Abstract

Nucleic acid-templated chemistry is a promising strategy for imaging genetic sequences in living cells. Here we describe the synthesis of two new nucleophiles for use in templated nucleophilic displacements with DNA probes. The nucleophilic groups are phosphorodithioate and phosphorotrithioate; we report on synthetic methods for introducing these groups at the 3′-terminus of oligonucleotides. Both new nucleophiles are found to be more highly reactive than earlier phosphoromonothioates. This increased nucleophilicity is shown to result in more rapid templated reactions with electrophilic DNA probes. The new probes were demonstrated in detection of specific genetic sequences in solution, with clear signal over background being generated in as little as 20 min. The probes were also tested for imaging ribosomal RNA sequences in live E. coli; useful signal was generated in 20 min to one hour, approximately one quarter to one-half the time of earlier monothioate probes, and the signal-to-noise ratio was increased as well.

Keywords: fluorescence, autoligation, quenched probe, E. coli, ribosomal RNA

Introduction

Nucleic acid templated chemistry has been studied recently for a number of applications in chemistry and biology.1–31 The earliest examples of templated chemistries were directed at modeling the replication of DNA and RNA under prebiotic conditions,1–3 and were also developed as synthetic methods for assembling larger gene fragments from oligonucleotides.4–6 More recently, DNA-templated chemistry has been studied as a tool for encoded assembly of molecules,7,8 and as part of reaction discovery processes.9–13 In addition to these applications, a major emphasis has been on the use of templated chemistry in the detection or identification of genetic sequences in solution.14–31

Our own research in nucleic acid templated chemistry has focused recently on detection of RNAs directly in cells.20,21,32,33 This application is potentially important for rapid identification of pathogenic bacteria and for identification of disease-related messenger RNAs in human cells. We have previously described nucleophilic chemistry for templated ligations of modified DNA probes,17,19 and have developed quencher-based leaving groups that yield a fluorescent signal upon reaction.32 We also developed a product destabilization strategy for engendering turnover of reactive probes on a template, thus yielding amplification of signal.21

With DNA or RNA detection as a focus, the large majority of nucleic acid-templated reactions have involved chemical joining of a pair of probes. In most cases this chemistry has made use of nucleophilic additions or displacements.14–28 This fact brings up a practical issue in solution detection of DNA and RNA: namely, the rate of reaction. Rate of reaction can determine the practicality of a detection method, by defining the length of an incubation period before signal can be read, and by affecting signal-to-background ratios. In nucleophilic displacements this rate is governed in part by the reactivity of the electrophile (and associated leaving group ability). However, in practical applications, electrophilicity cannot be increased too much, for two reasons: first, water may act as an unwanted nucleophile, giving an interfering background signal. Second, strong electrophiles can be rapidly degraded by the basic conditions of DNA deprotection after probe synthesis.6,14,30

For these reasons, investigations into a second approach for increasing reactivity - namely, increasing the reactivity of the nucleophile - is justified.31 Not only are strong nucleophiles compatible with common DNA synthesis protocols, but they are also more compatible with the chemistry of biomolecules. For example, proteins and nucleic acids can readily react with strongly electrophilic species, but not as easily with nucleophiles. Thus highly nucleophilic groups may remain functional even in living cells.

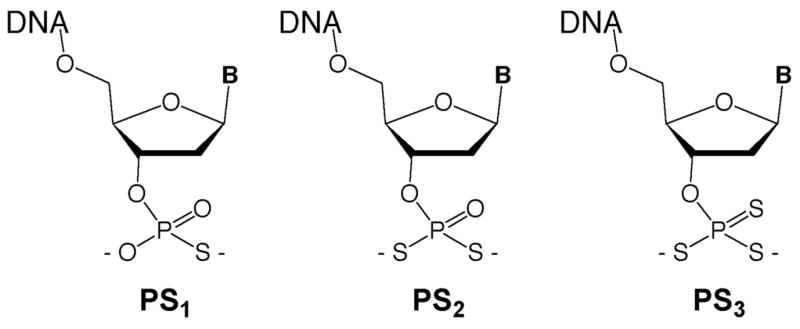

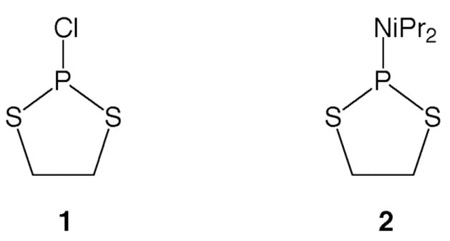

We describe here the synthesis and reactive properties of new and highly nucleophilic phosphorodithioate and phosphorotrithioate groups conjugated to DNA. In past work, terminal phosphoromonothioate groups on oligonucleotides have been common nucleophiles used in DNA-templated chemistry.15,17,28 They are highly reactive, since they present an anionic sulfur as the nucleophilic atom. In addition, they are readily prepared during DNA synthesis using commercial sulfurization reagents.34,35 We considered the possibility that increasing sulfur substitution from one S to two or three (Fig. 1) might increase the nucleophilic reactivity of such a terminal nucleophile. Phosphorodithioate (PS2) diesters are well characterized as linking groups in oligonucleotides,36–38 but have not, to our knowledge, been described as terminally substituted monoesters in oligonucleotides. Phosphorotrithioates (PS3) were apparently unknown either with internal or terminal substitution in DNA. After experimentation with a number of synthetic approaches, we report that both groups can be readily installed at the terminus of oligonucleotides using on-column chemistry. Experiments show that the new nucleophiles do, in fact, have increased reactivity toward an electrophilic probe in nucleic acid-templated chemistry. Finally, we show that probes containing these groups can be used in living bacterial cells to detect RNA sequences more rapidly, and with better signal-to-noise, than earlier probe chemistries.

Figure 1.

Structures of phosphoromono-, di-, and tri-thioate esters at the 3′-terminus of oligodeoxynucleotides. The nucleophilic sulfur groups are installed on-column following reverse DNA synthesis.

