Abstract

Rather than being a passive, haphazard process of wear and tear, lifespan can be modulated actively by components of the insulin/insulin-like growth factor I (IGFI) pathway in laboratory animals. Complete or partial loss-of-function mutations in genes encoding components of the insulin/IGFI pathway result in extension of life span in yeasts, worms, flies, and mice. This remarkable conservation throughout evolution suggests that altered signaling in this pathway may also influence human lifespan. On the other hand, evolutionary tradeoffs predict that the laboratory findings may not be relevant to human populations, because of the high fitness cost during early life. Here, we studied the biochemical, phenotypic, and genetic variations in a cohort of Ashkenazi Jewish centenarians, their offspring, and offspring-matched controls and demonstrated a gender-specific increase in serum IGFI associated with a smaller stature in female offspring of centenarians. Sequence analysis of the IGF1 and IGF1 receptor (IGF1R) genes of female centenarians showed overrepresentation of heterozygous mutations in the IGF1R gene among centenarians relative to controls that are associated with high serum IGFI levels and reduced activity of the IGFIR as measured in transformed lymphocytes. Thus, genetic alterations in the human IGF1R that result in altered IGF signaling pathway confer an increase in susceptibility to human longevity, suggesting a role of this pathway in modulation of human lifespan.

Keywords: IGF1 receptor, human longevity, genetic variation

The role of reduced insulin/insulin-like growth factor I (IGFI) signaling in lifespan extension is well established in invertebrates (1). During evolution, the insulin/IGFI pathways have diverged from a single receptor in invertebrates to multiple receptors and more complicated pathways and regulatory networks in mammals (2). Insulin regulates metabolic pathways, whereas IGFI and growth hormone (GH), the main regulator of circulating IGFI, control growth and differentiation (3). In mice, knockout models of the insulin receptor (IR) pathway have a negative impact on lifespan and age-related diseases (4). In contrast, both spontaneous and targeted genetic disruptions of the GH/IGF pathway are associated with small size (dwarfism), numerous indices of delayed aging, enhanced stress resistance, and a major increase in lifespan (5), suggesting a role for the GH/IGF pathway in murine longevity. Furthermore, caloric restriction, the measure linked to life extension and retardation of aging-related pathology, is also associated with reduced circulating IGFI levels (6). On the other hand, reduced levels of IGFI in humans, while protective against cancer, constitute a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and diabetes (7). Moreover, human aging is associated with a decline in the levels of GH and IGFI, and it has been proposed that GH therapy may reverse some of the physiological features of aging (8). Therefore, at the current time, the role of IGF signaling in human longevity is far from clear.

Despite the substantial parallels between the insulin/IGFI axis in invertebrates and mammals in laboratory settings, the importance of this regulatory network for exceptional longevity in human populations is uncertain, especially because living to 100 years of age is a rare phenotype in humans with a prevalence of 1 in 10,000 individuals in the general population (9). Even if we adopt the premise that the basic mechanisms that modulate longevity and determine the rate of aging are common to all multicellular organisms, it is possible that the observed effects on longevity of candidate gene variants will prove to be exclusively associated with laboratory strains and may have fitness cost (10, 11). Thus, it remains to be demonstrated whether candidate loci with major effects on longevity in model organisms such as genes involved in the insulin/IGFI pathway will show segregating allelic variation in human populations.

Previous studies in humans have reported on levels of IGFI and related molecules in the oldest old (12); however, interpreting these values was difficult because of the lack of adequate controls. To overcome this shortcoming, we established a unique cohort of individuals with exceptional longevity and their offspring (approximate age 70 years) and age- and sex-matched controls without a family history of unusual longevity; all of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. This group of offspring of individuals with exceptional longevity and their matched controls is a powerful tool for identifying genetically controlled longevity traits and led to the identification of longevity phenotypes such as lipoprotein sizes and the subsequent discovery of corresponding longevity genotypes (13, 14). Here, we report the use of this unique cohort to identify partial loss-of-function mutations in the IGF1 receptor (IGF1R) gene that are overrepresented among centenarians compared with controls, suggesting a role for the IGF signaling pathway in human longevity.

