Abstract

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is becoming an evermore useful tool in oncology but is frequently limited by side-effects caused by a lack of targeting of the photosensitizer. This problem can often be circumvented by the conjugation of photosensitizers to tumour-specific monoclonal antibodies. An alternative is the use of single chain (sc) Fv fragments which, whilst retaining the same binding specificity, are more efficient at penetrating tumour masses because of their smaller size; and are more effectively cleared from the circulation because of the lack of an Fc domain. Here we describe the conjugation of two isothiocyanato porphyrins to colorectal tumour-specific scFv, derived from an antibody phage display library. The conjugation procedure was successfully optimized and the resulting immunoconjugates showed no loss of cell binding. In vitro assays against colorectal cell lines showed these conjugates had a selective photocytotoxic effect on cells. Annexin V and propidium iodide staining of treated cells confirmed cell death was mediated principally via an apoptotic pathway. This work suggests that scFv : porphyrin conjugates prepared using isothiocyanato porphyrins show promise for use as targeted PDT agents.

Keywords: photodynamic therapy, scFv, phage display, porphyrin, bioconjugation

Introduction

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a non-invasive treatment that involves the accumulation of a photosensitizing agent in solid tumours followed by the localized delivery of light of the correct wavelength to cause activation of the photosensitizer (PS), which, in the presence of oxygen, leads to the in situ generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause damage to cellular components and, ultimately, necrosis or apoptosis.1 The main drawback of almost all current PDT with respect to oncology, is the low selectivity of PS for cancer over normal tissue, that can result in acute damage to surrounding normal tissue, and prolonged skin photosensitivity.2,3

Efforts to enhance the specificity of photodynamic action have led to the use of biomolecules as carriers of photosensitizers to increase drug selectivity.4 One very attractive way to achieve this, is by coupling of the photosensitizers to monoclonal antibodies (mAb) that are specific for tumour-associated antigens.5 A number of studies have demonstrated the feasibility of coupling photosensitizers to a variety of antibodies for tumour targeting.6–10 However, it has been observed, particularly in vivo, that the large size of a mAb limits the ability of the conjugate to penetrate solid, deep-seated and poorly vascularized tumours.11 Antibody fragments such as scFv (single chain Fv fragments) have been shown to have greater and faster tissue penetration, more rapid blood clearance and significantly lower kidney uptake.12 These characteristics make them potentially more useful drug carriers of radioisotopes13 and, if an efficient conjugation method can be developed, photosensitizers.

A well-established technique for generating novel scFv fragments, of fully human origin, is bacteriophage display.14 In a bacteriophage antibody library each phage particle contains antibody genes fused to a coat protein gene, which results in scFv antibody fragments being displayed on the phage surface. The linkage between genotype and phenotype enables very rare antibodies displayed on phage to be selected from vast repertoires by multiple rounds of affinity purification on antigen. This technique has been employed by a number of groups to produce several potentially useful scFv for use in cancer immunotherapy.12,15

The development of a successful immunoconjugate requires the retention of the binding ability of the antibody and the killing ability of the photosensitizer. Most previous mAb : photosensitizer conjugates have been produced using activated esters or carbodiimide coupling of carboxy substituted photosensitizers, or alternatively by the use of intermediate polymeric carrier molecules. Both of these methodologies are limited by problems with antibody crosslinking and/or changes to the photophysics of the photosensitizer.8,16,17

