Abstract

Pure tone intensity discrimination thresholds can be elevated by the introduction of remote maskers with roved level. This effect is on the order of 10 dB [10log(ΔI/I)] in some conditions and can be demonstrated under conditions of little or no energetic masking. The current study examined the effect of practice and observer strategy on this phenomenon. Experiment 1 included observers who had no formal experience with intensity discrimination and provided training over six hours on a single masked intensity discrimination task to assess learning effects. Thresholds fell with practice for most observers, with significant improvements in 6 out of 8 cases. Despite these improvements significant masking remained in all cases. The second experiment assessed trial-by-trial effects of roved masker level. Conditional probability of a ‘signal-present’ response as a function of the rove value assigned to each of the two masker tones indicates fundamental differences among observers’ processing strategies, even after six hours of practice. The variability in error patterns across practiced listeners suggests that observers approach the task differently, though this variability does not appear to be related to sensitivity.

I. INTRODUCTION

In energetic masking, the presence of a masker is thought to corrupt the neural encoding of the signal, thereby limiting further processing of that signal. In contrast, in informational masking the signal is thought to be well represented at the periphery, but it is assumed that the central auditory system is not able to make optimal use of that peripheral information. This effect is frequently studied in the context of pure tone detection in the presence of masker tones with randomly selected frequencies (e.g., Kidd, Mason, Deliwala et al., 1994; Neff & Dethlefs, 1995). Introducing a masker level rove in this paradigm has little or no additional effect on pure tone detection threshold provided those maskers are sufficiently remote from the signal frequency to minimize energetic masking (Neff & Callaghan, 1988; Oh & Lutfi, 1998). Masker level uncertainty is associated with substantial informational masking for masked intensity discrimination, however (Buss, 2007; Doherty & Lutfi, 1999; Fantini & Moore, 1994; Stellmack, Willihnganz, Wightman et al., 1997). For example, a recent study by Buss (2007) showed that intensity discrimination threshold of a 50-dB SPL standard tone at 948.7 Hz was elevated by approximately 10 dB (10log(ΔI/I)) with the inclusion of masker tones at 300 and 3000 Hz, roved in level on each interval (50 dB SPL ±8 dB). This effect was shown to be independent of energetic masking, and thus (by exclusion) was attributed solely to informational masking. Following the convention of Fantini and Moore (1994), this effect will be referred to as across-channel interference (ACI).

Previous work on ACI has shown that segregation cues improve thresholds (Buss, 2007). In one manipulation the target and the maskers were either pure tones or tones that had been amplitude modulated via multiplication with a raised 10-Hz sinusoid; thresholds were highest when envelopes were coherent across all three tones and fell when the target and maskers had mismatched envelopes. Gating the masker on prior to the onset of the target also reduced thresholds. These effects were interpreted as showing that segregation cues can facilitate analytic listening, but that in the absence of these cues observers were adopting a synthetic listening strategy, incorporating information about the masker tone level into the discrimination decision despite the fact that this strategy reduces sensitivity. There was a small but significant threshold elevation in conditions with fixed-level remote maskers which could likewise be reduced by segregation cues, suggesting that some synthesis of information across frequency took place even under conditions of minimal uncertainty.

The current studies sought to more carefully characterize the practice effects and underlying perceptual processes associated with ACI. It is commonly assumed that informational masking reflects more than just inattention or confusion regarding the psychoacoustic task (e.g., Durlach, Mason, Kidd et al., 2003). In the context of ACI, this distinction would differentiate between a percept lacking robust cues to target level independent of masker level (informational masking), as opposed to confusion regarding which of a set of robust cues are most predictive of a signal-present interval (task confusion). Experiment 1 tested observers who were naïve with respect to ACI stimuli on a sequence of six 1-hour sessions to assess whether task confusion played a role in the initial results. One goal of the present study was to determine whether extended practice would allow development of an analytic listening strategy in the absence of stimulus cues associated with segregation. If observers are able to voluntarily adopt an analytic processing strategy that minimizes the contribution of the masker tones, then it seems likely that this would be evident within a six-hour series of practice trials. The second experiment characterized the listening strategy adopted after extensive practice in terms of the probability of a ‘signal-present’ response conditional on the level of each masker tone. This approach will discriminate among a family of processing strategies that could elevate thresholds in these conditions.

