Abstract

Therapy with interferon-β (IFN-β) has well-established clinical effects in multiple sclerosis (MS), albeit the immunomodulatory mechanisms are not fully understood. We assessed the prevalence and functional capacity of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in healthy donors, and in untreated and IFN-β-treated MS patients, in response to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG). The proportion of CD45RO+ memory T cells was higher in MS patients than in healthy donors, but returned to normal values upon therapy with IFN-β. While CD45RO+ CD4+ T cells from all three groups responded to MOG in vitro, untreated patients showed augmented proliferative responses compared to healthy individuals and IFN-β treatment reduced this elevated reactivity back to the values observed in healthy donors. Similarly, the response of CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells to MOG was strongest in untreated patients and decreased to normal values upon immunotherapy. Overall, the frequency of peripheral CD45RO+ memory T cells ex vivo correlated with the strength of the cellular in vitro response to MOG in untreated patients but not in healthy donors or IFN-β-treated patients. Compared with healthy individuals, responding CD4+ and CD8+ cells were skewed towards a type 1 cytokine phenotype in untreated patients, but towards a type 2 phenotype under IFN-β therapy. Our data suggest that the beneficial effect of IFN-β in MS might be the result of the suppression or depletion of autoreactive, pro-inflammatory memory T cells in the periphery. Assessment of T-cell subsets and their reactivity to MOG may represent an important diagnostic tool for monitoring successful immunotherapy in MS.

Keywords: autoimmunity, CFSE (5- (and 6-) carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester), disease progression, immunotherapy, myelin antigens, T-cell responses

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a complex autoimmune disease associated with inflammation in the white matter of the central nervous system (CNS), leading to demyelination of axonal sheaths, degradation of nerve tissue and, eventually, irreversible damage.1 Relapsing–remitting MS is characterized by periods of neurological dysfunction followed by periods of stability, while patients with primary or secondary progressive MS show a slow accumulation of disability with or without exacerbation. Although the aetiology of MS remains largely unknown, the target antigens of the autoimmune response in MS appear to be part of the CNS myelin, such as myelin basic protein (MBP) and proteolipid protein as the most common myelin proteins, and minor constituents like myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), myelin-associated glycoprotein, and αB-crystallin.2–4

Interferon-β (IFN-β) has well-established clinical benefits in patients with relapsing–remitting MS with respect to relapse rates and frequencies of gadolinium-enhancing lesions,5,6 yet its immunomodulatory mechanism of action is not fully understood. Therapy with IFN-β modulates cytokine levels, affects the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules, and stabilizes the blood–brain barrier, thereby presumably inhibiting transmigration of autoreactive T cells into the CNS.7 Moreover, IFN-β may also inhibit T-cell activation and proliferation directly.8–10 However, despite the long-standing clinical experience with IFN-β no immunological markers have been defined that would allow assessment of the efficacy of treatment and prediction of the degree of disease progression; monitoring of neurological parameters therefore remains the method of choice.

In an attempt to understand the immunological basis of MS, numerous studies have been conducted on the cellular reactivity to myelin antigens but they have led to ambiguous or even contradictory conclusions. While autoreactive immune cells such as those recognizing myelin proteins are present in all individuals, some investigators demonstrated marked differences in myelin reactivity between MS patients and healthy donors, others reported that such differences may not exist.11–16 This discrepancy might be partly due to the low and hardly detectable numbers of autoantigen-specific T cells in the circulation, and the fact that the autoimmune response is directed to a range of epitopes at the same time, which may differ between individuals.1

Detection and phenotyping of autoreactive T cells in short-term in vitro assays have been a technological challenge until recently. The latest development of novel techniques such as enzyme-linked immunospot analysis, intracellular cytokine staining and MHC class II tetramers has allowed more accurate quantification of antigen-specific T cells for the early diagnosis and immunomonitoring of autoimmune diseases.13,17, 18 In the present cross-sectional study we characterized the phenotype and functional profile of autoreactive T cells from untreated and IFN-β-treated MS patients by optimizing a highly sensitive 5- (and 6-) carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) -based flow cytometric assay.19–22 We provide evidence that at least part of the beneficial effect of IFN-β treatment in MS might be a consequence of the suppression or depletion of autoreactive, pro-inflammatory memory T cells in the periphery.

Materials and methods

Patients and control subjects

All procedures were approved by the local Ethics Committee for Clinical Research at the University of Giessen and conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. Blood samples taken from 15 untreated patients who fulfilled the standard criteria for the diagnosis of relapsing–remitting MS23 were analysed in this study; the patients had had no relapse in the previous 3 months, had Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores ≤4·0 or less, and had received no treatment with immunomodulatory agents (e.g. IFN-β or glatiramer acetate) or corticosteroids for at least 3 months before the blood sampling (Table 1). The IFN-β-treated group consisted of 16 relapsing–remitting MS patients with neither relapse nor corticosteroid treatment within the previous 3 months, with EDSS scores ≤4·0, who were under current therapy with Rebif® (IFN-β1a; Serono, Geneva, Switzerland) or Betaferon® (IFN-β1b; Schering, Berlin, Germany) for at least 6 months, with no prior immunomodulatory therapy. Buffy coats from 14 healthy blood donors who were serologically negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C virus, and syphilis, were kindly provided by the Institut für Klinische Immunologie und Transfusionsmedizin, Universität Giessen.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients and healthy individuals at the time of blood sampling

| Group | Age1 | Years since diagnosis1 | EDSS scores1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy donors | 30·4 ± 10·1 | – | – |

| (n = 14) | (20·1–47·5) | ||

| Untreated | 40·0 ± 7·6 | 8·3 ± 7·0 | 2·7 ± 1·1 |

| patients (n = 15) | (29·6–51·6) | (0·4–22·6) | (0·5–4·0) |

| IFN-β-treated | 37·6 ± 6·8 | 8·5 ± 6·3 | 2·1 ± 1·4 |

| patients (n = 16) | (25·4–50·8) | (0·9–23·1) | (0·0–4·0) |

Means ± standard deviations (range).

From all three groups, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated within a maximum of 2 hr after blood collection by density centrifugation over lymphocyte separation medium (ICN Biomedicals, Eschwege, Germany), gently frozen using a Nicool Plus cell freezing machine (Air Liquide, Düsseldorf, Germany), and stored in liquid nitrogen until further use.

