Abstract

Background

The underuse of total joint arthroplasty in appropriate candidates is more than 3 times greater among women than among men. When surveyed, physicians report that the patient's sex has no effect on their decision-making; however, what occurs in clinical practice may be different. The purpose of our study was to determine whether patients' sex affects physicians' decisions to refer a patient for, or to perform, total knee arthroplasty.

Methods

Seventy-one physicians (38 family physicians and 33 orthopedic surgeons) in Ontario performed blinded assessments of 2 standardized patients (1 man and 1 woman) with moderate knee osteoarthritis who differed only by sex. The standardized patients recorded the physicians' final recommendations about total knee arthroplasty. Four surgeons did not consent to the inclusion of their data. After detecting an overall main effect, we tested for an interaction with physician type (family physician v. orthopedic surgeon). We used a binary logistic regression analysis with a generalized estimating equation approach to assess the effect of patients' sex on physicians' recommendations for total knee arthroplasty.

Results

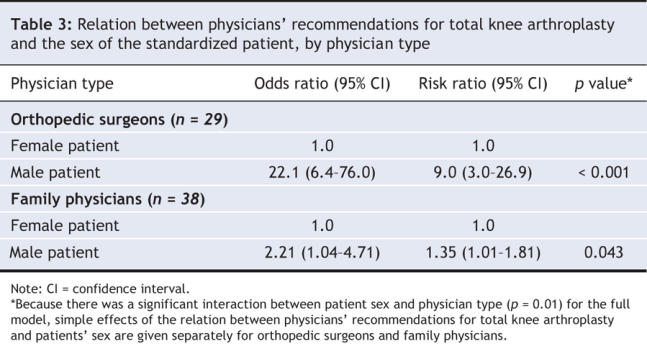

In total, 42% of physicians recommended total knee arthroplasty to the male but not the female standardized patient, and 8% of physicians recommended total knee arthroplasty to the female but not the male standardized patient (odds ratio [OR] 4.2, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.4–7.3, p < 0.001; risk ratio [RR] 2.1, 95% CI 1.5–2.8, p < 0.001). The odds of an orthopedic surgeon recommending total knee arthroplasty to a male patient was 22 times (95% CI 6.4–76.0, p < 0.001) that for a female patient. The odds of a family physician recommending total knee arthroplasty to a male patient was 2 times (95% CI 1.04–4.71, p = 0.04) that for a female patient.

Interpretation

Physicians were more likely to recommend total knee arthroplasty to a male patient than to a female patient, suggesting that gender bias may contribute to the sex-based disparity in the rates of use of total knee arthroplasty.

Disparity in the use of medical or surgical interventions based on patient characteristics, such as sex, ethnic background or socioeconomic status, is an important health care issue.1 Women are less likely than men to receive lipid-lowering medication after a myocardial infarction,2 receive kidney dialysis,3 be admitted to an intensive care unit,4 or undergo cardiac catheterization,5 renal transplantation6 or total joint arthroplasty.7 Although women's preferences for surgery or the information needed to make an informed decision may differ from men and explain sex-based differences in care,8,9 subtle or overt gender bias may inappropriately influence physicians' clinical decision-making.2,5,7 A more pronounced gender bias might be expected when the clinical decision involves an elective surgical procedure such as total joint arthroplasty.

Total hip and knee arthroplasty is the definitive treatment for relieving pain and restoring function in people with moderate to severe osteoarthritis for whom medical therapy has failed.10 Although age-adjusted rates of total joint arthroplasty are higher among women than among men,11 based on a population-based epidemiologic survey, underuse of arthroplasty is 3 times greater in women.7 In prior opinion surveys, more than 93% of referring physicians and orthopedic surgeons have reported that patients' sex has no effect on their decision to refer a patient for, or perform, total knee arthroplasty.12,13 However, there may be a difference between what is reported in a survey and what occurs in clinical practice. The purpose of our study was to determine whether physicians would provide the same recommendation about total knee arthroplasty to a male and a female standardized patient presenting to their offices with identical clinical scenarios that differed only by sex.

