Abstract

FOXO is thought to function as a repressor of growth that is, in turn, inhibited by insulin signaling. However, inactivating mutations in Drosophila melanogaster FOXO result in viable flies of normal size, which raises a question over the involvement of FOXO in growth regulation. Previously, a growth-suppressive role for FOXO under conditions of increased target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway activity was described. Here, we further characterize this phenomenon. We show that tuberous sclerosis complex 1 mutations cause increased FOXO levels, resulting in elevated expression of FOXO-regulated genes, some of which are known to antagonize growth-promoting pathways. Analogous transcriptional changes are observed in mammalian cells, which implies that FOXO attenuates TOR-driven growth in diverse species.

Introduction

The target of rapamycin (TOR) and insulin signaling pathways control cell growth, proliferation, and metabolism throughout organism development and adult homeostasis. The TOR pathway is an ancient signaling network conserved from yeast to humans that responds to environmental stimuli, such as nutrient and oxygen availability, as well as growth factor signaling (for reviews see Oldham and Hafen, 2003; Wullschleger et al., 2006). The insulin pathway evolved in metazoans to enable dynamic control of cell growth, proliferation, and metabolism in a systemic fashion. Multiple points of crosstalk exist between the insulin and TOR pathways, which ensure optimal activity of each pathway and hence allow adjustment to dynamic environmental and dietary conditions. For example, in response to hyperactivation of the TOR pathway by conditions such as high levels of amino acids, glucose, or free fatty acids or, genetically, by mutation of tuberous sclerosis complex (Tsc)1 or Tsc2, insulin signaling is suppressed (for review see Manning, 2004). Altered activity of multiple components of the insulin and TOR pathways, such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase, Akt, PTEN, TSC1, and TSC2 contribute to an array of human cancers (for reviews see Luo et al., 2003; Inoki et al., 2005).

Akt is an important insulin pathway protein that promotes cell growth, proliferation, and survival by phosphorylating multiple effector proteins, including the TOR pathway inhibitor TSC2 and FOXO family transcription factors (for reviews see Manning, 2004; Greer and Brunet, 2005; Wullschleger et al., 2006). FOXO transcription factors have well-defined roles in insulin-dependent control of longevity and metabolism as well as stress resistance (for reviews see Greer and Brunet, 2005; Kenyon, 2005). These proteins have also been implicated in insulin-dependent control of tissue growth but their role in this process is more controversial. FOXO proteins have been shown to restrict tumor formation in mice (Paik et al., 2007). Surprisingly, Drosophila melanogaster mutants for the gene encoding the sole FOXO family transcription factor develop normally and are of normal size, which brings into question the role of FOXO in the developmental regulation of growth under normal circumstances (Junger et al., 2003).

FOXO has been shown to attenuate growth of D. melanogaster tissues with elevated TOR pathway activity (Junger et al., 2003). Here, we further characterize this phenomenon by showing that Tsc1 mutations cause increased FOXO levels, resulting in elevated expression of FOXO-regulated genes, some of which are known to antagonize growth-promoting pathways. In addition we show that this FOXO-dependent transcriptional response is conserved in mammals.

Results and discussion

Genes encoding growth inhibitors are elevated in Tsc1 tissue

To investigate mechanisms by which the TOR pathway controls tissue growth, we analyzed transcriptional profiles of tissue lacking Tsc1, which leads to hyperactivation of the TOR pathway and excessive growth (Gao and Pan, 2001; Potter et al., 2001; Tapon et al., 2001). Eye-antennal imaginal discs from third instar D. melanogaster larvae were generated that were composed almost entirely of tissue derived from one of two different genotypes: Tsc1 or wild-type isogenic control. Three biologically independent first strand cDNA samples from each genotype were hybridized to Affymetrix microarray chips. Expression levels of 157 genes were elevated 1.5-fold or more, whereas 211 genes were repressed 1.5-fold or more (P < 0.05) when compared with control tissue. These genes have been implicated in diverse cellular functions including metabolism, membrane transport, stress response, cell growth, and cell structure (Figs. 1 and S1 and Tables S1 and S2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200710100/DC1).

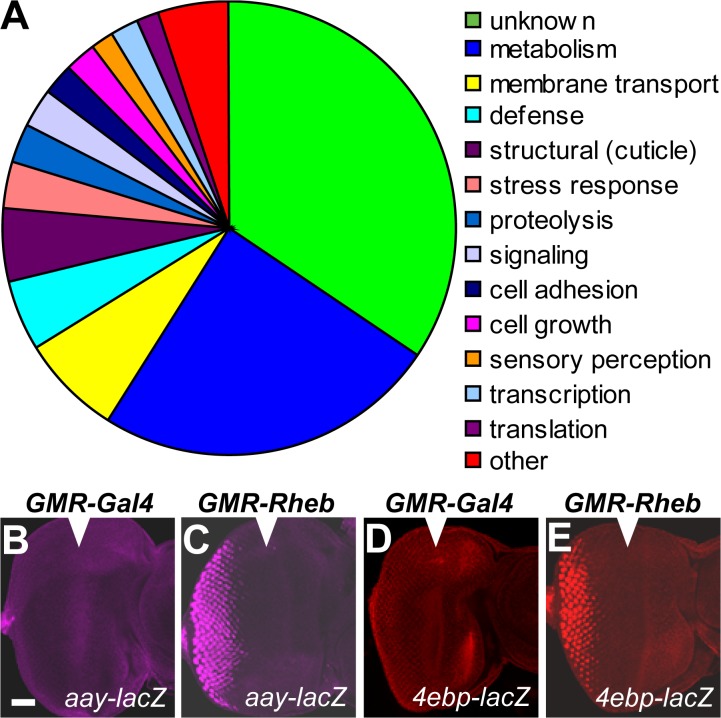

Figure 1.