Stimulation assays

PBMC were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well in 200 μl RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 25 mm HEPES, 2 mm l-glutamine, 25 μg/ml gentamycin (all Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), and 10% heat-inactivated pooled human AB serum (Bayerisches Rotes Kreuz, Augsburg, Germany). Recombinant human MOG, amino acids 1–125 (MOG1−125), was expressed in Escherichia coli as described before11,24 and used at 10 μg/ml; native human MBP was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany) and used at 20 μg/ml. Tetanus toxoid (TT) concentrate (Chiron Behring, Marburg, Germany) was used at 40 lytic-forming units (LfU)/ml. The overall proliferative capacity was tested using 2·5 μg/ml phytohaemagglutinin (Sigma-Aldrich) as the mitogenic control. Total cell proliferation was assessed by addition of 1 μCi [3H]thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany) per well on day 6 of culture, and cells were collected 6 hr later on glass-fibre filters using a Micromate 196 cell harvester (Packard, Meriden, CT). The incorporated radioactivity was measured using a Matrix 9600 β-counter (Packard). Stimulation indices were calculated by dividing the mean counts/min (c.p.m.) in antigen-containing cultures by the mean c.p.m. in medium controls.

Proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was monitored by initial labelling of PBMC samples with CFSE (Molecular Probes, Leiden, the Netherlands). PBMC were resuspended at 1 × 107/ml in RPMI-1640 with no serum, and CFSE was added to a final concentration of 7 μm for 5 min at room temperature. CFSE-labelled PBMC were then incubated with or without antigens in complete culture medium as described above, and after 6 days half of the supernatant was replaced by fresh medium supplemented with recombinant human interleukin-2 (IL-2; Proleukin; Chiron, Munich, Germany) to a final concentration of 10 U/ml. Proliferating CFSE-labelled cells were analysed after another 4 days by flow cytometry.

For intracellular cytokine detection, PBMC were incubated with or without antigens. After 6 days half of the supernatant was replaced by fresh medium supplemented with IL-2. On day 10, cells were re-stimulated in the presence of 1 × 105 irradiated (50 Gy) autologous, antigen-pulsed (10 μg/ml MOG, 20 μg/ml MBP, or 40 LfU/ml TT for 1·5 hr) or non-pulsed PBMC per well.25 The cytokine profiles of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were analysed 3 days after re-stimulation by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. Cells treated with 50 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma) and 1 μm ionomycin (Sigma) for 1 hr served as positive controls for cytokine production.

Flow cytometry analysis

Cells were harvested at appropriate time-points, and analysed on a four-colour Epics XL flow cytometer supported with Expo32 ADC software (Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany)26 using the following monoclonal mouse anti-human antibodies from Beckman Coulter: CD3–PE-Texas Red (ECD)[immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1), clone UCHT1], CD4–fluorescein isothiocyanate or CD4–PE-Cy5 (PC5) (IgG1, clone 13B8.2), CD8–PC5 (IgG1, clone B9.11), and CD45RO–phycoerythrin (PE; IgG2a, clone UCHL1), or appropriate isotype controls. For detection of intracellular cytokines in re-stimulated T cells, brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the cultures at 10 μg/ml 4 hr before harvesting. Surface-stained cells were subsequently fixed and permeabilized using the Fix & Perm kit (Caltag, Hamburg, Germany), in the presence of IFN-γ–PE (IgG1, clone 45.15) or IL-4–PE (IgG1, clone 4D9) antibodies (Beckman Coulter).

Optimal compensation and gain settings were determined for each experiment using unstained, single-stained and multistained samples. Gates were set on live CD3+ lymphocytes based upon their appearance in forward/side-scatter and the corresponding fluorescence patterns; apoptotic and necrotic cells were largely excluded by these settings, as confirmed by counterstainings with propidium iodide and annexin V (Beckman Coulter). Results obtained from 30 000 events were expressed as the percentage of PE- or CFSE-positive cells among CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Proliferation was expressed as the percentage of undivided, non-proliferating cells (CFSEhi) and of divided, proliferating cells (CFSElo); the stimulation index was calculated as the ratio between the mean percentage of CFSElo cells in antigen-containing cultures and the mean percentage of CFSElo cells in medium controls. Reproducibility of the assays was verified by repeated analysis of selected blood samples (e.g. 48·7 ± 3·4% undivided, CFSEhi CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells in response to MOG in three independent experiments using the same PBMC sample from an untreated patient), and by analysis of blood samples taken from the same donor at two different time-points within 3 months (e.g. 88·2 ± 4·0%, 34·0 ± 11·3% and 15·7 ± 10·9% undivided, CFSEhi CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells in three different untreated patients).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows software (Chicago, IL). Normal distribution of data was assessed using Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Two-sided, unpaired Student's t-tests were used for normally distributed data. For continuous data, comparisons between groups were based on non-parametric two-sided exact Mann–Whitney U-tests for independent samples, and Wilcoxon tests for dependent samples. Spearman's correlation coefficients were determined for correlation analyses. In each case, probability values of P < 0·05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

IFN-β therapy reduces the frequency of CD45RO+ memory T cells

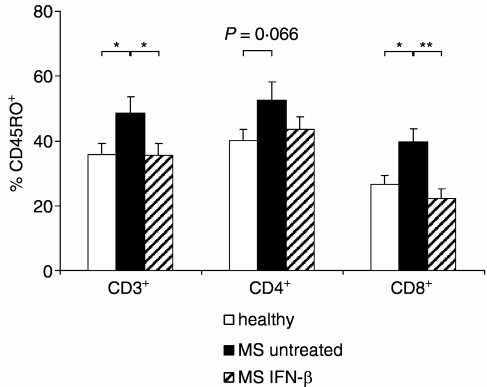

In a phenotypical characterization of PBMC from healthy donors and untreated and treated MS patients ex vivo, we observed striking differences between the three groups with respect to the expression of the memory marker CD45RO. Untreated MS patients had higher frequencies of CD45RO+ CD3+ lymphocytes compared to healthy donors and IFN-β-treated patients, whereas the percentages of CD45RO+ CD3+ lymphocytes in the latter two groups were comparable (Fig. 1). While this pattern was only of borderline significance with respect to the CD4+ T-cell population, pronounced differences between untreated MS patients and healthy donors, as well as between untreated and IFN-β-treated patients, were found for CD8+ T cells, with a tendency towards even lower numbers of CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells in IFN-β-treated patients than in healthy individuals (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Frequencies of CD45RO+ T cells in healthy donors (n =14) and in untreated (n = 15) and IFN-β-treated (n = 16) MS patients. Data shown are mean values and SEM for expression of CD45RO in CD3+ lymphocytes, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in each group. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01.

