Abstract

Langerhans cells (LCs) represent a special subset of immature dendritic cells (DCs) that reside in epithelial tissues at the environmental interfaces. Although dynamic interactions of mature DCs with T cells have been visualized in lymph nodes, the cellular behaviours linked with the surveillance of tissues for pathogenic signals, an important function of immature DCs, remain unknown. To visualize LCs in situ, bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 mice expressing the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) transgene were transplanted into syngeneic wild-type recipients. Motile activities of EGFP+ corneal LCs in intact organ cultures were then recorded by time lapse two-photon microscopy. At baseline, corneal LCs exhibited a unique motion, termed dendrite surveillance extension and retraction cycling habitude (dSEARCH), characterized by rhythmic extension and retraction of their dendritic processes through intercellular spaces between epithelial cells. Upon pinpoint injury produced by infrared laser, LCs showed augmented dSEARCH and amoeba-like lateral movement. Interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist completely abrogated both injury-associated changes, suggesting roles for IL-1. In the absence of injury, exogenous IL-1 caused a transient increase in dSEARCH without provoking lateral migration, whereas tumour necrosis factor-α induced both changes. Our results demonstrate rapid cytokine-mediated behavioural responses by LCs to local tissue injury, providing new insights into the biology of LCs.

Keywords: dendritic cells, cytokines, tissue injury, microscopy

Introduction

Epithelial tissues at the environmental interfaces are protected against external insults by networks of special subsets of immature dendritic cells (DCs), known as Langerhans cells (LCs), which are characterized morphologically by long dendritic processes extended between adjacent epithelial cells and phenotypically by the expression of major histocompatibility class II (MHC II) molecules, CD11c (DC-associated integrin-αx chain), and langerin (LC associated C-type lectin).1–5 LCs are thought to play at least two critical roles in the peripheral tissues, i.e. to capture innocuous and pathogenic antigens and to survey tissues for microbial invasion or the emergence of proinflammatory stimuli.6–8

Upon sensing such ‘danger’ signals, LCs differentiate into fully mature DCs and migrate to draining lymph nodes to accomplish a new task of presenting antigens to T cells.6–8 Recent advances in imaging technologies have enabled investigators to directly visualize the dynamic interactions of antigen loaded DCs with CD4 and CD8 T cells in vitro as well as in vivo in intact lymph nodes.9–16 Others have discerned the impact of DC maturational states on the stability of DC–T-cell contacts and even revealed how DCs can present soluble antigens acquired within the lymph node.17,18 These studies have greatly improved our understanding of the behavioural mechanisms by which mature DCs present antigens to T cells in the lymph nodes, an important function of DCs.19–24

By contrast, only limited information has been available with respect to the behaviours of immature DCs in the peripheral tissues. One critical function of DCs is to survey the tissues for the emergence of ‘danger’ signals, those resulting from microbial invasion or tissue injury.6–8 LCs in the epithelial tissues express a multitude of molecules, such as cytokine receptors, Toll-like receptors, and purinergic type 2 receptors, that make them particularly well suited to this task.1,3,6–8,25,26 Therefore, we sought to examine the behaviours of LCs upon sensing danger signals in situ. Recently, we reported the dynamic behaviours of epidermal LCs as observed both ex vivo and in vivo by confocal microscopy.27 In response to various pathological stimuli, epidermal LCs exhibited increased lateral migration within the tissue and augmented a peculiar behaviour characterized by rhythmic extension and retraction of their dendritic processes. This behaviour, which we have termed the dendrite surveillance extension and retraction cycling habitude (dSEARCH), was observed in LCs at least 16 hr after tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) injection or skin organ culture or 30 hr after application of a reactive hapten.

Given this information, we were curious as to whether LCs in different tissues would display similar motility and as to how soon after pathogenic stimulus LCs are able to alter their behaviours. The superficial layer of the cornea, though an epithelial tissue like the epidermis, is quite different from the epidermis in structure and biology. Indeed, the immunological environment of the cornea is unlike the skin in that the cornea displays immune privilege; immune reactions are decreased or suppressed in the cornea as evidenced by the relatively rare occurrence of graft rejection after corneal transplantation and by the generation of immune tolerance to antigens introduced into the anterior chamber.28–32 Moreover, constitutive MHC II expression by LCs in the cornea is seen only in the most peripheral regions near the cornea–sclera border, and LC precursors in the central cornea express MHC II only after significant inflammatory stimuli.3,33,34 For these reasons, we believed that the study of corneal LC behavioural responses would greatly contribute to the overall understanding of LC immunobiology. Herein we report the dynamic responses of corneal LCs in intact organ culture to local thermal injury visualized by time-lapse two-photon laser scanning microscopy.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57BL/6 mice and transgenic mice expressing the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene under the control of the chicken β-actin promoter and cytomegalovirus enhancer on a C57BL/6 background35 were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), and breeding colonies were established at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Six−8-week-old wild-type mice received whole-body γ-radiation of 9·5 Gy, followed by intravenous (i.v.) injection of bone marrow cells harvested from enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)+/– mice (107 cells/animal). All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of Texas South-western Medical Center and carried out according to the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health.

Flow cytometric examination of leucocyte populations after bone marrow transplantation

In order to confirm the successful engraftment of EGFP+ haematopoietic stem cells and resulting reconstitution of the immune system, recipient mice were examined for EGFP expression in various tissues 10–12 weeks after bone marrow transplantation.36 Splenocytes suspensions were prepared by physically disrupting the spleen capsule and then passing the suspension through nylon mesh. Peripheral blood leucocyte suspensions were prepared by lysing the red blood cells from whole blood samples. Cell suspensions were then stained with R-phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAb) against CD45, CD3, B220, or CD11c (all from BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and examined by flow cytometry. Analysis of flow cytometry data was performed using Cell Quest (BD Biosciences Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA) and WinMDI (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA) software packages.

Immunofluorescent staining of corneal samples

The extent of reconstitution of immune cells and the differences in leucocyte populations in the cornea between normal and chimeric animals were examined by immunofluorescent staining. Whole mount corneal samples from at least three EGFP chimeric mice or untreated C57BL/6 mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then stained with unlabeled or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-, PE-, Cy5-, or allophycocyanin-labelled mAb against CD45, MHC II, CD11b, CD3, B220, or Gr1 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen), or F4/80 (Serotec, Raleigh, NC). In some experiments, AlexaFluor488-labeled anti-FITC or AlexaFluor546-labelled anti-rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibodies were used (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA). Samples were then examined under a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope using a Zeiss 10× Plan-NEOFLUAR objective (numerical aperture 0·30). Cells expressing individual markers were manually counted using MetaMorph (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA) and ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) software packages. In a different set of experiments, corneal epithelial sheets prepared from at least three EGFP chimeric mice by ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid treatment3 were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and then stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD11c or anti-MHC II mAb (BD Biosciences Pharmingen). Cells expressing EGFP, CD11c, and/or MHC II were counted under an Olympus BX60 fluorescence microscope with 10× or 20× Olympus UPlan Fl objectives (numerical aperture 0·30 or 0·50, respectively) using a Sensys digital camera system and MetaVue software (Molecular Devices).

To examine the spacial relationship of EGFP+ LCs to neighbouring epithelial cells, whole mount corneal samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, labelled with propidium iodide, and then imaged by a Leica TCS SP2 single-photon confocal microscope using a Leica 40× air objective and a 63× water immersion objective (numerical aperture 0·85 and 1·20, respectively).

Corneal organ cultures

For each experiment, a 2 mm wide anterior/posterior slice, centred about the cornea, was made through a freshly enucleated mouse eye using a specially fabricated double-bladed knife. The loop of tissue was then cut at the posterior pole and rid of the iris and lens to create a strip of tissue with the cornea in the centre. This strip was then secured to a tissue slice adapter (Bioptechs, Butler, PA) using a rubber O-ring, with the cornea centred over the aperture. The sample was placed into a Bioptechs Delta T4 dish at 37°, perfused using a microperfusion pump with phenol red-free complete RPMI-1640 aerated with 5% CO2 in air, and immediately imaged by multiphoton microscopy. In some experiments, mouse recombinant interleukin (IL)-1α or TNF-α (both from R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was added to the circulating medium. None of these reagents contained detectable amounts of endotoxin as tested by the QCL-1000 system (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ).

