Abstract

There are many biological steps between viral infection of CD4+ T cells and the production of HIV-1 virions. Here we incorporate an eclipse phase, representing the stage in which infected T cells have not started to produce new virus, into a simple HIV-1 model. Model calculations suggest that the quicker infected T cells progress from the eclipse stage to the productively infected stage, the more likely that a viral strain will persist. Long-term treatment effectiveness of antiretroviral drugs is often hindered by the frequent emergence of drug resistant virus during therapy. We link drug resistance to both the rate of progression of the eclipse phase and the rate of viral production of the resistant strain, and explore how the resistant strain could evolve to maximize its within-host viral fitness. We obtained the optimal progression rate and the optimal viral production rate, which maximize the fitness of a drug resistant strain in the presence of drugs. We show that the window of opportunity for invasion of drug resistant strains is widened for a higher level of drug efficacy provided that the treatment is not potent enough to eradicate both the sensitive and resistant virus.

Keywords: HIV-1, Drug resistance, Viral fitness, Mathematical model, Viral dynamics

1 Introduction

Mathematical models have proven valuable in the understanding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) dynamics, disease progression and antiretroviral responses (see reviews in [38, 39, 41, 42]). Many important insights into the host-pathogen interaction in HIV-1 infection have been derived from mathematical modeling and analyses of changes in the level of HIV-1 RNA in plasma when antiretroviral drugs are administered to perturb the equilibrium between viral production and viral clearance in infected individuals [22, 43, 44, 58].

In a basic HIV model that has been frequently used to describe virus infection, there are three variables: uninfected CD4+ T cells, productively infected T cells, and free virus [38, 43]. In this model, infected cells were assumed to produce new virions immediately after target cells were infected by a free virus. However, there are many biological processes between viral infection and subsequent production within a cell. For example, after viral entry into the host cell, the viral RNA genome is reverse transcribed into a complementary DNA sequence by the enzyme reverse transcriptase (RT). The DNA copy of the viral genome is then imported into the nucleus and integrated into the genome of the lymphocyte. When the infected lymphocyte is activated, the viral genome is transcribed back into RNA. These RNAs are translated into proteins that require a viral protease to cleave them into active forms. Finally, the mature proteins assemble with the viral RNA to produce new virus particles that bud from the cell. The portion of the viral life cycle before production of virions is called the eclipse phase. Several mathematical models have been developed that either introduce a constant (discrete) delay [11, 14, 21, 34] to denote the eclipse phase, or assume that the time delay is approximated by some distribution functions (e.g., a gamma distribution) [30, 35]. The introduction of a time delay in models of HIV-1 primary infection to analyze the viral load decay under antiretroviral therapy has refined the estimates of important kinetic parameters, such as the viral clearance rate and the mortality rate of productively infected cells [34, 35]. Some more complex models, including age-structured models, have been employed to study virus dynamics [33] and the influence of drug therapy on the evolution of HIV-1 [26, 50].

It should be noted that the above-mentioned age-structured models essentially treat the transition of a cell from the uninfected state to the productively infected state as a deterministic process by taking into account the time delay that occurs between various steps in the virus life cycle within a target cell. In contrast, in this study we incorporate an eclipse stage to describe the stage of an infected cell between viral attachment and generation of new virus. The present stage-structured model implicitly treats the progression of an infected cell from the initial infection to subsequent reproduction as an exponentially distributed process. We have chosen to adopt the stage-structured approach because it allows us to explore mechanistically biological trade-offs between protein functions and drug resistance while avoiding the complications of time delay models.

The advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has been an important breakthrough in HIV-1 treatment, resulting in a great reduction in the morbidity and mortality associated with HIV infection [52]. However, the clinical benefits of combination therapy are often compromised by the frequent emergence of drug resistance driven by the within-host selective pressure of antiretroviral drugs [7]. In addition, the persistence of viral reservoirs, including latently infected resting memory CD4+ T cells that show minimal decay even in patients on HAART up to many years [6, 17, 60], has been a major obstacle to the long-term control or eradication of HIV-1 in infected individuals.

Drug resistance results from mutations that emerge in the viral proteins targeted by antiretroviral agents. Most of our knowledge regarding resistance comes from the genotypic analysis of virus isolates from patients receiving prolonged drug treatment [28]. Important insights into the mechanisms underlying the evolution of drug resistant viral strains have also been derived from mathematical modeling of virus dynamics and antiretroviral responses [3, 27, 37, 48, 49, 56]. Both deterministic and stochastic modeling approaches suggest that treatment failure is mostly likely due to the preexistence of drug resistant strains before the initiation of therapy rather than the generation of resistant virus during the course of treatment [3, 48]. The evolution of HIV resistance is associated with selective pressures exerted by drug treatments that are not potent enough to completely suppress the viral replication. The longer the drug efficacy remains in the intermediate range, the greater the possibility that drug resistant virus variants will arise during therapy [32]. Nonetheless, the conditions of mutant selection are very complex in treated patients due to time-dependent intracellular drug concentrations in vivo [14, 24] and spatial heterogeneity [25]. The management of such patients requires a careful understanding of the mechanistic evolution of HIV-1 variants during treatment.

The evolution of resistant strains in the presence of drugs is thought to depend on inherent trade-offs that exist between the proper functioning of HIV's reverse transcriptase and protease enzymes and their reduced susceptibility to antiretroviral regimens in their mutated forms. Indirect evidence for such trade-offs is found in the observation that there is a reduction in replication capacity for drug resistant virus variants in the absence of drug therapy [8, 36]. These trade-offs not only help explain that even after drug resistance arises viral load often remains partially suppressed below pre-therapy levels but also could be potentially exploited in order to better manage the evolution of drug resistance within a patient.

The main purpose of this study is to develop a mathematical framework that can be used to formalize and examine simple hypotheses about the life-history trade-offs that allow drug-resistant viral strains within a patient to persist in the presence of drug therapy. We incorporate the eclipse phase of viral replication into a mathematical model to characterize the stage during which infected CD4+ T cells have not yet started to produce new virus. The inclusion of the progression of infected cells from this eclipse phase to the productive stage enables us to capture more variability in HIV dynamics. We observe that the strain of virus with a faster progression rate essentially has a quicker process of reverse transcription of RNA into DNA and integration of the DNA into the chromosome, which gives rise to an increased chance for that viral strain to persist. More importantly, our approach allows us to link drug resistance to reverse transcriptase inhibitors to the progression of the eclipse phase and identify the optimal evolutionary strategy for the drug resistant strain under some simple assumptions. It is widely believed that most HIV drug resistance mutations affect highly conserved amino acid residues that are thought to be important for optimal enzyme functions, and thus for the full replicative potential of virus [8]. Consequently, we assume that in the absence of drug therapy the wild-type strain will evolve to replicate as fast as possible and produce as many new virions as possible. Thus, a viral strain with a slower progression rate, which is operating suboptimally, will possibly have a higher level of resistance to antiretroviral drugs, creating a trade-off between the progression rate and the drug efficacy of reverse transcriptase inhibitors. In addition, there are trade-offs between the viral production rate and the clearance rate of productively infected cells [12], and between the viral production rate and the drug efficacy of protease inhibitors (see the last section for more discussions). We will investigate how these trade-offs may affect the fitness of drug-resistant viral strains in the presence of drugs at different concentration levels. The optimal progression rate and the optimal viral production rate are derived by maximizing the viral fitness of drug-resistant strains. An invasion criterion of resistant strains is also obtained in the presence of drug therapy. Both analytical results and numerical simulations suggest that with a more effective drug treatment (yet not potent enough to eradicate the virus), a wider range of drug-resistant strains will be able to invade in response to the selective pressure of drugs.

