogens and related compounds on AR transcriptional activity. Classic steroid binding assays have suggested these compounds can inhibit the binding of androgens to the AR in target cells. Three of these antiandrogens have been used clinically in the treatment of prostate cancer: CPA, HF, and bicalutamide (casodex). CPA is a synthetic steroidal antiandrogen and one of the first antiandrogens used clinically in Europe (16); however, it has many side effects (17). HF is a nonsteroidal antiandrogen and seems to be better tolerated than CPA (5, 16). Casodex is a newer nonsteroidal antiandrogen originally thought to be a “pure antiandrogen” without agonist activity. It has a long half-life (6 days) and a higher binding affinity to the AR than HF (18, 19). In addition to these three antiandrogens, three other compounds were tested in this study: genistein, RU486, and RU58841. Genistein is an isoflavonoid phytoestrogen found in some edible plants, including soybean (20), that may contribute to the prevention of prostate cancer. In vitro studies with genistein have revealed an antiproliferative effect in a variety of human cancers, including prostate cancer (20, 21). However, the molecular mechanisms of the anti-tumor action of genistein remain poorly understood. RU486 was identified first as antiprogesterone (22) and later determined to have antiandrogen properties as well (9). It was reported that RU486 can block the interaction of the receptor with the transcription initiation complex (23). RU58841 is a new nonsteroidal antiandrogen with high affinity for the ARs from hamster prostate and flank organ. Animal studies suggest that RU58841 is a candidate for the treatment of androgen-dependent skin diseases (24).

Immunohistochemical staining showed AR expression may contribute to the response to hormone therapy (25, 26). Several recent studies have also postulated that the alterations of AR functions by mutations of this gene may be associated with a poor response to antiandrogens (27, 28); the real mechanism, however, remains unclear. Furthermore, all the documented results cannot rule out the contribution of cellular environment and non-AR factors to the alteration of androgen activity. Recently, we successfully isolated the first relatively specific AR coactivator, ARA70, which can enhance AR transcriptional activity an additional 7–10-fold in human prostate cancer cells (29). We report here that ARA70 can also enhance the agonist activity of antiandrogens 3–30-fold in human prostate cancer DU145 cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antiandrogens.

HF was obtained from Schering, CPA was obtained from Sigma, casodex was obtained from ICI Pharmaceuticals, genistein was obtained from GIBCO BRL, and RU486 and RU58841 were generously provided by H. Uno (University of Wisconsin, Madison).

Plasmids.

pSG5-AR and pSG5-ARA70 were constructed as previously described (29). Two mutants of the AR gene (mAR877 derived from prostate cancer, codon 877 mutation Thr to Ser; and mAR708 derived from partial androgen insensitivity syndrome, codon 708 mutation Glu to Lys) were provided by S. P. Balk (Beth Israel Hospital, Boston) and H. Shima (Hyogo Medical College, Japan), respectively. pGAL0–wild-type AR was provided by D. Chen (University of Massachusetts, Worcester). pGAL0–mAR877 and pGAL0–mAR708 were constructed by inserting fragments, mAR877 and mAR708, into the pGAL0 vector. Similarly, pGAL4–VP16 was used to construct the fusion of ARA70. pGAL0 contains the GAL4 DNA binding domain, and pGAL4–VP16 contains the GAL4 DNA binding domain linked to the acidic activation domain of VP16.

Cell Culture and Transfections.

Human prostate cancer DU145 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium containing penicillin (25 units/ml), streptomycin (25 μg/ml), and 5% fetal calf serum. Transfections were performed using the calcium phosphate precipitation method, as described previously (30). Briefly, 4 × 105 cells were plated on 60-mm dishes 24 h before adding the precipitate containing AR expression plasmid (wild-type or mutated), chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter gene, and ARA70 expression plasmid. The total amount of DNA was adjusted to 10.5 μg with pSG5 or pVP16 in all transfection assays. The medium was changed to Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium with 5% charcoal-stripped fetal calf serum 1 h before transfection. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the medium was changed again, and the cells were treated with dihydrotestosterone (DHT) or antiandrogens for 24 h. The cells were then harvested, and whole cell extracts were used for CAT assay, as described previously (30). A β-galactosidase expression plasmid, pCMV-β-gal, was used as an internal control for transfection efficiency. The CAT activity was visualized by PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) and quantitated by ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). At least three independent experiments were carried out in each case.