Time lapse imaging studies

Fluorescence data were acquired by a Leica SP2 multiphoton microscope equipped with nondescan detectors and a Mira 900F Ti:sapphire laser (Coherent, Santa Clara, CA). Two-photon excitation was achieved using a wavelength of 860 nm; images were acquired with an average x–y voxel size of 460 nm using 10× or 20× Leica Plan Apo objectives (numerical aperture 0·40 or 0·70, respectively). Three-dimensional image stacks (∼20 sequential axial planes separated by 1·5–5·0 µm) were recorded every 2 min. This z-axis range was chosen to include all dendritic processes that may be extended upward (up to 10–20 µm) from the cell bodies. At the beginning of experiments, the spatial relationship of EGFP+ LCs in the epithelium to collagen bundles in the stroma was determined by monitoring EGFP fluorescence concurrently with second harmonic generation, detected using a transmitted light detector with a 450 nm short-pass filter. Maximum intensity projections were generated with Leica Confocal Software (Leica Microsystems, Exton, PA) and MetaMorph software packages. Dendrite length was measured from the tip of the dendrite to the cell body with the Leica program. The ‘dSEARCH index’ for a given LC was calculated by adding the absolute values of the changes in dendrite lengths over the previous 6-min period (chosen arbitrarily). The x–y positions of the cell bodies were tracked using MetaMorph or ImageJ software.

Pinpoint thermal injury

After 60 min recording of baseline behaviours, pinpoint tissue injury was produced using the point-bleach function of the Leica software. Briefly, a single-pixel region of interest was chosen at the centre of an EGFP+ LC target. The infrared laser was then set for 1–2 min continuous exposure at maximum intensity, delivering at least 23 J of energy to an area of ∼0·25 µm2. The same field was then imaged every 2 min for an additional 3 hr. In some experiments, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra, R & D Systems) was added to the media (200 ng/ml) 60 min before injury.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance of the differences observed before and after treatment was determined by paired Student's t-test. To analyse the periodicity of the dendrite surveillance extension and retraction cycling habitude (dSEARCH), data were subjected to Fourier analysis using MATLAB software (The Math Works, Natick, MA). Briefly, lengths of individual dendritic processes were normalized about zero, and a fast Fourier transform was then applied to the data set. Power spectra were created by multiplying the transforms by their conjugates and dividing by the number of data points. A weighted mean period was calculated for each cell by dividing the sum of (period × power) values by the sum of the power values.

Results

Visualization and quantification of corneal LCs in situ

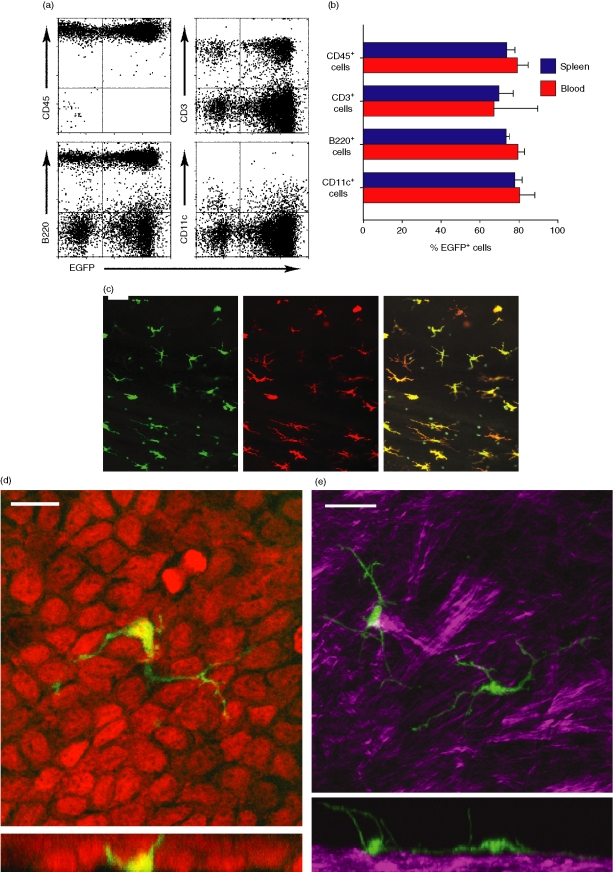

We chose to monitor LC behaviours in the cornea, considering its two major advantages for ex vivo imaging experiments: (1) fluorescence data could be gathered at high resolutions because of the optical transparency of the cornea, and (2) as an avascular organ, the cornea would maintain its physiologic state when perfused with aerated culture medium. To visualize LCs in the absence of tissue fixation or staining, we transplanted bone marrow cells from EGFP-transgenic mice into γ-irradiated wild-type C57BL/6 mice. After engraftment of the bone marrow transplant, the extent of reconstitution in the spleen and blood ranged from 67 to 84% for each of CD45+ leucocyte, CD3+ T-cell, B220+ B-cell, and CD11c+ DC populations (Fig. 1a, b). Reconstitution in the cornea was comparable to that observed in spleen and peripheral blood samples, with EGFP expression detected in a majority of CD45+ leucocytes (76%), CD3+ T cells (53%), F4/80+ macrophages (67%), and Gr1+ granulocytes (56%); very few, if any, B220+ B cells were found in the corneal samples.

Figure 1.

EGFP expression by leucocytes in chimeric animals. (a) γ-irradiated C57BL/6 mice received i.v. injection of bone marrow cells isolated from EGFP-transgenic mice. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from the recipient mice 10 weeks after transplantation were labelled with PE-conjugated mAb against the indicated leucocyte markers and examined for EGFP expression by FACS. Data shown are representative of independent measurements of six animals. (b) Spleen cell suspensions and peripheral blood samples from chimeric mice 10–12 weeks after transplantation were labelled with PE-conjugated mAb against the indicated leucocyte markers. Data shown are the means ± SD of the percentage EGFP+ cells as determined by FACS (spleen, n = 3; blood, n = 6). (c) Corneal epithelial sheets harvested 10 weeks after bone marrow transplantation were labelled with PE-conjugated anti-CD11c mAb and examined by conventional fluorescence microscopy. Panels show EGFP (green), CD11c (red), and overlay. Scale bar, 50 µm (d) Whole corneal samples harvested from EGFP chimeric mice were fixed, stained with PI, and then examined under single-photon confocal microscopy. Green fluorescence signals demarcate the three-dimensional structure of an intraepithelial EGFP+ LC extending long dendritic processes through intercellular spaces between epithelial cells, visualized by red fluorescence signals. Scale bar, 10 µm. Rotational images and z-axis stack can be viewed in Movies S1 and S2, respectively. (e) Corneal sample harvested from EGFP chimeric mice was fixed and then examined by two-photon laser scanning microscopy for the spatial relationship of EGFP+ LCs (green) to collagen bundles detected via second harmonic generation (magenta). Scale bar, 20 µm. Rotation images are shown in Movie S3.

Many EGFP+ cells were found within the corneal epithelium, primarily distributed in the peripheral regions (i.e. limbus). CD11c expression was detected in 82·2 ± 8·0% (mean ± SD, n = 215 cells) of these cells (Fig. 1c), while 91·9 ± 1·9% (n = 391) expressed MHC II. Surface densities of MHC II+ LCs in the peripheral cornea were comparable (P > 0·1) between the EGFP bone marrow chimeric mice (37·5 ± 16·3 cells/mm2, n = 3 corneas from separate animals) and control C57BL/6 mice (48·3 ± 11·4 cells/mm2). Likewise, no significant difference was observed between the two panels in terms of the morphology or distribution of MHC II+ LCs. Virtually all cells showing dendritic morphology (Fig. 1c–e; see Supplemental Movies S1 and S2) were located in the corneal limbal area of the epithelium and expressed CD11c (Fig. 1c) and MHC II (data not shown). Cells lacking the characteristic morphology, however, predominantly expressed F4/80 (69% of non-dendritic EGFP+ cells), CD11b (55%), CD3 (13%), and/or Gr1 (13%) and were located mainly within the stromal compartment. These results differ slightly from previously published data describing the density of LCs, the percentage of LCs expressing MHC II, and the absence of CD3+-cells in the corneas of BALB/c mice.34,37 These discrepancies likely reflect strain differences between BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice and/or differences in the staining and counting protocols used by the investigators.

Second harmonic generation during two-photon excitation38,39 allowed us to specifically locate the epithelium at the beginning of time-lapse experiments via the absence of collagen-associated signals, and thus for all further experiments we defined corneal LCs as intraepithelial EGFP+ cells showing the characteristic dendritic morphology (Fig. 1e and Movie S3). It should be noted, however, that a small fraction of LCs remained invisible, as EGFP expression was detected in 91·1 ± 2·0% of CD11c+ cells and 86·1 ± 8·2% of MHC II+ cells.

