Abstract

A detailed investigation of the binding of secretory component to immunoglobulin A (IgA) in human secretory IgA2 (S-IgA2) was made possible by the development of a new method of purifying S-IgA1, S-IgA2 and free secretory component from human colostrum using thiophilic gel chromatography and chromatography on Jacalin-agarose. Sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of unreduced pure S-IgA2 revealed that, unlike in S-IgA1, a significant proportion of the secretory component was bound non-covalently in S-IgA2. When S-IgA1 was incubated with a protease purified from Proteus mirabilis the secretory component, but not the α-chain, was cleaved. This is in contrast to serum IgA1, in which the α-chain was cleaved under the same conditions – direct evidence that secretory component does protect the α-chain from proteolytic cleavage in S-IgA. Comparisons between the products of cleavage with P. mirabilis protease of free secretory component and bound secretory component in S-IgA1 and S-IgA2 also indicated that, contrary to the general assumption, the binding of secretory component to IgA is different in S-IgA2 from that in S-IgA1.

Keywords: human colostrum, IgA, mucosal immunity, protease, secretory component

Introduction

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) is the main antibody class at mucosal surfaces and the second most prevalent antibody class in human serum. There are two subclasses: IgA1 and IgA2. The latter exists in two well-defined allotypic forms, IgA2m(1) and IgA2m(2) with a third form IgA2(n) defined by molecular biology but yet to be characterized in genetic studies.1 IgA1 is only found in humans and higher apes. In most other species the IgA is more similar to IgA2. IgA1 is uniquely sensitive to specific IgA1 proteases secreted by a number of important human pathogens. These enzymes do not cleave IgA2. IgA1 and IgA2 are found in different proportions and in different structural forms in a variety of biological fluids of the body.2 For example, the IgA in serum is synthesized mainly in the bone marrow and is predominantly a monomer of IgA1. In contrast, secretory IgA (S-IgA), the form of IgA synthesized at mucosal surfaces to protect them from microbial attack, is dimeric or polymeric IgA, linked by a joining (J) chain and complexed with the heavily glycosylated protein – secretory component (SC). In secretions such as colostrum, which is the richest source of secretory IgA, the concentration of S-IgA1 and S-IgA2 is similar. Clearly, S-IgA and serum IgA are structurally very different.

SC is the extracellular proteolyic cleavage product of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) that mediates the transport of polymeric IgA (pIgA) across the epithelial barrier.3 When the pIgR transporting pIgA reaches the apical plasma membrane of the mucosal epithelial cell there is extracellular proteolytic cleavage, which releases the extracellular portion of pIgR bearing pIgA. This is S-IgA. In the absence of bound pIgA, the pIgR itself is cleaved and the released component is called free secretory component (FSC). SC is thought to give stability to the structure of S-IgA and to increase its resistance to proteolytic degradation.2

In human S-IgA1, the SC is covalently bound to IgA1 through the interaction of Cys467 in domain 5 of SC with Cys311 of the CH2 of the α1-chain,4 the disulphide bonding occurring late in the transcytotic pathway.5 Most immunologists have assumed that the binding of SC in human S-IgA2 is similar but this has not been proven because of the difficulty in purifying a sufficient quantity of S-IgA2 in a natural or recombinant form for the investigation to be made. Recent studies have shown that serum IgA2 differs structurally from serum IgA1.6

We have previously reported the ability of an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-sensitive metalloprotease from Proteus mirabilis to cleave the SC of S-IgA1.7Proteus mirabilis is a common cause of urinary tract infection, particularly in young boys and elderly women.8,9 Most strains of P. mirabilis of diverse types produce this protease, which cleaves in addition to SC, the heavy chain of IgA1, IgA2 and IgG.10,11 Since the protection conferred by S-IgA on mucous membranes depends upon its structural integrity, any significant degradation of one or more components of the molecule is likely to influence its function.

The aims of this study were to devise ways to isolate S-IgA2 in sufficient quantity and purity to permit its characterization and to investigate the cleavage by P. mirabilis protease of the SC of pure S-IgA1, S-IgA2 and the FSC, to understand the mode of association between IgA subclasses and SC. These studies will enhance our understanding of the structural organization and functional activity of S-IgA subclasses.