II. EXPERIMENT 1: Changes in ACI with practice

Informational masking for tone detection under conditions of masker frequency uncertainty has been shown to be reduced with practice for some listeners (Neff & Callaghan, 1988; Neff & Dethlefs, 1995). Studies of this training effect indicate that most benefits are obtained in the first 600 trials (Neff & Callaghan, 1988). The question considered here is whether practice has a comparable effect for intensity discrimination in the presence of roved-level maskers, or whether extended practice with feedback eliminates the effect. Asymptotic performance on ACI is of practical importance in determining how much training to provide prior to data collection in future studies. More importantly, it is also of theoretical significance; the implications of the ACI effect would be quite different if it were due merely to task confusion regarding what aspects of the percept are the most reliable indicators of a signal-present interval, as opposed to reflecting immutable limitations of the percept.

A. Methods

Observers

Observers were eight adults, from 17 to 50 years old (mean of 27.9 years). All had thresholds of 20 dB HL or less at octave frequencies 250–8000 Hz (ANSI, 1996), and none reported a history of chronic ear disease. About half of these observers had previously participated in psychoacoustical experiments, and none had prior experience listening to ACI or other stimuli designed to assess informational masking.

Stimuli

The target was a 948.7-Hz pure tone. This component had a standard level of 50 dB SPL, and the task was to detect an increment in this level. The maskers, when present, were synchronously gated tones at 300 and 3000 Hz. The level of each masker was roved independently based on draws from a Uniform distribution spanning 42–58 dB SPL. Both target and masker tones were 220-ms in duration, including 10-ms cos2 onset and offset ramps, and the inter-stimulus interval was 500 ms. All stimuli were generated in software (RPVDs; TDT), played out of one channel of a DAC (RP2; TDT), routed through a headphone buffer (HB7; TDT) and presented to the left ear with circumaural headphones (Sennheiser, HD 265).

Procedures

Thresholds were estimated by way of a 2-alternative forced-choice, 3-down 1-up track estimating the 79% correct point (Levitt, 1971). Target level increments were made by in-phase addition of a pure tone at the target frequency of 948.7 Hz. At the outset of the track, the level of this tone was adjusted in steps of 4 dB, and this step was reduced to 2 dB after the second track reversal. The track continued until a total of eight reversals was obtained, and the threshold was computed as the average level at the last six reversals. Lights on a handheld response box indicated listening intervals and provided feedback. At the outset of each track the signal level was 10 dB above the most recent threshold (or anticipated threshold, in the case of the first track). Observers provided data over three weeks, listening in a total of six 1-hour sessions.

On days 1, 3 and 5 the test session began with three consecutive threshold estimates in the no-masker condition (i.e., intensity discrimination in quiet). During the remainder of these sessions observers ran sequential blocks of the masker-present condition. On days 2, 4 and 6 observers just ran sequential blocks of the masker-present condition. Observers were encouraged to complete as many tracks as possible during a 1-hour session, with a 5–10 minute break offered at the midpoint of each session.

B. Results

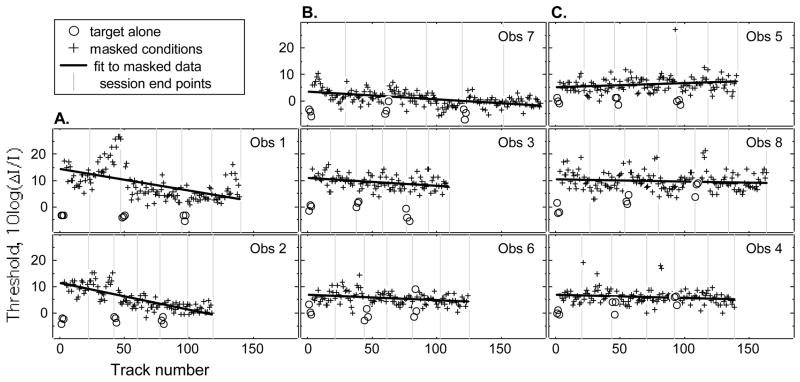

Thresholds as a function of trial number are plotted in Figure 1, with each observer’s data in a separate panel. Thresholds in the no-masker condition are shown with open circles, and those in the masker-present condition with pluses. Grey vertical lines indicate break points between data collection sessions, and thick black lines show the line fits to the masker-present conditions, as described below. Observers completed a total of 109 to 180 tracks, including the nine no-masker tracks. On average, each track included 50 trials, so the total number of trials completed by each observer ranged from approximately 5500 to 9000.

Figure 1.