The autoreactive response is driven by both CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells

To characterize the nature of the autoreactive in vitro T-cell responses and to evaluate potential differences in patients versus healthy donors, we used a modified flow cytometric proliferation assay based on sequential dilution of CFSE27 where the medium was changed on day 6 of culturing and supplemented with 10 U/ml IL-2 to promote T-cell proliferation and survival of anergic T cells.11,28 In pilot experiments, no reduction in CFSE intensity was observed in the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations after the addition of IL-2 in the absence of antigenic stimulation, indicating that IL-2 alone did not bias the experimental outcome (data not shown).

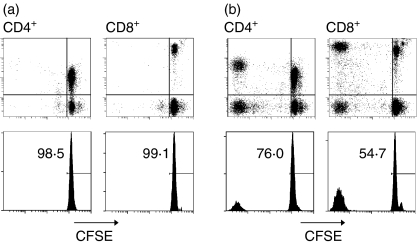

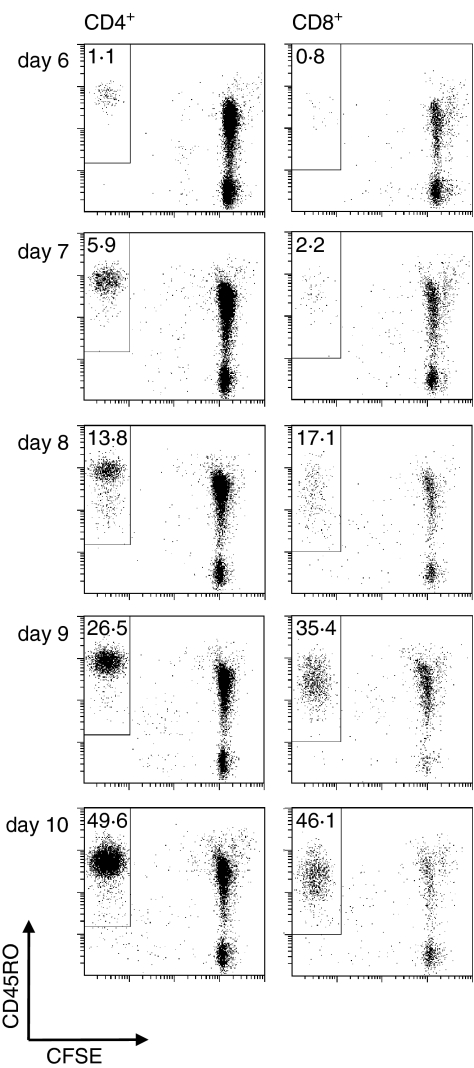

T-cell responses varied greatly between individuals. Some PBMC samples did not react to MOG, characterized by the virtual absence of CFSElo CD4+ and CD8+ T cells after 6–10 days (Fig. 2a) despite a strong response to the control antigen TT and the mitogen phytohaemagglutinin (data not shown). In other cases, we noted mixed proliferative responses by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2b), or responses that were greatly dominated by either CD4+ T cells or, less often, by CD8+ T cells (data not shown). The vast majority of the responding CD4+ and CD8+ T cells shared a CD45RO+ memory phenotype, as shown by the time–course experiment depicted in Fig. 3. During the first 6 days in culture, only a small proportion of T cells became CFSElo, while substantial CD45RO+ CD4+ and CD45RO+ CD8+ T-cell proliferation was detected in response to autoantigens from day 8.

Figure 2.

Pattern of typical T-cell responses in a non-responding (a) and a responding (b) MS patient. PBMC were labelled with CFSE and incubated with MOG for 6 days, after which half of the supernatant was replaced by fresh medium supplemented with IL-2. After a total of 10 days, cells were harvested, and the CFSE fluorescence intensity was analysed. Upper panels are dot plots showing the signals for CFSE and CD4 or CD8 within the CD3+ gate. Lower panels are projections of the CFSE signals onto histograms gated on CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ lymphocytes, respectively, showing the percentage of residual undivided, i.e. non-proliferating CFSEhi cells.

Figure 3.

Time–course experiment showing a typical proliferative response of autoreactive CD45RO+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. CFSE-labelled PBMC from an untreated MS patient were incubated in the presence of MOG for 6 days, after which half of the supernatant was replaced by fresh medium supplemented with IL-2. At the time-points indicated, proliferation was assessed as dilution of the CFSE signal. Numbers indicate the percentage of CFSElo CD45RO+ cells among CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively.

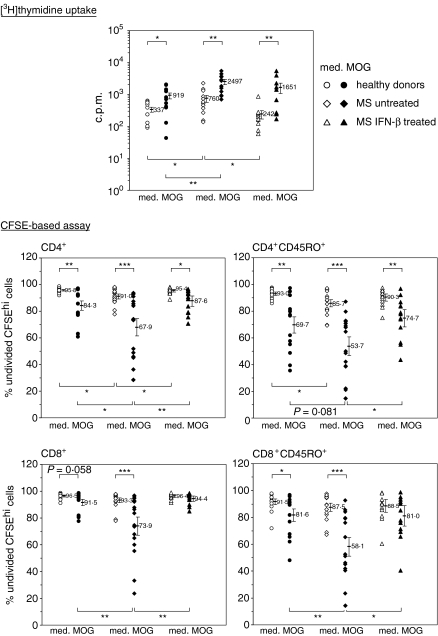

IFN-β therapy reduces the autoreactive response of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to MOG

CFSE-labelled PBMC from healthy donors and from untreated and IFN-β-treated MS patients were cultured in the presence of MOG. In all three groups, CD4+ T cells responded to MOG in comparison to the medium controls. However, the percentage of undivided, non-proliferating CFSEhi CD4+ T cells was significantly lower in untreated MS patients than in healthy donors, whereas the reactivity of CD4+ T cells in IFN-β-treated patients did not differ from that in healthy donors (Fig. 4). Similar patterns were observed in the CD45RO+ CD4+ memory T-cell subset but with higher variability within the groups. As for CD8+ T cells, MOG-reactive responses were observed in healthy donors and, much more pronounced, in untreated MS patients. In analogy to the situation with CD45RO+ CD4+ T cells, only CD45RO+ CD8+ memory T cells from healthy donors and untreated MS patients showed a significant reactivity to MOG compared to the medium controls, as opposed to patients under IFN-β therapy. Importantly, no differences between untreated and treated patients were seen in the proliferative responses to TT (22·5 ± 8·3% versus 22·7 ± 14·6% undivided, CFSEhi CD45RO+ CD4+ T cells; and 41·6 ± 12·4% versus 36·5 ± 14·4% undivided, CFSEhi CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells.

Figure 4.

