Abstract

The ubiquitin–proteasome pathway is the principal system for extralysosomal protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, and is essential for the regulation and maintenance of basic cellular processes, including differentiation, proliferation, cell cycling, gene transcription and apoptosis. The 26S proteasome, a large multicatalytic protease complex, constitutes the system's proteolytic core machinery that exhibits different proteolytic activities residing in defined proteasomal subunits. We have identified proteasome inhibitors – bortezomib, epoxomicin and lactacystin – which selectively inhibit the proteasomal β5 subunit-located chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (DCs). Inhibition of proteasomal chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity in immature and mature DCs impairs the cell-surface expression of CD40, CD86, CD80, human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR, CD206 and CD209, induces apoptosis, and impairs maturation of DCs, as demonstrated by decreased cell-surface expression of CD83 and lack of nuclear translocation of RelA and RelB. Inhibition of chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity abrogates macropinocytosis and receptor-mediated endocytosis of macromolecular antigens in immature DCs, and inhibits the synthesis of interleukin (IL)-12p70 and IL-12p40 in mature DCs. As a functional consequence, DCs fail to stimulate allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and autologous CD4+ T cells sufficiently in response to inhibition of chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity. Thus, proteasomal chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity is required for essential functions of human DCs, and inhibition of proteasomal chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity by selective inhibitors, or by targeting β5 subunit expression, may provide a novel therapeutic strategy for suppression of deregulated and unwanted immune responses.

Keywords: chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity, dendritic cells, immunosuppression, proteasome

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional antigen-presenting cells that arise from CD34+ bone marrow progenitor cells or CD14+ monocytes. DCs migrate as immature precursor cells from the bone marrow into peripheral tissues where they act as sentinels by monitoring the antigenic environment. After capturing foreign or self-antigens in peripheral tissues, DCs undergo a complex maturation process induced by signals generated as a consequence of local inflammation or microbial infection, and display a reduced capacity for antigen uptake and an increased cell-surface expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and costimulatory molecules. When maturation-inducing stimuli are sensed by DCs, they immediately migrate to secondary lymphoid organs where they present processed MHC-bound peptide antigens to T cells, thereby initiating antigen-specific T-cell responses.1 Because DCs are capable of stimulating even immunologically naïve T cells, they play a key role in the initiation and maintenance of primary adaptive immune responses. Dependent on their ontogeny and state of differentiation and maturation, DCs can generate stimulatory, as well as inhibitory, immune responses, thereby playing a dual role in adaptive immunity.2 Thus, DCs have great potential as tools for immunomodulatory trials in cancer, chronic infectious diseases, transplantation and autoimmunity,3–5 and the identification of molecular targets for modulation of DC function is a key subject of current research in basic and applied DC biology.3,6,7

The highly conserved ubiquitin–proteasome pathway is the major system for nuclear and extralysosomal cytosolic protein degradation in eukaryotic cells.8,9 The central proteolytic machinery of this system constitutes the 26S proteasome, a large multicatalytic multisubunit protease complex that degrades and processes essential cell proteins by limited and controlled proteolysis.8,10 By degrading cell proteins essential for regulation of differentiation, proliferation, cell cycling, apoptosis, stress and the inflammatory response, senescence, gene transcription, signal transduction, immune activation and antigen presentation, the 26S proteasome plays a key role in the regulation and maintenance of basic cellular processes.11

The proteolytic activities of the 26S proteasome occur in a barrel-shaped 20S catalytic core complex composed of four axially stacked rings. Each outer ring contains seven different α subunits. The two inner rings are formed by seven β subunits, and only β1, β2 and β5 subunits harbour proteolytic sites formed by N-terminal threonine residues that face the central cavity of the 20S complex.10 Based on their specificity toward oligopeptidyl substrates, β1, β2 and β5 subunits have been defined to possess solely caspase-like, trypsin-like or chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity, respectively.12,13 Various synthetic and biologic inhibitors with different inhibitory profiles towards peptidase activities of β1, β2 and β5 proteolytic subunits have been recently identified and are now available for investigating the biologic function of these subunits in intact cells.14–16 Using a series of such inhibitors, including bortezomib, epoxomicin (EPM) and lactacystin, we show herein that selective inhibition of the β5 subunit-located chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity (CPA) impairs basic functions of human DCs, demonstrating an essential role of proteasomal CPA in DC physiology and immune function.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

Human recombinant (rh) granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), rh interleukin (IL)-4, rh interferon-γ (IFN-γ), rh tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and rh soluble CD40-ligand (sCD40L) were all purchased from AL-Immunotools (Friesoythe, Germany). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli 055:B5 was obtained from Sigma (Heidelberg, Germany).

The fluorogenic proteasome substrates Z-GGL-amc (chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity), Boc-LRR-amc (trypsin-like peptidase activity) and Boc-LLE-amc (caspase-like peptidase activity) were all purchased from Biomol (Hamburg, Germany).

The following monoclonal antibodies were used: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG)1 isotype control (clone MOPC-21), anti-CD40 (5C3) and anti-CD209 (DC-SIGN, DCN46) from BD Pharmingen (Heidelberg, Germany); IgG2b (MCG2b) isotype control, anti-CD11c (BU15), anti-CD14 (M5E2) and anti-human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR (1E5) from AL-ImmunoTools; and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated IgG1 isotype control (MOPC-21), anti-CD11c (B-ly6), anti-CD80 (L307.4), anti-CD83 (HB15e), anti-CD86 (2331) and anti-CD206 (Mannose receptor, 19.2) from BD Pharmingen.

Anti-CD206 (goat polyclonal IgG; C-20), anti-HLA-DR (mouse monoclonal IgG1; Bra22), anti-RelA (p65) (mouse monoclonal IgG1; F-6), anti-RelB (goat polyclonal IgG; N-17) and secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-goat, anti-rabbit and anti-mouse immunoglobulins were obtained from Santa Cruz (Heidelberg, Germany). β-actin (mouse monoclonal IgG), FITC-labelled 40 000 molecular weight (MW) dextran, Lucifer Yellow and ovalbumin from chicken egg were obtained from Sigma.

The proteasome inhibitors bortezomib (PS-341, Velcade®) from Millenium Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, MA), EPM from Boston Biochem (Cambridge, MA), lactacystin from Biomol, gliotoxin (derived from Gladiocladium fimbriatum) and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) were all resolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −20°.

