Abstract

Methadone is the therapeutic agent of choice for treatment of the pregnant opiate addict. However, little is known on the factors affecting its concentration in the fetal circulation during pregnancy and how it might relate to neonatal outcome. Therefore, a better understanding of the function of placental metabolic enzymes and transporters should add to the knowledge of the role of the tissue in the disposition of methadone and its relation to neonatal outcome. We hypothesized that the expression and activity of the placental efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp) would affect the transfer of methadone to the fetal circulation. Data obtained utilizing dual perfusion of placental lobule and monolayers of Be–Wo cell line indicated that methadone is extruded by P-gp. Transfer of methadone to the fetal circuit was increased by 30% in the presence of the P-gp inhibitor GF120918 while the transfer of paclitaxel, a typical substrate of the glycoprotein, was increased by 50%. In the Be–Wo cell line, methadone and paclitaxel uptake was also increased in the presence of the P-gp inhibitor cyclosporin A. Moreover, the expression of P-gp in placental brush–border membranes varied between term placentas. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that the concentration of methadone in the fetal circulation is affected by the expression and activity of P-gp. It is reasonable to speculate that placental disposition of methadone affects its concentration in the fetal circulation. If true, this may also be directly related to the incidence and intensity of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS).

Keywords: P-Glycoprotein, Human placenta, Methadone, Dual perfusion, Transplacental transfer

1. Introduction

Methadone is, and has been for several decades, the only approved pharmacotherapeutic agent for treatment of the pregnant opiate addict in the United States. Numerous investigations have indicated that methadone treatment programs improve maternal and neonatal outcome of this patient population; a review of this literature would be out of the scope of this report. However, a controversy exists regarding the association of methadone pharmacotherapy with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) [1,2] and whether the dose administered correlates with the incidence and intensity of the syndrome [1–4]. The variability in the efficacy of methadone among nonpregnant patients could be attributed to the factors affecting its disposition, which include maternal clearance, bioavailability, and metabolism by the liver and intestine. For the pregnant patient, other factors include fetal and placental clearance and metabolism. Our working hypothesis is that the placenta contributes to the disposition of a drug during pregnancy by virtue of its role as a functional barrier that protects the fetus from exposure to xenobiotics. Two reports from our laboratory about methadone provided evidence supporting this hypothesis. In the first report, cytochrome P 450 (CYP 19/aromatase) was identified as the major enzyme responsible for the metabolism of methadone to 2-ethylidene-1,5-dimethyl-3,3-diphenylpyr-rolidine (EDDP) in term placentas obtained from healthy pregnancies [5]. In the second report, the transfer rate of methadone from the maternal to fetal circuit of the dually perfused placental lobule was lower than that in the opposite direction suggesting that the efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp) might be involved [6]. Taken together, the data obtained suggested that the kinetics for transplacental transfer of methadone and its amount in the fetal circulation is determined by the sum of three processes: simple diffusion, carrier-mediated uptake or efflux, and biotransformation by the tissue’s metabolic enzymes.

The efflux transporter P-gp is a glycoprotein product of the multidrug resistance gene (MDR1) with a molecular weight of 170 kDa. Its role in extrusion of anticancer drugs from cells with intrinsic and acquired resistance is well documented. P-gp is expressed in various normal human tissues such as brain capillary endothelial cells that are part of the blood–brain barrier and the brush–border membrane of the intestine; this expression provides indirect evidence that it protects the body from xenobiotics [7]. Of particular interest to this investigation is the identification of P-gp in placental trophoblast tissue brush–border membranes [8]. Vesicle preparations from trophoblast tissue were used to provide evidence for the function of P-gp [9]. P-gp exhibits very broad substrate structure specificity and interacts with many xenobiotics and drugs including methadone [10]. In choriocarcinoma epithelial cell culture of the trophoblast-like cell line (Be–Wo), higher transfer of the P-gp substrates digoxin, vinblastine, and vincristine was reported more often in the basolateral-to-apical (fetal to maternal) than in the apical-to-basolateral [11]. However, in the human colon adenocarcinoma cell line (Caco-2), the rate of methadone transfer in both directions was similar [12]. Therefore, the goal of this investigation was to determine whether the activity of placental P-gp, localized on the brush–border membrane of human trophoblast cells, might affect the transfer rate and amounts of methadone in the fetal circuit of the dually perfused placental lobule. The effect of placental P-gp on the transfer of methadone was investigated utilizing two methods. The first method is the technique of dual perfusion of a term placental lobule in the absence and presence the P-gp inhibitor GF120918. The second method is the uptake of the opiate by Be–Wo cell line. GF120918 is an acridine carboxamide derivative that belongs to the second generation of P-gp antagonists, which inhibits the efflux of its substrates [13,14], and a recent report indicated that it significantly increased the transfer of paclitaxel (Taxol) into the brain [15]. Paclitaxel is a chemotherapeutic drug and a substrate of P-gp [7]. Therefore, its transplacental transfer was compared with methadone utilizing two in vitro methods and is reported here.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

P-gp inhibitor GF120918 was a generous gift from GlaxoSmithKline, Philadelphia, PA. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise mentioned. The opiates buprenorphine (BUP), levo-α-acetylmethadol (LAAM) and methadone and their tritiated isotopes were a gift from the National Institute on Drug Abuse drug supply unit. [3H]-Verapamil (85 Ci/mmol) was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc. (St. Louis, MO). Paclitaxel and paclitaxel [o-benzamido-3H] (41 Ci/mmol) were purchased from Moravek Biochemicals, Inc. (Brea, CA).

The murine monoclonal antibodies (mAb C219) were purchased from Signet Laboratories (Dedham, MA). Actin (C-2) mouse monoclonal antibodies and goat antimouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA).

2.2. Clinical material

Placentas from term healthy pregnancies were obtained upon delivery according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX. Placentas of women who abused drugs during pregnancy were excluded from the investigation.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Preparation of human placental brush–border membranes

Brush–border membranes were prepared according to the method described by Smith et al. [16] and modified by Booth et al. [17]. Briefly, after removal of the umbilical cord and amniotic membranes, tissue pieces weighing 20–30 g were dissected and washed four times with cold (4 °C) phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 83 mM NaCl, 22.2 mM Na2HPO4, 5.5 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4). The tissue was minced, stirred for 1 h and filtered through nylon mesh. The filtrate was centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 min, and the pellet discarded. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min, the pellet re-suspended in 30 mL Tris–mannitol buffer (300 mM mannitol, 2 mM Tris–base, pH 7.0) and homogenized. The homogenate was stirred on ice for 10 min after the addition of 0.6 mL of 1 M MgCl2. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 2200 × g for 12 min, and the supernatant was re-centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min. The resulting pellet was re-suspended in buffer (250 mM sucrose, 100 mM KNO3, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES/Tris, pH 7.4), and its protein content was determined using a Bio-Rad kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. All steps were performed at 4 °C.