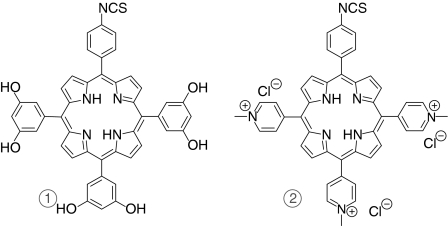

To address this, a number of porphyrin photosensitizers have been developed by our group, that incorporate a reactive isothiocyanate group into the molecular structure.18,19 These photosensitizers allow conjugation to biomolecules under very mild conditions (with no intermediates or by-products), through direct reaction of the reactive isothiocyanate group (NCS) and the primary amino group on the side chain of lysine residues. Conjugation of polar derivatives of these compounds to bovine serum albumin was demonstrated with minimal non-specific binding19 and more recently efficient conjugation to mAb was reported.10 The two NCS bearing porphyrins chosen for this study have been engineered to ensure water solubility, thus facilitating bioconjugation. The first NCS porphyrin (PS1) bears six hydroxyl groups on the three phenyl rings which do not bear the NCS group, while the second (PS2) presents three positively charged quaternized nitrogens. Selection of these photosensitizers thus allows the effect of neutral and charged solubilizing groups on photodynamic activity to be investigated for ScFv conjugates.

In the present study we describe the expression of colorectal tumour-specific scFv, previously isolated from a phage antibody display library20 their conjugation to two different isothiocyanato porphyrins and subsequent characterization.

Materials and methods

Expression of scFv

Colorectal tumour-cell specific scFv were derived from the Nissim phage antibody library (generously provided by Prof G. Winter, MRC21). The library was panned against colorectal tumour cell lines, with negative panning against the human breast carcinoma cell line T47D.20 The scFv clone LAG3 was selected for use in this study because of its relatively high level of cell binding and efficient production of soluble scFv. A negative control scFv was also used, anti-NIP (3-iodo-4-hydroxy-5-nitrophenyl-acetate21).

LAG3 and anti-NIP scFv were cloned into the pCRT7/CT vector (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) pLyS (Invitrogen). This expression system introduces a 6xHistidine tag that facilitates efficient purification.

After scFv expression was verified in shake flask cultures, expression of scFv was scaled up by growth in 1 litre fermenters (Braun Biolab, Melsungen, Germany). An inoculum from the glycerol stocks of LAG3 or anti-NIP was added to 5 ml Luria broth (LB) media containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin, and grown overnight at 37°. The overnight culture was then subcultured in 75 ml LB media/100 µg/ml ampicillin and grown for 2 hr before being transferred into the fermenter. The inoculum was 1/10th of the total culture volume. pH was maintained at 7·0 (−0·1, +0·1) by automatic addition of 1 m HCl or 1 m NaOH. The temperature was maintained at 37° by heating against constant cooling. The culture was aerated with one volume air/one volume of culture/minute. The concentration of dissolved oxygen (DO2) was measured by polarographic oxygen electrode and maintained above 70% at saturation; if necessary by increasing the air flow. Samples were collected every hour and cell growth was measured by absorbance readings at OD600 nm. After 2 hr, the culture reached exponential growth and was induced with 1 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG, final concentration). The culture was harvested after 7 hr by centrifugation at 2500 g for 20 min

The cell pellets were lysed using an appropriate volume of BugBuster (Novagen, Nottingham, UK) and the crude homogenate was centrifuged at 11 000 g for 10 min to obtain a supernatant containing scFv. The purification of the His-tagged scFv from this supernatant was performed by Cobalt resin chromatography (Sigma, Poole, UK) following the manufacturer's instructions. The eluted scFv was dialysed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), quantified by Bradford Assay and analysed by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE).

Cells

Colorectal cancer cell line, Caco-2 (human Caucasian colon adenocarcinoma) was purchased from the European Collection of Animal and Cell Cultures (ECACC, UK). Cells were grown at 37° in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine, 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated calf serum and 100 U/ml penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen).

Photosensitizers

5-(4-Isothiocyanatophenyl)-10,15,20-tri-(3,5-dihydroxyphenyl) porphyrin (PS1) and 5-(4-isothiocyanatophenyl)-10,15,20-tris-(4-N-methylpyridiniumyl) porphyrin trichloride (PS2) were synthesized as described by Sutton et al.19 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Structures of photosensitizers. 1, PS1 5-(4-isothiocyanatophenyl)-10,15,20-tri-(3,5-dihydroxyphenyl) porphyrin. 2, PS2 5-(4-isothiocyanatophenyl)-10,15,20-tris-(4-N-methylpyridiniumyl) porphyrin trichloride.