Generation of DCs

DCs were generated from human healthy donor peripheral CD14+ monocytes, isolated from heparinized peripheral blood by Ficoll (Innotrain, Kronberg, Germany) density-gradient centrifugation and subsequent plastic adherence for 2 hr in culture medium (CM) consisting of RPMI-1640 (Gibco-Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), 2 mm l-glutamine (Sigma), 100 IU penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Gibco-Invitrogen) supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum (FCS; Gibco-Invitrogen). Non-adherent cells were removed, and adherent monocytes were further cultured, as described below. Purity of monocytes prepared in this way was typically 50–60%, as determined by flow cytometry using an FITC-labelled monoclonal antibody to CD14. When a higher purity of monocytes (more than 90%) was required, the cells were negatively isolated with immunomagnetic beads (Dynal, Hamburg, Germany). DCs were generated using a modified method deduced from Faries et al.17 Briefly, CD14+ monocytes were cultured for 48 hr (day 1 to day 3) in serum-free CM, in the presence of 50 ng of GM-CSF and 100 ng of IL-4, to generate immature DCs (iDC). Purity of iDCs was determined by flow cytometry analysis of the cell-surface expression of appropriate markers (CD11c, CD14, CD80, CD86, HLA-DR and CD40). To induce the final maturation of iDCs, cells were treated on day 3 with either a cytokine cocktail consisting of GM-CSF (50 ng/ml), IFN-γ (1000 U/ml) and TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for the last 24 hr and 1 µg/ml of sCD40L for the last 16 hr, or with 100 ng/ml LPS and IFN-γ (1000 U/ml). Purity of the cells generated in this manner ranged between 90 and 95%; putative contaminating populations could be neglected. Mature DCs (mDCs) were defined by their profile of cell-surface molecule expression (CD11c, CD80, CD83, CD86, HLA-DR and CD40), examined and quantified by flow cytometry.

In vitro assay for proteasome activity

The inhibitory profiles of proteasome inhibitors towards proteasomal peptidase activitities in mDCs were measured using a combination of previously described methods,18,19 with minor changes. Briefly, mDCs were generated, as described above, and 5 × 107 cells were lysed in non-ionic lysis buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 7·8; 1% Nonidet P-40, 0·15 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA-2Na). The cell lysate was centrifugated at 19 000 g for 10 min at 4° and the supernatant was used as proteasome extracts. Forty microlitres of supernatant was mixed with 360 µl of substrate buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 8·2; 0·5 mm EDTA-2Na, 1% DMSO, 5 mm ATP) and proteasome inhibitors at different concentrations were added. Thereafter, 10 µl of 100 µm concentrated fluorogenic substrate was added to the mixture. After 30 min of incubation at 37°, fluorescence was measured (excitation, 380 nm; emission, 460 nm) using a SpectrafluorPlus 96-well plate reader equipped with magellan software (Tecan, Crailsheim, Germany). Data quantified with proteasome inhibitors were evaluated against the DMSO results, which were set as 100% of proteasomal peptidase activities.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis of cell-surface receptors of iDCs and mDCs was performed with standard staining and analysis procedures using a FACScan and cellquest software (BD Pharmingen). For the analysis of cell-surface receptors of cells that differentiate from monocytes to iDCs, proteasome inhibitors were added on day 2 for 24 hr to the cell culture, whereas for cells that differentiate from iDCs to mDCs, proteasome inhibitors were added to iDCs on day 3 for 24 hr and 1 hr before induction of final maturation with the cytokine cocktail. Because proteasome inhibitors induce apoptosis in monocytes, iDCs and mDCs, only viable cells were gated and considered for flow cytometric analysis, except for the measurement of apoptosis. For the measurement of cell-surface receptor expression, a viable and homogeneous population of DCs was gated. This gate always contained 95–98% DCs, as determined by staining the cells with CD11c–PE monoclonal antibody and the CD11c-regating procedure. Data were measured as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and calculated as percentage of MFI of inhibitor-incubated cells compared with the MFI of DMSO-incubated cells: (MFI of inhibitor-incubated cells ÷ MFI of DMSO-incubated cells) × 100.

Analysis of apoptosis

Detection of apoptotic cell death was analysed using annexin V–PE from BD Biosciences. Cells were treated for 24 hr with proteasome inhibitors. Before incubation of the cells with PE-conjugated annexin V, according to the manufacturer's instructions, cells were stained with FITC-conjugated antibody raised against CD11c. Thereafter, apoptosis of cells located in a CD11c+ gate was measured and quantified by flow cytometry.

Analysis of endocytosis and macropinocytosis

To determine the effect of proteasome inhibitors on receptor-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis of iDCs, cells were treated, as described previously.20 Briefly, cells were treated for 24 hr with proteasome inhibitors, washed and resuspended in CM supplemented with 10% FCS. Subsequently, cells were incubated with FITC-labelled 40 000 MW dextran (1 mg/ml) or Lucifer Yellow (1 mg/ml), either at 4° (internalization control) or at 37° for 30 min and 60 min. Thereafter, cells were extensively washed four times with ice-cold PBS and analysed by flow cytometry. For measurement of endocytosis and macropinocytosis, a viable and homogeneous population of DCs was gated. This gate always contained 95–98% DCs, as determined by staining the cells with monoclonal CD11c antibody conjugated to PE and a CD11c-regating procedure. Data were measured as MFI.

Quantification of cytokine production

To quantify the amounts of cytokine production by iDCs during differentiation to mDCs, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits, purchased from R & D Systems (Wiesbaden, Germany), were used. iDCs were treated for 1 hr with proteasome inhibitors before maturation with cytokine cocktail in serum-free CM for 24 hr, as described above. Cell culture supernatants were collected, and the amounts of IL-12p40 and IL-12p70 were measured, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunoblotting

For analysis of intracellular protein expression of cell-surface receptors, cells were treated for 24 hr with proteasome inhibitors or DMSO. Whole-cell lysates were prepared by lysing cells in ice-cold radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer for 30 min. The homogenates were centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min at 4°, and the supernatants were used for immunoblot analysis (as described below) using antibodies raised against CD206, HLA-DR and β-actin. For analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear contents of RelA and RelB, iDCs were incubated with proteasome inhibitors or DMSO for 1 hr before inducing final maturation with LPS and IFN-γ for the indicated times. Subsequently, cells were washed and pelleted. Cytoplasmic and nuclear cell extracts were prepared, as previously described, by Schreiber et al.21 Briefly, cell pellets were resuspended in 100 µl of buffer A (0·5% Nonidet P-40, 10 mm EDTA, 10 mm EGTA, 10 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7·9) supplemented with 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT) and one tablet of protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Penzberg, Germany; freshly added) and incubated on ice for 10 min. Nuclei were sedimented by centrifuging the lysates at 1200 g for 10 min. The supernatants were recovered as cytoplasmic extract. The generated pellets were resuspended in 40 µl of buffer B [1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 0·4 m NaCl, 20 mm HEPES (pH 7·9), 5 mm MgCl2, 25% glycerol, with fresh addition as above] and incubated for 10 min on ice with occasional mixing. The suspensions were clarified by centrifuging at 15 000 g for 10 min. The supernatants were recovered as nuclear extracts. Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were rapidly frozen and stored at −80°. Equal amounts of total protein were separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) on 12% Tris–HCl gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes overnight. After blocking with 5% non-fat dry milk for at least 1 hr at room temperature, membranes were incubated for 2 hr with primary antibodies raised against RelA or RelB. Membranes were washed extensively with 0·1% PBS/Tween 20 and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hr at 20°. After additional extensive washing steps, immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence with the Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescence Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). As a control for equal protein loading, membranes were stripped and reprobed with an antibody raised against β-actin.