Mammalian Two-Hybrid Assay.

DU145 cells were transiently cotransfected with 3.5 μg of a GAL4-hybrid expression plasmid, 3.5 μg of a VP16-hybrid expression plasmid, and 2.5 μg of a reporter plasmid pG5CAT. Transfections and CAT assays were performed as described above.

Partial Proteolysis Assay.

In vitro transcriptions/translations were performed in TNT-coupled reticulocyte lysate systems (Promega) in the presence of [35S]methionine and 1 μM zinc chloride. Three-microliter aliquots of labeled translation mixture were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 2 μl of hormones diluted in water. Then, 1 μl of trypsin solution (25 μg/ml) was added, followed by incubation for 10 min at room temperature. To stop the reaction, SDS-polyacrylamide gel sample buffer was added. The samples were boiled for 5 min and loaded on 0.1% SDS, 12.5% polyacrylamide gel. Gel electrophoresis and autoradiography were carried out as described previously (9, 31, 32).

Western Blot.

Western blotting analysis was performed as described previously (33). In short, cell extracts from DU145 cells transfected with pSG5-AR (wild-type) with or without pSG5-ARA70 were prepared and electrophoresed on 10% polyacrylamide resolving gels before being electrophoretically transferred onto nitrocellulose (Millipore). The polyclonal antibody NH27, specific for the AR (34), was used as primary antibody in an alkaline phosphatase substrate color development method (Bio-Rad). Blots were quantitated by Collage Image Analysis software (Fotodyne).

RESULTS

Interactions between AR and ARA70.