2 Model formulation

A basic mathematical model has been widely adopted to describe the virus dynamics of HIV-1 infection in vivo (see [43] and reviews in [38, 39, 41]). Important features of the interaction between virus particles and cells have been determined by fitting the model to experimental data. In this paper, we extend the basic model by including a class of infected cells that are not yet producing virus and two viral strains to study the evolution of drug resistant strains.

2.1 Inclusion of cells in the eclipse phase

After a virus enters a target CD4+ T cell, there are a number of biological events before the production of new virions: reverse transcription from viral RNA to DNA, integration of the DNA copy into the DNA of the infected cell (the integrated viral DNA is called the provirus), transcription of the provirus and translation to generate viral polypeptides, cleavage of polypeptides by the HIV protease, assembly and budding of new virus. Perelson et al. [40] examined a model for the interaction of HIV with CD4+ T cells that considers a class of infected T cells, which contain the provirus but are not producing virus. In this work, we begin with a modification of the model in [40], and then incorporate antiretroviral effects to study the evolution of drug resistance.

As suggested in [63], when a virus enters a resting CD4+ T cell, the viral RNA may not be completely reverse transcribed into DNA. If the cell is activated shortly following infection, reverse transcription can proceed to completion. However, the unintegrated virus harbored in resting cells may decay with time and partial DNA transcripts are labile and degrade quickly [64]. Hence a proportion of resting infected cells can revert to the uninfected state before the viral genome is integrated into the genome of the lymphocyte [15]. To model these events, we include a class of infected cells in the eclipse stage of viral replication, i.e., the stage between the initial infection and subsequent viral production. Thus, a portion of infected cells in the eclipse phase can revert to the uninfected class. Let T(t), , T*(t) and V(t) denote the concentrations of uninfected CD4+ T cells, infected cells in the eclipse stage, productively infected cells, and free virus particles at time t, respectively. The model can be described by the following equations:

| (1) |

where λ is the recruitment rate of uninfected T cells, d is the per capita death rate of uninfected cells, k is the rate constant at which uninfected cells get infected by free virus. δ is the per capita death rate of productively infected cells, p is the viral production rate of an infected cell, and c is the clearance rate of free virus. Cells in the eclipse phase revert to the uninfected T class at a constant rate b. In addition, they may alternatively progress to the productively infected class T* at the rate φ, or die at the rate δE. Notice that our model assumes that the expected residence time of a cell in the eclipse phase is exponentially distributed, and the parameter φ is determined, in part, by the activity of reverse transcriptase. For example, if reverse transcription is quick, then φ will be large and the infected cells in the eclipse phase will progress to the productively infected state with a high probability, i.e., φ/(b + φ + δE).

As with the basic HIV model, there are two possible steady states of model (1). One steady state is the infection-free steady state, the other is the infected steady state.

If we define

| (2) |

then it can be shown in Appendix A that the infected steady state exists if and only if ℛ0 > 1. In fact, ℛ0 can be written as the product of kλp/(dcδ) and φ/(b + φ + δE). Obviously, kλp/(dcδ) is the basic reproductive ratio of the standard model without the eclipse phase. φ/(b + φ + δE) is the probability that an infected T cell survives the eclipse phase. Therefore, ℛ0 in (2) defines the basic reproductive ratio for model (1). It is further shown that ℛ0 determines whether the virus population dies out or persists. The infection-free steady state Ē is locally asymptotically stable (l.a.s.) if ℛ0 < 1 and unstable if ℛ0 > 1. The infected steady state Ẽ is l.a.s. whenever it exists, i.e., when ℛ0 > 1.

It is clear that ℛ0 defined in (2) is an increasing function of the progression rate φ (a larger value of φ corresponds to quicker reverse transcription) and a decreasing function of the mortality rate δE. Thus, with all else equal, we expect that the viral strain that can complete reverse transcription more quickly is more likely to lead to a more severe infection (e.g., viral persistence at a higher infection level). This is supported by numerical simulations (Figures 1 and 2).

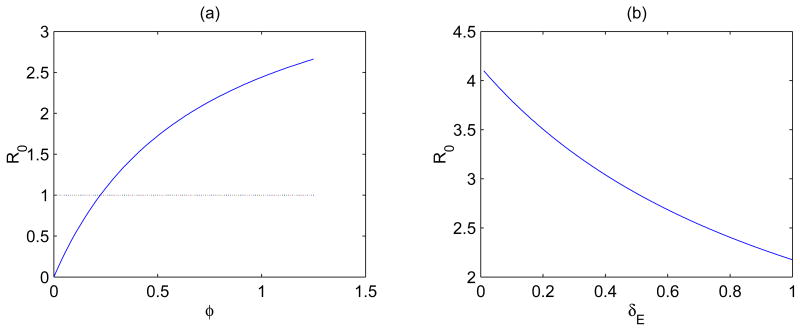

Figure 1.

(a) Plot of the basic reproductive ratio ℛ0 in (2) as a function of the progression rate φ for a fixed mortality rate of exposed cells δE = 0.7 day−1. (b) Plot of ℛ0 as a function of δE for a fixed value of φ = 1.1 day−1. Other parameter values are given in the text.

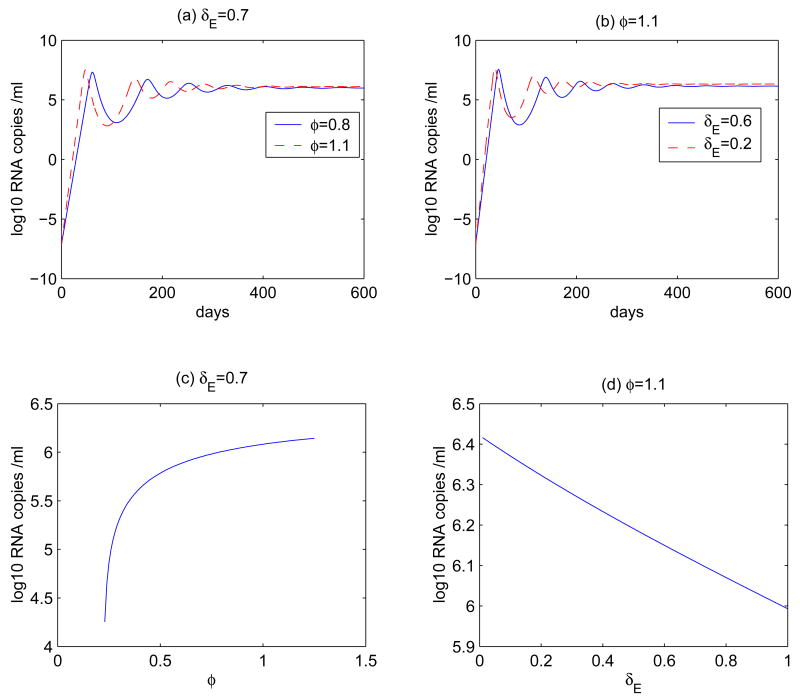

Figure 2.

Time plots for the virus dynamics of model (1) for different φ or for different δE. (a) φ = 0.8 or 1.1 day−1, δE = 0.7 day−1. (b) δE = 0.2 or 0.6 day−1, φ = 1.1 day−1. The values of other parameters are the same as those in Figure 1. The initial values for T, , T* and V are 106 ml−1 [40], 0, 0, and 10−6 ml−1 [55], respectively. The steady state of the viral load is plotted as a function of φ or δE in (c) and (d). When φ < 0.23, the virus population dies out.