Results

Synthesis strategy

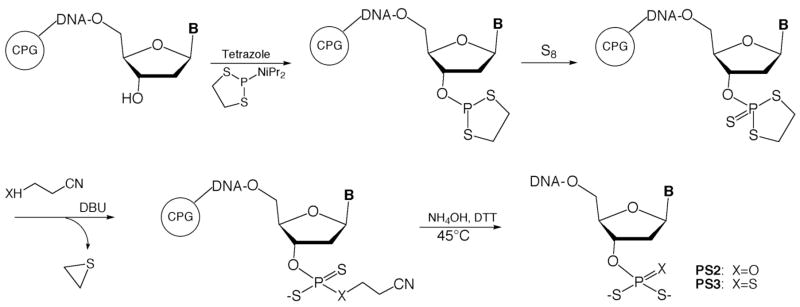

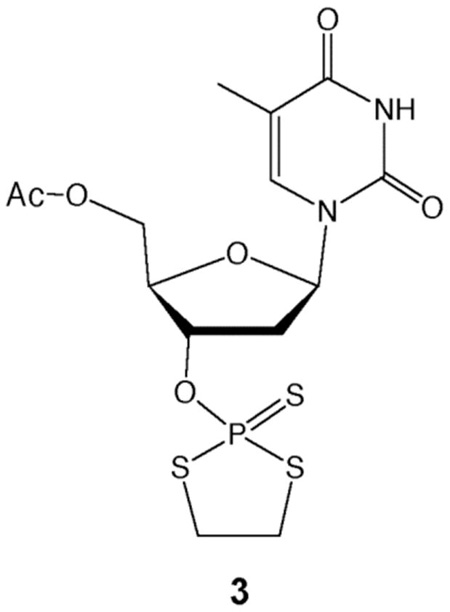

Previously, Okruszek et al. developed a method to introduce nonbridging internucleotide PS2 groups using the dithiaphospholane reagents 1 or 2.39, 40 In one report, they demonstrated that 3′- and 5′-PS2 mononucleotides could be prepared in solution,41 although the terminal phosphorodithioates were not incorporated into oligonucleotides. We chose to adapt the Okruszek dithiaphospholane approach to generate both 3′-PS2 and 3′-PS3 functionalized oligonucleotides directly on the DNA synthesis column following oligonucleotide synthesis. In this strategy, oligonucleotides would be synthesized using commercially available 5′-phosphoramidites in the reverse (5′ to 3′) direction. Following addition of the final 3′-base, the dithiaphospholane could be installed using 1 or 2, followed by sulfurization to the P(V) 3′-O-(2-thio-1,3,2-dithiaphospholane) (Scheme 1). Treatment with the base DBU in the presence of 3-hydroxypropionitrile or 3-mercaptopropionitrile should provide the 3′-terminal cyanoethyl protected PS2 or PS3 groups, respectively. Normal cleavage and deprotection conditions using NH4OH should then yield the 3′-PS2 or PS3 modified oligonucleotides.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 3′-terminal phosphorodithioate (PS2) and trithioate (PS3) groups on an oligodeoxynucleotide.

Initial reactions of 1 with the trimer dTTT-OH provided inconsistent results when performed on solid support. Reactions of 1 with 5′-O-acetylthymidine were therefore performed in solution and followed by 31P NMR. It was found that when a tertiary amine was added to 1, unsatisfactory mixtures of five new products were immediately formed. We therefore synthesized 2 which was used for all further reactions and provided much more consistent results. When controlled pore glass (CPG)-bound dTTT-OH was reacted with 2 in the presence of tetrazole, followed by sulfurization with elemental sulfur, the desired 3′-dithiaphospholane was obtained. Following sulfurization, CPG support was incubated in 0.5 M 3-hydroxypropionitrile with 1.5 M DBU for 5 min to effect cyanoethoxide addition and subsequent ethylene sulfide elimination.42 The resin was then rinsed with CH3CN and subjected to standard cleavage/deprotection conditions in the presence of dithiothreitol (DTT). HPLC analysis revealed a major peak with a retention time consistent for the phosphorodithioate; mass spectrometric analysis revealed the phosphorodithioate-substituted dTTT trimer had indeed been formed.

Subsequent reactions using 3-mercaptopropionitrile instead of 3-hydroxypropionitrile produced a peak in the HPLC chromatogram consistent with the phosphorotrithioate, but repeated attempts to confirm its presence by MS revealed only a peak for the starting material, dTTT-OH. Analogous solution-phase reactions were performed using 5′-O-acetyl-3′-O-(2-thio-1,3,2-dithiaphospholane)-thymidine, 3, and were monitored by 31P NMR. Addition of 3-mercaptopropionitrile and DBU resulted in complete conversion to a new product in less than one minute, which was confirmed as the cyanoethyl-protected phosphorotrithioate by mass spectrometry. Treatment of this intermediate with concentrated NH4OH at 60 °C resulted in the formation of a new product with an HPLC retention time consistent with the phosphorotrithioate. Mass spectral analysis revealed that the desired dT-PS3 product had been formed.

Previous reports noted that phosphorodithioate monoesters are unstable at lower pH.41, 43 Suspecting the phosphorotrithioates might be unstable at neutral pH after extended periods, we again attempted to prepare dTTT-PS3 on the synthesis column and quickly purified and analyzed the suspected dTTT-PS3 product by ESI mass spectrometry. Purified samples stored in pH neutral and pH 9.0 buffers revealed an ion peak corresponding to dTTT-PS3. However, HPLC analysis of the pH neutral sample was again performed 14 h after the sample was initially isolated, and it was found that 40% of the dTTT-PS3 had decomposed to the dTTT-OH starting material. The sample stored at pH 9 showed no decomposition. Yields were later found to improve significantly for both PS2 and PS3 oligonucleotides when deprotection and cleavage were carried out at 45 °C for 3 h in the presence of DTT.

