Abstract

Dendritic cell-specific intercellular-adhesion-molecule-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN) is a potential target receptor for vaccination purposes. In the present study, we employed Lewis X (Lex) oligosaccharides, which mimic natural ligands, to target ovalbumin (OVA) to human dendritic cells (DCs) via DC-SIGN, to investigate the effect of this DC-SIGN-targeting strategy on the OVA-specific immune response. We demonstrated that Lex oligosaccharides could enhance the OVA-specific immune response as determined by enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT), intracellular interferon-γ staining and 51Cr-release assay. An almost 300-fold lower dose of Lex-OVA induced balanced interferon-γ-secreting cells compared to OVA alone. Furthermore, secretion of interleukin-10, a reported mediator of immune suppression related to DC-SIGN, was not increased by Lex-OVA, either alone or together with sCD40L-stimulated groups. A blocking antibody against DC-SIGN (12507) reduced the numbers of interferon-γ-secreting cells during Lex-OVA stimulation, yet it did not prevent Lex oligosaccharides from promoting the secretion of interleukin-10 that was induced by ultra-pure lipopolysaccharide. These results suggested that the strategy of DC-SIGN targeting mediated by Lex oligosaccharides could promote a T-cell response. This DC-targeting may imply a novel vaccination strategy.

Keywords: dendritic cells, DC-SIGN, Lewis X, T cells, vaccination

Introduction

Targeting vaccine to dendritic cells (DCs) is an important and convenient strategy to enhance vaccine immunogenicity. The selection of an appropriate receptor is a principal factor for the successful vaccine targeting of DCs.1,2

Dendritic cell-specific intercellular-adhesion-molecule-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN), a C-type lectin-like receptor, is mostly expressed on immature DCs3,4 and acts as an antigen receptor.5,6 So far, studies indicate that DC-SIGN could efficiently capture a variety of pathogens, such as human immunodeficiency virus and cytomegalovirus virions at a low concentration in the mucosal tissues.3,7,8 DCs can then present these antigens in major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted4 or class I-restricted5 fashions. However, following interactions between DC-SIGN and natural ligands, some immunomodulatory signals will be delivered to promote secretion of interleukin-10 (IL-10), inhibit maturation of DCs9 and shift toward a T helper type 2 (Th2) immune response.10 Although several features, including restricted expression on DCs and acting as an antigen receptor, make DC-SIGN an appropriate receptor for vaccination purposes,11 a proper strategy utilizing DC-SIGN still needed to be developed.9

Lewis X (Lex) oligosaccharide, a natural ligand of DC-SIGN, has higher affinity and specificity compared to the other oligosaccharide structures.12–14 Lex oligosaccharide is also an important component on the surface glycans of soluble eggs antigen from Schistosoma mansoni, and its repetitive array has been reported to contribute to the induction of the production of Th2-associated antibodies and cytokines in BALB/c mice.15–17 Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) containing Lex sugar from Helicobacter pylori is found to be able to inhibit Th1 responses in vitro via DC-SIGN.10 However, interactions between Mac-I on the neutrophils and DC-SIGN on the DCs mediated by Lex sugar does not result in Th2-type polarization of effector T cells.18 It is suggested that the Lex oligosaccharides contained in a different expression system possibly produce different effects on DCs, and that Th2 biasing is not the only result of Lex sugar treatment.

In the present study, we used a biotin–streptavidin (SA) system to conjugate Lex oligosaccharides to ovalbumin (OVA) antigen, and then investigated the effect of this targeting strategy on OVA-specific T-cell responses in vitro. Our results indicated that the Lex-OVA antigen could enhance antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses by almost 300-fold compared with OVA alone. Moreover, secretion of IL-10 was not increased in the supernatant of effector DCs that were stimulated were with Lex-OVA alone or in combination with CD40 ligand (CD40L) instead of ultra-pure LPS.

Materials and methods

Preparation of Lex-OVA

According to the manufacturer's directions, SA (MERCK-Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) was pretreated with 2-iminothiolane/HCl (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for 1 hr at room temperature, then allowed to react with the maleimide-activated OVA (Pierce) for 2 hr at room temperature to form the SA-OVA conjugates. The SA-OVA conjugates were purified by affinity chromatography with Sepharose 4B (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) conjugated with anti-OVA polyclonal antibody and ultrafiltration (50 000 MW, Millipore, Bedford, MA). A Bradford micro-assay was used to quantify the SA-OVA conjugates.

The conjugates were confirmed by Western blot. In brief, conjugates were separated in 10–15% sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) gel under non-dithiothreitol conditions and stained with Coomassie blue. The bands were transferred electrophoretically to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and incubated with anti-OVA (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA) and anti-SA (Vector, Burlingame, CA) antibodies. The results were visualized using chemiluminescence (Pierce).