Genes elevated in developing Tsc1 eye-antennal tissue. (A) Transcriptional changes observed in Tsc1 eye-antennal imaginal discs grouped by proposed biological function. Included are genes whose expression was elevated at least 1.5-fold (P < 0.05) in Tsc1 tissue compared with the wild type. (B–E) Third instar larval eye imaginal discs; anterior is shown on the right. Arrowheads indicate the morphogenetic furrow. Activity of aay (B and C) and 4e-bp (D and E) enhancer trap lines in tissue misexpressing Gal4 (B and D) or Rheb (C and E) under control of the GMR promoter. Bar, 50 μM.

Observed transcriptional changes were validated for several genes using D. melanogaster gene-enhancer trap lines (Fig. 1, B–E), and quantitative real-time PCR (QPCR; Fig. S2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200710100/DC1). The UAS–Gal4 system was used to activate the TOR pathway in a specific tissue domain by driving expression of Rheb under the control of the glass multiple reporter (GMR) promoter. Induction of astray (aay) and 4E-BP (both of which were found to be elevated in Tsc1 tissue by microarray analysis) were observed in the GMR expression domain (posterior to the morphogenetic furrow) when Rheb was misexpressed but were not induced when the negative control Gal4 gene was misexpressed (Fig. 1, B–E). QPCR was also used to confirm expression changes observed in Tsc1 tissue for charybdis (chrb), scylla (scy), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxy kinase, 4E-BP, and aay (Fig. S2).

Intriguingly, several gene products whose expression was elevated in Tsc1 tissue have been implicated in tissue growth controlled by the insulin and TOR pathways, including 4E-BP, Chrb, and Scy (Miron et al., 2001; Reiling and Hafen, 2004). 4E-BP is a repressor of cap-dependent translation. Upon phosphorylation by TOR, 4E-BP dissociates from eIF4e, allowing assembly of the initiation complex at the mRNA cap structure, ribosome recruitment, and subsequent translation (for review see Wullschleger et al., 2006). Scy and Chrb, and their mammalian orthologues REDD1 and REDD2, inhibit insulin and TOR signaling in response to hypoxia and energy stress and restrict growth during D. melanogaster development (Brugarolas et al., 2004; Reiling and Hafen, 2004; Sofer et al., 2005). Our finding that inhibitors of growth are highly expressed in Tsc1 tissue led us to hypothesize that such genes are transcriptionally induced as part of a feedback loop that restricts tissue growth under conditions of excessive TOR activity. Feedback loops are an important activity-modulating feature of many signaling pathways, including the TOR and insulin pathways (for review see Manning, 2004).

Tsc1 loss-of-function (LOF) and FOXO gain-of-function (GOF) transcription profiles are overlapping