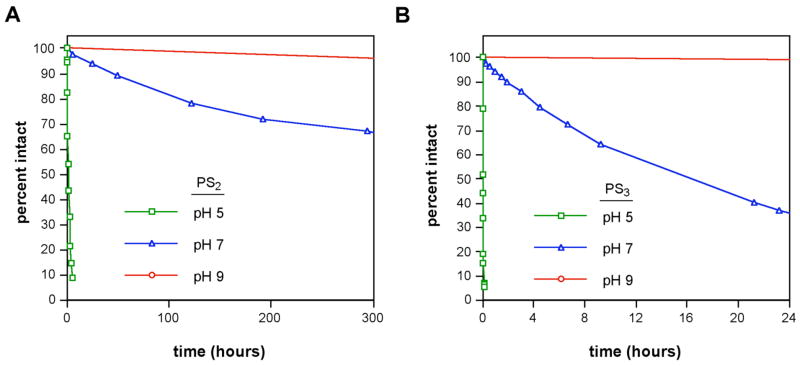

Analysis of aqueous stability

The rapid decomposition observed in these initial studies of the phosphorotrithioate prompted us to conduct more detailed experiments on the pH dependence of hydrolysis of phosphorothioates, -dithioates, and -trithioates. The thymidine monomers of the 3′-phosphorothioate (dT-PS1), 3′-phosphorodithioate (dT-PS2), and 3′-phosphorotrithioate (dT-PS3) were chosen as the model compounds for this study. dT-PS2 and dT-PS3 were prepared from 3 and dT-PS1 was prepared on a DNA synthesis column using standard methods (see Experimental section). All stock samples were purified by anion exchange HPLC in pH 9.0 Tris buffer and stored in the buffer at −80 °C until used in the stability studies. Each experiment was initiated by addition of a quantity of dT-PSx sample to a pH-adjusted incubation buffer. Aliquots were removed at multiple time points, and the samples were immediately analyzed by RP-HPLC. dT-PS1, dT-PS2, and dT-PS3 were tested at pH 5.0, 7.0, and 9.0 at room temperature. To test effects of varied temperature, similar experiments were conducted at pH 7.0 and 9.0 at 4 °C, −20 °C, and −80 °C.

The stability studies revealed (Table 1, Fig. 2) that dT-PS1 was quite stable at all three pH values tested, with half-lives of approximately four months, six months, and greater than three years at pH 5.0, 7.0, and 9.0 respectively. Both the phosphorodithioates and phosphorotrithioates, on the other hand, were significantly less stable and were increasingly sensitive at lower pH values. At room temperature, dT-PS2 displayed half-lives of 85 min, 25 days, and approximately four months at pH 5.0, 7.0, and 9.0, respectively. dT-PS3 was significantly less stable, having completely decomposed at pH 5.0 in less than ten minutes (t1/2≈1.5 min). At pH 7.0, the half-life increased to 14 h, and at pH 9.0, dT-PS3 displayed a half-life of six weeks. Although both PS2 and PS3 decomposed appreciably at neutral pH over a number of hours, it was found that samples stored at −20 °C or −80 °C were quite stable. After six months, dT-PS2 showed no decomposition at either temperature, while dT-PS3 remained largely intact (87%) at −20 °C and was completely stable at −80 °C. Finally, at pH 9.0, all samples stored at either −20 °C or −80 °C showed no measurable decomposition after six months.

Table 1.

pH and temperature effects on stability of 3′ terminal PS2 and PS3 groups in DNA

| Half-lives of dT-PSx at room temperature | ||||

| 5.0 | 7.0 | 9.0 | ||

| PS1 | ~4 months | ~6 months | >3 years | |

| PS2 | 85 minutes | 25 days | ~4 months | |

| PS3 | ~1.5 minutes | 14 hours | 6 weeks | |

| Percent dT-PSx remaining after 6 months, pH 7.0 | ||||

| RT | 4°C | −20°C | −80°C | |

| PS1 | 48 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| PS2 | 0 | 76 | 100 | 100 |

| PS3 | 0 | 0 | 87 | 100 |

| Percent dT-PSx remaining after 6 months, pH 9.0 | ||||

| RT | 4°C | −20°C | −80°C | |

| PS1 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| PS2 | 37 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| PS3 | 4 | 74 | 100 | 100 |

Figure 2.

Aqueous stability of 3′-terminal phosphorodithioate (dT-PS2, A) and phosphorotrithioate (dT-PS3, B) groups as a function of varied pH (22 °C). Percent intact compound was monitored by reverse-phase HPLC.

