Abstract

Hyaluronan (HA), a non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan, is widely used in the clinic for viscosurgery, viscosupplementation, and treatment of osteoarthritis. Four decades of chemical modification of HA have generated derivatives in which the biophysical and biochemical properties, as well as the rates of enzymatic degradation in vivo have been manipulated and tailored for specific clinical needs. One earlier modification adds multiple thiol groups to HA through hydrazide linkages, leading to a readily crosslinkable material for adhesion prevention and wound healing. We now describe the synthesis and chemical characterization of a novel thioethyl ether derivative of HA, HA–sulfhydryl (HASH), with a minimal tether between the HA and the thiol group. Unlike earlier thiol-modified HA derivatives, HASH cannot be readily crosslinked to form a hydrogel using either oxidative or bivalent electrophilic conditions, thus offering a unique polymeric polythiol that remains soluble. Moreover, HASH showed no cytotoxicity towards primary human fibroblasts and reduced the apoptosis rates of primary chondrocytes exposed to hydrogen peroxide in vitro. These properties foreshadow the clinical potential of HASH to moderate inflammation and to act as a chondroprotective agent in vivo.

Keywords: cytocompatible, apoptosis, chondrocyte, ethylene sulfide, chemical modification, glycosaminoglycan, thiol, sulfhydryl, primary human fibroblasts

1. Introduction

Hyaluronan (HA) is a naturally occurring unbranched, polyanionic polymer composed of alternating units of glucuronic acid and N-acetylglucosamine [1, 2, 3]. HA is involved in numerous important processes such as water homeostasis of tissues and joint lubrication [1], cartilage matrix stabilization [4, 1], cell motility [5, 6], morphogenesis and embryogenesis [7], and inflammation [8].

Native HA has been extensively used in numerous drug delivery and surgical applications [9], in viscosurgery and viscosupplementation, and for scar-free wound healing [10]. Nevertheless, the rapid in vivo degradation of the macromolecule and its unsatisfactory biomechanical properties preclude many clinical applications. Chemical and mechanical robustness were ultimately achieved via a combination of chemical modifications and subsequent crosslinking [11, 12]. The principal targets of HA for chemical modification are the carboxyl (glucuronic acid residue) and primary hydroxyl (N-acetylglucosamine residue) groups of the molecule [12]. Carboxyl groups have been most commonly modified by esterification using carbodiimide-mediated chemistry [13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. The highly esterified HA obtained was water insoluble and could be molded into fibers and sponges or formulated as microspheres [13]. Carbodiimide-activated carboxyl groups were also rendered susceptible to nucleophiles such as hydrazides [16, 17] and aminooxy groups [18]. The resulting polymers were biocompatible and could further be used for drug-coupling (HA-mitomycin C) [19, 20], fluorescent probe attachment (HA-BODIPY) [15], hydrogel formation via cross-linking [21, 22] or photopolymerization [23]. In addition, the hydroxyl groups of HA have been sulfated [24, 25, 26, 27], vicinal diols oxidized to dialdehydes with periodate [28, 29], esterified [30], etherified [31, 32], and coupled via an isourea intermediate [33]. Functionalities such as amides, hydrazides, and thiols were also chemically introduced as pendant groups for further crosslinking. Most of the customized HA polymers were intended for use as hydrogels [34, 35, 31, 32, 23, 19, 36, 21]. The customizable in vivo residence times achieved by tailoring enzymatic degradation rates of hydrogels led to their extensive use in tissue engineering and reparative medicine applications.

Thiolated HA biomaterials were previously synthesized via carbodiimide activation of carboxyl groups in the presence of disulfide containing hydrazides. Following reduction, these strategies yielded macromonomeric polythiols that could be crosslinked oxidatively via disulfide bonds or with bivalent electrophiles via thio-ether bonds, to obtain hydrogels and sponges [21, 22]. A variety of medical and tissue engineering applications were successfully demonstrated by using thiol-modified crosslinked HA composites [34, 37, 35, 38, 39, 40, 41].

Herein, we report the synthesis and characterization of a novel 2-thioethyl ether hyaluronan derivative, which has the minimal length two-carbon thiol tether. The new thiol modified HA polymer was designated HA-sulfhydryl or HASH, and the extent of thiol modification was readily quantified by chemical derivatization with monovalent thiol-reactive reagents. Surprisingly, however, HASH cannot be crosslinked via disulfide bonds or with bivalent electrophiles., We attribute this in part to a lower degree of thiol substitution, and in part to steric hindrance that prevents sulfhydryl groups from forming bivalent linkages necessary for gelation to occur. Finally, HASH is cytocompatible and protected primary ovine chondrocytes from H2O2-induced apoptosis in vitro. Taken together, HASH may have utility in the treatment of inflammation due to arthritis.

2. Experimental methods

2.1. Materials and analytical instrumentation

High molecular weight hyaluronan (HA, MW = 824 kDa) was from Contipro C Co, Czech Republic. Ethylene sulfide and 5,5’-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) were from Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI). Phosphate buffered saline 10X (PBS), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), hydrochloric acid 12.1 N (HCl), dibasic sodium phosphate, heptahydrate (Na2PO4·7H2O) and SpectraPor dialysis tubing MWCO 10.000 were from Fisher Scientific (Hanover Park, IL). SAMSA fluorescein (5-((2-(and-3)-S-acetylmercapto)succinoyl)amino) fluorescein) mixed isomers was purchased from Molecular Probes Inc. (Eugene, OR). Dithiothreitol (DTT) was from BioVectra DCL (Charlottetown, PE, Canada). Celite® 545 was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). HS-PEG-SH was from Nektar Therapeutics (San Carlos, CA). CMHA-S, HABA, HAIA, and divalent PEG electrophiles were prepared as described [42, 43]. For cell culture, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)/F12, fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100X penicillin/streptomycin were from Gibco (Carlsbad, CA). Type II collagenase and H2O2 (30%) were from Sigma (Milwaukee, WI). The Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit was from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ).

1H-NMR spectral data were acquired using a Varian INOVA 400 at 400 MHz. UV/VIS spectra and measurements were performed on a Hewlett-Packard 8453 UV-visible spectrometer (Palo Alto, CA). Chemical shifts are reported relative to the internal HDO peak (δ = 4.67 ppm). Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) analysis was obtained using the following components: Waters 486 tunable absorbance detector, Waters 410 differential refractometer, Waters 515 HPLC pump and Ultrahydrogel 1000 column (7.8 × 300 mm) (Milford, MA). The mobile phase for GPC consisted of 0.2 M PBS buffer/methanol (80:20 volume ratio) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. HA standards used to calibrate the system were from Novozymes Biopolymers, Bågsvaerd, Denmark. An OPTIMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) was used to determine the 490 nm absorbance values for cell viability assays.

2.2. Synthesis of HA-sulfhydryl (HASH)

Hyaluronan (2.0 g, MW 824 kDa) was dissolved in 400 mL distilled water (0.5% w/v solution). The pH of the solution was raised to 10.03 with 1 M NaOH. A 5-fold molar excess of ethylene sulfide was added dropwise to the HA solution and the reaction mixture was stirred vigorously overnight in the hood at room temperature. Some precipitation was observed, likely due to ethylene sulfide oligomerization. The solution was then filtered through a 3-cm bed of Celite® 545. To the clear filtrate, a 5-fold molar excess of DTT was added, and the pH of the solution was raised to 8.5 with 1 M NaOH. The reaction was stirred overnight at room temperature in the hood. After 24 h the pH of the reaction mixture was decreased to 3.5 with 6 N HCl. The acidified solution was dialyzed (MWCO 10,000) against dilute HCl (pH 3.5). Next, the solution was lyophilized and the product was analyzed by 1H-NMR (solvent: D2O; chemical shifts corresponding to the substituent: δ = 3.82 ppm (-CH2-CH2-SH) and δ = 3.69 ppm (-CH2-CH2-SH)). Yield = 78%; m = 1.97 g. The degree of thiolation (as determined by SAMSA and DTNB derivatization) varied from 4–14% for different batches; MW = 180 kDa (GPC); polydispersity index = 1.86.