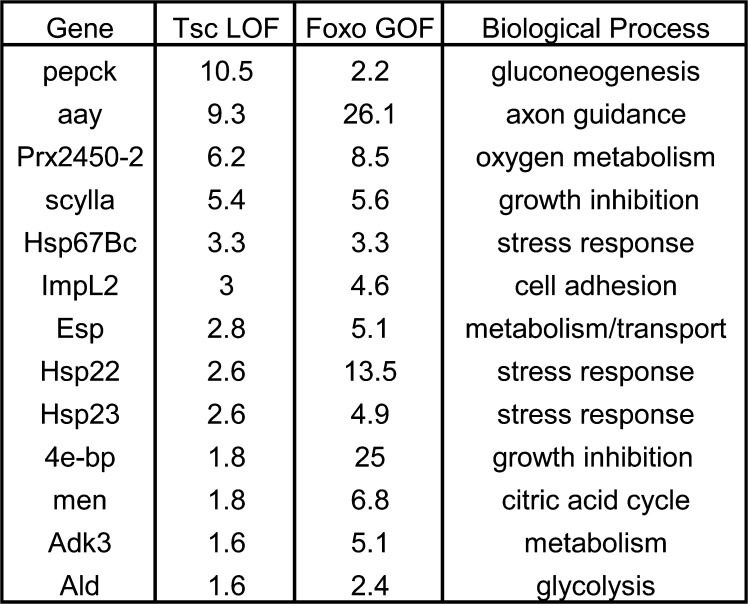

To examine the mechanism whereby transcription of growth inhibitors is induced in response to TOR hyperactivation, we sought to determine which transcription factors were responsible for their expression. One obvious candidate was FOXO, a member of the forkhead transcription factor family, which has a well-established role as an effector of insulin signaling (for review see Greer and Brunet, 2005). If FOXO has a role in inducing expression of negative regulators of growth in Tsc tissue, then expression of some of those genes should be elevated under conditions of increased FOXO activity. To investigate this hypothesis, we compared the expression profiles of Tsc1 LOF tissue and D. melanogaster S2 cells expressing FOXOA3, a mutant version of FOXO that is insensitive to phosphorylation-dependent inhibition by Akt (FOXO GOF; Puig et al., 2003; Gershman et al., 2007). This analysis revealed that 25 genes were up-regulated 1.5-fold or greater in both Tsc1 LOF and FOXO GOF expression profiles, which represents a highly significant degree of overlap (P = 4.9 × 10e−009) as determined by calculation of the hypergeometric distribution. This highly statistically significant P value strongly suggests that there is a functional overlap between these two datasets that cannot be explained by random variation. Genes that were elevated at least 1.5-fold (P < 0.05) in both Tsc1 LOF and FOXO GOF cells and that have been assigned to certain cellular functions are shown in Fig. 2. Interestingly, two genes previously implicated in tissue growth regulated by the insulin and TOR pathways 4E-BP and scy were elevated in both microarray experiments, whereas the chrb growth-inhibiting gene was not (Fig. 2). Thus, a subset of genes elevated in Tsc1 tissue appears to respond to FOXO activity and was investigated further.

Figure 2.

Common transcriptional changes in Tsc1 tissue and cells misexpressing FOXO. Genes elevated at least 1.5-fold (P < 0.05) in both Tsc1 eye-antennal disc tissue and S2 cells misexpressing activated FOXO. Genes with a proposed biological function are listed as well as their expression level as determined by microarray analysis in each experimental condition.

FOXO activates transcription of genes whose expression is elevated in Tsc1 tissue

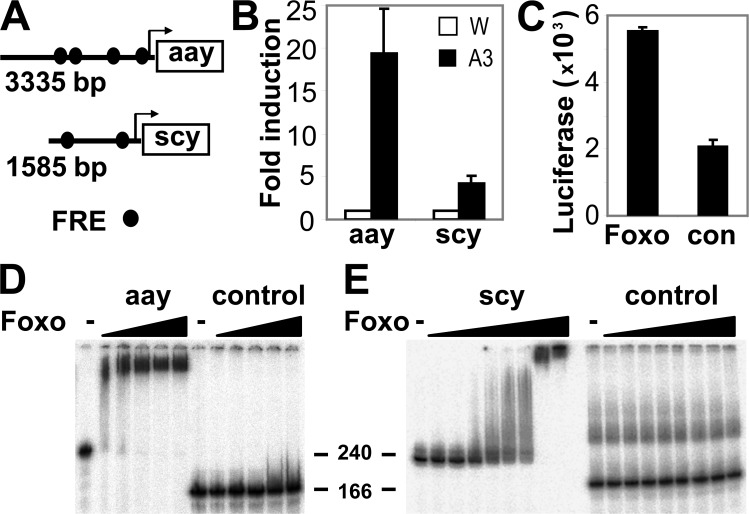

4E-BP is a well-characterized FOXO target gene (Junger et al., 2003; Puig et al., 2003). To determine whether FOXO could directly activate transcription of genes that were elevated in Tsc1 tissue other than 4E-BP, we focused on scy and the phosphoserine phosphatase aay (one of the most highly elevated transcripts in each microarray experiment). scy and aay both possess consensus FOXO recognition elements (FREs) in their promoters comparable to those found in dInR and 4E-BP promoters (Furuyama et al., 2000; Puig et al., 2003). Therefore, we examined whether these genes are bona fide FOXO targets by measuring their expression in D. melanogaster S2 cells misexpressing FOXOA3 in the presence of insulin (Puig et al., 2003). aay and scy mRNAs were up-regulated 19.4- and 4.3-fold, respectively, relative to a control gene, actin, as determined by QPCR (Fig. 3 B). Next, we used luciferase reporter assays in S2 cells to determine whether the aay promoter region containing putative FREs was sensitive to FOXO activity. As shown in Fig. 3 C, luciferase activity dependent on the aay promoter was strongly induced by FOXOA3 relative to a negative control. In addition, using in vitro band shift assays, we demonstrated that FOXO directly bound to the aay promoter (Fig. 3 D), which indicates that FOXO likely activates expression of aay by directly binding to the FRE. Surprisingly, in parallel luciferase reporter assays, we could not demonstrate activation of the scy promoter by FOXO, despite the fact that we observed strong binding of FOXO to the putative scy FRE using in vitro band-shift assays (Fig. 3 E). A possible explanation is that our scy–promoter construct lacked the minimal promoter elements required for transcription of luciferase.

Figure 3.

FOXO can directly induce expression of genes elevated in Tsc1 tissue. (A) Schematic representation of FREs in aay and scy promoters. (B) QPCR analysis of aay and scy mRNA in S2 cells transfected with wild-type FOXO (W) or FOXO GOF (A3) in the presence of insulin (n = 3). (C) Luciferase assay (n = 4) measuring transcriptional activity of the aay promoter in S2 cells expressing either vector alone (con) or FOXOA3 (FOXO). (D and E) Band shift assays examining the ability of increasing amounts of FOXO to complex with the aay promoter (D), scy promoter (E), or negative control DNA fragments. DNA markers are indicated in bp. Error bars in B and C represent standard deviation.