The OVA protein was coated onto enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates to generate a standard curve for the quantification of OVA contained in the SA-OVA conjugates; mouse-derived immunoglobulin M (IgM)-biotin (1 μg/well, eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or Lex-polyacrylamide (PAA)-biotin (1 μg/well, Glycotech, Maryland, CA) was coated onto ELISA plates for investigation of specific binding and the saturated reaction ratio between SA in the conjugates and biotin. The conjugates were added to ELISA plates coated with IgM-biotin or Lex-PAA-biotin, then incubated at 37° for 30 min. Binding was determined by mouse-derived anti-OVA polyclonal antibody and a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody.

According to the reaction ratio from the above experiments, the purified SA-OVA (4 μg) was mixed with Lex-PAA-biotin (1 μg) and incubated for 30–60 min at room temperature. The last production, Lex-OVA, was lyophilized for extended storage. Lex-OVA contained <1 ng/20 μg endotoxin.

Cells

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained from the whole blood from normal donors over Lymphoprep (Axis Shield, Oslo, Norway). Monocytes were purified from PBMC by adherence for 90 min in complete medium. Non-adherent cells (autologous peripheral blood lymphocytes) were removed gently, washed and frozen as a resource of T cells. The remaining adherent cells (> 90% monocytes by flow cytometry) were induced using 800 U/ml recombinant human granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF, R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and 1000 U/ml IL-4 (R & D Systems) for 5 days. The immature DCs were obtained and used for internalization assays and antigen-specific T-cell activation experiments.

K562 cell lines transfected with plasmid transiently expressing DC-SIGN-EGFP (K562-ED) were used for the internalization assay of Lex-OVA.

Internalization assays of ligands

Immature DCs and K562-ED were incubated with ligand or antigen for 60 min at 4°, washed twice and incubated for different times at 37°. Then the cells were harvested and used in a confocal microscopy assay. In brief, the cells were adhered to poly l-lysine-coated glass slides, fixed with 4% polyformaldehyde, stained and analysed using a TCS-NT confocal microscope. In blocking experiments, 20–40 μg/ml anti-DC-SIGN antibody (120507, R & D Systems) was incubated before ligand or antigen treatment for 30 min.

Antigen-specific T-cell sensitization in vitro

Immature DCs were incubated with various antigens (OVA, SA-OVA and Lex-OVA) for 1 hr at 37° and matured using soluble CD40L (sCD40L, 20 ng/ml, PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) for a further 24 hr. T cells were isolated from autologous peripheral blood lymphocytes by B-cell negative depletion (R & D Systems). Irradiated (3000 rads) or unirradiated effector DCs were incubated with T cells in the presence of IL-7 (10 ng/ml; day 0), followed by addition of IL-2 (20 U/ml; day 5 for first cycle, day 2 for the other cycles). The ratio of T-cells : DCs was maintained at 10 during the stimulation. IL-2 was added every 3–4 days. The effector T cells were harvested and assayed. The cytokines used in the above experiments were obtained from PeproTech and the OVA (A5378) was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). In block experiments, anti-DC-SIGN block antibody (40 μg/ml) was incubated with immature DCs 30 min before antigen treatment.

Assays for OVA-specific immune responses

Enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT) kits (U-CyTech, Utrecht, the Netherlands) were used to measure antigen-specific interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-producing cell activation according to the manufacturer's protocols. Antigen-specific effector cells were obtained from a 14-day in vitro sensitization. Then, the effector T cells were suspended in AIMV serum-free medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and used to detect IFN-γ release, with DC loaded with OVA (20 μg/ml) or without as a specific target. IFN-γ spots were enumerated by a computer-assisted immunospot image analyser.

IFN-γ-producing effector cells were also assayed by intracellular cytokine staining. Briefly, the autologous T cells were cocultured with DCs that were loaded with graded doses of various antigens for 14 days. Then the cells were restimulated with autologous DCs, loaded with OVA (20 μg/ml) and matured with sCD40L (20 ng/ml), for 10 hr in the presence of brefeldin A (5 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for the last 9 hr. The staining was performed as described elsewhere.19

Cytotoxic activity was measured in a standard 4-hr 51Cr-release assay using the OVA-expressing and human leucocyte antigen (HLA) A2.1+ breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 as target cells to be killed, as depicted previously.20 Effector T cells were obtained from four in vitro sensitization cycles (one week/cycle). The per cent specific lysis was calculated as follows: % specific lysis = (experimental lysis − minimum lysis)/(maximum lysis − minimum lysis) × 100. Minimum lysis was obtained by incubating the target cells with the culture medium alone. Maximum lysis was obtained by exposing the target cells to 2% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline.

ELISA assays of cytokines

Supernatants of DC cultures stimulated by Lex-OVA or by Lex oligosaccharide monomer together with sCD40L or ultra-pure LPS (from Escherichia coli 0111:B4 strain, InvivoGen, Carlsbad, CA) or not, were harvested after 24 hr, and kept frozen at −70° until use. IL-6, IL-12 (p70), IFN-γ and IL-10 in the supernatant were assayed by ELISA kits from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA). The minimum detectable dose of IL-10 was 15 pg/ml. The minimum detectable dose of IFN-γ was 7 pg/ml.