Allogeneic and autologous T-cell stimulation

For allogeneic DC-mediated T-cell stimulation, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were isolated from the heparinized peripheral blood of HLA-mismatched human healthy donors by Ficoll density-gradient centrifugation and enrichment by immunomagnetic negative isolation (Dynal). For antigen-dependent autologous T-cell stimulation, autologous CD4+ T cells were isolated using the method described for allogeneic T cells. iDCs were pulsed on day 2 of the differentiation procedure with 100 µg/ml ovalbumin and thereafter were differentiated into mDCs, as described above. mDCs were exposed for 24 hr to proteasome inhibitors, washed afterwards extensively with warm PBS, and only viable and non-apoptotic mDCs were counted using Trypan Blue exclusion staining. Cells were subsequently cocultured for 5 days with 2·25 × 106/ml allogeneic CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, or with autologous CD4+ T cells, or without T cells (autoproliferation control) in CM supplemented with 10% FCS at different DC:T-cell ratios and pulsed with 5 µCi/ml of [3H]thymidine for the last 18 hr. Incorporation of [3H]thymidine was quantified using a β-counter (Inotech, Basel, Switzerland). Autoproliferation control of mDCs was subtracted from T-cell proliferation counts.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using excel software. Differences between mean values were assessed using the paired Student's t-test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0·05.

Results

Selective inhibition of proteasomal CPA in DCs by bortezomib, EPM and lactacystin

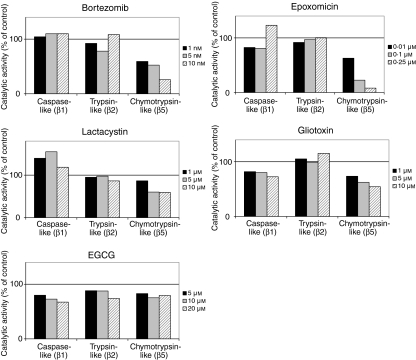

We investigated the inhibitory profiles of various proteasome inhibitors towards proteasomal caspase-like, trypsin-like and chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity. Using fluorogenic oligopeptidyl substrates specific for the respective peptidase activity, we found that bortezomib at 1, 5 and 10 nm, EPM at 0·01, 0·1 and 0·25 µm, and lactacystin at 5 and 10 µm inhibit the proteasomal β5 subunit-associated CPA in human monocyte-derived mDCs (Fig. 1). Proteasomal caspase-like and trypsin-like peptidase activities were not inhibited by bortezomib, EPM and lactacystin (Fig. 1). The fungal metabolite gliotoxin, which is known to be a non-competitive proteasome inhibitor,22 inhibited proteasomal CPA and also caspase-like peptidase activity in DCs (Fig. 1). The green tea polyphenol EGCG, another biological proteasome inhibitor,23 was found to inhibit proteasomal caspase-like and trypsin-like peptidase activities, and CPA, in DCs (Fig. 1). Having identified inhibitors (bortezomib, EPM, lactacystin) that selectively inhibit proteasomal CPA in DCs, we were able to investigate the role of proteasomal CPA in various processes in human DCs.

Figure 1.

Inhibitory profiles of the proteasome inhibitors bortezomib, epoxomicin, lactacystin, gliotoxin and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), determined in lysates of mature dendritic cells (mDCs). Lysates were incubated for 30 min with the proteasome inhibitors at the indicated concentrations and with the fluorogenic oligopeptidyl substrates Boc-LLE-amc (caspase-like peptidase activity), Boc-LRR-amc (trypsin-like peptidase activity) and Z-GGL-amc (chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity). Catalytic activities were determined as described in the Materials and methods. For each inhibitor, one representative experiment out of four independent experiments is shown.

Proteasomal CPA is required for expression of important cell surface receptors in DCs

