Abstract

Chromosome segregation must be executed accurately during both mitotic and meiotic cell divisions. Sgo1 plays a key role in ensuring faithful chromosome segregation in at least two ways. During meiosis this protein regulates the removal of cohesins, the proteins that hold sister chromatids together, from chromosomes. During mitosis, Sgo1 is required for sensing the absence of tension caused by sister kinetochores not being attached to microtubules emanating from opposite poles. Here we describe a differential requirement for Sgo1 in the segregation of homologous chromosomes and sister chromatids. Sgo1 plays only a minor role in segregating homologous chromosomes at meiosis I. In contrast, Sgo1 is important to bias sister kinetochores toward biorientation. We suggest that Sgo1 acts at sister kinetochores to promote their biorientation.

INTRODUCTION

The principles governing meiotic chromosome segregation are similar to those during mitosis. However, in contrast to mitosis during which replicated pairs of sister chromatids segregate once, meiosis consists of two consecutive chromosome segregation phases. During the first meiotic division, homologous chromosomes segregate away from each other. The second segregation phase resembles mitosis, in that sister chromatids segregate to opposite poles.

The foundations for accurate chromosome segregation are laid during DNA replication, when protein complexes known as cohesins are loaded onto chromosomes (Blat and Kleckner, 1999; Ciosk et al., 2000; Laloraya et al., 2000; Glynn et al., 2004; Lengronne et al., 2004; Weber et al., 2004). After DNA replication, the newly duplicated DNA strands, the sister chromatids, are held together by these cohesins (Uhlmann and Nasmyth, 1998; Lengronne et al., 2006). During mitosis, cohesins facilitate the accurate attachment of sister chromatids to the mitotic spindle so that the kinetochores of sister chromatids attach to microtubules emanating from opposite poles (called biorientation). They do so by counteracting the pulling force exerted by microtubules on kinetochores, which creates tension at kinetochores. This tension is monitored by the cell and progression into anaphase only occurs when all microtubule—kinetochore attachments are under tension (reviewed in Pinsky and Biggins, 2005).

Microtubule–kinetochore attachments that are not under tension are severed in a manner that depends on the protein kinase Aurora B (Ipl1 in budding yeast; Biggins et al., 1999; Biggins and Murray, 2001; Tanaka et al., 2002; Pinsky et al., 2006). The severing of microtubule–kinetochore interactions by Ipl1 produces unattached kinetochores, which in turn causes activation of the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC; reviewed in May and Hardwick, 2006; Musacchio and Salmon, 2007). The SAC prevents entry into anaphase by inhibiting a ubiquitin ligase known as the anaphase-promoting complex (APC) bound to its specificity factor Cdc20 (APC-Cdc20). Thereby the checkpoint inhibits a cascade of events that leads to securin (Pds1 in budding yeast) degradation and cleavage of the cohesin subunit Scc1/Mcd1 by a protease known as separase (Esp1 in yeast).

The first meiotic division is unique in that homologues rather than sister chromatids segregate away from each other. This not only requires sister kinetochores to attach to microtubules emanating from the same pole (co-orientation), which is mediated by the monopolin complex (Toth et al., 2000), but also necessitates the generation of a physical linkage between homologous chromosomes to allow a tension-based mechanism to facilitate the accurate attachment of chromosomes onto the meiosis I spindle. Linkages between homologous chromosomes are provided by chiasmata, the products of meiotic recombination, which allow Ipl1-dependent mechanisms to facilitate the biorientation of homologous chromosomes on the meiosis I spindle (Monje-Casas et al., 2007). The SAC component, Mad2, also plays a role in promoting homolog biorientation during meiosis that is distinct from its role in halting the cell cycle in response to kinetochore–microtubule attachment defects (Shonn et al., 2003).

The cohesin complexes distal to chiasmata antagonize the pulling forces of the meiosis I spindle. The removal of cohesins along chromosome arms by separase therefore triggers the segregation of homologues during meiosis I. Cohesins around centromeres are however not removed during meiosis I, allowing sister chromatids to biorient on the meiosis II spindle (Klein et al., 1999; Watanabe and Nurse, 1999; Kiburz et al., 2005). Several factors have been identified that are required for preventing the removal of cohesins from centromeric regions during meiosis I. Among them are the Shugoshins (Sgo1 in budding yeast; Kerrebrock et al., 1992; Katis et al., 2004a; Kitajima et al., 2004; Marston et al., 2004). Schizosaccharomyces pombe or Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells lacking SGO1 lose all cohesins during meiosis I, causing random segregation of sister chromatids during meiosis II (Katis et al., 2004a; Kitajima et al., 2004; Marston et al., 2004). Sgo1 appears to prevent the removal of cohesins from centromeres during meiosis I, at least in part, by recruiting the protein phosphatase PP2A to this region where it is thought to antagonize the phosphorylation of cohesins (Brar et al., 2006; Kitajima et al., 2006; Riedel et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2006).

Fission yeast and mammalian cells contain two Sgo proteins (Kitajima et al., 2004, 2006). In S. pombe, Sgo1 regulates cohesin removal during meiosis. Sgo2 is required for sensing whether microtubule–kinetochore attachments are under tension during mitosis and meiosis through targeting Aurora B to kinetochores (Kawashima et al., 2007; Vanoosthuyse et al., 2007). Budding yeast Sgo1 is also required for tension sensing at kinetochores during mitosis, but it has not been shown whether it serves all of the functions of S. pombe Sgo1 and Sgo2 (Indjeian et al., 2005). Here we characterize the role of budding yeast Sgo1 during meiosis I chromosome segregation. We find that depletion of Sgo1 causes only few errors in chromosome segregation during the first meiotic division. However, Sgo1 appears important for sister kinetochore biorientation. Using an experimental setup in which microtubule–kinetochore attachments are under tension irrespective of whether sister kinetochores are co-oriented or bioriented, we find that Sgo1 is important for efficient sister kinetochore biorientation. Through this function, Sgo1 could aid in facilitating the attachment of chromosomes on the mitotic or meiosis II spindle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Plasmids

The strains used in this study are described in Table 1 and were derivatives of SK1. The pCLB2-CDC20 fusion and ubr1::kanMX4 are described in Lee and Amon (2003); REC8-13MYC, IML3-9MYC, and SGO1-9MYC in Marston et al. (2004); and NDC10-6HA, CENV green fluorescent protein (GFP) dots, mam1::TRP1, and PDS1-18MYC in Toth et al. (2000). REC8-3HA, spo13::hisG, and spo11::URA3 are described in Klein et al. (1999); the pCLB2-SGO1 fusion in Lee et al. (2004); and IPL1-13MYC in Monje-Casas et al. (2007). The REC8-N allele was described in Buonomo et al. (2000). The clb1::kanMX and rts1Δ::KanMX6 deletions were generated by the PCR-based gene replacement method described in Longtine et al. (1998). A PCR-based method was also used to generate the IPL1-6HA fusion (Knop et al., 1999).

Table 1.