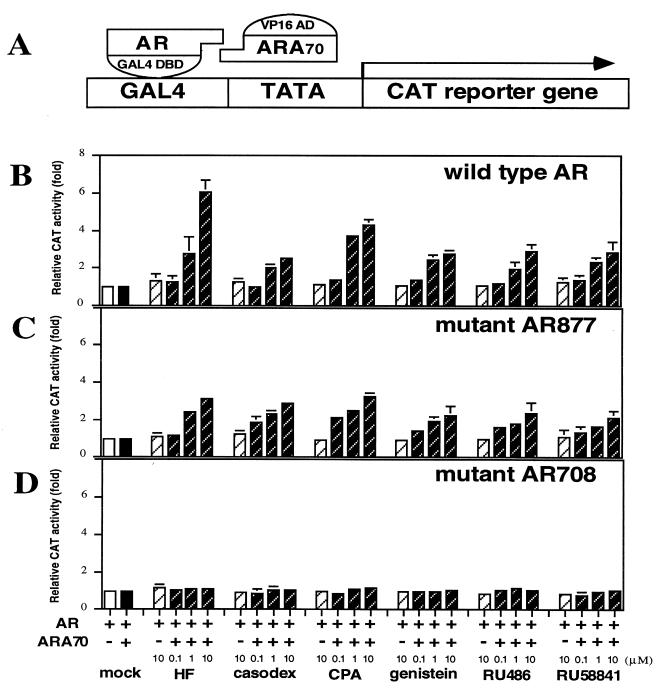

To demonstrate physical interactions between AR and ARA70, we used a mammalian two-hybrid assay. For this study, AR fragments (wild type or mutants) were generated and fused to the DNA binding protein GAL4. Similarly, ARA70 fragment was generated and fused to the transcriptional activation VP16. These fusion plasmids were then coexpressed in DU145 cells with a plasmid containing the CAT reporter (Fig. 1A). Transient transfection of wild-type AR and ARA70 with mock treatment showed no effect on induction of CAT activity. However, when treated with 1 nM DHT, the CAT activity increased about 40-fold over the mock treatment (data not shown). Expression of either wild-type AR or ARA70 alone resulted in less than 1.5-fold activation even in the presence of androgen. We then tested six different antiandrogens and related compounds. As shown in Fig. 1B, the addition of 10 μM antiandrogens can induce the CAT activity 3–6-fold over the basal level in the presence of ARA70. We then extended these findings to two different AR mutants, mAR877 from prostate cancer and mAR708 from a partial androgen insensitivity syndrome patient. Similar results were obtained when mAR877 and ARA70 were cotransfected into DU145 cells (Fig. 1C). In contrast, although high induction (about 35-fold) was detected in the presence of 1 nM DHT (data not shown), there were no inductions by cotransfection with mAR708 and ARA70 in the presence of these six antiandrogens and related compounds (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that ARA70 directly interacts with wild-type AR and mAR877 in the presence of androgen or antiandrogens and that either the interaction between mAR708 and ARA70 is lost or the antiandrogen–mAR708–ARA70 complex may, somehow, be unable to induce AR target genes.

Figure 1.

Demonstration of a physical interaction between AR and ARA70 by mammalian two-hybrid assay in DU145 cells. (A) Schematic representation of the mammalian two-hybrid system. (B–D) ARA70 interacts with ARs in the presence of antiandrogens. CAT activity was determined in DU145 cells cotransfected with pGAL0–wild-type AR (B), pGAL0–mAR877 (C), or pGAL0–mAR708 (D), pVP16–ARA70, and pG5CAT reporter gene. After transfection, 0.1, 1, or 10 μM of various antiandrogens and related compounds were added. CAT activity with the mock treatment was set as 1-fold. Values are the means (±SD) of at least three determinations.

Effects of Antiandrogens on the Transcriptional Activity of the Wild-Type and Mutant ARs.