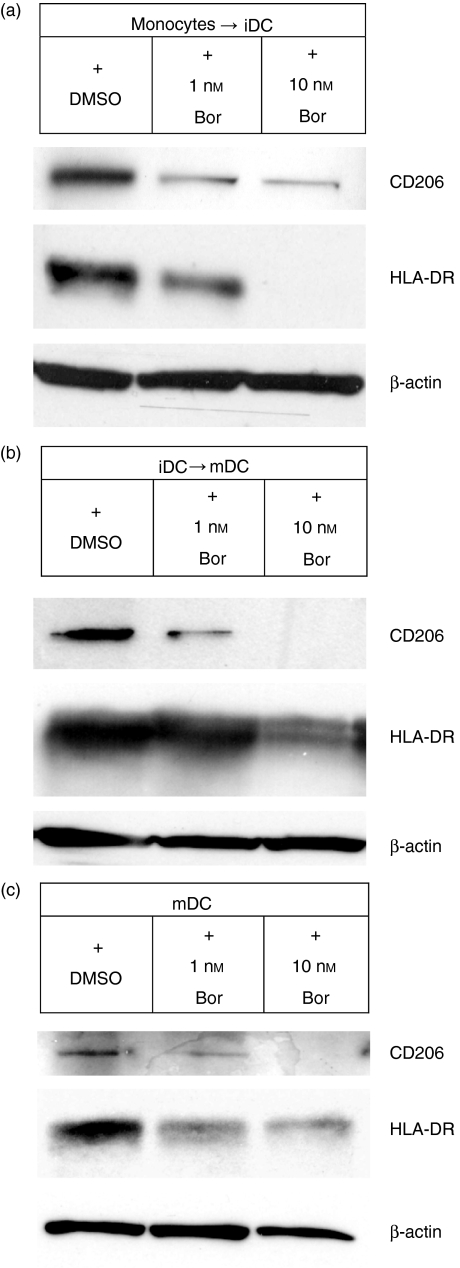

At different stages of differentiation and maturation, DCs express a characteristic profile of cell-surface receptors required for proper DC immune functions, such as endocytosis of macromolecular antigens, antigen presentation, and interaction with, and stimulation of, T cells.1,2 We investigated, in the presence of proteasome inhibitors targeting CPA, cell-surface expression of such immune receptors during differentiation from monocytes to iDCs (Fig. 2a), during maturation from iDCs to mDCs (Fig. 2b), and in completely differentiated and matured mDCs (Fig. 2c). Highly pure and viable populations of DCs expressing CD11c were used to investigate the modulation of cell-surface receptor expression induced by the proteasome inhibitors (Fig. 2d). Bortezomib, EPM and lactacystin inhibited the cell-surface expression of CD86 and CD40 (required for T-cell interaction and stimulation), HLA-DR (required for peptide antigen presentation) and CD206 (macrophage mannose receptor, required for endocytosis of macromolecular antigens) during differentiation from monocytes to iDC (Fig. 2a). During maturation from iDCs to mDCs (Fig. 2b), and in completely differentiated and matured mDCs (Fig. 2c), the proteasome inhibitors targeting CPA inhibited the cell-surface expression of CD86, CD80 and CD40 (required for T-cell interaction and stimulation), HLA-DR (required for peptide antigen presentation), and CD206 and CD209 (DC-SIGN, required for endocytosis of macromolecular antigens and T-cell interaction). We next investigated the intracellular expression of CD206 and HLA-DR proteins, those cell-surface receptors displaying the most prominent inhibition of cell-surface expression in response to inhibition of CPA (Fig. 2a–c), in the same cells exposed for 24 hr to 1 and 10 nm bortezomib (Fig. 3a–c). Similarly to the results obtained by flow cytometry, intracellular expression of CD206 and HLA-DR was markedly reduced in DCs exposed to proteasome inhibitors targeting CPA, whereas the intracellular expression of β-actin, a housekeeping protein unrelated to DC function, remained unchanged. Thus, proteasomal CPA is required for the cell-surface expression of important immune receptors in DCs.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of cell-surface expression of immune receptors in dendritic cells (DCs) exposed to proteasome inhibitors targeting chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity (CPA) at different stages of differentiation. (a) Cells were exposed for 24 hr to the indicated concentrations of bortezomib (Bor), epoxomicin (EPM) or lactacystin (Lac) during the differentiation from monocytes to immature DCs (iDCs). (b) Cells were exposed for 24 hr to the indicated concentrations of bortezomib, EPM or lactacystin during the differentiation from iDCs to mature DCs (mDCs). (c) mDC were exposed for 24 hr to the indicated concentrations of bortezomib, EPM or lactacystin. (d) For measurement of cell-surface receptor expression, a viable and homogeneous population of DCs was gated (right). This gate always contained 95–98% DCs, as determined by staining the cells with anti-CD11c–phycoerythrin (PE) monoclonal antibody and the CD11c-regating procedure (right). Data were measured as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and calculated as percentage MFI of inhibitor-incubated cells compared with the MFI of dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO)-incubated cells: (MFI of inhibitor-incubated cells ÷ MFI of DMSO-incubated cells) × 100. Data are given as mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01 (paired Student's t-test) versus DMSO control.

Figure 3.

Immunoblot analysis of intracellular expression of CD206 and human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR in lysates of cells incubated for 24 hr with the indicated concentrations of bortezomib (Bor). (a) Cells during the differentiation from monocytes to immature dendritic cells (iDCs). (b) Cells during the differentiation from iDCs to mature dendritic cells (mDCs). (c) mDCs. For analysis of expression of housekeeping proteins unrelated to DC function, the amounts of β-actin were determined in whole-cell lysates. DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide.

Proteasomal CPA is required for the maturation of iDCs into mDCs

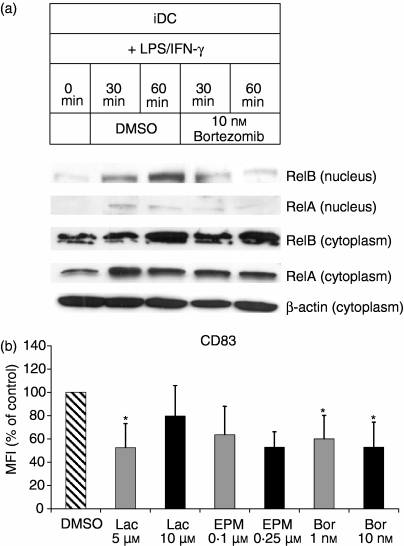

RelA (p65) and RelB, transcription factors of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)/Rel family, are essential for proper differentiation and maturation of DCs,24,25 and rapid cytoplasmic-nuclear translocation of RelA and RelB is a hallmark of, and required for, the maturation of human DCs.26–28 Therefore, we investigated cytoplasmic–nuclear translocation of RelA and RelB in iDCs exposed to bortezomib and induced to mature with LPS and IFN-γ. Figure 4 (a) shows that 10 nm bortezomib inhibits nuclear accumulation of RelA and RelB, as analysed by immunoblotting RelA and RelB in the nuclear fractions of the cells. The cytoplasmic levels of RelA and RelB remained unchanged in response to treatment of the cells with bortezomib. For analysis of metabolism of housekeeping proteins unrelated to DC maturation, the concentration of β-actin was determined in cytoplasmic fractions and demonstrated to remain unchanged in response to treatment of the cells with bortezomib. Similar results were obtained with EPM and lactacystin (data not shown). Accordingly, iDCs induced to mature in the presence of bortezomib, EPM and lactacystin exhibited an impaired cell-surface expression of CD83, the general marker for mDCs (Fig. 4b), demonstrating that proteasomal CPA is required for the maturation of DCs.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of nuclear translocation and accumulation of RelB and RelA in immature dendritic cells (iDCs) exposed to bortezomib (Bor). (a) iDCs were incubated with 10 nm bortezomib for 1 hr before the induction of maturation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ). The amounts of RelB and RelA proteins were determined in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of the cells by immunoblotting at the indicated time points. For analysis of expression of housekeeping proteins unrelated to DC function, the amounts of β-actin were determined in the cytoplasmic fractions. Immunoblots were performed in triplicate, with similar results obtained on each occasion. Similar results were obtained with epoxomicin (EPM) and lactacystin. (b) Inhibition of maturation of iDCs exposed to proteasome inhibitors targeting chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity (CPA). iDCs were incubated with bortezomib, EPM or lactacystin for 1 hr prior to induction of maturation. Cell-surface expression of CD83, the general marker for mature dendritic cells (mDCs), was analysed after 24 hr by flow cytometry, as described in the Materials and methods. Only viable and non-apoptotic cells were analysed. Data are given as mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. *P < 0·05 (paired Student's t-test) versus the dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) control.

