Abstract

BACKGROUND

The abrogation of function of the tumor-suppressor protein p53 as a result of mutation of its gene, TP53, is one of the most common genetic alterations in cancer cells. We evaluated TP53 mutations and survival in patients with squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck.

METHODS

A total of 560 patients with squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck who were treated surgically with curative intent were enrolled in our prospective multicenter, 7-year study. TP53 mutations were analyzed in DNA from the tumor specimens with the use of the Affymetrix p53 chip and the Surveyor DNA endonuclease and denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. Mutations were classified into two groups, disruptive and nondisruptive, according to the degree of disturbance of protein structure predicted from the crystal structure of the p53–DNA complexes. TP53 mutational status was compared with clinical outcome.

RESULTS

TP53 mutations were found in tumors from 224 of 420 patients (53.3%). As compared with wild-type TP53, the presence of any TP53 mutation was associated with decreased overall survival (hazard ratio for death, 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1 to 1.8; P = 0.009), with an even stronger association with disruptive mutations (hazard ratio, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.3 to 2.4; P<0.001) and no significant association with nondisruptive mutations (hazard ratio, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9 to 1.7; P = 0.16). In multivariate analyses a disruptive TP53 alteration, as compared with the absence of a TP53 mutation, had an independent, significant association with decreased survival (hazard ratio, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2 to 2.4; P = 0.003).

CONCLUSIONS

Disruptive TP53 mutations in tumor DNA are associated with reduced survival after surgical treatment of squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck.

Squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck is one of the most common cancers worldwide. More than 45,000 new cases are expected in the United States in 2007.1 The disease is multifactorial in its pathogenesis and is associated with the use of tobacco2,3 and alcohol4,5 and infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV).6,7 The abrogation of p53 function — through the mutation of its gene, TP538; the loss of heterozygosity of TP539; or interaction with viral proteins10 — is one of the most common molecular alterations in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck.11–13 The involvement of p53 in apoptosis14 and cell-cycle control15 makes it a plausible biomarker of prognosis. In addition, the spectrum of p53 mutations observed among tumor samples suggests that the mutations vary in their prognostic power. In addition, no molecular markers of prognosis are currently well established.16,17

The role of p53 as a prognostic marker of squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck is controversial. The small numbers of patients studied, insufficient clinical follow-up, and variable laboratory techniques have made the interpretation of published results difficult.18,19 Methods for identifying p53 alterations have included immunohistochemical analysis, mutation screening, and functional tests involving yeast. The measurement of p53 expression by immunohistochemical means yields inconsistent conclusions, probably because of the variable definition of “overexpression.”20,21 In addition, immunohistochemical techniques fail to detect frame-shift, splice-site, and null mutations and cannot determine clinical associations of specific mutations. Sensitive and rapid mutation analysis,22 in contrast, allows for the determination of the base change and its position within the gene. Crystal structural analyses of the effect of TP53 mutations on DNA binding support the possibility of a variable effect of mutations on tumor behavior.23 Studies of various types of tumors24–26 suggest that the heterogeneity of TP53 mutants leads to similarly heterogeneous clinical outcomes.

Our study, involving the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) and the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) (study no. ECOG E4393/RTOG 9614), has as its first objective to determine the clinical utility of molecular detection of cancer cells in tumor margins; research toward this objective is ongoing. An independent, second objective of the protocol is to determine the incidence of TP53 mutation in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck and to seek associations between TP53 status and survival. We report the results of the second objective in this article.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

Between 1996 and 2002, 560 patients with squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck were enrolled in our prospective, multicenter study involving 18 member institutions of ECOG and RTOG. The protocol was approved by ECOG, RTOG, and the investigational review board of each participating institution. All patients provided written informed consent. Patients with newly diagnosed or recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck were eligible if the treatment plan included primary surgical extirpation with curative intent. During the operation, tumor and margin samples were collected.

ECOG and RTOG data managers collected demographic and clinical data for each patient from the participating institutions perioperatively and at scheduled intervals during the follow-up period. Pathology reports were submitted to ECOG and RTOG, and the findings were reviewed and tabulated. At 6-month intervals for the first 3 years and annually thereafter, the status of each patient, including information about recurrent or second primary cancer and subsequent treatment, was reported.