Materials and methods

Colostrum collection and preparation

Samples of human colostrum, in which the S-IgA component is composed of approximately equal proportions of S-IgA1 and S-IgA2, were collected within the first 48 hr postpartum by the method of Jackson et al.12 except that before collection, the nipples were cleansed and swabbed with warm sterile water instead of alcohol, which tends to dry and crack nipples and cause bleeding. Mothers with mastitis or cracks around the nipples were excluded as donors to avoid any contamination of colostral S-IgA with serum IgA from the blood. All colostrum samples were frozen at − 20°. All colostrum samples were obtained with informed consent. The study was validated by the local ethics committee.

Purification of S-IgA1, S-IgA2 and FSC

Preparation of thiophilic resin

Thiophilic resin was prepared by the method of Scoble and Scopes13 using 100 μl divinylsulphone/g wet Sepharose and a reaction time of 8 hr. The resin had a much higher immunoglobulin-binding capacity (28 mg/ml) than that used by others for the purification of IgG13,14 and that available commercially.

Purification scheme

Twenty millilitres of frozen colostrum were thawed at 37° and mixed with 10 ml of isotonic saline (0·9% NaCl). The diluted colostrum was separated by centrifugation at 100 000 g for 1 hr at 4° into an upper fatty layer, a middle aqueous layer containing the immunoglobulins and the cell pellet. The middle layer was retrieved, supplemented with sodium sulphate to a final concentration of 0·5 m and loaded onto a column (50 × 1·0 cm) of thiophilic resin equilibrated in 0·5 m sodium sulphate, 50 mm sodium phosphate, 0·1% sodium azide buffer, pH 8. The column was washed with the buffer until the absorbance at 280 nm of the effluent reached baseline. The bound immunoglobulins were then eluted from the column with 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer pH 8 containing 0·1% sodium azide. The collected fractions were analysed by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), immunoblotting, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and single radial immunodiffusion. Those fractions shown to contain S-IgA were pooled, dialysed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS pH 7·2) and loaded onto a column containing 35 ml Jacalin-agarose (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK). Once the non-binding proteins (which included S-IgA2, S-IgM and FSC) had been washed from the column with PBS and saved, the S-IgA1 was eluted from the column with PBS pH 7·2 buffer containing 0·8 m d-galactose. Analysis of the fractions and washings confirmed that all the S-IgA1 had bound to the Jacalin-agarose and been eluted later with galactose. Subsequent S-300 gel filtration of the isolated S-IgA1 readily separated the dimeric form of S-IgA1 from higher polymeric forms.

The saved Jacalin-agarose column run-through was concentrated and subjected to gel filtration on an S-300 column. This resolved the protein mixture into three peaks. Subsequent analysis of these showed them to represent S-IgM and polymeric S-IgA2, dimeric S-IgA2 and FSC, respectively. The fractions containing FSC from both S-300 gel filtration and the Jacalin-agarose column run-through were pooled, concentrated and purified by affinity chromatography on a column of pIgA1–Sepharose because of the known high affinity of FSC for pIgA. Serum pIgA1 at 5 mg/ml in coupling buffer was linked to Sepharose according to the manufacturer's protocol (GE Healthcare, Bucks, Chalfont St. Giles, UK). After thorough washing and equilibration of the column in PBS, the column was eluted with 0·5 m acetic acid pH 3 and the collected fractions were immediately neutralized with Tris buffer. The eluted fractions and run-through were analysed by SDS–PAGE, Western blotting and gel filtration fast-protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) and those containing pure FSC were saved.

Proteus mirabilis protease preparation

Proteus mirabilis strain 64676 was cultured in 1 litre nutrient broth at 37° for 48 hr. The protease was purified from the filtrate (0·45-μm and 0·22-μm pore filters) of the centrifuged culture supernatant fluid by affinity chromatography on a column (25 × 5 cm) of Phenyl–Sepharose (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 50 mm Tris–HCl pH 8·0 followed by anion exchange chromatography on an FPLC Mono Q column (GE Healthcare) as described previously.15 The purity and activity of the purified proteinase were confirmed by SDS–PAGE and SDS–gelatin–PAGE as described previously.15

Protein digestion with P. mirabilis protease

The same concentration of each form of SC-containing molecule (FSC, S-IgA1 and S-IgA2) was incubated with a standard amount of P. mirabilis protease at 37° for 24, 48 or 72 hr. The products of the digestion were subsequently analysed by SDS–PAGE, immunoblotting and gold staining.

SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting

SDS–PAGE was performed after the method of Laemmli16 in resolving gels of various acrylamide concentrations (see figure legends for details). The upper tank buffer was 50 mm Tris–HCl containing 0·39% glycine and 0·1% SDS pH 8·9 and the lower tank buffer was 100 mm Tris–HCl buffer pH 8·1 containing 0·1% SDS. Samples were reduced by boiling them for 3 min with an equal volume of disruption buffer (0·1 m Tris–HCl pH 8, 8 m urea, 2% SDS and a trace of bromophenol blue dye) containing 80 mm dithiothreitol and then blocked by the immediate addition of iodoacetamide to 100 mm. Unreduced samples were prepared by adding to them to an equal volume of disruption buffer containing 40 mm iodoacetamide and boiling for 3 min. Samples were electrophoresed at 30 mA/gel in the cold until the dye front reached the bottom of the gel. The gels were either stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250 (GE Healthcare) or the separated proteins in them were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by electrophoresis in aqueous 25 mm Tris–HCl, 190 mm glycine containing 10% methanol at 4° for 16 hr at 10 V. The membranes were then stained with 0·2% Ponceau S dye (Sigma, Poole, UK) in 3% trichloroacetic acid and the positions of reference proteins were marked. The identity of all of the stained bands visible in gels was determined and subsequently confirmed by immunoblotting with one or more of the relevant antibodies.

For immunoblotting, the membranes were blocked by agitation for 2 hr in PBS containing 5% dried milk powder, and then agitated for 2 hr in 5% dried milk powder in PBS containing a 1 : 500 dilution of either alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human α- or κ- and λ-chains (Sigma) or mouse anti-IgA1 and anti-IgA2 specific antibodies (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham AL). SC was detected using rabbit anti-human SC (Dako UK, Ely, UK). In this case, after extensive washing in PBS, the membranes were agitated for 2 hr in PBS containing 5% dried milk powder and a 1 : 500 dilution of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (whole molecule) (Sigma). After further extensive washing in PBS, the membranes were developed in buffer (100 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 100 mm Tris–HCl pH 9·5) containing 0·33 mg/ml nitroblue tetrazolium and 0·17 mg/ml bromochloroindolyl phosphate.

FPLC gel filtration

Two hundred microlitres of FSC eluted from pIgA1-Sepharose and the column run-through was run under native conditions on a Superdex 200 (HR 30/10) gel filtration column using an FPLC-AKTA chromatography system (GE Healthcare). Fractions (250 μl) were collected and analysed by Western blotting and probed with an anti-SC antibody.

Results

Isolation of secretory immunoglobulins using thiophilic chromatography

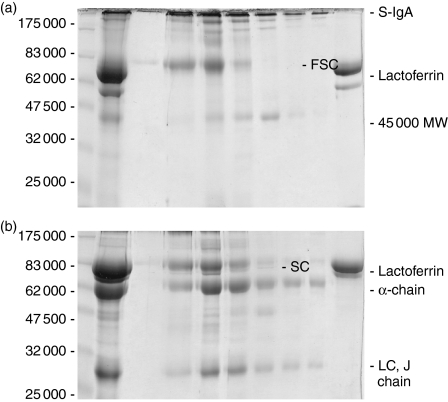

The usefulness of the thiophilic resin for the purification of secretory immunoglobulins from human colostrum is apparent from the results shown in (Fig. 1). All secretory immunoglobulins and FSC bound to the resin and no S-IgA or S-IgM was detected in the run-through. Furthermore, all the lactoferrin, which migrates in SDS–PAGE gels slightly faster than SC (Fig. 1a,b), and which was difficult to remove in previous purification schemes, was separated completely from IgA and the SC. All of the lactoferrin appeared in the run-through from the thiophilic resin. Analysis of the eluted fractions on reduced gels showed the presence of predominantly the component polypeptides of S-IgA, that is SC, α-chain, light chain and J-chain, demonstrating the isolation of highly pure S-IgA with only minor contaminants after one single chromatography step on the thiophilic resin (Fig. 1b). Although earlier work in our laboratory had suggested that FSC did not bind to commercial (Perbio, Cramlington, UK) thiophilic resin (unpublished observations), using the more heavily derivatised thiophilic resin, a band of 80 000 molecular weight (MW) was observed on gels run under non-reducing conditions when the fractions eluted from the modified thiophilic resin were analysed by SDS–PAGE (Fig. 1a). This was subsequently shown to be FSC. Moreover, in the same figure, a band with apparent mass of approximately 45 000 was observed. This band, which disappeared on reduction, was subsequently shown to contain dimer of the light chains of S-IgA2 (see Fig. 3). At the top of the gel a number of bands reactive with anti-IgA-Fc antisera were observed (not shown). These were the tight bands at the very top of the gel shown and two just entering the 10% gel. The fractions eluted from the thiophilic resin were pooled and applied to Jacalin-agarose.