2.3.2. ATPase assay

The verapamil-stimulated vanadate-sensitive ATPase activity kit (Gentest Corporation, Woburn, MA) was used to determine the interaction of opiates with P-gp. The kit is based on the method described by Sarkadi et al. [18]. Human P-gp membranes, 40 μg membranes/20 μL, were incubated in the presence of 20 μM verapamil (20 μL) as a positive control or an opioid at a final concentration of 20 μM with 20 μL of 4 mM MgATP. The reaction mixture included the following components at their indicated final concentrations: 50 mM Tris–Mes buffer, 2 mM EGTA, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 5 mM sodium azide. The total volume of the reaction was 60 μL and was incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. An identical reaction mixture containing 100 μM sodium orthovanadate, a selective inhibitor of the P-gp-coupled ATPase, was simultaneously carried out to determine the ATPase activity in the presence and absence of orthovanadate to obtain the vanadate-sensitive ATPase activity. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 30 μL 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) + Antifoam A. The other two reaction mixtures were either in the presence or absence of orthovanadate, and the absence of Mg-ATP represented “0” time conditions. The liberated inorganic phosphate was determined by the formation of a complex due to the addition of 2 volumes of 35 mM ammonium molybdate in 15 mM zinc acetate: 10% ascorbic acid (1:4, v/w). The intensity of the color was determined at 800 nm after incubation for 20 min at 37 °C using a phosphate standard curve.

2.3.3. Radioligand binding assay

Verapamil binding to P-gp expressed in trophoblast tissue brush–border membrane preparations was used to determine whether methadone competes for the same site on the efflux transporter using a radioligand assay based on a description by Doppenschmitt et al. [19]. The assay was composed of the following: 250 μg brush–border membrane proteins, a range of methadone concentrations from 0.1 to 300 μM, 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) to a final volume of 0.5 mL, and tritium-labeled verapamil at specific activity of 85 Ci/mmol. The final concentration of [3H]-verapamil was 5 nM and its specific binding was calculated from the difference between that in presence and absence of 1 mM Rhodamine123 [19]. The components of the binding assay were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and terminated by rapid filtration using a cell harvester (Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD) and glass fiber filters (#32; Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) presoaked in polyethylenimine. The filters were dried under a heat lamp and placed in scintillation vials; cocktail fluid was added, and the radioactivity was determined.

2.3.4. Dual perfusion of placental lobule

The method used is that by Miller et al. [20] and as described in details in a previous report from our laboratory [21]. Briefly, each placenta was examined for tears, and vessels supplying a single peripheral cotyledon were cannulated with umbilical catheters. The selected lobule was placed, maternal side up, in the perfusion chamber. Perfusion was initiated by inserting two catheters into inter-villous space on the maternal side. The perfusate was made of tissue culture medium M199 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with Dextran 40; 25 IU/mL heparin; 40 mg/L gentamicin sulfate; and sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprin, 80 and 16 mg/L, respectively. The fetal perfusate was equilibrated with a gas mixture of 95% N2 and 5% CO2 and the maternal with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Each placenta was perfused for an initial control period of 2 h, i.e., in absence of methadone, to evaluate the physical integrity of the tissue. An experiment was terminated if one or more of the following criteria were observed: fetal artery pressure reaching 50 mmHg, a loss in the volume of transfused medium in the fetal circuit >2 mL/h, and/or a difference between pO2 in the fetal vein and artery <60 mmHg. Each experimental period was started by replacing the perfusion medium in the fetal and maternal reservoirs and adding methadone or paclitaxel to the maternal reservoir at their final concentrations of 200 and 85 ng/mL, respectively. The placentas perfused with either methadone or paclitaxel in the absence of the P-gp inhibitor represented the control group. The transfer rate of methadone or paclitaxel from the maternal to the fetal circuit was determined under steady-state conditions by utilizing the model system in its open–open configuration; i.e., both the maternal and fetal circuits were not recirculated. The transfer parameters determined in the control group of placentas served as a base line for the experimental group of placentas. This experimental group was transfused with the same concentration of methadone or paclitaxel but in the presence of the P-gp inhibitor GF120918 at its final concentration of 1 μM [22]. The inhibitor was added to the maternal reservoir 30 min before methadone or paclitaxel was added. Antipyrine (AP; 20 μg/mL) was co-transfused in all experiments as a marker compound to account for interplacental variations. The radioactive isotopes of all the drugs ([3H]-methadone, [3H]-paclitaxel, and [14C]-AP) were added in their respective experiments to the maternal reservoir (6 μCi of each) to increase their detection limits. Samples from the maternal and fetal perfusates were collected at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, 75, 90, 105, and 120 min to determine their content of the drugs and other variables. The transfer parameters were calculated according to the following equations: fetal transfer rate (Trf) = [CFv/CMa] × 100%, where CFv and CMa are venous fetal and arterial maternal concentrations of the drug; clearance (Cl) = (CFv/CMa) × Qf (mL/min), where the fetal perfusion rate (Qf) is 3 mL/min; clearance index (Clindex) = Trf drug/Trf AP.

2.3.5. Be–Wo cells

The Be–Wo cell line (clone b30) was obtained from Dr. Alan Schwartz (Washington University, St. Louis, MO). Passage 29–40 of the cells were used in this study and cultured as described previously [23]. Briefly, the cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Sigma) adjusted to pH 7.4 and containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA), and 1% each of 200 mM (100×) L-glutamine, 10,000 units/mL penicillin with 10 mg/mL streptomycin, and 10 mM (100×) MEM nonessential amino acids solution (all three from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in 150 cm2 flasks under 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity; the media was changed every other day. Cells were harvested with trypsin–ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA) solution (Sigma) diluted in PBS (129 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 7.4 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.3 mM KH2PO4 adjusted to pH 7.4).

Prior to seeding Be–Wo cells in 24-well tissue culture plates, the plates (Corning Costar, Corning, NY) were prepared by coating each well in a 24-well plate with 70 μL of a 5 μg/mL poly-D-lysine (Sigma) solution in 28% ethanol. The plates were then dried and sterilized under fluorescent light. The plates were then coated with fibro-nectin (Sigma) solution in PBS are added to each well in 12-well plates (two drops were added in 24-well plates). Immediately prior to cell seeding, each well was rinsed with DMEM. Be–Wo cells were seeded in the plates as described previously [23] at a density of 12,500 cells/cm2. The cells were incubated and media changed every other day until 100% confluent (4–6 days).