MOG-driven T-cell responses in healthy donors (n = 14) and in untreated (n = 15) and IFN-β-treated (n = 14) MS patients. For conventional thymidine uptake assays, PBMC were incubated with medium alone (med.), or in the presence of MOG (MOG). After 6 days, [3H]thymidine was added to each well, and cells were collected 6 hr later. Data shown represent the mean radioactivity in c.p.m. from cultures set up in triplicate. For flow cytometric assays, CFSE-labelled PBMC were cultured with or without MOG for 6 days, after which half of the supernatant was replaced by fresh medium supplemented with IL-2. After a total of 10 days, cells were harvested, and the CFSE fluorescence intensity was analysed. Data show individual proliferative responses as mean percentage of undivided, i.e. non-proliferating CFSEhi cells within the indicated CD3+ lymphocytes gates from cultures set up in triplicate. Error bars indicate the mean values ± SEM for each group. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001.

Conventional [3H]thymidine uptake assays conducted in parallel with the CFSE dilution experiments resulted in similar differences between the groups (Fig. 4, top panel), and in a highly significant correlation between [3H]thymidine incorporation in the presence of MOG on one hand, and the proliferation of CD4+ memory T cells (R = 0·56; P < 0·001) and CD8+ memory T cells (R = 0·67; P < 0·001), respectively, on the other hand. Notably, while there were no differences between the groups with respect to MOG-specific stimulation indices for CD4+ and CD45RO+ CD4+ T-cell proliferation, stimulation indices for CD8+ and CD45RO+ CD8+ T-cell proliferation were significantly higher in untreated patients compared to IFN-β-treated patients, and (for CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells) also when compared to healthy individuals (Table 2).

Table 2.

Stimulation indices for the MOG-driven T-cell responses depicted in Fig. 4

| [3H]thymidine uptake1 | CFSE-based assay1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | c.p.m. | CD4+ | CD45RO+ CD4+ | CD8+ | CD45RO+ CD8+ |

| Healthy donors | 2·3 ± 1·1 | 3·0 ± 0·8 | 3·7 ± 0·7 | 1·9 ± 0·5 | 1·9 ± 0·6 |

| P | ns | ns | ns | ns | * |

| Untreated patients | 3·7 ± 2·3 | 2·9 ± 0·9 | 2·8 ± 0·6 | 2·8 ± 0·6 | 2·9 ± 0·7 |

| P | ns | ns | ns | ** | * |

| IFN-β-treated patients | 4·7 ± 2·4 | 2·3 ± 0·7 | 2·5 ± 0·9 | 1·4 ± 1·1 | 1·5 ± 1·1 |

Geometric means ± standard errors. Individual simulation indices were calculated as the ratio between the lsqb;3H]thymidine uptake in the presence of MOG and the corresponding medium controls, or as the ratio between the frequency of divided CFSElo cells in the presence of MOG and the corresponding medium controls. Statistical differences between untreated patients and healthy donors, and between untreated patients and IFN-β-treated patients are indicated by asterisks; ns, not significant

P < 0·05

P < 0·001. Group sizes were: healthy donors, n = 14; untreated patients, n = 15; IFN-β-treated patients, n = 14 (except for c.p.m. values n = 16).

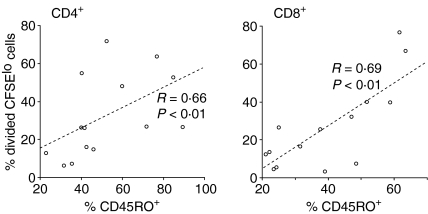

The MOG-induced CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation in MS patients correlates with the frequency of CD45RO+ cells

Next, the correlation between the proliferative response of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vitro, and the initial frequency of CD45RO+ cells among CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the blood ex vivo were analysed. For either population, the percentage of proliferating CFSElo cells in the presence of MOG correlated with the expression of CD45RO in untreated MS patients (Fig. 5) but not in healthy donors or in IFN-β-treated MS patients (data not shown), suggesting that the strength of the proliferative response in MS patients reflected the number of potentially autoreactive memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the circulation. Also, no correlation was found between the initial frequency of CD45RO+ cells ex vivo and the proliferative response to TT in vitro (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Correspondence of the initial frequency of CD45RO+ cells in untreated MS patients ex vivo (i.e. on day 0) with the MOG-specific response of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, shown as percentage of divided, i.e. proliferating, CFSElo cells on day 10 (n = 15). Correlations were analysed by applying Spearman's rank correlation coefficients.

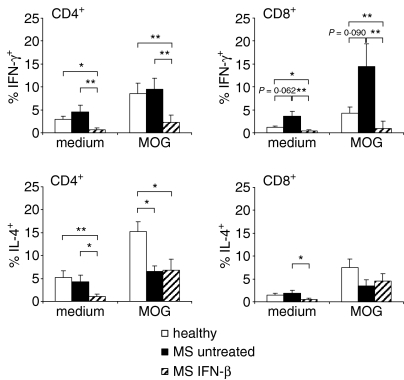

Autoreactive T cells of MS patients are skewed towards a type 1 cytokine phenotype

Pro-inflammatory T cells are usually considered pathogenic in MS, and thus the cytokine profiles of the autoreactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were determined. PBMC from healthy donors and untreated MS patients were cultured in the presence of MOG, and were re-stimulated by irradiated autologous autoantigen-pulsed PBMC as antigen-presenting cells (APC). No significant quantitative differences in IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells could be discerned between untreated patients and healthy donors, although in both groups re-stimulation with antigen-pulsed cells led to an increased production of IFN-γ, compared to medium controls (Fig. 6). In contrast to the situation of CD4+ T cells, IFN-γ production by antigen-stimulated CD8+ T cells was elevated in untreated patients compared to healthy donors. Furthermore, CD4+ T cells from MS patients expressed lower levels of IL-4 in response to MOG than did healthy donors, whereas the percentage of IL-4-producing CD8+ T cells was low and comparable in both groups, both with and without antigenic stimulation. Strikingly, in patients under IFN-β therapy neither CD4+ nor CD8+ T cells produced significant amounts of IFN-γ in response to MOG, and IL-4 expression was also reduced (Fig. 6), despite an unaffected cytokine production in PMA/ionomycin-stimulated cells (data not shown). However, a similarly abrogated cytokine production was observed in IFN-β-treated patients in response to TT, compared with healthy donors (4·0 ± 1·4% versus 10·2 ± 1·3% IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells; 1·7 ± 0·7% versus 5·7 ± 1·6% IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells; 3·5 ± 0·8% versus 14·7 ± 2·8% IL-4+ CD4+ T cells; and 2·1 ± 0·5% versus 11·3 ± 2·6% IL-4+ CD8+ T cells; intermediate TT responses in untreated patients were not statistically different from either healthy controls or IFN-β-treated patients).