TUMOR SPECIMENS

Isolation and Processing of Tumor Specimens and DNA Extraction

Tumor samples were rapidly frozen at −80°C before being shipped to the head and neck tumor laboratory at Johns Hopkins University. (Paraffin-embedded specimens were used, occasionally, when frozen tissue specimens were unavailable.) A series of 5-μm sections were cut from each primary-tumor specimen for hematoxylin and eosin staining to confirm the presence of squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Additional 12-μm sections were cut and kept overnight in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and proteinase K at 48°C; DNA was then collected by means of phenol–chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Only samples with at least 70% tumor cells were candidates for molecular studies. Tissues with less than 70% tumor cells were microdissected to enrich the tumor-cell content of the specimen.

Mutational Analysis

TP53 mutations were screened according to a multistep process with the use of the GeneChip p53 assay and the Surveyor DNA endonuclease (Trans-genomic) and denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC). The GeneChip assay (Affymetrix) was performed as previously described22,27 for high-throughput detection of mutations in exons 2 through 11. DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded tissue was often degraded, resulting in indeterminate results at several nucleotide positions on the p53 gene chip. Surveyor or DHPLC analysis (or both) was used to determine which of the indeterminate sequence variants were genetic alterations and which were artifacts. All mutations detected by means of the GeneChip p53 assay or Surveyor–DHPLC analysis were confirmed with the use of automatic sequencing (ABI BigDye cycle-sequencing kit) or direct dideoxynucleotide sequencing.22

Classification of Mutations

Work published before the end of the study that described structural and functional differences among various TP53 mutations was used to define two categories, based on the location of the mutation23 and the predicted amino acid alterations.28 Disruptive mutations are nonconservative mutations located inside the key DNA-binding domain (L2–L3 region), or stop codons in any region, and nondisruptive mutations are conservative mutations or nonconservative mutations outside the L2–L3 region (excluding stop codons). (See the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at www.nejm.org, for additional details on the method of classification.)

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Laboratory and clinical data were submitted to the ECOG central office. Analysis was performed at the ECOG statistical center. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the baseline characteristics of the patients. Survival curves were estimated according to the Kaplan–Meier method,29 and the differences according to mutation-status category were examined using the log-rank test.30 Survival was defined as the time from study entry to death or to the last follow-up. Progression-free survival was defined as the time from study entry to death or cancer recurrence. The data for patients who were alive without recurrence at the time of the analysis were censored at the last follow-up. Fisher’s exact test,31 Student’s t-test, and Mehta’s exact test for ordered categorical data32 were used to compare patients with and those without mutations at baseline.

Proportional-hazards models33 were used to assess the univariate prognostic significance of tumor variables on overall survival. P values for hazard ratios were calculated with the use of the likelihood-ratio test. Using multivariate Cox proportional-hazards models, we considered TP53 status, tumor site and stage, nodal stage, smoking history, average alcohol use, and type of treatment. Smoking history was included as a continuous variable, whereas all other factors were considered to be categorical variables. Hazard ratios were calculated relative to a reference group. Akaike’s information criterion34 was used to evaluate the relative usefulness of the model. The method developed by Gray35 was used to examine data on death from squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck and death from other causes. P values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

EXCLUSION OF PATIENTS

Of the 560 registered patients, we excluded 16 because they did not meet the eligibility criteria, 88 because no tumor specimen was available (owing to the failure of the physician to provide a specimen or to an insufficient amount of tumor cells in the specimen), and 36 because their specimens could not be analyzed (because the tumor DNA could not be amplified). The remaining 420 patients were eligible and could be evaluated for TP53 mutations in the primary tumor.

The data for patients included in the analyses and for those excluded had similar distributions with regard to ECOG performance status (P = 0.79); primary tumor site (P=0.41); degree of cell differentiation (P = 0.24); presence or absence of treatment with surgery (P=0.25), radiotherapy (P = 0.21), or chemotherapy (P = 0.21); and survival (P = 0.87). However, as compared with patients who were excluded, patients included in the analyses were more likely to have tumors of stage T3 or T4 (30.8% vs. 47.3%, P = 0.001) and were more likely to have clinically enlarged lymph nodes (29.6% vs. 43.0%, P = 0.006).