DNA-templated ligations in solution

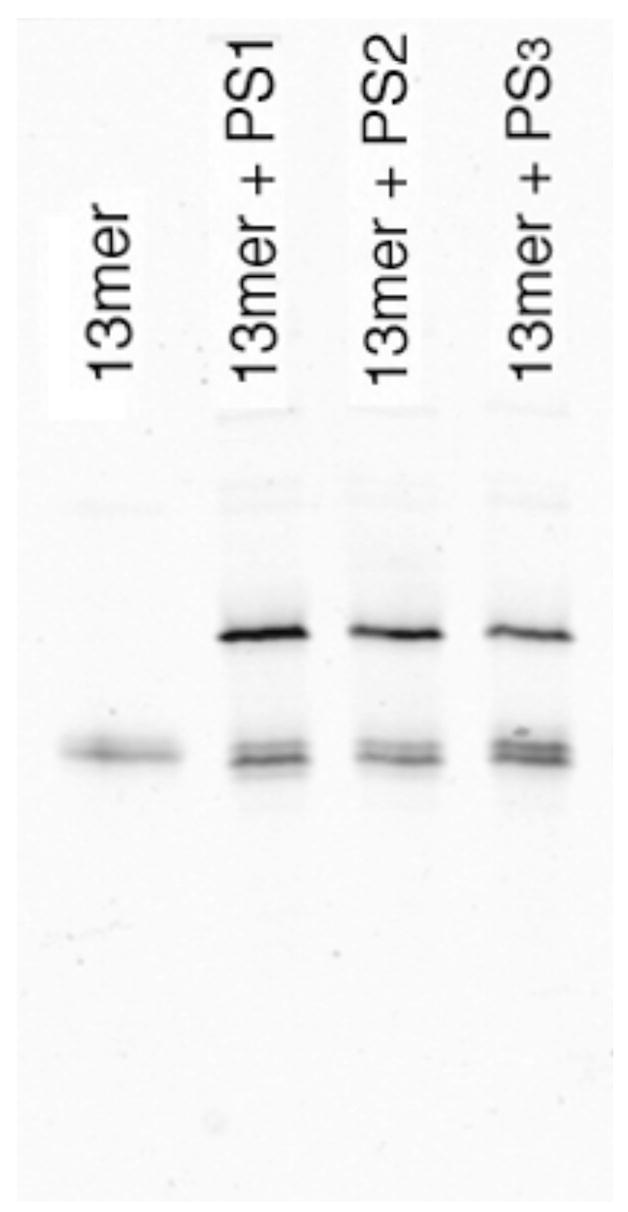

We then carried out experiments to measure whether the new sulfur nucleophiles would be active in templated reactions with electrophilic DNA probes. The electrophilic probes studied carried a fluorescein label and a dabsylate quencher/leaving group with universal linker,18,21 and were thus designed to increase fluorescence upon nucleophilic displacement of the dabsylate. Initial gel-based experiments using 3′-PS1-, PS2-, or PS3-terminated heptamers and a 5′-dabsylated 13mer in the presence of a complementary template confirmed that both new nucleophilic probes ligated with yields similar to previous PS1 probes (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Gel-based confirmation of ligations with phosphoro-monothioate (PS1), -dithioate (PS2) and –trithioate (PS3) nucleophilic probes. Lower bands are 13nt electrophilic probes; upper bands correspond to ligated 20mer products. Ligation conditions: 10 μM template and dabsyl probe, 20 μM phsphoro-monothioate, -dithioate, or –trithioate at 22°C in 10 mM Tris borate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 100 μM DTT. Reactions were loaded on the gel after 1 h. Products were imaged by fluorescence using a phosphorimager.

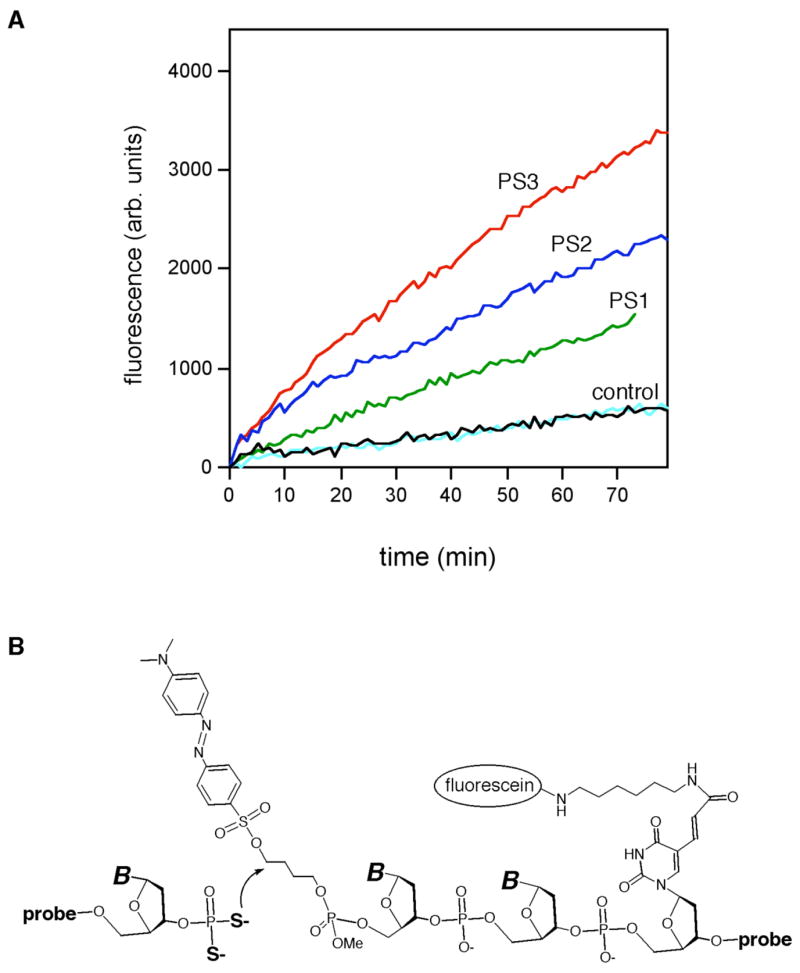

We then evaluated relative rates of the ligation reactions. To generate observable reaction-dependent signal, the dabsylate-quenched electrophilic probe contained a fluorescein label conjugated to a thymine two bases removed from the 5′-end (see Experimental section). Ligation reactions contained 100 nM each of dabsyl probe and complementary DNA template and 200 nM phosphorothioate probe. Reaction progress was monitored by measuring fluorescence emission at 518 nm (λex=494 nm) at 22 °C. The time-dependent data revealed that PS2 and PS3 heptamers reacted at approximately twice and three times the rate of PS1 heptamers, respectively (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

DNA-templated ligation reactions in solution using mono-, di-, and tri-thioate nucleophiles. (A) Timecourse of reactions as monitored by fluorescence. Ligation conditions: 100 nM dabsyl probe and template, 200 nM phosphoro-monothioate, -dithioate, or –trithioate heptamers at 22°C in 10 mM Tris borate buffer (pH 7.4) with 10 mM MgCl2 and 1 μM DTT. Controls omitted the nucleophilic probe, either in the presence of 100 μM DTT (black) or without DTT (cyan). (B) Mechanism of displacement of dabsylate quencher by probe with 3′-terminal nucleophile.