Results

Height and IGFI Levels in the Offspring of Centenarians.

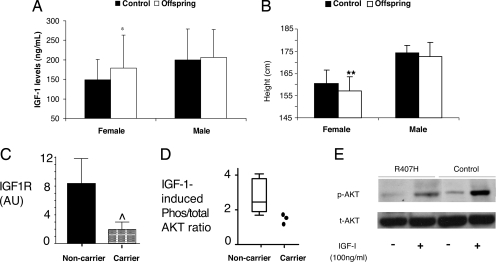

Because plasma levels of IGFI in centenarians do not reflect their levels at a younger age, we compared the levels of IGFI in offspring of centenarians to controls without a family history of longevity to identify a potential alteration in the IGF signaling pathway, which may contribute to exceptional longevity. Remarkably, female offspring (n = 105) showed 35% higher serum IGFI levels (P < 0.01) compared with female controls (n = 67), suggesting a possible alteration in the GH/IGF pathway in the longevity of females (Fig. 1A). This phenomenon was gender-specific, as IGFI levels in male offspring (n = 92) and male controls (n = 42) were identical (Fig. 1A). To distinguish whether the high IGFI is caused by increased production or is a result of IGF insensitivity, we assessed maximal reported height, a necessary parameter because of the height shrinkage that occurs in the elderly. Female offspring were 2.5 cm shorter compared with controls (P < 0.001), whereas the height of males was identical in offspring and controls (Fig. 1B). Thus, a likely explanation for this finding is that the higher IGFI levels represent a compensatory response to reduced IGFIR signaling, which would also be associated with a small decrease in maximal height, (although a less bioactive IGFI molecule is also a possibility). Remarkably, this combination of a female-specific effect on longevity, higher IGFI levels, with a small reduction in auxological growth, is highly reminiscent of a report on female mutant mice haploinsufficient for the IGFIR, which display nearly identical features, including gender-specific lifespan extension (15).

Fig. 1.

Phenotypes and chemotypes of the IGF system in the centenarian cohort. (A) Female offspring of centenarians (n = 105) have higher serum IGFI levels compared with age-matched female controls without a family history of unusual longevity (n = 67). IGFI levels in male offspring (n = 92) and male controls (n = 42) were identical. IGFI levels in serum were measured by ELISA (*, P < 0.01). Results are reported as mean ± SD. (B) Female offspring are shorter than controls as measured by maximal reported height (**, P < 0.001). Results are reported as mean ± SD. (C) Immortalized lymphocytes from the female centenarians carrying mutations (Carrier) in IGF1R (Ala-37–Thr, Arg-407–His, and Thr-470–Thr) show significant reductions in IGFIR levels compared with immortalized lymphocytes from female centenarians with no mutations (Noncarrier, n = 10) as measured by ELISA (⋀, P < 0.03). (D) IGF signaling is defective in the IGF1R mutation carriers (Carrier) of female centenarians as compared with female centenarians with no mutations (Noncarrier, n = 10) as measured by immunoblot analysis of the ratio of phosphorylated to total AKT in response to IGFI treatment in immortalized lymphocytes. (E) A representative immunoblot for total and phosphorylated AKT in immortalized lymphocytes from a centenarian carrying the Arg-407–His mutation and a control centenarian without the mutation.

Screening of the IGF1 and IGF1R Genes for Mutations Associated with Longevity.