FOLLOW-UP AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PATIENTS

The follow-up period ranged from 5 days to 10.7 years, with a median of 6.2 years for patients whose data were censored. The median age at diagnosis was 62 years (range, 17 to 98). At study entry, 131 patients were treated with surgery alone, 203 underwent surgery and postoperative radiation or chemoradiation therapy, and 78 underwent salvage surgery (since previous radiation had failed to cure). The primary tumor site was the oral cavity in 180 patients (42.9%), the larynx in 90 (21.4%), the oropharynx in 93 (22.1%), and the hypopharynx in 32 (7.6%). In 22 patients (5.2%), the primary tumor was at another site or at an unknown site on initial staging. Three patients (0.7%) had primary tumors at multiple sites.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. TP53 mutations were found in tumors from 224 patients (53.3%). Neoplastic lesions arising from the hypopharynx had the highest mutation frequency (75.0%), followed by tumors arising from the larynx, oral cavity, and oropharynx (P = 0.03). Given the number of factors examined, however, this P value should be interpreted with caution.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients.*

| Characteristic | All Patients | Patients with Wild-Type TP53 | Patients with Mutant TP53 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | no. (%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 303 | 146 (48.2) | 157 (51.8) | 0.30 |

| Female | 117 | 50 (42.7) | 67 (57.3) | |

| Race or ethnic group† | ||||

| White | 351 | 171 (48.7) | 180 (51.3) | 0.40 |

| Hispanic | 20 | 8 (40.0) | 12 (60.0) | |

| Black | 45 | 16 (35.6) | 29 (64.4) | |

| Asian | 1 | 0 | 1 (100.0) | |

| Other | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Age at study entry | ||||

| <55 yr | 135 | 70 (51.9) | 65 (48.1) | 0.50 |

| 55–64 yr | 115 | 45 (39.1) | 70 (60.9) | |

| >64 yr | 170 | 81 (47.6) | 89 (52.4) | |

| Cell differentiation | ||||

| Well differentiated | 84 | 41 (48.8) | 43 (51.2) | 0.40 |

| Moderately differentiated | 231 | 106 (45.9) | 125 (54.1) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 79 | 35 (44.3) | 44 (55.7) | |

| Undifferentiated | 2 | 0 | 2 (100.0) | |

| Unknown | 24 | 14 (58.3) | 10 (41.7) | |

| Primary tumor site | ||||

| Oral cavity | 180 | 83 (46.1) | 97 (53.9) | 0.03 |

| Oropharynx | 93 | 54 (58.1) | 39 (41.9) | |

| Hypopharynx | 32 | 8 (25.0) | 24 (75.0) | |

| Larynx | 90 | 39 (43.3) | 51 (56.7) | |

| Other | 20 | 9 (45.0) | 11 (55.0) | |

| Multiple | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 2 (100.0) | 0 | |

| Pathological tumor stage | ||||

| T1 | 97 | 50 (51.5) | 47 (48.5) | 0.05 |

| T2 | 150 | 77 (51.3) | 73 (48.7) | |

| T3 | 75 | 33 (44.0) | 42 (56.0) | |

| T4 | 88 | 34 (38.6) | 54 (61.4) | |

| TX or Tis | 10 | 2 (20.0) | 8 (80.0) | |

| Pathological nodal stage | ||||

| N0 or NX | 212 | 103 (48.6) | 109 (51.4) | 0.40 |

| N1–N3 | 208 | 93 (44.7) | 115 (55.3) | |

| Clinical TNM stage | ||||

| I | 61 | 30 (50.0) | 31 (50.8) | 0.24 |

| II | 83 | 40 (48.2) | 43 (51.8) | |

| III | 103 | 52 (50.5) | 51 (49.5) | |

| IV | 170 | 72 (42.4) | 98 (57.6) | |

| Could not be assessed | 3 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Surgery only | 131 | 62 (47.3) | 69 (52.7) | 0.90 |

| Surgery + postoperative therapy | 203 | 89 (43.8) | 114 (56.2) | |

| Salvage surgery | 78 | 39 (50.0) | 39 (50.0) | |

| Unknown | 8 | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Never smoked | 80 | 42 (52.5) | 38 (47.5) | 0.08 |

| Pipe or cigar only | 17 | 9 (52.9) | 8 (47.1) | |

| Cigarettes | ||||

| <20 Pack-yr | 46 | 24 (52.2) | 22 (47.8) | |

| 20–40 Pack-yr | 114 | 49 (43.0) | 65 (57.0) | |

| >40 Pack-yr | 152 | 64 (42.1) | 88 (57.9) | |

| Unknown | 11 | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | |

| Average alcohol use | ||||

| <10 oz/wk | 227 | 112 (49.3) | 115 (50.7) | 0.22 |

| 10–32 oz/wk | 80 | 32 (40.0) | 48 (60.0) | |

| >32 oz/wk | 82 | 36 (43.9) | 46 (56.1) | |

| Unknown | 31 | 16 (51.6) | 15 (48.4) | |

To convert values for alcohol to milliliters, multiply by 29.6. TNM denotes tumor–node–metastasis.