2.3. SAMSA fluorescein derivatization

SAMSA fluorescein (4 mg) was dissolved in 400 µL of 0.1 M NaOH and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. HCl 6 N (5.6 µL) was then added, followed by the addition of 80 µL 5 NaH2PO4·H2O, pH 7.0. HA and HASH were each reacted with 5-fold excess of activated SAMSA fluorescein for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction mixtures were then dialyzed (MWCO 2000) against dilute NaOH (pH 9.0) for 3 days. The A494 and fluorescence of the SAMSA derivatized compounds were both determined.

2.4. HASH derivatization with 4-(hydroxymercuri) benzoate

HASH (25 mg) was dissolved in nanopure water to give a 1% w/v solution. To this solution 23 mg of 4-(hydroxymercuri)benzoic acid sodium salt was added (approximately 1:1 stoichiometry to disaccharide units) and the reaction was stirred for 24 h at room temperature. The white precipitate formed (unreacted 4-(hydroxymercuri)benzoic acid sodium salt) was filtered out. The derivatized HA was lyophilized and then analyzed by 1H-NMR (D2O). New chemical shifts: δ = 7.4 and 7.7 ppm (p-substituted C6H4).

2.5. HASH derivatization with iodoacetate

HASH (25 mg) was dissolved in nanopure water to give a 1% w/v solution. Sodium iodoacetate (~ 12 mg) was added to the HA solution and the mixture was stirred for 24 h at room temperature. Subsequent to dialysis against nanopure water (MWCO 3500), the derivatized HASH was lyophilized and analyzed by 1H-NMR (D2O). The peaks corresponding to iodoacetic acid protons (ICH2COONa) were observed in the δ = 3 to δ = 3.7 ppm region.

2.6. Thiol content determination

HASH (24 mg) was dissolved in 8 mL DTNB solution (2 mg/mL in 0.1 M PBS, pH 8.0) and the solution was stirred overnight at room temperature followed by subsequent dialysis for 3 days (Slide-A-Lyzer 10 K dialysis cassette, Pierce, Rockford, IL). The derivatized HASH was lyophilized and 2 mg of the lyophilized material was then dissolved in 1 mL 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4. A solution of DTT (2.5 mL, 1% w/v DTT in dH2O, pH 8.5) was added to 0.1 mL TNB-HASH solution. After the mixture turned yellow, the A412 was determined using a Hewlett-Packard 8453 UV-visible spectrometer (Palo Alto, CA).

2.7. Attempted crosslinking of HASH

HASH solutions (2% and 2.5% w/v) were prepared in 1X PBS buffer and the pH of the solutions was adjusted to 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 (the pKa range of thiol groups). Crosslinker solutions (4%, 8% and 10% w/v) were used for crosslinking experiments, and Table 1 summarizes the bivalent electrophiles or oxidants evaluated. As positive control, a thiol-derivatized carboxymethylated HA (CMHA-S) was used. HASH and crosslinker solutions were mixed in different molar ratios (1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 2:1, 3:1; 4:1 and 5:1) and set at room temperature. Gelation was monitored by using the test tube inversion assay. No gelation was observed for any of the tested conditions, even after 48 h.

Table 1.

Structures of bivalent thiol-reactive crosslinkers evaluated with thiol-modified HA derivatives. All PEG derivatives were prepared from PEG 3400

| Crosslinkers tested | |

|---|---|

| Crosslinker | Structure |

| Polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA) | |

| Polyethylene glycol bisbromoacetate (PEGDBrAc)[43] | |

| Polyethylene glycol bisiodoacetate (PEGDIAc)[43] | |

| Polyethylene glycol bismaleimide (PEGDMal)[43] | |

| HS-PEG-SH | |

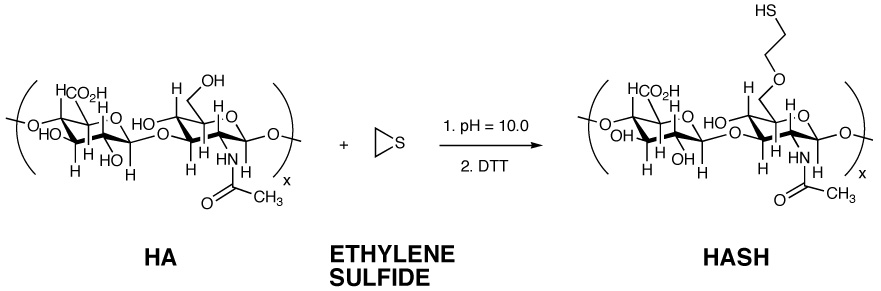

| Hyaluronan Bromoacetate (HABA)[42] |  |

| Hyaluronan Iodocetate (HAIA)[42] |  |

2.8. Cytotoxicity assay

Primary human tracheal scar fibroblasts (T31 cells) were seeded in a 96-well plate (seeding density was 12.5 × 103 cells/well in 100 µl) in DMEM/F12 +10% newborn calf serum + 2 mM L-glutamine + penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were allowed to recover and attach for 24 h at 37°C/5% CO2. The next day, the media was replaced with DMEM/F12 containing 1.5%, 1%, 0.6%, 0.2% and 0.1% HA and HASH, respectively. Cells were incubated for an additional 24 h and cell viability in the presence or absence of HASH was assessed using a previously described biochemical method [44]. The tetrazolium compound MTS (Cell-Titer 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega, Madison, WI) is reduced by metabolically active cells to yield a colored formazan product, and the absorption of the colored solution at 490 nm is proportional to the number of viable cells.

2.9. Chondrocyte culture and treatment

Articular chondrocytes were obtained from the knee joints of a 2-year old sheep immediately postmortem. The tissue was first minced then treated overnight with 0.1% type II collagenase. The isolated cells were then grown in DMEM/F12 + 10% FBS + penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C/5% CO2. The medium was changed at confluence to DMEM/F12 + 0.5% FBS + penicillin/streptomycin, for 6h. Subsequently, chondrocytes were treated with HA and HASH, respectively (0, 50, 100 and 200 µg/mL final concentrations). After 2h, H2O2 was added to the medium to a final concentration of 0.5 mM, for 24 h. As controls, chondrocytes were cultured in medium alone or medium plus H2O2.

2.10. Determination of apoptosis by flow cytometry analysis

The apoptotic rate of chondrocytes was evaluated with an Annexin V-FITC kit. After apoptosis induction, cells were washed twice with 1X PBS then were suspended in 1X binding buffer at a density of 106 cells/ml. Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide were used to stain cells, at room temperature for 15 min. Samples were further 5-fold diluted with 1X binding buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cell populations were identified as follows: intact (Annexin V-FITC−, propidium iodide−), early apoptotic (Annexin V-FITC+, propidium iodide−), late apoptotic and necrotic (Annexin V-FITC+, propidium iodide+).

2.11. Statistical analysis

The data is represented as the means ± standard deviation (S.D.) of the number of repeats. Values were compared using Student’s t-test (2-tailed) with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant and p < 0.005 considered highly significant.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of HA-sulfhydryl (HASH)

Thiolated HA derivatives were previously synthesized in our laboratory via hydrazide chemistry [34, 38, 39, 40, 45, 21, 22, 46]. This strategy targeted the glucuronic acid (GlcA) residues of GAG disaccharide units. The first step in the procedure involved the reaction of the GlcA carboxyl groups with 3,3’-di(thiopropionyl) bishydrazide) (DTP) in the presence of 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylamino)propyl]carbodiimide (EDCI). The resulting disulfide-containing GAGs were subsequently reduced with dithiothreitol (DTT) yielding the thiolated macromoleculates.

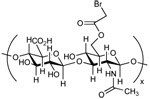

For the synthesis of HASH, the approach was to chemically alter the reactive primary hydroxyl group of the N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc) residues of HA by the nucleophilic opening of ethylene sulfide with alkoxides transiently formed at basic pH (Figure 1). This strategy is analogous to the base-mediated carboxymethylation of HA [47], or the partial crosslinking of HA using divinyl sulfone crosslinked HA or the reaction with 1,4-butanediol diglycidyl ether [12]. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was treated with DTT to reduce any residual disulfide bonds, followed by dialysis and lyophilization.