Yeast strains

| Strain number | Relevant genotype |

|---|---|

| A2047 | MATa/α spo11Δ PDS1–18MYC |

| A4758 | MATa/α REC8–3HA |

| A4962 | MATa/α |

| A5715 | MATa/α tetR-GFP tetO-cenV/tetO-cenV |

| A5811 | MATa/α tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| A5823 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 PDS1–18MYC REC8–3HA |

| A6144 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 ubr1Δ REC8–3HA |

| A7118 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| A7316 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 mam1Δ tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| A8127 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 mam1Δ spo11Δ tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| A8441 | MATa/α REC8–13MYC NDC10–6HA |

| A8683 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 spo13Δ REC8–3HA PDS1–18MYC |

| A10461 | MATa/α SGO1–9MYC NDC10–6HA |

| A11252 | MATa/α pCLB2-SGO1 mam1Δ tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| A11255 | MATa/α pCLB2-SGO1 tetR-GFP tetO-cenV/tetO-cenV |

| A11951 | MATa/α clb1Δ clb4Δ REC8–13MYC NDC10–6HA |

| A11952 | MATa/α clb1Δ clb4Δ SGO1–9MYC NDC10–6HA |

| A11953 | MATa/α clb1Δ clb4Δ tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| A14502 | MATa/α pSCC1-IPL1 tetR-GFP tetO-cenV/tetO-cenV |

| A14900 | MATa/α tetR-GFP tetO-cenV/tetO-cenV |

| A14910 | MATa/α pCLB2-SGO1 REC8–3HA |

| A15500 | MATa/α spo11Δ mad2Δ PDS1–18MYC |

| A15501 | MATa/α spo11Δ pCLB2-SGO1 PDS1–18MYC |

| A15086 | MATa/α ubr1Δ REC8–3HA |

| A15163 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 tetR-GFP tetO-cenV/tetO-cenV |

| A15190 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 REC8-3HA PDS1-18MYC |

| A15269 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 PCLB2-SG01 ubr1Δ REC8–3HA |

| A15752 | MATa/α mad2Δ tetR-GFP tetO-cenV/tetO-cenV |

| A17314 | MATa/α clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| A17315 | MATa/α clb1Δ clb4Δ tetR-GFP tetO-cenV/tetO-cenV |

| A17615 | MATa/α clb1Δ clb4Δ pCLB2-SGO1 tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| A17616 | MATa/α clb1Δ clb4Δ pCLB2-SGO1 mam1Δ tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| A17826 | MATa/α PDS1–18MYC |

| A17838 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| A17839 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 tetR-GFP tetO-cenV/tetO-cenV |

| A17989 | MATa/α clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ PDS1–18MYC |

| A18021 | MATa/α mam1Δ PDS1–18MYC |

| A18088 | MATa/α clb1Δ clb4Δ PDS1–18MYC |

| A18089 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 IPL1–13MYC NDC10–6HA |

| A18102 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 IPL1–13MYC NDC10–6HA |

| A18229 | MATa/α pCLB2-SGO1 mam1Δ spo11Δ tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| A18705 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 mam1Δ tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| A18712 | MATa/α clb1Δ clb4Δ mad2Δ mam1Δ tetR-GFP tetO-cenV |

| AM3868 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 rts1Δ |

| AM3907 | MATa/α IPL1–6HA IML3–9MYC |

| AM3908 | MATa/α rec8Δ::REC8-N |

| AM3909 | MATa/α pCLB2-SGO1 rec8Δ::REC8-N |

| AM3952 | MATa/α pCLB2-SGO1 rec8Δ::REC8 |

| AM4041 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 |

| AM4236 | MATa/α pCLB2–3HA-SGO1 |

| AM4469 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 IPL1–6HA IML3–9MYC |

| AM4470 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 IPL1–6HA IML3–9MYC |

| AM4510 | MATa/α rec8Δ::REC8 |

| AM4511 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 rec8Δ::REC8 |

| AM4512 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 rec8Δ::REC8-N |

| AM4513 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 rec8Δ::REC8-N |

| AM4514 | MATa/α pCLB2-CDC20 rec8Δ::REC8 |

| AM4614 | MATa/α pCLB2-SGO1 IPL1–6HA IML3–9MYC |

Sporulation Conditions

Cells were grown to saturation in YPD (YEP + 2% glucose) for 24 h, diluted into YPA (YEP + 2% KAc) at OD600 = 0.3, and grown overnight. Cells were then washed with water and resuspended in SPO medium (0.3% KAc, pH = 7.0) at OD600 = 1.9 at 30°C to induce sporulation.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitations were performed as described in Lee et al. (2004). Sequences of primers are available upon request.

Whole Cell Immunofluorescence

Indirect in situ immunofluorescence was carried out as described in Visintin et al. (1998). Rat anti-tubulin antibodies (Oxford Biotechnology) and anti-rat FITC antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) were used at a 1:100 dilution. Pds1-18Myc was detected using a mouse anti-Myc antibody (Babco, Richmond, CA) at a 1:250 dilution and an anti-mouse Cy3 secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at a 1:1000 dilution for experiments in Figures 2 and 3. Pds1-18Myc was detected using a mouse anti-Myc antibody (Babco) at a 1:250 dilution and an anti-mouse Cy3 secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at a 1:250 dilution in the experiment described in Figure 5.

Figure 2.

Sgo1 is not required to sense tension at kinetochores during meiosis I. (A–D) Diploid spo11Δ (A2047), spo11Δ mad2Δ (A15500), and spo11Δ pCLB2-SGO1 (A15501) strains each carrying a PDS1–18MYC fusion were sporulated. (A) The percentage of mononucleate (■), binucleate (●), and tetranucleate (□) cells and binucleate cells containing Pds1 (○) was determined at the indicated time points for spo11Δ (top), spo11Δ mad2Δ (middle), and spo11Δ pCLB2-SGO1 (bottom) strains. (B) The percentage of binucleate cells that contain Pds1 is shown. At least 100 cells were counted from the 5-, 6-, and 7-h time points. (C) Examples of Pds1-positive (top) and Pds1-negative (bottom) cells are shown. Pds1 (red), tubulin (Tub; green), and a merged picture with DAPI (blue) are shown. (D) Western blot showing levels of Pds1 throughout the meiotic time course. Pgk1 was used as a loading control.

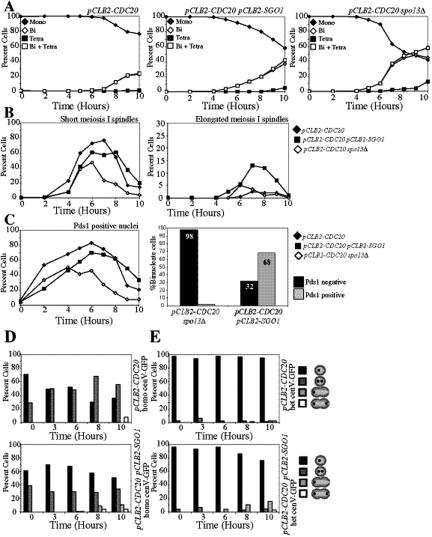

Figure 3.

Sgo1 depletion allows for spindle elongation despite APC inactivation. (A–C) Diploid pCLB2-CDC20 (A5823), pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 (A15190), and pCLB2-CDC20 spo13Δ (A8683) strains each carrying a PDS1–18MYC fusion were sporulated. (A) The percentage of mononucleate (♦), binucleate (◇), and tetranucleate (■) as well as the sum of binucleate and tetranucleate (□) was determined at the indicated time points for pCLB2-CDC20 (left), pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 (middle), and pCLB2-CDC20 spo13Δ (right) strains. (B) Metaphase I spindles (left) and anaphase I spindles (right) were counted for pCLB2-CDC20 (♦), pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 (■), and pCLB2-CDC20 spo13Δ (◇) strains. (C) The number of Pds1-positive and -negative cells for pCLB2-CDC20 (♦), pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 (■), and pCLB2-CDC20 spo13Δ (◇) strains was determined at the indicated times (left). The percentages of Pds1-positive and -negative binucleate cells are shown (right). (D and E) Diploid pCLB2-CDC20 and pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 strains were sporulated, and the percentage of mononucleate cells with one dot (black) and two dots (dark gray) as well as binucleate cells with one dot (light gray) and two dots (white) was counted. (D) pCLB2-CDC20 (A15163) and pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 (A17839) strains with homozygous CENV GFP dots are shown. (E) pCLB2-CDC20 (A7118) and pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 (A17838) strains with heterozygous CENV GFP dots are shown.

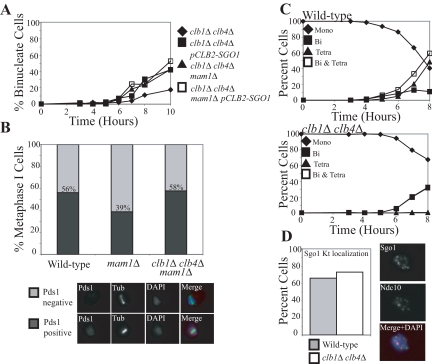

Figure 5.