Corneal LCs interact with epithelial cells via dSEARCH

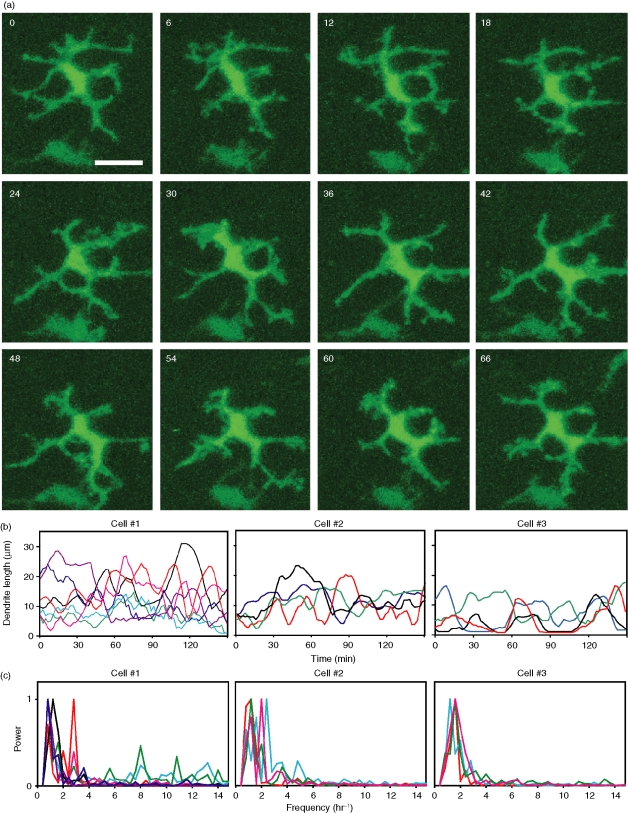

The use of laser scanning microscopy to image murine corneas in vivo is unfortunately impractical because of involuntary movements of the eye, even in anaesthetized animals. Therefore, to visualize the dynamic behaviours of LCs, corneal samples from chimeric mice were placed into organ culture. LCs in the limbus were then imaged by two-photon laser microscopy. While a small number of LCs displayed no overt motility, an overwhelming majority of LCs imaged in this way (92%) displayed an intriguing behaviour characterized by regular, repetitive extension and retraction of dendritic processes in random directions (Fig. 2a, b and Movies S4 and S5). This behaviour, termed dendrite surveillance extension and retraction cycling habitude (dSEARCH), occurred in a regular manner with a mean period of 32 ± 8 min (mean ± SD, n = 40), mean speed of extension of 1·5 ± 0·2 µm/min, and a mean speed of retraction of 2·0 ± 0·6 µm/min. To more quantitatively analyse the periodicity of dSEARCH, dendrite length data were subjected to Fourier analysis (Fig. 2c). Weighted mean periods of the cells in Fig. 2 were 40·0, 38·5, and 36·4 min, which are similar to the mean period estimated above.

Figure 2.

Corneal LCs display a unique behaviour termed dSEARCH. (a) dSEARCH by a representative LC is shown in static images. Maximal intensity projections of the x–y planes are shown at 6 min intervals. Scale bar, 20 µm. Time lapse images of dSEARCH by multiple LCs can be seen in Movies S4 and S5. (b) Lengths of multiple dendrites of three representative LCs were measured over time. Each line represents the lengths of a given dendrite measured every 2 min. Data shown have been smoothed using a moving average with a period of 4. (c) Periodicity of dSEARCH by the same representative cells was assessed by Fourier analysis. Each line represents the normalized power spectrum of a given dendritic process over the indicated frequencies per the imaging period (150 min). The colours of individual lines correspond to those in (b).

Although beyond the main scope of the present study, populations of cells were observed that migrated laterally within the tissue. The migration occurred primarily in the stromal compartment, and was exhibited by cells lacking the morphological characteristic of LCs. Smaller, fast-moving cells with a polygonal shape resembled the CD3+ or Gr1+ cells seen in fixed corneal preparations. Slower migration was seen in larger, amorphous cells that resembled F4/80+/CD11b+ macrophages in fixed samples. Thus it seems reasonable to speculate that the cornea is constantly patrolled by migratory T cells and/or granulocytes in addition to resident tissue macrophages. Given the extent to which the dendrites moved, however, it was surprising to note that little or no lateral movement was observed in LCs.