Figure 1.

Synthetic scheme and structure of HASH

While it is plausible to consider that the carboxylate could open the ethylene sulfide, this reaction is reversible. Any (2-thioethyl) ester formed would rapidly undergo beta-elimination, releasing the large, stable HA-carboxylate leaving group and reforming ethylene sulfide.

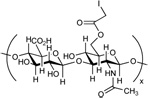

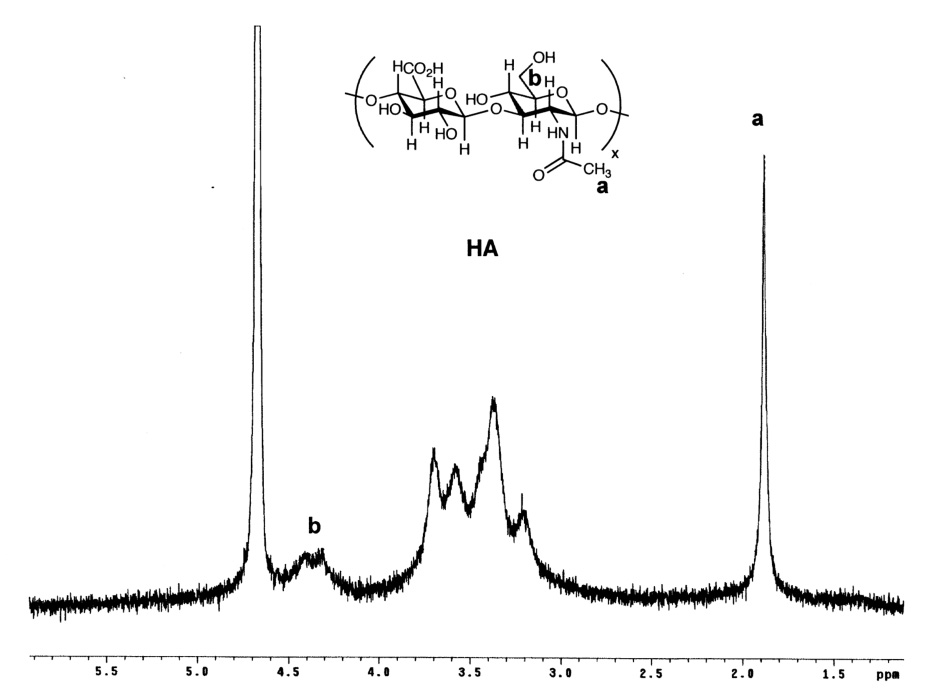

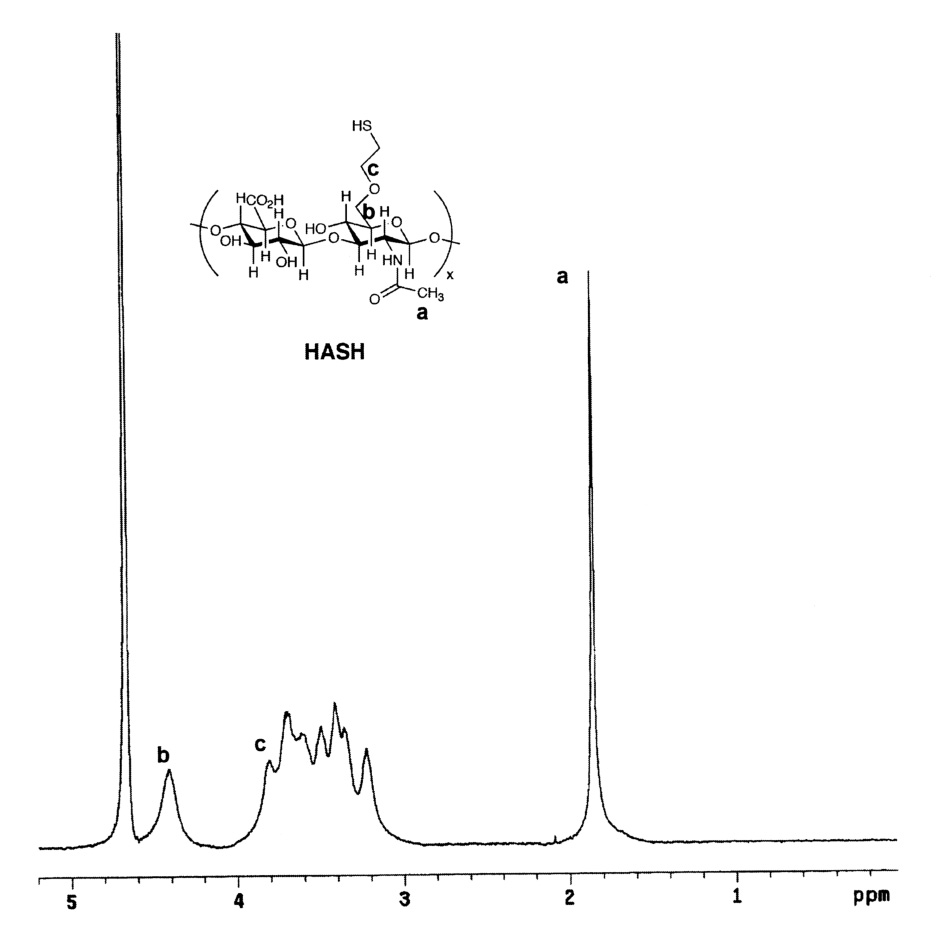

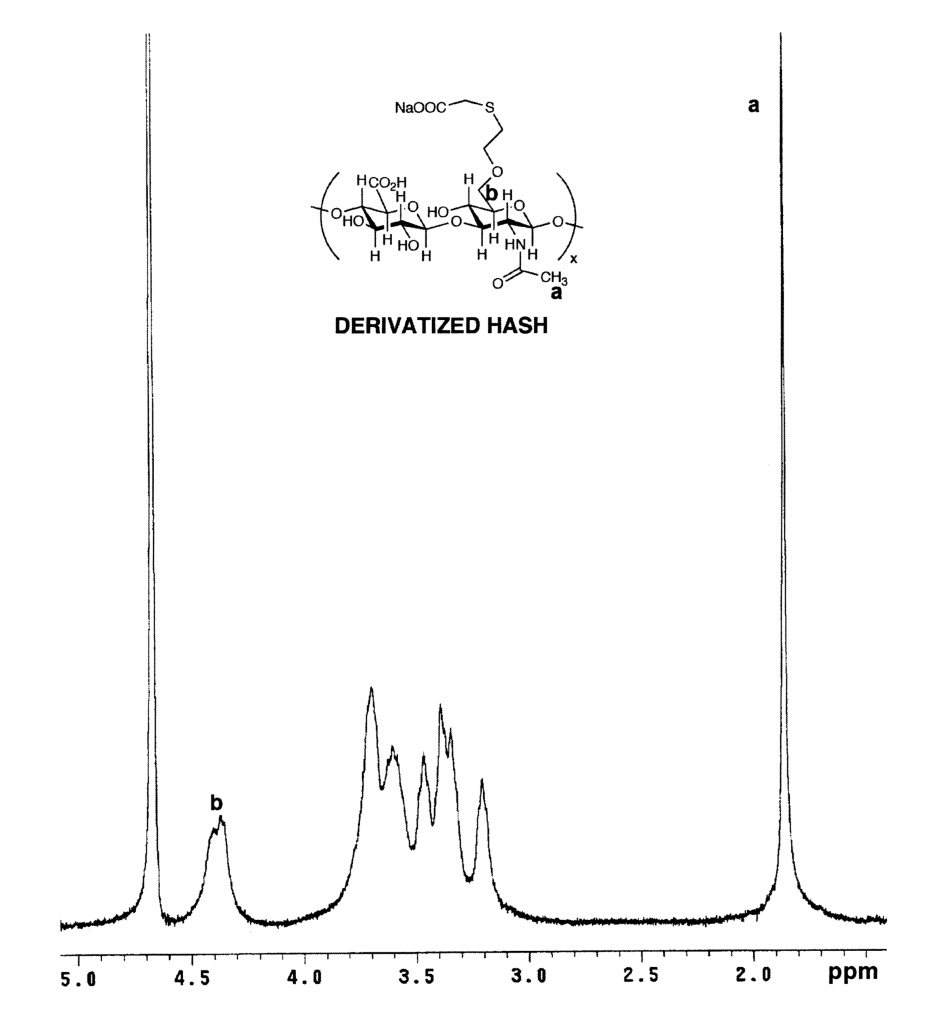

The structure of the new compound was verified by 1H-NMR (Figure 2). When compared to 1H-NMR spectrum of HA (Figure 2A), a peak corresponding to the methylene group attached to the former hydroxyl oxygen (-CH2-CH2-SH), appeared at δ = 3.82 ppm. The resonance for the second methylene group, closer to the thiol functionality (-CH2-CH2-SH) appears at δ = 3.69, but is overlapping with proton resonances corresponding to GlcA and GlcNAc protons from the 3–4 ppm region (Figure 2B). The integration of the methylene proton signals relative to the N-acetyl protons of GlcNAc could not be used to determine the degree of HA substitution due to the overlapping of the signals. Thus, a modified Ellman’s spectroscopic method was employed. The degree of thiolation was determined to be 4–14%. The purity and the molecular weight of HASH (MW ~ 180 kDa) were determined by GPC analysis (data not shown). The reduced molecular weight is the result of hydrolysis under the basic conditions used during the chemical modification.