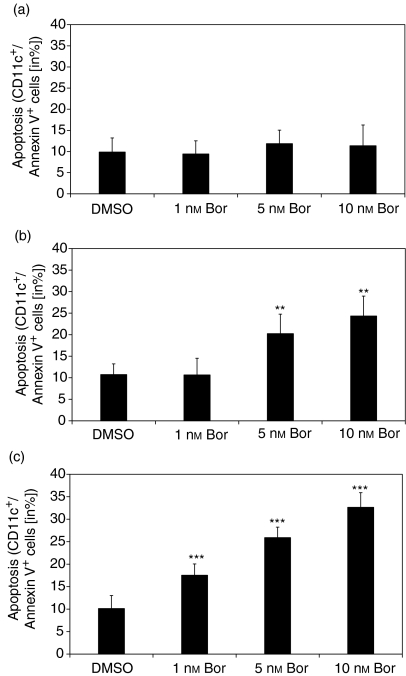

Induction of apoptosis in DCs following inhibition of proteasomal CPA

Figure 5(a) shows that bortezomib at 1, 5 and 10 nm, concentrations sufficient for inhibition of CPA in DCs (Fig. 1), failed to induce apoptosis in monocytes (Fig. 5a). However, at the same concentrations, bortezomib induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner in iDCs (Fig. 5b) and mDCs (Fig. 5c). Similar results were obtained using EPM at 0·01, 0·1 and 0·25 µm, and lactacystin at 5 and 10 µm (data not shown). Cells were cultured for 24 hr in the presence of the proteasome inhibitors. Culture of cells for 48 hr in the presence of the proteasome inhibitors did not markedly increase the percentages of apoptotic cells (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Induction of apoptosis in dendritic cells (DCs) exposed to bortezomib (Bor). (a) Monocytes, (b) immature dendritic cells (iDCs) and (c) mature dendritic cells (mDCs) were incubated for 24 hr with the indicated concentrations of bortezomib. Apoptosis was analysed by flow cytometry. CD11c+ cells were gated and analysed for annexin V bindings, as described in the Materials and methods. Similar results were obtained using epoxomicin (EPM) and lactacystin. Data are given as the mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of four independent experiments carried out in triplicate. **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·0005 (paired Student's t-test) versus the dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) control.

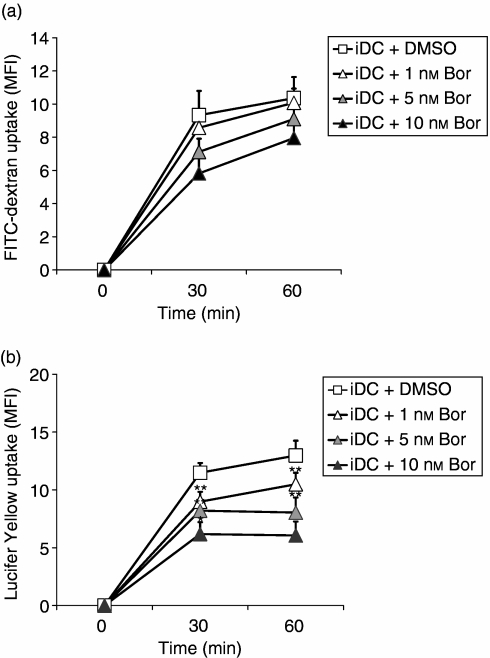

Proteasomal CPA is required for receptor-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis of iDCs

Using FITC-labelled 40 000 MW dextran, a ligand for the C-type lectins CD206 (macrophage mannose receptor) and CD209 (DC-SIGN), which mediate endocytosis of macromolecular antigens, we found that inhibition of proteasomal CPA by pre-incubation of the cells for 24 hr with bortezomib at 1, 5 and 10 nm inhibited receptor-mediated antigen uptake in viable and non-apoptotic DCs (Fig. 6a), probably as a result of considerably reduced cell-surface expression of CD206 and CD209 in iDCs following the inhibition of proteasomal CPA (Fig. 2a,b). Also, the capacity of fluid-phase antigen uptake (macropinocytosis), determined by measuring Lucifer Yellow uptake, was inhibited in viable and non-apoptotic iDCs in response to inhibition of proteasomal CPA by pre-incubation of the cells for 24 hr with bortezomib at 1, 5 and 10 nm (Fig. 6b). Similar results were obtained using EPM at 0·01, 0·1 and 0·25 µm, and lactacystin at 5 and 10 µm (data not shown). These effects could not be attributed to the induction of apoptosis in DCs exposed to the proteasome inhibitors, because only viable and non-apoptotic cells were gated and analysed by flow cytometry, as demonstrated in Fig. 2(d).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of receptor-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis in immature dendritic cells (iDCs) exposed to bortezomib (Bor). (a) Inhibition of receptor-mediated endocytosis of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled 40 000 molecuar weight (MW) dextran in iDCs exposed for 24 hr to the indicated concentrations of bortezomib. Intracellular accumulation of FITC-labelled 40 000 MW dextran was analysed at the indicated time points by flow cytometry, as described in the Materials and methods. (b) Inhibition macropinocytosis of Lucifer Yellow in iDCs exposed for 24 hr to the indicated concentrations of bortezomib. Intracellular accumulation of Lucifer Yellow was analysed at the indicated time points by flow cytometry, as described in the Materials and methods. Measurement of receptor-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis was measured as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and by using a CD11c-regating procedure, as described in Fig. 2(d). Similar results were obtained using epoxomicin (EPM) and lactacystin. Data given represent the mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of four independent experiments carried out in triplicate. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01 (paired Student's t-test) versus dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) control.

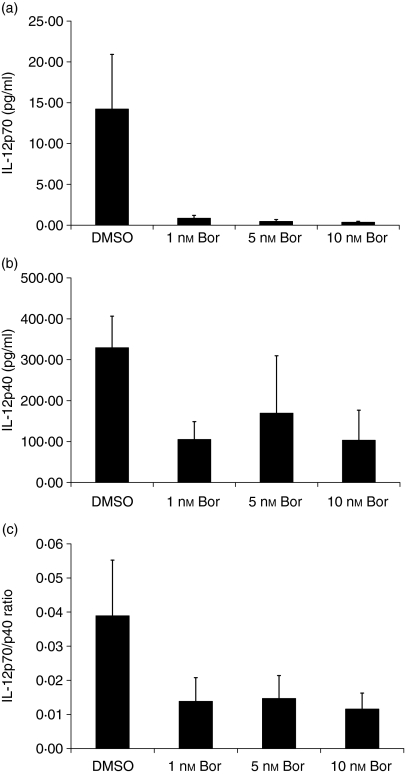

Proteasomal CPA is required for the production of IL-12 in mDCs

Mature DCs produce both agonistic (bioactive) IL-12p70 (p35/p40) heterodimers and antagonistic IL-12p40 homodimers, and the IL-12p70/IL-12p40 ratio finally determines the extent of T-helper cell 1 instruction and stimulation. Therefore, we determined the production of IL-12p70 and IL-12p40 and the IL-12p70/IL-12p40 ratio during maturation of iDCs into mDCs and simultaneous exposure of the cells for 24 hr to bortezomib at 1, 5 and 10 nm. Inhibition of proteasomal CPA by bortezomib markedly reduced the production of IL-12p70 (Fig. 7a) and IL-12p40 (Fig. 7b) in a dose-dependent manner. The IL-12p70/IL-12p40 ratio, which accurately reflects the functional potential of total IL-12 synthesis, is markedly reduced in response to inhibition of proteasomal CPA by bortezomib (Fig. 7c).

Figure 7.