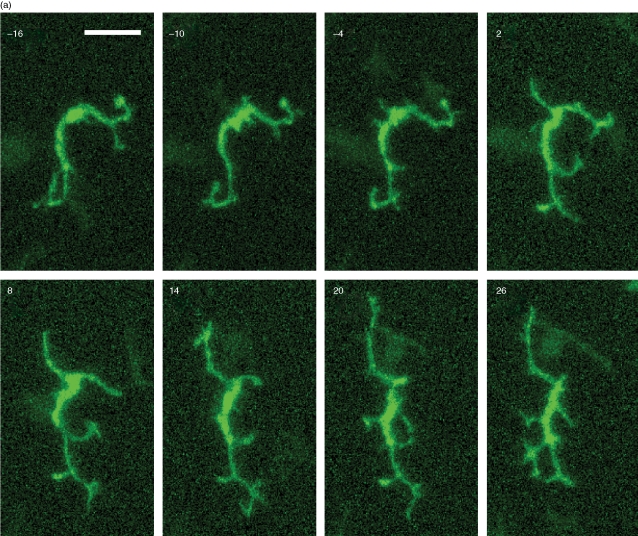

Behavioural responses of corneal LCs to local tissue injury

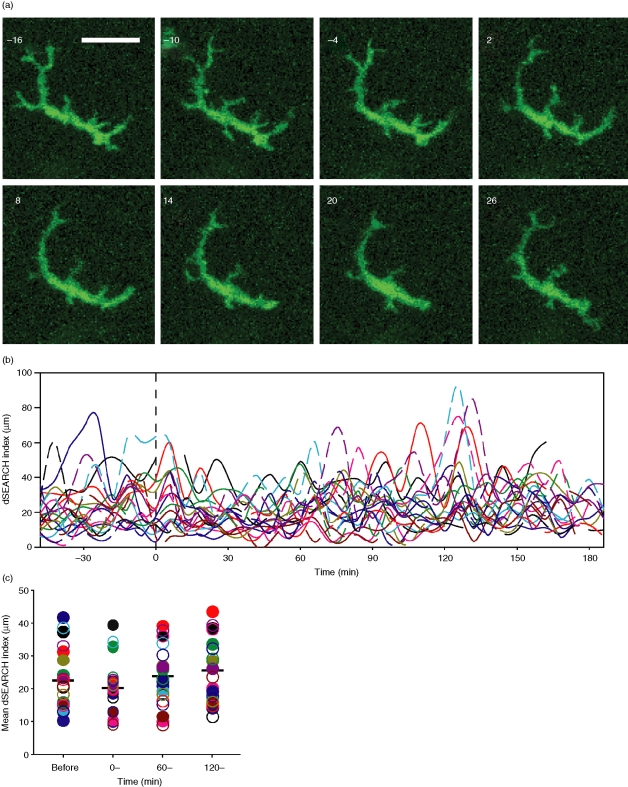

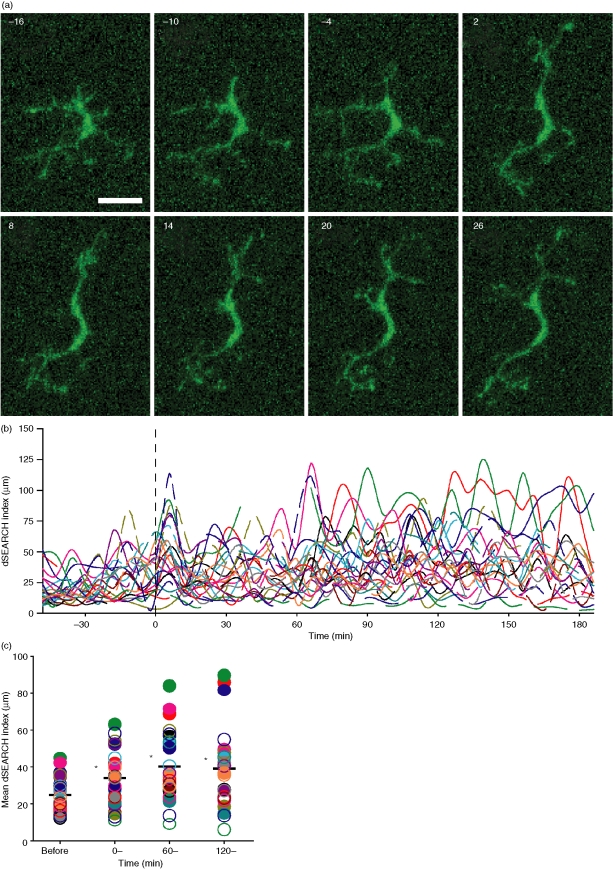

After identifying a baseline behaviour of corneal LCs, we sought to determine how they would respond to localized pathogenic insults. To this end, we produced pinpoint thermal injury to LC targets using the infrared laser of the two-photon microscope. We chose EGFP+ LCs as targets simply because it allowed us to judge energy delivery to the target via the disappearance of the EGFP signal. Almost immediately (within 2–10 min of injury), LCs in the proximity of the injury site (<100 µm) began to exhibit augmented dSEARCH (Fig. 3a and Movies S6–S9). The overall dSEARCH activity, assessed by measuring the dSEARCH index, was significantly (P < 0·01, n = 24) elevated in the early (0–60 min), middle (60–120 min), and late (120–180 min) phases after injury (Fig. 3b–d).

Figure 3.

Pinpoint thermal injury triggers augmented dSEARCH in nearby LCs. (a) After 60 min recording at baseline, pinpoint injury was produced by infrared laser at time 0. Panels show changes in dSEARCH of a representative LC adjacent to the injury site. Images are maximal intensity projections of the x–y planes at 6 min intervals. Scale bar, 20 µm. See Movies S6–S9 for dynamic behavioural responses to tissue injury. (b) dSEARCH index values for 24 LCs from eight independent experiments are shown over time. Each line represents the dSEARCH index values of a single LC. (c) Mean dSEARCH index values were calculated for each LC before injury (before, −60–0 min) and during the early (0–, 0–60 min), middle (60–, 60–120 min), and late (120–, 120–180 min) phases after injury. Filled and open circles of a given colour correspond to the solid and broken lines, respectively, in (b). Mean values are shown with bars, and statistically significant differences (P < 0·01) compared with baseline (before) are indicated with asterisks.

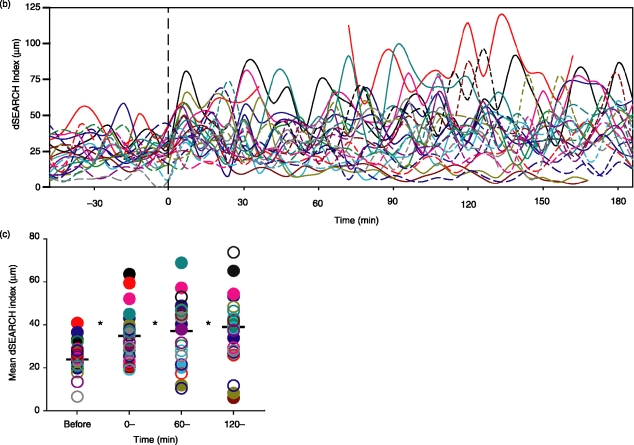

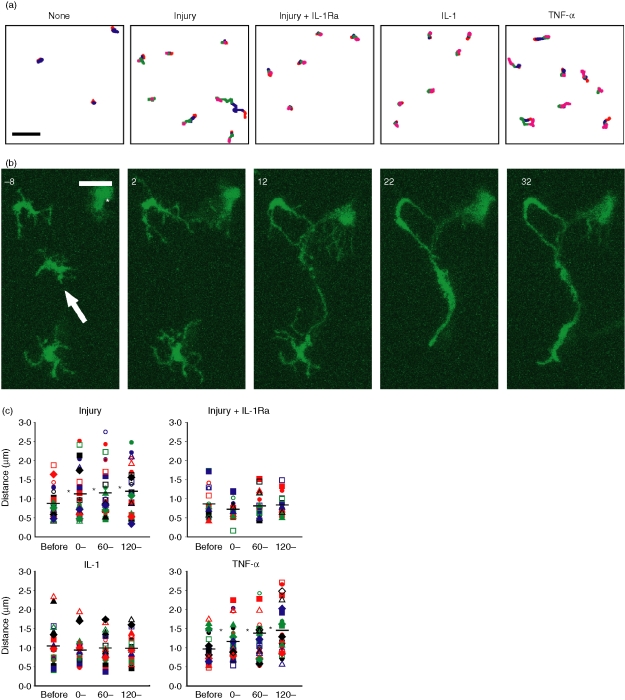

Local thermal injury also provoked lateral movement of nearby LCs (Figs 4a, b and Movies S6–S9). To quantitatively assess the migratory activity, we calculated the mean travelled distance of individual LCs between image frames (2 min interval). Thermal injury was found to increase this parameter significantly (P < 0·05, n = 28) in all three postinjury phases (Fig. 4c). Although LCs occasionally moved toward the site of injury, as in Fig. 4(b), migration primarily occurred without an apparent directional bias.

Figure 4.

Lateral migration of LCs. (a) Positions of individual LCs were tracked over time in corneal samples without treatment (None), with injury at time 0 (Injury), with injury at time 0 in the presence of 200 ng/ml IL-1Ra added at time −60 (Injury + IL-1Ra), with 5 pg/ml IL-1α added at time 0 (IL-1), or with 50 pg/ml TNF-α added at time 0 (TNF). Locations of the cell bodies during different phases are shown in red (−60–0 min), blue (0–60 min), green (60–120 min), and pink (120–180 min). (b) Lateral migration of two LCs was induced by injury to an adjacent LC target (indicated with an arrow) at time 0. A large cell in the stroma is indicated with an asterisk. Images are maximum intensity projections of the x–y planes at 10 min intervals. Scale bar, 20 µm. For the full image sequence, see supplemental Movie S9. (c) The mean travelled distance was measured for each LC before treatment and after thermal injury (n = 28), injury in the presence of IL-1Ra (n = 20), addition of IL-1α (n = 24), or addition of TNF-α (n = 29). Mean values among all LCs are shown with bars, and statistically significant (P < 0·05) differences compared to baseline (before) are indicated with asterisks.

Role of IL-1 in injury-induced behavioural changes

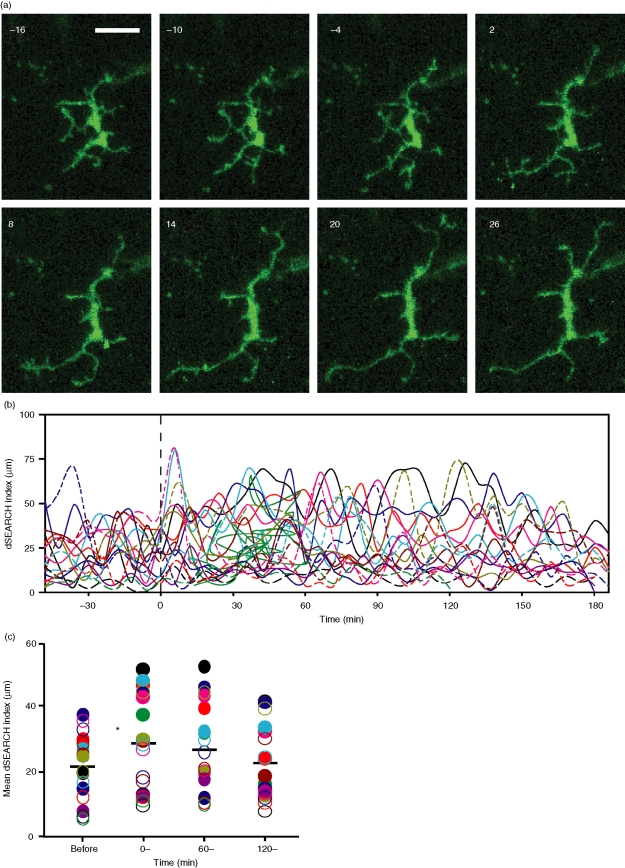

Because corneal epithelial cells and LCs are known to release IL-1 in response to various pathological stimuli, including tissue injury3,40–42 and rapid and profound IL-1 release occurs after thermal injury43 we chose to examine the role of IL-1 in corneal LC responses to injury. We therefore added IL-1Ra to the perfusion media and monitored the corneal samples for 60 min before injury. IL-1Ra treatment did not appreciably affect the baseline dSEARCH of the LCs, as the dSEARCH index values before injury in the presence of IL-1Ra (Fig. 5) were comparable (P > 0·1) to those in its absence (Fig. 3). Strikingly, IL-1Ra completely abrogated (P > 0·1, n = 20) the increase in dSEARCH index after pinpoint thermal injury (Fig. 5c, d and Movies S10 and S11). Also, no apparent lateral movement was seen in the presence of IL-1Ra, and the mean travelled distance values were not significantly elevated after injury (Fig. 4a, c). These results imply that rapid release of IL-1 is required for both forms of LC behavioural responses to local thermal injury.