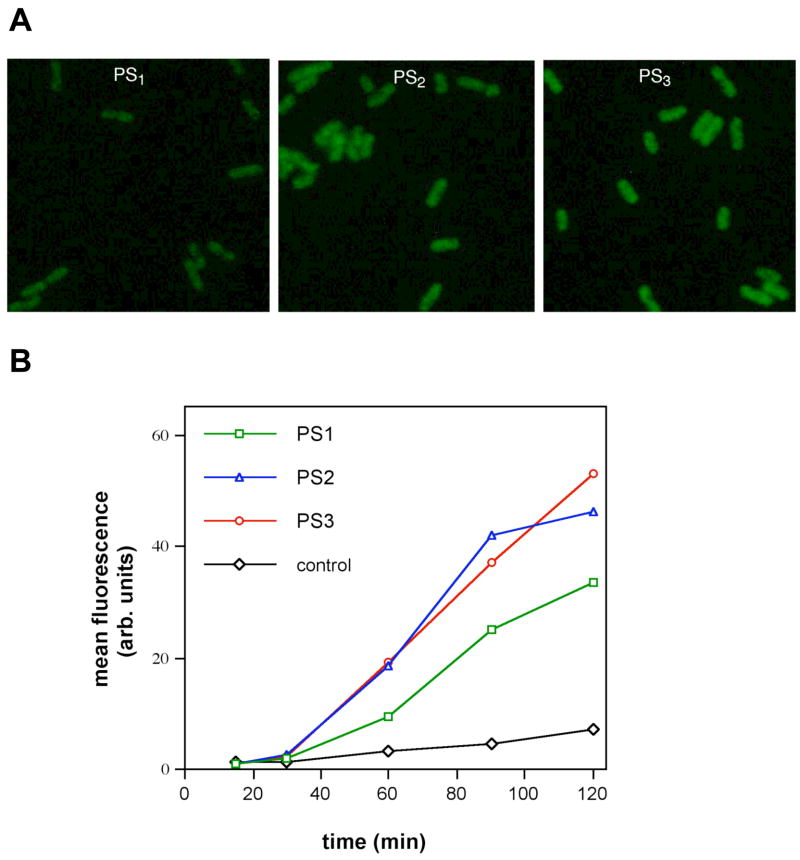

Testing intracellular application in RNA detection

Having confirmed nucleophilic ligation reactions with PS2 and PS3 probes in solution, we then tested whether these probes could also be used in intact bacteria, and whether they offered any advantage in RNA detection over the earlier phosphoromonothioates.32,33 We selected a 16S ribosomal RNA target sequence previously shown to give bright signal using PS1 probes,33 and prepared phosphorodithioate, and -trithioate probes for comparison. Escherichia coli cells were treated with nucleophile probes, dabsylate-substituted electrophilic probes, and “helper” DNAs (which bind adjacent to the fluorescent probes and apparently help increase site accessibility44) in high salt buffer with 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 37 °C. Fluorescence was monitored at various time points by microscopy and flow cytometry. No washing steps were carried out, and the cells were examined directly in the incubation solution.

The data showed that weak signals began to be observable under the microscope after 30 minutes with the new probes, and fairly bright signal was seen after 60 minutes (Fig. 5). Examination of the signals by eye (Fig. 5A) suggested brighter signals for the PS2 and PS3 probes. For quantitation, analysis by flow cytometry (Figure 5B) showed that starting at the 40 min time point and continuing through the 2 h time point, the signal generated with the phosphoro-dithioate and –trithioate nucleophile probes was 1.8 to 2.1-fold greater (respectively) than the standard phosphoromonothioate nucleophile probe. Thus, both the rate of signal generation and the signal-to-background ratio was increased for the PS2 and PS3 probes.

Figure 5.

Cellular experiments showing enhanced reactivity of PS2 and PS3 nucleophiles (with PS1 for comparison) in detection of 16S ribosomal RNA in intact Escherichia coli. Nucleophilic probes (1 μM), helper DNAs (3 μM), and 5′-dabsyl-quenched electrophile probes (200 nM) were mixed with cells in a solution containing 20 mM Tris (pH 9.0) with 1.0 M NaCl and 0.05% SDS, and then bacteria were imaged by epifluorescence microscope or evaluated by flow cytometry without any washing or separation steps. A. Epifluorescence microscope images of cells after one hour, showing qualitatively brighter signals with the PS2 and PS3 nucleophiles. B. Quantitative comparison of signals by flow cytometry as a function of incubation time in live E. coli. Previous controls with mismatched probes have shown that the reaction at this site is dependent on the target sequence.33

Discussion

Our goal in this study was to develop DNA nucleophiles with increased reactivity, and to investigate whether this greater reactivity would improve cellular detection of RNAs by templated autoligations. Our results show that phosphorodithioate and phosphorotrithioate groups do, in fact, have enhanced nucleophilicity in DNA- and RNA-templated reactions. This increased reactivity in DNA probes leads to faster generation of signal and elevated signal-to-background ratios over previous phosphoromonothioate nucleophilic probes. Our data in solution show rates that are increased by a factor of two for PS2 nucleophilic probes and a factor of three for PS3 probes. This higher nucleophilicity may be due to a combination of increased polarizability, increased numbers of nucleophilic atoms, and/or higher basicity relative to PS1 nucleophiles. In addition to these effects of nucleophilicity, previous experiments with phosphoromonothioate probes of varied length and different temperatures have shown that reaction rates depend also on the ability of probes to fully bind the target, which in turn depends on probe length and temperature.21,33 In the present experiments we kept these latter factors constant.

The PS2 and PS3 probes were prepared in good yields and without any requirement for DNA modification after release from the solid support. Our scheme requires one more step than conventional phosphoromonothioate synthesis, which is routinely performed with commercial reagents and with fully automated cycles. One additional requirement for the PS2 and PS3 syntheses, however, is prior preparation of the diisopropylaminodithiaphospholane reagent 2, and of 3-mercaptopropionitrile in the PS3 case. These are readily prepared on relatively large scales using published methods45, 46 and can be stored for well over a year without degradation.

One unknown issue prior to this work was the aqueous stability of these sulfurized probes. Our data with terminally-substituted groups show that both PS2 and PS3 groups conjugated to DNA are stable at slightly basic pH (pH=9), and can be stored for months under those conditions. At pH 7, 3′-terminal phosphorodithioate is still relatively stable, remaining 90% intact after several days at ambient temperature. The phosphorotrithioate group, on the other hand, is less stable at pH 7, being 50% degraded in 13–14 h. However, this nucleophile still remains 90% intact after 2 h, long enough to yield useful signals in DNA or RNA detection at neutral pH. Not surprisingly, both PS2 and PS3 groups are more rapidly degraded at pH 5, suggesting that protonation at sulfur increases the rate of hydrolysis. The increased rate of PS3 degradation would be consistent with greater basicity of this anion over the PS2 group.