Methods

Study design, setting and context

In total, 71 physicians (38 family physicians and 33 orthopedic surgeons) within a 3-hour drive or a 1-hour flight of Toronto, Ontario, were visited by 1 male and 1 female standardized patient between August 2003 and October 2005. We identified orthopedic surgeons who were willing to participate from a previous opinion survey about total knee arthroplasty.12 After being visited by the standardized patients, the orthopedic surgeons were informed about the “temporary waiver” of consent granted by our ethics review committees and given the opportunity to remove their data from the study. Four orthopedic surgeons did not consent to the inclusion of their data. We identified family physicians with open practices using the Canadian Medical Directory and invited them to participate. Family physicians provided written informed consent before being visited by the standardized patients. All participating physicians were blinded as to the patients' status as standardized patients. Physicians were informed that they were participating in a study about clinical decision-making but were not told that the purpose of the study was to assess the effect of patient's sex on decision-making or that the standardized patients would have osteoarthritis.

We recruited 1 man and 1 woman with moderate knee osteoarthritis to be standardized patients. Two orthopedic surgeons (H.J.K. and N.N.M.) confirmed that their disease severity was identical, based on physical examinations and bilateral standing knee radiographs. We chose to include patients with osteoarthritis (rather than actors) to minimize the risk of unblinding the participating physicians and to provide a realistic clinical presentation.14 Neither patient was obese, and they had only mild comorbidities that are considered normal for their age (e.g., controlled hypertension). The standardized patients were not informed of the purpose of our study. Initially, our study included a second pair of standardized patients (1 man and 1 woman with severe knee osteoarthritis) visiting the same physicians. The severe osteoarthritis scenario was abandoned after early evidence suggested that it was futile (Appendix 1, available online at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/178/6/681/DC2).

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Toronto and The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario.

Standardized patient scenarios

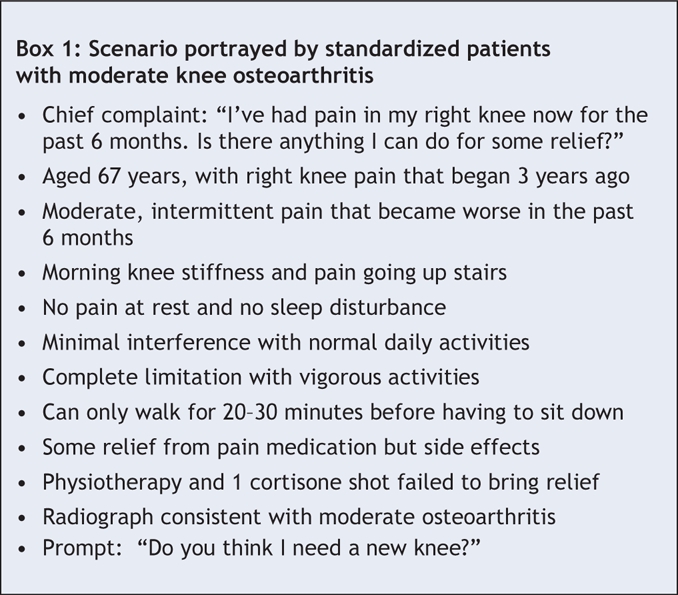

Both standardized patients memorized identical scenarios that included functional capacity, pain severity, amount of sleep disturbance, use of pain medications and all other treatment modalities (Box 1). Their socioeconomic status was scripted as middle class, and both had physically undemanding part-time jobs. Chronic knee pain was given as their chief complaint so that the physician encounter would be focused exclusively on their osteoarthritis. The scenario was scripted such that usual nonoperative treatment options had been exhausted. To ensure standardization of presentation of the scenario, each standardized patient visited each physician only once.16 We instructed the standardized patients to provide their chief complaint as their standard opening sentence to all physicians. They were given detailed instructions on what information could be shared spontaneously with the physicians and what information was to be provided only when asked. If by the end of the visit the physician had not recommended or offered total knee arthroplasty or referral to an orthopedic surgeon, the patients were instructed to prompt the physician by asking “do you think I need a new knee?”

Box 1.

Standardized patient training and quality control

Standardized patients received training by the Standardized Patient Program at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, using established training protocols.14 Training totalled 21 hours and involved a group session lasting 3 hours, 4 group practice and feedback sessions lasting 4 hours each, and a reliability and readiness assessment session lasting 2 hours. The standardized patients began visiting participating physicians once their accuracy of presentation was more than 95% and their reliability in evaluating the physicians' treatment recommendations demonstrated substantial agreement (percentage agreement ≥ 0.85, estimated kappa ≥ 0.61). Each standardized patient attended practice and feedback sessions throughout the study period so that we could periodically monitor their performance. We also conducted a formal validation of the accuracy of the standardized patients' portrayal of the scenario and their reliability in recording physicians' actions by surreptitiously videotaping their performance on 2 occasions using a hidden camera during actual office visits with volunteer test physicians. The mean accuracy of the standardized patients' presentation of the clinical scenario for the 2 test encounters was high (91.3% for the female and 88.5% for the male standardized patient).