The uptake experiments in Be–Wo cells were carried out as described previously [23]. The cells were washed three times with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS, Sigma) and then equilibrated in HBSS at 37 °C for approximately 45 min. [3H]-Methadone (20 nM) or [3H]-paclitaxel was premixed with (or without) selected inhibitors (e.g., 100 μM unlabeled methadone or 10 μM Cyclosporin A) in warm HBSS and was added to the cells in a shaking hot box (37 °C) for 30 min. The dosing solutions were then aspirated, the cells were washed with ice-cold HBSS three times before the lysing solution (0.5% Triton X-100 in 0.2 N NaOH) was added, and the plate continued to shake in the hot box for approximately 3 h. Samples of the lysate were then collected for scintillation spectrometry (Beckman LS 60001C, Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA) or protein assay using a kit from Pierce (Rockford, IL) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

2.3.6. Western blot analysis of P-glycoprotein

The brush–border membranes were prepared by differential centrifugation of trophoblast tissue homogenates as described above. Identification of P-gp expression was carried out using 7.5% SDS/polyacrylaminde gel electrophoresis. The amount of sample protein loaded on each well was 10 μg. At the end of electrophoresis, the gel was electroblotted on nitrocellulose membranes overnight at 4 °C and a constant potential of 25 V. Blots were probed with primary murine monoclonal antibodies (mAb C219, Signet Laboratories, Dedham, MA) diluted 1:200 and secondary goat antimouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies diluted 1:1000 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) Detection of the protein bands was carried out by spot densitometry and digital imaging (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leanrdo, CA) of the enhanced chemiluminescence spots (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The amount of expressed β-actin was used to normalize the amount of P-gp in each loaded sample on the gel. A positive control was made of human P-gp or MDR1 membranes (Gentest Corporation, Woburn, MA).

2.3.7. Statistical analysis

All values reported are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The differences observed between control and experimental groups were calculated by two-tailed t-test and considered significant when the P value was <.05.

3. Results

3.1. Interaction of opiates with P-glycoprotein

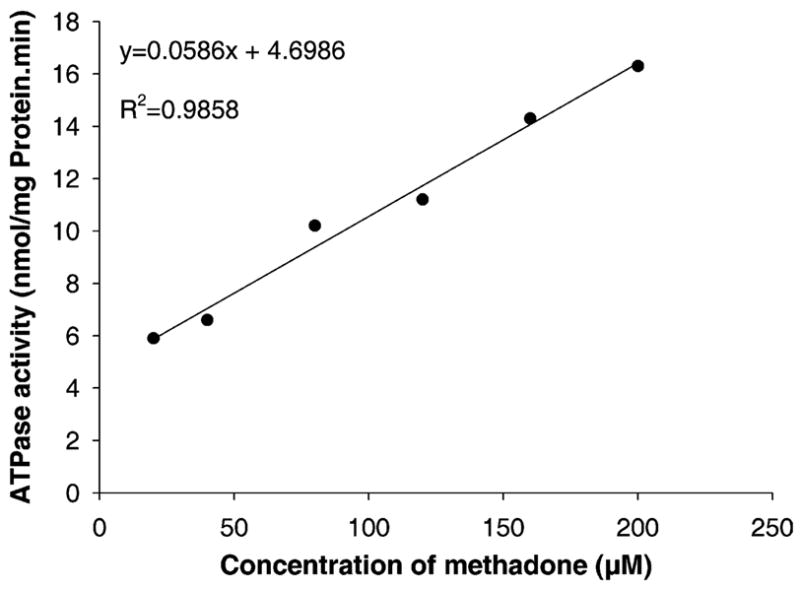

The interaction of the opiates methadone, its derivative LAAM, BUP, and morphine was determined using a commercially available P-gp expressed in insect cell membranes. The membranes were prepared from a baclovirus expression system of human P-gp cDNA (Gentest Corp, Woburn, MA). The stimulation of the ATPase activity coupled to the transporter by each opiate (20 μM) was used as a screening tool to identify P-gp substrates [24]. Once methadone was identified as a substrate of P-gp, dependence of ATPase activity on its concentration was also determined. The vanadate-sensitive ATPase activity of the opiates is shown in Table 1. All opiates, at their tested concentrations, stimulated the P-gp coupled ATPase activity. In addition, the relationship between the ranges of methadone concentration (20–200 μM) and the ATPase activity was linear (Fig. 1). LAAM caused the highest stimulation of ATPase activity followed by methadone, BUP, and morphine. These data suggest that the opiates interact with the efflux transporter P-gp though the activation of ATP hydrolysis was only 30% of that caused by an equimolar (20 μM) concentration of verapamil. However, the methadone concentration of 200 μM caused approximately the same amount of ATP hydrolysis by 20 μM verapamil.

Table 1.

Effect of BUP, LAAM, methadone and morphine on the activity of the vanadate-sensitive ATPase coupled to P-gp

| Compound | ATPase activity (nmol mg−1 min−1) | ATPase activity (nmol mg−1 min−1) reported by Schwab et al. [37] |

|---|---|---|

| Verapamil | 20 | 21 |

| Morphine | 4.3 | 3.7 |

| Methadone | 5.9 | Not determined |

| LAAM | 7.1 | Not determined |

| BUP | 4.8 | Not determined |

BUP: buprenorphine; LAAM: levo-α-acetylmethadol; P-gp: P-glycoprotein.

Fig. 1.

The effect of methadone (20–200 μM) on the activity of the vanadate-sensitive ATPase coupled to P-gp and expressed in a membrane preparation. The ATPase activity increased in a linear fashion with the concentration of methadone.