FOXO protein is elevated and active in Tsc1 tissue

TOR pathway hyperactivation caused by Tsc deficiency has been shown to strongly repress activity of Akt (Radimerski et al., 2002). FOXO is normally inactivated by Akt-dependent phosphorylation, which restricts nuclear entry of FOXO and leads to its ubiquitin-dependent destruction (for review see Greer and Brunet, 2005). Therefore, in response to TOR pathway hyperactivation, we predicted that reduced Akt activity would cause FOXO protein to accumulate. To examine this hypothesis, we analyzed expression of FOXO protein in mosaic Tsc1 imaginal discs. We found that FOXO protein was markedly increased in Tsc1 clones when compared with neighboring wild-type tissue (Fig. 4, A and B). In addition, FOXO protein appeared to be mostly nuclear in Tsc1 tissue and cytoplasmic in wild-type tissue (Fig. S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200710100/DC1). Consistent with this observation, nuclear localization of the mouse FOXO orthologue FOXO1 was observed in endothelial cells of Tsc2 mutant hemangiomas, whereas FOXO1 was mostly cytoplasmic in normal cells (Manning et al., 2005). FOXO mRNA levels were unchanged in Tsc1 tissue as determined by microarray analysis, which suggests that changes in translation or stability of FOXO protein account for its accumulation in Tsc1 tissue. The presence of increased FOXO protein in the nuclei of Tsc1 cells is consistent with our hypothesis that FOXO is responsible for increased expression of some of the growth inhibitors that are up-regulated in Tsc1 cells.

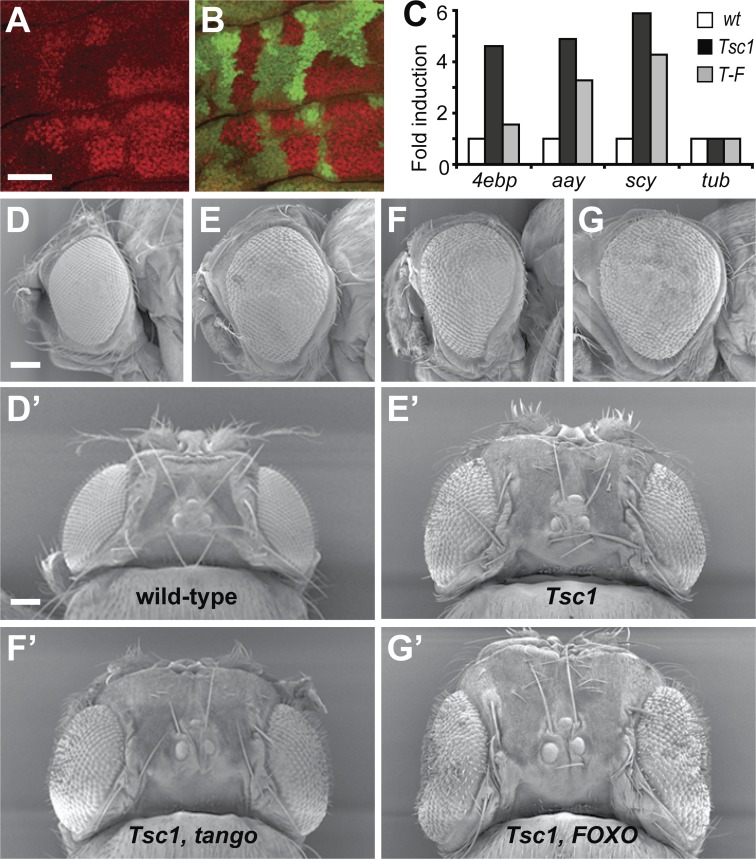

Figure 4.

FOXO is elevated in Tsc1 tissue and inhibits growth of Tsc1 organs. (A and B) Confocal microscope images of a Tsc1 mosaic wing imaginal disc. FOXO expression (red in A and in the merged image shown in B) was elevated in Tsc1 clones when compared with wild-type tissue, which expresses GFP (green in B). (C) QPCR analysis of 4e-bp, aay, and scy mRNAs normalized to a tubulin (tub) control mRNA in eye-antennal imaginal disc tissue of several genotypes: wild-type (wt), Tsc1, or Tsc1-FOXO (T-F). (D–G) Scanning electron micrographs of adult eyes of genotypes: wild type(D and D′), Tsc1 (E and E′), Tsc1-tgo (F and F′), and Tsc1-FOXO (G and G'). Data are represented as a mean expression level derived from between three and nine replicate experiments performed on pooled biological samples collected from at least 20 animals of each genotype. However, n was still equal to 1. Therefore, data were averaged to provide mean expression data but did not allow measurement of error values such as standard deviation or standard error of the mean. Bars: (A and B) 50 μM; (D–G) 100 μM.

To determine whether FOXO was necessary for transcriptional induction of genes that were elevated in Tsc1 tissue, we used QPCR analysis to measure 4E-BP, aay, and scy expression in Tsc1 and Tsc1-FOXO double mutant eye-antennal imaginal discs. Consistent with our microarray analysis, we observed increased expression of 4E-BP, aay, and scy in Tsc1 tissue (Fig. 4 C). In Tsc1-FOXO tissue, however, 4E-BP was expressed at approximately equivalent amounts as in wild-type tissue, whereas aay and scy expression was only partially reduced (Fig. 4 C). This demonstrates that elevated expression of 4E-BP in Tsc1 tissue is dependent on the FOXO transcription factor and provides evidence that FOXO activity increases when the TOR pathway is hyperactivated. Expression of aay and scy appear to be partially dependent on FOXO but are likely stimulated by additional transcription factors in Tsc1 tissue.