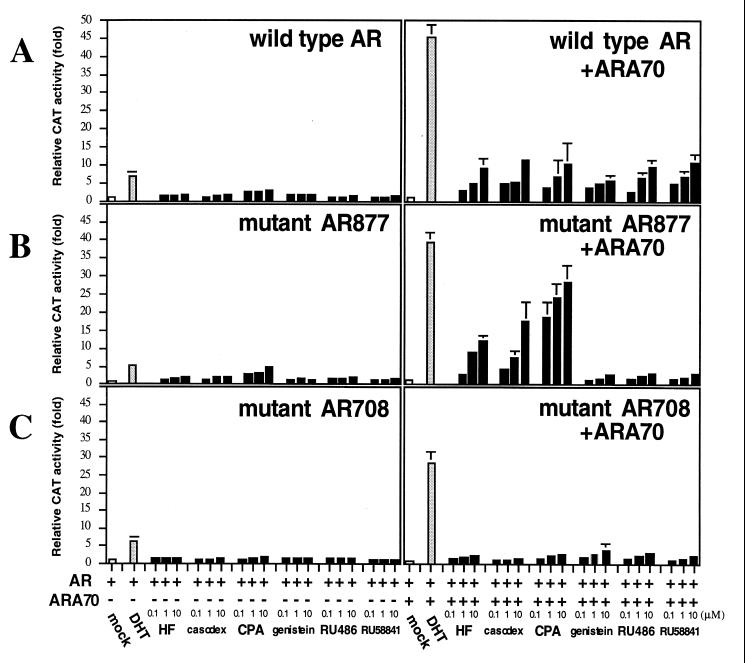

Prostate cancer patients with maximal androgen ablation therapy may have only minimal androgens and relatively higher concentrations of antiandrogens (as high as 1–5 μM) in their serum. To test the agonist activity of these antiandrogens in conditions close to the maximal androgen ablation therapy, we set up a prostate-transient transfection system as follows. The DU145 cells were cultured with charcoal-stripped serum in the presence of 0.1, 1, or 10 μM antiandrogen. Thus, the effects of the antiandrogens alone on the transcriptional activity of the AR could be examined in the presence or absence of ARA70. When the AR and/or ARA70 was transiently expressed in DU145 cells without adding androgen, there was no AR transcriptional activity. However, AR transcriptional activity could be induced 5–7-fold when AR (wild-type, mAR877, or mAR708) was expressed with 1 nM DHT. As shown in Fig. 2, ARA70 can further enhance the transcriptional activities of these ARs to 28–45-fold in the presence of 1 nM DHT. We then tested the six antiandrogens and related compounds in the absence of androgens. Upon the transfection of wild-type AR in the absence of ARA70, only marginal inductions (less than 3-fold) were detected in the presence of these antiandrogens (Fig. 2A). The addition of ARA70, at the ratio of 1:3 to AR, further enhanced the AR transcriptional activity to 5–12-fold. A similar induction pattern was observed when wild-type AR was replaced by mAR877 in the absence of ARA70 (Fig. 2B). However, the addition of ARA70 to HF, casodex, and CPA resulted in higher inductions (up to 30-fold in the case of CPA) with mAR877 as compared with wild-type AR. In contrast, genistein, RU486, and RU58841 had only marginal agonist activity (within 4-fold). In addition, as expected, these six antiandrogens and related compounds lost most agonist activity on mAR708 (Fig. 2C), whereas androgen response to this mutant (28-fold) was only slightly reduced as compared with the wild-type AR (45-fold) and mAR877 (39-fold).

Figure 2.

Transcriptional activity of the wild-type and mutant ARs in the presence of antiandrogens. CAT activity was determined in DU145 cells cotransfected with 3.5 μg of reporter plasmid MMTV–CAT and 1.5 μg of AR expression plasmids wild-type (A), mAR877 (B), or mAR708 (C) with or without 4.5 μg of ARA70. After transfection, cells were incubated without hormones (mock) or with 1 nM DHT or 0.1, 1, or 10 μM of various antiandrogens and related compounds for 24 h. The mock treatment was set as 1-fold. Values are the means (±SD) of at least three determinations.

Expression of AR Protein in the Presence or Absence of ARA70.

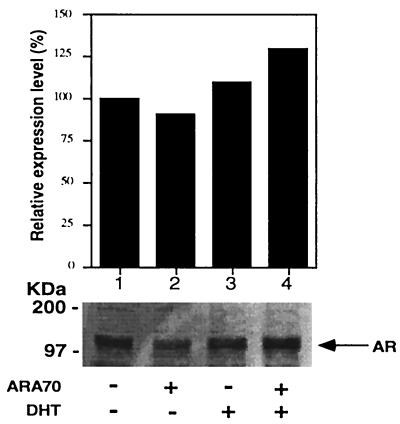

To rule out the possibility that the androgen- or antiandrogen-induced AR transcriptional activity in the presence of ARA70 is because of the change of AR protein expression, Western blot assay with cell extracts from DU145 was performed. As shown in Fig. 3, there was little change in AR expression when ARA70 was cotransfected in the presence or absence of DHT. Also, treatment of HF or casodex showed no significant differences of AR expression with or without transfected ARA70 (data not shown). These results indicate that enhanced transcriptional activity of AR by ARA70 in the presence of DHT or antiandrogens is not the result of the change of expression of AR protein.

Figure 3.

Western immunoblot analysis. Cell extracts from DU145 cells cotransfected with pSG5–wild-type AR with or without pSG5–ARA70 were analyzed on Western blots using a polyclonal antibody NH27 to the AR. The 110 kDa of protein was detected and quantitated. The expression level in lane 1 (mock treatment without cotransfection of ARA70) was set as 100%.

Conformational Changes of the Androgen-AR vs. Antiandrogen-AR.