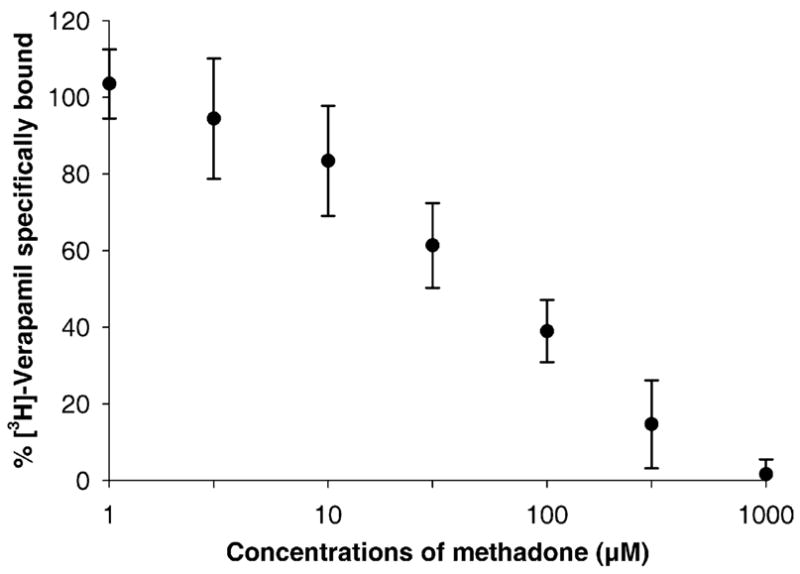

3.2. Methadone displaces verapamil binding to P-glycoprotein

Methadone displaced the specific binding of [3H]-verapamil to P-gp of brush–border membrane preparations. The displacement curve obtained from a plot of specifically bound verapamil versus the concentration of [DL]-methadone revealed an IC50 of approximately 80 μM (Fig. 2). The total displacement of verapamil by 1 mM methadone suggests that the two drugs compete for the same binding site of P-gp.

Fig. 2.

The amount of [3H]-verapamil (5 nM) specifically bound to the transporter site of P-gp decreased with the increase in methadone concentration. The IC50 for methadone displacement of verapamil binding was approximately 80 μM. The nonspecific binding of verapamil was determined in presence of Rhodamine123 (1 mM).

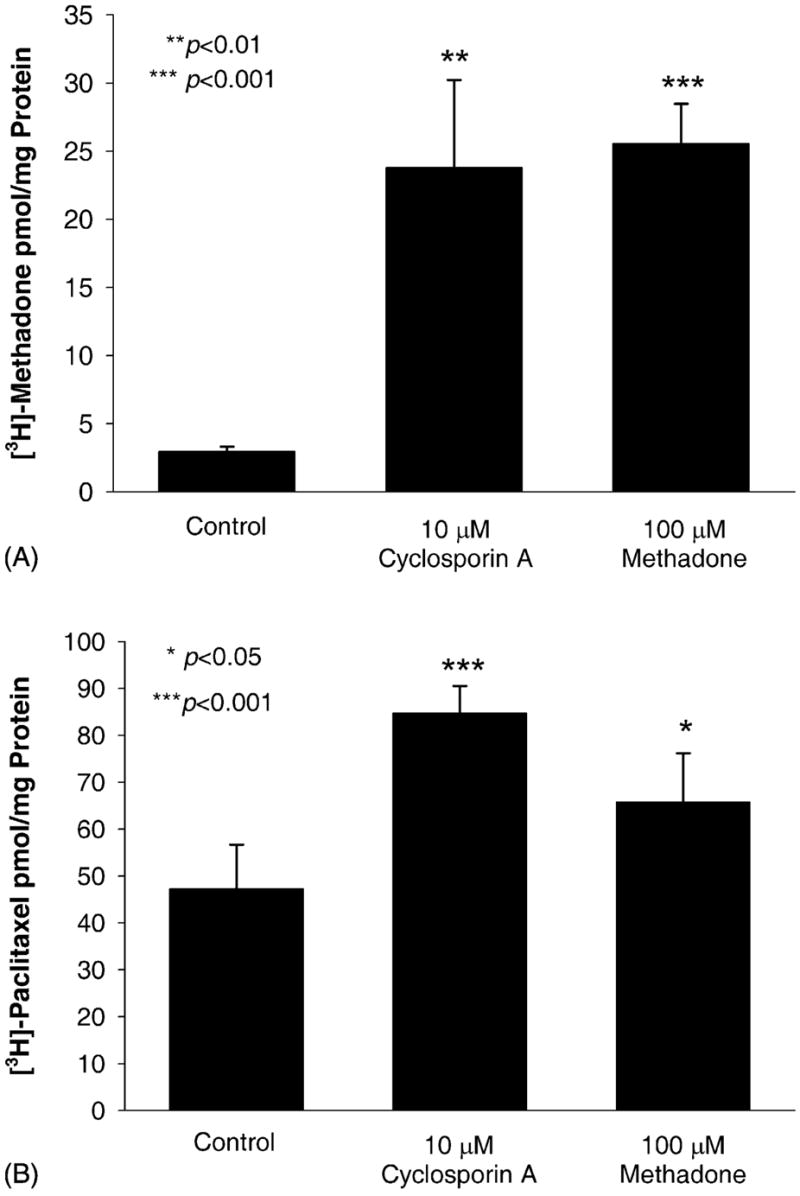

3.3. Interaction of methadone with P-glycoprotein of Be–Wo cells

The human trophoblast-like cell line, Be–Wo, was used to assess the interaction of methadone with P-glycoprotein. Be–Wo cells express functional P-gp at levels greater than primary cultures of normal human cytotrophoblasts [25]. The uptake of methadone by Be–Wo cells was less than 5 pmol/mg protein (Fig. 3). The typical P-gp substrate and inhibitor, cyclosporin A, increased labeled methadone uptake 10-fold as did the presence of a high concentration of unlabeled methadone. Uptake of the typical P-gp substrate paclitaxel was significantly increased in the presence of either cyclosporin A or methadone (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that methadone is a substrate of P-gp in Be–Wo cells.

Fig. 3.

Uptake of (A) 20 nM [3H]-methadone and (B) 50 nM [3H]-paclitaxel by the human trophoblast-like cell line Be–Wo. Cyclosporin A, a typical inhibitor of P-gp, significantly enhances the uptake of methadone and the uptake of the P-gp substrate, paclitaxel, by Be–Wo cells. Methadone significantly enhances the uptake of paclitaxel by Be–Wo cells.

3.4. Effect of P-gp inhibitor GF120918 on transplacental transfer of paclitaxel

Paclitaxel is a substrate of the efflux transporter P-gp, and its concentration in mice brain was increased in presence of the inhibitor GF120918 in a manner similar to that observed for the P-gp knockout mice [15]. To determine the effect of the P-gp inhibitor GF120918 on the transplacental transfer of paclitaxel, the technique of dual perfusion of the placental lobule was utilized in its open–open configuration. Paclitaxel, at its final concentration of 100 nM (85 ng/mL), and its tritiated isotope were added to the maternal circuit and co-transfused with the inert, readily diffusible marker compound antipyrine (a non-P-gp substrate) [26] under steady state conditions for a period of 2 h (for the control group of term placentas). In the experimental group of term placentas, the P-gp inhibitor GF120918 was added first to the maternal reservoir at its final concentration of 1.0 μM (600 ng/mL), transfused for 30 min, and then paclitaxel and antipyrine were added. Transfusion of the three compounds continued for an additional 2 h under conditions identical to those used for the control placentas. Table 2 shows the transfer parameters for paclitaxel across the perfused human placental lobule in the absence (six control placentas) or presence (six experimental placentas) of the P-gp inhibitor GF120918. The data indicate that there is no difference in the transfer rate and clearance of AP between the control and experimental placentas and that the drug is not affected by the presence of the P-gp inhibitor GF120918. Conversely, the transfer of paclitaxel from the maternal to the fetal circuit in the presence of the inhibitor (experimental placentas) was approximately two-fold of that in the absence of the inhibitor (control placentas, P <.05). These data indicate that the inhibition of P-gp efflux activity results in a significant increase in the transfer of paclitaxel to the fetal circuit.