Figure 6.

Mean intracellular cytokine production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from healthy donors (n = 13) and from untreated (n = 13) and IFN-β-treated (n = 8) MS patients. PBMC were cultured in the presence of MOG or TT for 6 days, after which half of the supernatant was replaced by fresh medium supplemented with IL-2. On day 10, the cells were re-stimulated with irradiated antigen-pulsed PBMC in IL-2-containing medium. T cells were stained after another 3 days, and intracellular cytokines were analysed. Bars indicate the mean values + SEM for IFN-γ and IL-4 production by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in each group. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01.

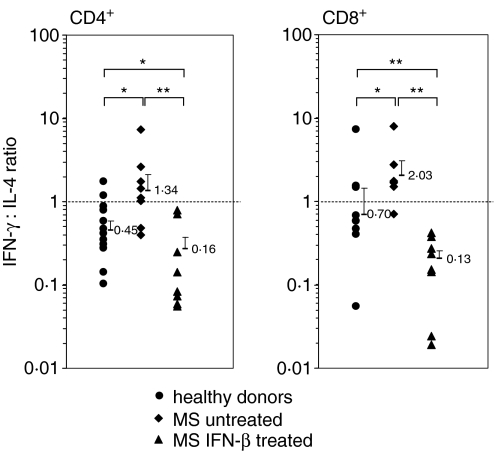

When calculating the IFN-γ : IL-4 ratio for each T-cell subset, it became apparent that CD4+ T cells from untreated MS patients were skewed towards a type 1 phenotype (IFN-γ : IL-4 > 1·0) because they produced similar amounts of IFN-γ to healthy donors but lower amounts of IL-4 (IFN-γ : IL-4 < 1·0) in response to MOG (Fig. 7). In contrast, CD8+ T cells from untreated MS patients were also skewed towards a type 1 phenotype because they produced similar amounts of IL-4 to healthy donors but higher amounts of IFN-γ. Most importantly, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from IFN-β-treated MS patients were highly polarized towards a type 2 phenotype, mainly because their production of IFN-γ was almost totally abrogated.

Figure 7.

Ratios of IFN-γ : IL-4 expression in MOG-stimulated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Data show ratios in individual healthy donors (n = 13) and in untreated (n = 13) and IFN-β-treated (n = 8) MS patients. Error bars indicate the geometric means + SEM for each group. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01.

Discussion

Current theories on the induction and progression of MS place autoreactive CD4+ T helper type 1 (Th1) cells in the centre of autoimmune pathogenesis, although investigators are becoming increasingly aware of an important contribution of CD8+ T cells as potent effectors and mediators of CNS damage.29 Recent studies indicate that the immune response in MS engages a broader range of immune cells, including CD8+ T cells and B lymphocytes, that target various brain antigens.2–4,21,30,31 Even more, CD8+ T cells usually outnumber CD4+ T cells in the CNS of MS patients, and clonal expansion of T cells in MS lesions is detected more frequently among CD8+ than CD4+ T cells.32–34

Crawford et al. found that both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells recognizing CNS autoantigens are widely prevalent in MS patients and healthy individuals.21 In our own study, the reactivity of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to MOG was considerably elevated in untreated MS patients compared to those in healthy donors; conventional [3H]thymidine incorporation assays conducted in parallel with the CFSE assays resulted in the same significant differences between the groups (Fig. 4). While being only a minor component of CNS myelin, the highly immunogenic protein MOG is not located in compact myelin like MBP but rather is found on the outer surface of the oligodendrocyte membrane, thereby making it more accessible for cellular and humoral autoimmune mechanisms.15,28,35,36 The fact that in our own experiments MOG was the better protein, compared to MBP, for distinguishing the T-cell response between healthy donors and untreated MS patients (our own unpublished observations) supports the idea that MOG is the more relevant target in the induction and progression of pathology in MS.35,37

The vast majority of responding CD8+ T cells appeared to be classical memory T cells that were CD45RO+ (Fig. 3), which is in line with earlier studies showing specific enrichment and oligoclonal expansion of CD45RA– CD45RO+ CD8+ memory T cells in the cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients.16 Also, CD8+ T-cell lines isolated from MS patients that recognized endogenously processed MBP belonged to the CD45RA–CD45RO+ CD8+ memory T-cell subset.34 Most recently, Okuda et al. reported that activation of CD45RO+ CD4+ memory T cells is associated with an exacerbation of MS, while activation of CD45RO+ CD8+ memory T cells may reflect systemic immunological dysregulation in MS patients.38 In our study, the degree of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation correlated with the initial frequency of CD45RO+ T cells in MS patients but not in healthy subjects (Fig. 5), which might be the result of pre-activation of T cells by myelin autoantigens in MS patients in vivo39 and suggests that the pronounced in vitro responses may reflect the number of potentially autoreactive memory T cells in the peripheral blood.

The response of CD8+ T cells to recombinant MOG1−215 in our assays was surprising because it is difficult to envisage how a large exogenous protein can be endocytosed efficiently, processed and then presented to CD8+ T cells in the context of MHC class I molecules. Previous studies on the role of CD8+ T cells in MS used short antigenic peptides,21 which may bind directly to MHC class I molecules on the surface of APC.40 The strong cell proliferation might have been in part the result of an unspecific expansion of pre-activated CD8+ T cells in our cultures; help provided by MOG-specific CD4+ T cells might then boost the reactivity of those CD8+ T cells even further.41 Although a thorough analysis of whether the proliferative response we observed was indeed due to expansion of in vitro-stimulated, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells was beyond the scope of the present study, intriguing unconventional molecular mechanisms have been uncovered that may explain how CD8+ T cells respond to extracellular antigens.42 APC such as dendritic cells are capable of cross-presentation by transferring exogenous proteins into the MHC class I pathway43,44 or of directly transferring antigen-laden MHC class I complexes and costimulatory molecules to expanding CD4+ T cells, which then in turn are able to present these epitopes to CD8+ T cells and initiate a productive cytotoxic T-cell response.45 Other APC that might be of relevance for the stimulation of CD8+ T cells in PBMC cultures comprise monocytes, B cells, and γδ T cells.46–48

Although CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from both healthy donors and MS patients responded to MOG, these cells had different functional characteristics (Fig. 7). Pro-inflammatory cytokines are thought to play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of MS by activating the immune system in the periphery and/or by directly damaging the oligodendrocyte.49,50 While CD4+ T cells from both groups produced IFN-γ and IL-4, higher levels of IL-4 were determined in CD4+ T cells from healthy donors than in those from MS patients, implying that CD4+ T cells from MS patients are skewed towards a Th1 phenotype, whereas CD4+ T cells of healthy donors are skewed towards a Th2 phenotype. At the same time, CD8+ T cells from MS patients were characterized by a stronger production of IFN-γ than those from healthy donors, presumably because of the more pro-inflammatory background in MS patients, who lack the compensatory secretion of IL-4 by CD4+ T cells that is seen in healthy donors.