Figure 5.

IL-1Ra prevents injury-induced amplification of dSEARCH. (a) IL-1Ra (200 ng/ml) was added to the medium at −60 min, and pinpoint thermal injury was produced at time 0. The images show maximum intensity projections of a representative LC adjacent to the injury site at 6 min intervals. Scale bar, 20 µm. See Supplemental Movies S10–S11 for dynamic behavioural responses. (b) dSEARCH index values were calculated for 20 LCs in six independent experiments. Each line represents the dSEARCH index for a single LC over time. (c) Mean dSEARCH index values were calculated for each LC before injury (before, −60–0 min) and during the early (0–, 0–60 min), middle (60–, 60–120 min), and late (120–, 120–180 min) phases after injury, all while in the continuous presence of IL-1Ra. Filled and open circles of a given colour correspond to the solid and broken lines, respectively, in (b). Mean values are shown with bars, and no statistically significant differences compared with baseline (before) were noted in any postinjury phase (P > 0·2).

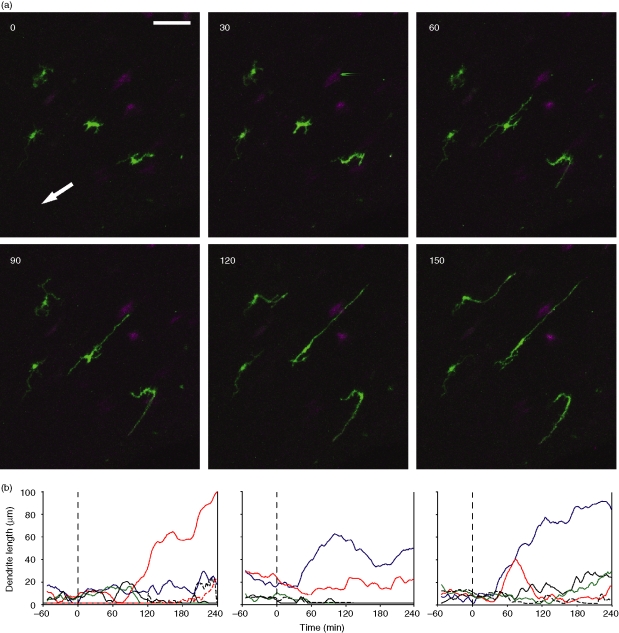

The addition of IL-1α (5 pg/ml) to the circulating medium augmented dSEARCH in the absence of injury (Fig. 6a, and Movies S12, S13), but the increase was transient, as the dSEARCH index was significantly elevated (P < 0·05, n = 18) only in the early phase after IL-1α addition (Fig. 6b–d). IL-1α failed to cause noticeable lateral movement, and the mean travelled distance values remained unchanged (P > 0·1, n = 24) after treatment (Fig. 4a, c). After exposure to IL-1α at a higher concentration (100 pg/ml), LCs began to progressively lengthen their dendrites (some eventually exceeding 100 µm), yet never showed dramatic lateral movement (Fig. 7 and Movie S14). Thus, IL-1 most likely acts as one, but not the only, factor mediating injury-induced LC behavioural changes.

Figure 6.

Impact of exogenous IL-1 on dSEARCH. (a) Following 60 min recording of baseline behaviours, IL-1α was added to the medium at 5 pg/ml. Maximum intensity projections of a representative LC are shown at 6 min intervals. Scale bar, 20 µm. See Movies S12 and S13 for dynamic behavioural responses. (b) dSEARCH index values were calculated for 18 LCs in four independent experiments. Each line represents the dSEARCH index for a single LC over time. (c) Mean dSEARCH index values were calculated for each LC before the addition of IL-1α (before, −60–0 min) and during the early (0–, 0–60 min), middle (60–, 60–120 min), and late (120–, 120–180 min) phases of IL-1α treatment. Filled and open circles of a given colour correspond to the solid and broken lines, respectively, in (b). Mean values are shown with bars, and statistically significant differences (P < 0·05) compared with baseline (before) are indicated with asterisks.

Figure 7.

Dendrite hyper-elongation induced by IL-1 at a high concentration. (a) After 60 min recording of baseline behaviours, IL-1α 100 (pg/ml) was added to the circulating medium at time 0. Maximum intensity projections of the x–y planes are shown at 30 min intervals (starting from time 0). Several intraepithelial EGFP+ LCs show progressive elongation of their dendrites in two opposing directions (the direction of the central cornea is indicated with an arrow). EGFP signals in the stromal compartment are pseudo-coloured in magenta. Scale bar, 50 µm. See supplemental movie S14 for time-lapse images of the entire 300 min recording period. (b) Lengths of multiple dendrites of three representative EGFP+ LCs showing progressive dendrite elongation were measured at the indicated time points. Each line represents the length of a given dendrite measured every two minutes.

Effect of TNF-α on dynamic LC behaviours

TNF-α is also elaborated by both LCs and corneal epithelial cells upon injury.3,40,41 Moreover, TNF-α has been reported to mediate IL-1-dependent migration of corneal LCs44 and trigger IL-1 production by corneal epithelial cells.45 Thus, we examined the effect of TNF-α on LC behaviours. Addition of TNF-α to the circulating medium (50 pg/ml) appeared to augment dSEARCH (Fig. 8a and Movies S15 and S16). In fact, LCs showed a significant (P < 0·01, n = 26) increase in dSEARCH index in all phases of TNF-α treatment (Fig. 8b–c). Furthermore, LC lateral movement became detectable after TNF-α treatment, with a significant (P < 0·05, n = 29) increase in mean travelled distance in all phases after treatment (Fig. 4a, c). These observations suggest the potential of TNF-α to induce sustained augmentation of both dSEARCH and lateral migration of corneal LCs.

Figure 8.

Impact of exogenous TNF-α on dSEARCH. (a) Following 60 min recording of baseline behaviours, TNF-α was added to the medium at 50 pg/ml. Maximum intensity projections of a representative LC are shown at 6 min intervals. Scale bar, 20 µm. See Movies S15 and S16 for dynamic behavioural responses. (b) dSEARCH index values were calculated for 26 LCs in four independent experiments. Each line represents the dSEARCH index for a single LC over time. (c) Mean dSEARCH index values were calculated for each LC before the addition of TNF-α (before, −60–0 min) and during the early (0–, 0–60 min), middle (60–, 60–120 min), and late (120–, 120–180 min) phases of TNF-α treatment. Filled and open circles of a given colour correspond to the solid and broken lines, respectively, in (b). Mean values are shown with bars, and statistically significant differences (P < 0·01) compared with baseline (before) are indicated with asterisks.

Discussion

Here we report an intriguing behaviour of immature LCs in peripheral epithelial tissues. This behaviour, termed dSEARCH, is characterized by repetitive extension and retraction of dendritic processes. Dynamic movement of dendrites has been recently demonstrated with lymph node-resident DCs;16,17 by projecting and waving their pseudopods, those DCs established dynamic physical contacts with T cells in lymph-nodes. Although the immunological function of that motion remains to be determined, it has been postulated that lymph node-resident DCs may maximize the chance for developing physical contacts with antigen-reactive T cells by moving the pseudopods.16,17 dSEARCH resembled the probing motion except that the dendrites were extended and retracted through the same paths (i.e. intercellular spaces between adjacent epithelial cells) without any waving movement. It is tempting to speculate that LCs may maximize the efficacy of antigen sampling by constantly surveying the intercellular space via dSEARCH. Supporting this hypothesis are previous reports documenting the capture of bacteria by DC dendrites in vitro and in vivo.46,47 Further studies are clearly required to determine whether dSEARCH is indeed coupled with active internalization of antigens by LCs.