The Lex oligosaccharide monomer was synthesized as described briefly: the Lex pentasaccharide was synthesized starting from a protected trisaccharide which we had prepared previously; the structure of the Lex pentasaccharide was fully characterized by [1H, 13C]-nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectroscopy.

Construct of OVA-expressing plasmid

The OVA gene was subcloned into pCI-neo vector (Promega, Madison, WI) using the EcoRI and SalI sites. The recombinant plasmid was transfected into MCF-7 with lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in combination with CombiMag (OZ Biosciences, Marseille, France). The expression of OVA was confirmed by immunofluorescence.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons were made using Student's t-test and analysis of variance (anova). The differences were significant if P ≤ 0·05.

Results

Preparation of OVA conjugated to Lex oligosaccharides

We devised an approach to obtain Lex-OVA antigen. First, OVA were chemically coupled to SA; then, SA-OVA conjugates were linked to Lex-PAA-biotin via SA-biotin binding.

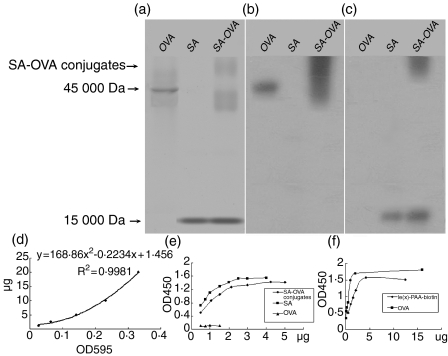

The maleimide-activated whole OVA protein was chemically cross-linked to SA, which had been pretreated with 2-iminothiolane/HCl to produce terminal sulphydryl groups to make coupling easy. The SA-OVA conjugates were verified in SDS–PAGE and Western blot (Fig. 1a–c). According to band density in reference to the SA and OVA, we estimated that the molecular ratio of SA to OVA in the conjugates was 2 : 1. Then, free SA was removed by purifying the conjugates on affinity chromatography for OVA, and unbound OVA smaller than the pore-size rating of 50 000 MW was also removed by ultrafiltration. SA-OVA conjugates were obtained and quantified by Bradford micro-protein assay. The standard curve of OVA protein used for quantification of the conjugates is given in Fig. 1(d).

Figure 1.

Preparation of Lex-OVA. (a) OVA, SA and SA-OVA run on SDS–PAGE. The electrophoretic behaviour of the protein (SA-OVA) treated with a chemical cross-linking reagent had changed and displayed a smear band in contrast to the native OVA. Residual OVA (runs a little faster than the native OVA) and SA, in the lane marked SA-OVA, were observed. (b) Immunoblotting with anti-OVA antibody to detect OVA in the SA-OVA conjugates. (c) Immunoblotting with anti-SA antibody to detect SA in the SA-OVA conjugates. (d) The standard curve used for quantification of SA-OVA conjugates in the Bradford micro-assay. (e) SA-OVA conjugates, SA (positive control) and OVA (negative control) were used to detect the specific biotin-binding capacity. (f) Capacity of SA-OVA conjugates to bind Lex-PAA-biotin.

We then investigated whether SA binding function was affected after coupling to OVA. SA in the conjugates was verified as being able to bind to biotin specifically using ELISA in a plate that was coated with mouse-derived IgM labelled with biotin (Fig. 1e). The OVA alone, as a negative control in this experiment, did not show any capacity to bind to biotin. Furthermore, SA-OVA conjugates were also able to bind to Lex-PAA-biotin, a polyacrylamide polymer of approximately 30 000 MW containing 5%mol biotin and 20%mol Lex oligosaccharides, coated on the ELISA plate at 1 μg/well, and we estimated that conjugates of approximately 4 μg (about 1·5 μg OVA, according to the OVA standard curve) had complete binding capacity to Lex-PAA-biotin of 1 μg (Fig. 1f). Therefore, based on the characteristic of SA binding biotin with high affinity, we yielded a targeting to DC-SIGN antigen, Lex-OVA, through 4 μg : 1 μg reaction ratio.