Thresholds are plotted in units of 10log(ΔI/I) as a function of trial number for each observer in Experiment 1. Estimates of thresholds for intensity discrimination in quiet are indicated with open circles, while those in the presence of maskers are indicated with plus-signs. The dashed vertical lines segmenting each panel indicate the beginning and end of each of six test sessions. Panels are grouped by magnitude of the practice effect: data in column A show robust practice effects, those in column B show more modest improvements, and data in column C show the smallest effects.

Three estimates of intensity discrimination in quiet were obtained on three occasions for each observer: averaging across test session and across observers, the mean threshold was −0.6 dB. A repeated measures ANOVA with three levels of TIME (day 1, day 3, day 5) indicated no difference in thresholds as a function of measurement time point (F2,14=0.82, p=0.46). In contrast, for the masker-present conditions mean thresholds improved from 8.1 dB on day 1 to 5.1 dB on day 6.

Data in the masker-present condition were fit with a line to characterize the change in threshold as a function of trial number. While some of the data would be better fitted with a more complex function, these fits do seem to capture the general trends of interest. Inspection of Figure 1 suggests that there are marked individual differences in the extent to which practice reduces thresholds in the masker-present condition. The data in column A show evidence of robust practice effects in the masker-present condition. For Obs 1 and Obs 2, thresholds changed by −0.08 and −0.10 dB/trial, respectively (p<0.00001). Fits to their data estimate about 11.5 dB improvement over the course of training in both cases, though closer inspection of the line fits suggest that this may be an overestimate, as thresholds appear to have asymptoted prior to the end of day 6. The data in column B show more modest evidence of practice effects. For these observers, improvement was −0.02 to −0.03 dB/trial (p<0.0005), and line fits estimate improvement in thresholds from 2.6 to 5.3 dB. Data in column C show the weakest evidence of improvement as a function of trial number. The data of Obs 4 are consistent with a modest threshold improvement, with the line fit estimating a significant slope of −0.01 dB/trial and threshold reduction on the order of 2 dB. The line fitted to the data of Obs 8 was not significantly different from a slope of zero (p=0.21). The data of Obs 5 were fitted with a line indicating worsening in performances over time, on the order of 2 dB over all trials, with a slope of 0.01 dB/trial (p<0.05); this result was qualitatively unchanged when data were refitted omitting the single high threshold at the end of day 4.

Among the observers who showed improvement with practice, the smallest ACI effect at asymptote was estimated as 2.2 dB for Obs 7. The significance of this effect was assessed by way of a single-sample t-test assessing whether the mean of the no-masker thresholds is lower than the best threshold predicted by the line fitted to the masker-present data (−1.95 dB). This test indicated a significant difference (t8=3.29, p<0.05, two-tailed). The significance of ACI was tested in a similar manner for the remaining 7 observers and found to be significant in all cases (p<0.05). This result supports the conclusion that the ACI was significant after 6 hours of practice for all observers.

D. Discussion

Results of these extended practice trials suggest that practice with ACI stimuli improves performance for most observers. Of the eight observers tested, two showed improvement on the order of 10 dB, while others made more modest gains or failed to benefit from training. Visual inspection of Figure 1 suggests that those observers who did show marked improvement made the fastest gains in the first two to three days of training. By the end of day 3 most observers had completed between 3000 and 4000 trials. This period of improvement is longer than the 600 trials reported by Neff and her colleagues (Neff & Callaghan, 1988; Neff & Dethlefs, 1995) as the point at which most observers had reached asymptotic performance for detection of a tone in the presence of remote maskers of uncertain frequency and amplitude.

Mean thresholds collected on day 1 indicate 8 dB of ACI, similar to the approximately 10-dB of ACI under comparable stimulus conditions of Buss (2007). That study employed stimuli with the same frequencies and levels as used here, but with a longer duration signal (500-ms instead of 220-ms). That study concluded that the roved masker ACI was functionally free from energetic masking and so could be attributed solely to informational masking. It was argued that observers processed these stimuli synthetically, weighting masker level information despite the fact that these components do not convey task-related information. In this sense ACI resembles profile analysis under conditions where the across-frequency cue has been corrupted by independent perturbations of masker tones (Kidd, Mason, & Green, 1986). The results presented here suggest that while the mean effect size may decrease with training, it is not eliminated with 6 hours of practice. The reduction in ACI with training could be interpreted as an increase in the degree to which the observer can voluntarily engage in analytic listening.