Conduct of standardized patient visits

Physicians were asked to complete and return a “detection” postcard if they suspected that a patient was a standardized patient. To all physician visits, the standardized patients brought bilateral standing knee radiographs of their own knees that had been reproduced without any identifying features and without an accompanying radiology report.

Sample size

We estimated the magnitude of the hypothesized effect of patients' sex on the physicians' treatment recommendations based on findings from our population-based study, which showed a greater than 3-fold sex-based disparity in access to total joint arthroplasty (5.3/1000 for women, 1.6/1000 for men).7 To obtain an odds ratio (OR) of 3.3, we assumed that 30.7% of physicians would recommend total knee arthroplasty to the male but not the female patient and that 9.3% would recommend the procedure to the female but not the male patient. For the remaining physicians, we assumed that 30% would recommend total knee arthroplasty to both the male and female patients and that 30% would recommend total knee arthroplasty to neither patient. We estimated sample size based on a 1-sided alternative hypothesis that physicians would be less likely to recommend total knee arthroplasty to the female patient compared with the male patient. We specified a 1-sided hypothesis because the focus of our study was to investigate the potential for gender bias. Using the exact McNemar's test for paired proportions as a conservative sample size estimate, for a power of 80% at α = 0.05 and assuming a 15% dropout rate, we determined that 71 physicians were required.

Statistical analysis

We evaluated differences in the means of continuous variables using Student's t test and differences in proportions using the χ2 test. We performed a binary logistic regression analysis using a generalized estimating equation to assess the effect of patients' sex on physicians' recommendations for total knee arthroplasty. An OR with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was calculated to estimate the strength of association between patients' sex and physicians' recommendations for total knee arthroplasty. Given that outcomes or proportions in the 2 × 2 tables are relatively common (i.e., > 10%), we performed log-binomial modelling by use of PROC GENMOD (SAS version 9.0) to obtain an unbiased estimate of the risk ratio (RR).17 After detecting an overall main effect for patients' sex, we tested for an interaction among the prespecified physician-type subgroups. Given that a 1-sided test of significance at α = 0.05 was used to estimate sample size, results about recommendations for total knee arthroplasty are presented using 1-sided p values and 95% CI. All other tests of significance were 2-sided.

Results

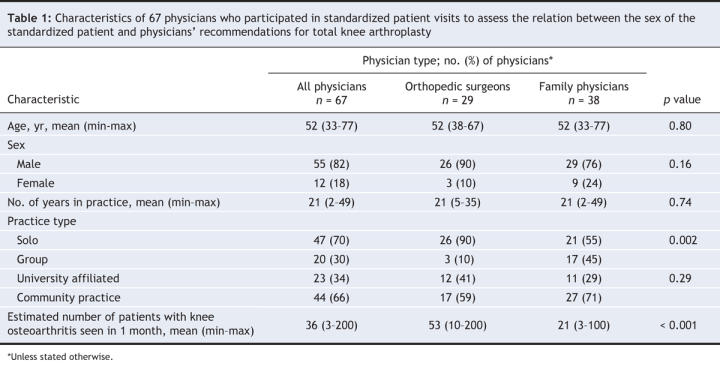

Of the 71 physicians visited by the standardized patients, 67 gave consent to include their data in our study (Table 1). Personal and practice characteristics are representative of practising orthopedic surgeons and family physicians in Ontario.12,13