One may argue that the ‘baseline’ behaviours of corneal LCs observed in our organ culture system represent artificial phenomena caused by inflammatory signals associated with tissue processing and culturing. While this is an important issue that remains to be clarified in living animals, physiological relevance of the baseline behaviours is supported by the following observations. First, experimentally produced trauma (i.e. local thermal injury) and inflammatory cytokines (i.e. IL-1 and TNF-α) provoked the behaviour of corneal LCs in the organ cultures, suggesting that our tissue processing and culturing procedures did not produce danger signals causing the maximal activity of LCs. Second, although centripetal migration of corneal LCs has been induced by various inflammatory stimuli (see below), no apparent LC migration was observed during our imaging period (up to 4 hr) in the absence of exogenous stimuli. This implies that our procedures did not cause significant maturation or activation of corneal LCs. Finally, the continuous presence of IL-1Ra, which completely abrogated injury-induced amplification of dSEARCH, failed to affect the baseline behaviours before injury, excluding the possibility that the baseline behaviours may be attributable to IL-1 released as a consequence of ex vivo tissue manipulation.

Formal assessment of the physiological relevance of our ex vivo observations would require in vivo imaging of LCs in cornea or other epithelial tissues. Unfortunately, laser scanning microscopy of the cornea in live animals is technically not feasible because of involuntary eye movement. However, the behavioural responses of corneal LCs to pinpoint thermal injury parallel the responses of epidermal LCs to diffuse inflammatory stimuli, which we have reported previously.27 While direct comparison of these behaviours is not possible because of differences in the experimental systems, a general pattern of increased dSEARCH activity and lateral migration in response to inflammation or tissue damage can be appreciated. In addition to our work on LC behaviours in the epidermis of I-Aβ-EGFP knock-in mice, Kissenpfennig et al. recently visualized dynamic in vivo behaviours of epidermal LCs in the langerin-EGFP knock-in mice using intravital confocal microscopy. Strikingly, EGFP+ epidermal LCs exhibited a dSEARCH-like behaviour by projecting and retracting their dendrites in ear skin after diffuse mechanical injury produced by tape stripping.48 Not only do these observations support physiological significance of our ex vivo observations, they also support our conclusion that danger signals associated with tissue injury provoke marked reprogramming of in situ behaviours of LCs within epithelial tissues.

Our results also provide clues to the mechanisms by which tissue injury may alter LC behaviours. In the presence of IL-1Ra, thermal injury completely failed to amplify dSEARCH or migration, implying that IL-1 released by damaged LCs (and perhaps corneal epithelial cells above and below the targeted LCs) plays an essential role. Exogenous IL-1 triggered rapid and transient augmentation of dSEARCH without triggering cellular migration, whereas TNF-α induced both significantly and continuously. Because IL-1 and TNF-α mutually stimulate the production of each other45,49,50 our observations suggest direct and indirect contributions of the two prototypic inflammatory cytokines to injury-induced changes in LC behaviours. These findings may first appear to simply duplicate previous reports; both IL-1 and TNF-α have been shown to mediate the migration of limbal LCs to central cornea under pathological conditions3,44,51 and IL-1Ra has been used to block centripetal LC migration and the resulting pathogenic outcomes in several disease models.51–53 To the best of our knowledge, however, this is the first report demonstrating the extremely rapid kinetics by which inflammatory cytokines mediate augmentation of dendrite movement and migration of immune cells in situ. These effects occurred within minutes of tissue injury or cytokine addition, suggesting direct biochemical regulation of the cytokine signaling pathways and not regulation mediated through transcriptional reprogramming. This is supported by previous reports documenting interactions of Rho-family GTPases, proteins known to mediate cytoskeletal actin rearrangement, with IL-1 and TNF receptors in vitro in cultured cell lines.54,55

In summary, we have demonstrated that corneal LCs respond to localized tissue injury by exhibiting amplified dSEARCH and augmented lateral displacement of the cell bodies. Together with recent reports on behavioural responses of epidermal LCs to diffuse mechanical or chemical skin trauma27,48 our observations introduce a new concept that maturation of LCs after tissue injury is accompanied by rapid, cytokine-mediated reprogramming of their in situ motile activities.

Acknowledgments

We thank J.Y. Niederkorn, P.R. Bergstresser, and P. Mishra for critical suggestions and discussions and P. Adcock for secretarial assistance. This work was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1-AI46755, RO1-AR35068, RO1-AR43777, and RO1-AI43232; Takashima), an infrastructure grant from the National Institutes of Health (EY016664; Jester, Petroll, and Cavanagh) and by a National Research Service Award from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease (T32-AI005284; Ward).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- DC

dendritic cell

- dSEARCH

dendrite surveillance extension and retraction cycling habitude

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- IL

interleukin

- IL-1Ra

interleukin-1 receptor antagonist

- LC

Langerhans cell

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MHC II

major histocompatibility complex class II

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PE

R-phycoerythrin

- TNF-α

tumour necrosis factor α

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material is available for this article online:

Three-dimensional images of intraepithelial EGFP+ LC. A three-dimensional data set similar to that shown in Fig. 1(d) (without counter-staining with PI) was reconstructed along the x-z plane, followed by rotation around the z-axis (180°) and the x-axis (360°). Note that while some of the fine dendritic processes extend upward in the z-axis, the LC occupies a much greater area in the x-y plane.

Spatial relationship of intraepithelial EGFP+ LC to neighboring epithelial cells. The data set shown in Fig. 1(d) was processed to display 46 sequential x-y images separated by 0·5 μm steps and spanning a z-depth of 24 μm. The series begins superficially in the epithelium and proceeds towards the stroma.

Three-dimensional images demonstrating the spacial relationship of EGFP+ LCs to collagen bundles. The data set shown in Fig. 1(e) was processed to show rotation around the z-axis (360°). Note the location of the EGFP+ LCs slightly above the collagen signals. This places the LCs within the epithelium, which lacks the abundant collagen bundles seen in the stroma.

Time-lapse images of baseline dSEARCH performed by multiple intraepithelial LCs. The data set shown in Fig. 2(a) was compiled to show dynamic movement of EGFP+ corneal LCs. Note that most of EGFP+ LCs with characteristic dendritic morphology exhibit the dSEARCH motion in the epithelial compartment, while rapid migration is observed with smaller EGFP+ cells possessing a polygonal shape primarily in the stromal compartment. The movie represents 18 independent imaging experiments; the dSEARCH index values for the LCs shown in this movie are within the normal variations measured for more than 170 LCs before any treatment (see Figs 3c, 5c, 6c, and 8c).

Time-lapse images of dSEARCH. The data set from an independent imaging experiment was compiled to show baseline dSEARCH by EGFP+ corneal LCs. The dSEARCH index values for the LCs shown in this movie are within the normal variations measured for more than 170 LCs before any treatment (see Figs 3c, 5c, 6c, and 8c).

Time-lapse images of injury-induced augmentation of dSEARCH. The four movies demonstrate injury-induced amplification of dSEARCH and lateral movement of EGFP+ LCs observed consistently in eight independent experiments. After 60 min recording of baseline behaviours, pinpoint thermal injury was produced at time 0 in an EGFP+ LC target indicated with an arrow. Behavioural responses of the LCs shown in the movies are within the normal variations in the dSEARCH index values (Fig. 3c) and the mean travelled distance values (Fig. 4c) measured with more than 20 LCs before and after thermal injury. Note the increased activity of the dendrites and the propensity for lateral movement within the epithelium after injury. In one imaging experiment, a large stromal EGFP+ cell with an amorphous cell shape (indicated with an asterisk) exhibited an unusual response characterized by rapid migration toward the injury site, followed by casting fine mesh-like projections toward neighboring LCs (Movie S9).

Time-lapse images of the impact of IL-1Ra on injury-triggered changes in LC behaviours. Data sets shown in Fig. 5(a) (Movie S10) and from an independent experiment (Movie S11) were compiled to show dynamic behavioural responses of corneal LCs to local injury in the presence of IL-1Ra, which was added to the circulating media at time −60 min to achieve a final concentration of 200 ng/ml. After recording of baseline behaviours, pinpoint thermal injury was produced at time 0 in an EGFP+ LC target (indicated with an arrow). Note how the activity of the dendrites does not change appreciably after injury and how EGFP+ LCs do not move significantly from their original positions. Behavioural responses of the LCs shown in the movies are within the normal variations in the dSEARCH index values (Fig. 5c) and the mean travelled distance values (Fig. 4c) measured with a total of 20 LCs before and after thermal injury in the presence of IL-1Ra.