Thresholds in quiet did not show any signs of improvement over the course of this experiment. In fact, mean thresholds rose over the course of the study for two listeners (Obs 4 and Obs 8). While this result may have been due to failure to sustain attention or motivation over the many hours of listening, it could also represent a shift in the strategy. Such an effect may be related to the group effects noted by Green and Mason (1985) when comparing intensity discrimination in naïve observers and observers with extensive training in profile analysis. In that study observers who had previously practiced in profile analysis tended to perform more poorly on intensity discrimination in quiet than those observers who had not received such training; while this difference could have been due to training effects, the authors also noted that selection criteria for previous profile analysis studies could have identified groups with different sensitivity prior to stimulus exposure. In contrast to profile analysis, a synthetic listening strategy based on across-frequency level comparisons is markedly non-optimal for the masked intensity discrimination task considered here. However, hours of exposure to ACI stimuli may have biased Obs 4 and 8 to adopt a listening strategy similar to that suited to profile analysis, which could in turn adversely affect thresholds in quiet.

III. EXPERIMENT 2: Error patterns

The second experiment sought to investigate the underlying perceptual factors associated with ACI by estimating contributions of the low and high frequency masker tones. The paradigm used here shares some features with COSS analysis (Berg, 1989), where weights describing the combination of information are derived based on the relationship between random variability in some aspect of the stimulus and the probability of a signal-present response. This general approach has been used in previous studies of informational masking (Doherty & Lutfi, 1999; Neff & Odgaard, 2004; Stellmack, Willihnganz, Wightman et al., 1997). The model underlying the COSS analysis assumes that independent information is combined linearly across weighted channels. In contrast, the current paradigm restricted stimulus variability (in this case, rove) to a family of 5 levels and computed the conditional probability of a ‘signal-present’ response for each of 25 possible combinations of rove (5 low × 5 high frequency masker tone levels). Reporting the probability for all possible combinations of rove has the advantage that interactions of low and high masker rove values can be assessed. This approach resembles that used by Dye et al. (1994) to assess synthetic vs. analytic listening a binaural task.

Whereas the previous studies of informational masking cited above have reported significant individual differences in weighting strategies, the present study was undertaken to test specific predictions regarding the processing underlying ACI. Pure tone intensity discrimination has been shown to make use of information distributed across the auditory filters stimulated by that tone (e.g., Viemeister, 1972), so even in the absence of maskers this task is based weighted information across frequency. Buss (2007) modeled intensity discrimination in the presence of fixed-level maskers based on the change in partial loudness (Moore, Glasberg, & Baer, 1997) with addition of a signal tone; while this approach did a reasonable job of predicting thresholds for fixed-level maskers, it severely underestimated thresholds in the presence of roved-level maskers. Failure of the model to account for thresholds in the presence of a pair of roved-level masker tones could be attributed to a poor internal representation of the excitation pattern associated with the no-signal stimulus in the observer’s decision process. An inaccurate representation of the no-signal stimulus could result in stimulus energy associated with a masker tone being mistaken for energy associated with a signal. Such a mechanism would result in a positive correlation between masker level and probability of a ‘signal-present’ response.

Alternatively, Buss (2007) hypothesized that intensity discrimination in the presence of roved-level maskers could involve obligatory synthetic processing similar to that underlying profile analysis. In the profile analysis paradigm the relative levels of tones distributed across frequency provide a very potent cue to the presence of a signal; in the typical paradigm, the signal can be defined as an increment in level of one tone (the target) relative to a family of flanking tones. If ACI is based on a similar type of processing, this might be reflected in a higher probability of a ‘signal-present’ response when both maskers are at a low level relative to the target tone, with reduced probability of a ‘signal-present’ response as the maskers increase in level relative to the target. Such a strategy might be based on relative levels of target and masker tones for a supra threshold signal, where, on average, energy at the target frequency exceeds that at either masker frequency during the signal-present listening interval. If an observer adopted this strategy, the probability of a ‘signal-present’ response would be negatively correlated with masker tone level.

A. Methods

Observers

Observers were seven normal-hearing adults, between 19 and 50 years old (mean of 37 years). All met the inclusion criteria of the previous experiment, and all had participated in a study of ACI prior to this experiment. Observers 1–5 had previously completed Experiment 1. Observers 9 and 10 had prior experience in another ACI study not included in the current report; that study also spanned approximately six 1-hour sessions and included a range of ACI conditions.

Stimuli

As in Experiment 1, the target was a tone at 948.7 Hz and maskers were tones at 300 and 3000 Hz. The task was to detect an increment in the 50-dB standard level of the target. In contrast with the previous study, maskers were independently roved with Uniform draws from a restricted set of possible levels: including −8, −4, 0, +4 and +8 dB re: 50 dB SPL. Thus, there were 25 possible combinations of low- and high-frequency masker levels.