In Figure 1, ℛ0 is plotted as either a function of φ or a function of δE. In Figure 1 (a), δE = 0.7 day−1 (or ln 2/δE = 1 day [63]) is fixed. It shows that ℛ0 > 1 for φ > 0.23 day−1, in which case the viral load will converge to the infected steady state, and that ℛ0 < 1 for φ < 0.23 day−1, in which case the virus population will die out (the infection-free steady state). In Figure 1 (b), φ = 1.1 day−1 (or 1/φ = 0.9 days [43]) is fixed. Other parameter values are chosen from the literatures: k = 2.4 × 10−8 ml day−1 [40]; λ = 104 ml−1 day−1 [14]; d=0.01 day−1 [31]; c=23 day−1 [47]; δ = 1 day−1 [29]. The viral production rate p can be written as Nδ, where N (burst size) is the total number of virus particles released by a productively infected cell over its lifespan [43]. The estimate of burst size varies from 100 to a few thousands [19, 23] and possibly could be significantly larger [5]. Here, as an example, we choose N = 4000. Thus, p = 4000 day−1. Because only a small fraction of cells in the eclipse phase will revert to the uninfected state [15], we assume that b=0.01 day−1.

Figure 2 demonstrates the dynamic behavior of the viral load for different progression rate φ or mortality rate δE. We observe that there is a viral peak followed by an oscillatory approach to a set-point value. As φ increases, the time needed to reach the peak viral load is shortened, while the amplitude of the peak and the subsequent set-point value are increased (Figure 2 (a)). We observe similar behaviors as the mortality rate δE decreases (Figure 2 (b)). The steady state of the viral load is presented as either a function of φ (δE = 0.7 day−1 is fixed, see Figure 2 (c)) or a function of δE (φ = 1.1 day−1 is fixed, see Figure 2 (d)). These results show that the viral strain that has a larger progression rate φ or a smaller mortality rate δE will have a higher viral steady state level, and thus is more likely to induce faster disease progression.

2.2 The model with two strains

To study the invasion of drug-resistant mutant variants into an environment in which the wild-type strain is already established, we incorporate both drug-resistant and drug-sensitive strains in the model (1) and get the following two-strain model:

| (3) |

where the subscripts s and r represent the drug sensitive and resistant strains, respectively.

For each strain, we obtain the corresponding reproductive ratio, which is given by

| (4) |

Let Ẽs denote the steady state in which only the drug-sensitive strain is present and Ẽr denote the steady state in which only the drug-resistant strain is present. We prove in Appendix B that each steady state is biologically feasible if and only if the reproductive ratio for the corresponding strain is greater than 1. Furthermore, if ℛs > ℛr > 1, then Ẽs is l.a.s. and Ẽr is unstable. If ℛr > ℛs then Ẽs is unstable and Ẽr is l.a.s. Therefore, the resistant strain cannot invade the sensitive strain if ℛr < ℛs. If ℛr > max(ℛs, 1) then the resistant strain is able to invade and out-compete the sensitive strain. We will apply this result to determine the criterion for invasion and to examine how the resistant virus may evolve to optimize its fitness in the presence of antiretroviral treatment.

2.3 The model with drug therapy and resistance

We modify model (3) by incorporating combination antiretroviral therapy. Currently, a combination of reverse transcriptase inhibitors (RTIs) and protease inhibitors (PIs) is commonly used in the treatment of HIV infection. RTIs interfere with the process of reverse transcription and prevent the infection of new target cells. PIs prevent infected cells from producing new infectious virus particles [38]. To incorporate these drug effects into our model, we define εRTI and εPI to be the efficacies of RTIs and PIs for the wild-type strain, respectively. We define these constants relative to the impact of the drugs on the most susceptible genetic variants of reverse transcriptase and protease. As a result, εi = 0 (i = RTI or PI) implies that the inhibitor is completely ineffective against wild-type virus, while εi = 1 implies that the inhibitor is 100% effective against them. Note that in reality 100% effectiveness may not be clinically feasible due to problems with drug delivery or absorption.

When εPI is say 0.7, this implies that 70% of the wild-type virus particles produced are non-infectious due to the action of the protease inhibitor. This population of virions has previously been denoted VNI [43]. The remaining 30% of particles are assumed not to be affected by the PI and contain the same population of virions as in an untreated patient. Although this population has a mixture of infectious and non-infectious virions, it has been previously denoted VI [43] and for simplicity called the infectious population. A more precise definition would call VI the virions not made non-infectious by the protease inhibitor. In the model below we will follow the drug sensitive and drug resistant forms of the VI population only, and denote them Vs and Vr, respectively. The equations for the drug sensitive and resistant virion populations corresponding to VNI will be ignored as they can be decoupled from the system (see (5)).

To model the reduced susceptibility of drug-resistant virus variants to antiretroviral agents, we assume that the drug efficacies of RTIs and PIs for the resistant strain are reduced by factors σRTI and σPI, respectively. σRTI and σPI are between 0 and 1. Therefore, εRTIσRTI and εPIσPI are the drug efficacies of RTIs and PIs for the resistant strain. σi = 1 (i = RTI or PI) corresponds to the completely drug-sensitive strain while σi = 0 corresponds to the completely drug-resistant strain.

In order to focus on the role of the progression rate of cells in the eclipse phase, φ, and the viral production rate, p, on the evolution of drug-resistant virus, we assume that all other parameters for the two strains in model (3) are equal, i.e.,

The cost of drug resistance will be discussed later.

The modified model including antiretroviral drugs and resistance can be described by the following equations:

| (5) |

In the above model, the progression rate of cells in the eclipse class to the productively infected state is reduced due to the effect of RTIs and the viral production rate of infectious virus is reduced due to the effect of HIV protease inhibitors. As noted above, the equations for the non-infectious particles generated by the PI decouple from the system. These equations are

The total drug sensitive and drug resistant populations are then and , respectively.

Because HIV resistance is usually associated with changes of highly conserved amino acid residues that are believed to be essential for the optimal enzyme function, drug-resistant variants display some extent of resistance-associated loss of viral fitness in the absence of therapy [8, 9]. We incorporate this feature in our model by assuming a reduced progression rate φ and a reduced viral production rate p for the resistant strain. Based on the arguments given previously, we assume that infected cells of the wild-type strain, the most susceptible strain to drug therapy, have the maximal progression rate, φs, and the maximal viral production rate, ps. Therefore, for all resistant strains we have φr < φs and pr < ps.

We further assume that the resistance factor, σRTI, is an increasing function of φr. The justification for this assumption is the following. φr is mainly determined by the activity of reverse transcriptase, and the more resistant a strain is to an RTI (a smaller σRTI) the more likely that the RT of that strain functions poorly (a smaller φr). Thus, we assume that σRTI is an increasing function of φr. Similarly, we assume that σPI is an increasing function of the viral production rate pr, which reflects the fact that the more drug-resistant a strain is to a protease inhibitor, the more poorly its protease functions and hence the lower the capacity to produce new infectious virus [8, 65].

As suggested in [10, 18], the mortality rate of productively infected cells is also an increasing function of the viral production rate. This is because the loss of cell resources utilized to produce virus may impair cell functions. In addition, cell-mediated immune responses are likely to rapidly kill cells expressing more viral proteins.

To summarize, in model (5) we have assumed that σRTI(φr), σPI(pr) and δr(pr) are all increasing functions, with σRTI(φs) = σPI(ps) = 1 and δr(pr) = δs when pr = ps, i.e., δr(ps) = δs.

3 Results

In this section, we use model (5) and the results in previous sections to investigate the evolution of drug-resistant strains in the presence of antiretroviral treatment. Specifically, we study how the resistant virus evolves to maximize its fitness, and derive the range of drug efficacy in which the drug-resistant strain will be able to invade and out-compete the wild-type strain.