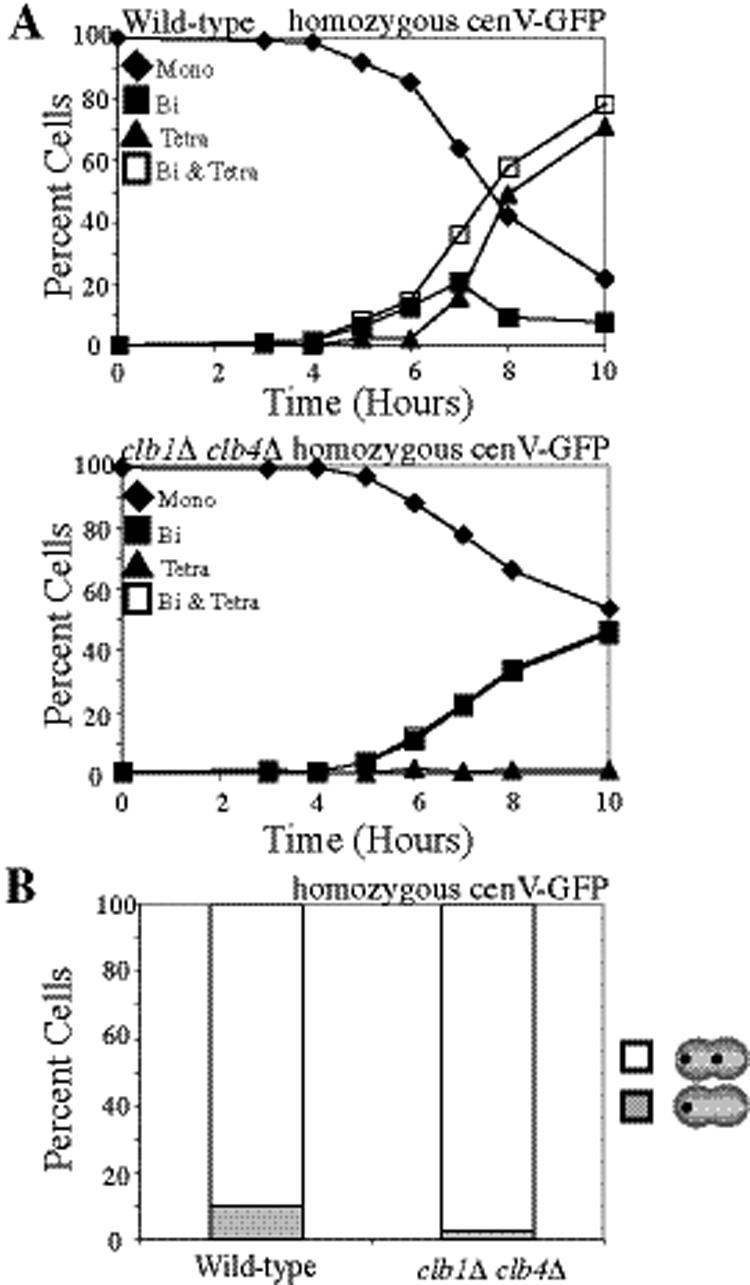

clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ cells lose all cohesion and Sgo1 during a single meiotic division. (A) clb1Δ clb4Δ (A11953), clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ (A17314), clb1Δ clb4Δ pCLB2-SGO1 (A17615), and clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ pCLB2-SGO1 (A17616) with heterozygous CENV GFP dots were sporulated. The percentage of binucleate cells is shown for clb1Δ clb4Δ (♦), clb1Δ clb4Δ pCLB2-SGO1 (■), clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ (▲), and clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ pCLB2-SGO1 (□) strains. (B) Wild-type (A17826), mam1Δ (A18021), and mam1Δ clb1Δ clb4Δ (A17989) cells each carrying PDS1-18MYC fusions were sporulated. The percentage of cells with short bipolar spindles that contain Pds1 was counted for wild-type, mam1Δ, and mam1Δ clb1Δ clb4Δ strains for four time points surrounding the peak of this cell population. At least 400 cells were counted for each strain. Examples of cells that lack (top) or contain (bottom) Pds1 are shown below the graph. Pds1, tubulin (Tub), and DAPI are shown in red, green, and blue, respectively. (C and D) Wild-type (A10461) and clb1Δ clb4Δ (A11952), carrying SGO1-9MYC and NDC10-6HA fusions were sporulated. (C) The percentage of mononucleate (♦), binucleate (■), and tetranucleated (▲) as well as the sum of binucleate and tetranucleated (□) was determined at the indicated time points for wild-type and clb1Δ clb4Δ strains. (D) The percentage of mononucleate cells with Sgo1 colocalizing with kinetochores is shown for wild-type (▩) and clb1Δ clb4Δ (□) strains. Cells were counted after 6 h of sporulation. An example of a mononucleate cell with Sgo1 colocalizing with Ndc10 is shown. Pictures with Sgo1, Ndc10, and a merged picture with Sgo1 in green, Ndc10 in red, and DAPI in blue are shown next to the graph.

Immunolocalization Analysis on Chromosome Spreads

Chromosomes were spread as described in Nairz and Klein (1997). Sgo1-9Myc and Rec8-13Myc were detected using rabbit anti-Myc antibodies (Gramsch, Schwabhausen, Germany) at a 1:300 dilution and anti-rabbit FITC antibodies (Jackson Immuno Research) at a 1:300 dilution. Ndc10–6HA was detected using a mouse anti-HA antibody (Babco) at a 1:250 dilution and an anti-mouse Cy3 antibody at a 1:300 dilution. Ipl1-6HA was detected using a mouse anti-HA antibody (Babco) at a 1:200 dilution and an anti-mouse Cy3 secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at a 1:300 dilution.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were harvested, incubated in 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and lysed as described in Moll et al. (1991). Immunoblots were performed as described in Cohen-Fix et al. (1996). Pds1-18Myc and Ipl1-13Myc were detected using a mouse anti-Myc antibody (Babco) at a 1:1000 dilution. Rec8-3HA and 3HA-Sgo1 were detected using a mouse anti-HA antibody (Babco) at a 1:1000 dilution. Pgk1 was detected using a mouse anti-PGK1 antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at a 1:5000 dilution. The secondary antibody used was a goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) at a 1:5000 dilution.

RESULTS

Depletion of Sgo1 Causes Errors in Meiosis I Chromosome Segregation

Sgo1 plays a critical role in meiosis II chromosome segregation but whether the protein was important for accurate meiosis I chromosome segregation had not been analyzed in detail. To examine meiosis I chromosome segregation in cells lacking Sgo1, we integrated an array of tet operator repeats near the centromere of both copies of chromosome V and expressed a tet-repressor-GFP fusion that binds to these operators (henceforth homozygous GFP dots). In wild-type cells the two copies of chromosome V segregated away from each other during the first meiotic division, producing cells with two nuclei (binucleate cells) each containing a GFP dot (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sgo1-depleted cells exhibit rare meiosis I segregation errors. Diploid wild-type (A14900), mad2Δ (A15752), pSCC-IPL1 (A14502), and pCLB2-SGO1 (A11255) strains each carrying homozygous CENV GFP dots were sporulated. Ipl1 was depleted during meiosis by placing the IPL1 open reading frame under the control of the mitosis-specific SCC1 promoter. Because Ipl1 is unstable during G1, Ipl1 is absent during meiosis in cells carrying the pSCC1-IPL1 fusion as the sole source of Ipl1 (Monje-Casas et al., 2007). The percentage of binucleate cells that had one or more dots in one nucleus (dark gray) and one or more GFP dots in both nuclei (light gray) is shown. At least 100 cells were counted from the 7-h time point.