Procedures

Stimuli were presented in a 2-alternative, forced-choice paradigm, with a 3-down 1-up stepping rule estimating 79% correct (Levitt, 1971). As in Experiment 2, initial signal level adjustments for the tone added to the target were made in steps of 4 dB, reduced to 2-dB after the second track reversal. In contrast to Experiment 1, the track continued for a total of 12 track reversals, and the final threshold estimate was computed as the mean level at the last 10 track reversals; this relatively large number of track reversals was employed to increase the number of trials using a threshold-level signal. The rove value assigned to each masker in each interval and the observer’s response were recorded after each trial. This information was saved to disk for later analysis. All testing was performed in one condition, with masker tones present. Three 1-hour sessions were completed within a two-week span.

B. Results

Over the course of this experiment observers completed between 39 and 58 threshold estimation tracks. Mean thresholds for all observers spanned 2.5 to 11.0 dB, with an across-observer mean of 7.2 dB. These thresholds are comparable to the those obtained in Experiment 1 using rove values drawn from a continuous Uniform distribution spanning ±8 dB re: 50 dB SPL, supporting the assumption that limiting masker rove values did not substantially change the task.

The relationship between a ‘signal-present’ response and each value of masker rove was assessed based on the record of trial-by-trial stimulus characteristics for each observer. For each threshold track the point associated with the second track reversal was identified. Data prior to this point were excluded from further analysis, as the signal itself was likely to have dominated responses at the beginning of the track. Information from the remaining trials was used to compute two matrices: 1) the total number of times each of the 25 possible masker rove configurations was presented, considering stimuli in both intervals of each trial and 2) the total number of times each configuration was identified by the observer as containing the signal, regardless of whether the observer response was correct. Dividing the second matrix by the first produces the probability of a ‘signal-present’ response for each of the 25 masker rove combinations. Using this procedure for the current data set, each cell in the matrix was based on between 135–281 data points for each observer.

Stability of the probability matrices was assessed in the following manner. Each observer’s data were reanalyzed in two blocks, one based on the first half of trials and the other based on the second half of trials, and the correlation between the resulting pair of matrices was computed. Confidence intervals for these correlations were calculated with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (n=7): the criterion for significance (one-tailed) is r=0.48 for α=0.05. Correlations for individual observer’s data ranged from r=0.93 to r=0.33. Only Obs 4’s data failed to reach the criterion of significance, indicating that the probability matrices reported here capture trends that are consistent over the course of the experiment for all but one observer.

Figure 2 shows the conditional probabilities for each of the 25 masker rove configurations for each observer. Shading in each cell represents the probability of a ‘signal-present’ response, with lighter shading indicating higher probability, as indicated in the key. Because this is a 2-alernative task, values above 0.5 reflect positive weights, values below 0.5 reflect negative weights, and values near 0.5 can be interpreted as weights at or near zero. The text above each panel indicates the associated split-half correlation, as well as the mean threshold across trials associated with each data set. Recall that masker level was not predictive of the presence of a signal, so the pattern of dependencies shown here does not reflect any aspect of optimal processing.

Figure 2.

Results for Experiment 2 are plotted separately for each observer. Panels show probability of a ‘signal-present’ response for each of 25 combinations of masker level, with rove assignment of the low-frequency masker indicated on the ordinate and that of the high-frequency masker on the abscissa. Shading indicates conditional probability of a ‘signal-present’ response, as indicated in the key.

The top row of panels shows data for which a non-uniform pattern of probabilities was evident based on both visual inspection and on high values of split-half correlation. Observers 5 and 9 tended to select intervals with high values of masker rove as the signal interval, as evidenced by the white shading in the upper right of each panel. This pattern of results is consistent with the hypothesis that ACI is due to overly broad spectral integration of level information around the target frequency, such that the masker energy is mistaken for spread of excitation due to the presence of a signal. In contrast, data of Obs 1 show the opposite trend, with low values of masker rove associated with the highest probability of a ‘signal-present’ response. This pattern is consistent with a strategy based on a spectral profile, with the target tone higher in level than the masker tones. Observers do not seem to attend equally to the low and high frequency masker tones. The results of Obs 3 and 9 appear to be dominated by the level of the 3-kHz masker tone, as evidenced by the vertical trends in the data, while those of Obs 1 and 5 appear to be more influenced by the 300-Hz masker tone, as evidenced by the horizontal trends in the data.