Race or ethnic group was determined on the basis of data in hospital records.

SURVIVAL AND TP53 MUTATIONAL STATUS

As of April 2007, 232 patients had died. The cause of death was head and neck cancer in 121 patients, other causes in 62, and unknown causes in 49. There were 49 reported second primary cancers, 24 among patients who died (8 of disease, 13 of other causes, and 3 of unknown causes). The remaining 25 patients with second primary cancers were alive at the last follow-up. There was no association between the development of a second primary cancer and TP53 mutational status (P=0.98).

The survival of patients was associated with several conventional prognostic factors (Table 2). Patients with positive lymph nodes, tumor stage 3 or 4, primary tumor in the hypopharynx, or study treatment consisting of salvage surgery for recurrence had a significantly increased risk of death. A smoking history of any type or quantity was not a significant factor for survival as compared with no history of smoking. Patients who consumed an average of 10 to 32 oz (296 to 947 ml) of alcohol per week had a higher risk of death than those who consumed less than 10 oz per week (P<0.001), but given the number of factors examined, this association may be due to chance.

Table 2.

Results of Univariate Analysis of Selected Prognostic Factors for Overall Survival.*

| Factor and Level | No. of Patients | No. of Deaths | Median Survival (yr) | Hazard Ratio for Death (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathological nodal stage | |||||

| N0 or NX | 212 | 98 | 5.9 | Reference | |

| N1–N3 | 208 | 134 | 2.1 | 1.98 (1.4–2.4) | <0.001 |

| Pathological tumor stage | |||||

| T1 or T2 | 247 | 125 | 5.7 | Reference | |

| T3 or T4 | 163 | 102 | 3.0 | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 0.004 |

| TX or Tis | 10 | 5 | NR | 1.1 (0.4–2.7) | 0.84 |

| Primary tumor site | |||||

| Oropharynx | 93 | 45 | 5.6 | Reference | |

| Oral cavity | 180 | 96 | 4.0 | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.18 |

| Hypopharynx | 32 | 24 | 1.6 | 2.2 (1.3–3.6) | 0.002 |

| Larynx | 90 | 54 | 3.9 | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 0.21 |

| Other | 22 | 10 | NR | 0.9 (0.4–1.7) | 0.64 |

| Multiple | 3 | 3 | 0.4 | 9.9 (3.0–32.2) | <0.001 |

| Treatment | |||||

| Surgery + postoperative therapy | 203 | 109 | 4.3 | Reference | |

| Surgery only | 131 | 65 | 5.2 | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 0.79 |

| Salvage surgery | 78 | 54 | 3.0 | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | 0.02 |

| Unknown | 8 | 4 | 5.3 | 0.9 (0.3–2.4) | 0.79 |

| Smoking history | |||||

| Never smoked | 80 | 40 | 4.7 | Reference | |

| Pipe or cigar | 17 | 10 | 2.4 | 1.3 (0.6–2.6) | 0.49 |

| Cigarettes | |||||

| <20 Pack-yr | 46 | 21 | NR | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 0.73 |

| 20–40 Pack-yr | 114 | 69 | 3.4 | 1.4 (1.0–2.1) | 0.08 |

| >40 Pack-yr | 152 | 88 | 3.9 | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.24 |

| Unknown | 11 | 4 | NR | 0.7 (0.3–2.1) | 0.56 |

| Average alcohol use | |||||

| <10 oz/wk | 227 | 122 | 5.1 | Reference | |

| 10–32 oz/wk | 80 | 55 | 2.1 | 1.8 (1.3–2.3) | <0.001 |

| >32 oz/wk | 82 | 43 | 3.5 | 1.2 (0.8–1.6) | 0.44 |

| Unknown | 31 | 12 | 8.4 | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.25 |

| TP53 status | |||||

| Wild-type | 196 | 99 | 5.4 | Reference | |

| Mutant | 224 | 133 | 3.2 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.009 |

| Mutation category | |||||

| Wild-type | 196 | 99 | 5.4 | Reference | |

| Nondisruptive | 139 | 76 | 3.9 | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 0.16 |

| Disruptive | 85 | 57 | 2.0 | 1.7 (1.3–2.4) | <0.001 |

The global P values from the log-rank test were as follows: for primary tumor site, P<0.001; for type of treatment, P = 0.04; for smoking history, P = 0.28; and for average alcohol use, P = 0.004. To convert values for alcohol to milliliters, multiply by 29.6.