Figure 1.

Coomassie-Blue-stained 10% SDS–PAGE of clarified human colostrum and fractions from chromatography of colostrum on thiophilic resin Gels were run under (a) non-reducing conditions or (b) reducing conditions. Lane 1, protein markers; lane 2 clarified colostrum starting material; lanes 3–9, every second fraction eluted from thiophilic resin; lane 10 column run-through.

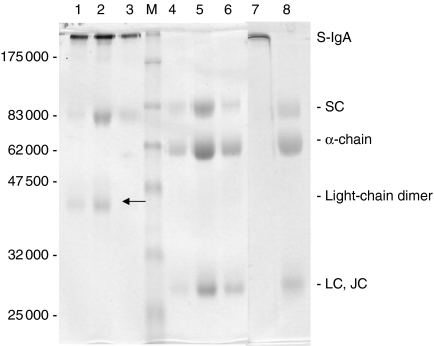

Figure 3.

Western blot (10% SDS–PAGE run under non-reducing conditions) of dimeric S-IgA2 peak fractions from Sephacryl S-300 column probed with rabbit anti-SC antibody (SC), goat anti-human-light chains (λ and κ) antibody (LC) or 5% SDS–PAGE blotted with monoclonal anti-α2 (α2) Protein markers are shown in lane 1.

Separation of S-IgA1 using Jacalin-agarose chromatography

When the eluted fractions from the thiophilic resin were pooled and applied to a column of Jacalin-agarose, analysis of the fractions from this column demonstrated the presence of S-IgA in both the run-through and in the fractions eluted with galactose. Immunoblotting under non-reducing conditions showed that the presence the S-IgA1 occurred in at least two forms in the bound fractions. These corresponded to different polymeric forms of S-IgA1 because their analysis by SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions revealed the presence, confirmed by immunoblotting, of only SC, α1-chain and light chain running with J-chain. The S-IgA in the run-through of the Jacalin-agarose column, which also ran as two bands on gels, was confirmed by immunoblotting to be S-IgA2 devoid of any S-IgA1. The S-IgA2 included material which ran slightly faster than S-IgA1 on 5% gels, although on 10% gels the differences were not obvious.

The Jacalin-agarose purification stage had therefore fulfilled an important role in separating S-IgA2 from S-IgA1 and enabling S-IgA1 to be purified to homogeneity (with respect to composition but not with respect to polymerization state). Different molecular forms of S-IgA1 were separated by Sephacryl-300 gel filtration and further studies on S-IgA1 were restricted to the dimeric form because this was the most abundant.

S-IgA2 purification and characterization

Gel filtration on Sephacryl S300 of the concentrated material from the run-through of the Jacalin-agarose column revealed three peaks. Analysis of these by SDS–PAGE under non-reducing conditions revealed that the first eluting small peak contained S-IgM and polymeric S-IgA2. The second eluting peak, which was by far the largest, was dimeric S-IgA2, indicating that most of the S-IgA2 was in a dimeric form. The last eluting peak represented mainly FSC, which had also bound to the modified thiophilic resin.

To further confirm the purity and characterize the dimeric S-IgA2 200 μl of this preparation was loaded onto a Superdex 200 gel filtration FPLC under native conditions. The chromatogram showed a single symmetrical peak eluting at a position very similar to that of dimeric S-IgA1 (not shown).

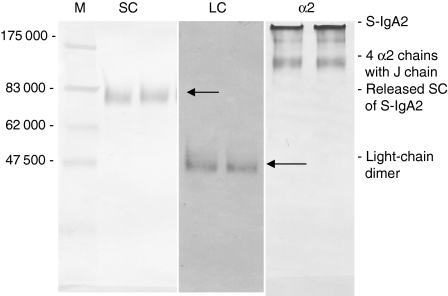

Characterization of SC binding in S-IgA2

The availability of highly purified S-IgA2 permitted investigation of the association of the SC with the rest of the molecule. When concentrated S-IgA2 was subjected to SDS–PAGE under non-reducing conditions, a significant proportion of the SC was found unexpectedly to be released from S-IgA2 (Fig. 2, lane 2). This suggested that in this form of S-IgA2 there is only non-covalent binding between SC and the IgA2 molecule. Moreover, a band of 48 000 MW corresponding to a light-chain dimer was also detected in the same sample. The band tentatively identified as polymeric heavy chain (H4.J), which stains relatively poorly with Coomasssie Brilliant Blue but blots with anti-IgA2 antisera, was also detected. When the S-IgA2 was run under reducing conditions, only the polypeptide chains that make up the S-IgA2 molecule were detected (Fig. 2, lanes 4–6). When pure S-IgA1 samples were run on the same gel under non-reducing conditions, neither free SC nor l-chain dimer were seen to be released from the S-IgA1 (Fig. 2, lane 7). Under reducing conditions S-IgA1 and S-IgA2 were identical, only the polypeptide chains that make up the S-IgA molecule were detected (Fig. 2, lane 8).