The functional properties of myelin-reactive T cells, as detected in the present study, are corroborated by previous reports that showed a shift toward a Th1-type antigen-specific response in long-term T-cell lines derived from MS patients, whereas mixed Th0/Th2 or Th0/Th1 phenotypes were observed in healthy donors.18,28, 51 Bielekova et al. found a correlation between MBP-specific Th1 cells and a more destructive disease process as detected by magnetic resonance imaging of the CNS.52 In contrast to these reports, other studies failed to detect significant differences in the percentage of T cells secreting IFN-γ, IL-2 and tumour necrosis factor-α between MS patients and healthy controls;49 however, the percentage of T cells producing IFN-γ was significantly correlated with the EDSS scores in female MS patients.50

The clinical relevance of CD8 + T cells producing IFN-γ in response to MOG is not entirely clear. Crawford et al. showed that proliferating CD8 + T cells from MS patients secrete IFN-γ as well as IL-1021 and future therapies may therefore aim at increasing the regulatory properties of the CD8 + T-cell population.29 Of note, the percentage of IFN-γ-producing CD8 + T cells was recently reported to be associated with increased disability scores while there is no such correlation in IFN-β treated MS.53

Therapy with IFN-β reduced the frequency of peripheral CD45RO + T cells, suppressed the proliferation of both CD4 + and CD8 + T cells, and abrogated the production of IFN-γ, and thereby rescued the immunopathology-associated autoreactivity in MS patients (Figs 1,Figs 4 and Figs 6). IFN-β is the principle immunomodulatory agent used for the treatment of relapsing–remitting MS because it lowers the relapse rate as well as the frequency of gadolinium-enhancing lesions.5, 6 However, IFN-β has only a modest impact on the overall disease progression, and approximately one in three MS patients does not respond at all to the therapy.36, 54, 55 Among the manifold immunomodulatory activities of IFN-β described are up-regulation and increased shedding of adhesion molecules, induction of IL-10 and neurotrophic factors, inhibition of matrix metalloproteases, and reduction of cell adhesion to the blood–brain barrier.7, 36,56–60 Consequently, IFN-β is thought to exert part of its beneficial effect by limiting the transmigration of activated pro-inflammatory T cells across the blood–brain barrier into the CNS.61,62

Another possible mechanism underlying the therapeutic effect of IFN-β is the inhibition of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activation and proliferation.8–10 Based on the difficulties they had in establishing MOG-reactive T-cell clones from IFN-β-treated MS patients, Koehler et al. concluded that therapy with IFN-β might reduce the number of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in the periphery.28 The suppressive effect on T cells might be the result of interference with costimulatory pathways, as IFN-β treatment reduces the elevated levels of CD80-induced IL-2 production observed in relapsing–remitting MS patients.57 This is in line with observations that IFN-β up-regulates the CD80-related protein B7-H1 and tolerogenic HLA-G molecules on monocytes, which might thereby restore a state of peripheral tolerance.59,63

With respect to CD8+ T cells, Oh et al. reported most recently that IFN-β therapy not only reduced spontaneous lymphoproliferation but also the frequency of potentially pathogenic CD8+ T cells in human T-lymphotropic virus type I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP), an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder of the CNS.64 The authors' speculation that IFN-β-treated HAM/TSP patients benefit from a decrease in the pool of autoreactive lymphocytes capable of infiltrating the CNS and exerting cytotoxic functions is well matched by our own observation on CD8+ T cells in IFN-β-treated MS patients. This suppression of pro-inflammatory T cells upon IFN-β therapy might be achieved by rescue of the impaired susceptibility to apoptotic elimination of autoreactive T cells65 or by recovery of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cell effector functions.66,67 Whatever the precise molecular mechanism, our data may point towards a somewhat selective immunomodulation because IFN-β-treated patients had reduced proliferative reactivity to MOG but unaltered responses to TT, possibly by suppressing the expansion of pro-inflammatory T cells in an on-going autoimmune response while leaving the underlying pool of unrelated memory T cells unaffected. The outcome of an antigen-specific reduction of cell proliferation under immunotherapy is likely to be potentiated by the generally impaired capability of T cells to produce considerable levels of IFN-γ, be it in response to MOG or to TT, thus supporting earlier observations on the potential of peripheral lymphocytes to mount cytokine responses.68–70

Taken together, our data imply that at least part of the beneficial effect of IFN-β treatment in MS appears to be a consequence of the suppression or depletion of autoreactive pro-inflammatory CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells in the periphery. Assessment of the proportion of CD45RO+ cells within peripheral T cells, together with the in vitro reactivity of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to MOG, might represent an important diagnostic tool for evaluating the success of immunotherapy in MS. It now remains to be investigated in longitudinal studies whether the functional depletion of autoreactive memory T cells actually correlates with the clinical benefit upon therapy with IFN-β, and if so, how the relatively poor clinical efficacy of IFN-β might be further improved once the exact immunological mechanism of T-cell suppression is better understood.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. We gratefully acknowledge Herbert Kattenborn and Manfred Hollenhorst for their help with database management and statistical analysis; and Kerstin Retzlaff, Sabine Vogel, Hans-Joachim Misterek and René Röhrich for their excellent assistance.