To examine loss of Sgo1 function specifically during meiosis, we placed the SGO1 open reading frame under the control of the mitosis-specific CLB2 promoter. Because Sgo1 is unstable during G1 (Marston et al., 2004), Sgo1 is absent during meiosis in cells carrying the pCLB2-SGO1 fusion as the sole source of Sgo1 (Supplementary Figure 1). In cells depleted for Sgo1, homolog segregation occurred accurately in most cells, but in 10% of cells both homologues segregated to the same pole (Figure 1). In contrast, the absence of the SAC components Mad2 or Ipl1 leads to pronounced defects in meiosis I chromosome segregation (Figure 1; Shonn et al., 2003; Monje-Casas et al., 2007). The cosegregation of both homologues of chromosome V in 80% of cells depleted of IPL1 likely reflects a requirement for Ipl1 to sever the connections that both homologues make with the old spindle pole body after its duplication, allowing for proper biorientation (Monje-Casas et al., 2007). Loss of Mad2 led to cosegregation of homologues in ∼35% of cells (Shonn et al., 2003). These results suggest that Sgo1 is important for accurate meiosis I chromosome segregation. However, its role in the process appears less important than that of Ipl1 and Mad2, two other proteins involved in sensing whether kinetochores are under tension.

Sgo1 Is Not Essential for Sensing the Lack of Tension at Kinetochores Due to the Absence of Recombination

In mitotic cells lacking cohesins, microtubule–kinetochore attachments are not under tension. This leads to severing of microtubules by Ipl1, which in turn causes activation of the SAC and hence Pds1 stabilization (Stern and Murray, 2001). Cells lacking SGO1 do not delay Pds1 degradation in the absence of cohesins, indicating that during mitosis, Sgo1 is essential for sensing whether microtubule–kinetochore attachments are under tension (Indjeian et al., 2005). In meiosis I, the generation of tension at microtubule–kinetochore attachments requires the creation of a physical linkage between homologous chromosomes. This is brought about by homologous recombination. Deleting SPO11 abolishes recombination, thus causing the stabilization of Pds1 due to the lack of tension at kinetochores. However, because of the absence of linkages between homologues, spindle elongation occurs resulting in binucleate cells that contain Pds1 (Figure 2).

Inactivation of Ipl1 or the SAC (by deleting the checkpoint component MAD2) leads to Pds1 degradation in cells lacking SPO11 (V. Prabhu, personal communication; Shonn et al., 2003; Figure 2), indicating that also during meiosis I, Pds1 stabilization caused by the absence of tension at kinetochores is brought about by an Ipl1 and Mad2-dependent process. Depletion of Sgo1 led to only a slight reduction in the number of Pds1-positive binucleate spo11Δ cells (Figure 2, A–C). Furthermore, although Pds1 levels did decline in spo11Δ pCLB2-SGO1cells, it was significantly less dramatic than in spo11Δ cells lacking MAD2 (Figure 2D). We conclude that although SGO1 clearly contributes to Pds1 stabilization in the absence of recombination, its contribution is minor compared with Mad2 and Ipl1. Consistent with the idea that Sgo1 plays a minor role in tension sensing during meiosis I compared with Ipl1 and Mad2 is the observation that meiosis I chromosome segregation errors are observed much more frequently in cells lacking Ipl1 or Mad2 than in Sgo1-depleted cells (Figure 1; Monje-Casas et al., 2007). Thus, it appears that in contrast to S. pombe where Sgo2 is essential for sensing tension at kinetochores during meiosis I, budding yeast Sgo1 plays only a minor role in this process.

Metaphase I–arrested sgo1 Cells Exhibit Minor Defects in Kinetochore Orientation

A role for Sgo1 in homolog biorientation was also evident from the analysis of the effects of depleting Sgo1 in cells arrested in metaphase due to an inactive APC-Cdc20. Cells depleted for the APC activator Cdc20 (pCLB2-CDC20) arrest at metaphase I because they fail to degrade Securin (Figure 3, A and B; Lee and Amon, 2003). When Sgo1 was depleted in these cells, spindle elongation occurred, and cells with elongated or bilobed DAPI masses (henceforth binucleate cells) accumulated after prolonged periods of arrest (Figure 3, A and B). Similar results were obtained when we inactivated the PP2A-activating subunit RTS1 (Supplementary Figure 2), suggesting that Sgo1 prevents spindle elongation in Cdc20-depleted cells through its PP2A recruitment function.

Deletion of SPO13, a meiosis-specific gene important for the stepwise loss of cohesion and sister kinetochore co-orientation during meiosis I, also causes spindle elongation in Cdc20-depleted cells (Katis et al., 2004b; Figure 3, A and B). This bypass of the arrest is brought about by activation of the APC and is accompanied by the degradation of Pds1 (Katis et al., 2004b; Figure 3C). In pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 double mutants spindle elongation occurred in the absence of Pds1 degradation (Figure 3C), indicating that APC activation was not responsible for the bypass of the Cdc20 depletion arrest. Consistent with this conclusion is the observation that the cohesin subunit Rec8 was not cleaved in pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 cells (Supplementary Figure 3, A and B). Furthermore, a noncleavable version of Rec8 (Rec8-N; Buonomo et al., 2000) did not block spindle elongation in pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 cells (Supplementary Figure 3C). We also excluded the possibility that spindle elongation was a consequence of lower levels of cohesin loading (Supplementary Figure 4, A–E). We conclude that spindle elongation in pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 cells occurs in the absence of Pds1 degradation and Rec8 cleavage.

Because cohesin cleavage was not responsible for the spindle elongation observed in pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 cells, we next examined the possibility that kinetochore attachment errors were responsible for the failure of pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 cells to maintain a short metaphase I spindle. In pCLB2-CDC20 cells carrying homozygous GFP dots, two GFP dots became visible over time (Figure 3D), which is due to the stretching of homologous centromeres as they biorient on the meiosis I spindle. In the rare instances in which nuclei stretched to become bilobed a GFP dot was seen in each of the two nuclear lobes, indicating that homologues are continuously bioriented in Cdc20-depleted cells. In contrast, as binucleate cells accumulated in pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 cultures, a small fraction of cells showed both GFP dots in only one of the two nuclear lobes (Figure 3D). This finding indicates that a small fraction of homologues fail to biorient, resulting in the movement of both homologues to the same pole in pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 cells and allowing for spindle elongation to occur in the absence of APC-Cdc20 function (Figure 3D). Sister chromatids did not segregate prematurely in pCLB2-CDC20 pCLB2-SGO1 cells as judged by the analysis of cells in which only one of the two chromosomes was marked with a GFP dot (henceforth, heterozygous GFP dots; Figure 3E). We conclude that Sgo1 plays a minor role in the biorientation of homologues during meiosis I.

A Strain in Which Multiple Kinetochore–Microtubule Attachments Generate Tension

The observation that Sgo1 plays little role in biorienting homologues during meiosis I compared with the SAC component, Mad2 (Figure 1) but is as important as the SAC in biorienting sister chromatids during mitosis (Indjeian et al., 2005) raised the possibility that Sgo1 is more important for sensing tension between sister kinetochores than between kinetochores of homologues. An experimental system in which tension would be generated upon any type of kinetochore–microtubule attachment allowed us to test this possibility. We reasoned that in a strain that loses all cohesion during anaphase I and lacks a component of the monopolin complex, either homolog biorientation or sister kinetochore biorientation would be expected to generate tension (illustrated in Figure 4A). Moreover, chromosome segregation would be permitted in this system, once all chromosomes had established tension-generating attachments, allowing us to examine the outcome of these attachments in the progeny. Cells deleted for the B-type cyclins CLB1 and CLB4 as well as the monopolin complex component MAM1 provide this situation.