Preparation of scFv : photosensitizer conjugates

Conjugation was carried out in 1 ml reactions containing 0·5 mg scFv in NaHCO3 buffer (0·5 m, pH 9·2) and a molar excess of PS (between 2·5 and 60 molar excess). The reaction was protected from light, and agitated gently at room temperature for 1 hr. The conjugates were then purified immediately on PD 10 desalting columns (Amersham, Buckingham, UK) to remove unbound porphyrin and finally eluted with PBS (pH 7·4). The conjugates were centrifuged at 13 000 g for 5 min to pellet any porphyrin : scFv aggregates. The number of moles of PS was calculated by UV-visible spectroscopy. The 420ε in PBS for PS1 and PS2 were 61 000 and 118 000 m−1 cm−1, respectively. All conjugates were stored, protected from light, at −20°.

Flow cytometry

Caco-2 cells were grown to confluence and detached from tissue culture flasks with 5 mm ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA) in PBS. The resulting cells were counted and 2·5 × 105 cells were added to polypropylene tubes. After washing with PBS/bovine serum albumin/azide (0·25% (w/v) BSA, 10 mm NaN3), 50 µl of scFv (10 µg/ml) was added to each tube and incubated for 1 hr at 4°. The excess antibody was removed by washing the cells with 1 ml of PBS/BSA/azide and centrifugation at 200 g for 3 min. Next, 50 µl of 10 µg/ml mouse anti-His tag antibody (ABD Serotec, Oxford, UK) was added to the cells for 1 hr at 4°. After further washing as above, cells were resuspended in 50 µl of 10 µg/ml rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; ABD Serotec) and incubated for 1 hr at 4° to detect the cell-bound scFv. The unbound antibody was again removed by washing the cells as above and the cell pellet was finally resuspended in 300 µl PBS/BSA/azide. Cells were analysed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Oxford, UK) using CellQuest software (Version 3).

In vitro cytotoxicity

Caco-2 cells were removed from culture flasks with 5 mm EDTA as described above and 1 × 105 cells were added to 5 ml polypropylene tubes. ScFv : porphyrin conjugates were diluted in serum free media, added to the cells and incubated at 37° for 15 min (Maximal scFv binding was achieved by 15 min; data not shown). Cells were then washed three times with media to remove unbound conjugate, resuspended in complete media and plated out in duplicate in 2× 96-well plates (2·5 × 104 cells/well). After incubation at 37° for 18 hr, one plate acted as the dark control (i.e. no irradiation) whilst the other was irradiated with 15 J/cm2 of cooled and filtered red light delivered by a Patterson light system (Phototherapeutics Ltd: Patterson Lamp BL1000A, bandpass 630 ± 15 nm filter). The plates were incubated at 37° overnight before a commercial MTS assay (Promega, Madison, WI) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The percentage of cell survival was calculated in proportion to the number of cells incubated without photosensitizer.

Annexin V–FITC staining

The annexin V–FITC versus propidium iodide kit (ABD Serotec) was used, according to manufacturer's instructions, to assess the mechanism of cell death induced by the scFv conjugates. Caco-2 cells (2 × 104) were incubated with a lethal dose25 (LD25)of conjugates for 15 min at 37°. Cells were washed three times in media and plated out in duplicate in a 96-well plate (1 × 104 cells/well). After incubation at 37° for 18 hr, the plate was irradiated with 15 J/cm2 red light and incubated for 15 min. Cells were then immediately removed from the respective wells with 0·05% (w/v) trypsin/0·53 mm EDTA and stained with Annexin V–FITC and propidium iodide. Cells were finally analysed by flow cytometry.