Table 1

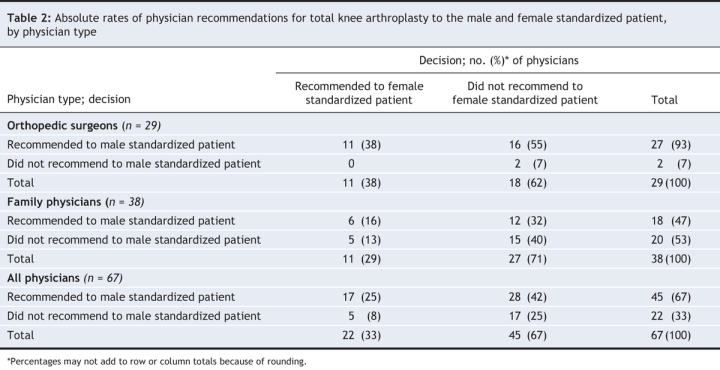

As shown in Table 2, more than 90% of orthopedic surgeons considered at least 1 of our standardized patients with moderate knee osteoarthritis to be an appropriate candidate for surgery, compared with 60% of family physicians. Overall, 67% of physicians recommended total knee arthroplasty to the male patient compared with 33% who recommended it to the female patient. Focusing on the discordant pairs for all physicians, 42% of physicians recommended total knee arthroplasty to the male but not the female patient, and 8% recommended total knee arthroplasty to the female but not the male patient.

Table 2

The overall odds that total knee arthroplasty was recommended to a male patient was 4 times the odds for a female patient (OR 4.2, 95% CI 2.4–7.3, p < 0.001). When these results are expressed as a RR, a male patient was twice as likely as a female patient to receive a recommendation for total knee arthroplasty (RR 2.0, 95% CI 1.5–2.8, p < 0.001). The odds of a male patient receiving a recommendation for total knee arthroplasty from an orthopedic surgeon or being referred for total knee arthroplasty by a family physician were higher than for a female patient (Table 3).

Table 3

Because few of the participating physicians were female, we could not examine the effect of the sex of the physician on our findings. Of the 12 female physicians, 3 recommended total knee arthroplasty to both the male and female patient, 5 recommended it to the male but not the female patient, 2 recommended it to the female but not the male patient and 2 recommended it to neither patient. Female and male physicians had similar rates of recommendation for total knee arthroplasty; 67% of female and 67% of male physicians recommended total knee arthroplasty to the male patient (p = 0.97), and 42% of female and 31% of male physicians recommended total knee arthroplasty to the female patient (p = 0.47).

Of the 67 physicians, 1 family physician detected the male standardized patient and 1 detected both the male and the female standardized patients, giving a detection rate of 2% (3/134 visits). In total, 1 false-positive detection was reported. The detection rate in our study was much lower than the rates previously reported by other researchers using unannounced standardized patients (0%–18%).16,18 The primary reason given by both family physicians who detected the standardized patients was the absence of a radiologist's report with the radiographs. Eliminating the data from the 3 visits involving the detection of a standardized patient did not change our results.

Interpretation

Physicians are trained to ensure that clinical decisions are tailored to the needs of the individual patient and reflect the current state of medical knowledge. On surveys, referring physicians and orthopedic surgeons report that a patient's sex does not affect their decision to refer a patient for, or perform, total knee arthroplasty.12,13 However, we found that, in actual clinical practice, the sex of the presenting patient affected physicians' treatment recommendations. Previous studies that documented sex-related differences in the treatment of osteoarthritis7,19,20 were unable to determine the sources of these differences. We addressed this question by using standardized patients with identical clinical presentations of moderate knee osteoarthritis with chronic knee pain who differed only by sex. Our findings suggest that physicians may be at least partially responsible for the sex-based disparity in the rates of use of total joint arthroplasty.7

There are 3 possible explanations for our findings. First, the participating physicians' decisions to recommend total knee arthroplasty may have been based on conscious attitudes or overt discrimination based on sex. Some physicians have been shown to take women's symptoms less seriously and attribute their symptoms to emotional rather than physical causes21 and to refer women less often22 than men for specialty care even when women have a relatively greater degree of disability. A second possible explanation is that the participating physicians' treatment recommendations were a result of an unconscious bias based on gender. Unconscious bias occurs when a patient automatically activates a stereotype in the physician's memory.23 Discriminatory actions stemming from unconscious biases are not deliberate, and physicians would be unaware of them. Our study suggests that physicians are susceptible to the same unintentional gender biases that are pervasive in the rest of society.24 In our study, physicians may not have recommended total knee arthroplasty to the female patient because an unconscious bias resulting from years of experience tells them, or they've heard from other physicians, that women don't receive the same benefit from total knee arthroplasty as men. This inappropriate preconception may be because women typically receive surgery at a more advanced stage of disease than men19,20 and those with more advanced osteoarthritis have worse surgical outcomes.20,25,26 A third explanation is that despite identical clinical scenarios, the presentation style of our male and female standardized patients may have differed because of their gender. Women typically present their symptoms using a narrative style, speaking more openly and personally about their complaints, whereas men typically present their symptoms using a business-like style, describing their complaints in a more factual or reserved manner.27,28