Figure 2.

Coomassie-Blue-stained, 10% SDS–PAGE of fractions of purified S-IgA2 (lanes 1–3, 4–6) and S-IgA1 (lanes 7, 8) run under non-reducing (lanes 1–3, 7) or reducing (lanes 4–6, 8) conditions. Lane M, protein markers. The 45 000 MW protein band marked by the arrow (lanes 1, 2) is a light-chain dimer.

When the S-IgA2-containing fractions (peak 2) from the S300 column were analysed by SDS–PAGE under non-reducing conditions and blotted separately with an anti-SC antibody and with monoclonal antibodies specific for each of the light-chain types (κ or λ), the results always supported the earlier findings and confirmed the release of SC (Fig. 3) and heavy- and light-chain dimers (Fig. 3) from S-IgA2 under non-reducing conditions.

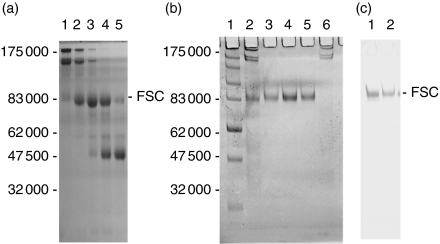

FSC purification

The thiophilic resin bound all of the FSC from clarified colostrum (Fig. 1). FSC (80 000 MW) was readily separated from other secretory immunoglobulins by gel filtration on S-300 of the Jacalin run-through (Fig. 4a). The material from the third peak was pooled and applied to a column of pIgA1-Sepharose. All of the FSC bound to the column and was eluted upon acidification. None of the other proteins from the S300 pool bound to the pIgA column. The purity of the FSC was revealed by SDS–PAGE and Western blotting (Fig. 4b,c).

Figure 4.

(a) Coomassie-Blue-stained 10% SDS–PAGE run under non-reducing conditions of fractions (lanes 1–5) from the third peak eluted from an S300 column loaded with proteins from the Jacalin–agarose column run-through. Lane 3 is the peak fraction. (b,c) FSC fractions from the S300 column pooled and chromatographed on a pIgA1-Sepharose column. Material eluted from pIgA1-Sepharose column is shown stained with Coomassie Blue (b) or after Western blot with rabbit anti-human SC antibody (c). (b) Lane 1 contains molecular weight markers; lane 2, material loaded onto column; lanes 3–5, material eluted from column; lane 6 is column run-through. (c) Lanes 1 and 2 are eluted fractions.

Cleavage of FSC and bound SC of S-IgA1, S-IgA2 by P. mirabilis protease

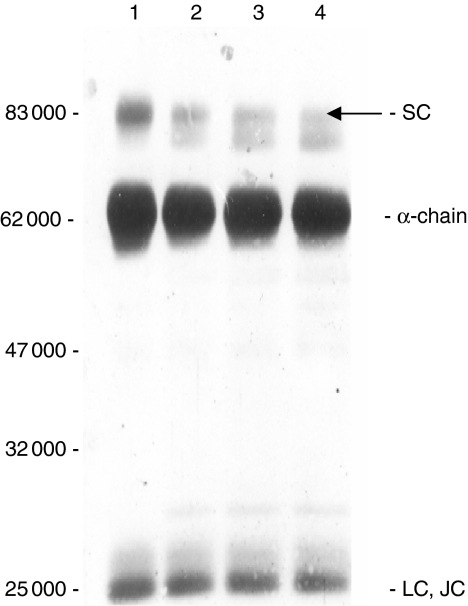

When S-IgA1 was treated with P. mirabilis protease the bound SC was cleaved to give a fragment of about 76 500 MW while the heavy and light chains remained intact (Fig. 5). This was in contrast to serum IgA-treated under the same conditions where, as reported previously, the α-chain was cleaved completely within the same time course under identical conditions.7 We therefore compared the cleavage by P. mirabilis protease of both FSC and SC bound to both IgA isotypes.

Figure 5.