Inhibition of production of interleukin (IL)-12 in dendritic cells (DCs) exposed to bortezomib (Bor). (a) Production of agonistic (bioactive) IL-12p70 heterodimers, (b) production of antagonistic IL-12p40 homodimers and (c) the resulting IL-12p70/IL-12p40 ratio were quantified during the maturation of iDCs into mature dendritic cells (mDCs) and simultaneous exposure of the cells for 24 hr to the indicated concentrations of bortezomib. The concentrations of IL-12p70 and IL-12p40 proteins were quantified in the cell culture supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), as described in the Materials and methods. Data given represent the mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of four independent experiments in triplicate.

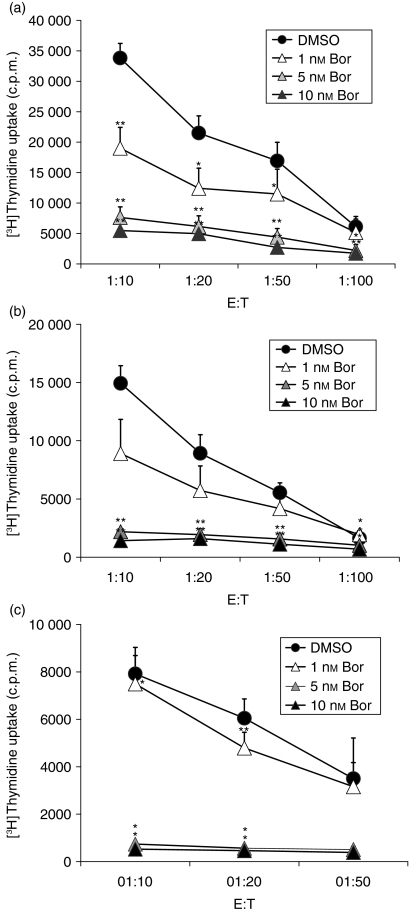

Inhibition of proteasomal CPA in mDCs impairs mDC-induced allogeneic and autologous T-cell stimulation

To verify the functional consequences of the multiple effects occurring in response to inhibition of CPA in DCs, we determined the capacity of mDCs exposed to bortezomib to stimulate allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and autologous CD4+ T cells. Mature DCs, after exposure for 24 hr to bortezomib at 1, 5 and 10 nm, displayed a markedly reduced capacity to stimulate allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 8a,b) and autologous CD4+ T cells after antigen pulsing of the DCs with ovalbumin (Fig. 8c). These effects could not be attributed to the induction of apoptosis in DCs exposed to bortezomib, because only viable and non-apoptotic DCs were counted and used for T-cell stimulation.

Figure 8.

Inhibition of mature dendritic cell (mDC)-mediated allogeneic and autologous T-cell stimulation by bortezomib (Bor). Stimulation of (a) allogeneic CD4+ T cells, (b) allogeneic CD8+ T cells and (c) autologous CD4+ T cells by mDCs after exposure of mDCs for 24 hr to the indicated concentrations of bortezomib. Stimulation experiments were carried out at DC:T-cell ratios of 1 : 10, 1 : 20, 1 : 50 and 1 : 100. For stimulation of autologous CD4+ T cells, DCs were pulsed with ovalbumin, as described in the Materials and methods. Only viable and non-apoptotic DCs were counted and used for T-cell stimulation. Data given represent the mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of five independent experiments. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01 (paired Student's t-test) versus the dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) control. E:T, effector:target ratio.

Discussion

The ubiquitin–proteasome pathway plays a pivotal role in the regulation and maintenance of basic cellular processes, including differentiation, proliferation, cell cycling, survival, apoptosis, senescence, gene transcription, signal transduction, immune activation, and peptide antigen processing and presentation.9,11,29 The identification and use of selective synthetic and biological inhibitors of proteasomal proteolytic activities14–16 have principally contributed to the identification of essential functions of the 26S proteasome in various processes and pathways of eukaryotic cells.11,30 In particular, inhibition of proteasomal function by proteasome inhibitors induces apoptosis preferentially in rapidly proliferating and neoplastic cells.11,31–33 These findings have recently paved the way for the use of proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy.34 Moreover, proteasome inhibitors have been shown to suppress activation, proliferation, survival and cytokine synthesis of mouse and human T cells,35–39 and recent studies in rodents suggest that proteasome inhibitors can be used as immunosuppressive agents for the treatment of deregulated T-cell-mediated immune responses, including those that contribute to the pathogenesis of polyarthritis, psoriasis, allograft rejection and graft-versus-host disease.36,38,40,41

In the present study, we have identified proteasome inhibitors that inhibit, in human monocyte-derived DCs selectively, the proteasomal CPA, which is located in the proteasomal β5 subunit12,13 and which constitutes the main proteolytic site of proteasomal protein degradation in mammalian cells.42 We show herein that inhibition of CPA suppresses essential and basic functions of human DCs, including differentiation, maturation, survival, cell-surface receptor expression, receptor-mediated endocytosis of macromolecular antigens, macropinocytosis, cytokine synthesis, and allogeneic and autologous T-cell stimulation. In particular, we show that bortezomib, EPM and lactacystin, which selectively inhibit CPA in the DCs investigated, suppress cell-surface expression of HLA-DR, CD40 and CD206 during differentiation from monocytes to iDCs, suppress cell-surface expression of HLA-DR, CD86, CD80, CD40, CD206, CD209 and CD83 during maturation of iDCs into mDCs, and suppress cell-surface expression of HLA-DR, CD86, CD80, CD40 and CD206 in mDCs. Moreover, as demonstrated for CD206 and HLA-DR, intracellular expression of functional cell-surface receptors of DCs is suppressed in response to the inhibition of proteasomal CPA in all differentiation stages of DCs investigated. This suggests that the expression of cell-surface receptors which are essential for DC immune function depends, at least in part, on proteasomal CPA. Accordingly, a previous study demonstrated suppression of cell-surface expression of HLA-DR and CD86 in human monocyte-derived mDCs treated with the proteasome inhibitor PSI.43 However, this suppression could not be accurately attributed to an exclusive inhibition of CPA, because PSI has been shown to inhibit, additionally, proteasomal trypsin-like and caspase-like peptidase activities.44

We next show that inhibition of proteasomal CPA by bortezomib, EPM and lactacystin induces apoptosis in monocyte-derived iDCs and mDCs, but not in monocytes. Induction of apoptosis by proteasome inhibitors is a general feature observed in rapidly proliferating and neoplastic cells, but not in resting and well-differentiated cells.11 This also holds true for T cells, which are prone to undergo proteasome inhibitor-induced apoptosis preferentially in the activated and proliferating state,35,37,39 suggesting that proteasomal activity is essential for the survival of T cells during cell cycle progression and proliferation. However, we show here that non-proliferating (iDCs and mDCs) and terminally differentiated (mDCs) cells, but not non-proliferating and differentiated monocytes, undergo apoptosis when proteasomal CPA is inhibited, suggesting that CPA is essential for survival of iDCs and mDCs. Induction of apoptosis in iDCs by bortezomib has been recently demonstrated by Nencioni et al.45 and we herein complete their results.