When tested in intact E. coli cells, the PS2 and PS3 nucleophilic probes were found to yield signals approximately twice as rapidly as the earlier PS1 probes. Interestingly, both the PS2 and PS3 probes reacted at similar rates, despite their differences in solution. This suggests that the less stable PS3 probes offer no strong advantage over the PS2 probes in cellular applications, at least in bacteria. This could be due to partial degradation of the PS3 probes after preparation or in the intra- or intercellular medium during the 2-hour course of the experiment, or to some other nonspecific interaction of phosphorotrithioate groups in cells. Overall, both the PS2 and PS3 modifications allowed for signal-to-background ratios of 8–9 with this ribosomal target at two hours, double that of the previous PS1 probes.33 We hypothesize that the intracellular background signal (which appears even in the absence of nucleophilic probe) arises chiefly from hydrolysis or other nucleophilic reaction that displaces the “dabsylate” leaving group on the electrophilic probe. Increased nucleophilicity would therefore increase specific signal over this background, consistent with what was observed. The data suggest that in the future, PS2 and PS3 probes may allow for detection of bacterial or human cellular RNAs even when they exist in smaller copy number than was previously possible.47–50

Experimental Section

General Procedures

All mass spectra samples were analyzed on a ThermoFinnigan quadrupole ion trap LC-MS using positive and negative electrospray ionization. NMR studies were carried out using a Varian Mercury 400 or Inova 500 NMR spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane (1H) or 70% phosphoric acid (31P). All reagents were purchased from commercial sources, except where specified, and used without further purification.

2-Chloro-1,3,2-dithiaphospholane (1).45,51

To a solution of PCl3 (0.25 mol, 22.3 mL) and triethylamine (0.63 mol, 87.0 mL) in 2L diethyl ether at room temperature, a solution of 1,2-ethanedithiol (0.25 mol, 22.1 mL) in 1.0 L of ether was added over a period of 2 h via cannula. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight, filtered, and solvents were removed under reduced pressure. The product was distilled at 15 mm Hg (bp=112–116°C), yielding 18.1 g (45.6%) of pure 2-chloro-1,3,2-dithiaphospholane as a colorless liquid. 1H NMR (CDCl3): 3.54–3.62 (m, 2H), 3.68–3.76 (m, 2H). 31P NMR (CDCl3): 169.0.

2-(N,N-diisopropylamino)-1,3,2-dithiaphospholane (2).45

A solution of dry N,N-diisopropylamine (84.2 mmol, 8.53 g) in 15 mL benzene was added over a five minute period to a solution of 2-chloro-1,3,2-dithiaphospholane (42.1 mmol, 6.68 g) in 50 mL benzene. After 3h, the reaction mixture was filtered and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. Distillation at 40 mm Hg yielded 7.7 g 2-(N,N-diisopropylamino)-1,3,2-dithiaphospholane (bp=140–141°C) as a colorless liquid (81.9% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): 1.14–1.18 (d, 12H), 3.06–3.15 (d of sept, 2H), 3.42–3.55 (m, 4H). 31P (CDCl3): 95.6.

5′-O-acetylthymidine.52

Acetic anhydride (24.0 mmol, 2.27 mL) in 20 mL dry pyridine was added over a five minute period to a solution of thymidine (20 mmol, 4.84 g) in 120 mL pyridine at −40°C. The reaction mixture was allowed to slowly warm to room temperature and was then maintained at that temperature for a further seven hours. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the products were purified by silica column chromatography (0–70% acetone in CH2Cl2). 1.57 g pure 5′-O-acetylthymidine was isolated in 28% yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): 1.88–1.90 (d, 3H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.19–2.32 (m, 2H), 3.28–3.32 (m, 1H), 4.03–4.08 (d of t, 1H), 4.22–4.35 (m, 2H), 4.32–4.38 (m, 1H), 6.22–6.30 (t, 1H), 7.50 (s, 1H).

5′-O-acetyl-3′-O-(2-thio-1,3,2-dithiaphospholane)-thymidine (3).45

To a solution of 5′-O-acetyl-thymidine (2.77 mmol, 0.786 g) in 50 mL CH2Cl2 at room temperature was added elemental sulfur (42.1 mmol, 1.38 g), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (2.77 mmol, 0.48 mL), and a solution of 2-chloro-1,3,2-dithiaphospholane (2.77 mmol, 0.438 g) in 10 mL CH2Cl2. After 48 hours, the reaction mixture was filtered over a bed of Celite and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The resulting oil was purified over NEt3-washed silica gel, using a gradient of 0–60% ethyl acetate in CH2Cl2. 5′-O-acetyl-3′-O-(2-thio-1,3,2-dithiaphospholane)-thymidine was obtained in 46% yield (1.27 mmol, 0.548 g). 1H NMR (CDCl3): 1.94 (d, 3H), 2.14 (s, 3H), 2.20–2.26 (m, 1H), 2.60–2.66 (m, 1H), 3.65–3.76 (m, 4H), 4.34–4.38 (m, 2H), 4.42–4.46 (m, 1H), 5.24–5.30 (m, 1H), 6.32–6.36 (d of d, 1H), 7.22–7.24 (d, 1H), 8.68 (s, 1H). 31P NMR (CDCl3): 124.2.

3-Mercaptopropionitrile.46

To a solution of 100 g (1.35 mol) sodium hydrogen sulfide monohydrate in 400 mL degassed water, neat acrylonitrile (53.1 g, 1.00 mol) was added. The reaction mixture was heated to 50°C for 30 minutes, allowed to cool, and then concentrated HCl was added until the pH dropped to ~8 (about 50 mL). The solution was extracted with five 100 mL volumes of CH2Cl2, the organic portions were pooled, and solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Distillation of the remaining oil provided 69.9 g 3-mercaptopropionitrile as a colorless liquid (87°C at 15 mm Hg; reported 70°C/12mm Hg) in 80.3% yield. The product was stored at −80 °C. [Note: samples of 3-mercaptopropionitrile stored at room temperature degraded within one week despite efforts to exclude O2. Samples stored at −80°C have shown no decomposition after 1.5 years.] 1H NMR (CDCl3): 1.76–1.80 (t, 1H), 2.73–2.77 (d of t, 2H), 2.65–2.68 (t, 2H).