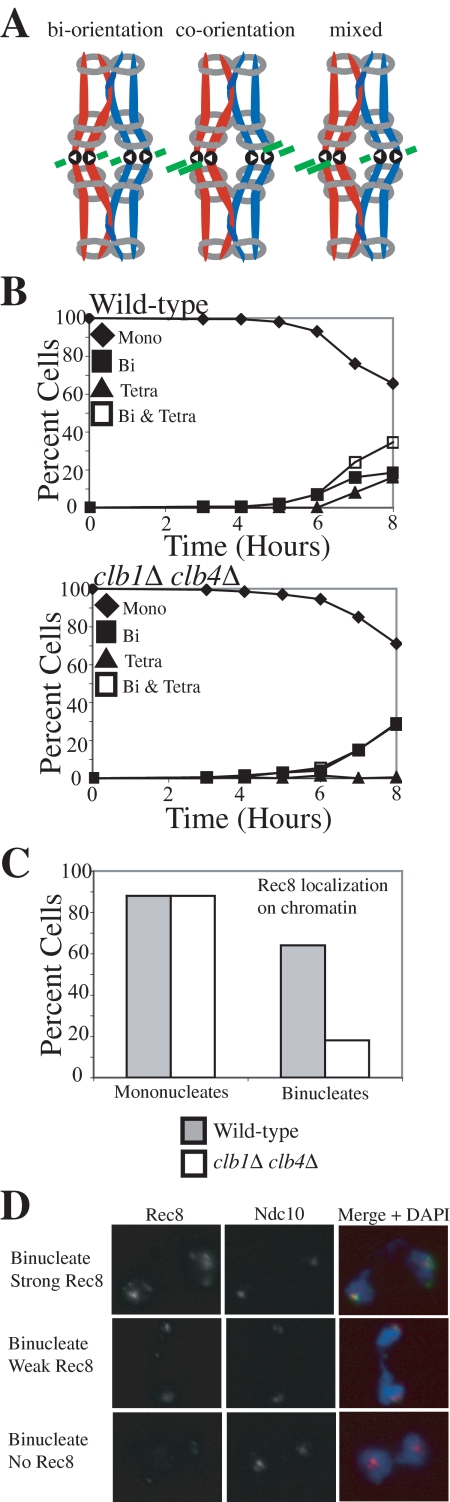

Figure 4.

clb1Δ clb4Δ cells lose all cohesin during a single meiotic division. (A) Diagram showing how any possible microtubule–kinetochore attachment will cause tension in cells lacking Mam1. (B–D) Wild-type (A8441) and clb1Δ clb4Δ (A11951) cells, carrying REC8-13MYC and NDC10-6HA fusions were sporulated. (B) The percentage of mononucleate (♦), binucleate (■), and tetranucleated (▲) as well as the sum of binucleate and tetranucleated (□) was determined at the indicated time points. (C) The percentage of mononucleate cells with Rec8 localized to chromatin is shown for wild-type (▩) and clb1Δ clb4Δ (□) strains along with the percentage of binucleate cells with Rec8 colocalizing with kinetochores. Mononucleate cells were counted after 6 h of sporulation, and binucleate cells were counted after 8 h of sporulation. (D) Examples of binucleates with strong, weak, and no Rec8 staining are shown. Rec8 (green), Ndc10 (red), and a merged picture with DAPI (blue).

Cells deleted for CLB1 and CLB4 undergo a single meiotic division and form two-spored asci (dyads) with viable spores, suggesting that homologues segregate correctly (Dahmann and Futcher, 1995). To determine whether Rec8 is lost from both chromosome arms and centromeric regions during this division we examined Rec8 localization in clb1Δ clb4Δ cells. Rec8 was present on chromosomes before the single meiotic divisions of clb1Δ clb4Δ cells (Figure 4, B–D). In contrast, whereas cohesin localized around centromeres in wild-type binucleate cells as judged by the colocalization of Rec8 with the kinetochore component Ndc10, the majority of clb1Δ clb4Δ binucleate cells lacked centromeric Rec8 (Figure 4, B–D). Our results suggest that Rec8 is lost along the entire length of the chromosome during the single meiotic division of clb1Δ clb4Δ cells.

It is possible that cohesins on chromosome arms are removed before centromeric cohesins but that this stepwise loss of cohesins was not detectable. We therefore conducted a functional test to examine whether cohesin loss was stepwise in clb1Δ clb4Δ cells. When MAM1 is deleted, cells biorient sister kinetochores during meiosis I but fail to segregate sister chromatids until the time when centromeric cohesins are removed. This not only causes cultures to delay in metaphase I but also leads to the accumulation of cells with metaphase I spindles that lack Pds1 staining because protected centromeric cohesin resists spindle forces even after Pds1 degradation (Toth et al., 2000). However, when all cohesion is lost in meiosis I, the spindle elongation delay of mam1Δ cells is abolished, and the fraction of metaphase I cells lacking Pds1 remains at wild-type levels (Toth et al., 2000; Katis et al., 2004a). clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ cells did not suffer a delay in the accumulation of binucleate cells compared with clb1Δ clb4Δ, clb1Δ clb4Δ pCLB2-SGO1, or clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ pCLB2-SGO1 cells, as all four strains began to accumulate binucleate cells at 6 h (Figure 5A). Furthermore, in contrast to mam1Δ cultures in which cells with short spindles lacking Pds1 accumulate, the fraction of cells with short spindles lacking Pds1 was similar in wild-type and clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ cells (Figure 5B). Together these results suggest that all cohesion is lost in the single meiotic division of clb1Δ clb4Δ cells.

To test whether the loss of centromeric cohesion during the single meiotic division of clb1Δ clb4Δ cells was due to loss of Sgo1 from centromeric regions, we analyzed Sgo1 localization in clb1Δ clb4Δ cells. Sgo1 localized to kinetochores in mononucleate clb1Δ clb4Δ cells but was largely absent in binucleate cells (Figure 5, C and D; data not shown). Thus, Sgo1 does not appear to be maintained at kinetochores past metaphase I, leading to the removal of all cohesin during the single division of clb1Δ clb4Δ cells.

Sgo1 Biases Sister Kinetochores toward Biorientation

Having a strain available in which sister kinetochores can be under tension irrespective of the way in which they attach to microtubules enabled us to examine how cells lacking the monopolin complex truly segregate after their attachment to the meiosis I spindle. This had not been possible before because in all previous analyses of kinetochore attachment in meiosis I mam1Δ cells either recombination or elements with potentially critical roles in kinetochore orientation such as SGO1 or SPO13 had been eliminated (Toth et al., 2000; Katis et al., 2004a,b; Lee et al., 2004).

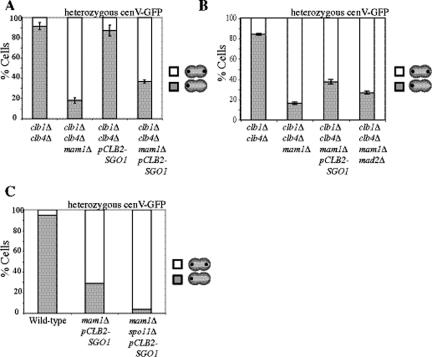

We first confirmed that clb1Δ clb4Δ cells segregate homologous chromosomes away from each other during the single meiotic division that these cells undergo using homozygous GFP dots (Figures 6; Dahmann and Futcher, 1995) and that sister chromatids cosegregated to the same pole during this division (Figure 7A). Deletion of MAM1 in these cells led 82% of cells to segregate sister chromatids to opposite poles, because clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ cultures carrying heterozygous GFP dots generated binucleate cells with a GFP dot in each nuclear lobe (Figure 7A). This result indicates that a strong bias toward sister kinetochore biorientation exists in a situation where other modes of kinetochore orientation could also generate tension.

Figure 6.

Homologous chromosomes are segregated to opposite poles during the single division of clb1Δ clb4Δ cells. (A and B) Wild-type (A5715) and clb1Δ clb4Δ (A17615) carrying homozygous CENV GFP dots were sporulated. (A) The percentage of mononucleate (♦), binucleate (□), and tetranucleated (▲) as well as the sum of binucleate and tetranucleated (□) was determined at the indicated time points for wild-type (top) and clb1Δ clb4Δ (bottom) strains. (B) Binucleate cells were counted for wild-type and clb1Δ clb4Δ strains with homozygous GFP dots from the above experiments. The number of cells with one dot in one nucleus (▩) and the percentage of cells with dots in both nuclei (□) were counted (n = 100).

Figure 7.