3.1 Optimal φr and pr that maximize viral fitness

Within-host viral fitness has received increasing interest due to its potential clinical implications for viral load, drug resistance, and disease progression (see reviews in [8, 36, 46]). The term fitness is commonly used in clinical settings to describe the ability of a virus to effectively replicate in a particular environment. Due to the fact that drug-resistant virus is less susceptible to antiretroviral regimens, the mutant variant is more fit than the wild-type virus in the presence of drug, although resistance mutations may decrease the intrinsic capacity of the virus to replicate. In practice, it still remains unclear which assay is most appropriate to measure the fitness of HIV-1 isolates, and many studies have been performed to test different hypotheses that extend the definition of relative fitness (reviewed in [46]). The basic reproductive ratio is a commonly used measure of the absolute fitness of a virus within a host [18]. In this section we examine the effect of antiretroviral treatment on the HIV-1 fitness of resistant virus by analyzing the reproductive ratio in the presence of therapy.

The reproductive ratio of the resistant strain (in the presence of therapy) for model (5), denoted by ℛr, is given by a function of φr and pr (see (4)):

| (6) |

where

| (7) |

and σRTI(φr), σPI(pr), and δr(pr) are increasing functions as mentioned previously.

Using the formulas (6) and (7) we can find the optimal and that maximize the reproductive ratio ℛr(φr, pr). Because we assume that φr and pr are independent, we can maximize F1(φr) and F2(pr) individually. When specific forms of the functions σRTI(φr), σPI(pr), and δr(pr) are given we are able to obtain explicit formulas for and . Before we discuss some particular forms of these functions, we present the following result in terms of general functions, which provides some convenient criteria for finding the optimal and . The proof can be found in Appendix C.

Proposition 1

(i) ℛr is maximized at if there exists a unique value satisfying

| (8) |

and

| (9) |

(ii) ℛr is maximized at if there exists a unique value satisfying

| (10) |

and

| (11) |

Proposition 1 suggests that if σRTI(φr), σPI(pr) and δr(pr) are concave up functions, then equations (8) and (10) determine the optimal progression rate and the optimal viral production rate , respectively. It should be noted that the concave up property is not required in Proposition 1, as the four conditions, (8)-(11), involve only and .

We now consider some specific forms of the increasing functions σRTl(φr), σPI(pr) and δr(pr). Noticing that φr ≤ φs and σRTl(φs) = 1, we choose σRTl(φr) to be a simple power function

| (12) |

where a ≥ 1 is a constant, ensuring that the second derivative is nonnegative. From Proposition 1 we get the optimal progression rate (see (8)). Therefore, we can establish the following result:

Result 1

Let σRTl(φr) be given in (12). Then

if , then the optimal progression rate is φs; and

if , then the optimal progression rate is an intermediate value within (0, φs); i.e., .

This result suggests that when the drug efficacy εRTI is low, the best strategy for a resistant strain to achieve the maximal viral fitness is unchanged from the non-treatment scenario, i.e., infected cells in the eclipse phase need to progress to the productively infected state as soon as possible. When the drug efficacy is high, the optimal viral fitness is achieved at an intermediate value (in the case of a = 1), instead of the maximal progression rate φs.

To examine the optimal production rate , we assume that the drug resistance factor σPI(pr) is a linear function of pr, and that the death rate of productively infected cells of the resistant strain follows a non-linear relationship between the cell death and viral production as examined in [10]; i.e.,

| (13) |

where pr ≤ ps, β is a constant and m is a fixed background mortality rate. Since we require that the function value δr(pr) evaluated at ps (the wild-type strain) is exactly the constant δs, β can be chosen to be 2(δs − m). Then, using (10) we obtain the following result for the optimal production rate .

Result 2

Let σPI(pr) and δr(pr) be given by (13). Then the optimal production rate determined by equation (10) is

| (14) |

Moreover, if δs < 2m, then provides a threshold such that

the optimal production rate of resistant virus is ps if ; and

the optimal production rate of resistant virus is an intermediate value given by (14) if .

The formula (14) allows us to study the effect of the background mortality rate, m, on the viral fitness. As m → 0, the optimal production rate . A straightforward calculation shows that . This implies that slow production is the best strategy for long-lived infected cells. This result is consistent with the observation in [10].

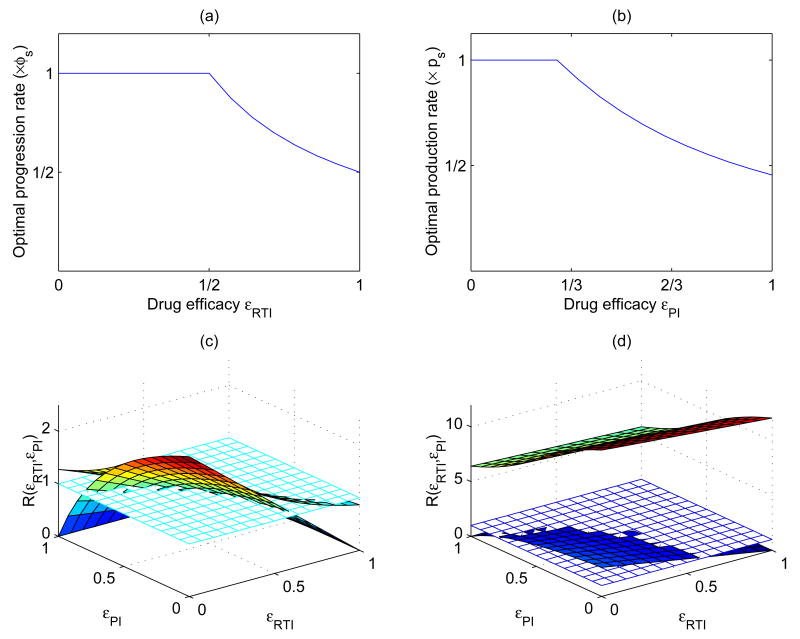

These results are demonstrated in Figure 3. Figure 3(a) illustrates the optimal progression rate for the special case a = 1 in (12). is plotted as a function of the drug efficacy of RTIs, εRTl. Figure 3 (b) plots the optimal production rate as a function of the drug efficacy of protease inhibitors, εPI. In these graphs, m is chosen to be the same as δE, and the values for other parameters are the same as those in Figure 1.

Figure 3.

(a) Plot of the optimal progression rate as a function of the drug efficacy of RTIs. (b) Plot of the optimal production rate as a function of the drug efficacy of PIs. (c) and (d) are plots of the reproductive ratios of the drug-resistant strain using the optimal and (as shown in (a) and (b)) and the wild-type strain. In (c) we assume m = δE = 0.7 day−1; in (d) m = d = 0.01 day−1. The other parameters are: k = 2.4 × 10−8 ml day−1, λ = 104 ml−1 day−1, d=0.01 day−1, c=23 day−1, b=0.01 day−1, δE = 0.7 day−1, δE = 1 day−1, φs = 1.25 day−1, ps = 4000 day−1. The flat surface is constant 1, the upper surface is for the reproductive ratio of the drug-resistant strain (ℛr), and the lower surface is for that of the wild-type strain (ℛs). We observe that in both cases, ℛr is always greater than or equal to ℛs. In (c), ℛr becomes less than 1 for a high level of drug efficacy, while in (d) ℛr is always greater than 1.

Figure 3 (c) and (d) plot the reproductive ratios for the drug-resistant strain using the optimal values and (as shown in the upper panel) and the wild-type strain. The flat surface is constant 1, the upper surface is for the reproductive ratio of the drug-resistant strain (ℛr, r for resistant strain), and the lower surface is for that of the wild-type strain (ℛs, s for sensitive strain). We choose different background mortality rates of infected cells. For example, in Figure 3 (c) m = δE and hence β = 2(δs − δE), and in Figure 3 (d) m = d and hence β = 2(δs − d). In both cases, the reproductive ratio of the resistant strain (ℛr) is always greater than or equal to that of the sensitive strain (ℛs).