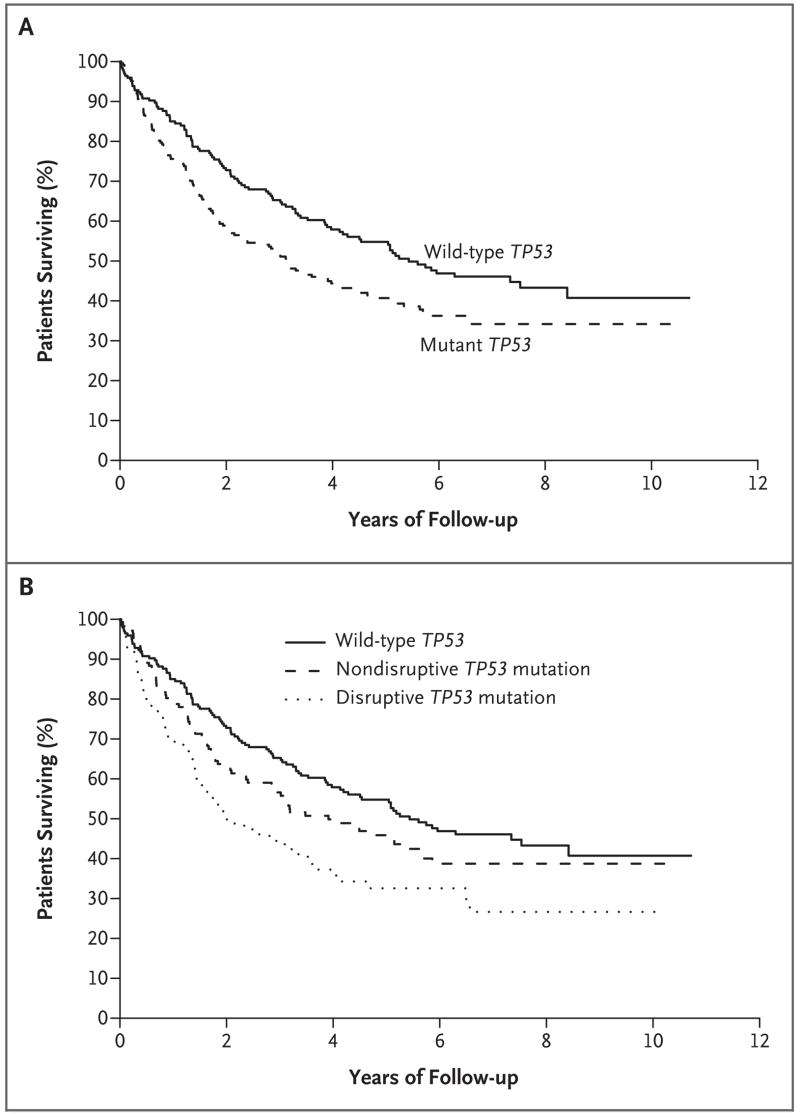

The presence of any TP53 mutation was significantly associated with decreased overall survival (Fig. 1A). Five-year overall survival was reached in 40.7% of patients with TP53 mutations and in 54.8% of patients with wild-type TP53 (P = 0.009). The median survival was 3.2 years among patients with a TP53 mutation and 5.4 years among patients with wild-type tumors (hazard ratio, 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1 to 1.8; P = 0.009).

Figure 1. Overall Survival among Patients, According to Mutation Status and Mutation Category.

Panel A shows Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival among the 196 patients with wild-type TP53 (of whom 99 died) and among the 224 patients with mutant TP53 (of whom 133 died). The median survival among patients with mutant TP53 was 3.2 years, as compared with 5.4 years among patients with wild-type TP53. Panel B shows the Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival among the 139 patients with nondisruptive TP53 mutations (of whom 76 died) and the 85 patients with disruptive TP53 mutations (of whom 57 died). The median survival among patients with disruptive mutations was 2.0 years, whereas that among patients with non-disruptive mutations was 3.9 years. Disruptive mutations were defined as nonconservative mutations located inside the key DNA-binding domain (the L2–L3 region) or stop codons in any region; nondisruptive mutations were defined as conservative or nonconservative mutations (excluding stop codons) outside the L2–L3 region.

As compared with patients with wild-type TP53, the 85 patients with disruptive mutations had significantly lower overall survival (hazard ratio, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.3 to 2.4; P<0.001), but the 139 patients with nondisruptive mutations did not (hazard ratio, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9 to 1.7; P = 0.16) (Table 2 and Fig. 1B).