Post-translational cytosolic induction and rapid nuclear translocation of RelA (p65) and RelB, transcription factors of the NF-κB/Rel family, is a hallmark of, and essential for, proper differentiation and final maturation of human DCs.26–28 RelA and RelB form heterodimers with NF-κB p50 and NF-κB p50 or p52, respectively. These heterodimers are complexed and sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitory IκB proteins.46 Only after phosphorylation, ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of inhibitory IκB proteins, can RelA and RelB heterodimers translocate into the nucleus to act as transcriptional activators of target genes governing differentiation, survival and immune regulation.46 We show herein that inhibition of proteasomal CPA suppresses nuclear translocation and accumulation of RelA and RelB in iDCs rapidly after induction of maturation with LPS and IFN-γ. This may occur mainly as a result of impaired proteasomal degradation of inhibitory IκB, thereby retaining RelA and RelB complexes in the cytoplasm. However, we cannot exclude additional and more indirect effects of proteasomal CPA inhibition finally leading to the suppression of nuclear translocation of RelA and RelB. We demonstrate that inhibition of proteasomal CPA impairs maturation of DCs, as evidenced by reduced expression of CD83, a general marker of DC maturity,47 in DCs induced to undergo maturation in the presence of proteasome inhibitors that selectively inhibit proteasomal CPA. This inhibition of maturation may appear as a functional consequence of impaired nuclear translocation of RelA and RelB in response to the inhibition of proteasomal CPA.

Receptor-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis constitute essential and characteristic properties of iDCs that ensure permanent monitoring and capture of foreign antigens in peripheral tissues, a prerequisite for effective MHC-mediated peptide antigen presentation and initiation of antigen-specific T-cell responses.20,48 Using FITC-labelled 40 000 MW dextran as a ligand for the C-type lectins CD206 (macrophage mannose receptor) and CD209 (DC-SIGN), which are essential for receptor-mediated endocytosis of macromolecular antigens, we demonstrated that inhibition of proteasomal CPA impairs receptor-mediated antigen uptake in iDCs, probably as a result of considerably reduced cell-surface expression of CD206 and CD209 in iDCs exposed to proteasome inhibitors targeting CPA. Moreover, macropinocytosis, a general mechanism for water and fluid-phase antigen uptake mediated by transmembrane channels known as aquaporins 3 and 7,48 is impaired in iDCs exposed to proteasome inhibitors targeting CPA. The mechanism(s) underlying the impairment of macropinocytosis might be reduced expression and/or alteration of channel potential or of transmembrane structure and organization of aquaporins in response to the inhibition of proteasomal CPA that finally awaits further investigation.

Production of IL-12 constitutes an important feature functionally associated with DC activation and T-helper cell 1 instruction and stimulation.1,49 Therefore, we determined, in mDC exposed to proteasome inhibitors targeting CPA, the synthesis of bioactive IL-12p70 heterodimers and antagonistic IL-12p40 homodimers and the ratio of IL-12p70 and IL-12p40 production, which accurately reflects the functional potential of total IL-12 synthesis in DCs.50 IL-12p70 production and the ratio of IL-12p70/IL-12p40 production are drastically decreased in mDCs in response to inihibition of proteasomal CPA, strongly suggesting that CPA is essential for induction and regulation of IL-12 production in human DCs. These findings complete the results of a previous study showing that the proteasome inhibitor PSI, which inhibits proteasomal chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like and caspase-like peptidase activities,44 abolishes LPS-induced mRNA expression of IL-12p40 in murine peritoneal macrophages.51

To assess the functional consequences of the pleiotropic inhibitory effects induced by the inhibition of proteasomal CPA in human DCs, we finally demonstrated that mDCs exposed to proteasome inhibitors targeting CPA have a reduced capacity to stimulate allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and autologous CD4+ T cells after antigen pulsing of the DCs. This might be predominately a result of impaired expression of cell-surface receptors, including CD80, CD86, CD40 and HLA-DR, that are required for mDC-mediated T-cell costimulation and antigen presentation. Moreover, inhibition of IL-12 production by mDCs exposed to proteasome inhibitors targeting CPA may also contribute to the impaired stimulation of allogeneic and autologous T cells.

In conclusion, we demonstrate, in this study, that the inhibition of proteasomal CPA impairs basic and essential functions of human DCs, pointing out a pivotal role of the CPA-harbouring proteasomal β5 subunit in DC physiology and immune function. Inhibition of proteasomal CPA by targeting β5 subunit expression, or by proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib, EPM and lactacystin, may constitute a novel strategy for therapeutic immunomodulation in transplantation and autoimmunity.

Acknowledgments

The excellent technical assistance of Regina Seemuth, Martina Kutsche-Bauer and Gabriele Schmeckenbecher is gratefully acknowledged.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CM