Table 2.

Kinetics parameters for paclitaxel transfer across term human placental lobule in presence and absence of the P-gp inhibitor GF120918

| Parameters | In absence of P-gp inhibitor

|

In presence of P-gp inhibitor

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP | Paclitaxel | AP | Paclitaxel | |

| Trf (%) | 35.6 ± 8.5 | 3.97 ± 1.76 | 34.6 ± 10.7 | 6.56 ± 2.30a |

| Clearance (mL/min) | 1.05 ± 0.27 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 1.02 ± 0.33 | 0.19 ± 0.06a |

| Cl index | – | 0.11 ± 0.02 | – | 0.19 ± 0.07b |

P-gp: P-glycoprotein; AP: antipyrine; Trf: fetal transfer rate; Cl: clearance. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation of six placental perfusions.

P <.05.

P <.01.

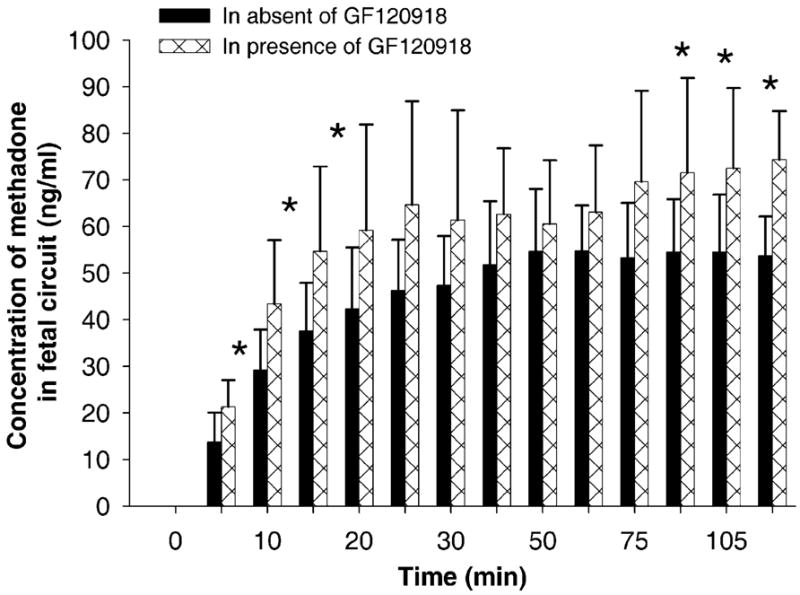

3.5. Effect of P-gp inhibitor GF120918 on transplacental transfer of methadone

Experimental conditions identical to those described above for paclitaxel were used to determine whether the inhibition of the efflux activity of P-gp would increase the transfer of methadone to the fetal circuit. The P-gp inhibitor was added to the maternal reservoir and transfused for 30 min followed by the addition of methadone at its final concentration of 0.58 μM (200 ng/mL) together with its tritiated isomer (experimental placentas), and the transfusion continued for 2 h. Methadone was transfused alone (without the inhibitor) in control placentas under identical conditions. Data obtained from the experimental placentas were normalized to those for the transfer of AP in the control experiments. The mean for the transfer parameters of eight control and eight experimental placentas are presented in Table 3. The data indicate a 30% increase in the concentration of methadone in the fetal circuit in the experimental placentas (in the presence of GF120918) over control (no inhibitor, Fig. 4). In addition, the presence of the inhibitor resulted in a significantly higher (P <.05, Table 3) fetal transfer rate, clearance, and clearance index of methadone (P <.05). These data suggest that the inhibition of P-gp function as an efflux transporter results in an increase in the transfer rates of methadone and paclitaxel by 30 and 50%, respectively, suggesting that the chemotherapeutic agent is a “better” substrate of P-gp or that the passive permeability of methadone is greater than that of paclitaxel.

Table 3.

Kinetics parameters for methadone transfer across term human placental lobule in presence and absence of the P-gp inhibitor GF120918

| Parameters | In absence of P-gp inhibitor

|

In presence of P-gp inhibitor

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP | Methadone | AP | Methadone | |

| Trf (%) | 32.2 ± 6.09 | 26.8 ± 4.45 | 31.8 ± 5.83 | 33.7 ± 6.83a |

| Clearance (mL/min) | 0.96 ± 0.21 | 0.79 ± 0.14 | 0.90 ± 0.15 | 0.96 ± 0.18a |

| Cl index | – | 0.84 ± 0.09 | – | 1.06 ± 0.16b |

P-gp: P-glycoprotein; AP: antipyrine; Trf: fetal transfer rate; Cl: clearance. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation of eight placental perfusions.

P <.05.

P <.01.

Fig. 4.

A histogram representing the concentration of methadone in the fetal circuit of the dually perfused placental lobule. Each time point indicates the concentration of methadone in the absence (control group) and presence (experimental group) of the P-gp inhibitor GF120918. The presence of the inhibitor in the maternal circuit resulted in a significant increase in the concentration of methadone in the fetal circuit.