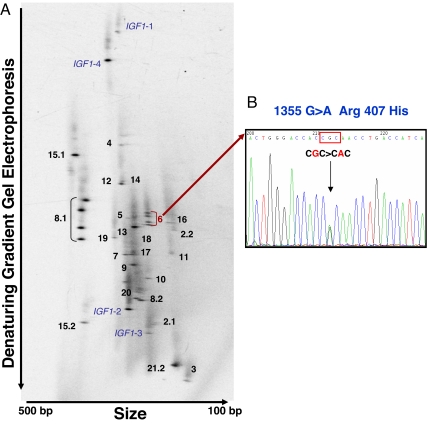

We comprehensively screened genomic DNA from a subset of female centenarians with heights below the mean for that population (n = 79) and female controls (n = 161) for all possible genetic variations throughout the coding exons and splice junctions of the IGF1 and IGF1R genes by using 2D gene scanning and DNA sequencing (Fig. 2). Remarkably, we did not find a single variation in the IGF1 gene, suggesting that the coding regions of this gene are highly conserved. In contrast, the IGF1R gene was highly polymorphic with a total of 20 sequence variants, among which 9 were previously unknown, novel variants that were not reported in the various SNP databases (Table 1). Five SNPs of the nine novel variants were in a coding region. Interestingly, two nonsynonymous mutations, i.e., 244G>A (Ala-37–Thr) and 1355G>A (Arg-407–His), and two novel synonymous mutations, i.e., 1545G>A (Thr-470–Thr) and 4103C>T (Arg-1323–Arg), were found in centenarians with short stature and elevated IGFI that were not seen in controls. The overrepresentation of the two nonsynonymous mutations among centenarians compared with controls was statistically significant (P = 0.04). Genotyping of the offspring of the centenarian mutation carriers shows that none of the offspring harbor these rare mutations.

Fig. 2.

2D gene scanning of human IGF1 and IGF1R genes. The entire coding regions and exon–intron junctions of the IGF1 and IGF1R genes were amplified by two-step PCR. Thirty short PCR fragments were distributed in 2D gels according to their size and melting temperature. (A) A 2D gene scanning pattern from a centenarian subject with the fragment identification number and a hetero-duplex band in exon 8.1 and exon 6 of the IGF1Rgene is shown. (B) The novel genetic variation in exon 6 was identified as 1355G>A (Arg-407–His) by nucleotide sequencing.

Table 1.

IGF1R variants in centenarians and controls

| Category | Nucleotide change | Protein change | Centenarians, n = 79 |

Control, n = 161 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Het | Hom | Het | Hom | |||

| Nonsynonymous | 244G>A | Ala-37–Thr | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1355G>A | Arg-407–His | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Synonymous | 948C>A | Gly-271–Gly | 7 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| 1545G>A | Thr-470–Thr | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1959C>T | Asn-608–Asn | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 1995G>T | Arg-620–Arg | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2343C>T | Thr-736–Thr | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| 2745C>T | Asn-870–Asn | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| 3174G>A | Glu-013–Glu | 48 | 20 | 67 | 29 | |

| 4083C>T | Tyr-1316–Tyr | 5 | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

| 4103C>T | Arg-1323–Arg | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Intronic | IVS2+20C>T | 42 | 8 | 65 | 12 | |

| IVS8–20T>C | 49 | 13 | 67 | 34 | ||

| IVS13+17G>A | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||

| IVS13+21A>C | 47 | 3 | 62 | 41 | ||

| IVS13+29_30delGT | 26 | 1 | 38 | 3 | ||

| IVS15+49insG | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| IVS15+52A>G | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| IVS17−5C>T | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||

| IVS21–34G>A | 46 | 15 | 59 | 42 | ||

Het, number of heterozygote carriers of variant; Hom, number of homozygote carriers of variant. Previously unknown, novel variants are indicated in bold.

Genotyping the IGF1R Mutations in the Entire Cohort.

We genotyped the entire cohort (384 centenarians and 312 controls) for the presence of the two nonsynonymous mutations, i.e., 244G>A (Ala-37–Thr) and 1355G>A (Arg-407–His). We found nine centenarians (2.3%) who carried either the Ala-37–Thr (n = 2) or Arg-407–His (n = 7) mutation, whereas only one control (0.3%) was found to be a carrier of the Arg-407–His mutation and no control carried the Ala-37–Thr mutation. These results indicate that the nonsynonymous mutations were significantly more common in centenarians compared with controls (P = 0.02). Of the nine centenarian carriers, IGFI levels and height were available for six carriers. When we compared the mutation carriers (n = 6, 66% female) vs. noncarriers (n = 163, 67% female) among centenarians, the mutation carriers had significantly higher IGFI levels (165 ± 21 vs. 121 ± 6 ng/ml, P = 0.04) than noncarriers after adjustment for gender and age (Table 2). Although the mutation carriers were slightly shorter (162 ± 2.8 vs. 165 ± 0.8 cm, P = 0.41) than noncarriers, this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Height and IGFI levels among centenarian carriers of either the Ala-37–Thr or the Arg-407–His mutation in the IGF1R gene