The results of our study suggest a need for simple tests to detect biases among physicians. Customized implicit association tests29,30 (similar to those at www.projectimplicit.net) may provide a possible mechanism to identify an unconscious or implicit gender bias. Different strategies at multiple levels may be required to address the sex-based disparity in the rates of use of total knee arthroplasty. At the societal level, strategies may need to address fundamental social and economic inequalities.9 At the health policy level, collecting disparity indicator data31 and increasing the diversity among health care providers32 may help to equalize treatment between the sexes. At the organizational level, gender sensitivity in medical curricula has been introduced.33 Our research findings support the need for intervention strategies directed at the level of health care delivery, through clinician education programs to better inform physicians of the true risks of total joint arthroplasty, when and for whom to consider surgery as well as the potential benefits of early treatment.20,25,26 Additional strategies include presenting physicians with data showing that, assuming similar preoperative disease severity, women and men derive similar benefits from total joint arthroplasty.19 However, these intervention strategies may not address the physicians' contribution to the sex-based disparity if the natural social cognition processes that contribute to gender bias are not addressed. Research suggests that individuals have the capacity to overcome their biases and consciously replace automatically activated stereotypes if they are made aware of their biases and are motivated because of personal values or feelings of guilt.23,34 Thus, we propose developing an intervention that focuses on increasing physicians' acceptance and awareness of the automatic nature of social categorization and stereotyping, and that helps physicians self-recognize and challenge their own conscious and unconscious biases that may be influencing their clinical decision-making. Simultaneous interventions directed at patients to address their contribution to the sex-based disparity are integral to the success of these proposed interventions.

An additional observation in our study was that more than 90% of orthopedic surgeons, compared with 60% of family physicians, considered at least 1 of our standardized patients with moderate knee osteoarthritis to be an appropriate candidate for surgery. This suggests that the recommendation of total knee arthroplasty is the right decision and represents the best care for our standardized patients. Because our standardized patients presented without a radiology report, this may have led to fewer specialist referrals by family physicians who may have been uncomfortable interpreting the radiographs. However, it is more likely that while total knee arthroplasty is generally acknowledged by family physicians and orthopedic surgeons to be appropriate for patients with moderate knee osteoarthritis, family physicians tend to overestimate the risks and underestimate the benefits of arthroplasty.12,13

There are several potential limitations to our study. First, only 2 standardized patients were included. However, we took several steps to minimize all clinically relevant and extraneous differences between the 2 patients. We included 1 man and 1 woman with moderate knee osteoarthritis and whose cases were confirmed as being identical in terms of disease severity. Both patients received extensive training to present identical standardized scenarios, and their presentation accuracy was formally tested at the beginning of the study and twice during the study by surreptitiously videotaping each patient's performance during office visits with volunteer test physicians. For all patient presentations, the degree of conformity was high. Although the patients' presentations may have been subtly different, it is unlikely that they varied to an extent that would explain the observed differences in the rates of recommendations. Second, the standardized patients visited only physicians who agreed to be visited. However, we do not believe that the physicians who volunteered would be more biased than those who did not. Third, it is possible that some physicians may more fully investigate osteoarthritic symptoms and discuss treatment options during a patient's second visit. However, we believe that this would have occurred infrequently. Furthermore, the standardized patients' script was written such that at the end of the examination, the patients asked if they needed a new knee joint. Fourth, although our sample size was large enough to detect an overall main effect and to perform 1 subgroup analysis, it was not large enough to address all of the potential subpopulations of interest, such as physician age, sex or site of training. Fifth, the study was performed in a single Canadian province. However, because universal health care reduces access barriers to total knee arthroplasty, Ontario was an excellent setting for this study. Disparities in access to health care have also been reported in the United States; thus, our results are likely not specific to Ontario physicians. Finally, this was a study of 1 surgical procedure. We chose to study recommendations for total knee arthroplasty because of the known sex-based disparity in the rate of use for this procedure.7 We have no reason to believe that the results would have been different for other procedures or treatments. Additionally, although the magnitude of the effect differed, we found a gender bias among both referring family physicians and orthopedic surgeons.