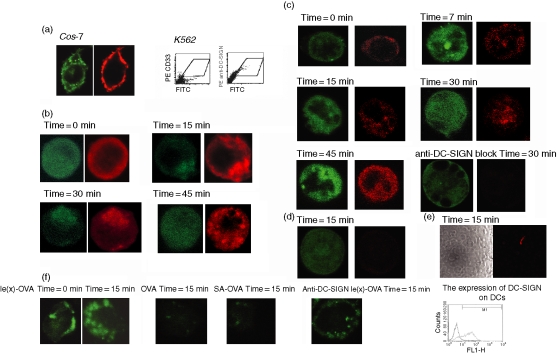

Specific targeting of Lex-OVA to DC-SIGN

Previous studies have demonstrated that Lex oligosaccharide or Lex-PAA-biotin could target DC-SIGN.12,13 We further investigated whether Lex-OVA could target DC-SIGN. To this end, we constructed a transfectant K562-EGFP-DC-SIGN (K562-ED) that expressed the DC-SIGN-EGFP fusion protein. The fusion protein was localized on the cell membrane and was recognized by anti-DC-SIGN antibody (Fig. 2a). As mentioned previously,12 using Lex-PAA-biotin, which is a verified specific ligand of DC-SIGN, we confirmed that the fusion protein was able to mediate specific ligand internalization (Fig. 2b). Then we investigated whether Lex-OVA antigen could be taken up by K562-ED. The K562-ED took up the Lex-OVA antigen rapidly in 15 min; while the anti-DC-SIGN antibody mostly prevented Lex-OVA uptake. In contrast, K562-expressing EGFP or K562 cell lines are incapable of Lex-OVA uptake in 15 min (Fig. 2c–e). This result showed that Lex-OVA could target to DC-SIGN efficiently.

Figure 2.

Lex-OVA was specifically targeted to DC-SIGN. (a) Left panel: expression of DC-SIGN-EGFP (green) fusion protein was assayed on Cos-7 cell lines by confocal microscopy. The fusion protein was stained with anti-DC-SIGN(Cy3). Right panel: expression of DC-SIGN-EGFP (green) fusion protein on K562 cell lines was detected by double colour in a fluorescence-activated cell sorter assay. The phycoerythrin (PE) signal was from anti-DC-SIGN or anti-CD33 (a molecule expressed on the K562 cell lines used to gate). (b) Lex-PAA-biotin uptake by K562-ED. The cell was stained with streptvidin-Cy3 for localization of Lex. (c) Lex-OVA uptake by K562-ED. The cell was stained with rabbit-derived anti-OVA and goat anti-rabbit IgG(Cy3) for localization of OVA. (d) Lex-OVA was not taken up by K562 cell lines expressing EGFP in 15 min. (e) Lex-OVA was not taken up by K562 cell lines in 15 min. (f) Lex-OVA uptake by the primary monocyte-derived DCs. The expression of DC-SIGN on the DCs is also shown.

Primary monocyte-derived DCs were also confirmed to have the capacity for Lex-OVA uptake in 15 min efficiently, but not for OVA or SA-OVA antigen. Internalization of Lex-OVA was abrogated significantly when binding of DC-SIGN was blocked (Fig. 2f).

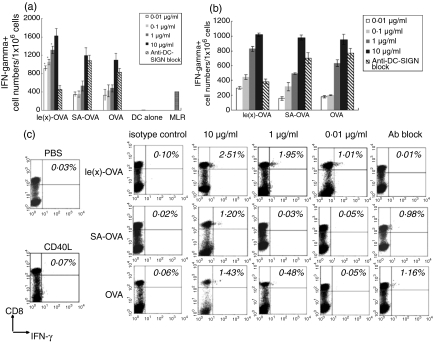

Antigen-specific effector T-cell activation

After obtained the Lex-OVA antigen, we further investigated the capacity of this novel antigen to induce OVA-specific T-cell activation by assaying the numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells induced by Lex-OVA or native antigens using an ELISPOT assay and intracellular cytokine staining. We used autologous DCs, pulsed with graded doses of various antigens and matured with sCD40L, as a stimulator to activate effector T cells. After 14 days of in vitro sensitization, IFN-γ-producing cells were detected in response to the specific target cells, which were autologous DCs loaded with OVA (20 μg/ml) and matured with sCD40L. As shown in Fig. 3(a) the T cells spontaneously produced some spots in the presence of autologous mature DCs unloaded by antigen (mixed lymphocyte reaction 410 ± 76·34 spots/106 T cells), but spots were rarely seen in the presence of autologous mature DCs alone. Compared to ELISPOTs from mixed lymphocyte reactions, at concentrations ≤1 μg/ml (especially 0·01 μg/ml), Lex-OVA invoked significant numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells (P < 0·01 for 0·01–1 μg/ml group); SA-OVA or OVA, however, did not generate significant OVA-specific IFN-γ-producing cells. The blockade of anti-DC-SIGN antibody reduced IFN-γ-producing cell numbers induced by Lex-OVA to approximately the level of the mixed lymphocyte reaction. Moreover, in the absence of the specific target cells, the numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells in effector T cells were not significantly different between the Lex-OVA and control groups (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Antigen-specific IFN-γ-producing cells increased after DC-SIGN targeting via Lex oligosaccharides. (a) Effector T cells were generated from in vitro sensitization for 14 days and were used to detect the numbers of IFN-γ-secreting cells. DCs loaded with OVA and matured with sCD40L were added to wells to be a specific target; 40 μg/ml anti-DC-SIGN was used for blockade in the 10 μg/ml Lex-OVA stimulation group. Data are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate with similar results. (b) Effector T cells were stimulated and assayed as above, except without specific target cells added into the ELISPOT assay wells. Controls (not shown): lane 1, positive control (autologous PBMC were stimulated with PMA (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 μg/ml)): 140 ± 47·15 spots/105 PBMC; lane 2, negative control (autologous PBMC): 0–2 spots/105 PBMC; lane 3 negative control (autologous PBMC with OVA 20 μg): 4–6 spots/105 PBMC. Data are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate with similar results. (c) The antigen-specific IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells were observed. Effector T cells were stimulated as above; 40 μg/ml anti-DC-SIGN was used for blockade in the 10 μg/ml Lex-OVA stimulation group. Data are representative of four independent experiments performed with similar results. Statistical significance of the differences (P < 0·01) is between 0·01 and 1 μg/ml of Lex-OVA and other controls (SA-OVA and OVA alone) stimulation groups. Asterisks indicated statistical significance (P < 0·01, anova).