| Variable | Carriers, n = 6 | Noncarriers, n = 163 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height, cm | 162 ± 2.8 | 165 ± 0.8 | 0.41 |

| IGFI, ng/ml | 165 ± 21 | 121 ± 6 | 0.04 |

Functional Studies of the Nonsynonymous Mutations Associated with Longevity.

To assess the functional impact of the mutations identified in centenarians, we analyzed immortalized lymphocytes from centenarians by using an IGFIR ELISA. Immortalized lymphocytes from the two nonsynonymous, 244G>A (Ala-37–Thr) and 1355G>A (Arg-407–His), and one synonymous, 1545G>A (Thr-470–Thr), mutation carriers of female centenarians showed a significant reduction in IGFIR levels compared with lymphocytes from 10 female centenarians without the mutations (P < 0.03) (Fig. 1C). Moreover, when treated with IGFI, lymphocytes from the centenarian mutation carriers demonstrated reduced phosphorylation of AKT compared with the centenarian noncarriers (Fig. 1 D and E), suggesting that these mutations lead to decreases in IGF signaling.

Discussion

Despite the well established role of the GH/IGF axis in modulation of lifespan in laboratory animals, its role in human longevity has been controversial. The identification of new nonsynonymous mutations in the IGF1R gene that result in reduced IGF signaling among centenarians suggests a similar role for this pathway in modulation of human lifespan as observed in model organisms. The centenarians with the IGF1R mutations display manifestations of elevated serum IGFI levels and a trend toward smaller height, reminiscent of the phenotypes observed in mice haploinsufficient for the IGF1R with extended lifespan (15). The centenarian mutation carriers were on average 2.5 cm shorter than nonmutation carriers, but this difference was not statistically significant (Table 2), suggesting that the impact of these mutations on height is limited, probably because of compensation via increased IGFI levels and/or other mechanisms. In contrast, female offspring exhibited significantly higher serum IGFI and shorter stature, possibly because of variations in other genes involved in the IGF axis that may be more common than the IGF1R mutations described here. Comprehensive analysis of all genes within this axis will be required to firmly establish a role of the IGFI axis in modulation of human longevity.

The IGF1 gene is a strong genetic determinant of body size and serum level of IGFI across mammals (16–18). In dogs, the IGF1 promotor has been shown to be the most potent determinant of size (17), and IGFI levels in dogs are associated with lifespan (19). Severe short stature and extremely high IGFI levels were observed in a family with a mutation in the IGF1 gene, leading to an altered protein sequence associated with a decreased affinity to the IGFIR (20). Interestingly, in our Ashkenazi Jewish population, the coding region of the IGF1 gene was found to be remarkably free of any genetic variation, suggesting the possibility of selective pressure being exerted on this gene.

In contrast, we identified a diverse set of genetic alterations in the IGF1R gene in this population. Of particular interest is the enrichment of the variations in the coding region, especially the nonsynonymous mutations in centenarians compared with the control population, suggesting a contribution of multiple rare alleles leading to a major phenotypic effect on human longevity in the general population (21). So far, only a few nonsynonymous IGF1R mutations have been reported from patients with severe phenotypes such as intrauterine growth retardation (20, 22). The prevalence of such nonsynonymous mutations in the normal population has been obscure because of the relatively low number of control individuals studied in previous reports (n < 100). Resequencing of the IGF1R gene in the Centre d'Étude du Polymorphisme Humain cohort indicated that the Arg-407–His variation (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_ss.cgi?subsnp_id=46533818) was indeed very rare, heterozygocity being detected in only one individual from a total of 354 individuals. Together with our data, these results clearly demonstrate the rarity of nonsynonymous mutations among the normal population and, more importantly, its enrichment among long-lived humans.