Coomassie-blue-stained 10% SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions of S-IgA1 incubated at 37° with either buffer alone for 40 hr (lane 1) or with P. mirabilis purified protease S-IgA1 for 8 hr (lane 2), 16 hr (lane 3) and 40 hr (lane 4). The 76 500 MW fragment derived from secretory component (SC) is indicated by the arrow.

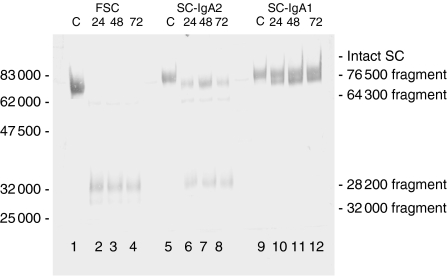

The results showed that the pattern of cleavage of FSC was different from that of bound SC, cleavage of the latter also being different between the two isotypes (Fig. 6). Thus while some of the SC of S-IgA1 was cleaved to yield a fragment of 76 500 MW, some of the SC remained intact despite prolonged incubation with the protease (Fig. 6, lanes 10–12). In contrast, under the same conditions, all of the SC of S-IgA2 was cleaved rapidly and completely into three fragments; 76 500 and 32 000 MW, with a minor component of 64 300 MW. No intact SC remained (Fig. 6, lanes 6–8). On the other hand, and under the same conditions, FSC was cleaved rapidly and completely to give a major fragment of 32 000 MW, together with lesser amounts of fragments of 64 300 and 28 200 MW.

Figure 6.

Western blot of 10% SDS–PAGE run under reducing conditions showing structural features of bound and of untreated (control – C) free secretory component, SC-IgA2 and SC-IgA1 and these after cleavage with P. mirabilis protease at 37° for 24, 48 and 72 hr and probed with rabbit anti-human-SC antibody (detecting antibody is a goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase). Cleavage of FSC and the SC in S-IgA2 was complete within 24 hr but that of the SC in S-IgA1 remained uncleaved after 72 hr.

Because the cleavage products of FSC were completely different from those of the bound SC of S-IgA1, it suggested that the cleavage sites of FSC were masked or buried when it was bound to the IgA1 monomer subunits. However, some of the cleavage products of FSC were the same as those of the bound SC of S-IgA2. These data suggested that all of the SC of S-IgA2 was bound to the rest of the molecule in a different way than it is in S-IgA1 so that the cleavage sites in the SC of S-IgA2 remain fully accessible to the Proteus protease, some of the SC of S-IgA2 is bound non-covalently to the molecule (Figs 2 and 3a).

Discussion

Many of the attempts to characterize S-IgA have been performed on poorly defined mixtures of both isotypes or exclusively with S-IgA1, because of its ease of purification on jacalin. This has resulted in the current, widely accepted model of S-IgA, derived in particular from the detailed characterization of S-IgA1 by Fallgreen-Gebauer et al.4 which showed conclusively that SC was bound covalently to IgA1 to form S-IgA1. In the absence of studies specifically demonstrating the linkage of SC in S-IgA2, it has been assumed that the SC also binds in the same way to the α-chain of S-IgA2. This assumption may be wrong. One of the major problems encountered in the characterization of S-IgA2 has been the difficulty in purifying a sufficient quantity to allow the necessary studies to be made. Attempts to produce large amounts of S-IgA by recombinant technology have also proved difficult.17,18 Because, to our knowledge, no studies have yet investigated the binding of SC to S-IgA2, we chose to investigate this and work with natural forms of human S-IgA from human colostrum because of its high content of similar amounts of both S-IgA1 and S-IgA2.

The previously published scheme19 for the purification of S-IgA2 from colostrum, though successful, is somewhat complicated, laborious and lengthy. Because thiophilic chromatography has been shown to simplify the purification of several different immunoglobulins from various species14,20,21 we sought to devise a simpler and quicker method based on thiophilic chromatography for purifying S-IgA. The development of a modified thiophilic resin together with a rigorous purification procedure permitted colostrum to be separated into large amounts (in approximately equal proportions such as exist in native colostrum) of pure S-IgA1 and pure S-IgA2. The purity being defined by the observation of bands corresponding only to α-chain, light chain and SC in SDS–PAGE run under reducing conditions (Fig. 2, lane 5).

There are very few published studies of the binding of SC to IgA. The results of Crottet and Corthésy,22 in which the sensitivity to the enzymes in mouse intestinal washings of dimeric IgA from a hybridoma was compared to that of dimeric IgA that had been re-associated in vitro with either recombinant SC or human SC from milk should be interpreted with caution because this latter artificial molecule (IgA-associated SC) may be very different regarding the association of different polypeptide chains, binding and conformation from natural in vivo synthesized S-IgA. Furthermore, although the use of the intestinal washings mimics the gut environment, it does not permit a detailed structural analysis of the effects on the re-associated SC-IgA because of the presence of many different proteases.