Results

Expression and purification of scFv

LAG3 and anti-NIP scFv were successfully expressed and purified as confirmed by SDS–PAGE gel electrophoresis and Western blotting giving a predominant band at approximately 30 000 MW as expected (data not shown). The total yield of protein expression was estimated (using the Bradford Assay) to be approximately 1·5 mg/l bacterial culture.

Preparation of immunoconjugates

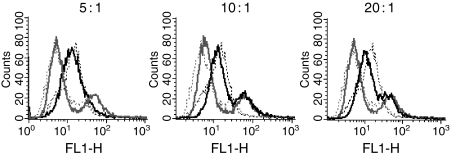

ScFv were initially conjugated using the Fluoro Tag FITC Conjugation kit (Sigma) to optimize scFv labelling conditions. The conjugation process involves coupling via the NCS group and, therefore provides an ideal model system for scFv conjugation to isothiocyanate-bearing derivatives. FITC was conjugated to LAG3 and anti-NIP scFv at molar ratios of 5, 10 and 20. Following conjugation, the retention of the binding specificity of the conjugates was tested by flow cytometry against the Caco-2 cell line (Fig. 2). The profiles of conjugated and unconjugated LAG3 scFv were very similar at a loading ratio of 5 : 1 indicating no effect on scFv binding specificity; however, at higher loading ratios (10 : 1, 20 : 1) binding of the conjugate is visibly reduced indicating that conjugation has caused some interference with scFv binding. It was also seen with the negative control anti-NIP conjugates that no non-specific binding to cells was caused after conjugation with FITC at any of the loading ratios.

Figure 2.

Conjugation of FITC to scFv at molar loading ratios of 5 : 1, 10 : 1 and 20 : 1 (FITC : scFv). Histograms show binding of LAG3 (black) and anti-NIP (grey) to cells before conjugation (dotted lines) and after conjugation (solid lines).

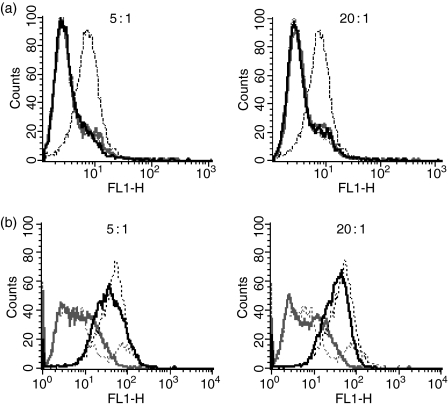

Conjugation of scFv to porphyrin (PS1 and PS2; Fig. 1) was then attempted using a comparable range of loading ratios (2·5, 5 and 20). Conjugation was successfully achieved with both photosensitizers, and labelling ratios (moles of porphyrin per mole of scFv) were determined. First, the molar concentrations of PS and mAb were calculated thus: [photosensitizer] = A420nm/ε; and [mAb] = (A280nm/1·3)/25 000 (relative molecular mass of scFv). The loading ratio was then determined by division of the moles of PS by the moles of scFv. These were between 4 and 20 molecules of porphyrin per scFv for PS1 and between 0·67 and 1·2 molecules of porphyrin per scFv for PS2. Flow cytometric analysis after conjugation showed that all scFv:PS1 conjugates had lost Caco-2 reactivity (Fig. 3a) whereas all the scFv : PS2 conjugates retained significant cell binding ability (Fig. 3b). However, binding was reduced slightly at the highest loading ratio (20 : 1) comparable to that seen with the scFv : FITC conjugates. All further experiments were carried out using scFv : PS2 conjugates prepared with the optimized loading ratio of 5 : 1.

Figure 3.