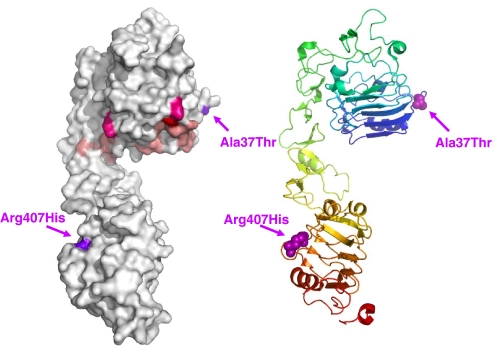

One of the two nonsynonymous mutations we identified in the IGF1R, Ala-37–Thr, is located at the edge of one of the putative ligand binding hot spots of the IGFIR extracellular domain in the L1 region (23). Our modeling using the crystal structure of the L1-CR1-L2 fragments of the IGFIR structure (24) shows that Ala-37 is positioned on a loop in the first L1 domain near residues that, when mutated, reduce the binding affinity of IGFI for IGFIR by 2- to 10-fold (Fig. 3, residues in pale pink) or >20-fold (Fig. 3, Phe-90 in red). A recently identified compound heterozygote missense mutation (22), Arg-108–Gln and Lys-115–Asn, from a patient with intrauterine and postnatal growth retardation with features of IGF resistance is also located in this region of L1 (Fig. 3, residues in hot pink). These results suggest that the Ala-37–Thr change may affect ligand binding but to a lesser extent than the mutations that are within the IGF binding pocket. This region also coincides with residues 34–44 of the IR that are shown to be important for insulin binding (25). Alignment of IGFIR with the IR shows that Ala-37 is just one residue away from IR Phe-39, a residue important for insulin ligand specificity (26). Ala-37 is also adjacent to a highly conserved stretch of residues beginning with Glu-44, which has important function for insulin/IR binding (27). Interestingly, IGFIR residues around Ala-37 are highly conserved among distant vertebrate species, indicating that sequence variants most probably affect function.

Fig. 3.

The position of mutated amino acids in the IGFIR. The locations of the mutated amino acids are indicated in the crystallographic structure encompassing the first three domains of the IGFIR (L1-CR-L2 fragment) (24). Color-coded residues are those when mutated reduce the binding affinity of IGFI for IGFIR by 2- to 10-fold (pale pink) or >20-fold (red) (23) or a compound heterozygote missense mutations (hot pink) from a patient with intrauterine and postnatal growth retardation (22). Arrows indicate the locations of the mutated amino acids identified in centenarians.

Another mutation found in our screen, Arg-407–His, is located in the region of the L2 domain where nonsynonymous mutations display defective proreceptor processing and transport to the plasma membrane without reduction in ligand affinity (28). Our finding of a reduction in IGFIR levels and concomitant attenuation of IGFI-induced AKT phosphorylation in the lymphocyte of the Arg-407–His carrier suggest that this mutation also inhibits IGFIR protein activity. Mutations in the close vicinity of this residue in IR are known to contribute to insulin-resistant diabetes (29, 30). Moreover, close to Arg-407 is the DAF-2 mutation Ala-580–Thr (e1365) that leads to dauer formation at 25°C (31). Finally, it is tempting to speculate that the altered IGF signaling induced by the synonymous mutation, 1545G>A (Thr-470–Thr), may be caused by the reduction of IGFIR levels, as demonstrated in the lymphocytes from the centenarian carrier, possibly resulting from the allele-specific differences in mRNA splicing, processing, or translational control and regulation (32).

This article provides strong evidence that the IGF1R can be a genetic determinant of human longevity. The role of GH/IGF pathway in human longevity is controversial because of the recognized evolutionary tradeoffs in the modulation of lifespan. Our findings suggest that “IGF-related longevity genes” do exist in human populations. Although these data suggest that such alterations occur in a low frequency in human centenarians, more exhaustive studies will clarify whether longevity assuring genetic factors and related phenotypes exist for other components of the GH/IGF pathway. Indeed, our results suggest that centenarians may harbor individually rare, but collectively more common, genetic variations in genes encoding components of the GH/IGF signaling pathway. Additional comprehensive studies in the centenarians and their offspring may reveal other molecules within the GH/IGF pathway that are operative in human longevity.