FOXO but not hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) inhibits growth in Tsc1-deficient tissues

Next, we sought to determine whether FOXO was required to limit growth of tissues with increased TOR pathway activity. In addition, we analyzed a potential role for another transcription factor, HIF-1, for retardation of TOR-driven growth. HIF-1 is a dual-subunit transcription factor consisting of α and β subunits that functions in response to insulin/TOR signaling (Treins et al., 2002; Dekanty et al., 2005) and drives transcription of the growth-inhibiting genes scy and chrb (Reiling and Hafen, 2004), both of which we found to be elevated in Tsc1 tissue.

D. melanogaster possesses several HIF-1α subunits and a sole HIF-1β subunit, tango (tgo), which partners with each HIF-1α subunit. If FOXO and/or HIF-1 are required to induce expression of genes that limit tissue growth when the TOR pathway is hyperactivated, one might predict that Tsc1-FOXO and/or Tsc1-tgo double mutant tissue would possess a greater capacity to grow than Tsc1 tissue alone. To test this hypothesis, we examined the size of D. melanogaster eyes comprised almost entirely of the following genotypes: control, tgo, FOXO, Tsc1, Tsc1-tgo, and Tsc1-FOXO. Mutant eyes were created by driving mitotic recombination of chromosomes bearing flipase recognition target (FRT) sites and the appropriate gene mutations, specifically in developing D. melanogaster eye-antennal imaginal discs. Eyes lacking either tgo or FOXO were approximately the same size as control eyes (not depicted), whereas Tsc1 eyes were considerably larger (Fig. 4, D and E). Tsc1-tgo double mutant eyes did not exhibit a further increase in size, which suggests that HIF-1 is not required to inhibit tissue growth in response to Tsc1 loss (Fig. 4 F). In contrast, Tsc1-FOXO double mutant eyes were substantially larger than Tsc1 eyes, which is consistent with a previous study (Fig. 4 G; Junger et al., 2003). This finding is particularly significant in light of the finding that eyes lacking FOXO were indistinguishable in size from wild-type eyes (unpublished data; Junger et al., 2003). Thus, it appears that FOXO is normally dispensable for control of eye size, but when growth control is altered by virtue of increased TOR activity, FOXO partially offsets the increased tissue growth. These findings are consistent with our observations that FOXO protein accumulates in Tsc1 tissue and that transcriptional profiles of FOXO GOF and Tsc1 LOF cells overlap significantly.

Transcriptional changes in cells with increased TOR activity are conserved in eukaryotes

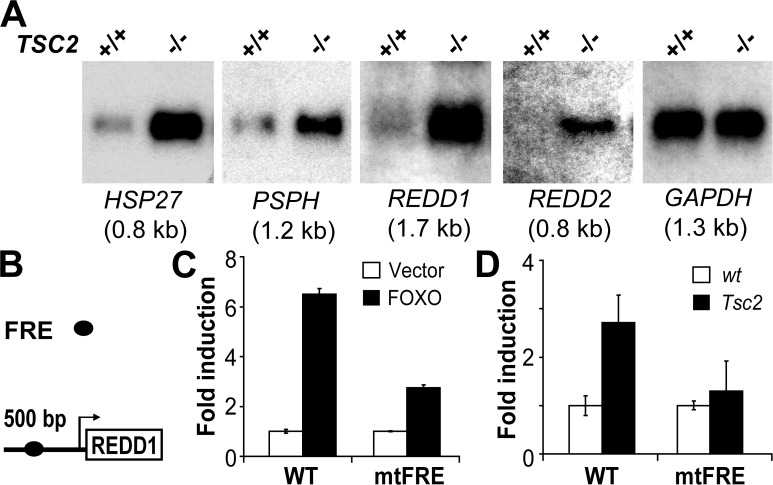

Because individual components of the insulin and TOR pathways are highly conserved among eukaryotes, important regulatory mechanisms that control tissue growth via these pathways are also likely to be conserved. To investigate this idea, we analyzed transcriptional control of mouse orthologues of genes that were elevated in D. melanogaster Tsc1 tissue. Initially, we performed Northern blotting analysis on Tsc2 primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs; derived on a p53 background to overcome premature senescence induced by Tsc2 loss; Zhang et al., 2003). It is reasonable to predict that transcriptional changes that occur because of loss of either Tsc1 or Tsc2 should be very similar because TSC1 and TSC2 function together in an obligate fashion, and mutation of either gene leads to almost indistinguishable phenotypes (Tapon et al., 2001). We found that several gene expression changes observed in D. melanogaster Tsc1 tissue were conserved in Tsc2 MEFs (Fig. 5 A). The homologues of aay, heat shock protein (hsp) 23, scy, and chrb (PSPH, hsp 27, REDD1, and REDD2, respectively) were all significantly up-regulated in Tsc2 MEFs when compared with control MEFs and expression of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) control. To demonstrate that these expression changes were a specific consequence of Tsc2 loss, we reconstituted Tsc2 expression in Tsc2 null cells, which substantially suppressed mammalian TOR activity and expression of these genes (unpublished data). Interestingly, expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxy kinase and 4E-BP1/2 was not altered between wild-type and Tsc2 cells (unpublished data), which might reflect tissue- or species-specific differences in the transcriptome of D. melanogaster epithelial cells and MEFs.