The data from intracellular IFN-γ staining also showed similar results. IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells were induced by doses of Lex-OVA between 0·01 and 10 μg/ml; however, ≤1 μg/ml SA-OVA or OVA could not activate effector T cells (P < 0·01 for 0·01–1 μg/ml group) (Fig. 3c). It was indicated that Lex-OVA promoted the activation of OVA-specific IFN-γ-producing cells, and 0·01 μg/ml of Lex-OVA induced balanced numbers of OVA-specific IFN-γ-producing cells compared to >1 μg/ml of OVA alone. Because approximately 0·0033 μg of OVA alone could be obtained from 0·01 μg of Lex-OVA, the DC-SIGN receptor-targeted antigen was at least 300-fold more effective for activation of effector T cells, including CD8+ T cells, than the non-targeted antigen.

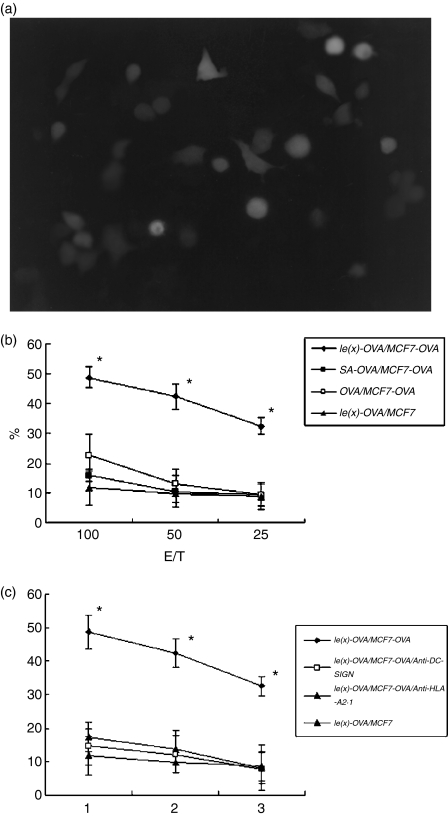

The HLA-A2.1+ MCF-7 cell line expressing OVA protein as a specific target (Fig. 4a) triggered the cytotoxic T-cell response (Fig. 4b,c). Cytolysis induced by Lex-OVA (10 μg/ml) was two-fold higher than that induced by OVA alone (P < 0·01). However, no significant cytotoxic T-cell response was shown by MCF-7 that did not express OVA protein.

Figure 4.

Lex-OVA enhanced antigen-specific cytotoxic response. (a) The expression of OVA was displayed after transfection with OVA gene plasmid for 24 hr in the MCF-7. (b and c) Specific lysis was measured with 51Cr-release assay. Effector T cells were stimulated with autologous DCs (irradiated) loaded with various antigens at doses of 10 μg/ml for 4 weeks. Then the effector T cells were used to assay antigen-specific lysis. Data are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate with similar results. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0·01, anova).

Cytokine secretion and DC maturation induced by Lex oligosaccharide clusters

To investigate whether interaction between Lex oligosaccharides and DC-SIGN results in potential immunoregulatory signals, we assayed the secretion of cytokines in the cell supernatant of DCs treated with OVA or Lex-OVA. There was no significant distinction between IFN-γ levels in supernatants of different groups (Fig. 5a); however, the secretion of IL-10, a mediator of immune suppression in ManLAM-treated DCs, as reported previously,9 increased significantly in the group given Lex-OVA together with ultra-pure LPS (Fig. 5a,b) (P < 0·01 for 1–100 ng/ml LPS group). In the supernatants of DCs treated with Lex-OVA alone and of DCs treated with Lex-OVA in combination with sCD40L, IL-10 was not increased (Fig. 5a,b). We further investigated the secretion of IL-6 in the supernatant of DCs that were treated with Lex-OVA together with doses of ultra-pure LPS from 1 ng/ml to 100 ng/ml, and little increase of IL-6 level was observed (Fig. 5c). The level of IL-12p70 was hardly detectable. Interestingly, the anti-DC-SIGN blocking antibody (507) did not block the secretion of IL-10. Instead, as for Lex sugar, it promoted the secretion of IL-10 together with ultra-pure LPS (P < 0·01) (Fig. 5b,c).