Figure 2.

1H-NMR spectra in D2O. Panel A, HA; Panel B, HASH

3.2. Confirmation of thiol modification

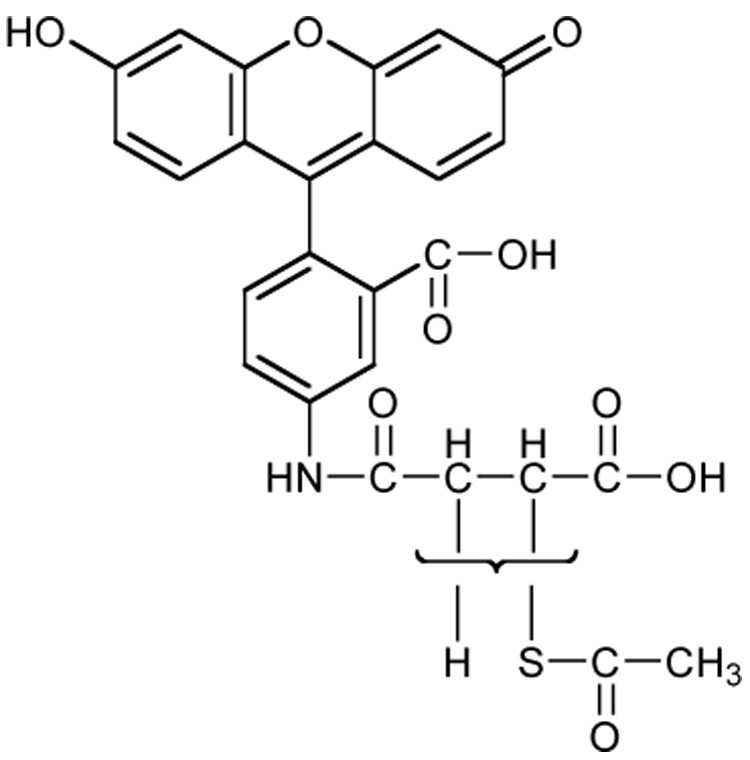

Due to the complexity of the polymer proton 1H-NMR spectra, three additional measures to demonstrate the desired chemical modification were employed. First, we used SAMSA fluorescein, a thiol group-containing fluorescent reagent, commonly used for assaying thiol-reactive maleimide and iodoacetamide moieties of proteins (Figure 3A), but also suitable for conducting a thiol-disulfide exchange reaction. Due to the ease of monitoring, this molecule was chosen to assess the presence and reactivity of the SH moieties of HASH. After conjugation of HA and HASH with SAMSA fluorescein and dialysis, the solutions were photographed under UV light (254 nm) to assess the fluorescence intensities (Figure 3, inset). The 412 nm absorbance values of the derivatized compounds were examined, showing that addition of the fluorescent dye to the new moieties occurred (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

SAMSA fluorescein derivatization of HASH. Panel A, Structure of SAMSA fluorescein; Panel B, A494 absorbance of SAMSA fluorescein derivatized HASH (*** p < 0.005, versus the HA control). Columns represent mean ± S.D., n = 4. Inset - fluorescence intensities of SAMSA derivatized solutions under UV light (254 nm).