3′-O-phosphorodithiothymidine

To a solution of 50 μmol 3 and 250 μmol 3-hydroxypropionitrile in 200 μl CH3CN, 60 μmol DBU was added. After five minutes, 1.0 mL 28% aqueous NH4OH and 5–10 mg dithiothreitol were added and the reaction mixture was incubated at 45°C for three hours. Approximately 5 mg Tris base was then added and solvents were removed under reduced pressure. The resulting 3′-O-phosphorodithiothymidine was then dissolved in 20 mM pH 9.0 Tris buffer and stored at −80°C until purified. The yield was approx. 70% as measured by integration of HPLC peaks. MS: m/z calculated: 354.01. m/z found: 377.0 (M+Na).

3′-O-phosphorotrithiothymidine

3′-O-phosphorotrithiothymidine was prepared in a procedure similar to that used for the synthesis of 3′-O-phosphorodithiothymidine, except 3-mercaptopropionitrile was used instead of 3′-hydroxypropionitrile. The yield was ca. 70%, as measured by integration of HPLC peaks. MS: m/z calculated: 370.01. m/z found: 368.8 (M-H).

Oligodeoxynucleotide synthesis

All oligonucleotides were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems 394 synthesizer. Unmodified oligonucleotides and PS1-bearing oligonucleotides were synthesized from 3′-phosphoramidites using standard phosphoramidite chemistry and 3H-1,2-benzodithiole-3-one-1,1-dioxide as sulfurizing reagent.

Synthesis of 3′-terminal phosphorodithioate and phosphorotrithioate oligonucleotides

PS2 and PS3 modified oligonucleotides were prepared using commercially available 5′-phosphoramidites. Following PS2 and PS3 oligonucleotide synthesis, an 18-minute synthesis cycle was run to add the dithiaphospholane to the 3′-end (see Supporting Information for cycle details). This cycle contained two two-minute coupling steps with 100 mM 2-(N,N-diisopropylamino)-1,3,2-dithiaphospholane (2) followed by two three-minute sulfurization steps using 1.5 M elemental sulfur in 1:1 CS2/pyridine. Deprotection and cleavage from the solid support was effected using a two-step procedure. First, the CPG resin was incubated with a 0.5 M solution of HX(CH2)2CN and 1.5 M DBU in CH3CN at room temperature (X = O for PS2, X = S for PS3). After five minutes, the resin was rinsed four times with 1 mL CH3CN. 1.0 mL 28% aqueous NH4OH containing about 5 mg DTT was added and the resin was incubated at 45°C for three hours. The solution was then removed from the CPG resin, approx. 5 mg Tris base was added, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure.

HPLC purification of phosphorothioated and dabsylated oligonucleotides

Oligodeoxynucleotides bearing phosphorothioates were purified by anion exchange chromatography on an Alltech Prosphere P-WAX-NP column using a linear gradient of 0–200 mM NaCl in 20 mM Tris (pH 9.0) over 20 minutes. 3′-Phosphorothioated thymidines for stability studies were purified using a gradient of 0.05–1.0 M NaCl in 20 mM Tris (pH 9.0) over ten minutes. Oligonucleotides were stored in the eluate at −80°C until used in ligation studies. Dabsylated electrophiles were prepared as described27 and purified on an Alltech Econosil C18 column using a gradient of 5–50% acetonitrile in pH 7.0 50mM TEAA buffer over 40 min.

Stability studies

All samples used in stability studies were stored in pH 9.0 20 mM Tris at −80 °C until the start of each reaction. pH 5.0 and 7.0 stability studies were initiated at Time=0 by addition of the dT-PSx sample to pH-adjusted incubation buffers. Aliquots removed at early timepoints (<10min) were added to a pH 9.0 buffer before HPLC analysis to prevent further decomposition; later timepoints were injected directly onto the HPLC. Samples were analyzed on a Waters X-terra MS C18 column using a 0–14% gradient of methanol in 0.1 M TEAA (pH 9.0) over 12 min.

In vitro autoligation reactions

Autoligations were carried out using phosphorothioated heptamers of sequence 5′-dCTAGCGT-PSx-3′ and a 5′-dabsylated 13mer of sequence 5′-dab-dTGT*GAACTGTTCA-3′ (T*= 5-[N-(fluoresceinyl aminohexyl)-3-acrylimido]-2′-deoxyuridine) in the presence of a complementary 28mer (5′-dACCTGAACAGTTCACAACGCTAGCCATC-3′. Ligations were performed in 10mM Tris borate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 1.0 μM DTT. Reaction mixtures contained 100 nM each of dabsyl probe and template and 200 nM phosphorothioate probe. Reactions were initiated by addition of the dabsylated probe to a 700 μl cuvette containing the other reaction components. Fluorescence emission at 518 nm was monitored on a SPEX Fluorolog 3 spectrofluorometer using an excitation wavelength of 494 nm. Temperature was maintained at 22°C for all reactions.

Bacterial RNA detection experiments

All materials and reagents were sterilized by autoclaving at 120 °C for 20 min. E. coli K12 (ATCC 10798) were grown to mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.4–0.6) in LB Media (DIFCO) at 37 °C with rapid shaking. Aliquots of media (1 mL) were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 10,000 rpm, supernatant was removed, and the pellets were washed with 0.5 mL of PBS buffer (pH 7.2). The pellets were then resuspended in hybridization buffer (20 mM Tris pH 9.0 with 1.0 M NaCl and 0.05% SDS).

Aliquots of bacteria suspended in hybridization buffer (100 μL) were treated with dabsyl probe (200 nM), nucleophile probe (phosphoro-thioate, -dithioate, or –trithioate) probe (1 μM), and helper probes (3 μM each). The reactions were incubated in the dark at 37 °C, and then monitored by microscopy or flow cytometry without any washing steps. Probes were targeted to 16S rRNA sequences as follows: dabsyl, 5′-LAGT(f)CGACA-3′ (L = dabsyl butyl linker, T(f) = fluorescein dT); nucleophile, 5′-AGGGCACAACCTCCA-PSx-3′; helpers, 5′-ACTCCGGAAGCCACGCCT-3′ and 5′-TCGTTTACGGCGTGGACT-3′.