Figure 5.

Lex-OVA together with ultra-pure LPS instead of sCD40L promoted the secretion of IL-10. (a) Lex-OVA (10 μg/ml) together with LPS promoted the secretion of IL-10 on DCs. The supernatants of DCs treated differently were used to assay levels of IL-10 and IFN-γ. Data are representative of three experiments. (b) Secretion of IL-10 was examined on the supernatants of DCs treated by Lex-OVA together with graded doses of ultra-pure LPS. The block antibody (40 μg/ml) could not prevent but enhanced the secretion of IL-10. Data are representative of three independent experiments in triplicate. (c) As above, secretion of IL-6 was assayed. Data are representative of three independent experiments in triplicate. (d) Lex oligosaccharides monomers (10 μg/ml) together with ultra-pure LPS (10 ng/ml) could not increase the level of IL-10. However, the blocking antibody (20 μg/ml) still enhanced the secretion of IL-10. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (e) Lex-OVA engagement to DC-SIGN did not decrease the expression of CD86 by flow cytometry. Data are representative of two experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0·01, Student's t-test).

Different forms of the Lex oligosaccharides assembly had a different effect on the secretion of IL-10. Unlike Lex oligosaccharides, clusters existed in Lex-OVA; 10 μg/ml Lex oligosaccharide monomer, even when combined with ultra-pure LPS, was not observed to promote secretion of IL-10 (Fig. 5d).

We also examined if the interaction between Lex oligosaccharide clusters and DC-SIGN would result in the suppression of the maturation of DCs. It was shown that with the increase of ultra-pure LPS from 1 to100 ng/ml, pretreatment by Lex-OVA could not alter the growth rate of the mean fluorescence intensity of CD86 induced by LPS (Fig. 5e). It was suggested that DCs treated with Lex oligosaccharide clusters did not display significant maturation suppression.

Discussion

DC-SIGN has been characterized by its efficient capture of pathogens and restricted expression on DCs, which makes it a preferable candidate for a vaccine-targeting receptor.11 Many natural ligands of DC-SIGN expressed on pathogens have been identified. Some natural ligands might subvert DC functions to help the pathogens escape immune attack, such as ManLAM from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which implies that DC-SIGN in some circumstances may be a disadvantage in the induction of antigen-specific immunity. Thus, selection of proper targeting strategies is critical. A recent study by Tacken et al. has verified that targeting of DC-SIGN mediated by an anti-DC-SIGN antibody displays more efficient antigen presentation than a native antigen.21 In the present study, we demonstrated that the targeting of DC-SIGN mediated by Lex oligosaccharides also enhanced T-cell immune response.

IFN-γ is a representative effector cytokine of CD8+ T cells, and in the presence of specific targets an assay of CD8high IFN-γ-producing cells would indicate the activation of antigen-specific effector CD8+ T cells. Antigen-specific lysis is another important function of effector CD8+ T cells. The results from ELISPOT, intracellular IFN-γ staining and 51Cr-release assays demonstrated that Lex oligosaccharides targeting of DC-SIGN promoted antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell activation, which was at least 300-fold more efficient than pulsing DCs with non-targeted antigen. Blockade of binding to DC-SIGN decreased the numbers of antigen-specific IFN-γ-producing cells significantly, which indicated that internalization mediated by DC-SIGN played an important role in antigen-specific T-cell activation. Internalization mediated by DC-SIGN might result in antigen entry into a specific and efficient presentation pathway, as mentioned in the DEC-205 targeting study,22,23 which promotes the production of antigen peptide–major histocompatibility complex complexes and the subsequent activation of effector T cells. The sCD40L was an appropriate immune adjuvant to promote CD8+ T-cell responses, not to increase the level of IL-10 and inhibit the maturation of DCs, after Lex oligosaccharides targeting to DC-SIGN.

IL-10 is one of the agents known to be critical for the induction of immune tolerance,24–27 and it has been reported to inhibit the maturation of DCs and the maturation-driven shift from inflammatory chemokine receptors to the lymphoid homing receptor CCR7, which stops DCs from migrating to the lymph nodes for recruitment of T cells and contributes to the generation of antigen-specific T-cell anergy.25–27 IL-10 is thought to be an anti-inflammatory cytokine for the limitation of excessive inflammatory reactions in response to LPS and an inhibitor of T-cell-specific activation.28,29 Thus, IL-10 would affect the result of antigen-specific T-cell immune responses, either activation or suppression.