The bottom row of panels in Figure 2 show results of Obs 2, 4 and 10; these data tend towards more uniform probabilities as a function of masker level. Such a pattern might be obtained if the decision process was unaffected by masker tone levels. If that were the case, then one might expect thresholds to be lower for this group than in the group with less uniform weighting. Comparison of mean thresholds for the two groups does not bear this out, however. As noted above each panel in Figure 2, thresholds for both groups include examples of relatively good performance and relatively poor performance (2.9 to 11.7 dB in the group with variable weights vs. 2.5 to 11.0 dB in group with more uniform weights).

C. Discussion

The probability of a ‘signal-present’ response conditional on the level of the low-and high-frequency masker tone rove values suggests that some observers were consistently incorporating masker level into their processing strategy despite the fact that this information is not predictive of the correct response. The consistency of this non-optimal weighting does not appear to be related to sensitivity; those observers with relatively uniform weights across stimulus components were no more sensitive to intensity increments at the target frequency than those observers who incorporated masker level in a reliable way. A likely explanation of uniform probability in this group is that masker tone level was weighted inconsistently, due to volatility of strategy over the course of the experiment or due to a strategy that cannot be captured in terms of fixed weights. This finding is consistent with the report of Lutfi et al. (2003) which showed individual differences in the extent to which a fixed-weight model was able to predict the form of a psychometric function for tone detection in the presence of frequency- and level-roved masker tones. The wide range of individual differences for thresholds obtained here is also consistent with previous data on the contribution of informational masking components to intensity discrimination in the presence of roved-level maskers (Doherty & Lutfi, 1999).

Only one observer’s data (Obs 1) resembled the pattern predicted based on the analogy between ACI and profile analysis. For this observer, the probability of a ‘signal-present’ response was negatively correlated with masker level. Such a pattern might result from the observer monitoring the level of the tone at the target frequency relative to the level of both maskers and responding ‘signal-present’ when the target exceeds the masker level. Other observers clearly did not employ this strategy, including two (Obs 5 and 9) who appeared to respond based on the opposite rule – ‘signal-present’ if the level of the target tone is below that of the masker tones. In the typical profile analysis paradigm a ‘signal-present’ interval is cued by a target level which exceeds that of the masker tones. However, spectral profile discrimination has also been demonstrated for other profile features, including a decrement in the target component (Ellermeier, 1996). Analogously, it is possible observers in the present ACI task could be ‘listening for’ a profile characterized by a relatively low target tone level or some other relationship across tones. It is unclear how such a strategy would originate given the statistics of the stimuli used here. However, given that any weighting of the masker tones is non-optimal in this task, it would not be too surprising for the pattern of weights to be unrelated to the statistics of the stimuli.

The results obtained here can also be compared to those of Neff and Odgaard (2004). In that study, frequency discrimination was measured in the presence of maskers composed of tones with roved frequency, and observers were shown to put more weight on low-frequency masker tones than high-frequency masker tones. In the current study some of the observers’ responses were correlated more strongly with the low- than the high frequency masker level, with either positive or negative correlation (Obs 5 and Obs 1, respectively). This was not the case for all observers, however.

One potential advantage of representing conditional probabilities of a signal-present response for each roved masker level is that this method can capture nonlinear interactions between low- and high-frequency maskers. For example, if large level discrepancies between the two maskers were associated with increased probability of a ‘signal present’ response, this would be reflected in dark shading along the negative diagonal, and would not be modeled well in terms of the linear combination of weights from the two maskers. Data for each observer were reanalyzed to determine a weight for each masker tone based on the correlation between rove level and the probability of a ‘signal-present’ response collapsed across all values of the opposing masker tonei. Weights associated with each masker are reported separately for each observer in Table I. A matrix of conditional probabilities for all 25 combinations of rove values was then estimated based on these two weights. This estimate closely resembled the original matrix in most cases. This was quantified by computing the correlation between the original probability matrix and the two-weight matrix. These correlations are comparable to or higher than the split-half correlations reported in Figure 2 in all cases but one. For Obs 2 the split-half correlation was higher than the correlation between the original and the two-fit matrices (r=0.61 and r=0.42, respectively), raising the possibility that nonlinear interactions could play a role in this observer’s results. In order to provide additional insight into the results of this observer, the associated data from Figure 2 are also shown in table form (Table II). The marginal means shown here give some indication of the response contingencies characterizing the strategy used by this observer: the probability of a ‘signal present’ response was elevated at the extremes of the 300-Hz component rove range and in the middle of the 3-kHz component rove range. This pattern suggests that Obs 2 was using a cue based on the magnitude of deviations from the 50-dB standard level rather than absolute component levels. This evidence of a nonlinear effect of masker level for the data of Obs 2 stands in contrast to the good fits achieved with the two-weight linear fit for the remaining observers’ data.