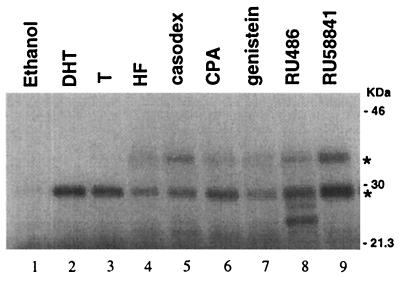

As antiandrogens, like androgens, can also activate AR target genes, we then analyzed whether androgen–AR and antiandrogen–AR might use the same activation pathway. Using a limited trypsinization assay, the results revealed that, in the presence of DHT or testosterone, a 29-kDa proteolysis resisting fragment was apparent (Fig. 4, lanes 2 and 3), whereas a specific 35-kDa fragment was also observed when antiandrogens were added (lanes 4–9). In addition, the presence of RU486 resulted in formation of two smaller fragments of the AR (lane 8). Androgens and several antiandrogens, such as HF, casodex, CPA, and RU486, were found to alter the conformation of the AR using this method (9, 32). These results match well with the previous reports (9, 32) that antiandrogens, such as HF, casodex, CPA, and RU486, can alter the AR conformation and suggest that the activation pathways between androgen–AR and antiandrogen–AR may be different.

Figure 4.

Androgen- and antiandrogen-specific conformational changes. In vitro translated AR was incubated with 10 nM DHT (lane 2), 100 nM testosterone (lane 3), various antiandrogens and related compounds (10 μM HF, 10 μM casodex, 1 μM CPA, 1 μM genistein, 1 μM RU486, and 1 μM RU58841, lanes 4 to 9), or 0.01% (vol/vol) ethanol (lane 1) for 30 min at room temperature prior to limited proteolytic digestion with trypsin. Digestion products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and visualized by autoradiography. Trypsin-resistant bands are indicated by asterisks. Molecular mass markers are indicated at the right.

AR:ARA70 Ratios.

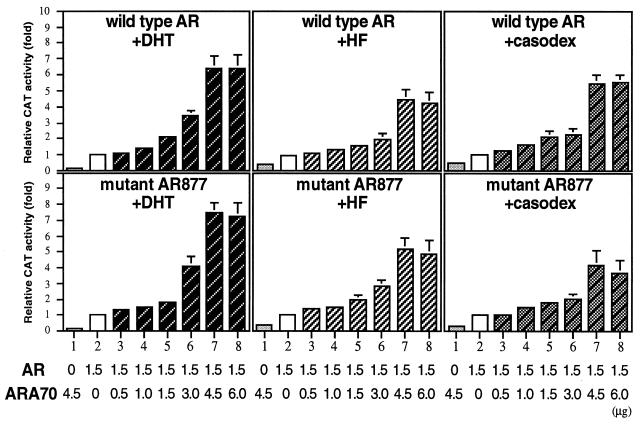

The next question we asked is “what is the right environment for antiandrogens to activate AR?” Previously, we demonstrated that maximal AR transcriptional activity induced by DHT was achieved by cotransfection of AR and ARA70 at 1:3 ratios (29). As shown in Fig. 5, maximal transcriptional activation of wild-type AR and mAR877 in the presence of 1 nM DHT was also obtained by the ratio of 1:3. To find the best ratio for the maximal agonist activity of antiandrogens, HF and casodex were tested. The results showed the similar tendency to those of DHT (Fig. 5). The agonist effects on the wild-type AR and mAR877 were increased by cotransfection of ARA70 in a dose-dependent manner, reaching a plateau at the ratio about 1:3 (up to 1:4). These results indicate that expression level of ARA70 compared with that of AR may play a critical role in the promotion of agonist activity of antiandrogens. Indeed, using in situ hybridization technique, our preliminary data suggest that ARA70 mRNA could be detectable in most of prostate cancer tissues (data not shown). More complete and detailed studies on the coexpression of ARA70 and AR in normal prostate as well as different grades and stages of prostate cancers may tell us the physiological roles of ARA70 in growth of the prostate.

Figure 5.