Sgo1 helps bias sister chromatids toward biorientation. (A) clb1Δ clb4Δ (A11953), clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ (A17314), clb1Δ clb4Δ pCLB2-SGO1 (A17615), and clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ pCLB2-SGO1 (A17616) with heterozygous CENV GFP dots were sporulated. Binucleate cells were counted for wild-type and clb1Δ clb4Δ strains heterozygous GFP dots from the same time course shown in Figure 5A. The number of cells with one dot in one nucleus (▩) and the percentage of cells with dots in both nuclei (□) were counted. Shown is the average of three experiments (n = 100); error bars, SDs. (B) clb1Δ clb4Δ (A11953), clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ (A17314), clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ pCLB2-SGO1 (A17616), and clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ mad2Δ (A18712), with heterozygous CENV GFP dots were sporulated. The number of cells with one dot in one nucleus (▩) and the percentage of cells with dots in both nuclei (□) were counted. Shown is the average of three experiments (n = 100); error bars, SDs. (C) Wild-type (A5811), mam1Δ pCLB2-SGO1 (A11252), and mam1Δ spo11Δ pCLB2-SGO1 (A18229) strains with heterozygous CENV GFP dots were sporulated. Shown is the percentage of binucleate cells with one dot in one nucleus (▩) and with dots in both nuclei (□). One hundred cells were counted for each strain from cells after 6 h of sporulation.

To address whether SGO1 plays a role in promoting sister kinetochore biorientation in clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ cells, we depleted the protein. In such cells biorientation of sister chromatids decreased from 82 to 63% (Figure 7A), suggesting that kinetochore–microtubule attachments now occurred in a more random manner. To determine whether this increase in sister kinetochore co-orientation in Sgo1-depleted cells was due to Sgo1's role in sensing whether or not sister kinetochores are under tension, we examined the effect of inactivating MAD2, another gene important for this process, on sister kinetochore orientation. Deletion of MAD2 also led to a decrease in sister kinetochore biorientation but the effects were less dramatic than of depleting Sgo1 (Figure 7B). It is thus possible that Sgo1's role in sensing whether or not kinetochores are under tension contributes to the biorientation of sister kinetochores in clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ cells. However, the fact that co-orientation occurred less frequently in cells lacking MAD2 than in Sgo1-depleted clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ cells indicates that Sgo1 participates in this process in an additional manner.

To conclusively determine whether Sgo1's role in sensing tension at sister kinetochores is necessary for biasing sister kinetochores toward biorientation, we examined the effects of eliminating recombination in mam1Δ pCLB2-SGO1 cells. If defects in sensing whether sister kinetochore attachments are under tension caused the near-random kinetochore attachment in SGO1-depleted cells, we would anticipate similarly random kinetochore attachments regardless of the attachment modes available for the generation of tension. Eliminating chiasmata by deleting SPO11 creates a situation in which tension can be achieved only by sister kinetochore biorientation. Strikingly, the near-random kinetochore attachment observed in mam1Δ pCLB2-SGO1 cells reverted to strictly bioriented attachments in mam1Δ spo11Δ pCLB2-SGO1 cells (Figure 7C). These results indicate that defects in tension sensing are not solely responsible for the reduction in sister kinetochore biorientation that we observed in SGO1-depleted cells. The implication is that a shift in the bias from sister kinetochore biorientation to other modes of tension-generating attachment occurs in Sgo1-depleted cells. We conclude that Sgo1 helps to bias sister kinetochores toward capturing microtubules from opposite poles.

Sister Kinetochore Biorientation Can Occur in the Absence of Sgo1 When Cells Are Arrested in Metaphase I

During mitosis, Sgo1 is important for promoting the biorientation of sister chromatids after mitotic spindle damage (Indjeian et al., 2005). In the absence of Sgo1, chromosomes are mis-segregated after transient treatment of cells with the microtubule-depolymerizing drug nocodazole. Delaying cells in metaphase upon removal of the drug suppresses the chromosome segregation defect of cells lacking Sgo1 (Indjeian et al., 2005). To test whether delaying the cell cycle also rescues the sister kinetochore biorientation defect of Sgo1-depleted cells during meiosis, we examined the effects of arresting cells in metaphase I on sister kinetochore orientation in mam1Δ pCLB2-SGO1 cells. mam1Δ cells carrying heterozygous GFP dots were arrested in metaphase I by depleting Cdc20. In this situation, kinetochores are under tension when sister kinetochores are bioriented (because cohesins would resist the pulling force of microtubules) or when sister kinetochores are co-oriented (because chiasmata would resist the pulling force of microtubules).

We first confirmed that pCLB2-CDC20 cells with intact monopolin arrest in metaphase I with co-oriented sister kinetochores. Thus, when only one chromosome is marked with a GFP dot, only one GFP dot is visible (Lee and Amon, 2003; Supplementary Figure 5). In contrast, a significant number of pCLB2-CDC20 mam1Δ cells contain two GFP dots after several hours (Supplementary Figure 5). This indicates that many sister kinetochores are bioriented in pCLB2-CDC20 mam1Δ cells, allowing microtubules to pull the GFP dots of sister chromatids away from each other (Supplementary Figure 5). We next analyzed GFP dot separation in a situation where tension could be generated only upon sister kinetochore biorientation. Cells deleted for SPO11 do not initiate recombination and hence form chiasmata, thereby eliminating linkages between homologues and the potential to generate tension upon homolog biorientation. Importantly, when SPO11 was deleted in pCLB2-CDC20 mam1Δ cells, separated GFP dots appeared at a similar rate and frequency as in pCLB2-CDC20 mam1Δ cells in which recombination occurs (Supplementary Figure 5). Thus, sister kinetochore biorientation occurs to the same extent in mam1Δ cells whether homolog biorientation can generate tension or not. These results are consistent with the idea that sister kinetochore biorientation is preferred over homolog biorientation in a situation where either scenario would generate tension. Our findings further indicate that, in the absence of co-orientation factors, mechanisms are in place that bias sister kinetochores toward biorientation.

We next asked if Sgo1 affects sister kinetochore orientation in this experimental set up. Depletion of Sgo1 did not decrease the biorientation of sister kinetochores in pCLB2-CDC20 mam1Δ cells (Supplementary Figure 5), indicating that as in mitosis, preventing cell cycle progression allows sister kinetochores to biorient even in the absence of Sgo1. We conclude that an inherent bias favors sister kinetochore biorientation over homolog biorientation and suggest that Sgo1 assists in generating this bias. However, additional mechanisms exist that promote biorientation in the absence of Sgo1 and become especially evident when cells are given more time for microtubule attachment.

DISCUSSION

Sgo1's Role in Meiosis I Chromosome Segregation

Sgo1 plays an important role in sensing whether kinetochore–microtubule attachments are under tension during mitosis (Indjeian et al., 2005). It was not known, however, if Sgo1 was also involved in tension sensing during meiosis I, when it is homolog pairs that must come under tension rather than sister chromatid pairs. We find that homologous chromosome pairs are mis-segregated in the absence of Sgo1, but infrequently. This contrasts with the high frequency of homolog cosegregation observed in cells lacking Mad2 or depleted for Ipl1, both of which play an important role in sensing lack of tension during meiosis I (Shonn et al., 2003; Monje-Casas et al., 2007). In support for Sgo1 having little role in tension sensing compared with SAC components during meiosis I, we found that that Pds1 was stabilized in the majority of cells in which kinetochores were not under tension because of the lack of physical linkages between homologues. These findings not only point to a differential requirement for Sgo1 and other SAC components in the tension sensing process but also suggest that during meiosis I additional mechanisms are in place that facilitate co-orientation of sister kinetochores and make Sgo1 less important for this process. The meiosis-specific protein Spo13 could be one such factor, because cells deleted for both SPO13 and MAM1 biorient sister kinetochores 100% of the time during meiosis I (Katis et al., 2004b; Lee et al., 2004).