In conclusion, physicians were more likely to recommend total knee arthroplasty to a male rather than to a female patient, suggesting that gender bias may contribute to the sex-based disparity in the rate of use of total knee arthroplasty. Our findings suggest that physicians are prone to the same automatic, unconscious and ubiquitous social stereotyping that affect all of our behaviour. Acknowledging that a gender bias may affect physicians' decision-making is the first step toward ensuring that women receive complete and equal access to total joint arthroplasty. Further research is needed to develop interventions to address the physician's contribution to treatment disparities and to develop tools to measure the effectiveness of these interventions.

@ See related article page 723

Methodological pearl

When a study compares 2 groups, there is an important distinction between whether one truly wishes to know if 1 group is better than the other or, instead, to know whether the 2 groups are different, regardless of direction. Statistically, the testing corresponding to each of these concepts is referred to as a “1-sided” or “2-sided” test respectively. Choosing whether a 1- or 2-sided test is appropriate is sometimes controversial and requires understanding of an important nuance.

We attach a certain amount of credibility to what the p value is implying from our past experiences, which have usually been based on 2-sided p values. If a p value of 0.05 is observed for a 2-sided test, the value attached to it may appear to be 1/20 of making a mistake. However, because we often interpret the result as one group being better than the other (a 1-sided interpretation), the likelihood of making a mistake is really 1/40 since the p value is split when both sides are considered in the testing procedure. In other words, our usual value judgement as to what constitutes statistical significance is based on a 1/40 chance of error. In contrast, when a 1-sided test is used, the chance of error actually is 1/20. Therefore, a conclusion of statistical significance based on a 1-sided p value can appear to meet the usual standard when in fact it does not.

Although the expectation may be that if a difference exists, it will favour a particular group, one can rarely rule out with certainty that this group could instead have a worse outcome, and it would be even rarer that one would not care if this were so. What, then, should editors do when authors have used a 1-sided test to determine their sample size? Some journals require that all p values be 2-sided, but there is a need to respect the design of the study while ensuring that readers interpret the p values with their usual anchor points. For this article, the editors felt a compromise was most appropriate: the reported p value for the primary outcome on which the sample size was based was 1-sided and for all other outcomes the 2-sided p values are reported. — CMAJ

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the physicians who participated in this study. We also acknowledge the invaluable contributions made by the members of the “Operation Knee” research team, especially Dorothy Aungier, Marylyn Peringer, Murray Nisker, Len Berk, Mindy Green, Lois MacKenzie, Werner Thom, Gaby Thom, Sam Osak and Harold Weston. We also thank Jennifer Ionson for her work in recruiting participants, data entry and her unwavering commitment to this project.

Footnotes

Une version française de ce résumé est disponible à l'adresse www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/178/6/681/DC1

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors contributed to the study conception and design. James Wright was the principal investigator and directed the study. Cornelia Borkhoff supervised the implementation of the study, data acquisition, data entry and quality control. Cornelia Borkhoff and James Wright analyzed and interpreted the data. Cornelia Borkhoff wrote the first draft of the manuscript and each coauthor revised it critically for important intellectual content. All of the authors reviewed and approved the final version for publication.

Financial support for this study was provided by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Arthritis Society of Canada. Cornelia Borkhoff is supported by a Peterborough K.M. Hunter Graduate Studentship, a Canadian Arthritis Network Graduate Student Award and a Toronto Star Bursary Award. Gillian Hawker holds the F.M. Hill Chair in Academic Women's Medicine at the University of Toronto and is an Arthritis Society of Canada Senior Distinguished Rheumatology Investigator. James Wright holds the Robert B. Salter Chair in Surgical Research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. James G. Wright, The Hospital for Sick Children, 555 University Ave., Toronto ON M5G 1X8; fax 416 813-6433; james.wright@sickkids.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Lurie N. Health disparities: less talk, more action. N Engl J Med 2005;353:727-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Di Cecco R, Patel U, Upshur RE. Is there a clinically significant gender bias in post-myocardial infarction pharmacological management in the older (> 60) population of a primary care practice? BMC Fam Pract 2002;3:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Kjellstrand CM, Logan GM. Racial, sexual and age inequalities in chronic dialysis. Nephron 1987;45:257-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Fowler RA, Sabur N, Li P, et al. Sex-and age-based differences in the delivery and outcomes of critical care. CMAJ 2007;177:1513-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians' recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med 1999;340:618-26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Bloembergen WE, Mauger EA, Wolfe RA, et al. Association of gender and access to cadaveric renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis 1997;30:733-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, et al. Differences between men and women in the rate of use of hip and knee arthroplasty. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1016-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, et al. Determining the need for hip and knee arthroplasty: the role of clinical severity and patients' preferences. Med Care 2001;39:206-16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Katz JN. Patient preferences and health disparities. JAMA 2001;286:1506-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, et al. Health-related quality of life after knee replacement surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998;80:163-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.DeBoer D, Williams JI. Surgical services for total hip and total knee replacements: trends in hospital volumes and length of stay for total hip and total knee replacement. In: Badley EM, Williams JI, editors. Patterns of health care in Ontario: arthritis and related conditions. ICES Practice Atlas. Toronto: Continental Press; 1998. p. 121-4.