culture medium

- CPA

chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity

- DCs

dendritic cells

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EGCG

epigallocatechin-3-gallate

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EPM

epoxomicin

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GM-CSF

granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HLA

human leucocyte antigen

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- iDC

immature DC

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IL

interleukin

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- mDC

mature DC

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensities

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MW

molecular weight

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κb

- rh

recombinant human

- PE

phycoerythrin

- RIPA

radio immunoprecipitation assay

- sCD40L

soluble CD40 ligand

- SDS–PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TNF

tumour necrosis factor

References

- 1.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woltman AM, van Kooten C. Functional modulation of dendritic cells to suppress adaptive immune responses. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:428–41. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0902431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Dendritic cells: regulators of alloimmunity and opportunities for tolerance induction. Immunol Rev. 2003;196:125–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-065x.2003.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerundolo V, Hermans IF, Salio M. Dendritic cells: a journey from laboratory to clinic. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:7–10. doi: 10.1038/ni0104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figdor CG, de Vries IJ, Lesterhuis WJ, Melif CJ. Dendritic cell immunotherapy: mapping the way. Nat Med. 2004;10:475–80. doi: 10.1038/nm1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy A, Westwood JA, Teng MW, Moeller M, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH. Gene modification strategies to induce tumor immunity. Immunity. 2005;22:403–14. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glickman MH, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin–proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:373–428. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin proteolytic system. Neurology. 2006;66(Suppl. 1):S7–S19. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000192261.02023.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voges D, Zwickl P, Baumeister W. The proteasome: a molecular machine designed for controlled proteolysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:1015–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naujokat C, Hoffmann S. Role and function of the 26S proteasome in proliferation and apoptosis. Lab Invest. 2002;82:965–80. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000022226.23741.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dick TP, Nussbaum AK, Deeg M, et al. Contribution of proteasomal beta-subunits to the cleavage of peptide substrates analyzed with yeast mutants. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25637–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kisselev AF, Akopian TN, Castillo V, Goldberg AL. Proteasome active sites allosterically regulate each other, suggesting a cyclical bite-chew mechanism for protein breakdown. Mol Cell. 1999;4:395–402. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groll M, Huber R. Inhibitors of the eukaryotic 20S proteasome core particle: a structural approach. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams J, Kauffman M. Development of the proteasome inhibitor Velcade (bortezomib) Cancer Invest. 2004;22:304–11. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120030218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaczynska M, Osmulski PA. Small-molecule inhibitors of proteasome activity. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;301:3–22. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-895-1:003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faries MB, Bedrosian I, Xu S, et al. Calcium signaling inhibits interleukin-12 production and activates CD83+ dendritic cells that induce Th2 cell development. Blood. 2001;98:2489–97. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamauchi M, Suzuki K, Kodama S, Watanabe M. Abnormal stability of wild-type p53 protein in a human lung carcinoma cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:483–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berkers CR, Verdoes M, Lichtman E, et al. Activity probe for in vivo profiling of the specificity of proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Nat Methods. 2005;2:357–62. doi: 10.1038/nmeth759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sallusto F, Cella M, Danieli C, Lanzavecchia A. Dendritic cells use macropinocytosis and the mannose receptor to concentrate macromolecules in the major histocompatibility complex class II compartment. Downregulation by cytokines and bacterial products. J Exp Med. 1995;182:389–400. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schreiber E, Matthias E, Müller M, Schaffner W. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts’, prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6419. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroll M, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Bachelerie F, Thomas D, Friguet B, Conconi M. The secondary fungal metabolite gliotoxin targets proteolytic activities of the proteasome. Chem Biol. 1999;6:689–98. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nam S, Smith DM, Dou QP. Ester bond-containing tea polyphenols potently inhibit proteasome activity in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13322–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouaaz F, Arron J, Zheng Y, Choi Y, Beg AA. Dendritic cell development and survival require distinct NF-κB subunits. Immunity. 2002;16:257–70. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burkly L, Hession C, Ogata L, et al. Expression of relB is required for the development of thymic medulla and dendritic cells. Nature. 1995;373:531–6. doi: 10.1038/373531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumann M, Fries H, Scheicher C, Keikavoussi P, Kolb-Maurer A, Brocker E, Serfling E, Kampgen E. Differential expression of Rel/NF-κB and octamer factors is a hallmark of the generation and maturation of dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;95:277–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ammon C, Mondal K, Andreesen R, Krause SW. Differential expression of the transcription factor NF-κB during human mononuclear phagocyte differentiation to macrophages and dendritic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:99–105. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saccani S, Pantano S, Natoli G. Modulation of NF-κB activity by exchange of dimers. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1563–74. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krüger E, Kuckelkorn U, Sijts A, Kloetzel PM. The components of the proteasome system and their role in MHC class I antigen processing. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;148:81–104. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalton WS. The proteasome. Semin Oncol. 2004;6(Suppl. 16):3–9. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drexler HCA. Activation of the cell death program by inhibition of proteasome function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:855–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen C, Lin H, Karanes C, Pettit GR, Chen BD. Human THP-1 monocytic leukemic cells induced to undergo monocytic differentiation by bryostatin 1 are refractory to proteasome inhibitor-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4377–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naujokat C, Sezer O, Zinke H, Leclere A, Hauptmann S, Possinger K. Proteasome inhibitors induce caspase-dependent apoptosis and accumulation of p21 in human immature leukemic cells. Eur J Haematol. 2000;65:221–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2000.065004221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voorhees PM, Orlowski RZ. The proteasome and proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:189–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Luo H, Chen H, Duguid W, Wu J. Role of proteasomes in T cell activation and proliferation. J Immunol. 1998;160:788–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo H, Wu Y, Qi S, Wan X, Chen H, Wu J. A proteasome inhibitor prevents mouse heart allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2001;72:196–202. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200107270-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naujokat C, Daniel V, Bauer TM, Sadeghi M, Opelz G. Cell cycle- and activation-dependent regulation of cyclosporin A-induced T cell apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:347–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun K, Welniak LA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, et al. Inhibition of acute graft-versus-host disease with retention of graft-versus-tumor effects by the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8120–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401563101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blanco B, Perez-Simon JA, Sanchez-Abarca LI, et al. Bortezomib induces depletion of alloreactive T lymphocytes and decreases the production of Th1 cytokines. Blood. 2006;107:3575–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palombella VJ, Conner EM, Fuseler JW, et al. Role of the proteasome and NF-κB in streptococcal cell wall-induced polyarthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15671–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zollner TM, Podda M, Pien C, Elliot PJ, Kaufmann R, Bohncke WH. Proteasome inhibition reduces superantigen-mediated T cell activation and the severity of psoriasis in a SCID-hu model. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:671–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI12736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kisselev AF, Callard A, Goldberg AL. Importance of different proteolytic sites of the proteasome and the efficacy of inhibitors varies with the protein substrate. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8582–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshimura S, Bondeson J, Brennan FM, Foxwell BMJ, Feldmann M. Role of NF-κB in antigen presentation and development of regulatory T cells elucidated by treatment of dendritic cells with the proteasome inhibitor PSI. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1883–93. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200106)31:6<1883::aid-immu1883>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bury M, Mlynarczuk I, Pleban E, Hoser G, Kawiak J, Wojcik C. Effects of an inhibitor of tripeptidyl peptidase II (Ala-Ala-Phe-chloromethylketone) and its combination with an inhibitor of chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome (PSI) on apoptosis, cell cycle and proteasome activity in U937 cells. Folia Hystochem Cytobiol. 2001;39:131–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nencioni A, Garutti A, Schwarzenber K, et al. Proteasome inhibitor-induced apoptosis in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Eur Immunol. 2006;36:681–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-κB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou LJ, Tedder TF. CD14+ blood monocytes can differentiate into functionally mature CD83+ dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2588–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Baey A, Lanzavecchia A. The role of aquaporins in dendritic cell macropinocytosis. J Exp Med. 2000;191:743–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rissoan MC, Soumelis V, Kadowaki N, Grouard G, Briere F, de Waal Malefyt R, Liu YJ. Reciprocal control of T helper cell and dendritic cell differentiation. Science. 1999;283:1183–6. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5405.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luft T, Luetjens P, Hochrein H, et al. IFN-alpha enhances CD40 ligand-mediated activation of immature monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2002;14:367–80. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang JS, Feng WG, Li CL, Wang XY, Chang ZL. NF-κB regulates the LPS-induced expression of interleukin 12p40 in murine peritoneal macrophages: roles of PKC, PKA, ERK, p38 MAPK, and proteasome. Cell Immunol. 2000;204:38–45. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2000.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]