Table I.

Two-fit weight estimates for the low (300-Hz) and high (3000-Hz) masker tones. These values can be interpreted as the change in probability of a ‘signal present’ response for a 1-dB change in masker level. The final column shows the correlation between the probability matrix computed based on data and that reconstructed based on the pair of weights, as described in Footnote 1.

| low-freq | high-freq | correlation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obs 1 | −0.0198 | −0.0009 | 0.96 |

| Obs 2 | −0.0049 | −0.0008 | 0.42 |

| Obs 3 | −0.0039 | 0.0194 | 0.92 |

| Obs 4 | −0.0046 | 0.0041 | 0.79 |

| Obs 5 | 0.0229 | 0.0050 | 0.97 |

| Obs 9 | 0.0099 | 0.0187 | 0.90 |

| Obs 10 | −0.0086 | 0.0074 | 0.89 |

Table II.

Conditional probabilities associated with the data of Obs 2 are shown as a function of the level of the 300-Hz and 3-kHz masker tone, reported in dB re: 50 dB SPL. The final column and the final row show the associated mean probabilities.

| 3-kHz level | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300-Hz level | −8 | −4 | 0 | 4 | 8 | Mean |

| 8 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.54 | (0.51) |

|

|

||||||

| 4 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.42 | (0.46) |

|

|

||||||

| 0 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 0.36 | (0.43) |

|

|

||||||

| −4 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.46 | (0.52) |

|

|

||||||

| −8 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.50 | (0.57) |

|

|

||||||

| mean | (0.46) | (0.53) | (0.55) | (0.50) | (0.46) | |

V. CONCLUSIONS

Experiment 1 showed that the ACI effect can be reduced substantially with practice. Significant improvements were obtained in 6 of the 8 observers tested, but ACI was still significantly greater than zero for all observers after 6 hours of practice. The time-course of training appeared to be prolonged relative to previous reports of training effects in studies of tone detection in the presence of an informational masker (Neff & Dethlefs, 1995). The pattern of improvement observed here is perhaps more consistent with the report of Kidd, Mason, & Green (1986) which documented a prolonged period of practice for profile analysis, with threshold improvement out to 3000 trials. If the ACI effect is due to a synthetic listening strategy, then the current results suggest that this strategy is adaptable for some listeners, but that even extended practice does not equip an observer to adopt a wholly analytic listening strategy.

In Experiment 2 the probability of a ‘signal-present’ response was computed for each of a family of possible low- and high-frequency masker rove values. The results indicated a range of weighting strategies, including both positive and negative correlation between level and ‘signal-present’ response. As such, some observers’ data were consistent with overly broad spectral integration of the level cue and others with a cue based on greater energy at the target than masker frequencies (positive and negative correlations, respectively). There were also individual differences in degree to which the low or the high frequency maskers contributed to performances. There appears to be a great deal of latitude in the exact mechanism by which information is combined across frequency, including whether a ‘signal-present’ response is positively or negatively correlated with masker level. Most of the data were modeled accurately by assuming linear combination of independent weights applied to the two masker tones, as previously assumed, suggesting that the masker effects combine linearly for most but not all observers.

One interpretation of the present data is that ACI is due to different mechanisms: broadly integrating spectral level cues in some listeners and an across-channel comparison akin to spectral profile analysis in others. Alternatively, observers could be comparing levels across frequency in the manner of a spectral profile task in all cases, but with different expectations regarding the spectral profile associated with a signal-present interval. On average, addition of a signal tone elevates energy at the target as compared to the masker frequencies, so it was hypothesized a priori that that the probability of a ‘signal-present’ response would be negatively correlated with masker level. That is, it was expected that observers would be listening for a target tone exceeding the level of the maskers. However, individual observers could form spurious expectations regarding the relationship between tones in the presence of a signal, perhaps based on early experience or inherent bias. It is unclear how such expectations would come about, but given that the best strategy in the ACI task is to ignore masker level, any profile strategy is in some sense spurious. The range of response patterns obtained is consistent with the hypothesis that synthetic listening is somewhat obligatory for the current stimuli, but that the across-channel profile associated with the signal interval appears to be arbitrary across observers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH NIDCD (RO1 DC007391). Thanks are due to Robert Lutfi, Walt Jesteadt, Lori Leibold and Joseph Hall for helpful comments and discussion of this material.