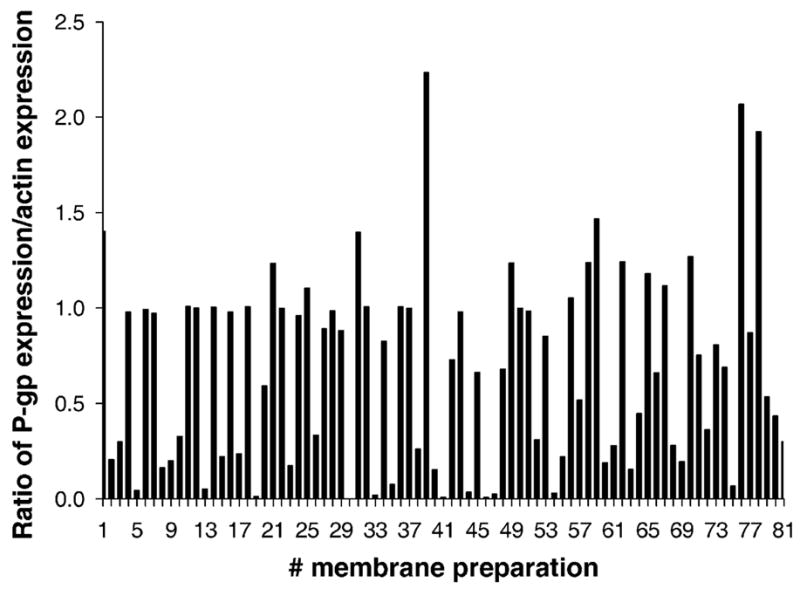

3.6. Expression of P-gp in term human placentas

Western blots were used to determine the level of P-gp expressed in brush–border membrane preparations obtained from 81 term human placentas. The ratio of the amounts of P-gp present in 10 μg brush–border membrane protein of each placenta to that of actin is illustrated in Fig. 5. The data indicated that there is an apparent variation in the amounts of P-gp expressed between placentas. It is unclear whether the expression of P-gp correlates directly with its activity in the efflux of its substrates paclitaxel or methadone.

Fig. 5.

The expression of P-gp in apical membranes prepared from 81 term human placentas as revealed by Western blots. The bar graphs represent the ratio of P-gp expression to that of β-actin in each preparation. The data indicate a wide range for P-gp expression between placentas.

4. Discussion

The goal of this study was to provide evidence for the role of P-gp in the efflux of methadone from term human placental trophoblast tissue. Our working hypothesis was that human placenta might act as a functional barrier protecting the fetus from the effects of xenobiotics, toxins and therapeutic drugs. If true, the concentration of methadone, or any other drug/opiate agonist, in the fetal circulation of a patient under treatment should be affected by specific placental functions. These placental functions would be directed towards limiting or decreasing the transfer of the opiate to the fetal circulation. Accordingly, placental disposition of methadone would be achieved by its metabolism of the drug or its efflux back to the maternal circulation. Earlier reports from our laboratory provided evidence supporting our working hypothesis by identifying aromatase/CYP 19 as the major enzyme responsible for the metabolism of the opiates BUP to norBUP [27], LAAM to norLAAM [28], and methadone to EDDP [5]. It is interesting to note that the major enzyme responsible for the metabolism of these opiates in human liver and intestine is CYP 3A4 [29–31]. In addition, a recent investigation, utilizing the dually perfused placental lobule, revealed that the transfer rates of methadone were higher in the fetal to maternal direction than vice versa [6]. The higher transfer rates of methadone in the fetal to maternal direction could be explained by the activity of the unidirectional transporter P-gp. The explanation, though speculative, was based on the localization of P-gp on the brush–border membranes of human trophoblast cells and its activity as an ATP-dependent unidirectional efflux transporter [9,32]. Indeed, the activity of P-gp in the unidirectional efflux of digoxin, vinblastine, and vincristine has been reported in Be–Wo human placental choriocarcinoma epithelial cells [11]. In addition, P-gp has a broad substrate specificity similar to that of CYP 3A4 [33]; lipophilic drugs that are metabolized by CYP 3A4 in the liver and intestine are usually good candidates for being transferred by the glycoprotein.

Several investigators reported on the interactions of methadone with P-gp utilizing various model systems. In one report, colon adenocarcinoma cell line Caco-2 monolayers in a transwell model system was used for investigating intestinal drug transport, and methadone transfer was not affected by the P-gp inhibitor verapamil [12]. In an in vivo investigation utilizing knockout mice for MDR1 gene revealed higher concentrations of methadone in the brain of these animals [34] and increased analgesia [35]. In another model system, addition of verapamil to the everted rat intestine increased the transfer of methadone by 60% [36]. Accordingly, it was reasonable to assume that the unidirectional activity of P-gp could contribute to the role of the placenta as a functional barrier between maternal and fetal blood and consequently protecting the developing fetus from environmental toxins, xenobiotics, and drugs such as methadone.

In this report, direct and indirect evidence was provided and demonstrated that P-gp regulates the transfer of methadone across term human placenta. A human cDNA-P-gp expressed in a commercially available membrane preparation was utilized to determine whether methadone, and other opiates, would stimulate the ATPase activity coupled to the binding of a ligand to the efflux transporter. An earlier investigation, utilizing the same method, determined that the morphine-stimulated ATPase activity was 3.7 nmol mg−1 min−1 [37], in agreement with our data (Table 1). The rates for P-gp-coupled ATP hydrolysis stimulated by the interaction of methadone, LAAM, and BUP are shown in Table 1. The highest rates for ATPase activity were in the presence of methadone and its derivative LAAM. In addition, the stimulation of ATPase-coupled activity to P-gp increased linearly with the concentration of methadone (Fig. 1). These data provide evidence for the interaction between each of these opiates and the efflux transporter P-gp.

To characterize the site of interaction of methadone with P-gp, a radio-ligand binding assay was utilized to determine whether verapamil binding to P-gp can be displaced by methadone. Two or more P-gp transporter sites have been identified [38]. Verapamil, a substrate of one of the P-gp transporter sites [19] was used to determine whether methadone is a ligand of the same binding site, while progesterone binds to an allosteric modulatory site and is not transported [39]. Our data indicate that [3H]-verapamil specifically bound to P-gp was totally displaced by methadone and the concentration–response curve constructed revealed an IC50 of approximately 80 μM. However, these data, while confirming that methadone binds to the verapamil drug transporter site of P-gp, are not sufficient to determine whether the opiate is actually transported by P-gp.

The technique of dual perfusion of a placental lobule was utilized to determine the activity of P-gp in extruding methadone from placental tissue back to the maternal circuit. This “model” system offers close simulation of in vivo conditions [40]. The kinetics for methadone transfer from the maternal to the fetal circuit was determined utilizing the dually perfused placental lobule in the presence and absence of the P-gp inhibitor GF120918. This acridonecar-boxamide is considered the most potent and available P-gp inhibitor [41]. In addition, we determined the transfer kinetics for the chemotherapeutic drug paclitaxel that is a known substrate of P-gp, in the presence and absence of the inhibitor, for comparison with methadone. The fetal transfer rate of paclitaxel in absence of the inhibitor was approximately 50% of that in its presence (Table 2). Conversely, the fetal transfer rate of methadone in the presence of the inhibitor was 30% higher than in its absence (Table 3). Other kinetic parameters, determined for methadone and paclitaxel (Tables 2 and 3) in the presence and absence of the P-gp inhibitor, reflect similar changes. Therefore, the data indicate that both methadone and paclitaxel are extruded by P-gp from the placental tissue to the maternal circuit. The observed difference in the rates of their extrusion may be explained by one of the following: The chemotherapeutic agent is a “better” substrate of P-gp than the opiate; or, methadone has a higher passive permeability than paclitaxel and consequently inhibition of P-gp would be less pronounced though the opiate might be as “good” a substrate. Indeed, the relative permeability of methadone (Table 3) across placenta is significantly higher than for paclitaxel (Table 2) rendering the second explanation more plausible. Accordingly, if the in vivo activity of P-gp is similar to that determined in vitro, then the concentration of methadone in the fetal circulation should be also affected. Indeed, the administration of the P-gp inhibitor quinidine to healthy volunteers resulted in an increase in their plasma levels of methadone [42].