Effects of different AR:ARA70 ratios. Increasing amounts of pSG5-ARA70 (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 3.0, 4.5, and 6.0 μg) were cotransfected with 1.5 μg of AR (wild-type AR or mAR877) in DU145 cells in the presence of 1 nM DHT, 1 μM HF, or 1 μM casodex. CAT activity was represented as fold increase over the base line seen in each lane 2. Values represent the means (±SD) of at least three determinations.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed the molecular mechanism by which antiandrogens induce AR transcriptional activity in the absence of androgen in DU145 prostate cancer cells. Our results may have the following implications: 1) widely used nonsteroidal antiandrogens, such as casodex and HF, might not always act as “pure antiandrogens”; 2) ARA70 may play an important role in the promotion of agonist activity of antiandrogens; 3) mutations in the AR genes, such as mAR877 and mAR708, could still be involved in the promotion of agonist activity of antiandrogens. Together, these findings may offer possible explanations of the mechanisms for the “antiandrogen withdrawal syndrome.” Moreover, when prostate cancer patients are treated with the long-term use of high dose antiandrogens, consideration of the expression of AR and ARA70 in their tumors might be important.

The six antiandrogens and other related compounds tested in this study showed an agonist effect on wild-type AR and mAR877, but had no agonist effect on mAR708. The inability of mAR708 to respond to HF is also demonstrated in yeast growth assay (33). In addition, the crystal structure of the ligand binding domain of the steroid receptor has been recently studied (35–38). The ligand binding cavity is speculated to be formed by parts of helices H3–H12 and S1/S2 hairpin, and H3 is suggested to be essential for the formation of the ligand binding cavity. Codon 708 of the AR is located on H3 (38), and the substitution from glutamic acid to lysine is likely to influence the ligand binding. Although mAR708 has not been found in prostate cancer, antiandrogens may act as more “pure antiandrogens” without agonist activity in the presence of this mutation.

Recently, Katzenellenbogen et al. (39) proposed a new tripartite system (ligand–receptor–cofactor) to explain the molecular interactions of steroid receptors that may define the potency and biological character of steroid hormones. Several groups have also reported that the wild-type estrogen receptor and its mutants have either agonist or antagonist response to different antiestrogens in different cell environments. Additionally, the differing responses to estrogens and antiestrogens do not seem to be the result of a change in the estrogen receptor expression level or its binding affinity for ligands. Rather, their data support the hypothesis that different cells may provide different cell contexts, like cofactors, which may be able to interact with the estrogen–estrogen receptor or antiestrogen–estrogen receptor complexes, and subsequently activate or inhibit the transcriptional activity (40). Therefore, they proposed that agonist/antagonist–receptor interactions alone may not be able to control the response, and the interaction between ligand–receptor complexes and cofactors could be essential for steroid hormone function and sensitivity. Our findings that antiandrogens can activate androgen target genes in the presence of AR and ARA70 might represent direct evidence supporting the “tripartite receptor system” concept and indicate that the receptor specificity and biological diversity of the steroid hormone family can be generated at the level of cofactors.

In conclusion, our results indicate that ARA70 can enhance the agonist activity of antiandrogens via direct interaction with the AR. Thus, the interaction between AR and ARA70 may play an important role in the modulation of AR activity in human prostate cancer. Analysis of the AR:ARA70 expression ratio in prostate cancer tissues and dissection of the mechanism as to how ARA70 induces AR transcriptional activity may help to develop better antiandrogens without agonist activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. H. Uno, S. Balk, H. Shima, D. Chen, and C. Wang for providing antiandrogens or plasmids and helpful suggestions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA71570 and CA68568.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AR