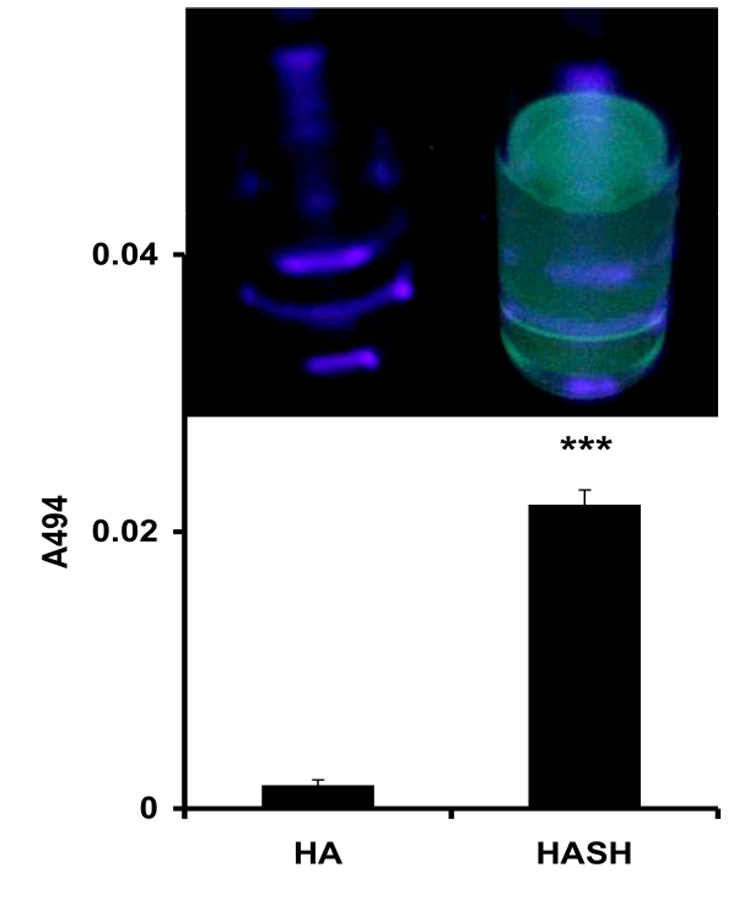

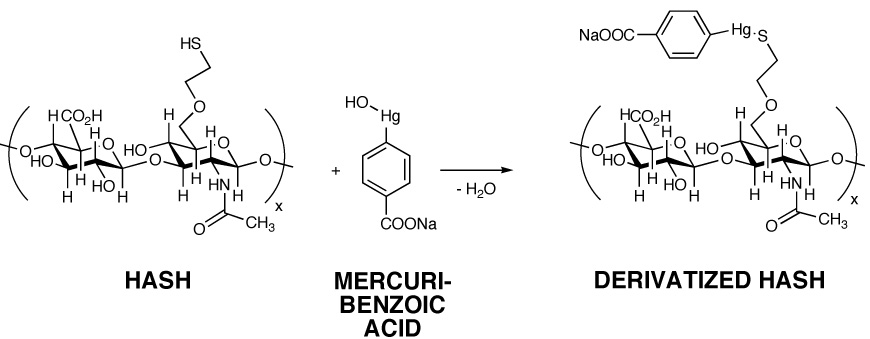

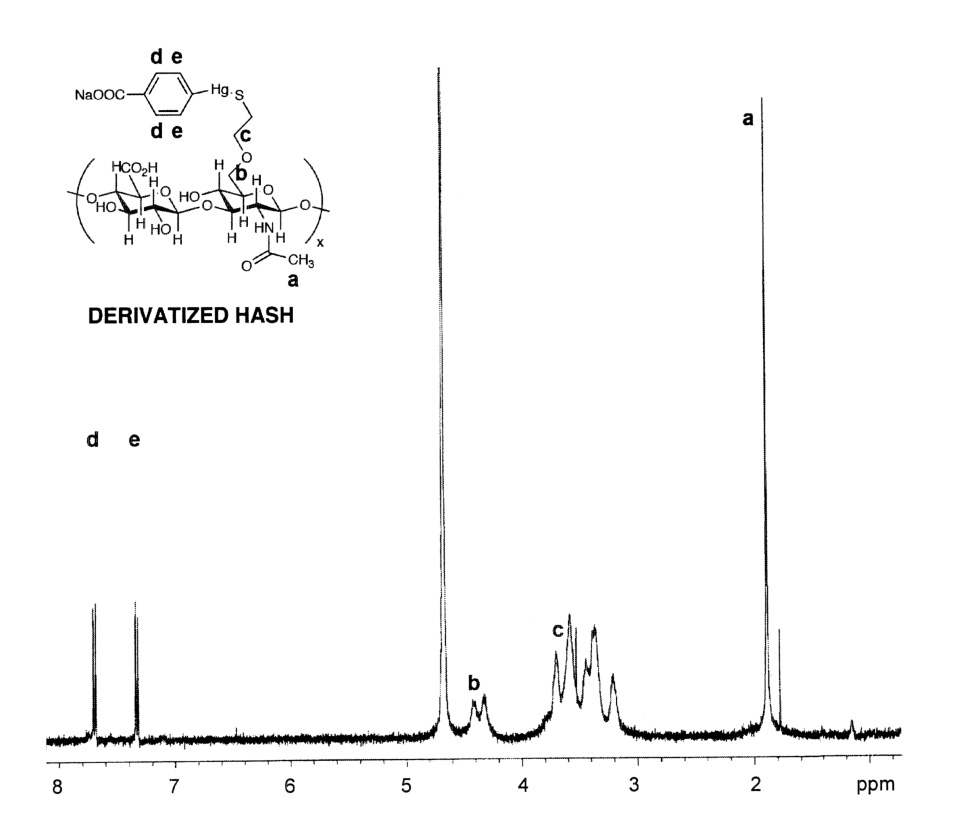

Second, we examined the reaction of a standard thiol-reactive reagent, 4-(hydroxymercuri)benzoic acid sodium salt, with HASH (Figure 4). This compound was selected because of the downfield aromatic proton resonances would provide well-resolved, sharp, characteristic signature peaks in the NMR, and took advantage of the high affinity and specificity of organomercury reagents for thiols. Upon completion of the reaction and removal of the unreacted, precipitated reagent, the conjugated HASH compound was analyzed by 1H-NMR (Figure 4). The two methylene protons of the thiol substituent (-CH2-CH2-SH) shifted upfield to the δ = 3–3.7 ppm region) and the resonances corresponding to the benzoic acid moiety (-C6H4-) appeared at δ = 7.4 and δ = 7.7 ppm.

Figure 4.

Reaction of HASH with sodium 4-(hydroxymercuri)benzoate. Panel A, Reaction scheme; Panel B, 1H-NMR spectrum of HASH-mercuribenzoate adduct

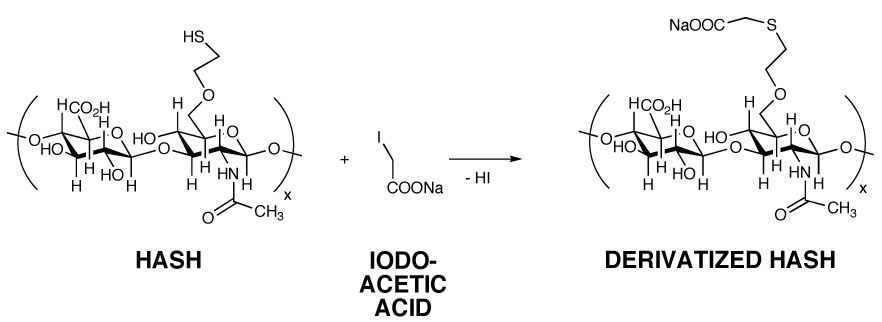

Third, we examined the reaction of HASH with sodium iodoacetate (Figure 5), a reagent commonly employed for “capping” cysteine residues of proteins prior to Edman degradation or proteolysis. As expected, this also resulted in an upfield shift of the methylene protons (-CH2-CH2-SH) (δ =3–3.7 ppm region). Altogether, these three reactions confirmed the presence of the thiol modification.

Figure 5.

Reaction of HASH with sodium iodoacetate. Panel A, Reaction scheme; Panel B, 1H-NMR spectrum of S-carboxymethyl HASH

3.3. Attempted crosslinking

The crosslinking of HASH was investigated with a wide spectrum of bivalent electrophilic crosslinkers (Table 1), as well as oxidative crosslinking in air and by using dilute hydrogen peroxide. To confirm the reactivity of the crosslinkers and to verify the optimal pH for gelation, thiol-derivatized carboxymethylated HA (CMHA-S) was used as positive control in all crosslinking experiments. As anticipated, the control CMHA-S solutions gelled in times ranging from 5 sec to 2 h, depending on the nature of the crosslinker and the pH of the solution. Next, two different HASH concentrations were used, and the HASH:crosslinker molar ratios ranging from 1:3 to 5:1 were evaluated. Surprisingly, no crosslinking was observed for HASH regardless of the pH of the solution, nature or ratio of crosslinker.

HASH features reactive thiols that were readily alkylated by the monovalent thiol reagents iodoacetate and p-hydroxymercuribenzoate, and underwent a thiol-disulfide exchange reaction with SAMSA-fluorescein. Thus, the inability to crosslink this polymeric polythiol was unexpected. Three explanations are plausible. First, the low degree of derivatization (4–14% in HASH versus 35–40% in CMHA-S) may be partially responsible for the inability to form a HASH hydrogel. However, we have observed that even 15% thiolation is adequate for gelation of CMHA-S. Second, the 2-thioethyl ether reaches only three atoms (-C-C-S) beyond the primary 6-hydroxyl group, in contrast to the seven (-C-C(O)-N-N-C-C-S) atom extension beyond the same OH group in CMHA-S. This would lead to significantly greater steric hinderance by the bulky HA scaffold, thus impeding access of a single bivalent crosslinker to two separate thioethyl ether sulfhydryl groups. Finally, the reactivity of the 2-thioethyl ether thiol group will be reduced relative to the thiol of the thiopropanoyl hydrazide. We earlier observed significant sensitivity to hydrogel formation between 3-thiopropanoyl hydrazide modified HA and 4-thiobutanoyl hydrazide-modified HA [21]. A difference of only 0.2 pKa units changed gelation rates over 10-fold.