We observe that for a large background mortality rate m (for example, m is equal to the death rate of infected cells in the eclipse phase), ℛr becomes less than one as drug efficacy increases although it is always greater than or equal to ℛs. Thus, in this case both strains of virus will be eradicated for a high drug efficacy (Figure 3 (c)). However, if the background mortality rate is very small (for example, m is equal to the death rate of uninfected T cells), then the threshold value of εPI corresponding to (14) is , which is less than zero. Hence, the optimal production rate is always given by the intermediate value determined by (14). In this case, simulation results show that ℛr is always greater than both ℛs and 1 (Figure 3 (d)), and according to the result given in Section 2.2, the drug-resistant strain that evolves with the optimal and will always be able to invade and out-compete the wild-type strain in the presence of drug therapy.

3.2 Invasion criterion

In the previous section, we have shown that if the drug-resistant strain continuously evolves to adopt the optimal and that maximize its viral fitness, then the resistant strain will always be expected to emerge and out-compete the established wild-type strain, provided that the antiretroviral treatment is not potent enough to eradicate both strains. Now a natural question arises: if the optimal viral fitness is not achieved, is it possible that the drug-resistant strain can still invade the population of the wild-type virus? If yes, what is the invasion criterion? Below we attempt to address these questions using model (5).

To derive the condition under which a drug-resistant strain (with parameters φr and pr, φr < φs and pr < ps) can invade the sensitive-strain in the presence of drug therapy, we assume that the population of wild-type virus is at the infected steady state. Recall that the infected steady state exists only if the reproductive ratio of the wild-type strain is greater than 1. From Section 2.2, the drug-resistant strain will be able to invade the wild-type strain if the following condition is satisfied:

| (15) |

The reproductive ratio for the drug-resistant strain in the presence of therapy is given by (see (4), (6) and (7))

| (16) |

and the reproductive ratio for the wild-type strain is

| (17) |

where the functions F1 and F2 are given in (7)). Using the criterion (15) and formulas (16) (17), we can establish the following result. The proof is given in Appendix D.

Result 3

(i) When both drug efficacies, εRTI and εPI, are low then the resistant strain cannot invade the sensitive strain. (ii) If the drug efficacies are above certain threshold values then invasion is possible by a resistant strain for which the progression rate φr and the viral production rate pr are in some given ranges.

Clearly, the invasion ranges defined by (37) and (38) in Appendix D depend on the drug efficacies εRTI and εPI. In fact, such ranges increase with increasing εRTI and εPI (see Figure 4). Also, if the background death rate m is much smaller than δs, then from the formula (38) we can see that ℛr > ℛs for almost all values of pr such that pr < ps.

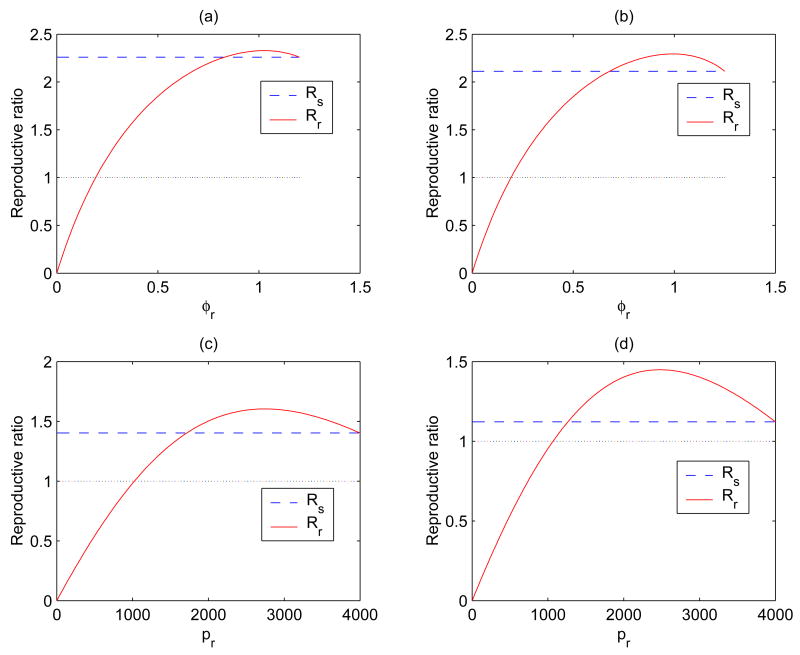

Figure 4.

Plots of ℛs and ℛr for different values of εRTI or εPI. The long dashed line is for ℛs, and the solid curve is for ℛr. (a) εRTI = 0.4; (b) εRTI = 0.5 (εPI = 0 and a = 3 for both (a) and (b)). (c) εPI = 0.5; (d) εPI = 0.6 (εRTI = 0 for both (c) and (d)). It is shown that the range in which ℛr > ℛs becomes bigger for larger values of εRTI or εPI.

In Figure 4, the reproductive ratios ℛs and ℛr are plotted either as a function of φr (Figures 4 (a) and (b)) or as a function of pr (Figures 4 (c) and (d)) for different values of εRTI or εPI. For example, Figures 4 (a) and (b) are for εRTI = 0.4 and εRTI = 0.5, respectively, for fixed values of εPI = 0 and a = 3 (see Eq.(12)). We observe that the range in which ℛr > ℛs is bigger for a larger value of εRTI, suggesting that for a more effective drug therapy, the resistant strain can invade the sensitive strain at a smaller progression rate φr.

Figures 4 (c) and (d) are for εPI = 0.5 and εPI = 0.6, respectively, for a fixed value of εRTI = 0. We have assumed that the background mortality rate m is equal to δE, hence β = 2(δs − δE). We observe again that the range in which ℛr > ℛs is bigger for a larger value of εPI. Therefore, for a higher protease inhibitor drug efficacy, the resistant strain can invade the sensitive strain at a smaller production rate pr.

4 Discussion and conclusion

Advances in the development of potent combination antiretroviral therapy have dramatically reduced HIV-related morbidity and mortality in the developed world. However, increasing emergence of resistance to antiretroviral drugs could challenge this achievement. The rapid development of drug resistant HIV variants is due to the high turnover of HIV—approximately 10 billion new virus particles are produced per day in the average mid-stage HIV-infected untreated patient [43]—and the exceptionally high error rate of HIV reverse transcriptase. This leads to a high mutation rate and constant production of new viral strains, even in the absence of drug therapy. Understanding the evolution of viral resistance during therapy has far-reaching implications in predicting treatment outcomes and designing treatment strategies employed in clinical practice.

In this work, we have developed a mathematical model to explore the initial constraints that may shape the evolution of viral resistance to antiretroviral drugs. We focused on the interactions between two classes of drugs (reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors) and the enzymes they target, and the trade-offs that are likely to result from such interactions. For RT and its inhibitor we assumed that there is a trade-off between the efficiency of RT and its susceptibility to the inhibitor. Our rationale was as follows: within-patient selection should favor the virus that maximizes its burst size N, the total number of virions made by an infected cell during its lifetime [18]. The burst size is a function of the lifespan of the infected cell, with longer living cells potentially able to make more virions. Due to the mortality rate of an infected cell the contribution of virion production to N is effectively discounted as the infected cell ages. In addition, viral mRNA is susceptible to attack by host nucleases once it enters the cell. As a result, within-host selection will inherently favor the virus with an RT that can rapidly reverse transcribe the virus' genome and integrate it into the host's genome. Because we expect these forms of RT to be favored by within-host selection we also expect them to be the most susceptible to inhibition by drugs designed to interfere with their activity. Along the same line of reasoning, other forms of RT that have low activity levels are expected to have low frequencies within the host, maintained primarily by drift and mutation. However, the very genetic changes that confer low activity levels to these RT variants are also likely to confer some resistance to the drugs designed to target RT with high activity levels. As a result we posit that there is likely a simple trade-off between RT activity and susceptibility to RT inhibitors.