Figure 5.

TOR pathway–driven transcriptional changes are conserved in eukaryotes. (A) Northern analysis of the hsp27, PSPH, REDD1, REDD2, and GAPDH genes in primary Tsc2 (−/−) or wild-type littermate control (+/+) MEFs. (B) Schematic representation of the FRE in the REDD1 promoter. (C) Luciferase assay (n = 4) measuring transcriptional activity of either wild-type (WT) or FRE mutant (mtFRE) REDD1 promoters in primary MEFs expressing either vector alone (Vector) or FOXO GOF (FOXO). (D) Transcriptional activity of the REDD1 wild type or FRE mutant promoter in wild-type (wt) or Tsc2 MEFs (n = 6). Error bars represent standard deviation.

To determine whether the mode of transcription of these genes was also conserved in mammals, we analyzed expression of the scy homologue REDD1. Like scy, mammalian REDD1 orthologues possess a putative consensus FRE within their proximal promoters (Furuyama et al., 2000). Cotransfection of a version of FOXO that is insensitive to phosphorylation-dependent inhibition by Akt (TM-FKHRL-1) induced robust activation of a mouse REDD1 reporter construct in primary MEFs (Fig. 5 C). To determine whether induction was mediated through the identified FRE, we created a mutant reporter lacking this sequence. Deletion of the REDD1 FRE consistently reduced FOXO-mediated induction of the REDD1 promoter (Fig. 5 C). Finally, to directly assess whether FOXO-dependent transcription was activated in mammalian cells lacking Tsc2, we examined activity of the REDD1 promoter reporter or the corresponding mutant FRE reporter in wild-type and Tsc2 MEFs. As predicted, the wild-type REDD1 promoter exhibited robust activation in Tsc2 cells compared with wild-type cells, and this activation was substantially reduced by deletion of the FRE (Fig. 5 D). Together, these findings provide evidence that transcriptional changes resulting from Tsc1/Tsc2 deficiency are conserved in diverse species.

Here, we report identification of an evolutionary conserved transcriptional program important for restricting tissue overgrowth driven by excessive activation of the TOR pathway. The FOXO transcription factor plays a key role in this transcriptional response, likely by stimulating expression of several growth inhibitory genes. Thus, although the requirement for FOXO in restricting growth under normal development conditions appears dispensable, this is no longer the case under conditions of excessive TOR activation. These findings have important implications for cancer syndromes that arise because of inappropriate TOR pathway activation, such as the human hamartomatous syndrome, tuberous sclerosis. TOR-dependent feedback inhibition is thought to contribute to the benign nature of Tsc1 and Tsc2 tumors (Ma et al., 2005; Manning et al., 2005). Conceivably, inactivating mutations in FOXO family transcription factors and/or FOXO target genes that possess growth-inhibiting properties could promote further growth in normally benign Tsc1 and Tsc2 tumors.

Materials and methods

D. melanogaster stocks

The following stocks were used: w; FRT82B, w; FRT82B Tsc1Q87X (Tapon et al., 2001), w; FRT82B FOXO25 (provided by E. Hafen, Institute of Molecular Systems Biology, Zürich, Switzerland; Junger et al., 2003), w; FRT82B Tsc1Q87X, FOXO25 (generated by meiotic recombination), w; FRT82B tgo5 (provided by S. Crews, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC; Emmons et al., 1999), w; FRT82B Tsc1Q87X, tgo5 (generated by meiotic recombination), y w eyFlp; FRT82B P[W+] l(3)cl-R3, y w hsFlp; FRT82B P(W + ubi-GFP), y w; P(lacW)aay, y w; P(lacW)Thor, UAS-Rheb (provided by P. Patel, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; Patel et al., 2003), and GMR-Gal4.

Microarray hybridization and analysis

Male flies of genotype w; FRT82B or w; FRT82B Tsc1Q87X were crossed to y w eyFlp; FRT82B P(W+) l(3)cl-R3. Larval progeny from these crosses bore eye discs comprised almost entirely of one genotype (either wild-type or Tsc1). Eye-antennal discs from third instar larvae of each genotype were dissected (200 eye discs per sample in three independent samples) and total RNA was prepared using TRIZOL (Invitrogen). First strand cDNA was generated and hybridized to GeneChip Drosophila genome arrays (Affymetrix) by the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center microarray core. Data were analyzed using Microarray Suite 5.0 (Affymetrix). Nine pairwise comparisons were performed between wild-type and Tsc1 samples to calculate mean fold changes. Excel (Microsoft) was used to perform a t test to calculate significant changes (P < 0.05) in gene expression levels. FOXO GOF microarray experiments have been described previously (Puig et al., 2003; Gershman et al., 2007). Overlap between Tsc1 LOF and FOXO GOF microarrays was performed using Excel (Microsoft). Measurement of significance of overlap between microarrays was determined using hypergeometric distribution calculation.