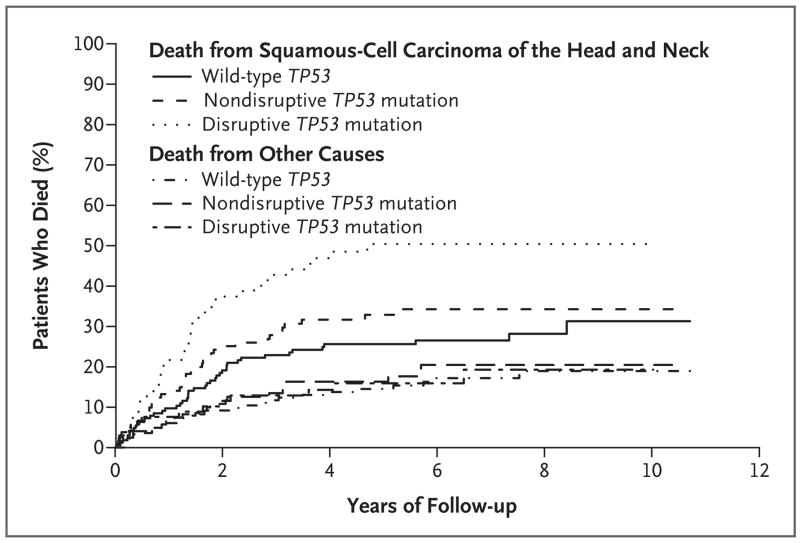

The cumulative incidence of death from squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck or from other causes was higher among patients with mutant TP53 than among those with wild-type TP53 (P = 0.005), with the highest incidence among those with disruptive mutations (Fig. 2). The mutation category was associated with a cumulative risk of death from squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck (P = 0.002) but not with a cumulative risk of death from other causes (P = 0.87).

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Death among Patients with a Known Cause of Death According to Mutation Category.

Of the patients who died from squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck, 44 had wild-type TP53, 39 had a nondisruptive TP53 mutation, and 38 had a disruptive TP53 mutation. Of the patients who died from other causes, 27 had wild-type TP53, 22 had a nondisruptive TP53 mutation, and 13 had a disruptive TP53 mutation. The mutation category was significantly associated with a cumulative risk of death from squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck (P = 0.002 with the use of the Gray test) but not with a cumulative risk of death from other causes (P = 0.87 with the use of the Gray test).

In multivariate analyses involving Cox proportional-hazards models, as compared with the absence of a TP53 mutation, the presence of any TP53 mutation (hazard ratio for death, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.73; P = 0.04), and particularly a disruptive mutation (hazard ratio, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.20 to 2.36; P = 0.003), remained significantly associated with decreased survival after adjustment for pathologic nodal stage, type of treatment, site of primary tumor, smoking history, and average alcohol use (Table 3). The group with wild-type TP53 had longer progression-free survival than did the group with nondisruptive TP53 mutations (P = 0.049) or the group with disruptive TP53 mutations (P<0.001) (Fig. 1 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 3.

Results of Multivariate Analysis of Selected Prognostic Factors for Overall Survival.

| Model and Selected Factor | Hazard Ratio for Death (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Any mutation | ||

| Presence of mutation | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.04 |

| Primary tumor site | ||

| Oral cavity | 1.7 (1.2–2.6) | 0.005 |

| Hypopharynx | 1.8 (1.1–3.1) | 0.02 |

| Larynx | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 0.13 |

| Other | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 0.93 |

| Multiple | 8.3 (2.4–28.0) | <0.001 |

| Pathologic nodal stage N1–N3 | 2.4 (1.8–3.3) | <0.001 |

| Treatment | ||

| Surgery only | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 0.06 |

| Salvage surgery | 2.0 (1.4–2.9) | <0.001 |

| Smoking history | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.07 |

| Average alcohol use* | ||

| 10–32 oz/wk | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 0.11 |

| >32 oz/wk | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.39 |

| Unknown | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) | 0.07 |

| Mutation category | ||

| Nondisruptive TP53 mutation | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 0.43 |

| Disruptive TP53 mutation | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 0.003 |

| Primary tumor site | ||

| Oral cavity | 1.7 (1.2–2.5) | 0.006 |

| Hypopharynx | 1.9 (1.1–3.2) | 0.02 |

| Larynx | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 0.14 |

| Other | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 0.91 |

| Multiple | 9.7 (2.8–33.0) | <0.001 |

| Pathologic nodal stage N1–N3 | 2.4 (1.8–3.3) | <0.001 |

| Treatment | ||

| Surgery only | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 0.05 |

| Salvage surgery | 2.1 (1.4–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Smoking history | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.07 |

| Average alcohol use* | ||

| 10–32 oz/wk | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.13 |

| >32 oz/wk | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.41 |

| Unknown | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) | 0.04 |

To convert values for ounces to milliliters, multiply by 29.6.