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- CFSE

5- (and 6-) carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- CNS

central nervous system

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- HAM/TPS

human T-lymphotropic virus type I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis

- IFN

interferon

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IL-2

interleukin-2

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PE

phycoerythrin

- TT

tetanus toxoid

References

- 1.Hafler DA, Slavik JM, Anderson DE, O'Connor KC, de Jager P, Baecher-Allan C. Multiple sclerosis. Immunol Rev. 2005;204:208–31. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hafler DA. Degeneracy, as opposed to specificity, in immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2002;5:581–4. doi: 10.1172/JCI15198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kieseier BC, Hemmer B, Hartung HP. Multiple sclerosis – novel insights and new therapeutic strategies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:211–20. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000169735.60922.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sospedra M, Martin R. Immunology of multiple sclerosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:683–747. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Interferon β-1b is effective in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. I. Clinical results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 1993;43:655–61. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.4.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paty DW, Li DK UBC MS/MRI Study Group, IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. II. MRI analysis results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 1993;43:662–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.4.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theofilopoulos AN, Baccala R, Beutler B, Kono DH. Type I interferons (α/β) in immunity and autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:307–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudick RA, Carpenter CS, Cookfair DL, Tuohy VK, Ransohoff RM. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of mitogen-driven T-cell activation by recombinant interferon beta. Neurology. 1993;43:2080–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.10.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noronha A, Toscas A, Jensen MA. Interferon beta decreases T cell activation and interferon gamma production in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 1993;46:145–53. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(93)90244-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pette M, Pette DF, Muraro PA, Farnon E, Martin R, McFarland HF. Interferon-β interferes with the proliferation but not with the cytokine secretion of myelin basic protein-specific, T-helper type 1 lymphocytes. Neurology. 1997;49:385–92. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindert RB, Haase CG, Brehm U, Linington C, Wekerle H, Hohlfeld R. Multiple sclerosis. B- and T-cell responses to the extracellular domain of the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Brain. 1999;122:2089–99. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.11.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Noort JM, Bajramovic JJ, Plomp AC, van Stipdonk MJ. Mistaken self, a novel model that links microbial infections with myelin-directed autoimmunity in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;105:46–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danke NA, Koelle DM, Yee C, Beheray S, Kwok WW. Autoreactive T cells in healthy individuals. J Immunol. 2004;172:5967–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hellings N, Barée M, Verhoeven C, D'hooghe MB, Medaer R, Bernard CC, Raus J, Stinissen P. T-cell reactivity to multiple myelin antigens in multiple sclerosis patients and healthy controls. J Neurosci Res. 2001;63:290–302. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20010201)63:3<290::AID-JNR1023>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iglesias A, Bauer J, Litzenburger T, Schubart A, Linington C. T- and B-cell responses to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Glia. 2001;36:220–34. doi: 10.1002/glia.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobsen M, Cepok S, Quak E, et al. Oligoclonal expansion of memory CD8+ T cells in cerebrospinal fluid from multiple sclerosis patients. Brain. 2002;125:538–50. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelfrey CM, Rudick RA, Cotleur AC, Lee JC, Tary-Lehmann M, Lehmann PV. Quantification of self-recognition in multiple sclerosis by single-cell analysis of cytokine production. J Immunol. 2000;165:1641–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Aa A, Hellings N, Bernard CA, Raus J, Stinissen P. Functional properties of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-reactive T cells in multiple sclerosis patients and controls. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;137:164–76. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arbour N, Holz A, Sipe JC, Naniche D, Romine JS, Tyroff J, Oldstone MB. A new approach for evaluating antigen-specific T cell responses to myelin antigens during the course of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;137:197–209. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00080-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mannering SI, Morris JS, Stone NI, Jensen PK, Purcell AW, Honeyman MC, van Endert PM, Harrison LC. A sensitive method for detecting proliferation of rare autoantigen-specific human T cells. J Immunol Meth. 2003;283:173–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford MP, Yan SX, Ortega SB, et al. High prevalence of autoreactive, neuroantigen-specific CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis revealed by novel flow cytometric assay. Blood. 2004;103:4222–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Putz T, Ramoner R, Gander H, Rham A, Bartsch G, Höltl L, Thurnher M. Monitoring of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses after dendritic cell-based immunotherapy using CFSE due dilution analysis. J Clin Immunol. 2004;24:653–63. doi: 10.1007/s10875-004-6237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poser CM, Paty DW, Scheinberg L, et al. New diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines for research protocols. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:227–31. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith PA, Heijmans N, Ouwerling B, et al. Native myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein promotes severe chronic neurological disease and demyelination in Biozzi ABH mice. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1311–19. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meinl E, Weber F, Drexler K, et al. Myelin basic protein-specific T lymphocyte repertoire in multiple sclerosis. Complexity of the response and dominance of nested epitopes due to recruitment of multiple T cell clones. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2633–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI116879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eberl M, Engel R, Beck E, Jomaa H. Differentiation of human γδ T cells towards distinct memory phenotypes. Cell Immunol. 2002;218:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00519-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fulcher DA, Wong SW. Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester-based proliferative assay for assessment of T cell function in the diagnostic laboratory. Immunol Cell Biol. 1999;77:559–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1999.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koehler NK, Genain CP, Giesser B, Hauser SL. The human T cell response to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein: a multiple sclerosis family-based study. J Immunol. 2002;168:5920–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friese MA, Fugger L. Autoreactive CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis: a new target for therapy? Brain. 2005;128:1747–63. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hemmer B, Archelos JJ, Hartung H. New concepts in the immunopathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:291–301. doi: 10.1038/nrn784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goverman J, Perchellet A, Huseby ES. The role of CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis and its animal models. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2005;4:239–45. doi: 10.2174/1568010053586264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsuchida T, Parker KC, Turner RV, McFarland HF, Coligan JE, Biddison WE. Autoreactive CD8+ T cell responses to human myelin protein-derived peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10859–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babbe H, Roers A, Waisman A, et al. Clonal expansions of CD8+ T cells dominate the T cell infiltrate in active multiple sclerosis lesions as shown by micromanipulation and single cell polymerase chain reaction. J Exp Med. 2000;192:393–404. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zang YC, Li S, Rivera VM, Hong J, Robinson RR, Breitbach WT, Killian J, Zhang JZ. Increased CD8+ cytotoxic T cell responses to myelin basic protein in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2004;172:5120–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.5120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seamons A, Perchellet A, Goverman J. Immune tolerance to myelin proteins. Immunol Res. 2003;28:202–21. doi: 10.1385/IR:28:3:201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartung HP, Bar-Or A, Zoukos Y. What do we know about the mechanism of action of disease-modifying treatment in MS? J Neurol. 