Our characterization of natural human S-IgA2 revealed several unexpected differences between S-IgA1 and S-IgA2. We have shown that, unlike with S-IgA1, a significant proportion of bound SC was released from S-IgA2 in SDS–PAGE under non-reducing conditions, The current, widely accepted model of S-IgA is derived from many studies including the detailed characterization by Fallgreen-Gebauer et al.,4 which showed that SC bound covalently to IgA1 to form S-IgA1. None of these studies investigated the linkage of SC in S-IgA2.

Our results suggest that this assumption is incorrect. Through the availability of highly purified S-IgA2 we were able to show that, unlike with S-IgA1, bound SC was released from S-IgA2 in SDS–PAGE under non-reducing conditions, suggesting a different structure overall with no interchain disulphide bond (non-covalent bonding) linking SC to IgA2. This important finding was confirmed by SDS–PAGE, immunoblotting and Superdex 200 gel filtration FPLC under native conditions. In the same gels of S-IgA2 under non-reducing conditions, light- and heavy-chain dimers were also detected, indicating that this S-IgA2 is S-IgA2m(1) allotype, which lacks light–heavy interchain disulphide bonds. As with serum IgA2, both types of light chain (κ and λ) were detected as dimer. Figure 3 shows light-chain dimer blotted with a mixture of the two antisera. The same result was observed when the two anti-light chain antisera were used separately.

This demonstration of the non-covalent binding of SC to S-IgA2m(1) is supported by several observations of others. Careful inspection of the figure of an SDS–PAGE unreduced gel of a mixture of S-IgA (S-IgA1 and S-IgA2) in a paper by Lamm and Greenberg23 shows the release of a light-chain dimer (as we have found) and also another faint protein band (not commented on by the authors) of the same mass as the protein we have identified as being released SC. Furthermore, in one of the 13 rabbit IgA isotypes (Cα13), the SC was found to be non-covalently bound in its S-IgA form.24,25 Moreover in human S-IgM, SC is bound non-covalently.26 The non-covalent binding of SC is therefore not unique for the human S-IgA2m(1) allotype. It should be recalled that in vitro we have also shown that SC binds non-covalently to dimeric (serum) IgA1 with sufficient affinity to allow measurement of binding by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and indeed to allow the purification of SC by affinity chromatography. IgA appears to be unique among immunoglobulins in its ability to interact covalently and non-covalently with other proteins.27

The finding that P. mirabilis protease had the ability to cleave SC7 prompted investigations in which the cleavage by the protease of FSC was compared with that of SC in S-IgA1 and in S-IgA2. The results also supported the view that the association between SC and IgA in S-IgA1 is different from that in S-IgA2 and suggested that SC was possibly more exposed on the outside of IgA2 subunit monomers than it was in IgA1. Together these observations suggest that S-IgA2 is structurally less similar to S-IgA1 than previously assumed and that not only does SC stabilize and protect IgA in the harsh environment of mucosae2,28 but that IgA1 also protects SC. We have previously shown11 that the P. mirabilis protease cleaved the α-chains of serum IgA1 and IgA2 at approximately the same rate, with cleavage between the Ch2 and Ch3 domains. Cleavage of the α-chain of secretory IgA1 was much slower and that of sIgA2 was slower still.