Time-lapse images of IL-1-induced amplification of dSEARCH. Data sets shown in Fig. 6(a) (Movie S12) and from an independent experiment (Movie S13) were compiled to show dynamic behavioural responses of corneal LCs to IL-1. After 60 min recording of baseline behaviours, IL-1α was added to the circulating media at time 0 to achieve a final concentration of 5 pg/ml. Note an increase in the activity of the dendrites after addition of IL-1. Behavioural responses of the LCs shown in the movies are within the normal variations in the dSEARCH index values (Fig. 6c) and the mean travelled distance values (Fig. 4c) measured with more than 18 LCs after IL-1 treatment.

Time-lapse images of dendrite hyper-elongation triggered by IL-1 at high concentrations. The data set shown in Fig. 7(a) was compiled to show dynamic behavioural responses of corneal LCs to IL-1. After 60 min recording of baseline behaviours, recombinant IL-1α was added to the circulating media at time 0 to achieve a final concentration of 100 pg/ml. Note the profound elongation of the dendrites in the absence of significant lateral movement. The movie represents three independent imaging experiments showing IL-1-induced bidirectional dendrite hyper-elongation by corneal LCs.

Time-lapse images of TNF-α-induced changes in LC behaviours. Data sets shown in Fig. 8(a) (Movie S15) and from an independent experiment (Movie S16) were compiled to show dynamic behavioural responses of corneal LCs to TNF-α. After 60 min recording of baseline behaviours, TNF-α was added to the circulating media at time 0 to achieve a final concentration of 50 pg/ml. Note an increase in dendrite activity and lateral movement similar to the changes seen after tissue injury. Behavioural responses of the LCs shown in the movies are within the normal variations in the dSEARCH index values (Fig. 8c) and the mean travelled distance values (Fig. 4c) measured for more than 25 LCs before and after TNF-α treatment.

This material is available as part of the online article from http://www.blackwell-synergy.com.

References

- 1.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larrengina AT, Falo LD. Changing paradigms in cutaneous immunology: adapting with dendritic cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2004.23554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niederkorn JY, Peeler JS, Mellon J. Phagocytosis of particulate antigens by corneal epithelial cells stimulates interleukin-1 secretion and migration of Langerhans cells into the central cornea. Reg Immunol. 1989;2:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Panfilis G, Soligo D, Manara GC, Ferrari C, Torresani C. Adhesion molecules on the plasma membrane of epidermal cells. I. Human resting Langerhans cells express two members of the adherence-promoting CD11/CD18 family, namely, H-Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) and gp 150,95 (CD11c/CD18) J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93:60–9. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12277352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valladeau J, Duvert-Frances V, Pin JJ, et al. The monoclonal antibody DCGM4 recognizes Langerin, a protein specific of Langerhans cells, and is rapidly internalized from the cell surface. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2695–704. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199909)29:09<2695::AID-IMMU2695>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, et al. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rescigno M, Granucci F, Citterio S, Foti M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Coordinated events during bacteria-induced DC maturation. Immunol Today. 1999;20:200–3. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01427-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kupper TS, Fuhlbrigge RC. Immune surveillance in the skin: Mechanisms and clinical consequences. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:211–22. doi: 10.1038/nri1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoll S, Delon J, Brotz TM, Germain RN. Dynamic imaging of T cell–dendritic cell interactions in lymph nodes. Science. 2002;296:1873–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1071065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller MJ, Wei SH, Parker I, Cahalan MD. Two-photon imaging of lymphocyte motility and antigen response in intact lymph node. Science. 2002;296:1869–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1070051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bousso P, Robey E. Dynamics of CD8+ T cell priming by dendritic cells in intact lymph nodes. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:579–85. doi: 10.1038/ni928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benvenuti F, Hugues S, Walmsley M, et al. Requirement of Rac1 and Rac2 expression by mature dendritic cells for T cell priming. Science. 2004;305:1150–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1099159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, von Andrian UH. T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature. 2004;427:154–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller MJ, Hejazi AS, Wei SH, Cahalan MD, Parker I. T cell repertoire scanning is promoted by dynamic dendritic cell behavior and random T cell motility in the lymph node. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:998–1003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306407101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller MJ, Safrina O, Parker I, Cahalan MD. Imaging the single cell dynamics of CD4+ T cell activation by dendritic cells in lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2004;200:847–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindquist RL, Shakhar G, Dudziak D, Wardemann H, Eisenreich T, Dustin ML, Nussenzweig MC. Visualizing dendritic cell networks in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1243–50. doi: 10.1038/ni1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hugues S, Fetler L, Bonifaz L, Helft J, Amblard F, Amigorena S. Distinct T cell dynamics in lymph nodes during the induction of tolerance and immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1235–42. doi: 10.1038/ni1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itano AA, McSorley SJ, Reinhardt RL, Ehst BD, Ingulli E, Rudensky AY, Jenkins MK. Distinct dendritic cell populations sequentially present antigen to CD4 T cells and stimulate different aspects of cell-mediated immunity. Immunity. 2003;19:47–57. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Andrian UH. Immunology. T cell activation in six dimensions. Science. 2002;296:1815–7. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5574.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cahalan MD, Parker I, Wei SH, Miller MJ. Two-photon tissue imaging: seeing the immune system in a fresh light. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:872–80. doi: 10.1038/nri935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Catron DM, Itano AA, Pape KA, Mueller DL, Jenkins MK. Visualizing the first 50 hr of the primary immune response to a soluble antigen. Immunity. 2004;21:341–7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dustin ML. Stop and go traffic to tune T cell responses. Immunity. 2004;21:305–14. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sumen C, Mempel TR, Mazo IB, von Andrian UH. Intravital microscopy: visualizing immunity in context. Immunity. 2004;21:315–29. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang AY, Qi H, Germain RN. Illuminating the landscape of in vivo immunity: insights from dynamic in situ imaging of secondary lymphoid tissues. Immunity. 2004;21:331–9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaker MB, Tharp MD, Bergstresser PR. Rodent epidermal Langerhans cells demonstrate greater histochemical specificity for ADP than for ATP and AMP. J Invest Dermatol. 1984;82:496–500. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12261031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizumoto N, Kumamoto T, Robson SC, Sévigny J, Matsue H, Enjyoji K, Takashima A. CD39 is the dominant Langerhans cell-associated ecto-NTPDase: modulatory roles in inflammation and immune responsiveness. Nat Med. 2002;8:358–65. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishibu A, Ward BR, Jester JV, Ploegh HL, Boes M, Takashima A. Behavioral responses of epidermal Langerhans cells in situ to local pathological stimuli. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:787–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niederkorn JY. Immune privilege in the anterior chamber of the eye. Crit Rev Immunol. 2002;22:13–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niederkorn JY. Mechanisms of corneal graft rejection. Cornea. 2001;20:675–9. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niederkorn JY, Mellon J. Anterior chamber-associated immune deviation promotes corneal allograft survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2700–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dana MR, Qian Y, Hamrah P. Twenty-five-year panorama of corneal immunology: emerging concepts in the immunopathogenesis of microbial keratitis, peripheral ulcerative keratitis, and corneal transplant rejection. Cornea. 2000;19:625–43. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200009000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Streilein JW, Masli S, Takeuchi M, Kezuka T. The eye's view of antigen presentation. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:435–43. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamrah P, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Dana MR. The corneal stroma is endowed with a significant number of resident dendritic cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:581–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamrah P, Zhang Q, Liu Y, Dana MR. Novel characterization of MHC class II-negative population of resident corneal Langerhans cell-type dendritic cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:639–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K, Nakanishi T, Nishimune Y. ‘Green mice’ as a source of ubiquitous green cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:313–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumamoto T, Shalhevet D, Matsue H, Mummert ME, Ward BR, Jester JV, Takashima A. Hair follicles serve as local reservoirs of skin mast cell precursors. Blood. 2003;102:1654–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brissette-Storkus CS, Reynolds SM, Lepisto AJ, Hendricks RL. Identification of a novel macrophage population in the normal mouse corneal stroma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2264–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox G, Kable E, Jones A, Fraser I, Manconi F, Gorrell MD. 3-dimensional imaging of collagen using second harmonic generation. J Struct Biol. 2003;141:53–62. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00576-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campagnola PJ, Loew LM. Second-harmonic imaging microscopy for visualizing biomolecular arrays in cells, tissues and organisms. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1356–60. doi: 10.1038/nbt894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lausch RN, Chen SH, Tumpey TM, Su YH, Oakes JE. Early cytokine synthesis in the excised mouse cornea. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1996;16:35–40. doi: 10.1089/jir.1996.16.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sotozono C, He J, Matsumoto Y, Kita M, Imanishi J, Kinoshita S. Cytokine expression in the alkali-burned cornea. Curr Eye Res. 1997;16:670–6. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.16.7.670.5057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Enk AH, Katz SI. Early molecular events in the induction phase of contact sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1398–402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mester M, Carter EA, Tompkins RG, Gelfand JA, Dinarello CA, Burke JF, Clark BD. Thermal injury induces very early production of interleukin-1 alpha in the rat by mechanisms other than endotoxemia. Surgery. 1994;115:588–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dekaris I, Zhu SN, Dana MR. TNF-α regulates corneal Langerhans cell migration. J Immunol. 1999;162:4235–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohri M, Reinach PS, Kanayama A, Shimizu M, Moskovitz J, Hisatsune T, Miyamoto Y. Suppression of the TNFα-induced increase in IL-1α expression by hypochlorite in human corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3190–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bouis DA, Popova TG, Takashima A, Norgard MV. Dendritic cells phagocytose and are activated by treponema pallidum. Infect Immun. 2001;69:518–28. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.518-528.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rescigno M, Urbano M, Valzasina B, et al. Dendritic cells express tight junction proteins and penetrate gut epithelial monolayers to sample bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:361–7. doi: 10.1038/86373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kissenpfennig A, Henri S, Dubois B, et al. Dynamics and function of Langerhans cells in vivo dermal dendritic cells colonize lymph node areas distinct from slower migrating Langerhans cells. Immunity. 2005;22:643–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lisby S, Hauser C. Transcriptional regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in keratinocytes mediated by interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Exp Dermatol. 2002;11:592–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2002.110612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Werth VP, Zhang W. Wavelength-specific synergy between ultraviolet radiation and interleukin-1α in the regulation of matrix-related genes: mechanistic role for tumor necrosis factor-α. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:196–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dana MR, Dai R, Zhu S, Yamada J, Streilein JW. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist suppresses Langerhans cell activity and promotes ocular immune privilege. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:70–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dana MR, Yamada J, Streilein JW. Topical interleukin 1 receptor antagonist promotes corneal transplant survival. Transplantation. 1997;63:1501–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199705270-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Biswas PS, Banerjee K, Kim B, Rouse BT. Mice transgenic for IL-1 receptor antagonist protein are resistant to herpetic stromal keratitis: possible role for IL-1 in herpetic stromal keratitis pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2004;172:3736–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh R, Wang B, Shirvaikar A, et al. The IL-1 receptor and Rho directly associate to drive cell activation in inflammation. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1561–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI5754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Puls A, Eliopoulos AG, Nobes CD, Bridges T, Young LS, Hall A. Activation of the small GTPase Cdc42 by the inflammatory cytokines TNF alpha and IL-1, and by the Epstein–Barr virus transforming protein LMP1. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2983–92. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.17.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Three-dimensional images of intraepithelial EGFP+ LC. A three-dimensional data set similar to that shown in Fig. 1(d) (without counter-staining with PI) was reconstructed along the x-z plane, followed by rotation around the z-axis (180°) and the x-axis (360°). Note that while some of the fine dendritic processes extend upward in the z-axis, the LC occupies a much greater area in the x-y plane.