The HIV protease also plays a critical role in the virus' life cycle by converting a viral polypeptide into mature and functional viral proteins necessary for viral infectivity. Because mutations associated with the emergence of drug resistance to protease inhibitors modify some key viral proteins [1, 59], the virus forced to develop resistance under drug pressure is thought to have a substantial impairment in its replicative capacity [7] even though some additional mutations can compensate for this impaired viral replication potential [36]. We thus expect that there is a trade-off between the efficacy of protease inhibitors and the viral production rate for the drug-resistant virus variants selected during therapy.

Once a cell begins actively producing virions it becomes highly susceptible to attack by the patient's immune response and viral cytopathic effects. Viral cytopathicity and cell-mediated immune responses are assumed to depend on the rate of viral production. If the mortality rate of infected cells is a concave up function with respect to the viral production rate, then the optimal viral production rate is likely to be at some intermediate level below its physiological maximum [18]. Under such conditions, an intermediate production rate will maximize the within-patient viral fitness by maximizing the burst size N. This is consistent with our findings when drug resistance to antiretroviral regimens is considered in the model. It should be mentioned that our model assumes that the viral production rate is time independent. When the production rate is allowed to vary with time during infection, the optimal production schedule to maximize the burst size is still to produce virus at a constant rate [10]. More results on the optimal viral production schedule from the perspective of virus can be found in [10].

Taken together, the model developed here allows us to investigate the fitness of different HIV variants taking into account the trade-offs between the progression of infected cells in the eclipse phase and resistance to RT inhibitors, between viral production and cell mortality, and between viral production and resistance to protease inhibitors. The model predicts that when the drug efficacy is not high enough to exert sufficient selective pressure (the threshold values in our example are εRTI = 0.5 and ), the resistant strain will be unable to invade the established sensitive strain. For a more effective drug therapy (but not potent enough to eradicate both the wild-type and resistant strains), a wider range of resistant virus variants can invade and out-compete the drug-sensitive strain.

In the present model, the efficacies of antiretroviral drugs are assumed to be constant. However, this assumption may not be realistic because drug concentrations in the blood and in cells continuously vary due to drug absorption, distribution and metabolism. There are some existing models that use time-varying drug concentrations to determine the efficacy of antiviral treatment [14, 24, 57, 62]. The pharmacokinetic model developed by Dixit and Perelson [14] was also employed to determine drug efficacies for both the sensitive and resistant strains [51]. They showed that using the average drug efficacy can still give a good prediction of the long-term outcome of therapy although the viral load displays frequent oscillations when the time-varying drug efficacy is employed.

Another important factor that affects drug efficacy is patients' adherence to prescribed regimen protocols. In fact, non-adherence and non-persistence with antiretroviral therapy is the major reason most individuals fail to benefit from their treatments [2]. A number of mathematical models have been developed to study the effects of non-perfect adherence to drug regimens [16, 24, 45, 51, 53, 57, 61]. An overview can be found in Heffernan and Wahl [20]. Careful modeling of drug pharmacokinetics and more realistic adherence patterns can provide an important tool in the study of the kinetics of evolutionary adaptation of HIV to drug therapy and ultimately may improve our ability to develop procedures to defeat this deadly virus.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC52-06NA25396. This work was supported by NSF grant DMS-0314575 and James S. McDonnell Foundation 21st Century Science Initiative (ZF), and NIH grants AI28433 and RR06555 (ASP). The manuscript was finalized when LR visited the Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory in 2006. The authors thank three anonymous referees for their constructive comments that improved this manuscript.

Appendix A. Stability of steady states of model (1)

The infection-free steady state of model (1) is

| (18) |

The infected steady state is , where

| (19) |

Using (2), can be rewritten as

Therefore, the infected steady state exists if and only if ℛ0 > 1.

Let denote a steady state of model (1). Then the characteristic equation at Ê is

| (20) |

where ζ is an eigenvalue. Equation (20) can be simplified to

| (21) |

(i) Let ℛ0 < 1. Evaluating (21) at the infection-free steady state Ē, we get

Clearly, there is one negative eigenvalue −d, and other eigenvalues are determined by

which can be rewritten as (see (2))

| (22) |

If ζ has a nonnegative real part, then the modulus of the left-hand side of (22) satisfies

| (23) |

which leads to a contradiction in (22) since ℛ0 < 1. Therefore, all the eigenvalues have negative real parts, and hence Ē is l.a.s.

When ℛ0 > 1, we define

It is clear that f(0) < 0 and f(ζ) → ∞ when ζ → ∞. By the continuity we know there exists at least one positive root. Hence, the equilibrium point Ē is unstable if ℛ0 > 1.

(ii) Let ℛ0 > 1. Substituting the infected steady state Ẽ for Ê in the characteristic equation (21), we have

| (24) |

Obviously, (24) does not have a nonnegative real solution.

From (19) and (2), we can write Ṽ in terms of the basic reproductive ratio in the form

Now we want to prove that (24) does not have any complex root ζ with a nonnegative real part. Suppose, by contradiction, that ζ = x + iy with x ≥ 0, y > 0 is a root of (24).

When ℛ0 → 1, equation (24) reduces to

| (25) |

Using the same arguments as in part (i), we can show that (25) does not have any root with a nonnegative real part.

By the continuous dependence of roots of the characteristic equation on ℛ0, we know that the curve of the roots must cross the imaginary axis as ℛ0 decreases sufficiently close to 1. That is, the characteristic equation (24) has a pure imaginary root, say, iy0, where y0 > 0. From (24), we have

| (26) |

We now claim that the following inequality holds:

| (27) |

In fact, after straightforward computations, we have

Thus, (27) holds. It follows that

This contradicts (26). Therefore, we conclude that the characteristic equation (24) does not have any root with a nonnegative real part. Thus, the infected steady state Ē is l.a.s whenever it exists.

Appendix B. Steady states and stability of model (3)

Assume that and . We have

| (28) |

Obviously, each steady state exists if and only if the corresponding reproductive ratio is greater than 1.

If denotes a coexistence steady state (i.e., and , hence both strains are present), then Ť satisfies . Therefore, Ě exists only if ℛr = ℛs.

The Jacobian matrix at Ẽs is

where

| (29) |

| (30) |

and “*” denotes a 4 × 3 matrix that does not affect the proof. Notice that the characteristic equation of G is exactly the same equation (20) with the subscript s added. From Appendix A and ℛs > 1, all eigenvalues of G have negative real parts. Thus, the stability of Ẽs is completely determined by the eigenvalues of H.

Suppose ζ is an eigenvalue of H, then ζ satisfies

| (31) |

If we define

| (32) |

Then (31) can be rewritten as

| (33) |

We remark that represents the effective reproductive ratio for the drug-resistant strain (i.e., the reproductive ratio when the sensitive strain is at its infected steady state). If , then the resistant strain will be able to invade the established wild-type strain.

Using the same arguments as in Appendix A, we have that Ẽs is l.a.s. if and it is unstable if . Notice from (28) and (4) that

Substituting this for T̃s in (32) and using (4), we obtain

Thus, if and only if ℛr > ℛs and if and only if ℛr < ℛs. It follows that Ẽs is l.a.s. if ℛr < ℛs, and it is unstable if ℛr < ℛs.