Fluorescence images were obtained with an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse E800 equipped with 100× objective Pan Fluor apo) with a super high-pressure mercury lamp (Nikon model HB-10103AF), excitation 460–500 nm, using a SPOT RT digital camera and SPOT Advanced imaging software. Typical digital camera settings were as follows: exposure time green 3 seconds, no binning, gain = 2. Flow cytometry data were collected on a FACScan instrument (Becton Dickinson) using an argon laser (ex = 488 nm). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software version 4.6.1 (Tree Star, Inc.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (GM068122), and by the U.S. Army Research Office. A.P.S. acknowledges a Lieberman Graduate Fellowship. We thank Dr. Petra Rzepecki for assistance and advice.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Weimann BJ, Lohrmann R, Orgel LE, Schneider-Bernloehr H, Sulston JE. Science. 1968;161:387. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3839.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Von Kiedrowski G. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1986;25:932–935. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orgel LE. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:99–123. doi: 10.1080/10409230490460765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolinnaya NG, Sokolova NI, Gryaznova OI, Shabarova ZA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:3721–3738. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.9.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sokolova NI, Ashirbekova DT, Dolinnaya NG, Shabarova ZA. FEBS Lett. 1988;232:153–155. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80406-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gryaznov SM, Letsinger RL. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:3808–3809. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao S, Liu F, Rosen A, Hainfeld JF, Seeman NC, Musier-Forsyth KM, Kiehl RA. J Nanoparticle Research. 2002;4:313–317. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshina-Ishii C, Miller GP, Kraft ML, Kool ET, Boxer SG. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1356–1357. doi: 10.1021/ja043299k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gartner ZJ, Liu DR. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6961–6963. doi: 10.1021/ja015873n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gartner ZJ, Kanan MW, Liu DR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:1796–1800. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1796::aid-anie1796>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gartner ZJ, Tse BN, Grubina R, Doyon JB, Snyder TM, Liu DR. Science. 2004;305:1601–1605. doi: 10.1126/science.1102629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanan MW, Rozenman MM, Sakurai K, Snyder TM, Liu DR. Nature. 2004;431:545–549. doi: 10.1038/nature02920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rozenman MM, Liu DR. Chem Bio Chem. 2006;7:253–256. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gryaznov SM, Schultz R, Chaturvedi SK, Letsinger RL. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2366–2369. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.12.2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrlein MK, Letsinger RL. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5076–5078. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.23.5076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Y, Kool ET. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:875–881. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.3.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Y, Karalkar NB, Kool ET. Nature Biotech. 2001;19:148–152. doi: 10.1038/84414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sando S, Kool ET. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2096–2097. doi: 10.1021/ja017328s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Y, Kool ET. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:5595. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)01266-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sando S, Abe H, Kool ET. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1081–1087. doi: 10.1021/ja038665z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abe H, Kool ET. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13980–13986. doi: 10.1021/ja046791c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mattes A, Seitz O. Chem Commun. 2001:2050–2051. doi: 10.1039/b106109g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ficht S, Mattes A, Seitz O. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9970–9981. doi: 10.1021/ja048845o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ficht S, Dose C, Seitz O. Chembiochem. 2005;6:2098–2103. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dose C, Ficht S, Seitz O. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:5369–5373. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma Z, Taylor JS. Bioconj Chem. 2003;14:679–683. doi: 10.1021/bc034013o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai J, Li X, Yue X, Taylor JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16324–16325. doi: 10.1021/ja0452626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain SS, Anet FA, Stahle CJ, Hud NV. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:2004–2008. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogino M, Yoshimura Y, Nakazawa A, Saito I, Fujimoto K. Org Lett. 2005;7:2853–2856. doi: 10.1021/ol050709g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrlein MK, Nelson JS, Letsinger RL. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:10151–10152. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Y, Kool ET. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9040–9041. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sando S, Kool ET. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9686–9687. doi: 10.1021/ja026649g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverman AP, Kool ET. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4978–4986. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iyer RP, Egan W, Regan JB, Beaucage SL. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:1253–1254. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein CA, Subasinghe C, Shinozuka K, Cohen JS. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:3209–3221. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.8.3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marshall WS, Caruthers MH. Science. 1993;259:1564–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.7681216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghosh MK, Ghosh K, Dahl O, Cohen JS. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5761–5766. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.24.5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cummins L, Graff D, Beaton G, Marshall WS, Caruthers MH. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8734–8741. doi: 10.1021/bi960318x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okruszek A, Sierzchala A, Sochacki M, Stec WJ. Tetrahedron Let. 1992;33:7585–7588. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okruszek A, Sierzchala A, Fearon KL, Stec WJ. J Org Chem. 1995;60:6998–7005. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okruszek A, Olesiak M, Krajewska D, Stec WJ. J Org Chem. 1997;62:2269–2272. doi: 10.1021/jo961801g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okruszek A, Guga P, Stec WJ. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1987:594–595. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seeberger PH, Yau E, Caruthers MH. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:1472–1478. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fuchs BM, Glockner FO, Wulf J, Amann R. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3603–3607. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.8.3603-3607.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okruszek A, Olesiak M. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3850–3854. doi: 10.1021/jm00048a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tomioka, T. U.S. Patent 5,256,818, 1993.

- 47.Silverman AP, Kool ET. Trends Biotech. 2005;23:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abe H, Kool ET. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:263–268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509938103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santangelo PJ, Nix B, Tsourkas A, Bao G. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tyagi S, Alsmadi O. Biophys J. 2004;87:4153–4162. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.045153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peake SC, Fild M, Schmutzler R, Harris RK, Nichols JM, Rees RG. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1972;2:380–385. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koole LH, Van Genderen MHP, Buck HM. J Org Chem. 1988;53:5266–5272. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.