Immunohistochemistry and microscopy

Antibodies used were anti-FOXO (Puig et al., 2003), anti–β-galactosidase (Sigma-Aldrich), and anti–mouse and anti–rabbit Alexa fluor secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). The nuclear dye used was Topro-3 (Invitrogen). Confocal microscopy was performed on a confocal microscope (SP2) using software (both from Leica). Images were captured using a 20× NA 0.5 lens or a 40× NA 1.25 oil immersion lens (both from Leica) at room temperature. Scanning electron microscopy was performed according to standard protocols using a field emission scanning electron microscope (XL30 FEG; Philips; Bennett and Harvey, 2006). Any brightness or contrast adjustments were performed using Photoshop (Adobe).

Northern analysis

Total RNA was prepared from primary litter-matched wild-type or TSC2 MEFs (provided by D. Kwiatkowski, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA) using RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test Inc.). 15 μg RNA per lane was loaded and probed with the indicated 32P-labeled cDNA probes as described previously (Sofer et al., 2005). Probes were isolated by RT-PCR from embryonic day 9.5 mouse embryo RNA.

QPCR

RNA was extracted from third instar larval eye imaginal discs or S2 cells using TRIZOL, and first strand cDNA was produced with a Superscript II kit (Invitrogen). QPCR reactions were analyzed on a sequence detection system (ABI Prism 7000; Applied Biosystems) using SYBR green reagents. Relative levels of mRNA were compared by the comparative CT method using tubulin or actin primers to normalize total mRNA input.

Luciferase assays

aay promoter assays were performed using a 3.3-kb aay promoter fragment directly upstream of the transcription start site. S2 cells were transfected with an aay–reporter construct and either FOXOA3 or an empty vector control, and harvested 24 h later. REDD1 promoter assays used a 0.6-kb fragment containing the proximal REDD1 promoter and first exon (Ellisen et al., 2002). FRE mutant REDD1 promoters were generated by PCR. Reporter constructs or luciferase controls were transfected with TM-FKHRL1 (provided by M. Greenberg, Children's Hospital, Boston, MA) into primary MEFs and luciferase activity was measured at 36 h. Luciferase assays were analyzed using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega).

Band-shift assays

Band-shift assays were performed as described previously (Puig et al., 2003) using a 241-bp aay promoter fragment starting 1,213 bp upstream of the predicted transcription start site and a 236-bp scy promoter fragment starting 391 bp upstream of the predicted transcription start site.

Online supplemental material

Figs. S1–S3 provide data on expression changes observed between wild-type and Tsc1 D. melanogaster larval eye-antennal imaginal discs. Fig. S1 is an accompanying figure to Fig. 1 A and represents a gene ontology analysis of genes whose expression was decreased at least 1.5-fold (P < 0.05) in Tsc1 tissue compared with wild-type tissue as determined by microarray analysis. Fig. S2 shows selected genes whose expression changes between Tsc1 and wild-type tissue were confirmed by QPCR. Fig. S3 shows high-magnification images of FOXO subcellular localization in Tsc1 mosaic larval imaginal discs. Tables S1 and S2 list all genes whose expression was increased or decreased at least 1.5-fold (P < 0.05) in Tsc1 compared with wild-type tissue as determined by microarray analysis. Online supplemental materials is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200710100/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Crews, M. Greenberg, E. Hafen, D. Kwiatkowski, P. Patel, N. Tapon, and the Bloomington Stock Centre for Drosophila stocks and reagents, and T. Shioda and the MGH Cancer Center for microarray hybridizations.

K.F. Harvey is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Special Fellow (grant 3324-06) and the recipient of a Career Development Award from the International Human Frontier Science Program Organization. Support was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council (grant 400335 to K. Harvey), a National Institutes of Health grant (GM61672 to I.K. Hariharan), the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Finnish Diabetes Association (all to O. Puig), and an American Cancer Society grant (DDC-105895 to L.W. Ellisen).

Abbreviations used in this paper: chrb, charybdis; FRE, FOXO recognition element; FRT, flipase recognition target; GMR, glass multiple reporter; GOF, gain of function; HIF-1, hypoxia-inducible factor-1; hsp, heat shock protein; LOF, loss of function; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; QPCR, quantitative real-time PCR; scy, scylla; tgo, tango; TOR, target of rapamycin; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex.