Our results indicated no increase of IL-10 in the DC groups given Lex oligosaccharides alone or together with sCD40L. However, together with ultra-pure LPS, Lex oligosaccharide clusters significantly promoted the secretion of IL-10, while that of IL-6 was little changed. It is known that no C-type lectin other than DC-SIGN expressed on human DCs has been identified as recognizing Lex oligosaccharides,10 and that ultra-pure LPS is recognized by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on DCs,30 which strongly suggests that collaboration occurs between DC-SIGN and TLR4. One of the mouse homologues of human DC-SIGN, mSIGNR1,31,32 is also found to have a collaborative effect with TLR4 to enhance signal transduction by recognition of LPS.33 Mice with mSIGNR1 knock-out are significantly more susceptible to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection and fail to clear S. pneumoniae from their circulations.34 Both our data and those of others suggested that the collaboration between TLR4 and DC-SIGN was involved in the control of IL-10 secretion, which implies a regulation mechanism of innate and adaptive immune responses to antigen targeting of DC-SIGN. Future study is needed to investigate the effect of LPS on antigen-specific immunity after Lex oligosaccharide targeting of DC-SIGN. However, this was beyond the scope of this paper.

Not only different immune adjuvants but also different assemblies of Lex oligosaccharides could result in a different level of IL-10. The Lex oligosaccharide monomer together with LPS did not promote the secretion of IL-10, although the dose of Lex monomer was 10 times more than the 10 μg/ml Lex-OVA used (data not shown) that caused a notable increase in IL-10. It is possible that the interaction energy between different assembly forms of Lex oligosaccharides and DC-SIGN results in these distinct effects.35 The interaction between the Lex oligosaccharide clusters that exist in Lex-OVA and DC-SIGN seemed to promote the secretion of IL-10 more easily. More direct results are needed to verify the hypothesis.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated: (1) that Lex oligosaccharides targeting of DC-SIGN would induce an at least 300-fold more efficient T-cell immune response; (2) that targeting mediated by Lex oligosaccharides may be a novel appropriate strategy for the targeting of DC-SIGN for vaccination immunity; (3) that an appropriate immune adjuvant, which may decide the form of immune response, needs to be tested as one of the components of future vaccines involved in DC-SIGN targeting.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiaolan Fu and Xin Li for the flow cytometry analysis; Wei Sui for confocal microscopy assay; and Dr T.B. Geijtenbeek for the kind gift of plasmid containing cDNA of DC-SIGN. This study was supported by the State Key Basic Research Program of China (No. 2001CB510001), the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30490240), the Outstanding Young Scientist Foundation of China (No. 30325020), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30600555) and the Natural Science Foundation Project of CQ CSTC.