Footnotes

Weights were estimated based on the probability of a ‘signal present’ response in the following manner. The matrix associated with each observer’s data can be defined as Pi,j, where subscripts indicate the index associated with the low (i) and high (j) frequency masker tone levels. The levels associated with both i and j dimensions are defined as: X=[−8, −4, 0, 4, 8]

The contribution of each masker tone alone was quantified by averaging probabilities across either i or j dimensions and subtracting 0.5 (chance performance for the 2AFC task). Weights for the low (WL) and high (WH) frequency maskers were then defined as the slope of the line fitted to these adjusted averages as a function of X.

Probability matrices for the combined effects of WL and WH were estimated based on these weights using the following procedure, where a is the contribution of high frequency maskers, b is the contribution of low frequency maskers and Q is the combination, incremented by 0.5 for comparison with the data.

References

- ANSI. ANSI S3-1996, American National Standards Specification for Audiometers. New York: American National Standards Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Berg BG. Analysis of weights in multiple observation tasks. J Acoust Soc Am. 1989;86:1743–1746. doi: 10.1121/1.399962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss E. The effect of masker level uncertainty on intensity discrimination. J Acoust Soc Am. 2007 doi: 10.1121/1.2812578. accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty KA, Lutfi RA. Level discrimination of single tones in a multitone complex by normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners. J Acoust Soc Am. 1999;105:1831–1840. doi: 10.1121/1.426742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlach NI, Mason CR, Kidd G, Jr, Arbogast TL, Colburn HS, Shinn-Cunningham BG. Note on informational masking. J Acoust Soc Am. 2003;113:2984–2987. doi: 10.1121/1.1570435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye RH, Jr, Yost WA, Stellmack MA, Sheft S. Stimulus classification procedure for assessing the extent to which binaural processing is spectrally analytic or synthetic. J Acoust Soc Am. 1994;96:2720–2730. doi: 10.1121/1.411278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellermeier W. Detectability of increments and decrements in spectral profiles. J Acoust Soc Am. 1996;99:3119–3125. [Google Scholar]

- Fantini DA, Moore BC. A comparison of the effectiveness of across-channel cues available in comodulation masking release and profile analysis tasks. J Acoust Soc Am. 1994;96:3451–3462. doi: 10.1121/1.411451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Mason CR. Auditory profile analysis: frequency, phase, and Weber’s law. J Acoust Soc Am. 1985;77:1155–1161. doi: 10.1121/1.392179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd G, Jr, Mason CR, Deliwala PS, Woods WS, Colburn HS. Reducing informational masking by sound segregation. J Acoust Soc Am. 1994;95:3475–3480. doi: 10.1121/1.410023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd G, Jr, Mason CR, Green DM. Auditory profile analysis of irregular sound spectra. J Acoust Soc Am. 1986;79:1045–1053. doi: 10.1121/1.393376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt H. Transformed up-down methods in psychoacoustics. J Acoust Soc Am. 1971;49:467–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutfi RA, Kistler DJ, Callahan MR, Wightman FL. Psychometric functions for informational masking. J Acoust Soc Am. 2003;114:3273–3282. doi: 10.1121/1.1629303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BC, Glasberg BR, Baer T. A model for the prediction of thresholds, loudness and partial loudness. J Audio Eng Soc. 1997;45:224–240. [Google Scholar]

- Neff DL, Callaghan BP. Effective properties of multicomponent simultaneous maskers under conditions of uncertainty. J Acoust Soc Am. 1988;83:1833–1838. doi: 10.1121/1.396518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff DL, Dethlefs TM. Individual differences in simultaneous masking with random-frequency, multicomponent maskers. J Acoust Soc Am. 1995;98:125–134. doi: 10.1121/1.413748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff DL, Odgaard EC. Sample discrimination of frequency differences with distracters. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;116:3051–3061. doi: 10.1121/1.1802571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh EL, Lutfi RA. Nonmonotonicity of informational masking. J Acoust Soc Am. 1998;104:3489–3499. doi: 10.1121/1.423932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellmack MA, Willihnganz MS, Wightman FL, Lutfi RA. Spectral weights in level discrimination by preschool children: analytic listening conditions. J Acoust Soc Am. 1997;101:2811–2821. doi: 10.1121/1.419479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viemeister NF. Intensity discrimination of pulsed sinusoids: the effects of filtered noise. J Acoust Soc Am. 1972;51:1265–1269. doi: 10.1121/1.1912970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]