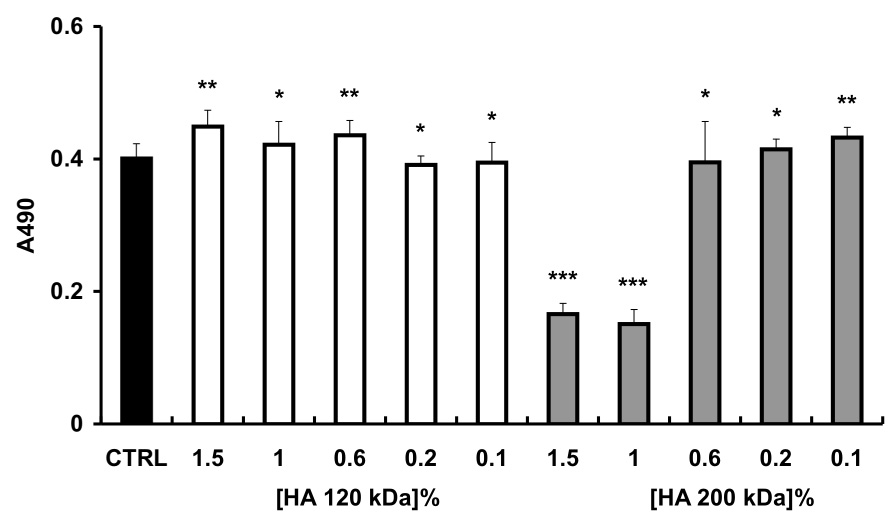

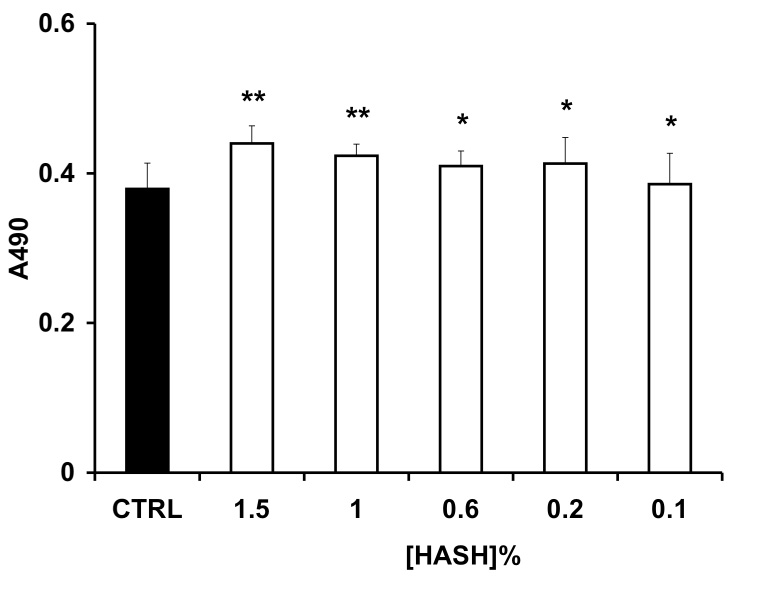

3.4. Cytocompatibility of HASH

T31 fibroblasts isolated from human tracheal scar were used to evaluate the cytocompatibility of HASH. These cells are derived from primary culture and were chosen because of their sensitivity to a variety of stressors. For this assay, the newborn calf serum and L-glutamine were excluded from the media to avoid the potential neutralization of HASH (Figure 6). As controls, two different molecular weight HAs were used (MW 120 and 200 kDa). The 120 kDa HA had no cytotoxic effect on fibroblasts regardless of the concentration used. In contrast, the 200 kDa HA was deleterious (p < 0.001) at high concentrations (0.6% to 1.5 w/v) but was well tolerated at low concentrations (0.2-0.1% w/v). This apparent toxicity was due to increased viscosity and the resulting reduction of nutrient diffusibility in the medium. At all concentrations, the effects of HASH were similar to those of the 120 kDa HA on T31 fibroblasts.

Figure 6.

Proliferation of T31 fibroblasts as determined by MTS assay. Panel A, with added 120 kDa HA (white) or 200 kDa HA (gray bars); Panel B, with added HASH. Each column represents the mean ± S.D., n= 6 (*** p < 0.005, ** p < 0.05 and * p > 0.05 versus the control group).

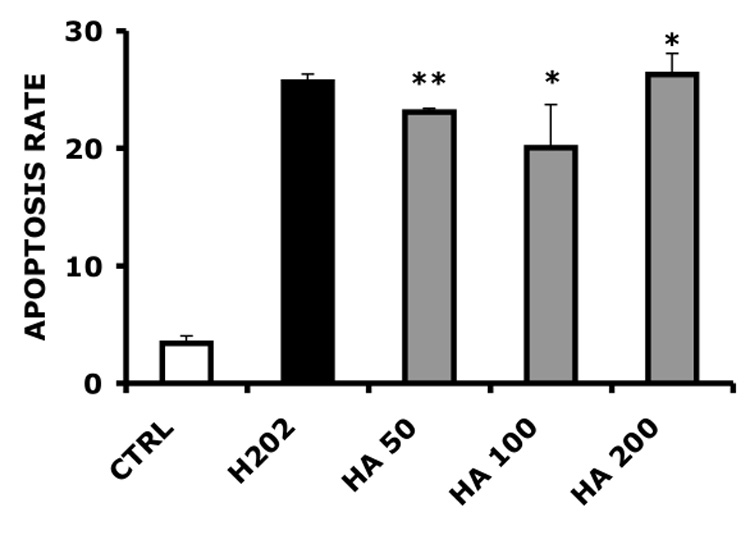

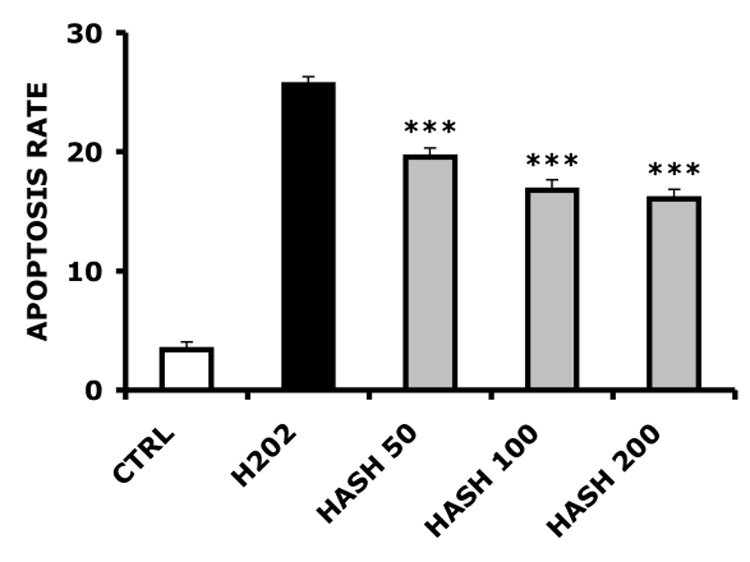

3.5. Chondroprotective effects of HASH

Next, we determined the effect of HASH on the apoptosis rates of freshly-harvested ovine articular chondrocytes treated with H2O2, and compared the effect of HASH with the effect of unmodified native 120 kDa HA (Figure 7). These experiments were modified from a method used to evaluate the protective effects of carboxymethyl-chitosan on rabbit chondrocytes exposed to interleukin-1b [48]. Samples treated with HA prior to oxidative stress by this surrogate reactive species showed slightly decreased apoptosis rates at 50 µg/mL HA, showing a modest but significant 10% decrease in apoptosis (p < 0.05). However, this effect was not dose dependent for unmodified HA, as neither 100 µg/mL nor 200 µg/mL significantly reduced chondrocytes apoptosis (p > 0.05). In contrast, HASH protected chondrocytes from reactive oxygen species in a dose dependent manner, with an approximately 40% decrease in the apoptotic rate at the highest concentration (200 µg/mL, p < 0.005).

Figure 7.

Primary ovine chondrocyte apoptosis rates induced by H2O2. Panel A, HA-treated chondrocytes; Panel B, HASH-treated chondrocytes (*** p < 0.005, ** p < 0.05 and * p > 0.05 versus the H2O2-only treated control group)

4. Discussion

Arthritis is used to generically refer to over one hundred pathological conditions that cause joint pain and inflammation. The two most common diseases responsible for the aforementioned symptoms are osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Osteoarthritis (OA), also know as degenerative arthritis, is caused by the wear and tear of the joints and affects over 20 million people in the United States [49]. OA affects particularly large weight-bearing, synovial joints. In contrast, RA is an autoimmune disease that causes inflammation and ultimately results in the destruction of cartilage and bone [50]. Anatomically, a synovial joint features a synovial membrane, cartilage, subchondral bone, synovial fluid and a joint capsule. In arthritis, the articular cartilage slowly degrades and ultimately disappears. However, changes also occur in the subchondral bone, the joint capsule and in the synovial fluid. High molecular weight hyaluronic acid (HA) is a major component of the synovial fluid. Conversely, in the synovial fluid of OA patients, the HA concentration is lower than normal, and the molecular weight distribution is shifted to a lower average mass [51]. The fragmentation of HA in the synovial fluid of arthritis patients can have implications beyond simple reduction of viscoelasticity, depending on the size of the HA fragments that are generated.