It should be noted here that the observed increase in the transfer of methadone and paclitaxel to the fetal circuit in presence of the inhibitor GF120918 could be a result of the simultaneous inhibition of at least two efflux transporter proteins; namely, P-gp and Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP). Recent data indicate that GF120918 may also inhibit the activity of BCRP [14], which is highly expressed in the human placenta [43,44]. Therefore, the involvement of BCRP in the efflux of methadone from placental tissue could not be ruled out and should be investigated.

The human trophoblast-like cell line Be–Wo expresses functional P-gp at levels greater than the primary cultures of normal human cytotrophoblasts [25] and was utilized to investigate the interaction of the efflux transporter with methadone and paclitaxel. The uptake of [3H]-methadone by the cells was less than 5 pmol/mg protein and was increased 10-fold in presence of the P-gp inhibitor cyclosporine A (Fig. 3A) or the addition of 0.1 mM of the nonradioactive methadone isotope thus confirming the mediated transfer of the opiate (Fig. 3A). The uptake of paclitaxel by Be–Wo cells was also increased in the presence of either methadone or cyclosporine A (Fig. 3B).

Taken together, the data cited in this report provide evidence that methadone is extruded by the efflux transporter P-gp expressed in term human placentas and the Be–Wo cell line. In view of the reported range of CYP 19 activites in its metabolism of methadone to EDDP [21] by different placentas, the expression of P-gp was determined in 81 brush–border membrane preparations obtained from term placentas of healthy uncomplicated pregnancies. A similar variability in Be–Wo cell line has not been reported and deemed unlikely to occur in a cell line. The ratio of P-gp expression to that of actin in each placental preparation ranged from <0.05 to 2.3 (Fig. 5). To the best of our knowledge, the relation between P-gp expression and its activity in human placentas has not been determined. On the other hand, and irrespective of the expression–activity relationship of placental P-gp, the interplacental variation in the activity of CYP 19 in its metabolism of methadone could be either augmented or decreased in each individual depending on the extent of the activity of the transporter in the efflux of the opiate. Accordingly, the concentration of methadone in the fetal circulation may not correlate with maternal serum drug level of women under treatment. Over the last 30 years, several researchers have reported clinical observations on the presence or absence of a correlation between the dose of methadone administered to the mother and the incidence or intensity of neonatal abstinence syndrome [1–4].

In summary, our data indicate that methadone is a substrate of human placental P-gp. The activity of P-gp in returning methadone to the maternal circulation, together with the activity of CYP 19 in metabolizing methadone to EDDP, represent two functions of the placenta in its disposition of the opiate, which results in a decrease in its concentration in the fetal circulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support of the National Institute on Drug Abuse supply program for providing the opiates and GlaxoSmithKline (Philadelphia, PA) for their generous gift of P-gp inhibitor GF120918. We also appreciate the assistance of the medical staff, the Chairman’s Research Group, and the Publication, Grant, and Media Support Office of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX. This investigation was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to M.S.A. (DA-13431-05) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to K.A. (HD39878-03).

Footnotes

Citation of meeting abstracts where the work was previously presented: Nanovskya TN, Nekhayeva IA, Hankins GDV, Ahmed MS. Effect of P-glycoprotein inhibitor GF120918 on transplacental transfer of methadone. Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine, 24th Annual Meeting, Riverside Hilton, New Orleans, February 2004.