Materials and Methods

Population and Sample Collection.

In a case control study, Ashkenazi Jews were recruited as described (13, 14, 33). This population derived from an undetermined small number (estimated to be several thousands) of founders. External factors, including ecclesiastical edicts prohibiting all social contact with Jews, the Crusades, the establishment of the Pale of Settlement, numerous Pogroms, and ethnic bigotry resulted in the social isolation and inbreeding of the Ashkenazi Jews (34). Three hundred and eighty four probands with exceptional longevity [286 females and 98 males, average age 97.7 (0.2) years (mean SE), age range 95–108 years; 20% over the age of 100] were recruited to participate in the study. The participants' ages were defined by birth certificates or dates of birth as stated on passports. Probands were required to be living independently at 95 years of age as a reflection of good health, although at the time of recruitment they could be at any institution or level of dependency. In addition, probands had to have a first-degree offspring who was willing to participate in the study. The offspring group consisted of 114 females and 174 males [mean age 67.8 (0.46) years (mean SE), range 49–88 years]. We further established a unique cohort of Ashkenazi Jewish descent without a family history of unusual longevity (approximate age 70 years) that served as controls [n = 312, mean age 79.5 (0.4) years (mean SE), 57% female]. A research nurse visited the probands in the morning to draw a venous blood sample, obtain a medical history including maximal height and weight, measure height and weight, and perform a physical examination. Health histories were obtained by using a standardized questionnaire. In such visits, the offspring (and participating spouses) underwent similar evaluations as described (13, 14, 33). All blood samples were rapidly processed at the General Clinical Research Center at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine for generation of transformed lymphocytes as a source of DNA and immediate freezing of serum. Informed written consent was obtained in accordance with the policy of the Committee on Clinical Investigations of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Mutation Screening of IGF1 and IGF1R.

We screened genomic DNA isolated from blood of centenarians and controls to discover all possible genetic variations in the full coding sequence and intron/exon boundaries of the IGF1 and IGF1R genes by 2D gene scanning (35). To increase specificity, PCR amplification was designed in two steps. First, two multiplex long-distance PCR coamplified 12 large fragments encompassing coding and splicing junction regions of IGF1 and IGF1R. These products served as template for four multiplex short PCRs to amplify all target regions in 30 fragments (5 fragments for IGF1 and 25 fragments for IGF1R). Primers are listed in supporting information (SI) Table 3. The mixture of amplicons after heteroduplexing was then separated on the basis of size and melting temperature in a 2D gel. DNA fragments containing heterozygous sequence variation were then reamplified from the genomic DNA and sequenced to identify position and nature of sequence variation.

Assays for IGFI, IGFIR, and Phospho-AKT.

IGFI was measured in uniformly handled serum aliquots by using an ELISA Kit from DSL according to the manufacturer's recommendations. IGFIR was measured in immortalized lymphocyte cell extracts with an ELISA Immunoassay Kit from BioSource International according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Lymphocytes were isolated and immortalized as described (36). To assess the ability of IGFI to activate signal transduction via the IGFIR, lymphocytes from female centenarians harboring mutations and those without were incubated with or without IGFI (100 ng/ml) for 25 min after which total cell protein was extracted and 150 μg of cell lysates was subjected to SDS/PAGE, immunoblotting with total and phospho-AKT antibodies from Cell Signaling, and densitometry using scanning autoradiography. Results are reported as means ± SD and as box and whiskers plots. Statistical significance was determined by using unpaired t tests.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health P01AG 027734, AG024391, and AG023292.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0705467105/DC1.