References

- Bennett, F.C., and K.F. Harvey. 2006. Fat cadherin modulates organ size in Drosophila via the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling pathway. Curr. Biol. 16:2101–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas, J., K. Lei, R.L. Hurley, B.D. Manning, J.H. Reiling, E. Hafen, L.A. Witters, L.W. Ellisen, and W.G. Kaelin Jr. 2004. Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev. 18:2893–2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekanty, A., S. Lavista-Llanos, M. Irisarri, S. Oldham, and P. Wappner. 2005. The insulin-PI3K/TOR pathway induces a HIF-dependent transcriptional response in Drosophila by promoting nuclear localization of HIF-alpha/Sima. J. Cell Sci. 118:5431–5441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellisen, L.W., K.D. Ramsayer, C.M. Johannessen, A. Yang, H. Beppu, K. Minda, J.D. Oliner, F. McKeon, and D.A. Haber. 2002. REDD1, a developmentally regulated transcriptional target of p63 and p53, links p63 to regulation of reactive oxygen species. Mol. Cell. 10:995–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, R.B., D. Duncan, P.A. Estes, P. Kiefel, J.T. Mosher, M. Sonnenfeld, M.P. Ward, I. Duncan, and S.T. Crews. 1999. The spineless-aristapedia and tango bHLH-PAS proteins interact to control antennal and tarsal development in Drosophila. Development. 126:3937–3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuyama, T., T. Nakazawa, I. Nakano, and N. Mori. 2000. Identification of the differential distribution patterns of mRNAs and consensus binding sequences for mouse DAF-16 homologues. Biochem. J. 349:629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X., and D. Pan. 2001. TSC1 and TSC2 tumor suppressors antagonize insulin signaling in cell growth. Genes Dev. 15:1383–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershman, B., O. Puig, L. Hang, R.M. Peitzsch, M. Tatar, and R.S. Garofalo. 2007. High-resolution dynamics of the transcriptional response to nutrition in Drosophila: a key role for dFOXO. Physiol. Genomics. 29:24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer, E.L., and A. Brunet. 2005. FOXO transcription factors at the interface between longevity and tumor suppression. Oncogene. 24:7410–7425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki, K., M.N. Corradetti, and K.L. Guan. 2005. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat. Genet. 37:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junger, M.A., F. Rintelen, H. Stocker, J.D. Wasserman, M. Vegh, T. Radimerski, M.E. Greenberg, and E. Hafen. 2003. The Drosophila forkhead transcription factor FOXO mediates the reduction in cell number associated with reduced insulin signaling. J. Biol. 2:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, C. 2005. The plasticity of aging: insights from long-lived mutants. Cell. 120:449–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J., B.D. Manning, and L.C. Cantley. 2003. Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell. 4:257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L., J. Teruya-Feldstein, N. Behrendt, Z. Chen, T. Noda, O. Hino, C. Cordon-Cardo, and P.P. Pandolfi. 2005. Genetic analysis of Pten and Tsc2 functional interactions in the mouse reveals asymmetrical haploinsufficiency in tumor suppression. Genes Dev. 19:1779–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning, B.D. 2004. Balancing Akt with S6K: implications for both metabolic diseases and tumorigenesis. J. Cell Biol. 167:399–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning, B.D., M.N. Logsdon, A.I. Lipovsky, D. Abbott, D.J. Kwiatkowski, and L.C. Cantley. 2005. Feedback inhibition of Akt signaling limits the growth of tumors lacking Tsc2. Genes Dev. 19:1773–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron, M., J. Verdu, P.E. Lachance, M.J. Birnbaum, P.F. Lasko, and N. Sonenberg. 2001. The translational inhibitor 4E-BP is an effector of PI(3)K/Akt signalling and cell growth in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, S., and E. Hafen. 2003. Insulin/IGF and target of rapamycin signaling: a TOR de force in growth control. Trends Cell Biol. 13:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik, J.H., R. Kollipara, G. Chu, H. Ji, Y. Xiao, Z. Ding, L. Miao, Z. Tothova, J.W. Horner, D.R. Carrasco, et al. 2007. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell. 128:309–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, P.H., N. Thapar, L. Guo, M. Martinez, J. Maris, C.L. Gau, J.A. Lengyel, and F. Tamanoi. 2003. Drosophila Rheb GTPase is required for cell cycle progression and cell growth. J. Cell Sci. 116:3601–3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter, C.J., H. Huang, and T. Xu. 2001. Drosophila Tsc1 functions with Tsc2 to antagonize insulin signaling in regulating cell growth, cell proliferation, and organ size. Cell. 105:357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig, O., M.T. Marr, M.L. Ruhf, and R. Tjian. 2003. Control of cell number by Drosophila FOXO: downstream and feedback regulation of the insulin receptor pathway. Genes Dev. 17:2006–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radimerski, T., J. Montagne, M. Hemmings-Mieszczak, and G. Thomas. 2002. Lethality of Drosophila lacking TSC tumor suppressor function rescued by reducing dS6K signaling. Genes Dev. 16:2627–2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiling, J.H., and E. Hafen. 2004. The hypoxia-induced paralogs Scylla and Charybdis inhibit growth by down-regulating S6K activity upstream of TSC in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 18:2879–2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofer, A., K. Lei, C.M. Johannessen, and L.W. Ellisen. 2005. Regulation of mTOR and cell growth in response to energy stress by REDD1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:5834–5845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapon, N., N. Ito, B.J. Dickson, J.E. Treisman, and I.K. Hariharan. 2001. The Drosophila tuberous sclerosis complex gene homologs restrict cell growth and cell proliferation. Cell. 105:345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treins, C., S. Giorgetti-Peraldi, J. Murdaca, G.L. Semenza, and E. Van Obberghen. 2002. Insulin stimulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/target of rapamycin-dependent signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 277:27975–27981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger, S., R. Loewith, and M.N. Hall. 2006. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 124:471–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H., G. Cicchetti, H. Onda, H.B. Koon, K. Asrican, N. Bajraszewski, F. Vazquez, C.L. Carpenter, and D.J. Kwiatkowski. 2003. Loss of Tsc1/Tsc2 activates mTOR and disrupts PI3K-Akt signaling through downregulation of PDGFR. J. Clin. Invest. 112:1223–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.