Abbreviations

- DC-SIGN

dendritic cell-specific intercellular-adhesion-molecule-grabbing non-integrin

- ELISPOT

enzyme-linked immunospot assay

- GM-CSF

granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HLA

human leucocyte antigen

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- K562-ED

K562 cell lines expressing DC-SIGN-EGFP protein

- Lex

Lewis X

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

References

- 1.Bonifaz L, Bonnyay D, Mahnke K, Rivera M, Nussenzweig MC, Steinman RM. Efficient targeting of protein antigen to the dendritic cell receptor DEC-205 in the steady state leads to antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex class I products and peripheral CD8+ T cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1627–38. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramakrishna V, Treml JF, Vitale L, Connolly JE, et al. Mannose receptor targeting of tumor antigen pmel17 to human dendritic cells directs anti-melanoma T cell responses via multiple HLA molecules. J Immunol. 2004;172:2845–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geijtenbeek TB, Kwon DS, Torensma R, et al. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;100:587–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soilleux EJ, Morris LS, Leslie G, et al. Constitutive and induced expression of DC-SIGN on dendritic cell and macrophage subpopulations in situ and in vitro. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:445–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engering A, Geijtenbeek TB, van Vliet SJ, et al. The dendritic cell-specific adhesion receptor DC-SIGN internalizes antigen for presentation to T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:2118–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moris A, Nobile C, Buseyne F, Porrot F, Abastado JP, Schwartz O. DC-SIGN promotes exogenous MHC-I-restricted HIV-1 antigen presentation. Blood. 2004;103:2648–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halary F, Amara A, Lortat-Jacob H, et al. Human cytomegalovirus binding to DC-SIGN is required for dendritic cell infection and target cell trans-infection. Immunity. 2002;17:6536–64. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00447-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon DS, Gregorio G, Bitton N, Hendrickson WA, Littman DR. DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of HIV is required for trans-enhancement of T cell infection. Immunity. 2002;16:135–44. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geijtenbeek TB, van Vliet SJ, Koppel EA, Sanchez-Hernandez M, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Appelmelk B, van Kooyk Y. Mycobacteria target DC-SIGN to suppress dendritic cell function. J Exp Med. 2003;197:7–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergman MP, Engering A, Smits HH, et al. Helicobacter pylori modulates the T helper cell 1/T helper cell 2 balance through phase-variable interaction between lipopolysaccharide and DC-SIGN. J Exp Med. 2004;200:979–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figdor CG, de Vries IJ, Lesterhuis WJ, Melief CJ. Dendritic cell immunotherapy: mapping the way. Nat Med. 2004;10:475–80. doi: 10.1038/nm1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appelmelk BJDI, van Vliet SJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Geijtenbeek TB, van Kooyk Y. Cutting edge: carbohydrate profiling identifies new pathogens that interact with dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3-grabbing nonintegrin on dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:1635–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frison N, Taylor ME, Soilleux E, Bousser MT, Mayer R, Monsigny M, Drickamer K, Roche AC. Oligolysine-based oligosaccharide clusters. Selective recognition and endocytosis by the mannose receptor and dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3 (ICAM-3) -grabbing nonintegrin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23922–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van DI, van Vliet SJ, Nyame AK, Cummings RD, Bank CM, Appelmelk B, Geijtenbeek TB, van Kooyk Y. The dendritic cell-specific C-type lectin DC-SIGN is a receptor for Schistosoma mansoni egg antigens and recognizes the glycan antigen Lewis x. Glycobiology. 2003;13:471–8. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okano M, Satoskar AR, Nishizaki K, Harn DA., Jr Lacto-N-fucopentaose III found on Schistosoma mansoni egg antigens functions as adjuvant for proteins by inducing Th2-type response. J Immunol. 2001;167:442–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas PG, Harn DA., Jr Immune biasing by helminth glycans. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:13–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Velupillai P, Harn DA. Oligosaccharide-specific induction of interleukin 10 production by B220+ cells from schistosome-infected mice: a mechanism for regulation of CD4+ T-cell subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:18–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Gisbergen KP, Sanchez-Hernandez M, Geijtenbeek TB, van Kooyk Y. Neutrophils mediate immune modulation of dendritic cells through glycosylation–dependent interactions between Mac-1 and DC-SIGN. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1281–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jankovic D, Kullberg MC, Noben-Trauth N, Caspar P, Paul WE, Sher A. Single cell analysis reveals that IL-4 receptor/Stat6 signaling is not required for the in vivo or in vitro development of CD4+ lymphocytes with a Th2 cytokine profile. J Immunol. 2000;164:3047–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wizel B, Houghten RA, Parker KC, Coligan JE, Church P, Gordon DM, Ballou WR, Hoffman SL. Irradiated sporozoite vaccine induces HLA-B8-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses against two overlapping epitopes of the Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite surface protein 2. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1435–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tacken PJ, de Vries IJ, Gijzen K, et al. Effective induction of naive and recall T-cell responses by targeting antigen to human dendritic cells via a humanized anti-DC-SIGN antibody. Blood. 2005;106:1278–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahnke K, Guo M, Lee S, Sepulveda H, Swain SL, Nussenzweig M, Steinman RM. The dendritic cell receptor for endocytosis, DEC-205, can recycle and enhance antigen presentation via major histocompatibility complex class II-positive lysosomal compartments. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:673–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.3.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahnke K, Qian Y, Fondel S, Brueck J, Becker C, Enk AH. Targeting of antigens to activated dendritic cells in vivo cures metastatic melanoma in mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7007–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maurer M, Seidel-Guyenot W, Metz M, Knop J, Steinbrink K. Critical role of IL-10 in the induction of low zone tolerance to contact allergens. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:432–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI18106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller G, Muller A, Tuting T, Steinbrink K, Saloga J, Szalma C, Knop J, Enk AH. Interleukin-10-treated dendritic cells modulate immune responses of naive and sensitized T cells in vivo. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:836–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nolan KF, Strong V, Soler D, et al. IL-10-conditioned dendritic cells, decommissioned for recruitment of adaptive immunity, elicit innate inflammatory gene products in response to danger signals. J Immunol. 2004;172:2201–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinbrink K, Graulich E, Kubsch S, Knop J, Enk AH. CD4(+) and CD8(+) anergic T cells induced by interleukin-10-treated human dendritic cells display antigen-specific suppressor activity. Blood. 2002;99:2468–76. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grutz G. New insights into the molecular mechanism of interleukin-10-mediated immunosuppression. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:3–15. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0904484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roers A, Siewe L, Strittmatter E, et al. T cell-specific inactivation of the interleukin 10 gene in mice results in enhanced T cell responses but normal innate responses to lipopolysaccharide or skin irritation. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1289–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:675–80. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park CG, Takahara K, Umemoto E, et al. Five mouse homologues of the human dendritic cell C-type lectin, DC-SIGN. Int Immunol. 2001;13:1283–90. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.10.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geijtenbeek TB, Groot PC, Nolte MA, et al. Marginal zone macrophages express a murine homologue of DC-SIGN that captures blood-borne antigens in vivo. Blood. 2002;100:2908–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagaoka K, Takahara K, Tanaka K, et al. Association of SIGNR1 with TLR4-MD-2 enhances signal transduction by recognition of LPS in gram-negative bacteria. Int Immunol. 2005;17:827–36. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lanoue A, Clatworthy MR, Smith P, et al. SIGN-R1 contributes to protection against lethal pneumococcal infection in mice. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1383–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gourier C, Pincet F, Perez E, Zhang Y, Mallet JM, Sinay P. Specific and non specific interactions involving Le (X) determinant quantified by lipid vesicle micromanipulation. Glycoconj J. 2004;21:165–74. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000044847.15797.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]