androgen receptor

- HF

hydroxyflutamide

- CPA

cyproterone acetate

- CAT

chloramphenicol acetyltransferase

- DHT

dihydrotestosterone

References

- 1.Chang C, Kokontis J, Liao S T. Science. 1988;240:324–326. doi: 10.1126/science.3353726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans R M. Science. 1988;240:889–895. doi: 10.1126/science.3283939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landis S H, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo P A. Ca Cancer J Clin. 1998;48:6–29. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.48.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huggins C, Hodges C V. Cancer Res. 1941;1:293–297. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crawford E D, Eisenberger M A, McLeod D G, Spaulding J-T, Benson R, Dorr F A, Blumenstein B A, Davis M A, Goodman P J. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:419–424. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908173210702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilding G, Chen M, Gelmann E P. Prostate. 1989;14:103–115. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990140204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veldscholte J, Ris-Stalpers C, Kuiper G G J M, Jenster G, Berrevoets C, Claassen E, van Rooij H C J, Trapman J, Brinkmann A O, Mulder E. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:534–540. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong C, Kelce W R, Sar M, Wilson E M. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19998–20003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.19998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuil C W, Berrevoets C A, Mulder E. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27569–27576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh S, Miyamoto H, Chang C. Lancet. 1997;349:852–853. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61756-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly W K, Scher H I. J Urol. 1993;149:607–609. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scher H I, Kelly W K. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1566–1572. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.8.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly W K, Slovin S, Scher H I. Urol Clin North Am. 1997;24:421–431. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wirth M P, Froschermaier S E. Urol Res. 1997;25:67–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00941991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huan S D, Gerridzen R G, Yau J C, Stewart D J. Urology. 1997;49:632–634. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00558-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLeod D G. Cancer. 1993;71:1046–1049. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3+<1046::aid-cncr2820711424>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neumann F, Jacobi G H. J Clin Oncol. 1982;1:41–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verhelst J, Denis L, Vliet V, Poppel H V, Braeckman J, Cangh P V, Mattelaer J, D’Hulster D, Mahler C. Clin Endocrinol. 1994;41:525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1994.tb02585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furr B J A. Eur Urol. 1990;18:2–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naik H R, Lehr J E, Pienta K J. Anticancer Res. 1994;14:2617–2620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterson G, Barnes S. Prostate. 1993;22:335–345. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990220408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiechert R, Neef G. J Steroid Biochem. 1987;27:851–858. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(87)90159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein-Hitpass L, Cato A, Henderson D, Ryffel G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;19:1227–1234. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.6.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Battmann T, Branche B C, Humbert J, Goubet F, Teutsch G, Philibert D. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;48:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)90250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadi M V, Walsh P C, Barrack E R. Cancer. 1991;67:3057–3064. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910615)67:12<3057::aid-cncr2820671221>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chodak G W, Kranc D M, Puy L A, Takeda H, Johnson K, Chang C. J Urol. 1992;147:798–803. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37389-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaddiopati J P, McLeod D G, Heidenberg H B, Sesterhenn I A, Finger M J, Moul J W, Srivastava S. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2861–2864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taplin M-E, Bubley G J, Shuster T D, Frantz M E, Spooner A E, Ogata G K, Keer H N, Balk S P. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1393–1398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505253322101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeh S, Chang C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5517–5521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizokami A, Yeh S-Y, Chang C. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:77–88. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.1.8152432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allan G F, Leng X, Tsai S Y, Weigel N L, Edwards D P, Tsai M-J, O’Malley B W. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19513–19520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuil C, Mulder E. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1994;102:R1–R5. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C. Ph.D. thesis. Madison, WI: Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizokami A, Masai M, Shimazaki J, Sugita A. Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;83:1801–1807. doi: 10.5980/jpnjurol1989.83.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourguet W, Ruff M, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H, Moras D. Nature (London) 1995;375:377–382. doi: 10.1038/375377a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Renaud J-P, Rochel N, Ruff M, Vivat V, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H, Moras D. Nature (London) 1995;378:681–689. doi: 10.1038/378681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner R L, Apriletti J W, McGrath M E, West B L, Baxter J D, Fletterick R J. Nature (London) 1995;378:690–697. doi: 10.1038/378690a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wurtz J-M, Bourguet W, Renaud J-P, Vivat V, Chambon P, Moras D, Gronemeyer H. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:87–94. doi: 10.1038/nsb0196-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katzenellenbogen J A, O’Malley B W, Katzenellenbogen B S. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:119–131. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.2.8825552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montano M M, Muller V, Trobaugh A, Katzenellenbogen B S. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:814–824. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.7.7476965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]