Abbreviations

- FPLC

fast-protein liquid chromatography

- FSC

free secretory component

- IgA

immunoglobulin A

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- pIgA

polymeric IgA

- pIgR

polymeric immunoglobulin receptor

- SC

secretory component

- SDS–PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- S-IgA1

secretory IgA1

- S-IgA2

secretory IgA2

- S-IgM

secretory IgM

- SRID

single radial immunodiffusion

References

- 1.Woof JM, Kerr MA, Moro I, Mestecky JR. Mucosal immunoglobulins. In: Mestecky JR, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, Mcghee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. San Diego: Academic Press Inc.; 2005. pp. 153–81. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woof JM, Kerr MA. Function of immunoglobulin A in immunity. J Pathol. 2006;208:270–82. doi: 10.1002/path.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mostov KE. Transepithelial transport of immunoglobulins. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:63–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fallgreen-Gebauer E, Gebauer W, Bastian A, Kratzin HD, Eiffert H, Zimmermann B, Karas M, Hilschmann N. The covalent linkage of secretory component to IgA. Structure of sIgA. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1993;374:1023–8. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1993.374.7-12.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chintalacharuvu KR, Tavill AS, Louis LN, Vaerman JP, Lamm ME, Kaetzel CS. Disulfide bond formation between dimeric immunoglobulin A and the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor during hepatic transcytosis. Hepatology. 1994;19:162–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furtado PB, Whitty P, Robertson A, Eaton JT, Almogren A, Kerr MA, Woof JM, Perkins SJ. Solution structure determination of human IgA2 by X-ray and neutron scattering and analytical ultracentrifugation and constrained modelling: a comparison with human IgA1. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:921–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almogren A, Senior BW, Loomes LM, Kerr MA. Structural and functional consequences of cleavage of human secretory and human serum IgA1 by proteinases from Proteus mirabilis and Neisseria meningitides. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3349–56. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3349-3356.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallett RJ, Pead L, Maskell R. Urinary infection in boys. A three year prospective study. Lancet. 1976;2:1107–10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senior BW. The special affinity of particular types of Proteus mirabilis for the urinary tract. J Med Microbiol. 1979;12:1–8. doi: 10.1099/00222615-12-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senior BW, Albrechtsen M, Kerr MA. Proteus mirabilis strains of diverse type have IgA protease activity. J Med Microbiol. 1987;24:175–80. doi: 10.1099/00222615-24-2-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loomes LM, Senior BW, Kerr MA. A proteolytic enzyme secreted by Proteus mirabilis degrades immunoglobulins of the immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1), IgA2, and IgG isotypes. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1979–85. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1979-1985.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson S, Mestecky J, Moldova Z, Spearman B. Collection and processing of human mucosal secretions. In: Ogra PL, Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, McGhee JR, Bienenstock J, editors. Handbook of Mucosal Immunology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 1567–75. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scoble JA, Scopes RK. Ligand structure of the divinylsulfone-based T-gel. J Chromatogr A. 1997;787:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(97)00691-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porath J, Maisano F, Belew M. Thiophilic adsorption – a new method for protein fractionation. FEBS Lett. 1985;185:306–10. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80928-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loomes LM, Senior BW, Kerr MA. Proteinases of Proteus spp. purification, properties, and detection in urine of infected patients. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2267–73. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2267-2273.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansen FE, Braathen R, Brandtzaeg P. The J chain is essential for polymeric Ig receptor-mediated epithelial transport of IgA. J Immunol. 2001;167:5185–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corthésy B. Recombinant immunoglobulin A. Powerful tools for fundamental and applied research. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20:65–71. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(01)01874-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loomes LM, Stewart WW, Mazengera RL, Senior BW, Kerr MA. Purification and characterization of human immunoglobulin IgA1 and IgA2 isotypes from serum. J Immunol Meth. 1991;141:209–18. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutchens TW, Porath J. Thiophilic adsorption of immunoglobulins – analysis of conditions optimal for selective immobilization and purification. Anal Biochem. 1986;159:217–26. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scoble JA, Scopes RK. Assay for determining the number of reactive groups on gels used in affinity chromatography and its application to the optimisation of the epichlorohydrin and divinylsulfone activation reactions. J Chromatogr A. 1996;752:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crottet P, Corthésy B. Secretory component delays the conversion of secretory IgA into antigen-binding competent F(ab′)2: a possible implication for mucosal defense. J Immunol. 1998;161:5445–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamm ME, Greenberg J. Human secretory component. Comparison of the form occurring in exocrine IgA to the free form. Biochemistry. 1972;11:2744–50. doi: 10.1021/bi00765a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneiderman RD, Hanly WC, Knight KL. Expression of 12 rabbit IgA C alpha genes as chimeric rabbit–mouse IgA antibodies. PNAS. 1989;86:7561–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burnett RC, Hanly WC, Zhai SK, Knight KL. The IgA heavy-chain gene family in rabbit. Cloning and sequence analysis of 13 C alpha genes. EMBO J. 1989;8:4041–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandtzaeg P. Molecular and cellular aspects of the secretory immunoglobulin system. APMIS. 1995;103:1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1995.tb01073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almogren A, Furtado PB, Sun Z, Perkins SJ, Kerr MA. Purification, properties and extended solution structure of the complex formed between human immunoglobulin A1 and human serum albumin by scattering and ultracentrifugation. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:413–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindh E. Increased resistance of immunoglobulin dimers to proteolytic degradation after binding to secretory component. J Immunol. 1975;114:284–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]