Sister Kinetochore Biorientation Is Preferred over Homolog Biorientation

Our experiments with cells lacking MAM1, either in metaphase I–arrested cells or the clb1Δ clb4Δ background indicate that when multiple kinds of kinetochore–microtubule attachments could achieve tension, there is a strong bias toward sister kinetochore biorientation. Why is sister kinetochore biorientation favored above homolog biorientation? One possibility is that sister kinetochore biorientation generates tension more quickly because the kinetochores are closely linked. Tension generation upon homolog biorientation relies on chiasmata, which can be far from the centromere, so that kinetochores have to be pulled far apart before any tension is generated. This idea is supported by a recent study showing that chiasmata proximal to the centromere facilitate proper disjunction of homologous chromosomes during meiosis I in the absence of the SAC (Lacefield and Murray, 2007). Another explanation for the sister kinetochore biorientation bias is that the close coupling of sister kinetochores creates a more favorable geometry for their bipolar capture by microtubules. Taken together, our results further highlight the importance of the monopolin complex in overcoming the inherent bias toward sister kinetochore biorientation and ensuring that homolog biorientation is the only way to generate tension in meiosis I. Furthermore, a pathway promoting sister chromatid biorientation could provide an explanation for the observation that inactivation of the spindle assembly checkpoint has more severe effects during meiosis I than during mitosis (Shonn et al., 2003). A mechanism to bias sister kinetochores toward biorientation could reduce the need for a checkpoint that monitors accurate attachment of sister chromatids to the mitotic spindle.

Sgo1 Is Required for Efficient Sister Kinetochore Biorientation

What causes the bias toward sister kinetochore biorientation? We have obtained evidence that Sgo1 is one contributing factor. Cells deleted for CLB1 and CLB4 segregate chromosomes reductionally, but centromeric cohesins and Sgo1 were removed from chromosomes during this single division. This result not only raises the interesting possibility that Clb-CDKs prevent the removal of Sgo1 during meiosis I but also allowed us to investigate the role of Sgo1 in kinetochore orientation. The discovery that the biorientation of clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ cells is dependent on Sgo1 indicates that Sgo1 somehow biases sister chromatids toward biorientation. This finding also offers an explanation for the observation that sgo1Δ mam1Δ cells segregate chromosomes almost randomly during meiosis I (Katis et al., 2004a). Removal of all cohesins during meiosis I, as occurs in the absence of SGO1, would be expected to allow mam1Δ cells to segregate sister chromatids to opposite poles during meiosis I, rather than the random pattern observed (Katis et al., 2004a). Our results provide an explanation of this observation. Sgo1 facilitates the biorientation of sister kinetochores.

Our results also demonstrate that Sgo1 cannot be the only reason for the bias toward sister kinetochore biorientation, however. In a metaphase I arrest, cells lacking both MAM1 and SGO1 achieved a similar level of biorientation as cells lacking just MAM1. Similarly, delaying cells in metaphase during mitosis rescued the mis-segregation of sister chromatids in an sgo1 mutant after microtubule perturbation (Indjeian et al., 2005). These observations indicate that, when sufficient time is available, cells lacking Sgo1 can effectively biorient sister chromatids. How this occurs and whether other factors exist that promote biorientation of sister kinetochores in the absence of Sgo1 remains to be seen. We speculate that sister kinetochore geometry causes biorientation to be the preferred mode of attachment.

Does Sgo1 Contribute to Sister Kinetochore Biorientation through a Role in Tension Sensing?

During mitosis, Sgo1 plays an important role in sensing whether kinetochores are under tension (Indjeian et al., 2005). In S. pombe, Sgo2 is required to sense tension during both mitosis and meiosis I. This is likely explained by a requirement for Sgo2 in localizing Aurora B to kinetochores (Kawashima et al., 2007; Vanoosthuyse et al., 2007). Could Sgo1's role in promoting sister kinetochore biorientation be due to a defect in Ipl1 localization? Sgo1 has been reported to be required for full Ipl1 localization during anaphase I (Yu and Koshland, 2007). However, we found that Ipl1 levels did not change during meiosis and that Ipl1 localization was not dramatically affected (Supplementary Figure 6). We cannot exclude the possibility that small defects in Ipl1 localization occur in the absence of Sgo1, but localization is certainly not grossly affected, which is consistent with the observation that the phenotypes caused by the absence of Sgo1 are mild compared with those caused by the lack of Ipl1 function (Katis et al., 2004a; Marston et al., 2004; Indjeian et al., 2005; Monje-Casas et al., 2007).

Several lines of evidence further indicate that defects in sensing whether or not kinetochore attachments are under tension is not, or at least not the sole reason for the kinetochore orientation defect in cells lacking Sgo1. Tension sensing is intact in sgo1 mutants that contain kinetochores that are occupied by microtubules but not under tension (Pinsky et al., 2006). In contrast, tension sensing is defective in ipl1-321 mutants with these same kinetochore defects (Pinsky et al., 2006). Furthermore, importantly, the requirement for Sgo1 in promoting biorientation in clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ is independent of tension sensing. Chromosomes segregate almost randomly in clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ pCLB2-SGO1 and mam1Δ pCLB2-SGO1 cells. However, when the physical linkages between homologous chromosomes are eliminated (and hence tension on co-oriented sister kinetochores), chromosome attachments assume the only arrangement that will give rise to tension and revert to sister kinetochore biorientation in mam1Δ pCLB2-SGO1 spo11Δ cells. Therefore, the co-orientation that occurs when Sgo1 is depleted in clb1Δ clb4Δ mam1Δ cells is not due to a failure to sense tension but rather the removal of a bias to biorient sister kinetochores. It is, however, important to note that tension-sensing roles of Sgo1 could contribute to the biorientation of sister kinetochores (i.e., through small effects on Ipl1 localization or activity). In particular, it is possible that Sgo1 helps to distinguish between the tension generated by bioriented sister chromatids and bioriented homologues (see below).

Two general and not mutually exclusive models can be envisaged for how Sgo1 promotes sister kinetochore biorientation. One possibility is that Sgo1 causes kinetochores to take on a geometric configuration that favors biorientation. Through this mechanism, once a single kinetochore becomes attached to a microtubule, the kinetochore of the sister chromatid would be more likely to attach to a microtubule emanating from the opposite spindle pole. Alternatively, or in addition to a structural role, Sgo1 could participate in a tension-sensing mechanism. In this model, tension generation between bioriented sister chromatids is different from that of bioriented homologues because tension generation during homolog biorientation relies on chiasmata, which can be far from the centromere. Sgo1's role would be to help the tension sensing machinery to distinguish between sister chromatids and homologues being under tension. For example, bioriented homologous kinetochores could perhaps generate a weaker tension signal than bioriented sister chromatids and Sgo1 could selectively promote severing of these weaker kinetochore–microtubule attachments.

In preventing the removal of cohesins from centromeric regions during meiosis I, Sgo1 has been shown to function through PP2A (Riedel et al., 2006). It is possible that Sgo1 promotes sister kinetochore biorientation through this phosphatase too. This idea is supported by the observation that mam1Δ cells lacking the regulatory subunit RTS1 also segregate sister chromatids randomly during meiosis I (Riedel et al., 2006). Determining whether Sgo1 functions through dephosphorylating cohesins and/or other centromere proteins to promote biorientation will be an interesting avenue of future experimentation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Vineet Prabhu for communication of unpublished data. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM62207 (A.A.) and a Wellcome Trust Career Development Fellowship (A.M.). A.A. is also an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0584) on December 19, 2007.