A major cause of HA degradation is the harmful action of reactive oxygen species (ROS) on this polymer [52], and two separate effects are synergistic in OA and RA. First, ROS causes strand scission of HA, leading to reduced molecular weight and accompanying reduced viscoelasticity of the synovial fluid. This can then exacerbate the inflammation due to the arthritis, and increased ROS production increases depolymerization, leading to increased levels of HA oligosaccharides. Thus, it is important to prevent HA degradation by ROS, and a number of small molecules, e.g., glutathione, ascorbic acid, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and carotenoids, have been proposed as additives based on their anti-oxidative effects [52]. These observations suggested that a thiolated derivative of HA might be chondroprotective by limiting the degradation of HA by ROS. In essence, a thiolated HA derivative could self-quench radicals that might otherwise result in scission of the polysaccharide backbone.

HA oligosaccharides or HA hexasaccharides were also found to induce nitric oxide synthase leading to increased production of nitric oxide in bovine articular chondrocytes (cartilage forming cells) [53]. NO is also capable of inducing and amplifying the ROS-induced strand scission of HA [52]. In cultures of human normal adult chondrocytes, HA oligosaccharide treatment led to the loss of proteoglycan (one of the extracellular matrix components) by induction of matrix metalloproteinase 13, through activation of NFkappaB and p38 MAP kinase [54]. Bovine articular chondrocytes were shown to undergo a dose-dependent chondrolysis when treated with HA oligosaccharides [55]. All these processes are associated with the progression and aggravation of arthritis.

Viscosupplementation is an intra-articular treatment option for arthritis that is targeted to restore the physiological viscoelasticity of the synovial fluid [56]. Viscosupplementation involves the injection of high molecular weight HA directly into the arthritis affected joint to alleviate the pain associated with OA. Patients receiving current treatments report pain reduction for up to 6 months, but some experience negligible pain relief. A number of large patient cohorts have been examined to determine the efficacy of intra-articular HA treatment in particular joints. For example, a systematic review of the safety and efficacy of HA injections for hip arthritis in eight clinical studies identified many problems in the trial protocols, including lack of control groups, inconsistent outcome measures, and overly short follow-up periods [56]. This review cautions against HA treatment without careful clinical supervision and only when all other treatments have failed [56]. On the other hand, analysis of five double-blind, randomized controlled trials for HA injections to treat OA of the knee found significant reduction of pain and increased function as compared to controls [57].

In general, one can attribute the mixed results to the poor biomechanical properties and rapid biodegradation of natural HA. Chemically-modified HA derivatives with longer in vivo residence times can yield even better clinical outcomes. However, a new paradigm might focus on the source of polymer degradation rather than simply treating the symptoms resulting from the degradation of HA. Such a paradigm would be to exploit a derivative of HA, such as HASH, which has the potential to reduce ROS action in the inflamed joint.

The experimental data presented herein indicate that HASH may have potential utility for arthritis treatment. Such an HA-based biomaterial would be biocompatible, well tolerated by cells, and readily injectable. The in vitro chondroprotective effects reported herein are further supported by preliminary results in vivo in a rat arthritis pilot study (G. Yang, unpublished results). The presence of the SH groups of HASH may act as radical scavengers, thus protecting cells from the damaging effects of reactive oxygen species. Because of the HA scaffold, it can also serve as a joint lubricant, thus encompassing a dual protective function. Since the HASH macromolecule is not readily crosslinkable via previously employed chemical crosslinking techniques [34, 38, 39, 40, 45, 21, 22, 46], it offers a non-gelling yet lubricious and radical-protective material for intra-articular injection. However, if needed, its structure could further be chemically crosslinked via other crosslinking strategies (i.e., divinyl sulfone or intra-molecular esterification crosslinking) [58, 59] that would preserve the availability of the free-radical scavenging thiol functionalities.