References

- 1.Rosen TS, Pippenger CE. Disposition of methadone and its relationship to severity of withdrawal in the newborn. Addict Dis. 1975;2:169–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kandall SR, Albin S, Gartner LM, Lee K, Eidelman A, Lowinson J. The narcotic-dependent mother: fetal and neonatal consequences. Early Hum Dev. 1977;1:159–69. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(77)90017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berghella V, Lim PJ, Hill MK, Cherpes J, Chennat J, Kaltenbach K. Maternal methadone dose and neonatal withdrawal. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:312–7. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00520-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finnegan LP. Are we there yet?. In: Dewey WL, editor. NIDA Research monograph 184: problems of drug dependence; Proceedings of the 65th Annual Scientific Meeting; Washington, DC: The College on Problems of Drug Dependence (CPDD), Inc., US Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. pp. 55–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nanovskaya TN, Deshmukh SV, Nekhayeva IA, Zharikova OL, Hankins GDV, Ahmed MS. Methadone metabolism by human placenta. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:583–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nekhayeva IA, Nanovskaya TN, Desmukh SV, Zharikova OL, Hankins GDV, Ahmed MS. Bidirectional transfer of methadone across human placenta. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:187–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sparreboom A, van Asperen J, Mayer U, Schinkel AH, Smit JW, Meijer DKF, et al. Limited oral bioavailability and active epithelial excretion of paclitaxel (Taxol) caused by P-glycoprotein in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2031–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugawara I, Kataoka L, Morishita Y, Hamada H, Tsuruo T, Itoyama S, et al. Tissue distribution of P-glycoprotein encoded by a multidrug-resistant gene as revealed by a monoclonal antibody MRP16. Cancer Res. 1988;48:1926–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura Y, Ikelda S, Fukuwara T, Sumizawa T, Tani A, Akiyama S, et al. Function of P-glycoprotein expressed in placenta and mole. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;235:849–53. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callaghan R, Riordan JR. Synthetic and natural opiates interact with P-glycoprotein in multidrug-resistant cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16059–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ushigome F, Takanaga H, Matsuo H, Yanai S, Tsukimori K, Nakano H, et al. Human placental transport of vinblastine, vincristine, digoxin and progesterone: contribution of P-glycoprotein. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;408:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00743-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stormer E, Perloff MD, von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ. Methadone inhibits rhodamine transport in Caco-2 cells. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:954–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouden D, van den Heuvel M, Schoester M, van Rens G, Sonneveld P. In vitro effect of GF120918, a novel reversal agent of multidrug resistance, on acute leukemia and multiple myeloma cells. Leukemia. 1996;10:1930–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Bruin M, Miyake K, Litman T, Robey R, Bates S. Reversal of resistance by GF120918 in cell line expressing the ABC half-transporter MXR. Cancer Lett. 1999;146:117–26. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemper EM, van Zandbergen AE, Cleypool C, Mos HA, Boogerd W, Beijnen JH, et al. Increased penetration of paclitaxel into the brain by inhibition of P-glycoprotein. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2849–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith CH, Nelson DM, King BF, Donohue TM, Ruzycki SM, Kelly LK. Characterization of a microvillous membrane preparation from human placental syncytioitrophoblast: a morfhologic, biochemical and physiologic study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977;128:190–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(77)90686-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Booth AG, Olayele O, Oluwaseyi AV. An improved method for the preparation of human placental syncytiotrophoblast microvilli. Placenta. 1980;1:327–36. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(80)80034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarkadi B, Price EM, Boucher RC, Germann UA, Scarborough GA. Expression of the human multidrug resistance cDNA in insect cells generates a high activity drug-stimulated membrane ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4854–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doppenschmitt S, Langguth P, Regardh CG, Andersson TB, Hilgendorf C, Spahn-Langguth H. Characterization of binding properties to human P-glycoprotein: development of a 3H-verapamil radioligand-binding assay. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:348–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller RK, Wier PJ, Zavislan J, Maulik D, Perez-D’Gregorio R, di Sant’Agnese PA, et al. Human dual placental perfusions: criteria for toxicity evaluations. In: Heindel JJ, Chapin RE, editors. Methods in toxicology. New York: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 205–45. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanovskaya T, Deshmukh S, Brooks M, Ahmed MS. Transplacental transfer and metabolism of buprenorphine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:26–33. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Traunecker HCL, Stevens MCG, Kerr DJ, Ferry DR. The acridone-carboxamide GF120918 potently reverses P-glycoprotein-mediated resistance in human sarcoma MES-Dx5 cells. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:942–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young AM, Fukuhara A, Audus KL. BeWo cells: an in vitro system representing the blood–placental barrier. In: Lear CM, editor. Cell culture models of biological barriers. United Kingdom: Harwood Academic Publishers; 2002. pp. 337–49. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polli JW, Wring SA, Humphreys JE, Huang L, Morgan JB, Webster LO, et al. Rational use of in vitro P-glycoprotein assays in drug discovery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:620–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Utoguchi N, Chandorkar GA, Avery M, Audus K. Functional expression of P-glycoprotein in primary cultures of human cytotrophoblasts and BeWo cells. Reprod Toxicol. 2000;14:217–24. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(00)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho CW, Liu Y, Cobb WN, Henthorn TK, Lillehei K, Christians U, et al. Ultrasound-induced mild hyperthermia as a novel approach to increase drug uptake in brain microvessel endothelial cells. Pharmacol Res. 2002;19:1123–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1019837923906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deshmukh SV, Nanovskaya TN, Ahmed MS. Aromatase is the major enzyme metabolizing buprenorphine in human placenta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:1099–105. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deshmukh SV, Nanovskaya TN, Hankins GD, Ahmed MS. N-Demethylation of levo-alpha-acetylmethadol by human placental aromatase. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:885–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi K, Yamamoto T, Chiba K, Tani M, Shimada N, Ishizaki T, et al. Human buprenorphine N-dealkylation is catalyzed by cytochrome P450 3A4. Drug Metab Dispos. 1998;26:812–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moody DE, Alburges ME, Parker RJ, Collins JM, Strong JM. The involvement of cytochrome P450 3A4 in the demethylation of L-α-acetylmethadol (LAAM), norLAAM, and methadone. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:1347–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oda Y, Kharasch ED. Metabolism of methadone and levo-α-acetyl-methadol (LAAM) by human intestinal cytochrome P450 (CYP3A4): potential contribution of intestinal metabolism to presystemic clearance and bioactivation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:1021–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.St-Pierre MV, Serrano MA, Macias RIR, Dubs U, Hoechli M, Lauper U, et al. Expression of members of the multidrug resistance protein family in human term placenta. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:1495–505. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.4.R1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuetz EG, Beck WT, Schuetz JD. Modulators and substrates of P-glycoprotein and cytochrome P4503A coordinately up-regulate these proteins in human colon carcinoma cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:311–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang JS, Ruan Y, Taylor RM, Donovan JL, Markowitz JS, deVane CL. Brain penetration of methadone (R)- and (S)-enantiomers is greatly increased by P-glycoprotein deficiency in the blood–brain barrier of Abc1a gene knockout mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;173:132–8. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1718-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson SJ, Koszdin K, Bernards CM. Opitate-induced analgesia is increased and prolonged in mice lacking P-glycoprotein. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1392–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200005000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bouer R, Barthe L, Philibert C, Tournaire C, Woodely J, Jouin G. The roles of P-glycoprotein and intracellular metabolism in the intestinal absorption of methadone: in vitro studies using the rat everted intestinal sac. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1999;13:494–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1999.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwab D, Fischer H, Tabatabaei A, Poli S, Huwyler J. Comparison of in vitro P-glycoprotein screening assays: recommendations for their use in drug discovery. J Med Chem. 2003;46:1716–25. doi: 10.1021/jm021012t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shapiro AB, Fox K, Lam P, Ling V. Stimulation of P-glycoprotein-mediated drug transport by prazosin and progesterone. Evidence for a third drug-binding site. Eur J Biochem. 1999;259:841–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garrigos M, Mir LM, Orlowski S. Competitive, and non-competitive inhibition of the multidrug-resistance-associated P-glycoprotein ATPase. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:664–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schneider H. Techniques: in vitro perfusion of human placenta. In: Sastry BVR, editor. Placenta toxicology. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1995. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferry DR, Traunecker H, Kerr DJ. Clinical trials of P glycoprotein reversal in solid tumors. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1070–81. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kharasch ED, Hoffer C, Whittington D, Sheffels P. Role of P-glycoprotein in the intestinal absorption and clinical effects of morphine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:543–54. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maliepaard M, Scheffer GL, Faneyte IF, van Gastelen MA, Pijnenborg AC, Schinkel AH, et al. Subcellular localization and distribution of the breast cancer resistance protein transporter in normal human tissues. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3458–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doyle LA, Ross DD. Multidrug resistance mediated by the breast cancer resistance protein BCRP (ABCG2) Oncogene. 2003;47:7340–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]