2004;251(Suppl. 5):v12–v29. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-1504-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerlero de Rosbo N, Milo R, Lees MB, Burger D, Bernard CC, Ben-Nun A. Reactivity to myelin antigens in multiple sclerosis. Peripheral blood lymphocytes respond predominantly to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2602–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI116875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okuda Y, Okuda M, Apatoff BR, Posnett DN. The activation of memory CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2005;235:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lovett-Racke AE, Trotter JL, Lauber J, Perrin PJ, June CH, Racke MK. Decreased dependence of myelin basic protein-reactive T cells on CD28-mediated costimulation in multiple sclerosis patients. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:725–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schumacher TN, Heemels MT, Neefjes JJ, Kast WM, Melief CJ, Ploegh HL. Direct binding of peptide to empty MHC class I molecules on intact cells and in vitro. Cell. 1990;62:563–7. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90020-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blachère NE, Morris HK, Braun D, Saklani H, di Santo JP, Darnell RB, Albert ML. IL-2 is required for the activation of memory CD8+ T cells via antigen cross-presentation. J Immunol. 2006;176:7288–300. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calzascia T, di Berardino-Besson W, Wilmotte R, Masson F, de Tribolet N, Dietrich PY, Walker PR. Cross-presentation as a mechanism for efficient recruitment of tumor-specific CTL to the brain. J Immunol. 2003;171:2187–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ackerman AL, Cresswell P. Cellular mechanisms governing cross-presentation of exogenous antigens. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:678–84. doi: 10.1038/ni1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heath WR, Belz GT, Behrens GM, et al. Cross-presentation, dendritic cell subsets, and the generation of immunity to cellular antigens. Immunol Rev. 2004;199:9–26. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiang J, Huang H, Liu Y. A new dynamic model of CD8+ effector cell responses via CD4+ T helper-antigen-presenting cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:7497–505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neijssen J, Herberts C, Drijfhout JW, Reits E, Janssen L, Neefjes J. Cross-presentation by intercellular peptide transfer through gap junctions. Nature. 2005;434:83–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hon H, Oran A, Brocker T, Jacob J. B lymphocytes participate in cross-presentation of antigen following gene gun vaccination. J Immunol. 2005;174:5233–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brandes M, Willimann K, Moser B. Professional antigen-presentation function by human γδ T cells. Science. 2005;309:264–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1110267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nguyen LT, Ramanathan M, Munschauer F, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of in vitro proinflammatory cytokines secretion in peripheral blood from multiple sclerosis patients. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:179–85. doi: 10.1023/a:1020555711228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen LT, Ramanathan M, Weinstock-Guttman B, Baier M, Brownscheidle C, Jacobs LD. Sex differences in in vitro pro-inflammatory cytokine production from peripheral blood of multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol Sci. 2003;15:93–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hemmer B, Vergelli M, Calabresi P, Huang T, McFarland HF, Martin R. Cytokine phenotype of human autoreactive T clones specific for the immunodominant myelin basic protein peptide (83–99) J Neurosci Res. 1996;45:852–62. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960915)45:6<852::AID-JNR22>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bielekova B, Sung MH, Kadom N, Simon R, McFarland H, Martin R. Expansion and functional relevance of high-avidity myelin-specific CD4+ T cells in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2004;172:3893–904. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sepulcre J, Sanchez-Ibarrola A, Moreno C, de Castro P. Association between peripheral IFN-γ producing CD8+ T-cells and disability score in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Cytokine. 2005;32:111–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fernández O, Arbizu T, Izquierdo G, Martínez-Yélamos A, Gata JM, Luque G. Clinical benefits of interferon beta-1a in relapsing-remitting MS. a phase IV study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;107:7–11. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rieckmann P, Toyka KV Multiple Sclerosis Therapy Consensus Group. Escalating immunotherapy of multiple sclerosis – new aspects and practical application. J Neurol. 2004;251:1329–39. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0537-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kilinc M, Saatci-Cekirge I, Karabudak R. Serial analyses of soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1 level in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients during IFN-β1b treatment. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2003;23:127–33. doi: 10.1089/107999003321532457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Espejo C, Brieva L, Ruggiero G, Río J, Montalban X, Martínez-Cáceres EM. IFN-β treatment modulates the CD28/CTLA-4 mediated pathway for IL-2 production in patients with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004;10:630–5. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1094oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pellegrini P, Totaro R, Contasta I, Berhella AM, Russo T, Carolei A, Adorno D. IFN-β1a treatment and reestablishment of Th1 regulation in MS patients: dose effects. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27:258–69. doi: 10.1097/01.wnf.0000148387.79476.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mitsdoerffer M, Schreiner B, Kieseier BC, Neuhaus O, Dichgans J, Hartung HP, Weller M, Wiendl H. Monocyte-derived HLA-G acts as a strong inhibitor of autologous CD4 T cell activation and is unregulated by interferon-βin vitro and in vivo: rationale for the therapy of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;159:155–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Totaro R, Passacantando A, Russo T, Parzanese I, Racsente M, Marini C, Tonietti G, Carolei A. Effect of interferon beta, cyclophosphamide and azathioprine on cytokine profile in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2005;18:377–83. doi: 10.1177/039463200501800219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gelati M, Corsini E, Dufour A, Massa G, La Mantia L, Milanese C, Nespolo A, Salmaggi A. Immunological effects of in vivo interferon-β1b treatment in ten patients with multiple sclerosis: a 1-year follow-up. J Neurol. 1999;1246:569–73. doi: 10.1007/s004150050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kraus J, Ling AK, Hamm S, Voigt K, Oschmann P, Engelhardt B. Interferon-β stabilizes barrier characteristics of brain endothelial cells in vitro. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:192–205. doi: 10.1002/ana.20161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schreiner B, Mitsdoerffer M, Kieseier BC, Chen L, Hartung HP, Weller M, Wiendl H. Interferon-β enhances monocyte and dendritic cell expression of B7-H1 (PD-L1), a strong inhibitor of autologous T-cell activation: relevance for the immune modulatory effect in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;155:172–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oh U, Yamano Y, Mora CA, et al. Interferon-β1a therapy in human T-lymphotropic virus type I-associated neurologic disease. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:526–34. doi: 10.1002/ana.20429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gniadek P, Aktas O, Wandinger KP, et al. Systemic IFN-β treatment induces apoptosis of peripheral immune cells in MS patients. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;137:187–96. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Viglietta V, Baecher-Allan C, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Loss of functional suppression by CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2004;199:971–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pede PD, Visintini D, Telera A, Cucurachi L, Campanini C, Immovilli P, Vescovini R, Sansoni P. Immunomodulatory effects of IFN-β1a treatment alone or associated with pentoxifylline in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:485–9. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petereit HF, Bamborschke S, Esse AD, Heiss WD. Interferon gamma producing blood lymphocytes are decreased by interferon beta therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 1997;3:180–3. doi: 10.1177/135245859700300302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Furlan R, Bergami A, Lang R, et al. Interferon-β treatment in multiple sclerosis patients decreases the number of circulating T cells producing interferon-γ and interleukin-4. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;111:86–92. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00377-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Franciotta D, Zardini E, Bergamaschi R, Andreoni L, Cosi V. Interferon γ and interleukin 4 producing T cells in peripheral blood of multiple sclerosis patients undergoing immunomodulatory treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:123–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]