DISCUSSION

Our study provides evidence of an association between a TP53 mutation in a patient with squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck and survival after surgical treatment. The results demonstrate that TP53 mutations generally, and disruptive mutations of TP53 particularly, are significantly associated with short survival in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck.

In previous reports, alterations of TP53 were detected in about 40% of cases, depending on the method used and the number of exons examined. We found a frequency of 53% in our cohort, probably because the p53 gene chip and Surveyor–DHPLC analysis can detect mutations in the entire coding region of TP53 (exons 2 through 11), whereas most previous studies analyzed only exons 5 through 8. The distribution of TP53 mutations was consistent across participating institutions in our study.

Of the 420 patients enrolled in our study, 180 (42.9%) had cancer of the oral cavity, whereas 215 (51.2%) had pharyngeal or laryngeal cancers. These data include patients who underwent primary surgery, and the data may not accurately represent the current population of patients with squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck, since rates of HPV-related oropharyngeal disease are increasing. An inverse relationship between the presence of HPV DNA in squamous-cell carcinoma of the oropharynx and the presence of a TP53 mutation has been well documented.36 The relatively low frequency of TP53 mutations in oropharyngeal carcinomas (41.9%) may be due to the contribution of HPV infection, in which TP53 is inactivated by binding to the E6 viral protein rather than by mutation. The importance of HPV in oropharyngeal cancer was not recognized at the time our study was designed, and analysis for HPV was not included in the protocol.

TP53 mutation is associated with a history of tobacco use.37 Most of the patients in our study were smokers, but the association between smoking and TP53 mutation was not significant, perhaps because the data-collection forms did not distinguish between former smokers and non-smokers.

In our study, 124 of the 560 registered patients were excluded because of a lack of tumor-tissue specimens or because the DNA from the specimens was of poor quality. The cancers in these patients were likely to be stage 1 or 2, in which tumor is less abundant than in higher stages. Although these exclusions could introduce bias, since TP53 mutations were seen most frequently in patients with advanced-stage squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck, the association of TP53 status with survival was independent of stage. Our results show that — independently of tumor site, tumor stage, and type of treatment — the disruptive category of mutation accounted for almost all of the association of TP53 mutation with short survival (Fig. 1B).

Several strategies have been used to categorize TP53 mutations, since different alterations have been observed to behave in different ways. Our data support this concept. The functional properties of each mutation may uniquely affect pathways for maintaining genomic integrity that involve p53. The biologic effects of TP53 mutations may also be influenced by the presence or absence of the remaining wild-type allele and by the gain of function of some mutants. In light of the complexity of p53 interactions, it is interesting that our simple categorization based on protein folding and certain features of the gene successfully classified cases into groups that were associated with different outcomes.

Our results indicate that TP53 mutations could be a useful stratification factor in prospective clinical trials. In our cohort, chemotherapy was administered only as an adjuvant measure in combination with postoperative radiation therapy, or before study entry in a few cases. Therefore, we have no data on tumor response to chemotherapy. It would be clinically useful to determine whether TP53 mutations are associated with a response to treatments that attack p53-specific pathways.