Conclusion

We showed here the chemical synthesis and characterization of a thiol containing HA derivative. The material obtained is not suitable for hydrogel formation via crosslinking. However, this macromolecule yields viscous solutions when dissolved in water, which makes it suitable for viscosupplementation-type applications. Most importantly, HASH may suggest a paradigm shift in OA treatment, as the experimental data points to it being a promising chondroprotective agent against oxidative stress and likely in reducing HA degradation by ROS.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the State of Utah Centers of Excellence Program and by NIH Grant 2 R01 DC04336 (to S. L. Thibeault and G.D. Prestwich).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fraser JR, Laurent TC, Laurent UB. Hyaluronan: its nature, distribution, functions and turnover. J Intern Med. 1997;242:27–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knudson CB, Knudson W. Cartilage proteoglycans. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12:69–78. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toole BP. Hyaluronan: from extracellular glue to pericellular cue. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:528–539. doi: 10.1038/nrc1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowthwaite GP, Edwards JC, Pitsillides AA. An essential role for the interaction between hyaluronan and hyaluronan binding proteins during joint development. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:641–651. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collis L, Hall C, Lange L, Ziebell M, Prestwich R, Turley EA. Rapid hyaluronan uptake is associated with enhanced motility: implications for an intracellular mode of action. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:444–449. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01505-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardwick C, Hoare K, Owens R, Hohn HP, Hook M, Moore D, Cripps V, et al. Molecular cloning of a novel hyaluronan receptor that mediates tumor cell motility. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:1343–1350. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.6.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toole BP. Hyaluronan in morphogenesis. J Intern Med. 1997;242:35–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerdin B, Hallgren R. Dynamic role of hyaluronan (HYA) in connective tissue activation and inflammation. J Intern Med. 1997;242:49–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saettone MF, Monti D, Torracca MT, Chetoni P. Mucoadhesive ophthalmic vehicles: evaluation of polymeric low-viscosity formulations. J Ocul Pharmacol. 1994;10:83–92. doi: 10.1089/jop.1994.10.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson JM, Nanney LB, Broadley KN, Whitsett JS, Aquino AM, Beccaro M, et al. Hyaluronate derivatives and their application to wound healing: preliminary observations. Clin Mater. 1991;8:171–177. doi: 10.1016/0267-6605(91)90027-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allison DD, Grande-Allen KJ. Review. Hyaluronan: a powerful tissue engineering tool. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2131–2140. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. In: Chemistry and Biology of Hyaluronan. Garg HG, Hales CA, editors. Amsterdam: Elsevier Press; 2004. pp. 475–504. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbucci R, Magnani A, Baszkin A, Da Costa ML, Bauser H, Hellwig G, Martuscelli E, et al. Physico-chemical surface characterization of hyaluronic acid derivatives as a new class of biomaterials. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 1993;4:245–273. doi: 10.1163/156856293x00555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campoccia D, Doherty P, Radice M, Brun P, Abatangelo G, Williams DF. Semisynthetic resorbable materials from hyaluronan esterification. Biomaterials. 1998;19:2101–2127. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo Y, Prestwich GD. Hyaluronic acid-N-hydroxysuccinimide: a useful intermediate for bioconjugation. Bioconjug Chem. 2001;12:1085–1088. doi: 10.1021/bc015513p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo Y, Ziebell MR, Prestwich GD. A hyaluronic acid-taxol antitumor bioconjugate targeted to cancer cells. Biomacromolecules. 2000;1:208–218. doi: 10.1021/bm000283n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pouyani T, Harbison GS, Prestwich GD. Novel hydrogels of hyaluronic acid: Synthesis, surface morfology, and solid-state NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:7515–7522. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gajewiak J, Cai S, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. Aminooxy pluronics: synthesis and preparation of glycosaminoglycan adducts. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:1781–1789. doi: 10.1021/bm060111b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, Liu Y, Shu XZ, Gray SD, Prestwich GD. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a cross-linked hyaluronan-mitomycin C hydrogel. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:895–902. doi: 10.1021/bm034463j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Li H, Shu XZ, Gray SD, Prestwich GD. Crosslinked hyaluronan hydrogels containing mitomycin C reduce postoperative abdominal adhesions. Fertil Sterill. 2005;83 Suppl 1:1275–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shu XZ, Liu Y, Luo Y, Roberts MC, Prestwich GD. Disulfide cross-linked hyaluronan hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:1304–1311. doi: 10.1021/bm025603c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shu XZ, Liu Y, Palumbo F, Prestwich GD. Disulfide-crosslinked hyaluronan-gelatin hydrogel films: a covalent mimic of the extracellular matrix for in vitro cell growth. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3825–3834. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leach JB, Bivens KA, Patrick CW., Jr Photocrosslinked hyaluronic acid gels: natural, biodegradable tissue engineering scaffolds. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2003;82:578–589. doi: 10.1002/bit.10605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abatangelo G, Barbucci R, Brun P, Lamponi S. Biocompatibility and enzymatic degradation studies on sulphated hyaluronic acid derivatives. Biomaterials. 1997;18:1411–1415. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen G, Ito Y, Imanishi Y, Magnani A, Lamponi S, Barbucci R. Photoimmobilization of sulfated hyaluronic acid for antithrombogenicity. Bioconjug Chem. 1997;8:730–734. doi: 10.1021/bc9700493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magnani A, Albanese A, Lamponi S, Barbucci R. Blood-interaction performance of differently sulphated hyaluronic acids. Thromb Res. 1996;81:383–395. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(96)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnani A, Barbucci R, Montanaro L, Arciola CR, Lamponi S. In vitro study of blood-contacting properties and effect on bacterial adhesion of a polymeric surface with immobilized heparin and sulphated hyaluronic acid. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2000;11:801–815. doi: 10.1163/156856200744020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu LS, Ng CK, Thompson AY, Poser JW, Spiro RC. Hyaluronate-heparin conjugate gels for the delivery of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;62:128–135. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu LS, Thompson AY, Heidaran MA, Poser JW, Spiro RC. An osteoconductive collagen/hyaluronate matrix for bone regeneration. Biomaterials. 1999;20:1097–1108. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coradini D, Pellizzaro C, Miglierini G, Daidone MG, Perbellini A. Hyaluronic acid as drug delivery for sodium butyrate: improvement of the anti-proliferative activity on a breast-cancer cell line. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:411–416. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990505)81:3<411::aid-ijc15>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inukai M, Jin Y, Yomota C, Yonese M. Preparation and characterization of hyaluronate-hydroxyethyl acrylate blend hydrogel for controlled release device. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2000;48:850–854. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin Y, Yamanaka J, Sato S, Miyata I, Yomota C, Yonese M. Recyclable characteristics of hyaluronate-polyhydroxyethyl acrylate blend hydrogel for controlled releases. J Control Release. 2001;73:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Axen R, Porath J, Ernback S. Chemical coupling of peptides and proteins to polysaccharides by means of cyanogen halides. Nature. 1967;214:1302–1304. doi: 10.1038/2141302a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai S, Liu Y, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. Injectable glycosaminoglycan hydrogels for controlled release of human basic fibroblast growth factor. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6054–6067. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen JK, Thibeault SL, Walsh JF, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. In vivo engineering of the vocal fold extracellular matrix with injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogels: early effects on tissue repair and biomechanics in a rabbit model. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114:662–670. doi: 10.1177/000348940511400902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shu XZ, Ghosh K, Liu Y, Palumbo FS, Luo Y, Clark RA, et al. Attachment and spreading of fibroblasts on an RGD peptide-modified injectable hyaluronan hydrogel. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;68:365–375. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duflo S, Thibeault SL, Li W, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. Vocal Fold Tissue Repair in Vivo Using a Synthetic Extracellular Matrix. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1–10. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Ahmad S, Shu XZ, Sanders RK, Kopesec SA, Prestwich GD. Accelerated repair of cortical bone defects using a synthetic extracellular matrix to deliver human demineralized bone matrix. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1454–1462. doi: 10.1002/jor.20148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Shu XZ, Gray SD, Prestwich GD. Disulfide-crosslinked hyaluronan-gelatin sponge: growth of fibrous tissue in vivo. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;68:142–149. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. Biocompatibility and stability of disulfide-crosslinked hyaluronan films. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4737–4746. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo Y, Prestwich GD. Synthesis and selective cytotoxicity of a hyaluronic acid-antitumor bioconjugate. Bioconjug Chem. 1999;10:755–763. doi: 10.1021/bc9900338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serban MA, Prestwich GD. Synthesis of hyaluronan haloacetates and biology of novel cross-linker-free synthetic extracellular matrix hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:2821–2828. doi: 10.1021/bm700595s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vanderhooft JL, Mann BK, Prestwich GD. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Thiol-Reactive Poly(ethylene glycol) Cross-Linkers for Extracellular-Matrix-Mimetic Biomaterials. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:2883–2889. doi: 10.1021/bm0703564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin VS, Lee MC, O'Neal S, McKean J, Sung KL. Ligament tissue engineering using synthetic biodegradable fiber scaffolds. Tissue Eng. 1999;5:443–452. doi: 10.1089/ten.1999.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shu XZ, Ahmad S, Liu Y, Prestwich GD. Synthesis and evaluation of injectable, in situ crosslinkable synthetic extracellular matrices for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;79:902–912. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shu XZ, Liu Y, Palumbo FS, Luo Y, Prestwich GD. In situ crosslinkable hyaluronan hydrogels for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1339–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prestwich GD. Evaluating Drug Efficacy and Toxicology in Three Dimensions: Using Synthetic Extracellular Matrices in Drug Discovery. Acc Chem Res. 2007 doi: 10.1021/ar7000827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Q, Liu SQ, Du YM, Peng H, Sun LP. Carboxymethyl-chitosan protects rabbit chondrocytes from interleukin-1beta-induced apoptosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;541:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glass GG, Osteoarthritis Dis Mon. 2006;52:343–362. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weissmann G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2006;64:12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balazs E. In: Disorders of the Knee. Helfet AJ, editor. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott; 1982. pp. 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soltes L, Mendichi R, Kogan G, Schiller J, Stankovska M, Arnhold J. Degradative action of reactive oxygen species on hyaluronan. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:659–668. doi: 10.1021/bm050867v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iacob S, Knudson CB. Hyaluronan fragments activate nitric oxide synthase and the production of nitric oxide by articular chondrocytes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohno S, Im HJ, Knudson CB, Knudson W. Hyaluronan oligosaccharides induce matrix metalloproteinase 13 via transcriptional activation of NFkappaB and p38 MAP kinase in articular chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17952–17960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602750200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knudson W, Casey B, Nishida Y, Eger W, Kuettner KE, Knudson CB. Hyaluronan oligosaccharides perturb cartilage matrix homeostasis and induce chondrocytic chondrolysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1165–1174. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<1165::AID-ANR27>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandez Lopez JC, Ruano-Ravina A. Efficacy and safety of intraarticular hyaluronic acid in the treatment of hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:1306–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strand V, Conaghan PG, Lohmander LS, Koutsoukos AD, Hurley FL, Bird H, et al. An integrated analysis of five double-blind, randomized controlled trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of a hyaluronan product for intra-articular injection in osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:859–866. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Iaco PA, Stefanetti M, Pressato D, Piana S, Dona M, Pavesio A, et al. A novel hyaluronan-based gel in laparoscopic adhesion prevention: preclinical evaluation in an animal model. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:318–323. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00496-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Larsen NE, Pollak CT, Reiner K, Leshchiner E, Balazs EA. Hylan gel biomaterial: dermal and immunologic compatibility. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27:1129–1134. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820270903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]