(a) Conjugation of PS1 to scFv at molar loading ratios of 5 : 1 and 20 : 1 (PS1 : scFv). Histograms show binding of LAG3 (black) and anti-NIP (grey) to cells before conjugation (dotted lines) and after conjugation (solid lines). After conjugation of LAG3 at both loading ratios, binding is destroyed. (b) Conjugation of PS2 to scFv at molar loading ratios of 5 : 1 and 20 : 1 (PS2 : scFv). Histograms show binding of LAG3 (black) and anti-NIP (grey) to cells before conjugation (dotted lines) and after conjugation (solid lines).

In vitro cytotoxicity

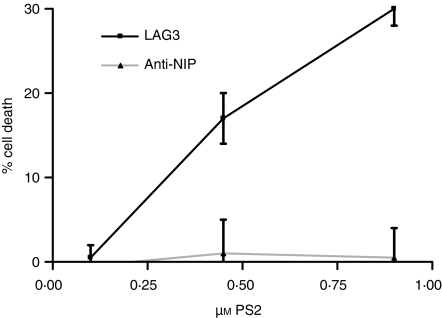

The cytotoxicity of the scFv : PS2 conjugates was assessed by incubation of varying concentrations of conjugate followed by irradiation and MTs assay to assess cell proliferation. It was found that, at a PS2 concentration of 0·85 µm, LAG3 conjugates caused 30% inhibition of cell growth whilst the anti-NIP conjugate had no effect on cell growth at the same concentration (Fig. 4). Both treatment with PS2 conjugates without irradiation and treatment with scFv alone had no effect on cell growth (data not shown). Previous experiments using scFv conjugates without the final centrifugation clean-up showed >90% lysis of the Caco-2 cells in the low micromolar range, however, the anti-NIP conjugates purified in this way also gave significant killing (data not shown).

Figure 4.

In vitro cytotoxicity of scFv : PS2 conjugates. LAG3 (black line) and anti-NIP (grey line) treated cells were irradiated with 15 J/cm2 red light and the percentage cell death assessed by MTS assay.

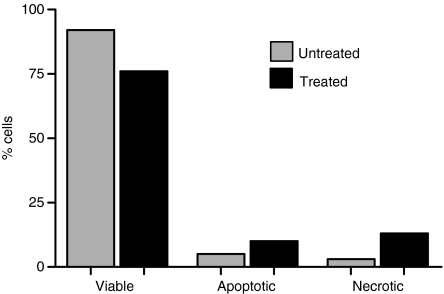

In order to verify that cells are killed, rather than being growth inhibited by treatment with LAG3 : PS2 conjugates, and to investigate the mode of cell death, Caco-2 cells were analysed by dual staining with annexin V–FITC and propidium iodide 1 hr after PDT treatment and irradiation. It was shown that after treatment with a LD25 of LAG3 : PS2, as previously determined by MTS assay, 76% cells were viable (compared with 92% in untreated), 10% cells were apoptotic (compared with 5% in untreated) and 13% cells were necrotic (compared with 3% in untreated; Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Mechanism of cell death after PDT with scFv : PS2. The proportion of viable, necrotic (propidium iodide stained) and apoptotic cells (Annexin V stained) in the treated (black) and untreated (grey) cell populations after treatment with scFv : PS2 at LD25. Representative of three individual experiments.

Discussion

This study is the first to demonstrate the conjugation of photosensitizers to scFv via an isothiocyanate group for use in targeted photoimmunotherapy. The procedure is simple, quick, does not form byproducts, and the resulting photosensitizers cause tumour cell lysis in the presence of red light (630 ± 15 nm). Previous groups have demonstrated the conjugation of PS to mAb;5 however, attention has become focused on antibody fragments in recent years (particularly Fab and scFv) as superior tumour targeting vehicles because of their improved tumour penetration and rapid blood clearance.11 The only previous report of targeted delivery of a photosensitizer by a phage-derived antibody fragment was by Neri and colleagues22 who used an anti-fibrinogen antibody (L19) to successfully target endothelial cells without damaging surrounding tissue in the neovasculature of an ocular model with tin(IV) chlorin e6 photosensitizer. This conjugate was prepared by cardodiimide-type coupling; a more complex conjugation strategy than using the NCS group that results in a variety of unwanted byproducts.