Supplementary Material

APPENDIX

In addition to the authors, the following investigators participated in this study: University of Connecticut, Storrs, and Tufts–New England Medical Center, Boston — J. Spiro; Beth Israel Medical Center, New York — D. Frank; Case Western–Metro Health Medical Center, Cleveland — L. Steinberg; Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland — P. Lavertu; H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL — J. Endicott; Montefiore–Einstein Cancer Center, Bronx, NY — J. Beitler; New York University Medical Center, New York — M. Persky; Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston — T. Day; Vanderbilt University, Nashville — D. Johnson; Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC — D. Brown; Wayne State University, Detroit — G. Yoo; Wisconsin Medical College, Milwaukee — B.H. Campbell.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfeifer GP, Denissenko MF, Olivier M, Tretyakova N, Hecht SS, Hainaut P. Tobacco smoke carcinogens, DNA damage and p53 mutations in smoking-associated cancers. Oncogene. 2002;21:7435–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan JA, Boyle JO, Koch WM, et al. Association between cigarette smoking and mutation of the p53 gene in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:712–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503163321104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boffetta P, Mashberg A, Winkelmann R, Garfinkel L. Carcinogenic effect of tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking on anatomic sites of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Int J Cancer. 1992;52:530–3. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewin F, Norell SE, Johansson H, et al. Smoking tobacco, oral snuff, and alcohol in the etiology of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a population-based case-referent study in Sweden. Cancer. 1998;82:1367–75. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980401)82:7<1367::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mork J, Lie AK, Glattre E, et al. Human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1125–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syrjänen S. Human papillomavirus (HPV) in head and neck cancer. J Clin Virol. 2005;32(Suppl 1):S59–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olshan AF, Weissler MC, Pei H, Conway K. p53 Mutations in head and neck cancer: new data and evaluation of mutational spectra. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:499–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.González MV, Pello MF, López-Larrea C, Suárez C, Menéndez MJ, Coto E. Loss of heterozygosity and mutation analysis of the p16 (9p21) and p53 (17p13) genes in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:1043–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheffner M, Werness BA, Huibregtse JM, Levine AJ, Howley PM. The E6 onco-protein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell. 1990;63:1129–36. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–10. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guimaraes DP, Hainaut P. TP53: a key gene in human cancer. Biochimie. 2002;84:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01356-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasco M, Crook T. The p53 network in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:222–31. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(02)00163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haupt S, Berger M, Goldberg Z, Haupt Y. Apoptosis — the p53 network. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4077–85. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giono LE, Manfredi JJ. The p53 tumor suppressor participates in multiple cell cycle checkpoints. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:13–20. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salesiotis AN, Cullen KJ. Molecular markers predictive of response and prognosis in the patient with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: evolution of a model beyond TNM staging. Curr Opin Oncol. 2000;12:229–39. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200005000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradford CR. Predictive factors in head and neck cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;13:777–85. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soussi T, Béroud C. Assessing TP53 status in human tumours to evaluate clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:233–40. doi: 10.1038/35106009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soussi T, Ishioka C, Claustres M, Béroud C. Locus-specific mutation databases: pitfalls and good practice based on the p53 experience. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nrc1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor D, Koch WM, Zahurak M, Shah K, Sidransky D, Westra WH. Immunohistochemical detection of p53 protein accumulation in head and neck cancer: correlation with p53 gene alterations. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1221–5. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sjögren S, Inganäs M, Norberg T, et al. The p53 gene in breast cancer: prognostic value of complementary DNA sequencing versus immunohistochemistry. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:173–82. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.3-4.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahrendt SA, Halachmi S, Chow JT, et al. Rapid p53 sequence analysis in primary lung cancer using an oligonucleotide probe array. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7382–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friend S. p53: A glimpse at the puppet behind the shadow play. Science. 1994;265:334–5. doi: 10.1126/science.8023155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho Y, Gorina S, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor-DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science. 1994;265:346–55. doi: 10.1126/science.8023157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Børresen AL, Andersen TI, Eyfjörd JE, et al. TP53 mutations and breast cancer prognosis: particularly poor survival rates for cases with mutations in the zinc-binding domains. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1995;14:71–5. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870140113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erber R, Conradt C, Homann N, et al. TP53 DNA contact mutations are selectively associated with allelic loss and have a strong clinical impact in head and neck cancer. Oncogene. 1998;16:1671–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wikman FP, Lu ML, Thykjaer T, et al. Evaluation of the performance of a p53 sequencing microarray chip using 140 previously sequenced bladder tumor samples. Clin Chem. 2000;46:1555–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frontiers in bioscience: database: amino acids. [Accessed November 21, 2007]; http://www.bioscience.org/urllists/aminacid.htm.

- 29.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peto R, Peto J. Asymptotically efficient rank invariate test procedures. J R Stat Soc [A] 1972;135:185–206. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cox DR. Analysis of binary data. London: Methuen; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehta CR, Patel NR, Tsiatis AA. Exact significance testing to establish treatment equivalence with ordered categorical data. Biometrics. 1984;40:819–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc [B] 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 1974;19:716–23. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray RJ. A class of k-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–54. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:709–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soussi T, Kato S, Levy PP, Ishioka C. Reassessment of the TP53 mutation database in human disease by data mining with a library of TP53 missense mutations. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:6–17. doi: 10.1002/humu.20114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.