- 12.Wright JG, Coyte P, Hawker G, et al. Variation in orthopedic surgeons' perceptions of the indications for and outcomes of knee replacement. CMAJ 1995;152:687-97. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Coyte PC, Hawker GA, Croxford R, et al. Variation in rheumatologists' and family physicians' perceptions of the indications for and outcomes of knee replacement surgery. J Rheumatol 1996;23:730-8. [PubMed]

- 14.McLeod PJ, Tamblyn RM, Gayton D, et al. Use of standardized patients to assess between-physician variations in resource utilization. JAMA 1997;278:1164-8. [PubMed]

- 15.Elderkin-Thompson V, Waitzkin H. Differences in clinical communication by gender. J Gen Intern Med 1999;14:112-21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Tamblyn RM, Abrahamowicz M, Berkson L, et al. Assessment of performance in the office setting with standardized patients: first-visit bias in the measurement of clinical competence with standardized patients. Acad Med 1992;67:S22-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.McNutt L-A, Wu C, Xue X, et al. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:940-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Woodward CA, McConvey GA, Neufeld V, et al. Measurement of physician performance by standardized patients. Med Care 1985;23:1019-27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Katz JN, Wright EA, Guadagnoli E, et al. Differences between men and women undergoing major orthopaedic surgery for degenerative arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:687-94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Holtzman J, Saleh K, Kane R. Gender differences in functional status and pain in a Medicare population undergoing elective total hip arthroplasty. Med Care 2002;40:461-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Bernstein B, Kane R. Physicians' attitudes toward female patients. Med Care 1981;19:600-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Franks P, Clancy CM. Referrals of adult patients from primary care: demographic disparities and their relationship to HMO insurance. J Fam Pract 1997;45:47-53. [PubMed]

- 23.Devine PG. Stereotypes and prejudice: their automatic and controlled components. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;56:5-18.

- 24.Ayres I. Pervasive Prejudice? Unconventional evidence of race and gender discrimination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2001.

- 25.Fortin PR, Clarke AE, Joseph L, et al. Outcomes of total hip and knee replacement: preoperative functional status predicts outcomes at six months after surgery. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:1722-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Petterson SC, Raisis L, Bodenstab A, et al. Disease-specific gender differences among total knee arthroplasty candidates. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:2327-33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Davis K. Power under the microscope [dissertation]. Dordecht (Netherlands): Free University Amsterdam; 1988.

- 28.Birdwell BG, Herbers JE, Kroenke K. Evaluating chest pain. The patient's presentation style alters the physician's diagnostic approach. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:1991-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JLK. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998;74:1464-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Nosek B, Banaji M, Greenwald AG. Project Implicit, joint project of the University of Virginia, Harvard University and the University of Washington. Available: www.projectimplicit.net (accessed 2008 February 11).

- 31.Mensah GA. Eliminating disparities in cardiovascular health: Six strategic imperatives and a framework for action. Circulation 2005;111:1332-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Gijsbers van Wijk CMT, van Vliet KP, Kolk AM. Gender perspectives and quality of care: towards appropriate and adequate health care for women. Soc Sci Med 1996;43:707-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Zelek B, Phillips SP, Lefebvre Y. Gender sensitivity in medical curricula. CMAJ 1997;156:1297-300. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Rudman LA, Ashmore RD, Gary ML. “Unlearning” automatic biases: the malleability of implicit prejudice and stereotypes. J Pers Soc Psychol 2001; 81:856-68. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.