From the mathematical symmetry of the two strains we can use the same arguments for the stability analysis of Ẽr, and show that Ẽr is l.a.s. if ℛr > ℛs and unstable if ℛr < ℛs.

Appendix C. Proof of Proposition 1

(i) We want to find that maximizes F1(φr) (see equation (7)). Let

| (34) |

Then F1(φr) is maximized if and only if f1(φr) is maximized. Notice that (8) holds if and only if is a critical point of f1 on (0, φs). Since , we have

Hence, if . It follows that f1, and hence ℛr, assumes its maximum at if (8) and (9) hold.

(ii) If satisfies (10) then we can easily verify that is a critical point of F2(pr); i.e., . The second derivative of F2(pr) at is

| (35) |

It is easy to verify that if and are both nonnegative, which implies that F2(pr) has a maximum at . Therefore, ℛr is maximized at . This finishes the proof of Proposition 1.

Appendix D. Proof of Result 3

We prove this result using the specific functional forms for σRTI(φr), σPI(pr), and δr(pr) given by (12) (in the case of a = 1) and (13).

(i) The invasion condition (15) is equivalent to (see (16) and (17))

| (36) |

From the analysis in Section 3.1, we know that for a low level of drug efficacy εRTI (e.g., 0 < εRTI < 1/2 when a = 1, see Result 1), the maximum of F1(φr) can only occur at . Thus, F1(φr) < F1(φs) for φr < φs. Similarly, from Result 2 we know that the maximum of F2(pr) can only occur at if , where . Thus, F2(Pr) < F2(ps) for pr < ps. Therefore, the invasion condition (36) does not hold for any drug efficacies with 0 < εRTI < 1/2 and .

(ii) When 1/2 < εRTI < 1, solving the inequality F1(φr) > F1(φs) for φr, we have

which is equivalent to

or

From the above inequality (and noticing that εRTI > 1/2), we have

| (37) |

When , solving the inequality F2(pr) > F2(ps) for pr gives

which can be rewritten as

Noticing that β = 2(δs − m), we can solve the above inequality and obtain

| (38) |

Since , which guarantees that

we know that (38) defines an interval on which F2(pr) > F2(ps). Therefore, for (φr, pr) in the regions defined by (37) and (38) the invasion condition (36), or equivalently (15), holds.