References

- 1.Kenyon C. Cell. 2005;120:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenyon C. Cell. 2001;105:165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupont J, LeRoith D. Horm Res. 2001;55(Suppl 2):22–26. doi: 10.1159/000063469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LeRoith D, Gavrilova O. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:904–912. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonkowski MS, Rocha JS, Masternak MM, Al Regaiey KA, Bartke A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7901–7905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600161103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartke A. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3718–3723. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang J, Anzo M, Cohen P. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:867–872. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vance ML. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:779–780. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp020186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perls T, Bochen K, Freeman M, Alpert L, Silver M. Age Ageing. 1999;28:193–197. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenkins NL, McColl G, Lithgow GJ. Proc Biol Soc. 2004;271:2523–2526. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker DW, McColl G, Jenkins NL, Harris J, Lithgow GJ. Nature. 2000;405:296–297. doi: 10.1038/35012693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Heemst D, Beekman M, Mooijaart SP, Heijmans BT, Brandt BW, Zwaan BJ, Slagboom PE, Westendorp RG. Aging Cell. 2005;4:79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2005.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atzmon G, Rincon M, Schechter CB, Shuldiner AR, Lipton RB, Bergman A, Barzilai N. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barzilai N, Atzmon G, Schechter C, Schaefer EJ, Cupples AL, Lipton R, Cheng S, Shuldiner AR. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290:2030–2040. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holzenberger M, Dupont J, Ducos B, Leneuve P, Geloen A, Even PC, Cervera P, Le Bouc Y. Nature. 2003;421:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature01298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker J, Liu JP, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Cell. 1993;75:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutter NB, Bustamante CD, Chase K, Gray MM, Zhao K, Zhu L, Padhukasahasram B, Karlins E, Davis S, Jones PG, et al. Science. 2007;316:112–115. doi: 10.1126/science.1137045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woods KA, Camacho-Hubner C, Savage MO, Clark AJ. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1363–1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610313351805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greer KA, Canterberry SC, Murphy KE. Res Vet Sci. 2007;82:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walenkamp MJ, Karperien M, Pereira AM, Hilhorst-Hofstee Y., van Doorn J, Chen JW, Mohan S, Denley A, Forbes B, van Duyvenvoorde HA, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2855–2864. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen JC, Kiss RS, Pertsemlidis A, Marcel YL, McPherson R, Hobbs HH. Science. 2004;305:869–872. doi: 10.1126/science.1099870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abuzzahab MJ, Schneider A, Goddard A, Grigorescu F, Lautier C, Keller E, Kiess W, Klammt J, Kratzsch J, Osgood D, et al. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2211–2222. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whittaker J, Groth AV, Mynarcik DC, Pluzek L, Gadsboll VL, Whittaker LJ. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43980–43986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102863200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrett TP, McKern NM, Lou M, Frenkel MJ, Bentley JD, Lovrec GO, Elleman TC, Cosgrove LJ, Ward CW. Nature. 1998;394:395–399. doi: 10.1038/28668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams PF, Mynarcik DC, Yu GQ, Whittaker J. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3012–3016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kjeldsen T, Wiberg FC, Andersen AS. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32942–32946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mynarcik DC, Williams PF, Schaffer L, Yu GQ, Whittaker J. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18650–18655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor SI, Accili D, Haft CR, Hone J, Imai Y, Levy-Toledano R, Quon MJ, Suzuki Y, Wertheimer E. Acta Pediatr Suppl. 1994;399:95–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roach P, Zick Y, Formisano P, Accili D, Taylor SI, Gorden P. Diabetes. 1994;43:1096–1102. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.9.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Vorm ER, Kuipers A, Kielkopf-Renner S, Krans HM, Moller W, Maassen JA. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14297–14302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimura KD, Tissenbaum HA, Liu Y, Ruvkun G. Science. 1997;277:942–946. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Oh JM, Kim IW, Sauna ZE, Calcagno AM, Ambudkar SV, Gottesman MM. Science. 2007;315:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.1135308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atzmon G, Schechter C, Greiner W, Davidson D, Rennert G, Barzilai N. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:274–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Descamps O, Hondekijn JC, Van Acker P, Deslypere JP, Heller FR. Clin Genet. 1997;51:303–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1997.tb02478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGrath SB, Bounpheng M, Torres L, Calavetta M, Scott CB, Suh Y, Rines D, van Orsouw N, Vijg J. Genomics. 2001;78:83–90. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Louie LG, King MC. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:637–638. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.