REFERENCES

- Biggins S., Murray A. W. The budding yeast protein kinase Ipl1/Aurora allows the absence of tension to activate the spindle checkpoint. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3118–3129. doi: 10.1101/gad.934801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggins S., Severin F. F., Bhalla N., Sassoon I., Hyman A. A., Murray A. W. The conserved protein kinase Ipl1 regulates microtubule binding to kinetochores in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 1999;13:532–544. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.5.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blat Y., Kleckner N. Cohesins bind to preferential sites along yeast chromosome III, with differential regulation along arms versus the centric region. Cell. 1999;98:249–259. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brar G. A., Kiburz B. M., Zhang Y., Kim J. E., White F., Amon A. Rec8 phosphorylation and recombination promote the step-wise loss of cohesins in meiosis. Nature. 2006;441:532–536. doi: 10.1038/nature04794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonomo S. B., Clyne R. K., Fuchs J., Loidl J., Uhlmann F., Nasmyth K. Disjunction of homologous chromosomes in meiosis I depends on proteolytic cleavage of the meiotic cohesin Rec8 by separin. Cell. 2000;103:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciosk R., Shirayama M., Shevchenko A., Tanaka T., Toth A., Nasmyth K. Cohesin's binding to chromosomes depends on a separate complex consisting of Scc2 and Scc4 proteins. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:243–254. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80420-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Fix O., Peters J. M., Kirschner M. W., Koshland D. Anaphase initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is controlled by the APC-dependent degradation of the anaphase inhibitor Pds1p. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3081–3093. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmann C., Futcher B. Specialization of B-type cyclins for mitosis or meiosis in S. cerevisiae. Genetics. 1995;140:957–963. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.3.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn E. F., Megee P. C., Yu H. G., Mistrot C., Unal E., Koshland D. E., DeRisi J. L., Gerton J. L. Genome-wide mapping of the cohesin complex in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indjeian V. B., Stern B. M., Murray A. W. The centromeric protein Sgo1 is required to sense lack of tension on mitotic chromosomes. Science. 2005;307:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1101366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katis V. L., Galova M., Rabitsch K. P., Gregan J., Nasmyth K. Maintenance of cohesin at centromeres after meiosis I in budding yeast requires a kinetochore-associated protein related to MEI-S332. Curr. Biol. 2004a;14:560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katis V. L., Matos J., Mori S., Shirahige K., Zachariae W., Nasmyth K. Spo13 facilitates monopolin recruitment to kinetochores and regulates maintenance of centromeric cohesion during yeast meiosis. Curr. Biol. 2004b;14:2183–2196. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima S. A., Tsukahara T., Langegger M., Hauf S., Kitajima T. S., Watanabe Y. Shugoshin enables tension-generating attachment of kinetochores by loading Aurora to centromeres. Genes Dev. 2007;21:420–435. doi: 10.1101/gad.1497307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrebrock A. W., Miyazaki W. Y., Birnby D., Orr-Weaver T. L. The Drosophila mei-S332 gene promotes sister-chromatid cohesion in meiosis following kinetochore differentiation. Genetics. 1992;130:827–841. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.4.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiburz B. M., Reynolds D. B., Megee P. C., Marston A. L., Lee B. H., Lee T. I., Levine S. S., Young R. A., Amon A. The core centromere and Sgo1 establish a 50-kb cohesin-protected domain around centromeres during meiosis I. Genes Dev. 2005;19:3017–3030. doi: 10.1101/gad.1373005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima T. S., Kawashima S. A., Watanabe Y. The conserved kinetochore protein shugoshin protects centromeric cohesion during meiosis. Nature. 2004;427:510–517. doi: 10.1038/nature02312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima T. S., Sakuno T., Ishiguro K., Iemura S., Natsume T., Kawashima S. A., Watanabe Y. Shugoshin collaborates with protein phosphatase 2A to protect cohesin. Nature. 2006;441:46–52. doi: 10.1038/nature04663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein F., Mahr P., Galova M., Buonomo S. B., Michaelis C., Nairz K., Nasmyth K. A central role for cohesins in sister chromatid cohesion, formation of axial elements, and recombination during yeast meiosis. Cell. 1999;98:91–103. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80609-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knop M., Siegers K., Pereira G., Zachariae W., Winsor B., Nasmyth K., Schiebel E. Epitope tagging of yeast genes using a PCR-based strategy: more tags and improved practical routines. Yeast. 1999;15:963–972. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199907)15:10B<963::AID-YEA399>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacefield S., Murray A. W. The spindle checkpoint rescues the meiotic segregation of chromosomes whose crossovers are far from the centromere. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1273–1277. doi: 10.1038/ng2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laloraya S., Guacci V., Koshland D. Chromosomal addresses of the cohesin component Mcd1p. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151:1047–1056. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.5.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B. H., Amon A. Role of Polo-like kinase CDC5 in programming meiosis I chromosome segregation. Science. 2003;300:482–486. doi: 10.1126/science.1081846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B. H., Kiburz B. M., Amon A. Spo13 maintains centromeric cohesion and kinetochore coorientation during meiosis I. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:2168–2182. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengronne A., Katou Y., Mori S., Yokobayashi S., Kelly G. P., Itoh T., Watanabe Y., Shirahige K., Uhlmann F. Cohesin relocation from sites of chromosomal loading to places of convergent transcription. Nature. 2004;430:573–578. doi: 10.1038/nature02742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengronne A., McIntyre J., Katou Y., Kanoh Y., Hopfner K. P., Shirahige K., Uhlmann F. Establishment of sister chromatid cohesion at the S. cerevisiae replication fork. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:787–799. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine M. S., McKenzie A., 3rd, Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., Pringle J. R. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston A. L., Tham W. H., Shah H., Amon A. A genome-wide screen identifies genes required for centromeric cohesion. Science. 2004;303:1367–1370. doi: 10.1126/science.1094220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May K. M., Hardwick K. G. The spindle checkpoint. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:4139–4142. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll T., Tebb G., Surana U., Robitsch H., Nasmyth K. The role of phosphorylation and the CDC28 protein kinase in cell cycle-regulated nuclear import of the S. cerevisiae transcription factor SWI5. Cell. 1991;66:743–758. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90118-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monje-Casas F., Prabhu V. R., Lee B. H., Boselli M., Amon A. Kinetochore orientation during meiosis is controlled by Aurora B and the monopolin complex. Cell. 2007;128:477–490. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A., Salmon E. D. The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;8:379–393. doi: 10.1038/nrm2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairz K., Klein F. mre11S—a yeast mutation that blocks double-strand-break processing and permits nonhomologous synapsis in meiosis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2272–2290. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.17.2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky B. A., Biggins S. The spindle checkpoint: tension versus attachment. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:486–493. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky B. A., Kung C., Shokat K. M., Biggins S. The Ipl1-Aurora protein kinase activates the spindle checkpoint by creating unattached kinetochores. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:78–83. doi: 10.1038/ncb1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel C. G., et al. Protein phosphatase 2A protects centromeric sister chromatid cohesion during meiosis I. Nature. 2006;441:53–61. doi: 10.1038/nature04664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonn M. A., Murray A. L., Murray A. W. Spindle checkpoint component Mad2 contributes to bi-orientation of homologous chromosomes. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1979–1984. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern B. M., Murray A. W. Lack of tension at kinetochores activates the spindle checkpoint in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:1462–1467. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00451-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T. U., Rachidi N., Janke C., Pereira G., Galova M., Schiebel E., Stark M. J., Nasmyth K. Evidence that the Ipl1-Sli15 (Aurora kinase-INCENP) complex promotes chromosome bi-orientation by altering kinetochore-spindle pole connections. Cell. 2002;108:317–329. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z., Shu H., Qi W., Mahmood N. A., Mumby M. C., Yu H. PP2A is required for centromeric localization of Sgo1 and proper chromosome segregation. Dev. Cell. 2006;10:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth A., Rabitsch K. P., Galova M., Schleiffer A., Buonomo S. B., Nasmyth K. Functional genomics identifies monopolin: a kinetochore protein required for segregation of homologs during meiosis I. Cell. 2000;103:1155–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F., Nasmyth K. Cohesion between sister chromatids must be established during DNA replication. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanoosthuyse V., Prykhozhij S., Hardwick K. G. Shugoshin2 regulates localization of the chromosomal passenger proteins in fission yeast mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:1657–1669. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin R., Craig K., Hwang E. S., Prinz S., Tyers M., Amon A. The phosphatase Cdc14 triggers mitotic exit by reversal of Cdk-dependent phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:709–718. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y., Nurse P. Cohesin Rec8 is required for reductional chromosome segregation at meiosis. Nature. 1999;400:461–464. doi: 10.1038/22774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S. A., Gerton J. L., Polancic J. E., DeRisi J. L., Koshland D., Megee P. C. The kinetochore is an enhancer of pericentric cohesin binding. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. G., Koshland D. The Aurora kinase Ipl1 maintains the centromeric localization of PP2A to protect cohesin during meiosis. J. Cell Biol. 2007;176:911–918. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.