Spatial relationship of intraepithelial EGFP+ LC to neighboring epithelial cells. The data set shown in Fig. 1(d) was processed to display 46 sequential x-y images separated by 0·5 μm steps and spanning a z-depth of 24 μm. The series begins superficially in the epithelium and proceeds towards the stroma.

Three-dimensional images demonstrating the spacial relationship of EGFP+ LCs to collagen bundles. The data set shown in Fig. 1(e) was processed to show rotation around the z-axis (360°). Note the location of the EGFP+ LCs slightly above the collagen signals. This places the LCs within the epithelium, which lacks the abundant collagen bundles seen in the stroma.

Time-lapse images of baseline dSEARCH performed by multiple intraepithelial LCs. The data set shown in Fig. 2(a) was compiled to show dynamic movement of EGFP+ corneal LCs. Note that most of EGFP+ LCs with characteristic dendritic morphology exhibit the dSEARCH motion in the epithelial compartment, while rapid migration is observed with smaller EGFP+ cells possessing a polygonal shape primarily in the stromal compartment. The movie represents 18 independent imaging experiments; the dSEARCH index values for the LCs shown in this movie are within the normal variations measured for more than 170 LCs before any treatment (see Figs 3c, 5c, 6c, and 8c).

Time-lapse images of dSEARCH. The data set from an independent imaging experiment was compiled to show baseline dSEARCH by EGFP+ corneal LCs. The dSEARCH index values for the LCs shown in this movie are within the normal variations measured for more than 170 LCs before any treatment (see Figs 3c, 5c, 6c, and 8c).

Time-lapse images of injury-induced augmentation of dSEARCH. The four movies demonstrate injury-induced amplification of dSEARCH and lateral movement of EGFP+ LCs observed consistently in eight independent experiments. After 60 min recording of baseline behaviours, pinpoint thermal injury was produced at time 0 in an EGFP+ LC target indicated with an arrow. Behavioural responses of the LCs shown in the movies are within the normal variations in the dSEARCH index values (Fig. 3c) and the mean travelled distance values (Fig. 4c) measured with more than 20 LCs before and after thermal injury. Note the increased activity of the dendrites and the propensity for lateral movement within the epithelium after injury. In one imaging experiment, a large stromal EGFP+ cell with an amorphous cell shape (indicated with an asterisk) exhibited an unusual response characterized by rapid migration toward the injury site, followed by casting fine mesh-like projections toward neighboring LCs (Movie S9).

Time-lapse images of the impact of IL-1Ra on injury-triggered changes in LC behaviours. Data sets shown in Fig. 5(a) (Movie S10) and from an independent experiment (Movie S11) were compiled to show dynamic behavioural responses of corneal LCs to local injury in the presence of IL-1Ra, which was added to the circulating media at time −60 min to achieve a final concentration of 200 ng/ml. After recording of baseline behaviours, pinpoint thermal injury was produced at time 0 in an EGFP+ LC target (indicated with an arrow). Note how the activity of the dendrites does not change appreciably after injury and how EGFP+ LCs do not move significantly from their original positions. Behavioural responses of the LCs shown in the movies are within the normal variations in the dSEARCH index values (Fig. 5c) and the mean travelled distance values (Fig. 4c) measured with a total of 20 LCs before and after thermal injury in the presence of IL-1Ra.

Time-lapse images of IL-1-induced amplification of dSEARCH. Data sets shown in Fig. 6(a) (Movie S12) and from an independent experiment (Movie S13) were compiled to show dynamic behavioural responses of corneal LCs to IL-1. After 60 min recording of baseline behaviours, IL-1α was added to the circulating media at time 0 to achieve a final concentration of 5 pg/ml. Note an increase in the activity of the dendrites after addition of IL-1. Behavioural responses of the LCs shown in the movies are within the normal variations in the dSEARCH index values (Fig. 6c) and the mean travelled distance values (Fig. 4c) measured with more than 18 LCs after IL-1 treatment.

Time-lapse images of dendrite hyper-elongation triggered by IL-1 at high concentrations. The data set shown in Fig. 7(a) was compiled to show dynamic behavioural responses of corneal LCs to IL-1. After 60 min recording of baseline behaviours, recombinant IL-1α was added to the circulating media at time 0 to achieve a final concentration of 100 pg/ml. Note the profound elongation of the dendrites in the absence of significant lateral movement. The movie represents three independent imaging experiments showing IL-1-induced bidirectional dendrite hyper-elongation by corneal LCs.

Time-lapse images of TNF-α-induced changes in LC behaviours. Data sets shown in Fig. 8(a) (Movie S15) and from an independent experiment (Movie S16) were compiled to show dynamic behavioural responses of corneal LCs to TNF-α. After 60 min recording of baseline behaviours, TNF-α was added to the circulating media at time 0 to achieve a final concentration of 50 pg/ml. Note an increase in dendrite activity and lateral movement similar to the changes seen after tissue injury. Behavioural responses of the LCs shown in the movies are within the normal variations in the dSEARCH index values (Fig. 8c) and the mean travelled distance values (Fig. 4c) measured for more than 25 LCs before and after TNF-α treatment.