The preparation of any immunoconjugate needs to ensure the binding specificity of the antibody is not compromised; therefore conjugation to scFv is more challenging than to mAb as there is more capacity for blocking of the antibody-binding site on the smaller scFv molecule. Here we have used a scFv specific for colorectal cancer cell lines (LAG3) along with a non-binding scFv control (anti-NIP) as a model system.20

The PS used for conjugation are recently described isothiocyanato porphyrins.19 These molecules enable conjugation under mild conditions by the interaction of the porphyrin isothiocyanate group specifically with amine groups contained in lysine residues. These porphyrins offer benefits over other photosensitizer-conjugation strategies as they do not produce reactive intermediates or by-products. It has been previously demonstrated by our group that these compounds can be successfully conjugated to mAb without compromising binding specificity.10

LAG3 and anti-NIP were first conjugated to FITC to optimize conjugation conditions. This conjugation follows the same procedure as for porphyrin conjugation, producing a labelled product that could be easily detected. It was found that scFv could be successfully labelled with FITC at a molar loading ratio of 5 : 1 (FITC : scFv); at this loading ratio no difference in the binding of the scFv after conjugation, and no non-specific binding of the negative control scFv was observed. However, at higher molar loading ratios (10 : 1, 20 : 1) the level of binding of scFv to cell lines was reduced.

The same range of loading ratios was used for conjugation of porphyrin isothiocyanates (PS1 and PS2). It was found that a loading ratio of 5 : 1 (PS : scFv) was optimal for conjugation of PS2. Conjugation at higher loading ratios either reduced (20 : 1) or completely destroyed binding (40 : 1; data not shown). Previously, it has been shown that the optimal loading ratio of PS2 onto monoclonal IgG was 20 : 1,10 showing that, unsurprisingly, scFv were more susceptible to interference of antigen binding than their monoclonal counterparts.

Although successful conjugation of scFv to PS2 was demonstrated, conjugation to PS1 was unsuccessful at all loading ratios. This is likely to be the result of the nature of the photosensitizer, as PS1 is a more hydrophobic molecule than PS2. During conjugation with PS1 a high level of non-covalent binding is observed, this excess porphyrin causes blocking of the scFv antigen binding site and therefore the resulting conjugates are not useful. This highlights the need for hydrophilicity in photosensitizers coupled to scFv or IgG.

PS2 : scFv conjugates were found to have a selective cytotoxic effect on cell lines. Large-scale preparations of scFv (20 : l) required, to test concentrations in excess of 1 µm, are currently being undertaken. Analysis of the killing mechanism(s), after administration of low doses of PS2 : scFv immnoconjugate, by dual staining of treated cells with Annexin V–FITC and propidium iodide revealed that apoptosis was being induced. This is a major advantage of using PDT, as promotion of apoptotic rather than necrotic death, will cause less scarring following tumour destruction.23 This is particularly important in tumours such as those of the larynx where scarring following conventional therapies can itself severely impair speech and hence quality of life.24

This method of conjugating porphyrin isothiocyanates is applicable to any antibody fragments that contain lysine residues, and we believe that this work shows the potential of scFv : porphyrin conjugates as an antitumour photodynamic strategy worth pursuing.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- IPTG

isopropyl-βd-thiogalactoside

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MTS

[3-(4,5-dimethythiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2(4sulphophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt

- PDT

photodynamic therapy

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PS

photosensitizer

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- scFv

single-chain Fv

References

- 1.Sharman WM, Allen CM, Van Lier JE. Photodynamic therapeutics: basic principles and clinical applications. Drug Discov Today. 1999;4:507–17. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(99)01412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle RW, Dolphin D. Structure and biodistribution relationships of photodynamic sensitizers. Photochem Photobiol. 1996;64:469–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb03093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown SB, Brown EA, Walker I. The present and future role of photodynamic therapy in cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:497–508. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konan YN, Gurny R, Allemann E. State of the art in the delivery of photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. J Photochem Photobiol B-Biol. 2002;66:89–106. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Dongen GAMS. Photosensitiser-antibody conjugates for detection and therapy of cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:31–52. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mew D, Wat CK, Towers GHN, Levy JG. Photoimmunotherapy: treatment of animal tumours with tumour-specific monoclonal antibody–hematoporhyrin conjugates. J Immunol. 1983;130:1473–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oseroff AR, Ara G, Ohuoha D, Aprille J, Bommer JC, Yarmush ML, Foley J, Cincotta L. Strategies for selective cancer photochemotherapy: antibody targeted and selective carcinoma cell photolysis. Photochem Photobiol. 1987;46:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1987.tb04740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vrouenraets MB, Visser GWM, Steward FA, Stigter M, Oppelaar H, Postmus PE, Snow GB, Van Dongen GAMS. Development of meta-tetraxydroxyphenylchlorin–monoclonal antibody conjugates for photoimmunotherapy. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1505–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carcenac M, Larroque C, Langlois R, van Lier JE, Artus JC, Pelegrin A. Preparation, phototoxicity and biodistribution studies of anti-carcinoembryonic antigen monoclonal antibody-phthalocyanine. Photochem Photobiol. 1999;70:930–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson R, Carcenac M, Smith KA, Madden L, Clarke OJ, Pelegrin A, Greenman J, Boyle RW. The development and characterisation of porphyrin isothiocyanate-monoclonal antibody conjugates for photoimmunotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1442–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trail PA, King HD, Dubowchik GM. Monoclonal antibody drug immunoconjugates for targeted treatment of cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003;52:328–37. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0352-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith KA, Nelson PN, Warren P, Astley SJ, Murray PG, Greenman J. Demystified. recombinant antibodies. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:912–7. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.014407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russeva MG, Adams GP. Radioimmunotherapy with engineered antibodies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:217–31. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradbury ARM, Marks JD. Antibodies from phage antibody libraries. J Immunol Meth. 2004;290:29–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chester K, Pedley B, Tolner B, et al. Engineering antibodies for clinical applications in cancer. Tumour Biol. 2004;25:91–8. doi: 10.1159/000077727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goff BA, Bamberg M, Hasan T. Photoimmunotherapy of human ovarian carcinoma cells ex vivo. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4762–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamblin MR, Miller JL, Hasan T. Effect of charge on the interaction of site-specific photoimmunoconjugates with human ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5205–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarke OJ, Boyle RW. Isothiocyanatoporphyrins, useful intermediates for the conjugation of porphyrins with biomolecules and solid supports. Chem Commun. 1999;21:2231. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutton JM, Clarke OJ, Fernandez N, Boyle RW. Porphyrin, chlorin, and bacteriochlorin isothiocyanates. useful reagents for the synthesis of photoactive bioconjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 2002;13:249–63. doi: 10.1021/bc015547x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Topping K, Hough VC, Monson JRT, Greenman J. Isolation of human colorectal tumour reactive antibodies using phage display technology. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:187–95. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nissim A, Hoogenboom HR, Tomlison IM, Flynn G, Midgley C, Lane D, Winter G. Antibody fragments from a single pot phage display library as immunochemical reagents. EMBO J. 1994;13:692–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birchler M, Viti F, Zardi L, Spiess B, Neri D. Selective targeting and photocoagulation of ocular angiogenesis mediated by a phage-derived human antibody fragment. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:984–8. doi: 10.1038/13679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oleinick NL, Morris RL, Belichenko T. The role of apoptosis in response to photodynamic therapy. What, where, why, and how. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2002;1:1–21. doi: 10.1039/b108586g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biel MA. Photodynamic therapy in head and neck cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2002;4:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s11912-002-0053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]