This finishes the proof of Result 3.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barrie KA, Perez EE, Lamers SL, Farmerie WG, Dunn BM, Sleasman JW, Goodenow MM. Natural variation in HIV-1 protease, Gag p7 and p6, and protease cleavage sites within gag/pol polyproteins: amino acid substitutions in the absence of protease inhibitors in mothers and children infected by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology. 1996;219:407–416. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker SL, Dezii CM, Burtcel B, Kawabata H, Hodder S. Young HIV-infected adults are at greater risk for medication nonadherence. Med Gen Med. 2002;4:21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonhoeffer S, Nowak MA. Pre-existence and emergence of drug resistance in HIV-1 infection. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1997;264:631–637. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callaway DS, Perelson AS. HIV-1 infection and low steady state viral loads. Bull Math Biol. 2002;64:29–64. doi: 10.1006/bulm.2001.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan Chen H, Di Mascio M, Perelson AS, Ho DD, Zhang L. Determination of virus burst size in vivo using a single-cycle SIV in rhesus macaques. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707449104. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun TW, Carruth L, Finzi D, Shen X, DiGiuseppe JA, Taylor H, Hermankova M, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Quinn TC, Kuo YH, Brookmeyer R, Zeiger MA, Barditch-Crovo P, Siliciano RF. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1997;387:183–188. doi: 10.1038/387183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clavel F, Hance AJ. HIV drug resistance. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1023–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra025195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clavel F, Race E, Mammano F. HIV drug resistance and viral fitness. Adv Pharmacol. 2000;49:41–66. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(00)49023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffin JM. HIV population dynamics in vivo: implications for genetic variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science. 1995;267:483–489. doi: 10.1126/science.7824947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coombs D, Gilchrist MA, Percus J, Perelson AS. Optimal viral production. Bull Math Biol. 2003;65:1003–1023. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8240(03)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culshaw RV, Ruan S. A delay-differential equation model of HIV infection of CD4+ T-cells. Math Biosci. 2000;165:27–39. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(00)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Paepe M, Taddei F. Viruses' life history: towards a mechanistic basis of a trade-off between survival and reproduction among phages. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:1248–1256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Leenheer P, Smith HL. Virus dynamics: a global analysis. SIAM J Appl Math. 2003;63:1313–1327. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixit NM, Perelson AS. Complex patterns of viral load decay under antiretroviral therapy: influence of pharmacokinetics and intracellular delay. J Theor Biol. 2004;226:95–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Essunger P, Perelson AS. Modeling HIV infection of CD4+ T-cell subpopulations. J Theor Biol. 1994;170:367–391. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1994.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson NM, Donnelly CA, Hooper J, Ghani AC, Fraser C, Bartley LM, Rode RA, Vernazza P, Lapins D, Mayer SL, Anderson RM. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its impact on clinical outcome in HIV-infected patients. J R Soc Interface. 2005;2:349–363. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2005.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finzi D, Hermankova M, Pierson T, Carruth LM, Buck C, Chaisson RE, Quinn TC, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Brookmeyer R, Gallant J, Markowitz M, Ho DD, Richman DD, Siliciano RF. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science. 1997;278:1295–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilchrist MA, Coombs D, Perelson AS. Optimizing within-host viral fitness: infected cell lifespan and virion production rate. J Theor Biol. 2004;229:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haase AT, Henry K, Zupancic M, Sedgewick G, Faust RA, Melroe H, Cavert W, Gebhard K, Staskus K, Zhang ZQ, Dailey PJ, Balfour HH, Jr, Erice A, Perelson AS. Quantitative image analysis of HIV-1 infection in lymphoid tissue. Science. 1996;274:985–989. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heffernan JM, Wahl LM. Treatment interruptions and resistance: a review. In: Tan WY, Wu H, editors. Deterministic and Stochastic Models of AIDS and HIV with Intervention. World Scientific Press; Singapore: 2005. pp. 423–456. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herz AV, Bonhoeffer S, Anderson RM, May RM, Nowak MA. Viral dynamics in vivo: limitations on estimates of intracellular delay and virus decay. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7247–7251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho DD, Neumann AU, Perelson AS, Chen W, Leonard JM, Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:123–126. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hockett RD, Kilby JM, Derdeyn CA, Saag MS, Sillers M, Squires K, Chiz S, Nowak MA, Shaw GM, Bucy RP. Constant mean viral copy number per infected cell in tissues regardless of high, low, or undetectable plasma HIV RNA. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1545–1554. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.10.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y, Rosenkranz SL, Wu H. Modeling HIV dynamics and antiviral response with consideration of time-varying drug exposures, adherence and phenotypic sensitivity. Math Biosci. 2003;184:165–186. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(03)00058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kepler TB, Perelson AS. Drug concentration heterogeneity facilitates the evolution of drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11514–11519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirschner DE, Webb GF. A model for treatment strategy in the chemotherapy of AIDS. Bull Math Biol. 1996;58:367–390. doi: 10.1016/0092-8240(95)00345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirschner DE, Webb GF. Understanding drug resistance for montherapy treatment of HIV infection. Bull Math Biol. 1997;59:763–786. doi: 10.1007/BF02458429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larder B. Nucleosides and foscarnet-mechanisms. In: Richman DD, editor. Antiviral Drug Resistance. John Viley and Sons Ltd; 1996. pp. 169–190. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markowitz M, Louie M, Hurley A, Sun E, Di Mascio M, Perelson AS, Ho DD. A novel antiviral intervention results in more accurate assessment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication dynamics and T-cell decay in vivo. J Virol. 2003;77:5037–5038. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.5037-5038.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mittler JE, Markowitz M, Ho DD, Perelson AS. Refined estimates for HIV-1 clearance rate and intracellular delay. AIDS. 1999;13:1415–1417. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199907300-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohri H, Bonhoeffer S, Monard S, Perelson AS, Ho DD. Rapid turnover of T lymphocytes in SIV-infected rhesus macaques. Science. 1998;279:1223–1227. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mugavero MJ, Hicks CB. HIV resistance and the effectiveness of combination antiretroviral treatment. Drug Discovery Today: Therapeutic Strategies. 2004;1:529–535. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson PW, Gilchrist MA, Coombs D, Hyman JM, Perelson AS. An age-structured model of HIV infection that allows for variations in the production rate of viral particles and the death rate of productively infected cells. Math Biosci Eng. 2004;1:267–288. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2004.1.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson PW, Murray JD, Perelson AS. A model of HIV-1 pathogenesis that includes an intracellular delay. Math Biosci. 2000;163:201–215. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(99)00055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson PW, Perelson AS. Mathematical analysis of delay differential equation models of HIV-1 infection. Math Biosci. 2002;179:73–94. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(02)00099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nijhuis M, Deeks S, Boucher C. Implications of antiretroviral resistance on viral fitness. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2001;14:23–28. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200102000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nowak MA, Bonhoeffer S, Shaw GM, May RM. Anti-viral drug treatment: dynamics of resistance in free virus and infected cell populations. J Theor Biol. 1997;184:203–217. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1996.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nowak MA, May RM. Virus Dynamics: Mathematical Principles of Immunology and Virology. Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perelson AS. Modelling viral and immune system dynamics. Nature Rev Immunol. 2002;2:28–36. doi: 10.1038/nri700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perelson AS, Kirschner DE, De Boer R. Dynamics of HIV infection of CD4+ T cells. Math Biosci. 1993;114:81–125. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(93)90043-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perelson AS, Nelson PW. Mathematical analysis of HIV-1 dynamics in vivo. SIAM Rev. 1999;41:3–44. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perelson AS, Nelson PW. Proceedings of Symposia in Applied Mathematics. Vol. 59. American Mathematical Society; 2002. Modeling viral infections; pp. 139–172. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perelson AS, Neumann AU, Markowitz M, Leonard JM, Ho DD. HIV-1 dynamics in vivo: virion clearance rate, infected cell life-span, and viral generation time. Science. 1996;271:1582–1586. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perelson AS, Essunger P, Cao Y, Vesanen M, Hurley A, Saksela K, Markowitz M, Ho DD. Decay characteristics of HIV-1-infected compartments during combination therapy. Nature. 1997;387:188–191. doi: 10.1038/387188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phillips AN, Youle M, Johnson M, Loveday C. Use of a stochastic model to develop understanding of the impact of different patterns of antiretroviral drug use on resistance development. AIDS. 2001;15:2211–2220. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200111230-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinones-Mateu ME, Arts EJ. HIV-1 fitness: implications for drug resistance, disease progression, and global epidemic evolution. In: Kuiken C, Foley B, Hahn B, Marx P, McCutchan F, Mellors J, Wolinsky S, Korber B, editors. HIV Sequence Compendium 2001, Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group. Los Alamos National Laboratory; Los Alamos NM: 2001. pp. 134–170. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramratnam B, Bonhoeffer S, Binley J, Hurley A, Zhang L, Mittler JE, Markowitz M, Moore JP, Perelson AS, Ho DD. Rapid production and clearance of HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus assessed by large volume plasma apheresis. Lancet. 1999;354:1782–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ribeiro RM, Bonhoeffer S. Production of resistant HIV mutants during antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7681–7686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ribeiro RM, Bonhoeffer S, Nowak MA. The frequency of resistant mutant virus before antiviral therapy. AIDS. 1998;12:461–465. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199805000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rong L, Feng Z, Perelson A. Mathematical analysis of age-structured HIV-1 dynamics with combination antiretroviral therapy. SIAM J Appl Math. 2007;67:731–756. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rong L, Feng Z, Perelson AS. Emergence of HIV-1 drug resistance during antiretroviral treatment. Bull Math Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s11538-007-9203-3. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simon V, Ho DD. HIV-1 dynamics in vivo: implications for therapy. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:181–190. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith RJ. Adherence to antiretroviral HIV drugs: how many doses can you miss before resistance emerges? Proc R Soc B. 2006;273:617–624. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith RJ, Wahl LM. Drug resistance in an immunological model of HIV-1 infection with impulsive drug effects. Bull Math Biol. 2005;67:783–813. doi: 10.1016/j.bulm.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stafford MA, Corey L, Cao Y, Daar ES, Ho DD, Perelson AS. Modeling plasma virus concentration during primary HIV infection. J Theor Biol. 2000;203:285–301. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stilianakis NI, Boucher CA, De Jong MD, Van Leeuwen R, Schuurman R, De Boer RJ. Clinical data sets of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase-resistant mutants explained by a mathematical model. J Virol. 1997;71:161–168. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.161-168.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wahl LM, Nowak MA. Adherence and drug resistance: predictions for therapy outcome. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2000;267:835–843. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wei X, Ghosh SK, Taylor ME, Johnson VA, Emini EA, Deutsch P, Lifson JD, Bonhoeffer S, Nowak MA, Hahn BH, Saag MS, Shaw GM. Viral dynamics in human-immunodeficiency-virus type-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Winslow DL, Stack S, King R, Scarnati H, Bincsik A, Otto MJ. Limited sequence diversity of the HIV type 1 protease gene from clinical isolates and in vitro susceptibility to HIV protease inhibitors. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:107–113. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong JK, Hezareh M, Gunthard HF, Havlir DV, Ignacio CC, Spina CA, Richman DD. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia. Science. 1997;278:1291–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu H, Huang Y, Acosta EP, Park JG, Yu S, Rosenkranz SL, Kuritzkes DR, Eron JJ, Perelson AS, Gerber JG. Pharmacodynamics of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1 infected patients: using viral dynamic models that incorporate drug susceptibility and adherence. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2006;33:399–419. doi: 10.1007/s10928-006-9006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu H, Huang Y, Acosta EP, Rosenkranz SL, Kuritzkes DR, Eron JJ, Perelson AS, Gerber JG. Modeling long-term HIV dynamics and antiretroviral response: effects of drug potency, pharmacokinetics, adherence, and drug resistance. JAIDS. 2005;39:272–283. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000165907.04710.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zack JA, Arrigo SJ, Weitsman SR, Go AS, Haislip A, Chen IS. HIV-1 entry into quiescent primary lymphocytes: molecular analysis reveals a labile latent viral structure. Cell. 1990;61:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90802-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zack JA, Haislip AM, Krogstad P, Chen IS. Incompletely reverse-transcribed human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes in quiescent cells can function as intermediates in the retroviral cycle. J Virol. 1992;66:1717–1725. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1717-1725.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zennou V, Mammano F, Paulous S, Mathez D, Clavel F. Loss of viral fitness associated with multiple gag and gag-pol processing defects in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants selected for resistance to protease inhibitors in vivo. J Virol. 1998;72:3300–3306. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3300-3306.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang L, Ramratnam B, Tenner-Racz K, He Y, Vesanen M, Lewin S, Talal A, Racz P, Perelson AS, Korber BT, Markowitz M, Ho DD. Quantifying residual HIV-1 replication in patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1605–1613. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905273402101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]